Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to compare the effects of intravenous, topical and combined routes of tranexamic acid (TXA) administration on blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA).

Design

This was a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCT) wherein the weighted mean difference (WMD) and relative risk (RR) were used for data synthesis applied in the random effects model. Stratified analyses based on the surgery type, region, intravenous and topical TXA dose and transfusion protocol were also conducted. The main outcomes included intraoperative and total blood loss volume, transfusion rate, low postoperative haemoglobin (Hb) level and postoperative Hb decline. However, the secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay (LOS) and/or occurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Setting

We searched the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane CENTRAL databases for RCTs that compared different routes of TXA administration.

Participants

Patients undergoing TKA or THA.

Interventions

Intravenous, topical or combined intravenous and topical TXA.

Results

Twenty-six RCTs were selected, and the intravenous route did not differ substantially from the topical route with respect to the total blood loss volume (WMD=30.92, p=0.31), drain blood loss (WMD=−34.53, p=0.50), postoperative Hb levels (WMD=−0.01, p=0.96), Hb decline (WMD=−0.39, p=0.08), LOS (WMD=0.15, p=0.38), transfusion rate (RR=1.08, p=0.75) and VTE occurrence (RR=1.89, p=0.15). Compared with the combined-delivery group, the single-route group had significantly increased total blood loss volume (WMD=198.07, p<0.05), greater Hb decline (WMD=0.56, p<0.05) and higher transfusion rates (RR=2.51, p<0.05). However, no significant difference was noted in the drain blood loss, postoperative Hb levels and VTE events between the two groups. The intravenous and topical routes had comparable efficacy and safety profiles.

Conclusions

The combination of intravenous and topical TXA was relatively more effective in controlling bleeding without increased risk of VTE.

Keywords: tranexamic acid, total knee arthroplasty, total hip arthroplasty, IV, topical, meta-analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

All included studies used the randomised controlled design to avoid uncontrolled biases.

The combination of topical and systemic tranexamic acid administration was also studied.

The heterogeneity was assessed using sensitivity, subgroup and meta-regression analyses.

The number of participants in most of the included studies was small, and the prevalence of venous thromboembolism following joint replacement was low.

Only a small number of trials evaluated the combined-delivery group, which precluded sufficient exploration of heterogeneity through subgroup or meta-regression analysis.

Introduction

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic derivative of the amino acid lysine, which inhibits fibrinolysis by blocking the lysine-binding site of plasminogen.1 Currently, it is one of the most commonly used haemostatic drugs and is capable of reducing blood loss volume in surgical patients by approximately 34%.2 3 Moreover, this drug has effectively reduced the blood loss volume and transfusion rate in various surgical settings, including in traumatic haemorrhage,4 caesarean section,5 endoscopic sinus6 and cardiac7 surgeries and arthroplasty.8

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and total hip arthroplasty (THA) are reliable surgical procedures for patients suffering from moderate to severe degenerative joint diseases. Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) is effective in relieving pain, restoring physical function and improving health-related quality of life.9 By 2030, the demand for primary THA is estimated to increase to 572 000 and that for primary TKA is estimated to reach 3.48 million procedures.10 Despite substantial advances in surgical and anaesthetic techniques, TKA and THA are still associated with a large amount of perioperative blood loss.11 The intraoperative blood loss volume in either procedure is generally between 500 and 1500 mL. Additionally, patients may experience a postoperative drop in haemoglobin (Hb) level between 1 and 3 g/dL.12 Up to 50% of the patients undergoing TJA inevitably experience postoperative anaemia.11

The role of TXA during arthroplasty has been an issue of concern for the past two decades. Several previous trials or meta-analyses have mainly focused on comparing TXA and non-TXA, proving that oral, intravenous and topical TXA were associated with significantly reduced perioperative blood loss volume and blood transfusion requirements.13–19 Furthermore, two important meta-analyses showed comparable haemostatic effects between oral and intravenous TXA.20 21 Moreover, another two studies showed that patients who received combined intravenous and topical TXA experienced more benefits than those with single-route TXA administration.22 23 However, few studies have directly compared the different TXA administration routes, and they were limited due to combination of various study design types and relatively small number of included studies.24 In addition, the potential for thromboembolic events (deep vein thromboembolism (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE)) after TXA use represents TXA’s Achilles’ heel.1 Topical TXA application during arthroplasty may be a safer route than the systemic method, which may reduce postoperative haemorrhage without causing hypercoagulation. Notably, the topical route has been shown to be a cost-effective and convenient route for TXA administration during dental, cardiac and spinal surgeries.25 Several relevant trials have been published recently. Thus, we compiled this systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the efficacy and safety of topical and intravenous TXA use in patients undergoing TKA and TXA. In addition, the combination of topical and systemic administration of TXA was evaluated.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in the study design or conduct of the study.

Search strategy

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement issued in 2009.26 Ethical approval was not necessary for this study, as only deidentified pooled data from individual studies were analysed. We searched the PubMed, Embase and Cochrane CENTRAL databases for relevant studies from the time of these databases’ inception to April 2018. The following groups of keywords and medical terms were used for the literature search: ‘tranexamic acid’ and ‘total knee arthroplasty’, ‘total knee replacement’, ‘total hip arthroplasty’, ‘total hip replacement’ or ‘arthroplasty’ and random*, prospective* or trial*. The details of the search strategy in PubMed are shown in online supplementary file 1. This study was restricted to the English language. Furthermore, an additional search was conducted by screening the references of eligible studies.

bmjopen-2018-024350supp001.pdf (50.3KB, pdf)

Selection of studies

Studies were pooled for meta-analysis if they met the following criteria: (1) study design: randomised controlled trials (RCT); (2) patients: those with TKA or THA; (3) intervention and control: comparing intravenous TXA with topical TXA or considering their combination with single TXA regimen; and (4) outcomes: the main outcomes included intraoperative and total blood loss, transfusion rate, low postoperative Hb level and postoperative Hb decline. However, the secondary outcomes included length of hospital stay (LOS) and/or the occurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) which may present as PE or DVT.

Data collection and quality assessment

Two reviewers independently evaluated the eligibility of the collected studies and extracted their data. Any discrepancy was resolved via a consensus meeting. The full text of the eligible studies was reviewed, and information was entered into an electronic database, including author, year of publication, region, sample size, patient characteristics (eg, age, gender, surgery type), intravenous and topical regimen, transfusion threshold, tourniquet use, thromboembolism prophylaxis and outcomes. The Jadad scale was used for the quality assessment of RCTs,27 which assigned a score of 0–5 according to the items of randomisation, blinding and withdrawals reported during the study period.

Statistical analysis

All meta-analyses were conducted using Stata V.12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The relative risk (RR) and 95% CI were used as estimates to analyse dichotomous outcomes. The weighted mean differences (WMD) were used for continuous data and 95% CI was used for estimates. We converted the median to mean following Hozo’s method.28 The random effects model was used for data processing. In addition, statistical heterogeneity among the studies was assessed by using the Cochran’s Q statistic and was quantified according to the I2 statistics. We considered the low, moderate and high heterogeneity as I2 values of ≤25%, 25%–75% and ≥75%, respectively.29 Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing one trial at a time to determine its influence on the overall result. Subgroup analysis was further performed according to the following variables: surgery (THA or TKA), region (Asia, North America or Europe), intravenous dose (≥2 g or <2 g), topical dose (≥2 g or <2 g) and transfusion protocol (strict or loose). The TXA dose of 30 mg/kg was categorised into the subgroup ≥2 g. A strict transfusion protocol was implemented for the threshold of Hb <0.8 g/L. When more than 10 studies were available for certain outcomes, meta-regression analysis was performed to examine the impact of the sample size. A funnel plot was constructed to visually evaluate the publication bias. The Egger’s and Begg’s tests were used for quantitative assessment of publication bias.30 31 A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

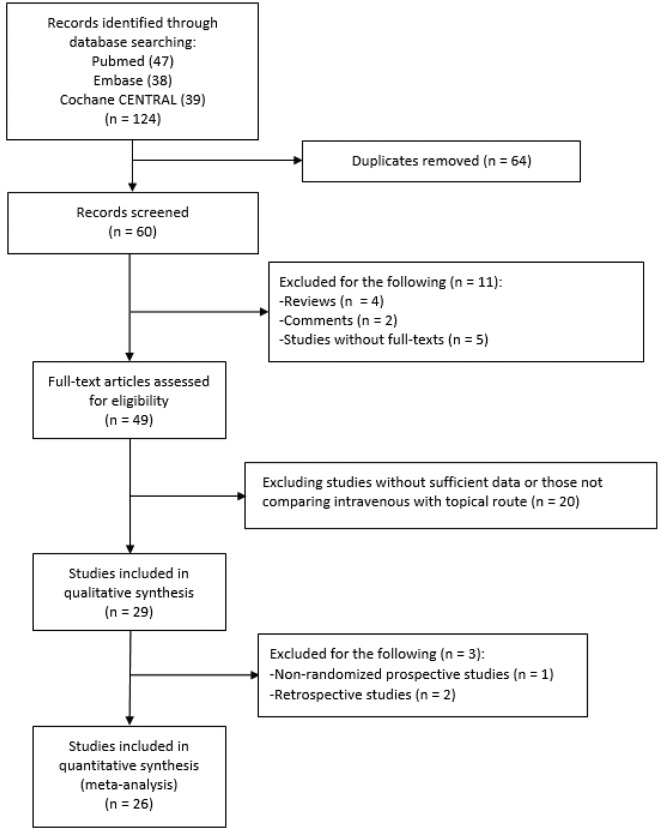

Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study selection process. After step-by-step exclusion, 26 RCTs were finally included. One trial had three comparison arms of intravenous and topical TXA and their combination.32 Tables 1 and 2 show the main features of the trials. We identified 20 RCTs comparing intravenous TXA with topical TXA, with a total of 1912 participants (table 1).32–51 About 15 trials used TXA in TKA procedures and five trials used TXA in THA procedures. Only one TKA study did not use a tourniquet during surgery.49 Ten trials were conducted in Asia, seven in Europe and three in the USA. The patients’ mean age ranged from 44 to 73 years. Seventeen trials presented a thromboprophylaxis protocol, with low-molecular-weight heparin used most frequently. Seven RCTs compared single-route administration (intravenous or intra-articular) with a combination of intravenous and topical routes32 52–57 (table 2), with a total of 877 patients. Most of the studies (5/7) were conducted in the Chinese population. Four studies were conducted on patients who underwent TKA, whereas three studies were performed among those with THA. For the arm of single route, five trials used the intravenous route, one used the topical route and one used both. All studies implemented a thromboprophylaxis protocol. With regard to the TKA studies, only Nielsen et al did not use an intraoperative tourniquet.55 The quality assessment of the selected trials using the Jadad scale is shown in online supplementary table 1, and the total score of the included trials is presented in tables 1 and 2. The total score ranged from 1 to 5, with a mean score of 3.7. The items related to blinding were least satisfied.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram showing the study selection process.

Table 1.

Characteristics of prospective studies comparing topical with intravenous tranexamic acid in patients receiving total knee or hip arthroplasty

| Author (year) | Sample size | Region | Mean age (years) | Female (%) | Surgery | Intravenous regimen | Topical regimen | Transfusion threshold | Tourniquet use | TP | Jadad score |

| Maniar et al

(2012)33 |

80 | India | 67 | 80 | Unilateral TKA | 10 mg/kg | 3 g | Hb<0.85 g/L without CHD, Hb<1 g/L with CHD, anaemic symptoms, organ dysfunction | Yes | LMWH | 5 |

| Seo et al

(2013)34 |

100 | Korea | 67 | 89 | Unilateral TKA | 1.5 g | 1.5 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | NA | 2 |

| Patel et al

(2014)36 |

89 | USA | 65 | 74 | Unilateral TKA | 10 mg/kg | 2 g | Hb<0.8 g/L with anaemic symptoms | Yes | LMWH | 5 |

| Sarzaeem et al

(2014)37 |

100 | Iran | 68 | 86 | Unilateral TKA | 0.5 g | 3 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | NA | 3 |

| Gomez-Barrena et al

(2014)35 |

78 | Spain | 71 | 65 | Unilateral THA | 15 mg/kg twice | 3 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | Enoxaparin | 5 |

| Soni et al

(2014)38 |

40 | India | 69 | 73 | Unspecified TKA | 10 mg/kg three times | 3 g | Hb<0.8 g/L | Yes | LMWH | 2 |

| Wei and Wei (2014)39 |

203 | China | 62 | 64 | THA | 3 g | 3 g | Hb<0.9 g/L | – | LMWH | 5 |

| Aguilera et al

(2015)40 |

100 | Spain | 73 | 70 | Primary TKA | 2 g | 1 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, Hb<0.85 g/L with CHD or over 70 years, Hb<0.9 g/L with anaemic symptoms or organ dysfunction | Yes | LMWH | 3 |

| Digas et al

(2015)41 |

60 | Greece | 71 | 85 | Unilateral TKA | 15 mg/kg | 2 g | Hb<0.85 g/L without CHD, Hb<0.95 g/L with CHD, anaemic symptoms, organ dysfunction | Yes | Tinzaparin | 3 |

| Öztaş et al

(2015)42 |

60 | Turkey | 68 | 85 | Unilateral TKA | 15 mg/kg+10 mg/kg | 2 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | Enoxaparin | 3 |

| Tzatzairis et al

(2016)49 |

80 | Greece | 69 | 80 | Unilateral TKA | 1 g | 1 g | Hb<1 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction | No | LMWH | 3 |

| North et al

(2016)48 |

139 | USA | 65 | 23 | Unilateral THA | 2 g | 2 g | Hb<0.7 g/L, symptomatic anaemia and Hb<0.8 g/L | – | Enoxaparin, rivaroxaban or aspirin | 5 |

| Uğurlu et al (2017)50 | 82 | Turkey | 70 | 76 | Unilateral TKA | 20 mg/kg | 3 g | Hb<0.8 g/L | Yes | Enoxaparin | 3 |

| Zhang et al

(2016)51 |

50 | China | 44 | 46 | Unilateral THA | 1 g | 1 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, symptomatic anaemia and Hb<1 g/L | – | LMWH | 3 |

| May et al

(2016)47 |

131 | USA | 64 | 78 | Unilateral TKA | 2 g | 2 g | Hb<0.7 g/L, symptomatic anaemia and Hb<1 g/L | Yes | LMWH or oral Xa inhibitor | 5 |

| Keyhani et al

(2016)46 |

80 | Iran | 68 | 39 | Unilateral TKA | 0.5 g | 3 g | Hb<0.8 g/L | Yes | LMWH | 2 |

| Drosos et al (2016)45 | 60 | Greece | 70 | 80 | Unilateral TKA | 1 g | 1 g | Hb<1 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction | Yes | NA | 2 |

| Chen et al (2016)44 | 100 | Singapore | 65 | 75 | Unilateral TKA | 1.5 g | 1.5 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | LMWH | 5 |

| Aggarwal et al

(2016)43 |

70 | India | 57 | 36 | Bilateral TKA | 15 mg/kg | 15 mg/kg | Hb<0.8 g/L, Hct<25% | Yes | Aspirin | 4 |

| Xie et al

(2016)32 |

210 | China | 61 | 68 | THA | 1.5 g | 3 g | Hb<0.7 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | NA | Enoxaparin | 5 |

Hb, haemoglobin; Hct, haematocrit; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NA, not available; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; TP, thromboembolism prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of prospective studies comparing combination of topical and intravenous tranexamic acid with single tranexamic acid in patients receiving total knee or hip arthroplasty

| Author (year) | Sample size | Region | Mean age | Female (%) | Surgery | Combination regimen | Single regimen | Transfusion threshold | Tourniquet use | TP | Jadad score |

| Huang et al (2014)52 |

184 | China | 65 | 64 | Unilateral TKA | Intravenous: 1.5 g+topical: 1.5 g | Intravenous: 3 g | Hb<0.7 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | Yes | LMWH | 5 |

| Lin et al

(2015)53 |

120 | China | 71 | 79 | Unilateral TKA | Intravenous: 1 g+topical: 1 g | Topical: 1 g | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<0.9 g/L | Yes | Rivaroxaban | 3 |

| Nielsen et al

(2016)55 |

60 | Denmark | 64 | 53 | Unilateral TKA | Intravenous: 1 g+topical: 3 g | Intravenous: 1 g | Hb<0.75 g/L, Hb<1 g/L with CHD, anaemic symptoms with Hb drop>25% | No | Rivaroxaban | 5 |

| Jain et al

(2016)54 |

119 | India | 69 | 63 | Unilateral TKA | Intravenous: (15 mg/kg preoperative+10 mg/kg postoperative)+topical: 2 g | Intravenous: 15 mg/kg preoperative+10 mg/kg postoperative | Hb<0.7 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<0.8 g/L | Yes | Aspirin | 3 |

| Yi et al (2016)57 | 100 | China | 534 | 47 | THA | Intravenous: 15 mg/kg+topical: 1 g | Intravenous: 15 mg/kg | Hb<0.7 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | NA | Enoxaparin | 5 |

| Xie et al

(2016)32 |

210 | China | 61 | 68 | THA | Intravenous: 1 g+topical: 2 g | Intravenous: 1.5 g, topical 3 g | Hb<0.7 g/L, anaemic symptoms/organ dysfunction when Hb<1 g/L | NA | Enoxaparin | 5 |

| Wu et al

(2016)56 |

84 | China | 60 | 48 | THA | Intravenous: 15 mg/kg+topical: 3 g | Intravenous: 15 mg/kg | Hb<0.8 g/L, anaemic symptoms | NA | LMWH | 3 |

Hb, haemoglobin; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NA, not available; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; TP, thromboembolism prophylaxis.

bmjopen-2018-024350supp002.pdf (60.1KB, pdf)

Intravenous versus topical route

Blood loss

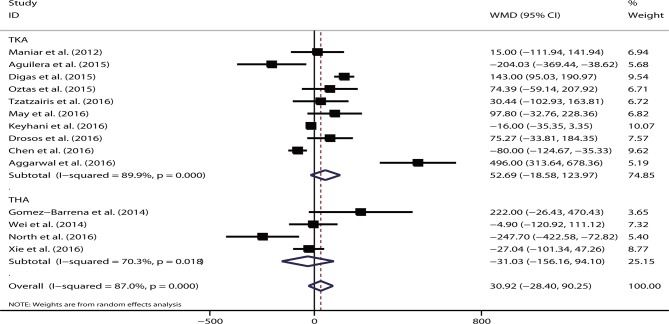

About 14 studies reported on blood loss. No significant difference was observed in the total blood loss volume (WMD=30.92, 95% CI −28.40 to 90.25, p=0.31; I2=87.0%, p<0.05) between intravenous TXA administration and topical administration. This effect was not substantially different for either TKA (WMD=52.69, 95% CI −18.58 to 123.97, p=0.15) or THA (WMD=−31.03, 95% CI −156.16 to 94.10, p=0.63) (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing the efficacy of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid (TXA) on total blood loss. THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Subgroup analysis showed that region (Asia, Europe or USA), intravenous dose (≥2 g or <2 g) or topical dose (≥2 g or <2 g) did not markedly affected the overall effect of the analysis (all p>0.05). None of the studies that significantly changed the overall effect in the sensitivity analysis were identified. Meta-regression demonstrated that the sample size did not account for the heterogeneity of the study (p=0.20). The funnel plot appeared to be symmetrical. No publication bias was revealed based on the Egger’s test (p=0.37) or Begg’s test (p=0.27).

Eight studies presented the outcome of drain blood loss. No significant difference was demonstrated in the intravenous route (WMD=−34.53, 95% CI −135.39 to 66.34, p=0.50; I2=97.2%, p<0.05) and overall effect on TKA (WMD=−38.28, 95% CI −146.29 to 69.73, p=0.49) or THA (WMD=−7.50, 95% CI −95.00 to 80.00, p=0.87).

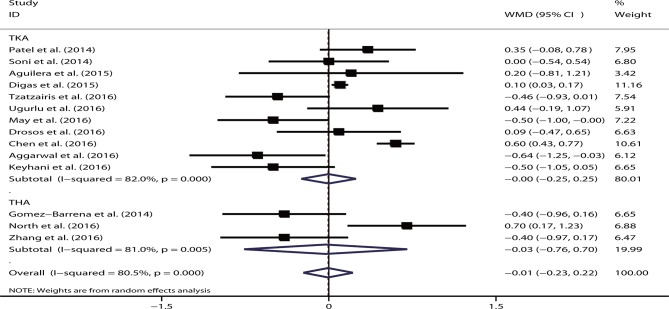

Postoperative Hb

By pooling data from 14 relevant studies, no significant difference was found between the intravenous and topical routes of TXA administration with respect to the postoperative Hb level (WMD=−0.01, 95% CI −0.23 to 0.22, p=0.96; I2=80.5%, p<0.05). The result remained insignificant for TKA (WMD=−0.00, 95% CI −0.25 to 0.25, p=0.99) and THA (WMD=−0.03, 95% CI −0.76 to 0.70, p=0.94) (figure 3). When stratified according to the region and intravenous and topical dose, no significant data were noted in any subgroup (all p>0.05). Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies one at a time; however, no significant difference was noted. The significant role of the sample size in explaining the heterogeneity (p=0.27) was not revealed in the meta-regression analysis. The funnel plot was symmetrical, and no bias was shown based on the Egger’s test (p=0.38) or Begg’s test (p=0.91).

Figure 3.

Forest plot comparing the efficacy of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid (TXA) on postoperative haemoglobin levels. THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Seven studies reported a decline in Hb levels after arthroplasty. The pooled data revealed no significant difference in the intravenous route compared with the topical route (WMD=−0.39, 95% CI −0.82 to 0.04, p=0.08; I2=89.4%, p<0.05). In the subgroup analysis, two studies on THA showed that the intravenous route had a significantly lesser amount of Hb decline than the topical route (WMD=−0.49, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.28, p<0.05). However, no statistical significance was noted on the TKA procedure (WMD=−0.35, 95% CI −1.02 to 0.32, p=0.31). When excluding the studies by Soni et al 38 or Tzatzairis et al,49 the overall effect was significant (p<0.05).

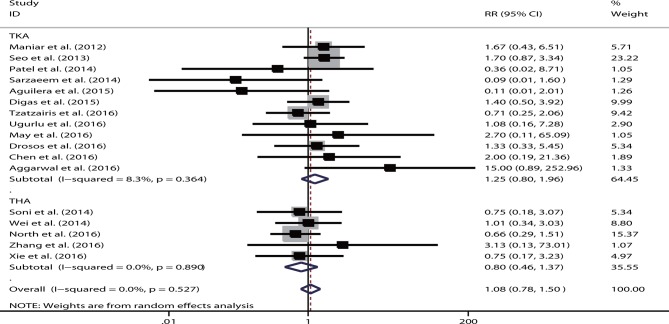

Transfusion rate

Information on the transfusion rate was reported in 17 studies. The pooled results demonstrated that no significant difference was observed in the transfusion rate of the intravenous route (RR=1.08, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.50, p=0.75). No heterogeneity was detected (I2=0%, p=0.63). In a separate analysis completed according to different arthroplasty procedures, the result was not substantially altered (TKA: RR=1.25, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.96, p=0.32; THA: RR=0.80, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.37, p=0.41) (figure 4). When stratified according to the transfusion threshold (ie, loose or strict), no significant result was shown in any subgroup (loose: RR=1.13, p=0.65; strict: RR=1.00, p=1.00). Similarly, no substantially significant results were noted in the subgroups based on the region and intravenous or topical dose (all p>0.05). The sensitivity analysis did not show that the inclusion of any individual study significantly changed the overall effect. The sample size was not the source of heterogeneity in meta-regression analysis (p=0.36). The funnel plot was symmetrical. No publication bias was shown based on the Egger’s test (p=0.69) or Begg’s test (p=1.00).

Figure 4.

Forest plot comparing the efficacy of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid (TXA) on postoperative transfusion rate. RR, relative risk; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Length of hospital stay

The LOS was reported in seven studies. One study was excluded due to 0 SD.49 The pooled results showed that patients with the intravenous and topical routes had similar LOS (WMD=0.15, 95% CI −0.18 to 0.47, p=0.38; I2=90.1%, p<0.05). No marked change was revealed for TKA (WMD=0.27, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.54, p=0.06) or THA (WMD=−0.05, 95% CI −0.42 to 0.32, p=0.80).

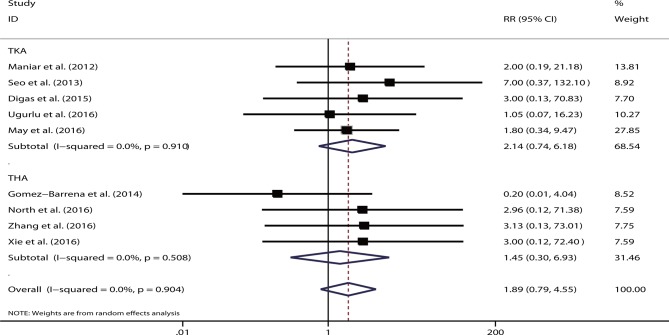

VTE events

A total of 20 studies reported VTE events. However, 11 trials showed no VTE occurrence in any study group,36–40 42–46 49 and thus were excluded from meta-analysis. For the remaining nine trials, except for one study,34 low-molecular-weight heparin was unanimously used for thromboprophylaxis. The aggregated data showed no significant difference for the intravenous versus topical route (RR=1.89, 95% CI 0.79 to 4.55, p=0.15). No heterogeneity was detected (I2=0%, p=0.90). The pooled results remained non-significant for TKA (RR=2.14, 95% CI 0.74 to 6.18, p=0.16) and THA (RR=1.45, 95% CI 0.30 to 6.93, p=0.64) (figure 5). No single study played a substantial role in sensitivity analysis. Sample size was not the source of heterogeneity in meta-regression analysis (p=0.74).

Figure 5.

Forest plot comparing the safety of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid (TXA) on postoperative venous thromboembolism. RR, relative risk; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Combined routes versus single route

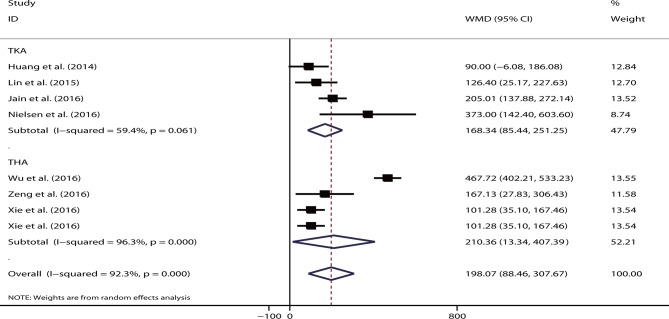

Blood loss

The pooled data showed that the single route had significant increased total blood loss volume (WMD=198.07, 95% CI 88.46 to 307.67, p<0.05; I2=92.3%) compared with the combined regimen. When stratified according to different procedures, the results remained significant for TKA (WMD=168.34, 95% CI 85.44 to 251.25, p<0.05; I2=59.4%) and THA (WMD=210.36, 95% CI 13.34 to 407.39, p<0.05; I2=96.3%) (figure 6). Either the intravenous (WMD=228.93, p<0.05) or topical route (WMD=108.80, p<0.05) showed significantly increased total blood loss volume. Only two studies reported data on drain blood loss,52 56 and their pooled results showed no significant difference between single route and combined regimen (WMD=109.51, 95% CI −34.73 to 253.74, p=0.14; I2=98.1%, p<0.05).

Figure 6.

Forest plot comparing the efficacy of single versus combined routes of tranexamic acid (TXA) on total blood loss. THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Hb level

Three studies presented the postoperative Hb levels, including two on TKA53 55 and one on THA.57 No significant difference was noted on the single route compared with the combined routes (WMD=−0.28, 95% CI −1.30 to 0.74, p=0.59; I2=89.6%, p<0.05). Six studies presented the outcome of Hb decline following surgery. The single route had a significantly greater magnitude of Hb decline than the combined method (WMD=0.56, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.81, p<0.05; I2=85.2%, p<0.05). The result remained significant for studies on both TKA (WMD=0.44, p<0.05) and THA (WMD=0.67, p<0.05).

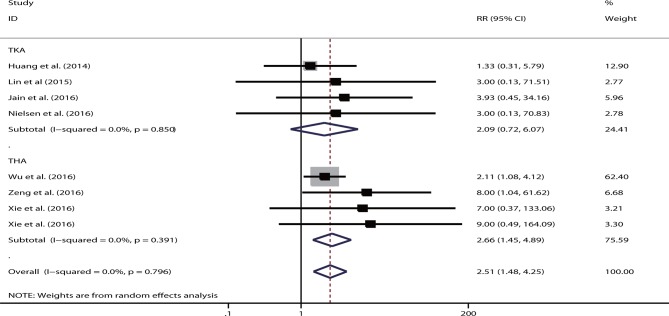

Transfusion rate

Seven studies were eligible, including four studies on TKA52–55 and three studies on THA.32 56 57 Xie et al reported the use of both intravenous and topical TXA administration.32 The single route had a significantly higher transfusion rate than the combined group (RR=2.51, 95% CI 1.48 to 4.25, p<0.05). No heterogeneity was shown (I2=0%). This trend remained significant for studies on TKA (RR=0.09, p<0.05) and THA (RR=2.66, p<0.05) (figure 7). The intravenous route still showed a markedly higher transfusion rate than the combination group (RR=2.39, 95% CI 1.38 to 4.11, p<0.05). However, a significantly higher transfusion rate (RR=5.45, 95% CI 0.64 to 46.42, p=0.12) was not observed in two studies that used the topical route.

Figure 7.

Forest plot comparing the efficacy of single versus combined routes of tranexamic acid (TXA) on blood transfusion rate. RR, relative risk; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Length of hospital stay

Four studies were relevant in terms of evaluating the LOS,32 52 55 56 and Xie et al presented on both intravenous and topical routes.32 The LOS did not differ significantly between the single route and combination regimen (WMD=0.09, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.28, p=0.36; I2=45.8%, p=0.12). No significant difference was noted in the LOS of patients who underwent TKA or THA (both p>0.05). The result remained non-significant (WMD=0.14, p=0.22) as reported in four studies conducting intravenous TXA administration.

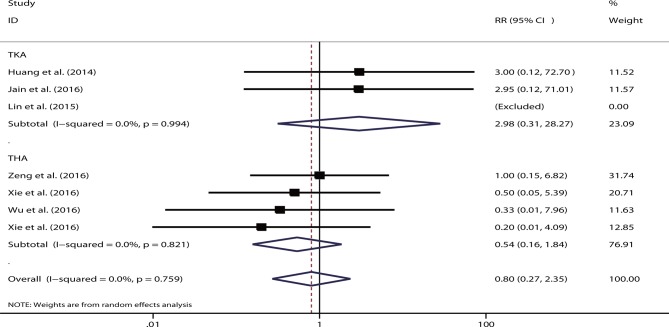

VTE events

Six studies were eligible for consideration of VTE events.32 52–54 56 57 One study showed zero events for both arms,53 and one study presented both intravenous and topical routes.32 The pooled data suggested that the risk of VTE events did not differ substantially between the single and combination routes (RR=0.80, 95% CI 0.27 to 2.35, p=0.68; I2=0%). No statistical significance was shown between the different types of arthroplasty (TKA: RR=2.98, p=0.34; and THA: RR=0.54, p=0.32) (figure 8) or different single-delivery routes (intravenous: RR=0.98, p=0.97; topical: RR=0.20, p=0.30).

Figure 8.

Forest plot comparing the safety of single versus combined routes of postoperative venous thromboembolism. RR, relative risk; THA, total hip arthroplasty; TKA, total knee arthroplasty.

Discussion

In recent history, TXA is one of the most commonly used haemostatic drugs for reducing blood loss during total joint replacement and ensuring fast postoperative recovery. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive meta-analysis of updated randomised trials investigating the efficacy and safety of intravenous versus topical TXA in patients undergoing TKA and THA. We found that the intravenous and topical routes did not differ substantially for the outcomes of total blood loss, drain blood loss, postoperative Hb level, postoperative Hb decline, transfusion rate and/or LOS. The incidence of VTE was low for both studied arms. The two routes appeared to be of comparable safety profiles for patients undergoing arthroplasty. Except for two THA studies showing that the intravenous route resulted in a lesser magnitude of Hb decline, the overall effect remained insignificant for the majority of subgroups stratified based on THA or TKA. When comparing the combination regimen with the single route, our meta-analysis demonstrated that the combination of intravenous and topical routes could significantly decrease the total blood loss volume and reduce transfusion requirements. A relatively lesser degree of Hb decline was revealed in the combined-delivery regimen. LOS was similar for both arms. Overall, VTE events occurred rarely for both routes, and no marked difference was revealed when comparing the combination and single-route groups.

Following intravenous administration, TXA is spread in the extracellular and intracellular compartments. It rapidly diffuses into the synovial fluid until its concentration reaches to that of the serum. The biological half-life is 3 hours in the joint fluid, and 90% of TXA is eliminated within 24 hours after administration.58 For the intra-articular route, TXA administration could provide a maximum local dose at the site where needed. Local administration of TXA inhibits fibrin dissolution and induces partial microvascular haemostasis.59 Particularly, the release of the tourniquet always causes increased fibrinolysis, which can be attenuated by topical TXA.60 Compared with the intravenous route, the systemic absorption for local use is at a substantially lower level.61 Additionally, topical TXA could be safer than intravenous TXA in patients with renal impairment.41 Moreover, the antifibrinolytic effect of topical TXA is limited to postoperative bleeding. Preoperatively, intravenous TXA was associated with lower blood loss volume during arthroplasty, which explains the greater benefit of combined regimen of using intravenous along with topical routes.62

Several meta-analyses have been published on TXA use during arthroplasty. Both intravenous and intra-articular administration of TXA have been demonstrated to reduce the blood loss volume without increased risk of thromboembolic complications, and the use of intravenous TXA is considerably more common.13 14 16 21–24 63–68 However, most of these meta-analyses compared TXA with a placebo. We only identified two meta-analyses that performed a head-to-head comparison between the topical and intravenous routes, including one on TKA24 and the other on THA.61 Both analyses included only a very small number of studies. In addition, a methodological flaw was observed because they included non-randomised or retrospective studies.

Our meta-analysis has several apparent strengths. First, all included studies were RCTs. The number of included trials was also larger in our meta-analysis than that in other meta-analyses, which increased the statistical power. All relevant trials published during the past 2 years were analysed. In addition, we investigated the efficacy of the combination of topical and intravenous routes. Given the similar mechanism of TXA administration in both TKA and THA, both procedures were considered for this meta-analysis.

Several clinical variables may influence the efficacy of TXA. The optimal dose of TXA remained controversial. When topically applied, there was no difference in the efficacy of 1.5 g vs 3 g of TXA wash in reducing perioperative blood loss.69 However, a meta-analysis of seven trials suggested that a higher dose of TXA (>2 g), but not a low dose, was correlated with significantly reduced transfusion requirements.15 In our subgroups stratified based on the high (≥2 g) and low doses (<2 g), no significant difference was observed between the doses and most outcomes. In fact, the effect on blood loss reduction between low-dose and high-dose TXA may be explained by the ‘tissue contact time’—the time when TXA is applied on the joint bed.70 At least 5 min of contact time was allowed before TXA was suctioned from the wound to allow for the repair of the retinaculum.44 Sa-Ngasoongsong et al suggested that prolonging the contact time could enhance the effects of low-dose TXA.70

We were aware of several limitations with respect to this meta-analysis. The number of participants in most of the included studies was small. As the prevalence of VTE was low following joint replacement, trials with a larger sample size were further needed to increase the statistical power. Only a small number of trials evaluated the combined-delivery group, which precluded sufficient exploration of heterogeneity through subgroup or meta-regression analysis. Additionally, many included trials had methodological deficits, such as the description of the randomisation process, blinded assessment and/or explanation of withdrawal and dropouts. Several studied outcomes have been criticised for their inaccuracy. For example, drains may not be suitable for the measurement of blood loss volume, as the haematocrit in the drain output declined over time and drains may increase the blood loss. The existing literature provided variable and heterogeneous information with respect to the clinical features. For instance, the estimated blood loss, timing of Hb measurement and indications for blood transfusion were not standardised among various trials. Several studies used tourniquet to facilitate the arthroplasty procedure, which may adversely impact the efficacy of intraoperative intravenous TXA.44 A meta-analysis showed that the use of a tourniquet was associated with increased risk for vein thrombosis.71 Intraoperative hypotension or hypertension may affect the blood loss volume, whereas related information was unclear in most included trials. Additionally, LOS may be further affected by the patients’ age, surgical experience and/or infection complications. We speculated that these confounding factors were balanced between different comparison groups due to the randomised design. Not searching grey literature and articles in other languages might have also skewed the results. Finally, high heterogeneity was observed in places that might limit the ability to make strong inferences.

Conclusions

Our meta-analysis showed that intravenous and topical TXA had comparable efficacy and safety profiles. The combined-delivery method using intravenous and topical TXA may be the most effective strategy that can be used while maintaining patient safety.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

QS and JL contributed equally.

Contributors: QS and JL contributed to the conception and design of the study. QS, JL, JC, CZ, CL and YJ contributed to data acquisition or analysis and interpretation. QS and JL were involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All of the data were based on published studies and no additional data are available.

References

- 1. Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs 1999;57:1005–32. 10.2165/00003495-199957060-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henry DA, Carless PA, Moxey AJ, et al. . Anti-fibrinolytic use for minimising perioperative allogeneic blood transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;19:CD001886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ker K, Prieto-Merino D, Roberts I. Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression of the effect of tranexamic acid on surgical blood loss. Br J Surg 2013;100:1271–9. 10.1002/bjs.9193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberts I, Shakur H, Afolabi A, et al. . The importance of early treatment with tranexamic acid in bleeding trauma patients: an exploratory analysis of the CRASH-2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:1096–101. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60278-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simonazzi G, Bisulli M, Saccone G, et al. . Tranexamic acid for preventing postpartum blood loss after cesarean delivery: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:28–37. 10.1111/aogs.12798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pundir V, Pundir J, Georgalas C, et al. . Role of tranexamic acid in endoscopic sinus surgery - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rhinology 2013;51:291–7. 10.4193/Rhin13.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Adler Ma SC, Brindle W, Burton G, et al. . Tranexamic acid is associated with less blood transfusion in off-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2011;25:26–35. 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang Z-G, Chen W-P, Wu L-D. Effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:1153–9. 10.2106/JBJS.K.00873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, et al. . Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86-A:963–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. . Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:780–5. 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Erkocak OF, et al. . Blood management after total joint arthroplasty in the United States: 19-year trend analysis. Transfusion 2016;56:1112–20. 10.1111/trf.13518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sculco TP, Baldini A, Keating EM. Blood management in total joint arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect 2005;54:51–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yue C, Pei F, Yang P, et al. . Effect of topical tranexamic acid in reducing bleeding and transfusions in TKA. Orthopedics 2015;38:315–24. 10.3928/01477447-20150504-06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang H, Shen B, Zeng Y. Blood loss and transfusion after topical tranexamic acid administration in primary total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2015;38:e1007–16. 10.3928/01477447-20151020-10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Panteli M, Papakostidis C, Dahabreh Z, et al. . Topical tranexamic acid in total knee replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee 2013;20:300–9. 10.1016/j.knee.2013.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gao F, Ma J, Sun W, et al. . Topical fibrin sealant versus intravenous tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2016;32:31–7. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liu Q, Geng P, Shi L, et al. . Tranexamic acid versus aminocaproic acid for blood management after total knee and total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2018;54:105–12. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.04.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu J, Zhu Y, Lei P, et al. . Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement: a PRISMA-compliant meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2017;96:e9552 10.1097/MD.0000000000009552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang LK, Ma JX, Kuang MJ, et al. . The efficacy of tranexamic acid using oral administration in total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2017;12:159 10.1186/s13018-017-0660-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li GL, Li YM. Oral tranexamic acid can reduce blood loss after total knee and hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2017;46:27–36. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang LK, Ma JX, Kuang MJ, et al. . Comparison of oral versus intravenous application of tranexamic acid in total knee and hip arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2017;45:77–84. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.07.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Z, Shen X. The efficacy of combined intra-articular and intravenous tranexamic acid for blood loss in primary total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2017;96:e8123 10.1097/MD.0000000000008123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yang L, Du S, Sun Y. Is combined topical and intravenous tranexamic acid superior to single use of tranexamic acid in total joint arthroplasty?: a meta-analysis from randomized controlled trials. Medicine 2017;96:e7609 10.1097/MD.0000000000007609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang H, Shen B, Zeng Y. Comparison of topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled and prospective cohort trials. Knee 2014;21:987–93. 10.1016/j.knee.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guzel Y, Gurcan OT, Golge UH, et al. . Topical tranexamic acid versus autotransfusion after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg 2016;24:179–82. 10.1177/1602400212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. . Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996;17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol 2005;5:13 10.1186/1471-2288-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. . Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 1994;50:1088–101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, et al. . Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ 1997;315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Xie J, Ma J, Yue C, et al. . Combined use of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid following cementless total hip arthroplasty: a randomised clinical trial. Hip Int 2016;26:36–42. 10.5301/hipint.5000291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Maniar RN, Kumar G, Singhi T, et al. . Most effective regimen of tranexamic acid in knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled study in 240 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:2605–12. 10.1007/s11999-012-2310-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Seo JG, Moon YW, Park SH, et al. . The comparative efficacies of intra-articular and IV tranexamic acid for reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:1869–74. 10.1007/s00167-012-2079-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gomez-Barrena E, Ortega-Andreu M, Padilla-Eguiluz NG, et al. . Topical intra-articular compared with intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary total knee replacement: a double-blind, randomized, controlled, noninferiority clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2014;96:1937–44. 10.2106/JBJS.N.00060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Patel JN, Spanyer JM, Smith LS, et al. . Comparison of intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1528–31. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sarzaeem MM, Razi M, Kazemian G, et al. . Comparing efficacy of three methods of tranexamic acid administration in reducing hemoglobin drop following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1521–4. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.02.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Soni A, Saini R, Gulati A, et al. . Comparison between intravenous and intra-articular regimens of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss during total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1525–7. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.03.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wei W, Wei B. Comparison of topical and intravenous tranexamic acid on blood loss and transfusion rates in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:2113–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Aguilera X, Martínez-Zapata MJ, Hinarejos P, et al. . Topical and intravenous tranexamic acid reduce blood loss compared to routine hemostasis in total knee arthroplasty: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135:1017–25. 10.1007/s00402-015-2232-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Digas G, Koutsogiannis I, Meletiadis G, et al. . Intra-articular injection of tranexamic acid reduce blood loss in cemented total knee arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25:1181–8. 10.1007/s00590-015-1664-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Öztaş S, Öztürk A, Akalin Y, et al. . The effect of local and systemic application of tranexamic acid on the amount of blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion after total knee replacement. Acta Orthop Belg 2015;81:698–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Aggarwal AK, Singh N, Sudesh P. Topical vs intravenous tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss after bilateral total knee arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:1442–8. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.12.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen JY, Chin PL, Moo IH, et al. . Intravenous versus intra-articular tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty: a double-blinded randomised controlled noninferiority trial. Knee 2016;23:152–6. 10.1016/j.knee.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Drosos GI, Ververidis A, Valkanis C, et al. . A randomized comparative study of topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid administration in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) total knee replacement. J Orthop 2016;13:127–31. 10.1016/j.jor.2016.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Keyhani S, Esmailiejah AA, Abbasian MR, et al. . Which route of tranexamic acid administration is more effective to reduce blood loss following total knee arthroplasty? Arch Bone Jt Surg 2016;4:65–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. May JH, Rieser GR, Williams CG, et al. . The assessment of blood loss during total knee arthroplasty when comparing intravenous vs intracapsular administration of tranexamic acid. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2452–7. 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. North WT, Mehran N, Davis JJ, et al. . Topical vs intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:1022–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tzatzairis TK, Drosos GI, Kotsios SE, et al. . Intravenous vs topical tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty without tourniquet application: a randomized controlled study. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2465–70. 10.1016/j.arth.2016.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Uğurlu M, Aksekili MA, Çağlar C, et al. . Effect of topical and intravenously applied tranexamic acid compared to control group on bleeding in primary unilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg 2017;30:152–7. 10.1055/s-0036-1583270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang Y, Zhang L, Ma X, et al. . What is the optimal approach for tranexamic acid application in patients with unilateral total hip arthroplasty? Orthopade 2016;45:616–21. 10.1007/s00132-016-3252-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huang Z, Ma J, Shen B, et al. . Combination of intravenous and topical application of tranexamic acid in primary total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:2342–6. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Lin SY, Chen CH, Fu YC, et al. . The efficacy of combined use of intraarticular and intravenous tranexamic acid on reducing blood loss and transfusion rate in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:776–80. 10.1016/j.arth.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jain NP, Nisthane PP, Shah NA. Combined administration of systemic and topical tranexamic acid for total knee arthroplasty: can it be a better regimen and yet safe? a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:542–7. 10.1016/j.arth.2015.09.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Nielsen CS, Jans Ø, Ørsnes T, et al. . Combined intra-articular and intravenous tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016;98:835–41. 10.2106/JBJS.15.00810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wu YG, Zeng Y, Yang TM, et al. . The efficacy and safety of combination of intravenous and topical tranexamic acid in revision hip arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:2548–53. 10.1016/j.arth.2016.03.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yi Z, Bin S, Jing Y, et al. . Tranexamic acid administration in primary total hip arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial of intravenous combined with topical versus single-dose intravenous administration. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2016;98:983–91. 10.2106/JBJS.15.00638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nilsson IM. Clinical pharmacology of aminocaproic and tranexamic acids. J Clin Pathol Suppl 1980;14:41–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Sukeik M, Alshryda S, Haddad FS, et al. . Systematic review and meta-analysis of the use of tranexamic acid in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:39–46. 10.1302/0301-620X.93B1.24984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Aglietti P, Baldini A, Vena LM, et al. . Effect of tourniquet use on activation of coagulation in total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;371:169–77. 10.1097/00003086-200002000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sun X, Dong Q, Zhang YG. Intravenous versus topical tranexamic acid in primary total hip replacement: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2016;32:10–18. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.05.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Benoni G, Fredin H, Knebel R, et al. . Blood conservation with tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blind study in 40 primary operations. Acta Orthop Scand 2001;72:442–8. 10.1080/000164701753532754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Shemshaki H, Nourian SM, Nourian N, et al. . One step closer to sparing total blood loss and transfusion rate in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of different methods of tranexamic acid administration. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2015;135:573–88. 10.1007/s00402-015-2189-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Wei Z, Liu M. The effectiveness and safety of tranexamic acid in total hip or knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis of 2720 cases. Transfus Med 2015;25:151–62. 10.1111/tme.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wu Q, Zhang HA, Liu SL, et al. . Is tranexamic acid clinically effective and safe to prevent blood loss in total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis of 34 randomized controlled trials. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25:525–41. 10.1007/s00590-014-1568-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yu X, Li W, Xu P, et al. . Safety and efficacy of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty. Med Sci Monit 2015;21:3095–103. 10.12659/MSM.895801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Chen S, Wu K, Kong G, et al. . The efficacy of topical tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:81 10.1186/s12891-016-0923-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huang GP, Jia XF, Xiang Z, et al. . Tranexamic acid reduces hidden blood loss in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a comparative study and meta-analysis. Med Sci Monit 2016;22:797–802. 10.12659/MSM.895571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wong J, Abrishami A, El Beheiry H, et al. . Topical application of tranexamic acid reduces postoperative blood loss in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:2503–13. 10.2106/JBJS.I.01518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Sa-Ngasoongsong P, Wongsak S, Chanplakorn P, et al. . Efficacy of low-dose intra-articular tranexamic acid in total knee replacement; a prospective triple-blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2013;14:340 10.1186/1471-2474-14-340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhang W, Li N, Chen S, et al. . The effects of a tourniquet used in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2014;9:13 10.1186/1749-799X-9-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024350supp001.pdf (50.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024350supp002.pdf (60.1KB, pdf)