Abstract

Tribulus terrestris (TT), a herb belonging to Zygophyllaceae family is widely used due to its medicinal properties. This study was undertaken to elucidate the anticancer mechanism of TT on MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Cytotoxic effect of the herb was assessed by 3-(4,5-diethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Apoptotic potential was assessed through DNA fragmentation, TUNEL and caspase 3 activity assays. Expressions of genes regulating the apoptotic pathway were examined by RT-PCR and expression of proteins was analyzed by immunocytochemistry. The result of MTT assay revealed that methanolic and saponin extracts from leaves and seeds of TT were cytotoxic to MCF-7 cells. Cytotoxicity studies on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) proved that TT extracts were non-toxic to non-malignant cells. Treatment of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells with seed and leaf methanol and saponin extracts of TT resulted in fragmentation of DNA and induction of apoptosis. This was evident by agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA and TUNNEL assay. The extracts of TT also caused a significant increase in caspase 3 activity in MCF-7 cells. TT extracts caused an induction of intrinsic apoptotic pathway which was evident by the upregulation in the expression of Bax and p53 genes and downregulation in the expression of Bcl-2. FADD, AIF and caspase 8 genes were also upregulated indicating the possible induction of extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Therefore, our results suggest that the Tribulus terrestris (TT) extracts may exert their anticancer activity by both extrinsic and intrinsic apoptotic pathways.

Keywords: Tribulus terrestris, Breast cancer, Apoptosis, Cytotoxicity, Anticancer activity

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide. It represented about 25% of cancer diagnosed in the female population and was the fifth most common cause of death from cancer in women in 2012 (Breast cancer statistics 2012). Breast cancer cell lines have helped us to understand the process of carcinogenesis in breast tissues. These cell lines offer an advantage of homogeneity due to the use of simple and standardized techniques (Lacroix et al. 2004). MCF-7, T47D and MDA-MB231 are some of the commonly used cell lines in breast cancer studies (Lacroix et al. 2004). MCF-7 cells are well-characterized and have been widely used as a model to study the pathogenesis of breast cancer (Comşa et al. 2015).

Herbal medicines have been used since ancient times due to their efficacy and cultural acceptability. Natural compounds have been widely tested for their anticancer properties due to minimum side effects. Alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, tannins, phenolics, etc., are some of naturally occurring active principals found in nature (Basaiyye et al. 2017). Tribulus terrestris L. (TT) (Zygophyllaceae) is an annual herb that has been used in the traditional medicine all over the world (Graham et al. 2000; Angelova et al. 2013). TT extracts have been reported to induce the arrest of cell growth and induce apoptosis by down-regulating NF-κB signaling in liver cancer cells (Kim et al. 2011). TT extracts exhibit weak cytotoxic effects in normal cells as compared to cancer cells (Neychev et al. 2007). The biological activities of T. terrestris have been attributed to its steroidal saponins (Su et al. 2009; Bedir et al. 2002). Saponins from TT have been proposed to exert their anticancer effect by induction of apoptotic pathway in breast cancer cells (Neychev et al. 2007; Angelova et al. 2013). Alkaloids from TT, viz., trans-N-feruloyl-3-hydroxytyramine and trans-N-feruloyl-3-ethoxytyramine have been reported to induce apoptosis in leukemic cancer cells (Basaiyye et al. 2017). The present study was undertaken to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in the anticancer effects of extracts from Tribulus terrestris L. (TT).

Methods

Tribulus terrestris L. was collected during its fruiting period (December–March) from Junagham, near Suvalli, dist. Surat, Gujarat, latitude, 21.141400 and longitude, 72.63525. The plant was identified and authenticated by Dr. M. N Reddy (Professor, Department of Biosciences, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, India). The voucher specimen (BVBRC1205) has been deposited at Shri Bapalal Vaidhya Botanical Research Centre, Veer Narmad South Gujarat University, Surat, Gujarat, India. The plant materials were washed under tap water and rinsed with distilled water. The leaves and seeds were dried separately in an oven at 60 °C. The resultant dried plant parts were powdered and defatted in Soxhlet apparatus using n-hexane. The defatted extract was again treated with methanol and acetone to obtain a colorless extract. Resulting dried extracts from the seeds and leaves of TT were used for further studies. Similarly, the saponins were extracted from dried leaves and seeds as described by Obadoni and Ochuko (2001).

Human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line was obtained from National Centre for Cell Sciences, Pune, India. The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium as described by Noomhorm et al. (2014).

Determination of cytotoxicity and cell proliferation

Cytotoxic potential of Tribulus terrestris leaf and seed extracts was evaluated using 3-(4,5-diethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) isolated from human blood were used as healthy non-cancerous control cells. The antiproliferative activities of TT leaf and seed extracts were determined by the colorimetric MTT assay. Cells (5 × 103/ml) were seeded 24 h prior to treatment in a 96-well plate. Wells with serum-free medium were used as negative controls. After incubating the cells for 24 h, they were treated with the methanolic and saponin extracts of TT leaf and seed at a concentration in the range of 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50 and 100 µg/ml. This was followed by incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. 10 µl MTT reagent was added to each well and incubated for further 4 h in dark at 37 °C. This was followed by addition of 100 µl of Sorenson glycine buffer (0.1M glycine, 0.1M NaCl, pH 10.5 with 0.1N NaOH) to the wells to solubilize the formazan crystals. The absorbance was measured at 490 nm. The experiment was repeated three times in triplicate. The percentage viability and inhibition of cells was calculated as follows,

DNA fragmentation assay was performed as per the method described by Horiuchi et al. (1988) with slight modification. Briefly, MCF-7 cells were cultured in MEM medium supplemented with different concentrations of TT extracts (Table 1) at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml for 9 days. Both adherent and floating cells were collected and DNA was isolated as described by the manufacturer’s protocol using Apoptotic DNA ladder kit (Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Germany). An aliquot containing 2 µg genomic DNA was analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel and visualized under UV after staining with ethidium bromide.

Table 1.

Extracts and concentrations of Tribulus terrestris L. used in this study

| Extracts | Concentrations (µg/ml) |

|---|---|

| Leaf methanol (LM1) | 25 |

| Leaf methanol (LM2) | 12.5 |

| Seed methanol (SM1) | 25 |

| Seed methanol (SM2) | 12.5 |

| Leaf saponin (LS1) | 12.5 |

| Leaf saponin (LS2) | 6.25 |

| Seed saponin (SS1) | 12.5 |

| Seed saponin (SS2) | 6.25 |

| Untreated control | – |

Determination of apoptosis

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay was carried out following the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche, catalogue number 11 684 817 910). The percentage of apoptosis was determined as follows,

Caspase-3 activity assay

Caspase-3 colorimetric protease assay was carried out as per the manufacturer’s instruction (Thermo Fischer, USA). Apoptosis was induced in MCF-7 cells by treating them with selected concentrations of leaf and seed methanolic and saponin extract of TT for 24 h in 6-well plate (0.5 × 106 cells/ml). Cells without drug were used as control.

After the treatment, cells were collected and density was maintained at around 0.5 × 106 cells/ml in each tube. Cells were lysed with 50 µl of cell lysis buffer (tris-buffered saline containing detergent) on ice for 10 min to extract proteins. This was followed by centrifugation at 10,000×g for 1 min. Supernatants from each sample were carefully transferred to 96-well plate. Protein concentrations in each well were measured by Bradford’s assay and samples having concentrations more than 200 µg/ml were diluted. Reaction mixture was prepared by mixing 2× reaction buffer (containing buffered saline, glycerol and detergent) with 2 µl dithiothreitol. 50 µl of the prepared reaction mix along with 5 µl of DEVD-pNA composed of the chromophore, p-nitroanilide (pNA), and a synthetic tetrapeptide, DEVD (Asp-Glue-Val-Asp) substrate were added in each sample. Plates were incubated in dark for 2 h at 37 °C and the absorbance was measured at 405 nm in a micro-plate reader (Biotek, India; Model no- ELx800).

Apoptosis related gene expression profiling: RNA extraction and quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

MCF-7 cells were cultured in 100 mm petri dishes at the density of 1.0 × 106 cells/ml and subsequently treated with earlier mentioned concentrations of TT leaf and seed extracts. After treatment, RNA isolation was carried out as per the manufacturer’s instruction using TRI reagent (TRizol, Sigma Aldrich). RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically and cDNA was reverse transcribed using GeNeifirst strand cDNA synthesis kit (India). PCR was performed using specific primers for Bcl-2, Bax, p53, Caspase 3, Caspase 8, FADD, AIF, and β-actin genes (Zhang et al. 2005). PCR products were electrophoresed on 2% agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Quantified transcripts of β-actin were used as endogenous RNA controls. All experiments were performed in duplicate for each data point.

Immunocytochemistry for Bax and Bcl-2

The expression of Bax and Bcl-2 protein was studied by immunocytochemistry using FITC (Fluorescein isothiocyanate tagged) specific antibodies. Briefly, cells were cultured on coverslips placed in 6-well plates at the cell density of 1 × 106 cells/ml and treated with TT extracts. Following drug treatment, cells were fixed and permeabilized as described previously (Vermeulen et al. 2005).This was followed by the exposure of cells to 10% fetal bovine serum for 1 h at room temperature. Following instructions from the manufacturer, the cells were then incubated with anti-Bax and anti-Bcl-2 antibody (Thermofisher Scientific, Rockford, USA) at 1:100 concentration overnight at 4 °C. After incubation, cells were rinsed twice with PBS and incubated with a goat anti-mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, FITC (fluorescein isothiocyanate; Thermofisher Scientific, Rockford, USA)-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 h at 37 °C in the dark. After washing with PBS, cells were stained with Hoechst solution (1 µg/ml) for 30 min at 37 °C in dark. The coverslips were rinsed with PBS thrice to remove excess stain and observed under Fluorescence Microscope using UV excitation (Nikon Eclipse e200).

Statistical analysis

The values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) of independent experiments performed in triplicate. Values between groups were compared using Tukey’s comparison test. Values were considered significant if p < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed by means of In-Stat package for personal computers version 5 (GraphPad_Software, Inc., San Diego, USA). IC50 value was calculated by linear regression.

Results

Inhibition of MCF-7 cells’ proliferation

Cell viability was determined through МТТ assay. Antitumor activity was determined by IC50 value. It is the concentration of active compound needed to reduce the cell viability to 50%. The MTT assay was performed to determine the cytotoxic effect of Tribulus terrestris on MCF-7 cells. The leaf and seed methanolic extract of TT showed the highest reduction in cell viability up to 69.51 ± 2.21% (p < 0.05) at 12.5 µg/ml and 12.97 ± 0.896% (p < 0.05) at 25 µg/ml of extract. Saponin fractions of leaves and seeds showed cell viability up to 17.66 ± 1.115% (p < 0.05) and 13.50 ± 0.885% (p < 0.05) at 100 µg/ml and 6.25 µg/ml, respectively. Leaf saponin and seed saponin were demonstrated to have an IC50 value of 28.32 µg/ml and 41.23 µg/ml, respectively. The results suggest that saponin extracts have potential cell cytotoxic activity as compared to the methanolic extracts (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cytotoxicity activity of T. terrestris L extract against MCF-7 cell line by MTT assay

| Extract | Conc. (µg/ml) | Cell viability (%) | Inhibition (%) | IC50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seed methanol | 100 | 47.02 ± 0.863 | 52.97 ± 0.863*,a | |

| 50 | 24.68 ± 0.542 | 75.31 ± 0.542 | ||

| 25 | 12.97 ± 0.896 | 87.02 ± 0.896 | 12.19* | |

| 12.5 | 80.54 ± 1.78 | 19.45 ± 1.78*,c | ||

| 6.25 | 60 ± 2.60 | 40 ± 2.60*,d | ||

| Seed saponin | 100 | 17.66 ± 1.115 | 82.33 ± 1.115*,b | |

| 50 | 21.78 ± 0.5 | 78.21 ± 0.5*,b | ||

| 25 | 77.21 ± 1.55 | 22.78 ± 1.55*,c,d | 41.23* | |

| 12.5 | 75.45 ± 2.22 | 24.54 ± 2.22 | ||

| 6.25 | 53.74 ± 1.47 | 46.25 ± 1.47 | ||

| Leaf methanol | 100 | 98.46 ± 0.485 | 1.53 ± 0.485a,b | |

| 50 | 81.59 ± 1.25 | 18.40 ± 1.25*,b | ||

| 25 | 80.91 ± 2.36 | 19.08 ± 2.36*,b,c | 89.78* | |

| 12.5 | 69.51 ± 2.21 | 30.48 ± 2.21*,b,c | ||

| 6.25 | 79.03 ± 1.29 | 20.96 ± 1.29*,b,c | ||

| Leaf saponin | 100 | 67.92 ± 0.410 | 32.07 ± 0.410 | |

| 50 | 54.52 ± 1.405 | 45.47 ± 1.40*,b,d | ||

| 25 | 58.68 ± 1.405 | 41.31 ± 1.405 | 28.321* | |

| 12.5 | 25.47 ± 0.800 | 74.52 ± 0.800 | ||

| 6.25 | 13.50 ± 0.885 | 86.49 ± 0.885* |

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of independent experiments performed in triplicate. The values were significant at *p < 0.05 compared to control using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis (where means sharing same superscript are not statistically different)

PBMCs were isolated from the healthy individual to test the cytotoxicity of methanolic and saponin extract of Tribulus terrestris on normal cells. The percentage of viability obtained after 24 h exposure of 100 µg/ml concentration of leaf and seed methanolic extract was 146.66 ± 2.61% (p < 0.05) and 272.66 ± 1.29% (p < 0.05), respectively. Similarly, the leaf and seed saponin extract have shown viability of 249.33 ± 1.53% (p < 0.05) and 145.33 ± 1.98% (p < 0.05), respectively. These results suggest that Tribulus terrestris extracts were not cytotoxic to the normal cells (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cytotoxicity of Tribulus terrestris L. extracts against PBMCs

| Extract | Concentration (µg/ml) | % Cell viability | % Inhibition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf methanol | 100 | 146.66 ± 2.61 | − 46.66 ± 2.61 |

| 50 | 168 ± 0.50 | − 68 ± 0.50* | |

| 25 | 120.66 ± 1.50 | − 20.66 ± 1.50* | |

| 12.5 | 117.33 ± 1.61 | − 17.33 ± 1.61* | |

| 6.25 | 200 ± 7.11 | − 100 ± 7.11* | |

| Seed methanol | 100 | 272.66 ± 1.29 | − 172.66 ± 1.29* |

| 50 | 262.66 ± 1.35 | − 162.66 ± 1.35* | |

| 25 | 175.33 ± 1.50 | − 75.33 ± 1.50* | |

| 12.5 | 220 ± 6.06 | − 120 ± 6.06* | |

| 6.25 | 209.33 ± 1.51 | − 109.33 ± 1.51* | |

| Leaf saponin | 100 | 249.33 ± 1.53 | − 149.33 ± 1.53* |

| 50 | 163.33 ± 1.975 | − 63.33 ± 1.975* | |

| 25 | 210 ± 3.185 | − 110 ± 3.185* | |

| 12.5 | 209.33 ± 1.58 | − 109.33 ± 1.58* | |

| 6.25 | 203.33 ± 1.795 | − 103.33 ± 1.795* | |

| Seed saponin | 100 | 145.33 ± 1.98 | − 45.33 ± 1.98* |

| 50 | 121.33 ± 3.47 | − 21.33 ± 3.47* | |

| 25 | 144 ± 2.55 | − 44 ± 2.55* | |

| 12.5 | 112 ± 1.17 | − 12 ± 1.17* | |

| 6.25 | 164.66 ± 1.84 | − 64.66 ± 1.84* |

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of independent experiments performed in triplicate. The values were significant at *p < 0.05 compared to control using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analysis (where means sharing same superscript are not statistically different)

Tribulus terrestris extract induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells

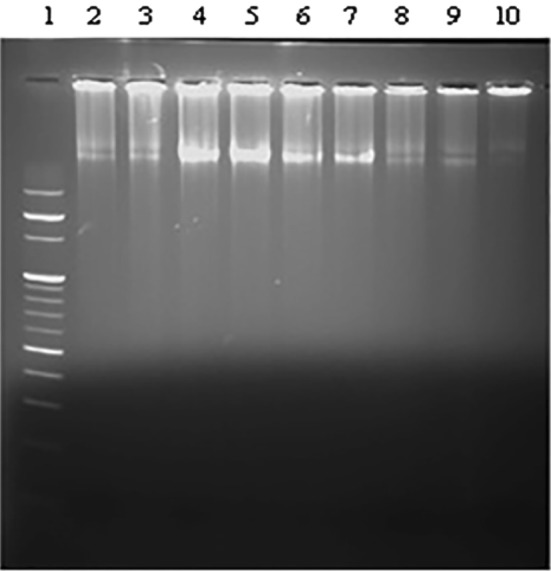

The DNA fragmentation assay was performed to delineate the mechanism of cell death in MCF-7 cells. After 9 days of treatment with selected concentrations of different extracts, DNA fragmentation was compared in all the treated samples and untreated control samples. Figure 1 shows the agarose gel of DNA from MCF-7 cells treated with two different concentrations of seed, leaf methanolic extract and seed and leaf saponin extract. DNA ladder formation which is indicative of DNA fragmentation was observed in MCF-7 cells.

Fig. 1.

MCF-7 cells were assayed for DNA fragmentation after treatment with Tribulus terrestris L. extracts. Lanes (1) 100 bp ladder. DNA from MCF-7 treated with (2) leaf methanol—25 µg/ml, (3) leaf methanol—12.5 µg/ml, (4) seed methanol—25 µg/ml, (5) seed methanol—12.5 µg/ml, (6) leaf saponin—12.5 µg/ml, (7) leaf saponin—12.5 µg/ml, (8) seed saponin—12.5 µg/ml, and (9) seed saponin—6.25 µg/ml. (10) DNA from untreated cells

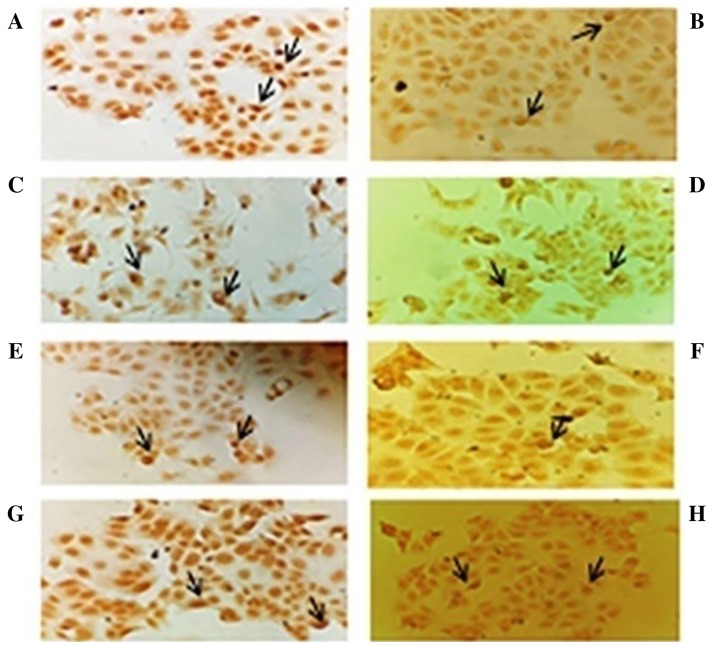

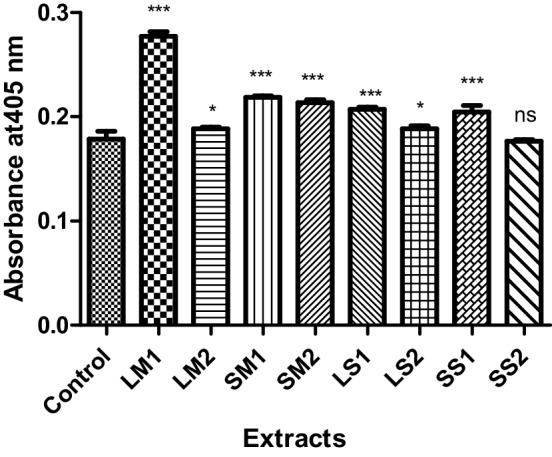

To further support the apoptotic mode of cell death in treated cells, TUNEL assay was performed. It was found that the cells treated with both methanolic and saponin extracts for 24 h exhibited apoptotic body formation (Fig. 2). Typical morphological features of apoptotic cells, viz., condensed and fragmented nuclei were observed in treated cells (Fig. 2).When compared to the control cells, 23.185 ± 1.86% and 25.68 ± 1.49% of the cells treated with 12.5 µg/ml leaf and seed methanolic extract, respectively, underwent apoptosis. Similarly, 27.39 ± 1.04% and 33.765 ± 0.875% of the cells treated with 12.5 µg/ml and 6.25 µg/ml of leaf and seed saponin extract, respectively, underwent apoptosis (Table 4). To elucidate the mechanism of cell death, the effect of TT extracts on caspase-3 is shown in Fig. 3. The assay was conducted to establish the levels of caspase-3 activation before and after the treatment. The caspase-3 activity was significantly higher in MCF-7 treated with different concentrations of TT extracts when compared to control untreated cells (p < 0.05). The highest caspase-3 activity was observed in 25 µg/ml of leaf methanol extract. However, the seed sapnonin extract at a concentration of 6.25 µg/ml did not show any significant change in caspase-3 activity (Fig. 3). The result suggests that treatment of MCF-7 cells with TT extracts strongly induces caspase-3 activity.

Fig. 2.

Morphological changes in nuclei of MCF-7 cells were observed upon treatment with TT extract as detected by TUNEL assay. a LM1 leaf methanol—25 µg/ml, b LM2 leaf methanol—12.5 µg/ml, c SM1 seed methanol—25 µg/ml, d SM2 seed methanol—12.5 µg/ml, e LS1 leaf saponin—12.5 µg/ml, f LS2 leaf saponin—6.25 µg/ml, g SS1 seed saponin—12.5 µg/ml, and h SS2 seed saponin—6.25 µg/ml

Table 4.

Percentage of apoptosis calculated by the TUNEL assay

| Extract | Concentration (µg/ml) | % Apoptosis |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 3.015 ± 0.567 | |

| Leaf methanol | 25 | 16.725 ± 1.55* |

| 12.5 | 23.185 ± 1.86* | |

| Seed methanol | 25 | 11.565 ± 0.59* |

| 12.5 | 25.68 ± 1.49* | |

| Leaf saponin | 12.5 | 27.39 ± 1.04* |

| 6.25 | 25.42 ± 1.25* | |

| Seed saponin | 12.5 | 21.97 ± 1.97* |

| 6.25 | 33.765 ± 0.88* |

Results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviation of independent experiments performed in triplicate

*The values are significant at p < 0.05 compared to control using one-way ANOVA

Fig. 3.

Caspase-3 activity in control and MCF7 cells treated with Tribulus terrestris extracts. The values are expressed as means ± SD (n = 4). ***p < 0.001 when compared to control. Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05 when compared to control. ns not significant, p > 0.05 when compared to control. Dunnett’s multiple comparison test

Tribulus terrestris extract-induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells by intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathway

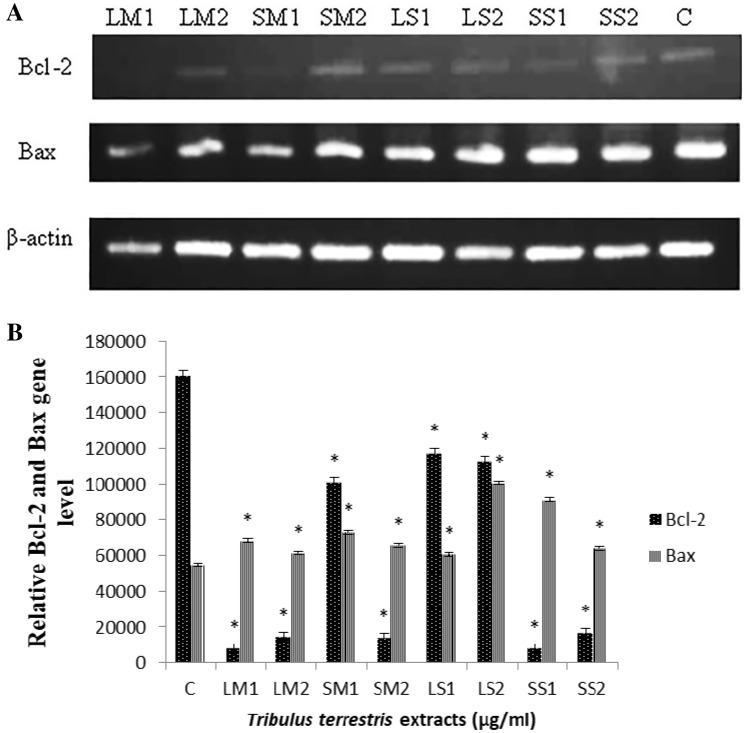

The ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 genes regulates the commitment of a cell towards the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Thus, Bax/Bcl-2 ratio can affect tumor progression and aggressiveness. Therefore, in the present study, we analyzed the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. The result suggests that there was a reduced expression of Bcl-2 gene in samples treated with 25 µg/ml of leaf and seed methanolic extract as compared to the control. Similarly, there was a reduction in the expression in samples treated with 12.5 µg/ml of leaf and seed saponin. Expression of Bax gene was upregulated in all the treated samples (Fig. 4). The results suggest that Bax/Bcl-2 gene ratio was altered in the MCF-7 cells treated with methanolic and saponin extracts of TT.

Fig. 4.

Tribulus terrestris extract alter the Bax/Bcl-2 ratio triggering intrinsic apoptotic pathway. a The mRNA levels of Bcl-2 and Bax gene as analyzed by qRT-PCR. b The mRNA levels of Bcl-2 and Bax as quantified by ImageJ software. The values are expressed as means ± SD where *p value < 0.05 was considered when compared with control using one-sample t test

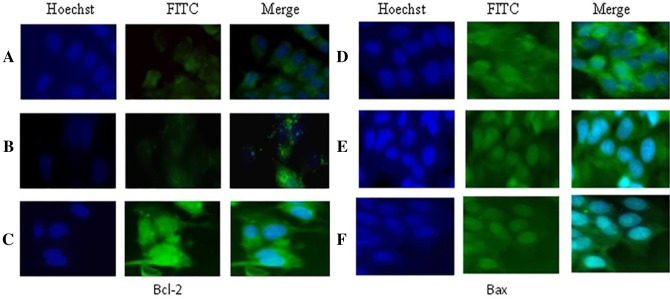

Bcl-2 and Bax protein levels in untreated and treated MCF-7 cells were studied using immunocytochemistry technique to examine the involvement of Bcl-2 family proteins in TT-mediated apoptosis. As shown in Fig. 5, TT extracts dramatically decreased the expression of Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic) protein, while there is no change in the expression of Bax (pro-apoptotic) protein. This resulted in increased Bax/Bcl-2 ratio.

Fig. 5.

Immunostaining for Bcl-2 and Bax protein in MCF-7 cells treated with Tribulus terrestris extract: a, d leaf saponin 25 µg/ml; b, e seed saponin 25 µg/ml; c, f control

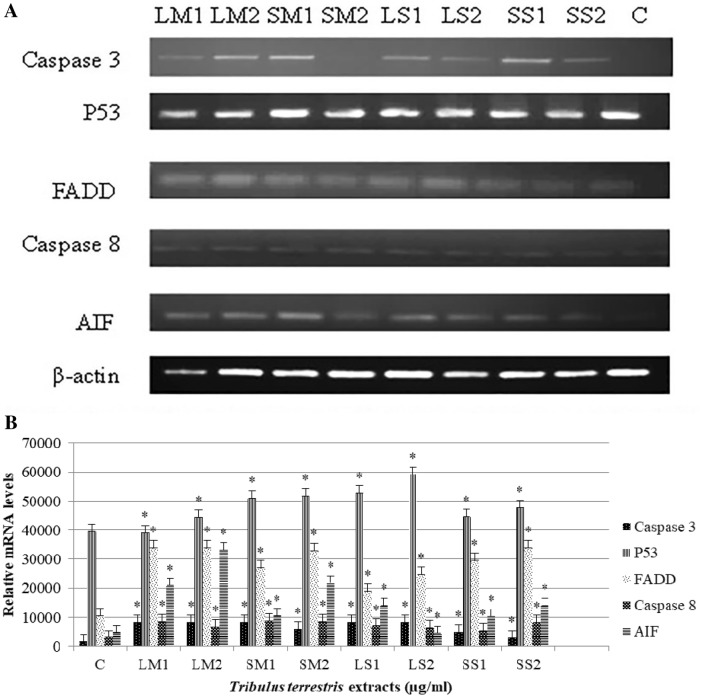

Similarly, expression of p53 and caspase 8 genes was also upregulated. The expression of caspase-3 was upregulated in all treated samples except in the sample treated with 12.5 µg/ml of seed methanolic extract as compared to the control (Fig. 6). Thus, the data suggests that saponin and methanolic extract of TT must have triggered the caspase-dependent pathway of apoptosis by activating both intrinsic and extrinsic pathway. Interestingly, expression of AIF gene was also altered. As compared to control, the expression of AIF in samples treated with 25 µg/ml seed methanolic extract showed the highest expression. This may suggest that TT saponin and methanolic extract may induce apoptosis also by caspase-independent pathway.

Fig. 6.

RT-PCR analysis of apoptosis-related genes revealed molecular mechanism of apoptosis. a The mRNA levels of caspase-3, p53, FADD, caspase 8 and AIF gene as analyzed by qRT-PCR. b. The mRNA levels of caspase-3, p53, FADD, caspase 8 and AIF as quantified by ImageJ software. The values are expressed as means ± SD where *p value < 0.05 was considered when compared with control using one-sample t test

Discussion

Breast cancer has been reported to affect 1.38 million women and accounts for about 14% of cancer deaths (458,000 women) each year (Jemal et al. 2011). In the present study, we analyzed the impact of the methanolic leaf and seed extracts as well as saponin from the leaves and seeds of TT on the expression of selected group of genes from apoptotic pathway in MCF-7 cells. Many naturally occurring substances exert anticancer effects by induction of apoptotic signaling (Sun et al. 2004a, b; Portt et al. 2011). Apoptosis results in morphological and biochemical alterations in the affected cells. These include DNA fragmentation, reduction of cell volume and membrane blebbing (Golshan et al. 2016).

Various mechanisms have been implicated in the biological activity of active fractions from the plants. Some of them include cytotoxicity, cytostaticity and/or with apoptosis (Angelova et al. 2013). Apoptosis is regulated through the action of several oncogenes and oncoproteins that exhibit an inhibiting or promoting action. Apoptosis, or programmed cell death, can be initiated either by intrinsic or extrinsic pathway. The trigger for the intrinsic pathway is mitochondrial permeabilization. On the other hand, the extrinsic pathway is triggered by activation of death receptors by their respective ligands. The present study demonstrates that seed and leaves extracts of TT exhibited an inhibitory effect on the viability of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Similar results have been reported by Angelova et al. (2013). MCF-7 cell DNA was shown to be susceptible to fragmentation by the methanolic extracts from the seed and leaf extracts of TT. The reported IC50 values have wide variation in literature. This may be due differences in the geographical location of the plants.

Bcl-2 is a gene located at chromosome 18q21, codes a 26-kD protein that blocks programmed cell death without affecting cellular proliferation (Hockenbery et al. 1990). In several malignant tumors, Bcl-2 expression has been associated with a favorable clinical outcome (Doglioni et al. 1994). Bax is Bcl-2-associated protein X which promotes apoptosis (Oltvai et al. 1993).The susceptibility of cells to apoptosis is determined by Bax to Bcl-2 ratio. Cells with increased susceptibility to apoptosis over express Bax resulting in increased bax homodimers (Yang and Korsmeyer 1996).The variations in the level of both Bcl-2 and Bax mRNA in MCF-7 cells when compared to control cells confirmed that Bcl-2 and Bax were altered by TT extracts. In the present study, all the extracts of TT caused significant increase in Bax gene levels and decrease in Bcl-2 levels when compared to control cells. This may suggest a pro-apoptotic tendency induced by TT extracts in MCF-7 cells (Kulsoom et al. 2018). The product of Bcl-2 gene is a mitochondrial membrane apoptosis-blocking protein. It has been reported to be over-expressed in many types of cancers (Schorr et al. 1999; Singh and Saini 2012). The decrease in Bcl-2 levels is in agreement with earlier studies (Angelova et al. 2013).

Fas-associated protein with death domain (FADD) is a 28-kDa adaptor protein that is an important component of the death receptors’ apoptotic signaling pathway (Fantl et al. 1993; Gibcus et al. 2007). It initiates the formation of a death-inducing signaling complex and is also a docking site for caspase-8. In this study, the mRNA levels of FADD, caspase-8 and caspase-3 were significantly elevated by the extracts of TT indicating the probable triggering of extrinsic apoptotic pathway. Caspase-8 causes the activation of proenzyme caspase-3 to its active form by cleaving it into subunits and their dimerization (Basaiyye et al. 2017). Caspase-3 is essential for the cleavage of DNA in cancer cells (Cucina et al. 2009).

DNA fragmentation has been postulated to occur in later stages of apoptosis (Johnson et al. 2000). Similar results for induction of apoptosis have been reported for the Chinese herb T. terrestris on different types of cancer cell lines (Hu and Yao 2003; Sun et al. 2003, 2004). In apoptosis, the cellular endonucleases are activated which cause the fragmentation of the DNA. In the present study, seed and leaf extracts of TT in methanol as well as saponins from seeds and leaves caused DNA fragmentation in MCF-7 cells but not in PBMCs. This may be indicative of apoptosis in MCF-7 cells. Apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) is a flavin adenine dinucleotide-containing, NADH-dependent oxidoreductase present in the intermembrane space of the mitochondria. Apoptotic assault results in the proteolysis of AIF followed by its translocation to the nucleus where it causes chromatin condensation and large-scale DNA degradation in a caspase-independent manner (Sevrioukova 2011). In our study, there was a significant increase in Bcl-2/Bax ratio indicating involvement of the Bcl-2 family proteins in apoptosis mediated by TT extracts. Studies by Cucina et al. (2009) have shown a similar increase in MCF-7 cells treated with melatonin. Apoptic mechanisms mediated by Bcl-2 and Bax are modulated by p53and p57 (Siewe 2007). The p53 tumor suppressor is sequence-specific transcription factor found in low levels in healthy cells. p53 activation results in apoptosis which may be induced either through the mitochondrial pathway or the death receptor pathway (extrinsic pathway) (Amaral et al. 2010). p53 overexpression has been reported to increase the expression of cell surface Fas, activate the death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL in response to DNA damage (Wu et al. 1997) and promote cell death through caspase 8. In the present study, the level of p53 mRNA was significantly increased in all the MCF-7 cells treated with various TT extracts indicating the induction of apoptosis. In this study, TT-treated MCF-7 cells showed a significant increase in p53 indicating its activation in early apoptosis (Cucina et al. 2009).

Conclusion

The present study suggests that TT extracts may exert their anticancer effect by triggering more than one apoptotic pathway.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr.Gaurav Shastri (Gene care Lab, Surat, Gujarat, India) for assisting in fluorescence microscopy. The study was supported by Grant of the Gujarat Council of Science & Technology (GujCOST), Department of Science and Technology, Gujarat, India to AS and PS.

Author contributions

AP did the experiments and analyzed the data. AS and PS designed the study and applied for grant. NJS wrote the manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Apurva Patel, Email: patelapurva1716@gmail.com.

Anjali Soni, Email: anjalisoni@vnsgu.ac.in.

Nikhat J. Siddiqi, Email: nikhat@ksu.edu.sa

Preeti Sharma, Email: preetisharma@vnsgu.ac.in.

References

- Amaral JD, Xavier JM, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. The role of p53 in apoptosis. Discov Med. 2010;9:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelova S, Gospodinova Z, Krasteva M, Antov G, Lozanov V, et al. Antitumor activity of Bulgarian herb Tribulus terrestris L. on human breast cancer cells. J Biosci Biotechnol. 2013;2:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Basaiyye SS, Naoghare PK, Kanojiya S, Bafana A, Arrigo P, Krishnamurthi K, Sivanesan S. Molecular mechanism of apoptosis induction in Jurkat E6-1 cells by Tribulus terrestris alkaloids extract. J Tradit Complement Med. 2017;8:410–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedir E, Khan IA, Walker LA. Biologically active steroidal glycosides from Tribulus terrestris. Pharmazie. 2002;57:491–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breast cancer: Prevalence, statistics, and risk factors (2012). https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317135.php. Accessed 3 Oct 2018

- Comşa Ş, Cîmpean AM, Raica M. The story of MCF-7 breast cancer cell line: 40years of experience in research. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:3147–3154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucina A, Proietti S, D’Anselmi F, Coluccia P, Dinicola S, Frati L, Bizzarri M. Evidence for a biphasic apoptotic pathway induced by melatonin in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. J Pineal Res. 2009;46(2):172–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni C, Dei Tos AP, Laurino L, Chiarelli C, Barbareschi M, Viale G. The prevalence of bcl-2 immunoreactivity in breast carcinomas and its clinicopathological correlates, with particular reference to estrogen receptor status. Virchows Arch. 1994;424:47–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00197392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantl V, Smith R, Brookes S, Dickson C, Peters G. Chromosome 11q13 abnormalities in human breast cancer. Cancer Surv. 1993;18:77–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibcus JH, Menkema L, Mastik MF, Hermsen MA, de Bock GH, van Velthuysen ML, Takes RP, Kok K, Marcos CA, van der AlvarezLaan BF, et al. Amplicon mapping and expression profiling identify the Fas-associated death domain gene as a new driver in the 11q13.3 amplicon in laryngeal/pharyngeal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6257–6266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golshan A, Amini E, Emami SA, Asili J, Jalali Z, Sabouri-Rad S, Sanjar-Mousavi N, Tayarani-Najaran Z. Cytotoxic evaluation of different fractions of Salvia chorassanica Bunge on MCF-7 and DU 145 cell lines. Res Pharm Sci. 2016;11:73–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JG, Quinn ML, Fabricant DS, Fransworth NR. Plants used against cancer-an extension of the work of Jonathan Hartwell. J Ethanopharmocol. 2000;73:347–377. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00341-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockenbery D, Nunez G, Milligan C, Schreiber RD, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 is an inner mitochondrial membrane protein that blocks programmed cell death. Nature. 1990;348:333–336. doi: 10.1038/348334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi N, Nakagawa K, Sasaki Y, Minato K, Fujiwara Y, Nezu K, Ohe Y, Saijo N. In vitro antitumor activity of mitomycin C derivative (RM-49) and new anticancer antibiotics (FK973) against lung cancer cell lines determined by tetrazolium dye (MTT) assay. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1988;22:246–250. doi: 10.1007/BF00273419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Yao X. The cytotoxicity of methyl protodioscin against human cancer lines in vitro. Cancer Investig. 2003;21:389–393. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120018230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–69. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VL, Ko SC, Holmstrom TH, Eriksson JE, Chow SC. Effector caspases are dispensable for the early nuclear morphological changes during chemical-induced apoptosis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2941–2953. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.17.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Kim JC, Min JS, et al. Aqueous extract of Tribulus terrestris Linn induces cell growth arrest and apoptosis by down-regulating NF-κB signaling in liver cancer cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2011;136:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.04.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulsoom B, Shamsi TS, Afsar NA, Memon Z, Ahmed N, Hasnain SN. Bax, Bcl-2, and Bax/Bcl-2 as prognostic markers in acute myeloid leukemia: are we ready for Bcl-2-directed therapy? Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:403–416. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S154608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix M, Haibe-Kains B, Hennuy B, Laes JF, Lallemand F, Gonze I, et al. Gene regulation by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231, two breast cancer cell lines exhibiting highly different phenotypes. Oncol Rep. 2004;12:701–707. doi: 10.3892/or.12.4.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neychev VK, Nikolova E, Zhelev N, Mitev VI. Saponins from Tribulus terrestris L are less toxic for normal human fibroblasts than for many cancer lines: influence on apoptosis and proliferation. Exp Biol Med. 2007;232:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noomhorm N, Chang CJ, Wen CS, Wang JY, Chen JL, Tseng LM, Chen WS, Chiu JH, Shyr YM. In vitro and in vivo effects of xanthorrhizol on human breast cancer MCF-7 cells treated with tamoxifen. J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;125:375–385. doi: 10.1254/jphs.14024FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obadoni BO, Ochuko PO. Phytochemical studies and comparative efficacy of the crude extracts of some homeostatic plants in Edo and delta states of Nigeria. Glob J Pure Appl Sci. 2001;8:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Oltvai Z, Milliman C, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conversed homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell. 1993;74:609–619. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90509-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portt L, Norman G, Clapp C, Greenwood M, Greenwood MT. Anti-apoptosis and cell survival: a review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:238–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorr K, Li M, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Furth PA. Bcl-2 gene family and related proteins in mammary gland involution and breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 1999;4:153–164. doi: 10.1023/A:1018773123899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevrioukova IF. Apoptosis-inducing factor: structure, function, and redox regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:2545–2579. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siewe T. The p53 family in differentiation and tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:165–168. doi: 10.1038/nrc2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R, Saini N. Downregulation of BCL2 by miRNAs augments drug-induced apoptosis—a combined computational and experimental approach. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1568–1578. doi: 10.1242/jcs.095976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su L, Chen G, Feng SG, Wang W, Li ZF, Chen H, Liu YX, Pei YH. Steroidal saponins from Tribulus terrestris. Steroids. 2009;74:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Qu W, Baiet Z. The inhibitory effect of saponins from Tribulus terrestris on Bcap-37 breast cancer line in vitro. Zhong Yao Cai. 2003;26:104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SY, Hail N, Lotan RJ. Apoptosis as a novel target for cancer chemoprevention. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;4:662–672. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B, Qu WJ, Zhang XL. Ivestigation on inhibitory and apoptosis-inducing effects of saponins from Tribulus terrestris on hepatoma cell line BEL-7402. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2004;29:681–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen K, Van Bockstaele DR, Berneman ZN. Apoptosis: mechanisms and relevance in cancer. Ann Hematol. 2005;84(10):627–639. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu GS, Burns TF, McDonald ER, 3rd, Jiang W, Meng R, Krantz ID, Kao G, Gan DD, Zhou JY, Muschel R, Hamilton SR, Spinner NB, Markowitz S, Wu G, el-Deiry WS. KILLER/DR5 is a DNA damage-inducible p53-regulated death receptor gene. Nat Genet. 1997;17:141–143. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang E, Korsmeyer S. Molecular thanatopsis: a discourse on the BCL2 family and cell death. Blood. 1996;88:386–401. doi: 10.1182/blood.V88.2.386.bloodjournal882386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JD, Coa YB, Xu Z, Sun HH, An MM, Yan L, Chen HS, Gao PH, Wang Y, Jia XM, Jian YY. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the eight steroid saponins from Tribulus terrestris L, with potent activity against fluconazole-resistant fungal pathogens. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:2211–2215. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]