Abstract

Cognitive decline is a feature of normal and pathological aging. As the proportion of the global aged population continues to grow, it is imperative to understand the molecular and cellular substrates of cognitive aging for therapeutic discovery. This review focuses on the critical role of neural extracellular matrix in the regulation of neuroplasticity underlying learning and memory in another under-investigated “critical period”: the aging process. The fascinating ideas of neural extracellular matrix forming a synaptic cradle in the tetrapartite synapse and possibly serving as a substrate for storage of very long-term memories will be introduced. We emphasize the distinct functional roles of diffusive neural extracellular matrix and perineuronal nets and the advantage of the coexistence of two structures for the adaptation to the ever-changing external and internal environments. Our study of striatal neural extracellular matrix supports the idea that chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-associated extracellular matrix is restrictive on synaptic neuroplasticity, which plays important functional and pathogenic roles in early postnatal synaptic consolidation and aging-related cognitive decline. Therefore, the chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-associated neural extracellular matrix can be targeted for normal and pathological aging. Future studies should focus on the cell-type specificity of neural extracellular matrix to identify the endogenous, druggable targets to restore juvenile neuroplasticity and confer a therapeutic benefit to neural circuits affected by aging.

Keywords: aging, cognitive decline, neural extracellular matrix, tetrapartite synapse, long-term memory storage, therapeutic targeting, striatum, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan

Introduction

Cognitive decline is a feature of normal and pathological aging. As the proportion of the global aged population continues to grow, it is imperative to understand the molecular and cellular substrates of cognitive aging for therapeutic discovery. In the past two decades, neural extracellular matrix (ECM) has been identified as a key regulator of neuroplasticity underlying learning and memory. While many ECM studies focused on early brain development as the “critical periods,” another “critical period,” the aging process, has been largely under-investigated. What contributes to the aging-dependent cognitive decline? Does the aged brain still have the capacity to learn new skills and to adapt to the changing environment? Can we delay aging-related decline in cognitive function? Can the juvenile-like neuroplasticity be restored to ameliorate cognitive deficits in neurodegenerative disorders? Our recent study of the striatal neural ECM across the life-span contributes to the growing body of literature suggesting neural ECM is a substrate for cognitive aging (Richard et al., 2018). We argue that the aged brain has the capacity to change its structure and function in reaction to environmental diversity, despite some neural deterioration. We suggest chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan (CSPG)-associated neural ECM can be targeted to attenuate normal and pathological aging-related cognitive decline. We have performed a PubMed literature search of articles published in the period January 2008–June 2018 on neural ECM, aging, cognitive decline, and neural plasticity.

Neural ECM Forms a Synaptic Cradle in the Tetrapartite Synapse: Beyond Perineuronal Nets

First proposed in the 1949 by Donald Hebb, synaptic connectivity is immensely plastic and constantly remodeled under the influence environmental factors. This remarkable synaptic plasticity underlies cognitive function, including learning and memory. Among the key regulators of plasticity is the neural ECM. Accumulating evidence has revealed contributions of neural ECM molecules to plasticity across several brain nuclei, including cortical regions, hippocampus, and amygdala, in which depletion of neural ECM molecules can restore juvenile-like plasticity (Senkov et al., 2014). The neural ECM is composed of hyaluronan polysaccharides which bind hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1. Hyaluronan and hyaluronan and proteoglycan link protein 1 form a backbone to which CSPGs are bound. The structure of the neural ECM is stabilized through crosslinking between CSPGs and the glycoprotein tenascin-R. Neural ECM exists within the perisynaptic space (termed perisynaptic or diffusive ECM) and also forms specialized net-like structures around some neuronal cell bodies termed perineuronal nets (Figure 1A). The structure of the perineuronal net inhibits the mobility of AMPA receptors on the cell membrane and also regulates the firing patterns of neuronal cells, directly affecting long-term potentiation and long-term depression, which are critical processes of learning and memory. The neural ECM is modulated in vivo by activity-dependent accumulation, degradation, or reorganization. Matrix proteoglycans are degraded by matrix metalloproteinases, particularly matrix metalloproteinase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9, which are calcium-dependent zinc-containing endopeptidases, and a disintegrin and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin motifs (ADAMTS), which cleave a number of lecticans within the neural ECM, including neurocan, brevican, versican, and aggrecan. ECM proteoglycan turnover through cleavage via matrix metalloproteinases and ADAMTS is important for the formation and consolidation of new synaptic connections (Sorg et al., 2016; Ferrer-Ferrer and Dityatev, 2018).

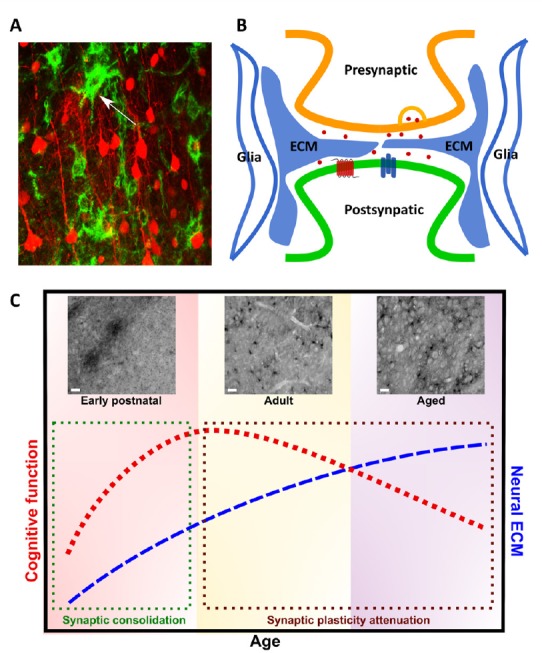

Figure 1.

Role of neural extracellular matrix (ECM) in the tetrapartite synapse and cognitive function.

(A) Neural ECM revealed by Wisteria floribunda agglutinin (WFA), a plant lectin that binds chondroitin sulfates of neural ECM chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs). Confocal imaging of the WFA staining (green) and sparse pyramidal neuron labelling (red) in cortex. Arrowhead denotes WFA+ perineuronal net. (B) Neural ECM is an integral component of tetrapartite synapse. The tetrapartite synapse is a conceptual model that includes pre- and post-synaptic elements, glia, and neural ECM as the four major components contributing to synaptic transmission. Neural ECM together with gila provide a physical scaffold that stabilizes the structure of dendritic spines, but also buffers extracellular ions and modulates neurotransmitter signaling and membrane receptor mobility. (C) Relationship of neural ECM and cognitive function throughout aging. Cognitive function varies throughout lifespan. In postnatal development, rapid development and differentiation of neural cells during critical periods of plasticity drive marked increases in cognitive function through synaptic maturation and consolidation (denoted by green box). WFA immunostaining reveals dynamic changes in diffusive, perisynaptic ECM and perineuronal nets in the dorsal striatum throughout aging. At postnatal day 7, before the onset of the motor critical period, neural ECM exists as immature, diffusive WFA+ CSPG– enriched clusters in the dorsal striatum (above green box). At 3 months of age (adult), the dorsal striatum contains both WFA+ perineuronal nets and perisynaptic ECM. Cognitive function peaks in adulthood, but neuroplasticity is reduced in comparison to developmental stages. Cognitive function trends downward throughout adulthood and in the aged brain (denoted by brown box). At 22 months (aged), accumulation of WFA+ perisynaptic ECM is correlated with aging-related cognitive decline (above brown box), suggesting a restrictive role in synaptic plasticity. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Pioneered by Dityatev group (Dityatev and Rusakov, 2011), the concept of the tetrapartite synapse was proposed to emphasize the contributions of neural ECM to synaptic transmission. Such concept has changed the traditional view of the tripartite synapse that includes pre-synaptic, post-synaptic elements, and astrocytes. The neural ECM has been shown to interact with each of these synaptic elements and glia through both chemical and physical mechanisms. Through cleavage via matrix metalloproteinases, ECM molecules may act as chemical messengers and also interact with membrane proteins. In addition, the neural ECM forms a physical barrier between and within synaptic clefts, which stabilizes spine structure and morphology, restricts spine motility, and buffers extracellular ions and neurotransmitters (Senkov et al., 2014). Thus the neural ECM together with astrocytes form a synaptic cradle that is essential for synaptogenesis, maturation, isolation and maintenance of synapses, representing the fundamental mechanism contributing to neuroplasticity. The late Tsien (2013) postulated the pattern of holes within ECM may be the storage sites of very-long term memories in the adult brain. Although further studies would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis, neural ECM may play a unique structural scaffolding role in the synaptic cradle, with the holes created by ECM determining synaptic plasticity. The relatively stable structural characteristics of perisynaptic ECM satisfies the criteria as the substrate of very long-term memory storage (Figure 1B).

Many studies of neuroplasticity and ECM focused on perineuronal nets, which mainly surround parvalbumin interneurons. The enzyme chondroitinase ABC (ChABC) has been used almost exclusively to degrade perineuronal nets in these studies. However, ChABC depletes both perineuronal nets and perisynaptic ECM. In our recent publication (Richard et al., 2018), we have reported for the first time the presence of two distinct CSPG-associated structures, including the highly-specialized perineuronal nets (Lee et al., 2008) as previously reported, and another, not well-characterized, perisynaptic ECM structure spreading across the adult striatum in mice. Both structures can be depleted by ChABC treatment. Perineuronal nets are most strongly associated with interneurons, therefore, the CSPG-associated perisynaptic ECM may be associated with striatal principal neurons. Although only shown in very few studies, depletion of only the perisynaptic ECM via microinjection of ChABC was sufficient to promote synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus (Orlando et al., 2012). The synaptic function of CSPG-associated perisynaptic ECM may be similar to that of CSPGs within perineuronal nets, but in a less restrictive manner. Perhaps the existence of both perineuronal nets and diffusive ECM in the adult striatum, which may differentially affect plasticity, could offer an advantage for adaptation to the ever-changing external and internal environments. Therefore, the concept of tetrapartite synapse should be applied to all the neuronal cell types. More precise genetic or pharmacologic experiments are warranted to differentiate specific functional differences between these types of ECM.

Striatal Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan-Associated ECM Is Restrictive to Synaptic Neuroplasticity: Implications in Early Postnatal Synaptic Consolidation and Aging-Related Cognitive Decline

Among the most vulnerable brain regions to aging-related alterations in plasticity is the striatum, a key nucleus within the basal ganglia. The striatum has two principal neuron subtypes: dopamine D1 receptor-expressing spiny projection neurons of the direct pathway, which send projections to the substantia nigra pars reticulata and internal segment of globus pallidus, and dopamine D2 receptor-expressing spiny projection neurons of the indirect pathway, which send projections to the external segment of globus pallidus and subthalamic nucleus. The striatum receives dense glutamatergic innervation from somatosensory cortical regions and thalamic neurons, and dopaminergic innervation from the substantia nigra pars compacta. The striatum is critical for a number of cognitive functions, including procedural (motor) learning, habit formation, attention, motivation, and affective control. The striatal-based motor skill learning has an interesting feature, once it is mastered, the motor skill can be remembered for a long period of time, such as learning to ride a bicycle. The substrates for storage of such long-term striatal-based memories have not been defined. In humans, some aspects of striatal-based cognitive function decline during aging. Young adults perform significantly better than aged adults in working memory tasks and in the acquisition of complex motor skills.

The temporal and spatial distribution patterns and occurrence of regional specialization of CSPG-associated ECM in the striatum might provide a basis for implication in striatal development and adult function. Indeed, the striatum has a prominent diffusive ECM and relatively low level of perineuronal net in comparison to other brain regions, such as the cortex and hippocampus, implicating higher flexibility related to striatal plasticity. Perhaps the relatively low level of neural ECM in the striatum contributes to its vulnerability to aging-related alternations in function.

In the early postnatal stage, our report and others have identified diffusive CSPG clusters in the striatum. The diffusive CSPG clusters disappear by postnatal day 14, coincident with the appearance of perineuronal nets. The CSPG clusters co-localize with cortical/thalamic glutamatergic ‘afferent islands’ in the immature striatum (Nakamura et al., 2009). At this time, striatal projection neurons (predominantly direct pathway spiny projection neurons) within affinity islands undergo rapid excitatory synaptogenesis (Lu and Yang, 2017). It has been hypothesized that CSPGs can regulate consolidation of neural circuits by defining a permissive environment (Pizzorusso et al., 2002). Thus, the diffusive CSPG clusters may play a critical role in consolidation of glutamatergic afferents to spiny projection neurons and promotion of rapid excitatory synaptogenesis leading to functional maturation of the striatum (Figure 1C).

Furthermore, we sought to characterize the striatal ECM in adulthood and throughout aging. Immunostaining using Wisteria floribunda agglutinin, a plant lectin with high affinity to N-acetylgalactosamine residues contained in CS, revealed prominent perisynaptic ECM and perineuronal nets throughout the dorsal striatum in adult (3 months old) mice. In aged mice (22 months old), the perisynaptic ECM had accumulated significantly. We found a correlation between neural ECM accumulation and aging-related decline of two striatal-based cognitive functions: working memory and motor learning. To determine if striatal ECM accumulation impacted aging-related cognitive decline, we used ChABC to deplete ECM CSPGs in aged mice. Intrastriatal ChABC eliminated both perineuronal nets and perisynaptic CSPGs in aged mice and significantly improved motor skill learning, but not working memory (Richard et al., 2018). It reveals that CSPG-associated ECM restricts synaptic neuroplasticity and is inversely related to the cognitive fucntion. Thus, our study highlights the aging-dependent accumulation of striatal CSPG-associated ECM as a substrate of cognitive decline (Figure 1C).

Targeting Chondroitin Sulfate Proteoglycan-Associated ECM for Cognitive Deficits in Normal and Pathological Aging

Aging has been associated with a persistent decrease in neuroplasticity. Several studies suggest that this decrease in plasticity coupled with changes in neuronal morphology and firing patterns underlies aging-dependent cognitive decline. Most neurodegenerative diseases also have cognitive impairment as a prodromal symptom or a consequence of the disease progression, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease. Although these neurodegenerative disorders have different etiologies, aging is the number one risk factor and the shared symptom of cognitive dysfunction may be caused or exacerbated by a common neural substrate. Cognitive deficits in neurodegenerative disorders range from mild cognitive impairment to progressive cognitive decline and eventual dementia. Cognitive deficits are now recognized to be integral to neurodegenerative disease at onset and throughout the full course of the disease. Importantly, cognitive deficits have a great impact on quality of life of patients and have become the focus of medical care. However, future therapeutic development for cognitive deficits is severely hindered by the lack of understanding of the underlying pathophysiology.

The neural ECM is a suitable candidate substrate based on the restrictive environment it creates toward synaptic plasticity. This relationship is well established in development and adulthood, but the impact of neural ECM on the aging brain is markedly less documented. Evidence for a critical role of neural ECM in aging-related cognitive decline was uncovered in a study of neural ECM and hippocampal function in aged mice. It was found that neural ECM proteins, especially the CSPGs brevican and neurocan, were significantly upregulated in the aged hippocampus but not in young or middle age. In addition, Wisteria floribunda agglutinin immunostaining demonstrated an increase in ECM density between young and aged mice in the hippocampus. The increase in hippocampal ECM correlated with an aging-related decline of spatial learning in the Barnes maze (Vegh et al., 2014). Another report discovered in both genetic and viral-induced mouse models of tauopathy, ChABC infusion in the perirhinal cortex reversed the decline of object recognition memory, but did not reverse disease progression (Yang et al., 2015). These exciting results, together with our findings of the correlation between the aging-dependent accumulation of striatal CSPG-associated ECM and decline of motor learning, strongly suggest targeting of the striatal ECM may be translatable to neurodegenerative disorders of the basal ganglia, including Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease.

Further studies are needed to determine the molecular mechanisms underlying aging-dependent cognitive decline in normal and pathological aging. In addition, the contributions of cognitive decline to specific pathogenic mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases is unknown. In order to further elucidate neural ECM as a therapeutic target, some questions must be posited: what are the molecular and functional differences between perineuronal nets and diffusive ECM? Furthermore, does neural ECM have cell-type specificity, and if so, what determines this specificity? The endogenous, druggable targets of neural ECM molecules must be identified for genetic and pharmacologic manipulation. Such specific manipulations of neural ECM would permit restoration of juvenile neuroplasticity and confer a therapeutic benefit to circuits affecting by aging, therefore to “teach old dogs new tricks.”

Additional file: Open peer review report 1 (111.1KB, pdf) .

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

Financial support: The work is supported in part by National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD) Young Investigator Grant from Brain Behavorial Research Foundation, No. 21365 (to XHL) and Ike Muslow Predoctoral Fellowship from Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport (to ADR).

Copyright license agreement: The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by both authors before publication.

Plagiarism check: Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review: Externally peer reviewed.

Open peer reviewer: Jigar Pravinchandra Modi, Florida Atlantic University, USA.

Funding: The work is supported in part by National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD) Young Investigator Grant from Brain Behavorial Research Foundation, No. 21365 (to XHL) and Ike Muslow Predoctoral Fellowship from Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport (to ADR).

P-Reviewer: Modi JP; C-Editors: Zhao M, Yu J; T-Editor: Liu XL

References

- Dityatev A, Rusakov DA. Molecular signals of plasticity at the tetrapartite synapse. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:353–359. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer-Ferrer M, Dityatev A. Shaping synapses by the neural extracellular matrix. Front Neuroanat. 2018;12:40. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Leamey CA, Sawatari A. Rapid reversal of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan associated staining in subcompartments of mouse neostriatum during the emergence of behaviour. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu XH, Yang XW. Genetically-directed sparse neuronal labeling in BAC transgenic mice through mononucleotide repeat frameshift. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43915. doi: 10.1038/srep43915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura KC, Fujiyama F, Furuta T, Hioki H, Kaneko T. Afferent islands are larger than mu-opioid receptor patch in striatum of rat pups. Neuroreport. 2009;20:584–588. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328329cbf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando C, Ster J, Gerber U, Fawcett JW, Raineteau O. Perisynaptic chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans restrict structural plasticity in an integrin-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 2012;32:18009–18017. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2406-12.2012. 18017a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzorusso T, Medini P, Berardi N, Chierzi S, Fawcett JW, Maffei L. Reactivation of ocular dominance plasticity in the adult visual cortex. Science. 2002;298:1248–1251. doi: 10.1126/science.1072699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard AD, Tian XL, El-Saadi MW, Lu XH. Erasure of striatal chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-associated extracellular matrix rescues aging-dependent decline of motor learning. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;71:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senkov O, Andjus P, Radenovic L, Soriano E, Dityatev A. Neural ECM molecules in synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory. Prog Brain Res. 2014;214:53–80. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63486-3.00003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorg BA, Berretta S, Blacktop JM, Fawcett JW, Kitagawa H, Kwok JC, Miquel M. Casting a wide net: role of perineuronal nets in neural plasticity. J Neurosci. 2016;36:11459–11468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2351-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien RY. Very long-term memories may be stored in the pattern of holes in the perineuronal net. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12456–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310158110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vegh MJ, Rausell A, Loos M, Heldring CM, Jurkowski W, van Nierop P, Paliukhovich I, Li KW, del Sol A, Smit AB, Spijker S, van Kesteren RE. Hippocampal extracellular matrix levels and stochasticity in synaptic protein expression increase with age and are associated with age-dependent cognitive decline. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2014;13:2975–2985. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.032086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Cacquevel M, Saksida LM, Bussey TJ, Schneider BL, Aebischer P, Melani R, Pizzorusso T, Fawcett JW, Spillantini MG. Perineuronal net digestion with chondroitinase restores memory in mice with tau pathology. Exp Neurol. 2015;265:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.