Abstract

Introduction:

There is a subset of patients who initially had implant based breast reconstruction but later change to autologous reconstruction after failure of the implant reconstruction. The purpose of this study was to examine our series of patients in whom autologous reconstruction was performed after initial failed implant reconstruction, using the BREAST-Q to examine patient satisfaction and quality of life.

Methods:

After Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective chart review of a prospectively maintained database was performed as well as evaluation of BREAST-Q surveys.

Results:

One hundred thirty-seven patients underwent autologous breast reconstruction following failed implant based reconstruction with 192 total flaps. Failure of implant reconstruction was defined as follows: capsular contracture causing pain and/or cosmetic deformity (n=106, 77%), dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result without capsular contracture (n=15, 11%), impending exposure of the implant/infection (n=8, 6%), and unknown (n=8, 6%). Complications requiring operative intervention included: partial flap loss (n=5, 3%), hematoma (n=5, 3%), vascular compromise requiring intervention for salvage (n=2, 1%), and total flap loss (n=1, 1%). Thirty-four patients (23%) had BREAST-Q surveys available for analysis both during implant and autologous phases of reconstruction. There was a statistically significant increase in satisfaction with appearance of breasts(p<0.001), psychosocial well-being(p<0.001), and physical well-being of the chest(p=0.003). Satisfaction with overall outcomes also significantly increased(p<0.001). A statistically significant decrease in physical well-being of the abdomen was observed(p=0.001).

Conclusion:

Autologous breast reconstruction after failed implant based reconstruction is associated with significantly improved patient satisfaction and quality of life. The procedure has an acceptable complication rate.

Introduction

Following mastectomy, patients have the choice to undergo autologous or implant based breast reconstruction. Multiple studies debate the superiority of each method of reconstruction in terms of patient satisfaction and quality of life. Satisfaction with breasts, sexual and psychosocial well-being and overall outcome are higher with autologous breast reconstruction compared to implant based reconstruction1–6. Other studies show implant based reconstruction also has high patient satisfaction7.

While either implant based or autologous reconstruction can have high satisfaction rates, there is a subset of patients who initially chose implant based reconstruction but decide later to change to autologous reconstruction due to failure of the implant based reconstruction. Few papers have examined this population8,9. Visser et al. note that autologous reconstruction after implant based reconstruction is a safe procedure with low complication rate and common motivations for changing from implant to autologous breast reconstruction include: physical pain or tightness, dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result, and technical failure requiring removal of the implant due to infection8. They also report that patient satisfaction and quality of life improve after autologous breast reconstruction, but this data was based on an invalidated survey tool that patients completed retrospectively8. Therefore, the aim of this study is to examine our series of patients in which implant based reconstruction failed and subsequently autologous tissue reconstruction was performed, with a focus on examining satisfaction and quality of life using the validated BREAST-Q. Secondary aims include: examining motivations for changing to autologous tissue, evaluating the surgical success of the procedure and analyzing factors that may influence outcomes such as age, BMI, laterality and radiation.

Methods

After Institutional Review Board approval, a retrospective chart review of a prospectively maintained database was performed for patients who underwent autologous breast reconstruction following failed implant based reconstruction between January 1997 and July 2017. Patients included were those who initially received delayed or immediate implant-based reconstruction after mastectomy and who ultimately changed to an autologous reconstruction. Anyone undergoing a mixed approach to reconstruction (bilateral reconstruction with unilateral implant and unilateral flap, or latissimus flap plus implant) were excluded from analysis. All autologous tissue reconstructions were performed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Some patients underwent initial implant based reconstructions and revisions at other institutions.

Demographic information including age, body mass index, lymph node procedures (sentinel node biopsy versus axillary lymph node dissection), comorbidities (smoking, diabetes mellitus), radiation (before, during or after reconstruction), and chemotherapy were recorded. Failure of implant reconstruction was defined as follows: implant exposure/infection, capsular contracture causing physical pain and/or unsatisfactory appearance, or unsatisfactory appearance without known capsular contracture. Surgical details including any revisions to either implant based reconstruction or autologous reconstruction, laterality of the reconstruction, flap type and complications after autologous reconstruction were also recorded.

Available prospectively completed BREAST-Q questionnaires were analyzed at two different time points: after implant based reconstruction but prior to autologous breast reconstruction, and postoperatively following autologous breast reconstruction. For the first time point, the post-implant survey was used to assess satisfaction with breast appearance, psychosocial well-being, physical well-being of the chest and upper body, sexual well-being, and satisfaction with overall outcome. For each patient, the survey completed closest to autologous tissue reconstruction was used for analysis. The pre-operative autologous tissue reconstruction survey was used if a post-implant survey was not available. To analyze physical well-being of the abdomen, only the pre-operative autologous tissue reconstruction survey was used as the implant based survey does not have this category of questions. For the second time point, the post-operative autologous tissue based reconstruction surveys were analyzed. The potential effect of age, BMI, radiation or laterality (unilateral versus bilateral) on overall satisfaction with the reconstruction was an additional outcome measure. BREAST-Q surveys are routinely distributed in office pre-operatively and post-operatively at 1 week, 3 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and yearly. For each patient, the most recent survey was used in analysis.

The BREAST-Q is a Rasch-developed, validated survey instrument. Raw scores of 1 through 5 were converted with the Q-score software program to scores from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction or quality of life. Statistical analysis was performed using Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis to compare satisfaction and quality of life changes between survey time points. Student’s t-test and Pearson’s correlation coefficient were both used to analyze whether satisfaction with overall outcome was affected by radiation, laterality, age or BMI. Student’s t-test was also used to specifically analyze whether history of radiation had an effect on any category of satisfaction or well-being. Fischer’s exact test was used to examine potential associations with radiation and motivation for changing to autologous tissue. Student’s test and Pearson’s correlation coefficient tests were conducted with Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011, Version 4.7.3. Fischer’s exact and Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis were conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 1.0.0.950 was used for. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Summary and descriptive statistics were also used.

Results

One hundred thirty-seven patients underwent autologous breast reconstruction following failed implant based reconstruction. Demographic data are listed in Table 1. A representative patient is shown in Figure 1. Average age was 51.4 years (SD+/−8.9) and average BMI was 27.0 (SD+/−3.9). Eighty-two patients received radiation therapy to either their implant (n=58, 42%), tissue expander (n=19, 14%), or to their breast after lumpectomy and prior to completion mastectomy (n=5, 4%). Thirty-six patients (26%) had revisions to their implant based reconstruction prior to autologous reconstruction and nine patients (7%) had more than one revision. Revision procedures included: fat grafting (n=11), implant exchange with or without capsulectomy (n=21), implant removal with TE placement and subsequent exchange to implant (n=3), other revisions of shape (n=12) and seroma drainage (n=1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| Demographic | Number |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.4 (SD+/−8.9) |

| BMI | 27.0 (SD+/−3.9) |

| Smoking status | |

| Never | 83 (61%) |

| Former | 51 (37%) |

| Current | 3 (2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 8 (6%) |

| Chemotherapy | 93 (68%) |

| Radiation | 82 (60%) |

| Breast | 5 (4%) |

| Tissue expander | 19 (14%) |

| Implant | 58 (42%) |

BMI, body mass index. TE, tissue expander.

Figure 1.

55-year-old female with a history of left sided breast cancer treated with total mastectomy, axillary lymph node dissection, and chemotherapy. Top, pre-operative photographs prior to nipple-sparing mastectomy and tissue expander insertion. Middle, seven years after tissue expander exchange to implant. Patient suffered from Baker IV capsular contracture with nipple areolar complex malposition. Bottom, six months after removal of her implant and deep inferior epigastric flap reconstruction (right).

The reasons for failure of implant based breast reconstruction causing a change from an implant based reconstruction to autologous tissue included capsular contracture causing pain and/or cosmetic deformity (n=106, 77%), dissatisfaction with the aesthetic result without capsular contracture (n=15, 11%), impending exposure of the implant/infection (n=8, 6%), and unknown (n=8, 6%) (Table 2). Of the 106 patients with capsular contracture causing pain and/or cosmetic deformity, 47 patients had radiated implants, 14 had a radiated tissue expander and 5 had radiation to the breast after lumpectomy. Of the 15 patients without capsular contracture but with an unacceptable cosmetic result, 3 patients had radiation to their implants and 1 had radiation to the tissue expander. Of the 8 patients with impending implant exposure, 3 patients had radiation to the implant and 4 patients had radiated tissue expanders. Radiation did not significantly affect motivation for change to autologous reconstruction (p=1.0).

Table 2.

Motivations for change from implant based reconstruction to autologous breast reconstruction and radiation breakdown.

| Motivation | Number (% of total patients) | Radiated (% of each category) | Radiation to |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsular contracture causing pain or aesthetic deformity | 106 (77%) | 66 (62%) | Breast 5 |

| TE 14 | |||

| Implan 47 | |||

| Aesthetic concern without capsular contracture | 15 (11%) | 4 (27%) | Breast 0 |

| TE 1 | |||

| Implant 3 | |||

| Implant exposure, impending exposure or infection | 8 (6%) | 7 (88%) | Breast 0 |

| TE 4 | |||

| Implant 3 | |||

| Unknown | 8 (6%) | 5 (63%) | Breast 0 |

| TE 0 | |||

| Implant 5 |

TE, tissue expander.

Fifty-five cases were bilateral (40%) and 82 were unilateral (60%) for 192 total flaps (Table 3). Time from implant placement to implant removal and autologous reconstruction averaged 53 months (SD+/−43). Flap types included: deep inferior epigastric perforator flap (n=92, 48%), muscle sparing transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap (n=79, 41%), pedicled transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap (n=13, 7%), superior gluteal artery perforator flap (n=4, 2%) and diagonal upper gracilis flap (n=4, 2%). Complications requiring operative intervention included: partial flap loss (n=5, 3%), hematoma (n=5, 3%), vascular compromise requiring intervention for salvage (n=2, 1%), and total flap loss (n=1, 1%). Complications not requiring operative intervention included: minor wound healing of the donor site (n=4, 2%), seroma of abdomen or breast (n=4, 2%) and cellulitis of the abdomen (n=2, 1%). Forty-six patients (34%) had operative revisions to their autologous breast reconstruction with 12 patients (9%) having more than one procedure. Nipple areola complex reconstruction was not included in analysis. Operative revisions to autologous breast reconstruction included revision of shape (n=30, 22%), fat grafting (n=19, 14%), debulking liposuction (n=9, 7%), placement of implant to increase volume (n=3, 2%), and placement of latissimus flap to increase volume (n=2, 1%).

Table 3.

Autologous tissue base reconstruction surgical details.

| Surgical detail | Number (n=192) |

|---|---|

| Laterality | |

| Bilateral | 55 (40%) |

| Unilateral | 82 (60%) |

| Flap | |

| DIEP | 92 (48%) |

| msTRAM | 79 (41%) |

| pedicled TRAM | 13 (7%) |

| SGAP | 4 (2%) |

| DUG | 4 (2%) |

| Complications requiring operative intervention | |

| Partial flap loss | 5 (3%) |

| Hematoma | 5 (3%) |

| Vascular compromised requiring intervention for salvage | 2 (1%) |

| Total flap loss | 1 (<1%) |

| Complications not requiring operative intervention | |

| Minor wound healing of the donor site | 4 (2%) |

| Seroma of abdomen or breast | 4 (2%) |

| Cellulitis of the abdomen | 2 (1%) |

DIEP, deep inferior epigastric perforator flap. msTRAM, muscle sparing transverse rectus abdominus myocutaneous flap. SGAP, superior gluteal artery perforator flap. DUG, diagonal upper gracilis flap.

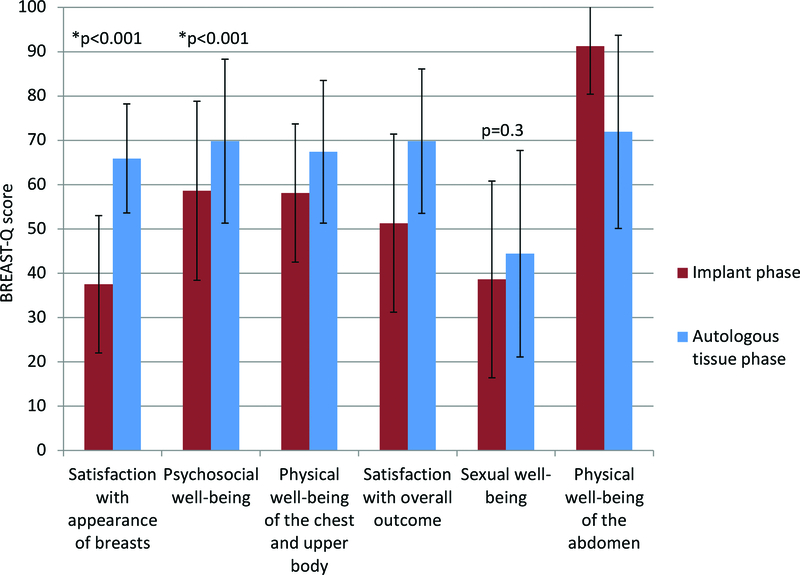

When comparing BREAST-Q responses between post implant based reconstruction but before autologous breast reconstruction and after autologous breast reconstruction, there were multiple statistically significant results. Thirty-four patients (23%), had questionnaires available at both time points for analysis. There was a statistically significant increase in satisfaction with appearance of breasts (p<0.001), psychosocial well-being (p<0.001), and physical well-being of the chest and upper body (p=0.003). Satisfaction with overall outcomes was also significantly increased (p<0.001). Changes in sexual well-being were not statistically significant (p=0.3). A statistically significant decrease in physical well-being of the abdomen was also observed (p=0.001). Only patients with abdominal flaps were included in the analysis of abdominal well-being (n=33). (Figure 2). Increased BMI, or laterality did not influence overall satisfaction to a significant degree. Additionally, patients with a history of radiation did not have any significant differences with satisfaction or well-being in any category. Post-operative implant/pre-operative autologous tissue reconstruction BREAST-Q surveys were filled out an average of 4.0 months (range <1–27, SD +/−5.8) prior to flap reconstruction. Average follow up with post-operative autologous tissue reconstruction BREAST-Q data available was 15 months (range 1.5–36, SD +/−11)

Figure 2.

BREAST-Q data. All measured parameters significantly improved between post implant and prior to autologous tissue, and post autologous tissue except for sexual well-being (not significant) and abdominal well-being (significantly decreased).

Discussion

Breast reconstruction after mastectomy, either implant based or autologous, is becoming more popular with 109,256 procedures reported in 201610. A large majority of these procedures, over 80%, are implant based. Generally, implant reconstruction is a simpler procedure and is available to more patients. Autologous reconstruction is performed less often, as not all patients are candidates and the complexity of the procedure is greater. The procedures are longer and have the addition of donor site morbidity. However, autologous tissue can provide a more naturally shaped breast and eliminate the long-term risks of capsular contracture and implant infection/exposure, which are associated with implant-based reconstruction. Both implant and autologous tissue reconstruction have a high degree of patient satisfaction and quality of life1–7.

While multiple studies exist examining either implant reconstruction or autologous reconstruction, few studies investigate the subset of patients in whom implant based reconstruction failed and autologous tissue reconstruction was ultimately performed8,9. In the few existing studies, a high degree of patient satisfaction is reported, yet none utilize a validated patient reported outcomes tool in their assessment. Our study used the validated BREAST-Q. This is a patient reported tool and was completed prospectively.

Our results show a high degree of satisfaction and quality of life. Significant increases were seen in satisfaction with breast appearance, psychosocial well-being, and physical well-being of the chest and upper body. Improvements in physical well-being of the chest and upper body in many patients could be due to removal a tight implant and firm, painful capsule at the time of autologous tissue reconstruction. Even those that did not perceive pain or tightness when their implants were in place may see improvement when they are removed, as they now have a comparison. Interestingly, patients have a persistent decrease in physical well-being of their abdomen, even at an average follow up of 15 months. However, satisfaction with overall outcome is still significantly improved. Therefore, we can infer that while patients do recognize physical impairment of the abdomen, this is not enough to affect their overall satisfaction with autologous reconstruction. This is an important consideration for preoperative counseling with respect to expected outcomes and the decision to proceed with autologous tissue reconstruction.

Satisfaction and quality of life in breast reconstruction may be influenced by multiple factors including BMI, laterality and radiation. A higher BMI and reconstruction in the setting of radiation can relate to lower satisfaction and quality of life11–13. Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy with bilateral reconstruction can relate to higher satisfaction with breasts when compared to unilateral reconstruction14. Age has not been shown to impact satisfaction and quality of life, however, we wanted to include this parameter in our examination for completeness6,15. Our study did not show any impact of age, BMI, laterality or radiation in terms of satisfaction with overall outcome. Hence, patients who desire implant removal and autologous tissue reconstruction should not be dissuaded based on age, BMI, laterality or radiation.

We defined reconstructive failure as either an implant loss due to complication (infection, exposure, capsular contracture) or patient driven motivation due to dissatisfaction with the implant based reconstruction. In this study, reconstructive failure was largely due to the pain and aesthetic deformity caused by capsular contracture (77%). Incidence of capsular contracture in implant based reconstruction in patients without radiation is low, with a recent study observing Baker III/IV capsular contracture in 4% of patients16. The incidence increases in the setting of radiation. A recent meta-analysis showing Baker III/IV capsular contracture of 37.5% in a pooled analysis of radiation applied to either tissue expanders or implants17. Rates of capsular contracture can also vary depending on whether the implant or tissue expander was radiated. Cordeiro et al observed Baker III/IV capsular contracture in 17% of patients who had radiation to their tissue expander versus 51% of patients who had radiation to their implant16. Of the 106 patients whose motivation was capsular contracture, a majority (62%) had prior radiation. Additionally, many of those patients had radiation to their implant. The use of implant-based reconstruction in the setting of radiation is beyond the scope of this paper. Other reasons for failure included impending implant exposure/infection and aesthetic concerns with no capsular contracture.

Regardless of reason for implant failure, this study shows changing to autologous tissue after implant removal is safe. Autologous tissue reconstruction may be more challenging in this patient population due to increased scarring in patients with capsular contracture and/or vascular changes seen in patients with radiation. However, the complication rates observed in this study are similar to those described in the literature. Largo et al report a total flap loss rate of 1% in a series of 7443 free flaps for breast reconstruction18. Our study had only one flap loss of 192 flaps for a rate of less than 1%.

The average time from implant placement to implant removal and autologous tissue reconstruction was three and a half years. Many patients with implant based reconstruction may be satisfied initially, but as time goes on, become dissatisfied with the result. A study of 219 patients found that in the longer post reconstructive period (>5years), those with implant based reconstruction become more dissatisfied with their breasts compared to those with autologous reconstruction19. The reasons for this are multifactorial but may include changes in body habitus, implant malposition, progressive effects of radiation or development of capsular contracture over time. Yearly follow up beyond just the initial post reconstruction phase may be important to capture these patients.

This study has several limitations. This is a retrospective review of prospectively collected data and patient numbers are limited. Additional studies with a larger sample size are needed to verify these findings. Further, our BREAST-Q completion rate for both time points of the study is low (23%). Later in the series, from 2011 to present time, there was a much greater compliance with the BREAST-Q, however the overall completion rate is low and as such, there may be an element of selection bias in this study. While the average follow up post autologous tissue reconstruction was 15 months, longer follow up is needed to determine whether satisfaction or well-being change, especially the decrease in physical well-being of the abdomen. Lastly, the BREAST-Q survey does not address the donor site in patients whom had flaps from other donor sites beside the abdomen. Our study had six such patients.

Conclusion

Autologous breast reconstruction after failed implant based reconstruction is motivated largely by capsular contracture causing either pain and/or aesthetic deformity and is a safe procedure with a low complication rate. Satisfaction and quality of life have found to be significantly improved using a validated survey tool.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this article.

IRB Approval

The following study was conducted under Institutional Review Board Approval at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

References

- 1.Pusic AL, Matros E, Fine N, Buchel E, Gordillo GM, Hamill JB, Kim HM, Qi J, Albornoz C, Klassen AF, Wilkins EG. Patient-Reported Outcomes 1 Year After Immediate Breast Reconstruction: Results of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017. August 1;35(22):2499–2506. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.9561. Epub 2017 Mar 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eltahir Y, Werners LL, Dreise MM, Zeijlmans van Emmichoven IA, Werker PM, de Bock GH. Which breast is the best? Successful autologous or alloplastic breast reconstruction: patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015. January;135(1):43–50. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pirro O, Mestak O, Vindigni V, Sukop A, Hromadkova V, Nguyenova A, Vitova L, Bassetto F Comparison of Patient-reported Outcomes after Implant Versus Autologous Tissue Breast Reconstruction Using the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2017. January 25;5(1):e1217. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000001217. eCollection 2017 Jan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sgarzani R, Negosanti L, Morselli PG, Vietti Michelina V, Lapalorcia LM, Cipriani R. Patient Satisfaction and Quality of Life in DIEAP Flap versus Implant Breast Reconstruction. Surg Res Pract. 2015;2015:405163. doi: 10.1155/2015/405163. Epub 2015 Nov 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weichman KE1, Broer PN, Thanik VD, Wilson, Tanna N, Levine JP, Choi M, Karp NS, Hazen A Patient - Reported Satisfaction and Quality of Life following Breast Reconstruction in Thin Patients: A Comparison between Microsurgical and Prosthetic Implant Recipients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015. August;136(2):213–20. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alderman Amy K.; Wilkins Edwin G.; Lowery Julie C.; Myra Kim; Davis Jennifer A. Determinants of Patient Satisfaction in Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction. Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery: September 2000. - Volume 106 - Issue 4 - pp 769–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aguiar IC, Veiga DF, Marques TF, Novo NF, Sabino Neto M, Ferreira LM. Patient-reported outcomes measured by BREAST-Q after implant-based breast reconstruction: A cross-sectional controlled study in Brazilian patients. Breast. 2017. February;31:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.008. Epub 2016 Oct 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visser NJ, Damen TH, Timman R, Hofer SO, Mureau MA. Surgical results, aesthetic outcome, and patient satisfaction after microsurgical autologous breast reconstruction following failed implant reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010. July;126(1):26–36. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181da87a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feng LJ, Mauceri K, Berger BE. Autogenous tissue breast reconstruction in the silicone-intolerant patient. Cancer. 1994. July 1;74(1 Suppl):440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society of Plastic Surgery Statistics Report. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2016/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2016.pdf. Accessed 11/19/2017.

- 11.Rojas KE, Matthews N, Raker C, Clark MA, Onstad M, Stuckey A, Gass J. Body mass index (BMI), postoperative appearance satisfaction, and sexual function in breast cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2017. October 17. doi: 10.1007/s11764-017-0651-y. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albornoz CR, Matros E, McCarthy CM, Klassen A, Cano SJ, Alderman AK, VanLaeken N, Lennox P, Macadam SA, Disa JJ, Mehrara BJ, Cordeiro PG, Pusic AL. Implant breast reconstruction and radiation: a multicenter analysis of long-term health-related quality of life and satisfaction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014. July;21(7):2159–64. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3483-2. Epub 2014 Apr 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson JA, Disa JJ. Breast Reconstruction and Radiation Therapy: An Update. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017. November;140(5S Advances in Breast Reconstruction):60S–68S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003943. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Momoh AO, Cohen WA, Kidwell KM, Hamill JB, Qi J, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG, Matros E. Tradeoffs Associated With Contralateral Prophylactic Mastectomy in Women Choosing Breast Reconstruction: Results of a Prospective Multicenter Cohort. Ann Surg. 2017. July;266(1):158–164. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sisco M, Johnson DB, Wang C, Rasinski K, Rundell VL, Yao KA.The quality-of-life benefits of breast reconstruction do not diminish with age. J Surg Oncol. 2015. May;111(6):663–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.23864. Epub 2015 Jan 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cordeiro PG, Albornoz CR, McCormick B, Hudis CA, Hu Q, Heerdt A, Matros E. What Is the Optimum Timing of Postmastectomy Radiotherapy in Two-Stage Prosthetic Reconstruction: Radiation to the Tissue Expander or Permanent Implant? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015. June;135(6):1509–1517. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ricci JA, Epstein S, Momoh AO, Lin SJ, Singhal D, Lee BT. A meta-analysis of implant-based breast reconstruction and timing of adjuvant radiation therapy. J Surg Res. 2017. October;218:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.05.072. Epub 2017 Jun 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Largo RD, Selber JC, Garvey PB, Chang EI, Hanasono MM, Yu P, Butler CE, Baumann DP. Outcome Analysis of Free Flap Salvage in Outpatients Presenting with MicrovascularCompromise. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018. January;141(1):20e–27e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu ES, Pusic AL, Waljee JF, Kuhn L, Hawley ST, Wilkins E, Alderman AK. Patient-reported aesthetic satisfaction with breast reconstruction during the long-term survivorship Period. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009. July;124(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ab10b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]