Abstract

Aims

There are indications that economic crises can affect public health. The aim of this study was to describe characteristics, health status, and socio‐economic status of outpatient heart failure (HF) patients several years after a national economic crisis and to assess whether socio‐economic factors were associated with patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs).

Methods and results

In this cross‐sectional survey, PROMs were measured with seven validated instruments, as follows: self‐care (the 12‐item European Heart Failure Self‐Care Behaviour scale), HF‐related knowledge (Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale), symptoms (Edmonton Symptom Assessment System), sense of security (Sense of Security in Care—‘Patients' evaluation’), health status (EQ‐5D visual analogue scale), health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) (Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire), and anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale). Additional data were collected on access and use of health care, household income, demographics, and clinical status.

The patients' (n = 124, mean age 73 ± 14.9, 69% male) self‐care was low for exercising (53%) and weight monitoring (50%) but optimal for taking medication (100%). HF‐specific knowledge was high (correct answers 12 out of 15), but only 38% knew what to do when symptoms worsened suddenly. Patients' sense of security was high (>70% had a mean score of 5 or 6, scale 1–6). The most common symptom was tiredness (82%); 12% reported symptoms of anxiety, and 18% had symptoms of depression. Patients rated their overall health (EQ‐5D) on average at 65.5 (scale 0–100), and 33% had poor or very bad HRQoL. The monthly income per household was <€3900 for 84% of the patients. A total of 22% had difficulties making appointments with a general practitioner (GP), and 5% had no GP. On average, patients paid for six health care‐related items, and >90% paid for medications, primary care, and visits to hospital and private clinics out of their own pocket. The cost of health care had changed for 71% of the patients since the 2008 economic crisis, and increased out‐of‐pocket costs were most often explained by a greater need for health care services and medication expenses. There was no significant difference in PROMs related to changes in out‐of‐pocket expenses after the crisis, income, or whether patients lived alone or with others.

Conclusions

This Icelandic patient population reported similar health‐related outcomes as have been previously reported in international studies. This study indicates that even after a financial crisis, most of the patients have managed to prioritize and protect their health even though a large proportion of patients have a low income, use many health care resources, and have insufficient access to care. It is imperative that access and affordable health care services are secured for this vulnerable patient population.

Keywords: Heart failure, Patient‐reported outcome measures, Quality of life, Self‐care, Knowledge, Symptoms

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is one of the most common and rapidly increasing public health burdens globally.1 Heart failure accounts for 1–4% of all hospital admissions; consequently, the burden of HF is costly and is estimated to account for 1–3% of national health expenditure in Western countries.2, 3 In 2012, Iceland spent 9.1% of its gross domestic product on health. This is comparable with that of the neighbouring countries with similar health care systems, such as Sweden, Norway, Finland, and the UK.4 Overall HF costs were estimated to represent 2.1% of the country's total health expenditure, of which 69% were direct costs, which was slightly more than was estimated globally per annum (60%). This is similar to the estimated overall HF costs of the aforementioned countries.4

Chronic HF results in worsening physical and functional capacities and is characterized by unpredictable and life‐threatening exacerbations and symptoms that often result in hospital admissions.1 Subsequently, health status domains such as symptoms, functional limitations, and quality of life are affected.5, 6

The health status of the European population has been measured regularly, showing that self‐reported health status is worse in the lowest‐income groups compared with the highest‐income groups in all countries within the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD).7 In an economic crisis, such as the one that affected many European countries in the fall of 2008, people with chronic diseases such as HF might be expected to suffer financially, potentially leading to a decline in their health status.

The economic crisis in the autumn of 2008 hit many European countries hard. This is evident in the fall of total health spending in one out of every three OECD countries between 2009 and 2011,7 although there are signs of a slow rise after 2013.8 Since the crisis, per capita health expenditure has decreased by 3.8%7 and out‐of‐pocket costs are currently approaching 20% of total spending.8 There are indications that economic crises directly affect the health of the public. For example, in the week following the economic collapse in Iceland in October 2008, visits to cardiac emergency departments increased by 26% than in previous weeks.9 Banking crises are a significant determinant of short‐term increases in heart disease mortality rates, and may have more severe consequences for developing countries.10 However, little is known about the long‐term effects of economic crises on health.

Multidisciplinary outpatient HF clinics are recommended for the care of chronic HF patients.1 They can reduce the risk of unplanned admissions11 and are associated with favourable cost outcomes.12 To improve outcomes, it is important to have a clear profile of the patient population and their need for specialized health care. At times of economic restraint and limited budget, this is more important than ever, and the services must be focused and meet patients' needs. For these purposes, patient‐reported outcome measures (PROMs) are an important aspect of outcomes of clinical trials.13 PROMs are quantified measures of patients' perspectives regarding symptoms, functional limitations of diseases, and quality of life.13, 14 PROMs include any treatment or outcome evaluation obtained directly from patients through interviews, self‐completed questionnaires, diaries, or other data collection tools such as hand‐held devices and web‐based forms.15

In 2014, Iceland was recovering after the economic crisis, but there had been considerable cutbacks in the health care system. The demand for cost‐effective care and shorter hospital stays was constant. Emphasis was therefore on continuing the development of outpatient hospital clinics and specialized services within primary health care. To develop HF management in these circumstances, a thorough profile of the patient population was needed. We were interested in studying the patient population of HF patients who attended a multidisciplinary outpatient hospital clinic and in assessing whether socio‐economic factors were associated with PROMs.

Methods

The aim of this study was to describe the characteristics, health status, and social and economic status of Icelandic HF patients receiving care from an outpatient HF clinic 6 years after the national economic crisis in 2008 and, furthermore, to assess whether socio‐economic factors were associated with PROMs.

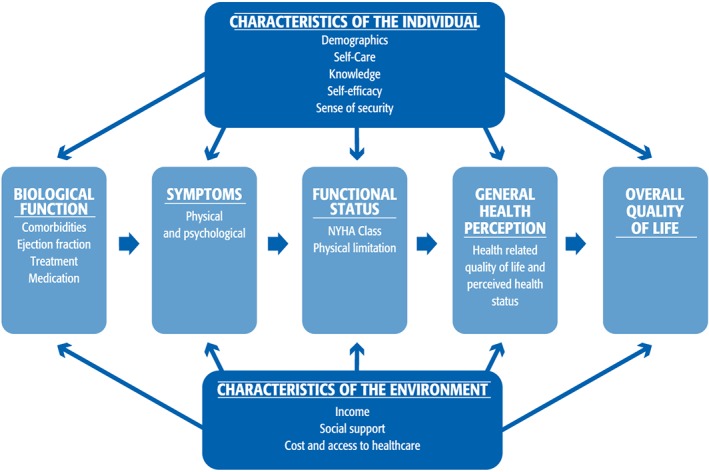

In order to describe the patients' health status in a holistic and broad context, the Wilson and Cleary model of health‐related quality of life (HRQoL)16 as revised by Ferrans et al.17 was chosen (Figure 1 ). The model proposes a classification scheme for different measures of health outcomes and facilitates the understanding of the associations of traditional clinical variables and health status measures. The model has been recommended to guide HRQoL research18 and has been deemed appropriate for use in studies on HF patients.19 Similar to Wilson and Cleary,16 we use the terms ‘health status’ and ‘HRQoL’ interchangeably.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model with the selected patient‐reported outcome measures used in the study (revised model of Wilson and Cleary by Ferrans et al.17 and used with permission from C. E. Ferrans). NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Design

This is a cross‐sectional study, and data were collected with mailed questionnaires and from electronic patient records in the fall of 2014.

Setting

Iceland is one of the Nordic countries, with a population of 335 000. Around two‐thirds of the population live in the capital Reykjavik and the surrounding areas. Iceland has been ranked highly in economic, political, and social stability and equality but was severely hit by the economic crisis in October 2008. In 2013, it was ranked as the 13th most developed country in the world.20 Iceland's health care system has universal coverage for health care costs for most services.21

The study was conducted in Landspítali (the National University Hospital of Iceland), a 600‐bed hospital, which runs the country's only specialized cardiac unit and an outpatient HF clinic. The clinic has a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, which includes assessment of health status, optimization of medication, and self‐care education. Patients can call the clinic if symptoms worsen and can make a same‐day appointment when necessary.

Data collection

A list of all patients registered as clients of the HF clinic when data collection started was obtained from the Department of Finance and Information at Landspítali. The survival status of the 287 registered patients was checked in the Icelandic Population Register. Through the hospital's patient records system, registered patients were also checked to establish whether they matched the inclusion criteria of the study. Inclusion criteria for participation were age ≥ 18, able to understand Icelandic, not documented with cognitive impairment, and able to complete the questionnaires independently or with help from a family member/friend or a research assistant.

A total of 227 (79%) patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were mailed an information letter, questionnaire, and a prepaid return envelope. A reminder phone call was made 1–2 weeks later in order to answer questions and offer assistance with completing the questionnaire. Six patients accepted such assistance.

Ethical considerations

The study conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki22 and received approval from the National Bioethics Committee (14‐107‐S1), the Data Protection Authority (2014040651), and the medical chief at LUH. In the information letter, the participants were informed that returning a filled‐out questionnaire was regarded as consent to participation.

Measures

Patient‐reported outcome measures were measured with seven previously validated and structured instruments on self‐care, HF‐specific knowledge, symptoms, anxiety and depression, sense of security, and HRQoL. Table 1 presents the instruments and their psychometric properties. Questions about access and use of health care were adjusted from Jonsdottir et al.31 Instruments not available in Icelandic were translated from their original languages to Icelandic and then back translated. Moreover, in cooperation with the authors, discrepancies were clarified and the text was changed accordingly. The whole battery of instruments was then pilot tested on eight patients who had no major difficulties with answering the questionnaire.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the instruments used in the study

| Scale/ Subscale | Number of items | Score | Responses | Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

European Heart Failure Self‐Care Behavior Scale (EHFScB)a

)

Consulting |

12 4 |

12‐60 4‐20 |

5‐point scale 1 to 5 (completely agree/disagree) Higher score indicates worse self‐care |

0.938 |

| Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale (DHFKS)b ) | 15 | 0‐15 |

Multiple‐ choice items, one correct Higher score indicates more knowledge |

0.956 |

| Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)c ) | 10 | 0‐10 |

10‐point scale (0=None to 10=Worst possible) |

|

|

Sense of Security (SEC‐P)d

)

Interaction Identity Mastery |

15 8 4 3 |

15‐90 8‐48 4‐24 3‐18 |

6‐point Likert scale (1=Never to 6= Always) Higher score indicates more sense of security |

0.896 |

| Health status (EQ‐VAS)e ) | 1 | 0‐100 |

Visual analogue scale Higher score indicates better health status |

|

|

The Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)f

)

Clinical Summary Score Overall Summary Score Domains: Physical limitation Symptoms Social limitation Self‐efficacy Quality of life |

23 13 20 6 8 4 2 3 |

0‐100 |

Likert scale with 5 ‐ 7 options Scales are transformed to a range from 0‐100. Higher scores denote better health status |

0.913 0.941 0.871 0.874 0.865 0.604 0.776 |

|

Symptoms of anxiety and depression (HAD‐S)g

)

Anxiety Depression |

14 7 7 |

0‐21 0‐7 0‐7 |

4‐point Likert scale Higher scores indicate more symptoms |

0.860 0.821 |

European Heart Failure Self‐care Scale EHFScBs‐12 (Jaarsma et al.23).

Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale (van der Wal et al.24).

Edmonton Symptom Assessment System ESAS (Richardson and Jones25).

Sense of Security in Care – ‘Patients' evaluation’ (SEC‐P) (Krevers and Milberg26).

The health‐related quality of life aspects—visual analogue scale (EQ‐5Dvas) (Brooks27).

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond and Snaith30).

To characterize the sample, participants answered questions about their education, employment, marital status, number of household members and income of the household, and changes they had experienced in access to health care and medical costs since the national economic crisis in 2008.

From electronic patient records, the following clinical data were extracted: previous or current diseases, performed cardiac procedures, biometrics and pharmacological treatment (medications), and age, sex, and whether or not duration of HF was longer than 6 months.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics [mean and standard deviation, frequencies, and proportions (%)] were used to describe the sample characteristics and the following PROMs: knowledge scores [Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale (DHFKS)], self‐care [European Heart Failure Self‐Care Behaviour scale (EHFScBs)], sense of security [Sense of Security in Care (SEC)], symptoms of anxiety and depression [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)], quality of life/health status [Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), EQ‐5D visual analogue scale (EQ‐5Dvas)], and symptoms [Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS)].

Low self‐care on the EHFScBs was defined as not agreeing with the statement (scores 3, 4, and 5). The consulting behaviour dimension is the mean of four items on seeking help from health care providers in case of problems.32 The KCCQ's overall summary score (OSS) was divided into quartiles to determine health status. Scores of <25 indicate the lowest QoL/health status, scores between 25 and 49 indicate poor QoL/health status, scores between 50 and 74 indicate fair QoL/health status, and scores > 75 represent good QoL/health status.33 Scores of the HADS were divided with a cut‐off point of >7 to distinguish between patients with symptoms suggestive of anxiety or depression.30

Independent t‐test, Mann–Whitney U‐test, and χ 2 test were used as appropriate, based on normality of data distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), to compare PROMs between those patients whose costs for health care had changed and not changed since the autumn of 2008 and those with high and low income. Data on self‐care and the OSS of the KCCQ were normally distributed according to the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test while data on other PROMs were not.

To prepare data on household income for analysis, the centre value of each response option was chosen and divided by the members of the household. The income per person was categorized into low income [1 = less than 200 000 Icelandic króna (ISK) or €1300] (43.4% of sample) and high income (2 = 200 000 ISK and more). The ISK values were converted to euro by using the currency rate at the time of data collection. These variables were used to assess the relationship between income and PROMs.

Missing data were not imputed, and cases were deleted listwise. The level of statistical significance was set at <0.05. The software package IBM SPSS‐21 statistics was used for analysis (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

The results are presented in concordance with the model of PROMs (Figure 1 ).

Characteristics of the individual

Of 227 eligible patients, 124 accepted the invitation to participate in the study (55% response rate). Reminder phone calls were made, and five of the non‐participating patients were found to be hospitalized and 16 could not be reached. The mean age and sex of non‐participants did not differ from those of the participants of the study.

The characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 2. Their mean age was 73 years (±14.9), and 69% were male. In total, 29% had basic education (9 years) or less, 64% were retired, and 15% were on disability pension. Most patients (88%) lived in urban areas in and around the capital, within 50 km of the hospital.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics (n = 124)

| Age in years (mean) (±SD) | 73 (±14.9) |

| Gender (n = 124) | |

| Male | 69% |

| Education (n = 118) | |

| Basic education or less (≤9 years) | 29% |

| Started or completed college | 49% |

| Started or completed university | 22% |

| Employment status (n = 120) | |

| Employed (by self or others) | 19% |

| Retired | 64% |

| Disability pension | 15% |

| Other | 2% |

| Marital status (n = 121) | |

| Married/cohabiting | 64% |

| Divorced/widowed | 30% |

| Single | 6% |

| Self‐care (n = 115), total score | M 28.6 ± 7.7 |

| Low self‐care (score 3–5) | |

| Exercise | 53% |

| Weight monitoring | 50% |

| Sodium restriction | 48% |

| Flu shot | 33% |

| Taking medication | 0% |

| Heart failure knowledge (n = 124) | M 11.6 ± 3.1 |

| Answered correctly | |

| Reasons for HF | 77% |

| Exercise in HF | 68% |

| How often should weigh themselves | 67% |

| What to do about thirst | 45% |

| What to do in case of sudden worsening | 38% |

| Sense of security (n = 123) | |

| Total score | M 5.1 ± 0.9 |

| Care | M 5.2 ± 0.9 |

| Mastery | M 5.0 ± 0.9 |

| Identity | M 5.1 ± 0.8 |

The mean score of self‐care measured with the EHFScBs was 28.6 (±7.7), and consulting behaviour was 11.0 (±4.6). Self‐care was low in exercising (53%) and weight monitoring (50%) but optimal in taking medication (100% adherence).

Heart failure‐specific knowledge, measured with the DHFKS, was 11.6 (±3.1), 10 questions were answered correctly by >80% of patients, and the lowest level of knowledge was found regarding sudden worsening of symptoms (38% answered correctly) and what to do when thirsty (45%).

Self‐efficacy (a measure of how well a patient can manage her or his care and find answers and help), measured with the KCCQ, was 85.8 (±18.6), and mastery and identity as measured with the SEC‐P were 5.0 (±0.9) and 5.1 (±0.8), respectively. Over 70% of patients scored 5–6 on the total SEC‐P scale. Lower scores were found in the items ‘Do you have enough say over your healthcare’ (68%) and ‘Can you do what is most important to you in your daily life’ (59%).

Biological function

Health status as reflected in biological function and medical treatment is presented in Table 3. Most of the patients (96%) had had HF for 6 months or longer. The most common co‐morbidities were atrial fibrillation (62%) and ischaemic heart disease (61%). A quarter had HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a quarter had HF with mid‐range ejection fraction (HFmrEF), and half of the participants had HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF).

Table 3.

Biological function and treatment (n = 124)

| Co‐morbidities | |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | 62% |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 61% |

| Heart valve disease | 42% |

| Hypertension | 41% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27% |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | 24% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 22% |

| Previous invasive cardiac treatment | |

| Device therapy | 40% |

| Pacemaker | 22% |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy | 9% |

| Implantable cardioverter defibrillator | 9% |

| Revascularization | 36% |

| PCI | 18% |

| PCI and CABG | 13% |

| CABG | 5% |

| Valve surgery | 9% |

| Left ventricular function | |

| HFpEF | 25% |

| HFmrEF | 25% |

| HFrEF | 50% |

| Medical treatment | |

| ARBs/ACE‐I | 79% |

| Beta‐blocker | 92% |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists | 41% |

| Diuretics | 94% |

| Digitalis | 24% |

| Number of other drugs | 1–14 |

ACE‐I, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitor; ARBs, Angiotensin II receptor blockers; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; HFmrEF, heart failure with mid‐range EF; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved EF; HFREF, heart failure with reduced EF; PCI, Percutaneous coronary intervention.

A total of 46% of patients had undergone revascularization with either cardiac bypass or percutaneous coronary intervention, 14% had undergone valve surgery, and 64% had implanted devices.

Overall, patients were on guideline‐advised HF medication with 92% on beta‐blockers and 79% on angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and/or angiotensin receptor blockers.

Symptoms

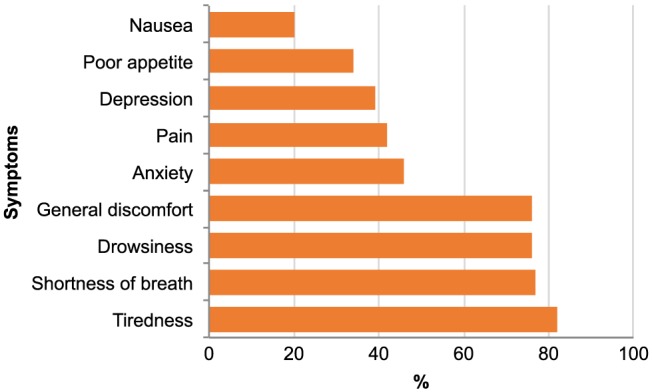

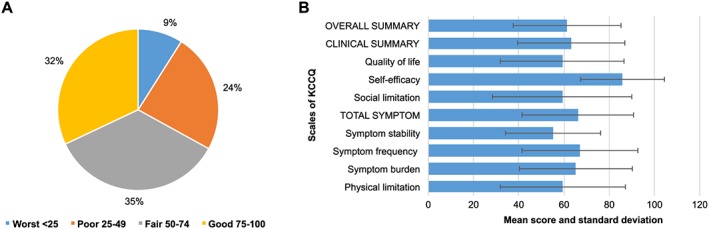

Patients reported a median (±SD) prevalence of 5 (range 0–9) symptoms out of the nine asked about in the ESAS scale. The most common symptoms were tiredness (82%) and shortness of breath (77%) (Figure 2 ). The total symptom score (a combined measure of the symptom scales), measured with the KCCQ, was 66.1 (±24.6), and on the KCCQ subscales, the symptom stability score (a measure of whether a patient's symptoms are changing over time) was the lowest 55.1(±21.1), while symptom frequency (a measure of how often a patient has symptoms) was 67.1(±25.7) and symptom burden (a measure of what the impact of symptoms are on the patient's well‐being) was 65.2 (±25.0) (Figure 3 ). The mean scores of symptoms of anxiety and depression measured with the HADS were 3.7 (±3.8) and 4.5 (±3.8), respectively. Of the total sample, 12% and 18% had significant symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of physical and psychological symptoms on Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (n = 121).

Figure 3.

Health‐related quality of life (KCCQ). (A) Overall summary score divided into quartiles (KCCQ) (n = 124). (B) Scores of the KCCQ scales (n = 124). KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire.

Functional status

Most patients were in New York Heart Association functional class II (37%) or III (55%), 6% in class I, and 3% in class IV. Their functional status as measured with the physical limitation score (a measure of how much a patient's condition is hampering his or her ability to do what he or she wants to do) of the KCCQ was 59.5 (±27.6) (Figure 3 ).

General health perception and overall quality of life

Patients rated their overall health on average as 65.5 (±22.8) with the EQ‐5Dvas. Quality of life score on KCCQ (a measure of the overall impact of a patient's condition on a patient's interpersonal relationships and state of mind) was 59.3 (±27.4), and the OSS on KCCQ (a combined measure of all scales) was 61.3 (±23.9) with 67% of patients reporting scores > 50, thus indicating fair or good QoL/health status (Figure 3 ).

Characteristics of the environment

Income and household members

The monthly income per person was low, or <€1300 for 43% of the patients, and the total monthly income of the household before taxes was <€1950 for 37% of the patients and between €1950 and €3900 for 47% of patients, while 16% had a household income > €3900. Around one‐third of patients (36%) lived on their own, 50% lived with another person, and 14% lived in a household with three or more persons (n = 117).

Social support

Sense of security as it relates to care interaction and measured with the SEC‐P (interaction) was 5.2 (±0.9), and patients scored on average 59.2 (±30.9) on the KCCQ social limitation scale.

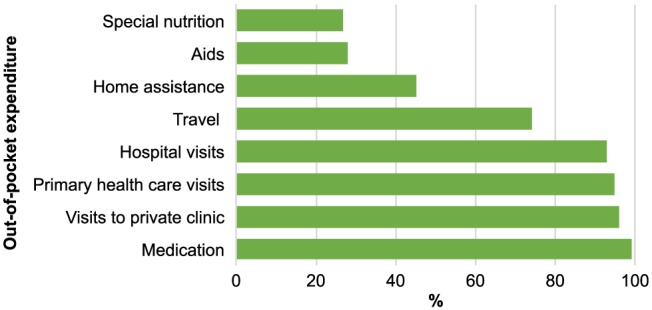

Cost and access to health care

The cost of health care had changed for 71% of the participants since the economic crisis in 2008, and the most common explanations given for increased out‐of‐pocket costs were need for more health care services, increased medication costs, and payment for hospital and clinic visits. On average, patients paid for 5.5 (±1.4) health care‐related items. The most common expenses were for medication (99%), appointments at private medical clinics (96%) and health care centres (95%), and hospital services (93%) (Figure 4 ).

Figure 4.

Out‐of‐pocket expenditure (n = 124).

To make an appointment for necessary health care was found easy or very easy by 69% of the participants, and for 92%, it took less than an hour to travel to the most commonly used health care service. However, 22% said that it was difficult or almost impossible to make an appointment with their general practitioner (GP), and 5% did not have a GP (Table 4).

Table 4.

Access to health care (n = 119)

| How easy/difficult is it to make an appointment for necessary health care? | |

| Very easy | 31% |

| Easy | 38% |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 21% |

| Difficult | 8% |

| Almost impossible | 0% |

| Don't know | 2% |

| How easy/difficult is it to make an appointment with a general practitioner? | |

| Very easy | 22% |

| Easy | 26% |

| Neither easy nor difficult | 25% |

| Difficult | 19% |

| Almost impossible | 3% |

| I don't have a GP | 5% |

Relationship between health status and socio‐economic factors

There was no significant difference in any of the PROMs (self‐care, sense of security, knowledge, symptoms of anxiety and depression, health status, KCCQ clinical summary score, or KCCQ OSS) between those patients who perceived they had experienced changes in out‐of‐pocket costs since autumn 2008 and those who had not experienced such changes (P > 0.05).

Similarly, no significant difference was found in PROMs between patients with lower and higher income (P > 0.05). However, there was a difference in HF knowledge; patients in the low‐income groups had less knowledge than those with higher incomes (P = 0.016).

No significant difference was found in PROMs between those patients who lived alone and those living with others, nor between those who were married/cohabiting and those who were single, widowed, or divorced.

Discussion

The uniqueness of the study is the fact that it gives a comprehensive picture of the complex profile of HF patients in one country. The sample size can be estimated to account for ~2.50% of the population of Icelandic HF patients, which is considerably more than is common in similar survey studies. We described the health of HF patients who received care at a multidisciplinary outpatient clinic in the aftermath of the national economic crisis. In spite of the consequences of the economic crisis on health care, the results seem to indicate that patients managed to prioritize and protect their health.

The participants in our study were quite symptomatic, with a median of five symptoms on the ESAS scale and typical symptoms of chronic HF being the most common symptoms. Only one other study was found using ESAS in outpatients with advanced or terminal HF, and participants in that Italian study were even more symptomatic, with shortness of breath being present in all participants compared with 77% in our study.34 However, participants' symptoms of anxiety and depression, measured with HADS, were comparable for depression and better for anxiety than reports from Danish outpatients.35 A report from Ireland, a country that was also hit hard by the economic crisis, reported a considerably higher prevalence of both depression and anxiety.36

Patient‐reported health status, as measured with the EQ‐5Dvas, was similar (mean 66) to Swedish patients' health status from a large Swedish registry study (mean 63) using data from 2008–13.37 When comparing the health status of our Icelandic HF patients with the health status of similar outpatient populations before and after the economic crisis, the picture is complex. The health status of our patients, as measured with the KCCQ, was lower than that indicated in results from both international studies38, 39 and an Italian study using data collected in 2003–0540 but almost identical to that of an American multicentre study published in 2006.41 In a pilot study on American HF patients after the crisis, patients reported better health status than did our population42 while a Belgian HF population on the other hand showed considerably worse outcomes43 (Table 5). We do not have Icelandic measures of health status of HF patients before the economic crisis, but it could be speculated that the crisis may have affected patients in the European countries with their universal health care coverage harder than in patients in the USA with their private health care coverage. Several European countries such as Ireland, Spain, Greece, Italy, and Belgium were also hit hard by the crisis and are still considered countries in recession.

Table 5.

Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire overall summary scores in comparable studies of outpatient heart failure patients

| Study | Heidenreich et al.10 | Chan et al.38 | Network of Nurses of GISSI‐HF and Di Giulio40 | Sawadogo et al.43 | ICE‐HF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | USA | International | Italy | Belgium | Iceland |

| Year of data collection | Not reported | 1999–2001 | 2003–2005 | 2008–2010 | 2014 |

| KCCQ OSS quartiles | |||||

| Worst < 25 | 9% | 3.9% | 3.1% | 22.3% | 8.9% |

| Poor 25–49 | 25% | 17.3% | 12.6% | 31.5% | 24.2% |

| Fair 50–74 | 34% | 33.6% | 28.2% | 27.3% | 34.6% |

| Good 75–100 | 33% | 45.2% | 56.1% | 18.9% | 32.3% |

KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; OSS, overall summary score.

Patients in this study may have managed their health situation better despite poor access to primary health care because they had good access to the outpatient clinic and to health care in general. This is supported by high scores on sense of security, where the mean score was of 5.1 out of 6.0 possible. This is the first time that sense of security has been measured with this instrument in HF patients, but their total score was similar to that of samples of palliative cancer patients and outpatient geriatric patients.26, 44 Self‐care of the patients in this study was found to be similar to that of patients in an international study including 15 countries,45 and their knowledge about HF was comparable with what has been described in previous studies.46, 47 However, it is of concern that only 38% of the patients knew what to do in the event that their condition worsened. This may be due to poor knowledge and also confusion regarding access to health care. At the time of the study, acute cases were referred to hospital emergency departments, which varied their services for cardiac patients between weekends and weekdays. This may have caused uncertainty for patients about the first point of contact when they needed help. Approximately a quarter of the respondents reported that they had experienced a change in access to health care since 2008. While few patients stated they had experienced improved access after having been diagnosed with HF, most described their access as worse. People's lack of access to primary health care in particular was also evident in this study, with only 48% of patients finding it easy or very easy to make an appointment with their GP. It is important to explain that the health care system in Iceland was suffering very tight budgets in the years before 2008, and from 2000, constant cutbacks were implemented. At the same time, a long‐standing shortage of GPs in primary health care continued and only became worse after the crisis, leading to poor access to the cheapest services. While on average there were 80 GPs per 100 000 inhabitants within the European Union countries in 2014, Iceland only had 57.48 This situation makes it difficult to refer acute cases to the health care centres, and the emergency department is subsequently pressured with patients whose first visit should be elsewhere. This might have added to the patients' uncertainty about the first point of contact when they needed to seek help.

Increased health care costs, especially medication costs, were reported by most patients. With the fall of the real exchange rate by 36% between 2007 and 2009,49 the prices of all imported goods, including medication, rose significantly. Out‐of‐pocket medical expenditure as a proportion of final household consumption was higher in Iceland (2.9%) in the year 2013 (or the nearest year) than the average for the European Union countries (2.3%).50 A new policy on cost sharing, implemented in 2013, meant a 5.6% increase in out‐of‐pocket costs for general health care and a 3.9% increase in medication costs (Ministry of Welfare 2013). To protect the chronically ill, the government implemented counteractions, which may have worked, as medication adherence was reported to be 100% in this study, which is higher than has been measured internationally.45 However, in 2015, patients paid 47% more for an echocardiogram, 52% more for a visit to a cardiologist, and 92% more for a blood test (LUH, Division of Economics, personal communication) than they did before the crisis, which is of concern. In a study on the impact of the economic crisis in Iceland on public health behaviour, price increases were found to explain most of the changes in behaviour such as consumption of fruits and vegetables, smoking, and heavy drinking.51

In spite of the crisis and severe cutbacks in hospital services, attempts have been made to protect and improve the services of the HF outpatient clinic. These seem to have succeeded in protecting patients and ensuring good access. Another influencing factor may be that the Icelandic health care system does not use gatekeepers. This means that patients have unlimited access to medical specialists in private practice with partial coverage from the state, and this may explain why patients are rather content with access to health care in general. It seems that this patient population, who has access to the HF multidisciplinary clinic, is managing quite well in spite of the increased costs, and that improved services are covering their needs for health care contact.

Limitation

This cross‐sectional study gives a profile of the HF patient population in a country hit hard by the economic crisis of 2008. The study does not attempt to explain causality or associations of variables, as no measures were available on the patient population's profile before the crisis. It therefore remains unknown if the patients' PROMs were the same before, or better and declined after the crisis. The response rate of 55%, although suboptimal, can be regarded as acceptable for a survey in this patient population. The sample was chosen from a registry of patients cared for by a multidisciplinary outpatient HF clinic, and the results cannot be generalized beyond that population. Most of the participants live in the area of the country's capital, and it remains unknown how they compare with other HF patients in the country. Finally, we do not have information on how long patients had suffered from HF, as some may have been diagnosed after 2008; therefore, not only the crisis but also their diagnosis may have affected both access to and cost of health care.

Conclusions

Six years after the national economic crisis of 2008, a large proportion of patients with HF have low income and high health care expenditure. They also report insufficient access to GPs. Measures to protect important hospital services such as the HF clinic are therefore vital and seem to have helped patients to manage their health. It is of great importance that national health policies serve to protect access and affordable health care services for this vulnerable patient population.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by Landspítali University Hospital Research Fund, Landspítali, National University Hospital of Iceland; Icelandic Nurses' Association Research Fund; the Maria Finnsdottir Research Fund; and the Heart Failure Association of the ESC Nursing Training Fellowship.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Helga Jónsdóttir, Faculty of Nursing, University of Iceland; Inga S. Þráinsdóttir, MD; and Elín J. G. Hafsteinsdóttir, PhD, RN, and health economist, Landspítali, the National University Hospital of Iceland.

Ketilsdottir, A. , Ingadottir, B. , and Jaarsma, T. (2019) Self‐reported health and quality of life outcomes of heart failure patients in the aftermath of a national economic crisis: a cross‐sectional study. ESC Heart Failure, 6: 111–121. 10.1002/ehf2.12369.

This study was performed at Landspítali, National University Hospital of Iceland.

References

- 1. Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González‐Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, Van Der Meer P. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 2016; 37: 2129–2200.27206819 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cowie M, Anker S, Cleland J, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Jaarsma T, Jourdain P, Knight E, Massie B, Ponikowski P, Lopez‐Sendón J. Improving care for patients with acute heart failure before, during and after hospitalisation. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1: 110–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Al Habib KF, Cowie MR, Force TL, Hu S, Jaarsma T, Krum H, Rastogi V, Rohde LE, Samal UC, Shimokawa H, Budi Siswanto B, Sliwa FG. Heart failure: preventing disease and death worldwide. ESC Heart Fail 2014; 1: 4–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP. The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2014; 171: 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Saitoh M, Santos MR, Emami A, Ishida J, Ebner N, Valentova M, Bekfani T, Sandek A, Lainscak M, Doehner W, Anker SD, Haehling S. Anorexia, functional capacity, and clinical outcome in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the Studies Investigating Co‐morbidities Aggravating Heart Failure (SICA‐HF). ESC Hear Fail 2017; 4: 448–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessing D, Denollet J, Widdershoven J, Kupper N. Self‐care and health‐related quality of life in chronic heart failure: a longitudinal analysis. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2017; 16: 605–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. OECD . Health at a Glance 2013: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2013. 10.1787/health_glance-2013-en. (28 March 2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. OECD . OECD Health Statistics 2015 [Internet]. 2015. http://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=HEALTH_STAT (28 March 2018).

- 9. Guðjónsdóttir GR, Kristjánsson M, Ólafsson Ö, Arnar DO, Getz L, Sigurðsson JÁ, Guðmundsson S, Valdimarsdóttir U. Immediate surge in female visits to the cardiac emergency department following the economic collapse in Iceland: an observational study. Emerg Med J 2012; 29: 694–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stuckler D, Meissner C, King L. Can a bank crisis break your heart? Global Health 2008; 4: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas R, Huntley A, Mann M, Huws D, Paranjothy S, Elwyn G, Purdy S. Specialist clinics for reducing emergency admissions in patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Heart 2013; 99: 233–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maru S, Byrnes J, Carrington MJ, Stewart S, Scuffham PA. Systematic review of trial‐based analyses reporting the economic impact of heart failure management programs compared with usual care. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016; 15: 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Spertus J. Barriers to the Use of Patient‐Reported Outcomes in Clinical Care. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014; 7: 2–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thompson DR, Ski CF, Garside J, Astin F. A review of health‐related quality of life patient‐reported outcome measures in cardiovascular nursing. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2016; 15: 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patrick DL, Guyatt GH, Acquadro C. Patient‐reported outcomes In Higgins J., Green S., eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [Internet]. Version 5. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. www.cochrane‐handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health‐related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995; 273: 59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual model of health‐related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh 2005; 37: 336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bakas T, McLennon SM, Carpenter JS, Buelow JM, Otte JL, Hanna KM, Ellett ML, Hadler KA, Welch JL. Systematic review of health‐related quality of life. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10: 134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shively M, Wilson I. Health‐related quality of life outcomes in heart failure: a conceptual model In Moser D. K., Riegel B., eds. Improving Outcomes in Heart Failure: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Gaithersburg: AN Aspen Publication; 2001. p 18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 20. United Nations Development Programme . Human Development Index and Its Components. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/table‐1‐human‐development‐index‐and‐its‐components (28 March 2018).

- 21. Asgeirsdottir TL. The Icelandic health care system In Magnussen J., Vrangbaek K., Saltman R. B., eds. Nordic Health Care Systems: Recent Reforms and Current Policy Challenges. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2009. p 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- 22. World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013; 310: 2191–2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jaarsma T, Årestedt KF, Mårtensson J, Dracup K, Strömberg A. The European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour scale revised into a nine‐item scale (EHFScB‐9): a reliable and valid international instrument. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11: 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, van Veldhuisen DJ. Development and testing of the Dutch Heart Failure Knowledge Scale. EurJ Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 4: 273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Richardson LA, Jones GW. A review of the reliability and validity of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System. Curr Oncol 2009; 16: 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Krevers B, Milberg A. The instrument ‘Sense of Security in Care—Patients' Evaluation’: its development and presentation. Psychooncology 2014; 23: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 2000; 37: 53–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 35: 1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Patel H, Ekman I, Spertus JA, Wasserman SM, Persson LO. Psychometric properties of a Swedish version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in a Chronic Heart Failure population. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2008; 7: 214–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zigmond S, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale . Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jonsdottir T, Jonsdottir H, Lindal E, Oskarsson GK, Gunnarsdottir S. Predictors for chronic pain‐related health care utilization: a cross‐sectional nationwide study in Iceland. Health Expect 2015; 18: 2704–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vellone E, Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, Fida R, Arestedt K, Rocco G, Cocchieri A, Alvaro R. The European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour Scale: new insights into factorial structure, reliability, precision and scoring procedure. Patient Educ Couns 2014; 94: 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Soto GE, Jones P, Weintraub WS, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Prognostic value of health status in patients with heart failure after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2004; 110: 546–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Opasich C, Gualco A, De Feo S, Barbieri M, Cioffi G, Giardini A, Majani G. Physical and emotional symptom burden of patients with end‐stage heart failure: what to measure, how and why. J Cardiovasc Med 2008; 9: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brouwers C, Spindler H, Larsen ML, Eiskær H, Videbæk L, Pedersen MS, Aagard B, Pedersen SS. Association between psychological measures and brain natriuretic peptide in heart failure patients. Scand Cardiovasc J 2012; 46: 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Morgan K, Villiers‐Tuthill A, Barker M, McGee H. The contribution of illness perception to psychological distress in heart failure patients. BMC Psychol 2014; 2: 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lawson CA, Solis‐Trapala I, Dahlstrom U, Mamas M, Jaarsma T, Kadam UT, Stromberg A. Comorbidity health pathways in heart failure patients: a sequences‐of‐regressions analysis using cross‐sectional data from 10,575 patients in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. PLoS Med 2018; 15: e1002540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chan PS, Soto G, Jones PG, Nallamothu BK, Zhang Z, Weintraub WS, Spertus JA. Patient health status and costs in heart failure. Insights from the eplerenone post‐acute myocardial infarction heart failure efficacy and survival study (EPHESUS). Circulation 2009; 119: 398–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Flynn KE, Piña IL, Whellan DJ, Lin L, J A B, Ellis SJ, Fine LJ, Howlett JG, Keteyian SJ, Kitzman DW, Kraus WE, Miller NH, K a S, J a S, O'Connor CM, Weinfurt KP. Effects of exercise training on health status in patients with chronic heart failure: HF‐ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009; 30: 1451–1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Network of Nurses of GISSI‐HF , Di Giulio P. Should patients perception of health status be integrated in the prognostic assessment of heart failure patients? A prospective study. Qual Life Res 2014; 23: 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Heidenreich PA, Spertus JA, Jones PG, Weintraub WS, Rumsfeld JS, Rathore SS, Peterson ED, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM, Havranek EP, Conard MW, Williams RE. Health status identifies heart failure outpatients at risk for hospitalization or death. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006; 47: 752–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sauser K, Spertus JA, Pierchala L, Davis E, Pang PS. Quality of life assessment for acute heart failure patients from emergency department presentation through 30 days after discharge: a pilot study with the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire. J Card Fail 2014; 20: 18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sawadogo K, Ambroise J, Vercauteren S, Castadot M, Vanhalewyn M, Col J, Robert A. Interaction between the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire and the Pocock's clinical score in predicting heart failure outcomes. Qual Life Res 2015; 25: 1245–1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ekdahl AW, Wirehn A‐B, Alwin J, Jaarsma T, Unosson M, Husberg M, Eckerblad J, Milberg A, Krevers B, Carlsson P. Costs and Effects of an Ambulatory Geriatric Unit (the AGe‐FIT Study): a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015; 16: 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, Ben Gal T, Cameron J, Driscoll A, Duengen HD, Inkrot S, Huang TY, Huyen NN, Kato N, Koberich S, Lupon J, Moser DK, Pulignano G, Rabelo ER, Suwanno J, Thompson DR, Vellone E, Alvaro R, Yu D, Riegel B. Comparison of self‐care behaviors of heart failure patients in 15 countries worldwide. Patient Educ Couns 2013; 92: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Davis KK, Mintzer M, Dennison Himmelfarb CR, Hayat MJ, Rotman S, Allen J. Targeted intervention improves knowledge but not self‐care or readmissions in heart failure patients with mild cognitive impairment. Eur J Heart Fail 2012; 14: 1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. van der Wal MHL, Jaarsma T, Moser DK, Veeger NJGM, Van Gilst WH, Van Veldhuisen DJ. Compliance in heart failure patients: the importance of knowledge and beliefs. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization (Europe) . European Health Information Gateway. https://gateway.euro.who.int/en/indicators/hfa_507‐5290‐general‐practitioners‐pp‐per‐100‐000/visualizations/#id=19583&tab=table (23 July 2018).

- 49. Benediktsdottir S, Danielsson J, Zoega G. Lessons from a collapse of a financial system. Econ Policy 2011; 26: 183–235. [Google Scholar]

- 50. OECD . Out‐of‐pocket medical expenditure In Health at a Glance: Europe 2016: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Paris: OECD Publishing: 10.1787/health_glance_eur-2016-52-en.OECD. Health at a glance 2016: OECD Indicators (23 July 2018). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Asgeirsdottir TL, Corman H, Noonan K, Olafsdottir T, Reichman NE. Was the economic crisis of 2008 good for Icelanders? Impact on health behaviors. Econ Hum Biol 2014; 13: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]