Abstract

Objective:

Neuropathological studies have demonstrated that cerebrovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology frequently co-occur in older adults. The extent to which cerebrovascular disease influences the progression of AD pathology remains unclear. Leveraging newly available positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, we examined whether a well-validated measure of systemic vascular risk and β-amyloid (Aβ) burden have an interactive association with regional tau burden.

Methods:

Vascular risk was quantified at baseline in 152 clinically normal older adults (mean age=73.5±6.1 years) with the office-based Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk algorithm (FHS-CVD). We acquired Aβ (11C-Pittsburgh Compound-B) and tau (18F-Flortaucipir) PET imaging on the same participants. Aβ PET was performed at baseline; tau PET was acquired on average 2.98±1.1 years later. Tau was measured in the entorhinal cortex (EC), an early site of tau deposition, and in the inferior temporal cortex (ITC), an early site of neocortical tau accumulation associated with AD. Linear regression models examined FHS-CVD and Aβ as interactive predictors of tau deposition, adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan.

Results:

We observed a significant interaction between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden on subsequently measured ITC tau (p<0.001), whereby combined higher FHS-CVD and elevated Aβ burden was associated with increased tau. The interaction was not significant for EC tau (p=0.16).

Interpretation:

Elevated vascular risk may influence tau burden when coupled with high Aβ burden. These results suggest a potential link between vascular risk and tau pathology in preclinical AD.

Introduction

Several lines of evidence indicate that cerebrovascular disease burden increases the risk of cognitive impairment in older individuals alone or in combination with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology.1–4 Neuropathological studies have demonstrated that cerebrovascular disease and AD pathology frequently co-occur in older adults.5–7 The presence of cerebrovascular disease pathology at autopsy appears to lower the threshold at which a given burden of AD pathology leads to cognitive impairment and dementia,8,9 highlighting the critical importance of vascular pathologies to the emergence of clinically evident symptoms. Consistent with this, we recently demonstrated that higher levels of vascular risk and elevated β-amyloid (Aβ) burden synergistically accelerate cognitive decline in clinically normal older individuals.10 While vascular contributions to the clinical syndrome of AD have been increasingly recognized,11 it remains unclear whether vascular burden influences the accumulation of AD pathology in vivo.

Multiple studies suggest that vascular risk factors assessed during midlife are associated with increased in vivo Aβ burden later in life.12–14 However, the evidence is mixed as to whether a relationship exists between vascular risk factors and Aβ burden measured concurrently in older adults,10,12,15 with recent data from our group suggesting no relationship.10 In terms of tau burden, several studies have demonstrated a possible association between vascular risk factors and both cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and positron emission tomography (PET) markers of tau deposition.14,16,17 Additionally, a recent autopsy study identified an association between late-life systolic blood pressure and overall tau pathology burden.18

Motivated by these prior studies, in the present study we examined associations between vascular risk factors, Aβ burden, and regional tau burden in clinically normal older adults participating in the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS). Specifically, we combined the recently developed tau PET tracer 18F-Flortaucipir, 11C-Pittsburgh Compound-B (PiB) PET, and a well-validated measure of systemic vascular risk to investigate whether increased vascular risk and elevated Aβ burden are synergistically associated with higher regional tau burden in vivo. We primarily focused on tau burden in two regions of interest (ROIs): the entorhinal cortex (EC), because it is among the first regions to develop tau pathology with increasing age,19,20 and the inferior temporal cortex (ITC), as it is an early neocortical site of tau deposition associated with AD.19,21,22

Methods

Participants

One hundred and fifty-two clinically normal participants from the Harvard Aging Brain study (HABS) were included in this study (see Table 1 for demographic information). Participants provided written informed consent prior to study procedures. Study protocols were approved by the Partners HealthCare Institutional Review Board. At study entry, all participants had a global Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR)23 = 0, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)24 ≥ 27 with educational adjustment, and performed within education-adjusted norms on Logical Memory delayed recall.25 All participants underwent a comprehensive medical and neurological evaluation and none of the participants had serious medical, psychiatric, or neurological conditions, recent history of alcoholism, or drug abuse. Exclusionary criteria included a Modified Hachinski Ischemic Score > 4, history of stroke with residual deficits, and extensive small vessel ischemic disease. In the present study participants were required to have both Aβ and tau PET imaging data, as well as the necessary demographic and medical information to calculate an aggregate measure of vascular risk.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | All Participants (n = 152) |

|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 73.5 (6.1) |

| Education in years, mean (SD) | 16.2 (2.9) |

| Females, n (%) | 90 (59) |

| Aβ PET FLR DVR (PVC), | 1.35 (0.4) |

| EC tau PET SUVR (PVC), mean (SD) | 1.36 (0.3) |

| ITC tau PET SUVR (PVC), mean (SD) | 1.47 (0.2) |

| APOE ε4 carriers, n (%) | 47 (31) |

| FHS-CVD, mean (SD) | 31.6 (17.2) |

| Antihypertensive medication, n (%) | 79 (52) |

| SBP, mean (SD), mmHG | 140.0 (17.8) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.7 (4.6) |

| History of diabetes, n (%) | 13 (9) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 6 (4) |

| Time interval in years between baseline and the tau PET scan, mean (SD) | 2.98 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: Aβ, β-amyloid; APOE ε4, Apolipoprotein E ε4 allele; BMI, body mass index; DVR, distribution volume ratio; EC, entorhinal cortex; FHS-CVD, Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score; FLR, frontal, lateral, and retrosplenial tracer; ITC, inferior temporal cortex; PET, positron emission tomography; PVC, partial volume corrected; SUVR, standardized uptake value ratio; SBP, systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Vascular risk was quantified using the office-based Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score (FHS-CVD)26 at Year 1 of HABS (baseline). The FHS-CVD represents a weighted sum of age, sex, antihypertensive treatment (yes or no), systolic blood pressure (mm Hg), body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), history of diabetes (yes or no), and current cigarette smoking status (yes or no). The FHS-CVD provides a 10-year probability of future cardiovascular events (defined as coronary death, myocardial infarction, coronary insufficiency, angina, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, transient ischemic attack, peripheral artery disease, and heart failure). In our sample, the FHS-CVD ranged from 4% to 74% (median = 29%), with higher scores indicating greater risk of future cardiovascular events.

Brain Imaging

Aβ burden was measured using 11C-Pittsburgh Compound-B PET and tau burden was measured using 18F-Flortaucipir (previously known as AV-1451 or T807). PET imaging was carried out at the Massachusetts General Hospital PET facility (Siemens ECAT EXACT HR+ scanner). Aβ PET data used in the present study were obtained during Year 1 of HABS (baseline). Tau PET was introduced into HABS mid-study, with the majority of participants undergoing tau PET at Year 4 of the study (2.98±1.1 years after study entry). Detailed Aβ and tau PET protocols have been previously described.21 As in prior studies from our group, Aβ PET measurements were represented as a distribution volume ratio (DVR) across a composite of frontal, lateral temporal and parietal, and retrosplenial regions (given the high degree of collinearity among neocortical regions).21,27 Tau PET measures were computed as standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) within FreeSurfer-defined (version 5.3) ROIs. As mentioned above, we focused our analyses on two pre-defined ROIs: the EC and the ITC. Because we had no a priori hypotheses regarding laterality, regions were averaged across left and right hemispheres to reduce the number of comparisons. Due to off-target binding of Flortaucipir in the portions of the choroid plexus adjacent to the hippocampus, we did not examine tau burden in this region.21,28 Cerebellar grey matter (as defined by FreeSurfer) served as the reference region for Aβ and tau PET data. PET data were corrected for partial volume effects using the geometric transfer matrix method.29 Of note, analyses using non-partial volume corrected PET data yielded nearly identical results (not reported).

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using R, version 3.2.4. All continuous variables were z-transformed prior to model entry. We used partial Pearson correlations to examine the relationships between FHS-CVD, Aβ burden, and tau burden in the EC and ITC, adjusting for age and sex. Of primary interest in the present study was whether baseline FHS-CVD and Aβ burden interact to predict subsequent tau in the EC or ITC. We used linear regression models to examine this question, controlling for age, sex, Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 status (carrier/non-carrier) and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan (to account for differences across participants related to when tau PET was acquired).

We next conducted an exploratory whole-brain regional analysis to examine whether the interaction of baseline FHS-CVD and Aβ burden on subsequent tau deposition extended to regions beyond the two pre-specified ROIs examined in the primary analyses (EC and ITC). As above, this analysis averaged across left and right hemispheres, and we adjusted for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan. Family-wise error (FWE) correction was used to maintain an α of ≤ 0.05 in the setting of multiple ROI comparisons (corresponds to an uncorrected p-value of ≤ 0.0036).

Results

Baseline demographic information is presented in Table 1. After adjusting for age and sex, there was no relationship between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden (rpartial = −0.04, p = 0.59). We observed a significant, but weak, relationship between FHS-CVD and tau burden in the ITC (rpartial = 0.19, p = 0.02). The relationship between FHS-CVD and tau burden in the EC was not statistically significant (rpartial = 0.12, p = 0.15). Consistent with previous findings,17,30,31 we found a significant relationship between Aβ and tau burden in both the EC (rpartial = 0.50, p < 0.001) and ITC (rpartial = 0.46, p < 0.001). APOE ε4 status was not related to FHS-CVD (β = −0.05, SE = 0.12, p = 0.70), after adjusting for age and sex.

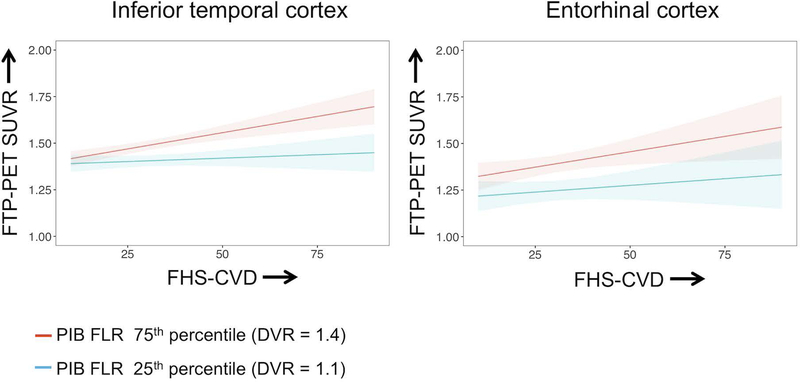

The primary goal of the study was to investigate whether baseline FHS-CVD and Aβ burden have an interactive association with subsequent tau burden in two pre-defined ROIs (EC and ITC). We found a significant interaction between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden in relation to tau burden in the ITC, whereby the combination of higher FHS-CVD and higher Aβ burden was associated with elevated tau deposition in this region. We did not find a significant interaction between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden in predicting tau burden in the EC (Fig 1, Table 2).

Figure 1. Plots demonstrating the interaction between the Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score (FHS-CVD) and Aβ burden in relation to tau burden.

Plots illustrate the predicted trajectories from the full regression model adjusted for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan. For visualization purposes, low and high levels of Aβ burden are represented based on distribution volume ratio (DVR) values at the 25th percentile and 75th percentiles, respectively. PET data were partial volume corrected. The interaction was significant for tau in the inferior temporal cortex (left panel), such that combined higher FHS-CVD and elevated Aβ burden was associated with higher tau burden in this region. The effect was not significant for tau in the entorhinal cortex (right panel). Shaded regions represent the 95% confidence interval for the regression line.

Table 2.

Summary of linear regression models examining the interactive effect of the FHS-CVD and Aβ burden on tau deposition

| β estimate | Standard error | T value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC tau ~ Aβ*FHS-CVD + Aβ + FHS-CVD + age + sex + APOE ε4 + time interval | ||||

| Aβ*FHS-CVD | 0.11 | 0.08 | 1.40 | 0.16 |

| Aβ | 0.50 | 0.08 | 6.22 | < 0.001 |

| FHS-CVD | 0.20 | 0.10 | 1.92 | 0.06 |

| Age | 0.15 | 0.08 | 1.76 | 0.08 |

| Sex (male) | −0.39 | 0.18 | −2.11 | 0.04 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | −0.07 | 0.17 | −0.43 | 0.67 |

| Time interval | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.87 |

| R2 of model = 0.35 | ||||

| ITC tau ~ Aβ*FHS-CVD + Aβ + FHS-CVD + age + sex + APOE ε4 + time interval | ||||

| Aβ*FHS-CVD | 0.28 | 0.07 | 3.77 | < 0.001 |

| Aβ | 0.53 | 0.08 | 7.00 | < 0.001 |

| FHS-CVD | 0.31 | 0.09 | 3.24 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.13 | 0.08 | 1.70 | 0.09 |

| Sex (male) | −0.31 | 0.17 | −1.85 | 0.07 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.84 |

| Time interval | 0.18 | 0.06 | 2.84 | 0.005 |

| R2 of model = 0.42 | ||||

Linear regression models with FHS-CVD and Aβ burden as interactive predictors of tau deposition, repeated for each tau region (EC and ITC). All continuous variables were z-transformed prior to model entry. T values represent the β estimate divided by the standard error. Abbreviations. APOE ε4 = Apolipoprotein E ε4; BMI = body mass index; EC = entorhinal cortex; FHS-CVD = Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score; HTN meds = Treatment with antihypertensive medication; ITC = inferior temporal cortex. Time interval refers to the time lag between baseline and the tau PET scan.

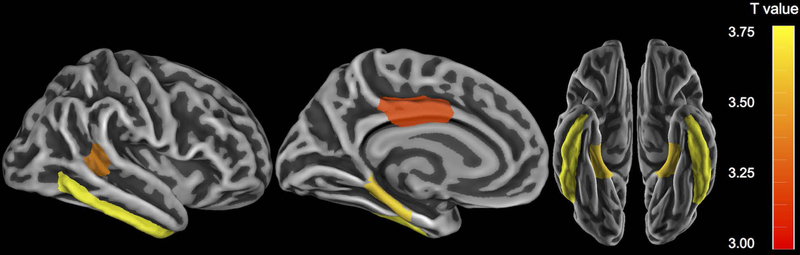

To explore whether the interaction of FHS-CVD and Aβ burden was limited to the ITC, we next performed an exploratory analysis across a wider set of FreeSurfer-defined cortical ROIs, averaged across hemispheres. After adjusting for covariates and employing FWE correction for multiple comparisons, we observed that higher FHS-CVD and higher Aβ burden were interactively associated with elevated tau deposition in medial temporal (parahippocampus), lateral temporal (ITC and banks of the superior temporal sulcus), and posterior cingulate regions (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Exploratory regional analyses depicting the interaction between the Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score (FHS-CVD) and Aβ burden on tau burden.

FreeSurfer-defined regions in which the interaction of FHS-CVD and Aβ correlated significantly with regional tau deposition. Regions were averaged across left and right hemispheres. In all regions shown, combined higher FHS-CVD and elevated Aβ was associated higher tau burden. Color bars indicate the t-statistic for the association, adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan. Regions shown are p < 0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons (FWE).

Lastly, we investigated whether specific components of the FHS-CVD were driving the aforementioned interaction with Aβ burden in relation to subsequent tau deposition in the ITC. To address this question, we decomposed the FHS-CVD into its constituent measures and interacted each vascular component with Aβ to predict subsequent ITC tau. As summarized in Table 3, we observed a significant interaction between all components of the FHS-CVD and Aβ burden in relation to ITC tau, with the exception of a history of diabetes. However, it should be noted that the number of study participants with a history of diabetes was relatively small (n=13, 9% of the sample, Table 1).

Table 3.

Summary of linear regression models examining the interactive effect of the FHS-CVD components and Aβ burden on tau deposition in the inferior temporal cortex

| β estimate | Standard error | T value | P value | R2 of the model | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITC tau ~ Aβ*FHS-CVD Component + Aβ + FHS-CVD component + age + sex + APOE ε4 + time interval | |||||

| Aβ*BMI | 0.25 | 0.07 | 3.29 | 0.001 | 0.38 |

| Aβ*SBP (mm Hg) | 0.22 | 0.07 | 2.93 | 0.004 | 0.38 |

| Aβ*HTN med | 0.44 | 0.13 | 3.49 | < 0.001 | 0.42 |

| Aβ*Smoking status | 0.81 | 0.31 | 2.60 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| Aβ*Diabetes | 0.51 | 0.38 | 1.34 | 0.18 | 0.33 |

Linear regression models with FHS-CVD and Aβ burden as interactive predictors of tau deposition in the inferior temporal cortex, repeated for each vascular component of the FHS-CVD. Each row summarizes the results from a separate linear regression model. All continuous variables were z-transformed prior to model entry. T values represent the β estimate divided by the standard error. Abbreviations. BMI = body mass index; FHS-CVD = Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease risk score; HTN med = Treatment with antihypertensive medication; ITC = inferior temporal cortex; SBP = systolic blood pressure.

Discussion

In this study of clinically normal older adults, we observed that higher vascular risk in the setting of elevated Aβ burden was associated with increased tau deposition in temporal neocortical regions known to be early sites of AD-related tau deposition.19,21 Importantly, these findings remained after adjusting for age, sex, APOE ε4 status, and the time interval between baseline and the tau PET scan. Although additional studies are necessary to confirm our findings, the present results suggest that vascular risk factors may influence the progression of tau pathology in individuals with elevated Aβ burden.

A growing body of research supports the hypothesis that Aβ is necessary, but not sufficient, to predict imminent cognitive decline along the AD trajectory.32–34 The present findings raise the possibility that elevated vascular risk may represent a “second hit” that further potentiates the spread of Aβ-related neocortical tau pathology. Given the close linkage of tau pathology to cognitive decline,35,36 the synergistic interaction between vascular risk and Aβ burden may be one route by which clinical symptoms associated with AD are manifested.9,10,37–39

We did not observe a significant interaction between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden in relation to tau in the EC. One possible explanation for this observation is that the EC ROI is relatively small and may be susceptible to partial volume effects due to its shape and close proximity to CSF. Accordingly, measurements of tau PET in the EC may be noisier than the ITC even when partial volume correction is employed (as in the present analyses). Consistent with this possibility, an exploratory analysis suggested an interaction between FHS-CVD and Aβ burden on tau deposition in larger, neighboring medial temporal regions, namely bilateral parahippocampal cortices (another site of early tau deposition).19,20,40,41 Although these exploratory findings should be interpreted cautiously and require replication in larger samples, the pattern of results suggests that the interaction of FHS-CVD and Aβ may influence tau deposition in medial temporal, lateral temporal, and medial parietal regions.

The underlying mechanism by which vascular risk and Aβ pathology interact to promote elevated neocortical tau deposition remains unclear. Several studies suggest that cerebrovascular disease contributes to AD pathogenesis via altering Aβ production and/or clearance,42,43 with several recent studies demonstrating an association between midlife vascular risk factors and later-life Aβ burden.12–14 However, we did not find evidence of a relationship between vascular risk and concurrent measures of Aβ burden in our sample. It is possible that the effects of vascular risk on tau burden may be mediated by toxic Aβ species not readily detected with PET imaging (e.g., oligomeric Aβ species).44,45 Another possible explanation is that vascular disease may render neurons more vulnerable to the toxic effects of Aβ, in turn promoting neocortical tau deposition in injured neurons and subsequent trans-synaptic spread of pathologic tau species.

While we were most interested in the FHS-CVD as an aggregate measure of vascular risk, we did examine whether specific components of the FHS-CVD were driving the interaction with Aβ burden in relation to ITC tau. In these analyses, all components of the FHS-CVD interacted with Aβ burden to significantly predict increased ITC tau deposition, with the exception of a history of diabetes. It should be noted, however, that only a small number of study participants reported a history of diabetes (n = 13; 9%) and therefore this latter finding should be interpreted with caution. Overall, the consistently observed synergistic interactions between individual vascular risk factors and Aβ burden on tau deposition supports the robustness of our finding using a multi-variable vascular risk measure, and highlights the utility of aggregate measures of vascular risk when investigating relationships between vascular health and tau pathology in preclinical AD.

As with other studies of this type, consideration of the study sample composition is highly relevant to the interpretation and generalizability of the results. HABS participants are generally well educated and predominately Caucasian, sample characteristics which may impact the generalizability of these findings. HABS excludes participants with evidence of extensive small vessel disease, stroke, uncontrolled diabetes, and unstable hypertension, and therefore our study sample may not be representative of individuals with very high levels of systemic vascular risk. In addition, individuals with both high vascular risk and high Aβ burden are likely under-represented in the study sample, as they are more likely to be cognitively impaired and therefore excluded from study participation. While these exclusionary criteria do not allow us to study the full spectrum of vascular risk, our results suggest that even relatively modest levels of vascular risk can interact with Aβ burden to increase neocortical tau pathology in clinically normal older adults.

Several additional limitations should be noted. Our findings are based on cross-sectional data; longitudinal studies with serial PET imaging will be critical to understand the temporal relationships between vascular risk, Aβ burden, and tau accumulation. In addition, future work in this and other cohorts should examine the extent to which potentiated tau accumulation mediates the impact of elevated vascular risk on cognitive decline in individuals with elevated Aβ.46 Finally, we interpret the interaction of FHS-CVD with Aβ burden to represent that higher vascular risk in the context of elevated Aβ burden gives rise to higher tau burden, however alternate interpretations of these findings remain quite possible. That is, this same interaction can also be interpreted as higher Aβ burden in the setting of elevated vascular risk leads to greater tau deposition. As such, the results here do not address whether elevated Aβ burden precedes elevated vascular risk or vice versa. This caveat is particularly important in the present study, as individuals with the highest levels of vascular risk may not be well represented in the study sample.

In conclusion, our results suggest that elevated vascular risk may influence neocortical tau deposition when coupled with high Aβ burden. Given that tau PET will likely become increasingly integral to AD clinical trials, these findings indicate the importance of accounting for vascular risk when assessing tau accumulation in clinical research settings. Perhaps most importantly, these findings support the rationale behind interventional studies designed to decrease systemic vascular risk (alone or in combination with Aβ-lowering approaches) as a means of attenuating the progression of Aβ-related neocortical tau pathology.47–49

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (P01 AG036694 to R.A.S. and K.A.J., K24 AG035007 to R.A.S., K23 AG049087 to JPC, R01 AG053509 and R01 AG054110 to T.H, and P50 AG005134 to RAS, KAJ, AV, TH and R01AG047975, R01AG026484, K23 AG02872605 to AV, K23 AG058805–01 to JGR), JSR is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Postdoctoral Fellowship Award, HSY is supported by the Alzheimer’s Association Clinical Fellowship (AACF-17–505359); JRG is also supported by the Alzheimer’s Association and the BrightFocus Foundation. RFB is supported by the NHMRC Dementia Research Fellowship (APP1105576).

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Drs. Sperling and Johnson are involved in public-private partnership clinical trials sponsored by Eli Lilly and Co. who owns the distribution rights to Flortaucipir (AV-1451), but they do not have any personal financial relationship with Eli Lilly.

References

- 1.Azarpazhooh MR, Avan A, Cipriano LE, Munoz DG, Sposato LA, Hachinski V. Concomitant vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies double the risk of dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement 2018;14(2):148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42(9):2672–2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villeneuve S, Jagust WJ. Imaging vascular disease and amyloid in the aging brain: implications for treatment. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2015;2(1):64–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohman TJ, Samuels LR, Liu D, et al. Stroke risk interacts with Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers on brain aging outcomes. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36(9):2501–2508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korczyn A Mixed dementia - the most common cause of dementia. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002;977(1):129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapasi A, Decarli C, Schneider JA. Impact of multiple pathologies on the threshold for clinically overt dementia. Acta Neuropathol 2017;134(2):171–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community- dwelling older persons. Neurology 2007;69(24):2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Arvanitakis Z, Bienias JL, Bennett DA. Subcortical infarcts, Alzheimer’s disease pathology, and memory function in older persons. Ann Neurol 2007;62(1):59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snowdon DA, Greiner LH, Mortimer JA, Riley KP, Greiner PA, Markesbery WR. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease: the nun study. JAMA 1997;277(10):813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabin JS, Schultz AP, Hedden T, et al. Interactive associations of vascular risk and β-amyloid burden with cognitive decline in clinically normal elderly individuals: findings from the Harvard Aging Brain Study. JAMA Neurol 2018;75(9):1124–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Snyder HM, Corriveau RA, Craft S, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia including Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement 2015;11(6):710–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gottesman RF, Schneider ALC, Zhou Y, et al. Association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA 2017;317(14):1443–1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vemuri P, Knopman DS, Lesnick TG, et al. Evaluation of amyloid protective factors and Alzheimer disease neurodegeneration protective factors in elderly individuals. JAMA Neurol 2017;74(6):718–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nägga K, Gustavsson A-M, Stomrud E, et al. Increased midlife triglycerides predict brain β-amyloid and tau pathology 20 years later. Neurology 2018;90(1):e73–e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodrigue KM, Rieck JR, Kennedy KM, Devous MD Sr., Diaz-Arrastia R, Park DC Risk factors for beta-amyloid deposition in healthy aging: vascular and genetic effects. JAMA Neurol 2013;70(5):600–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nation DA, Edland SD, Bondi MW, et al. Pulse pressure is associated with Alzheimer biomarkers in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology 2013;81(23):2024–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vemuri P, Lesnick TG, Przybelski SA, et al. Age, vascular health, and Alzheimer disease biomarkers in an elderly sample. Ann Neurol 2017;82(5):706–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arvanitakis Z, Capuano AW, Lamar M, et al. Late-life blood pressure association with cerebrovascular and Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology 2018;91(16):e517–e552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 2006;112(4):389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho H, Choi JY, Hwang MS, et al. In vivo cortical spreading pattern of tau and amyloid in the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Ann Neurol 2016;80(2):247–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson KA, Schultz A, Betensky RA, et al. Tau positron emission tomographic imaging in aging and early Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2016;79(1):110–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 1999;45(3):358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993;43(11):2412–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12(3):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wechsler D WMS-R: Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2008;117(6):743–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabin JS, Perea R, Buckley R, et al. Global white matter diffusion characteristics predict longitudinal cognitive change independently of amyloid status in clinically normal older adults. Cereb Cortex 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marquié M, Normandin MD, Vanderburg CR, et al. Validating novel tau positron emission tomography tracer [F-18]-AV-1451 (T807) on postmortem brain tissue. Ann Neurol 2015;78(5):787–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rousset OG, Ma Y, Evans AC. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: principle and validation. J Nucl Med 1998;39(5):904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lockhart SN, Schöll M, Baker SL, et al. Amyloid and tau PET demonstrate region-specific associations in normal older people. Neuroimage 2017;150:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schwarz AJ, Yu P, Miller BB, et al. Regional profiles of the candidate tau PET ligand 18F-AV-1451 recapitulate key features of Braak histopathological stages. Brain 2016;139(5):1539–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7(3):280–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mormino EC, Betensky RA, Hedden T, et al. Synergistic effect of β-amyloid and neurodegeneration on cognitive decline in clinically normal individuals. JAMA Neurol 2014;71(11):1379–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burnham SC, Bourgeat P, Doré V, et al. Clinical and cognitive trajectories in cognitively healthy elderly individuals with suspected non-Alzheimer’s disease pathophysiology (SNAP) or Alzheimer’s disease pathology: a longitudinal study. Lancet Neurol 2016;15(10):1044–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Arnold SE. Neurofibrillary tangles mediate the association of amyloid load with clinical Alzheimer disease and level of cognitive function. Arch Neurol 2004;61(3):378–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, et al. Correlation of Alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2012;71(5):362–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Esiri MM, Nagy Z, Smith MZ, Barnetson L, Smith AD. Cerebrovascular disease and threshold for dementia in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 1999;354(9182):919–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zekry D, Duyckaerts C, Moulias R, et al. Degenerative and vascular lesions of the brain have synergistic effects in dementia of the elderly. Acta Neuropathol 2002;103(5):481–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schneider JA, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Cerebral infarctions and the likelihood of dementia from Alzheimer disease pathology. Neurology 2004;62(7):1148–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitchell TW, Mufson EJ, Schneider JA, et al. Parahippocampal tau pathology in healthy aging, mild cognitive impairment, and early Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol 2002;51(2):182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damasio AR, Hoesen GW Van. The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Cereb Cortex 1991;1(1):103–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gupta A, Iadecola C. Impaired Aß clearance: a potential link between atherosclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci 2015;7:115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zlokovic BV Neurovascular mechanisms of Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration. Trends Neurosci 2005;28(4):202–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer’s amyloid β-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8(2):101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV., et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature 2002;416(6880):535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim HJ, Park S, Cho H, et al. Assessment of extent and role of tau in subcortical vascular cognitive impairment using 18F-AV1451 positron emission tomography imaging. JAMA Neurol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected effect of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer’s disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol 2011;10(9):819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Norton S, Matthews FE, Barnes DE, Yaffe K, Brayne C. Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer’s disease: an analysis of population-based data. Lancet Neurol 2014;13(8):788–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Bruijn RFAG, Bos MJ, Portegies MLP, et al. The potential for prevention of dementia across two decades: the prospective, population-based Rotterdam Study. BMC Med 2015;13(1):132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]