Abstract

We successfully synthesized 3D supramolecular structure of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) complex, (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], in almost a quantitative yield by using metathesis and ligand addition reactions. The new complex was characterized by various techniques such as FTIR, UV-Visible, PXRD, SXRD, and CV electrochemical analysis to investigate mainly its structure. Based on the results of these techniques, the formation of the desired complex was confirmed. The TGA for this complex indicated the utilization of this complex as a single-source precursor for the synthesis of cobalt sulfide (CoS) under helium atmosphere and tricobalt tetraoxide (Co3O4) under air. Investigation of pyrolysis products by PXRD proved the formation of CoS and Co3O4. Furthermore, morphology studies by SEM and TEM displayed the formation of CoS and Co3O4 nanoparticles with various shapes.

Keywords: Inorganic chemistry, Organic chemistry, Materials chemistry

1. Introduction

Recently, we reported on the synthesis and crystal structure of cyclohexylammonium thiocyanate (C6H11NH3+SCN−, HCHA+SCN−), as a potential precursor for preparing new compounds [1]. Thiocyanate ion is a bidentate ligand which has several terminal and bridging coordination modes, making it capable of forming numerous useful neutral and anionic metal complexes [2]. For instance, tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) anion, [Co(NCS)4]2-, has been extensively studied and used as a building block for the synthesis of 1D, 2D and 3D supramolecular structures. Furthermore, it has the ability to form weak van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) anion has been used in the analytical chemistry for spectrophotometric determination of small amount of cobalt after extracting [Co(NCS)4]2- with different kinds of cations such as 2,4-dichlorobenzyltriphenylphosphonium [10], tetramethylene-bis(triphenylphosphonium) [11], triphenylsulphonium [12], and brilliant green [13]. Moreover, small amount of cobalt can be determined spectrophotometrically after liquid-liquid extraction with triisooctylamine [14] or propylene carbonate [15]. In another indirect process, [Co(NCS)4]2- has been used to determine beryllium [16], quaternary ammonium-based surfactants [17], and diphenyliodonium [18]. In another application, [Co(NCS)4]2- has been used to prepare gel-embedded cobalt nanoparticles [19]. Thermochromism phenomenon has also been noticed in the [Co(NCS)4]2- complex on dissolving the neutral complex of cobalt isothiocyanate, Co(NCS)2, in the ionic liquid (1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium) thiocyanate, where the coordination structure changed from tetrahedral [Co(NCS)4]2− at ∼25 °C to octahedral [Co(NCS)6]4− by cooling below -40 °C [20].

Cyclohexylammonium, HCHA+, is also a useful building block for constructing supramolecular structures with various dimensionalities via hydrogen bonding. For example, cyclohexylammonium terephthalate forms a 2D network [21], while cyclohexylammonium salt of nitrate [22] and thiocyanate [1] form 3D networks.

Herein, we report the preparation, crystal structure, and characterization of 3D supramolecular structure of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4], which was utilized as a single-source precursor, through its thermal decomposition, for the synthesis of cobalt sulfide (CoS) and tricobalt tetraoxide (Co3O4) nanoparticles. Cobalt sulfide finds widespread applications such as electrochemical conductivity [23, 24], electrochemical water splitting with photo anodes [25, 26], and supercapacitors with enhanced charge capacity and stability [27, 28]. On the other hand, tricobalt tetraoxide (Co3O4) has been reported for use in supercapacitors, magnetic semiconductors [29, 30, 31], photocatalysis [32, 33], carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrocarbon oxidations, and other catalysis applications [34, 35, 36, 37, 38].

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Cyclohexylamine (98+%, Alfa Aesar), cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (p.a, 99%, POCH), sodium thiocyanate (ACS, 98.0%, Alfa Aesar), ethanol (absolute 99.9%, Petrochem), and chloroform (analytical reagent, BDH) were commercially available and were used without further purification.

2.2. Analytical and physical techniques

The chemical composition was confirmed by CHNS elemental microanalysis using a Perkin Elmer Series II CHNS/O analyzer and by cobalt metal analysis using an Agilent 700 series inductively-coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES). Diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform (DRIFT) spectra of powder samples, diluted with IR-grade potassium bromide (KBr), were recorded on a Perkin Elmer FTIR system spectrum GX in the range of 400–4000 cm−1. Liquid-state ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorbance spectra were recorded on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 950 UV/Vis/NIR spectrophotometer. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer, operated at 40 mA and 40 kV by using CuKα radiation and a nickel filter, in the 2-theta range from 1 to 80° in steps of 0.01°, with a sampling time of 0.2 second per step. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD) was recorded on a Bruker D8 diffractometer equipped with a PHOTON100 CMOS detector operated in shutterless mode. The morphology was studied by using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM model: FEI-200NNL), equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectrometer for elemental analysis, and by using a high resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM model: JEM-2100F JEOL). Carbon-coated copper grids were used for mounting the samples for HRTEM analysis. Thermal stability was investigated by thermal gravimetric analyzer (TGA Q50 TA instrument-ThermoStar Gas Analysis System Pfeiffer Vacuum). Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller surface areas (BET-SA) and pore size distribution of the catalysts were obtained on Micrometrics Gemini III-2375 (Norcross, GA, USA) instrument by N2 physisorption at 77 K. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) of the HCHA+NCS− salt and (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] complex was performed to determine the redox potentials of the Co–complex using a conventional three electrode system with a glassy carbon (GC) electrode, casted with the ligand or Co-complex slurry in 1 % nafion solution, as a working electrode, Pt-wire as an auxiliary electrode and Ag/AgCl/3M KCl as a reference electrode. A Metrorohm PGSTAT101 μ-Autolab was used for electrochemical studies.

2.3. Synthesis of cyclohexylammonium thiocyanate (HCHA+SCN−)

This compound was prepared according to our procedure published previously [1] by salt metathesis reaction between cyclohexylammonium chloride and sodium thiocyanate.

2.4. Synthesis of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]

A two-step procedure reaction was used to synthesize this compound. The first step was to synthesize the neutral complex of cobalt(II) isothiocynate in ethanol medium from the reaction between sodium thiocyanate and cobalt nitrate hexahydrate, where the precipitation of sodium nitrate is the driving force for the reaction, as illustrated in Eq. (1):

Equation 1:

| (1) |

After filtering off the precipitate, the second step was performed by reacting the ethanolic solution of cobalt(II) isothiocyanate with HCHA+SCN−, where a navy blue solution was formed, as shown in Eq. (2):

Equation 2:

| (2) |

Navy blue small, needle crystals were obtained through the evaporation of ethanol at room temperature over a period of 7 days. Beautiful orthorhombic crystals of this new complex were obtained by recrystallization in chloroform at room temperature with a yield of ∼100%.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Elemental analysis

The results of elemental analysis as shown in Table 1, confirmed the chemical composition of our target compound and indicated the successfulness of our synthetic procedure approach.

Table 1.

The elemental analysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4].

| Element | Theoretical (wt/wt%) | Experimental (wt/wt%) |

|---|---|---|

| C | 39.09 | 40.27 |

| H | 5.74 | 6.02 |

| N | 17.09 | 16.31 |

| S | 26.09 | 25.07 |

| Co | 11.99 | 12.01 |

3.2. FT-IR spectrophotometry

Fig. 1 displays the DRIFT spectrum of the (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4], confirming the success of our method for synthesizing the desired compound. Three characteristic vibrations verify the presence of thiocyanate ligand and its binding mode to the Co(II) ion centre for the formation of the anionic complex [Co(NCS)4].

Fig. 1.

FTIR spectrum of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4].

The strong bands at 2096 and 2073 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching vibration of C≡N bond of thiocyanate ligand. The weak bands at 849 and 826 cm−1 can be attributed to C−S bond stretching vibration. The weak band at 483 cm−1 can be ascribed to the bending vibration of N−C−S. This bending vibration of thiocyanate indicates the binding of thiocyanate ligand to Co(II) center via its N-terminal. The assignment of these bands to thiocyanate vibrations and deduction of its coordination mode are based on the previously reported results [5, 7, 19, 20]. The spectrum also shows the characteristic vibrations for cyclohexylammonium cation, C6H11NH3+ (HCHA+). The strong bands at 3190-3098 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching vibration of NH3+ bond of cyclohexaylammonium cation. The medium band at 2944 cm−1 with shoulder at 2907 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching vibrations of CH2. The strong band at 2865 cm−1 can be attributed to the stretching vibration of C−H bond. The strong band at 1595 cm−1 can be ascribed to the NH3 scissoring. The strong band at 1477cm−1 with two shoulders at 1470 and 1456 cm−1 can be assigned to the CH2 deforming. The weak band at 1386 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching vibration of C−H bond. The weak bands at 1284, 1264, and 1228 cm−1can be attributed to the CH2 wagging, followed by a band at 1172 cm−1, which is related to the ring deformation. The weak bands at 1121, 1085, 1062 cm−1 can be assigned to the CH2 twisting. The medium band at 1001 cm−1 can be ascribed to the bending vibration of C−N bond. The weak band at 952 cm−1 can be attributed to the ring breathing. The weak band at 923 cm−1 can be ascribed to the NH3 twisting, followed by a weak band at 889 cm−1, which is related to the ring deformation. The weak bands at 871, 784, and 550 cm−1 can be assigned to the CH2 rocking. The strong bands at 452 and 411 cm−1 can be attributed to the ring C−N bending [39].

3.3. UV-Vis spectrophotometry

Fig. 2 shows the absorbance spectrum in the visible region for (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]. The strong, broad band with maximum absorbance at 622 nm and a shoulder with maximum absorbance at 589 nm are characteristic features for the tetrahedral, blue tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) complex. The absorbance at 622 nm corresponds to the 4A2 → 4T2 transition while the absorbance at 589 nm is for 4A2 → 4T1(F) transition [5, 6, 7, 19, 20, 40]. This electronic spectrum is in agreement with the FT-IR spectrum, confirming the binding of thiocyanate ligand through its N-terminal to the Co(II) center and the formation of the tetrahedral [Co(NCS)4]2-.

Fig. 2.

Absorbance spectrum of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4].

3.4. X-ray diffraction

3.4.1. SXRD of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]

The crystal structure of (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4] was determined by SXRD, confirming the FTIR and UV-Vis spectroscopic results. The summary of the crystallographic data is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the crystallographic parameters of the structure determination for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4].

| Crystal Structure Data | |

|---|---|

| Empirical Formula | C16H28CoN6S4 |

| Formula weight | 491.61 |

| Crystal System | Orthorhombic |

| Space group | Pbcm (No. 57) |

| a (Å) | 11.4808 |

| b (Å) | 8.5881 (3) |

| c (Å) | 24.4244 (8) |

| α (°) | 90 |

| β (°) | 90 |

| γ (°) | 90 |

| Volume (Å3) | 2408.20 (14) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcal (g/cm3) | 1.356 |

| μ (mm−1) | 8.932 |

| F(000) | 1028 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.05 × 0.05 × 0.12 |

| Cu Kα radiation (Å) | 1.54178 |

| T (°C) | -143.15 |

| 2θ range (°) | 3.6 to 74.6 |

| Reflections collected | 43418 |

| Unique reflections | 2601 |

| Rint | 0.072 |

| Data; Parameters | 2346; 146 |

| Goodness-of-fit | 1.05 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ(I)] |

R(F) = 0.0473 wR(F2) = 0.1368 |

| Δρmax; Δρmin (e/Å3) | 0.76; −0.72 |

| CCDC No. | 1859673 |

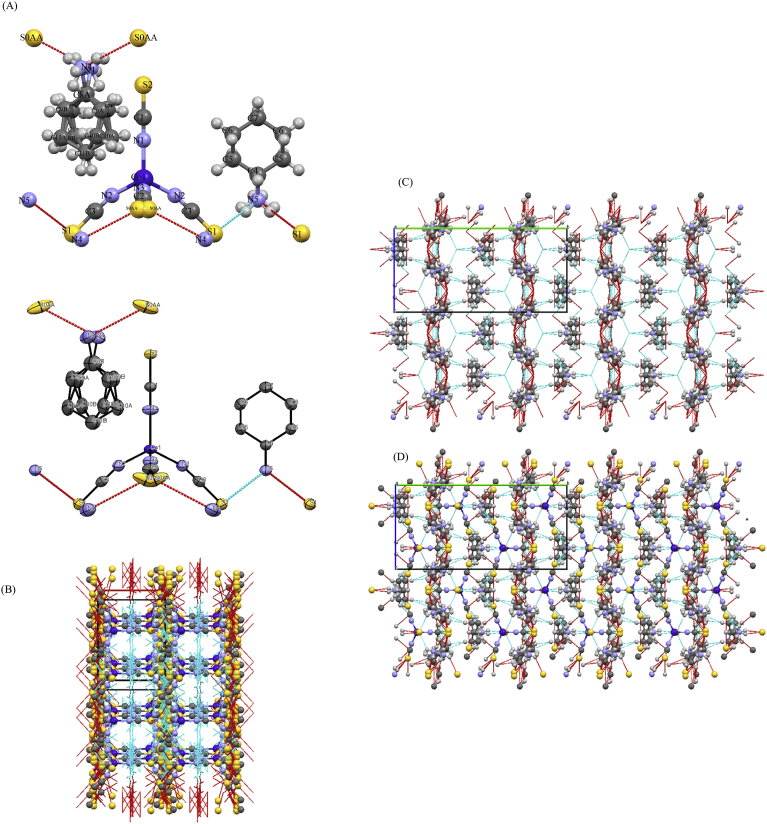

Fig. 3A, shows the asymmetric molecule of (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4]. The central Co2+ ion of [Co(NCS)4]2- is coordinated to four isothiocyanate ligands via their N-terminal and resides in a distorted tetrahedral environment, as evidenced from deviation of the bond angles values from the standard value of 109.5° of symmetrical tetrahedral. Selected data of the bond angles (°) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) is presented in Table 3 (see Supplementary Material, Table S4 for the remain bond angles). The angle between central Co2+ ion, the nitrogen and the carbon of bonded isothiocyanate ligand (Co−N−C link) is deviated from 180°, i.e. not linear angle, except the Co1−N1−C1 and Co1−N3−C2 angles are very close to the linear angle. Such structural feature of [Co(NCS)4]2- has been reported in literature [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. Furthermore, the isothiocyanate ligand is almost linear, as it is expected. However, one of the isothiocyanate ligand is disordered in its C−S bond (Fig. 3A). The Co−N bond length ranges between 1.956 Å and 1.964 Å with an average of 1.958 Å. Selected data for the bond distances (Å) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), are presented in Table 4 which is similar to what has been reported previously [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9] (see Supplementary Material, Table S6 for remaining bond lengths). The C≡N bond length ranges between 1.127 Å and 1.165 Å with an average of 1.153 Å (Table 4). This observed bond length for C≡N is comparable to the reported value in literature [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9]. The bond length of C−S in the range of 1.625–1.643 Å with an average of 1.631 Å, which is in agreement with the previously reported value [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9]. The cyclohexylammonium counterion (containing N4, C8, C9, C10, and C11 atoms) is highly disordered, as reflected by the large deviation of most of its angles from 109.5°, while the other cyclohexylammonium counterion (containing N5, C4, C5, C6, and C7 atoms) has its angles close to 109.5° except those angles between the disordered ammonium protons (Fig. 3A, and Table 3). The observed disorder in cyclohexylammonium counterions in the structure of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] was not detected in the structures of cyclohexylammonium thiocynate [1] and nitrate [22]. The length of the bonds in both of cyclohexylammonium counterions are close to those reported for cyclohexylammonium in its salt with thiocyanate [1] and nitrate [22].

Fig. 3.

The ORTEP and ball and stick representations of the ionic complex cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4]. (A) Asymmetric molecule of (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], viewed along the b-axis, showing the coordination sphere of the Co2+ ion in distorted tetrahedral environment. (B) Array of layers of [Co(NCS)4]2- ions, viewed along the c-axis, rotated -90°on the a-axis, and then tilted forward. (C) Array of layers of (C6H11NH3)+ ions, viewed along a-axis. (D) Crystal packing of (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4] viewed along the a-axis. Color code: navy blue, cobalt; light blue, nitrogen; grey, carbon; yellow, sulfur; white, hydrogen.

Table 3.

Selected bond angles (degrees) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], R = 0.05.

| N1 | -Co1 | -N2 | 114.39(9) | C9A | -C8B | -C9B | 18.8(4) |

| N1 | -Co1 | -N3 | 108.20(15) | C8A | -C9A | -C10B | 116.6(6) |

| N1 | -Co1 | -N2_a | 114.39(9) | C8B | -C9A | -C9B | 70.7(12) |

| N2 | -Co1 | -N3 | 105.51(10) | C8A | -C9A | -C10A | 112.4(6) |

| N2 | -Co1 | -N2_a | 108.12(11) | C8B | -C9A | -C10B | 116.6(6) |

| N2a | -Co1 | -N3 | 105.51(10) | C9B | -C9A | -C10A | 68.5(12) |

| Co1 | -N1 | -C1 | 172.6(3) | C8B | -C9A | -C10A | 112.4(6) |

| Co1 | -N2 | -C3 | 158.9(3) | C8A | -C9A | -C9B | 70.7(12) |

| Co1 | -N3 | -C2 | 178.5(4) | C9B | -C9A | -C10B | 101.8(14) |

| S2 | -C1 | -N1 | 179.9(4) | C10A | -C9A | -C10B | 34.9(5) |

| S0AA | -C2 | -N3 | 171.4(3) | C8A | -C9B | -C9A | 90.5(12) |

| S0AA | -C2 | -S0AA_a | 17.2(4) | C8A | -C9B | -C10A | 124.8(7) |

| S0AAa | -C2 | -N3 | 171.4(3) | C8A | -C9B | -C10B | 110.9(6) |

| S1 | -C3 | -N2 | 178.4(3) | C8B | -C9B | -C9A | 90.5(12) |

Table 4.

Selected bond distances (Å) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], R = 0.05.

| Co1 | -N1 | 1.957 (4) | C10B | -C11A | 1.496 (8) |

| Co1 | -N2 | 1.956 (2) | C10B | -C11B | 1.496 (8) |

| Co1 | -N3 | 1.964 (4) | N5 | -C4 | 1.501 (5) |

| Co1 | -N2_a | 1.956 (2) | C8A | -H8A | 1.0000 |

| S1 | -C3 | 1.625 (4) | C8A | -H8B | 1.0000 |

| S0AA | -C2 | 1.643 (5) | C8B | -H8B | 1.0000 |

| S2 | -C1 | 1.630 (4) | C8B | -H8A | 1.0000 |

| N1 | -C1 | 1.155 (6) | C9A | -H9BA | 0.9100 |

| N2 | -C3 | 1.165 (4) | C9A | -H9AA | 0.9900 |

| N3 | -C2 | 1.127 (6) | C9A | -H9AB | 0.9900 |

| N4 | -C8A | 1.506 (8) | C9B | -H9BA | 0.9900 |

| N4 | -C8B | 1.506 (8) | C9B | -H9BB | 0.9900 |

| N4 | -H4B | 0.9100 | C9B | -H9AA | 0.9900 |

| N4 | -H4C | 0.9100 | C10A | -H10B | 0.9900 |

| N4 | -H8A | 0.9800 | C10A | -H10C | 1.0600 |

| N4 | -H4A | 0.9100 | C10A | -H10A | 0.9900 |

These disordered features, in (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4], imply that the crystal itself is inherently disordered with some cyclohexylammonium counterions arranged in the “upward” position in some unit cells and “downward” in other unit cells, giving on average the observed disorder of cyclohexylammonium; and with three of the thiocyanate ligands are ordered, while the fourth is disordered. The ordered ones are held in place by hydrogen bonds (shown in cyan dashed lines in Fig. 3) with the cyclohexylammonium counterions (Table 5), while the fourth does not have such interactions, indicating its unfavorable ordering in terms of energy. The whole observed disorder, in our synthesized inorganic-organic hybrid material, could be attributed to the intrinsic interactions among [Co(NCS)4]2- inorganic substructure and to the hydrogen bonds among the inorganic ionic complex of [Co(NCS)4]2- with the organic cyclohexylammonium counterions. Thus, entropy dominates and creates the observed disorder.

Table 5.

Hydrogen bonds (angstrom, degrees) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], R = 0.05.

| N4 | -- H4A | .. S0AA | 0.9100 | 2.6500 | 3.546(9) | 167.00 | 8_655 |

| N4 | -- H4B | .. S2 | 0.9100 | 2.7000 | 3.405(8) | 135.00 | . |

| N4 | -- H4C | .. S0AA | 0.9100 | 2.4300 | 3.310(10) | 164.00 | 8_454 |

| N4 | -- H4C | .. S0AA | 0.9100 | 2.8600 | 3.743(11) | 164.00 | 8_454 |

| N5 | -- H5A | .. S1 | 0.9100 | 2.4600 | 3.338(3) | 161.00 | . |

| N5 | -- H5C | .. S2 | 0.9100 | 2.5100 | 3.386(4) | 161.00 | 8_454 |

Fig. 3B, shows the layered array of [Co(NCS)4]2- inorganic substructure along the c-axis where the layers are connected through hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions (showed in red dashed lines). In each layer, there are apertures running through the parallel layers where the cyclohexylammonium counterions reside in these apertures.

Fig. 3(C) displays the layered structure of cyclohexylammonium counterions, viewed along a-axis, where the layers are parallel and are connected via hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions. Within each layer, cyclohexylammonium are arranged as columns, where the space between every two columns accommodates the inorganic complexes of [Co(NCS)4]2-.

Fig. 3D shows the structure of the entire compound, where the layers of both of the inorganic and organic moieties are connected by hydrogen bonds and van der Waals interactions, which are mainly responsible for the formation of the three dimensional (3-D) network.

The final coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters of the non-hydrogen atoms, hydrogen atom positions and isotropic displacement parameter, (an)isotropic displacement parameter, bond angles, values of torsion angles, bond distances (Å), contact distances, and translation of symmetry code to equivalent positions are given in Tables:

S1: Final coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters of the non-hydrogen atoms for: cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], S2: Hydrogen atom positions and isotropic displacement parameter for: cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4]), S3: (An)isotropic displacement parameter for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], S4: Bond angles (degrees) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], S5: Torsion angles for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], S6: Bond distances (Å) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], and S7: Contact distances (Angstrom) for cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], respectively, of the supplementary Material.

3.4.2. PXRD of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]

Simulation of the PXRD was conducted as a reference standard for the good match between the theoretically predicted and experimentally determined structures. However, there was no good match between the simulated and measured PXRD patterns, as shown in Fig. 4. We guess the big differences between them could be due to the inherent weak diffraction of XRD by (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] even after collecting the diffraction over a period of seven hours (the experimental pattern shown in Fig. 4). In addition, the disorder observed in the SXRD and grinding the complex to powder might be responsible for the observed differences between the simulated and measured PXRD patterns.

Fig. 4.

PXRD of (A) the experimental and (B) the simulated patterns for the 3D supramolecular of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate (II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4].

3.5. Electrochemical characteristics

Fig. 5 displays the redox characteristics of C6H11NH3+SCN− and (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4] complex. It is evident that the C6H11NH3+SCN− salt did not show any reversible redox couple within the tested potential window. A strong oxidation peak is observed starting at 0.49 V (vs. Ag/AgCl/3M KCl) which is irreversible and is probably due to oxygen evolution reaction in the aqueous medium. When CV of (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4] complex was carried out, it clearly showed a strong quasi-reversible redox couple with anodic peak at 1.40 V and cathodic peak appearing at 0.83 V (vs. Ag/AgCl/3M KCl). These anodic and cathodic peaks correspond to Co(II) and Co(III) redox couple. The peak separation of 0.58 V also confirmed 1-electron transfer process during the CV experiment. No other Co-species were detected [41].

Fig. 5.

CVs of C6H11NH3+SCN− and Co (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4] complex, casted over GC electrode, in 0.1 M KCl aqueous solution.

3.6. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

TGA is widely used for the thermal characterization of different materials [42, 43]. Fig. 6 displays the thermograms resulted from the thermogravimetric analyses of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] under air and helium (He), where stepwise decomposition behaviour was observed in both cases. Under air atmosphere, the complex showed thermal stability up to ∼72 °C, after which it started to decompose thermally and to lose ∼41% of its weight, corresponding to the loss of the two cyclohexylammonium counterions at ∼270 °C. The complex continued to decompose by losing three isothiocyanate ligands upon increasing the temperature to ∼523 °C. Afterwards, oxidation by molecular oxygen was observed, where Co3O4 was formed, as it was confirmed by the calculated remaining weight of 20.4 % (actual remaining weight = 22.2 %). The formation of Co3O4 was confirmed by PXRD analysis (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Thermogravimetric analysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] under air (blue) and helium (red).

Fig. 7.

PXRD patterns for CoS (A) and Co3O4 (B).

Under helium atmosphere, the thermal decomposition of the complex appeared to be faster than its thermal decomposition under air atmosphere. The complex, under helium atmosphere, started to decompose thermally at ∼67 °C, which after it lost the two cyclohexylammonium counterions at ∼252 °C, corresponding to a loss of ∼41%. The complex afterwards lost two of its isothiocyante ligands at 310 °C, after which it completed its decomposition to cobalt sulfide (CoS) at ∼ 605 °C, corresponding to a loss of ∼81.5% (calculated remaining weight for CoS = 18.5 %; actual remaining weight = 18.52 %). No more weight loss was observed after the complete conversion of cobalt sulfide, which its formation was confirmed by PXRD analysis (Fig. 7).

3.7. PXRD of the thermal decomposition products of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]

Fig. 7A, displays the XRD pattern for CoS, obtained from the thermal decomposition of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] at 610 °C under helium, with typically sharp, symmetric basal reflections at 2θ of 31.58, 35.78, 46.84, 55.38, and 75.5ο, which are indexed to the characteristic peaks (100), (101), (102), (110) and (202), respectively. The low intensities of the assigned peaks showed good crystallinity. Our pattern showed comparable result with the previous investigation performed by Qingsheng and his coworkers [42].

On the other hand, Fig. 7B illustrates the XRD pattern of Co3O4, obtained from thermal decomposition of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] at 550 °C under air, with indexes diffraction at 2θ of 19.28, 37.2, 38.86, 45.24, 55.96, 59.56, 65.34, 75.76, and 77.68 ο, corresponding to the characteristic peaks (111), (220), (311), (222), (400), (422), (511), (440), (533) and (622), respectively. The Co3O4 product is a face centered cubic shape (space group Fd-3m). Our results are in good agreement with a similar diffraction patterns observed by Chira and his coworkers [30].

3.8. Nitrogen physisorption for Co3O4 and CoS products obtained from the thermal pyrolysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4]

The summary of the nitrogen physisorption for Co3O4 and CoS products obtained by the thermal pyrolysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] under air and helium, respectively, are presented in Table 6. The surface area and pore volume of CoS were higher than those of Co3O4. However, the pore size of CoS was a little bit smaller than that of Co3O4. The higher surface area and pore volume of CoS product could be attributed to carbonization process of the cyclohexylammonium, which functioned as a pore template and prevented the collapse of pores. On the other hand, Co3O4 formed through the thermal pyrolysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] under air, where oxygen oxidized the cyclohexylammonium, causing the collapse of pores.

Table 6.

Summary of the nitrogen physisorption for Co3O4 and CoS products obtained from the thermal pyrolysis of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] under air and helium.

| Physical characterization parameters | Co3O4 | CoS |

|---|---|---|

| *Surface area | ||

| Surface area (BET) [m2/g] | 8.93 | 35.94 |

| Langmuir Surface Area [m2/g] | 13.51 | 53.2826 |

| t-Plot Micropore Area [m2/g] | 1.2888 | 9.5372 |

| t-Plot External Surface Area [m2/g] | 7.6468 | 26.4104 |

| *Pore Volume | ||

| Single point adsorption total pore volume of pores less than 767.019 Å diameter at P/P0 = 0.974100466 [cm3/g] | 0.018886 | 0.06268 |

| *Pore Size | ||

| Adsorption average pore width [Å] | 84.54 | 69.7496 |

| BJH Adsorption average pore diameter [Å] | 188.37 | 106.919 |

| BJH Desorption average pore diameter [Å] | 102.462 | 93.556 |

3.9. SEM and TEM morphology investigation of CoS and Co3O4

Fig. 8 illustrates the electron micrograph images of CoS, prepared by the thermal decomposition of (HCHA)2[Co(NCS)4] at 610 °C under helium, with various magnifications. Agglomerated CoS spherical shape particles and smaller rod-like particles were observed. Similar observation by the SEM for the synthesised CoS nanorods (NR) samples was also reported [44, 45]. The more revealed accurate images from Fig. 8E and F show particles with an average particle size of approximately 10 nm. Moreover, the aggregation phenomenon observed by TEM technique in Fig. 8 (E) correlates with the SEM observation, which may be attributed to the higher surface energy of the particles.

Fig. 8.

SEM electron micrograph images of CoS at various magnifications of A) 1,900, B) 3000, C) 15,000 D) and 45,000. TEM images (E) and (F).

The SEM micrographs show aggregates of Co3O4 (Fig. 9A and B). For more assessment on the Co3O4 morphology and shape, TEM images (Fig. 9C and D) show aggregation of Co3O4 particles at range diameter from 50 to 200 nm, where cubic, orthorhombic (marked with yellow arrows), rod-like (marked with red arrows), and spherical Co3O4 particles could be detected. Such morphology of Co3O4 particles was previously reported [46, 47, 48].

Fig. 9.

SEM electron micrograph images of Co3O4 at two different magnifications: a) 4,500 and b) 10,000 magnifications. TEM images (c) and (d).

4. Conclusion

In summary, we have reported the preparation of a novel 3D, supramolecular structure of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II), (C6H11NH3)2[Co(NCS)4], with orthorhombic crystal system in a yield of ∼100%. The formation of this complex was proved by FT-IR, UV-Vis, CV, and SXRD techniques. We have attempted to prove that our prepared new complex acted as single-source precursor for the synthesis of CoS and Co3O4 nanoparticles, two important classes of materials, via the readily thermal decomposition under helium and air, respectively.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Abdulaziz Bagabas: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Murad Alsawalha: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Manzar Sohail: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Sultan Alhoshan, Rasheed Arasheed: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Funding statement

This work was supported by King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), Saudi Arabia, through project No 20-0180.

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Christopher Trickett for determining the crystals structure of cyclohexylammonium tetraisothiocyanatocobaltate(II) and Dr. Omar Yaghi for using his SXRD facility.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Bagabas A.A., Alhoshan S.B., Ghabbour H.A., Chidan Kumar C.S., Fun H.-K. Crystal structure of cyclohexylammonium thiocyanate. Acta Cryst. 2015;E71:62–63. doi: 10.1107/S2056989014027297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang H., Wang X., Zhang K., Teo B.K. Molecular and crystal engineering of a new class of inorganic cadmium-thiocyanate polymers with host–guest complexes as organic spacers, controllers, and templates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;183:157–195. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Francese G., Ferlay S., Schmalle H.W., Decurtins S. A new 1D bimetallic thiocyanate-bridged copper(II)–cobalt(II) compound. New J. Chem. 1999;23:267–269. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shurdha E., Moore C., Rheingold A., Lapidus S., Stephens P., Arif A., Miller First row transition metal(II) thiocyanate complexes, and formation of 1-, 2-, and 3-dimensional extended network structures of M(NCS)2(solvent) 2 (M = Cr, Mn, Co) composition. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:10583–10594. doi: 10.1021/ic401558f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye H.Q., Li Y.Y., Huang R.K., Liu X.P., Chen W.Q., Zhou J.R., Yang L.-M., Ni C.L. Unusual layer structure in an ion-paired compound containing tetra(isothiocyanate) cobalt(II) dianion and 4-nitrobenzylpyridinium: crystal structure and magnetic properties. J. Struct. Chem. 2014;55:691–696. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui-Qing Y., Li-Jie S., Xiang X.C., Xuan L., Qian T.L., Xiao Y.W., Jia R.Z., Le M.Y., Chun L.N. Syntheses, crystal structures, weak interaction, magnetic and luminescent properties of two new organic–inorganic molecular solids with substituted chlorobenzyl triphenylphosphinium and tetra(isothiocyanate)cobalt(II) anion. Synth. Met. 2015;199:232–240. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cai H.T., Liu Q.T., Ye H.Q., Su L.J., Zheng X.X., Li J.N., Ou S.H., Zhou J.R., M Yang L., Ni C.L. Syntheses, crystal structures, luminescent and magnetic properties of two molecular solids containing naphthylmethylene triphenylphosphinium cations and tetra (isothiocyanate)cobalt(II) dianion. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015;142:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.01.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao X.L., Shan T.Y., Ning W., Zhao Y.L., Ying L.L. Three new supramolecular complexes based on 2-propyl-1 H-imidazole-4,5-dicarboxylate: synthesis, structures and properties. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2010;36:[641]–[647]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen X., Chen W., Han S., Liu J., Zhou J., Yu L. Yang, Ni C., Hu X. Two hybrid materials self-assembly from tetra(isothiocyanate)cobalt(II) dianion and substituted benzyl triphenylphosphinium. J. Mol. Struct. 2010;984:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns D.T., Hanprasopwaitana P., Murphy B.P. The spectrophotometric and fluorimetric determination of cobalt by extraction as 2,4-dichlorobenzyltriphenyl- phosphonium tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) Anal. Chim. Acta. 1982;134:397–400. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns D.T., Tungkananuruk N. The spectrophotometric determination of cobalt after extraction of tetramethylene-bis(triphenyl-phosphonium) tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) with microcrystalline benzophenone. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1986;182:219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns D.T., Kheawpintong S. The spectrophotometric determination of cobalt by extraction of triphenylsulphonium tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) Anal. Chim. Acta. 1984;162:437–442. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burns D.T., Tungkananuruk N. Spectrophotometric determination of cobalt after extraction of tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) with brilliant green into microcrystalline naphthalene. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1986;189:383–387. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selmer-Olsen A.R. Liquid-liquid extraction of cobalt thiocyanate with trhsooctylamine. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1964;131:33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns D.T., Kheawpintong S. Spectrophotometric determination of cobalt by extraction of tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) with propylene carbonate. Anal. Chim. Acta. 1984;156:329–333. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monk R.G., Exelby K.A. Determination of beryllium by means of hexamminecobalt (III) carbonatoberyllate—II: high-precision indirect determination of beryllium by titration of cobalt with edta. Talanta. 1965;12:91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohzeki K., Yamagishi M. Determination of quaternary ammonium ion as the precipitate with tetrathiocyanatocobaltate(II) by densitometry. Analyst. 1985;110:1517–1519. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowd A.J., Thorburn Burns D. Studies on the analytical chemistry of iodonium compounds. Part I - the spectrophotometric determination of the diphenyliodonium cation by extraction as the tetrathiocyanato cobaltate(II) complex. Mikrochim. Acta. 1965;5–6:1151–1159. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ionita G.M., Ilie G., Angel C., Dan F., Smith D.K., Chechik V. Sorption of metal ions by poly(ethylene glycol)/â-CD hydrogels leads to gel-embedded metal nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2013;29:9173–9178. doi: 10.1021/la401541p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.J Osborne S., Wellens S., Ward C., Felton S., Bowman R.M., B Binnemans K., Swadźba-Kwaśny M., N Gunaratne H.Q., Nockemann P. Thermochromism and switchable paramagnetism of cobalt(II) in thiocyanate ionic liquids. Dalton Trans. 2015:11286–11289. doi: 10.1039/c5dt01829c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lammerer A. Two-dimensional hydrogen-bonding patterns in a series of salts of terephthalic Acid and the cyclic Amines CnH2n−1NH2, n = 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, and 12. Cryst. Growth Des. 2011;11:583–893. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagabas A.A., Aboud M.F.A., Shemsi A.M., Addurihem E.S., Al- Othman Z.A., Chidan Kumar C.S., Fun H.-K. Cyclohexylammonium nitrate. Acta Cryst. 2014;70:253–254. doi: 10.1107/S1600536814002244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tie J., Han J., Diao G., Liu J., Xie Z., Chenga G., Sun M., Yu L. Controllable synthesis of hierarchical nickel cobalt sulfide with enhanced electrochemical activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;435:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maneesha P., Paulson Anju, Muhammed Sabeer N.A., Pradyumnan P.P. Thermo electric measurement of nanocrystalline cobalt doped copper sulfide for energy generation. Mater. Lett. 2018;225:57–61. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Lin C., Mersch D., Jefferson D.A., Reisne E. Cobalt sulphide microtube array as cathode in photoelectrochemical water splitting with photoanodes. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:4906–4913. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y., Xu J., Zhang Y., Zheng Y., Hu X., Liu Z. Facile fabrication of flower-like CuCo2S4 on Ni foam for supercapacitors application. J. Mater. Sci. 2017;52:9531–9538. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang T., Liu M., Ma H. Facile synthesis of flower-like copper-cobalt sulfide as binder-free faradaic electrodes for supercapacitors with improved electrochemical properties. Nanomaterials. 2017;7:140. doi: 10.3390/nano7060140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Daosong Z., Yongsheng F., Lili Z., Junwu Z., Xin W. Design and fabrication of highly open nickel cobalt sulfide nanosheets on Ni foam for asymmetric supercapacitors with high energy density and long cycle-life. J. Power Sources. 2018;378:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farhadi S., Pourzare K. Simple and low-temperature preparation of Co3O4 sphere-like nanoparticles via solid-state thermolysis of the [Co(NH3)6](NO3)3 complex. Mater. Res. Bull. 2012;47:1550–1556. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chira R.B., Debraj D.P., Nirmalendu D. Surfactant-controlled low-temperature thermal decomposition route to monodispersed phase pure tricobalt tetraoxide nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2013;90:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li W.Y., Xu L.N., Chen J. Nanomaterials in lithium-ion batteries and gas sensors. J. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2005;15:851–857. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F., Zhang D.E., Tong Z.W. Facile synthesis of Co3O4 cubic structures and evaluation of their catalytic properties, synthesis. Inorg. Nano Met. Chem. 2013;41 43 756-760. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan L., Li L., Tian D., Li C., Wang J. Synthesis of Co3O4 nanomaterials with different morphologies and their photocatalytic performances. JOM. 2014;66:1035–1042. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bai B.Y., Li J. Positive effects of K+ ions on three-dimensional mesoporous Ag/Co3O4 catalyst for HCHO oxidation. ACS Catal. 2014;4:2753–2762. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang D.E., Xie Q., Chen A.M., Wang M.Y., Li S.Z., Zhang X.B., Han G.Q., Ying A.L., Gong J.Y., Tong Z.W. Fabrication and catalytic properties of novel urchin-like Co3O4. Solid State Ionics. 2010;181:1462–1465. [Google Scholar]

- 36.V Yongge L., Yong Li., Wenjie Shen. Synthesis of Co3O4 nanotubes and their catalytic applications in CO oxidation. Catal. Commun. 2013;42:116–120. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lai Y.-L., Lee C.-C., Shu Y.-Y., Wang C.-B. Microwave-assisted rapid fabrication of Co3O4 nanorods and application to the degradation of phenol. Catal. Today. 2008;131:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad W., Noor T., Zeeshan M. Effect of synthesis route on catalytic properties and performance of Co3O4/TiO2 for carbon monoxide and hydrocarbon oxidation under real engine operating conditions. Catal. Commun. 2017;89:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Z˙iya K., Mehmet K., Mahir Bülbül M. Infrared spectroscopic study on the Td-Type clathrates: Cd(Cyclohexylamine)2M(CN)4·2C6H6 (M = Cd or Hg) J. Incl. Phenom. Macro. 2001;40:317–321. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sabatini A., Bertini I. Infrared spectra between 100 and 2500 Cm.-1 of some complex metal cyanates, thiocyanates, and selenocyanates. Inorg. Chem. 1965;4:959–961. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ozoemena K.I., Nyokong T., Westbroek P. Self-assembled monolayers of cobalt and iron phthalocyanine complexes on gold electrodes: comparative surface electrochemistry and electrocatalytic interaction with thiols and thiocyanate. Electroanalysis. 2003;14:1762–1770. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qingsheng W., Zhude X., Haoyong Y., Qiulin N. Fabrication of transition metal sulfides nanocrystallites via an ethylenediamine-assisted route. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005;90:73–77. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mansour Mohammedramadan T., Aqsha A., Nader M. X-ray diffraction and TGA kinetic analyses for chemical looping combustion applications. Data in Brief. 2018;17:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.12.044. Elsevier. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Limin Z., Kai Z., Jinzhi S., Qinyou An., Zhanliang T., Yong-Mook K., Jun C. Structural and chemical synergistic effect of CoS nanoparticles and porous carbon nanorods for high-performance sodium storage. Nano Energy. 2017;35:281–289. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mani Siv., Mani Sak., Shen-Ming C. Simple synthesis of cobalt sulfide nanorods for efficient electrocatalytic oxidation of vanillin in food samples. J. Comb. Chem. 2017;490:719–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkatachalam V., Alsalme A., Alswieleh A., Jayavel R. Shape controlled synthesis of rod-like Co3O4 nanostructures as high performance electrodes for supercapacitors applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2018;29:6059–6067. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hongyan X., Jiangtao D., Zhenyin H., Libo G., Qiang Z., Jun T., Binzhen Z., Chenyang X. A study of the growth process of Co3O4 microcrystals synthesized via a hydrothermal method. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2016;51:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu R., Zeng H.C. Mechanistic investigation on salt-mediated formation of free-standing Co3O4 nanocubes at 95 °C. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:926–930. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.