Abstract

Introduction

An interrupted time series (ITS) design is an important observational design used to examine the effects of an intervention or exposure. This design has particular utility in public health where it may be impracticable or infeasible to use a randomised trial to evaluate health system-wide policies, or examine the impact of exposures (such as earthquakes). There have been relatively few studies examining the design characteristics and statistical methods used to analyse ITS designs. Further, there is a lack of guidance to inform the design and analysis of ITS studies.

This is the first study in a larger project that aims to provide tools and guidance for researchers in the design and analysis of ITS studies. The objectives of this study are to (1) examine and report the design characteristics and statistical methods used in a random sample of contemporary ITS studies examining public health interventions or exposures that impact on health-related outcomes, and (2) create a repository of time series data extracted from ITS studies. Results from this study will inform the remainder of the project which will investigate the performance of a range of commonly used statistical methods, and create a repository of input parameters required for sample size calculation.

Methods and analysis

We will collate 200 ITS studies evaluating public health interventions or the impact of exposures. ITS studies will be identified from a search of the bibliometric database PubMed between the years 2013 and 2017, combined with stratified random sampling. From eligible studies, we will extract study characteristics, details of the statistical models and estimation methods, effect metrics and parameter estimates. Further, we will extract the time series data when available. We will use systematic review methods in the screening, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and extraction of data. Descriptive statistics will be used to summarise the data.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required since information will only be extracted from published studies. Dissemination of the results will be through peer-reviewed publications and presentations at conferences. A repository of data extracted from the published ITS studies will be made publicly available.

Keywords: interrupted time series, segmented regression, public health, statistical methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, this will be the first study specifically examining the use of the interrupted time series (ITS) design in a representative sample of studies in public health.

A priori systematic review methods will be used in the screening, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction.

A wide range of items capturing the design characteristics, statistical methods and parameter estimates will be extracted and summarised, and a repository of time series data will be created.

For some items, the sample size may not be large enough to precisely estimate the percentage of ITS studies with a particular element.

Our search strategy is unlikely to locate all published ITS studies in public health, since studies will use terminology other than our search terms. Further, we will only search a single database (ie, PubMed); however, this database has the broadest coverage of public health and health services research journals.

Introduction

Background

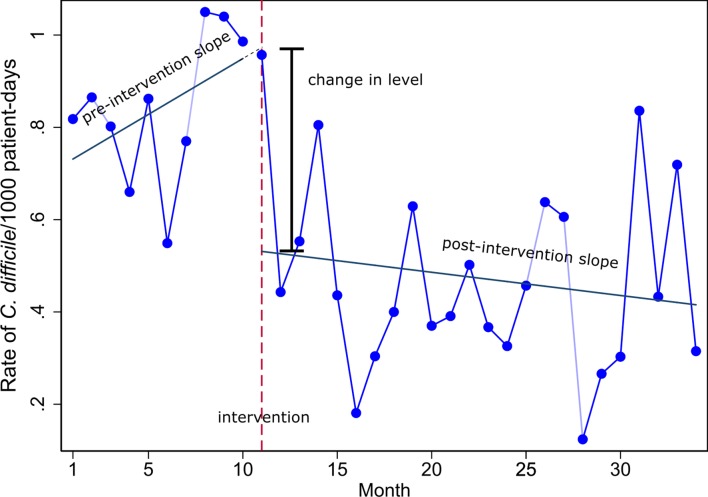

An interrupted time series (ITS) design is one in which data are measured at multiple time points before and after the introduction of an intervention (or an exposure) to examine the effect of the intervention (or exposure). This ‘quasi-experimental’ design is superior to many other observational study designs such as before and after designs in that it avoids threats to internal validity such as short-term fluctuations, secular trends and regression to the mean. ITS designs are used to examine the effects of public health system-wide policy interventions (eg, mass media campaigns1 2) where it is impracticable or infeasible to use a randomised trial. In addition, they can be used to evaluate the effects of policies/interventions retrospectively using administrative databases.3 4 Or, they can be used to examine the impact of exposures such as earthquakes (eg,5 6) or nuclear power station leaks (eg,7). An important benefit of an ITS design is that it can account for the preintervention trend in estimating the effect of the intervention.8 Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of a simple ITS design, with data collected in preintervention and postintervention phases.

Figure 1.

The rate of Clostridium difficile infections (per 1000 patient days) prebleach and postbleach disinfection per month.28 Various effect estimates can be constructed from the preintervention and postintervention slopes, such as the change in level and change in slopes.

A feature of data collected over time is that the data points tend to be correlated. This is known as autocorrelation or serial correlation.9 10 This association could be positive (whereby data points close together in time are more similar than data points further apart) or negative (whereby data points close together are more dissimilar than data points further apart). A specific type of autocorrelation that may be observed in ITS designs with data collected over a long period of time is seasonality, which refers to periodic, repetitive and predictable patterns in the levels of the time series. Influenza rates, for example, may demonstrate patterns of higher levels in winter and lower levels in summer months, recurring every calendar year. Some methods that are used to analyse ITS studies, such as classical linear regression, assume that the observations are independent. If positive autocorrelation is present and not accounted for, this may lead to standard errors that are too small, with resulting confidence intervals that are too narrow and p values that are too small.10 Autocorrelation is also one of the key parameters required for sample size estimation.11

In addition to accounting for autocorrelation, other important aspects of analysing ITS data include specification of the structure of the model (ie, number of segments and their shape12), statistical estimation methods and choice of effect metrics. Regarding the latter, even in the circumstance where a simple segmented linear model is fitted (figure 1), a variety of effect metrics may be calculated. The effect of the intervention on the outcome can be calculated by estimating the change in level, or the change in slope of the preintervention and postintervention trends, or both (see figure 1). A combination of the two allows estimation of the intervention effect at a specified time post intervention based on the predicted counterfactual (ie, using the trend in the preintervention period to predict what would have occurred in the postintervention period, in the absence of the intervention). Further, these effect metrics can be expressed in absolute or relative terms with associated confidence intervals. For example, a level change corresponding to a drop in mortality could be expressed as an absolute effect such as number of deaths or as a relative effect such as percentage change in the number of deaths.13 Choosing which metric is most helpful for understanding and communicating the impact of an intervention is not straightforward.14

There have been relatively few studies examining the design characteristics and statistical methods used to analyse ITS designs. Ramsay et al 15 examined ITS studies included in two systematic reviews and demonstrated that when reanalysed using more appropriate statistical methods, approximately half of the studies that had found statistically significant intervention effects, had their results overturned (ie, statistically significant results became non-significant). Jandoc et al 16 examined a cohort of 220 ITS studies, published from 1984 to 2013, in drug utilisation research and found that important elements of an ITS design were not being accounted for in the analyses, such as taking into account autocorrelation and seasonality. Ewusie et al 17 are undertaking a scoping review of ITS methods used to analyse health research and the way in which the results are reported, focusing on the strengths and limitations of each method. None of these reviews has focused on ITS studies evaluating public health interventions, or exposures, that impact on health-related outcomes.

There is a lack of available information and guidance to inform the design and analysis of ITS studies. First, there are no databases providing empirical estimates of key parameters (such as autocorrelation coefficients) required for sample size calculation. Second, there is an absence of clear guidance to inform the choice of statistical analysis. Third, the choice of intervention effect estimates and their standard errors that are most robust to misspecification of the model and estimation method is unclear.

This is the first study in a larger project that aims to address these issues by providing tools and guidance for researchers on the design and analysis of ITS studies. The project includes a series of studies that will examine the design features and statistical methods used in practice, investigate the performance of a range of commonly used statistical methods through numerical simulation and empirical evaluation, and create a repository of input parameters required for sample size calculation. Here, we report the planned design of the first study, the objectives of which are to (1) examine and report the design characteristics and statistical methods used in a random sample of contemporary ITS studies examining public health interventions or exposures that impact on health-related outcomes, and (2) create a repository of time series data extracted from ITS studies.

Methods and analysis

Overview

We will identify and describe ITS studies evaluating public health interventions or the impact of exposures. ITS studies will be identified from a search of the bibliometric database PubMed, combined with stratified random sampling. Study selection and data extraction will be undertaken by one author, and for a fraction of studies, two authors. From eligible studies, we will extract study characteristics, details of the statistical models and estimation methods, effect metrics and parameter estimates. Further, we will extract the time series data, when available.

Eligibility criteria

Following are the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to determine which ITS studies will be included.

Inclusion criteria

Our definition of an ITS study is informed by the design features taxonomy for quasi-experimental designs proposed by the Cochrane Non-Randomized Studies Methods Group18 and further developed by Reeves et al.19 ITS studies meeting the following criteria will be included (with rationale and further explanations for each criterion provided below):

There are at least two segments separated by a clearly defined intervention or exposure with at least three points in each segment (eg, preintervention and postintervention time series, each with at least three points).

Observations are collected on a group of individuals (eg, community, hospital) at each time point.

The study is investigating the impact of a public health intervention or exposure that has public health implications (eg, patient health outcome, resource use).

Criterion 1 is that used by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group as minimum criteria for an ITS study to be considered eligible for inclusion in systematic reviews undertaken within this group.20 The rationale for this criterion is that three time points pre interruption and post interruption allow the possibility of using segmented time series regression (although using as few as three points would not be recommended11).

Criterion 2 restricts the inclusion to ITS studies focused on examining the effects of public health interventions (or exposures) on populations, and importantly, excludes ITS studies that examine the effects of an intervention on individuals (also known as single-case designs21 or single-case experimental designs22). The group of individuals studied at each time point may or may not include the same individuals. The study may also include multiple series (multiple intervention and control series measured in aggregate or groups (eg, hospitals, communities)).

Our definition of public health interventions (criterion 3) is informed by that used by the Cochrane Public Health Review Group,23 and includes interventions that aim to prevent or promote population health for communicable and non-communicable diseases (eg, vaccination and screening programmes; programmes aimed to reduce the use of tobacco or alcohol; public information/awareness campaigns for stroke recognition). The interventions may fall outside of the health service (such as education, work environment, housing and the built environment, natural environment interventions), but will be included if they aim to improve population health-related outcomes. Further, there will be no restriction on the level that the intervention is targeted at, which may be, for example, individuals, communities or health systems. Our definition of exposures are events that are not under investigators’ control (eg, earthquakes, financial crises, tsunamis, environmental chemicals).

Exclusion criteria

ITS studies meeting the following criteria will be excluded:

Studies written in a language other than English.

Single-case designs.

Methodological papers examining ITS studies.

Criterion 1 is included as we are not able to translate studies written in languages other than English due to resource constraints. Criterion 3 excludes papers that examine statistical methods for ITS studies. While these methodological papers often include motivating examples, which demonstrate the application of different methods to an ITS study selected from the literature, these examples may not be representative of published ITS studies.

Sample size

We plan to include 200 ITS studies, which will allow estimation of the percentage of ITS studies with a particular element (eg, studies taking autocorrelation into account) to within a maximum margin of error of 7% (assuming a prevalence of 50%); for a prevalence less (or greater) than 50%, the margin of error will be smaller. We will include 200 studies from 2013 to 2017. The studies will be stratified by year, and within each year, will be randomly sampled until 40 are identified that meet the eligibility criteria. If fewer than 40 studies are eligible for inclusion in any given year, we will randomly sample studies from earlier years until we meet our target sample size. We are sampling (using standard survey methodology) since this provides a valid approach for estimating the prevalence of characteristics of ITS studies. This is unlike systematic reviews that aim to estimate a combined treatment effect, for which it is imperative to identify all studies.

Search methods for the identification of studies

To identify potentially eligible ITS studies, we will search PubMed. PubMed has been chosen since it has the broadest coverage of public health and health services research journals, and as such, provides a sufficient sampling frame. We will search using free-text terms informed from previous search strategies developed to identify ITS studies,16 17 terms used to describe the ITS design in the methods section of previously published papers (eg, Cheng et al,2 Baker and Alonso,3 Milojevic et al 5), and controlled vocabulary (Medical Subject Headings (MESH) terms) (table 1). In developing the strategy, we examined how well it captured a subset (10% random sample, 31 studies) of ITS studies included in two systematic reviews15 16 and refined accordingly. Studies not captured by our preliminary search strategy were investigated to identify additional search terms. After adding the new search terms, the process was repeated until all studies in the sample were captured. The strategy was not restricted by public health terms since we anticipated that there may be large variation in the terminology used.

Table 1.

PubMed search strategy

| Search (#) | Search terms |

| 1 | Interrupted time series analysis (MeSH term) |

| 2 | “Interrupted time series” (title/abstract) |

| 3 | “Change point” (title/abstract) |

| 4 | “Segmented regression” (title/abstract) |

| 5 | “Segmented linear regression” (title/abstract) |

| 6 | “Repeated measures study” (title/abstract) |

| 7 | “Piecewise regression” (title/abstract) |

| 8 | “Time-series intervention” (title/abstract) |

| 9 | “Phase design” (title/abstract) |

| 10 | “Multiple baseline” (title/abstract) |

| 11 | “ARIMA” (title/abstract) |

| 12 | “Integrated moving average” (title/abstract) |

| 13 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 |

ARIMA, autoregressive integrated moving average.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts will be extracted into a screening and data collection programme built using Microsoft Access. Abstracts will be grouped by year of publication, and randomly sorted. In the piloting phase, four authors (SLT, JEM, ABF and AK) will independently assess 50 abstracts to ensure consistency of the application of the inclusion criteria.

Following piloting, two authors (SLT and one of JEM, ABF or AK) will use a two-phase screening process to identify ITS studies. One author (SLT) will screen all abstracts, and a second author will screen a 50% sample of the identified abstracts or until 20 ITS studies (per year) have been identified for inclusion (AK, JEM, ABF). In the first phase, abstracts which are independently assessed by both reviewers as not meeting at least one of the following criteria, will be excluded.

Does the study appear to use an ITS design?

Were observations collected from a group of individuals?

Is this study written in English?

Does the study appear to evaluate the impact of a public health intervention or natural interruption?

In the second phase, the full text of each study will be retrieved and assessed against the criteria listed below. Studies that are found to meet these criteria will be included.

Does the study use an ITS design?

Were observations collected from a group of individuals?

Are there are at least two segments separated by a clearly defined intervention with at least three points in each segment?

Selection of outcome(s) for inclusion

Multiple outcomes per ITS study are potentially eligible for inclusion. Within each outcome type category (binary, continuous, count), we will select one outcome using the following hierarchy:

ITS data availability—outcomes with data available to be extracted (either from tables or figures) will be selected ahead of those without data.

Stated primary outcome (or reported in the title or objectives).

First reported result outcome in the abstract.

First reported outcome in the results.

Uncertainty in the selection of the review outcomes will be discussed among the review team.

Data extraction and management

The data extraction process will initially be piloted by four reviewers (SLT, JEM, ABF and AK) on a sample of 10 ITS studies to ensure consistency of data extraction and will be adjusted as necessary. Following piloting, we will use double data extraction for all items (except extraction of the time series data) on a randomly selected 20% of studies. Discrepancies and uncertainty in coding will be discussed in meetings with three reviewers. For any items where we observe a high degree of inconsistency, we will undertake double data extraction for these items on a further randomly selected sample of studies.

We will extract data pertaining to the study characteristics, design, outcome, model, statistical methods and effect measures. Further details are provided in table 2, with the complete list of items available in online supplementary additional file 1.

Table 2.

Example data extraction items

| Examples of data extraction items | |

| Study characteristics | Author name; year of publication; rationale for using an ITS design; type and description of the intervention. |

| Design | Time interval (eg, monthly); total number of observations; total number of time intervals and number of segments; number of time intervals per segment; average number of observations per time interval; and whether there is a comparison group. |

| Outcome | Description (eg, vehicle occupant injury) and classification (eg, count) of the outcome at the individual observation level; description of the aggregate level outcome (eg, rate per population of motor vehicle occupant injuries). |

| Model | Model shape (eg, level change or slope change, or both, and whether this shape is prespecified or not); number of segments; model type (eg, autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), segmented regression, other regression, pre–post); modelling approach for any transition period; and, if there was a comparison group, how it was incorporated in the analysis. |

| Statistical methods | Statistical estimation method (eg, logistic, Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, generalised estimating equation (GEE); whether autocorrelation, seasonality and outliers were investigated; and, how they were handled in the analysis; whether and how non-stationarity was tested for. |

| Effect measures | Reported effect measures (eg, change in level, change in slope); whether an absolute or relative measure; effect estimates and statistics associated with the effect measure (eg, p values, CIs); details on any forecasting (eg, projecting from one segment to a specified time point in another segment) and whether there was mention of any ceiling or floor effects. |

ITS, interrupted time series.

bmjopen-2018-024096supp001.pdf (96.7KB, pdf)

The time series data for each included outcome will be extracted when possible. For studies that present their data in graphical form only, we will extract from graphs using WebPlotDigitizer software24. This software has been shown to give reliable and valid results.25 The data will be kept in a Microsoft Access 2016 database26 on a secure server. Any free text responses will be input as prespecified options or categories wherever possible.

Analysis

We will calculate descriptive summary statistics. For categorical data, such as the type of model used, we will present percentages and frequencies. For counts, such as the number of time intervals, we will present means (with standard deviations) and medians (with interquartile range). Statistical analyses will be undertaken in Stata Release 1527. The data sets arising from this study will be made available on figshare.

Patient and public involvement

No patients will be involved in this project and information will only be extracted from published studies.

Discussion

This is a first study in a larger project that aims to provide tools and guidance for researchers in the design and analysis of ITS studies. This study will provide information on design characteristics of a contemporary sample of ITS studies in public health, statistical methods used in practice, and provide a repository of ITS data. Results from this study will underpin the remainder of the project by informing a numerical simulation study to investigate the performance of commonly used statistical methods; an empirical study to investigate the impact of using different statistical methods for analysing ITS on real data; and a study to create a repository of parameter values for sample size calculation, along with generalisable ‘rules of thumb’ on the selection of values.

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths to our study. To our knowledge, this will be the first study specifically examining the use of ITS studies in public health. Further, a priori specified systematic review methods will be used in the screening, application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and data extraction.

However, there are some limitations. For some items, the sample size may not be large enough to precisely estimate the percentage of ITS studies with a particular element. Our search strategy is unlikely to locate all published ITS studies in public health, since studies will use terminology other than our search terms. Further, we will only search a single database (ie, PubMed); however, this database has the broadest coverage of public health and health services research journals.

Implications of this research

Previous reviews have described the details of ITS studies including whether autocorrelation, seasonality and/or stationarity were accounted for.15 16 However, these studies have focused on specific systematic reviews or drug utilisation studies. Our study will extend this research, with a focus on ITS studies in public health. Results of this study will inform the larger project, which aims to provide tools and guidance for researchers designing and analysing ITS studies. The repository of ITS data that we will curate as part of this project will also be of value for future methodological and statistical research.

Conclusion

ITS studies are commonly used designs in public health to examine whether an intervention or an exposure has had an effect on health outcomes. However, there is a lack of available information and guidance to inform the design and analysis of ITS studies. Results of this study will help to address this gap by providing information on current design and analysis practice of ITS studies in public health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work forms part of SLT’s PhD, which is supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award administered through Monash University, Australia.

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: JEM conceived the study and all authors contributed to its design. SLT wrote the first draft of the manuscript, with contributions from JEM and AK. All authors contributed to revisions of the manuscript and take public responsibility for its content.

Funding: SLT was funded through an Australian Postgraduate Award administered through Monash University, Australia. This project is funded by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) project grant (1145273). JEM is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1143429). ACC is supported by an NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1068732). JMG holds a Canada Research Chair in Health Knowledge Uptake and Transfer. The funders had no role in study design, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Flynn D, Ford GA, Rodgers H, et al. A time series evaluation of the FAST National Stroke Awareness Campaign in England. PLoS One 2014;9:e104289 10.1371/journal.pone.0104289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheng J, Benassi P, De Oliveira C, et al. Impact of a mass media mental health campaign on psychiatric emergency department visits. Can J Public Health 2016;107:303–e11. 10.17269/cjph.107.5265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Baker JM, Alonso WJ. Rotavirus vaccination takes seasonal signature of childhood diarrhea back to pre-sanitation era in Brazil. J Infect 2018;76:68–77. 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Leyland AH, Ouedraogo S, Nam J, et al. Public Health Research. Evaluation of Health in Pregnancy grants in Scotland: a natural experiment using routine data. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Milojevic A, Armstrong B, Hashizume M, et al. Health effects of flooding in rural Bangladesh. Epidemiology 2012;23:107–15. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31823ac606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Runkle JD, Zhang H, Karmaus W, et al. Prediction of unmet primary care needs for the medically vulnerable post-disaster: an interrupted time-series analysis of health system responses. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2012;9:3384–97. 10.3390/ijerph9103384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scherb HH, Mori K, Hayashi K. Increases in perinatal mortality in prefectures contaminated by the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident in Japan: a spatially stratified longitudinal study. Medicine 2016;95:e4958 10.1097/MD.0000000000004958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, et al. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther 2002;27:299–309. 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gebski V, Ellingson K, Edwards J, et al. Modelling interrupted time series to evaluate prevention and control of infection in healthcare. Epidemiol Infect 2012;140:2131–41. 10.1017/S0950268812000179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huitema BE, McKean JW. Identifying autocorrelation generated by various error processes in interrupted time-series regression designs. Educ Psychol Meas 2007;67:447–59. 10.1177/0013164406294774 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:1252–61. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barnett AG, Page K, Campbell M, et al. Changes in healthcare-associated Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections after the introduction of a national hand hygiene initiative. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:1029–36. 10.1086/677160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, et al. Methods for estimating confidence intervals in interrupted time series analyses of health interventions. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:143–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huitema BE, Mckean JW. Design specification issues in time-series intervention models. Educ Psychol Meas 2000;60:38–58. 10.1177/00131640021970358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ramsay CR, Matowe L, Grilli R, et al. Interrupted time series designs in health technology assessment: lessons from two systematic reviews of behavior change strategies. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2003;19:613–23. 10.1017/S0266462303000576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jandoc R, Burden AM, Mamdani M, et al. Interrupted time series analysis in drug utilization research is increasing: systematic review and recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol 2015;68:950–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ewusie JE, Blondal E, Soobiah C, et al. Methods, applications, interpretations and challenges of interrupted time series (ITS) data: protocol for a scoping review. BMJ Open 2017. 7:e016018 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reeves BC DJ, Higgins JPT, Wells GA. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 5.1.0 edn: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Reeves BC, Wells GA, Waddington H. Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: a checklist for classifying studies evaluating the effects on health interventions-a taxonomy without labels. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;89:30–42. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.02.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. EPOC. Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC). EPOC Resources for review authors. 2017. epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-resources-review-authors.

- 21. Huitema BE. The analysis of covariance and alternatives: statistical methods for experiments, quasi-experiments, and single-case studies. 2nd ed Hoboken, N.J: Wiley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shamseer L, Sampson M, Bukutu C, et al. CENT group. CONSORT extension for reporting N-of-1 trials (CENT) 2015: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;76(Supplement C):18–46. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cochrane. About Cochrane Public Health (CPH). 2018. http://ph.cochrane.org/about-cochrane-public-health-cph (accessed May 2018).

- 24. WebPlotDigitizer [program]. 4.1 version. Austin, Texas, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moeyaert M, Maggin D, Verkuilen J. Reliability, validity, and usability of data extraction programs for single-case research designs. Behav Modif 2016;40:874–900. 10.1177/0145445516645763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Access [program]. 2016 version: Microsoft, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 [program]. 15 version. Texas: StataCorp LLC, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hacek DM, Ogle AM, Fisher A, et al. Significant impact of terminal room cleaning with bleach on reducing nosocomial Clostridium difficile. Am J Infect Control 2010;38:350–3. 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024096supp001.pdf (96.7KB, pdf)