Abstract

Aims

The role of microRNAs has not been studied in cardiogenic shock. We examined the potential role of miR‐423‐5p level to predict mortality and associations of miR‐423‐5p with prognostic markers in cardiogenic shock.

Methods and results

We conducted a prospective multinational observational study enrolling consecutive cardiogenic shock patients. Blood samples were available for 179 patients at baseline to determine levels of miR‐423‐5p and other biomarkers. Patients were treated according to local practice. Main outcome was 90 day all‐cause mortality. Median miR‐423‐5p level was significantly higher in 90 day non‐survivors [median 0.008 arbitrary units (AU) (interquartile range 0.003–0.017) vs. 0.004 AU (0.002–0.009), P = 0.003]. miR‐423‐5p level above median was associated with higher lactate (median 3.7 vs. 2.4 mmol/L, P = 0.001) and alanine aminotransferase levels (median 68 vs. 35 IU/L, P < 0.001) as well as lower cardiac index (1.8 vs. 2.4, P = 0.04) and estimated glomerular filtration rate (56 vs. 70 mL/min/1.73 m2, P = 0.002). In Cox regression analysis, miR‐423‐5p level above median was associated with 90 day all‐cause mortality independently of established risk factors of cardiogenic shock [adjusted hazard ratio 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.2–3.2), P = 0.01].

Conclusions

In cardiogenic shock patients, above median level of miR‐423‐5p at baseline is associated with markers of hypoperfusion and seems to independently predict 90 day all‐cause mortality.

Keywords: Cardiogenic shock, microRNA, miR‐423‐5p, Acute coronary syndrome, Mortality, Prognosis

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock (CS) is a severe state of inadequate systemic tissue perfusion due to low cardiac output, often resulting in multi‐organ failure.1 In‐hospital mortality is close to 40% even with current treatment.2 More research is needed to understand the mechanisms leading to shock and hypoperfusion and to discover new biomarkers to optimize treatment for each patient.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short non‐coding RNAs that have a central role in regulating gene expression. miRNAs can be detected in plasma, body fluids, and tissues.3 Circulating miRNAs have emerged as potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of cardiovascular disease.4 In previous studies on miRNAs in heart failure, miR‐423‐5p is one of the miRNAs most consistently shown to be associated with the diagnosis and prognosis of heart failure,5, 6, 7, 8 although discrepancies exist.9, 10, 11 Induction of apoptosis by miR‐423‐5p has been shown in cardiomyocytes,12 suggesting that miR‐423‐5p may also have a role in the pathogenesis and progression of heart diseases. Indeed, miR‐423‐5p was reported to be up‐regulated in failing human myocardium.13

Aims

As there are no studies on microRNAs in CS, we chose to examine the potential of miR‐423‐5p level to predict mortality and the possible associations of miR‐423‐5p with prognostic markers in CS.

Materials and methods

This study was part of a predefined biomarker substudy of the CardShock study. The CardShock study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01374867) was a multicenter, prospective, observational study enrolling patients within 6 h of the detection of CS (for details, see Harjola et al.2). The study was approved by the local ethics committees and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was received from all patients or their next of kin. Patients were treated according to local practice, and treatment and procedures were registered. Of the 219 patients recruited for the CardShock study, blood samples were available at baseline for 179 patients (2 centres did not participate in the biomarker substudy), and at 24 h for 142 patients (22 patients died before this time point, and 18 patients had missing samples). Pulmonary artery catheter use was at the discretion of the treating physician and was used in 37 patients to measure the cardiac output using the thermodilution method, from which the cardiac index was calculated.

Blood samples were collected into ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid tubes at study enrolment. Total RNA was extracted from plasma samples, and miR‐423‐5p level was assessed by quantitative PCR using Caenorhabditis elegans miR‐39 for normalization, as previously described.7 Creatinine, high‐sensitivity troponin T (hsTnT) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were analysed at an accredited central laboratory (ISLAB, Kuopio, Finland) using standard kits (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). hsTnT was also measured at 24 h in 142 patients with samples available from both time points. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from creatinine values using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation.14 Arterial blood lactate was analysed locally.

Associations between miR‐423‐5p, other biomarkers, clinical data, and 90 day all‐cause mortality were analysed using SPSS statistical software version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Two‐sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to determine the statistical significance of between‐group differences in miR‐423‐5p levels. Associations between continuous variables with non‐normal distributions were assessed using Spearman correlations. Differences in mortality were assessed by comparing Kaplan–Meier survival curves using the log‐rank test. To test for the independent association of miR‐423‐5p level above median at baseline with 90 day mortality, a multivariable Cox regression model was constructed with 90 day all‐cause mortality as the dependent variable. In the multivariable Cox regression model, adjustments were made for variables included in the CardShock risk score,2 hsTnT, and ALT at baseline. Nested Cox regression models containing (i) CardShock risk score variables or (ii) CardShock risk score variables and miR‐423‐5p level above median were compared using the likelihood ratio test. General linear model was used to analyse the independent predictors of miR‐423‐5p level using miR‐423‐5p as the dependent variable. To normalize the distribution and the residuals, miR‐423‐5p was log transformed for this analysis.

Results

The mean age in the study cohort was 66 years, and 26% were women. Average mean arterial pressure was 57 (SD 11) mmHg. The main aetiology of CS was acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (78%). Non‐ACS causes consisted mainly of worsening chronic heart failure (10%), valvular and other mechanical causes (7%), and myocarditis (2%). The 90 day all‐cause mortality was 42%. miR‐423‐5p level at baseline was two‐fold higher in non‐survivors compared with survivors {median 0.008 arbitrary units (AU) [interquartile range (IQR) 0.003–0.017] vs. 0.004 AU [IQR 0.002–0.009], P = 0.003}. Moreover, patients with miR‐423‐5p level above median had higher levels of lactate and ALT, lower eGFR, and lower cardiac index at baseline than had patients with miR‐423‐5p level below median (Table 1). There was a modest positive correlation between baseline miR‐423‐5p level and lactate [Spearman correlation coefficient (r s) = 0.28, P < 0.001], ALT (r s = 0.38, P < 0.001), and creatinine (r s = 0.19, P = 0.01).

Table 1.

Clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients stratified by miR‐423‐5p level at baseline

| All (n = 179) | miR‐423‐5p below median (n = 90) | miR‐423‐5p above median (n = 89) | P‐value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 66 ± 12 | 66 ± 12 | 66 ± 12 | 0.8 |

| Male, n (%) | 132 (74) | 67 (74) | 65 (73) | 0.9 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg | 57 ± 11 | 56 ± 10 | 57 ± 11 | 0.5 |

| Previous MI or CABG, n (%) | 46 (26) | 23 (26) | 23 (26) | >0.9 |

| Altered mental status at presentation, n (%) | 118 (67) | 57 (64) | 61 (69) | 0.5 |

| ACS aetiology, n (%) | 143 (80) | 69 (77) | 74 (83) | 0.4 |

| LVEF, % | 33 ± 14 | 33 ± 14 | 33 ± 14 | 0.9 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 63 ± 30 | 70 ± 30 | 56 ± 27 | 0.002 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 2.7 (1.7–5.8) | 2.4 (1.4–3.5) | 3.7 (2.0–6.7) | 0.001 |

| ALT, IU/L | 44 (4–54) | 35 (16–66) | 68 (27–133) | <0.001 |

| NT‐pro‐BNP, ng/L | 2710 (586–9434) | 2889 (900–7634) | 2581 (407–10 118) | 0.7 |

| hsTnT, ng/L | 2190 (388–5418) | 1635 (402–5127) | 2565 (366–6870) | 0.3 |

| hsTnT at 24 h, ng/L | 3848 (943–12 756) | 2599 (727–10 310) | 5217 (1575–17 019) | 0.02 |

| Cardiac index,a L/min/m2 | 2.2 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 0.04 |

Results are presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed variables, medians, and interquartile ranges for non‐normally distributed variables and as n (%) for categorical variables. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CI, cardiac index; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hsTnT, high‐sensitivity troponin T; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐pro‐BNP, N‐terminal fragment of pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

n = 37.

To determine independent predictors of miR‐423‐5p level, a general linear model was constructed using miR‐423‐5p as the dependent variable. In this model, independent predictors of miR‐423‐5p level were ACS aetiology (coefficient B = 2.7 for ACS aetiology, P = 0.001), ALT (B = 0.03 for 100 IU/L increase, P = 0.02), and blood lactate at baseline (B = 0.03 for 1 mmol/L increase, P = 0.02). To explore whether miR‐423‐5p level at baseline was associated with the extent of developing myocardial injury, we tested for correlation between miR‐423‐5p and hsTnT at baseline and 24 h. A modest correlation between miR‐423‐5p at baseline and hsTnT at 24 h was found in ACS (r s = 0.27, P = 0.003) but not in non‐ACS patients (r s = −0.04, P = 0.87). No correlation was found between miR‐423‐5p and hsTnT at baseline.

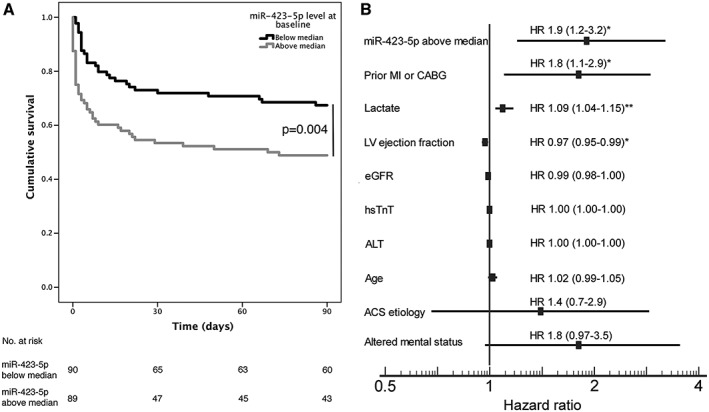

Comparing Kaplan–Meier curves, we found that patients with miR‐423‐5p level above median had higher 90 day all‐cause mortality (Figure 1 A). In Cox regression analysis, miR‐423‐5p level above median was associated with 90 day all‐cause mortality with an unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) of 1.9 (95% confidence interval 1.2–3.1, P = 0.006). Adjusting for the variables included in the CardShock risk score2 (i.e. age, prior myocardial infarction or coronary bypass grafting, altered mental status at presentation, ACS aetiology, left ventricular ejection fraction, lactate, and estimated glomerular filtration fraction), hsTnT, and ALT at baseline, miR‐423‐5p level above median was independently associated with 90 day all‐cause mortality (HR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2‐3.2, P = 0.01, Figure 1 B). Lactate, prior myocardial infarction or coronary bypass grafting, and left ventricular ejection fraction also independently predicted mortality. Comparing nested Cox regression models confirmed that the addition of miR‐423‐5p level above median as a variable to the CardShock risk score model improved the model's predictive power on 90 day all‐cause mortality (χ 2 = 7.2, P = 0.007, for comparison of nested models; c‐index for the Cox model with miR‐423‐5p level above median = 0.790 and without = 0.776).

Figure 1.

(A) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for patients with miR‐423‐5p below (black line) and above (grey line) median at baseline. (B) Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals (in parentheses) of the multivariable model including CardShock risk score variables and other variables associated with miR‐423‐5p level. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; HR, hazard ratio; hsTnT, high‐sensitivity troponin T; LV, left ventricle; MI, myocardial infarction. *P < 0.05 **P = 0.001.

We also explored the association of miR‐423‐5p level with the aetiology of CS. Comparing Kaplan–Meier curves, we found that miR‐423‐5p level above median was associated with higher mortality in both ACS (log‐rank test P = 0.04) and non‐ACS (log‐rank test P = 0.03) patients. Patients with ACS had higher miR‐423‐5p level than had non‐ACS patients [median 0.005 AU (IQR 0.003–0.016) vs. 0.003 AU (IQR 0.001–0.008), P = 0.01].

Conclusions

This is the first study to show an association between levels of a circulating microRNA and mortality in CS. The main findings are as follows. First, above median level of miR‐423‐5p predicted 90 day all‐cause mortality independently of established risk factors of CS. Second, the association of above median level of miR‐423‐5p with 90 day all‐cause mortality was independent of the aetiology of CS. Third, miR‐423‐5p level and correlations with hsTnT at 24 h differed between ACS and non‐ACS patients.

It is interesting to note that miR‐423‐5p behaved differently in ACS and non‐ACS patients. The origin and mechanisms leading to elevated levels of circulating microRNAs are not fully elucidated.15 miR‐423‐5p has been shown to be enriched in the coronary circulation of heart failure patients,16 suggesting a cardiac source. Circulating levels of miR‐423‐5p have also been shown to be elevated early in acute myocardial infarction.17, 18 However, as microRNAs are generally not considered to be very tissue specific, it may be hypothesized that circulating miR‐423‐5p could have other sources as well. As the observed correlations between miR‐423‐5p, lactate, ALT, and creatinine were weak, there are probably other factors affecting the level of miR‐423‐5p as well. Given the association of miR‐423‐5p with low cardiac index and high lactate levels, the possibility that increased miR‐423‐5p levels are a marker of organ hypoperfusion in general and shock from any cause rather than being specifically associated with CS cannot be excluded.

This study has some limitations. The observation that miR‐423‐5p level above median was associated with a lower cardiac index is limited by the small proportion of patients (21%) with pulmonary artery catheters. Invasive haemodynamic monitoring is not routinely advocated,1 and we believe that our cohort reflects current clinical practice. It should be noted that CS is a complex syndrome, and although mortality analyses were adjusted for all relevant variables available, residual confounding may be present. Furthermore, these findings should be interpreted as preliminary and need to be confirmed in another CS population with mixed etiologies.

In conclusion, miR‐423‐5p level above median at baseline is associated with markers of hypoperfusion and seems to predict 90 day mortality independently of established risk factors in CS.

Conflict of Interest

Dr Lassus has served on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim, Medix Biochemica, Novartis, Servier, and Vifor Pharma and received lecture fees from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Novartis, Orion Pharma, and Vifor Pharma. Dr Harjola has served on advisory boards for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, MSD, Novartis, and Roche Diagnostics and received lecture fees from Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Orion Pharma, and Vifor Pharma. No other disclosures were reported.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Finnish Foundation for Cardiovascular Research, Aarne Koskelo Foundation, Finnish Foundation for Laboratory Medicine, Finska Läkaresällskapet, the Liv och Hälsa Foundation, and Finnish state funding for university‐level research. Roche Diagnostics provided kits for the analysis of hsTnT. The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Ms. Katariina Immonen, MSc. The CardShock steering committee: Veli‐Pekka Harjola (chair), Marek Banaszewski, Lars Køber, Johan Lassus, Alexandre Mebazaa, Marco Metra, John Parissis, Jose Silva‐Cardoso, Alessandro Sionis, Salvatore Di Somma, and Jindrich Spinar. List of investigators: in Athens are Katerina Koniari, Astrinos Voumvourakis, and Apostolos Karavidas; in Barcelona are Jordi Sans‐Rosello, Montserrat Vila, and Albert Duran‐Cambra; in Brescia are Marco Metra, Michela Bulgari, and Valentina Lazzarini; in Brno are Jiri Parenica, Roman Stipal, Ondrej Ludka, Marie Palsuva, Eva Ganovska, and Petr Kubena; in Copenhagen are Matias G. Lindholm and Christian Hassager; in Helsinki are Tom Bäcklund, Raija Jurkko, Kristiina Järvinen, Tuomo Nieminen, Kari Pulkki, Leena Soininen, Reijo Sund, Ilkka Tierala, Jukka Tolonen, Marjut Varpula, Tuomas Korva, and Anne Pitkälä; in Rome is Rossella Marino; in Porto are Alexandra Sousa, Carla Sousa, Mariana Paiva, Inês Rangel, Rui Almeida, Teresa Pinho, and Maria Júlia Maciel; and in Warsaw are Janina Stepinska, Anna Skrobisz, and Piotr Góral. The study was performed in collaboration with the GREAT network.

Jäntti, T. , Segersvärd, H. , Tolppanen, H. , Tarvasmäki, T. , Lassus, J. , Devaux, Y. , Vausort, M. , Pulkki, K. , Sionis, A. , Bayes‐Genis, A. , Tikkanen, I. , Lakkisto, P. , and Harjola, V.‐P. (2019) Circulating levels of microRNA 423‐5p are associated with 90 day mortality in cardiogenic shock. ESC Heart Failure, 6: 98–102. 10.1002/ehf2.12377.

References

- 1. van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136: e232–e268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harjola V‐P, Lassus J, Sionis A, Køber L, Tarvasmäki T, Spinar J, Parissis J, Banaszewski M, Silva‐Cardoso J, Carubelli V, Di Somma S, Tolppanen H, Zeymer U, Thiele H, Nieminen MS, Mebazaa A, for the CardShock study investigators and the GREAT network . Clinical picture and risk prediction of short‐term mortality in cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen X, Ba Y, Ma L, Cai X, Yin Y, Wang K, Guo J, Zhang Y, Chen J, Guo X, Li Q, Li X, Wang W, Zhang Y, Wang J, Jiang X, Xiang Y, Xu C, Zheng P, Zhang J, Li R, Zhang H, Shang X, Gong T, Ning G, Wang J, Zen K, Zhang J, Zhang C‐Y. Characterization of microRNAs in serum: a novel class of biomarkers for diagnosis of cancer and other diseases. Cell Res 2008; 18: 997–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vegter EL, van der Meer P, de Windt LJ, Pinto YM, Voors AA. MicroRNAs in heart failure: from biomarker to target for therapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 457–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tijsen AJ, Creemers EE, Moerland PD, de Windt LJ, van der Wal AC, Kok WE, Pinto YM. miR423‐5p as a circulating biomarker for heart failure. Circ Res 2010; 106: 1035–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goren Y, Kushnir M, Zafrir B, Tabak S, Lewis BS, Amir O. Serum levels of microRNAs in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2014; 14: 147–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seronde M‐F, Vausort M, Gayat E, Goretti E, Ng LL, Squire IB, Vodovar N, Sadoune M, Samuel J‐L, Thum T, Solal AC, Laribi S, Plaisance P, Wagner DR, Mebazaa A, Devaux Y, GREAT network . Circulating microRNAs and outcome in patients with acute heart failure. Gupta S, ed. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0142237–e0142214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ovchinnikova ES, Schmitter D, Vegter EL, Maaten ter JM, Valente MAE, Liu LCY, van der Harst P, Pinto YM, de Boer RA, Meyer S, Teerlink JR, O'Connor CM, Metra M, Davison BA, Bloomfield DM, Cotter G, Cleland JG, Mebazaa A, Laribi S, Givertz MM, Ponikowski P, van der Meer P, van Veldhuisen DJ, Voors AA, Berezikov E. Signature of circulating microRNAs in patients with acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauters C, Kumarswamy R, Holzmann A, Bretthauer J, Anker SD, Pinet F, Thum T. Circulating miR‐133a and miR‐423‐5p fail as biomarkers for left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168: 1837–1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tutarel O, Dangwal S, Bretthauer J, Westhoff‐Bleck M, Roentgen P, Anker SD, Bauersachs J, Thum T. Circulating miR‐423_5p fails as a biomarker for systemic ventricular function in adults after atrial repair for transposition of the great arteries. Int J Cardiol 2013; 167: 63–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bayes‐Genis A, Lanfear DE, de Ronde MWJ, Lupón J, Leenders JJ, Liu Z, Zuithoff NPA, Eijkemans MJC, Zamora E, De Antonio M, Zwinderman AH, Pinto‐Sietsma S‐J, Pinto YM. Prognostic value of circulating microRNAs on heart failure‐related morbidity and mortality in two large diverse cohorts of general heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail 2017; 2: 429–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Luo P, He T, Jiang R, Li G. MicroRNA‐423‐5p targets O‐GlcNAc transferase to induce apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Mol Med Rep 2015; 12: 1163–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL, Borlak J, Haverich A, Gross C, Engelhardt S, Ertl G, Bauersachs J. MicroRNAs in the human heart: a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116: 258–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J, CKD‐EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2009; 150: 604–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turchinovich A, Weiz L, Burwinkel B. Extracellular miRNAs: the mystery of their origin and function. Trends Biochem Sci 2012; 37: 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goldraich LA, Martinelli NC, Matte U, Cohen C, Andrades M, Pimentel M, Biolo A, Clausell N, Rohde LE. Transcoronary gradient of plasma microRNA 423‐5p in heart failure: evidence of altered myocardial expression. Biomarkers 2014; 19: 135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nabiałek E, Wańha W, Kula D, Jadczyk T, Krajewska M, Kowalówka A, Dworowy S, Hrycek E, Włudarczyk W, Parma Z, Michalewska‐Włudarczyk A, Pawłowski T, Ochała B, Jarząb B, Tendera M, Wojakowski W. Circulating microRNAs (miR‐423‐5p, miR‐208a and miR‐1) in acute myocardial infarction and stable coronary heart disease. Minerva Cardioangiol 2013; 61: 627–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Eryılmaz U, Akgullu C, Beser N, Yıldız Ö, Kurt Ömürlü İ, Bozdogan B. Circulating microRNAs in patients with ST‐elevation myocardial infarction. Anatol J Cardiol 2016; 16: 392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]