Abstract

Purpose:

To examine the association between exposures to violence in childhood, including exposure to multiple forms of violence, with young men’s perpetration of intimate partner violence (IPV) in Malawi.

Methods:

We analyzed data from 450 ever-partnered 18- to 24-year-old men interviewed in the Malawi Violence Against Children and Young Woman Survey, a nationally representative, multistage cluster survey conducted in 2013. We estimated the weighted prevalence for perpetration of physical and/or sexual IPV and retrospective reporting of experiences of violence in childhood and examined the associations between childhood experiences of violence and perpetration of IPV using logistic regression.

Results:

Among young men in Malawi, lifetime prevalence for perpetration of sexual IPV (24%) was higher than for perpetration of physical IPV (9%). In logistic regression analyses, the adjusted odds ratios for perpetration of sexual IPV increased in a statistically significant gradient fashion, from 1.2 to 1.4 to 3.7 to 4.3 for young men with exposures to one, two, three, and four or more forms of violence in childhood, respectively.

Conclusions:

Among young men in Malawi, exposure to violence in childhood is associated with an increased odds of perpetrating IPV, highlighting the need for programs and policies aimed at interrupting the intergenerational transmission of violence.

Keywords: Violence against children, Intimate partner violence, Domestic violence, Perpetration, Malawi, Violence Against Children Survey

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against an intimate partner (e.g., spouse, cohabitating partner, date), that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation. This definition encompasses physical, sexual, and emotional or psychological abuse [1,2]. Worldwide, 30% of ever-partnered women have experienced physical or sexual violence, or both, perpetrated by an intimate partner [3]. While both men and women may perpetrate IPV [4], globally the greatest burden and consequences of IPV are experienced by women [3]. In Malawi, the focus of this research, 40% of ever-married women report having experienced physical and/or sexual IPV in their lifetimes [5]. IPV can have short- and long-term physical and mental health effects on women and their children, including, but not limited to, low birth weight and preterm birth [6,7], depression [8,9], and increased risk for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV [8,10–12]. In general, research in lower income countries has focused primarily on women’s exposure to IPV, not men’s perpetration [13]. Similarly, the relationship between men’s exposure to violence in childhood, including experiencing and/or witnessing violence, and their perpetration of IPV against women is understudied in these contexts.

Violence against children is a significant problem worldwide, one that has devastating consequences for children’s life-long health and well-being [14]. Children may be exposed to physical, emotional, or sexual abuse perpetrated by their parents or adult caregivers, adults in the community, or peers. Children may also witness violence between adults or peers in their communities. Worldwide, an estimated 37% of children experience emotional abuse, 23% of children experience physical abuse, and 18% of girls and 8% of boys experience sexual abuse [15]. In a nationally representative survey, 56.1% of females and 67.9% of males aged 13–17 in Malawi reported experiencing some form of emotional, physical, and/or sexual abuse in the past 12 months [16]. Authors of a population-based study of six countries in Asia and the Pacific reported that men’s childhood experiences of violence, including experiencing emotional, physical, or sexual violence, or witnessing abuse of his mother were significantly associated with physical, sexual, emotional, and/or economic IPV perpetration in at least one or more countries [17]. In another multicountry study, which included data from two African countries, witnessing parental violence was a risk factor for men’s perpetration of physical IPV [18]. Additionally, research studies from Sub-Saharan Africa demonstrate associations between both experiencing violence in childhood [19,20] and witnessing parental IPV [21] with men’s perpetration of IPV. No population-based studies, to our knowledge, have explored the relationship between childhood exposures to violence and men’s perpetration of IPV against women in Malawi.

There is a growing body of literature describing the negative impact of adverse childhood experiences on a range of health outcomes in adulthood, including chronic disease [22], infectious diseases including HIV [23], reproductive health [24], mental health [25], suicide attempts [22], and substance abuse [22]. Additionally, evidence suggests a dose-response relationship. As the number of categories of adverse childhood experiences increases, so does the risk for a range of poor health outcomes [22]. There is evidence from the United States and England to suggest this graded relationship exists between exposures to multiple adverse childhood experiences, including experiences of violence, and perpetration of violence, including IPV [26,27]. Researchers have theorized that multiple exposures to early-life stressors, including experiences of violence and witnessing violence, may lead to changes in the structure and physiology of the brain that may play a role in sexual and aggressive behavior, including the perpetration of IPV [28]. To our knowledge, this graded relationship has not been explored in population-based studies in Africa. Thus, the objectives of this study were to estimate the prevalence of young men’s perpetration of physical and sexual IPV in Malawi and to examine the association between exposures to violence in childhood, including exposure to multiple forms of violence, with young men’s perpetration of IPV.

Material and methods

The Malawi Violence Against Children and Young Women Survey (VACS Malawi) is a collaboration between the Malawi Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare, United Nation’s Children’s Fund, The Center for Social Research of the University of Malawi, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. VACS Malawi is a nationally representative, cross-sectional household survey designed to produce national-level estimates [16]. The survey, which used a four-stage cluster sample survey design, was conducted September–October, 2013. The survey followed a split sample approach; the survey for females was conducted in different enumeration areas than for the males. This approach served to protect the confidentiality of respondents and reduce the chance that a male perpetrator of a sexual assault and the female who was the victim of that assault (or vice versa) would both be interviewed. Males and females aged 13e24 years old living in selected households were eligible for participation in the study. For those aged 18 years and older, lifetime prevalence estimates of childhood violence were based on their reported experiences before age 18. A total of 2162 individuals aged 13–24 years old participated in the Malawi VACS; 1029 females and 1133 males completed the individual questionnaire, yielding a combined household and individual response rate of 84.4% for females and 83.4% for males. The current analysis focuses on the responses from 450 ever-partnered 18- to 24-year-old men whose responses were weighted to represent all ever-partnered 18- to 24-year-old men in Malawi.

Ethical protections were prioritized in the planning, design, and implementation of the study. The study adhered to World Health Organization guidelines on ethics and safety for research on violence against women and received Institutional Review Board approval from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Review Board and the Malawian National Commission for Science and Technology Ethical Review Board [16]. To help facilitate trust with respondents, care was taken to select interviewers who spoke the local languages, had experience with confidential data and health issues, and looked physically young. Training for the interviewers was specific to violence research. For respondents under 18 years of age, the team first obtained the permission of the primary caregiver to speak with the eligible respondents. At this stage, the survey was described as an opportunity to learn about “young people’s health, educational, and life experiences” and “community violence” was included in a list of broad topics included in the interview, and no specific mention was made of violence occurring in the home. These steps were taken to inform parents and care-givers about the content of the study without risking possible negative consequences against children for their participation. Once a respondent was selected, a gender-matched trained interviewer initially introduced the survey, and verbal assent or consent to provide more information about the study was obtained from respondents. Once the interviewer and respondent ensured privacy, the trained interviewer read the contents of a verbal assent or consent form, which informed the respondents about the voluntary nature of the study, specific topics covered in the survey, and reinforced that the information they shared was confidential.

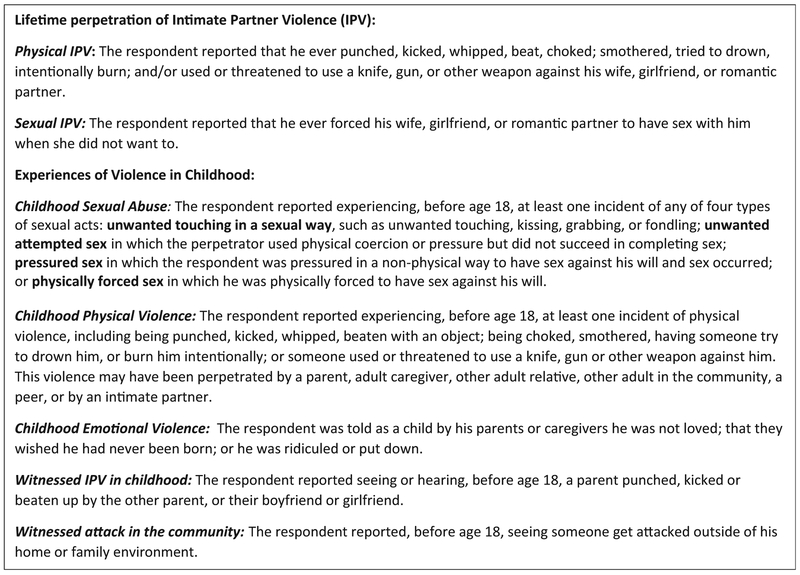

Items from the Malawi VACS measuring violence perpetration and exposures to violence are described in Figure 1. These items, which have been used to measure violence against children in similar settings [29,30], were selected and adapted from a range of well-respected survey tools, and were pilot tested to ensure appropriateness for the Malawian context [16]. The outcome variables for this analysis were lifetime perpetration (yes/no) of physical or sexual IPV against a current or previous girlfriend, romantic partner, or wife. Exposure to violence in childhood was considered based on whether the respondent reported, before age 18 years, witnessing IPV, witnessing an attack in the community, or experiencing sexual abuse, physical violence, or emotional violence. Consistent with literature on adverse childhood experiences in developing country settings [31], we created a summative scale for cumulative exposures to violence, ranging from no exposures to violence, to exposure to four or more forms of violence during childhood. Demographic controls included age in years, if the respondent ever married, if he completed or attended secondary school or higher, and whether he ever begged in the street [19,31]. Potential confounders captured other adverse childhood experiences such as whether the respondent was orphaned (one or both parents died) before age 18 years, and the presence of social support from friends and family (e.g., if he felt very close to his biological mother and father, or if he reported talking with friends often about important things) [19].

Fig. 1.

Measures of young men’s intimate partner violence perpetration and experiences of violence in childhood.

We first estimated the weighted prevalence for perpetration of physical and/or sexual IPV and experiences of violence in childhood among young adult men. We then examined the associations between childhood experiences of violence and perpetration of IPV using logistic regression. We found very little overlap between young men’s reported perpetration of different types of IPV, with only 3% of young men reporting perpetration of both physical and sexual IPV. For this reason, we analyzed physical and sexual IPV perpetration as separate outcomes in logistic regression models. We explored whether potential confounders influenced the association between exposure to violence in childhood and perpetration of IPV and included variables significantly associated with both the exposure and the outcome in the adjusted models. In preliminary analyses exploring the bivariate relationships between exposure to multiple forms of violence in childhood and men’s perpetration of physical IPV, we found high estimated standard errors for the estimates, suggesting they may be unstable. Therefore, we present here the adjusted measures for exposures to multiple forms of violence in childhood and men’s perpetration of sexual IPV. Analyses were run in SAS 9.3 [32], and all analyses accounted for the complex survey design.

Results

On average, the ever-partnered 18- to 24-year-old men in our sample were 20 years old, a third were married, 42% had completed or attended secondary school or higher, and 7% percent reported begging for alms in the street at some point in their life (Table 1). Forty-eight percent of young men talked with their friends about important things, 81% felt very close to their biological mother, 62% felt very close to their biological father, and 28% were orphaned before age 18 years. Young men in Malawi reported high levels of both experiencing and witnessing violence in childhood. Lifetime prevalence for experiencing violence in childhood ranged from 15% for sexual abuse to 28% for emotional violence and 65% for physical violence. As a child, 39% of young men witnessed an attack in their community and 32% witnessed IPV (Table 1). Only 18% of young men reported no exposure to violence in childhood, while the majority of young men experienced multiple forms of violence in childhood, with 10% exposed to four or more different forms of violence (Table 1). More than a quarter of young men (29%) reported perpetrating physical and/or sexual IPV in their lifetime. Lifetime prevalence for perpetration of sexual IPV (24%) was higher than for perpetration of physical IPV (9%) and very few men (3%) reported perpetrating both physical and sexual IPV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Childhood exposures to violence, lifetime perpetration of IPV, and characteristics of ever-partnered* males (N = 450) ages 18–24, Malawi

| Weighted % (n) | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|

| Childhood exposures to different forms of violence | ||

| None | 17.8 (76/450) | 13.4%−22.2% |

| One | 27.2 (121/450) | 20.4%−34.1% |

| Two | 26.3 (120/450) | 19.8%−32.7% |

| Three | 18.6 (78/450) | 14.2%−23.1% |

| Four or more | 10.1 (55/450) | 6.4%−13.9% |

| Childhood experiences | ||

| Any childhood sexual abuse (before age 18) | 15.1 (66/450) | 10.2%−20.1% |

| Any childhood physical violence (before age 18) | 64.6 (305/450) | 58.3%−70.9% |

| Any childhood emotional violence (before age 18) | 28.4 (134/446) | 22.9%−33.9% |

| Ever-witnessed IPV in childhood (before age 18) | 31.8 (149/447) | 25.2%−38.4% |

| Witnessed attack in the community (before age 18) | 39.2 (175/449) | 32.6%−45.7% |

| Ever perpetration of IPV | ||

| Any physical and/or sexual IPV perpetration | 29.1 (142/450) | 23.6%−34.6% |

| Any sexual IPV perpetration | 23.9 (114/447) | 18.3%−29.6% |

| Any physical IPV perpetration | 8.5 (45/450) | 5.6%−11.3% |

| Both physical and sexual IPV perpetration | 3.2 (17/450) | 1.4%−5.0% |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Age in years (mean) | 20.4 | 20.2–20.7 |

| Ever married | 33.8 (180/450) | 27.5%−40.0% |

| Completed or attended secondary school or higher | 41.7 (201/450) | 33.1%−50.4% |

| Ever begged in the street | 7.2 (38/450) | 3.9%−10.6% |

| Social characteristics | ||

| Talks with friends | 48.4 (212/450) | 40.6%−56.1% |

| Close with mother† | 81.4 (358/450) | 75.8%−87.0% |

| Close with father† | 62.3 (283/450) | 57.1%−67.5% |

| Orphaned before age IS (one or both parents died) | 28.0 (136/442) | 22.7%−33.4% |

Ever-partnered defined as those reporting having ever had a girlfriend, ever lived with a partner, or having ever been married.

Don’t know/declined coded as “0.”

Perpetration of physical IPV

Prevalence of lifetime perpetration of physical IPV among young men experiencing each of the five different forms of violence in childhood ranged from 9% to 12% (Table 2). We found a positive association between experiencing physical violence in childhood and men’s perpetration of physical IPV (odds ratio 3.0, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–8.4, P = .04) but did not find a statistically significant association for exposure to other forms of violence in childhood and young men’s perpetration of physical IPV. We did not identify any data-based confounders for the association between experiencing physical violence in childhood and men’s perpetration of physical IPV. Thus, adjusted estimates were not calculated.

Table 2.

Childhood exposures to violence and lifetime perpetration of physical IPV among ever-partnered males (N = 450) ages 18–24, Malawi

| Any lifetime physical IPV perpetration weighted % (n) |

OR (95% CI) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood exposures to violence | |||

| Any childhood sexual abuse | |||

| Yes | 9.0* (9/66) | 1.1 (0.4–2.8) | .87 |

| No | 8.3 (36/384) | Referent | |

| Any childhood physical violence | |||

| Yes | 10.9 (38/305) | 3.0 (1.1–8.4)† | .04 |

| No | 3.9* (7/145) | Referent | |

| Any childhood emotional violence | |||

| Yes | 11.9 (19/134) | 1.8 (0.8–3.9) | .17 |

| No | 7.1 (26/312) | Referent | |

| Ever-witnessed IPV in childhood | |||

| Yes | 11.6 (20/149) | 1.7 (0.8–3.6) | .14 |

| No | 7.0 (25/298) | Referent | |

| Witnessed attack in the community | |||

| Yes | 8.7 (23/175) | 1.0 (0.5–2.2) | .90 |

| No | 8.3 (22/274) | Referent | |

OR = odds ratio.

Coefficient of variation greater than 0.30, estimate should be interpreted with caution.

No other childhood exposures to violence or demographic or social characteristics presented in Table 1 were associated with any childhood physical violence and the outcome (perpetration of physical IPV), thus we did not include an adjusted model.

Perpetration of sexual IPV

For young men experiencing each of the five different forms of violence in childhood, prevalence of lifetime perpetration of sexual IPV ranged from 25% for witnessing an attack in the community to 44% for those experiencing sexual violence in childhood (Table 3). After adjustment for confounders, we found statistically significant positive associations between experiencing sexual abuse (adjusted odds ratio 2.3, 95% CI 1.0–4.9, P = .04), and emotional violence (adjusted odds ratio 2.0, 95% CI 1.2–3.5, P = .02) and young men’s perpetration of sexual IPV as a young adult (Table 3). Fourteen percent of young men with no reported exposure to violence in childhood reported perpetrating sexual IPV, while 17%, 20%, 39%, and 44% of young men with reported exposure to one, two, three, or four or more forms of violence in childhood, respectively, reported perpetrating sexual IPV (Table 4). In logistic regression analyses, the adjusted odds ratios for perpetration of sexual IPV increased in a statistically significant gradient fashion, from 1.2 to 1.4 to 3.7 to 4.3 for those with exposures to one, two, three, and four or more forms of violence in childhood, respectively.

Table 3.

Childhood exposures to violence and lifetime perpetration of sexual IPV among ever-partnered males (N = 447) ages 18–24, Malawi

| Any lifetime sexual IPV perpetration weighted % (n) |

OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95%CI)* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood exposures to violence | |||||

| Any childhood sexual abuse | |||||

| Yes | 44.1 (33/66) | 3.1 (1.6–5.9) | .00 | 2.3 (1.0–4.9) | .04 |

| No | 20.3 (81/381) | Referent | |||

| Any childhood physical violence | |||||

| Yes | 27.6 (88/303) | 1.8 (1.0–3.3) | .04 | 1.1 (0.6–2.2) | .7 |

| No | 17.1 (26/144) | Referent | |||

| Any childhood emotional violence | |||||

| Yes | 38.3 (58/134) | 2.8 (1.7–4.6) | .00 | 2.0 (1.2–3.5) | .02 |

| No | 18.2 (55/309) | Referent | |||

| Ever-witnessed IPV in childhood | |||||

| Yes | 31.9 (52/147) | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | .02 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | .21 |

| No | 20.0 (61/297) | Referent | |||

| Witnessed attack in the community | |||||

| Yes | 25.0 (52/173) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | .63 | — | — |

| No | 22.6 (61/273) | Referent | |||

aOR = adjusted odds ratio; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted model includes any childhood sexual abuse, physical violence, emotional violence, witnessed IPV, and close with father.

Table 4.

Childhood exposures to different forms of violence and lifetime perpetration of sexual IPV among ever-partnered males (N = 447) ages 18–24, Malawi

| Any lifetime sexual IPV perpetration weighted % (n) |

OR (95% CI) | P | aOR (95%CI)* | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood exposure to different forms of violence | |||||

| None (ref) | 13.9 (12/76) | .00 | .00 | ||

| One | 16.5 (17/120) | 1.2 (0.4–3.5) | 1.2 (0.4–3.4) | ||

| Two | 19.7† (23/119) | 1.5 (0.6–3.6) | 1.4 (0.6–3.4) | ||

| Three | 39.4 (35/77) | 4.1 (1.6–10.1) | 3.7 (1.5–9.5) | ||

| Four or more | 43.8 (27/55) | 4.9 (1.9–12.4) | 4.3 (1.7–11.3) | ||

aOR = adjusted odds ratio; OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted for close with father.

Coefficient of variation greater than 0.30, estimate should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

In Malawi, nearly all young men—over 8 of 10—reported exposure to one or more forms of violence as a child, with experiencing any physical violence as a child reported most frequently (65%). Likewise, perpetration of IPV, particularly sexual IPV, is common among young men. Twenty-four percent of young men reported perpetrating sexual IPV, a lifetime prevalence that is particularly concerning considering both the young age of the respondents (18–24 years) and the high prevalence of HIV in Malawi, at 11% [5].

Fewer young men reported perpetrating physical IPV compared to sexual IPV. The lower prevalence of lifetime physical IPV may reflect the young age of our sample and is consistent with findings from a multicountry study of men’s perpetration of IPV in Asia and the Pacific [15]. In five of six countries, the prevalence for perpetration of physical IPV only for men aged 18–24 years ranged from4.8% to 10.9%, while the prevalence for perpetration of sexual IPV only ranged from 15.6% to 23.9% [15]. We also found unique patterns of association between exposures to different forms of violence in childhood and young men’s perpetration of physical IPV compared to sexual IPV. For example, young men’s perpetration of physical IPV was associated with childhood physical violence, but not with other exposures to violence in childhood. In contrast, young men’s perpetration of sexual IPV was associated with childhood sexual abuse and emotional violence. While not all men exposed to violence in childhood reported perpetration of IPV later in life, our findings demonstrate a dose-response relationship between young men’s exposure to multiple forms of violence as a child and perpetration of sexual IPV. This finding is consistent with research from the U.S. and England [20,21] and is, to our knowledge, the first research to demonstrate a graded relationship between the number of exposures to different forms of violence in childhood and men’s perpetration of sexual IPV in Malawi. Small numbers for perpetration of physical IPV did not allow us to examine the graded relationship between exposures to multiple forms of violence in childhood and young men’s perpetration of physical IPV; this may represent a focus for future research.

This study has some limitations. Our analysis included a measure of men’s lifetime perpetration of IPV, and it is possible that in some cases, the outcome—young men’s perpetration of IPV, may have occurred before exposures to violence in childhood. Future research may address this limitation by including, for men aged 19 years and older, a measure of young men’s past year perpetration of physical and/or sexual IPV. Reporting of childhood experiences of violence was retrospective, and there exists a potential for recall bias and a possible underestimation of the occurrence of violence [28]. In addition, the items measuring IPV, while capturing lifetime perpetration, did not capture the severity, frequency, or duration of this violence, nor were data available to assess perpetration of emotional IPV. An empirical exploration of the pathways by which exposure to violence in childhood may impact perpetration of IPV is beyond the scope of this analysis but may be addressed in future research. Finally, for this subsample of ever-partnered young men, in some instances, the number of responses for each category was small, impacting both the stability of some estimates and power to detect differences. Despite these limitations, our results are consistent with findings from Kenya and Tanzania measuring young men’s exposure to violence in childhood [29,30] and Asia and the Pacific measuring young men’s perpetration of physical and sexual IPV [17], lending support to the our findings. Future research may benefit from exploring these relationships in a larger sample of men, including older men.

These findings highlight opportunities for future research. This analysis may be replicated using VACS data from other individual countries, or in a multicountry analysis. Future research may further explore the associations between exposures to violence in childhood and young men’s perpetration of IPV with a particular focus on what factors, if any, may mitigate the effect of exposure to violence in childhood on men’s perpetration of IPV.

Conclusions

Programs targeting the prevention of sexual IPV against women in Malawi can benefit from taking into account the high levels of young men’s exposure to violence in childhood. For young men already exposed to violence in childhood, programs and policies can focus on interrupting the intergenerational transmission of violence. In addition, prevention of violence against boys may be seen as primary prevention of IPV against women and prioritized accordingly.

We know that violence is preventable, and there is growing evidence regarding violence prevention programs that are scientifically grounded and politically feasible. The INSPIRE technical package [33], for example, provides examples of evidence-informed actions to prevent violence against children globally, and may be used to help countries, including Malawi, focus their priorities on programs and policies with the greatest potential to reduce violence against children.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the survey participants who shared their experiences of violence so that this information might lead to the prevention of future violence. The authors thank the team leaders and interviewers who took great care in interviewing children and young adults, always placing the privacy and safety of the participants first. The authors thank Juliette Lee and Scott Kegler for their critical input. The Ministry of Gender, Children, Disability and Social Welfare (MoGCDSW), the Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, the United Nations Children’s Fund in Malawi (UNICEF Malawi), and the President’s Emergency Plan For Aids Relief (PEPFAR) conducted the Violence Against Children and Young Women survey in Malawi (VACS Malawi), with funding provided by the government of the United Kingdom. The technical guidance and coordination of this study was provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and implemented by the Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi. Funding for the implementation and coordination of the survey was provided by the government of the United Kingdom.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- [1].Breiding MJ, Basile KC, Smith SG, Black MC, Mahendra R. Intimate partner violence surveillance uniform definitions and recommended data elements version 2.0. Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Dahlberg L, Krug E. Violence—a global public health problem World report on violence and health. 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [3].WHO. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Straus MA. The controversy over domestic violence by women: a methodological, theoretical, and sociology of science analysis In: Arriaga X, Oskamp S, editors. Violence in intimate relationships. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Malawi Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Rockville, MD: National Statistical Office, ICF Macro; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yount KM, DiGirolamo AM, Ramakrishnan U. Impacts of domestic violence on child growth and nutrition: a conceptual review of the pathways of influence. Soc Sci Med 2011;72(9):1534–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Shah PS, Shah J. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. J Women’s Health 2010;19(11):2017–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002;359(9314):1331–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Devries KM, Mak JY, Bacchus LJ, Child JC, Falder G, Petzold M, et al. Intimate partner violence and incident depressive symptoms and suicide attempts: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. PLoS Med 2013;10(5):e1001439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2008;15(4):221–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jewkes RK, Dunkle K, Nduna M, Shai N. Intimate partner violence, relationship power inequity, and incidence of HIV infection in young women in South Africa: a cohort study. Lancet 2010;376(9734):41–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Durevall D, Lindskog A. Intimate partner violence and HIV in ten sub-Saharan African countries: what do the Demographic and Health Surveys tell us? Lancet Glob Health 2015;3(1):e34–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gil-González D, Vives-Cases C, Ruiz MT, Carrasco-Portiño M, Álvarez-Dardet C. Childhood experiences of violence in perpetrators as a risk factor of intimate partner violence: a systematic review. J Public Health 2008;30(1):14–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2012;9(11):e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Alink LRA, van Ijzendoorn MH. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Rev 2015;24(1):37–50. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Violence against children and young women in Malawi: findings from a national survey, 2013. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Gender, Children Disability and Social Welfare of the Republic of Malawi, United Nations Children’s Fund, The Center for Social Research at the University of Malawi, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, Garcia-Moreno C. Prevalence of and factors associated with male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN Multi-country Cross-sectional Study on Men and Violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health 2013;1(4):e187–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Fleming PJ, McCleary-Sills J, Morton M, Levtov R, Heilman B, Barker G. Risk factors for men’s lifetime perpetration of physical violence against intimate partners: results from the international men and gender equality survey (IMAGES) in eight countries. PLoS One 2015;10(3):e0118639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mulawa M, Kajula LJ, Yamanis TJ, Balvanz P, Kilonzo MN, Maman S. Perpetration and victimization of intimate partner violence among young men and women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. J Interpers Violence 2016. pii: 0886260515625910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Machisa MT, Christofides N, Jewkes R. Structural pathways between child abuse, poor mental health outcomes and male-perpetrated intimate partner violence (IPV). PLoS One 2016;17(3):e0150986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Speizer IS. Intimate partner violence attitudes and experience among women and men in Uganda. J Interpersonal Violence 2010;25(7):1224–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hillis SD, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA. Adverse childhood experiences and sexual risk behaviors in women: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Plann Perspect 2001;33(5):206–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics 2004;113(2):320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affective Disord 2004;82(2):217–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Whitfield CL, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ. Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: assessment in a large health maintenance organization. J Interpersonal Violence 2003;18(2): 166–85. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bellis MA, Hughes K, Leckenby N, Perkins C, Lowey H. National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC Med 2014;12:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Bremner JD, Walker JD, Whitfield CH, Perry BD, et al. The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2006;256(3):174–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Violence against children in Kenya: findings from a 2010 national survey. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund e Kenya, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Kenya National Burea of Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Violence against children in Tanzania: findings from a national survey, 2009. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund – Tanzania, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Muhimbili University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Ramiro LS, Madrid BJ, Brown DW. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and health-risk behaviors among adults in a developing country setting. Child Abuse Negl 2010;34(11):842–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].SASÒ 9.3. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [33].World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control, End Violence, Pan American Health Organization, PEPFAR, Together for Girls, UNICEF, UNODC, USAID, The World Bank. INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. WHO, 2016. http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/inspire/en/. [Google Scholar]