Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Vaccine therapy in combination with radiation therapy may improve distant and/or local control in prostate cancer. We present long-term follow-up data on the secondary and exploratory endpoints of safety and biochemical failure, respectively, from patients with clinically localized prostate cancer treated definitively with a poxviral vector-based therapeutic vaccine combined with external beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

METHODS:

Thirty-six prostate cancer patients received definitive EBRT plus vaccine. A total of 18 patients were treated with adjuvant standard-dose interleukin-2 (S-IL-2) (4 MIU m − 2) and 18 were treated with very low-dose IL-2 (M-IL-2) (0.6 MIU m − 2). Seven patients were treated with EBRT alone. Twenty-six patients treated with EBRT plus vaccine returned for follow-up, and we reviewed the most recent labs and clinical notes of the remaining patients.

RESULTS:

Median follow-up for the S-IL-2, M-IL-2 and EBRT-alone groups was 98, 76 and 79 months, respectively. Actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability was 78%, 82% and 86% (P=0.58 overall), respectively. There were no significant differences between the actuarial overall survival and the prostate cancer-specific survival between the two vaccine arms. Of the 26 patients who returned for follow-up, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group grade ⩾2 genitourinary (GU) and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity was seen in 19% and 8%, respectively, with no difference between the arms (P=1.00 and P=0.48 for grade ⩾2 GU and GI toxicity, respectively). In all, 12 patients were evaluated for PSA-specific immune responses, and 1 demonstrated a response 66 months post-enrollment.

CONCLUSIONS:

We demonstrate that vaccine combined with EBRT does not appear to have significant differences with regard to PSA control or late-term toxicity compared with standard treatment. We also found limited evidence of long-term immune response following vaccine therapy.

Keywords: radiotherapy, therapeutic vaccine, immunotherapy, PROSTVAC

INTRODUCTION

Among men in the United States, prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death. Multiple randomized clinical trials of dose-escalated radiation therapy and androgen-deprivation therapy (ADT) plus definitive radiation therapy have shown improved outcomes.1 – 3 Yet approximately 10 to 60% of patients will have PSA recurrence following definitive radiation therapy.4 – 7 For some patients, this rising PSA indicates only local recurrence, but for others, especially those who originally presented with high-risk disease, it is evidence of distant micrometastatic disease.7 It is unclear whether concurrent and/or adjuvant therapies in patients at high risk of PSA relapse can effectively decrease localized prostate cancer recurrences and target micrometastatic disease. We hypothesized that vaccine therapy in combination with radiation therapy may improve both local and distant control. Here, we report long-term follow-up (LTFU) data on the secondary and exploratory endpoints of safety and biochemical failure from a cohort of patients with clinically localized prostate cancer treated definitively with radiation therapy with or without vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients who were considered candidates for definitive external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (low, intermediate or high risk for biochemical failure) were enrolled onto a randomized phase II trial8 approved by the National Cancer Institute’s Institutional Review Board and conducted at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, MD, USA. Initially, patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to EBRT with vaccine or EBRT alone. The EBRT-only arm was used to control for radiation-induced changes, such as induction of local inflammation and initiation of apoptosis, either of which could potentially stimulate PSA-specific T-cell responses. Patients were stratified by ADT vs no ADT and EBRT alone vs EBRT brachytherapy boost. The study was designed to have 20 patients receive radiation therapy with vaccine and 10 to receive radiation therapy without vaccine. As a result of stratification factors the final enrollment was not 20:10. It was designed to have an 80% power to detect a 1 s.d. difference in the change in PSA-specific T cells compared with baseline, with a one-tailed 0.05 α level test. As the primary endpoint of this trial was immunologic, with the ELISPOT assay as the readout, all patients were required to be human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-A2+.

Radiation therapy could be given to patients by their local radiation oncologist, and guidelines suggested a total dose of EBRT of ⩾70 Gy, with 1.8 to 2.0 Gy fractions. All patients with high-risk disease received ADT; however, patients with intermediate-risk disease were not required to receive ADT but could receive it at the discretion of the treating radiation oncologist.

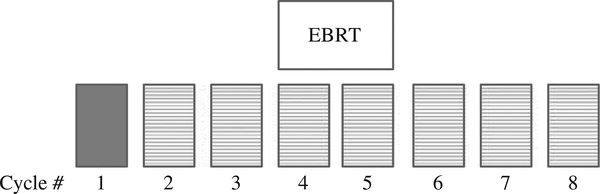

A priming vaccination consisting of an admixture of two recombinant vaccinia vectors expressing PSA or the human T-cell costimulatory molecule B7.1 was followed by seven subsequent monthly boosts with a recombinant fowlpox virus expressing PSA. All vaccines were given on day 2 of each 28-day cycle, with sargramostim (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) 100 μg day − 1 given subcutaneously at the vaccination site on days 1 – 4 and aldesleukin (IL-2) 4 MIU m − 2 given subcutaneously in the abdomen on days 8 – 12. Standard EBRT was given between the fourth and sixth vaccinations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patients treated with vaccine received 3 monthly vaccines before external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). The initial vaccine was given with an admixture of rV-PSA and rV-B7.1 (solid box) with follow-up monthly boosts given with recombinant fowlpox PSA (boxes with the hatched lines).

A total of 19 patients were enrolled on the vaccine plus EBRT arm and 11 on the EBRT-only arm. Following completion of this study, it was noted that significant toxicities were associated with the administration of adjuvant standard-dose interleukin-2 (S-IL-2) (4 MIU m − 2). As a result of the observed toxicities, the study was amended and a subsequent cohort of 18 patients was enrolled and treated with vaccine plus EBRT and very low-dose IL-2 (M-IL-2) (0.6 MIU m − 2) on days 8 to 21 as a vaccine adjuvant.8,9

Study design and endpoints

The primary objective of this study was to determine if a PSA-specific T-cell response to vaccine could be mounted in the face of radiation therapy, the results of which have been published.8 Our purpose here is to report on the secondary and exploratory endpoints of safety and biochemical failure. Although the Phoenix definition (PSA nadir + 2) of PSA failure was not standard in 2000 when this study was originally approved, it has since been adopted as the standard definition of PSA failure, and is used as such herein.

The original protocol called for patients to be seen monthly for 9 months, then every 3 months until biochemical failure or 2 years, whichever came first. Complete interval history, physical examination, blood chemistries, hemogram and serum PSA were obtained at each clinic visit.

All patients who received vaccine therapy were invited by telephone to return to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for an LTFU visit to have a full history and physical, complete an Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) questionnaire, and have blood drawn for PSA and immunological studies. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) criteria were used to assess late-term toxicity. If patients were unable to return to the NIH, permission was sought to obtain their most recent PSA and clinic visit notes from their local treating physicians. For patients treated with EBRT, permission was granted to obtain their most recent PSA and clinic notes from their local treating physicians.

Immunologic assays

Apheresis to collect mononuclear cells, ELISPOT assays and serologic analysis were performed as previously described.8,10,11 Briefly, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained at the patient’s follow-up visit from 60 ml of blood collected in heparinized tubes. The mononuclear fraction was separated by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient separation, washed thrice and frozen in 90% heat-inactivated human AB serum and 10% dimethylsulphoxide at −80 °C at a concentration of 1 × 107 cells ml − 1 until assayed. Cells were thawed and cultured overnight in RPMI 1640 complete (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at 37 °C at 5% CO2 before performing the ELISPOT assay.

For the ELISPOT assay, specific T-cell frequency of HLA-A2+ patients was measured by interferon-γ release in response to stimulation with HLA-A2-restricted PSA3A agonist peptide (VLSNDVCAQV) and MUC1 agonist (ALWGQDVTSV), human immunodeficiency virus pol peptide (ILKEPVHGV) was used as a negative control, and flu peptide (mp 58–66 GILGFVFTL) was used as a positive control. A modification of the procedure described by Arlen et al.10,11 was performed using K562/A*02.1 as antigen-presenting cells. Antigen-presenting cells with no peptide served as the negative control and an HLA-A2-restricted flu peptide as positive control. Results are reported as precursor frequency.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics were compared among the S-IL-2, M-IL-2 and EBRT-only arms using the Kruskal-Wallis test, and Mehta’s modification to Fisher’s Exact Test.

Actual per-patient follow-up times on all patients were used to calculate the statistics on follow-up. This was determined from on-study date until date of death or from on-study date until date of last follow-up. Time to PSA failure was determined from on-study date until PSA failure was noted or until the last PSA determination (for those without PSA failure). Survival was calculated from the on-study date until date of death or date last known alive. Actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability, overall survival and prostate cancer-specific survival were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences among the groups determined by the log-rank test. A comparison of percent PSA failure by risk group across the three studied arms was performed by testing for the homogeneity of odds ratios based on low + intermediate vs high-risk patients.

Grade ⩾2 RTOG late gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) toxicity was compared between the two treatment arms (S-IL-2 vs M-IL-2) using Fisher’s exact test.

Health-related quality of life parameters were compared between the two treatment arms (S-IL-2 vs M-IL-2) using the exact Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Summary values for a given domain (urinary, bowel, sexual and hormonal) were the average values per person for function and bother, averaged over all subjects.

All P-values are two-tailed and reported without adjustment for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

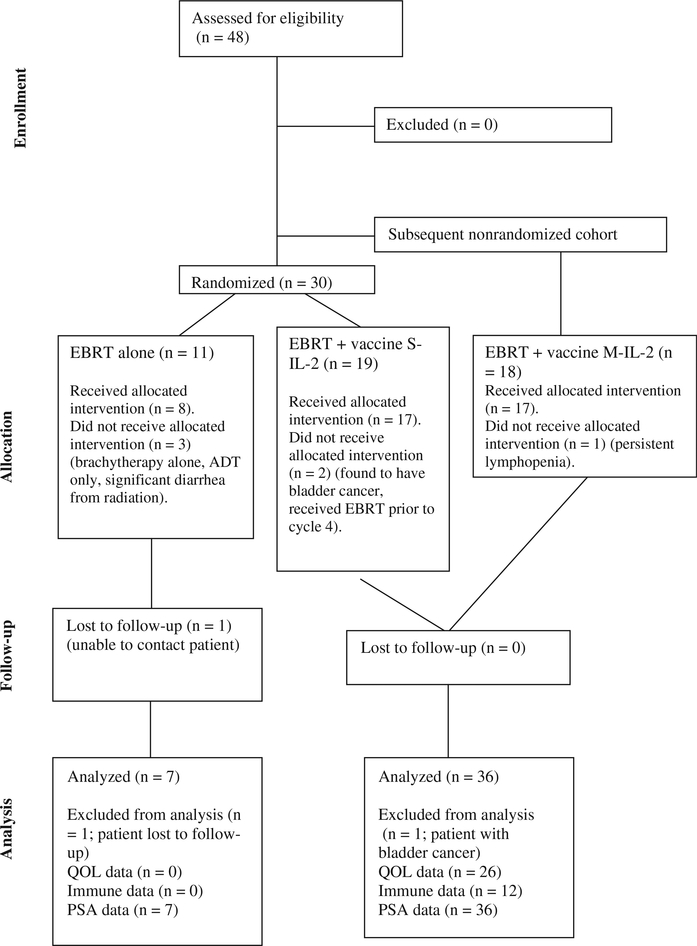

This study enrolled 37 patients for vaccine treatment and 11 for EBRT alone (Figures 1 and 2). Nineteen patients were enrolled in the S-IL-2 arm, 2 of whom did not receive the allocated intervention. One patient was deemed ineligible during pre-radiation evaluation because of a synchronous invasive bladder cancer and was excluded from further analysis; a second patient received EBRT before cycle 4 of vaccine but was included in the analyses. Eighteen patients were enrolled in the M-IL-2 arm, one of whom did not receive the allocated intervention. This patient developed persistent lymphopenia following radiation therapy, which triggered discontinuation of vaccine per protocol but was included in the analysis. In all, 11 patients were enrolled in the EBRT-only arm, 8 of whom received the allocated intervention. Of the three patients on this arm who did not receive the allocated treatment, one was treated with brachytherapy alone, one was treated with ADT alone and one developed significant diarrhea during radiation and could not complete treatment. These three patients were excluded from further analysis as these were felt to have had major deviations from intended therapy. We were unable to contact one patient from the EBRT-alone arm, and this patient was also excluded from further analysis.

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram. ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; M-IL-2, metronomic dose IL-2; QOL, quality of life; S-IL-2, standard dose IL-2.

A total of 26 patients were able to return to the NIH for LTFU. Of the remaining patients, 11 who were contacted by telephone gave permission to have their most recent labs and clinical notes reviewed, and 6 who had passed away had their last clinic follow-up note and PSA on record reviewed.

Patient characteristics for the S-IL-2, M-IL-2 and EBRT-only arms are presented in Table 1. The majority of patients in all three treatment arms were high-risk according to the National Comprehensive Cancer Network risk group stratification criteria. The median EBRT dose was > 70 Gy in all three groups. Over 80% of patients received ADT during their treatment. All patients on study with high-risk disease received ADT. For patients with intermediate-risk disease, 0/4 in the S-IL-2 arm, 4/5 in the M-IL-2 arm and 2/2 in the EBRT-only arm received ADT. As many patients received their ADT outside of the NIH we were unable to obtain the exact details regarding the specific details of the exact start and stop dates of ADT for all patients. As a result of this, additional details regarding hormone treatment has not been included. In all, 3/18 and 5/18 patients in the S-IL-2 and M-IL-2 arms had node-positive disease. Patients could be classified as having node-positive disease based on radiographic findings alone and were not required to have a biopsy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients enrolled on study

| S-IL-2 (n = 18) | M-IL-2 (n = 18) | Placebo (n = 7) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Median (range) | 60 (50 – 78) | 63 (50 – 75) | 67 (60 – 73) | 0.30a |

| Mean (s.d.) | 62 (8.8) | 62 (8.6) | 67 (5.2) | |

| PSA at diagnosis | ||||

| Median (range) | 14.5 (3.8 – 206) | 9.6 (4 – 187) | 8.9 (5.5 – 23) | 0.63a |

| Mean (s.d.) | 38 (54.0) | 28 (46.0) | 11.8 (6.6) | |

| Clinical T stage | ||||

| T1 | 33% | 44% | 43% | 0.63a |

| T2 | 50% | 39% | 14% | |

| T3 | 17% | 17% | 43% | |

| Gleason score | ||||

| 5 | 11% | 0% | 0% | 0.47a |

| 6 | 22% | 22% | 29% | |

| 7 | 28% | 39% | 71% | |

| 8 | 17% | 22% | 0% | |

| 9 | 22% | 17% | 0% | |

| NCCN risk group | ||||

| Low | 17% | 17% | 14% | 0.92a |

| Intermediate | 22% | 28% | 29% | |

| High | 61% | 55% | 57% | |

| Node-positive | 17% | 28% | 0% | 0.34 |

| Received ADT | 83% | 83% | 86% | 1.00 |

| Median EBRT dose Gy (range)b | 73 (68 – 76) | 74 (70 – 76) | 74 (73 – 76.4) | 0.80a |

| Treated with brachytherapy | 0% | 22% | 14% | 0.12 |

Abbreviations: ADT, androgen-deprivation therapy; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; IL, interleukin; M-IL-2, metronomic dose IL-2; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; S-IL-2, standard dose IL-2; T, tumor size.

Compared among groups by Kruskal - Wallis test; others were by Mehta’s modification to Fisher’s exact test.

Excludes four patients treated with EBRT plus high-dose-rate brachytherapy boost.

Clinical results

At a median follow-up of 98 months (range, 16 – 115) for the S-IL-2 group, the actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability was 78%. Median time to failure was 44 months; 4 of these failures were local, 2 were distant and for one patient was not known. Actuarial 5-year overall survival and prostate cancer-specific survival probability were 94% and 94%, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Long-term clinical outcomes of patients

| S-IL-2 | M-IL-2 | Placebo | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median follow-up (range) | 98 m (16 – 115) | 76 m (61 – 86) | 79 m (56 – 86) | |

| Actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability | 78% | 82% | 86% | 0.58 |

| PSA failurea by NCCN risk group | ||||

| Low | 0% (0/2) | 0% (0/3) | 0% (0/1) | 1.00 |

| Intermediate | 20% (1/5) | 0% (0/5) | 0% (0/2) | |

| High | 55% (6/11) | 40% (4/10) | 25% (1/4) | |

| Actuarial 5-year OS probability | 94% | 100% | NA | 0.76 |

| Actuarial 5-year PCSS probability | 94% | 100% | NA | 0.55 |

Abbreviations: IL, interleukin; m, months; M-IL-2, metronomic dose IL-2; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NA, not applicable; OS, overall survival; PCSS, prostate cancer-specific survival; S-IL-2, standard dose IL-2.

Phoenix definition.

At a median follow-up of 76 months (range, 61–86) for the M-IL-2 group, the actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability was 82%. The site of failure was available for only one patient and was distant. Actuarial 5-year overall survival and prostate cancer-specific survival probability were 100% and 100%, respectively.

At a median follow-up of 79 months (range, 56–88) for the EBRT-only group, the actuarial 5-year PSA failure-free probability was 86% and the one failure, at a distant site, occurred at 33 months. The EBRT-only group was not uniformly followed for survival, as this was an exploratory endpoint of the study. Based on available data, however, there was one prostate cancer-related death at 60 months.

There were no significant differences in outcomes between the three groups in regard to PSA failure, prostate cancer-specific survival or overall survival (Table 2).

Late-term toxicity

For the 26 patients who returned to the NIH for LTFU, RTOG late-term toxicity criteria were used to evaluate GI and GU toxicities. Grade ⩾2 GI and GU toxicity was seen in 8% and 19% of patients, respectively (Table 3). Only one patient developed a grade ⩾3 GI/GU toxicity (hemorrhagic cystitis). There were no significant differences between grade ⩾2 GI or GU toxicities between the S-IL-2 and M-IL-2 arms.

Table 3.

RTOG late-term GI/GU toxicities (n = 26)

| Grade | All patients (n = 26) |

S-IL-2 (n = 13) |

M-IL-2 (n = 13) |

P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GU (%) | GI (%) | GU (%) | GI (%) | GU (%) | GI (%) | ||

| 0 | 19 (73) | 17 (65) | 10 (77) | 9 (69) | 9 (69) | 8 (62) | |

| 1 | 2 (8) | 7 (27) | 0 (0) | 2 (15) | 2 (15) | 5 (38) | |

| 2 | 4 (15) | 2 (8) | 2 (15) | 2 (15) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | |

| 3 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 4 | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| ≥2 | 5 (19) | 2 (8) | 3 (23) | 2 (15) | 2 (15) | 0 (0) | GU: 1.00 GI: 0.48 |

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; IL, interleukin; M-IL-2, metronomic dose IL-2; RTOG, Radiation Therapy Oncology Group; S-IL-2, standard dose IL-2.

To further assess late-term toxicities, the 26 patients who returned to the NIH for LTFU completed an EPIC questionnaire. Health-related quality of life scores for urinary, bowel, sexual and hormonal domains (mean ±s.d.) were 88.3±11.6, 85.8±14.0, 41.2±24.7 and 84.6±14.2, respectively (Table 4). There were no differences in domain scores between the S-IL-2 and M-IL-2 arms.

Table 4.

EPIC questionnaire scores

| All patients (n = 26) | S-IL-2 (n = 13) | M-IL-2 (n = 13) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean summary scores (s.d.) | ||||

| Urinary | 88.3 (11.6) | 87.9 (12.7) | 88.7 (10.9) | 0.97 |

| Bowel | 85.8 (14.0) | 82.4 (16.7) | 89.1 (10.1) | 0.51 |

| Sexual | 41.2 (24.7) | 39.9 (22.1) | 42.6 (28.0) | 0.81 |

| Hormonal | 84.6 (14.2) | 83.1 (16.1) | 86.1 (12.6) | 0.60 |

| Domain-specific subscales | ||||

| Urinary Function | 92.4 (12.5) | 91.4 (12.0) | 93.3 (13.4) | 0.33 |

| Bother | 84.2 (13.0) | 84.3 (14.5) | 84.1 (12.0) | 0.71 |

| Incontinence | 87.6 (19.1) | 87.4 (14.3) | 87.8 (23.6) | 0.43 |

| Irritation/obstruction | 88.5 (10.1) | 88.2 (11.7) | 88.7 (8.7) | 0.87 |

| Bowel | ||||

| Function | 86.8 (11.9) | 84.3 (13.5) | 89.3 (10.1) | 0.40 |

| Bother | 84.8 (17.3) | 80.5 (21.2) | 89.0 (11.7) | 0.41 |

| Sexual | ||||

| Function | 30.1 (24.9) | 27.1 (24.8) | 32.8 (25.8) | 0.55 |

| Bother | 53.5 (32.7) | 56.3 (27.8) | 50.5 (38.3) | 0.62 |

| Hormonal | ||||

| Function | 83.1 (15.5) | 82.7 (17.2) | 83.5 (14.3) | 0.99 |

| Bother | 86.2 (15.9) | 83.6 (16.8) | 88.8 (15.2) | 0.27 |

Abbreviations: EPIC, expanded prostate cancer index composite; IL, interleukin; M-IL-2, metronomic dose IL-2; S-IL-2, standard dose IL-2.

A statistical comparison of EPIC values between our LTFU cohort and a cohort treated with EBRT alone12 revealed that the only statistically significant difference between the groups was in the urinary subscales of irritation (P=0.028) and incontinence (P=0.036). Mean irritation and incontinence scores were 84.1 and 85.5, respectively, in the Miller et al. cohort and 88.5 and 87.6, respectively, in the LTFU cohort, suggesting fewer long-term changes in these domains among the LTFU patients.

Immunological studies

Among the patients seen in LTFU, 12 had an HLA-A2 haplotype and were evaluated for PSA-specific immune responses by ELISPOT assay. Of these 12, one patient treated on the M-IL-2 arm had a PSA-specific immune response at 66 months post-enrollment. He was diagnosed at 52 years of age with a PSA of 46, Gleason score of 8 and T3b disease. He was treated with ADT and radiation (75.6 Gy), and developed PSA failure 54 months post-radiation treatment. He did not have a PSA-specific immune response before starting treatment or after receiving three cycles of vaccine.

Previous studies have shown that the combination of radiation therapy and vaccine can induce immunoreactive T cells specific to a broad range of antigens other than PSA in a phenomenon called antigen spreading. We used the ELISPOT assay to look for long-term evidence of antigen spreading by measuring responses to MUC-1, a prostate-associated tumor-associated antigen. The patient described above, who developed a long-term PSA-specific immune response, also developed a T-cell response to MUC-1 seen at 66 months post-enrollment. This patient did not have a MUC-1-specific immune response before starting treatment, but did develop one after three cycles of vaccine.

DISCUSSION

Despite improved outcomes with dose-escalation therapy and ADT, a significant number of patients will experience PSA failure following radiation therapy, and there are currently no therapeutic agents that can enhance treatment for this patient population.

The major cause of death from prostate cancer is metastatic disease. Thus, a significant amount of research has focused on augmenting treatment with systemic therapies. One clinical trial, RTOG 99–02, investigated whether the addition of paclitaxel, etoposide and estramustine to standard radiotherapy and androgen blockade could improve outcomes for men with high-risk prostate cancer. This trial was terminated prematurely when an increased rate of thromboembolic events was reported in the chemotherapy arm.13 A follow-up study, RTOG 05–21, used updated radiation techniques and a chemotherapy regimen of docetaxel and prednisone. Accrual was completed in August 2009 and results are pending.

Studies employing vaccine therapy have shown that this treatment modality may be better tolerated than chemotherapy. The TAX 327 study, for example, demonstrated a statistically significant overall survival benefit with docetaxel and prednisone in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), but 26% of patients given docetaxel every 3 weeks had at least one serious adverse event and 11% had to discontinue treatment because of side effects.14 Improved treatment tolerance was seen in two recent randomized phase II studies of PROSTVAC, a vaccine containing two recombinant viral vectors (vaccinia and fowlpox) and three immune costimulatory molecules. Patients with metastatic CRPC who were treated with PROSTVAC showed an overall survival advantage (median overall survival improvement of 8.5 months associated with a 44% reduction in death rate; P=0.006), with only 1 of 114 patients reporting a serious adverse event possibly related to vaccine. The most frequent side effect was grade 1 injection-site erythema, seen in about 60% of patients.15,16 No significant hematologic or neurologic toxicities or alopecia were noted. These encouraging outcomes have led to a planned phase III clinical trial of PROSTVAC in metastatic CRPC.17

The study reported here used an earlier version of PROSTVAC that included only the costimulatory molecule B7.1 in the priming vaccine and no costimulation in the boost (the current version of this vaccine incorporates three costimulatory molecules in prime and boost). We were able to obtain long-term PSA follow-up on 43/43 patients, long-term toxicity outcomes on 26/43 patients and long-term immunological data on 12/43 patients. Overall PSA failure for the S-IL-2 group was 39%, with 6/7 failures occurring in the high-risk group. Overall failure for the M-IL-2 group was 22%, with all four failures occurring in the high-risk group. The EBRT-only group’s overall PSA failure rate was 14%, with the only noted failure occurring in the high-risk group. Comparisons among the three arms of this study are difficult, given the heterogeneity of the treatment groups and the different lengths of follow-up. Ultimately, the primary endpoint of this study was immunologic. PSA failure and late-term toxicity were only exploratory endpoints. As such, less emphasis was placed on dictating the specifics of treatment and only general guidelines of acceptable treatment standards were required as part of the study.

The wide range of patient eligibility and treatments also makes any direct statistical comparisons between the results of this study and other published studies using radiation with or without ADT difficult. However, it does appear that our results are in line with expected PSA control rates for patients with low-, intermediate- and high-risk disease. Of the low-risk patients in all three arms of this study, 0/6 had a PSA failure. This compares favorably with results from the PROG study, which reported a 5-year probability of avoiding PSA failure of 97% in the 116 low-risk patients treated with 79.2 GyE.3 For our patients with intermediate-risk disease in all three arms, 1/12 (8%) had a PSA failure. Again, this result compares favorably with results from the study conducted by D’Amico et al.18 Of the intermediate-risk patients (75–85%) in the D’Amico study treated with 6 months of ADT therapy, 79% had no biochemical failure at 5 years. Finally, for our patients with high-risk disease, 11/25 (44%) had a PSA failure. This also compares favorably with results from RTOG 92–02, which reported a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 46%. Although direct comparison of study data is difficult, it appears that outcomes in all risk groups in this study combining vaccine and radiation with or without ADT were similar to outcomes reported in major randomized studies.

We used RTOG criteria to evaluate late-term GI/GU toxicity in the 26 patients who returned to the NIH for LTFU. Our findings are similar in magnitude to those reported in major randomized trials that included long-term ADT or dose-escalation therapy with or without neoadjuvant ADT.1 – 3 A weakness of our study was failure to provide consistent grading of GI/GU toxicity during the initial 2 years of follow-up. Lawton et al.19 combined data from RTOG 85–31, 86–10 and 92–02 and found that grade ⩾3 GI toxicity typically occurs in the first 1–3 years post-treatment, while grade ⩾3 GU toxicity develops within 2–5 years. Although our median follow-up is adequate to capture the expected course of late-term GI/GU toxicities, we acknowledge that our results provide a ‘snapshot’ of toxicities at a single time point and may or may not represent the maximum toxicity experienced by each patient. Another drawback of this study was our failure to obtain baseline RTOG GI/GU toxicity scores, leaving us unable to evaluate changes in toxicity scores over time.

In an effort to obtain more detailed information on long-term toxicity, patients who returned to the NIH for LTFU were asked to complete an EPIC questionnaire, a validated, comprehensive instrument designed to evaluate patient function and bother after prostate cancer treatment. We compared our EPIC questionnaire responses with those from a cohort of patients treated with EBRT alone, who had a similar follow-up of 6.2 years.12 The only statistically significant differences between the two groups were in the urinary subscales of irritation (84.1 vs 87.6) and incontinence (85.5 vs 88.5), demonstrating slightly less toxicity in our study. Although these differences in EPIC scores are statistically significant, we believe they are too small to be clinically meaningful. Again, as we did not obtain EPIC questionnaires as part of the original study, we cannot report on changes over time. Also, because no patients treated with EBRT-only returned to the NIH for LTFU, we were unable to compare their EPIC scores with those of patients treated with EBRT plus vaccine.

Only 1 of 12 patients evaluated for PSA-specific immune responses by ELISPOT assay demonstrated a PSA-specific immune response in addition to a response to MUC-1. In the original reports of this study, 18 of 25 HLA-A2-positive patients mounted a PSA-specific immune response within 9 months of starting study.8,9 Thus over time, the level of vaccine-specific immune response appeared to decrease in the majority of patients vaccinated. The patient who maintained his PSA-specific immune response had high-risk disease and developed PSA failure 54 months post-radiation treatment. This result does not allow for conclusions about the predictive and prognostic importance of an immune response, as previously proposed.8,16 Also, while we did not obtain long-term immune data for the EBRT-only group it is important to note that in the initial study no patients treated with EBRT without vaccine developed PSA-specific T-cell responses.8

Preclinically, the addition of multiple costimulatory molecules to poxviral vector-based vaccines has led to marked improvements in vaccine-specific immune responses and antitumor responses.20 – 23 The study reported here employed only one costimulatory molecule in the priming vaccine and none in subsequent boosts. In contrast, the recent randomized phase II trial of 122 patients with CRPC treated with or without PROSTVAC-VF (as mentioned above), which demonstrated an 8.5-month improvement in overall survival (25.1 vs 16.6 months) for patients treated with vaccine, employed three T-cell costimulatory molecules in the priming and all boosting vaccines.15 Whether this newer formulation of the vaccine will improve outcomes when combined with local definitive radiation therapy remains to be seen.

CONCLUSIONS

Our LTFU demonstrated that vaccine combined with radiation therapy with or without ADT leads to similar outcomes in both PSA control or late-term toxicity compared with standard treatments. We also found limited evidence of a long-term immune response following vaccine therapy. We believe the results of our follow-up study are encouraging from clinical and safety standpoints and warrant further investigation.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hanks GE, Pajak TF, Porter A, Grignon D, Brereton H, Venkatesan V et al. Phase III trial of long-term adjuvant androgen deprivation after neoadjuvant hormonal cytoreduction and radiotherapy in locally advanced carcinoma of the prostate: the radiation therapy oncology group protocol 92 – 02. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21: 3972–3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dearnaley DP, Sydes MR, Graham JD, Aird EG, Bottomley D, Cowan RA et al. Escalated-dose versus standard-dose conformal radiotherapy in prostate cancer: first results from the MRC RT01 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2007; 8: 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zietman AL, DeSilvio ML, Slater JD, Rossi CJ Jr, Miller DW, Adams JA et al. Comparison of conventional-dose vs high-dose conformal radiation therapy in clinically localized adenocarcinoma of the prostate: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 294: 1233–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen GW, Howard AR, Jarrard DF, Ritter MA. Management of prostate cancer recurrences after radiation therapy-brachytherapy as a salvage option. Cancer 2007; 110: 1405–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khuntia D, Reddy CA, Mahadevan A, Klein EA, Kupelian PA. Recurrence-free survival rates after external-beam radiotherapy for patients with clinical T1-T3 prostate carcinoma in the prostate-specific antigen era: what should we expect? Cancer 2004; 100: 1283–1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuban DA, Thames HD, Levy LB, Horwitz EM, Kupelian PA, Martinez AA et al. Long-term multi-institutional analysis of stage T1-T2 prostate cancer treated with radiotherapy in the PSA era. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003; 57: 915–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nguyen PL, D’Amico AV, Lee AK, Suh WW. Patient selection, cancer control, and complications after salvage local therapy for postradiation prostate-specific antigen failure: a systematic review of the literature. Cancer 2007; 110: 1417–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Bastian A, Morin S, Marte J, Beetham P et al. Combining a recombinant cancer vaccine with standard definitive radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005; 11: 3353–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lechleider RJ, Arlen PM, Tsang KY, Steinberg SM, Yokokawa J, Cereda V et al. Safety and immunologic response of a viral vaccine to prostate-specific antigen in combination with radiation therapy when metronomic-dose interleukin 2 is used as an adjuvant. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 5284–5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Parker C, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, Panicali D et al. A randomized phase II study of concurrent docetaxel plus vaccine versus vaccine alone in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 1260–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Britten CM, Meyer RG, Kreer T, Drexler I, Wolfel T, Herr W. The use of HLA-A*0201-transfected K562 as standard antigen-presenting cells for CD8(+) T lymphocytes in IFN-gamma ELISPOT assays. J Immunol Methods 2002; 259: 95–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller DC, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Montie JE, Pimentel H, Sandler HM et al. Long-term outcomes among localized prostate cancer survivors: health-related quality-of-life changes after radical prostatectomy, external radiation, and brachytherapy. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23: 2772–2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenthal SA, Bae K, Pienta KJ, Sobczak ML, Asbell SO, Rajan R et al. Phase III multi-institutional trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel, estramustine, and oral etoposide combined with long-term androgen suppression therapy and radiotherapy versus long-term androgen suppression plus radiotherapy alone for high-risk prostate cancer: preliminary toxicity analysis of RTOG 99 – 02. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 73: 672–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 1502–1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, Glode LM, Bilhartz DL, Wyand M et al. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 1099–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Madan RA, Tsang KY, Pazdur MP, Skarupa L et al. Immunologic and prognostic factors associated with overall survival employing a poxviral-based PSA vaccine in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010; 59: 663–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bavarian Nordic Receives Special Protocol Assessment Agreement from the FDA for Phase 3 Trial of PROSTVAC®, 08 December 2010. [cited October 2011]; Available from: http://www.bavarian-nordic.com/investor/announcements/201040.aspx; 2011.

- 18.D’Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 2008; 299: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawton CA, Bae K, Pilepich M, Hanks G, Shipley W. Long-term treatment sequelae after external beam irradiation with or without hormonal manipulation for adenocarcinoma of the prostate: analysis of radiation therapy oncology group studies 85 – 31, 86 – 10, and 92 – 02. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 70: 437–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garnett CT, Greiner JW, Tsang KY, Kudo-Saito C, Grosenbach DW, Chakraborty M et al. TRICOM vector based cancer vaccines. Curr Pharm Des 2006; 12: 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grosenbach DW, Barrientos JC, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Synergy of vaccine strategies to amplify antigen-specific immune responses and antitumor effects. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 4497–4505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hodge JW, Sabzevari H, Yafal AG, Gritz L, Lorenz MG, Schlom J. A triad of costimulatory molecules synergize to amplify T-cell activation. Cancer Res 1999; 59: 5800–5807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S, Hodge JW, Grosenbach DW, Schlom J. Vaccines with enhanced costimulation maintain high avidity memory CTL. J Immunol 2005; 175: 3715–3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]