Abstract

Global health is a fashionable term frequently used in the twenty-first century’s news that is rarely understood by ear, nose and throat (ENT) professionals. Communicable diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria have been in the headlines of global health for decades. Despite the recent public health concerns about noncommunicable diseases, including ENT disorders, these disorders still receive little attention on the global health stage. Despite the ‘benign’ nature and a large number of patients affected at a given time, noncommunicable diseases were found to account for 60% of international mortality in 2008. More specifically to ENT, disabling hearing impairment has been found to be the most common disability globally. Therefore, it is now critical for otolaryngologists worldwide to get involved in the overlooked ENT global issues. This article discusses the main challenges faced by the ENT community in the developing world and proposes what can be done to help.

Keywords: Global health, ENT , Otolaryngology, Hearing loss

Introduction

‘Global health’ is a topical term, widely used in various contexts in the twenty-first century. Efforts to distinguish global health from public health and international health have resulted in multiple proposed definitions.1 Regardless of how one might define global health, its underlying concept is an international collaboration aimed at promoting health equality across all nations. The relevance of global health is rarely understood or discussed by otolaryngologists.

Communicable diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis and malaria have dominated headlines and remain a priority in the field of global health. Despite recent initiatives, noncommunicable diseases including ear, nose and throat (ENT) disorders, still receive little attention on at the level of global health. The low-profile status of ENT disorders is thought to be due to a large number of patients affected at a given time and their non-life-threatening nature.2 Noncommunicable diseases accounted for 60% of global mortality in 2008 and disabling hearing impairment is the most common disability internationally.3,4 Globally, ENT issues have been overlooked, but the involvement of otolaryngologists worldwide is becoming increasingly crucial. This paper discusses the key challenges faced by the ENT community in developing nations and describes future strategies to ease such challenges.

Challenges faced by ENT globally

The global shortage of ENT services

Although 80% of the world population resides in developing nations, their ENT resources are often limited and in some cases non-existent. In 2009, a survey demonstrated a severe shortage of qualified ENT surgeons and the scarcity of ENT training programmes in 18 countries within the African continent.5 Excluding South Africa, the number of ENT surgeons per 100,000 population in these countries was five times lower than in the UK. The lowest ratio was found in Malawi at one ENT surgeon per 12 million population. Such shortage of manpower can be attributed to the scarcity of ENT training programmes and the recent emigration of medical professionals from low-income to higher-income countries.5,6 Evidently, ENT programmes only existed in 50% of these countries.5 It can thus be suggested that most ENT disorders in these countries are being managed by doctors with no ENT specialist training or are not being treated at all. Additionally, basic procedures such as myringotomy and tympanoplasty were virtually unavailable in these African countries,5 so life-saving surgeries such as mastoidectomy were seldom performed.

The World Health Organization (WHO) suggests that there are 72 million hearing aid users internationally and estimate that 20% of hearing loss suffers would benefit from increased availability of hearing aids in developing countries alone.7 Unfortunately, less than 3% of those requiring hearing aids in developing countries have access to these medical devices.7 These figures emphasise the need to address the shortage of hearing aids in these nations. The difficulty to access hearing aids could be explained by the poor supply of audiology services to fit and maintain them. Additionally, fitting hearing aids and screening for hearing loss were not available to most of patients in such countries. A deficit of 82,541 audiologists compared with UK audiology services has been reported.5 This scarcity of audiologists may contribute to the lack of access to these services.

Hearing loss in developing countries

Disabling hearing loss is the most common disability around the globe, yet this disability is widely misunderstood and ‘neglected’. It is traditionally diagnosed and quantified using pure tone audiometry. Disabling hearing loss is defined as ‘a permanent unaided pure tone hearing threshold level for the better ear of 41 Db or greater averaged over the frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz’.8 It is pivotal to raise international awareness that a diagnosis of disabling hearing loss does not solely consist of the inability to hear speech and sounds. It is often associated with many of hidden struggles in the life stories of individuals around the world.

In 2011, the prevalence of disabling hearing loss was approximately 360 million people (Fig 1).9 It is estimated that around 15% of the world’s adult population live with a degree of hearing loss and it has been shown that there is significant geographical variation in its prevalence (Fig 2).9 A significantly higher prevalence of disabling hearing loss has been shown to exist in developing countries compared with their affluent counterparts.9

Figure 1.

Mortality and burden of diseases, World Health Organization 2011 estimates for disabling hearing loss.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of disabling hearing loss for all population by selected regions.

Disabling hearing loss is a communication disorder, which often results in the social isolations of sufferers. Following the loss of hearing, most people experience major challenges in communication. Lack of exposure may mean the individuals who are able to hear may feel apprehensive towards communicating with people living with hearing loss. The hidden nature of such a disability, which is only displayed when they attempt to converse with others, adds another level of challenges to the disorder. Subsequently, a breakdown in interpersonal communication occurs which leads to social separation between the deaf person and the hearing person. Disabling hearing loss does not only isolate the sufferers but also has a hidden profound impact on various aspects of sufferers’ lives at all ages worldwide.

It is widely known that a congenitally deaf child is more likely to experience tremendous difficulties in speech and language development. Language is vital in intellectual, psychological and social development.10 Thus, it is common for a child who was born deaf to be mistaken for having severe learning disabilities. In developing countries, poor understanding of such hearing disabilities significantly impacts children with hearing loss. For example, many children with disabling hearing loss often do not have access to hearing aids and special educational needs schools that are able to justify the use of their limited resources for such children within developing countries. Consequently, access to education is more difficult for these children. Additionally, WHO has found that children with hearing loss are at an increased risk of physical, social, emotional and sexual abuse and even murder.9 The global understanding of being deaf varies globally depending on local education regarding hearing loss as a disability, cultural beliefs and socioeconomic status. Therefore, the stigmatisation of sufferers of exists in many cultures across the globe. For instance, an assumption of low intellectual ability of a child suffering from leads to labelling and bullying during school. In various regions, this discrimination is heightened due to physical isolation of such children from other children of a similar age.

Disabling hearing loss in adults has devastating consequences on all aspects of a sufferer’s life. According to WHO, it can lead to embarrassment, loneliness, social isolation and stigmatisation, prejudice, abuse, psychiatric disturbances, depression, difficulties in relationships with partners and children, restricted career choices, occupational stress and relatively low earnings.7 For instance, working aged adults with disabling hearing loss are often unable to find employment in higher-paid positions in developing countries and are thus limited to lower-paid positions. There are numerous stories of young women in developing nations with hearing loss struggling to get married with the stigma attached to having an inherited ‘incurable disease’.

Common causes of disabling hearing loss in developing nations

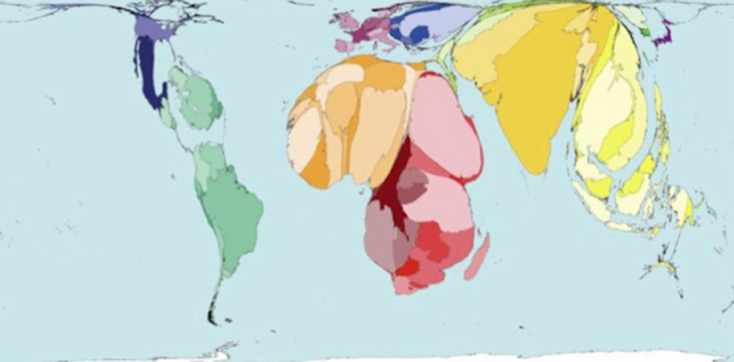

While age-related sensorineural loss is the most common cause of disabling hearing loss in the West, the most prevalent causes in developing nations include chronic otitis media and the inappropriate use of ototoxic drugs.9 Chronic otitis media is the leading cause of conductive hearing loss globally and affects from 65 to 330 million people internationally. Ninety per cent of chronic otitis media exists within developing nations such as those within Southeast Asia, the Western Pacific region and Africa. Chronic otitis media is also responsible for other more serious complications including mastoiditis and the fatal intracranial infections which occur via haematogenous spread.7,11 In addition, a rare complication involves the erosion of the walls of the middle ear and mastoid cavity, which can lead to facial nerve paralysis, lateral sinus thrombosis, labyrinthitis, meningitis and brain abscess.11,12 The most fatal complication is intracranial infections via haematogenous spread. WHO has published reports of the global variation in risks of mortality due to ear infections, illustrated in Figure 3 with higher mortality rates as more magnified areas on the world map. It can be interpreted from the diagram that it is much more life-threatening to have an ear infection if one resides in Africa and Asia. Although chronic otitis media and its deadly complications can be prevented by effective medical and surgical treatments, these management options are often inaccessible in developing nations. It is common to see patients within developing countries with more advanced presentations which are rarely seen in developed countries. A major cause of this issue is the scarcity of ear surgery, which is discussed further below.

Figure 3.

Mortality rate from ear infections, World Health Organization 2002 statistics.

According to WHO, there were approximately 32 million deaf children worldwide and 60% of the common causes of childhood hearing loss within developing countries are preventable.9 The common birth-related causes of hearing loss include complications during birth, low birth weight and prematurity.9 Such causes can be avoided through financial investment in effective perinatal care and early hearing loss screening aiming to achieve earlier detection and management of hearing loss. Additionally, infections causing hearing loss in children such as mumps, rubella, measles and meningitis can be prevented through the implementation of national vaccination programmes. Furthermore, the misuse of ototoxic drugs such as aminoglycosides in developing countries can be prevented by raising awareness on rational antibiotics use among health-care professionals.

The shortage of ear surgery in developing nations

Chronic otitis media, cholesteatoma and their serious intracranial complications are the main indications for ear surgery in developing nations. Within developing countries, ear surgery is carried out by Western non-profit humanitarian organisations such as the Britain Nepal Otology Service (BRINOS). BRINOS is run by ENT surgeons, specialist nurses and anaesthetists from the UK and Nepal. They hold 30 ear camps biannually in the rural Nepal to provide specialist ear surgery for patients living far from ENT departments in the country’s capital.13

The cochlear implant is a potentially life-changing ear surgery and a controversial topic in resource-limited countries. A cochlear implant can dramatically improve the life of a congenitally deaf child by providing the possibility of normal speech and language development.14,15 However, according to the National Institute for Health Care Excellence, a cochlear implant costs roughly £38,000–45,000. This large price tag is normally justified by the increase in quality of life of recipients in developed countries. Controversially, the cost of one cochlear implant is able to provide hearing aids for thousands of people in developing nations.

What can we do to help?

First, the international ENT community should participate in advocating for the importance of ENT disorders. This could be achieved with international ENT events such as the World Hearing Day and the International Ear Care Day. Additionally, it is crucial to set up as many groups of ENT professionals with interests in global health as possible. An example is the Global Health ENT group established by ENT UK, who aim to highlight the importance and prevalence of ENT disease globally.

Focusing on education and training is key to long-term improvements in the quality of ENT services and self-sufficiency in developing nations. One suggestion is to establish ENT training programmes for doctors from developing countries with the aim of them returning to their home countries to help local ENT services and train other local doctors. This strategy has the potential to create long-term independent ENT services and also to minimise medical emigration, which threatens health care in developing countries. For instance, BRINOS has been contributing tremendously to Nepalese ENT training by providing training for young Nepalese surgeons and other ENT specialists.16 Furthermore, online open-access ENT resources should be the next target for training and education in a time when the increase in internet connections resulted in a greater accessibility to literature. We should aim to increase the availability of free high-quality ENT e-learning websites, journals and e-books for ENT professionals globally. Examples of free resources include e-leftENT from ENT UK and the Journal of Laryngology and Otology, which provides open-access treatment guidelines, articles and ENT resources for ENT surgeons worldwide.

Conclusion

It is crucial to increase awareness of the hidden challenges of ENT in the global population. Otolaryngologists around the world should be reminded of the shortage of ENT services in developing countries and the widespread yet ‘neglected’ disability of disabling hearing loss. The UK ENT community can provide tremendous support to achieve equity in ENT services globally by raising awareness about global health issues within ENT and helping expand ENT education and training in developing nations.

References

- 1.Koplan J, Bond T, Merson M et al. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009; (9679): 1,993–1,995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update. Geneva: WHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mackenzie I, Smith A. Deafness: the neglected and hidden disability. Ann Trop Med Parasitol 2009; (7): 565–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagan J, Jacobs M. Survey of ENT services in Africa: need for a comprehensive intervention. Glob Health Action 2009; (1): doi: 10.3402/gha.v2i0.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra A. The metrics of the physician brain drain. N Engl J Med 2006; (5): 528–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olusanya B, Neumann K, Saunders J. The global burden of disabling hearing impairment: a call to action. Bull World Health Organ 2014; (5): 367–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pascolini D, Smith A. Hearing Impairment in 2008: A compilation of available epidemiological studies. Int J Audiol 2009; (7): 473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization Millions of People in the World have Hearing Loss that can be Treated or Prevented. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs L. A Deaf Adult Speaks Out. Washington DC: Gallaudet University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mawson S, Ludman H. Diseases of the Ear. London: Arnold; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shenoi P. Management of chronic suppurative otitis media : Scott-Brown WG. Scott-Brown's Otolaryngology, 6th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1987. 215–237. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foundation, history and aims of BRINOS http://www.brinos.org.uk/History.htm (cited June 2018).

- 14.Geers AE, Moog JS. The effectiveness of cochlear implants and tactile aids for deaf education: a report of the CID Sensory Aids Study. Volta Review Monograph 1994; (5). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osberger MJ, Maso M, Sam LK. Speech intelligibility of children with cochlear implants, tactile aids, or hearing aids. J Speech Hear Res 1993; (1): 186–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weir N. Ear surgery camps in Nepal and the work of the Britain Nepal Otology Service (BRINOS). J Laryngol Otol 1991; (12): 1,113–1,115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]