Abstract

Background: The BRAFV600E mutation is the most common somatic mutation in thyroid cancer. The mechanism associated with BRAF-mutant tumor aggressiveness remains unclear. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) is highly expressed in aggressive thyroid cancers, and involved in cancer metastasis. The objective was to determine whether LOX mediates the effect of the activated MAPK pathway in thyroid cancer.

Methods: The prognostic value of LOX and its association with mutated BRAF was analyzed in The Cancer Genome Atlas and an independent cohort. Inhibition of mutant BRAF and the MAPK pathway, and overexpression of mutant BRAF and mouse models of BRAFV600E were used to test the effect on LOX expression.

Results: In The Cancer Genome Atlas cohort, LOX expression was higher in BRAF-mutant tumors compared to wild-type tumors (p < 0.0001). Patients with BRAF-mutant tumors with high LOX expression had a shorter disease-free survival (p = 0.03) compared to patients with a BRAF mutation and the low LOX group. In the independent cohort, a significant positive correlation between LOX and percentage of BRAF mutated cells was found. The independent cohort confirmed high LOX expression to be associated with a shorter disease-free survival (p = 0.01). Inhibition of BRAFV600E and MEK decreased LOX expression. Conversely, overexpression of mutant BRAF increased LOX expression. The mice with thyroid-specific expression of BRAFV600E showed strong LOX and p-ERK expression in tumor tissue. Inhibition of BRAFV600E in transgenic and orthotopic mouse models significantly reduced the tumor burden as well as LOX and p-ERK expression.

Conclusions: The data suggest that BRAFV600E tumors with high LOX expression are associated with more aggressive disease. The biological underpinnings of the clinical findings were confirmed by showing that BRAF and the MAPK pathway regulate LOX expression.

Keywords: LOX, BRAF, survival, recurrence

Introduction

Thyroid cancer, the most common endocrine malignancy shows divergent behavior based on the histologic subtype, ranging from near-normal life expectancy in patients with papillary microcarcinomas to a lethal course in patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer (1,2). Despite diverse disease progression and outcomes for patients with papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), molecular markers predictive of tumor behavior useful for clinical management remain relatively scarce and an active area of investigation.

The most common mutation in thyroid cancer is BRAFV600E, which is present in approximately 40% of patients with PTC (3–5). BRAFV600E constitutively activates a serine/threonine kinase and initiates malignant transformation by activating the MAPK pathway (6,7). Other common thyroid cancer mutations (RAS, RET rearrangements) also constitutively activate the MAPK pathway. Although most studies have observed an association between the BRAFV600E mutation and more aggressive clinicopathologic features (8–11), its usefulness as a prognostic marker remains controversial because of its prevalence in incidental or microscopic PTC (8,12–14). Therefore, it remains unclear whether the presence of mutation alone should affect the treatment of thyroid cancer patients. Coexisting BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations are associated with higher mortality but occur in only 3–6% of patients with PTC (15,16).

Lysyl oxidase (LOX) is a copper-dependent amine oxidase that plays a critical role in the biogenesis of connective tissue matrices by cross-linking collagen and elastin (17). Increased LOX expression has been associated with cancer aggressiveness and metastasis (18–21). LOX is highly expressed in aggressive thyroid tumors and is involved in progression and metastasis. High expression of LOX is associated with a higher mortality rate (22,23). Furthermore, LOX upregulation is associated with lower disease-free survival (DFS) in transgenic mice with BRAFV600E and PTEN inactivating mutations (24).

The objectives of this study were to assess the potential of BRAF and LOX as markers of disease aggressiveness in thyroid cancer and to characterize the biological interplay and underpinning of BRAF and LOX in thyroid cancer aggressiveness. It was found that BRAFV600E-mutant tumors are associated with higher LOX expression and more aggressive disease than BRAFV600E-mutant only or wild-type tumors, and that BRAFV600E and the MAPK pathway regulate LOX expression.

Methods

Tissue samples and patient information

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) thyroid cancer cohort (THCA) and a cohort from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) were utilized to explore the association between LOX and BRAF mutations. All patients participated in a clinical protocol for tumor tissue procurement after providing written informed consent.

Patient demographics, clinical information, and tissue specimens from the NIH were prospectively collected under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board protocol (NCT01005654) after obtaining written informed consent. Thyroid tissue was procured at the time of surgical resection, snap-frozen, and stored at −80°C. Slides for each tumor stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) were reviewed by a pathologist to confirm the diagnosis and to ensure tumor nuclei content of >80% in the tissue specimen.

Cell lines and drug treatment

The TPC-1 cell line (originated from PTC) was provided by Dr. Nabuo Satoh (Cancer Institute of Kananzawa University, Osaka, Japan), and the FTC-133 cell line was provided by Dr. Peter Goretzki (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). The 8505C ATC cell line (BRAFV600E, TP53, EGFR, PIK3R1, and PIK3R2 mutations) was obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (Salisbury, United Kingdom) (25). The THJ-16T (TP53, RB, and PIKCA mutations) and THJ-19T (RB mutations) were kindly provided by Dr. John A. Copland (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL) (26). The SW1736 cell line (BRAFV600E and TP53) and PIK3CB cell line was purchased from Cell Lines Service (CLS; Eppelheim, Baden-Württemberg, Germany). The BCPAP papillary thyroid cancer cell line (BRAFV600E and TP53 mutations) was obtained from the Leibniz Institute DSMZ (Braunschweig, Lower Saxony, Germany) (27). All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with D-glucose (4500 mg/L), L-glutamine (2 mM), and sodium pyruvate (110 mg/L), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (10,000 IU/mL), streptomycin (10,000 IU/mL), and fungizone (250 mg/mL), in a standard humidified incubator at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. All cell lines were used at early passages and authenticated by short tandem repeat assay.

PLX4720 was used to inhibit BRAFV600E, and selumetinib (MEK inhibitor) and U0126 (MEK inhibitor) were used to inhibit the MAPK pathway. All compounds were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Selleck Chemicals, Houston, TX). All experiments were performed at least three times. Additional information is provided in the Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/thy).

RNA, DNA extraction, and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines by using an RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA yield was determined using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Gene expression levels were measured using specific primers and probes. Briefly, 500–1000 ng of total RNA was reverse transcribed using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (cat no. 4374967; Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the resulting cDNA was diluted and amplified according to the manufacturer's instructions. Four housekeeping genes were used as an endogenous control (GAPDH, RPLPO, HPRT1, and actin beta). Gene expression levels were calculated using QuantStudio software (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Genomic DNA extraction was performed using a QIAamp DNA mini kit (Qiagen), and DNA was quantified on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Bidirectional Sanger sequencing for the detection of BRAF mutations was performed using purified polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products (PCR purification kit; Qiagen). PCR reactions were performed in 50 μL containing DNA, specific reverse and forward primers, and High-Fidelity PCR master mix (Qiagen). Sequencing results were analyzed using Chromas software (Technelysium Pty. Ltd., South Brisbane, Australia).

For the RNA and DNA isolation from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, slides stained with H&E were reviewed by a pathologist, and the tumor areas were identified and scraped from unstained slides. DNA and RNA were extracted using a QIAamp DNA FFPE kit and an RNeasy FFPE kit (Qiagen), respectively, according to the manufacturer's protocol. Extracted RNA samples were used for real-time PCR (RT-PCR), and DNA samples were used for droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). The detection of BRAFV600E by ddPCR was performed using BRAFV600E and WT BRAF for V600E primers and probes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For the detection of TERT promoter mutations, specific ddPCR probes detecting C228T and C250T and WT TERT were used (Bio-Rad Laboratories). ddPCR results were analyzed with QuantaSoft v.1.3.2 software (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated, and antigen retrieval was performed with citrate buffer in a water bath at 120°C. The sections were incubated with the anti-LOX antibody (for human tissue1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA; for mouse tissue: Cloud Clone Corp., Katy, TX) overnight at 4°C and then incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature. The slides were developed with diaminobenzidine (DAB; EnVision+ Kit system HRP [DAB]; Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and counterstained with hematoxylin. For phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), the slides were incubated with an anti p-ERK antibody overnight at 4°C (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), incubated for one hour at room temperature with the signal stain boost, and developed using DAB (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). The slides were scanned at 20 × magnification using a ScanScope XT digital slide scanner (Aperio Technologies, Leica, Buffalo Grove, IL) to create whole-slide image data files at a resolution of 0.5 μm/pixel, and they were viewed using ImageScope software (Aperio Technologies).

Mouse models

To assess the effects of BRAFV600E inhibition on LOX expression, a metastatic mouse model was utilized (28). These animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the NIH. The mice were maintained per guidelines set by the Animal Research Advisory Committee of the NIH. The 8505C-Luc cells (n = 30,000) were injected into the tail veins of Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ mice (28). Ten days after injection, the mice were treated by daily gavage with 100 mg/kg of PLX4032. For the in vivo imaging, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with 30 mg/mL of luciferin. Following anesthesia, the mice were imaged, and the images were analyzed using IVIS Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences, Hopkinton, MA).

Tissue slides from the 8505C and BCPAP orthotopic xenograft mouse model were used. Slides from the BCPAP orthotopic xenografts model were kindly provided by Dr. Carmelo Nucera (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) (29). The 8505C cells (5 × 105) were suspended in 10 μL of serum-free medium and injected to the thyroid of six-week-old severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. Twenty-eight days after cell injection, PLX4720 was given (120 mg/mL) to the treatment group. For the BCPAP mouse model, 106 cells were injected into the thyroid of 10-week-old SCID mice (29). Four weeks after injection, the mice started receiving a diet of PLX4720 (418 mg/kg) or vehicle. To assess the expression of LOX in thyroid specific BRAFV600E transgenic mouse model, LSL-BRAFV600E mice were used (30). These mice harbor a latent oncogenic BRAF knock-in allele that, following Cre-mediated recombination, results in the expression of BRAFV600E. In this model, the Cre-recombinase is under the control of a TPO promoter that is active only in thyroid cells, thus making the expression of BRAFV600E thyroid specific. All tissue slides were scanned and visualized using Aperio ImageScope v12.1.0.5029 (Leica, Wetzlar, Hesse, Germany).

Statistical analyses

For in vitro studies and gene expression analyses, a two-tailed t-test was used (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). All experiments were performed at least three times. Associations between dichotomized patient clinical characteristics were assessed using Fisher's exact test to assess the differences. DFS was measured from the surgery date to the date of recurrence or last follow-up. Persistent/recurrent disease was defined as structural incomplete treatment response (31,32). Probabilities of DFS over follow-up time were determined by the Kaplan–Meier method. Proportional hazards regression was used for estimates of hazard ratios (HRs), profile-likelihood-based confidence intervals of HRs, likelihood ratio tests of HRs in one- and two-factor models, and Wald tests of pairwise comparisons within four-factor models. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to estimate the HRs and profile likelihood-based confidence intervals of HRs. Two-tailed p-values of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

LOX expression and BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer recurrence

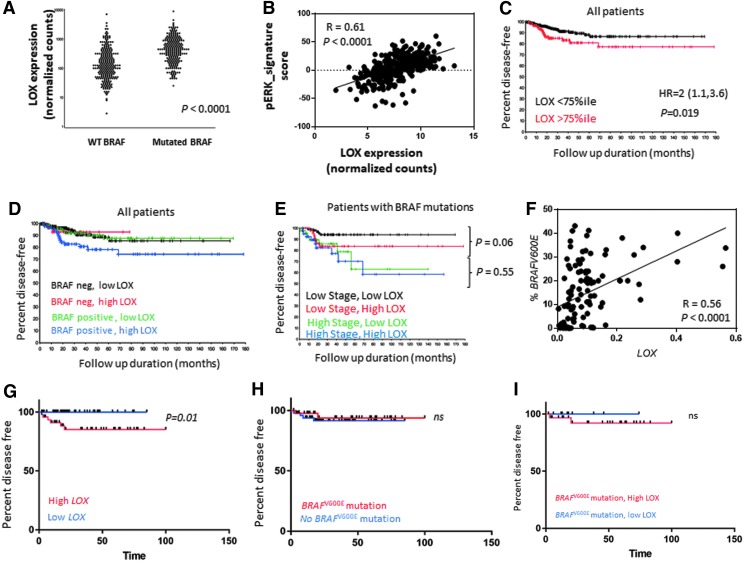

LOX mRNA expression in THCA (n = 501) database was significantly higher in BRAF-mutated tumors compared to wild-type BRAF (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1A). Consistent with the constitutively activated MAPK pathway in BRAFV600E-mutant tumors, the analysis of MAPK pathway–associated genes revealed a significant positive correlation between LOX expression and p-ERK signature (r = 0.61, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1B). Next, the prognostic value of LOX alone and in combination with BRAF status was analyzed. High LOX expression was defined as higher than the 75th percentile after dividing the data into quartiles because the highest HR was near the 75th percentile. Utilizing this cutoff, high LOX expression was associated with a higher recurrence rate (HR = 2 [CI 1.1–3.6], p = 0.019; Fig. 1C). The prognostic value of LOX in combination with the presence of a BRAF mutation status was then analyzed. Patients with a BRAF mutation and with high LOX expression had a recurrence rate 2.3 times that of patients with a BRAF mutation and low LOX expression (HR = 2.3 [CI 1.1–4.9], p = 0.03; Fig. 1D). However, LOX expression did not affect recurrence in patients with wild-type BRAF (HR = 1 [CI 0.2–3.6], p = 0.98; Fig. 1D). Moreover, mutated BRAF tumors with high LOX expression have a higher recurrence rate compared to wild-type BRAF tumors with low LOX levels (HR = 2.3 [CI 1.1–4.6], p = 0.019; Fig. 1D).

FIG. 1.

LOX expression and BRAF mutations in thyroid cancer. (A) TCGA analysis of LOX mRNA expression in mutated BRAF and WT tumors. (B) Correlation analysis of LOX and genes/proteins associated with the ERK pathway from TCGA data set (r = 0.61, p < 0.0001). (C) Estimated DFS by Kaplan–Meier analysis that uses all tumors from TCGA data set to compare the DFS of patients with high and low LOX expression levels (HR = 2 [CI 1.1–3.6], p = 0.019). (D) Estimated DFS by Kaplan–Meier analysis that uses all tumors from TCGA data set to compare the DFS of patients with high and low LOX expression levels and with and without BRAF mutation (mutated BRAF and high LOX vs. mutated BRAF and low LOX: HR = 2.3 [CI 1.1–4.9], p = 0.03; WT BRAF and high LOX vs. WT BRAF low LOX: HR = 1 [CI0.2–3.6], p = 0.9; mutated BRAF and high LOX vs. WT BRAF and low LOX: HR = 2.3 [CI 1.1–4.6], p = 0.019). (E) Estimated DFS by Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients with BRAF mutations from TCGA data set. Patients were categorized into four groups according to the overall stage and LOX expression level: low-stage high LOX versus low-stage low LOX (HR = 2.9 [CI 0.9–9.8], p = 0.06) and high-stage high LOX versus high-stage low LOX (HR = 1.4 [CI 0.5–3.8], p = 0.55). (F) Correlation analysis of LOX expression by RT-PCR and percentage of BRAFV600E mutations detected by ddPCR (r = 0.56, p < 0.0001). (G) Estimated DFS by Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients with thyroid cancer from the authors' institution comparing DFS of patients with high and low LOX expression levels determined by RT-PCR (p = 0.01). (H) Estimated DFS by Kaplan–Meier analysis of patients with thyroid cancer from the authors' institution comparing DFS of patients with BRAFV600E mutation and WT BRAF (p = 0.8). (I) Estimated DFS of patients with BRAFV600E from the authors' institution. Patients were categorized according to their LOX expression level. TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; DFS, disease-free survival; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; ddPCR, droplet digital PCR; WT, wild type.

Clinicopathologic factors associated with LOX expression and BRAF mutation status

Given the prognostic synergy of the BRAFV600E mutation and LOX expression, clinicopathologic factors were analyzed. Patients with a BRAFV600E mutation, stages I and II thyroid cancer, and high LOX expression were found to have a trend toward a shorter DFS (HR = 2.9 [CI 0.9–9.8], p = 0.06) compared to patients with a BRAFV600E mutation, stages I and II thyroid cancer, and low LOX expression (Fig. 1E). However, patients with a BRAFV600E mutation and with advanced thyroid cancer (stages III and IV) showed no difference in DFS when stratified by LOX expression level (HR = 1.40 [CI 0.5–3.8], p = 0.55; Fig. 1E). Clinical factors associated with patients with BRAF-mutated tumors and high LOX expression included increased risk of recurrence (p = 0.03), more advanced stage (p = 0.006), larger tumor size (p < 0.0001), higher rate of lymph node metastasis (p = 0.002), and extrathyroidal extension (p < 0.0001; Supplementary Table S1). A single factor analysis of clinical factors showed that advanced thyroid cancer (stages III–IV), larger tumor size (T3–T4), histology (tall-cell variant), extrathyroidal extension, and higher LOX expression were the only variables significantly associated with shorter DFS (Table 1). On multiple regression analysis, advanced thyroid cancer (stages III–IV; HR = 2.4 [CI1.3–4.3], p = 0.004) was the only independent variable associated with shorter DFS. High LOX expression (HR = 1.7 [CI 0.9–3], p = 0.1) was statistically trending toward a shorter DFS (Table 1).

Table 1.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Clinical and Histological Characteristics by Overall Survival in TCGA Cohort of Patients with Thyroid Cancer

| Single factors | Backward selection | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | HR | CI | p | HR | CI | p | ||

| BRAF | Negative | 260 | ||||||

| Positive | 232 | 1.5 | [0.8–2.6] | 0.20 | ||||

| Sex | Female | 361 | ||||||

| Male | 131 | 1.4 | [0.7–2.6] | 0.27 | ||||

| Stage | I–II | 333 | ||||||

| III–IV | 157 | 2.5 | [1.4–4.4] | 0.001 | 2.4 | [1.3–4.3] | 0.004 | |

| T stage | T1–T2 | 306 | ||||||

| T3–T4 | 184 | 2.4 | [1.3–4.3] | 0.004 | ||||

| Histology | Other | 455 | ||||||

| Tall cell | 37 | 2.5 | [1.0–5.2] | 0.05 | ||||

| LOX | ≤75th percentile | 368 | ||||||

| >75th percentile | 118 | 2.0 | [1.1–3.6] | 0.03 | 1.7 | [0.9–3.0] | 0.10 | |

| Extrathyroidal extension | No | 332 | ||||||

| Yes | 143 | 1.8 | [1.0–3.2] | 0.05 | ||||

LOX, lysyl oxidase; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval.

An independent cohort (NIH) of 109 patients with thyroid cancer (median follow-up of 32 months) was tested to confirm THCA cohort findings. Thyroid cancer tissue samples were microdissected, and LOX mRNA expression was measured (Supplementary Table S2). All tissue samples contained >85% of tumor cells. After excluding two RNA samples with low yield, LOX expression and BRAFV600E mutation analysis showed a significant positive association between LOX mRNA expression and the mutant copies of BRAFV600E (r = 0.57, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1F). After excluding seven patients with incomplete clinical information, DFS analysis was performed. In this cohort, the optimal cutoff for LOX mRNA expression was the 59th percentile ( = 0.08). Patients with high LOX expression had a shorter DFS compared to patients with low LOX expression level (p = 0.02; Fig. 1G). BRAFV600E mutation status did not affect DFS (p = 0.8; Fig. 1H). In patients with BRAF-mutated tumors and high LOX expression, there was a trend toward a shorter DFS compared to patients with BRAF-mutated tumors and low LOX expression (p = 0.3; Fig. 1I).

Although a difference in DFS by LOX expression level (p = 0.3) was not found in patients with BRAF-mutated tumors (n = 47), none of the patients with a BRAFV600E mutation and low LOX expression developed a recurrence, while four patients with a BRAFV600E mutation and high LOX expression did. In the BRAF-mutated group, there was no difference in duration of follow-up by LOX expression level (p = 0.57). The lack of statistical significance likely results from a type II statistical error, given the smaller sample size and few recurrences compared to TCGA cohort.

Because co-existing TERT promoter and BRAF mutations have been shown in thyroid cancer, TERT promoter mutations (C228T and C250T) were assessed using ddPCR in the independent cohort (NIH). Seven cases with a TERT C228T (6.5%) and two cases with a TERT C250T (1.8%) promoter mutation were discovered. However, only six cases with co-existence of BRAFV600E and TERT promoter mutations had high LOX expression. This suggests that high LOX expression is not due to the presence of TERT mutations in aggressive thyroid tumors. DFS analysis was not performed because of the limited number of patients with TERT promoter mutations, BRAF mutations, and high LOX expression.

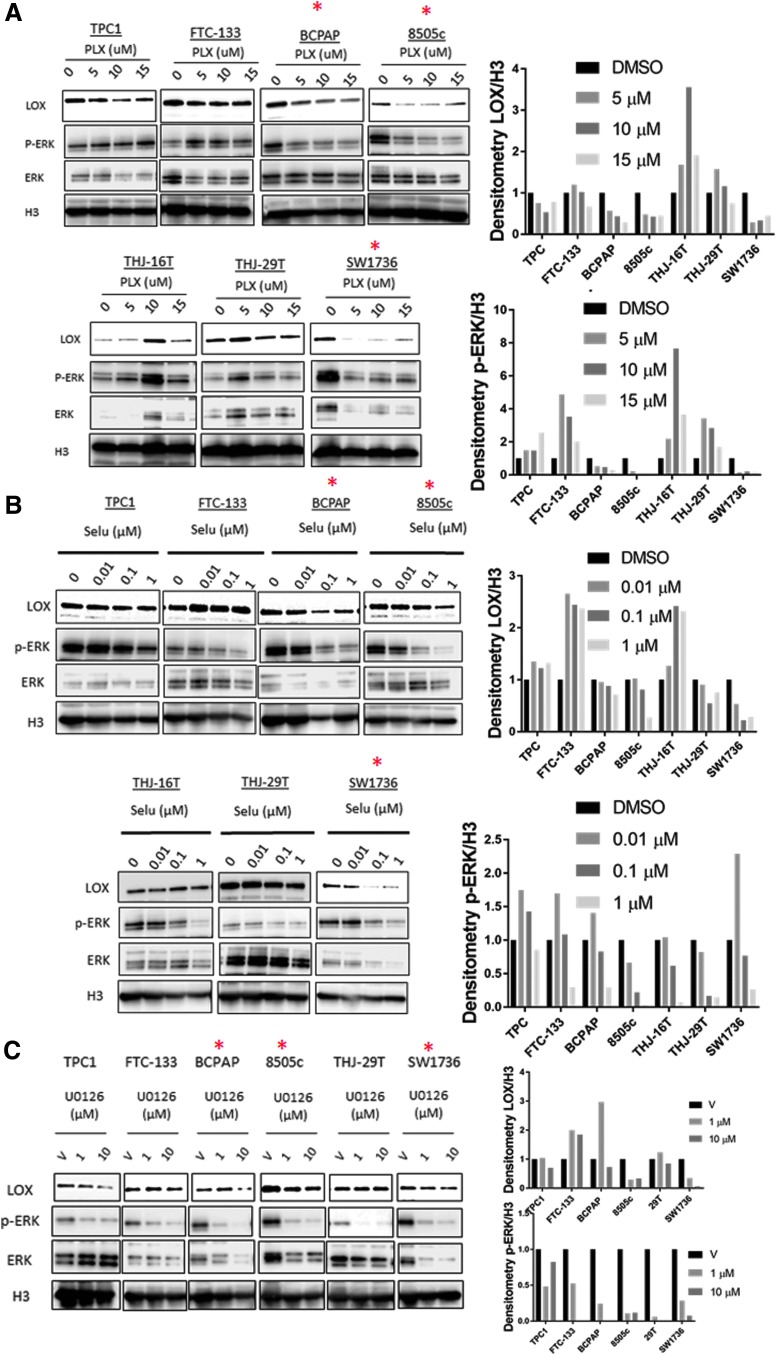

Mutant BRAF and the MAPK pathway regulate LOX expression in thyroid cancer cells

Given the positive and prognostic associations between BRAF-mutant tumors and LOX expression, the BRAFV600E mutation and/or the MAPK pathway were assessed for their ability to regulate LOX expression. PLX4720, an inhibitor of BRAFV600E showed a decrease in LOX and p-ERK expression at 48 hours after treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). This effect was more pronounced in BRAFV600E-mutated cell lines (BCPAP, 8505C, and SW1736) compared to wild-type BRAF cell lines.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of the MAPK pathway decreases LOX expression. (A) Western blot analysis of LOX and p-ERK expression in thyroid cancer cells treated for 48 hours with increasing concentrations of PLX4720 (PLX: 0, 5, 10, and 15 μM), (B) selumetinib (SELU: 0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μM), or (C) U0126 (0, 1, and 10 μM). Right panel shows the band densitometry from Western blots. *Cell lines with BRAFV600E mutation. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Next, the effect of two MEK inhibitors, selumetinib and U0126, on LOX expression was assessed. At 48 hours post treatment, selumetinib showed a dose-dependent decrease of LOX and p-ERK protein levels in the BRAF-mutated cell lines BCPAP, 8505C, and SW1736, as well as THJ-29T (wild-type BRAF; Fig. 2B). Conversely, FTC-133 cells, which carry a PTEN-inactivating mutation, showed lower p-ERK levels with increased LOX expression. Comparable results have been reported in colorectal cancer cells treated with selumetinib, showing that resistance to the MEK inhibitor is mediated by the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (33). This suggests that MEK inhibitor–induced feedback might maintain LOX expression (Fig. 2B). Treatment with U0126 decreased LOX expression in three cell lines with MAPK-activating mutations: TPC1 (RET/PTC1), 8505C (BRAFV600E), and SW1736 (BRAFV600E; Fig. 2C). Taken together, these data suggest that mutant BRAF and the MAPK pathway regulate LOX expression in thyroid cancer cell lines.

LOX knockdown sensitizes cancer cells to PLX4720 treatment in BRAF-mutant thyroid cancer cells

Given the high expression of LOX in BRAF-mutated tumors and the in vitro data showing possible MAPK regulation of LOX expression, the study investigated whether LOX suppression could enhance PLX4720 treatment response in BRAFV600E-mutant cell lines. PLX4720 treatment of BRAFV600E cell lines had a modest but significant antiproliferative effect (Supplementary Fig. S1A–C). To assess the effect of LOX depletion on PLX4720 response, varying concentrations of PLX4720 with siControl were compared to each corresponding concentration of PLX-4720 with siRNA(1) or siRNA(2). The observed effects were variable among the cell lines. BCPAP was the most sensitive to the combination of siRNA LOX(1) or siRNA LOX(2) and PLX4720, which correlated with the Western blot analysis showing a similar protein expression reduction with both siRNAs (Supplementary Fig. S1A and D). In 8505C and SW1736, the LOX depletion combined with PLX4720 reduced cell growth especially with siRNA LOX(1), the most effective siRNA on LOX expression, compared to siRNA LOX(2) (Supplementary Fig. S1B–D). These data suggest that LOX depletion sensitizes BRAF-mutated cells to PLX-4720 treatment.

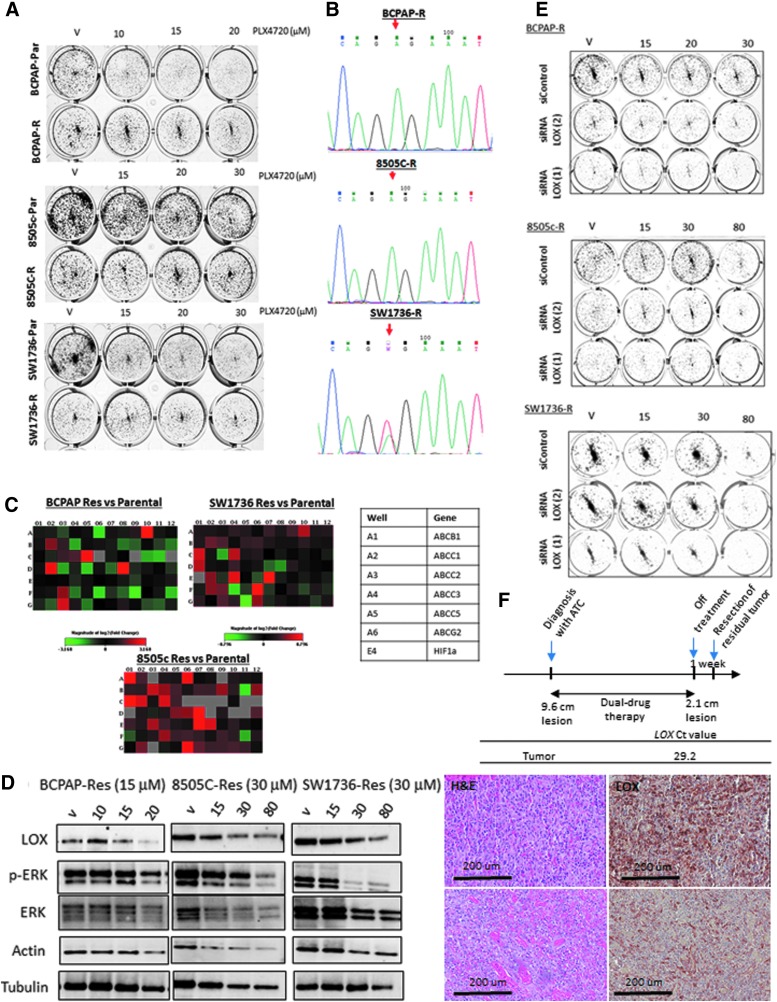

Chronic exposure to high concentrations of PLX4720 induces resistance to the drug and attenuates the inhibitory effect of PLX4720 on LOX expression

Given the strong association between presence of the BRAFV600E mutation, LOX expression, and more aggressive thyroid cancer phenotypes, it was considered whether LOX could mediate drug resistance. Three cell lines—BCPAP, 8505C, and SW1736—were exposed to increasing concentrations of PLX4720 for six months. When neither cell death nor response to PLX4720 was observed, the cells were considered resistant to 20 μM of PLX4720 for BCPAP and 30 μM for 8505C and SW1736. A colony formation assay confirmed the resistance of the cell lines, as it decreased colonies in parental cells with little or no effect on the “resistant” cells (Fig. 3A). Sequencing for the BRAFV600E mutation in the resistant cells confirmed the presence of the mutation, indicating that the resistance is not due to a selection of cells with no BRAFV600E (Fig. 3B). To validate the resistance to PLX4720 treatment, a drug resistance array was also performed. The analysis revealed a significant change in the multidrug resistance (MDR) gene expression levels (Fig. 3C). Two of them (ABCC1 and ABCB1) were validated by RT-PCR (Supplementary Fig. S2A). Treatment of resistant cells with increasingly high concentrations of PLX4720 showed a minor decrease of LOX and p-ERK at 20 μM for BCPAP and 30 μM in SW1736 and 8505C, indicating that the resistance to PLX4720 abrogates its effect on LOX expression and that alternative activators of the MAPK pathway such as RAS or AKT may be present in the resistant cells (Fig. 3D) (34,35). To analyze the association between response to MEK inhibitors and LOX level, the NCI-60 drug screening data were used. Since selumetinib was not used in the screening, the response for another MAPK inhibitor, trametinib (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminer/), was analyzed, and a significant inverse correlation was found between LOX expression and drug response (p = 0.03, r = −0.27; Supplementary Fig. S2B).

FIG. 3.

LOX depletion inhibits cell growth in PLX4720-resistant thyroid cancer cells. (A) Colony formation assay of naïve and resistant cells treated with high concentrations of PLX4720. (B) Chromatograms from Sanger sequencing showing a nucleotide change in position 1799T>A (red arrow). (C) Drug resistance PCR array analyzing the expression profile of 96 genes in the resistant cells compared to the parental cells. (D) Western blot analysis of LOX and p-ERK expression in resistant cells treated with high concentrations of PLX4720 (0, 10, 15, and 20 μM for BCPAP-R; 0, 15, 30, and 80 μM for 8505C-R and SW1736-R). (E) Colony formation assay of PLX-resistant cells transfected with siControl, siRNA LOX(1) or siRNA LOX(2) and treated with high concentrations of PLX4720. (F) Treatment schedule and LOX expression in patient with resistant residual anaplastic thyroid cancer to vemurafenib and cobimetinib dual therapy. R, resistant cells; Par, parental cells. All experiments were performed at least three times.

Next, the study considered whether LOX is still necessary for colony formation in the PLX4720-resistant but BRAF-mutant cells. As it did in the parental cells, LOX depletion decreased the clonogenicity of BCPAP-R, 8505C-R, and SW1736-R when grown in PLX4720-containing medium. These data suggest that LOX depletion in PLX4720-resistant cells may effectively overcome resistance (Fig. 3E).

In order to evaluate the biological relevance of the findings in patients treated with MAPK inhibitors, LOX expression was analyzed in a 78-year-old patient treated at the authors' institution for anaplastic thyroid cancer with vemurafenib and cobimetinib (36). Since drug resistance can be mediated by acquired mutations in the tumor (37), next-generation sequencing of hot spots was performed in 50 tumor suppressors and oncogenes, and sequencing of genes involved in thyroid carcinogenesis were targeted that showed no additional genetic alterations besides BRAFV600E (Supplementary Fig. S2C). Pathology review of the residual tumor revealed the presence of anaplastic thyroid cancer that was positive for LOX expression (Fig. 3F). These data suggest that the BRAFV600E-positive residual tumor is drug resistant and harbors strong LOX expression. Targeting LOX might overcome the resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors in patients with aggressive tumors.

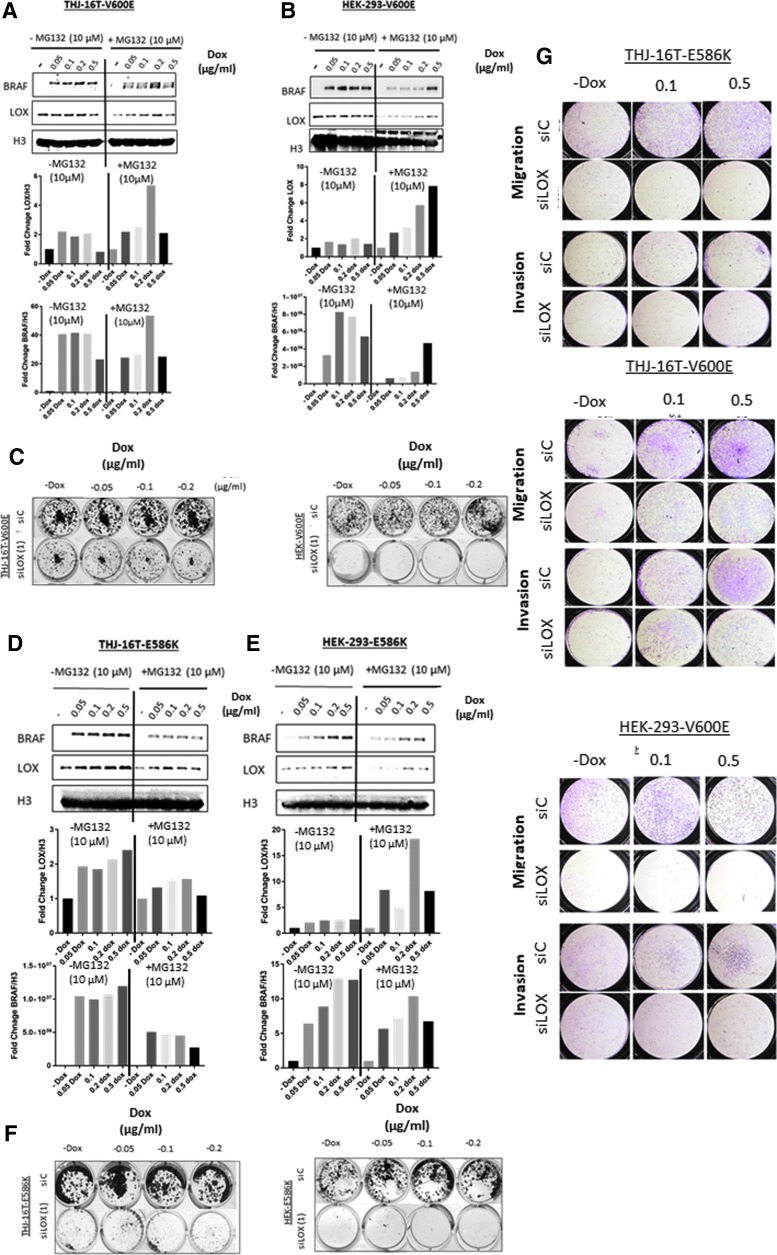

Expression of mutated BRAF enhances LOX expression

HEK-293 and THJ-16T cell lines were established with doxycycline-inducible expression of BRAFV600E or BRAFE586K mutants to test directly whether BRAF mutations regulate LOX expression. BRAFV600E and BRAFE586K are the two most common BRAF mutations with high kinase activity in cancer cells. The mutations in the vectors were first validated by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Fig. S3A and C). In the presence of doxycycline, the cell lines showed a dose-dependent increase in BRAF expression (Fig. 4A, B, D, and E). In the absence of MG-132, a proteasome inhibitor, the doxycycline-dependent increase in BRAF protein expression was associated with increased LOX protein expression that was more pronounced in BRAFE586K compared to BRAFV600E cell lines. However, treatment with MG-132 for 24 hours, combined with doxycycline, markedly increased LOX expression in cell lines overexpressing either BRAFV600E or BRAFE586K (Fig. 4A, B, D, and E) compared to no-doxycycline samples. As expected, the induction of mutated BRAF increased p-ERK expression (Supplementary Fig. S3E). These results further indicate that an overactivated MAPK kinase pathway mediated by activating mutations in BRAF can induce LOX expression that is more pronounced, particularly when proteasome degradation is inhibited.

FIG. 4.

Induction of BRAFV600E or BRAFE586K increases LOX expression. (A and B) Top panels: LOX and BRAF expression in THJ-16T and HEK-293 stably transfected with BRAFV600E vector. The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of doxycycline (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μg/mL) for 48 hours and incubated with 10 μM of MG-132 for 24 hours. Lower panels: Band densitometry of LOX and BRAF normalized to H3. (C) Colony formation assay of BRAFV600E cell lines transfected with either siControl or siRNA LOX(1). (D and E) Top panels: LOX and BRAF expression in THJ-16T and HEK-293 stably transfected with BRAFE586K vector. The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of doxycycline (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 0.5 μg/mL) for 48 hours and incubated with 10 μM of MG-132 for 24 hours. Lower panels: Band densitometry of LOX and BRAF normalized to H3. (F) Colony formation assay of BRAFVE586K cell lines transfected with either siControl or siRNA LOX(1). (G) Invasion and migration assay of BRAFV600E and BRAFVE586K cell lines induced with doxycycline and transfected with either siControl or siRNA LOX(1). All experiments were performed at least three times.

Since a BRAF-activating mutation is responsible for cell transformation and cancer metastasis, the study asked whether BRAF-induced LOX mediates the oncogenic functions of mutated BRAF. Induction of BRAFV600E or BRAFE586K slightly increased the number of colonies in HEK-293 cells only (Fig. 4C and F). However, no difference was observed in THJ-16T with either mutant (Fig. 4C and F). As expected, knocking down LOX in the four cell lines significantly reduced the number of colonies (Fig. 4C and F and Supplementary Fig. S3B and D). Cell motility analysis showed that BRAFV600E cells have higher invasion and migration capacity in both cell lines, whereas BRAFE586K only had similar effects in THJ-16T cells and that was reduced with LOX depletion (Fig. 4G). In aggressive cancer cells, the two processes of cell proliferation and invasion tend to be mutually exclusive (38). These data show that inducing BRAFV600E or BRAFE586K increases cell motility and that the phenotype conferred by mutated BRAF is abrogated with LOX depletion. The data suggest that the effects of mutant BRAF are mediated by LOX, at least in part.

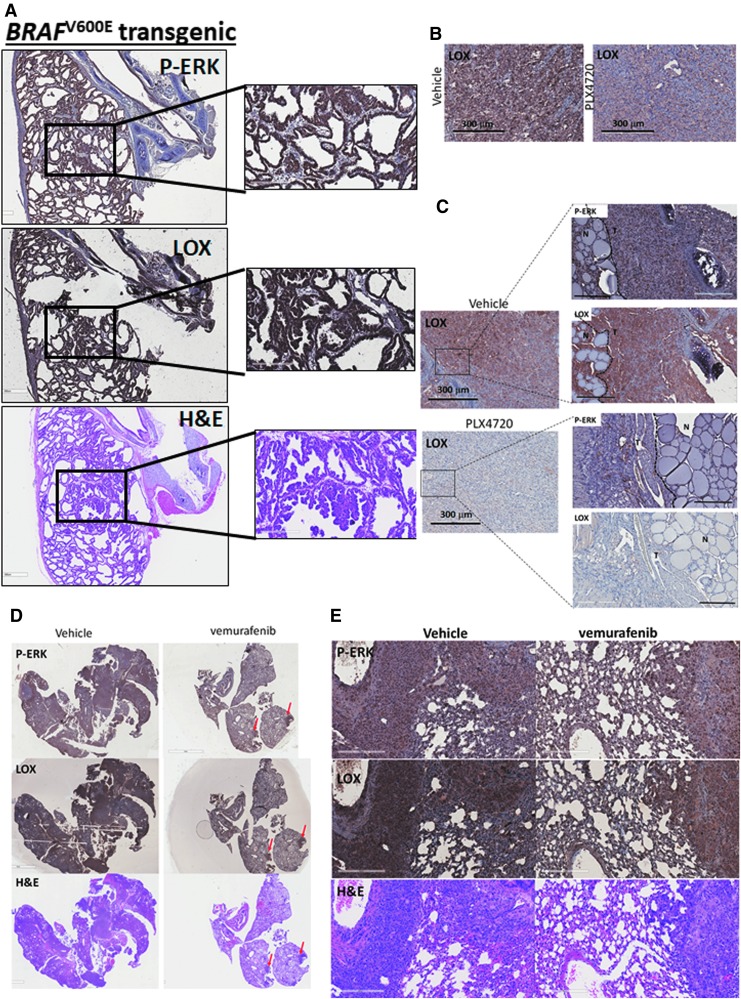

PLX4720 and vemurafenib inhibit tumor growth, metastasis, and LOX expression in vivo

Given the in vitro data, LOX expression was analyzed in a thyroid-specific BRAFV600E transgenic mouse model. Immunohistochemical staining showed strong staining of LOX and p-ERK in thyroid tumors compared to adjacent normal tissue (trachea, salivary glands, and muscles) harboring wild-type BRAF (Fig. 5A). This confirms the observations in human samples showing high LOX levels in BRAF-mutated tumors. In an orthotopic mouse model of thyroid cancer using BCPAP and 8505C cells, PLX4720 treatment reduced tumor size and tumor invasion (29). In the same samples, significant reduction of p-ERK and LOX staining was also found in the treated group compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 5B and C). Next, the effect of BRAFV600E inhibition was evaluated in a metastatic mouse model of thyroid cancer. Animals receiving PLX4032, the precursor compound to PLX4720, exhibited significantly smaller tumors and decreased LOX and p-ERK expression (Fig. 5D, E). Interestingly, histological analysis of the lungs from the treated group revealed drug-resistant nodules that were positive for p-ERK and LOX expression similar to the vehicle control group tumors (red arrows).

FIG. 5.

BRAFV600E mutation is associated with high LOX expression, and PLX4720 inhibits its expression in vivo. (A) H&E staining, LOX, and p-ERK expression by immunohistochemistry in the thyroid tumors of the BRAFV600E transgenic mouse model. High-power images are presented on the right of each immunostaining (n = 4 for each group). (B) LOX staining by immunohistochemistry in an orthotopic mouse model of thyroid cancer using BCPAP (n = 3 for each group). (C) LOX staining by immunohistochemistry in an orthotopic mouse model of thyroid cancer using ATC 8505C cells after two weeks of treatment with PLX4720 or vehicle control. High-power images are represented on the right (n = 3 for each group). (D,E) H&E, LOX, and p-ERK staining by immunohistochemistry in the metastatic anaplastic thyroid carcinoma mouse model using 8505C treated with PLX4032 or vehicle control (n = 5 for the vehicle control group and n = 8 for the treated group). The lower panel represents high-power images of the staining. All experiments were performed at least three times. H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

Discussion

The data show increased LOX in BRAFV600E-mutant tumors, and indicate that patients with BRAF-mutated tumors and high LOX expression levels have a shorter DFS than the low LOX group. Therefore, LOX may be an additional event in BRAFV600E-mutated tumors that can prompt more aggressive tumor behavior. Most thyroid cancer patients have low-risk disease at presentation. However, it is challenging to identify patients with higher risk of recurrence or locoregional disease in this category, which accounts for nearly 80% of all patients with thyroid cancer. The study on TCGA cohort shows that in BRAF-mutated tumors, low-risk patients with high LOX expression have a shorter DFS compared to low-risk patients, with low LOX levels. Therefore, LOX expression levels may help in stratifying patients at risk for recurrence who could benefit from more aggressive initial treatment and closer surveillance. Larger studies are highly needed to validate the cutoff for LOX expression that may be used in patient samples.

To understand the interaction between mutated BRAF and LOX expression, mechanistic in vitro and in vivo models were used. It was found that BRAFV600E and MEK inhibition decreased LOX expression, while overexpression of mutated BRAF increased it. The data suggest that BRAFV600E increases LOX by activating the MAPK pathway.

Next, the study sought to decipher the potential therapeutic relevance of the findings. It was found that LOX depletion sensitizes cancer cells to low concentrations of PLX4720. Moreover, LOX depletion restored the responsiveness of PLX4720-resistant cells. Although no current agents are known to target LOX, the results suggest that LOX depletion/inhibition could be an effective treatment strategy.

When mutant BRAF was ectopically expressed, it increased LOX expression, which was only detected when using a proteasome inhibitor. Therefore, LOX protein stability can be regulated by a post-translational modification that induces LOX proteasomal degradation. In addition to its role in cancer invasion, LOX generates H2O2 as a byproduct that can lead to DNA damage and cell senescence. It is believed that LOX protein is quickly synthesized and degraded within hours, as observed for another H2O2-producing enzyme, NOX4 (39). Also, previous studies have shown strong expression of LOX during mitosis when the kinase activity peaks (40–42). Moreover, LOX protein sequence analysis showed potential phosphorylation sites that are serine and threonine residues (www.phosphosite.com). However, it remains unclear whether the serine/threonine kinases BRAF or MEK regulate and activate LOX, which needs to be carefully investigated. The interaction between LOX and BRAF could also occur at the post-transcriptional level. It was previously shown that miR-30a regulates LOX expression (22), and analysis of THCA data revealed significantly lower miR-30a in BRAF-mutated tumors (Supplementary Fig. S4). This suggests that downregulation of miR-30a in BRAF-mutated tumors might lead to LOX overexpression, at least in part. Furthermore, a study performed in a lymphoma model revealed increased BRAF expression that was associated with aberrant expression of the pseudogene BRAFP1, which acts as a sponge for miR-30a. Although BRAFP1-mediated sequestration of miR-30a did not affect the miRNA abundance, it is possible that in thyroid cancer, the high affinity of BRAFP1 for miR-30a might be involved in LOX overexpression (43).

In summary, this study shows for the first time that LOX is a marker for identifying a subgroup of patients with BRAFV600E mutations and high-risk clinicopathologic features of thyroid cancer. The duet of markers of LOX expression level and BRAFV600E mutation may be useful to predict clinical outcomes, even in low-risk thyroid tumors. Validation by large multicenter studies will be instrumental in determining whether this duet of markers can predict patients outcomes. The BRAF–LOX axis drives thyroid cancer progression, suggesting that targeting LOX could enhance the efficacy of BRAF and MAPK targeted treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Carmelo Nucera for providing mouse samples. This research was supported by the intramural research program of the Center for Cancer Research, NCI, NIH (grant number 1ZIABC011275-06 to E.K.).

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Smallridge RC, Copland JA. 2010. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma: pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 22:486–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kebebew E, Greenspan FS, Clark OH, Woeber KA, McMillan A. 2005. Anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Cancer 103:1330–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Smyth P, Finn S, Cahill S, O'Regan E, Flavin R, O'Leary JJ, Sheils O. 2005. ret/PTC and BRAF act as distinct molecular, time-dependant triggers in a sporadic Irish cohort of papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Surg Pathol 13:1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathur A, Moses W, Rahbari R, Khanafshar E, Duh QY, Clark O, Kebebew E. 2011. Higher rate of BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid cancer over time: a single-institution study. Cancer 117:4390–4395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Elisei R, Viola D, Torregrossa L, Giannini R, Romei C, Ugolini C, Molinaro E, Agate L, Biagini A, Lupi C, Valerio L, Materazzi G, Miccoli P, Piaggi P, Pinchera A, Vitti P, Basolo F. 2012. The BRAF(V600E) mutation is an independent, poor prognostic factor for the outcome of patients with low-risk intrathyroid papillary thyroid carcinoma: single-institution results from a large cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:4390–4398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu D, Liu Z, Condouris S, Xing M. 2007. BRAF V600E maintains proliferation, transformation, and tumorigenicity of BRAF-mutant papillary thyroid cancer cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:2264–2271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Knauf JA, Ma X, Smith EP, Zhang L, Mitsutake N, Liao XH, Refetoff S, Nikiforov YE, Fagin JA. 2005. Targeted expression of BRAFV600E in thyroid cells of transgenic mice results in papillary thyroid cancers that undergo dedifferentiation. Cancer Res 65:4238–4245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xing M, Alzahrani AS, Carson KA, Viola D, Elisei R, Bendlova B, Yip L, Mian C, Vianello F, Tuttle RM, Robenshtok E, Fagin JA, Puxeddu E, Fugazzola L, Czarniecka A, Jarzab B, O'Neill CJ, Sywak MS, Lam AK, Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Santisteban P, Nakayama H, Tufano RP, Pai SI, Zeiger MA, Westra WH, Clark DP, Clifton-Bligh R, Sidransky D, Ladenson PW, Sykorova V. 2013. Association between BRAF V600E mutation and mortality in patients with papillary thyroid cancer. JAMA 309:1493–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nikiforova MN, Kimura ET, Gandhi M, Biddinger PW, Knauf JA, Basolo F, Zhu Z, Giannini R, Salvatore G, Fusco A, Santoro M, Fagin JA, Nikiforov YE. 2003. BRAF mutations in thyroid tumors are restricted to papillary carcinomas and anaplastic or poorly differentiated carcinomas arising from papillary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:5399–5404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riesco-Eizaguirre G, Gutierrez-Martinez P, Garcia-Cabezas MA, Nistal M, Santisteban P. 2006. The oncogene BRAF V600E is associated with a high risk of recurrence and less differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma due to the impairment of Na+/I– targeting to the membrane. Endocr Relat Cancer 13:257–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Elisei R, Ugolini C, Viola D, Lupi C, Biagini A, Giannini R, Romei C, Miccoli P, Pinchera A, Basolo F. 2008. BRAF(V600E) mutation and outcome of patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a 15-year median follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:3943–3949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chung KW, Yang SK, Lee GK, Kim EY, Kwon S, Lee SH, Park DJ, Lee HS, Cho BY, Lee ES, Kim SW. 2006. Detection of BRAFV600E mutation on fine needle aspiration specimens of thyroid nodule refines cyto-pathology diagnosis, especially in BRAF600E mutation-prevalent area. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 65:660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim SK, Kim DL, Han HS, Kim WS, Kim SJ, Moon WJ, Oh SY, Hwang TS. 2008. Pyrosequencing analysis for detection of a BRAFV600E mutation in an FNAB specimen of thyroid nodules. Diagn Mol Pathol 17:118–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim JY, Hong SW, Lee YS, Kim BW, Park CS, Chang HS, Cho JY. 2013. Clinicopathologic implications of the BRAF(V600E) mutation in papillary thyroid cancer: a subgroup analysis of 3130 cases in a single center. Thyroid 23:1423–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin L, Chen E, Dong S, Cai Y, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Zeng R, Yang F, Pan C, Liu Y, Wu W, Xing M, Zhang X, Wang O. 2016. BRAF and TERT promoter mutations in the aggressiveness of papillary thyroid carcinoma: a study of 653 patients. Oncotarget 7:18346–18355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xing M, Liu R, Liu X, Murugan AK, Zhu G, Zeiger MA, Pai S, Bishop J. 2014. BRAF V600E and TERT promoter mutations cooperatively identify the most aggressive papillary thyroid cancer with highest recurrence. J Clin Oncol 32:2718–2726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kagan HM, Li W. 2003. Lysyl oxidase: properties, specificity, and biological roles inside and outside of the cell. J Cell Biochem 88:660–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cox TR, Rumney RM, Schoof EM, Perryman L, Hoye AM, Agrawal A, Bird D, Latif NA, Forrest H, Evans HR, Huggins ID, Lang G, Linding R, Gartland A, Erler JT. 2015. The hypoxic cancer secretome induces pre-metastatic bone lesions through lysyl oxidase. Nature 522:106–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19. Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM. 2009. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell 139:891–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, Giaccia AJ. 2006. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature 440:1222–1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller BW, Morton JP, Pinese M, Saturno G, Jamieson NB, McGhee E, Timpson P, Leach J, McGarry L, Shanks E, Bailey P, Chang D, Oien K, Karim S, Au A, Steele C, Carter CR, McKay C, Anderson K, Evans TR, Marais R, Springer C, Biankin A, Erler JT, Sansom OJ. 2015. Targeting the LOX/hypoxia axis reverses many of the features that make pancreatic cancer deadly: inhibition of LOX abrogates metastasis and enhances drug efficacy. EMBO Mol Med 7:1063–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boufraqech M, Nilubol N, Zhang L, Gara SK, Sadowski SM, Mehta A, He M, Davis S, Dreiling J, Copland JA, Smallridge RC, Quezado MM, Kebebew E. 2015. miR30a inhibits LOX expression and anaplastic thyroid cancer progression. Cancer Res 75:367–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boufraqech M, Zhang L, Nilubol N, Sadowski SM, Kotian S, Quezado M, Kebebew E. 2016. Lysyl oxidase (LOX) transcriptionally regulates SNAI2 expression and TIMP4 secretion in human cancers. Clin Cancer Res 22:4491–4504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jolly LA, Novitskiy S, Owens P, Massoll N, Cheng N, Fang W, Moses HL, Franco AT. 2016. Fibroblast-mediated collagen remodeling within the tumor microenvironment facilitates progression of thyroid cancers driven by BrafV600E and Pten loss. Cancer Res 76:1804–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang L, Zhang Y, Mehta A, Boufraqech M, Davis S, Wang J, Tian Z, Yu Z, Boxer MB, Kiefer JA, Copland JA, Smallridge RC, Li Z, Shen M, Kebebew E. 2015. Dual inhibition of HDAC and EGFR signaling with CUDC-101 induces potent suppression of tumor growth and metastasis in anaplastic thyroid cancer. Oncotarget 6:9073–9085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marlow LA, D'Innocenzi J, Zhang Y, Rohl SD, Cooper SJ, Sebo T, Grant C, McIver B, Kasperbauer JL, Wadsworth JT, Casler JD, Kennedy PW, Highsmith WE, Clark O, Milosevic D, Netzel B, Cradic K, Arora S, Beaudry C, Grebe SK, Silverberg ML, Azorsa DO, Smallridge RC, Copland JA. 2010. Detailed molecular fingerprinting of four new anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines and their use for verification of RhoB as a molecular therapeutic target. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5338–5347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fabien N, Fusco A, Santoro M, Barbier Y, Dubois PM, Paulin C. 1994. Description of a human papillary thyroid carcinoma cell line. Morphologic study and expression of tumoral markers. Cancer 73:2206–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhang L, Gaskins K, Yu Z, Xiong Y, Merino MJ, Kebebew E. 2014. An in vivo mouse model of metastatic human thyroid cancer. Thyroid 24:695–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nehs MA, Nucera C, Nagarkatti SS, Sadow PM, Morales-Garcia D, Hodin RA, Parangi S. 2012. Late intervention with anti-BRAF(V600E) therapy induces tumor regression in an orthotopic mouse model of human anaplastic thyroid cancer. Endocrinology 153:985–994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Franco AT, Malaguarnera R, Refetoff S, Liao XH, Lundsmith E, Kimura S, Pritchard C, Marais R, Davies TF, Weinstein LS, Chen M, Rosen N, Ghossein R, Knauf JA, Fagin JA. 2011. Thyrotrophin receptor signaling dependence of Braf-induced thyroid tumor initiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:1615–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Haugen BR, Alexander EK, Bible KC, Doherty GM, Mandel SJ, Nikiforov YE, Pacini F, Randolph GW, Sawka AM, Schlumberger M, Schuff KG, Sherman SI, Sosa JA, Steward DL, Tuttle RM, Wartofsky L. 2016. 2015 American Thyroid Association management guidelines for adult patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer: the American Thyroid Association Guidelines Task Force on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid 26:1–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J. 2009. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45:228–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grasso S, Tristante E, Saceda M, Carbonell P, Mayor-Lopez L, Carballo-Santana M, Carrasco-Garcia E, Rocamora-Reverte L, Garcia-Morales P, Carballo F, Ferragut JA, Martinez-Lacaci I. 2014. Resistance to Selumetinib (AZD6244) in colorectal cancer cell lines is mediated by p70S6K and RPS6 activation. Neoplasia 16:845–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanchez-Laorden B, Viros A, Girotti MR, Pedersen M, Saturno G, Zambon A, Niculescu-Duvaz D, Turajlic S, Hayes A, Gore M, Larkin J, Lorigan P, Cook M, Springer C, Marais R. 2014. BRAF inhibitors induce metastasis in RAS mutant or inhibitor-resistant melanoma cells by reactivating MEK and ERK signaling. Sci Signal 7:ra30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Perna D, Karreth FA, Rust AG, Perez-Mancera PA, Rashid M, Iorio F, Alifrangis C, Arends MJ, Bosenberg MW, Bollag G, Tuveson DA, Adams DJ. 2015. BRAF inhibitor resistance mediated by the AKT pathway in an oncogenic BRAF mouse melanoma model. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:E536–545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Green P, Schwartz RH, Shell J, Allgauer M, Chong D, Kebebew E. 2017. Exceptional response to vemurafenib and cobimetinib in anaplastic thyroid cancer 40 years after treatment for papillary thyroid cancer. Int J Endocr Oncol 4:159–165 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gerlinger M, Swanton C. 2010. How Darwinian models inform therapeutic failure initiated by clonal heterogeneity in cancer medicine. Br J Cancer 103:1139–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gao CF, Xie Q, Su YL, Koeman J, Khoo SK, Gustafson M, Knudsen BS, Hay R, Shinomiya N, Vande Woude GF. 2005. Proliferation and invasion: plasticity in tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:10528–10533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Serrander L, Cartier L, Bedard K, Banfi B, Lardy B, Plastre O, Sienkiewicz A, Forro L, Schlegel W, Krause KH. 2007. NOX4 activity is determined by mRNA levels and reveals a unique pattern of ROS generation. Biochem J 406:105–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ma HT, Poon RY. 2011. How protein kinases co-ordinate mitosis in animal cells. Biochem J 435:17–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Combes G, Alharbi I, Braga LG, Elowe S. 2017. Playing polo during mitosis: PLK1 takes the lead. Oncogene 36:4819–4827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mehra R, Serebriiskii IG, Burtness B, Astsaturov I, Golemis EA. 2013. Aurora kinases in head and neck cancer. Lancet Oncol 14:e425-435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karreth FA, Reschke M, Ruocco A, Ng C, Chapuy B, Leopold V, Sjoberg M, Keane TM, Verma A, Ala U, Tay Y, Wu D, Seitzer N, Velasco-Herrera Mdel C, Bothmer A, Fung J, Langellotto F, Rodig SJ, Elemento O, Shipp MA, Adams DJ, Chiarle R, Pandolfi PP. 2015. The BRAF pseudogene functions as a competitive endogenous RNA and induces lymphoma in vivo. Cell 161:319–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.