Abstract

Objective

The role of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as an indicator of inflammation has been the focus of research recently. We aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PLR for sepsis.

Design

A retrospective cohort study.

Setting and participants

Data were extracted from the Multiparameter Intelligent Monitoring in Intensive Care III database. Data on 5537 sepsis patients were analysed.

Methods

Logistic regression was used to explore the association between PLR and hospital mortality. Subgroup analyses were performed based on vasopressor use, acute kidney injury (AKI) and a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score >10.

Results

In the logistic model with linear spline function, a PLR >200 was significantly (OR 1.0002; 95% CI 1.0001 to 1.0004) associated with mortality; the association was non-significant for PLRs ≤200 (OR 0.997; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.67). In the logistic model using the PLR as a design variable, only high PLRs were significantly associated with mortality (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53); the association with low PLRs was non-significant (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.38). In the subgroups with vasopressor use, AKI and a SOFA score >10, the association between high PLR and mortality was non-significant; this remained significant in the subgroups without vasopressor use (OR 1.39; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.77) and AKI (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.99) and with a SOFA score ≤10 (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.17 to 1.94).

Conclusions

High PLRs at admission were associated with an increased risk of mortality. In patients with vasopressor use, AKI or a SOFA score >10, this association was non-significant.

Keywords: sepsis, plr, mortality, mimic Iii

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The large sample size facilitated a robust conclusion.

Subgroup analysis was performed to investigate the interaction between disease severity and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

Preintensive care unit data were not available in this database, which may lead to bias.

Patients with septic shock could not be identified in this database.

Introduction

Sepsis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and it results from a dysregulation of the systemic inflammatory response to infection.1 2 Despite significant advances in the pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies for sepsis, the mortality remains high,3 at 300 deaths per 100 000 people.4 An extremely complex systemic expression of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory response plays a critical role in the pathophysiological process of sepsis, which is strongly associated with an increased risk of mortality.5 Identifying patients who are at a high risk of poor outcomes, in the early stage of sepsis, is vital for timely and adequate intervention.6 While a significant amount of effort has been put into investigating promising biomarkers, the challenge of identifying these at-risk patients remains.7

In recent years, studies have reported that platelets and lymphocytes play critical roles in the inflammatory process. Therefore, the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)—a novel inflammatory factor—has received research attention recently, as it may act as an indicator of inflammation8 in a wide spectrum of diseases, such as myocardial infarction,9 acute kidney injury (AKI),10 hepatocellular carcinoma11 and non-small cell lung cancer.12

Based on the findings of previous studies, it is reasonable to speculate the presence of a potential relationship between PLR and mortality for sepsis. However, no investigation has been conducted. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate the prognostic value of PLR for sepsis.

Materials and methods

Database introduction

This database included more than 58 000 patients who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center from 2001 to 2008.13 YS obtained access to this database (certification number: 1564657) and was responsible for data extraction.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adult patients meeting the criteria for sepsis were initially screened. The definition of sepsis was adapted from the recommendation in the Surviving Sepsis Campaign 2016.14 Accordingly, sepsis was defined as the presence of a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score ≥2 within 24 hours after ICU admission, accompanied by at least one infection site. The following criteria were used to exclude patients from this analysis: (1) age lower than 18 years; (2) having spent less than 48 hours in the ICU; and (3) absence of data on the serum platelet and lymphocyte counts within 24 hours after ICU admission. For patients who were admitted to the ICU more than once, only the first ICU stay was considered in this study.

Data extraction

Data on the demographic characteristics, laboratory outcomes, infection sites, vasopressor use and disease severity score were extracted from the database. Only patients with data on the serum platelet and lymphocyte counts within the first 24 hours after ICU admission were included. The first blood sample after ICU admission was used to calculate the PLR, which was defined as the ratio of the absolute platelet count and absolute lymphocyte count. Septic shock was considered as a special subgroup of sepsis. However, it was difficult to identify patients with septic shock in this database due to a lack of relevant information. Thus, data on vasopressor use were extracted for the subgroup analysis. Vasopressor use was defined as the use of any vasopressor agent, including norepinephrine, epinephrine, dobutamine, dopamine or vasopressin, within 48 hours after ICU admission.

Outcome definition

The primary endpoint was hospital mortality, which was defined as death during hospitalisation. The presence of AKI was defined according to the Creatinine-based Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcome criteria without urine output.15 16 A 1.5-fold increase in the serum creatinine (SCr) level during the ICU stay, relative to the level at the baseline, was considered as the presence of AKI. In the present cohort, data on the baseline SCr values were missing in 20.3% of the cases. As AKI was not the primary outcome, we used a reported estimation equation 17 (reported median absolute error was 0.1–0.2 mg/dL) to calculate the missing values for patients without previous SCr data: SCr=0.74–0.2 (if female)+0.08 (if black)+0.0039 * age (in years).

Management of missing data

Variables with missing data are common in the MIMIC III database, as it comprises more than 58 000 admissions. The percentage of missing values of serum lactate and albumin was 12.9% and 26.3%, respectively. For serum lactate, the crude comparison within three PLR levels is presented in table 1 but was not included in the logistic models. The serum albumin was completely excluded from this study. For the rest of the variables included in the current study, the percentage of missing values was less than 5%. For normal distribution variables, such as age and fluid balance, we replaced the missing values with their mean values; for non-normal distribution parameters, missing values were replaced by the respective median, instead of using the multiple imputation technique. For dichotomous variables with less than 5% of missing values, the missing values were not filled.

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics within three PLR levels

| Variable | PLR ≤150 (n=1780) |

150<PLR≤250 (n=1380) |

PLR >250 (n=2377) |

P value |

| Age (years) | 63.0±16.6 | 65.0±16.6 | 66.1±15.5 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 805 (45.2) | 590 (42.7) | 1096 (46.1) | 0.133 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.8±8.9 | 34.1±13.5 | 35.2±39.5 | 0.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| White | 1202 (67.5) | 987 (71.5) | 1761 (74.0) | 0.754 |

| Black | 180 (10.1) | 101 (7.3) | 146 (6.1) | <0.001 |

| Asian | 39 (2.2) | 30 (2.1) | 71 (2.9) | 0.169 |

| Emergency | 1641 (92.1) | 1284 (93.0) | 2229 (93.7) | 0.138 |

| ICU type, n (%) | ||||

| MICU | 953 (53.5) | 727 (52.6) | 1362 (57.2) | 0.008 |

| CCU/CSRU | 413 (23.2) | 323 (23.4) | 453 (19.0) | 0.001 |

| TSICU/SICU | 414 (23.2) | 330 (23.9) | 562 (23.6) | 0.908 |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | ||||

| Norepinephrine | 566 (31.7) | 374 (27.1) | 711 (29.9) | 0.016 |

| Dopamine | 198 (11.1) | 151 (10.9) | 256 (10.7) | 0.013 |

| Epinephrine | 67 (3.7) | 28 (2.0) | 37 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Vasopressin | 156 (8.7) | 88 (6.3) | 172 (7.2) | 0.033 |

| Overall vasopressor use | 701 (39.3) | 482 (34.9) | 858 (36.1) | 0.022 |

| Fluid input/output (mL/kg/48 hours) | ||||

| Fluid intake | 99.9±60.9 | 90.7±57.6 | 97.2±61.2 | <0.001 |

| Urine output | 42.0±32.0 | 42.9±30.3 | 41.9±29.5 | 0.5659 |

| Fluid balance | 46.7±59.4 | 38.3±55.1 | 46.0±60.4 | <0.001 |

| Infection site, n (%) | ||||

| Respiratory infection | 1048 (58.8) | 929 (67.3) | 1580 (66.4) | <0.001 |

| Blood infection | 768 (43.1) | 509 (36.8) | 998 (41.9) | 0.001 |

| Urinary infection | 549 (30.8) | 409 (29.6) | 682 (28.6) | 0.323 |

| Abdominal infection | 245 (13.7) | 159 (11.5) | 334 (14.0) | 0.072 |

| Cerebral infection | 153 (8.5) | 106 (7.6) | 169 (7.1) | 0.206 |

| Disease severity scores | ||||

| SOFA on ICU admission median (IQR) | 6 (4–9) | 5 (4–8) | 5 (3–7) | <0.001 |

| Maximum SOFA during ICU stay median (IQR) | 10 (7–14) | 9 (7–12) | 9 (7–12) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory outcomes | ||||

| Maximum serum creatinine (mg/L) | 2.5±2.7 | 2.2±2.1 | 2.1±1.9 | <0.001 |

| Minimum haemoglobin level (g/dL) | 8.3±1.7 | 8.69±1.7 | 8.4±1.6 | <0.001 |

| Maximum serum sodium (mmol/L) | 145.1±5.4 | 145.0±5.2 | 144.6±5.1 | 0.009 |

| Maximum serum lactate (mmol/L) | 4.1±3.8 (n=1536) | 3.4±3.1 (n=1174) | 3.1±3.0 (n=2112) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (109/L) | 146.7±88.0 | 225.1±107.2 | 197.5±163.4 | <0.001 |

| Lymphocyte count (109/L) | 2.1±5.7 | 1.1±0.5 | 0.68±0.4 | <0.001 |

| PLR | 91.8±37.1 | 195.8±28.6 | 557.5±484.8 | <0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes | ||||

| ICU LOS | 9.9±10.1 | 9.3±8.7 | 10.1±9.9 | 0.071 |

| Hospital LOS | 17.7±15.1 | 16.6±13.5 | 17.2±13.7 | 0.082 |

| AKI, n (%) | 861 (48.3) | 601 (43.5) | 1080 (45.4) | 0.022 |

| Hospital mortality, n (%) | 475 (26.6) | 291 (21.0) | 621 (26.1) | <0.001 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; BMI body mass index; CCU, coronary care unit; CSRU, cardiac surgery care unit; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS length of stay; MICU, multiple intensive care unit; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SICU, surgical intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; TSICU, traumatic surgical intensive care unit

Patient and public involvement

No patient was involved in any part of this study.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean±SD or median (IQR), as appropriate. A Student’s t-test, analysis of variance, Wilcoxon rank-sum test or Kruskal-Wallis test was used, as appropriate. Categorical data were expressed as proportions and compared using the χ2 test. A knot of PLR (at a level of around 200) was detected using the Lowess smoother technique; thus, the linear spline function was initially used in the multivariate logistic regression. Thereafter, all the patients were further divided into three levels: those with a PLR ≤150 (level 1), 150<PLR≤250 (level 2) and PLR >250 (level 3). Variables including demographic characteristics, infection sites, disease severity score and laboratory measures potentially associated with mortality or those that had a p value <0.20 in the univariate analyses were included in the multivariate logistic regression analyses.18 19 An extended model approach was used for covariate adjustment: model 1=adjusted for age, admitted ICU type; model 2=model 1+(fluid balance at 48 hours after ICU admission); model 3=model 2+(infection sites); and model 4=model 3+(maximum SOFA score during the ICU stay). As we detected a U-shaped association between PLR and mortality, we did not introduce interaction items (such as PLR multiply other variables) in the logistic models. Instead, subgroup analyses were performed, according to the presence of AKI and vasopressor use and the median SOFA score. Multicollinearity was tested using the variance inflation factor (VIF) method, with a VIF ≥5 indicating the presence of multicollinearity. All the logistic regression models underwent a goodness of fit test. A two-tailed test was performed, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA V.11.2.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Data on a total of 5537 sepsis patients were included in this analysis. The overall mortality observed was 25.1%. Data on the comparisons of the baseline characteristics between the three PLR levels are listed in table 1. The mean age at admission was 64.9 years, and 44.9% of the participants were men. The rate of vasopressor use (701/1780 vs 482/1380, p=0.01) and a maximum SOFA score (10 (7–14) vs 9 (7–12), p<0.001) were significantly higher in PLR level 1 than level 2; the presence of these variables was non-significant in level 3. The mortality was significantly higher among those in level 1 (475/1780 vs 291/1380, p<0.001) and level 3 (621/2377 vs 291/1380, p=0.001).

Association between PLR and hospital mortality

The PLR was initially used as a continuous variable in the logistic model, using linear spline function, as shown in table 2. We observed that, for PLRs ≤200, the OR of mortality was non-significant (OR 0.997; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.67), while the OR for PLRs >200 was significant (OR 1.0002; 95% CI 1.0001 to 1.0004), after adjustment for covariates including the SOFA score, with a mean VIF of 2.89. The crude association between hospital mortality and PLR was also presented in online supplementary figure S1. In the extended multiple logistic regression analysis (table 3), both low and high PLR levels were significantly associated with increased hospital mortality, in model 1 (OR 1.41; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.67 and OR 1.28; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.51, respectively), model 2 (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.13 to 1.59 and OR 1.23; 95% CI 1.05 to 1.45, respectively) and model 3 (OR 1.35; 95% CI 1.14 to 1.61 and OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.43, respectively). However, after adjustment for the maximum SOFA score in model 4, the OR for low PLR levels became non-significant (OR 1.15; 95% CI 0.96 to 1.38, p=0.123), while that for high PLR levels remained significant (OR 1.29; 95% CI 1.09 to 1.53, p=0.003), with a mean VIF of 2.53. The ORs of the covariates in model 4 are listed in online supplementary table S1.

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regressions of PLR using linear spline function

| Variables | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P value |

| PLR (≤200) | 0.997 | 0.996 to 0.998 | <0.001 | 0.9993 | 0.9980 to 1.0006 | 0.319 |

| PLR (>200) | 1.0002 | 1.0001 to 1.0004 | 0.001 | 1.0002 | 1.0000 to 1.0003 | 0.025 |

| Age (>65 years) | 1.77 | 1.56 to 2.11 | <0.001 | 2.32 | 1.99 to 2.64 | <0.001 |

| Maximum SOFA | 1.20 | 1.18 to 1.22 | <0.001 | 1.18 | 1.16 to 1.20 | <0.001 |

| Urinary infection | 0.66 | 0.57 to 0.76 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.56 to 0.76 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory infection | 1.29 | 1.13 to 1.47 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 1.09 to 1.45 | 0.002 |

| Blood infection | 2.14 | 1.89 to 2.42 | <0.001 | 1.49 | 1.29 to 1.71 | <0.001 |

| Fluid balance (mL/kg/48 hours) | 1.006 | 1.005 to 1.007 | <0.001 | 1.002 | 1.0008 to 1.0031 | 0.001 |

| MICU | 1.34 | 1.15 to 1.56 | <0.001 | 1.15 | 0.97 to 1.37 | 0.089 |

| CCU/CSRU | 1.22 | 1.01 to 1.47 | 0.032 | 1.03 | 0.84 to 1.26 | 0.752 |

The mean variance inflation factor was 2.89, and p value of goodness of fit was 0.632.

CCU, coronary care unit; CSRU, cardiac surgery care unit; MICU, multiple intensive care unit; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Table 3.

Association between three PLR levels and hospital mortality

| PLR ≤150 | 150<PLR≤250 | PLR >250 | ||||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Model 1 | 1.41 (1.19 to 1.67) | <0.001 | Ref. | – | 1.28 (1.09 to 1.51) | 0.002 |

| Model 2 | 1.34 (1.13 to 1.59) | 0.001 | Ref. | – | 1.23 (1.05 to 1.45) | 0.009 |

| Model 3 | 1.35 (1.14 to 1.61) | 0.001 | Ref. | – | 1.21 (1.03 to 1.43) | 0.018 |

| Model 4 | 1.15 (0.96 to 1.38) | 0.123 | Ref. | – | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.53) | 0.003 |

Adjusted covariates: model 1=age, admitted ICU type. Model 2=model 1+(fluid balance at 48 hours after ICU admission). Model 3=model 2+(infection sites). Model 4=model 3+(maximum SOFA score during ICU stay).

The mean variance inflation factor was 2.53, and p value of goodness of fit was 0.665 for model 4.

ICU, intensive care unit; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; Ref reference category; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

bmjopen-2018-022896supp001.pdf (231.6KB, pdf)

Subgroup analysis

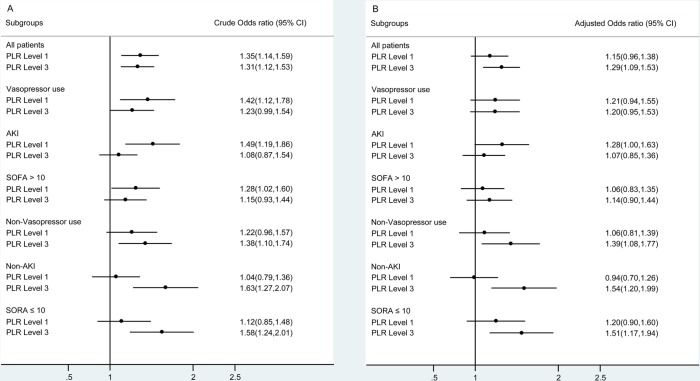

As the association between PLR and mortality was largely confounded by the SOFA score (table 3), we suspected that there was an interaction effect between disease severity and PLR level. Thus, we performed a subgroup analysis according to the existence of vasopressor use and AKI, and the median SOFA score (>10 points), as shown in figure 1. Unlike previous findings, the association between high PLRs and mortality became non-significant in the subgroups with vasopressor use (OR 1.20; 95% CI 0.95 to 1.53), AKI (OR 1.07; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.36) and a SOFA score >10 (OR 1.14; 95% CI 0.90 to 1.44) and remained significant in the subgroups without vasopressor use (OR 1.39; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.77) and AKI (OR 1.54; 95% CI 1.20 to 1.99), and with a SOFA score ≤10 (OR 1.51; 95% CI 1.17 to 1.94). In the case of lower PLRs, the OR of mortality was non-significant in all the subgroups, after adjustment, except for the subgroup with AKI. Data on the comparisons of the characteristics between these subgroups are listed in online supplementary table S2. Finally, all the potential risk factors associated with in-hospital mortality were listed in online supplementary table S3.

Figure 1.

The crude and adjusted ORs in the subgroup analysis. PLR level 2 was used as the reference level in all the logistic models. AKI, acute kidney injury; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Discussion

In this study, we observed a crude U-shaped association between the PLR and hospital mortality in patients with sepsis. However, after adjustment for the disease severity score, only high PLRs remained significantly associated with increased mortality; the association with low PLRs became non-significant. Furthermore, in the subgroup analysis, a significant association between high PLRs and mortality only existed in the subgroups without vasopressor use and AKI, or those with a SOFA score ≤10.

Growing evidence indicates that immune dysregulation (especially cellular immunity), including proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory responses during different stages, is common in cases of sepsis.20 Recently, studies have reported that platelets play an important role in both the immunomodulatory and inflammatory process,21 22 by inducing the release of inflammatory cytokines23 and interacting with different kinds of bacteria and immune cells, including neutrophils, T-lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells and macrophages, which contribute to the initiation or exacerbation of the inflammatory process.24 Low lymphocyte counts, which to a certain degree represent a suppressed immune and inflammatory response,25 26 have also been reported to be associated with inflammatory diseases, such as cardiovascular disease27 and type 2 diabetes.28

Based on these findings, the PLR was suggested as being a novel systematic inflammatory indicator,29 and its use was initially reported in the prognostic prediction of neoplastic disorders, such as hepatocellular carcinoma and breast cancer. Accumulating evidence suggests that elevated PLRs are strongly associated with increased systemic inflammation, which may contribute to the progression and prognoses of many disorders, such as atherosclerosis30 and diabetes mellitus.31

In contrast to our findings, Zheng et al 10 reported that both high and low PLRs are associated with increased mortality, among critically ill patients with AKI, after adjustment for the disease severity score in the Cox proportional hazards models. In that study, unlike in ours, a significant association was also observed in patients with vasopressin use. Several factors may contribute to this inconsistency between the findings, such as the use of different cohorts, PLR knots and definitions of vasopressor use. It is worth noting that, as the association between PLRs and outcomes varies greatly between different cohorts, the interheterogeneity within critically ill patients may also lead to a biased conclusion.

Akbas et al indicated that a high PLR was positively associated with increased epicardial adipose tissue deposition in diabetes patients32; this may be caused by higher inflammation rates. Wang et al 33 reviewed 134 patients with lung adenosquamous cancer and reported that high PLRs (>150) were independently associated with shorter disease-free days and lower overall survival rates. Another study,34 including 270 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, found that elevated PLRs (above 220) were predictors of poor prognoses, while low PLRs (<248.0) were associated with a lower tumour, node and metastasis stage, and low surgery incidence, in 695 patients with lung cancer.35 Despite the fact that the study cohorts used in those studies were quite different from those used in ours, the reported PLR knots were quite similar to ours. However, the small sample sizes in those studies limited the statistical power for further stratification and subgroup analysis of low PLR. In the current study, we noticed that high PLRs (>250) were associated with increased hospital mortality. As higher platelet levels, to a certain extent, are prognostic of inflammation of a higher severity and low lymphocyte counts may represent a suppressed immune and inflammatory response,25 26 an increase in the PLR may reflect the degree of the inflammatory and immune response to the infection, which is related to a poor prognosis.

We also detected a non-significant association between low PLRs and mortality, in the case of sepsis. The association between low PLRs and outcomes was also reported in several studies. In a retrospective study36 including 899 cases of laryngeal cancer, patients were divided into three PLR categories (low (≤119.55), moderate (>119.55 and ≤193.55) and high (>193.55)), and only patients with high PLRs experienced poor outcomes, including malnutrition and more advanced cancer stage; the association between outcomes and PLR levels were non-significant for those with low PLRs. Despite the cohort of that study being different from ours, the conclusion was consistent with that of our study. In the case of sepsis, a low platelet count is potentially associated with poor outcomes. In a large study including 931 patients with sepsis, Claushuis et al reported that patients with a low platelet count at ICU admission had a higher disease severity score and increased mortality risk.37 Furthermore, thrombocytopenia—one of the most common hemostatic disorders in the case of sepsis—which is related with platelet consumption, was also associated with higher mortality.38 However, in the present study, a significant association between low PLR and mortality was not detected. Further studies are needed to validate this conclusion.

Furthermore, according to the subgroup analysis, the association between high PLR and mortality became non-significant in the subgroups with vasopressor use, AKI or a SOFA score >10; this association remained significant in the other subgroups. This finding further supported our speculation that there may be an interaction between PLR and disease severity. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to report this interaction. However, the underlying mechanism of this interaction remains largely unknown. A critical characteristic of sepsis is fluid resuscitation and, in the current study, patients with vasopressor use, AKI or a SOFA score >10, to a certain degree, represented patients with inflammation of a higher severity, and they may have a stronger need for fluid resuscitation. We also noticed that the fluid balance within 48 hours after ICU admission was significantly larger in these subgroups. It needs to be further investigated if fluid resuscitation affects the prognostic value of the PLR.

One of the strengths of our study is the large sample size, which enabled us to adjust for confounding factors and perform subgroup analyses. However, there are also several limitations to our study. First, the MIMIC III database comprises data on patients from 2001; since then, the guidelines for sepsis have changed significantly. The most recent definition of Sepsis 3.0 was used in the current study, and this may have introduced selection bias despite the fact that most of the basic interventions (use of fluids, vasopressors and antimicrobial agents) remained the same. Furthermore, as a decrease in the platelet count was a part of the SOFA score, using the definition of Sepsis 3.0, to a certain degree, may lead to a relatively low mean platelet count and potential multicollinearity. This bias cannot be fully avoided. However, the potential multicollinearity was verified in all the logistic models. Second, the platelet count can be affected by many cofounders, such as kinds of malignancies, immunological factors and kinds of drugs. However, due to the nature of retrospective study, these situations cannot be identified in this database. In addition, in the logistic model using PLR as a continuous variable (table 2), the OR was relatively small, despite the wide PLR range. Caution is therefore needed when interpreting these findings. Third, septic shock is a special subgroup of sepsis. However, patients with septic shock could not be distinguished in this study. Thus, patients were divided into subgroups, according to the existence of vasopressor use, AKI or a SOFA score >10 which, to a certain extent, indicates the presence of an inflammatory response of a higher severity. Fourth, one of the main hypotheses of our study was the interaction effect between disease severity and PLR; yet, this interaction term was not introduced in the logistic model due to the U-shaped association between PLR and mortality. Further prospective studies are needed to verify our hypothesis. Finally, as high PLRs are associated with poor outcomes in various disorders, while low PLRs are not, it is not clear if interventions aimed at changing the PLR value may improve outcomes.

Conclusion

In patients with sepsis, a high PLR was significantly associated with poor survival, while the association was non-significant for those with a low PLR. However, the former association became non-significant in patients with more severe conditions, including those with vasopressor use, AKI or a SOFA score >10. Future studies are needed to verify our hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

YS and XH contributed equally.

Contributors: YS: responsible for data extraction and writing of the manuscript. XH: responsible for data analysis. WZ: responsible for data validation.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: All the data presented in this study were extracted from an online database named ‘MIMIC III’, which was approved by the review boards of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. Thus, requirement for individual patient consent was waived because the study did not impact clinical care, and all protected health information was deidentified.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The full data set used in this study is available from the corresponding author at snow.shen@hotmail.com. However, reanalysis of the full data for other use requires approval by the MIMIC III Institute.

References

- 1. Vincent JL. Emerging therapies for the treatment of sepsis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2015;28:411–6. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cohen J, Vincent JL, Adhikari NK, et al. Sepsis: a roadmap for future research. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:581–614. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70112-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013;369:840–51. 10.1056/NEJMra1208623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peake SL, Delaney A, Bailey M, et al. Goal-directed resuscitation for patients with early septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1496–506. 10.1056/NEJMoa1404380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care 2010;14:R15 10.1186/cc8872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vincent JL, Pereira AJ, Gleeson J, et al. Early management of sepsis. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2014;1:3–7. 10.15441/ceem.14.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hwang YJ, Chung SP, Park YS, et al. Newly designed delta neutrophil index-to-serum albumin ratio prognosis of early mortality in severe sepsis. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:1577–82. 10.1016/j.ajem.2015.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kutlucan L, Kutlucan A, Basaran B, et al. The predictive effect of initial complete blood count of intensive care unit patients on mortality, length of hospitalization, and nosocomial infections. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2016;20:1467–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hudzik B, Szkodziński J, Korzonek-Szlacheta I, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts contrast-induced acute kidney injury in diabetic patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Biomark Med 2017;11:847–56. 10.2217/bmm-2017-0120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zheng CF, Liu WY, Zeng FF, et al. Prognostic value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. Crit Care 2017;21:238 10.1186/s13054-017-1821-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng J, Cai J, Li H, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio as prognostic predictors for hepatocellular carcinoma patients with various treatments: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Cell Physiol Biochem 2017;44:967–81. 10.1159/000485396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Toda M, Tsukioka T, Izumi N, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts the prognosis of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with surgery and postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Thorac Cancer 2018;9:112–9. 10.1111/1759-7714.12547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson AE, Pollard TJ, Shen L, et al. MIMIC-III, a freely accessible critical care database. Sci Data 2016;3:160035 10.1038/sdata.2016.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016;315:801–10. 10.1001/jama.2016.0287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kellum JA, Lameire N. Diagnosis, evaluation, and management of acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 1). Crit Care 2013;17:204 10.1186/cc11454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lameire N, Kellum JA. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and renal support for acute kidney injury: a KDIGO summary (Part 2). Crit Care 2013;17:205 10.1186/cc11455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Závada J, Hoste E, Cartin-Ceba R, et al. A comparison of three methods to estimate baseline creatinine for RIFLE classification. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010;25:3911–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfp766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mickey RM, Greenland S. The impact of confounder selection criteria on effect estimation. Am J Epidemiol 1989;129:125–37. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhang Z, Lu B, Ni H, et al. Prediction of pulmonary edema by plasma protein levels in patients with sepsis. J Crit Care 2012;27:623–9. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, et al. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA 2011;306:2594–605. 10.1001/jama.2011.1829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cho SY, Jeon YL, Kim W, et al. Mean platelet volume and mean platelet volume/platelet count ratio in infective endocarditis. Platelets 2014;25:559–61. 10.3109/09537104.2013.857394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Azab B, Shah N, Akerman M, et al. Value of platelet/lymphocyte ratio as a predictor of all-cause mortality after non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2012;34:326–34. 10.1007/s11239-012-0718-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nording HM, Seizer P, Langer HF. Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. Front Immunol 2015;6:98 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim CH, Kim SJ, Lee MJ, et al. An increase in mean platelet volume from baseline is associated with mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. PLoS One 2015;10:e0119437 10.1371/journal.pone.0119437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Manzoli TF, Delgado AF, Troster EJ, et al. Lymphocyte count as a sign of immunoparalysis and its correlation with nutritional status in pediatric intensive care patients with sepsis: A pilot study. Clinics 2016;71:644–9. 10.6061/clinics/2016(11)05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Felmet KA, Hall MW, Clark RS, et al. Prolonged lymphopenia, lymphoid depletion, and hypoprolactinemia in children with nosocomial sepsis and multiple organ failure. J Immunol 2005;174:3765–72. 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Núñez J, Miñana G, Bodí V, et al. Low lymphocyte count and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Med Chem 2011;18:3226–33. 10.2174/092986711796391633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Otton R, Soriano FG, Verlengia R, et al. Diabetes induces apoptosis in lymphocytes. J Endocrinol 2004;182:145–56. 10.1677/joe.0.1820145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Akboga MK, Canpolat U, Yayla C, et al. Association of platelet to lymphocyte ratio with inflammation and severity of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Angiology 2016;67:89–95. 10.1177/0003319715583186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gary T, Pichler M, Belaj K, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio: a novel marker for critical limb ischemia in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. PLoS One 2013;8:e67688 10.1371/journal.pone.0067688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mertoglu C, Gunay M. Neutrophil-Lymphocyte ratio and Platelet-Lymphocyte ratio as useful predictive markers of prediabetes and diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2017;11:S127–S131. 10.1016/j.dsx.2016.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Akbas EM, Hamur H, Demirtas L, et al. Predictors of epicardial adipose tissue in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol Metab Syndr 2014;6:55 10.1186/1758-5996-6-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang YQ, Zhi QJ, Wang XY, et al. Prognostic value of combined platelet, fibrinogen, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio in patients with lung adenosquamous cancer. Oncol Lett 2017;14:4331–8. 10.3892/ol.2017.6660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang Y, Attar BM, Fuentes HE, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic value of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Oncol 2017;8:1065–71. 10.21037/jgo.2017.09.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang L, Liang D, Xu X, et al. The prognostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte and platelet to lymphocyte ratios for patients with lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2017;14:6449–56. 10.3892/ol.2017.7047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mao Y, Fu Y, Gao Y, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts long-term survival in laryngeal cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2018;275 10.1007/s00405-017-4849-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Claushuis TA, van Vught LA, Scicluna BP, et al. Thrombocytopenia is associated with a dysregulated host response in critically ill sepsis patients. Blood 2016;127:3062–72. 10.1182/blood-2015-11-680744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Semeraro F, Colucci M, Caironi P, et al. Platelet drop and fibrinolytic shutdown in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 2018;46:e221-e228 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022896supp001.pdf (231.6KB, pdf)