Abstract

Introduction

Costs associated with the delivery of healthcare services are growing at an unsustainable rate. There is a need for health systems and healthcare providers to consider the economic impacts of the service models they deliver and to determine if alternative models may lead to improved efficiencies without compromising quality of care. The aim of this protocol is to describe a scoping review of the extent, range and nature of available synthesised research on alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published in the last 5 years.

Design

We will perform a scoping review of systematic reviews of trials and economic studies of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published on ‘Pretty Darn Quick’ (PDQ)-Evidence between 1 January 2012 and 20 September 2017. All English language systematic reviews will be included. The Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care taxonomy of health system interventions will be used to categorise delivery arrangements according to: how and when care is delivered, where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment, who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed, co-ordination of care and management of care processes and information and communication technology systems. This work is part of a 5-year Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability aiming to investigate and create interventions to improve health-system-performance sustainability.

Ethics and dissemination

No primary data will be collected, so ethical approval is not required. The study findings will be published and presented at relevant conferences.

Keywords: healthcare delivery, sustainability, alternative healthcare models, delivery arrangement, high-income, scoping review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A high-level synthesis of the available evidence for alternative models of health service delivery is much needed and will be a useful resource for decision makers involved in health system planning, health system performance, sustainability initiatives and future research directions.

We have followed published methodological guidance in planning our methods for conducting this scoping review, and we will additionally perform independent double data extraction to enhance the robustness of our findings where consistency of extraction is <90%.

The search date will be limited to the last 5 years to retrieve useful, up-to-date reviews of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries.

Limiting the search date to the last 5 years means it is possible that we may not capture delivery arrangements included in out-of-date systematic reviews (published prior to 2012).

Systematic reviews that are awaiting classification in ‘Pretty Darn Quick’-Evidence will not be assessed as part of this review.

Background

The provision of sustainable, appropriate healthcare is an ongoing challenge for health systems worldwide. There are many drivers of increasing healthcare costs. They include growing pressure from an ageing population,1 2 growth in the prevalence of chronic and preventable diseases, increasing availability of (more expensive) clinical tests and treatments,3 medicalisation of risk factors and active screening of people who are well,4 5 lowering of diagnostic and intervention thresholds for high prevalence conditions6–8 and changing community expectations.9 10 In addition, high-income countries are experiencing increasing inflationary pressures and workforce shortages.11–15 In order to be sustainable, health systems and providers must be able to endure and adapt to these growing pressures by delivering services that maintain a high quality of care while providing better value for money.16 In practice, this means health systems and providers need to consider the effectiveness and economic impact of existing service models, and also determine if there are alternative models that might lead to improved efficiencies without compromising the quality of care and patient outcomes.

There are examples of models of service delivery that have been adopted in practice that offer modest benefits for patients when compared with usual care, but where the economic impact is uncertain (eg, early discharge from hospital and care at home),17 or not known (eg, mid-wife led models of care).18 In addition, some alternative delivery arrangements have been implemented despite uncertainty about effects on patient care and economic impact (eg, primary care physicians providing care in emergency departments)19 and, in some cases, effectiveness is later shown to be low and associated costs, high (eg, rapid exchange of operating room air to reduce infection rates).20 For this reason, efforts that aim to manage expenditure need to focus not just on benefits to patients, but on the value of the delivery arrangement relative to the cost. This distinction is important, as high-cost models of care may still be good value if they deliver high levels of benefit to patients, while low-cost models of care may have no value if they provide little or no benefit.21 In 2017, the Australian Productivity Commission released a report identifying that there are considerable efficiencies to be gained through identifying enablers and barriers to more efficient models of care, and that eliminating financial reward for delivery of services where there is clear evidence of a lack of efficacy or cost effectiveness, or where the benefits do not justify the associated costs should be part of future health planning.22

Alternative models of service delivery offer an opportunity for healthcare providers to deliver healthcare services in different and potentially more cost-effective ways through lower cost- providers, locations and formats of delivery. Examples include changing the site of the service delivery from a more expensive to a less expensive option, providing care in a group setting rather than to individuals, substituting the care that is provided by a highly trained or specialised health worker to care provided by a less specialised or lay health worker, or using technology to deliver care (eg, telemedicine). Provision of services in this way may lead to the same, and in some cases better, outcomes for patients without compromising the quality of care. However, these alternative models may also increase costs, so they must undergo robust economic evaluations that not only take into account improvements in patient and carer outcomes, but also consider the benefit and costs to the health system as a whole.

A scoping review provides a rapid method of mapping key concepts within a research area and provides an overview of the main sources and types of evidence available.23 It is most useful when the research question is complex or has not been reviewed comprehensively before. A number of reviews of alternative delivery models have been published in the past 5 years. Most reviews have focused on the delivery of a single test or treatment for a particular disease or condition,24 25 or a single delivery arrangement-type such as chronic disease programmes,26 multidisciplinary care or integrated care interventions.27 As such, these reviews do not adequately summarise the volume and scope of existing synthesised research on alternative delivery arrangements. A recent Cochrane overview has focused on delivery arrangements relevant to low-income countries.28 However, low-income countries struggle with different health system demands, including a predominance of communicable diseases and resource constraints and limited access to new technologies and other resources. Therefore, the findings of this overview may be less applicable to high-income countries (for eg, it includes delivery arrangements for HIV/AIDS, malaria, childhood diarrhoea, pneumonia and vaccination and antenatal care).

To the best of our knowledge, no scoping review or overview of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries has been conducted to date. This work is likely to be useful for decision makers by mapping the availability of existing synthesised evidence, including where economic analysis of alternative delivery arrangements exists and in highlighting gaps for future research. The proposed scoping review forms part of 5-year Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and other partners and aims to investigate and create interventions to improve health system performance sustainability.29 This scoping review complements a systematic review by the Partnership Centre, currently under way, that will review the sustainability of interventions, improvement efforts and change strategies in the health system through an examination of trial data published in the last 5 years.16

Objectives

This scoping review aims to describe the extent, range and nature of available systematic reviews of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published in the last 5 years. A time-frame of 5 years was chosen to ensure that the review contained evidence and data about effects that are up-to-date, reliable and ready to implement. A secondary aim is to identify gaps in the availability of up-to-date systematic reviews of alternative delivery arrangements needed to inform health system sustainability initiatives and future research directions.

Methods and analysis

Protocol development

The protocol for this scoping review is underpinned by the methodological framework first suggested by Arksey and O’Malley,30 and further described by Levac and colleagues.31 This framework emphasises transparency of the protocol development and scoping review process to increase the reliability of the findings.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

We will include all English language systematic reviews examining the effects of alternative delivery arrangements for health systems relevant to high-income countries published between 1 January 2012 and 20 September 2017. Alternative delivery arrangements include changes to how and when care is delivered, where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment, who provides care and how the workforce is managed, co-ordination of care and management of care processes and information and communication technology systems.

For inclusion, systematic reviews must assess the effects of alternative delivery arrangements of relevance to high-income countries (as classified by the World Bank for the 2017 fiscal year),32 have a methods section with explicit inclusion criteria, and report at least one of the following outcomes: patient outcomes (health and health behaviours), quality of care, access and/or utilisation of healthcare services, resource use, impacts on equity and/or social outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes and adverse effects. We will consider for inclusion systematic reviews in any setting, including hospital (inpatient or outpatient care, acute or subacute), primary care, long-term care facilities and the community.

Search methods for identifying studies

We will search the ‘Pretty Darn Quick’ (PDQ)-Evidence for systematic reviews published between 1 January 2012 and 20 September 2017. PDQ-Evidence is a database of evidence for decisions about health systems derived from the Epistomonikos database of systematic reviews. It includes the following databases: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, MEDLINE via PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, Joanna Briggs Institute Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports, Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre Evidence Library and the Campbell Collaboration online library. The ‘intervention’ publication filter will be used to exclude systematic reviews of non-intervention studies. An example of the search method has been provided as an online supplementary file.

bmjopen-2018-024385supp001.pdf (556.5KB, pdf)

Study selection

Two review authors will independently screen the titles and abstracts retrieved by the search for inclusion and code as ‘retrieve’ (potentially eligible or unclear) or ‘do not retrieve’ (ineligible). We will retrieve the full text reports of potentially eligible and unclear titles and abstracts. Two (of a team of four) review authors will independently screen the full text reports and identify systematic reviews for inclusion and exclusion. We will record the reasons for exclusion of ineligible systematic reviews. We will resolve disagreements regarding eligibility through discussion, and if consensus is not achieved, by involving a third review author. We will prepare a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart summarising the search and selection process and the number of articles reviewed at each stage.

Data extraction and management

We will extract descriptive data on systematic review characteristics (year, authors, journal, number and design of included studies), delivery arrangement category and subcategory, target population, setting and target health issue/s. Outcome categories and the main effects searched for by systematic review authors will also be collected (patient outcomes, quality of care, access and/or utilisation of healthcare services, resource use, impacts on equity and/or social outcomes, healthcare provider outcomes, adverse effects and economic analysis, where reported). The research team will develop, pilot and refine a data extraction form31 (preliminary version of the data extraction form is presented in table 1).

Table 1.

Preliminary version of the data extraction form

| Study ID |

Author, year | Brief description of intervention /objective |

Place published | EPOC Delivery arrangement strategy | Sub- category |

Number and type of trials included | Target population | Setting | Target health issue/s | Patient outcomes (health and health behaviours for example, mortality, cure rates) | Quality of care (systems or processes for improving quality of care for example, timeout before surgery) | Resource use | Impacts on equity | Social outcomes (eg, poverty, unemployment) | Access, utilisation (eg, re- admission rates, length of stay) |

Healthcare provider outcomes (eg, overall well-being, fatigue, stress, satisfaction) | Adverse effects | Economic analyses |

| ID1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ID2 | ||||||||||||||||||

| ID3 |

EPOC, Effective Practice and Organisation of Care.

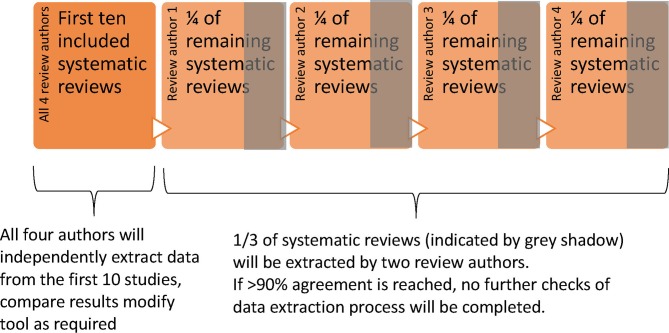

As we anticipate a large volume of included studies, four review authors will be involved in the data extraction process. Initially, all four will independently extract data and populate the data extraction form for 10 systematic reviews and discrepancies will be discussed to ensure the process for extraction is consistent. The remaining systematic reviews will then be divided between reviewers. While independent data extraction of included studies by two review authors is not routinely recommended in method guidance for scoping reviews,31 we will have a second reviewer allocated to extract a random sample of one third of included systematic reviews to assess the level of consistency and determine the accuracy of our process. Any disagreement between reviewer extraction processes will be resolved through discussion until consensus is reached. If the mean agreement in data extraction across this subset of systematic reviews is >90%, no further checks will be conducted. The data extraction process is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data extraction process for included systematic reviews. All four authors will extract data from the first 10 systematic reviews. The remaining systematic reviews will be divided between the four review authors, and each author will have 1/3 of his/her studies reviewed by a second author to assess the level of agreement. If >90% agreement is reached, no further checks of data extraction process will be completed.

Collating and summarising results

We will categorise the delivery arrangements according to the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health system interventions.33 This taxonomy is useful for organising and characterising health system interventions according to conceptual, functional and/or practical similarities. The delivery arrangement domain of the taxonomy classifies interventions based on changes to the following:

How and when care is delivered.

Where care is provided and changes to the healthcare environment.

Who provides care and how the healthcare workforce is managed.

Co-ordination of care and management of care processes and

Information and communication technology systems.

In addition, we will use a category titled ‘multiple (goal-focused)’ to categorise systematic reviews that include all relevant delivery arrangements from across the above categories to address a specific problem or goal (eg, interventions for enhancing medication adherence).

We will summarise our findings quantitatively by presenting a numerical count of reviews in each category and visually using bubble charts to represent the quantity and range of systematic reviews across the delivery arrangement categories and to highlight gaps in the available synthesised evidence. Bubble charts allow the reader to see an overview of the spread of data across and within EPOC categories.34 We will also describe the extent, range and nature of available systematic reviews using a narrative synthesis. This process will allow for identification of gaps in the availability of up-to-date systematic reviews and areas of delivery arrangements where the evidence is limited. Specifically, results will be used to (1) quantify the extent, range and nature of delivery strategies reported in systematic reviews, (2) quantify the number of systematic reviews where an economic analysis of the arrangement was reported and (3) determine the gaps and suggest delivery arrangements where future systematic reviews might be of use.

Patient and public involvement

The Consumers Health Forum of Australia, a representative advocate body for consumers in healthcare, have had oversight in the development and design of the protocol for this scoping review. Specifically, two members of the forum participated in stakeholder workshops during the design of the scoping review. The results will be disseminated among all stakeholders of the Partnership Grant, including consumer representatives.

Conclusion

This scoping review will describe the volume and scope of available up-to-date systematic reviews of alternative delivery arrangements relevant to high-income countries, and identify gaps in the synthesised evidence, needed to inform health system planning, health system sustainability initiatives and future research directions.

Ethics and dissemination

As no primary data will be collected, ethical approval is not required. The study findings will be disseminated via reports, manuscript in a peer-reviewed journal and via conference presentations.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

RLJ and DAO’C contributed equally.

Contributors: The study conception and overall design was conceived by RB and DAO. RLJ, DAO and PP designed the data extraction tool and RLJ, PP, KR and JN all assisted in piloting. RLJ wrote the first draft of this protocol and RB, DAO, PP, KR, JN, SC and SS critically reviewed the manuscript, contributed improvements and approved the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by an NHMRC Partnership Centre for Health System Sustainability (Grant ID: 9100002). Along with the NHMRC, the funding partners in this research collaboration are: BUPA Health Foundation; NSW Health; Department of Health, Western Australia; and The University of Notre Dame Australia. RB is funded by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (#APP1082138).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Walker A. National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra. Australia’s ageing population. Canberra: National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling, University of Canberra, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Healey J. Ageing. Thirroul: Spinney Press, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pathirana T, Clark J, Moynihan R. Mapping the drivers of overdiagnosis to potential solutions. BMJ 2017;358:j3879 10.1136/bmj.j3879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moynihan R, Heath I, Henry D. Selling sickness: the pharmaceutical industry and disease mongering * Commentary: Medicalisation of risk factors. BMJ 2002;324:886–91. 10.1136/bmj.324.7342.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Glasziou P, Moynihan R, Richards T, et al. . Too much medicine; too little care. BMJ 2013;347:f4247 10.1136/bmj.f4247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen TW, Kikuya M, Thijs L, et al. . Diagnostic thresholds for ambulatory blood pressure moving lower: a review based on a meta-analysis-clinical implications. J Clin Hypertens 2008;10:377–81. 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07681.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mills NL, Lee KK, McAllister DA, et al. . Implications of lowering threshold of plasma troponin concentration in diagnosis of myocardial infarction: cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e1533 10.1136/bmj.e1533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Forouhi NG, Balkau B, Borch-Johnsen K, et al. . The threshold for diagnosing impaired fasting glucose: a position statement by the European Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Diabetologia 2006;49:822–7. 10.1007/s00125-006-0189-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hill S, Wiley I. The knowledgeable patient: communication and participation in health. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Health participation: achieving greater public participation and accountability in the Australian health care system. Melbourne: National Health Strategy, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordon B. Solving the workforce shortage. Health Progress 2003;84:59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Del Mar C. New investments in primary care in Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:39 10.1186/1472-6963-11-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brooks PM, Robinson L, Ellis N. Options for expanding the health workforce. Aust Health Rev 2008;32:156–60. 10.1071/AH080156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buchan JM, Naccarella L, Brooks PM. Is health workforce sustainability in Australia and New Zealand a realistic policy goal? Aust Health Rev 2011;35:152–5. 10.1071/AH10897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Australia’s health workforce productivity commission research report. Canberra: Productivity Commission, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Braithwaite J, Testa L, Lamprell G, et al. . Built to last? The sustainability of health system improvements, interventions and change strategies: a study protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7:e018568 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gonçalves‐Bradley DC, Iliffe S, Doll HA, et al. . Early discharge hospital at home. The Cochrane Library 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sandall J, Soltani H, Gates S, et al. . Midwife-led continuity models versus other models of care for childbearing women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;4:CD004667 10.1002/14651858.CD004667.pub5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Khangura JK, Flodgren G, Perera R, et al. . Primary care professionals providing non‐urgent care in hospital emergency departments. The Cochrane Library 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C, et al. . Does the use of laminar flow and space suits reduce early deep infection after total hip and knee replacement?: the ten-year results of the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:85–90. 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, et al. . High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:174–80. 10.7326/0003-4819-154-3-201102010-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Australian Government Productivity Commission. Shifting the dial: 5 year productivity review - Inquiry report. Canberra: Australian Government Productivity Commission, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dijkers M. What is a scoping review. KT Update 2015;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zammarchi L, Casadei G, Strohmeyer M, et al. . A scoping review of cost-effectiveness of screening and treatment for latent tubercolosis infection in migrants from high-incidence countries. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:412 10.1186/s12913-015-1045-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boydell KM, Hodgins M, Pignatiello A, et al. . Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;23:87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hisashige A. The effectiveness and efficiency of disease management programs for patients with chronic diseases. Global journal of health science 2013;5:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Damery S, Flanagan S, Combes G. Does integrated care reduce hospital activity for patients with chronic diseases? An umbrella review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011952 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ciapponi A, Lewin S, Herrera CA, et al. . Delivery arrangements for health systems in low-income countries: an overview of systematic reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;32 10.1002/14651858.CD011083.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Macquarie University. NHMRC partnership centre for health system sustainability. 2018. http://aihi.mq.edu.au/project/nhmrc-partnership-centre-health-system-sustainability (Accessed Sep 2018).

- 30. Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Bank. World bank country and lending groups. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups2017 (Accessed September 2017).

- 33. Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC taxonomy 2015. 2015. https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomy (Accessed Sep 2018).

- 34. Robbins NB. Creating more effective graphs: Wiley, 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024385supp001.pdf (556.5KB, pdf)