Abstract

Introduction

Exploring the degree of heritability in a large cohort of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions (FTLD-tau) and determining if different FTLD-tau subtypes are associated with stronger heritability will provide important insight into disease pathogenesis.

Methods

Using modified Goldman pedigree classifications, heritability was examined in pathologically proven FTLD-tau cases with dementia at any time (n = 124) from the Sydney-Cambridge collection.

Results

Thirteen percent of the FTLD-tau cohort have a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, 25% have some family history, and 62% apparently sporadic. MAPT mutations were found in 9% of cases. Globular glial tauopathy was associated with the strongest heritability with 40% having a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance followed by corticobasal degeneration (19%), Pick's disease (8%), and progressive supranuclear palsy (6%).

Discussion

Similar to clinical frontotemporal dementia syndromes, heritability varies between pathological subtypes. Further identification of a genetic link in cases with strong heritability await discovery.

Keywords: Frontotemporal degeneration, Family history, MAPT, Tau, Pathology

1. Introduction

To date, almost all studies investigating strength of family history have been made in clinical cohorts of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) where the underlying pathology is unknown. Heritability varies between clinical FTD syndromes and the effect of strong family history and known gene mutations on patient age of symptom onset and survival is heterogeneous [1], [2], [3], [4]. Mutations in the autosomal dominant microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene account for 20% of FTD cases with strong heritability [5] and are associated with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) with tau-immunopositive inclusions (FTLD-tau), a clinically, genetically, and pathologically heterogeneous group of disorders. Patients with mutations in MAPT were originally considered independently in diagnostic criteria [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], although our recent study proposes the classification of these cases as familial forms of FTLD-tau [11] indicating heritability can now be determined in pathological cohorts. Four main pathological subtypes of FTLD-tau are recognized based on the biochemical composition (3-repeat or 4-repeat tau), morphology of inclusions, and the cellular compartment affected including Pick's disease (PiD), corticobasal degeneration (CBD), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), and globular glial tauopathy (GGT). Neurofibrillary tangle–predominant dementia and argyrophilic grain disease are also recognized pathological subtypes but comprise a small proportion of cases [12], [13].

Heritable forms of clinical FTD syndromes comprise 40% of all cases [14], and approximately 10% of familial cases have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. In contrast to clinical FTD cohorts, no heritability studies have been performed in known pathological subtypes. This study determined the degree of heritability in a large cohort of pathologically proven FTLD-tau cases and determined if different FTLD-tau subtypes are associated with stronger heritability or a mutation in MAPT. Finally, we investigated if cases with a stronger pattern of inheritance differ in their age of onset or disease duration from sporadic FTLD-tau cases.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cases

All pathologically confirmed FTLD-tau cases (n = 124; 51 female) with dementia at any time in their disease course were selected from the Sydney and Cambridge Brain Banks. Participants were prospectively enrolled in longitudinally multidisciplinary research programs investigating neurodegenerative dementias in Cambridge and Sydney and received a clinical diagnosis of an FTD syndrome. Dementia was diagnosed after detailed clinical and neuropsychological assessments, routine blood tests, and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain according to clinical criteria [18], [20]. All cases were recruited with informed consent through regional brain donor programs. The brain donor programs hold ethics approval from the Human Research Ethics Committees of South Eastern Sydney Local Health District and the University of New South Wales (Sydney) and Addenbrooke's Hospital Local Ethics Committee (Cambridge) and comply with the statement on human experimentation issued by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Approval for this study was obtained from the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

2.2. Neuropathological classification into FTLD-tau subtypes

All cases included in this study received a pathological diagnosis of FTLD-tau and were subtyped according to neuropathological diagnostic consensus recommendations [21], [22]. Although all FTLD-tau cases had been classified into pathological subtypes throughout the collection period (1990–2016), cases with a mutation in MAPT were reviewed by three researchers (S.L.F., J.J.K., and G.M.H.) to identify subtype-specific neuropathological features immunoreactive for 3-repeat tau (mouse; 1:50; Cat. No. 05-803; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and 4-repeat tau (mouse; 1:100; Cat. No. 05-804; Abcam) that allow classification into FTLD-tau subtypes [11]. Cases diagnosed with FTLD-tau including PiD, CBD, PSP, GGT, neurofibrillary tangle–predominant dementia, and argyrophilic grain disease were selected for this study. Cases with coexisting pathologies, including Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Lewy body disease [23], [24], [25], or significant vascular pathology were excluded [25], [26]. Specifically, FTLD-tau cases were excluded if they had high or intermediate AD neuropathological change according to NIA-AA criteria [23], [25] or any Lewy body pathology [24], [25]. FTLD-tau cases with a low level of AD neuropathological change were included as these do not fulfill AD criteria [25]. β-Amyloid plaques (A score = 1) [25] were present in less than 20% of the cases [27]. Owing to the pathological significance of Lewy pathology, all Lewy pathologies were excluded. Using recent neuropathological recommendations for vascular pathologies, none of the FTLD-tau cases used in this study had either large or small vessel cerebrovascular disease [28].

2.3. Patient survival and heritability classification

For each patient, a retrospective review of the medical records was conducted to determine age of symptom onset, disease duration, family history of dementia, presence of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or parkinsonism, and whether MAPT mutation was investigated during life. A family history of frontotemporal dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or parkinsonism was obtained from patients, family members, and carers [18]. For heritability classification, each pedigree was graded prospectively using modified Goldman heritability classification criteria [14] (Supplementary 1).

2.4. Genetic screening

MAPT screening using DNA extracted from frozen tissue or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections was performed on cases with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance if they had not been tested during life. All coding exons present in the adult mRNA isoform (exons 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, and 13) were screened by Sanger sequencing [29] or by whole-exome sequencing (Macrogen, Korea). The mutations and their corresponding reference single nucleotide variant numbers (rs ID) are as follows: K257T (rs63750129), P301L (rs63751273), S305S (rs63750568), IVS10+16 (rs63751001), and R406W (rs63750424).

2.5. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics v.24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Basic demographic data were assessed using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests. Nonparametric survival analyses were performed using Kaplan-Meier estimates (95% confidence limits) with post hoc Peto-Peto-Wilcoxon log rank tests. All results are expressed as the median and mean ± standard deviation, and P < .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort demographics

Table 1 summarizes the heritability and demographic details of the FTLD-tau cohort (n = 122, male = 73), which included 121 independent probands. The age of symptom onset and disease duration for the FTLD-tau cohort was 65 (65 ± 8) years and 6 (7 ± 4) years, respectively. Seventy-four FTLD-tau cases presented with a predominant dementia syndrome, and 48 cases presented with a predominant movement disorder and then dementia (note dementia occurred on average before mid-disease). Cases without dementia were excluded. FTLD-tau cases presenting with dementia were 7 years younger than cases presenting with a movement disorder (median 62 [63 ± 8] vs 69 [68 ± 6] years; P < .001).

Table 1.

Demographics of the FTLD-tau cohort

| Demographic variable | Total cohort | FTLD-tau subtypea |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PiD | CBD | PSP | GGT | |||

| Total number | 122 | 26 | 38 | 48 | 10 | |

| bFamilial (known MAPT)c:sporadic | 46 (11):76 | 10 (2):16 | 15 (6):23 | 14 (0):34 | 7 (3):3 | |

| (independent probands) | 45 (10):76 | 10 (2):16 | 14 (5):23 | 14 (0):34 | 7 (3):3 | |

| Goldman scoreb | ||||||

| Median (range) | 4 (1–4) | 4 (1–4) | 4 (1–4) | 4 (1–4) | 4 (1–4) | |

| No. (known MAPT) 1:2:3:3.5:4 | 16 (11):5:8:17:76f | 2(2):3:3:2:16 | 7(6):1:4:3:23 | 3(0):1:1:9:34 | 4(3):0:0:3:3 | |

| % 1–3.5:4 (heritability) | 38:62 | 38:62 | 39:61 | 29:71 | 70:30 | P = .11, φ = 0.22 |

| % 1:2–4 (dominant) | 13:87 | 8:92 | 18:82 | 6:94 | 40:60 | P = .02f, φ = 0.29 |

| Mean ± SD | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 4 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | |

| Gender (male:female) | 73:49 | 17:9 | 23:15 | 27:21 | 6:4 | |

| Age onset (y) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 65 (43–87) | 61 (43–77) | 62 (49–81) | 69 (55–87) | 63 (53–86) | |

| Mean ± SD | 65 ± 8 | 62 ± 7 | 63 ± 8 | 68 ± 6 | 64 ± 11 | |

| Dementiad onset; number | 74 | 25 | 31 | 8i | 10 | |

| Median (range) | 62 (43–86)g | 60 (43–71) | 62 (49–81) | 66 (58–82) | (10) | P < .001g |

| Mean ± SD | 63 ± 8 | 61 ± 7 | 62 ± 8 | 68 ± 7 | 64 ± 11 | |

| Movement disordere onset; number | 48 | 1 | 7h | 40 | - | |

| Median (range) | 69 (55–87)g | 77 | 68 (55–72) | 69 (55–87) | - | |

| Mean ± SD | 68 ± 6 | - | 65 ± 7 | 68 ± 6 | - | |

| Disease duration (y) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 6 (1–20) | 8 (1–16) | 6 (1–20) | 5 (1–12) | 9 (1–17) | P = .67 |

| Mean ± SD | 7 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 | 7 ± 4 | 6 ± 3 | 8 ± 5 | |

| Mean ± SD (dementia onset) | 8 ± 4 | 9 ± 4 | 7 ± 2 | 7 ± 4 | 8 ± 5 | |

Abbreviations: FTLD-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunoreactive inclusions; PiD, Pick's disease; CBD, corticobasal degeneration; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; GGT, globular glial tauopathy; MAPT, microtubule-associated protein tau gene; SD, standard deviation.

Inclusion was a pathological diagnosis of FTLD-tau by neuropathological diagnostic consensus criteria [21], [22] (note: small vessel cerebrovascular and white matter changes overlap with FTLD pathologic changes and hence are ignored) and exclusion of other neuropathologies according to current neuropathological criteria (specifically high and intermediate Alzheimer neuropathologic change, diagnostic cerebrovascular disease, and the presence of any Lewy bodies were excluded [25]).

For heritability classification, each pedigree was classified according to modified Goldman criteria [13].

MAPT gene screening performed according to Dobson-Stone et al., 2017 [27]; two cases were unable to be screened (Table 3).

Longitudinally followed cases in multidisciplinary research studies diagnosed with an FTD syndrome [17], [20].

Longitudinally followed cases in multidisciplinary research studies diagnosed with a movement disorder tauopathy [20].

There was a significant difference in the degree of heritability between pathological subtypes, a higher proportion of GGT cases (40%) had an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance compared with all other subtypes (PiD = 8%, CBD = 18%, PSP = 6%). (P = .02, χ2 test, φ = 0.29).

FTLD-tau cases with a predominant dementia syndrome were 7 years younger than FTLD-tau cases with a predominant movement disorder (P < .001; Mann-Whitney U test).

Of the seven CBD cases with a predominant movement disorder, two had one other affected family member (modified Goldman score = 3 and 3.5) and five cases had no family history (modified Goldman score = 4).

Of the eight PSP cases with a predominant FTD syndrome, once case had a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and showed no mutation in MAPT, one case had one other affected family member (modified Goldman score = 3.5), and six cases had no family history (modified Goldman score = 4).

3.2. FTLD-tau subtype classification

Of the total FTLD-tau cohort (n = 124), 26 cases had a neuropathological diagnosis of PiD, 38 cases had CBD, 48 cases had PSP, 10 cases had GGT, one case each had neurofibrillary tangle–predominant dementia, and argyrophilic grain disease. Representative examples of subtype-specific neuropathological features are shown in Fig. 1. Cases were only assigned a neuropathological diagnosis of argyrophilic grain disease if they did not reach criteria for another FTLD-tau subtype. Concomitant argyrophilic grain disease can occur in 41% of CBD cases and 19% of PSP cases [30]; however, FTLD-tau subtypes with concomitant argyrophilic grain disease were not recorded in this study. Owing to the small representation of neurofibrillary tangle–predominant dementia and argyrophilic grain disease within the FTLD-tau cohort, both cases were not considered in subsequent analyses. Therefore, the effect of heritability and known mutations in MAPT was investigated in FTLD-tau with PiD, CBD, PSP, and GGT pathology (n = 122).

Fig. 1.

Distinguishing neuropathological features in each frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions (FTLD-tau) subtype. Representative images for each FTLD-tau subtype are taken from the same case. Immunoperoxidase sections are counterstained with hematoxylin. Scale bar = 40 μm in (A) also applies to (C, D, F, L) and represents 20 μm in (B, E, G, H, K); 200 μm in (I) and 50 μm in (J). (A, B) Pick bodies in the hippocampal dentate gyrus stained with phosphorylated tau (A; AT8) and modified Bielschowsky silver (B, arrowheads) are characteristic features of Pick's disease. (C, D) AT8-immunopositive astrocytic plaque (C) and AT8-immunopositive white matter threads (D) in the superior frontal cortex are prevalent in corticobasal degeneration. (E, F) Argyrophilic tufted astrocytes in the superior frontal cortex (E) and neurofibrillary tangles in the substantia nigra pars compacta (F) in progressive supranuclear palsy. (G, H) AT8-immunopositive globular oligodendroglial (G) and globular astrocytic (H) inclusions in the precentral cortex in globular glial tauopathy. Globular AT8-immunopositive deposits are present in the proximal aspect of astrocytic processes (arrowheads). (I, J) Severe extracellular neurofibrillary tangles in the hippocampal CA1 region are a feature of neurofibrillary tangle predominant dementia. (K, L) Argyrophilic grains (arrowheads) in the hippocampal CA1 region (K) and AT8-immunopositive thorn-shaped astrocytes (L) in the white matter underlying the medial temporal lobe in argyrophilic grain disease.

3.3. Classification of pedigrees using modified Goldman criteria

Using modified Goldman criteria, approximately 13% had a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 16; modified Goldman score = 1), 4% had a familial aggregation (n = 5; modified Goldman score = 2), 21% had one single affected family member (n = 25; modified Goldman score = 3 and 3.5), whereas the majority 62% had no contributory or unknown family history (n = 76; modified Goldman score = 4). Family history was not known in only a small proportion of cases (n = 4; 3%).

Eleven FTLD-tau cases (9%) with a mutation in MAPT were identified in 10 independent families and included the K257T, P301L, and R406W missense mutations; the silent S305S mutation (two siblings); and intronic mutation IVS10+16 (Table 2). Of the five remaining cases with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, three cases showed no mutation in MAPT and included CBD, PSP, and GGT subtypes. In two PSP cases, frozen tissue was unavailable and DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections was unsuccessful (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mutations in MAPT identified in FTLD-tau subtypes

| MAPT mutation | Exon/intron | FTLD-tau subtype | Age at onset (y) | Disease duration (y) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K257T | 9 | PiD | 64 | 4 |

| K257T | 9 | PiD | 43 | 8 |

| S305Sa | 10 | CBD | 55 | 1 |

| S305Sa | 10 | CBD | 56 | 7 |

| IVS10+16 | 10 | CBD | 57 | 5 |

| IVS10+16 | 10 | CBD | 49 | 13 |

| IVS10+16 | 10 | CBD | 49 | 14 |

| R406W | 13 | CBD | 57 | 17 |

| P301L | 10 | GGT | 54 | 9 |

| IVS10+16 | 10 | GGT | 57 | 1 |

| IVS10+16 | 10 | GGT | 54 | 4 |

Abbreviations: CBD, corticobasal degeneration; GGT, globular glial tauopathy; FTLD-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions; MAPT, microtubule-associated protein tau gene; PiD, Pick's disease.

Siblings, previously reported in Halliday et al. (2006) and Forrest et al. (2018).

Table 3.

FTLD-tau subtypes with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance

| FTLD-tau subtype | Age at onset (y) | Disease duration (y) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| CBD | 72 | 4 | No mutation in MAPT |

| PSP | 61 | 6 | Unsuccessful DNA extraction |

| PSP | 65 | 7 | No mutation in MAPT |

| PSP | 72 | 10 | Unsuccessful DNA extraction |

| GGT | 59 | 8 | No mutation in MAPT |

Abbreviations: CBD, corticobasal degeneration; GGT, globular glial tauopathy; MAPT, microtubule-associated protein tau gene; PSP, progressive supranuclear palsy; FTLD-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions.

3.4. Disease course for each heritability category

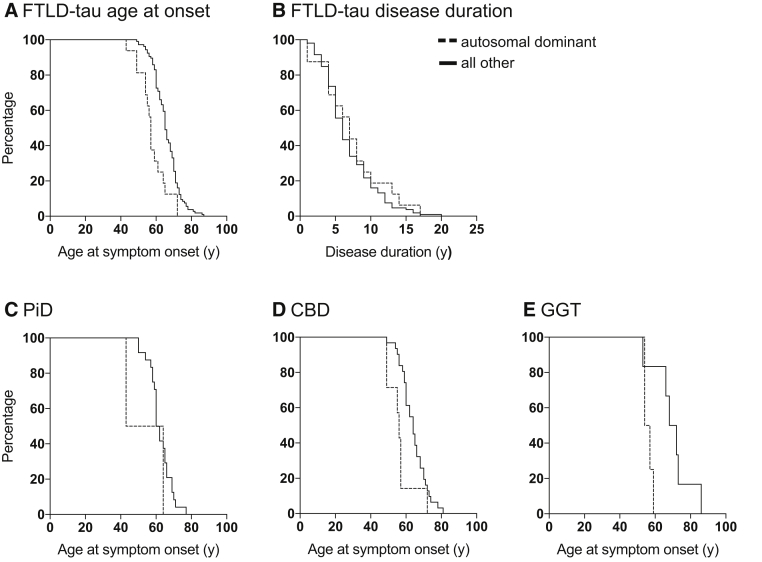

There was a significant difference in age of symptom onset between heritability categories using the modified Goldman criteria (χ2 [4, n = 122] = 22.775; P < .001). Cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 16) were an average of 8 years younger (P < .001; Table 4) at age of symptom onset (57 (58 ± 8) vs 65 (66 ± 7) years) than all other FTLD-tau cases (n = 106). Seventy-five percent of cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance had the onset of symptoms by 61 years (P < .001; Fig. 2A), compared with 75% of all other FTLD-tau cases by 71 years. Disease duration varied widely (from 1 to 20 years) in FTLD-tau cases with no difference observed across modified Goldman scores (P = .67; Table 1). Seventy-five percent of all FTLD-tau cases including those with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance had died within 9 years (Fig. 2B). A similar age of symptom onset and disease duration was found in cases with any family history (n = 46; age onset: 63 [63 ± 8] years; duration: 7 [8 ± 5] years) and cases without family history (n = 76; age onset: 65 [66 ± 8] years, P > .1; duration: 6 [7 ± 3] years, P > .2).

Table 4.

Demographic details of the FTLD-tau cohort within each heritability score

| Demographic variable | Modified Goldman heritability score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 3.5 | 4 | |

| Increasing heritability | |||||

| No. cases (%) | 16 (13) | 5 (4) | 8 (7) | 17 (14) | 76 (62) |

| Age of onset (y) | |||||

| Median | 57a | 60 | 60 | 70 | 65 |

| Mean ± SD | 58 ± 8a | 62 ± 5 | 60 ± 2 | 70 ± 4 | 66 ± 8 |

| Disease duration (y) | |||||

| Median | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Mean ± SD | 7 ± 4 | 8 ± 4 | 8 ± 6 | 8 ± 4 | 7 ± 3 |

Abbreviations: FTLD-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions.

FTLD-tau cases with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 16) according to modified Goldman criteria [13] were significantly younger at the age of symptom onset (P = .001) than all other FTLD-tau cases (n = 106) analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for the FTLD-tau cohort, PiD, CBD, and GGT subtypes. FTLD-tau cases are represented in (A, B). FTLD-tau cases with PiD, CBD, and GGT are represented in (C–E), respectively. (A) FTLD-tau cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 16) were 8 years younger at symptom onset (P < .001) than all other FTLD-tau cases (n = 106). (B) There was no difference in disease duration in FTLD-tau cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. (C) PiD cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 2) were on average younger at symptom onset than all other PiD cases (n = 24). (D) CBD cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 7) were 8 years younger than all other CBD cases (n = 31; P = .01). (E) GGT cases associated with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 4) were on average 14 years younger at age of symptom onset than all other GGT cases (n = 6). Abbreviations: CBD, corticobasal degeneration; FTLD-tau, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions; GGT, globular glial tauopathy; PiD, Pick's disease.

3.5. Heritability of FTLD-tau subtypes

Table 1 summarizes the heritability of each FTLD-tau subtype. Seventy percent of GGT cases (n = 7) had some degree of family history (modified Goldman score < 4), followed by CBD (n = 15; 40%), PiD (n = 10; 39%), and PSP (n = 14; 30%). Of the FTLD-tau subtypes, GGT was associated with the strongest heritability compared with all other subtypes (P = .02) with 40% of cases having a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, followed by CBD (18%), PiD (8%), and PSP (6%) (modified Goldman score = 1). Thirty percent of GGT cases had a mutation in MAPT, followed by 16% of CBD cases and 8% of PiD cases. Mutations in MAPT were not found in PSP cases. The four cases with unknown family history included one case of each PiD and CBD subtypes, and two cases with PSP.

There was a significant difference in the degree of heritability between pathological subtypes (P < .05). A significant difference was also observed in the number of cases with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance across the pathological subtypes (Table 1; P < .05). A higher proportion of GGT cases (n = 4; 40%; P = .02; φ = 0.285) had an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance compared with all other subtypes (PiD: n = 2, 8%, CBD: n = 7, 18%; PSP: n = 3, 6%).

3.6. Disease course in pathological subtypes with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance

PiD, CBD, and GGT subtypes had a large proportion of cases with strong family history and were the only subtypes considered when analyzing the effect of an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance on disease course. The median age of symptom onset and disease duration for PiD cases was 61 (62 ± 7) years and 8 (9 ± 4) years, respectively. Age at symptom onset varied in the two PiD cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (64 and 43 years) and disease duration was 4 and 8 years, respectively (Fig. 2C). The median age of symptom onset and disease duration for CBD was 62 (63 ± 8) years and 6 (7 ± 4) years, respectively (n = 38). CBD cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 7) were significantly younger at symptom onset by 8 years than all other CBD cases (56 [56 ± 8] vs 64 [64 ± 7] years; P = .01; Fig. 2D). The median age of symptom onset and disease duration for GGT was 63 (64 ± 11) years and 9 (8 ± 5) years, respectively (n = 10). GGT cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (n = 4) were approximately 14 years younger than all other GGT cases (n = 6; 56 [56 ± 2] vs 70 [70 ± 11] years, respectively; Fig. 2E), but due to the small sample size, this did not reach significance (P = .11). No difference in disease duration was observed in PiD, CBD, or GGT cases with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance (P > .3).

4. Discussion

This is the first study reporting high heritability in a large cohort of pathologically confirmed FTLD-tau characterized by tau-immunopositive inclusions in distinct cell populations and cellular compartments. A positive family history was found in 38% of cases, a figure almost identical to previous studies using Goldman [14] and other similar [19] classification criteria in all patients with FTLD. However, in the present study, only cases with FTLD-tau were considered, suggesting FTLD-tau is as highly heritable as FTLD with TAR DNA binding protein-43 (TDP-43) deposition. Overall, 13% of the FTLD-tau cohort had a strong family history suggestive of an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and 9% of the cohort had a known mutation in MAPT. Originally considered independently in neuropathological diagnostic criteria [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [22], most neuropathological descriptions and case reports associated with mutations in MAPT were made before their proposed classification as familial forms of FTLD-tau by the identification of the core differentiating features used to identify sporadic forms [11]. Despite a relatively small number of cases with a mutation in MAPT in each FTLD-tau subtype, all cases from the Sydney-Cambridge collection with a mutation in MAPT were included in this study. Similar to clinical FTD syndromes, this study found that each pathological subtype was associated with varying heritability, and GGT and CBD were associated with the strongest heritability and an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. These findings suggest that investigating strength of family history in FTLD-tau as a single entity is likely to underestimate the likelihood of a genetic cause and the identification of mutations in MAPT in some pathological subtypes. This study suggests screening for mutations in MAPT should be considered in cohorts with GGT and CBD with a positive family history, although further validation is required in a larger pathological cohort.

Previous studies have used a variety of measures for assessing heritability in clinical and pathological cohorts. The well-established modified Goldman classification criteria [14], [17] were used in the present study although a limitation is application to patients with unknown family history, which are grouped together with cases that have no known family history, and may have an unrecognized genetic cause. The proportion of cases with a positive family history within the current pathological cohort is likely to be a true estimation of overall heritability as family history was not known in only a small proportion of cases (n = 4; 3%). However, a recent study [31] validating heritability in FTLD using Wood criteria [19] found that 26.6% of cases had family history of unknown significance and mutation carriers in this group had a younger age at symptom onset. This study suggests genetically screening cases with a young age of symptom onset and unknown family history to capture all cases with a potential genetic cause to disease.

Reports of a first or second degree relative with dementia are common in FTD and increase the likelihood of a genetic cause. FTLD-tau families with a strong family history are highly likely to carry a mutation in MAPT [19], mutations that were originally discovered in large families with familial frontotemporal degeneration and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17 [5], [32], [33]. There is increasing awareness of the limitations of assessing family history, particularly in historical case collections, and the lack of a standardized definition of what constitutes family history [34]. In comparison to other neurodegenerative diseases, FTLD is a newly recognized entity and previous generations are more likely to have been diagnosed with AD or another neurodegenerative disease. Cases with a positive family history of dementia or AD in previous generations would have been captured in the modified Goldman criteria used in the present study. It is unlikely that broadening the definition of family history to include any neurodegenerative disease would alter the degree of heritability in the present study. Furthermore, there are a small number of other genetic abnormalities that cause FTLD, but these are not associated with FTLD-tau pathology. Patients with mutations in the valosin-containing protein gene are associated with Paget's disease and FTLD-TDP type D pathology at autopsy [35], [36]. In addition, psychiatric symptoms are common in patients carrying the C9orf72 repeat expansion [37], the most common genetic cause of FTD and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, but this may not have been captured when assessing family history before 2011. However, C9orf72 repeat expansions are associated with TDP-43 and not FTLD-tau pathology.

The present study identified five different mutations in MAPT in 11 cases from 10 unrelated families with strong heritability. How these mutations cause phosphorylated tau deposition in neurons and glia has been recently reviewed [11]. The most recently described FTLD-tau subtype is GGT [21], which is rarer than other pathological forms of FTLD-tau, comprising approximately 10% of cases [11], [38]. This study demonstrates that GGT represents a main pathological subtype among cases with high heritability. Usually considered a sporadic FTLD-tau subtype, GGT was associated with the strongest heritability with seven of the 10 cases having some degree of family history, and one-third of all cases having a known mutation in MAPT. This suggests a proportion of previously unclassified FTLD-tau cases with a mutation in MAPT are likely to comprise cases reaching neuropathological classification criteria for GGT, potentially contributing to the previous under-recognition of this pathological subtype. Two different mutations in MAPT were identified in three cases with GGT pathology, P301L and IVS10+16, in addition to three other mutations previously reported with GGT pathology in exons 1 (R5H [39]), 10 (N296H [40]) and 11 (K317N [41]). Further studies on a larger GGT series are needed to determine if one particular GGT subtype (I-III) is more likely to be associated with mutations in MAPT, as suggested by Tacik et al. 2015 [41]. Similarly, whether MAPT genotype influences pathological phenotype is not well established for all FTLD-tau pathological entities.

In the present study, CBD was the second most heritable subtype with approximately 40% of cases having at least one affected family member, one-third of which have a known mutation in MAPT. Three different MAPT mutations were found in five independent families including S305S, R406W, and IVS10+16. Similar to CBD, approximately 40% of PiD cases had at least one affected family member, but few of these had a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and only two had a known missense mutation in MAPT on exon 9. Missense mutations located outside exon 10 have predominantly neuronal pathology and have been associated with Pick bodies immunopositive for 3-repeat tau, characteristic of PiD [11], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]. This study found most PSP cases have no family history, confirming previous reports that PSP is predominantly sporadic [48]. Only three PSP cases (6%) were found to have strong heritability suggesting an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, and no mutation in MAPT was found in the one case that could be screened. Mutations in MAPT are rarely associated with PSP pathology [49], [50], and in a recent study [50], two sibling pairs with late onset and pathologically proven PSP are not associated with MAPT mutations, suggesting a dominant genetic cause is yet to be discovered. Similarly, one case of each CBD and GGT with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance were not associated with mutations in MAPT.

Although approximately 72% of FTLD cases have symptom onset by 65 years [51], the presence of a mutation in MAPT and/or an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance influences age of symptom onset in FTLD-tau, which was reflected in the CBD and GGT subtypes having an earlier symptom onset by up to 14 years. These findings align with a recent study investigating clinicopathological correlations in early- and late-onset FTD and FTLD, where certain clinical FTD syndromes can predict specific neuropathological diagnoses, including FTLD-tau subtypes, regardless of age of symptom onset [51]. Survival in familial FTLD-tau and in cases with a mutation in MAPT is heterogeneous and varies between studies, which is likely to reflect the clinical and pathological subtypes selected, criteria used to assess strength of heritability, and the type of MAPT mutation [1], [2], [52]. Mutations in MAPT associated with short survival are considered to have a more toxic function and aggressive disease progression [53]. Not surprisingly, because FTLD-tau cases reported in this study have a wide variation in disease duration, including those with a mutation in MAPT, no difference in survival was found in cases with a mutation in MAPT, nor did the degree of heritability affect survival suggesting cases with a mutation in MAPT have a similar disease course as FTLD-tau without mutations.

One limitation of the present study was the inability to screen two PSP cases with strong heritability suggestive of an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance due to the lack of frozen tissue and the inability to extract DNA from formalin-fixed sections. Second, the possibility of a proportion of cases with low heritability harboring a mutation in MAPT cannot be discounted. However, the probability of finding an autosomal dominant gene mutation in FTLD cases with low heritability is small based on previous reports [19]. Similarly, mutations in MAPT are very rare in sporadic cases [54], and for these reasons, cases with low heritability were not included for MAPT screening. Third, the classification of patients with unknown family history is a limitation of the Goldman heritability criteria as described previously. Finally, GGT represents a small proportion of all FTLD-tau cases [11], [38], and the number of cases available for inclusion in this study was relatively low despite including all cases from two well-established brain banks. However, this study represents one of the largest GGT cohorts since the neuropathological diagnostic consensus recommendations were published [21].

4.1. Conclusions

Heritability varies between FTD syndromes but less is known about the heritability of pathological subtypes of FTLD-tau. This study demonstrates that a positive family history was present in a significant proportion of the FTLD-tau cohort and each pathological subtype was associated with varying degrees of heritability. Approaching heritability in FTLD-tau as a single entity is likely to underestimate the degree of heritability and likelihood of a mutation in MAPT across pathological subtypes. Given that a small number of cases in this study had strong family history but showed no mutation in MAPT, suggests additional genetic causes of FTLD-tau await discovery. Together, these findings provide insights into how the combination of underlying pathological subtype and the presence of a mutation in MAPT can influence age of symptom onset. Research focused on different MAPT mutations is required to improve the understanding of FTLD-tau pathogenesis.

Research in Context.

-

1.

Systematic review: Literature was reviewed using combinations of PubMed search terms: frontotemporal, microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT), heritability, tau, and pathology. Heritability varies between clinical syndromes, but there are no data on heritability between pathological subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with tau-immunopositive inclusions (FTLD-tau).

-

2.

Interpretation: Our findings demonstrate FTLD-tau is highly heritable. Each pathological subtype is associated with varying heritability, and screening for MAPT mutations should be considered for globular glial tauopathy and corticobasal degeneration with family history. Three cases with a suggested autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance showed no mutation in MAPT, indicating further identification of a genetic link in cases with strong family history await discovery. MAPT mutation cases are younger at age of symptom onset.

-

3.

Future directions: Research focused on different MAPT mutations is required to improve the understanding of FTLD-tau pathogenesis and how a combination of a MAPT mutation and underlying pathology influences age of symptom onset.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding to ForeFront, a collaborative research group dedicated to the study of frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease, from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) (1132524), Dementia Research Team Grant (1095127) and the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders Memory Program (CE11000102). G.M.H. is an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow (1079679). O.P. is an NHMRC Senior Research Fellow (1103258).

Tissues were obtained from the Sydney and Cambridge Brain Banks. The Sydney Brain Bank is supported by the University of New South Wales and Neuroscience Research Australia. The Cambridge Brain Bank is supported by the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Center. The authors wish to thank donors and their families who made this research possible.

Footnotes

The authors report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dadm.2018.12.001.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.van Swieten J., Spillantini M.G. Hereditary frontotemporal dementia caused by Tau gene mutations. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland) 2007;17:63–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chiu W.Z., Kaat L.D., Seelaar H., Rosso S.M., Boon A.J., Kamphorst W. Survival in progressive supranuclear palsy and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:441–445. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2009.195719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodges J.R., Davies R., Xuereb J., Kril J., Halliday G. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61:349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capozzo R., Sassi C., Hammer M.B., Arcuti S., Zecca C., Barulli M.R. Clinical and genetic analyses of familial and sporadic frontotemporal dementia patients in Southern Italy. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13:858–869. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hutton M., Lendon C.L., Rizzu P., Baker M., Froelich S., Houlden H. Association of missense and 5'-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arendt T., Stieler J.T., Holzer M. Tau and tauopathies. Brain Res Bull. 2016;126:238–292. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs G.G. Invited review: Neuropathology of tauopathies: principles and practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41:3–23. doi: 10.1111/nan.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lashley T., Rohrer J.D., Mead S., Revesz T. Review: An update on clinical, genetic and pathological aspects of frontotemporal lobar degenerations. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2015;41:858–881. doi: 10.1111/nan.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rademakers R., Neumann M., Mackenzie I.R. Advances in understanding the molecular basis of frontotemporal dementia (vol 8, p 423, 2012) Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:240. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohrer J.D., Lashley T., Schott J.M., Warren J.E., Mead S., Isaacs A.M. Clinical and neuroanatomical signatures of tissue pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2011;134:2565–2581. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forrest S.L., Kril J.J., Stevens C.H., Kwok J.B., Hallupp M., Kim W.S. Retiring the term FTDP-17 as MAPT mutations are genetic forms of sporadic frontotemporal tauopathies. Brain. 2018;141:521–534. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jellinger K.A., Attems J. Neurofibrillary tangle-predominant dementia: comparison with classical Alzheimer disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Josephs K.A., Hodges J.R., Snowden J.S., Mackenzie I.R., Neumann M., Mann D.M. Neuropathological background of phenotypical variability in frontotemporal dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:137–153. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0839-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohrer J.D., Guerreiro R., Vandrovcova J., Uphill J., Reiman D., Beck J. The heritability and genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2009;73:1451–1456. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bf997a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seelaar H., Kamphorst W., Rosso S.M., Azmani A., Masdjedi R., de Koning I. Distinct genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2008;71:1220–1226. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319702.37497.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nilsson C., Landqvist Waldo M., Nilsson K., Santillo A., Vestberg S. Age-related incidence and family history in frontotemporal dementia: Data from the Swedish Dementia Registry. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldman J.S., Farmer J.M., Wood E.M., Johnson J.K., Boxer A., Neuhaus J. Comparison of family histories in FTLD subtypes and related tauopathies. Neurology. 2005;65:1817–1819. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187068.92184.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Po K., Leslie F.V., Gracia N., Bartley L., Kwok J.B., Halliday G.M. Heritability in frontotemporal dementia: more missing pieces? J Neurol. 2014;261:2170–2177. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7474-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wood E.M., Falcone D., Suh E., Irwin D.J., Chen-Plotkin A.S., Lee E.B. Development and validation of pedigree classification criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1411–1417. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chare L., Hodges J.R., Leyton C.E., McGinley C., Tan R.H., Kril J.J. New criteria for frontotemporal dementia syndromes: Clinical and pathological diagnostic implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:865–870. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmed Z., Bigio E.H., Budka H., Dickson D.W., Ferrer I., Ghetti B. Globular glial tauopathies (GGT): consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:537–544. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cairns N.J., Bigio E.H., Mackenzie I.R., Neumann M., Lee V.M., Hatanpaa K.J. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:5–22. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0237-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H., Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braak H., Del Tredici K., Rub U., de Vos R.A., Jansen Steur E.N., Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24:197–211. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montine T.J., Phelps C.H., Beach T.G., Bigio E.H., Cairns N.J., Dickson D.W. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease: A practical approach. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0910-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thal D.R., von Arnim C.A., Griffin W.S., Mrak R.E., Walker L., Attems J. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration FTLD-tau: preclinical lesions, vascular, and Alzheimer-related co-pathologies. J Neural Transm (vienna) 2015;122:1007–1018. doi: 10.1007/s00702-014-1360-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan R.H., Kril J.J., Yang Y., Tom N., Hodges J.R., Villemagne V.L. Assessment of amyloid beta in pathologically confirmed frontotemporal dementia syndromes. Alzheimers Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2017;9:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalaria R.N. The pathology and pathophysiology of vascular dementia. Neuropharmacology. 2018;134:226–239. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dobson-Stone C., Kwok J.B. Finding MAPT Mutations in Frontotemporal Dementia and Other Tauopathies. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1523:307–324. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6598-4_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Togo T., Sahara N., Yen S.H., Cookson N., Ishizawa T., Hutton M. Argyrophilic grain disease is a sporadic 4-repeat tauopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2002;61:547–556. doi: 10.1093/jnen/61.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fostinelli S., Ciani M., Zanardini R., Zanetti O., Binetti G., Ghidoni R. The Heritability of Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration: Validation of Pedigree Classification Criteria in a Northern Italy Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;61:753–760. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poorkaj P., Bird T.D., Wijsman E., Nemens E., Garruto R.M., Anderson L. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spillantini M.G., Murrell J.R., Goedert M., Farlow M.R., Klug A., Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner M.R., Al-Chalabi A., Chio A., Hardiman O., Kiernan M.C., Rohrer J.D. Genetic screening in sporadic ALS and FTD. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:1042–1044. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-315995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watts G.D., Wymer J., Kovach M.J., Mehta S.G., Mumm S., Darvish D. Inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia is caused by mutant valosin-containing protein. Nat Genet. 2004;36:377–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neumann M., Mackenzie I.R., Cairns N.J., Boyer P.J., Markesbery W.R., Smith C.D. TDP-43 in the ubiquitin pathology of frontotemporal dementia with VCP gene mutations. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:152–157. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31803020b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burrell J.R., Halliday G.M., Kril J.J., Ittner L.M., Gotz J., Kiernan M.C. Lancet; London, England: 2016. The frontotemporal dementia-motor neuron disease continuum. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burrell J.R., Forrest S., Bak T.H., Hodges J.R., Halliday G.M., Kril J.J. Expanding the phenotypic associations of globular glial tau subtypes. Alzheimers Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2016;4:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hayashi S., Toyoshima Y., Hasegawa M., Umeda Y., Wakabayashi K., Tokiguchi S. Late-onset frontotemporal dementia with a novel exon 1 (Arg5His) tau gene mutation. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:525–530. doi: 10.1002/ana.10163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iseki E., Matsumura T., Marui W., Hino H., Odawara T., Sugiyama N. Familial frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism with a novel N296H mutation in exon 10 of the tau gene and a widespread tau accumulation in the glial cells. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;102:285–292. doi: 10.1007/s004010000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tacik P., DeTure M., Lin W.L., Sanchez Contreras M., Wojtas A., Hinkle K.M. A novel tau mutation, p.K317N, causes globular glial tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:199–214. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1425-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rizzini C., Goedert M., Hodges J.R., Smith M.J., Jakes R., Hills R. Tau gene mutation K257T causes a tauopathy similar to Pick's disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:990–1001. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.11.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickering-Brown S., Baker M., Yen S.H., Liu W.K., Hasegawa M., Cairns N. Pick's disease is associated with mutations in the tau gene. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:859–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hogg M., Grujic Z.M., Baker M., Demirci S., Guillozet A.L., Sweet A.P. The L266V tau mutation is associated with frontotemporal dementia and Pick-like 3R and 4R tauopathy. Acta Neuropathol. 2003;106:323–336. doi: 10.1007/s00401-003-0734-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van Deerlin V.M., Forman M.S., Farmer J.M., Grossman M., Joyce S., Crowe A. Biochemical and pathological characterization of frontotemporal dementia due to a Leu266Val mutation in microtubule-associated protein tau in an African American individual. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:471–479. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Irwin D.J., Brettschneider J., McMillan C.T., Cooper F., Olm C., Arnold S.E. Deep clinical and neuropathological phenotyping of Pick disease. Ann Neurol. 2016;79:272–287. doi: 10.1002/ana.24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bronner I.F., ter Meulen B.C., Azmani A., Severijnen L.A., Willemsen R., Kamphorst W. Hereditary Pick's disease with the G272V tau mutation shows predominant three-repeat tau pathology. Brain. 2005;128:2645–2653. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dickson D.W., Rademakers R., Hutton M.L. Progressive supranuclear palsy: pathology and genetics. Brain Pathol (Zurich, Switzerland) 2007;17:74–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2007.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanford P.M., Halliday G.M., Brooks W.S., Kwok J.B., Storey C.E., Creasey H. Progressive supranuclear palsy pathology caused by a novel silent mutation in exon 10 of the tau gene: Expansion of the disease phenotype caused by tau gene mutations. Brain. 2000;123:880–893. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.5.880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujioka S., Sanchez Contreras M.Y., Strongosky A.J., Ogaki K., Whaley N.R., Tacik P.M. Three sib-pairs of autopsy-confirmed progressive supranuclear palsy. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21:101–105. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seo S.W., Thibodeau M.P., Perry D.C., Hua A., Sidhu M., Sible I. Early vs late age at onset frontotemporal dementia and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2018;90:e1047–e1056. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fujioka S., Algom A.A., Murray M.E., Strongosky A., Soto-Ortolaza A.I., Rademakers R. Similarities between familial and sporadic autopsy-proven progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2013;80:2076–2078. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b2eb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halliday G., Bigio E.H., Cairns N.J., Neumann M., Mackenzie I.R., Mann D.M. Mechanisms of disease in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Gain of function versus loss of function effects. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;124:373–382. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-1030-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pottier C., Ravenscroft T.A., Sanchez-Contreras M., Rademakers R. Genetics of FTLD: Overview and what else we can expect from genetic studies. J Neurochem. 2016;138:32–53. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.