Highlights

-

•

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a morbid disease and can resist medical management.

-

•

Squamous cell carcinoma may develop within a chronic hidradenitis suppurativa lesion.

-

•

Early surgical intervention with skin grafting offers relief from disease morbidly.

-

•

Early skin grafting eliminates risk of untreatable cancer discovery.

Keywords: Hidradenitis suppurativa, Squamous cell carcinoma, Skin neoplasm, Malignant transformation, Surgical management, Fatal outcome

Abstract

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin that has potential for malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The pathogenesis of HS is poorly understood but thought to be from follicular keratinization, occlusion, and rupture of the pilosebaceous unit, followed by an infiltration of inflammatory cells into the dermis. Treatment is challenging due to a lack of effective medical therapies.

Presentation of case

In this case report, we describe a patient with chronic HS that developed into SCC who underwent late surgical intervention after failing medical management. At the time malignant transformation was discovered, the SCC was beyond resectability and ultimately fatal.

Discussion

Based on the morbidity and mortality of chronic HS illustrated in our case and presented in the literature, we advocate for early surgical intervention.

Conclusion

Wide surgical excision offers a near definitive intervention and should at least be considered for all chronic HS patients due to high morbidity and malignant transformation risk.

1. Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is an inflammatory disease of the skin that is characterized by painful subcutaneous nodules in the axillary, inguinal, and anogenital regions. Chronic lesions progress to deep dermal abscesses, draining sinuses, and fistulas accompanied by a malodorous suppuration. Treatment is challenging due to a lack of effective therapies. The pathogenesis is poorly understood but thought to be from follicular keratinization and rupture of the pilosebaceous unit, followed by an infiltration of inflammatory cells into the dermis [1,2]. In the setting of chronic HS, it is possible to develop squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), for which surgical intervention is necessary. In this case report, we describe a patient with chronic HS that developed into SCC, who underwent late surgical intervention after failing medical management. This work has been constructed in accordance with SCARE criteria guidelines for case reports [3].

2. Case report

A 63-year-old male with a 45 pack-year smoking history, BMI 20.8 kg/m2, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, polymyalgia rheumatic and temporal arteritis on steroid therapy, osteoporosis, and chronic hidradenitis suppurativa presented to his local emergency department with fevers, chills, and pus draining from posterior thighs and testicles.

The patient’s HS had been treated for over 30 years with oral and topical antibiotics, chlorhexidine and bleach baths, steroids, and oral retinoids without success. He lived in a small town in rural New York and taught physics at a local college before HS-associated pain forced him to retire at age 61. Nearly forty years before, he traveled across Asia with the U.S. Navy. He had no known exposures, but his military career may have exposed him to a variety of potential carcinogens including petroleum, asbestos, lead, and polychlorinated biphenyls (PBCs). He had no personal or family history of skin neoplasm.

He was initially treated at his local hospital for sepsis and local infection with doxycycline and amoxicillin without improvement. The patient was eventually transferred to our institution after 20 days in the hospital.

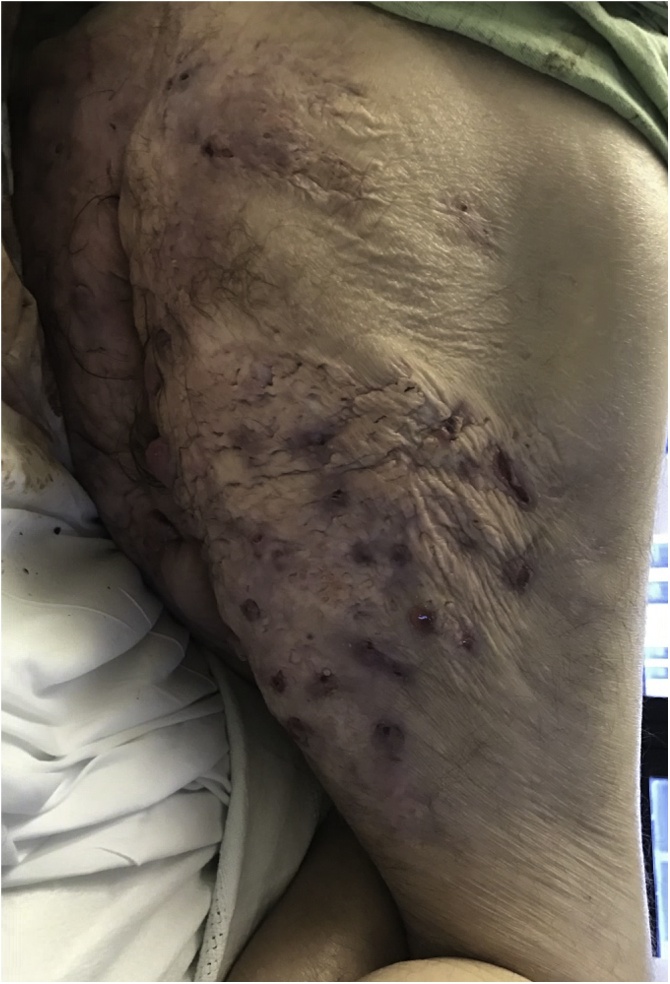

Upon arrival, there were numerous lesions on his medial proximal thigh, scrotal skin, and buttocks without purulence or signs of overt infection (Fig. 1). He was hemodynamically stable and afebrile with a white blood cell count of 11,100 WBC/microliter. Ampicillin/sulbactam was initiated, and the patient conferred with plastic surgery but decided against surgical intervention. He was discharged on antibiotics to a skilled nursing facility four days after admission.

Fig. 1.

Posterior right thigh/buttocks five months prior to surgical intervention. Scars, sinus tracts, cysts, and inflamed nodules present without visible drainage or ulceration.

One month later, the patient presented to dermatology clinic for follow-up. Cysts and inflamed nodules, granulation tissue mounds, and sinus tracts across the inner thighs and buttocks were noted. His hidradenitis was assessed as severe Hurley stage III, and the patient was prescribed adalimumab (Humira), doxycycline, and amoxicillin. He had been offered adalimumab a few months prior but declined due to fear of adverse effects. This time he accepted, but due to generic only insurance plan, he was unable to receive it.

Over the next three months, the patient presented to his local emergency department several times for activity-limiting thigh pain and drainage, until he ultimately returned to our institution for admission. Multiple draining pustules on his thighs and buttocks plus inguinal lymphadenopathy were noted. His white cell count was 9300 WBC/microliter, and he was hypercalcemic (11.1 mg/dL), which was concerning for paraneoplastic response.

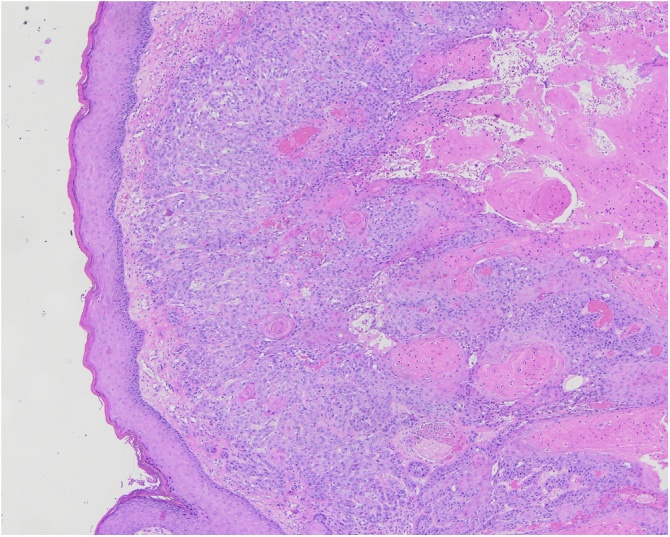

General surgery was consulted and performed incision and drainage with tissue biopsies and wound cultures (Fig. 2, Fig. 3). On post-operative day five, the patient became confused and disoriented with normal vital signs. Meropenem was initiated based on wound cultures positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Proteus mirabilis. Tissue biopsy revealed moderate-to-poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 4). Further imaging showed extensive squamous cell carcinoma invading levator ani muscle (Fig. 5). Due to extensive local disease, further surgical intervention was not an option. Hospice care was pursued, and the patient died 26 days into his last hospital admission.

Fig. 2.

Preoperative image, incision and drainage posterior thigh and buttocks. Visibly draining pustules and ulceration bilaterally with increase in number of inflamed nodules.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative image, incision and drainage posterior thigh and buttocks.

Fig. 4.

Biopsy, buttocks (H&E 4x): squamous cell carcinoma infiltrating into dermis.

Fig. 5.

Postoperative CT image displaying abscess (diameter 3.5 cm) and infiltrative SCC lesion (15 cm × 7 cm).

3. Discussion

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a common disease process, and there is a significant chance for transformation into SCC despite the rarity of cases reported. The prevalence of HS is 1% [3] which, for perspective, is three times the prevalence of HIV/AIDS in the U.S [4], and the incidence of SCC developing from chronic anorectal HS estimated at 3.2% [5]. At least 62 cases of SCC transformation from HS have been reported since 1991, and almost half of these patients died within two years of diagnosis despite receiving surgical intervention [6]. The high mortality may be due to a combination of late recognition, ineffective medical management, and aggressive SCC arising from chronic wounds.

It is known that skin neoplasm developing from chronic wounds or Marjolin’s ulcers are invasive and prone to metastasize, likely due to the paucity of immune cells in scar tissue with contribution from toxins released by local necrosis leading to local mutagenic effects [7]. As a result, neoplasms are more difficult to recognize within the treatment window. At the time of cancer recognition, it may be too late for effective surgical intervention. Medical treatment can reduce complications of HS. Interventions include lifestyle changes, topical and oral antibiotics, hormonal therapy, retinoids, immunotherapy, and radiotherapy. However, no medical treatment can remove sinuses once formed and none have been shown to prevent SCC transformation [8,9]. By the time malignant transformation was discovered in our patient, the cancer was too extensive to be excised. This illustrates how managing chronic, severe HS with observation alone should only be undertaken with careful consideration of malignant transformation potential.

Wide excision has remained the traditional surgical approach to HS with the recurrence rate estimated at 2.5% [10,11]. Surgical excision with skin grafting offers a near definitive intervention, but it is not without risks and challenges. Complete excision can be difficult in patients with advanced disease, and anatomic location can influence approach, but effective reconstructive strategies for various areas exist [12]. Anorectal grafts can be particularly difficult to perform successfully, but grafting is not a necessity, since complete wound healing has been achieved within 8 weeks after excision without grafting. [13]. Colostomy is not a necessity in these patients if the area is able to be kept clean with methods including regular dressing changes and sitz baths [12,13,14]. Timing of surgical intervention is important as well, being that it is preferable to operate outside of acute infection or HS flare [12]. When reflecting on these limitations, it is prudent to consider management with early surgical strategy before patients present with unmanageable, recurrent infection or advanced Hurley stage III disease.

This potential to avoid life-altering morbidity from advancing HS, the reported 3.2% incidence rate of anorectal HS malignant transformation, the aggressive nature of neoplasm arising from these chronic wounds leading to high risk of mortality warrant consideration of early surgical excision with the goal of intervening before medically unmanageable infection, life altering disease, and SCC transformation. Further evaluation of malignant transformation in HS on a large scale would be useful to further inform and support early surgical intervention, since the current estimates are limited by anatomic location and based on decades old data.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Funding

No direct funding sources to report.

Ethical approval

As a case report, this article does not meet the DHHS definition of research and does not require review by our institution’s IRB. Efforts were made by all authors to ensure compliance with HIPAA requirements.

Consent

Patient was deceased at time of written report. Attempts to contact family were made, and they were unsuccessful. A letter to this end, signed by the project leader, was attached to the author form included with thi article upon submissions. Every effort was made to de-identify patient information.

Author contribution

Peter Juviler: primary author, collected gross pathology and CT images.

Ankit Patel: writer and editor.

Yanjie Qi: writer, editor, study design/concept initiator.

Registration of research studies

N/A.

Guarantor

Peter Juviler.

Ankit Patel.

Yanjie Qi.

References

- 1.Paletta C., Jurkiewicz M.J. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1987;14(2):383–390. PMID: 3555949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banerjee A.K. Surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br. J. Surg. 1992;79(9):863–866. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790905. PMID: 1422743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Revuz J.E., Canoui-Poitrine F., Wolkenstein P., Viallette C., Gabison G., Pouget F. Prevalence and factors associated with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from two case-control studies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008;59(4):596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.06.020. PMID: 18674845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Vol. 28. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (HIV Surveillance Report). Published November 2017. (Accessed 15 June 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackman R.J., McQuarrie H.B. Hidradenitis suppurativa; its confusion with pilonidal disease and anal fistula. Am. J. Surg. 1949;77:349. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(49)90162-2. PMID: 18111693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maclean G.M., Coleman D.J. Three fatal cases of squamous cell carcinoma arising in chronic perineal hidradenitis suppurativa. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2007;89(7):709–712. doi: 10.1308/003588407X209392. PMID: 17959012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bazaliński D., Przybek-Mita J., Barańska B., Więch P. Marjolin’s ulcer in chronic wounds – review of available literature. Contemp. Oncol. 2017;21(3):197–202. doi: 10.5114/wo.2017.70109. PMID: 29180925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slade D.E.M., Powell B.W., Mortimer P.S. Hidradenitis suppurativa: pathogenesis and management. Br. J. Plast. Surg. 2003;56(5):451–461. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1226(03)00177-2. PMID: 12890458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith M.K., Nicholson C.L., Parks-Miller A., Hamzavi I.H. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on connecting the tracts. F1000Research. 2017;6:1272. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.11337.1. PMID: 28794864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rompel R., Petres J. Long-term results of wide surgical excision in 106 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol. Surg. 2000;26(7):638–643. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2000.00043.x. PMID: 10886270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mehdizadeh A., Hazen P.G., Bechara F.G., Zwingerman N., Moazenzadeh M., Bashash M. Recurrence of hidradenitis suppurativa after surgical management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015;75(5):S70–S77. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.044. PMID: 26470621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alharbi Z., Kauczok J., Pallua N. A review of wide surgical excision of hidradenitis suppurativa. BMC Dermatol. 2012;12(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-12-9. PMID: 22734714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thornton J.P., Abcarian H. Surgical treatment of perianal and perineal hidradenitis suppurativa. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1978;21(8):573–577. doi: 10.1007/BF02586399. PMID: 738172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]