Abstract

Context

Schizophrenia is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, it is not clear if schizophrenia confers an inherent risk for glucose dysregulation in the absence of the effects of chronic illness and long-term treatment.

Objective

To conduct a meta-analysis examining if individuals with first-episode schizophrenia already exhibit alterations in glucose homeostasis compared with controls.

Data sources

The Embase, Medline and PsycINFO databases were systematically searched for studies examining measures of glucose homeostasis in drug-naïve individuals with first episode schizophrenia compared with controls.

Study Selection

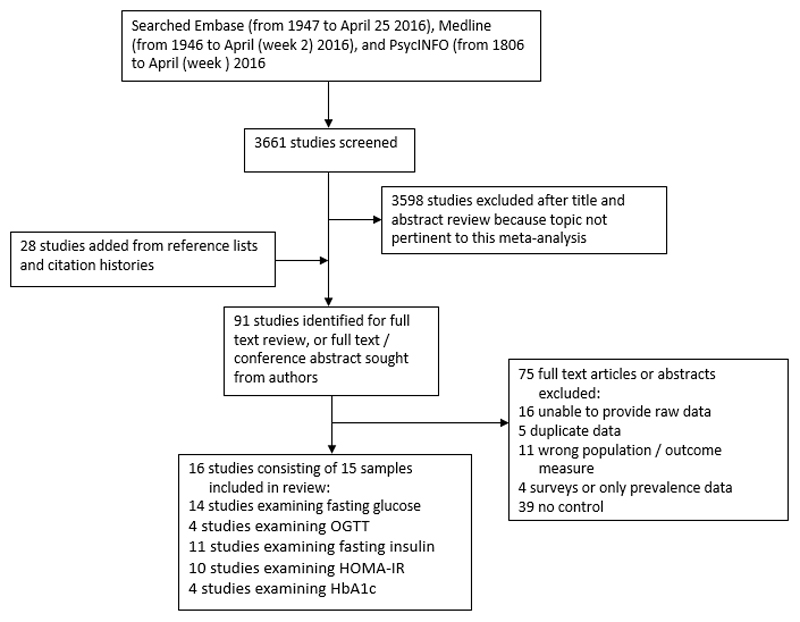

Of 3660 citations retrieved, 16 case control studies comprising 15 samples met inclusion criteria. The overall sample included 731 patients and 614 controls.

Data Extraction

Standardised mean differences in fasting plasma glucose, plasma glucose post-OGTT, fasting plasma insulin, insulin resistance, and HbA1c were calculated.

Data Synthesis

Fasting plasma glucose (g = 0.20 (95% CI 0.02 – 0.38, p = 0.027)), plasma glucose post-OGTT (g = 0.61 (95% CI 0.16 – 1.05, p = 0.007)), fasting plasma insulin (g = 0.41 (95% CI 0.09 – 0.72, p = 0.011)) and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (g = 0.34 (95% CI 0.14 – 0.54, p = 0.001)) were all significantly elevated in patients compared with controls. However, HbA1c levels (g = -0.08 (CI -0.34 – 0.18, p = 0.547) were not altered in patients compared with controls.

Conclusions

These findings show glucose homeostasis is altered from illness onset in schizophrenia, indicating patients are at increased risk of diabetes mellitus as a result. This has implications for the monitoring and treatment choice for patients with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Large scale epidemiological studies have established that people with schizophrenia die 15-30 years earlier than the general population, and that 60% or more of this premature mortality is due to non-CNS causes 1–5, predominantly cardiovascular6. Rates of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) are estimated to be 2-3 times higher in schizophrenia than in the general population, with a prevalence of 10-15% 7,8. Whilst antipsychotic use may contribute to this association, a link between schizophrenia and diabetes was already observed in the 19th century, long before the introduction of antipsychotics and in an era when diets did not have such a propensity to induce metabolic derangements 9,10. For over a decade there has been a drive to identify whether or not schizophrenia confers an inherent risk for the development of T2DM by investigating patients at illness onset, before the potentially confounding effects of chronic illness and long-term antipsychotic treatment. A number of studies have focussed on the presence or absence of T2DM in patient cohorts compared with controls. The results from meta-analyses of these studies examining the prevalence of T2DM in individuals with first episode psychosis and controls have found no significant differences between the two groups 11,12. However, there are two limitations with restricting analyses to an established diagnosis of T2DM. The first is that patients may be less likely to seek medical attention and so there is the risk of under-reporting. The second is that the development of T2DM takes time, with peak onset in middle age, and so may not have had time to develop in first episode patients. T2DM shows a progression through a period of insulin resistance, elevated insulin levels, and impaired glucose tolerance (‘pre-diabetes’) before the development of symptoms and a patient eventually receiving a diagnosis of T2DM. If a study’s outcome is whether or not criteria are met for a diagnosis of T2DM, significant alterations in glucose homeostasis between patient and control groups may be missed. In view of this we performed a meta-analysis of studies that focussed on measures of glucose control in individuals either at-risk for psychosis or in their first episode of psychosis. The aim of our meta-analysis was to test the hypothesis that individuals with first-episode schizophrenia exhibit alterations in glucose homeostasis compared with matched controls.

Methods

Selection Procedures

A systematic review was performed according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 13 and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) 14 guidelines. Two reviewers (TEP and KB) independently searched Medline (from 1946 to April (Week 2) 2016), Embase (from 1947 to April 25 2016) and PsycINFO (from 1806 to April (Week 2) 2016). The following keywords were used: ('schizophrenia' OR 'schizoaffective' OR 'psychosis' OR 'psychotic') AND ('early onset' OR 'first episode' OR 'at risk' OR 'ultra high risk' OR 'prodrome') AND 'medication' OR 'drug' OR 'antipsychotic' AND ('glucose' OR 'diabetes' OR 'type 2' OR 'prediabetes' OR 'intolerance' OR 'oral glucose tolerance test' OR 'OGTT' OR 'fasting' OR 'random' OR 'insulin' OR 'insulin resistance' OR 'HbA1c' OR 'homeosta*' OR 'HOMA-IR'). Studies in any language were considered, although all the included papers were in English. The search was complemented by hand searching of meta-analyses and review articles. Abstracts were screened and the full texts of relevant studies retrieved. Where full texts or abstracts were not available, authors were contacted and articles requested. TEP and KB selected the final studies for review and meta-analysis.

Selection Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: 1) a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) or International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, schizophreniform disorder, schizophrenia spectrum or psychotic disorder not otherwise specified OR an at-risk mental state for psychosis according to research criteria15,16; 2) first episode of illness (defined either as first treatment contact (inpatient or outpatient) or duration of illness up to 5 years following illness onset17); 3) antipsychotic naïve or minimal exposure (≤2 weeks antipsychotic treatment); 4) a healthy control group; 5) glucose homeostasis assessment including one or more of: fasting plasma glucose concentration, random plasma glucose concentration, the oral glucose tolerance test, percentage of haemoglobin A1 that is glycated (HbA1c), or insulin resistance as measured using the Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA). The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was required to meet the American Diabetic Association (ADA)18 and World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria19, namely serum glucose concentration measured 2-hours after a 75g oral glucose load following an overnight fast. Fasting serum glucose and insulin concentrations were defined as concentrations of either measure taken after an overnight fast in accordance with the ADA and WHO criteria. HOMA measurements of insulin resistance were required to follow either the original HOMA-IR formula20 (fasting plasma insulin (mU/L) x fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L)/22.5), or the updated HOMA2 formula21 via the University of Oxford Diabetic Trials Unit HOMA2 calculator v2.2 (www.dtu.ox.ac.uk).

Exclusion criteria were: 1) studies only assessing diagnosis of type I or type II diabetes mellitus; 2) patients with multiple episodes of schizophrenia; 3) chronic antipsychotic treatment (>2-weeks lifetime exposure); 4) substance or medication induced psychotic disorder; 5) physical co-morbidity that may impact on glucose homeostasis (e.g. prior diagnoses of type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus; other endocrine disorders (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome or acromegaly); pancreatitis; congenital disorders known to increase risk of T2DM (e.g. Klinefelter’s or Turner syndrome); and other systemic illnesses which may impact pancreatic function (e.g. cystic fibrosis, haemochromatosis or any chronic systemic inflammatory illness); 6) absence of measures in a healthy control group.

A small proportion of papers included patients with a limited duration of anti-psychotic use (2-weeks maximum). In these cases, authors were contacted to obtain access to data concerning those patients who were totally drug naïve. Where these data were not available, sensitivity analyses were performed examining only studies of patients who had absolutely no anti-psychotic exposure.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) identifies obesity as the strongest risk factor for T2DM from evidence based on studies across 188 countries22. In view of this, sensitivity analyses were performed examining studies where patients and controls were BMI matched to determine if failure to BMI match influenced results. BMI matching was either confirmed by review of study methodology, or by confirmation of no significant difference between mean BMI levels of patient and control groups (a two tailed p value less than 0·05 was deemed significant). The WHO recognises a number of other risk factors for T2DM relating to BMI, including unhealthy diet and physical inactivity22. Individuals with schizophrenia engage in significantly less physical exercise than controls, with even lower levels of physical activity observed in early stages of the illness23. In addition, the prodrome is associated with decreased physical activity and poor eating habits24,25. To address whether or not differences in diet and exercise between patient and control groups influenced results, sensitivity analyses examining groups matched for diet and exercise were performed. Diet and exercise matching was either confirmed by review of study methodology, or by confirmation of no significant difference between mean diet and exercise parameters of patient and control groups (a two tailed p value less than 0.05 was deemed significant). Non-modifiable risk factors for T2DM such as ethnicity are also recognised22, and in this context sensitivity analyses were also performed examining studies where participants were matched for ethnic background.

Recorded Variables

For every study, data was extracted according to the following model: author, year of publication, country, type of publication (i.e. prospective, cross-sectional, case-control, retrospective), matching criteria for patients and controls (confirmed by review of study methodology, or by confirmation of non-significance between mean parameter levels of patient and control groups (a two tailed p value less than 0·05 deemed significant)), whether or not patient groups were totally antipsychotic naïve (and if not, duration of treatment), and mean (with standard deviation) measure of glucose homeostasis in patient/control groups. Where there were multiple publications for the same data set, data was extracted from the study with the largest data set. Table 1 demonstrates this data extraction, with the exception of raw glucose homeostasis measurements (mean and standard deviations), which are documented in Supplementary Information. Also documented in Supplementary Information are those parameters of glucose homeostasis available in the studies described in table 1 but not included in meta-analysis along with the rationale behind exclusion.

Table 1.

Studies examining glucose homeostasis in first episode schizophrenia and related disorders meeting inclusion criteria. All studies used case-control designs. FG: fasting glucose; FI: fasting insulin; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test; HOMA-IR: homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin.

| Setting | Patient N | DSM diagnoses | Patient age, mean (SD) | Control N | Glucose Homeostasis Parameter | Anti-psychotic Status | Matching | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang et al. 201530 | China | 120 | Schizophrenia | 26.5 (6.3) | 31 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | All drug naive | BMI, age, ethnicity, sex, smoking |

| Petrikis et al., 201531 | Greece | 40 | Schizophrenia, shizophreniform, brief psychotic episode | 32.5 (9.8) | 40 | FG, HbA1c | All drug naïve | BMI, age, sex, smoking |

| Enez Darcin et al., 201532 | Turkey | 40 | Schizophrenia | 34.6 (1.1) | 70 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | All drug naïve | BMI, age, smoking |

| Dasgupta et al., 201033 | India | 30 | Schizophrenia | 32.5 (10.5) | 25 | FG, HOMA-IR | All drug naïve | BMI, age, ethnicity, sex |

| Arranz et al., 200434 | Spain | 50 | Schizophrenia | 25.2 (0.6) | 50 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | All drug naive | BMI, sex |

| Ryan et al., 200435 | UK/Ireland | 26 | Schizophrenia | 33.6 (13.5) | 26 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | All drug naïve | BMI, age, sex, smoking, diet, exercise |

| Venkatasubramanian et al., 200736 | India | 44 | Schizophrenia | 33.0 (7.7) | 44 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | All drug naive | BMI, age, sex |

| Cohn et al., 200637 | Canada | 10 | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder | 26.6 (8.7) | 10 | FG, FI | All drug naïve | BMI, age, smoking |

| Spelman et al., 200738 | Ireland | 38 | Schizophrenia | 25.2 (5.6) | 38 | FG, FI, OGTT, HOMA-IR, HbA1c | All drug naïve | Age, sex, smoking, ethnicity |

| Wani et al., 201539 | India | 50 | Schizophrenia | 25.4 (4.9) | 50 | FG, OGTT | All drug naïve | Age, sex |

| Saddichha et al., 200840 | India | 99 | Schizophrenia | 26.0 (5.5) | 51 | FG, OGTT | All drug naïve | Age, sex, diet, exercise |

| Garcia-Rizo et al., 201641 | Spain | 84 | Schizophrenia, brief psychotic disorder, psychosis not otherwise specified | 27.3 (5.5) | 98 | FG, FI, OGTT | Under 1 week of total antipsychotic use | BMI, age, sex |

| Sengupta et al., 200842 | Canada | 38 | Schizophrenia spectrum disorder | 25.4 (5.6) | 36 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR, HbA1c | Under 10 days total antipsychotic use | BMI, age, sex, ethnicity |

| Chen et al., 201343 | China | 49 | Schizophrenia | 26.8 (8.1) | 30 | FG, FI, HOMA-IR | Under 2 weeks of total antipsychotic use | BMI, age, sex, smoking |

| Sun et al., 201644 | China | 13 | Schizophrenia | 22.5 (3.8) | 15 | FI | All drug naïve | Age, sex |

| Fernandez-Egea et al., 200945 | Spain | 50 | Schizophrenia, brief psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, psychosis not otherwise specified | 29.4 (8.8) | 50 | HOMA-IR, HbA1c | Under 1 week of total antipsychotic use | BMI, age, sex, smoking |

Statistical analysis

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software version 3.0 (CMA, Bornstein, USA) was employed in all analyses. A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was deemed significant. A random-effects model was used in all analyses owing to an expectation of heterogeneity of data across studies. Standardised mean differences in glucose homeostasis measurements between patient and control cohorts were used as the effect size (ES), using Hedges’ adjusted g. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the ES was also calculated. The direction of the ES was positive if subjects with schizophrenia demonstrated higher values of glucose homeostatic measurements compared with controls. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q 26. Inconsistency across studies was assessed with the I2 statistic27, with an I2 of less than 25% deemed to have low heterogeneity, 25-75% medium heterogeneity, and greater than 75% high heterogeneity. Publication bias and selective reporting was assessed using Egger’s test of the intercept 28 (although this was not calculated when fewer than 10 studies were analysed as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration 29), and represented diagrammatically with funnel plots, again as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration 29 (plots documented in Supplementary Information).

Results

Retrieved Studies

After exclusion of studies reporting on overlapping data sets, 16 case control studies30–45 comprising 15 samples met inclusion criteria and were analysed. The search process is demonstrated in figure 1, and the final studies selected summarised in table 1. The overall sample included 731 patients and 614 controls.

Figure 1.

Search process. OGTT: Oral Glucose Tolerance Test; HOMA-IR: Homeostatic Model Assessment (Insulin Resistance); HbA1c: glycated haemoglobin.

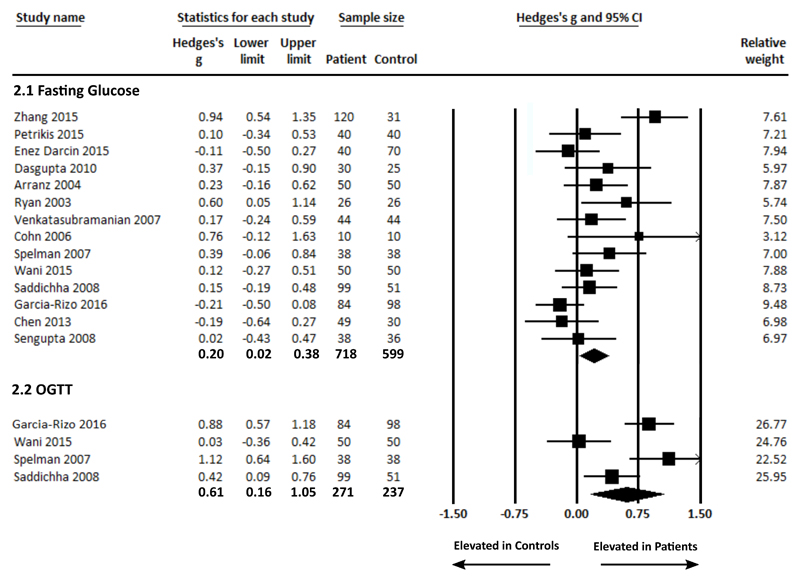

Fasting plasma glucose concentration

Fasting plasma glucose concentration in patients and controls was analysed using data from 15 studies, comprising 718 patients and 599 controls 30–43. Fasting plasma glucose concentration was significantly elevated in patients compared with controls (g = 0.20 (95% CI 0.02 – 0.38, p = 0.027) (figure 2.1). There was significant between-sample heterogeneity with an I2 of 58.29% (Q = 31.17, p = 0.003). Findings of Egger’s test (p = 0.068) suggested that publication bias was not significant. Restricting the analyses to purely antipsychotic naïve patients by excluding the 3 studies that included patients with up to 2-weeks of antipsychotic treatment 41–43 demonstrated that fasting plasma glucose concentration remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.30 (95% CI 0.11 – 0.48, p = 0.002). A sensitivity analysis examining studies where patients and controls were matched for diet and exercise parameters33,35–37,39,40 demonstrated that fasting plasma glucose concentration remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.25 (95% CI 0.07 – 0.43, p = 0.007) (Supplementary Information figure 1). However, after restricting the analyses to BMI matched studies30–37,41–43, there was no longer a significant difference in fasting plasma glucose concentration in patients compared with controls, g = 0.20 (95% CI -0.03 – 0.44, p = 0.083). A sensitivity analysis examining studies where patients and controls were matched for ethnicity30,35,38,40,41,43 demonstrated that fasting plasma glucose concentration remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.19 (95% CI 0.03 – 0.35 p = 0.017).

Figure 2.

Forest plots showing fasting glucose concentrations in patients with first episode schizophrenia and controls (figure 2.1: significant elevation in patients, ES: 0.20 p = 0.028); and glucose concentrations post-OGTT in patients with first episode schizophrenia and controls (figure 2.2: significant elevation in patients, ES: 0.61 p = 0.007).

Plasma glucose concentration post OGTT

Plasma glucose concentration post OGTT was analysed using data from 4 studies, comprising 271 patients and 237 controls 38–41. Plasma glucose concentration was significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.61 (95% CI 0.16 – 1.05, p = 0.007) (figure 2.2). Between-sample heterogeneity was significant with an I2 of 82.40% (Q = 17.05, p = 0.001). A sensitivity analysis examining studies where patients and controls were matched for ethnicity38,40,41 demonstrated that fasting plasma glucose concentration post OGTT remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.78 (95% CI 0.40 –1.17 p < 0.0001). In the context of low study numbers, sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of BMI, antipsychotics or diet/exercise were not performed.

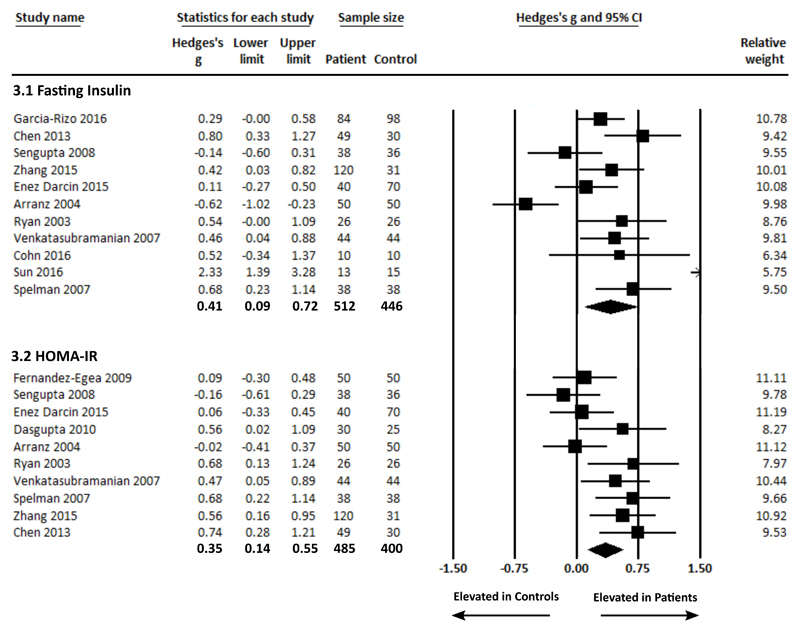

Fasting Plasma Insulin Concentration

Fasting plasma insulin concentration in patients and controls was analysed using data from 11 studies30,32,34–38,41–44, comprising 490 patients and 448 controls. Fasting plasma insulin concentration was significantly raised in patients compared with controls, g = 0.41 (95% CI 0.09 – 0.72, p = 0.011) (figure 3.1). Between-sample heterogeneity was significant with an I2 of 80.80% (Q = 52.09, p <0.0001). Findings of Egger’s test (p = 0.12) suggested that publication bias was not significant. Excluding the 3 studies that included patients with up to 2-weeks of antipsychotic treatment41–43, to restrict the analyses to purely antipsychotic naïve patients, demonstrated that fasting plasma insulin concentration remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.47 (95% CI 0.03 – 0.91, p = 0.035). Exclusion of 1 study that examined non-BMI matched patients and controls38 demonstrated that fasting plasma insulin concentration remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.38 (95% CI 0.04 – 0.72, p = 0.027). A sensitivity analysis examining studies where patients and controls were matched for ethnicity30,35,38,41,46 demonstrated that fasting insulin remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.49 (95% CI 0.30 – 0.68, p < 0.0001). In the context of low study numbers, a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of diet/exercise was not performed.

Figure 3.

Forest plots showing fasting insulin concentrations in patients with first episode schizophrenia and controls (figure 3.1: significant elevation in patients, ES: 0.41 p = 0.011); and insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in patients with first episode schizophrenia and controls (figure 3.2: significant elevation in patients, ES: 0.35 p = 0.001).

Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance as measured using the Homeostatic Model Assessment (HOMA-IR) in patients and controls was analysed using data from 10 studies30,32–36,38,42,43,45, comprising 485 patients and 400 controls. HOMA-IR was significantly raised in patients compared with controls, g = 0.35 (95% CI 0.14 – 0.55, p = 0.001) (figure 3.2). Between-sample heterogeneity was moderate but significant with an I2 of 55.40% (Q = 20.18, p = 0.017). Findings of Egger’s test (p = 0.10) suggested that publication bias was not significant. Excluding the 2 studies that included patients with up to 2-weeks of antipsychotic treatment42,45, to restrict the analyses to purely antipsychotic naïve patients, demonstrated that HOMA-IR remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.440 (95% CI 0.23 – 0.65, p < 0.0001). Exclusion of 1 study that examined non-BMI matched patients and controls38 demonstrated that HOMA-IR remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.31 (95% CI 0.09 – 0.53, p = 0.005). A sensitivity analysis examining studies where patients and controls were matched for ethnicity30,35,38,43 demonstrated that HOMA-IR remained significantly elevated in patients compared with controls, g = 0.66 (95% CI 0.43 – 0.88, p < 0.0001). In the context of low study numbers, a sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of diet/exercise was not performed.

Glycated Haemoglobin

HbA1c levels were analysed using data from 4 studies31,38,42,45, comprising 166 patients and 164 controls. HbA1c levels were not altered in patients compared with controls g = -0.08 (CI -0.34 – 0.18, p = 0.547) (Supplementary Information figure 2). Between-sample heterogeneity was moderate as indicated by an I2 of 31.50%, but a Q value of 4.38 (p = 0.223) suggested nonsignificant heterogeneity. Of these 4 studies, 2 studies examined patients with up to 2-weeks of antipsychotic use42,45, and 1 study examined non-BMI matched patients and controls38, and in the context of low study numbers sensitivity analyses were not performed.

Discussion

Our main findings are that patients with schizophrenia show raised fasting plasma glucose, reduced glucose tolerance, raised fasting plasma insulin, and raised insulin resistance at illness onset. With the exception of fasting glucose, these alterations were also seen when analyses were restricted to purely antipsychotic naïve and BMI matched samples. When analysis was restricted to diet/exercise matched samples, significance was maintained for raised fasting glucose in patients. All results remained significant when analyses were restricted to samples matched for ethnicity. No differences were demonstrated in HbA1c levels, although this result should be interpreted with caution owing to the small sample size used in this analysis. The results of our meta-analysis extend recent studies showing high rates of diabetes mellitus in patients with chronic schizophrenia by showing that altered glucose homeostasis is present from illness onset.

By focussing our analysis on patients with first episode schizophrenia, an attempt was made to limit the duration of secondary illness related factors known to impact glucose homeostasis. However, individuals in the prodrome and those with first episode schizophrenia already have poorer dietary habits, decreased physical activity, and an increased likelihood of smoking compared with age-matched controls23–25,47. Our search did not find any studies that examined glucose homeostasis in individuals at risk for developing psychosis that matched our inclusion criteria, and the duration of untreated psychosis was only documented in 5 out of the 16 studies analysed31,32,36,40,42. Since our definition of first episode schizophrenia was broad, ranging from first clinical contact to duration of illness up to 5 years following illness onset17, quantification of the duration of poor lifestyle habits for the overall sample was not possible, and the small number of studies that specifically documented duration of untreated illness prevented a meta-regression examining the influence of chronicity of illness on glucose homeostasis. This inability to fully control for lifestyle is a recognised limitation of the study. Although a sensitivity analysis examining studies where participants were matched for diet and exercise remained significant for raised fasting glucose in the patient cohort, there was no significant elevation in the BMI-matched sensitivity analysis. However, the sensitivity analyses of fasting insulin and insulin resistance showed significant dysregulation for these in the patient cohort BMI-matched to controls. Thus, differences in BMI, diet and exercise do not account for our findings, with the exception of BMI for fasting glucose.

Although all participants used in the meta-analysis were described as physically healthy with no illnesses that would impact glucose homeostasis, only 8 studies defined use of over-the-counter and prescription medication as a specific exclusion criterion32–35,38,40,41,45, and only 4 studies defined neuroleptic use (other than anti-psychotics) as an exclusion criterion33,34,36,37 (full details in Supplementary Information table 8). The potential use of medication other than antipsychotics that might disturb glucose homeostasis is a limitation of the meta-analysis. We also acknowledge that 4 of the 16 studies used in this meta-analysis analysed patients with schizophrenia as well as individuals with schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder and psychosis not otherwise specified31,41,42,45, which may contribute to heterogeneity in the sample. There was also variability in matching criteria for patients and controls, which is significant when one considers the effect of demographic variables such as gender, age and ethnicity on risk for T2DM22. Only 8 studies documented that participants were matched for ethnicity30,35,38,40–43,45, although our sensitivity analyses suggest that differences in ethnicities between groups were not responsible for the overarching findings of the meta-analysis. 1 study failed to match for gender32, and only 8 studies documented that participants were matched for smoking status30–32,35,37,38,43,45 (full details in Supplementary Information table 8). Other limitations of our study include between-sample heterogeneity in glucose homeostasis parameters tested, including the use of either the original HOMA equation20, or the HOMA2 equation21. Nevertheless, the random effects model we used is robust to heterogeneity.

In view of the findings of our meta-analysis, prospective studies investigating the impact of lifestyle factors on the glucose dysregulation seen in first episode patients would help determine the degree to which alterations are intrinsic to schizophrenia or the consequence of emerging symptoms. Longitudinal studies examining the efficacy of early interventions targeting a reduction in diabetic risk (both lifestyle based and pharmacological) in those individuals with schizophrenia who exhibit subtle early aberrances in glucose homeostasis would be useful.

Although the findings of this meta-analysis may in part reflect poorer lifestyle habits in patients compared with controls, other mechanisms may also contribute to the link between schizophrenia and altered glucose regulation. Both schizophrenia and T2DM are associated with early developmental risk factors such as low birth-weight, preterm birth, gestational diabetes and maternal malnutrition or obesity. The increased risk of impaired glucose homeostasis and schizophrenia in the context of early developmental insults is demonstrated by studies examining survivors from the 1944-45 Dutch famine and the 1959-61 Chinese famine. These studies demonstrate a relative risk of approximately 2 for developing schizophrenia in those conceived or in early gestation during a period of famine48–50, as well as an increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance later in life51. Stress and hypercortisolaemia may also contribute to this association between the two conditions, with antipsychotic naïve individuals with first episode psychosis exhibiting higher baseline cortisol levels and blunted cortisol wakening response compared with controls52. There is also evidence for a shared genetic vulnerability. Relatives of individuals with schizophrenia suffer higher rates of T2DM53–55, and genome wide association studies have revealed shared susceptibility genes between schizophrenia and T2DM56,57. Evidence to support the existence of pleiotropy between these genes has been demonstrated by a network analysis examining common signalling pathways involved in both schizophrenia and T2DM, with identification of proteins that play a role in calcium signalling, adipocytokine signalling, Akt signalling, and gamma-secretase mediated ErbB4 signalling57. Thus, dysfunction in common signalling pathways may drive central neurological dysfunction as well as peripheral metabolic dysfunction.

Regardless of the mechanism, this meta-analysis has demonstrated an association between schizophrenia and early derangements in glucose homeostasis. The OGTT is a more sensitive measure of abnormalities in glucose metabolism than fasting plasma glucose58,59, and is recognised by the WHO as the only means of identifying individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. The use of fasting plasma glucose measurement alone as a screen for T2DM results in approximately 30% of T2DM cases being missed60. Indeed, the OGTT has been recommended for screening and monitoring of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders owing to its increased sensitivity61. This lends further significance to the large effect size for raised glucose concentrations post-OGTT seen in patients with schizophrenia compared with controls. Although predominantly used in research, the HOMA-IR is well validated as a surrogate marker of insulin resistance, with its results correlating well with gold standard tests of insulin resistance such as the hyperinsulinaemic-euglycaemic clamp62. Therefore, the results from this analysis have major clinical implications. They indicate that individuals with schizophrenia present at the onset of illness with an already vulnerable phenotype for the development of T2DM. Given that a number of antipsychotic drugs may worsen glucose regulation63,64, there is thus a responsibility on the treating clinician to select an appropriate antipsychotic at an appropriate dose so as to limit the metabolic impact of treatment. Furthermore, it suggests that patients should be given education regarding diet and physical exercise, monitoring, and, where appropriate, early lifestyle and pharmacological interventions to combat the risk of progression to T2DM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

TP formulated the research question, performed the literature search, extracted and selected the articles, performed the primary analysis and wrote the report. KB extracted and selected the articles. CG extracted data. JD formulated the research question. SJ and OH wrote the report. TP had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This study was funded by Medical Research Council-UK (no. MC-A656-5QD30), Maudsley Charity (no. 666), Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and Wellcome Trust (no. 094849/Z/10/Z) grants to Professor Howes and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The funder had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. We thank Lin Lu, Su-Xia Lu, and Tony Cohn who made their data available to us.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

Professor Howes has received investigator-initiated research funding from and/or participated in advisory/speaker meetings organised by Astra-Zeneca, Autifony, BMS, Eli Lilly, Heptares, Jansenn, Lundbeck, Lyden-Delta, Otsuka, Servier, Sunovion, Rand and Roche. Neither Professor Howes nor his family have been employed by or have holdings/a financial stake in any biomedical company.

References

- 1.Beary M, Hodgson R, Wildgust HJ. A critical review of major mortality risk factors for all-cause mortality in first-episode schizophrenia: clinical and research implications. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2012;26(S5):52–61. doi: 10.1177/0269881112440512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crump C, Winkleby MA, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: a Swedish national cohort study. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):324–333. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoang U, Goldacre MJ, Stewart R. Avoidable mortality in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder in England. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2013;127(3):195–201. doi: 10.1111/acps.12045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laursen TM, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Excess early mortality in schizophrenia. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(2):116–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osby U, Correia N, Brandt L, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Mortality and causes of death in schizophrenia in Stockholm county, Sweden. Schizophr Res. 2000;45(1–2):21–28. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(99)00191-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DEH M, Schreurs V, Vancampfort D, VANW R. Metabolic syndrome in people with schizophrenia: a review. World Psychiatry. 2009;8(1):15–22. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2009.tb00199.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, van Winkel R, Yu W, De Hert M. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):306–318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maudsley H. The pathology of mind : a study of its distempers, deformities and disorders. London: Julian Friedman Publishers; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohen D. Diabetes mellitus and schizophrenia: historical perspective. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;47:S64–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.47.s64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vancampfort D, Correll CU, Galling B, et al. Diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and large scale meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):166–174. doi: 10.1002/wps.20309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, De Herdt A, Yu W, De Hert M. Is the prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities increased in early schizophrenia? A comparative meta-analysis of first episode, untreated and treated patients. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):295–305. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller TJ, McGlashan TH, Woods SW, et al. Symptom assessment in schizophrenic prodromal states. Psychiatr Q. 1999;70(4):273–287. doi: 10.1023/a:1022034115078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yung AR, Yuen HP, McGorry PD, et al. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005;39(11–12):964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitborde NJ, Srihari VH, Woods SW. Review of the operational definition for first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2009;3(4):259–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2009.00148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Expert Committee on the D, Classification of Diabetes M. Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: World Health Org; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy JC, Matthews DR, Hermans MP. Correct homeostasis model assessment (HOMA) evaluation uses the computer program. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(12):2191–2192. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.12.2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roglic G, World Health Organization . Global report on diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stubbs B, Firth J, Berry A, et al. How much physical activity do people with schizophrenia engage in? A systematic review, comparative meta-analysis and meta-regression. Schizophr Res. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juutinen J, Hakko H, Meyer-Rochow VB, Rasanen P, Timonen M, Study-70 Research G Body mass index (BMI) of drug-naive psychotic adolescents based on a population of adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Eur Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):521–526. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koivukangas J, Tammelin T, Kaakinen M, et al. Physical activity and fitness in adolescents at risk for psychosis within the Northern Finland 1986 Birth Cohort. Schizophr Res. 2010;116(2–3):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowden J, Tierney JF, Copas AJ, Burdett S. Quantifying, displaying and accounting for heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of RCTs using standard and generalised Q statistics. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration . Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang XY, Chen DC, Tan YL, et al. Glucose disturbances in first-episode drug-naive schizophrenia: Relationship to psychopathology. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;62:376–380. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petrikis P, Tigas S, Tzallas AT, Papadopoulos I, Skapinakis P, Mavreas V. Parameters of glucose and lipid metabolism at the fasted state in drug-naive first-episode patients with psychosis: Evidence for insulin resistance. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229(3):901–904. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Enez Darcin A, Yalcin Cavus S, Dilbaz N, Kaya H, Dogan E. Metabolic syndrome in drug-naive and drug-free patients with schizophrenia and in their siblings. Schizophr Res. 2015;166(1–3):201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dasgupta A, Singh OP, Rout JK, Saha T, Mandal S. Insulin resistance and metabolic profile in antipsychotic naive schizophrenia patients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(7):1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arranz B, Rosel P, Ramirez N, et al. Insulin resistance and increased leptin concentrations in noncompliant schizophrenia patients but not in antipsychotic-naive first-episode schizophrenia patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1335–1342. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryan MC, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired fasting glucose tolerance in first-episode, drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):284–289. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkatasubramanian G, Chittiprol S, Neelakantachar N, et al. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 abnormalities in antipsychotic-naive schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1557–1560. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07020233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohn TA, Remington G, Zipursky RB, Azad A, Connolly P, Wolever TM. Insulin resistance and adiponectin levels in drug-free patients with schizophrenia: A preliminary report. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(6):382–386. doi: 10.1177/070674370605100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spelman LM, Walsh PI, Sharifi N, Collins P, Thakore JH. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia. Diabet Med. 2007;24(5):481–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wani RA, Dar MA, Margoob MA, Rather YH, Haq I, Shah MS. Diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia, before and after antipsychotic treatment. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2015;6(1):17–22. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.143182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saddichha S, Manjunatha N, Ameen S, Akhtar S. Diabetes and schizophrenia - effect of disease or drug? Results from a randomized, double-blind, controlled prospective study in first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(5):342–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia-Rizo C, Kirkpatrick B, Fernandez-Egea E, Oliveira C, Bernardo M. Abnormal glycemic homeostasis at the onset of serious mental illnesses: A common pathway. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;67:70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sengupta S, Parrilla-Escobar MA, Klink R, et al. Are metabolic indices different between drug-naive first-episode psychosis patients and healthy controls? Schizophr Res. 2008;102(1–3):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen S, Broqueres-You D, Yang G, et al. Relationship between insulin resistance, dyslipidaemia and positive symptom in Chinese antipsychotic-naive first-episode patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(3):825–829. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun HQ, Li SX, Chen FB, et al. Diurnal neurobiological alterations after exposure to clozapine in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;64:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fernandez-Egea E, Bernardo M, Donner T, et al. Metabolic profile of antipsychotic-naive individuals with non-affective psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(5):434–438. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.052605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen DC, Du XD, Yin GZ, et al. Impaired glucose tolerance in first-episode drug-naive patients with schizophrenia: relationships with clinical phenotypes and cognitive deficits. Psychol Med. 2016:1–12. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716001902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myles N, Newall HD, Curtis J, Nielssen O, Shiers D, Large M. Tobacco use before, at, and after first-episode psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(4):468–475. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11r07222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clair D, Xu M, Wang P, et al. Rates of adult schizophrenia following prenatal exposure to the Chinese famine of 1959-1961. JAMA. 2005;294(5):557–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu MQ, Sun WS, Liu BX, et al. Prenatal malnutrition and adult schizophrenia: further evidence from the 1959-1961 Chinese famine. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(3):568–576. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Susser ES, Lin SP. Schizophrenia after prenatal exposure to the Dutch Hunger Winter of 1944-1945. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(12):983–988. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820120071010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ravelli AC, van der Meulen JH, Michels RP, et al. Glucose tolerance in adults after prenatal exposure to famine. Lancet. 1998;351(9097):173–177. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07244-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borges S, Gayer-Anderson C, Mondelli V. A systematic review of the activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in first episode psychosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(5):603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mukherjee S, Schnur DB, Reddy R. Family history of type 2 diabetes in schizophrenic patients. Lancet. 1989;1(8636):495. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Foley DL, Mackinnon A, Morgan VA, et al. Common familial risk factors for schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(5):488–494. doi: 10.1177/0004867415595715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Welie H, Derks EM, Verweij KH, de Valk HW, Kahn RS, Cahn W. The prevalence of diabetes mellitus is increased in relatives of patients with a non-affective psychotic disorder. Schizophr Res. 2013;143(2–3):354–357. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin PI, Shuldiner AR. Rethinking the genetic basis for comorbidity of schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes. Schizophr Res. 2010;123(2–3):234–243. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y, Li Z, Zhang M, Deng Y, Yi Z, Shi T. Exploring the pathogenetic association between schizophrenia and type 2 diabetes mellitus diseases based on pathway analysis. BMC Med Genomics. 2013;6(Suppl 1):S17. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-6-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tai ES, Lim SC, Tan BY, Chew SK, Heng D, Tan CE. Screening for diabetes mellitus--a two-step approach in individuals with impaired fasting glucose improves detection of those at risk of complications. Diabet Med. 2000;17(11):771–775. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.American Diabetes A. Standards of medical care in diabetes--2009. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(Suppl 1):S13–61. doi: 10.2337/dc09-S013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.World Health Organization. Definition and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus and Intermediate Hyperglycaemia: Report of a WHO/IDF Consultation. Geneva: World Health Org; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 61.van Winkel R, De Hert M, Van Eyck D, et al. Screening for diabetes and other metabolic abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: evaluation of incidence and screening methods. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(10):1493–1500. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wallace TM, Levy JC, Matthews DR. Use and abuse of HOMA modeling. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(6):1487–1495. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newcomer JW, Haupt DW, Fucetola R, et al. Abnormalities in glucose regulation during antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(4):337–345. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Howes OD, Bhatnagar A, Gaughran FP, Amiel SA, Murray RM, Pilowsky LS. A prospective study of impairment in glucose control caused by clozapine without changes in insulin resistance. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):361–363. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.