Abstract

The primary end point of this study was to determine the safety and feasibility of intraprostatic administration of PSA-TRICOM vaccine [encoding transgenes for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and 3 costimulatory molecules] in patients with locally recurrent or progressive prostate cancer. This trial was a standard 3 + 3 dose escalation with 6 patients each in cohorts 4 and 5 to gather more immunologic data. Nineteen of 21 patients enrolled had locally recurrent prostate cancer after definitive radiation therapy, and 2 had no local therapy. All cohorts received initial subcutaneous vaccination with recombinant vaccinia (rV)-PSA-TRICOM and intraprostatic booster vaccinations with recombinant fowlpox (rF)-PSA-TRICOM. Cohorts 3–5 also received intraprostatic rF-GM-CSF. Cohort 5 received additional subcutaneous boosters with rF-PSA-TRICOM and rF-GM-CSF. Patients had pre- and post-treatment prostate biopsies, and analyses of peripheral and intraprostatic immune cells were performed. There were no dose-limiting toxicities, and the maximum tolerated dose was not reached. The most common grade 2 adverse events were fever (38 %) and subcutaneous injection site reactions (33 %); the single grade 3 toxicity was transient fever. Overall, 19 of 21 patients on trial had stable (10) or improved (9) PSA values. There was a marked increase in CD4+ (p = 0.0002) and CD8+ (p = 0.0002) tumor infiltrates in post- versus pre-treatment tumor biopsies. Four of 9 patients evaluated had peripheral immune responses to PSA or NGEP. Intraprostatic administration of PSA-TRICOM is safe and feasible and can generate a significant immunologic response. Improved serum PSA kinetics and intense post-vaccination inflammatory infiltrates were seen in the majority of patients. Clinical trials examining clinical end points are warranted.

Keywords: Cancer vaccine, Immunotherapy, PROSTVAC, Intratumoral vaccine, Prostate cancer

Introduction

PSA-TRICOM (PROSTVAC®) is a prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-targeted poxviral vaccine that has shown preliminary evidence of efficacy in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). This “off-the-shelf” vector vaccine contains the entire PSA transgene, along with an agonist epitope [1] and TRICOM, consisting of the transgenes for 3 T-cell costimulatory molecules (B7.1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3). In a multicenter, randomized phase II trial of 125 patients with mCRPC [2], patients receiving PSA-TRICOM had a 44 % reduction in death rate and an 8.5-month improvement in median overall survival compared to patients given a placebo wild-type vector. A smaller study of PSA-TRICOM with a similar survival showed a trend toward improved overall survival in the patients with the enhanced PSA-specific T-cell immune responses [3]. In the larger phase II trial, the improved survival was seen in patients with mCRPC who had minimal or no symptoms and no prior chemotherapy. Recent data from clinical trials suggest that patients with slow-growing disease and/or low-volume disease with minimal prior exposure to chemotherapy are more likely to have the best outcomes following treatment with therapeutic cancer vaccines [4, 5]. Indeed, patients treated with PSA-TRICOM who had a longer predicted overall survival, as assessed by the Halabi nomogram [6] (consistent with lower disease burden or less aggressive disease), appeared to benefit most from this vaccine and had substantially better outcomes than predicted [3].

At the time of diagnosis of prostate cancer, radiation therapy and surgery are both potentially curative options. Patients who elect to undergo radiation therapy as their definitive up-front treatment and later have a rising PSA have limited options. Salvage radical prostatectomy is rarely done, in part because of significant complications and low curative potential. As a result, there is no clear standard of care for patients with locally recurrent disease following radiation therapy. Hormonal therapies are an option, but are associated with side effects that may affect a patient’s quality of life and have not been shown to improve survival in this setting.

Intraprostatic administration of vaccine may improve the efficacy of prostate cancer therapy, either by direct tumor killing by the vector or by indirect tumor killing through immune-mediated response, both mechanisms having been demonstrated in preclinical studies [7, 8]. In humans, intraprostatic administration of PSA-TRICOM vaccine may increase immune response by converting tumor cells to antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and by creating “danger signals” that allow prostate cancer cells to be recognized as non-self by an activated immune system [9, 10]. Kaufman et al. [11] demonstrated the safety of intratumoral administration of a poxviral TRICOM vaccine in patients with metastatic melanoma. In that study, there was a 38.5 % tumor response rate in the target lesions including one complete response of 22+ months. Two other clinical studies also demonstrated that poxviral vectors could be administered safely into melanoma and via the intravesical route in patients with bladder cancer [12, 13].

The study reported here was based on preclinical studies in which subcutaneous (s.c.) vaccination plus intratumoral vaccination in murine tumors was shown to be superior to either modality alone [14]. The goal of this line of clinical research was to use this strategy in men with localized prostate cancer at high risk of recurrence. However, concerns about the risk/benefit of a phase I trial in patients who were potentially curable led to a trial design enrolling patients with incurable disease at high risk for developing life-threatening disease. As a result, patients were deemed appropriate candidates for standard s.c. and intraprostatic vaccination due to their low tumor burden but high risk for eventual metastatic disease. The goal of the study was to establish that intratumoral administration was safe with the long-term plan to move this strategy into an earlier stage of disease once the risk/benefit is established. Additionally, changes in peripheral T-cell responses were examined by ELISPOT; tumor infiltration by T cells pre- and post-vaccination and changes in serum PSA values were also analyzed.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

Patients enrolled were required to have biopsy-proven, locally recurrent prostate cancer following definitive radiation therapy at least 18 months prior and 3 consecutively rising PSA values with or without androgen deprivation therapy (ADT). Alternatively, patients may have refused, or not been candidates for, definitive local therapy (surgery or radiation), but have clinically progressive disease on ADT. All patients had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–2 and adequate renal, liver, and hematopoietic function. Exclusion criteria included HIV seropositivity, active autoimmune disease, hepatitis B or C positivity, and the use of systemic steroid treatment above physiologic doses. A history of allergy or reaction to prior vaccination with vaccinia virus was contraindicated. Patients had to be able to avoid household contact with children less than 3 years of age, pregnant women, people with open skin wounds, and immunodeficient persons. Patients with serious medical conditions that could interfere with the study treatment program, including class ≥ 2 heart failure, serious pulmonary disease, and active brain metastases, were also excluded.

Study design and treatment

The primary end point of this study was the safety and feasibility of intraprostatic administration of PSA-TRICOM (PROSTVAC®, Bavarian Nordic, Mountain View, CA), a vaccine regimen consisting of a recombinant vaccinia (rV)-PSA-TRICOM priming vaccination and recombinant fowlpox (rF)-PSA-TRICOM booster vaccinations. Vaccines were supplied by the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). Vaccines were prepared as previously described [15] and stored at −70 °C until the day of administration, when they were thawed to room temperature.

Patients were enrolled into 1 of 5 sequential cohorts in a standard 3 + 3 dose-escalation design. Cohorts 4 and 5 each enrolled 6 patients in an effort to gather more data. Patients received s.c. rV-PSA-TRICOM and s.c. rF-GM-CSF, followed by booster vaccinations with intraprostatic rF-PSA-TRICOM, with or without admixed intraprostatic rF-GM-CSF. All patients received the priming vaccination on day 1 and booster vaccinations on days 29, 57, and 85. Patients in cohort 5 received both intraprostatic and s.c. boosters (Table 1). Decisions regarding dose escalation and maximum dose estimation were based on toxicity in the 28 days following the first intraprostatic vaccination of the third subject in all cohorts. Patients completed study on about day 113, unless criteria for study removal were met prior to that point.

Table 1.

Study schematic

| Cohort | Prime (day 1) | Boost (days 29, 57, 85) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| s.c. | Intraprostatic | s.c. | |

| 1 | rV-PSA-TRICOM + rF-GM-CSF | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 107 pfu | |

| 2 | rV-PSA-TRICOM + rF-GM-CSF | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 108 pfu | |

| 3 | rV-PSA-TRICOM + rF-GM-CSF | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 108 pfu | |

| rF-GM-CSF 107 pfu | |||

| 4 | rV-PSA-TRICOM + rF-GM-CSF | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 108 pfu | |

| rF-GM-CSF 108 pfu | |||

| 5 | rV-PSA-TRICOM + rF-GM-CSF | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 108 pfu | rF-PSA-TRICOM 4 × 108 pfu |

| rF-GM-CSF 108 pfu | rF-GM-CSF 107 pfu | ||

s.c. subcutaneous, pfu plaque-forming units

Patients were enrolled into 1 of 5 sequential cohorts. All patients received rV-PSA-TRICOM 2 × 108 pfu with rF-GM-CSF 107 pfu s.c., followed by rF-PSA-TRICOM intraprostatic (2 dose levels) with or without admixed rF-GM-CSF (2 dose levels) intraprostatic

Transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsies were performed prior to initial vaccine and on day 113 with oral quinolone antibiotic prophylaxis. A prostate biopsy that was taken at an outside institution and that indicated locally recurrent disease was acceptable for study enrollment. Vaccine was delivered intraprostatically by a 10-cc syringe loaded with up to 5 cc of vaccine. Each patient was injected at 6 locations via the same transrectal ultrasound-guided approach used for prostate biopsies (right apex, right mid, right base, left apex, left mid, and left base). Each injection site received 0.5–0.8 cc of vaccine. Readily identifiable areas of tumor received an additional 0.5–0.8 cc of vaccine. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the NCI, and all study patients gave written informed consent.

PSA monitoring

PSA values were followed at 28-day intervals. Assessment of PSA response was based on Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group criteria [16]. PSA doubling times (DTs) were determined using the Memorial Sloan-Kettering PSA DT online calculator [17] and were calculated using pre-enrollment PSA values from each patient’s home laboratory and post-enrollment PSA values from the NIH Clinical Center laboratory to ensure consistency in the assessment of PSA values for calculation. Patients who were receiving hormonal therapies that may have affected PSA and PSA DT were enrolled, but these patients were excluded from PSA analyses.

Immunologic monitoring

Peripheral blood assays

Patients underwent leukapheresis prior to the start of treatment and again at study completion (around day 113). Immunologic response was measured by ELISPOT assay to evaluate the production of IFN-γ by T cells after exposure to PSA-3A peptide in both pre- and post-vaccination peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), as previously described [18]. The new gene expressed in prostate (NGEP, also termed “anoctamin-7”, ANO7) peptide was also evaluated in the ELISPOT assay, based on data indicating an antigen cascade with a previous version of this PSA-based vaccine [19]. The T cells were used after 2 in vitro stimulations with the PSA-3A or NGEP peptide. The PSA-3A, NGEP, and HIV peptides were used at a concentration of 25 μg/mL. The presence of anti-PSA antibodies in patient serum pre- and post-vaccination was analyzed by a previously described ELISA [20].

Immunohistochemical analysis of prostate biopsies

Histopathologic features of prostate biopsies from patients enrolled in this clinical trial were analyzed by the NIH Laboratory of Pathology. Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) was performed on 32 biopsy specimens (13 pre-vaccination and 19 post-vaccination). IHC could not be performed on other samples due to inadequate tissue. Most of the inadequate samples were obtained by an outside institution prior to enrollment, which accounts for the discrepancy between the number of samples available pre- and post-vaccination. Seven samples of non-cancerous prostate tissue from 6 age-matched patients were used as controls. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were prepared from prostate core biopsies and then cut into 4-μm-thick sections and stained with anti-CD3, anti-CD4, and anti-CD8, as previously described [21]. Control slides were included in all runs. Negative controls were incubated with mouse IgG1 or IgG2a isotype (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) using similar Ig concentrations as the primary antibody. Tonsil samples were included for positive controls.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

Nineteen of the 21 patients enrolled on study had received definitive local radiation therapy and had biopsy-proven recurrence (Table 2). One patient had metastatic disease at time of diagnosis, was not a candidate for local therapy, and progressed after ADT. Another patient refused any local therapy and progressed after ADT. Median age was 65 (range 55–79). Median Gleason score, based on the highest Gleason score attained on biopsy either at diagnosis or on repeat biopsy for study enrollment, was 8 (range 6–9). Eighteen patients had a Gleason score of ≥7. Nineteen patients had a rising PSA at study entry, with a median PSA DT of 7 months; 16 patients (76 %) had a PSA DT of <12 months. At enrollment, 3 patients had metastatic disease detectable by CT or bone scan. Five patients were castration resistant at the time of study entry, but only 2 of those 5 had known metastatic disease.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Gleason score (median) | 8 (6–9) |

| Age (median in years) | 65 (55–79) |

| PSA DT (median in months) | 7.29 (0.57–negative) |

| <3 months | 4/21 (19.0 %) |

| 3–5 months | 4/21 (19.0 %) |

| 5–12 months | 8/21 (38 %) |

| >12 monthsa | 5/21 (24 %) |

| PSA on study | 4.9 (<0.2–59.4) |

| Previous radiation therapy (RT) treatment | 19/21 (90.5 %) |

| Time since RT (median in years) | 6.9 (3.5–16.2) |

| Castration-sensitive prostate cancer | 16/21 (76.2 %) |

| With metastasis at entry | 1/21 (4.8 %) |

| Without metastasis at entry | 15/21 (71.4 %) |

| Castration-resistant prostate cancer | 5/21 (23.8 %) |

| With metastasis at entry | 2/21 (9.5 %) |

| Without metastasis at entry | 3/21 (14.3 %) |

aAll patients with >12-month PSA DT were castration sensitive and on ADT, including 2 patients with decreasing PSA

ADT androgen deprivation therapy, PSA prostate specific antigen, PSA DT PSA doubling time

Safety

The primary end point of this study was the safety and feasibility of an intraprostatic vaccine strategy for the treatment of prostate cancer (Table 3). Twenty of 21 patients received all planned doses of vaccine, and no patient had vaccine discontinued for toxicity. The maximum tolerated dose was not exceeded. Only one patient had a grade 3 toxicity attributable to vaccine: a transient fever with the second intraprostatic vaccine injection at the highest dose level. The most common toxicity, s.c. injection site reaction, occurred with 47 % of administered s.c. doses, but only 21 % were grade 2. Fever, the second most common toxicity, occurred in 40.2 % of all treatment cycles, though only 14.6 % of all cycles reported grade ≥2 fevers. Fevers generally occurred within hours of receiving intraprostatic vaccine. None was serious enough to require intervention beyond acetaminophen, and all were transient.

Table 3.

Adverse events

| Adverse events | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of patients (%) | # of events (% of cycles) | # of patients (%) | # of events (% of cycles) | |

| Cardiac | ||||

| Hypotension | 2 (9.5) | 2 (2.4) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Constitutional symptoms | ||||

| Fatigue | 2 (9.5) | 2 (2.4) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Fever | 8 (38.1) | 11 (13.4) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2)a |

| Flu-like syndrome | 1 (4.8) | 0 (0) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Dermatology/skin | ||||

| Injection site reaction | 7 (33.3) | 8 (21.1) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Metabolic/laboratory | ||||

| Creatinine | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Potassium, serum high (hyperkalemia) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Renal/GU | ||||

| Obstruction (prostate) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Urinary frequency/urgency | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Urinary retention | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

| Pain (urethra) | 1 (4.8) | 1 (1.2) | 0.0 | 0 |

Percentage of cycles is based on number of events/total 82 cycles, except for injection site reactions, which are based on 38 cycles during which subcutaneous injections were given. There were no > grade 3 toxicities

aA transient fever in patient 21 on day 66 after vaccine administration, which resolved with acetaminophen and levofloxacin

Effect on PSA and PSA DT

Overall, 19 of 21 patients on trial had stable (n = 10) or improved (n = 9) PSA values. However, 7 patients enrolled with castration-naïve prostate cancer (CNPC) and were receiving ADT. Additionally, one patient with CRPC started bicalutamide at the time of study entry. All of these patients were excluded from these analyses because the effect of hormonal therapy could not be separated from that of the vaccine. All of these patients had improved (n = 6) or stable (n = 2) PSA on study. The remaining 13 patients were analyzed: 9 with CNPC and 4 with CRPC. Changes in PSA and PSA DT for those 13 patients are summarized in Table 4. It is also important to note that no patient had anti-PSA antibodies after enrollment, as has been observed in previous clinical trials [2, 18, 19, 22–28], and thus, such antibodies did not influence PSA kinetics after vaccine treatment.

Table 4.

Summary of PSA and PSA DT change by patient and cohort

| Cohort | Pt | Hormone status | PSA Changea | Day 1 | Day 29 | Day 57 | Day 85 | Day 114 | PSA DT Changeb | Pre-PSA DT | Post-PSA DT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | CNPC | Stable | 4.4 | 5.4 | 4.2 | 4.9 | 6.6 | Increase | 4.5 | 9.1 |

| 2 | CNPC | Stable | 5.1 | 5.6 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6 | Increase | 3.39 | 14.16 | |

| 2 | 4 | CNPC | Stable | 22.8 | 22.5 | 28.1 | 28.3 | 26.4 | Increase | 6.94 | 14.91 |

| 5 | CNPC | Improved | 10.6 | 9 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 7.3 | Increase | 11.99 | Neg. | |

| 6 | CNPC | Improved | 2.3 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2 | 1 | Increase | 11.75 | Neg. | |

| 3 | 8 | CNPC | Stable | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | Decrease | 11.28 | 3.83 |

| 4 | 10 | CNPC | Stable | 1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | Decrease | Neg. | 3.11 |

| 11 | CNPC | Improved | 1.7 | 2 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.2 | Increase | 9.24 | Neg. | |

| 15 | CRPC | Worse | 59.4 | 69.6 | 95 | 163.7 | NDc | Decrease | 10.26 | 2.06 | |

| 5 | 16 | CRPC | Stable | 9.1 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.7 | 16.2 | Stable | 4.19 | 4.86 |

| 18 | CRPC | Worse | 17.2 | 16.9 | 27.2 | 30.7 | 45 | Stable | 2.79 | 2.21 | |

| 19 | CNPC | Stable | 6.2 | 6.8 | 9.83 | 7.45 | 7.3 | Decrease | Neg. | 10.41 | |

| 20 | CRPC | Stable | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.79 | 0.79 | 2.9 | Increase | 3.09 | 12.47 |

PSA change defined by Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group criteria

PSA DT change defined by any change from on-study PSA DT using Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center PSA DT calculator. Pre-study PSA and post-study PSA were calculated separately and compared

CNPC castration-naïve prostate cancer, CRPC castration-resistant prostate cancer, PSA prostate-specific antigen, PSA DT PSA doubling time, ND not done, Neg. cannot calculate PSA DT as PSA is decreasing

aChange in PSA from day 1 to day 114

bChange in PSA doubling time

cPatient came off study prior to day 114

PSA

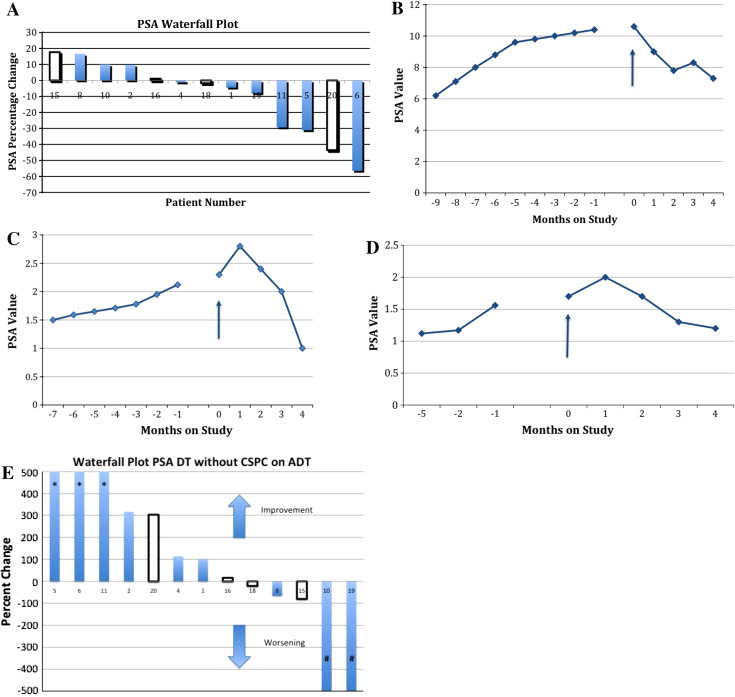

Three patients had improved serum PSA levels, 8 had stable PSA, and 2 patients had increased PSA by Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group criteria. Both patients with increased PSA had CRPC and progressive disease at the time of enrollment. The other 2 patients with CRPC had stable PSA values on study. All patients with CNPC had stable (6) or improved (3) PSA values on study. Figure 1a is a waterfall plot illustrating the best response of each patient by serum PSA values. Figure 1b–d demonstrates 3 patients with improvements in PSA values on study.

Fig. 1.

Prostate-specific antigen results. a Waterfall plot of percentage change in serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), comparing baseline to lowest on-study value. Plot excludes patients who were castration sensitive and on androgen deprivation therapy, as well as one patient with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) who had bicalutamide added to his GnRH agonist at time of enrollment. Filled bars = patients with castration-naïve prostate cancer (CNPC); empty bars = patients with CRPC. b–d Serum PSA trends of 3 patients with CNPC. Arrow start of study treatment. b Patient 5: 30 % decrease in PSA value. c Patient 6: 50 % decrease in PSA value. d Patient 11: 30 % decrease in PSA value. e Waterfall plot comparing percentage change from baseline to end-of-study PSA doubling time (DT). Plot excludes patients who were castration sensitive and on androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), as well as one patient with CRPC who was started on combined androgen blockade at time of enrollment. *Patient’s PSA DT was no longer measurable because PSA was decreasing. #Patient’s PSA was decreasing at enrollment but increased slightly on study. Filled bars = patients with CNPC; empty bars = patients with CRPC

PSA DT

Seven patients had improved PSA DT (>20 % increase) post-vaccine compared with pre-vaccine, 2 patients had stable PSA DT, and 4 patients had worsening PSA DT (>20 % decrease). Figure 1e is a waterfall plot of the percentage change in PSA DT from study entry to study completion.

Immunologic effects

Systemic immunologic effects

Three of 9 HLA-A2-evaluable patients had an increase in PBMC IFN-γ production to PSA peptide, as per ELISPOT assay (see “Patients and methods”, Table 5). Three of 9 patients also developed a T-cell response to another prostate antigen, NGEP peptide, probably due to cross-priming of destroyed tumor cells. This phenomenon has been observed in both preclinical and clinical studies [7, 19]. Overall, 4 of 9 patients evaluated had an increase in PBMC IFN-γ production to either PSA (n = 3) or NGEP (n = 1) peptide.

Table 5.

T-cell-specific response to PSA and NGEP measured by ELISPOT

| Cohort | Pt # | Sample | PSA | NGEP | HIV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 02 | Pre | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 |

| D113 | 1/5,454 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 03 | Pre | <1/60,000 | 1/3,157 | <1/60,000 | |

| D114 | 1/1,818 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 2 | 06 | Pre | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 |

| D121 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 3 | 07 | Pre | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 |

| D123 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 08 | Pre | <1/60,000 | ND | <1/60,000 | |

| D91 | <1/60,000 | ND | <1/60,000 | ||

| 09 | Pre | <1/60,000 | 1/759 | <1/60,000 | |

| D112 | 1/3,529 | 1/750 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 4 | 10 | Pre | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 |

| D106 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 12 | Pre | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | <1/60,000 | |

| D142 | <1/60,000 | 1/2,500 | <1/60,000 | ||

| 5 | 17 | Pre | <1/60,000 | ND | ND |

| D112 | <1/60,000 | ND | ND |

ND not done

ELISPOT response defined as ≥tenfold increase in spots detected, responses are bolded

Immunohistochemical analysis of tumor infiltrate

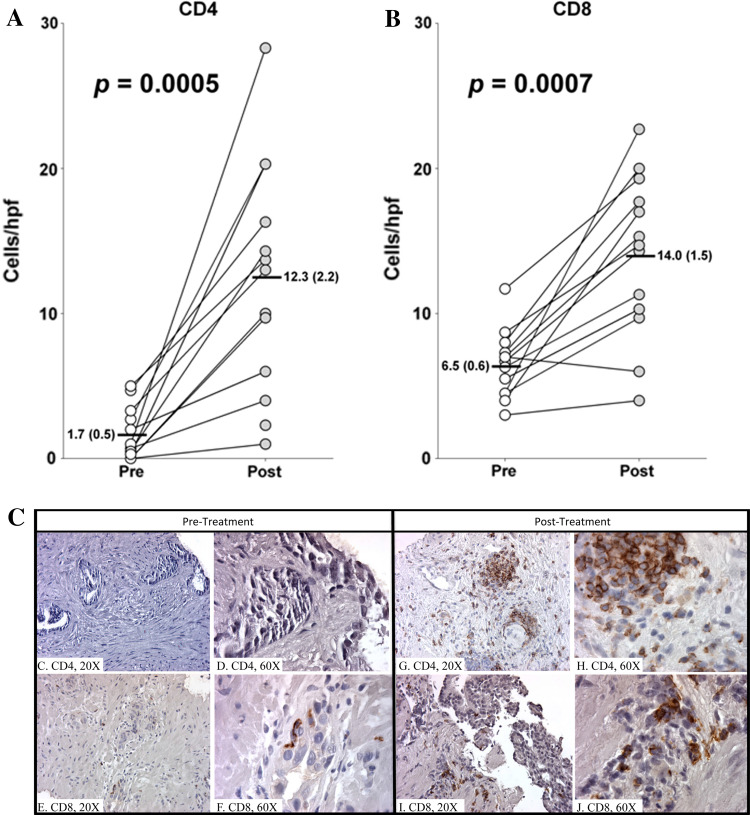

Biopsies obtained from patients pre- and post-vaccination were evaluated for the presence of CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ cells. All patients were biopsied prior to study enrollment; 19 of 21 patients had off-study biopsies. However, 8 patient samples could not be analyzed, primarily because pre-study tissue from biopsies performed outside the NCI was inadequate for IHC evaluation. Tumor infiltrates from 13 patients who were biopsied pre- and post-vaccination were analyzed by paired t-test (Fig. 2a–c). Most notable is the increase in CD4+ and CD8+ cells per high-power field (hpf). CD4+ cells increased from a median of 1.7/hpf pre-vaccination to 12.3/hpf post-vaccination (p = 0.0005, Fig. 2a). Images of representative biopsy samples from one patient pre-vaccine (Fig. 2c, d) and post-vaccine (Fig. 2g, h) clearly demonstrate increased staining for CD4+ in the stroma near tumor cells and within the epithelium post-vaccination. CD8+ cells increased from 6.5/hpf pre-vaccination to 14/hpf post-vaccination (p = 0.0007, Fig. 2b). Images of representative biopsy samples from one patient pre-vaccine (Fig. 2e, f) and post-vaccine (Fig. 2i, j) clearly demonstrate increased staining for CD8+ in the stroma near tumor cells and within the epithelium post-vaccination. The statistically significant difference in the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells pre- and post-vaccination demonstrates a substantial increase in immune infiltrate within the tumor. These findings indicate a robust post-vaccination immune response within the tumor parenchyma.

Fig. 2.

Paired t-test analysis of pre- and post-vaccination numbers of each cell type per high power field (hpf). Three random samples from each patient were stained and counted. Numbers indicate average of those samples. Graphs show median with standard deviation and p values. a CD4+, (b) CD8+. c–j CD4 and CD8 single staining in prostatic core biopsies taken pre- and post-vaccination. Positive cells show brown, membranous staining. Images 2c–d illustrate a pre-treatment biopsy sample stained for CD4+ at low (×20) and high (×60) power, respectively. Images 2e–f illustrate a pre-treatment biopsy sample stained for CD8+ at low (×20) and high (×60) power, respectively. The corresponding post-treatment biopsies are seen to the right. Images 2g, h illustrate a post-treatment biopsy sample stained for CD4+ at low (×20) and high (×60) power, respectively. Images 2i, j illustrate a post-treatment biopsy sample stained for CD8+ at low (×20) and high (×60) power, respectively

Discussion

Recently, interest in therapeutic vaccines for prostate cancer has increased based on data showing enhanced overall survival in randomized studies [2, 5, 29]. Because the poxviral vector in PSA-TRICOM expresses multiple costimulatory molecules, infected cells (including tumor cells) can function as APCs [9, 30]. Introducing these vectors directly into the prostate may induce a therapeutic pro-inflammatory response caused by “danger signals.” Indeed, in previous studies, patients with advanced cancer have been treated with intratumoral injection of poxviral vectors with good safety profile and indications of clinical activity [12, 13], including a poxviral vector encoding TRICOM molecules in advanced melanoma [11].

This study was primarily intended to demonstrate that a poxviral vaccine (PSA-TRICOM) could be safely administered intraprostatically alone and with concurrent subcutaneous administration. Ideally, this trial would have enrolled patients with newly diagnosed prostate cancer, which may have allowed more data to be gathered in a more homogeneous patient population. However, safety concerns needed to be addressed prior to enrolling a patient population for which the benefit/risk ratio of this regimen could not be established. As a result, the trial reported here enrolled patients with locally recurrent prostate cancer. This patient population was considered high enough risk for death from their disease that the potential benefit outweighed the expected risk. However, because this is a difficult patient population to enroll in a clinical trial (because prostate biopsy confirming local recurrence is required), this trial enrolled a rather heterogeneous population including patients with CNPC, castration-sensitive prostate cancer on hormonal therapy, and CRPC. The enrolled population limits the usefulness of the clinical findings on this trial outside of the safety data obtained.

This study showed that intraprostatic injection of PSA-TRICOM was feasible, with only mild toxicities such as transient flu-like symptoms, s.c. injection site reactions, and transient lower urinary tract symptoms. As stated, the other results discussed in this trial are descriptive only, and no conclusions can be drawn about the clinical effectiveness of this strategy. However, it is encouraging that the majority of patients had improved PSA values and/or improved PSA DT while on study, and only 1 patient (with progressive mCRPC prior to enrollment) had progressive disease by PSA on study. Studies of PSA-TRICOM vaccine in patients with mCRPC have described 2 of 129 patients with PSA declines >50 % [2, 24], with minimal change in PSA kinetics during trial [31], despite increases in overall survival. A study of 50 patients with rising PSA following local therapy but no radiographic evidence of metastasis showed a nearly twofold increase in PSA DT following PSA-TRICOM vaccination [25]. These data are consistent with the hypothesis that therapeutic vaccines have maximal impact on outcome when given early in the disease process [32]. Indeed, vaccines may lead not to dramatic decreases in tumor burden, but, as recently demonstrated, to eventual sustained decreases in tumor growth rate [31]. Thus, one way to evaluate these changes is to analyze changes in PSA DT (Fig. 1e).

As evidenced by the presence of both PSA- and NGEP-specific T cells, it is possible that not only PSA-specific T cells were generated. Biopsies obtained 1 month after administration of the last intraprostatic vaccine showed a persistent, robust inflammatory infiltrate in the majority of patients tested. Since the vector in this vaccine directly infects tumor cells, there may be many other tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) besides PSA presented to T cells, and this broader immune response may be more clinically relevant [33]. Other studies suggested improved clinical outcomes in patients who had broader immune responses post-vaccination [34–36]. The inflammatory infiltrate within the tumor could conceivably be due to PSA-specific and other tumor-specific T cells. While only 33 % of patients tested had substantial increases in peripheral PSA-specific T cells (≥tenfold increase), the goal of an effective therapeutic vaccine is to generate a specific T-cell response that can traffic to the tumor (not remain in peripheral circulation). Furthermore, clinical studies have demonstrated higher levels of TAA-specific T cells in tumor than in peripheral blood, leading to the possibility that peripheral immune responses underestimate the true anti-tumor immune response [37]. It should also be noted that the peripheral immune response only is against a 9-amino acid peptide, while the vaccine contains the entire PSA gene (about 244 amino acids).

Whether the dramatically increased immune infiltrates seen following vaccination were vector-specific or tumor-specific, PSA changes consistent with a therapeutic response were nonetheless observed. The majority of the infiltrate appeared to be CD3+, with CD8+ cells having a predilection for areas of epithelial tumor, as expected with a tumor-specific, systemic antitumor immune response. Multiple retrospective studies have demonstrated that an increased number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes convey an improved prognosis in various tumor types [38–43]. However, it is not known whether intervention-induced increase in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes portends an improved prognosis. While it is not known whether the CD4+ cells were tumor-specific, recent preclinical data suggest that tumor-specific CD4+ T cells can prevent tolerance of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells and that tumor-specific CD8+ T cells primed in the presence of activated CD4+ T cells have prolonged effector function against tumors [44].

This study builds on previous preclinical studies [7, 8, 14, 45, 46] and demonstrates the safety and feasibility of this novel therapeutic vaccine approach. Encouraging preliminary results indicating both systemic and tumor-site immune changes were seen in the majority of patients in which samples for analysis were available. Similarly, improvements in PSA kinetics occurred in a majority of patients. It should be emphasized that these results are presented merely for descriptive purposes of data collected and that no conclusions about efficacy can be drawn due to the relatively small number of patients, non-randomized trial design, and the heterogeneity of the patient population sampled. However, we feel that further studies are warranted to determine whether this vaccine strategy can translate into improved clinical outcomes. In particular, this “off-the-shelf” vaccine strategy may be well suited for the neoadjuvant setting in patients with high-risk prostate cancer or as an intervention with minimal adverse effects for patients with low-risk prostate cancer who would otherwise opt for watchful waiting. We are planning such a follow-up study in which s.c. vaccines will be given in the neoadjuvant setting to enable us not only to determine whether intratumoral infiltrates are also associated with s.c. vaccines, but additionally to allow us to have much greater tumor volume to further detail immune responses at the level of the tumor.

Acknowledgments

Grant support was provided by the Intramural Research Program of the Center for Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Benedetto Farsaci and Caroline Jochems for their helpful discussions, Diane J. Poole for her technical assistance, and Bonnie L. Casey and Debra Weingarten for their editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Terasawa H, Tsang KY, Gulley J, Arlen P, Schlom J. Identification and characterization of a human agonist cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitope of human prostate-specific antigen. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantoff PW, Schuetz TJ, Blumenstein BA, Glode LM, Bilhartz DL, Wyand M, Manson K, Panicali DL, Laus R, Schlom J, Dahut WL, Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Godfrey WR. Overall survival analysis of a phase II randomized controlled trial of a Poxviral-based PSA-targeted immunotherapy in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1099–1105. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.0597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Madan RA, Tsang KY, Pazdur MP, Skarupa L, Jones JL, Poole DJ, Higgins JP, Hodge JW, Cereda V, Vergati M, Steinberg SM, Halabi S, Jones E, Chen C, Parnes H, Wright JJ, Dahut WL, Schlom J. Immunologic and prognostic factors associated with overall survival employing a poxviral-based PSA vaccine in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2010;59:663–674. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0782-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madan RA, Gulley JL, Fojo T, Dahut WL. Therapeutic cancer vaccines in prostate cancer: the paradox of improved survival without changes in time to progression. Oncologist. 2010;15:969–975. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Madan RA, Mohebtash M, Schlom J, Gulley JL. Therapeutic vaccines in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: principles in clinical trial design. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:19–28. doi: 10.1517/14712590903321421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halabi S, Small EJ, Kantoff PW, Kattan MW, Kaplan EB, Dawson NA, Levine EG, Blumenstein BA, Vogelzang NJ. Prognostic model for predicting survival in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1232–1237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kudo-Saito C, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Induction of an antigen cascade by diversified subcutaneous/intratumoral vaccination is associated with antitumor responses. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2416–2426. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Slavin-Chiorini DC, Catalfamo M, Kudo-Saito C, Hodge JW, Schlom J, Sabzevari H. Amplification of the lytic potential of effector/memory CD8 + cells by vector-based enhancement of ICAM-1 (CD54) in target cells: implications for intratumoral vaccine therapy. Cancer Gene Ther. 2004;11:665–680. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodge JW, Abrams S, Schlom J, Kantor JA. Induction of antitumor immunity by recombinant vaccinia viruses expressing B7–1 or B7–2 costimulatory molecules. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5552–5555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matzinger P. The danger model: a renewed sense of self. Science. 2002;296:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1071059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufman HL, Cohen S, Cheung K, DeRaffele G, Mitcham J, Moroziewicz D, Schlom J, Hesdorffer C. Local delivery of vaccinia virus expressing multiple costimulatory molecules for the treatment of established tumors. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:239–244. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomella LG, Mastrangelo MJ, McCue PA, Maguire HJ, Mulholland SG, Lattime EC. Phase I study of intravesical vaccinia virus as a vector for gene therapy of bladder cancer. J Urol. 2001;166:1291–1295. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)65755-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mastrangelo MJ, Maguire HC, Jr, Eisenlohr LC, Laughlin CE, Monken CE, McCue PA, Kovatich AJ, Lattime EC. Intratumoral recombinant GM-CSF-encoding virus as gene therapy in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Cancer Gene Ther. 1999;6:409–422. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7700066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kudo-Saito C, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Intratumoral vaccination and diversified subcutaneous/intratumoral vaccination with recombinant poxviruses encoding a tumor antigen and multiple costimulatory molecules. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1090–1099. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall JL, Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Beetham PK, Tsang KY, Slack R, Hodge JW, Doren S, Grosenbach DW, Hwang J, Fox E, Odogwu L, Park S, Panicali D, Schlom J. Phase I study of sequential vaccinations with fowlpox-CEA(6D)-TRICOM alone and sequentially with vaccinia-CEA(6D)-TRICOM, with and without granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, in patients with carcinoembryonic antigen-expressing carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:720–731. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.10.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, Morris M, Sternberg CN, Carducci MA, Eisenberger MA, Higano C, Bubley GJ, Dreicer R, Petrylak D, Kantoff P, Basch E, Kelly WK, Figg WD, Small EJ, Beer TM, Wilding G, Martin A, Hussain M. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148–1159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Prediction Tools: Prostate Cancer Nomograms. http://nomograms.mskcc.org/Prostate/PsaDoublingTime.aspx. Accessed Dec 2012

- 18.Gulley J, Chen AP, Dahut W, Arlen PM, Bastian A, Steinberg SM, Tsang K, Panicali D, Poole D, Schlom J, Michael Hamilton J. Phase I study of a vaccine using recombinant vaccinia virus expressing PSA (rV-PSA) in patients with metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Prostate. 2002;53:109–117. doi: 10.1002/pros.10130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulley JL, Arlen PM, Bastian A, Morin S, Marte J, Beetham P, Tsang KY, Yokokawa J, Hodge JW, Menard C, Camphausen K, Coleman CN, Sullivan F, Steinberg SM, Schlom J, Dahut W. Combining a recombinant cancer vaccine with standard definitive radiotherapy in patients with localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3353–3362. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Madan RA, Mohebtash M, Arlen PM, Vergati M, Rauckhorst M, Steinberg SM, Tsang KY, Poole DJ, Parnes HL, Wright JJ, Dahut WL, Schlom J, Gulley JL. Ipilimumab and a poxviral vaccine targeting prostate-specific antigen in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:501–508. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mannon PJ, Leon F, Fuss IJ, Walter BA, Begnami M, Quezado M, Yang Z, Yi C, Groden C, Friend J, Hornung RL, Brown M, Gurprasad S, Kelsall B, Strober W. Successful granulocyte-colony stimulating factor treatment of Crohn’s disease is associated with the appearance of circulating interleukin-10-producing T cells and increased lamina propria plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:447–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Parker C, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, Panicali D, Beetham P, Tsang KY, Grosenbach DW, Feldman J, Steinberg SM, Jones E, Chen C, Marte J, Schlom J, Dahut W. A randomized phase II study of concurrent docetaxel plus vaccine versus vaccine alone in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1260–1269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arlen PM, Gulley JL, Todd N, Lieberman R, Steinberg SM, Morin S, Bastian A, Marte J, Tsang KY, Beetham P, Grosenbach DW, Schlom J, Dahut W. Antiandrogen, vaccine and combination therapy in patients with nonmetastatic hormone refractory prostate cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:539–546. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000165159.33772.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arlen PM, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, Seetharam M, Tsang KY, Grosenbach DW, Feldman J, Poole DJ, Litzinger M, Steinberg SM, Jones E, Chen C, Marte J, Parnes H, Wright J, Dahut W, Schlom J, Gulley JL. Clinical safety of a viral vector based prostate cancer vaccine strategy. J Urol. 2007;178:1515–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiPaola R, Chen Y, Bubley G, Hahn N, Stein M, Schlom J, Gulley J, Lattime E, Carducci M, Wilding G (2009) A phase II study of PROSTVAC-V (vaccinia)/TRICOM and PROSTVAC-F (fowlpox)/TRICOM with GM-CSF in patients with PSA progression after local therapy for prostate cancer: results of ECOG 9802. ASCO Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. Abstr 108. http://meetinglibrary.asco.org/content/20355-64

- 26.DiPaola RS, Plante M, Kaufman H, Petrylak DP, Israeli R, Lattime E, Manson K, Schuetz T. A phase I trial of pox PSA vaccines (PROSTVAC-VF) with B7–1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 co-stimulatory molecules (TRICOM) in patients with prostate cancer. J Transl Med. 2006;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eder JP, Kantoff PW, Roper K, Xu GX, Bubley GJ, Boyden J, Gritz L, Mazzara G, Oh WK, Arlen P, Tsang KY, Panicali D, Schlom J, Kufe DW. A phase I trial of a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing prostate-specific antigen in advanced prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1632–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaufman HL, Wang W, Manola J, DiPaola RS, Ko YJ, Sweeney C, Whiteside TL, Schlom J, Wilding G, Weiner LM. Phase II randomized study of vaccine treatment of advanced prostate cancer (E7897): a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2122–2132. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, Berger ER, Small EJ, Penson DF, Redfern CH, Ferrari AC, Dreicer R, Sims RB, Xu Y, Frohlich MW, Schellhammer PF. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Litzinger MT, Foon KA, Sabzevari H, Tsang KY, Schlom J, Palena C. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells genetically modified to express B7–1, ICAM-1, and LFA-3 confer APC capacity to T cells from CLL patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58:955–965. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0611-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein WD, Gulley JL, Schlom J, Madan RA, Dahut W, Figg WD, Ning YM, Arlen PM, Price D, Bates SE, Fojo T. Tumor regression and growth rates determined in five intramural NCI prostate cancer trials: the growth rate constant as an indicator of therapeutic efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:907–917. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulley JL, Madan RA, Schlom J. Impact of tumour volume on the potential efficacy of therapeutic vaccines. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:e150–e157. doi: 10.3747/co.v18i3.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gulley JL. Therapeutic vaccines: the ultimate personalized therapy? Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9:219–221. doi: 10.4161/hv.22106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Disis ML, Wallace DR, Gooley TA, Dang Y, Slota M, Lu H, Coveler AL, Childs JS, Higgins DM, Fintak PA, dela Rosa C, Tietje K, Link J, Waisman J, Salazar LG. Concurrent trastuzumab and HER2/neu-specific vaccination in patients with metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4685–4692. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hardwick N, Chain B. Epitope spreading contributes to effective immunotherapy in metastatic melanoma patients. Immunotherapy. 2011;3:731–733. doi: 10.2217/imt.11.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A, Zdrojowy R, Pluzanska A, Szczylik C, Staehler M, Brugger W, Dietrich PY, Mendrzyk R, Hilf N, Schoor O, Fritsche J, Mahr A, Maurer D, Vass V, Trautwein C, Lewandrowski P, Flohr C, Pohla H, Stanczak JJ, Bronte V, Mandruzzato S, Biedermann T, Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Yamagishi H, Miki T, Hongo F, Takaha N, Hirakawa K, Tanaka H, Stevanovic S, Frisch J, Mayer-Mokler A, Kirner A, Rammensee HG, Reinhardt C, Singh-Jasuja H (2012) Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med doi:10.1038/nm.2883 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Romero P, Dunbar PR, Valmori D, Pittet M, Ogg GS, Rimoldi D, Chen JL, Lienard D, Cerottini JC, Cerundolo V. Ex vivo staining of metastatic lymph nodes by class I major histocompatibility complex tetramers reveals high numbers of antigen-experienced tumor-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1641–1650. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.9.1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clemente CG, Mihm MC, Jr, Bufalino R, Zurrida S, Collini P, Cascinelli N. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer. 1996;77:1303–1310. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1303::AID-CNCR12>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dieu-Nosjean MC, Antoine M, Danel C, Heudes D, Wislez M, Poulot V, Rabbe N, Laurans L, Tartour E, de Chaisemartin L, Lebecque S, Fridman WH, Cadranel J. Long-term survival for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with intratumoral lymphoid structures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4410–4417. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao Q, Qiu SJ, Fan J, Zhou J, Wang XY, Xiao YS, Xu Y, Li YW, Tang ZY. Intratumoral balance of regulatory and cytotoxic T cells is associated with prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2586–2593. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.4565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hiraoka K, Miyamoto M, Cho Y, Suzuoki M, Oshikiri T, Nakakubo Y, Itoh T, Ohbuchi T, Kondo S, Katoh H. Concurrent infiltration by CD8 + T cells and CD4 + T cells is a favourable prognostic factor in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:275–280. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naito Y, Saito K, Shiiba K, Ohuchi A, Saigenji K, Nagura H, Ohtani H. CD8 + T cells infiltrated within cancer cell nests as a prognostic factor in human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3491–3494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma P, Shen Y, Wen S, Yamada S, Jungbluth AA, Gnjatic S, Bajorin DF, Reuter VE, Herr H, Old LJ, Sato E. CD8 tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are predictive of survival in muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:3967–3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611618104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shafer-Weaver KA, Watkins SK, Anderson MJ, Draper LJ, Malyguine A, Alvord WG, Greenberg NM, Hurwitz AA. Immunity to murine prostatic tumors: continuous provision of T-cell help prevents CD8 T-cell tolerance and activates tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6256–6264. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 45.Kudo-Saito C, Garnett CT, Wansley EK, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Intratumoral delivery of vector mediated IL-2 in combination with vaccine results in enhanced T cell avidity and anti-tumor activity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:1897–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0332-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kudo-Saito C, Wansley EK, Gruys ME, Wiltrout R, Schlom J, Hodge JW. Combination therapy of an orthotopic renal cell carcinoma model using intratumoral vector-mediated costimulation and systemic interleukin-2. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1936–1946. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]