Abstract

For animals, injury is inevitable. Because of this, organisms possess efficient wound healing mechanisms that can repair damaged tissues. However, the molecular and genetic mechanisms by which epidermal repair is accomplished remain poorly defined. Drosophila has become a valuable model to study epidermal wound healing because of the comprehensive genetic toolkit available in this organism and the similarities of wound healing processes between Drosophila and vertebrates. Other reviews in this Special Issue cover wound healing assays and pathways in Drosophila embryos, pupae and adults, as well as regenerative processes that occur in tissues such as imaginal discs and the gut. In this review, we will focus on the molecular/genetic control of wound-induced cellular processes such as inflammation, cell migration and epithelial cell-cell fusion in Drosophila larvae. We will give a brief overview of the three wounding assays, pinch, puncture, and laser ablation, and the cellular responses that ensue following wounding. We will highlight the actin regulators, signaling pathways and transcriptional mediators found so far to be involved in larval epidermal wound closure and what is known about how they act. We will also discuss wound-induced epidermal cell-cell fusion and possible directions for future research in this exciting system.

Keywords: wound healing, cell-cell fusion, actin, signaling pathway, Drosophila

Cellular processes in different wounding assays in Drosophila larvae

Drosophila has a long history of fundamental discovery related to developmental biology (Nüsslein-Volhard and Wieschaus, 1980; Wangler et al., 2015). So it was not surprising that the first studies to look at tissue repair in Drosophila exploited a developmentally-programmed morphogenetic event, dorsal closure (DC). During DC, two apposed epidermal sheets migrate dorsally and close a dorsal gap to form a continuous epidermal layer around the developing embryo (Harden, 2002; Young et al., 1993). DC, because of its amenability to videomicroscopy, has become a classical model to study epithelial sheet migration and the physical forces that drive morphogenesis (Hayes and Solon, 2017). One issue that arose with this model, however, is that it does not involve any cellular responses to tissue damage-a hallmark of actual physiological wound healing. Thus, other models that possessed this feature were developed in embryos, larvae, pupae, and adults.

The larval epidermis is a monolayer of post-mitotic epithelial cells. These cells continue to endoreplicate their DNA content through out the larval stages (Smith and Orr-Weaver, 1991; Wang et al., 2015) and grow to a substantial size (up to 50 μm across). A major function of these cells is to manufacture and secrete the cuticle that forms the larval exoskeleton and permeability barrier. Apically, larval epidermal cells possess microvilli believed to be specialized for cuticle assembly/secretion (Gangishetti etal., 2012; Payre, 2004) and basally they possess a basal lamina (Fessler et al., 1994) that separates them from the hemolymph filling the larval body cavity. Floating within this open circulatory system is a population of circulating innate immune hemocytes (blood cells) (Rizki and Rizki, 1980) that are potentially damage-responsive.

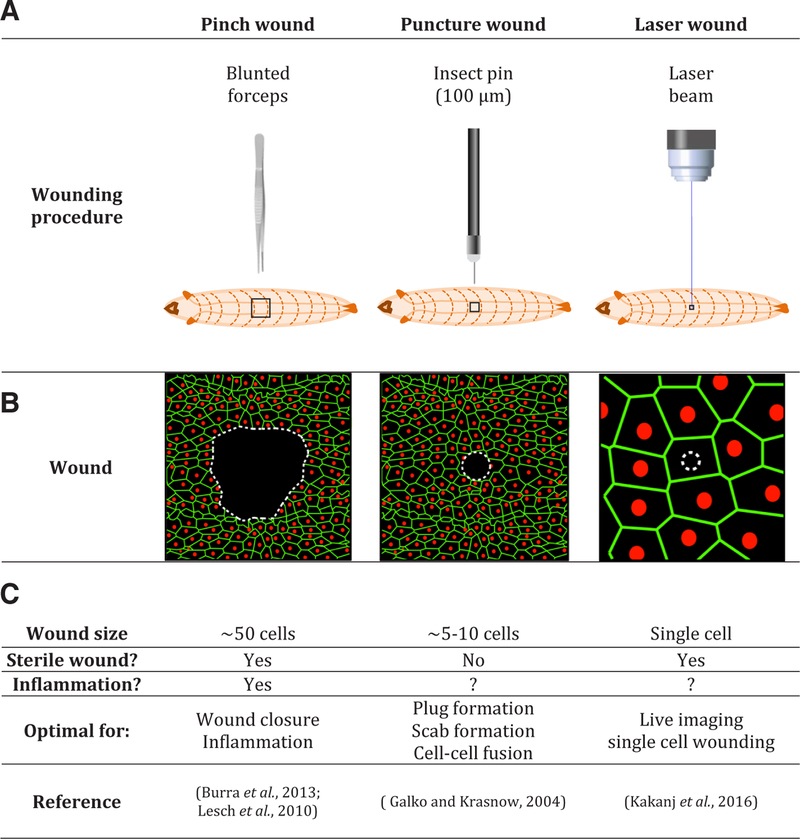

A number of assays have been developed to examine cellular responses to damage in larvae. (Fig. 1) (Burra et al., 2013; Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Kakanj et al., 2016). Puncture wounding uses a 100 μm diameter needle to pierce through both the cuticle barrier and the underlying epidermis (Galko and Krasnow, 2004). Punctured larvae bleed and form a melanized plug that prevents blood (hemolymph) loss. The process of sealing the wound site likely combines melanization (Bidla et al., 2005) with a protein-based hemolymph clotting system (Scherfer et al., 2004). Successful plug formation and survival after puncture wounding is dependent upon factors provided by a specialized set of hemocytes, crystal cells (Bidla et al., 2007; Meister, 2004; Rizki et al., 1985). Crystal cells, named after cystoplasmic crystalline deposits, promote the scab formation at wounds. These wounds also induce formation of a specialized blood cell type, lamellocytes (Márkus et al., 2005) that are typically involved in responses to parasitic wasps (Rizki and Rizki, 1992). The epidermal cells surrounding the plug orient towards it and in many cases fuse to form a syncytium (cell-cell fusion will be discussed further below). As these cell rearrangements are occurring, wound-edge epidermal cells extend long lamellar cellular processes and migrate across the wound gap to reestablish a continuous polarized epithelium. The puncture wound procedure is an excellent assay to study plug and scab formation as well as cell-cell fusion and other cell shape changes.

Fig. 1. Methods used to wound Drosophila larvae.

(A) Cartoons of the different wounding procedures. (B) Schematics of the larval epithelia after wounding. Membranes, green; Nuclei, red. White dashed lines indicate the wound edge. (C) Details of size, sterility, inflammation, optimal uses, and primary references.

A second wounding procedure creates scabless wounds. In this method blunted forceps are used to gently pinch larvae on the dorsal aspect of an abdominal segment (Burra et al., 2013). This procedure leaves the overlying cuticle intact but interrupts the continuity of the underlying epidermal sheet. Because the cuticle is not disrupted, pinched larvae do not bleed and do not form a plug and scab at the wound site. These wounds are thus sterile and allow the investigator to probe tissue damage-associated responses in the absence of cross-talk from infection. As with the smaller puncture wounds, wound-edge epidermal cells orient towards the wound, form syncytia (Galko and Krasnow, 2004), and elongate into the wound gap (Lesch et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2009). Within 24 hours, all the pinch-wounded animals have closed their wounds. Pinch wounding abrades a larger patch of the epidermal cells compared to the puncture technique. Because the wound site can be clearly viewed through the transparent and unmelanized cuticle, this procedure is a powerful model to study the genetic basis of wound closure (Lesch et al., 2010). However, the long timecourse of healing and the large area over which it occurs makes live-imaging of these wounds a substantial challenge. Interestingly, the shapes of individual cells change dramatically during wound healing. Before wounding cells are mostly pentagonal or hexagonal. However, more and more cells become irregularly shaped as the wounds are healed (Kwon et al., 2010).

Epidermal cells are not the only cells that are wound-responsive in larvae following pinch wounding. In addition, larvae possess macrophage-like cells called plasmatocytes that circulate within the open body cavity. Within a few hours after pinch wounding, those circulating plasmatocytes that encounter the wound attach to it. These cells then change their shape from approximately spherical to a spread morphology and contribute to phagocytosis of the cell debris at the wound sites (Babcock et al., 2008). The mechanisms of plasmatocyte recruitment to embryonic (Stramer et al., 2005) and pupal (Moreira et al., 2011) wounds are quite different, involving predominantly cell migration responses (Brock et al., 2008). In larvae, inflammation, as assessed by plasmatocyte recruitment, has only been examined in detail at pinch wounds.

A newcomer to the suite of wounding procedures used in larvae is laser-induced tissue damage (Kakanj et al., 2016). Lasers have long been used in the embryo (Wood et al., 2002). In larvae, lasers make wounds at essentially at the single cell level. These wounds activate responses in viable cells that surround the ablated cell. They heal more quickly than larger pinch and puncture wounds and thus permit live visualization of the spatially-restricted healing response. This is an advance because live imaging of puncture-or pinch-wounded larvae has been challenging due to local melanization (puncture wounds) and the difficulty of immobilizing larvae for over the full course of healing (pinch wounds).

Actin regulators that execute different cell behaviors during wound healing

Because pinch wounding creates a larger wound gap than the other wounding techniques, more epidermal cells around the wound participate in the healing process. A hallmark of wound healing in Drosophila larvae is that cell proliferation and apoptosis do not play essential roles during this process (Lesch et al., 2010; Tsai et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). This differs from wound healing responses in most vertebrate epithelia (Park et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017) but offers the opportunity to study wound closure that is not driven in part by proliferative generation of new cells. In larvae, epidermal cells cover the wound gap by the combined actions of cell migration and cell growth. A result of these cellular responses is that the engaged epidermal cells change dramatically in shape during the first several hours of healing (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Kwon et al., 2010). Within a few hours after wounding the leading-edge cells send out cellular processes toward the wound center (Wu et al., 2009), whereas the cells behind these follow and change their shapes as they do so (Lesch et al., 2010). The cellular behaviors of leading-edge cells and followers are similar to the collective migration observed in cell culture (Lesch et al., 2010; Simpson et al., 2008; Vitorino and Meyer, 2008).

Cell shape changes and cell migration require cytoskeletal remodeling (Brüser and Bogdan, 2017). Consistent with this, several actin regulators have been found to play critical roles during wound healing (Table 1). Epidermal cells around the wound margin detach from the cuticle nearest to the wound edge and send out long cell protrusions (both filopodia and lamellipodia) within a few hours of pinch wounding (Wu et al., 2009) (Fig. 2A). Indeed, levels of filamentous actin rapidly increase around the wound margin (Kakanj et al., 2016; Kwon et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2009) and several actin regulators are required for this increased actin (Baek et al., 2010; Baek et al., 2012; Brock et al., 2012; Kakanj et al., 2016) (Fig. 2B). The actin cable observed a few hours after pinch wounding is discontinuous (Brock et al., 2012), whereas a continuous actomyosin cable that surrounds the wounds was observed in the laser-wounded epidermis (Kakanj et al., 2016).

TABLE 1.

WOUND CLOSURE GENES IN DROSOPHILA LARVAE

| Class | Gene name | Human homolog | Functions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actin regulators | Rac1 | RAC | GTPase | (Baek et al., 2010; Lesch et al., 2010) |

| Cdc42 | CDC42 | GTPase | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Arp10 | ACTR10 | Arp2/3 complex | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Arp2 | ACTR2 | Arp2/3 complex | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| SCAR | WAVE/WASF3 | Arp2/3 complex | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| zip | MYH10 | Nonmuscle myosin II heavy chain | (Kwon et al., 2010) | |

| Pak3 | PAK3 | Target of Rac1 | (Baek et al., 2012) | |

| chic | Profilin/PFN4 | Actin recycling | (Brock et al., 2012) | |

| Gγ1 | GNG7 | Cell shape | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Mbc | DOCK | Phagocytosis | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Ced-12 | ELMO | Phagocytosis | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Signaling pathway | Slpr | JNKKK/MAP3K11 | JNK signaling | (Lesch et al., 2010) |

| Hep | JNKK2/MAP2K7 | JNK signaling | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Bsk | JNK/MAPK8 | JNK signaling | (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| Pvr | PDGFR/VEGFR | Pvr signaling | (Wu et al., 2009) | |

| Pvf1 | PDGF/VEGF | Pvr signaling | (Wu et al., 2009) | |

| InR | Insulin receptor | Insulin signaling | (Kakanj et al., 2016) | |

| Tor | MTOR | TOR signaling | (Kakanj et al., 2016) | |

| wts* | LATS | Hippo signaling | (Tsai et al., 2017) | |

| ex* | FRMD1 | Hippo signaling | (Tsai et al., 2017) | |

| Transcription factors | DJun/Jra | JUN | JNK signaling | (Lesch et al., 2010) |

| DFos/kay | FOS | JNK signaling | (Lesch et al., 2010) | |

| foxo* | FOXO | Insulin signaling | (Kakanj et al., 2016) | |

| yki | YAP | Hippo signaling | (Tsai et al., 2017) | |

| sd | TEAD | Hippo signaling | (Tsai et al., 2017) | |

| Proteases | Mmp1 | MMP | ECM Cleavage | (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012) |

| Mmp2 | MMP | ECM Cleavage | (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012) | |

Note: Loss-of-functions of above genes show wound closure defects except for foxo, wts and ex. In contrast, gain-of-functions of foxo, wts and ex show wound closure defects, which are denoted by.

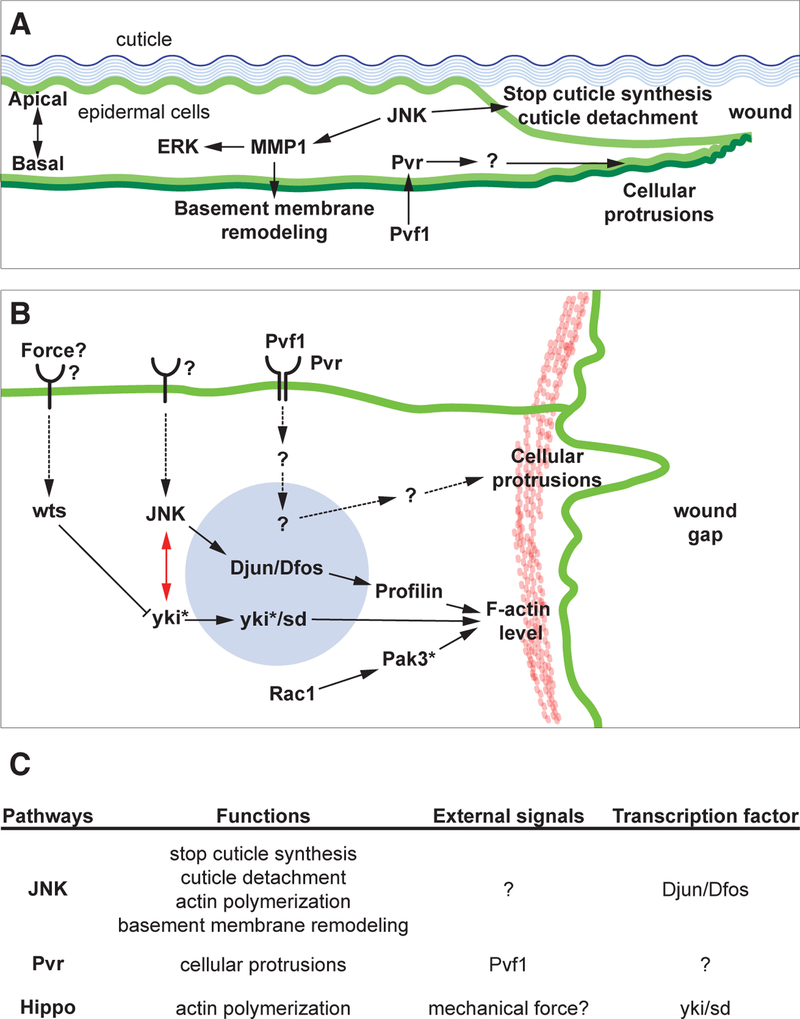

Fig. 2. Signaling pathways that regulate cellular responses in wound-edge cells.

(A) Cartoon of transverse view of a wound edge larval epidermal cell annotated with cellular structures and functions of wound healing pathways. (B) Cartoon of top-down view of a wound edge larval epidermal cell. Receptors and ligands that affect pinch wounding are illustrated as are selected pathway components, in particular transcription factors and target genes that regulate actin. Double-headed red arrow indicates the genetic interaction between JNK and yki signaling. Other pathway interactions or lack thereof are addressed in the text. Asterisk: proteins that show translocation after wounding. (C) Table summarizing wound healing pathway functions, signals, and transcription factors, if known. The role of insulin signaling in healing of multicellular wounds is not yet clear and is not depicted here-please refer to the section on insulin signaling for its roles in single cell healing in the larval epidermis.

A cytoskeleton regulator that acts downstream of Rac1, P21-activated kinase 3 (Pak3), translocates to the wound margin a few hours after wounding and is required for both wound closure and up-regulation of filamentous actin around the wound margin (Baek et al., 2012). Similarly, a regulator of actin turnover dynamics– Profilin, encoded by chickadee (chic) in Drosophila, is also required for epidermal wound closure. Profilin protein levels increase surrounding the wound throughout and following active closure. Loss of chic reduces actin polymerization around the wound (Brock et al., 2012). Interestingly, RNAi transgenes targeting Drosophila yorkie (yki), a YAP-like transcriptional activator, and scalloped (sd), a TEA Domain family protein-like transcription factor (TEAD), common transcriptional mediators of the Hippo pathway, also cause reduced actin polymerization around the wound edge and wound closure defects (Tsai et al., 2017).

Similar to DC, the Drosophila non-muscle myosin II heavy chain, encoded by zipper (zip), is also required for wound closure (Kwon et al., 2010). Larvae with the myosin II heavy chain knocked down by RNAi in the epidermis show altered cell shape distributions. Normally cells around the wound assume irregular shapes whereas those lacking zipper stay relatively polygonal. Furthermore, both the myosin II heavy chain and the light chain, encoded by spaghetti squash, translocate to the rear end of the cell cortex in the first few rows of epidermal cells around the wound edge, leading to a polarized non-muscle myosin II subcellular localization a few hours after wounding (Kwon et al., 2010). Multiple Rho GTPases (Rac1, Cdc42 and Rho1) are required for Myosin II polarization (Baek et al., 2010). As Rac1 and Cdc42 are required for wound closure (Lesch et al., 2010), this may be an important signal to direct epidermal cell migration toward the center of the wound. Other known regulators of actin dynamics (Arp10, Arp2, Gγ1, SCAR, mbc, Ced-12) exhibit wound closure defects when targeted by RNAi in the larval epidermis (Lesch et al., 2010) but their specific effects on actin or myosin localization have yet to be determined.

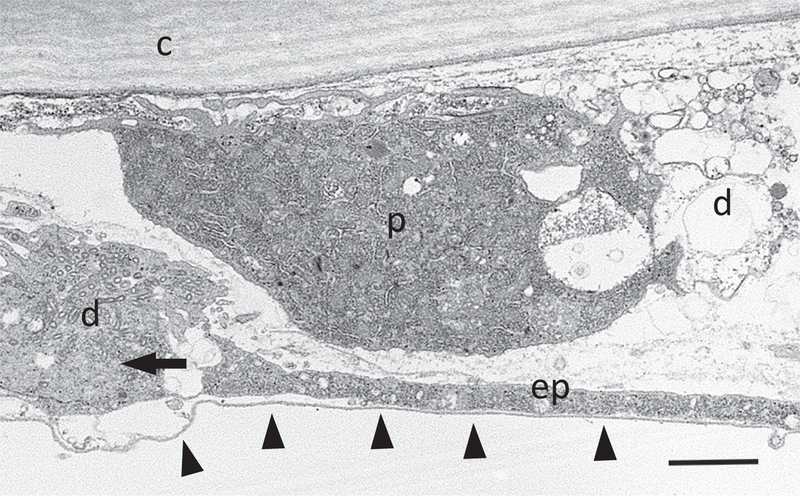

Basement membrane dynamics also appear to be important for proper closure. The long cellular processes that extend into the wound gap possess a basal lamina along their entire length even when they are very thin and even where the cell is detached from cuticle at the apical surface (Fig. 3). How this extension/stretching of the basal lamina is achieved is not clear. What is clear is that loss of the proteases matrix metalloprotease 1 and 2 (MMP1 and MMP2) blocks puncture wound closure (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012). Moreover, MMP1, is required in the epidermis to promote reepithelialization by remodeling the basement membrane, facilitating cell elongation and actin cytoskeletal reorganization (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012). MMP1 induction around the wound requires Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling as does Profilin induction (Brock et al., 2012). Below we discuss the various signaling pathways required for wound closure and what is known about their transcriptional targets.

Fig. 3. Wound-edge epidermal cell processes possess a basal lamina along their entire length.

A transverse section of a whole-mount epidermis eight hours after wounding under transmission electron microscopy. The basal side of the thin process contains a basal lamina (arrowheads) to the end of the extension (arrow). ep, epidermal process; c, cuticle; d, wound site debris; p, plasmatocyte. Scale bar, 2 μm.

Signaling pathways that regulate wound healing

Multiple signaling pathways play important roles during wound healing in mammals (Eming et al., 2014). Until recently (Pineda et al., 2015), it has been difficult to visualize wound closure in mice and determine more precise phenotypes of such pathways. Analysis of orthologous pathways in Drosophila, in addition to basic gene discovery, is a place where fly wound healing studies can have a major impact. Indeed, several signaling pathways that are required for wound healing in larvae have clear orthologs and/or conserved functions in vertebrates. Here we summarize the diverse signaling pathways that act during larval wound closure (see also Table 1) and synthesize how they regulate different cellular functions at the wound (Fig. 2).

Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) signaling

JNK is a member of the mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) family, and plays important roles during development, physiology and disease (Weston and Davis, 2007). JNK (encoded by basket in flies) was originally implicated in DC (Riesgo-Escovar et al., 1996; Sluss et al., 1996). basket mutant embryos fail to complete DC resulting in a phenotype where the embryo resembles an open basket. Similarly, JNK signaling is also required for thorax closure during metamorphosis (Zeitlinger and Bohmann, 1999). Interestingly, JNK signaling is rapidly activated around wound sites, as indicated by two pathway reporters, msn-lacZ and puc-lacZ (Galko and Krasnow, 2004). The activation of the pathway suggested that it might be functionally required for closure and, indeed, epidermal expression of RNAi transgenes targeting several JNK pathway components, including JNK kinase kinase kinase (Jun4K, misshapen), JNK kinase kinase (Jun3K, slipper), JNK kinase (Jun2K, hemipterous), JNK (basket), DJun (Jun-related antigen) and DFos (kayak), all led to a substantial impairment of wound closure (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Lesch et al., 2010).

What are the essential functions of JNK signaling during wound healing? RNAi transgenes targeting JNK caused a strong wound closure defect but did not abolish actin polymerization and cell protrusion around the wound (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Wu et al., 2009). However, expression of a dominant negative form of the JNK, which leads to a more potent block of function (Lesch et al., 2010), did reduce actin polymerization around the wound margin (Kwon et al., 2010). This latter study also showed that loss of JNK blocked polarization of non-muscle myosin II and epidermal cell shape changes following wounding. Knockdown of JNK also abolished wound-induced Mmp1 up-regulation, which is important for basement membrane remodeling and cell elongation (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012). Finally, JNK signaling is also important for leading-edge epidermal cells to either disassociate from the apical cuticle or to stop cuticle synthesis-events that appear to facilitate effective epidermal cell migration (Wu et al., 2009). The combined effect of these diverse processes-on actin dynamics, basement membrane dynamics, cuticle adhesion, and gene expression (see Fig. 2 A–C and below) lead to a highly penetrant wound closure defect when JNK signaling is blocked. One important outstanding question is what genes act upstream of JNK activation within leading edge cells. The Rac1, Cdc42 and Rho1 GTPases can all activate JNK signaling in the unwounded epidermis although the strongest block of wound-induced JNK induction is observed with inhibition of Rac1 (Baek et al., 2010). A remaining question in both wound closure and DC is what is the external signal(s) that activate JNK signaling in these contexts.

Platelet-derived growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor-receptor related (Pvr) signaling

In mice, vascular Endothelial Growth Factor signaling primarily regulates angiogenesis during wound healing (Bao et al., 2009). Knockout of VEGF-A, a pathway ligand, specifically in keratinocytes reduced angiogenesis and delayed wound healing (Rossiter, 2004). Interestingly, the Drosophila VEGFR homolog, Pvr (Cho et al., 2002; Heino et al., 2001) and one of its ligands, Pvf1, are required for epidermal wound closure (Wu et al., 2009). In thorax closure during metamorphosis, Pvr signaling acts upstream of JNK signaling (Ishimaru et al., 2004). However, in wound closure Pvr appears to act in parallel to JNK signaling (Fig. 2 A,B) because JNK reporters are activated at normal levels in the Pvr-deficient epidermis (Wu et al., 2009). Interestingly, both Pvr/VEGFR and Pvf1/VEGF are functionally required in the epidermis, indicating that Pvf1/Pvr signaling acts in an autocrine fashion. The current model is that tissue damage/wounding exposes Pvr/VEGFR to ligand that is sequestered from the receptor in the unwounded state. This exposure then initiates epidermal cell migration (Wu et al., 2009). Morphological comparison of wound-edge cells lacking Pvr/VEGFR indicated that Pvr/VEGFR is critical for cells to extend a cellular process into a wound gap. So far, the exact downstream mediators of Pvr/VEGFR signaling are yet to be identified. One common downstream factor of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) signaling, ERK/MAPK, was phosphorylated upon wounding (Wu et al., 2009). However, this activation is not Pvr-dependent suggesting that the transduction pathway downstream of Pvr/ VEGFR may be non-canonical in some respects. Interestingly, Erk activation following wounding is MMP1-dependent (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012).

Insulin and TOR signaling

Diabetic patients have reduced or abnormal insulin and TOR signaling, and often exhibit impaired wound healing (Eming et al., 2014). Angiogenesis defects have been linked to compromised wound healing in diabetes (Okonkwo and Dipietro, 2017). However, it is not completely understood whether TOR and insulin signaling are required within the epidermis for normal wound closure. Using laser wounding in larvae (Fig. 1), the requirements of these signaling pathways were tested. Interestingly, insulin/FOXO and TOR/S6k signaling regulate epidermal wound healing in parallel, where insulin signaling activates actomyosin ring assembly but not glycogen metabolism (Kakanj et al., 2016). Consistent with these findings, mammalian keratinocytes reduce their migratory capacity under high sugar conditions in culture (Lan et al., 2008; Morita et al., 2005; Song et al., 2008). This suggests that a function of insulin and TOR signaling pathways during skin wound healing may be conserved between invertebrates and vertebrates, an idea supported by keratinocyte-specific deletion of FOXO1 in mice (Zhang et al., 2015). It will be interesting to test if these signaling pathways are also required for healing pinch wounds since the main driving force for this type of wounding is cell migration rather than actomyosin-based contraction. It will also be interesting to determine whether insulin signaling is required for wound healing in the embryo, pupa, or adult. Potential interactions between insulin signaling and other wound healing pathways (JNK, Pvr, Yorkie) have yet to be examined.

Hippo pathway

Drosophila YAP, which is encoded by yorkie (yki), the transcriptional activator of the Hippo pathway, controls organ size and tissue regeneration through its well-characterized roles in balancing apoptosis (Huang et al., 2005; Udan et al., 2003) and cell division (Lin and Pearson, 2014). Interestingly, Yki and its binding partner, Scalloped (Sd– TEAD in mammals), are required for epidermal wound closure but they do this without balancing apoptosis and cell division in this tissue (Tsai et al., 2017). Another recent study showed that Yki regulates cell shape in the tracheal system without effects on proliferation/apoptosis (Robbins et al., 2014). Interestingly, Yki and Sd regulate actin polymerization at the wound edge to promote wound healing (Tsai et al., 2017). In this context, overexpression of Warts (LATS in human) and Expanded (FRMD1 in human), two negative regulators of Yki, also blocked wound closure, indicating that at least part of the canonical Hippo pathway signaling cascade is involved in this process. Moreover, genetic analysis suggests that Yki interacts with the JNK pathway (See Fig. 2B) and likely acts downstream of or parallel to JNK signaling during wound closure (Tsai et al., 2017).

During wound closure multiple cell behaviors such as cell migration and actin remodeling are activated. The signaling pathways discussed above control these responses in part through direct signaling effects but also likely through regulation of gene transcription and chromatin remodeling. Below we will discuss what is known about the regulation of gene expression during larval wound healing and the connection between transcriptional responses and signaling pathways required for closure. Other reviews in this Special Issue cover transcriptional events that accompany regeneration of other tissues such as imaginal discs and the adult gut epithelium.

Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation during larval wound healing

Cuticle secretion to create a robust barrier is the main physiological function of larval epidermal cells. However, upon wounding the migrating front of leading edge epidermal cells transiently stops synthesizing cuticle (Wu et al., 2009). This drastic cellular response and others such as cell shape changes are likely to be regulated at both the transcriptional and epigenetic levels. To determine whether epigenetic modifiers change expression levels upon wounding, fluorescently tagged reporters for different epigenetic factors were examined (Anderson and Galko, 2014). Seven regulators showed strongly diminished expression at the wound edges after wounding. Three down-regulated proteins– Osa, Kismet and Spt6, are generally associated with active chromatin (Andrulis et al., 2000; Kaplan et al., 2000; Kennison and Tamkun, 1988; Srinivasan, 2005; Srinivasan et al., 2008), while four others, Sin3A, Sap130, Mi-2 and Mip120, are more associated with repressed chromatin (Ahringer, 2000; Ayer, 1999; Bernstein et al., 2000; Fazzio et al., 2001; Kehle et al., 1998; Korenjak et al., 2004; Lewis et al., 2004; Spain et al., 2010). The fast clearance of both positive and negative chromatin modifiers may allow wound-edge epidermal cells to alter their transcriptional response in a fairly global way after wounding (Anderson and Galko, 2014). Pvr and JNK signaling are not required for the clearances (Anderson and Galko, 2014), suggesting that other early wound signals exist. It will be interesting to test if other wound healing pathways are required for this clearance.

In addition to epigenetic regulators, several transcription factors are activated upon wounding and are necessary for wound closure (table 1). For example, DJun and DFos, the downstream transcription factors of the JNK signaling pathway, are also required for wound closure (Lesch et al., 2010). This suggests that transcriptional responses are required for wound closure to proceed normally. Indeed, DFos is required for induction of a transcriptional target, Jun4K (misshapen/msn in flies), which is also important for normal wound closure (Lesch et al., 2010). Moreover, DJun and DFos are both required to activate increased expression of the actin regulator, Profilin/chic, to promote wound healing (Brock et al., 2012). Finally, wound-induced Mmp1 up-regulation is also JNK dependent (Stevens and Page-McCaw, 2012), though specific roles for DJun and DFos were not examined in this study. Presumably there are the other transcriptional targets of JNK signaling that are important for various aspects of wound closure and identifying these targets will be important moving forward.

Activation of the insulin receptor following wounding leads to the translocation of the transcription factor, Foxo, from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This ensures proper actomyosin cable assembly, indicating that a normal function of Foxo is to suppress actomyosin cable assembly through as yet undefined targets and mechanisms (Kakanj et al., 2016). In addition, Yki translocates to the nucleus in some of the epidermal cells around the wound (Tsai et al., 2017). Both yki and sd are required for wound closure. However, the transcriptional targets of Yki/Sd that regulate actin cytoskeleton are still unknown in this context. Interestingly, transcription levels of several actin-related genes were up-regulated when Salvador (Salv1), which encodes a critical adaptor protein for Hippo activation, was conditionally knockout during heart regeneration in mice (Morikawa et al., 2015). Also, YAP/TEAD activates of several migration-related genes in human cancer cell lines (Liu et al., 2016). It will be interesting to know whether yki/ sd also activates these genes during larval wound closure. Finally, reporters that reflect the activity of Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) transcription factor are activated slightly later and further away from the wound center than JNK signaling (Lee et al., 2017). Interestingly, loss-of-STAT reduced wound-induced integrin transcription and restricted cell-cell fusion in the vicinity of the healing wounds (Lee et al., 2017). The next section discusses wound-induced cell-cell fusion in more detail.

While several transcription factors have been placed downstream of different signaling pathways, roles for other transcription factors (for instance is there a factor that acts downstream of Pvr signaling?) and the full suite of downstream functional targets remains to be identified. In addition, how the epigenetic changes observed upon wounding couple to wound-induced transcriptional regulation will be an intriguing topic to pursue.

Wound-induced and genetic-induced epidermal cell-cell fusion

Multinucleate cells are observed near wounds within hours of wounding in larvae (Galko and Krasnow, 2004), pupae (Wang et al., 2015) and adults (Losick et al., 2013), suggesting that cell-cell fusion (syncytium formation) is a common cellular process during wound healing at most developmental stages in Drosophila. Although the function of cell-cell fusion during wound healing in larval and pupa is still unclear, cell-cell fusion appears to be critical for epidermal wound healing in adult flies (Losick et al., 2013).

JNK signaling is activated with similar kinetics as the start of cell-cell fusion. Nevertheless, JNK signaling is not required for wound-induced cell-cell fusion (Galko and Krasnow, 2004; Wang et al., 2015). To date, the signaling pathways that are required for wound-induced cell-cell fusion are still unknown. However, an important adhesion complex that suppressed cell-cell fusion has been reported, as has an interesting crosstalk with wound-induced JNK signaling. The integrin focal adhesion (FA) complex is critical for cells to bind to extracellular matrix as well as to send and receive signals (Legate et al., 2009). Loss of Integrin β4α6 in mice leads to cell adhesion defects, epidermolysis bullosa and, neonatal death (Dowling et al., 1996; Georges-Labouesse et al., 1996). In Drosophila larvae, members of this complex also suppresses epithelial syncytium formation. Loss of the FA adaptor PINCH (particularly interesting new cysteine-histidine-rich protein), integrin-linked kinase (ILK), or β-integrin itself in the larval epidermis resulted in multinucleate epidermal cells even without wounding (Wang et al., 2015). Interestingly, genetic reduction of integrin FA complex components, similar to wounding itself, also activated JNK signaling. This would appear to constitute a positive feedback loop as JNK signaling hyperactivation also disassembled integrin FA complex in larval epidermal cells (Wang et al., 2015). Disassembly of the integrin FA complex was examined in both the wounded epidermis and upon JNK hyperactivation in the absence of wounding. In both cases, PINCH translocated from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm, while ILK translocated from the plasma membrane to the nucleus (Wang et al., 2015). Presumably, the relocalized proteins cannot participate in functional adhesion. How FA complex disassembly is mediated at the mechanistic level and why disassembly should result in cell-cell fusion are open questions.

Epidermal cell-cell fusion seems to also involve transcriptional responses. Integrin levels increased dramatically after JNK signaling hyperactivation (Wang et al., 2015) or physical wounding (Lee et al., 2017). The actual mechanisms and functions of the integrin up-regulation are still not clear but increased Integrin expression may help stabilize the epidermis upon wounding or hyperactiva-tion of JNK signaling. Interestingly, loss of Drosophila Jun4K (msn in flies), which encodes an upstream kinase of the JNK signaling cascade, also increased wound-induced cell fusion (Lesch et al., 2010). This suggests that Msn suppresses wound-induced cell-cell fusion, a different function from that observed upon JNK hyperactivation (Wang et al., 2015).

Cell-cell fusion is also regulated by Janus kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling (Lee et al., 2017). JAK/STAT signaling is activated later than JNK signaling during wound healing. Like loss of integrin-FA components, loss of JAK/STAT signaling increased syncytial cell formation around pinch wounds, indicating a suppressive role in cell-cell fusion. This may provide a mechanism to spatially restrict cell-cell fusion as JNK activation and JAK-STAT activation occur in different spatial domains. JNK signaling is activated in the first few rows of cells bordering the wound, whereas JAK/STAT signaling is activated more distally (Lee et al., 2017). Indeed, wound-induced cell-cell fusion primarily occurs in the JNK activation domain rather than JAK/STAT activation domain. Interestingly, this study also found that integrin is one of the downstream targets of JAK/STAT signaling upon wounding (Lee et al., 2017). However, wound-induced integrin expression was detected within the JNK activation domain prior to the activation of JAK/STAT signaling. Therefore, it is likely that control of wound-induced integrin expression requires more inputs than solely JAK/STAT signaling.

Future directions - sensing a wound and initiation of wound healing

Although certain genes and signaling pathways are crucial for larval wound healing, many open questions remain. One of the fundamental questions, for any repair process, ishow does the tissue first sense the wound and initiate appropriate wound responses? JNK signaling is rapidly turned on after wounding (Galko and Kras-now, 2004) and loss-of-JNK affects cuticle detachment, migration efficiency, and abolishes cell shape changes in both leading edge and follower cells (Kwon et al., 2010; Lesch et al., 2010). Thus, JNK signaling is a decent candidate for an early signal produced upon wounding. The main question here, and one that still persists even with respect to DC, is what external signal activates the JNK cascade? Attractive candidates include soluble signals known to activate JNK signaling in other contexts (Igaki et al., 2009), danger signals produced directly by tissue damage (Srinivasan et al., 2016) or mechanical force itself (Pereira et al., 2011).

The VEGFR/Pvr and its ligand Pvf1 are also reasonable candidates for an early signal. Pvf1 becomes accessible to its receptor following wounding and epidermal Pvr is required for closure (Wu et al., 2009). In the Pvr-deficient epidermis, a bulge of cytoplasm still accumulates at the wound edge (see Wu Fig. 2D), suggesting the wound edge cells can actually sense the presence of the wound. Similarly, in the JNK-deficient epidermis, leading edge cells protrude slightly into the wound gap although they are hindered by their continued synthesis of and attachment to the cuticle (see also Wu et al., 2009, Fig. 2E). The experimental evidence for cell responsiveness (even if aberrant) in JNK-and Pvr-deficient larvae suggests that there are earlier signals produced and used to sense the presence of the wound. In embryos and pupae reactive oxygen species (ROS) are activated/produced very early after wounding to help recruit immune cells (Moreira et al., 2010; Niethammer et al., 2009; Razzell et al., 2013). Although immune cells in larvae are not recruited through migration (Babcock et al., 2008), it is possible that high levels of epidermal ROS serve as an early priming signal for other responses and pathways.

Physical force has long been proposed as a wound-induced signal (Enyedi and Niethammer, 2015; Harn et al., 2017). Recently, techniques have been developed to evaluate membrane tension/ contraction using retraction velocity of membrane segments upon laser cutting (Colombelli and Solon, 2013). This was recently used to measure the contractile force of the actomyosin networks (Fernandez-Gonzalez and Zallen, 2013) and membrane tension during wound healing in the embryo (Kobb et al., 2017). Although more technically challenging, it will be interesting to measure membrane tension before and after wounding both in control larvae and in larvae deficient for pathways known to be required for wound closure. Physical force/tension can also regulate the Hippo pathway (Aragona et al., 2013; Dupont et al., 2011; Rauskolb et al., 2014). As with other pathways it will be interesting to test whether tension also regulates Hippo signaling during larval wound healing given that Yap/Yki rapidly translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus upon wounding (Tsai et al., 2017). A tool that would be helpful is a way to deliver a defined local force to the larval cuticle so that both tissue damage and molecular pathway readouts can be systematically analyzed as a function of force and/or extent of damage. The mechanical filaments used in behavioral nociception studies (Kim et al., 2012) may be adaptable for this purpose.

Future directions - coordination of collective migration during wound healing

Larval epidermal wound healing is a form of collective migration because the epidermal cells involved migrate as a sheet, maintaining their connections to each other even as they heal the wound. Because of this, the responses of leading edge cells and follower cells need to be coordinated in order to close a wound. There is evidence already for distinct cellular responses of wound-edge and follower cells (Kwon et al., 2010; Lesch et al., 2010). Different wound closure genes can result in very distinct open wound phenotypes. Indeed, RNAi transgenes targeting Ced-12 (a PH-domain-containing adaptor protein) appear to have highly efficient follower cell migration and impaired leading edge migration (Lesch et al., 2010). This suggests that the cellular responses of leader and follower cells, though potentially linked, can be genetically separated.

How are different signaling pathways activated in the leading cells or the followers? Wound-induced JNK signaling activation forms a gradient, with the cells closest to the wound showing the highest levels of JNK activation (Galko and Krasnow, 2004). One possibility is that different levels of JNK activation promote different cellular functions in a manner similar to the actions of developmental morphogens. In addition, during another Pvr-regulated collective migration process, border cell migration during oogenesis, the active (phosphorylated) Pvr was highly enriched at the front end of the leading cells compared to other regions of the border cell cluster (Janssens et al., 2010). Higher Pvr activation in the leading cells increases faster endosome recycling, which maintains polarized distribution of Pvr activation (Wan et al., 2013). It will be interesting to test if Pvr is activated preferentially in the leading cells or has other functions in the follower cells.

Another model is that different pathways are activated in different spatiotemporal domains and control responses appropriate to those times and locations. There is already some evidence for this-JAK/STAT signaling is activated farther away from the wound and later after wounding than JNK is (Lee et al., 2017). This interplay regulates the spatiotemporal extent of wound-induced cell-cell fusion (Lee et al., 2017). Ultimately, cells surrounding the wound need to integrate the combined inputs and crosstalk between the pathways activated at their location and over time. Exploring the crosstalk between signaling pathways (Fig. 2) and how they impact different cellular behaviors during wound healing will continue to be important moving forward.

Future directions - genetic analysis of wound healing in real time

Larval wound healing serves as a powerful screening platform to identify genes that are required for wound healing (Baek et al., 2010; Lesch et al., 2010). With new advances in live imaging, it is now possible to monitor the whole healing processes of single-cell laser wounds (Kakanj et al., 2016). Technical challenges still exist for visualizing larger wounds that take longer to heal. The development of live reporters for different signaling pathways (Bach et al., 2007; Chatterjee and Bohmann, 2012; Kakanj et al., 2016) open up the exciting possibility that it will soon be possible to monitor signaling outputs live in both space and time. However, it is still challenging to test at exactly when either before or after wounding these genes are important. Most of the loss-of-function studies performed to date turn off gene function throughout the entire larval stage. Therefore, it will be informative and important to develop tools that manipulate gene function at any desired time and location. For instance, advances in spatial (Luan et al., 2006) and temporal (McGuire et al., 2004; Osterwalder et al., 2001) control of the Gal4/ UAS system may allow differential interrogation of the functions of genes in leading edge and follower cells. Another tool that will likely be useful moving forward is optogenetic manipulation of signaling events. For example, a recent study showed that Erk signaling can be regulated at specific times and regions during Drosophila embryogenesis (Johnson et al., 2017). Similar approaches could be combined with the live imaging system (Kakanj et al., 2016) to uncover the detailed signaling dynamics following wounding.

Summary

Larval epidermal wound healing is a powerful platform to identify genes that are required for postembryonic wound healing. Many signaling pathways and their functions have been identified in this system. Although there are still many remaining questions to be explored, the knowledge gained from this system is likely to have implications in tissue repair and regeneration in other organisms since wound healing is highly conserved in metazoans.

Acknowledgements

We thank members of the Galko lab for comments on the manuscript. CRT was supported by American Heart Association (AHA) predoctoral fellowship 16PRE30880004. MJG and the wound healing work in his laboratory is supported by NIH R35 GM126929.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- Arp2

actin-related protein 2

- Arp10

actin-related protein 10

- bsk

basket

- Ced-12

cell death abnormality protein-12

- chic

chickadee

- DC

dorsal closure

- D-Fos

Drosophila Fos

- D-Jun

Drosophila Jun

- ex

expanded

- FA

focal adhesion

- foxo

forkhead box sub-group O

- Gγ1

G protein γ1

- hep

hepmipterus

- ILK

integrin-linked kinase

- InR

insulin receptor

- JAK

Janus kinase

- mbc

myoblast city

- Mmp

matrix metalloproteinase

- Pak3

P21-activated kinase 3

- PINCH

particularly interesting new cysteine-histidine-rich protein

- Pvr

PDGF- and VEGF-receptor related

- sd

scalloped

- slpr

slipper

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- Tor

target of rapamycin

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- wts

warts

- yki

yorkie

- zip

zipper

References

- AHRINGER J (2000). NuRD and SIN3: Histone deacetylase complexes in development. Trends Genet 16: 351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON AE, GALKO MJ (2014). Rapid clearance of epigenetic protein reporters from wound edge cells in Drosophila larvae does not depend on the JNK or PDGFR/VEGFR signaling pathways. Regeneration 1: 11–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRULIS ED, GUZMÁN E, DÖRING P, WERNER J, LIS JT (2000). High-resolution localization of Drosophila Spt5 and Spt6 at heat shock genes in vivo: Roles in promoter proximal pausing and transcription elongation. Genes Dev 14: 2635–2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARAGONA M, PANCIERA T, MANFRIN A, GIULITTI S, MICHIELIN F, ELVASSORE N, DUPONT S, PICCOLO S (2013). A mechanical checkpoint controls multicellular growth through YAP/TAZ regulation by actin-processing factors. Cell 154: 1047–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AYER DE (1999). Histone deacetylases: Transcriptional repression with SINers and NuRDs. Trends Cell Biol 9: 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BABCOCK DT, BROCK AR, FISH GS, WANG Y, PERRIN L, KRASNOW MA, GALKO MJ (2008). Circulating blood cells function as a surveillance system for damaged tissue in Drosophila larvae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10017–10022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BACH E a., EKAS L a., AYALA-CAMARGO A, FLAHERTY MS, LEE H, PERRIMON N, BAEG GH (2007). GFP reporters detect the activation of the Drosophila JAK/STAT pathway in vivo. Gene Expr Patterns 7: 323–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAEK SH, CHO HW, KWON YC, LEE JH, KIM MJ, LEE H, CHOE KM (2012). Requirement for Pak3 in Rac1-induced organization of actin and myosin during Drosophila larval wound healing. FEBS Lett 586: 772–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAEK SH, KWON YC, LEE H, CHOE KM (2010). Rho-family small GTPases are required for cell polarization and directional sensing in Drosophila wound healing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 394: 488–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAO P, KODRA A, TOMIC-CANIC M, GOLINKO MS, EHRLICH HP, BREM H, PH D (2009). The role of vascular endothelial growth factor in wound healing. J Surg Res 153: 347–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERNSTEIN BE, TONG JK, SCHREIBER SL (2000). Genomewide studies of histone deacetylase function in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 13708–13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIDLA G, DUSHAY MS, THEOPOLD U (2007). Crystal cell rupture after injury in Drosophila requires the JNK pathway, small GTPases and the TNF homolog Eiger. J Cell Sci 120: 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BIDLA G, LINDGREN M, THEOPOLD U, DUSHAY MS (2005). Hemolymph coagulation and phenoloxidase in Drosophila larvae. Dev Comp Immunol 29: 669–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROCKAR, BABCOCK DT, GALKO MJ (2008).Active cop, passive cop developmental stage-specific modes of wound-induced blood cell recruitment in Drosophila. Fly (Austin) 2: 303–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROCK AR, WANG Y, BERGER S, RENKAWITZ-POHL R, HAN VC, WU Y, GALKO MJ (2012). Transcriptional regulation of Profilin during wound closure in Drosophila larvae. J Cell Sci 125: 5667–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRÜSER L, BOGDAN S (2017). Molecular control of actin dynamics in vivo: Insights from Drosophila. Handb Exp Pharmacol 235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURRAS, WANG Y, BROCKAR, GALKO MJ (2013). Using Drosophila larvae to study epidermal wound closure and inflammation. Methods Mol Biol 1037: 449–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHATTERJEE N, BOHMANN D (2012). A versatile φC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and NRF2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS One 7(4):e34063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHO N, KEYES L, JOHNSON E, HELLER J, RYNER L, KARIM F, KRASNOW M (2002). Developmental control of blood cell migration by the Drosophila VEGF pathway. Cell 108: 865–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLOMBELLI J, SOLON J (2013). Force communication in multicellular tissues addressed by laser nanosurgery. Cell Tissue Res 352: 133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOWLING J, YU QC, FUCHS E (1996). Beta4 integrin is required for hemidesmosome formation, cell adhesion and cell survival. J Cell Biol 134: 559–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUPONT S, MORSUT L, ARAGONA M, ENZO E, GIULITTI S, CORDENONSI M, ZANCONATO F, LE DIGABEL J, FORCATO M, BICCIATO S, ELVASSORE N, PICCOLO S (2011). Role of YAP/TAZ in mechanotransduction. Nature 474: 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMING SA, MARTIN P, TOMIC-CANIC M (2014). Wound repair and regeneration: Mechanisms, signaling, and translation. Sci Transl Med 6: 265sr6–265sr6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENYEDI B, NIETHAMMER P (2015). Mechanisms of epithelial wound detection. Trends Cell Biol 25: 398–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAZZIO TG, KOOPERBERG C, GOLDMARK JP, NEAL C, BASOM R, DELROW J, TSUKIYAMAT (2001). Widespread collaboration of Isw2 and Sin3-Rpd3 chromatin remodeling complexes in transcriptional repression. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6450–6460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERNANDEZ-GONZALEZ R, ZALLEN JA(2013). Wounded cells drive rapid epidermal repair in the early Drosophila embryo. Mol Biol Cell 24: 3227–3237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FESSLER LI, NELSON RE, FESSLER JH (1994). Drosophila extracellular matrix. Methods Enzymol 245: 271–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALKO MJ, KRASNOW MA (2004). Cellular and Genetic Analysis of Wound Healing in Drosophila Larvae. PLoS Biol 2: e239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALKO MJ, KRASNOW MA (2004). Cellular and genetic analysis of wound healing in Drosophila larvae. PLoS Biol 2: E239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GANGISHETTI U, VEERKAMP J, BEZDAN D, SCHWARZ H, LOHMANN I, MOUSSIAN B (2012). The transcription factor Grainy head and the steroid hormone ecdysone cooperate during differentiation of the skin of Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol Biol 21: 283–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEORGES-LABOUESSE E, MESSADDEQ N, YEHIA G, CADALBERT L, DIERICH A, LE MEUR M (1996). Absence of integrin alpha 6 leads to epidermolysis bullosa and neonatal death in mice. Nat Genet 13: 370–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARDEN N (2002). Signaling pathways directing the movement and fusion of epithelial sheets: Lessons from dorsal closure in Drosophila. Differentiation 70: 181–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARN HI-C, OGAWA R, HSU C-K, HUGHES MW, TANG M-J, CHUONG C-M (2017). The Tension Biology of Wound Healing. Exp Dermatol doi: 10.1111/exd.13460. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYES P, SOLON J (2017). Drosophila dorsal closure: An orchestra of forces to zip shut the embryo. Mech Dev 144: 2–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEINO TI, K??RP??NEN T, WAHLSTR??M G, PULKKINEN M, ERIKSSON U, ALI-TALO K, ROOS C (2001). The Drosophila VEGF receptor homolog is expressed in hemocytes. Mech Dev 109: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG J, WU S, BARRERA J, MATTHEWS K, PAN D (2005). The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell 122: 421–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGAKI T, PASTOR-PAREJA JC, AONUMA H, MIURA M, XU T (2009). Intrinsic Tumor Suppression and Epithelial Maintenance by Endocytic Activation of Eiger/TNF Signaling in Drosophila. Dev Cell 16: 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIMARU S, UEDA R, HINOHARAY, OHTANI M, HANAFUSA H(2004). PVR plays a critical role via JNK activation in thorax closure during Drosophila metamorphosis. EMBO J 23: 3984–3994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSSENS K, SUNG H-H, RØRTH P (2010). Direct detection of guidance receptor activity during border cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 7323–7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON HE, GOYAL Y, PANNUCCI NL, SCHÜPBACH T, SHVARTSMAN SY, TOETTCHER JE (2017). The Spatiotemporal Limits of Developmental Erk Signaling. Dev Cell 40: 185–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAKANJ P, MOUSSIAN B, GRÖNKE S, BUSTOS V, EMING SA, PARTRIDGE L, LEPTIN M (2016). Insulin and TOR signal in parallel through FOXO and S6K to promote epithelial wound healing. Nat Commun 7: 12972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAPLAN CD, MORRIS JR, WU CT, WINSTON F (2000). Spt5 and Spt6 are associated with active transcription and have characteristics of general elongation factors in D. melanogaster. Genes Dev 14: 2623–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEHLE J, BEUCHLE D, TREUHEIT S, CHRISTEN B, KENNISON J a, BIENZ M, MÜLLER J (1998). dMi-2, a hunchback-interacting protein that functions in poly-comb repression. Science 282: 1897–1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KENNISON JA, TAMKUN JW (1988). Dosage-dependent modifiers of polycomb and antennapedia mutations in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85: 8136–8140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM SE, COSTE B, CHADHA A, COOK B, PATAPOUTIAN A (2012). The role of Drosophila Piezo in mechanical nociception. Nature 483: 209–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOBB AB, ZULUETA-COARASA T, FERNANDEZ-GONZALEZ R (2017). Tension regulates myosin dynamics during Drosophila embryonic wound repair. J Cell Sci 130: 689–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KORENJAK M, TAYLOR-HARDING B, BINNÉ UK, SATTERLEE JS, STEVAUX O, AASLAND R, WHITE-COOPER H, DYSON N, BREHM A (2004). Native E2F/RBF complexes contain Mybinteracting proteins and repress transcription of developmentally controlled E2F target genes. Cell 119: 181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KWON YC, BAEK SH, LEE H, CHOE KM (2010). Nonmuscle myosin II localization is regulated by JNK during Drosophila larval wound healing. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 393: 656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAN CCE, LIU IH, FANG AH, WEN CH, WU CS(2008). Hyperglycaemic conditions decrease cultured keratinocyte mobility: Implications for impaired wound healing in patients with diabetes. Br J Dermatol 159: 1103–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE J-H, LEE C, PARK S-H, CHOE K-M (2017). Spatiotemporal regulation of cell fusion by JNK and JAK/STAT signaling during Drosophila wound healing. J Cell Sci 130: 1917–1928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEGATE KR, WICKSTRÖM SA, FÄSSLER R (2009). Genetic and cell biological analysis of integrin outside-in signaling. Genes Dev 23: 397–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LESCH C, JO J, WU Y, FISH GS, GALKO MJ (2010). A targeted UAS-RNAi screen in Drosophila larvae identifies wound closure genes regulating distinct cellular processes. Genetics 186: 943–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS PW, BEALL EL, FLEISCHER TC, GEORLETTE D, LINK AJ, BOTCHAN MR (2004). Identification of a Drosophila Myb-E2F2/RBF transcriptional repressor complex. Genes Dev 18: 2929–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIN AYT, PEARSON BJ (2014). Planarian yorkie/YAP functions to integrate adult stem cell proliferation, organ homeostasis and maintenance of axial patterning. Development 141: 1197–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU X, H LI, RAJURKAR M, LI Q, COTTON JL, OU J, ZHU LJ, GOEL HL, MERCURIO AM, PARK JS, DAVIS RJ, MAO J (2016). Tead and AP1 Coordinate Transcription and Motility. Cell Rep 14: 1169–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOSICK VP, FOX DT, SPRADLINGAC (2013). Polyploidization and cell fusion contribute to wound healing in the adult Drosophila epithelium. Curr Biol 23: 2224–2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUAN H, PEABODY NC, VINSON CR, WHITE BH (2006). Refined Spatial Manipula-tion of Neuronal Function by Combinatorial Restriction of Transgene Expression. Neuron 52: 425–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MÁRKUS R, KURUCZ É, RUS F, ANDÓ I (2005). Sterile wounding is a minimal and sufficient trigger for a cellular immune response in Drosophila melanogaster. Immunol Lett 101: 108–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCGUIRE SE, ROMAN G, DAVIS RL(2004). Gene expression systems in Drosophila: A synthesis of time and space. Trends Genet 20: 384–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEISTER M (2004). Blood cells of Drosophila: Cell lineages and role in host defence. Curr Opin Immunol 16: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOREIRA CGA, REGAN JC, ZAIDMAN-RÉMY A, JACINTO A, PRAG S (2011). Drosophila hemocyte migration: An in vivo assay for directional cell migration. Methods Mol Biol 769: 249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOREIRA S, STRAMER B, EVANS I, WOOD W, MARTIN P (2010). Prioritization of Competing Damage and Developmental Signals by Migrating Macrophages in the Drosophila Embryo. Curr Biol 20: 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORIKAWA Y, ZHANG M, HEALLEN T, LEACH J, TAO G, XIAO Y, BAI Y, LI W, WILLERSON JT, MARTIN JF (2015). Actin cytoskeletal remodeling with protrusion formation is essential for heart regeneration in Hippo-deficient mice. Sci Signal 8: ra41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORITA K, URABE K, MOROI Y, KOGA T, NAGAI R, HORIUCHI S, FURUE M (2005). Migration of keratinocytes is impaired on glycated collagen I. Wound Repair Regen 13: 93–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIETHAMMER P, GRABHER C, LOOK AT, MITCHISON TJ (2009). A tissue-scale gradient of hydrogen peroxide mediates rapid wound detection in zebrafish. Nature 459: 996–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NÜSSLEIN-VOLHARD C, WIESCHAUS E (1980). Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature 287: 795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKONKWO UA, DIPIETRO LA (2017). Diabetes and wound angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci 18(7). pii: E1419. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OSTERWALDER T, YOON KS, WHITE BH, KESHISHIAN H (2001). A conditional tissue-specific transgene expression system using inducible GAL4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 12596–12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARK S, GONZALEZ DG, GUIRAO B, BOUCHER JD, COCKBURN K, MARSH ED, MESA KR, BROWN S, ROMPOLAS P, HABERMAN AM, BELLAÏCHE Y, GRECO V (2017). Tissue-scale coordination of cellular behaviour promotes epidermal wound repair in live mice. Nat Cell Biol 19: 155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PAYRE F (2004). Genetic control of epidermis differentiation in Drosophila. Int J Dev Biol 48: 207–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEREIRA AM, TUDOR C, KANGER JS, SUBRAMANIAM V, MARTIN-BLANCO E (2011). Integrin-dependent activation of the jnk signaling pathway by mechanical stress. PLoS One 6(12): e26182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PINEDA CM, PARK S, MESA KR, WOLFEL M, GONZALEZ DG, HABERMAN AM, ROMPOLAS P, GRECO V (2015). Intravital imaging of hair follicle regeneration in the mouse. Nat Protoc 10: 1116–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAUSKOLB C, SUN S, SUN G, PAN Y, IRVINE KD (2014). Cytoskeletal tension inhibits Hippo signaling through an Ajuba-Warts complex. Cell 158: 143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAZZELL W, EVANS IR, MARTIN P, WOOD W (2013). Calcium flashes orchestrate the wound inflammatory response through duox activation and hydrogen peroxide release. Curr Biol 23: 424–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIESGO-ESCOVAR JR, JENNI M, FRITZ A, HAFEN E (1996). The Drosophila jun-N-terminal kinase is required for cell morphogenesis but not for DJun-dependent cell fate specification in the eye. Genes Dev 10: 2759–2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZKI TM, RIZKI RM (1992). Lamellocyte differentiation in Drosophila larvae parasitized by Leptopilina. Dev Comp Immunol 16: 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIZKI TM, RIZKI RM (1980). Properties of the larval hemocytes of Drosophila mela-nogaster. Experientia 36: 1223–1226. [Google Scholar]

- RIZKI TM, RIZKI RM, BELLOTTI RA (1985). Genetics of a Drosophila phenoloxidase. MGG Mol Gen Genet 201: 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROBBINS RM, GBUR SC, BEITEL GJ (2014). Non-canonical roles for Yorkie and Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis 1 in epithelial tube size control. PLoS One 9(7):e101609. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSSITER H (2004). Loss of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor AActivity in Murine Epidermal Keratinocytes Delays Wound Healing and Inhibits Tumor Formation. Cancer Res 64: 3508–3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHERFER C, KARLSSON C, LOSEVAO, BIDLAG, GOTOA, HAVEMANN J, DUSHAY MS, THEOPOLD U (2004). Isolation and characterization of hemolymph clotting factors in Drosophila melanogaster by a pullout method. Curr Biol 14: 625–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SIMPSON KJ, SELFORS LM, BUI J, REYNOLDS A, LEAKE D, KHVOROVA A, BRUGGE JS(2008). Identification of genes that regulate epithelial cell migration using an siRNA screening approach. Nat Cell Biol 10: 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLUSS HK, HAN Z, BARRETT T, GOBERDHAN DC, WILSON C, DAVIS RJ, IP YT (1996). A JNK signal transduction pathway that mediates morphogenesis and an immune response in Drosophila. Genes Dev 10: 2745–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH AV, ORR-WEAVER TL (1991). The regulation of the cell cycle during Drosophila embryogenesis: the transition to polyteny. Development 112: 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SONG Z, WANG R, YU D, WANG P, LU S, TIAN M, XIE T, HUANG F, YANG G (2008). [Impact of advanced glycosylation end products-modified human serum albumin on migration of epidermal keratinocytes: an in vitro experiment]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 88: 2690–2694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPAIN MM, CARUSO JA, SWAMINATHAN A, PILE LA (2010). Drosophila SIN3 isoforms interact with distinct proteins and have unique biological functions. J Biol Chem 285: 27457–27467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRINIVASAN N, GORDON O, AHRENS S, FRANZ A, DEDDOUCHE S, CHAKRA-VARTY P, PHILLIPS D, YUNUS AA, ROSEN MK, VALENTE RS, TEIXEIRA L, THOMPSON B, DIONNE MS, WOOD W, REIS E SOUSA C (2016). Actin is an evolutionarily-conserved damage-associated molecular pattern that signals tissue injury in Drosophila melanogaster. Elife 5 pii: e19662. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRINIVASAN S (2005). The Drosophila trithorax group protein Kismet facilitates an early step in transcriptional elongation by RNA Polymerase II. Development 132: 1623–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRINIVASAN S, DORIGHI KM, TAMKUN JW (2008). Drosophila Kismet regulates histone H3 lysine 27 methylation and early elongation by RNA polymerase II. PLoS Genet 4(10):e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEVENS LJ, PAGE-MCCAW A (2012). A secreted MMP is required for reepithelialization during wound healing. Mol Biol Cell 23: 1068–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STRAMER B, WOOD W, GALKO MJ, REDD MJ, JACINTO A, PARKHURST SM, MARTIN P (2005). Live imaging of wound inflammation in Drosophila embryos reveals key roles for small GTPases during in vivo cell migration. J Cell Biol 168: 567–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TSAI CR, ANDERSON AE, BURRA S, JO J, GALKO MJ (2017). Yorkie regulates epidermal wound healing in Drosophila larvae independently of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Dev Biol 427: 61–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UDAN RS, KANGO-SINGH M, NOLO R, TAO C, HALDER G (2003). Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat Cell Biol 5: 914–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VITORINO P, MEYER T (2008). Modular control of endothelial sheet migration. Genes Dev 22: 3268–3281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WAN P, WANG D, LUO J, CHU D, WANG H, ZHANG L, CHEN J (2013). Guidance receptor promotes the asymmetric distribution of exocyst and recycling endosome during collective cell migration. Development 140: 4797–4806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y, ANTUNES M, ANDERSON AE, KADRMAS JL, JACINTO A, GALKO MJ (2015). Integrin Adhesions Suppress Syncytium Formation in the Drosophila Larval Epidermis. Curr Biol 25: 2215–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y, YU A, YU FX (2017). The Hippo pathway in tissue homeostasis and regen-eration. Protein Cell 8: 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANGLER MF, YAMAMOTO S, BELLEN HJ (2015). Fruit flies in biomedical research. Genetics 199: 639–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WESTON CR, DAVIS RJ (2007). The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol 19: 142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD W, JACINTO A, GROSE R, WOOLNER S, GALE J, WILSON C, MARTIN P (2002). Wound healing recapitulates morphogenesis in Drosophila embryos. Nat Cell Biol 4: 907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU Y, BROCK AR, WANG Y, FUJITANI K, UEDA R, GALKO MJ (2009). A Blood-Borne PDGF/VEGF-like Ligand Initiates Wound-Induced Epidermal Cell Migration in Drosophila Larvae. Curr Biol 19: 1473–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YOUNG PE, RICHMAN AM, KETCHUM AS, KIEHART DP (1993). Morphogenesis in Drosophila requires nonmuscle myosin heavy chain function. Genes Dev 7: 29–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZEITLINGER J, BOHMANN D (1999). Thorax closure in Drosophila: involvement of Fos and the JNK pathway. Development 126: 3947–3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG C, PONUGOTI B, TIAN C, XU F, TARAPORE R, BATRES A, ALSADUN S, LIM J, DONG G, GRAVES DT(2015). FOXO1 differentially regulates both normal and diabetic wound healing. J Cell Biol 209: 289–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]