Abstract

Objectives

The significance of neutrophilic inflammation in obstructive airway disease remains controversial. Recent studies have demonstrated presence of an active neutrophil population in systemic circulation, featuring hypersegmented morphology, with high oxidative burst and functional plasticity in inflammatory conditions. The aim of this study was to characterise neutrophil subsets in bronchial lavage (BL) of obstructive airway disease participants (asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and bronchiectasis) and healthy controls on the basis of nuclear morphology and to assess the association between neutrophil subsets and the clinical parameters of the obstructive airway disease participants.

Design

A cross-sectional exploratory study.

Setting

John Hunter Hospital and Hunter Medical Research Institute, Australia.

Participants

Seventy-eight adults with obstructive airway disease comprised those with stable asthma (n=39), COPD (n=20) and bronchiectasis (n=19) and 20 healthy controls.

Materials and methods

Cytospins were prepared and neutrophil subsets were classified based on nuclear morphology into hypersegmented (>4 lobes), normal (2–4 lobes) and banded (1 lobe) neutrophils and enumerated.

Results

Neutrophils from each subset were identified in all participants. Numbers of hypersegmented neutrophils were elevated in participants with airway disease compared with healthy controls (p<0.001). Both the number and the proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils were highest in COPD participants (median (Q1–Q3) of 1073.6 (258.8–2742) × 102/mL and 24.5 (14.0–46.5)%, respectively). An increased proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils in airway disease participants was significantly associated with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity per cent (Spearman’s r=−0.322, p=0.004).

Conclusion

Neutrophil heterogeneity is common in BL and is associated with more severe airflow obstruction in adults with airway disease. Further work is required to elucidate the functional consequences of hypersegmented neutrophils in the pathogenesis of disease.

Keywords: immunology, bronchoscopy, chronic airways disease

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first exploratory study to characterise three morphologically different subsets of neutrophils in bronchial lavage of adults with obstructive airway disease and healthy controls.

The study investigated clinical association of neutrophil subset with airway obstruction.

The cross-sectional nature of study is a limitation in properly understanding the reason behind neutrophil heterogeneity in airways.

Introduction

Neutrophils are phagocytic innate immune cells which patrol the blood vessels and become activated in response to inflammatory triggers.1 Activation results in neutrophil migration to the site of infection, where pathogens can be eliminated by phagocytosis or NETosis.2 Similarly, infection or injury can result in the initiation of an innate immune response following the engagement of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns with pattern recognition receptors of airways. This facilitates the release of chemotactic stimuli such as CXCL8, interleukin-1β and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), resulting in neutrophil recruitment to the airways,3 which is important for the resolution of infection and inflammation.4 In contrast, a disproportionate or dysregulated influx or efflux of neutrophils can result in persistent neutrophilic airway inflammation and tissue damage.5

Inflammation characterised by airway neutrophilia is reported in many cases of chronic obstructive airway disease.6 This includes 20%–30% cases of asthma,7 more than 40% cases of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),8 9 and 70% cases of non-cystic fibrosis (CF) bronchiectasis.10 Current therapeutic and management strategies for asthma and COPD focus on bronchodilation to overcome airflow limitation, or inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)-based therapies for the modification of eosinophilic airway inflammation.11 12 In non-CF bronchiectasis, treatment relies on antibiotics to control the infective nature of the disease.13 While ICS are highly effective in modifying eosinophilic inflammation in the airways,14 there are no treatments that have been shown to influence neutrophil-mediated inflammation. One of the primary reasons behind this is our lack of understanding about neutrophils.15 16

Despite the fact that previous studies have shown an association between elevated neutrophils in airways with lower forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in obstructive airway disease,17 little is known about variations within the population of neutrophils in the airways. Recent studies have identified heterogeneity within circulating neutrophils. Pillay et al 18 identified three subsets of neutrophils (normal, banded and hypersegmented) in the circulation following an inflammatory challenge. Each subset had a distinct nuclear morphology and pattern of surface adhesion molecule expression, with hypersegmented neutrophils showing increased capacity for oxidative burst along with a unique ability to suppress T lymphocyte activation. The same morphologically distinct subsets have been identified in both bronchial lavage (BL) and blood from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)19 and in infants with severe viral respiratory infection.20

The presence and characteristics of neutrophil subsets in obstructive airway disease are unknown. In this exploratory study, we have characterised and estimated neutrophil subsets in BL fluid from adults with asthma, COPD, non-CF bronchiectasis and healthy controls. In addition we have explored the association of these subsets with the clinical characteristics of obstructive airway disease participants.

Materials and methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures of this study. The research question was developed by the authors (JLS and PABW). Patients were recruited if they were undergoing a bronchoscopy as explained in the Participants section. The results will be disseminated through publication and presentation at local, national and international research meetings.

Participants

Adults who were undergoing bronchoscopy either for medical purposes or were undergoing a surgical procedure that involved endotracheal intubation and had spirometry results were recruited for this study from the outpatient clinic of John Hunter Hospital.

Study design

A cross-sectional exploratory study was conducted in which BL samples were obtained after an assessment of clinical history including respiratory symptoms, smoking status and medication. Spirometry and bronchoscopy were performed as outlined below.

Study group

Adults (>18 years) with no history of a clinical chest or upper respiratory tract infection in the previous 6 weeks were studied. Healthy non-smokers (n=20) had normal lung function assessed by spirometry, and had no history of respiratory disease. Adults with asthma (n=39) had a physician’s diagnosis of asthma with objective evidence of airflow variability or bronchial hyperactivity on provocation challenge. Bronchiectasis (n=19) was defined as evidence of a permanent dilation of airway segment on high-resolution CT scan while those with COPD (n=20) had evidence of respiratory symptoms in combination with a postbronchodilator FEV1 of less than 80% of predicted value and/or a postbronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) less than 70%. Current smokers were excluded. Since this was an exploratory study in a completely new setting, the number of participants in each group was decided on the basis of previous exploratory studies in this area.18 19 21

Spirometry

Spirometry was performed (Easy One Spirometer, ndd Medical Technologies, Massachusetts, USA) at John Hunter Hospital. Variable obstruction defined as a postbronchodilator change in FEV1 of 12% or 200 mL after 400 mcg of salbutamol and the bronchial hyper-responsiveness defined as at least 15% decline in FEV1 after inducing bronchial provocation with 4.5% saline solution.

Bronchoscopy

Flexible bronchoscopy was performed at John Hunter Hospital, bronchial wash was taken by wedging the bronchoscope into the right middle lobe and washing with 40 mL of sterile saline solution. A fraction of BL was sent for microbial detection while the rest was processed as described below.

BL processing

BL was filtered and total cell count (TCC) and viability was assessed by using trypan blue exclusion method, within 1 hour of collection at Hunter Medical Research Institute. The BL was centrifuged and the cell pellet was resuspended in phosphate buffered saline to the concentration of 1×106/mL and cellular cytospins were prepared. The cytospins were stained with May-Grünwald Giemsa (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and a differential cell count of 400 non-squamous cells was performed.

Neutrophil subtype assessment

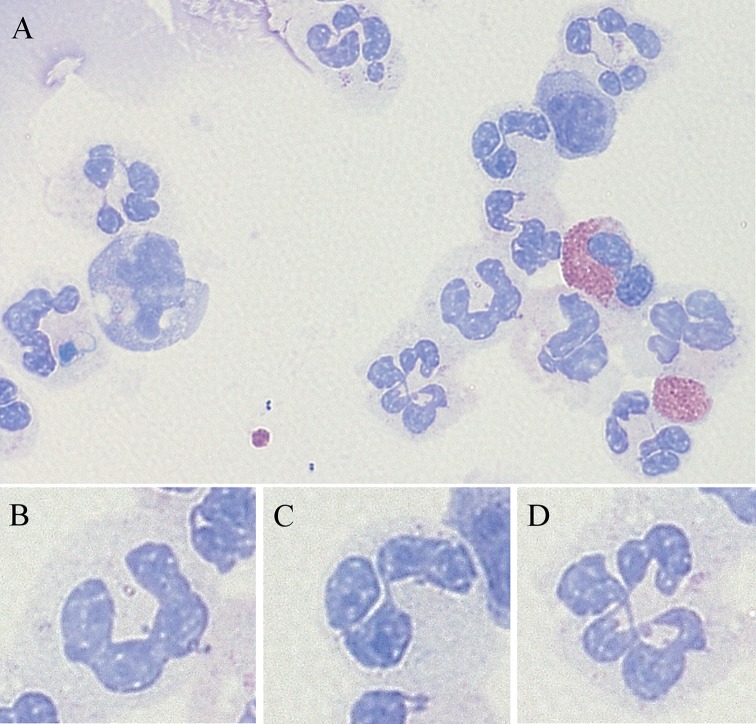

Stained cytospins were examined under oil immersion and 100 neutrophils were enumerated into banded, normal and hypersegmented neutrophils. Banded neutrophils had a single-banded lobe without any visible division; normal neutrophils had two to four lobes with every lobe having a properly visible outer boundary; and hypersegmented neutrophils had more than four lobes with every lobe having a properly visible outer boundary as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Subsets of neutrophils characterised as per number of lobes in their nucleus. (A) A representative pictomicrograph of bronchial lavage (BL) cytospin of obstructive airway disease participants (×100 original magnification, May-Grünwald Giemsa (MGG) stain) consists of (B) banded neutrophil, (C) normal neutrophil and (D) hypersegmented neutrophil.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Stata software V.11 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Results are reported as mean (SD) or median (IQR), unless otherwise stated. Continuous measures were analysed using the two-sample Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test or t-test and Kruskal-Wallis test or one-way analysis of variance as appropriate. Categorical data were analysed using Fisher’s exact test. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated for the association between neutrophil subsets and clinical characteristics.

Results

Clinical characteristics

Participants with COPD were more likely to be ex-smoking males with more severe airflow obstruction (table 1). Fewer participants with COPD were prescribed ICS compared with the asthma group, however, the mean daily dose of ICS was significantly higher in COPD participants. The number of participants with severe asthma was higher than the number with severe COPD (table 1) according to Global Initiative for Asthma22 and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease23 severity classification, respectively. Bronchiectasis participants were generally of mild severity according to their bronchiectasis severity index24 (table 1). The causes of bronchiectasis are mainly idiopathic and after infection (online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of participants with bronchiectasis, asthma, COPD and healthy controls

| Bronchiectasis | COPD | Asthma | Healthy | P value | |

| n | 19 | 20 | 39 | 20 | |

| Age | 67.8 (7.1) | 68.8 (10.2) | 64.8 (7.3) | 61.3 (9.7) | 0.024 |

| Males, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | 14 (70.0) | 18 (46.2) | 9 (45.0) | 0.184 |

| Ex-smoker, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 20 (100.0)*† | 15 (38.5)†‡ | 2 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (pack-years) | – | 35.0 (20.0–55.0) | 10.0 (4.0–30.0)‡ | (5.0, 5.0) | 0.007 |

| FEV1% predicted | 91.9 (18.3)‡ | 57.4 (16.9)* | 72.3 (20.1)*† | 98.6 (12.1), n=19 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 73.0 (67.0–78.0)‡ | 59.5 (39.0–65.0) | 66.0 (59.0–72.0)*‡ | 75.0 (72.0–80.0)‡, n=19 | <0.001 |

| Taking ICS, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (40.0) | 37 (94.9)‡ | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| BDP equivalent ICS dose (µg/day) |

– | 1700.00 (555.49) | 978.37 (398.70)‡ | – | <0.001 |

| Bacterial pathogen, n (%) | 8 (42.1)* | 8 (40.0)* | 12 (30.8)* | 0 (0) | 0.003 |

| Bronchiectasis severity index | 4 (2.0–7.0), n=18 | – | – | – | – |

| GINA stages of asthma severity, n (%) | |||||

| Intermittent | 1 (2.6) | ||||

| Mild persistent | 6 (15.8) | ||||

| Moderate persistent | 9 (23.7) | ||||

| Severe persistent | 22 (56.4) | ||||

| GOLD stages of COPD severity, n (%) | |||||

| GOLD stage 1 (mild) | 2 (10.0) | ||||

| GOLD stage 2 (moderate) | 11 (55.0) | ||||

| GOLD stage 3 (severe) | 6 (30.0) | ||||

| GOLD stage 4 (very severe) | 1 (5.0) |

Data are presented as mean±SD or median (IQR; Q1–Q3) unless otherwise stated.

BDP equivalent ICS dose is calculated as beclomethasone dipropionate equivalent, where 1 µg of beclomethasone=1 µg budesonide=0.5 µg fluticasone.

*P<0.0125 compared with healthy controls.

†P<0.0125 compared with bronchiectasis.

‡P<0.0125 compared with COPD.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, force expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid.

bmjopen-2018-024330supp001.pdf (35.3KB, pdf)

Inflammatory cell counts

BL inflammatory cell counts for the participants are detailed in table 2. Participants with bronchiectasis and COPD had an increased TCC (table 2). The proportion and number of neutrophils was significantly higher in the bronchiectasis and COPD group compared with healthy controls, while the proportion of neutrophils in asthma was significantly lower in comparison to COPD. The asthma group also had a significantly lower number of neutrophils in comparison to bronchiectasis and COPD. The proportion of eosinophils was significantly higher in COPD and asthma compared with healthy controls, while the number of eosinophils was significantly higher in all three obstructive airway diseases compared with healthy controls.

Table 2.

Inflammatory cell count of participants with bronchiectasis, asthma, COPD and healthy controls

| Bronchiectasis | COPD | Asthma | Healthy | P value* | |

| Total cells (×106/mL) | 0.62 (0.19–1.74)† | 0.83 (0.16–1.88)† | 0.16 (0.09–0.34)‡§ | 0.08 (0.05–0.21) | <0.001 |

| Viability (%) | 82.26 (75.00–91.67)† | 87.75 (73.60–92.95)† | 77.78 (62.30–88.00) | 72.22 (50.00–75.00) | 0.005 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 67.50 (41.00–84.25)† | 77.25 (73.00–85.13)† | 58.00 (24.50–72.50)‡ | 28.25 (14.75–63.50) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils (×104/mL) | 43.20 (5.21–164.43)† | 60.35 (13.31–149.70)† | 8.24 (3.12–25.01)§‡ | 3.18 (1.51–5.03) | <0.001 |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1.00 (0.50–6.50) | 3.75 (1.13–8.88)† | 2.25 (1.00–11.75)† | 1.00 (0.75–1.25) | 0.016 |

| Eosinophils (×104/mL) | 0.75 (0.40–2.76)† | 1.89 (1.03–4.03)† | 0.63 (0.14–3.07)† | 0.09 (0.05–0.23) | <0.001 |

| Macrophages (%) | 18.75 (11.00–34.75) | 15.50 (8.50–20.03)† | 25.00 (9.25–39.25) | 29.25 (17.00–63.12) | 0.025 |

| Macrophages (×104/mL) | 12.40 (5.94–24.42)† | 9.66 (2.91–18.24) | 4.24 (2.00–7.77)§ | 2.10 (1.42–6.43) | 0.002 |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 0.75 (0.00–1.50) | 0.38 (0.00–1.25) | 0.50 (0.00–1.50) | 1.5 (0.25–5.13) | 0.058 |

| Lymphocytes (×104 cells/mL) |

0.30 (0.00–1.02) | 0.18 (0.00–0.89) | 0.09 (0.00–0.37) | 0.18 (0.05–0.42) | 0.459 |

| Columnar epithelial cells (%) | 1.75 (0.75–10.50) | 0.25 (0.00–2.50)† | 4.50 (1.50–10.75)‡ | 9.50 (4.88–23.63) | <0.001 |

| Columnar epithelial cells (×104/mL) | 1.99 (0.48–2.67)‡ | 0.28 (0.00–0.59)† | 1.00 (0.35–1.98)‡ | 0.88 (0.38–2.38) | <0.001 |

Data are presented as median (IQR; Q1–Q3) unless otherwise stated.

*Kruskal-Wallis test.

†P<0.0125 compared with healthy controls.

‡P<0.0125 compared with COPD.

§P<0.0125 compared with bronchiectasis.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

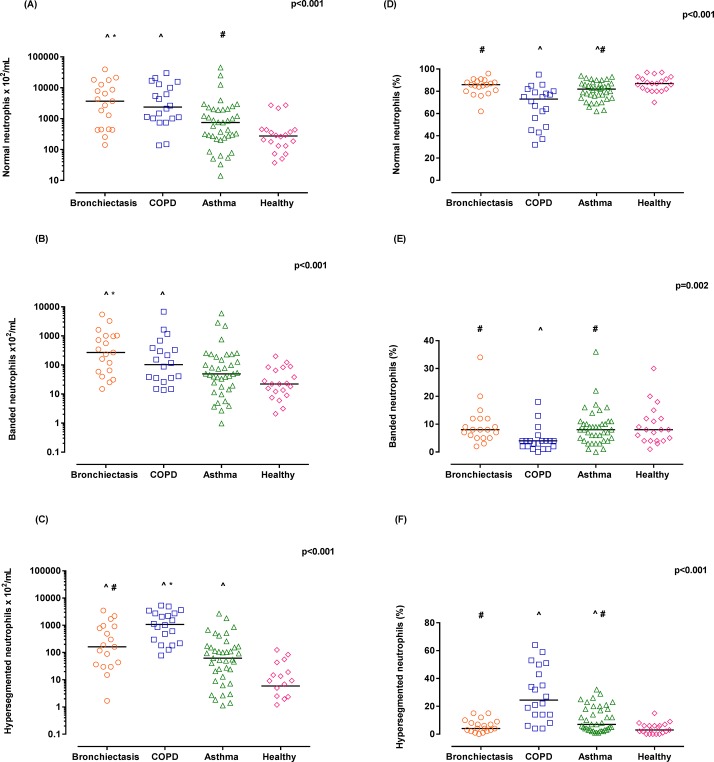

Neutrophil subsets

All three neutrophil subsets were identified in the BL of all participants. The numbers of normal neutrophils were significantly higher in bronchiectasis and COPD group in comparison to healthy and asthma (figure 2A). Numbers of banded neutrophils were highest in those participants with bronchiectasis compared with both healthy and asthma groups, while in COPD banded neutrophils numbers were higher in comparison to healthy participants only (figure 2B). Hypersegmented neutrophil numbers were significantly increased in all the obstructive airway disease groups compared with healthy controls and increased in participants with COPD compared with asthma and bronchiectasis (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Neutrophil subset number (A–C) and neutrophil subset proportion (D–F) in bronchial lavage (BL) of participants with bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma and healthy controls. The line in dot plots of each group represents the median. ^P<0.0125 compared with healthy controls; *P<0.0125 compared with asthma; and #P<0.0125 compared with COPD, as per Kruskal-Wallis test.

When considering the relative distribution of neutrophil subsets by proportion (shown in figure 2D–F), participants with COPD had a significantly reduced proportion of normal and banded neutrophils and subsequently a significantly increased proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils.

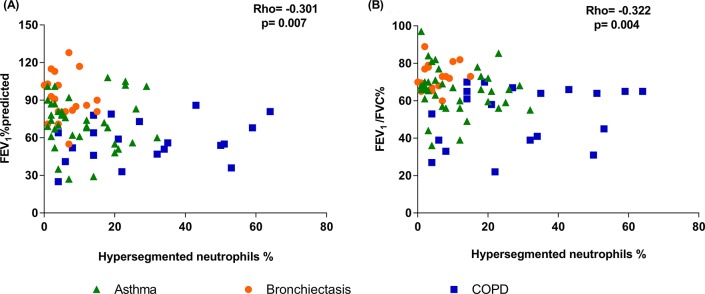

Association of neutrophil subsets with clinical characteristics in obstructive airway disease

There was a significant negative correlation between the proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils with both FEV1% predicted (Spearman’s r=−0.301, p=0.007) and FEV1/FVC% (r=−0.322, p=0.004, figure 3) in participants with obstructive airway disease (n=78). While the same was not observed for banded neutrophils (FEV1% predicted (r=0.181, p=0.114), FEV1/FVC% (r=0.213, p=0.061)) and normal neutrophils (FEV1% predicted (r=0.189, p=0.097), FEV1/FVC% (r=0.213, p=0.062)). There was no association between the total number of hypersegmented neutrophils (×102 cells/mL) with both FEV1% predicted (r=−0.152, p=0.185) and FEV1/FVC% (r=−0.173, p=0.131). Similarly, no association was observed between total neutrophil proportion and number with either FEV1% predicted (r=−0.143, p=0.212 and r=−0.036, p=0.758, respectively) or with FEV1/FVC% (r=−0.142, p=0.214 and r=−0.043, p=0.707, respectively).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of hypersegmented neutrophil proportion versus FEV1% predicted (A) and FEV1/FVC (B) in bronchial lavage (BL) of obstructive airway disease participants. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity.

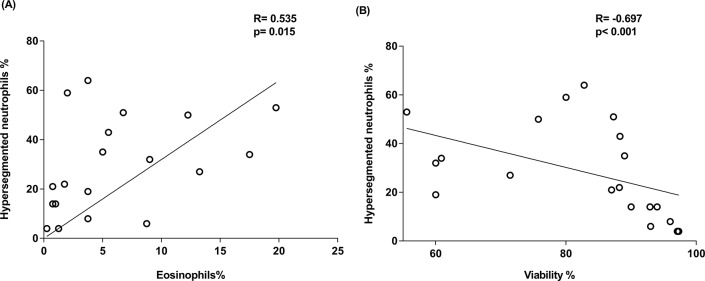

In participants with COPD, the proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils was positively associated with proportion of eosinophils (r=0.535, p=0.015) (figure 4A) and negatively associated with cell viability (r=−0.697, p<0.001) (figure 4B). This association was not observed in any other clinical group or in the overall population (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(A) Scatterplot of hypersegmented neutrophil proportion versus eosinophil proportion, (B) viability of total cells in bronchial lavage (BL) of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) participants.

To explore the correlation between the proportions of eosinophils and hypersegmented neutrophils further, we decided to examine the COPD participants according to their inflammatory subtype categorised as eosinophilic COPD (E-COPD) (≥3% eosinophils) and non-eosinophilic COPD (NE-COPD) (<3% eosinophils).

E-COPD and NE-COPD

Twelve participants were characterised as E-COPD and eight participants were characterised as NE-COPD. The NE-COPD group had a significantly elevated TCC (NE-COPD, 1.71 (1.47) ×106/mL; E-COPD, 0.67 (0.55) ×106/mL, p=0.037) and cell viability (NE-COPD, 90.82 (5.80)%; E-COPD, 76.67 (14.64)%, p=0.019) along with a significantly elevated neutrophil proportion (NE-COPD, 85.50 (77.00–92.38)%; E-COPD, 75.75 (69.88–77.75)%, p=0.037) and neutrophil number (NE-COPD, 148.37 (132.16) ×104/mL; E-COPD, 50.93 (42.95) ×104/mL, p=0.028) in comparison to E-COPD. The number and proportion of eosinophils were significantly higher in E-COPD, that is, (NE-COPD, 1.14 (1.05) ×104/mL; E-COPD, 4.71 (4.09) ×104/mL, p=0.040) and (NE-COPD, 1.09 (0.57)%; E-COPD, 9.08 (5.50)%, p<0.001), respectively. Besides this, no significant differences were observed between these groups for any other clinical parameters.

Neutrophil subsets in E-COPD and NE-COPD

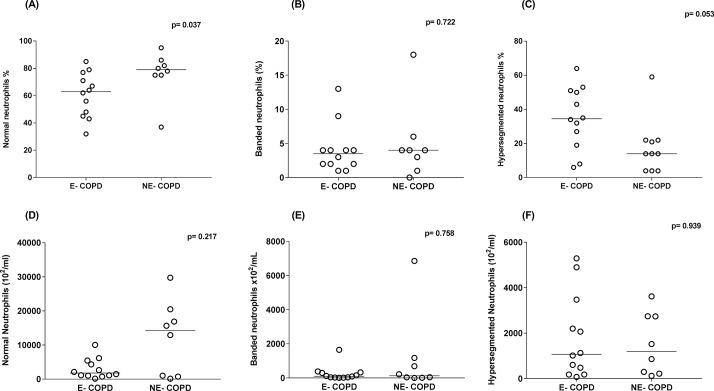

The proportion of normal neutrophils was significantly reduced while the proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils was elevated (figure 5A,C respectively) in E-COPD compared with NE-COPD. While no significant differences were observed for the number of any individual subset (figure 5D–F) between E-COPD and NE-COPD.

Figure 5.

Neutrophil subsets proportion (A–C) and neutrophil subsets number (D–F) in bronchial lavage of eosinophilic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (E-COPD) and non-eosinophilic COPD (NE-COPD) participants. The line in dot plots of each group represents the median and the p value in each graph is an outcome of Wilcoxon rank-sum test.

Discussion

The study identified three morphologically distinct subsets of neutrophils, that is, banded, normal and hypersegmented, in the BL of participants with chronic obstructive airway disease and healthy controls. There were a significantly higher number of hypersegmented neutrophils in those with obstructive airway disease compared with healthy controls. The proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils was associated with lower FEV1 and more severe airflow obstruction (FEV1/FVC%) in obstructive airway disease participants and with the presence of eosinophilic airway inflammation in COPD.

The concept of morphological heterogeneity in neutrophil population has recently emerged.25 We have examined neutrophil heterogeneity in the BL of obstructive airway disease participants and healthy controls. The reason for neutrophil heterogeneity is unclear but may be attributable to the different stages of cell maturation in the bone marrow before transition to the tissue, or alternatively, neutrophils might change their morphology during the course of inflammation to adjust with the stressors in inflamed airways.5 26

Banded neutrophils are also known as immature neutrophils and are deemed incompetent in antimicrobial immune functions as reported in the systemic circulation of patients with sepsis.27 The emergence of banded neutrophils in the airway can occur after depletion of mature neutrophils in bone marrow following excessive demand during acute inflammation.20

The presence of hypersegmented neutrophils in airways could be an attribute of inflammation as the hypersegmented neutrophils have also been reported in other inflammatory conditions such as trauma18 and in chronic inflammatory lung diseases such as ARDS.19

The hypersegmented morphology of the neutrophil implies increased maturation compared with banded and normal neutrophils.18 Maturation is thought to occur in inflamed airways due to the presence of a cytokine-rich environment consisting of prosurvival mediators.28 The mechanism behind formation of hypersegmented neutrophils is known to be linked with the life cycle of the neutrophils. The increase in survival causes the nucleus of neutrophil to develop more indentation and segmentation, and hence the hypersegmented neutrophils are also called ‘old neutrophils’.29

The ability of a chemoattractant-rich milieu to change the phenotype of neutrophils was recently shown when neutrophils from the blood of healthy volunteers were incubated with the broncoalveolar lavage from a patient with ARDS. These neutrophils altered their phenotype, with an increase in those with a hypersegmented morphology.19 It may be possible that a similar process is occurring chronically in the airways of obstructive airway disease participants, who generally have higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators. Previous studies have demonstrated that hypersegmented neutrophils in the circulation demonstrate low expression of L-selectins, which may reduce their anchoring ability on endothelial cells and hence reduce their chances to egress into inflamed airways.30 Thus, it is possible that the hypersegmented neutrophils we observed in our study have not directly come from circulation and instead may have become hypersegmented in the airways under the influence of prosurvival mediators.

Mediators that promote neutrophil survival and can be present in the airways include: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), chemokines like CXCL-8 and lipid mediators such as serum amyloid A.2 26 GM-CSF and CXCL-8 are known to enhance neutrophil survival by promoting the expression of antiapoptotic proteins like survivins and by preventing TNF-α mediated apoptosis.31 32 While serum amyloid A is known to prolong neutrophil longevity by preventing mitochondrial damage and decreasing caspase-3 (apoptotic protein) activity.33 Our past studies have reported elevated levels of CXCL-8 in sputum samples of patients with neutrophilic asthma, bronchiectasis34 and COPD.35 Besides this, we have also reported that elevated levels of serum amyloid A in COPD were associated with neutrophilic inflammation in airways and this was refractory to corticosteroids.36 This suggests that the elevated presence of these markers might have played some role in enhancing the survival of neutrophils in airways and promoting the presence of hypersegmented neutrophils.

In this study, we also reported a positive correlation between eosinophils and hypersegmented neutrophil proportion in COPD participants along with elevated proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils in E-COPD participants. The presence of eosinophils in airways can further elevate the level of GM-CSF due to their own production of this cytokine,37 which can further promote maturation of neutrophils. Besides this, the use of ICS to control eosinophilic inflammation may enhance neutrophil survival in the inflamed airways by increasing the activity of antiapoptotic proteins such as Mcl-1 (induced myeloid leukaemia cell differentiation protein) and inhibitor of apoptosis proteins in neutrophils.38 This increased maturity and prevention of death may result in an increased proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils.

There is also a debate about whether all hypersegmented neutrophils have same functional characteristics. Pillay et al 18 observed that hypersegmented neutrophils obtained after inducing acute systemic inflammation were exhibiting immunosuppressive effect on T lymphocyte in an in vitro coculture. In another study, Whitmore et al 39 observed that neutrophils changed into a hypersegmented phenotype following incubation with Helicobacter pylori, which could then exhibit cytotoxic activity on stomach epithelial cells. But interestingly in both these studies, hypersegmented neutrophils exhibited their respective response by same mechanism, that is, by administering high amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in respective cells, and also had a similar pattern of adhesion molecule expression on their surface.

The significant association between the proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils with FEV1 and severe airflow obstruction in our study suggests that where hypersegmented neutrophils are common, airway obstruction is most severe. This could be a result of high oxidative burst produced by hypersegmented neutrophils as observed in previous studies, in which hypersegmented neutrophil exhibited high oxidative burst after ex vivo stimulation.18 19 The generation of high oxidative burst by neutrophils may also impair their timely clearance from the airway40 and can trigger a vicious cycle of neutrophil influx into the airways.6 The impairment of neutrophil clearance in airway may cause necrosis of neutrophils which can spill its cytotoxic content such as ROS and proteolytic enzymes like neutrophil elastase in the lumen of airways.41 This can further damage airway wall and promote mucus hypersecretion which may result in significant decline in FEV1 as earlier reported in COPD.42 Interestingly, we did not observe this correlation with other neutrophil subsets or with total neutrophil proportion or number. Further research is needed to understand if hypersegmented neutrophils are common as a result of more severe disease or conversely if they influence disease severity.

The cross-sectional nature of study is a limitation in properly establishing the cause and effect of relationship of neutrophil heterogeneity in airways. Besides that, the small sample size is another limitation of this study. Hence, further confirmatory studies are needed with large sample sizes to validate the finding of this study. Additionally, a detailed ex vivo study of influence of pathogen, prosurvival mediators and current medications like ICS on neutrophil subset morphology, surface expressions and functional behaviour is also needed to provide a better understanding of the formation of hypersegmented neutrophils in the airways and subsequently in developing a more comprehensive strategy for assessment and management of airway neutrophilia.

Conclusion

We have shown the presence of three morphologically different subsets of neutrophils in the airways of healthy and obstructive airway disease participants, that is, asthma, COPD and bronchiectasis. The increased proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils in the airways of obstructive airway disease participants was associated with reduced lung function of these participants. The proportion of hypersegmented neutrophils was highest in COPD participants in comparison to all other groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical support from Andrew Reid, Michelle Gleeson, Kellie Fakes and Bridgette Donati, and the clinical support from Lorissa Hopkins and Douglas Dorahy of the Priority Research Centre for Healthy Lungs.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: JLS developed the idea and designed the study. JLS also supervised and coordinated the study throughout. RL performed the subtype counting and wrote the manuscript which was further refined and edited by JLS, PABW, KJB and DB. PABW performed the bronchoscopy, KJB supervised the bronchial lavage processing and cytospin preparation and DB supervised the statistical analysis.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Hunter New England Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference No 05/08/10/3.09).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Raw data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Wright HL, Moots RJ, Bucknall RC, et al. Neutrophil function in inflammation and inflammatory diseases. Rheumatology 2010;49:1618–31. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, et al. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol 2012;30:459–89. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zuo L, Lucas K, Fortuna CA, et al. Molecular regulation of toll-like receptors in asthma and COPD. Front Physiol 2015;6:312 10.3389/fphys.2015.00312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Konrad FM, Reutershan J. CXCR2 in acute lung injury. Mediators Inflamm 2012;2012:1–8. 10.1155/2012/740987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bruijnzeel PL, Uddin M, Koenderman L. Targeting neutrophilic inflammation in severe neutrophilic asthma: can we target the disease-relevant neutrophil phenotype? J Leukoc Biol 2015;98:549–56. 10.1189/jlb.3VMR1214-600RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Simpson JL, Phipps S, Gibson PG. Inflammatory mechanisms and treatment of obstructive airway diseases with neutrophilic bronchitis. Pharmacol Ther 2009;124:86–95. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Essilfie AT, Simpson JL, Dunkley ML, et al. Combined Haemophilus influenzae respiratory infection and allergic airways disease drives chronic infection and features of neutrophilic asthma. Thorax 2012;67:588–99. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kirsty H, Rahul S, Richard R, et al. Defining inflammatory groups within a COPD cohort B43 COPD: phenotypes and clinical outcomes. American Thoracic Society 2016:A3514–A14. [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonald VM, Higgins I, Wood LG, et al. Multidimensional assessment and tailored interventions for COPD: respiratory utopia or common sense? Thorax 2013;68:691–4. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dente FL, Bilotta M, Bartoli ML, et al. Neutrophilic bronchial inflammation correlates with clinical and functional findings in patients with noncystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Mediators Inflamm 2015;2015:1–6. 10.1155/2015/642503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reddel HK, Bateman ED, Becker A, et al. A summary of the new GINA strategy: a roadmap to asthma control. Eur Respir J 2015;46:622–39. 10.1183/13993003.00853-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bathoorn E, Kerstjens H, Postma D, et al. Airways inflammation and treatment during acute exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008;3:217–29. 10.2147/COPD.S1210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang AB, Bell SC, Byrnes CA, et al. Chronic suppurative lung disease and bronchiectasis in children and adults in Australia and New Zealand. Med J Aust 2010;193:356–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Simpson JL, Scott R, Boyle MJ, et al. Inflammatory subtypes in asthma: assessment and identification using induced sputum. Respirology 2006;11:54–61. 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Beeh KM, Beier J. Handle with care: targeting neutrophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe asthma? Clin Exp Allergy 2006;36:142–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2006.02418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mårdh CK, Root J, Uddin M, et al. Targets of neutrophil influx and weaponry: therapeutic opportunities for chronic obstructive airway disease. J Immunol Res 2017;2017:1–13. 10.1155/2017/5273201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shaw DE, Berry MA, Hargadon B, et al. Association between neutrophilic airway inflammation and airflow limitation in adults with asthma. Chest 2007;132:1871–5. 10.1378/chest.07-1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pillay J, Kamp VM, van Hoffen E, et al. A subset of neutrophils in human systemic inflammation inhibits T cell responses through Mac-1. J Clin Invest 2012;122:327–36. 10.1172/JCI57990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Juss JK, House D, Amour A, et al. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Neutrophils Have a Distinct Phenotype and Are Resistant to Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Inhibition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194:961–73. 10.1164/rccm.201509-1818OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cortjens B, Ingelse SA, Calis JC, et al. Neutrophil subset responses in infants with severe viral respiratory infection. Clin Immunol 2017;176:100–6. 10.1016/j.clim.2016.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tak T, Wijten P, Heeres M, et al. Human CD62Ldim neutrophils identified as a separate subset by proteome profiling and in vivo pulse-chase labeling. Blood 2017;129:3476–85. 10.1182/blood-2016-07-727669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koshak EA. Classification of asthma according to revised 2006 GINA: evolution from severity to control. Ann Thorac Med 2007;2:45–6. 10.4103/1817-1737.32228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yusen RD. Evolution of the GOLD documents for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Controversies and questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:4–5. 10.1164/rccm.201305-0846ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Aliberti S, et al. The bronchiectasis severity index. An international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:576–85. 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Silvestre-Roig C, Hidalgo A, Soehnlein O. Neutrophil heterogeneity: implications for homeostasis and pathogenesis. Blood 2016;127:2173–81. 10.1182/blood-2016-01-688887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2013;13:159–75. 10.1038/nri3399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Taneja R, Sharma AP, Hallett MB, et al. Immature circulating neutrophils in sepsis have impaired phagocytosis and calcium signaling. Shock 2008;30:618–22. 10.1097/SHK.0b013e318173ef9c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Uddin M, Nong G, Ward J, et al. Prosurvival activity for airway neutrophils in severe asthma. Thorax 2010;65:684–9. 10.1136/thx.2009.120741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pillay J, Tak T, Kamp VM, et al. Immune suppression by neutrophils and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells: similarities and differences. Cell Mol Life Sci 2013;70:3813–27. 10.1007/s00018-013-1286-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kamp VM, Pillay J, Lammers JW, et al. Human suppressive neutrophils CD16bright/CD62Ldim exhibit decreased adhesion. J Leukoc Biol 2012;92:1011–20. 10.1189/jlb.0612273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gabelloni ML, Trevani AS, Sabatté J, et al. Mechanisms regulating neutrophil survival and cell death. Semin Immunopathol 2013;35:423–37. 10.1007/s00281-013-0364-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kettritz R, Gaido ML, Haller H, et al. Interleukin-8 delays spontaneous and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-mediated apoptosis of human neutrophils. Kidney Int 1998;53:84–91. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kebir DE, Jozsef L, Khreiss T, et al. Serum amyloid A (SAA) prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and delays constitutive neutrophil apoptosis. The FASEB Journal 2007;21:A13. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simpson JL, Grissell TV, Douwes J, et al. Innate immune activation in neutrophilic asthma and bronchiectasis. Thorax 2007;62:211–8. 10.1136/thx.2006.061358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Baines KJ, Simpson JL, Gibson PG. Innate immune responses are increased in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. PLoS One 2011;6:e18426 10.1371/journal.pone.0018426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bozinovski S, Uddin M, Vlahos R, et al. Serum amyloid A opposes lipoxin A₄ to mediate glucocorticoid refractory lung inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012;109:935–40. 10.1073/pnas.1109382109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Esnault S, Malter JS. GM-CSF regulation in eosinophils. Arch Immunol Ther Exp 2002;50:121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Saffar AS, Ashdown H, Gounni AS. The molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoids-mediated neutrophil survival. Curr Drug Targets 2011;12:556–62. 10.2174/138945011794751555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Whitmore LC, Weems MN, Allen LH. Cutting Edge: Helicobacter pylori Induces Nuclear Hypersegmentation and Subtype Differentiation of Human Neutrophils In Vitro. J Immunol 2017;198:1793–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.1601292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Simpson JL, Gibson PG, Yang IA, et al. Impaired macrophage phagocytosis in non-eosinophilic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43:29–35. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04075.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim S, Nadel JA. Role of neutrophils in mucus hypersecretion in COPD and implications for therapy. Treat Respir Med 2004;3:147–59. 10.2165/00151829-200403030-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Vestbo J, Prescott E, Lange P. Association of chronic mucus hypersecretion with FEV1 decline and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease morbidity. Copenhagen City Heart Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;153:1530–5. 10.1164/ajrccm.153.5.8630597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024330supp001.pdf (35.3KB, pdf)