Abstract

Adult neurogenesis, a developmental process of generating functionally integrated neurons from neural stem cells, occurs throughout life in the hippocampus of the mammalian brain and highlights the plastic nature of the mature central nervous system. Substantial evidence suggests that new neurons participate in cognitive and affective brain functions and aberrant adult neurogenesis contributes to various brain disorders. Focusing on adult hippocampal neurogenesis, we review recent findings that advance our understanding of the key properties and potential functions of adult neural stem cells. We further discuss the key evidence demonstrating the causal role of aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis and various brain disorders. Finally, we propose strategies aimed at simultaneously correcting stem cells and their niche for treating brain disorders.

Keywords: Endogenous, neural stem cells, adult hippocampus, neurogenesis, brain disorders

Endogenous NSCs in the adult brain

The adult mammalian brain is a dynamic structure, capable of remodeling in response to various physiological, pathological, and pharmacological stimuli. One dramatic example of brain plasticity (see Glossary) is the birth and subsequent integration of newborn neurons into the hippocampus of the adult mammalian brain, including humans [1–5] (see text box). Adult hippocampal neurogenesis has garnered significant interest because substantial evidence suggests that adult-born new neurons contribute to learning and memory, stress response, and mood regulation [6–8]. A general model has proposed that adult hippocampal neurogenesis is not merely a cell-replacement mechanism, but instead maintains a plastic hippocampal neural circuit via continuous addition of adult-born new neurons with unique properties and structural plasticity of mature neurons induced by new neuron integration. In addition, many studies have implicated dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in an increasing number of brain disorders, such as epilepsy, major depression, and neurodegenerative diseases [7, 9–11]. Continuous hippocampal neurogenesis in the mature brain reflects large-scale plasticity unique to this region, and could potentially serve as a target for modulation of a subset of cognitive and affective behaviors caused by various brain disorders. Here we review recent findings that advance our understanding of the key properties and potential functions of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. We further discuss the key evidence of how aberrant adult hippocampal neurogenesis contributes to several forms of brain disorders including epilepsy, mental disorders, and neurodevelopmental disorders. Finally, we propose strategies aimed at simultaneously correcting both NSCs and their niche for potential treatment of those brain disorders.

Recently, two prominent studies have elicited scientific debate about adult hippocampal neurogenesis in humans. A report by Sorrells et al. concluded that neurogenesis in the human DG drops to undetectable level during childhood [12]. In another study, Boldrini et al. came to the opposite conclusion and reported lifelong neurogenesis in humans [4]. To facilitate the discussions on this topic, a recent article led by Kempermann, Gage, and Frisén reviewed the key evidence from many laboratories on this topic, proposed future directions of how to further investigate human neurogenesis, and discussed how the current state of knowledge about adult hippocampal neurogenesis applies to the human situation [5]. They concluded that “currently there is no reason to abandon the idea that adult-generated neurons make important functional contributions to neural plasticity and cognition across the human lifespan”.

Key properties of adult neural stem cells

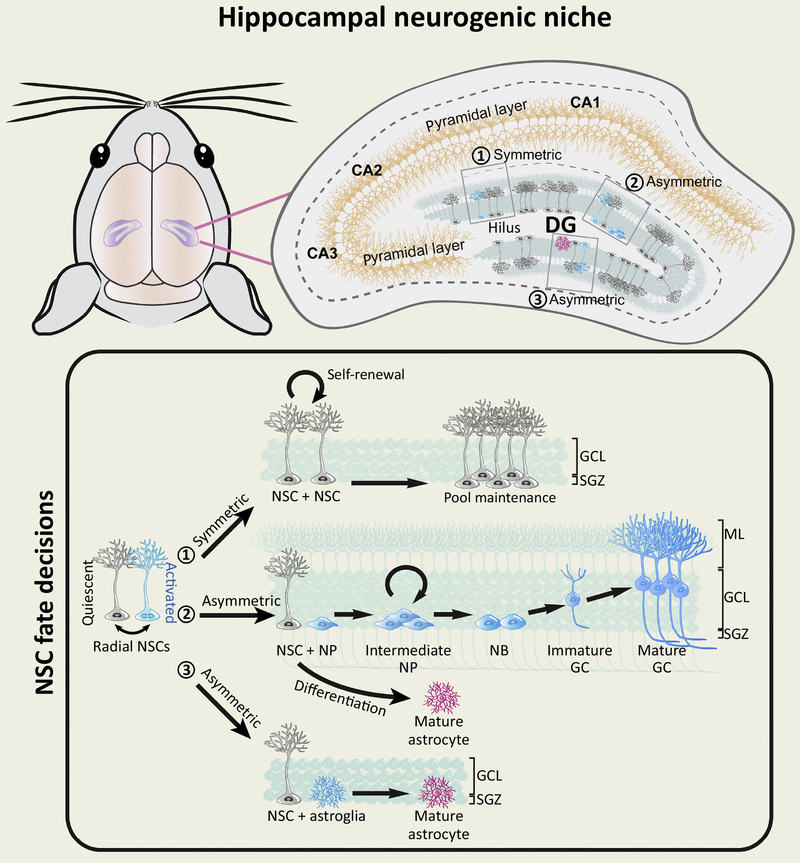

NSCs with radial morphology in the DG are thought to be the most primitive NSCs in the adult brain and are essential substrates for continuous neurogenesis throughout life. Recently, it has become clear that NSCs face multiple decision points during the initial stages of adult neurogenesis, including decisions for quiescence versus activation, fate specification, and long-term maintenance (Figure 1). Importantly, these decision points for NSCs are subject to activity-dependent regulation.

Figure 1: Key properties of adult hippocampal neural stem cells.

The key sources of adult hippocampal neurogenesis (blue) are the radial neural stem cells (rNSCs) (grey) located in the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus (DG). Their radial processes typically extend through the granule cell layer (GCL) and some of them reach the inner molecular layer (ML). Detailed hippocampal neurogenic niche is illustrated on the top panel. Most of the rNSCs are quiescent, but they can become activated in response to various niche stimuli. Once activated, they face multiple fate decisions: 21) Symmetric division of NSCs will allow them to self-renew and generate more NSCs to maintain the NSC pool. 2) Asymmetric division of NSCs will allow them to generate intermediate neural progenitors (NPs) that in turn give rise to neuroblasts (NBs), immature granule cells (GCs), and eventually mature GCs that integrate into the existing hippocampal circuit. The original NSCs will differentiate into astrocytes after several rounds of neurogenic divisions. 3) Asymmetric division of NSCs will also allow NSCs to give rise to astroglia (pink) that eventually become mature astrocytes.

Quiescence versus activation of NSCs:

In the SGZ of the adult DG, radial NSCs (rNSCs) are largely quiescent, but they can become activated in response to various external stimuli, such as exercise, antidepressants, and epilepsy [13]. Quiescence is thought to allow adult stem cells to withstand metabolic stress and to preserve genome integrity over a lifetime. The quiescent state has long been viewed as a dormant and passive state of NSCs. However, accumulating evidence points to the opposite views. Recent single-cell transcriptome analysis of quiescent adult SGZ NSCs showed active expression of various receptors for niche signals and downstream signaling components [14], thus suggesting that quiescence is an actively maintained state. NSCs reside in a specialized local environment within the DG that consists of multiple distinct cell types, and signaling from these local cells can potentially control the key behavior of NSCs through the surface receptors expressed in NSCs. For instance, recent studies showed that local interneurons and mossy cells serve as critical niche components to regulate the activation versus quiescence state of the NSCs through the GABA (Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid) and glutamate receptors expressed in rNSCs, respectively [15, 16]. Besides local interneurons and mossy cells, ample evidence has demonstrated that NSCs are dynamically regulated by a barrage of niche signals [17] which may exert synergistic and antagonistic effects on rNSC regulation. This has raised a key question on how NSCs interpret diverse niche signals from the local environment to make the ultimate decision to stay in quiescence or become activated.

Fate decisions of NSCs

Two hallmarks of NSCs are their abilities to self-renew and generate differentiated neuronal or glial progeny [1]. The initial studies using in vitro expansion and differentiation of adult neural precursor cells have suggested that adult NSCs are capable of self-renewal and are tri-potent with the capacity to generate neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [18]. However, recent single-cell lineage tracing and fate-mapping of adult hippocampal NSCs in vivo have demonstrated the generation of neurons and astrocytes, but not oligodendrocytes [19] (Figure 1), thus highlighting different niche environment between in vitro and in vivo which dictates fate decisions of NSCs. Furthermore, these studies revealed a significant heterogeneity of individual adult NSCs in their fate choices, ranging from symmetric divisions for self-renewal to asymmetric divisions for generating neurons and/or astrocytes (Figure 1). Consistent with this notion, accumulating evidence has suggested that SGZ consists of NSCs with different morphologies [20] and behaviors in response to external stimuli [21]. With recent advance in microscope technology, it has become possible to directly image the behavior of individual adult NSCs in vivo for an extended period of time [22, 23]. Two-photon imaging analysis of individual NSCs in the adult mouse DG has revealed a new model which shows that radial NSCs typically undergo two to three cell divisions with initial symmetric or asymmetric divisions followed by a final self-depleting symmetric division generating two non-radial daughter cells [23, 24]. These findings are consistent with previous studies in fixed adult mouse brain sections revealing several rounds of neuronal differentiation followed by astroglial differentiation [25]. However, the other study showed that NSCs undergo long-term renewal [19]. This may be explained by the distinct NSC subtypes labeled by different NSC promoter driven Cre mouse lines: the in vivo imaging analysis traced Ascl1 (Achaete-scute complex-like 1)-expressing NSCs, whereas other NSC subtypes that do not express Ascl1 may be capable of long-term self-renewal.

Long-term maintenance of NSCs

Precise control of somatic stem cell properties is essential for the long-term maintenance of tissue homeostasis and has shown to be closely linked to tissue demands at any given time. The balance of NSC maintenance and neurogenesis is essential to ensure continuous generation of new hippocampal neurons throughout life without depleting the NSC pool. For example, the long-term consequence of excessive activation is subsequent depletion of the NSC compartment and impaired maintenance of NSCs, which ultimately leads to the loss of regenerative capacity of the NSC population and subsequent neuronal production in the adult hippocampus [26–28]. Therefore, the total NSC pool reflects a summation of NSC decisions over time: maintenance through quiescence or asymmetric self-renewal, reduction through terminal differentiation, and expansion through symmetric self-renewal. Under normal conditions, NSCs are mostly quiescent, but once activated, they undergo several rounds of cell division to produce neural progenitors followed by astrocytic differentiation, thus resulting in a progressive depletion of the NSC pool over time [25]. Utilizing in vivo clonal analysis for lineage tracing, NSCs were found to self-renew by generating copies of themselves. However, this mechanism for the repopulation of NSCs does not seem to counteract the depletion of the NSCs, occurring naturally over time. This could explain the age-dependent decline of the NSC pool in both rodents [25] and humans [4].

Functional roles of adult NSCs

Functions of adult-born neurons in the local hippocampal circuitry

When adult NSCs were initially discovered, it was proposed that their function was to provide a regenerative source for new neurons upon neurodegeneration and injury. Now it is widely accepted that the primary function of these endogenous adult NSCs is to confer an additional layer of plasticity to the mature brain via continuous addition of adult-born new neurons with unique properties. This raises a fundamental question: how is hippocampal activity modulated by continuous addition of newborn neurons?

It has been proposed that adult-born neurons could impact brain functions by serving as an active modulator of local circuitry to shape mature neuron firing, synchronization, and network oscillations [29]. It has become apparent that unique physiological properties of immature neurons allow them to participate differentially in the hippocampal network [30]. Immature neurons exhibit elevated excitability and plasticity compared to mature neurons during a critical time window between 4–6 weeks after birth [31, 32] [33] [34], suggesting that immature neurons have a privileged role in regulating hippocampal functions. Therefore, preferential recruitment of excitable immature neurons with enhanced plasticity would allow this population to be a major player in information processing within the trisynaptic hippocampal circuit. Adult-born neurons make synaptic contacts through the mossy fiber axons to the interneurons and pyramidal cells of the hippocampal CA3 region (Figure 2). The connectivity of the dentate granule cells and CA3 pyramidal cells is important for certain cognitive and memory functions [35]. The sparse connectivity between granule cells and CA3 cells was thought to be critical for pattern separation, a process by which overlapping or similar inputs are transformed into less similar outputs [36]. Immature neurons form connections first with the CA3 pyramidal cells and later with the local interneurons [37], suggesting that immature neurons preferentially excite pyramidal neurons thus bypassing feedforward inhibition mediated by interneurons. In contrast, mature neurons activate considerable feedforward inhibitory inputs onto the CA3 pyramidal cells thus suppressing their activation. Interestingly, during the critical window of 4 weeks after birth, new neurons transiently form strong anatomical, effective, and functional connections with local inhibitory circuits in CA3 [38]. Supporting the unique properties of adult-born neurons, a recent study using two-photon calcium imaging to monitor the activity of young adult-born neurons in awake behaving mice demonstrated that adult-born neurons fire at a higher rate in vivo but exhibit less spatial tuning than their mature counterparts when animals are presented with different contexts [39]. These findings highlight the unique role of adult-born neurons in context encoding and discrimination, consistent with their proposed role for pattern separation.

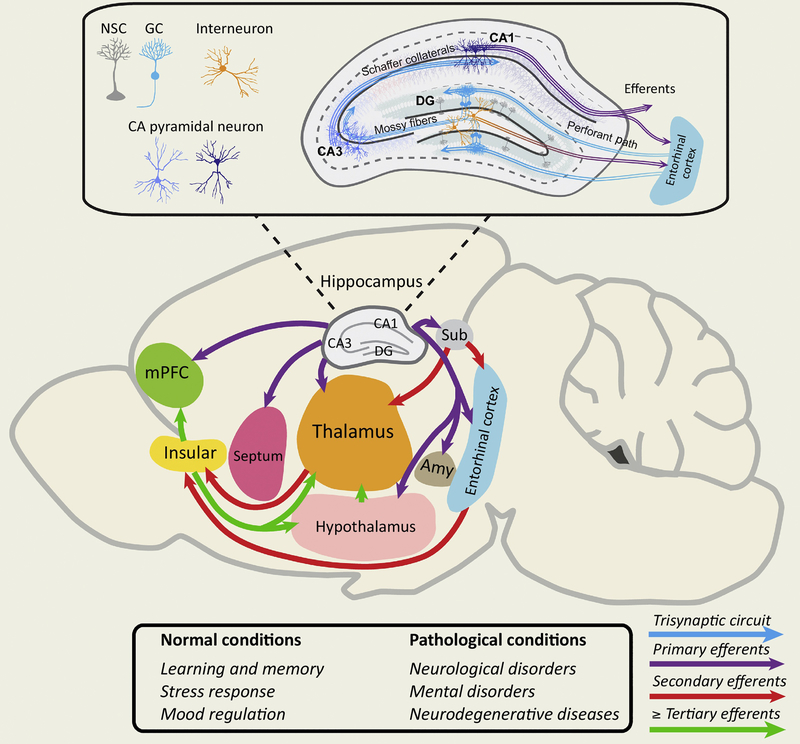

Figure 2: Potential outputs and functions of adult-born neurons in the dentate gyrus.

A schematic illustration of hippocampal circuit connectivity in the adult rodent brain. Newborn granule cells (GC) derived from NSCs receive inputs from entorhinal cortex through perforant path and make synaptic contacts with hilar interneurons and pyramidal cells of CA43 through mossy fibers, which further relay signals and information to CA1 pyramidal cells. These synaptic connections form a “tri-synaptic circuit” (blue arrows). Additionally, the hippocampus sends primary efferent projections (purple arrows) to multiple brain regions such as subiculum (sub), medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), septum nuclei, thalamus, hypothalamus, and amygdala (Amy). These brain regions could further send projections to target other brain regions, such as insular cortex, etc. (red and green arrows). Such broad connectivity from the hippocampus to other brain regions suggests that disruption of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may degrade optimal neuronal network dynamics, which in turn may contribute to pathological conditions, such as neurological disorders, mental disorders and neurodegenerative diseases.

Functions of adult-born neurons in the global network

Adult-born neurons not only could exert direct impact on the local hippocampal circuit through axonal projections from newborn neurons to their downstream CA regions, they could also exert indirect impact on the global neural network through axonal projections of newborn neurons to the local interneurons that project to other brain regions [40–43] (Figure 2). For instance, local somatostatin-expressing neurons can send long-distance projections to the medial septum (MS) and entorhinal cortex (EC), thus modulating the inhibitory tone and rhythmic activity in those target brain regions [44, 45]. These findings may account for the highly synchronized theta activity in the hippocampus, MS, and EC. Furthermore, the hippocampus has been shown to have significant functional connectivity with other brain regions through direct or indirect neuroanatomical connections, including (but not limited to) the prefrontal cortex, striatum, septum, amygdala, and insular cortex [41, 46–50]. Such broad connectivity from the hippocampus to other brain regions suggests that disruption of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may degrade optimal neuronal network dynamics, which in turn may shift large-scale brain activity changes to promote maladaptive states and contribute to the deficits associated with various brain disorders. Supporting this notion, recent studies demonstrated that disconnection of the hippocampus from other brain regions impairs animals’ performance on various learning-related tasks [51–53]. These findings raise the possibility that dysfunction of adult neurogenesis itself may play a causal role in various brain disorders and that adult neurogenesis could serve as a novel therapeutic target to prevent, ameliorate, or restore some of the cognitive and affective deficits associated with various brain diseases.

Functions of adult-born astroglia

Though adult NSCs primarily generate new neurons, the role of adult NSCs in brain function is now expanding beyond being a mere source of neuronal progeny. Besides generating neuronal progeny, adult NSCs also give rise to astroglia through asymmetric cell division (Figure 1). In the adult SGZ, astroglia exhibit horizontal and bushy morphology and express astrocyte markers including GFAP (Glial fibrillary acidic protein), S100β (S100 calcium binding protein B) and Aldh1l1(Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1 Family Member L1) [54]. Recent morphological studies using electron microscopy (EM) demonstrate that the radial processes of NSCs share vasculature with astrocytic processes and adhere to the adjacent processes of astrocytes [55], suggesting the potential functional interaction between NSCs and astrocytes. Under the normal condition, astroglia are not considered as neuronal precursors because they lack NSC marker expression, such as nestin [19, 25, 56]. However a small portion of astroglia are labeled with cell cycle markers and share many molecular similarities with NSCs such as Ascl1 [54, 57]. Interestingly, new astroglia are generated from NSCs in the adult SGZ before they migrate to the hilus or the molecular layer of the DG [19]. Under pathological conditions such as epilepsy that induces hippocampal hyperexcitability, NSCs become over-activated and generate reactive astrocytes with accompanying NSC pool depletion [58]. Though hippocampal SGZ NSCs generate astrocytes under both physiological and pathological conditions, the functions of newborn astrocytes remain largely unknown under these conditions. Astrocytes are connected by gap junctions and form networks that can modulate the surrounding neural circuitry activity and plasticity through gliotransmitters, including glutamate, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and D-serine [59]. Additionally, transcriptome analyses of reactive astrocytes shows that neuroinflammatory reactive astrocytes upregulate many genes shown to be destructive to synapses, such as complement cascade genes [60]. Therefore, the reactive astrocytes generated from NSCs under pathological conditions may negatively contribute to hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. Further studies are needed to determine the contribution of adult gliogenesis to brain functions in order to fully understand the functions of adult NSCs.

Direct contribution of NSCs to the neurogenic niche

It remains unknown whether adult SGZ NSCs (not their newborn progeny) make functional contributions to the hippocampal neurogenic niche. So far, no studies have exclusively manipulated SGZ NSCs for behavioral analysis. Therefore, the role of NSCs in regulating hippocampal network activity, hippocampal functions, and hippocampal neurogenesis remain largely unknown. It remains to be determined whether NSCs are capable of releasing potent chemicals such as gliotransmitters and other secretory molecules into the neurogenic niche, which could in turn influence both mature and newborn progeny. Supporting this view, in the other prominent neurogenic region, subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles, in the adult rodent brain, NSCs and their immediate progeny are found to secrete diazepam binding inhibitor, which antagonizes GABA signaling and promotes proliferation of neuroblasts through paracrine signaling [61]. In addition, NSCs might directly influence each other through autocrine signaling, NSCs in the adult SGZ express both the VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) receptor 3 and its ligand VEGF-C and VEGF receptor stimulation promotes NSC activation [62].

Adult NSCs in mediating brain disorders

Immediately after the initial discovery of neurogenesis in the postnatal rat hippocampus [63], Altman suggested that new neurons are critical for learning and memory. Since then, mounting evidence from sophisticated genetic approaches and computational modeling has implicated that adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays a central role in fine-tuned, spatially discrete memory processes and affective behaviors [34, 36, 64–66]. Furthermore, a substantial body of literature addresses changes of adult hippocampal neurogenesis mostly in rodents, in the context of various pathophysiological conditions, including aging, epilepsy, stroke, degenerative neurological disorders, and neuropsychiatric disorders [10, 11, 67, 68]. It remains unknown whether these changes represent adaptive responses to various pathological conditions, or are part of the pathophysiology that contributes to these conditions. Examples in animal models now suggest that dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may play a causal role in brain disorders with memory and mood deficits. Here we review recent studies that provide compelling evidence for the contribution of aberrant neurogenesis in various brain disorders, including epilepsy, mental disorders, and neurodevelopmental disorders.

Epilepsy

Recent studies have supported an emerging view that adult-born DG granule cells are directly involved in the pathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy, one of the most common human seizure-related disorders [69]. In animal models of epilepsy, pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus leads to a prolonged increase in dentate neural progenitor proliferation [70]. Additionally, newborn neurons born during and after epilepsy displayed aberrant synaptic integration, hilar basal dendrites with spines, ectopic hilar localization of the soma, and mossy fiber sprouting [71, 72]. These aberrant morphological features of DG granule neurons in mice are similar to what has been observed in postmortem dentate gyri of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy [69]. Eliminating cohorts of newborn neurons decreases status epilepticus–induced mossy fiber sprouting and ectopic granule cells [72]. Furthermore, genetic ablation of hippocampal newborn neurons immediately after status epilepticus induction effectively reduced the development of spontaneous recurrent seizures [73]. These studies suggest that aberrantly integrated new neurons contribute to the morphological abnormality of DG granule neurons and epilepsy. Separately, deletion of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome ten) in a small percentage of adult-born dentate granule cells is sufficient to cause spontaneous seizures within four weeks [74], suggesting that pathological changes in a small population of hippocampal adult-born neurons are sufficient to induce epilepsy. Collectively, these studies provide strong evidence that dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays a causal role in epileptogenesis.

Mental disorders

An increasing number of studies show that the behavioral symptoms typical for neuropsychiatric disorders can be produced by manipulating DG neurogenesis [9, 75]. One example is that retrovirus-mediated knockdown of Disrupted in Schizophrenia I (DISC1), a risk gene for major mental disorders including schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorders [76], leads to aberrant morphogenesis and integration of newborn dentate granule neurons in the adult mouse hippocampus due in part to hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway in newborn neurons [77–79]. Strikingly, dysregulated adult hippocampal neurogenesis following DISC1 knockdown in a cohort of retrovirally labeled newborn neurons is sufficient to cause cognitive and affective deficits, including pronounced learning and memory deficits (in the object-place recognition task and Morris water maze) and anxiety and depression-like phenotypes (in the forced-swim test and elevated plus maze). Inactivation of these aberrant new neurons reverses specific behavioral phenotypes, indicating a causal role for adult neurogenesis dysfunction in behavioral impairments.

It is now well-established that stress negatively regulates progenitor proliferation and new-neuron survival [80], whereas antidepressant treatments promote proliferation of neural progenitors and maturation of newborn neurons during adult hippocampal neurogenesis [10, 81]. Ablation of adult neurogenesis does not appear to alter affective behaviors at the basal level but abolishes some antidepressant-induced phenotypes in both rodents [82] and nonhuman primates [83]. Emerging evidence suggests a critical role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in the stress response by suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. In mice with adult neurogenesis ablated, mild stress leads to increased stress hormone level and greater stress responses [64, 84]. Furthermore, blockade of adult neurogenesis abolishes the antidepressant effect of hippocampal regulation of the HPA axis after chronic stress [85]. Interestingly, a recent study found that adult hippocampal neurogenesis confers resilience to chronic stress by inhibiting the activity of mature granule cells in the ventral dentate gyrus, a subregion implicated in mood regulation. This study provided a novel circuit mechanism by which adult-born neurons regulate DG information processing to protect from stress-induced anxiety-like behavior [86].

Intellectual disability

Fragile X syndrome, a neurodevelopmental disorder that leads to intellectual disability, is caused by the functional loss of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP). Fmrp null mice exhibit deficits in some forms of hippocampus-dependent learning, accompanied by reduced adult hippocampal neurogenesis due to impaired neuronal differentiation and survival [87]. Genetic deletion of Fmrp selectively in NSCs and their progeny results in defects in both adult neurogenesis and hippocampus-dependent learning. Furthermore, restoration of Fmrp expression in NSCs and their progeny is sufficient to rescue the learning deficits in Fmrp null mice [88]. These striking results suggest a critical role for adult neurogenesis dysfunction in learning impairments associated with fragile X syndrome. Whether this is generalizable to other neurodevelopmental disorders (such as autism spectrum disorder) remains to be determined.

Though these studies have provided compelling evidence for the critical role of aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis in brain disorders, the mechanisms by which aberrant adult-born neurons contribute to impaired brain functions are largely unknown. Future studies will be needed to dissect the circuit and signaling mechanisms underlying this interaction.

Targeting NSCs and their niche in treating brain disorders

The promise of endogenous NSCs for the development of novel therapeutic strategies lies in the regenerative properties of NSCs that allow them to repair the damaged and diseased brain. Yet such strategies must consider and address biological constraints imposed by both NSCs and their local environment. To harness the brain’s endogenous capacity to generate hippocampal NSCs as a potential therapeutic strategy, it is necessary to understand the properties of NSCs and their local microenvironment (also termed as “niche”) supporting NSCs to proliferate and differentiate. The intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms underlying adult NSC regulation have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [2, 13, 17, 89, 90]. Activity-dependent adult NSC regulation is proposed such that extrinsic niche signals activate NSC surface receptors that in turn trigger a signaling cascade that activates intracellular signaling cascades to control the key behaviors of adult NSCs. Here we propose that strategies aimed at simultaneously correcting both NSCs (Figure 3) and their niche (Figure 4) would be likely to provide more effective treatments as compared to targeting only one of these aspects. Supporting this view, a recent study showed that increasing hippocampal neurogenesis along with BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor) overexpression mimics the effects of exercising on cognitive improvement in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [91], suggesting that promoting neurogenesis in an improved niche environment can ameliorate AD-associated cognitive deficits. This timely report highlights the importance of the combination of healthy neurogenic niche and increased neurogenesis for improving hippocampus-dependent cognitive functions.

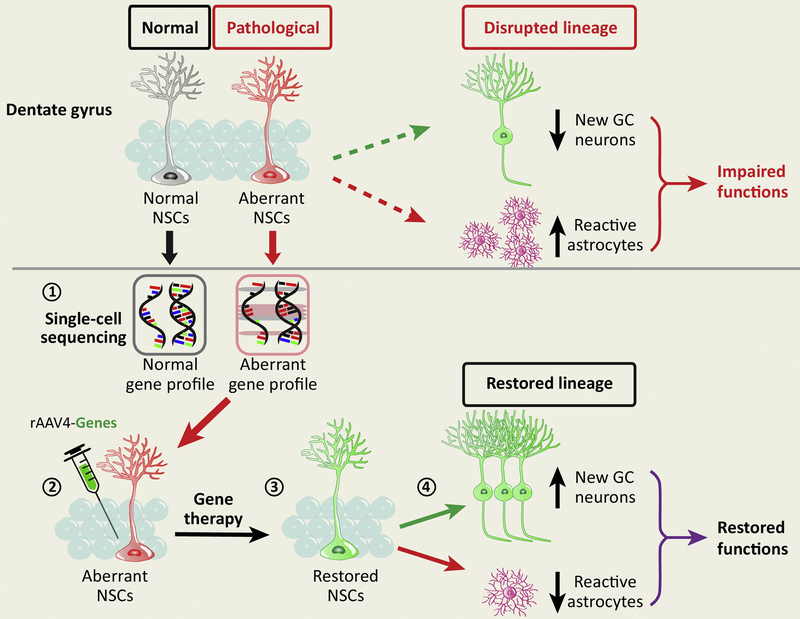

Figure 3: Targeting adult hippocampal NSCs in treating brain disorders.

Under pathological conditions, aberrant NSCs exhibit disrupted lineage, resulting in decreased number of newborn neurons, increased number of reactive astrocytes, and impaired brain functions. To correct the deficits, we illustrate a strategy to target NSCs for treating brain disorders: 51) The gene profiles can be obtained and then compared via single-cell sequencing analyses under both normal and pathological conditions. 2) Candidate genes will be selected to target NSCs using the rAAV4 vector with selective tropism to NSCs. 3) By manipulating a set of candidate genes to increase and/or decrease their expression in NSCs, the functions of NSCs are expected to be restored. 4) Restored NSCs are expected to exhibit increased number of newborn neurons and decreased number of reactive astrocytes, which in turn lead to restored brain functions.

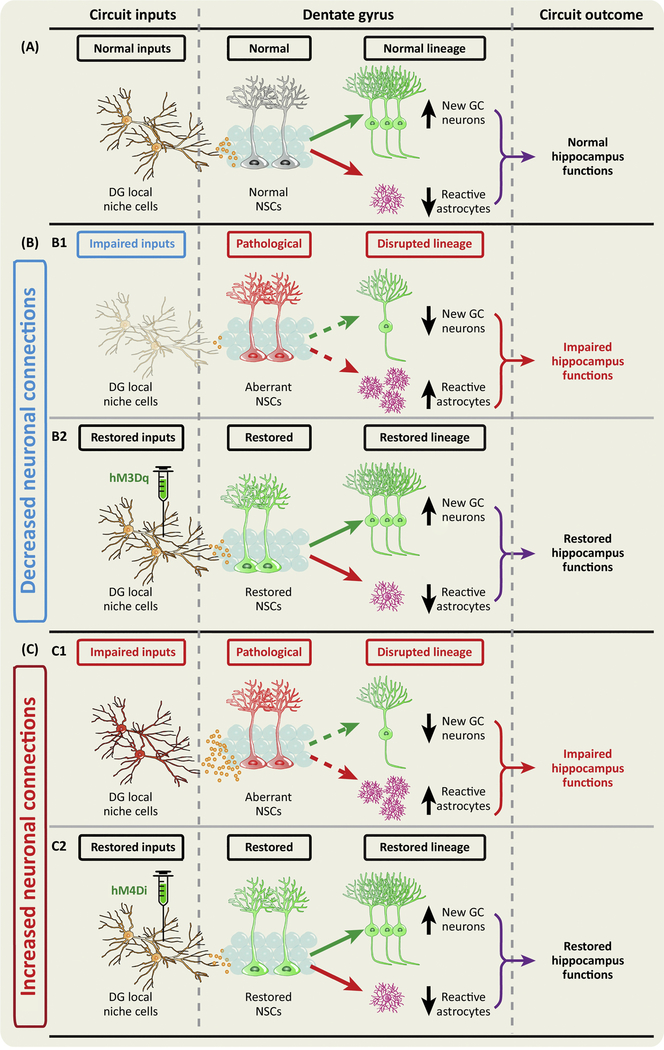

Figure 4: Targeting adult hippocampal NSC niche in treating brain disorders.

Here we illustrate a strategy for treating brain disorders by targeting the local niche cells in order to create an improved neurogenic niche which could lead to healthy neurogenesis and cognitive improvement. (A) Under normal condition, local niche cells maintain the proper neurogenic niche activity, thus providing a healthy niche environment for neurogenesis and hippocampal functions. (B–C) Under pathological conditions, neuronal connections could either be weakened due to potential neuronal death or degeneration of the nerve terminals (B1), or enhanced due to increased neural transmission or overgrowth of nerve terminals to their postsynaptic targets (C1), thus leading to impaired neurogenesis and hippocampal functions. To repair these deficits, we propose to target specific niche cells using DREADDs in order to modulate their activity. Specifically, excitatory DREADDs (hM3q) or inhibitory DREADDs (hM4Di) can be delivered through viral gene therapy to the Dentate Gyrus (DG), so that the DREADDs-expressing neurons can be stimulated or inhibited through the administration of an inert ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). Stimulating the hM3Dq-expressing neurons under pathological decreased neuronal connections (B2) or inhibiting the hM4Di-expressing neurons under pathological increased neuronal connections (C2) will lead to restored hippocampal neurogenesis and improved hippocampal functions.

Targeting adult hippocampal NSCs in treating brain disorders

Adult NSCs are difficult to study because they are rare and heterogeneous. To date, various viral and transgenic strategies have been developed to target and genetically manipulate adult hippocampal NSCs [92]. These approaches have undoubtedly revolutionized our understanding of developmental processes during adult hippocampal neurogenesis. However, a number of limitations in these approaches prevent efficient targeting of NSCs. For instance, classical oncoretroviral mediated labeling approaches require active cell proliferation, thus preferentially labeling proliferating neural precursors and progenitors, not quiescent rNSCs [2, 93, 94]. Additionally, lentivirus and adenovirus with a NSC specific promoter (Sox2 and GFAP) have been used to target NSCs [94, 95], but the targeting specificity is a concern as almost all of the NSC promoters are also active in the astroglia lineage thus also labeling a substantial number of astrocytes as the starting population. Transgenic approaches using indelible labeling of NSCs and their progeny are the most commonly used strategies to target NSCs for lineage tracing, which requires the generation of double transgenic animals with the combination of a NSC-specific Cre recombinase and a floxed reporter gene. Furthermore, to manipulate gene(s) regulating NSCs in a cell-autonomous fashion, it requires generation of mice with multiple transgenes harboring NSC-specific Cre recombinase, floxed reporter gene, and floxed gene(s) of interest. Besides the prolonged animal generation time for multiple transgenes, the transgenic strategy is difficult for immediate translation in genetically intractable animal species including humans. Therefore, developing a readily manufactured viral vector that allows flexible packaging of transgenes and supports high-level transgene expression selectively in NSCs is a pressing need for efficient targeting and manipulations of NSCs in both genetically tractable and intractable animal species. Recently, Crowther et al. have developed a recombinant adeno-associated virus serotype 4 (rAAV4) based vector with highly selective tropism in adult SGZ NSCs [96]. They demonstrated that rAAV4 mediated expression is specific and robust in NSCs, thus holding promise for gene therapy by selectively targeting NSCs for treating human patients with hippocampal dysfunction. Currently, a major gap in targeting adult hippocampal NSCs to treat neurological and mental disorders is the lack of molecular profiles of adult hippocampal NSCs associated with these diseased conditions. However, with recent success in single-cell RNA-sequencing of adult SGZ NSCs [14] and adult SVZ NSCs upon brain injuries [97], this gap will be filled in the near future. In particular, these studies will reveal molecularly distinct groups of NSCs that respond differentially to various physiological or pathological stimuli in the adult neurogenic niche. Therefore, the discovery of unique molecular targets from unbiased gene profiling at the single-cell level associated with pathological conditions will lead to novel therapeutics by selectively targeting endogenous NSCs (Figure 3).

The non-Cre dependent AAV4 system holds great promise in its application as a research tool for studying adult NSCs and as a potential gene therapy platform for treating some functional domains in brain disorders arising from aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis, such as diseases with memory and mood deficits including epilepsy, major depression, and Alzheimer’s disease. However, the concern for this system is the episomal dilution associated with neural stem/progenitor cell division [98] which could lead to underestimation of the production of neuronal progeny derived from NSCs in the context of stem cell biology and insufficient labeling of NSCs to achieve functional recovery in the context of gene therapy application. Future studies by incorporating the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system into the non-Cre dependent AAV4 delivery system will circumvent this issue and achieve permanent genome editing.

While the prospect of using adult NSCs therapeutically as a regenerative source for neural repair is very exciting, a major issue that must be addressed is the functional consequences of new neuron generation, especially under the pathological conditions. Vigorous examination of neuronal integration and the impact of new neurons on the surrounding neuronal circuitry will be imperative for this line of research to be clinically relevant.

Targeting adult hippocampal NSC niche in treating brain disorders

Activity-dependent regulation of NSCs by local niche cells

A growing body of data in many tissue systems indicates that stem cell function is critically influenced by the microenvironment in which stem cells reside. Therefore, the stem cell niche represents a critical entry point for therapeutic modulation of stem cell behavior. In addition to classic niche factors described for other somatic stem cell compartments, such as morphogens and growth factors [17], dynamic regulation by ongoing network activity is a hallmark of adult neurogenesis [1, 2, 90, 99]. NSCs and their progeny reside in a specialized local environment that consists of a diverse group of local cells with distinct molecular, morphological, and functional properties [100], and signaling from these local cells can potentially control the NSC niche activity and key behavior of NSCs. Despite lacking synapses, NSCs “listen to” the neural network and take proper actions in response to ongoing network activity [90]. For instance, recent studies identified local parvalbumin-expressing (PV) interneurons and mossy cells (MCs) as critical niche cells in regulating DG network activity and the key behaviors of NSCs in vivo [15, 16, 101]. While DG PV interneurons and mossy cells release GABA and glutamate as their main neurotransmitters, respectively, many local interneurons co-release neuropeptides. Neuropeptides are neuromodulators, therefore, exert broad actions on multiple types of local niche cells. This raised an important question on how endogenous neuropeptides control NSC niche activity and key behavior of NSCs at the neural circuit level.

Targeting local niche cells for treating brain disorders

Local interneurons and mossy cells in the hippocampal circuit have been shown to correlate with many physiological and pathological conditions, such as aging, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), chronic stress, schizophrenia, and epilepsy [102, 103]. This thus suggests that these local niche cells may be vulnerable to certain pathological conditions which in turn may contribute to aberrant neurogenesis and impaired cognitive functions. For instance, local GABA interneuron dysfunction and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis have been observed in AD [104, 105] and several forms of neuropsychiatric disorders [9, 102]. In addition, MC dysfunction and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis have been reported in mouse models of temporal lobe epilepsy [58, 70, 106]. These findings suggest that targeting local niche cells may provide a strategy to restore hippocampal neurogenesis by creating a permissive niche environment for NSCs to generate healthy neurons. To elaborate this view, here we illustrate a strategy for treating brain disorders by targeting the local niche cells in order to create an improved neurogenic niche which could lead to healthy neurogenesis and cognitive improvement (Figure 4). Under pathological conditions, neuronal connections could either be weakened due to potential neuronal death or degeneration of the nerve terminals, or enhanced due to increased neural transmission or overgrowth of nerve terminals to their postsynaptic targets, Therefore, manipulating the activity of specific niche cell types under diseased conditions can provide an efficient strategy to restore neurogenic niche activity and promote healthy neurogenesis. Recent success in rAAV-mediated targeting of local interneurons through Dlx enhancer in non-genetically tractable species [107] and the advent of the chemogenetic approach using Designer Receptors Exclusively Activated by Designer Drugs (DREADDs) to manipulate the activity of specific neuronal cell types and circuits provide such a possibility [108], though the safety of expressing viruses in human neurons remains to be tested for extended period of time (> 10 years). Nevertheless, DREADDs can be delivered through viral gene therapy to the hippocampus, and the DREADDs-expressing neurons can be stimulated or inhibited through the administration of an inert ligand clozapine-N-oxide (CNO). Despite the undisputed success of CNO as an activator of muscarinic DREADDs, it has been known for some time that CNO is subject to a low rate of metabolic conversion to clozapine which exhibits high DREADD affinity and potency in vivo [109]. To address this concern, a new DREADD agonist C21 has been developed [110]. C21 has been characterized to be a potent and selective agonist at both excitatory and inhibitory DREADDs and has excellent bioavailability, pharmacokinetic properties, and brain penetrability, therefore, has great translational potential for human application.

Concluding remarks

Adult NSCs and neurogenesis confer a unique mode of plasticity in the mature mammalian brain. One overarching goal of adult neurogenesis research is to manipulate NSCs to improve brain health. Although we have gained tremendous understanding of adult NSCs and their niche in the past decade, many questions remain (see Outstanding Questions). To take advantage of the regenerative capacity of adult NSCs, we need to continue our efforts in investigating and manipulating NSC regulatory mechanisms to enhance functional regeneration and repair of the adult brain, particularly, in the context of pathological conditions. Future research will benefit from identification of NSC subpopulation specific markers via single-cell sequencing analysis to dissect properties and unique responses from subpopulations of NSCs that are responsive to certain brain pathology or injury. Moreover, the endogenous recovery capacity in the adult brain is rather limited under pathological conditions or following injury, likely due to the lack of permissive niche environment for neuroregeneration. Future research will need to focus on interactions between signaling pathways mediated by distinct neural circuits to identify circuit and signaling hubs and the hierarchy that coordinates the barrage of incoming signals. In addition, although human and rodents share the same neurogenic region, i.e. the hippocampus, there are many differences between human and rodent neurogenesis. Future development of non-invasive tools that can selectively target and track human NSCs would bring us one step closer to the application of adult NSCs to treat human diseases.

Highlights.

Endogenous NSCs in the adult hippocampus hold promise in treating brain disorders with memory and mood deficits.

Adult NSCs confer additional plasticity to the mature brain via continuous generation and addition of newborn neurons with unique properties.

Aberrant NSCs and hippocampal neurogenesis contribute to various brain disorders.

Developing therapeutic strategies targeting both endogenous NSCs and NSC niche to treat brain disorders.

Outstanding Questions.

What are the critical features that make the adult neurogenic niche receptive to maintain NSCs and promote neurogenesis?

What are the cellular targets of various physiological and pathological stimuli in the neurogenic niche?

What are the functional consequences of newborn progeny derived from NSCs including both neuronal and glial progeny?

How do adult NSCs integrate diverse niche signals to make ultimate decisions to stay quiescent or become activated and make fate decisions for symmetric or asymmetric cell divisions?

What are the molecular identities of distinct groups of adult NSCs that differentially respond to various pathological stimuli?

What are the differences in adult hippocampal neurogenesis between rodents and humans?

How to identify and track adult NSCs and neurogenesis in humans?

Clinician’s Corner.

-

-

Adult hippocampal neurogenesis has garnered significant interest because of its potential to influence information processing in the medial temporal lobe, a brain region for many forms of learning and memory and a site of pathophysiology associated with various neurological disorders.

-

-

Many studies have implicated dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in an increasing number of human brain disorders, such as epilepsy, major depression, and neurodegenerative diseases.

-

-

Dentate granule cells may play a central role in the pathogenesis of temporal lobe epilepsy, one of the most common human seizure-related disorders. Recent studies in animal models provide strong evidence that dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis plays a causal role in epileptogenesis.

-

-

Accumulating evidence has suggested that dysfunction of adult hippocampal neurogenesis may play a causal role in psychiatric symptomatology and that adult neurogenesis could serve as a novel therapeutic target, particularly in light of the findings related to neurogenesis-mediated effects of antidepressants.

-

-

A recent study demonstrated that increasing hippocampal neurogenesis along with BDNF overexpression mimic the effect of exercising on cognitive improvement in an AD mouse model, suggesting that promoting neurogenesis in an improved niche environment can ameliorate AD pathology and cognitive deficits.

Acknowledgements

We apologize for not being able to cite many original papers because constrains on reference numbers. This work was supported by grants awarded to J.S. from Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, American Heart Association, Whitehall Foundation, and NIH (MH111773, AG058160).

Glossary

- Asymmetric division

the process of neural stem cells giving rise to a daughter cell identical to the mother cell and a second cell with a different cell type.

- Autocrine signaling

the production and secretion of an extracellular mediator by a cell followed by the binding of that mediator to receptors on the same cell to initiate signal transduction.

- Brain plasticity

is the ability of the brain to change based on different activities.

- Chemogenetics

the technique that using small novel molecules to activate genetic engineered receptors.

- Clonal analysis

a study observing clones derived from single cells.

- Dlx

Dlx family genes encode homeodomain transcription factors related to the Drosophila distalless (Dll) gene. Dlx5/6 genes are specifically expressed by all forebrain GABAergic interneurons during embryonic development.

- D-serine

synthesized in neurons, it serves as a neuromodulator by coactivating NMDA receptors, making them able to open if they then also bind glutamate.

- Episomal dilution

DNA molecules replicate independently of chromosomal DNA will dilute after cell division.

- Feedforward inhibition

collateral branches of the excitatory afferent fibers that excite inhibitory interneurons that in turn inhibit neurons in the forward direction.

- GABA

the chief inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system, and acts on GABAA or GABAB receptors.

- Glutamate

the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system, and acts on NMDA, Kainate, AMPA or metabotropic Glutamate receptors.

- HPA axis

a major neuroendocrine system that controls reactions to stress and regulates body functions.

- Interneurons

form GABAergic synapses to inhibit their target neurons.

- Lineage tracing

identification of all progeny of a single cell.

- Mossy cells

glutamatergic principal cells with spiny dendrites in dentate hilus.

- Mossy fiber axons

unmyelinated axons projecting from dentate granule cells that terminate on hilar mossy cells and CA3 region in the hippocampus.

- mTOR pathway

a signaling pathway that serves as a central regulator of cell metabolism, growth, proliferation and survival.

- Oscillations

rhythmic or repetitive patterns of neural activity in the central nervous system, that enable synchronization of neural activity across brain regions.

- Paracrine signaling

a form of cell-to-cell communication in which a cell produces a signal to induce changes in nearby cells, altering the behavior of those cells.

- Pattern separation

the process of making similar patterns of neural activity more distinct.

- Symmetric division

The process of neural stem cells generating two daughter cells with the same fate.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zhao C, et al. (2008) Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell 132, 645–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ming GL and Song H (2011) Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian brain: significant answers and significant questions. Neuron 70, 687–702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spalding KL, et al. (2013) Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell 153, 1219–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boldrini M, et al. (2018) Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell stem cell 22, 589–599 e585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kempermann G, et al. (2018) Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell stem cell 23, 25–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng W, et al. (2010) New neurons and new memories: how does adult hippocampal neurogenesis affect learning and memory? Nature reviews. Neuroscience 11, 339–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian KM, et al. (2014) Functions and dysfunctions of adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Annual review of neuroscience 37, 243–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahay A, et al. (2011) Pattern separation: a common function for new neurons in hippocampus and olfactory bulb. Neuron 70, 582–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang E, et al. (2016) Adult Neurogenesis and Psychiatric Disorders. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahay A and Hen R (2007) Adult hippocampal neurogenesis in depression. Nature neuroscience 10, 1110–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winner B, et al. (2011) Neurodegenerative disease and adult neurogenesis. The European journal of neuroscience 33, 1139–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sorrells SF, et al. (2018) Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 555, 377–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bond AM, et al. (2015) Adult Mammalian Neural Stem Cells and Neurogenesis: Five Decades Later. Cell stem cell 17, 385–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shin J, et al. (2015) Single-Cell RNA-Seq with Waterfall Reveals Molecular Cascades underlying Adult Neurogenesis. Cell stem cell 17, 360–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song J, et al. (2012) Neuronal circuitry mechanism regulating adult quiescent neural stem-cell fate decision. Nature 489, 150–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yeh CY, et al. (2018) Mossy Cells Control Adult Neural Stem Cell Quiescence and Maintenance through a Dynamic Balance between Direct and Indirect Pathways. Neuron [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Ma DK, et al. (2009) Activity-dependent extrinsic regulation of adult olfactory bulb and hippocampal neurogenesis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1170, 664–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer TD, et al. (1997) The adult rat hippocampus contains primordial neural stem cells. Molecular and cellular neurosciences 8, 389–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonaguidi MA, et al. (2011) In vivo clonal analysis reveals self-renewing and multipotent adult neural stem cell characteristics. Cell 145, 1142–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gebara E, et al. (2016) Heterogeneity of Radial Glia-Like Cells in the Adult Hippocampus. Stem cells 34, 997–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lugert S, et al. (2010) Quiescent and active hippocampal neural stem cells with distinct morphologies respond selectively to physiological and pathological stimuli and aging. Cell stem cell 6, 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbosa JS, et al. (2015) Neurodevelopment. Live imaging of adult neural stem cell behavior in the intact and injured zebrafish brain. Science 348, 789–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pilz GA, et al. (2018) Live imaging of neurogenesis in the adult mouse hippocampus. Science 359, 658–662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gotz M (2018) Revising concepts about adult stem cells. Science 359, 639–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Encinas JM, et al. (2011) Division-coupled astrocytic differentiation and age-related depletion of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell stem cell 8, 566–579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ehm O, et al. (2010) RBPJkappa-dependent signaling is essential for long-term maintenance of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 13794–13807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mira H, et al. (2010) Signaling through BMPR-IA regulates quiescence and long-term activity of neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell stem cell 7, 78–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao Z, et al. (2011) The master negative regulator REST/NRSF controls adult neurogenesis by restraining the neurogenic program in quiescent stem cells. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 31, 9772–9786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song J, et al. (2012) Modification of hippocampal circuitry by adult neurogenesis. Developmental neurobiology 72, 1032–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dieni CV, et al. (2012) Dynamic functions of GABA signaling during granule cell maturation. Frontiers in neural circuits 6, 113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ge S, et al. (2007) A critical period for enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated neurons of the adult brain. Neuron 54, 559–566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmidt-Hieber C, et al. (2004) Enhanced synaptic plasticity in newly generated granule cells of the adult hippocampus. Nature 429, 184–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kee N, et al. (2007) Preferential incorporation of adult-generated granule cells into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nature neuroscience 10, 355–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gu Y, et al. (2012) Optical controlling reveals time-dependent roles for adult-born dentate granule cells. Nature neuroscience 15, 1700–1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Treves A and Rolls ET (1992) Computational constraints suggest the need for two distinct input systems to the hippocampal CA3 network. Hippocampus 2, 189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aimone JB, et al. (2011) Resolving new memories: a critical look at the dentate gyrus, adult neurogenesis, and pattern separation. Neuron 70, 589–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Temprana SG, et al. (2015) Delayed coupling to feedback inhibition during a critical period for the integration of adult-born granule cells. Neuron 85, 116–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Restivo L, et al. (2015) Development of Adult-Generated Cell Connectivity with Excitatory and Inhibitory Cell Populations in the Hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35, 10600–10612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danielson NB, et al. (2016) Distinct Contribution of Adult-Born Hippocampal Granule Cells to Context Encoding. Neuron 90, 101–112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Verschure PF, et al. (2014) The why, what, where, when and how of goal-directed choice: neuronal and computational principles. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences 369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tannenholz L, et al. (2014) Local and regional heterogeneity underlying hippocampal modulation of cognition and mood. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience 8, 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu X, et al. (2016) Noncanonical connections between the subiculum and hippocampal CA1. The Journal of comparative neurology 524, 3666–3673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gogolla N (2017) The insular cortex. Current biology : CB 27, R580–R586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melzer S, et al. (2012) Long-range-projecting GABAergic neurons modulate inhibition in hippocampus and entorhinal cortex. Science 335, 1506–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan M, et al. (2017) Somatostatin-positive interneurons in the dentate gyrus of mice provide local-and long-range septal synaptic inhibition. eLife 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Albouy G, et al. (2013) Hippocampus and striatum: dynamics and interaction during acquisition and sleep-related motor sequence memory consolidation. Hippocampus 23, 985–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thierry AM, et al. (2000) Hippocampo-prefrontal cortex pathway: anatomical and electrophysiological characteristics. Hippocampus 10, 411–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller C and Remy S (2018) Septo-hippocampal interaction. Cell and tissue research 373, 565–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sotres-Bayon F, et al. (2012) Gating of fear in prelimbic cortex by hippocampal and amygdala inputs. Neuron 76, 804–812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghaziri J, et al. (2018) Subcortical structural connectivity of insular subregions. Scientific reports 8, 8596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang GW and Cai JX (2006) Disconnection of the hippocampal-prefrontal cortical circuits impairs spatial working memory performance in rats. Behav Brain Res 175, 329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang GW and Cai JX (2008) Reversible disconnection of the hippocampal-prelimbic cortical circuit impairs spatial learning but not passive avoidance learning in rats. Neurobiol Learn Mem 90, 365–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Floresco SB, et al. (1997) Selective roles for hippocampal, prefrontal cortical, and ventral striatal circuits in radial-arm maze tasks with or without a delay. J Neurosci 17, 1880–1890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seri B, et al. (2004) Cell types, lineage, and architecture of the germinal zone in the adult dentate gyrus. The Journal of comparative neurology 478, 359–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moss J, et al. (2016) Fine processes of Nestin-GFP-positive radial glia-like stem cells in the adult dentate gyrus ensheathe local synapses and vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, E2536–2545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Steiner B, et al. (2004) Differential regulation of gliogenesis in the context of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Glia 46, 41–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim EJ, et al. (2011) Ascl1 (Mash1) defines cells with long-term neurogenic potential in subgranular and subventricular zones in adult mouse brain. PloS one 6, e18472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sierra A, et al. (2015) Neuronal hyperactivity accelerates depletion of neural stem cells and impairs hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell stem cell 16, 488–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Araque A, et al. (2014) Gliotransmitters travel in time and space. Neuron 81, 728–739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liddelow SA and Barres BA (2017) Reactive Astrocytes: Production, Function, and Therapeutic Potential. Immunity 46, 957–967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alfonso J, et al. (2012) Diazepam binding inhibitor promotes progenitor proliferation in the postnatal SVZ by reducing GABA signaling. Cell stem cell 10, 76–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Han J, et al. (2015) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3 controls neural stem cell activation in mice and humans. Cell reports 10, 1158–1172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altman J and Das GD (1965) Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. The Journal of comparative neurology 124, 319–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snyder JS, et al. (2011) Adult hippocampal neurogenesis buffers stress responses and depressive behaviour. Nature 476, 458–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Akers KG, et al. (2014) Hippocampal neurogenesis regulates forgetting during adulthood and infancy. Science 344, 598–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sahay A, et al. (2011) Increasing adult hippocampal neurogenesis is sufficient to improve pattern separation. Nature 472, 466–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kempermann G (2015) Activity Dependency and Aging in the Regulation of Adult Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Parent JM (2003) Injury-induced neurogenesis in the adult mammalian brain. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry 9, 261–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Houser CR (1992) Morphological changes in the dentate gyrus in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy research. Supplement 7, 223–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parent JM, et al. (1997) Dentate granule cell neurogenesis is increased by seizures and contributes to aberrant network reorganization in the adult rat hippocampus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 17, 3727–3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jessberger S, et al. (2007) Seizure-associated, aberrant neurogenesis in adult rats characterized with retrovirus-mediated cell labeling. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27, 9400–9407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kron MM, et al. (2010) The developmental stage of dentate granule cells dictates their contribution to seizure-induced plasticity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 30, 2051–2059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cho KO, et al. (2015) Aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis contributes to epilepsy and associated cognitive decline. Nature communications 6, 6606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pun RY, et al. (2012) Excessive activation of mTOR in postnatally generated granule cells is sufficient to cause epilepsy. Neuron 75, 1022–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Yun S, et al. (2016) Re-evaluating the link between neuropsychiatric disorders and dysregulated adult neurogenesis. Nature medicine 22, 1239–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thomson PA, et al. (2013) DISC1 genetics, biology and psychiatric illness. Frontiers in biology 8, 1–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Duan X, et al. (2007) Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 regulates integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Cell 130, 1146–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim JY, et al. (2009) DISC1 regulates new neuron development in the adult brain via modulation of AKT-mTOR signaling through KIAA1212. Neuron 63, 761–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim JY, et al. (2012) Interplay between DISC1 and GABA signaling regulates neurogenesis in mice and risk for schizophrenia. Cell 148, 1051–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gould E, et al. (1992) Adrenal hormones suppress cell division in the adult rat dentate gyrus. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 12, 3642–3650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Warner-Schmidt JL and Duman RS (2006) Hippocampal neurogenesis: opposing effects of stress and antidepressant treatment. Hippocampus 16, 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santarelli L, et al. (2003) Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 301, 805–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perera TD, et al. (2011) Necessity of hippocampal neurogenesis for the therapeutic action of antidepressants in adult nonhuman primates. PloS one 6, e17600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schloesser RJ, et al. (2009) Suppression of adult neurogenesis leads to an increased hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis response. Neuroreport 20, 553–557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Surget A, et al. (2011) Antidepressants recruit new neurons to improve stress response regulation. Molecular psychiatry 16, 1177–1188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Anacker C, et al. (2018) Hippocampal neurogenesis confers stress resilience by inhibiting the ventral dentate gyrus. Nature 559, 98–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Luo Y, et al. (2010) Fragile x mental retardation protein regulates proliferation and differentiation of adult neural stem/progenitor cells. PLoS genetics 6, e1000898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guo W, et al. (2011) Ablation of Fmrp in adult neural stem cells disrupts hippocampus-dependent learning. Nature medicine 17, 559–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Crowther AJ and Song J (2014) Activity-dependent signaling mechanisms regulating adult hippocampal neural stem cells and their progeny. Neuroscience bulletin 30, 542–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Song J, et al. (2016) Neuronal Circuitry Mechanisms Regulating Adult Mammalian Neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Choi SH, et al. (2018) Combined adult neurogenesis and BDNF mimic exercise effects on cognition in an Alzheimer’s mouse model. Science 361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Enikolopov G, et al. (2015) Viral and transgenic reporters and genetic analysis of adult neurogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 7, a018804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Breunig JJ, et al. (2007) Everything that glitters isn’t gold: a critical review of postnatal neural precursor analyses. Cell stem cell 1, 612–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suh H, et al. (2007) In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell stem cell 1, 515–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rolando C, et al. (2016) Multipotency of Adult Hippocampal NSCs In Vivo Is Restricted by Drosha/NFIB. Cell stem cell 19, 653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Crowther AJ, et al. (2018) An Adeno-Associated Virus-Based Toolkit for Preferential Targeting and Manipulating Quiescent Neural Stem Cells in the Adult Hippocampus. Stem cell reports [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 97.Llorens-Bobadilla E, et al. (2015) Single-Cell Transcriptomics Reveals a Population of Dormant Neural Stem Cells that Become Activated upon Brain Injury. Cell stem cell 17, 329–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schultz BR and Chamberlain JS (2008) Recombinant adeno-associated virus transduction and integration. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy 16, 1189–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kriegstein A and Alvarez-Buylla A (2009) The glial nature of embryonic and adult neural stem cells. Annu Rev Neurosci 32, 149–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Houser CR (2007) Interneurons of the dentate gyrus: an overview of cell types, terminal fields and neurochemical identity. Progress in brain research 163, 217–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bao H, et al. (2017) Long-Range GABAergic Inputs Regulate Neural Stem Cell Quiescence and Control Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Cell stem cell 21, 604–617 e605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Marin O (2012) Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 13, 107–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Scharfman HE (2016) The enigmatic mossy cell of the dentate gyrus. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 17, 562–575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li G, et al. (2009) GABAergic interneuron dysfunction impairs hippocampal neurogenesis in adult apolipoprotein E4 knockin mice. Cell stem cell 5, 634–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sun B, et al. (2009) Imbalance between GABAergic and Glutamatergic Transmission Impairs Adult Neurogenesis in an Animal Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell stem cell 5, 624–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bui AD, et al. (2018) Dentate gyrus mossy cells control spontaneous convulsive seizures and spatial memory. Science 359, 787–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dimidschstein J, et al. (2016) A viral strategy for targeting and manipulating interneurons across vertebrate species. Nature neuroscience 19, 1743–1749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Armbruster BN, et al. (2007) Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104, 5163–5168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gomez JL, et al. (2017) Chemogenetics revealed: DREADD occupancy and activation via converted clozapine. Science 357, 503–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Thompson KJ, et al. (2018) DREADD Agonist 21 Is an Effective Agonist for Muscarinic-Based DREADDs in Vitro and in Vivo. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 1, 61–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]