Abstract

Until 20 years ago the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) was based on case reports and small series, and was largely ineffectual. As a deeper understanding of the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of PAH evolved over the subsequent two decades, coupled with epidemiological studies defining the clinical and demographic characteristics of the condition, a renewed interest in treatment development emerged through collaborations between international experts, industry and regulatory agencies. These efforts led to the performance of robust, high-quality clinical trials of novel therapies that targeted putative pathogenic pathways, leading to the approval of more than 10 novel therapies that have beneficially impacted both the quality and duration of life. However, our understanding of PAH remains incomplete and there is no cure. Accordingly, efforts are now focused on identifying novel pathogenic pathways that may be targeted, and applying more rigorous clinical trial designs to better define the efficacy of these new potential treatments and their role in the management scheme. This article, prepared by a Task Force comprised of expert clinicians, trialists and regulators, summarises the current state of the art, and provides insight into the opportunities and challenges for identifying and assessing the efficacy and safety of new treatments for this challenging condition.

Short abstract

State of the art and research perspectives in clinical trial design and new therapies for pulmonary arterial hypertension http://ow.ly/VHQ030mfRxc

Current state of clinical trial design and therapeutics in pulmonary arterial hypertension

With advances in our understanding of the pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension (PH) over the past 20 years, more than 10 drugs have been developed and approved for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) and one for chronic thromboembolic PH (CTEPH). Initial clinical trials performed in newly diagnosed PAH and CTEPH were single agent, placebo controlled, of short duration, focused on changes in measures of exercise capacity and comprised of relatively small populations of patients. However, over the past 5 years, clinical trial designs testing novel therapies for PAH have evolved into much larger, placebo controlled, on background therapy and upfront combination therapy trials. In addition, event-driven studies examining the effect of sequential combination therapy on clinical worsening have forced the community to search for more clinically relevant, novel efficacy end-points and trial design. Here, we review the evolution of clinical trial end-points, report on new therapeutic targets, evaluate clinical trial design and propose goals for clinical investigation.

Evolution of end-points in clinical trials of PH

6-min walk test

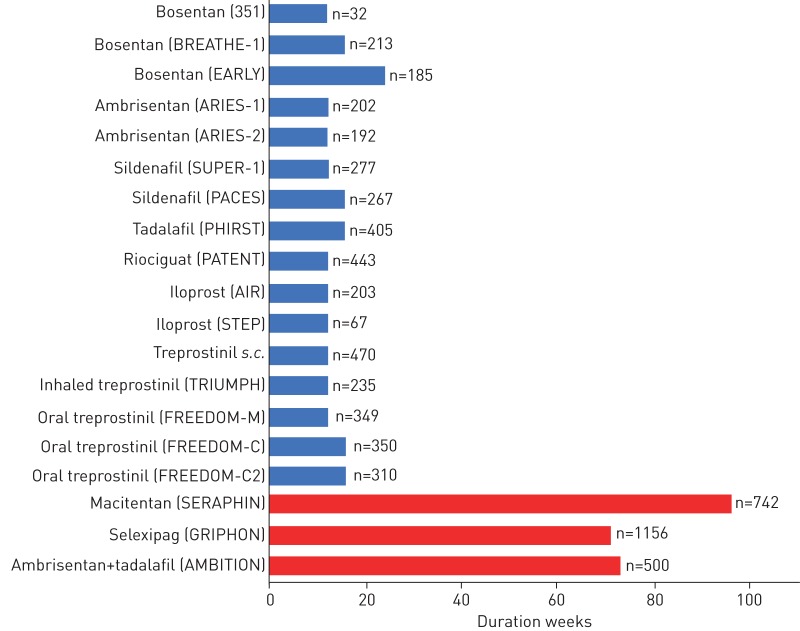

The 6-min walk test (6MWT), a submaximal exercise test, has been the most commonly employed primary end-point in clinical trials of PH therapies, beginning with the first randomised controlled trial (RCT) for drug registration of epoprostenol in 1990 [1]. Since that initial study, most of the registration studies for novel PAH or CTEPH therapies employed short-term change in distance achieved on the 6MWT (Δ6MWD) as the primary outcome (figure 1) [2–13]. These studies identified statistically significant differences in Δ6MWD that resulted in regulatory approval for use in PH, but the clinical relevance of these changes remained less well defined. Multiple studies examining the relationship between Δ6MWD and short- and long-term outcomes, such as need for hospitalisation, lung transplantation, initiation of rescue therapy or death, failed to consistently demonstrate significant associations [14–18]. Subsequent studies defined clinically relevant changes in 6MWD pertaining to patient-important outcomes, such as health-related quality of life and prediction of clinical deterioration [17, 19–21]. However, the utility of Δ6MWD as a primary outcome measure in clinical trials is limited, particularly in more contemporary trials involving sequential, add-on therapy. The change is less than the clinically relevant thresholds described, despite the significance achieved by other clinical outcomes [7–10, 22, 23].

FIGURE 1.

Duration of main registration studies (randomised controlled trials (RCTs)) for currently approved pulmonary arterial hypertension therapies. Blue bars: RCTs with change in 6-min walk distance as primary outcome measure; red bars: RCTs with morbidity and mortality composite primary outcome measure.

Patient-reported outcomes

Alternate outcome measures that are clinically meaningful end-points, measuring how a patient “feels, functions or survives”, are sought by regulatory agencies. In PH, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) now exist, but have been less responsive to therapeutic impact [24–26]. Disease-specific measures need validation in varied languages and need to be included in future clinical trials at all stages of development. The CAMPHOR (Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review) questionnaire, the first PAH/CTEPH-specific questionnaire, is quite lengthy and does not track with other clinical measures over time [27]. The 10-question survey proposed by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK (emPHasis-10) is more efficient, but needs further study [28], and the recently reported SYMPACT study appears to be the more efficient and inclusive, but also needs additional validation [29].

Other surrogate end-points

PH is a disease that lacks strong surrogate end-points [30]. By definition, a surrogate end-point should be: 1) part of the causative pathway from therapy to clinical outcome, 2) its baseline value should be related to clinical outcome, 3) a change in its value should reflect a change in outcome both in direction and magnitude of change, and 4) the estimate of its clinical benefit should be independent of the nature of treatment (e.g. the relationship of change in the surrogate with the outcome should be the same regardless of the intervention that led to the change) [31]. A recent systematic review of surrogate end-points employed in clinical trials of PAH therapy between 1985 and 2013 found that inclusion of invasive measures, such as haemodynamics, as either primary or secondary end-points, significantly decreased over time, while measures of functional capacity, functional status and PROs increased significantly [32].

Evolution to composite outcome end-points

To address some of the limitations of the 6MWT as a primary outcome measure in clinical trials and to explore novel end-points, registration studies in the mid-2000s incorporated composite end-points reflecting time to clinical worsening (TTCW) [6, 7]. Reductions in risk of clinical deterioration noted in these studies motivated the decision to use this composite end-point of morbidity and mortality as the primary outcome in a large registration study of macitentan [22]. The significant reduction in the risk of clinical worsening noted between treatment arms was not reflected by the Δ6MWD. This suggested a distinct effect on the risk of clinical events versus improvement of functional capacity. Similar associations between treatment assignment, TTCW and Δ6MWD were noted in the RCT of selexipag [23]. Combined with data from an RCT of initial combination of ambrisentan and tadalafil versus either one alone demonstrating responsiveness of the measure in a treatment-naive cohort, TTCW is now an approved end-point for PAH therapeutic registration trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers NCT01908699, NCT02932410 and NCT01824290) (table 1).

TABLE 1.

Definitions of time to clinical worsening (TTCW) when used as primary outcome measure in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) clinical trials

| Macitentan versus placebo (SERAPHIN) [22] | Selexipag versus placebo (GRIPHON) [23] | Ambrisentan+tadalafil versus either alone (AMBITION) [102] |

| Worsening PH: | Disease progression: | Disease progression: |

| ≥15% decrease in 6MWD from baseline | ≥15% decrease in 6MWD from baseline | ≥15% decrease in 6MWD from baseline |

| + | + | + |

| Worsening symptoms (WHO FC or signs of right heart failure) | Worsening WHO FC or need for additional PAH therapy | WHO FC III or IV |

| + | ||

| Need for additional PAH therapy | ||

| Hospitalisation for worsening PAH | Hospitalisation for worsening PAH | |

| Start of i.v./s.c. prostanoids therapy | Start of i.v./s.c. prostanoids therapy or LTOT | Start of i.v./s.c. prostanoids therapy |

| Lung transplantation or atrial septostomy | Lung transplantation or atrial septostomy | Lung transplantation or atrial septostomy |

| Unsatisfactory long-term clinical response: | ||

| Any decrease in baseline 6MWD at two consecutive visits | ||

| + | ||

| WHO FC III at two visits separated by at least 6 months | ||

| All-cause death | All-cause death | All-cause death |

PH: pulmonary hypertension; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; WHO: World Health Organization; FC: functional class; LTOT: long-term oxygen therapy.

Limitations to outcome end-points

Future clinical trials need to be more efficient. While TTCW as the primary end-point has been widely accepted, it is not the solution. First, there is no standard definition across trials for TTCW, limiting the ability to compare treatment effects between studies (table 1). Second, each component of a composite end-point should be weighted with respect to clinical importance and frequency of occurrence; the current components of TTCW in PH are not (e.g. death is infrequent and clinical worsening is frequent) [33]. Third, the relationship between clinical worsening and subsequent survival is not well defined and not always adjudicated by an events committee with expertise in PH (table 1) [34]. A more recent analysis utilising data from the SERAPHIN [22] and GRIPHON [23] TTCW trials found a strong association between both symptomatic progression and hospitalisation and mortality at 3, 6 and 12 months [35]. Rigorous studies of the association between TTCW and subsequent events, such as survival, are still needed to fully establish TTCW as a validated surrogate for mortality.

New drug targets for PAH

The currently licensed drugs are directed at correcting the imbalance of vasoactive factors in PAH. There is widespread acceptance that new drugs need to address other pathological mechanisms that drive vascular remodelling. There is no shortage of novel drug targets of potential therapeutic interest; the current challenge is prioritising candidates according to likelihood of success in clinical trials, side-effects, quality of life and cost-effectiveness.

Genetically determined targets

Genetics is a powerful mechanism for identifying and prioritising new drug targets with confidence. Mutations in BMPR2 (bone morphogenetic protein receptor type 2), the most common susceptibility gene for PAH, have focused attention on the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/BMP signalling pathway [36]. To date, the only treatment that has been used to target BMPR2 signalling in clinical trials is FK506 (tacrolimus) [37], which is currently in phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01647945). FK506 binds its pharmacological target FKBP12 (12-kDa FK506-binding protein) and removes it from all three BMPR type 1 receptors (ALK1, ALK2 and ALK3), including those preferred by BMPR2 (ALK1 and ALK3). It is able to activate BMPR2-mediated signalling even in the absence of exogenous ligand and BMPR2.

Strategies proposed for correcting impaired BMPR2 signalling, beyond the aspiration of gene therapy, include pharmacological approaches such as chloroquine (which prevents lysosomal degradation of the BMPR2), ataluren (with the aim of reading through missense mutations) and increasing BMP9 levels [38]. An alternative to increasing BMP signalling is to inhibit TGF-β activity using a novel activin–receptor fusion protein (sotatercept) that competitively binds and neutralises TGF-β superfamily ligands [39]. Potential targets will emerge as we better understand the genetic architecture of PAH, including ion channels (KCNK3 (potassium channel subfamily K, member 3)), aquaporin and SOX17 (SRY-box 17) [36, 40]. Further pre-clinical studies will be needed to realise how these, or their signalling pathways, might be manipulated for therapeutic benefit.

Epigenetic modification

Little is known of the epigenetics of PAH, but studies of histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in pre-clinical cell and animal models have reported beneficial effects, although cardiotoxicity is a concern [41]. Translating the therapeutic potential of HDAC inhibition in PAH will require a clearer insight into the HDAC subtypes involved in the vascular pathology. Likewise, a better understanding of the role of microRNAs in PAH is needed to inform how best to manipulate pharmacologically to have an impact on pulmonary vascular disease [42].

DNA damage

Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) reverses PAH in several animal models [43]. An open-label early phase 1 study of olaparib, an orally available PARP1 inhibitor approved for the treatment of BRCA (breast cancer gene)-related breast cancer, has been proposed in PAH patients in World Health Organization Functional Class II–III on stable vasoactive therapy (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03251872).

Growth factors

The tyrosine kinase receptor imatinib was the first significant compound used in a large-scale trial to directly target vascular remodelling in PAH. Imatinib inhibits platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) receptor-α and -β [44]. PDGF is a trophic factor in vascular cells and lung tissue from PAH patients shows increased expression of PDGF receptors. The phase 3 PAH trial reported a 32 m increase in mean placebo-corrected 6MWD and a reduction in pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) without improvement in TTCW. Unfortunately subdural haematoma occurred in eight patients receiving both imatinib and anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists [45]. However, there remains considerable interest in tyrosine kinase inhibitors, and imatinib in particular, as some patients have stabilised and even improved on imatinib treatment in anecdotal reports. Identifying the clinical and molecular characteristics of patients likely to respond is key to the success of this programme.

Clinical experience with other tyrosine kinase inhibitors urges caution. Indeed, exposure to dasatinib is associated with the development of PAH [46, 47]. In a 16-week, single-centre, open-label trial in 12 patients with PAH, the multikinase/angiogenesis inhibitor sorafenib worsened pulmonary haemodynamics and was associated with adverse events, such as moderate skin reactions on the hands and feet and alopecia [48].

Metabolism

Insulin resistance contributes to the morbidity and mortality of PAH [49]. This has led to interest in the use of agents such as rosiglitazone, metformin and glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists (table 2) [50, 51]. A small clinical trial with metformin is underway, with detailed study of the impact on the right ventricle and pulmonary haemodynamics. Whereas normal myocardium uses fatty acid oxidation as an energy source, the maladapted myocardium relies on glycolysis, which is much less efficient [52]. Glutaminolysis is also induced. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation increases glucose oxidation, leading to the possibility that trimetazidine (an inhibitor of 3-ketoacyl coenzyme A thiolase), approved for angina, may have utility in PAH [53]. Ranolazine, another antianginal agent, is also an option [54].

TABLE 2.

Clinical trials with drugs targeting metabolic dysfunction in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

| Drug tested | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Study design | Study duration | Main inclusion criteria | Primary outcome measure | Secondary outcome measures |

| Fatty acid oxidation: ranolazine and trimetazidine | ||||||

| Ranolazine | NCT02829034 | Multicentre RCT versus placebo | 26 weeks | PH on stable specific therapies but with RV dysfunction (RVEF <45%) | Percentage change in RVEF (assessed by MRI) | |

| Ranolazine | NCT01839110 | Multicentre RCT versus placebo | 26 weeks | PH on stable specific therapies but with RV dysfunction (RVEF <45%) | Number and percentage of subjects with high-risk profile at end of the study | Baseline comparison of the metabolic profiling, microRNA and iPSCs of subjects with and without RV dysfunction |

| Ranolazine | NCT02133352 | Single-centre open-label phase 4 | 26 weeks | PH with LV diastolic dysfunction | Percentage change in mPAP, PAOP and PVR (RHC) | Other haemodynamic variables, 6MWD, MRI, echocardiography and NT-proBNP |

| Ranolazine | NCT01757808 | Phase 1 | 12 weeks | PAH on one or more background specific therapies (including i.v./s.c. prostacyclins) | Change in PVR (RHC) | Change in CPET, RV echocardiography parameters and 6MWD |

| Trimetazidine | NCT03273387 | Single-centre phase 2 and 3 | 12 weeks | PAH | Changes in RV function (MRI) | Changes in cardiac fibrosis level (MRI), NYHA FC and LDH level |

| Glycolysis: dichloroacetate | ||||||

| Dichloroacetate | NCT01083524 | Two-centre open-label phase 1 | 16 weeks | PAH on one or more background oral specific therapies | Safety and tolerability | Change in PVR, 6MWD, RV size and function (MRI), NT-proBNP and lung/RV metabolism (FDG-PET) |

| Modulation of Nrf2 pathway/NF-κB pathway: bardoxolone methyl | ||||||

| Bardoxolone methyl | NCT02036970 (LARIAT) | Multicentre phase 2 RCT versus placebo | 16 weeks | PAH, PH-ILD, subset of patients with group 3 or 5 PH | Change in 6MWD | Determine recommended dose range |

| Bardoxolone methyl | NCT02657356 (CATALYST) | Multicentre phase 3 RCT versus placebo | 24 weeks | PAH-CTD | Change in 6MWD | |

| Bardoxolone methyl | NCT03068130 (RANGER) | Multicentre phase 3 open-label extension | Up to 5 years | Patients with PH who previously participated in RCTs with bardoxolone | Long-term safety | |

| Metabolic syndrome: AMPK signalling and metformin | ||||||

| Hormonal, metabolic and signalling interactions in PAH | NCT01884051 | Observational | 5 years | PAH and healthy subjects | Safety and biomarkers of mechanism | |

| Metformin | NCT03349775 | Early phase 1 | 12 weeks | PH and obesity | Pulmonary vascular haemodynamics at rest and on exercise | Effect on PA endothelial cell phenotypes |

RCT: randomised controlled trial; PH: pulmonary hypertension; RV: right ventricle; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; iPSC: induced pluripotent stem cell; LV: left ventricle; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PAOP: pulmonary artery occlusion pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; RHC: right heart catheterisation; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; CPET: cardiopulmonary exercise testing; NYHA: New York Heart Association; FC: functional class; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; FDG: 18F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose; PET: positron emission tomography; Nrf2: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; ILD: interstitial lung disease; AMPK: AMP-activated protein kinase; PA: pulmonary artery.

In PAH, proliferating cells switch their metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis for ATP production. Dichloroacetate (DCA), which inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, is a potential treatment for PAH [55]. Gene variants that reduce the function of SIRT (sirtuin 33) or UCP2 (uncoupling protein 2) impair the clinical response to DCA. A small clinical study with DCA has shown haemodynamic improvement in genetically susceptible patients [56].

Inflammation and immune modulation

Histological studies of the lung, the presence of circulating autoantibodies and high plasma levels of cytokines in PAH all point to inflammation as a driver of its pathology [57]. Direct investigation of this currently lies with a clinical trial of the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, rituximab, in PAH associated with connective tissue disease (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT01086540), and a trial of tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 receptor antagonist in PAH (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02676947) (table 3). Elafin, an endogenously produced elastase inhibitor, has now progressed to clinical trials [58]. Elafin is pro-apoptotic and decreases neointimal lesions in lung organ culture [59].

TABLE 3.

Clinical trials with drugs targeting inflammation in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH)

| Drug tested | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Study design | Study duration | Main inclusion criteria | Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcome measures |

| Modulation of cytokines pathway: anakinra and tocilizumab | ||||||

| Anakinra | NCT01479010 | Single-centre open-label pilot study: phase 1 and 2 | 4 weeks | PAH (excluding PAH-CTD, ILD, POPH) in FC III despite optimal PAH therapy | Change in peak V′O2 and in V′E/V′CO2 slope (CPET) | Change in biomarkers; correlation between changes in biomarkers and CPET measures |

| Anakinra | NCT03057028 | Single-centre open-label pilot study: phase 1 | 14 days | PAH (excluding PAH-CTD) in FC II or III despite optimal PAH therapy | Change in peak V′O2 and ventilatory efficiency (CPET) | Change in hs-CRP, NT-proBNP, IL-6 and symptoms of heart failure (MLHFQ); correlation between biomarkers and measures of exercise capacity |

| Tocilizumab | NCT02676947 | Open-label: phase 2 (TRANSFORM-UK) | 24 weeks | PAH (excluding PAH-CTD due to SLE, RA and MCTD) | Safety (incidence and severity of adverse events); change in PVR (RHC) | Change in 6MWD, NT-proBNP, WHO FC and QoL |

| Inflammation: ubenimex | ||||||

| Ubenimex | NCT02736149 | Multicentre open-label extension study: phase 2 (LIBERTY-2) | Variable (average 1 year) | PAH on ≥1 PAH-specific therapies, in FC II or III, who completed the phase 2 study | Safety (adverse events) | Change in PVR, 6MWD, WHO FC and BNP/NT-proBNP |

| Ubenimex | NCT02664558 | Multicentre double-blind RCT versus placebo: phase 2 (LIBERTY) | 24 weeks | PAH on ≥1 PAH-specific therapies in WHO FC II or III | Change in PVR | Change in 6MWD, WHO FC, TTCW, QoL and NT-proBNP |

CTD: connective tissue disease; ILD: interstitial lung disease; POPH: portopulmonary hypertension; FC: functional class; V′O2: oxygen uptake; V′E/V′CO2: ventilatory response (minute ventilation/carbon dioxide production); CPET: cardiopulmonary exercise testing; hs-CRP: high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; IL-6: interleukin-6; MLHFQ: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; MCTD: mixed connective tissue disease; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; RHC: right heart catheterisation; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; WHO: World Health Organization; QoL: quality of life; RCT: randomised controlled trial; TTCW: time to clinical worsening.

Oestrogen signalling

Aromatase converts androgens to oestrogen and is evident in the pulmonary vasculature of PAH lungs. A small trial of anastrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, in PAH has reported an increase in 6MWD [60] and a further study is underway (table 4).

TABLE 4.

Clinical trials with drugs targeting other signalling pathways

| Drug tested | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Study design | Study duration | Main inclusion criteria | Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcome measures |

| Modulation of the oestrogen pathway: anastrozole and fulvestrant | ||||||

| Anastrozole | NCT03229499 | RCT versus placebo: phase 2 (PHANTOM) | 24 weeks | PAH in WHO FC I–III; stable PAH-specific therapy allowed | Change in 6MWD | Change in 6MWD (3 and 12 months), RVEF, NT-proBNP, biomarkers, SF-36, emPHasis-10, physical activity (actigraphy), TTCW and bone mineral density |

| Anastrozole | NCT01545336 | Double-blind RCT versus placebo: phase 2 | 12 weeks | PAH in WHO FC I–III on stable PAH-specific therapy | Change in plasma oestradiol and in TAPSE | Change in 6MWD |

| Fulvestrant | NCT02911844 | Open-label: phase 2 | 9 weeks | Post-menopausal female patients with PAH in WHO FC I–III on stable PAH-specific therapy | Change in plasma oestradiol, TAPSE, 6MWD and NT-proBNP | |

| Improvement of oxygenation: acetazolamide | ||||||

| Acetazolamide | NCT02755298 | Double-blind crossover RCT versus placebo: phase 2 and 3 | 5 weeks | Stable patients with pre-capillary PH who are undergoing RHC for a clinical indication | Change in 6MWD | Change in QoL (MLHFQ), maximal ramp CPET, cerebral and muscle tissue oxygenation, daily activity (actigraphy), echocardiography parameters, FC, PRO (SF-36, CAMPHOR), NT-proBNP, etc. |

RCT: randomised controlled trial; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; WHO: World Health Organization; FC: functional class; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; RVEF: right ventricular ejection fraction; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; SF-36: Short Form-36; emPHasis-10: 10-question survey proposed by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association UK; TTCW: time to clinical worsening; TAPSE: tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; PH: pulmonary hypertension; RHC: right heart catheterisation; QoL: quality of life; MLHFQ: Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire; CPET: cardiopulmonary exercise testing; PRO: patient-reported outcome; CAMPHOR: Cambridge Pulmonary Hypertension Outcome Review.

Oxidative and hypoxic stress

Oxidative stress is another mechanism that has been targeted in PAH. In contrast to animal studies [61], a phase 2 study of an inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) failed to show overall improvement [62]. A phase 3 study with bardoxolone methyl in scleroderma has been completed, following some signals of efficacy in phase 2 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02036970). This drug induces the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor that regulates antioxidant proteins, and suppresses activation of the pro-inflammatory factor NF-κB.

Increased expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), specifically HIF1α and HIF2α, in the PAH lung, genetic manipulation in animals [63] and naturally occurring mutations in humans (e.g. Chuvash polycythaemia [64]) highlight the potential importance of hypoxic stress in PAH. Several groups have shown that iron deficiency in the absence of anaemia is common in PAH and is associated with reduced survival in PAH [65]. Open-label studies of i.v. iron replacement in PAH suggest an improvement in exercise capacity [66] and a double-blind study is near completion.

Serotonin and humoral modulation

Serotonin (5-HT) is a potent vasoconstrictor and pro-proliferative factor in pulmonary vascular cells [67]. Terguride, a 5-HT2A/2B receptor antagonist, showed no clinical benefit in a phase 2 study in PAH [68]. This may be explained, in part, because the 5-HT1B receptor is the most highly expressed 5-HT receptor in the pulmonary arteries in PAH lungs. Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 (TPH1) is the rate-limiting enzyme in 5-HT biosynthesis and studies with a selective inhibitor of TPH1 are planned.

There is interest in further examination of the role of augmenting vasoactive intestinal polypeptide activity, despite previous disappointment with inhaled administration [69].

Careful use of β-blockers in stable PAH is safe, but which patients might benefit remains an open question [70]. While angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are importantly renoprotective in scleroderma, they have not been shown to be of benefit in PAH. The homologue of ACE, known as ACE2, converts angiotensin I and angiotensin II to angiotensin-(1–7), angiotensin-(1–9) and angiotensin-(1–5), and is of interest. Decreased ACE2 levels and ACE2 autoantibodies have been reported in PAH [71] and ACE2 replacement using a purified i.v. formulation of soluble recombinant human ACE2 is underway. Two prospective studies examining the effect of the aldosterone antagonist, spironolactone, are also underway.

Pulmonary artery denervation

Pulmonary artery denervation is an interventional therapy aimed at abolishing the sympathetic nerve supply to the pulmonary circulation. In a single-centre study, 13 patients underwent the procedure using a radiofrequency ablation catheter, and significant reductions of mean pulmonary arterial pressure and improvement in 6MWD were reported [72]. Several trials are ongoing to determine efficacy and safety of the procedure in PAH (table 5).

TABLE 5.

Clinical trials investigating pulmonary artery denervation

| Intervention | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Study design | Study duration | Main inclusion criteria | Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcome measures |

| Therapeutic Intra-Vascular UltraSound (TIVUS) system | NCT02516722 | Multicentre open-label study (TROPHY) | 12 months | PAH in WHO FC III on stable double combination therapy other than parenteral PGI2 | Safety (procedure-related AE: 1 month); safety (PAH-related AEs and all-cause death: 12 months) | Change in mPAP, PVR, 6MWD and QoL at 4 months |

| Therapeutic Intra-Vascular UltraSound (TIVUS) system | NCT02835950 | Multicentre open-label study (TROPHY-US) | 12 months | PAH in WHO FC III on stable double combination therapy other than parenteral PGI2 | Safety (procedure-related AE: 1 month); safety (AEs, PAH-related AEs and all-cause death: 12 months) | Change in mPAP, PVR, 6MWD, QoL, NT-proBNP and RV function (MRI and echocardiography) at 6 months |

| Pulmonary artery denervation | NCT02525926 | Multicentre single-blinded RCT versus placebo (DENERV'AP) | 24 weeks | PAH patients in WHO FC III–IV despite dual therapy including a PGI2 or dual oral therapy in patients unable to receive PGI2 therapy | Change in mPAP (RHC) | Change in mPAP (3 months), PVR and other haemodynamic variables (6 months), FC, 6MWD, oxygen dependence, supraventricular arrhythmia, BNP, cardiac troponin, and RV function (echocardiography) |

| PA denervation (+sildenafil) | NCT03282266 | Multicentre single-blinded RCT versus placebo (PADN-CFDA) | 24 weeks | PAH | Change in 6MWD | Change in haemodynamic variables (RHC), RV function (echocardiography) and PAH-related events |

PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; WHO: World Health Organization; FC: functional class; PGI2: prostacyclin I2; AE: adverse event; mPAP: mean pulmonary arterial pressure; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; QoL: quality of life; NT-proBNP: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide; RV: right ventricle; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RHC: right heart catheterisation.

Stem cells

There are a few clinical reports of cell therapy in patients with PAH. In a 12-week open-label controlled study, infusion of autologous endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) improved 6MWD and haemodynamic variables in adult patients with severe PAH [73]. Similar results were observed in children with idiopathic PAH [74]. In the phase 1 PHACeT trial, EPCs transduced with endothelial nitric oxide synthase were administered to patients with PAH [75]. The 6MWD improved significantly at 1, 3 and 6 months post-infusion, by 65, 48 and 47 m, respectively. During the 3-day infusion protocol, no adverse haemodynamic or gas exchange parameters were observed [75].

There are several reasons to believe that therapy with cardiac stem cells such as cardiosphere-derived cells (CDCs) would benefit PAH patients with or without right ventricular dysfunction. CDCs have been demonstrated in pre-clinical models to ameliorate most of the major aberrations that underlie the pathobiology/pathophysiology of both the maladapted right ventricle muscle and the remodelled pulmonary vessels [76]. They are potently angiogenic, antifibrotic and antiapoptotic; they have significant anti-inflammatory effects; they attenuate both oxidative and nitrosative stress; and they attract endogenous stem cells to sites of vascular injury. Recently, the phase 1 trial ALPHA of allogeneic CDCs for PAH was initiated, with the primary objective to determine the maximum feasible dose and safety profile of CDCs administered by central infusion into the right ventricle outflow tract of patients with idiopathic PAH (table 6).

TABLE 6.

Clinical trials investigating cell therapy

| Cells | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Study design | Study duration | Main inclusion criteria | Primary outcome measures | Secondary outcome measures |

| Autologous EPCs transfected with human eNOS | NCT03001414 | Multicentre double-blind crossover RCT versus placebo: phase 2 (SAPPHIRE) | 24 weeks | PAH in WHO FC II–IV on stable PAH-specific therapy | Change in 6MWD | Change in 6MWD (3, 9 and 12 months) and PVR; number of deaths or clinical worsening of PAH; change in RV function (echocardiography and MRI) and QoL (SF-36) |

| Allogeneic human cardiosphere-derived stem cells | NCT03145298 | Phase 1a: open-label; phase 1 (ALPHA) | 1 year | PAH in WHO FC II–III on stable PAH-specific therapy | Safety (gas exchange, haemodynamics); arrhythmia; sudden death; mortality and morbidity | Long-term safety end-points; TTCW (including death) |

| Phase 1b: double-blind RCT versus placebo: phase 1 (ALPHA) | 1 year |

EPC: endothelial progenitor cell; eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase; RCT: randomised controlled trial; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; WHO: World Health Organization; FC: functional class; 6MWD: 6-min walk distance; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance; RV: right ventricle; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; QoL: quality of life; SF-36: Short Form-36; TTCW: time to clinical worsening.

Clinical trial failures

The introduction of several new drugs for the treatment of PAH speaks to the success of drug development in this therapeutic area over the past two decades, but a growing number of clinical trials have not met their primary end-point or have reported major safety concerns (table 7). Limited data are publically available on these studies, but a deeper understanding is important to reduce risk and improve success going forward.

TABLE 7.

Main recent clinical trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension with either negative result or tolerability/safety issues

| Study/compound(s) | Phase | End-point: result | Formal presentation [ref.] | Published [ref.] |

| ASA-STAT: aspirin and simvastatin | 2 | 6MWD: lack of efficacy | Yes | Yes [103] |

| ARROW: selonsertib (ASK-1 inhibitor) | 2 | 6MWD: lack of efficacy | Yes [62] | No |

| Cicletanine (antihypertensive with vasorelaxant and diuretic properties) | 2 | PVR: lack of efficacy | Yes [104] | No |

| Aviptadil (vasoactive intestinal peptide) | 2 | PVR: lack of efficacy | Yes [105] | No |

| IMPRES: imatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) | 3 | 6MWD: positive tolerability and safety issues | Yes | Yes [45] |

| Terguride (partial dopamine agonist and serotonin receptor antagonist) | 2 | 6MWD: lack of efficacy | Yes [68] | No |

| LIBERTY: ubenimex (leukotriene B4 inhibitor) | 2 | PVR: lack of efficacy | No | No |

6MWD: 6-min walk distance; ASK1: apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; PVR: pulmonary vascular resistance.

There is a high attrition rate as drug development progresses through its phases from first-in-human studies to pivotal registration studies. Of a total of 9985 clinical trials from 7455 development programmes between 2006 and 2015, only one in 10 progressed from phase 1 to approval [77]. For cardiopulmonary disease therapeutics the range was 6.6–12.8%. Phase transition success rate ranges for cardiopulmonary diseases are estimated at 58.9–65.3% for phase 1 to 2, 24.1–29.1% for phase 2 to 3 and 55.5–71.1% for phase 3 to new drug application. Despite this poor overall probability of success, drug development for rare disease indications remains one of the more successful programmes across all phases of development [77].

The main reason for terminating the development of a drug is lack of efficacy. 52% of programmes are stopped because of lack of efficacy compared with 21% due to safety concerns [78, 79]. Our limited understanding of the pathological drivers of PH contributes to this trial failure rate. Overemphasis on a single mechanism and the limitations of model systems also constrain drug development [78, 80]. Pre-clinical animal models do not completely reflect true human disease. When tested in the best models, novel therapies have not been evaluated in animals on background PAH therapies. Moreover, pre-clinical studies do not employ rigours such as sample size determination and randomisation, and they have not traditionally evaluated end-points used in human trials. Finally, it is possible that therapeutic responses result from off-target effects (i.e. enhanced blood flow to skeletal muscle), which are usually not evaluated in animal models [78, 80]. Overcoming these potential pre-clinical factors will require a more complete understanding of relevant mechanisms in modern day phenotypes through initiatives such as PVDOMICS (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02980887), and advancement of technologies to improve applicability of ex vivo and in vitro assays. Establishing rigorous standards guiding pre-clinical animal model testing [80] will also likely result in improved selection of therapeutic candidates and minimise the impact of bias and false-positive results when tested in the human clinical trial environment.

Given that clinical trials are more likely to “fail” than succeed, it is important to build in plans to learn from “failure” [81]. The goals and objectives of early-phase clinical trials should be focused on safety, informative biomarkers and identification of responsive subpopulations. While bound by statistical norms, decisions in early-phase trials should not be made based on single p-value thresholds. Basing scientific, business or policy decisions in early development on a “mechanical bright-line rule” such as p-value <0.05 as a threshold of scientific claim justification can lead to incorrect conclusions [82]. Later-phase studies need to be informed by adequate data on dose–response relationships and the characteristics of patients that show an efficacy signal. However, data are generated all along the drug development pathway and it is imperative that these data are available for careful evaluation. This will inform critical analysis of study power, end-points and population selection.

Although commonly used, the term “failure” in the context of clinical trials does not distinguish between well-designed negative studies versus studies that are simply inconclusive due to flawed design or conduct. Moreover, the perception of clinical trial “failure” is complex and depends on perspective. While clinical trialists and scientists may consider interventions that do not meet relevant primary or secondary end-points as “failed”, patients may think of therapies that do not provide symptomatic improvement as unhelpful. Beyond issues of definition and perspective, data from these clinical trials are often not publically disclosed due to a multifaceted set of issues ranging from business agendas and academic disinterest to publication bias. Unsuccessful trials can be as, or even more, informative as “positive” trials. Data from the IMPRES trial serve as a good example [45]. Despite demonstrable improvement in exercise capacity and haemodynamics, the higher rate of serious adverse events and study drug discontinuation ultimately led to the decision to halt development of imatinib mesylate as add-on therapy for PAH. However, the publication and ensuing academic dialogue has empowered discussion around the methodology, dosing and approach to repurposing of therapeutics in PAH. More importantly, the data has augmented discussion of the utility of an integral biomarker as an enrichment strategy for optimum clinical trial candidate selection. The use of selected biomarkers appears to be linked with 13–21% relative increase in probability of successful transition between phases of clinical trial development [77].

Publication of all studies, irrespective of outcome, has the potential for cost reduction, improvement in future trial design, reduction in attrition rates and, most importantly, reduction in the number of clinical trial subjects exposed to ineffective drugs or enrolled in flawed clinical trial designs [83]. In fact, initiatives such as Medical Publishing Insights and Practices (www.mpip-initiative.org) and others supported by pharmaceutical partners, the World Health Organization, and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America have called for transparency in publication of clinical trials protocols and results [83]. We in the PAH scientific community must recognise our ethical obligation to clinical trial subjects who allow us to expose them to investigational interventions with the hope that incremental knowledge will be gained. We are bound by this moral obligation to learn and disseminate knowledge produced by participation of each and every clinical trial subject. A transparent process for reporting and examining negative clinical trials, with the commitment to evaluation of full data sets (not only the top-line data) is essential. The process should exceed current data-sharing policies of individual institutions or medical journals and be funded to allow independently conducted analyses by scientific committees (i.e. data safety monitoring boards) with the necessary expertise (i.e. clinical trialist, ethicist and statistician). The obligation for such reporting processes should be balanced with (but not hindered by) the need for data confidentiality when analysing early-phase proof-of-concept studies.

Challenges for future trial design

The successful development of drugs for PAH has provided significant impact on patient outcomes, but has not yet produced a cure. The surge of novel potential options has created new challenges in clinical care and future drug development programmes. Of course, this is a “good” stress to need to overcome, but it requires thoughtful consideration of novel trial end-points and design. It also means that pharmacological interactions, pharmacodynamics and individual pharmacokinetics will become more important to incorporate into future studies. Novel biomarkers and genetic association discovery will be required to truly develop and personalise therapies. There are still considerable unknowns regarding the mechanisms of action of our current drugs, their in vivo pharmacology and their optimal usage. Additionally, larger trials will, by necessity, need to be more collaborative in order to study potential meaningfulness of disease state biomarkers. Trials in PAH starting from the pre-clinical phase through phases 1 and 2 should focus on “learning” to improve efficiency of the entire enterprise. In addition, the number of patients with an orphan disease who are available to participate in clinical trials is limited. It is imperative to gain the most knowledge with the fewest patients placed at risk.

Future therapies can no longer be studied as de novo treatments with placebo-treated comparator groups. One solution to this dilemma is to implement creative adaptive designs. Informatics technology can allow real-time “adaptation” based on clinical data received, with adjustment of enrolment stratification and outcome targets, and determination of futility [84]. In addition, this technology can allow for testing multiple therapeutic choices if all stakeholders are willing to work together to find the best therapeutic effect. The 2018 US Food and Drug Administration guidance on adaptive designs for clinical trials defined these trials as “a study design that allows for prospectively planned modifications to one or more aspects of the design based on accumulating data from subjects in the trial” [85]. It is important to recognise that once interim monitoring occurs there is little statistical cost in having frequent monitoring from that point forward [86]. These Bayesian models allow statistical inferences to take into account the data-driven adaptations and thus allow trial flexibility [87].

The easiest trial to implement is a phase 2/3 trial that allows an interim “look” to assess whether the experimental arm is effective and therefore worth continuing on to its phase 3 stage [88]. This is a faster, more efficient way to proceed but is limited to trials utilising end-points in phase 2 that occur prior to reaching the definitive end-point needed for phase 3. Issues to address in advance include setting the response rate needed to proceed to phase 3, selecting the end-points and determining if there will be a time lag to allow for data to mature prior to analysis [89]. In contrast, a less traditional approach to be considered might be a multiarm trial with multiple experimental therapies tested against a single control arm [84]. This can be done with efficacy and futility stopping rules for each therapy, and potentially only dropping some of the arms while continuing the study with others [90].

Biomarker-driven trials typically consist of randomised block, marker-enriched and marker-directed designs [87]. Block design uses the biomarker as one of many factors used for randomisation, whereas the biomarker is central to the treatment assignment in marker-directed designs. Marker-enriched designs select a prognostic marker for treatment response or a determinant of higher risk to enhance success [87]. The main adaptive platform combining these concepts is the master protocol approach. The approach or “platform” allows adding new treatment arms in the existing cohort or in new subgroups to an ongoing trial in which several treatments are being tested at once [84]. The downside is that the later added arms can only be compared with the control patients randomised from the identical time-point of enrolment. This is not an easy task to organise as multiple industry partners need to collaborate in the trial design, control and privacy of data, funding, and regulatory requirements [91].

Use of biomarkers in adaptive design can strengthen trial efficiency [92]. Umbrella or basket trials describe master protocols designed to integrate proven molecular, genetic or serological biomarkers that are associated with treatment response. This is now possible in oncology drug development and could be a potential design for PH trials. One example could be the use of a risk assessment tool as a biomarker at enrolment or during the study to stratify subjects. Eventually, the risk tools could then be modified to yield prognosis over time with these new markers. Biomarker-defined subgroups may be small proportions of the total cohort studied with this approach. In addition, the ability to discontinue the study of ineffective therapies and add an arm if the therapy is proven beneficial increases trial efficiency. Depending on the stage of the trial, the evidence required to meet a proven threshold will vary and will need consensus prior to trial initiation [84].

Proposals for future clinical trial design in PAH

Collaboration and utilisation of existing resources are the keys to successful clinical development in PAH therapeutics. The ability to examine data upon completion in both successful and unsuccessful studies should be the rule, not the exception. Results of recent phase 1–2 studies with drugs targeting novel mechanisms of action have not yielded success, due to the heterogeneity of subjects studied, the use of myriad background therapies, the inclusion of patients with mild disease and perhaps selection of the wrong end-points. Rather than using traditional PAH clinical and haemodynamic trial end-points for targeted agents (e.g. 6MWT and PVR), the end-points should be tailored to the disease biology and anticipated mechanistic effects. This approach will allow for potential regulatory consideration of novel biomarkers.

Phase 1–2 goals

-

1)

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics studies should be evaluated, particularly since we know little of the myriad combinations of therapies.

-

2)

These trials should encompass biological and mechanistic markers of disease to better assess responses to therapy.

-

3)

To improve generalisability and interpretation of the changes seen in functional capacity, early drug trials should include more homogenous subject groups.

-

4)

Trials should use risk tools as an enrichment strategy to better phenotype a heterogeneous group.

-

5)

Novel efficacy markers in phase 2 (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging and PROs) should be incorporated and then utilised in phase 3.

It is clear that performing long-term composite event-driven trials will be challenging and may halt the surge of new development by committing study participants for many years [93]. Morbidity and mortality event trials require large numbers of subjects upfront to demonstrate effects even at 1 year [35, 94]. Future clinical trials in PAH will need clinically meaningful end-points that reflect morbidity and mortality as well as how patients feel and function [95]. It is known that a “low-risk” patient profile after initial treatment of PAH is associated with better survival [96–99]: a potential exploratory end-point could be the ability to reach or maintain a “low-risk” status according to the REVEAL (Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management) score [96] or the number of low-risk criteria as defined by the European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society PH guidelines [94, 98, 100, 101].

Phase 2–3 goals

The overarching goal should be to improve patients’ ability to live more functional and fulfilled lives.

-

1)

Examine time to clinical improvement instead of TTCW. This will entail defining clinically significant differences in existing end-points and allowing for derivation of these differences post-trial with novel markers.

-

2)

Utilise change in risk as a marker of efficacy as an exploratory end-point now to examine its predictability as a clinical end-point in the future.

-

3)

Utilise novel biomarkers (serum, plasma, genomics, metabolics and PROs) as an exploratory end-point now to examine its predictability as a clinical end-point in the future.

-

4)

Limit unnecessary post-marketing and small investigator-initiated studies that are unlikely to enhance our scientific knowledge base or improve patient care.

Footnotes

Number 8 in the series “Proceedings of the 6th World Symposium on Pulmonary Hypertension” Edited by N. Galiè, V.V. McLaughlin, L.J. Rubin and G. Simonneau

Conflict of interest: O. Sitbon reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, Actelion Pharmaceuticals and GSK, personal fees from GossamerBio, Arena Pharmaceuticals and Acceleron Pharmaceuticals, and grants and personal fees from Bayer HealthCare, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: M. Gomberg-Maitland is a consultant/data and safety monitoring board member/scientific advisory board member for Actelion, Acceleron, Complexa, Merck, Reata and United Therapeutics. Inova receives research support for her to do research from Actelion, AADi and United Therapeutics.

Conflict of interest: J. Granton has received support from Actelion, Bayer and Pfizer to support investigator-initiated research. He is a member of a steering committee for Bellerophon clinical trial in PAH and an adjudication committee member for a clinical trial sponsored by United Therapeutics.

Conflict of interest: M.I. Lewis reports that the ALPHA study cited is funded by a grant from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (grant CLIN2-09444).

Conflict of interest: S.C. Mathai reports personal fees for consultancy and data and safety monitoring board membership from Actelion, personal fees for consultancy from United Therapeutics, and grants from Scleroderma Foundation, outside the submitted work; and is a member of the Scientific Leadership Council, Pulmonary Hypertension Association and of the Rare Disease Advisory Panel of the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

Conflict of interest: M. Rainisio has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: N.L. Stockbridge has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M.R. Wilkins reports personal fees from Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Bayer HealthCare, GossamerBio and Morphogen-IX, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: R.T. Zamanian is a consultant for Actelion Pharmaceuticals, Merck, Vivus and GossamerBio, and has received grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals; and has a patent FK506, for the treatment of PAH, issued.

Conflict of interest: L.J. Rubin reports personal fees from Actelion, Arena, Bellerophon, SoniVie and Roivant, during the conduct of the study.

References

- 1.Barst RJ, Rubin LJ, Long WA, et al. . A comparison of continuous intravenous epoprostenol (prostacyclin) with conventional therapy for primary pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 1996; 334: 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonneau G, Barst RJ, Galiè N, et al. . Continuous subcutaneous infusion of treprostinil, a prostacyclin analogue, in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002; 165: 800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. . Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olschewski H, Simonneau G, Galiè N, et al. . Inhaled iloprost for severe pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galiè N, Ghofrani HA, Torbicki A, et al. . Sildenafil citrate therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2148–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galiè N, Olschewski H, Oudiz RJ, et al. . Ambrisentan for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension results of the ambrisentan in pulmonary arterial hypertension, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, efficacy (ARIES) study 1 and 2. Circulation 2008; 117: 3010–3019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galiè N, Brundage BH, Ghofrani HA, et al. . Tadalafil therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2009; 119: 2894–2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin VV, Benza RL, Rubin LJ, et al. . Addition of inhaled treprostinil to oral therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 1915–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tapson VF, Torres F, Kermeen F, et al. . Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients on background endothelin receptor antagonist and/or phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (the FREEDOM-C study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2012; 142: 1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tapson VF, Jing Z-C, Xu K-F, et al. . Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients receiving background endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (the FREEDOM-C2 study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2013; 144: 952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jing Z-C, Parikh K, Pulido T, et al. . Efficacy and safety of oral treprostinil monotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized, controlled trial. Circulation 2013; 127: 624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghofrani H-A, Galiè N, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 330–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghofrani H-A, D'Armini AM, Grimminger F, et al. . Riociguat for the treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galiè N, Manes A, Negro L, et al. . A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2009; 30: 394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macchia A, Marchioli R, Marfisi R, et al. . A meta-analysis of trials of pulmonary hypertension: a clinical condition looking for drugs and research methodology. Am Heart J 2007; 153: 1037–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fritz JS, Blair C, Oudiz RJ, et al. . Baseline and follow-up 6-min walk distance and brain natriuretic peptide predict 2-year mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2013; 143: 315–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabler NB, French B, Strom BL, et al. . Validation of 6-minute walk distance as a surrogate end point in pulmonary arterial hypertension trials. Circulation 2012; 126: 349–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savarese G, Paolillo S, Costanzo P, et al. . Do changes of 6-minute walk distance predict clinical events in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension? J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 1192–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathai SC, Puhan MA, Lam D, et al. . The minimal important difference in the 6-minute walk test for patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 186: 428–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farber HW, Miller DP, McGoon MD, et al. . Predicting outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension based on the 6-minute walk distance. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert C, Brown MCJ, Cappelleri JC, et al. . Estimating a minimally important difference in pulmonary arterial hypertension following treatment with sildenafil. Chest 2009; 135: 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick RN, et al. . Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, et al. . Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2522–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomberg-Maitland M, Bull TM, Saggar R, et al. . New trial designs and potential therapies for pulmonary artery hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: D82–D91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rival G, Lacasse Y, Martin S, et al. . Effect of pulmonary arterial hypertension-specific therapies on health-related quality of life: a systematic review. Chest 2014; 146: 686–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khair RM, Nwaneri C, Damico RL, et al. . The minimal important difference in Borg dyspnea score in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13: 842–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCabe C, Bennett M, Doughty N, et al. . Patient-reported outcomes assessed by the CAMPHOR questionnaire predict clinical deterioration in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2013; 144: 522–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yorke J, Corris P, Gaine S, et al. . emPHasis-10: development of a health-related quality of life measure in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2014; 43: 1106–1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chin KM, Gomberg-Maitland M, Channick RN, et al. . psychometric validation of the pulmonary arterial hypertension-symptoms and impact (PAH-SYMPACT) questionnaire: results of the SYMPHONY trial. Chest 2018; 154: 848–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ventetuolo CE, Gabler NB, Fritz JS, et al. . Are hemodynamics surrogate end points in pulmonary arterial hypertension? Circulation 2014; 130: 768–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Temple R. A regulatory authority's opinion about surrogate endpoints In: Nimmo WS, Tucker GT, eds. Clinical Measurement in Drug Evaluation. New York, Wiley, 1995; pp. 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parikh KS, Rajagopal S, Arges K, et al. . Use of outcome measures in pulmonary hypertension clinical trials. Am Heart J 2015; 170: 419–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lajoie AC, Lauzière G, Lega J-C, et al. . Combination therapy versus monotherapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4: 291–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frost AE, Badesch DB, Miller DP, et al. . Evaluation of the predictive value of a clinical worsening definition using 2-year outcomes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a REVEAL Registry analysis. Chest 2013; 144: 1521–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin VV, Hoeper MM, Channick RN, et al. . Pulmonary arterial hypertension-related morbidity is prognostic for mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 71: 752–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gräf S, Haimel M, Bleda M, et al. . Identification of rare sequence variation underlying heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spiekerkoetter E, Sung YK, Sudheendra D, et al. . Randomised placebo-controlled safety and tolerability trial of FK506 (tacrolimus) for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1602449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morrell NW, Bloch DB, ten Dijke P, et al. . Targeting BMP signalling in cardiovascular disease and anaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol 2016; 13: 106–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Komrokji R, Garcia-Manero G, Ades L, et al. . Sotatercept with long-term extension for the treatment of anaemia in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes: a phase 2, dose-ranging trial. Lancet Haematol 2018; 5: e63–e72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ma L, Roman-Campos D, Austin ED, et al. . A novel channelopathy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 351–361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogaard HJ, Mizuno S, Hussaini AAA, et al. . Suppression of histone deacetylases worsens right ventricular dysfunction after pulmonary artery banding in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183: 1402–1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chun HJ, Bonnet S, Chan SY. Translational advances in the field of pulmonary hypertension: translating microRNA biology in pulmonary hypertension. It will take more than “miR” words. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meloche J, Pflieger A, Vaillancourt M, et al. . Role for DNA damage signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 2014; 129: 786–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schermuly RT, Dony E, Ghofrani HA, et al. . Reversal of experimental pulmonary hypertension by PDGF inhibition. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 2811–2821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoeper MM, Barst RJ, Bourge RC, et al. . Imatinib mesylate as add-on therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of the randomized IMPRES study. Circulation 2013; 127: 1128–1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montani D, Bergot E, Günther S, et al. . Pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients treated by dasatinib. Circulation 2012; 125: 2128–2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guignabert C, Phan C, Seferian A, et al. . Dasatinib induces lung vascular toxicity and predisposes to pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest 2016; 126: 3207–3218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomberg-Maitland M, Maitland ML, Barst RJ, et al. . A dosing/cross-development study of the multikinase inhibitor sorafenib in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Clin Pharmacol Therap 2010; 87: 303–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zamanian RT, Hansmann G, Snook S, et al. . Insulin resistance in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2009; 33: 318–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo T-P, et al. . An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 1846–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agard C, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Dumas-de-La-Roque E, et al. . Protective role of the antidiabetic drug metformin against chronic experimental pulmonary hypertension. Br J Pharmacol 2009; 158: 1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Piao L, Fang Y-H, Parikh K, et al. . Cardiac glutaminolysis: a maladaptive cancer metabolism pathway in the right ventricle in pulmonary hypertension. J Mol Med 2013; 91: 1185–1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fang Y-H, Piao L, Hong Z, et al. . Therapeutic inhibition of fatty acid oxidation in right ventricular hypertrophy: exploiting Randle's cycle. J Mol Med 2012; 90: 31–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gomberg-Maitland M, Schilz R, Mediratta A, et al. . Phase I safety study of ranolazine in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ 2015; 5: 691–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sutendra G, Michelakis ED. The metabolic basis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Cell Metab 2014; 19: 558–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michelakis ED, Gurtu V, Webster L, et al. . Inhibition of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase improves pulmonary arterial hypertension in genetically susceptible patients. Sci Transl Med 2017; 9: eaao4583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rabinovitch M, Guignabert C, Humbert M, et al. . Inflammation and immunity in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ Res 2014; 115: 165–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nickel NP, Spiekerkoetter E, Gu M, et al. . Elafin reverses pulmonary hypertension via caveolin-1-dependent bone morphogenetic protein signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191: 1273–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim Y-M, Haghighat L, Spiekerkoetter E, et al. . Neutrophil elastase is produced by pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and is linked to neointimal lesions. Am J Pathol 2011; 179: 1560–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kawut SM, Archer-Chicko CL, DeMichele A, et al. . Anastrozole in pulmonary arterial hypertension. a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 360–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Budas GR, Boehm M, Kojonazarov B, et al. . ASK1 inhibition halts disease progression in preclinical models of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018; 197: 373–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosenkranz S, Feldman J, McLaughlin V, et al. . The ARROW study: a phase 2, prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of selonsertib in subjects with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: OA1983. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimoda LA, Manalo DJ, Sham JS, et al. . Partial HIF-1alpha deficiency impairs pulmonary arterial myocyte electrophysiological responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2001; 281: L202–L208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hickey MM, Richardson T, Wang T, et al. . The von Hippel–Lindau Chuvash mutation promotes pulmonary hypertension and fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 827–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rhodes CJ, Howard LS, Busbridge M, et al. . Iron deficiency and raised hepcidin in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: clinical prevalence, outcomes, and mechanistic insights. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 300–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ruiter G, Manders E, Happé CM, et al. . Intravenous iron therapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and iron deficiency. Pulm Circ 2015; 5: 466–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.MacLean MMR. The serotonin hypothesis in pulmonary hypertension revisited: targets for novel therapies (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm Circ 2018; 8: 2045894018759125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghofrani HA, Al-Hiti H, Vonk Noordegraaf A, et al. . Proof-of-concept study to investigate the efficacy, hemodynamics and tolerability of terguride vs. placebo in subjects with pulmonary arterial hypertension: results of a double blind, randomised, prospective phase IIa study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185: A2496. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Said SI. Vasoactive intestinal peptide in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012; 185: 786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Campen JS, de Boer K, van de Veerdonk MC, et al. . Bisoprolol in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: an explorative study. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tan WSD, Liao W, Zhou S, et al. . Targeting the renin–angiotensin system as novel therapeutic strategy for pulmonary diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2017; 40: 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen SL, Zhang FF, Xu J, et al. . Pulmonary artery denervation to treat pulmonary arterial hypertension: the single-center, prospective, first-in-man PADN-1 study (first-in-man pulmonary artery denervation for treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 62: 1092–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang X-X, Zhang F-R, Shang Y-P, et al. . Transplantation of autologous endothelial progenitor cells may be beneficial in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49: 1566–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu JH, Wang XX, Zhang FR, et al. . Safety and efficacy of autologous endothelial progenitor cells transplantation in children with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: open-label pilot study. Pediatr Transplant 2008; 12: 650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Granton J, Langleben D, Kutryk MB, et al. . Endothelial NO-synthase gene-enhanced progenitor cell therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension: the PHACeT trial. Circ Res 2015; 117: 645–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Middleton RC, Fournier M, Xu X, et al. . Therapeutic benefits of intravenous cardiosphere-derived cell therapy in rats with pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0183557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hay M, Thomas DW, Craighead JL, et al. . Clinical development success rates for investigational drugs. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32: 40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lythgoe MP, Rhodes CJ, Ghataorhe P, et al. . Why drugs fail in clinical trials in pulmonary arterial hypertension, and strategies to succeed in the future. Pharmacol Ther 2016; 164: 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Arrowsmith J. Trial watch: phase III and submission failures: 2007–2010. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011; 10: 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Provencher S, Archer SL, Ramirez FD, et al. . Standards and methodological rigor in pulmonary arterial hypertension preclinical and translational research. Circ Res 2018; 122: 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pocock SJ, Stone GW. The primary outcome fails — what next? N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 861–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA's statement on p-values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat 2016; 70: 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hayes A, Hunter J. Why is publication of negative clinical trial data important? Br J Pharmacol 2012; 167: 1395–1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Korn EL, Freidlin B. Adaptive clinical trials: advantages and disadvantages of various adaptive design elements. J Nat Cancer Inst 2017; 109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.US Food and Drug Administration. Adaptive Design Clinical Trials for Drugs and Biologics: Guidance for Industry. 2018. www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm201790.pdf Date last accessed: November 25, 2018.

- 86.Freidlin B, Korn EL, George SL. Data monitoring committees and interim monitoring guidelines. Control Clin Trials 1999; 20: 395–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barry WT, Perou CM, Marcom PK, et al. . The use of Bayesian hierarchical models for adaptive randomization in biomarker-driven phase II studies. J Biopharm Stat 2015; 25: 66–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bretz F, Schmidli H, König F, et al. . Confirmatory seamless phase II/III clinical trials with hypotheses selection at interim: general concepts. Biom J 2006; 48: 623–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Abrams JS, et al. . Design issues in randomized phase II/III trials. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 667–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Freidlin B, Korn EL, Gray R, et al. . Multi-arm clinical trials of new agents: some design considerations. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 4368–4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Redman MW, Allegra CJ. The master protocol concept. Semin Oncol 2015; 42: 724–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Simon R. Genomic alteration-driven clinical trial designs in oncology. Ann Intern Med 2016; 165: 270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lajoie AC, Guay C-A, Lega J-C, et al. . Trial duration and risk reduction in combination therapy trials for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2018; 153: 1142–1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weatherald J, Boucly A, Sahay S, et al. . The low-risk profile in pulmonary arterial hypertension. time for a paradigm shift to goal-oriented clinical trial endpoints? Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 197: 860–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Newman JH, Rich S, Abman SH, et al. . Enhancing Insights into Pulmonary Vascular Disease through a Precision Medicine Approach. A Joint NHLBI–Cardiovascular Medical Research and Education Fund Workshop Report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017; 195: 1661–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Benza RL, Miller DP, Foreman AJ, et al. . Prognostic implications of serial risk score assessments in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: a Registry to Evaluate Early and Long-Term Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Disease Management (REVEAL) analysis. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 356–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kylhammar D, Kjellström B, Hjalmarsson C, et al. . A comprehensive risk stratification at early follow-up determines prognosis in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018; 39: 4175–4181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Boucly A, Weatherald J, Savale L, et al. . Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hoeper MM, Kramer T, Pan Z, et al. . Mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension: prediction by the 2015 European pulmonary hypertension guidelines risk stratification model. Eur Respir J 2017; 50: 1700740.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, et al. . 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2015; 46: 903–975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery J-L, et al. . 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 67–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Galiè N, Barberà JA, Frost AE, et al. . Initial use of ambrisentan plus tadalafil in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kawut SM, Bagiella E, Lederer DJ, et al. . Randomized clinical trial of aspirin and simvastatin for pulmonary arterial hypertension ASA-STAT. Circulation 2011; 123: 2985–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Waxman A, Oudiz R, Shapiro S, et al. . Cicletanine in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH): results from a phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2012; 40: 3274. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Galiè N, Boonstra A, Evert R, et al. . Effects of inhaled aviptadil (vasoactive intestinal peptide) in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181: A2516. [Google Scholar]