Abstract

Achieving host immune tolerance of allogeneic transplants represents the ultimate challenge in clinical transplantation. It has become clear that different cells and mechanisms participate in acquisition versus maintenance of allograft tolerance. Indeed, manipulations which prevent tolerance induction often fail to abrogate tolerance once it has been established. Hence, elucidation of the immunological mechanisms underlying maintenance of T cell tolerance to alloantigens is essential for the development of novel interventions that preserve a robust and long lasting state of allograft tolerance that relies on T cell deletion in addition to intra-graft suppression of inflammatory immune responses. In this review, we discuss some essential elements of the mechanisms involved in the maintenance of naturally occurring or experimentally induced allograft tolerance, including the newly described role of antigen cross-dressing mediated by extracellular vesicles.

Introduction

Achieving robust and durable host immune tolerance of allogeneic transplants is the ultimate goal in clinical transplantation. Allograft tolerance can be defined as a state during which a lack of destructive immunity to alloantigens results in the survival of an allogeneic tissue or organ without immunosuppression while preserving immunocompetence. Allograft tolerance takes place spontaneously under some physiological circumstances. Fetal maternal tolerance occurs naturally during pregnancy in eutherian mammals. Likewise, allogeneic tissues placed in immune privileged sites of the body such as the central nervous system, the eye and the testis are regularly accepted with no or minimal immune intervention (1–4). In addition, certain organ transplants are immune privileged in that they tend to promote protective immunity and become accepted with minimal or no immunosuppressive treatment (1–4). Immune privilege is mediated through physical barriers (placenta, blood brain barrier) as well as local and systemic suppression of pro-inflammatory alloimmune responses (3, 5) (4). On the other hand, in non-immune privileged settings, allograft tolerance can be achieved through manipulation of the host immune system or the transplant itself (4, 6). Whether allograft tolerance is spontaneous or induced, it is an active process initiated through recognition of alloantigens by host leukocytes in a fashion that promotes a protective rather than destructive type of immunity. Once this phase has been completed, it is likely that a series of mechanisms similar to self-antigen tolerance work to preserve the acquired state of tolerance to alloantigens. It is difficult to determine precisely when the transition between the induction and maintenance phases actually happens. In this article, we define the maintenance phase of allograft tolerance as the period beginning after interventions to actively induce tolerance cease and for the duration of time that the organ remains stably engrafted.

A variety of interventions that are able to prevent or impair the induction of tolerance often fail to cause rejection of accepted allografts. This suggests that tolerance acquisition and maintenance involve distinct mechanisms. It is now clear that tolerance of allogeneic tissues and organs, either spontaneous or induced, is acquired through multiple mechanisms involving deletion and suppression of pro-inflammatory alloreactive lymphocytes in host lymphoid organs and in the transplant itself. This process requires presentation of alloantigens, including MHC and minor histocompatibility antigens, by selected antigen presenting cells (APCs), which results in elimination or inactivation of corresponding lymphocytes. However, tolerance of allografts can be broken through the generation of new alloreactive lymphocytes or activation of undeleted but silent alloreactive ones.

Most of our knowledge of the physiological mechanisms underlying T cell tolerance comes from studies on autoimmunity in health and disease. Developing T cells undergo positive selection in the thymus’ cortex following TCR recognition of dominant self- peptides presented by self-MHC molecules (7). Therefore, the T cell repertoire is autoreactive by nature. Self-tolerance is initially achieved through thymic deletion of positively selected autoreactive T cells in the medulla of the thymus (central tolerance) (8). However, only 50% of autoreactive T cells displaying a high affinity for dominant determinants on autoantigens are actually eliminated through this process (9, 10). Indeed, most T cell clones recognizing dominant self-peptides with low affinity or cryptic self-peptides with high affinity escape negative selection, mature and reach the periphery (11). Nevertheless, under normal conditions, these cells do not cause autoimmune disorders. Maintenance of peripheral T cell tolerance of self-antigens involves a variety of cells and molecules acting through multiple mechanisms. It is not clear, however, whether peripheral autoreactive T cells are being continuously suppressed or if they just lack proper antigen presentation in the right environment. While important in preventing autoimmunity, one could also speculate that excessive central purging of the T cell repertoire or continuous suppression of lymphocytes in the periphery would jeopardize our ability to fight infections and cancer.

It is now clear that the mechanisms preserving self-tolerance vary for each organ. Likewise, it is conceivable that the mechanisms underlying allograft tolerance may differ depending upon the nature of the transplant but also vary with the host’s immune status and the tolerance protocol utilized. All of these elements are expected to govern the robustness of tolerance. The present paper avoids an exhaustive description of the cells and factors known to be involved in transplant tolerance. Instead, we discuss some key aspects of the mechanisms involved in the maintenance of allograft tolerance, including the emerging role of extracellular vesicles and antigen cross-dressing in this process.

Spontaneous tolerance of alloantigens and Fetal-maternal tolerance of alloantigens

P. Medawar originally described pregnancy as “nature’s allograft” (12). Indeed, despite its direct interaction with a semi-allogeneic organism, the maternal immune system does not normally reject the fetus (13). On the other hand, offspring become regularly tolerant to non-inherited maternal antigens (NIMA) during gestation and breast-feeding (14, 15). Such bi-directional tolerance relies on a multitude of mechanisms, both systemic and local. Here, we focus on the unique roles of regulatory T cells, HLA-G and other co- inhibitory molecules and describe some recent studies implicating trogocytosis and exosomes in fetal-maternal tolerance.

Studies performed during the 1970’s showed that multiparity maintained maternal tolerance of the fetus that was transferable by T cells (16). Such tolerance was associated with systemic hypo-responsiveness to paternal alloantigens, including H-Y (16–18). At this time, the phenomenon was attributed to T suppressor cells (Ts) whose nature and mechanisms of action were never elucidated. Revisiting this question in light of the characterization of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) revealed the recruitment of Tregs in the lymph nodes that drain the uterus during gestation (19). The most compelling demonstration of the role of Tregs in maintenance of maternal-fetal tolerance was provided in studies showing that depletion or inhibition of Tregs in pregnant mice was sufficient on its own to cause fetal resorption of allogeneic but not syngeneic fetuses (20). While these studies supported the role of CD4+ Foxp3+ Tregs in maintaining tolerance of allogeneic fetuses, their precise antigen specificity and their mechanisms of action are still elusive. Finally, Samstein et al. observed high abortion rates in mice lacking the conserved noncoding sequence 1 (CNS1), an intronic Foxp3 enhancer required for TGF-β induction of Foxp3 in peripheral Tregs (pTregs) but dispensable for the generation of thymic Tregs (tTregs) (21). Interestingly, these authors noted that the presence of the CNS1 correlated with the emergence of eutherian mammals, an observation suggesting that pTregs may have been selected through evolution to maintain maternal-fetal tolerance during pregnancy (21).

HLA-G and other co-inhibitory molecules

The placenta is a transient organ composed of fetal trophoblasts and the maternal decidua that is derived from the endometrium (22). Remarkably, at the beginning of pregnancy, 40% of maternal decidual cells are leukocytes comprised mostly of NK cells (70%), some T cells (20%) and a few DCs and macrophages (23). The proportion of T cells among decidual leukocytes increases gradually over the course of gestation. During this process, semi allogeneic fetal extravillous trophoblasts (EVT) invade the uterine mucosa and interact directly with decidual immune cells (DIC), including dNK, dT cells, and decidual stromal cells (DSC) without being rejected. This is due to sequential expression of coinhibitory molecules and their ligands by EVTs (PDL-1, CD200, B7-H3), DICs (PD-1/PD-L1, TIM-3, LAIR-1 and CEACAM1) and DSCs (TIM-3,Gal-9, PD-L1/2), which inhibit inflammatory responses while promoting TH2 and Treg protective immunity (24). In fact, dysregulation of these co-inhibitory signaling molecules during gestation abolishes fetal tolerance and causes abortion.

HLA-G MHC molecules also play a key role in the maintenance of feto-maternal tolerance (22). These atypical MHC molecules, expressed only on EVTs, protect fetal cells against attack by peripheral maternal NK cells (pNK) during pregnancy due to NK cells’ ubiquitous expression of HLA-G receptor KIR2DL4 (22, 25, 26). In addition, T cells expressing HLA-G receptor Ig-like transcript 2 (ILT2) (presumably transferred by monocytes) are susceptible to HLA-G signaling (27). Interestingly, recent studies show that HLA-G molecules mediate their tolerogenic effect through trogocytosis, a process by which immune cells acquire cell-surface proteins from another cell (28, 29). During pregnancy, HLA-G molecules are regularly transferred to decidual NK cells, macrophages and T cells (27, 30, 31). Remarkably, Foxp3- T cells cross-dressed with HLA-G inhibit T cell alloresponses as efficiently as classical Foxp3+ Tregs (32, 33). Therefore, expressions of co-inhibitory receptors and their ligands as well as HLA-G are key elements of the maintenance of immune maternal tolerance of the semi-allogeneic fetus during pregnancy. Interestingly, a recent study by Brugière et al. showed that expression of HLA-G by lung transplants in patients was associated with long-term graft acceptance (34).

Non inherited maternal antigens

Offspring are exposed to non-inherited maternal antigens (NIMA) during pregnancy and breast-feeding through passage of maternal cells into the fetus and neonates, respectively (35, 36). While NIMA are presented to developing T cells in the fetus’ thymus, most corresponding T cells become activated but are not deleted (37). In fact, adult mice and humans display some degree of T cell tolerance to NIMA, which results in extended survival of organ allografts expressing NIMA but not NIPA (non-inherited paternal antigens) or other control allogeneic MHC antigens (38–40). In adult offspring, maintenance of NIMA tolerance appears to rely mainly on two factors: the presence of Foxp3+ Tregs and persistence of very few but detectable maternal leukocytes, including hematopoietic stem cells (41, 42). In fact, a direct relationship between maternal microchimerism (< 1%) and maintenance of tolerance to NIMA has been found in adult mice (41, 42). A recent article from W. Burlingham’s laboratory brought some new insights into this question. His study provided evidence for the presence of maternal- derived extracellular nanovesicles (exosomes) displaying NIMA and APCs cross- dressed with NIMA in offspring (43). This phenomenon could amplify and spread NIMA presentation in primary and secondary lymphoid organs of the offspring, thus maintaining regulatory T immunity and tolerance to these alloantigens (44). This recent observation opens a new avenue of investigation regarding the role of exosomes and intercellular exchange of MHC and co-signaling molecules in the field of transplantation tolerance associated with hematopoietic microchimerism.

Immune privileged sites and transplants

Certain anatomical sites of the body are considered immune privileged in that they offer a highly favorable environment for allograft acceptance. In addition, certain organ allografts are immune privileged based on their ability to promote tolerogenic responses themselves and to be accepted with no or minimal recipient immunosuppression. In this section, we review some key mechanisms involved in maintenance of immune privilege and tolerance of allografts.

Corneal allografts

The mechanisms by which corneal allografts are recognized by T cells and undergo rejection follow unconventional rules (45, 46). In contrast to skin transplants, in the BALB/c-B6 fully allogeneic donor-recipient mouse combination, 50% of recipients spontaneously accept corneal allografts (47–51). These mice are actually tolerant as they always accept a second corneal graft from the same donor (51). As for the remaining 50% mice, they reject the corneal allograft slowly (5–7 weeks) and mount no direct CD4+ T cell response to donor MHC class II antigens (47, 48). On the other hand, CD8+ T cells activated directly against donor MHC class I are readily detected after corneal transplantation (48, 52). Although these CD8+ T cells produce γIFN, they do not display cytotoxic functions (47, 48). Actually, rejection in these mice is driven only by indirect CD4+ T cell recognition of minor antigens and not MHC disparities (49). The inability of corneal allografts to trigger a direct CD4+ T cell alloresponse was originally attributed to their lack of MHC class II+ APCs (51, 53). In fact, the central cornea is populated exclusively with highly immature and precursor-type APCs, which lack MHC class II expression under normal conditions. Some of these cells are immunoregulatory, and serve to maintain a quiescent environment under homeostatic conditions (54). These heterogeneous populations of bone marrow-derived APCs are comprised of epithelial Langerhans cells (LCs) and dendritic cells (DCs) in the anterior stroma, and macrophages in the posterior stroma (54–57). Interestingly, under inflammatory conditions, DCs from corneal transplants express MHC class II molecules as well as CD40, CD80, and CD86 coreceptors (54, 58). In this setting, these allografts trigger vigorous CD4+ T cell-mediated direct alloresponses and are rejected acutely (54, 58). Therefore, lack of immunogenicity of corneal DCs is not an intrinsic property of these APCs but is due to the microenvironment of the eye. This view is also supported by Niederkorn’s studies showing that heterotopic corneal allografts elicit bona fide cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses (59, 60). Likewise, we have shown that corneal allografts placed subcutaneously in mice trigger direct CD4+ T cell alloresponses and undergo acute rejection (47). Together, these studies demonstrate that intrinsic (intragraft APCs) and extrinsic (anatomic site of placement) factors tilt the balance toward rejection or acceptance of corneal allografts.

Liver allografts

Liver allografts are more susceptible to tolerance induction and maintenance than other solid organ allografts. In mice, these allografts are often accepted without requirement for immunosuppressive therapy (61). The immune privilege status of the liver is associated with the presence of resident professional and nonprofessional APCs, including DCs and hepatic macrophages (Kupffer cells) (62–64), liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) (65), hepatic stellate cells (66), and hepatocytes (67). Liver DCs are characterized by their immaturity (68, 69) and tolerogenic properties (70–72). For instance, liver myeloid DCs are known to reduce hepatic inflammation and fibrosis (73, 74) and dampen warm and “transplant-induced” ischemia-reperfusion injury (75, 76). These features of liver DCs are associated with their expression of programed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) (77), IL-10, (77, 78) FasL (79) the Notch ligand Jagged 1 (67) CD39 (76) and the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif–bearing transmembrane adaptor protein DNAX-activating protein of 12 kDa (DAP12) (80, 81). Furthermore, liver DCs suppress inflammatory T cell responses via expansion and activation of regulatory T cells, (82) thus promoting allograft survival (77, 83). Indeed, adoptive transfer of CD4+ Tregs from graft infiltrating cells into naïve recipients triggered long term survival of heart allografts (82). Alternatively, depletion of recipient CD4+CD25+ T cells using anti-CD25 mAbs led to acute liver allograft rejection (82). This was associated with a decreased ratio of Foxp3+ Treg: T effector cells, decreased Th2 cytokine IL-4 production, elevated production of the inflammatory cytokine IL-2 by graft- infiltrating T cells, and reduced apoptotic activity of graft-infiltrating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (82). In addition, systemic administration of IL-2 mitigated apoptosis among graft-infiltrating leukocytes, increased CTL activity, and induced acute liver graft rejection (84, 85).

Donor hematopoietic chimerism may be another essential aspect of tolerance maintenance in liver transplantation. Indeed, most donor passenger leukocytes migrate out of mouse liver grafts and are rapidly replaced by recipient leukocytes within hours of transplantation (77, 84). However, a small number of donor leukocytes, including DCs, macrophages, and lymphocytes persist for months in host lymphoid tissues (e.g. the spleen, mesenteric LN and thymus) (86) and to a lesser extent in the small bowel, skin, kidney, tongue, heart and lung (61, 86, 87). The contribution of such persistent hematopoietic microchimerism in the maintenance of liver allograft tolerance is still unknown. In fact, the concept that so few donor leukocytes could significantly impact the host alloimmune response has has been met with skepticism. However, recent studies of donor exosomes and donor antigen cross-dressing in transplantation could bring new insights into this realm (88). A recent study from Thomson’s laboratory supported the role of antigen cross-dressing in mouse spontaneous liver transplant tolerance. They reported that the majority of recipient DCs found in accepted liver allografts were cross- dressed with donor MHC class I expressing high levels of PD-L1 and IL-10 as compared with non–cross-dressed-DCs isolated from the graft (64). Concurrently, graft- infiltrating T cells displayed PD-1 and TIM-3, which are features of exhausted cells, on their cell surface (64). Therefore, as shown in NIMA tolerant mice, maintainance of liver transplant tolerance appears to involve continuous transfer of donor MHC from hematopoietic and liver parychymal or stromal cells and subsequent cross-dressing of DCs and/or other recipient APCs expressing co-inhibitory receptors and secreting anti- inflammatory cytokines.

Kidney allografts

Allogeneic kidneys are poorly immunogenic in laboratory mice and enjoy long term survival without any immunosuppression in certain donor-recipient strain combinations (89). Some studies suggest that Tregs are essential in maintenance of renal transplant tolerance in these mice. First, it was observed that tolerance maintenance correlated with the presence of intra-graft structures termed Treg-rich organized lymphoid structures or TOLS (90). Second, DT injections of Foxp3DTR mice, which had accepted their grafts for over 50 days, led to TOLS disruption and rapid rejection (90). These observations suggested that immune privilege and preservation of tolerance in this model relied on the presence of Tregs located in the allograft. However, it is important to keep in mind that DT-mediated depletion of Foxp3+ Treg cells in Foxp3DTR mice has been shown to cause rapid acute lymphopenia in secondary lymphoid organs and non- lymphoid tissues followed by massive homeostatic expansion/activation of pro- inflammatory T cells and subsequent systemic autoimmunity (91). Therefore, autoimmunity resulting from Treg depletion in normal mice might not be due to abrogation of continuous suppression of some self-reactive T cells but rather from systemic homeostatic T cell expansion and activation associated with severe lymphopenia (92, 93). This suggests that conclusions regarding the role of Tregs using Foxp3DTR mice should be taken with caution. However, it is important to note that in Foxp3DTR mice tolerant of an allogeneic kidney, no tissue damage was detected in the native kidney and no signs of systemic autoimmunity were observed upon DT injections (90). The observation that loss of tolerance via Treg depletion was restricted to the allograft suggests that it is not due to systemic autoimmunity. The view that allograft tolerance is maintained by Tregs within the transplant is also supported by a study by Graca et al. showing that tolerated skin allografts contained T cells that could recolonize a new host upon retransplantation (94). These cells were comprised of regulatory T cells, which were shown to prevent lymphocytes (in the second host) from rejecting fresh skin allografts from the same, but not a third party donor. Similarly, Li et al. reported that long-term acceptance of retransplanted lungs was associated with the presence of bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (BALT) exhibiting an accumulation of Foxp3+ cells (95). In this model, acceptance of retransplanted lungs was abrogated upon administration of anti-CD25 antibodies (95). Collectively, both these Treg depletion and retransplantation studies suggest that, while allograft tolerance is probably acquired in the host’s lymphoid organs, tolerance maintenance depends on regulatory T cells present in tertiary lymphoid organs (TLO) within the transplant. However, one should keep in mind that the formation of TLOs containing Tregs is regularly observed during inflammation in many tissues and in allografts undergoing rejection (96, 97). Nevertheless, the TOLS observed in accepted kidney transplants seem to differ from these TLOs by their lack of both high endothelial venules (HEV) and lymph node architecture with defined T and B cell zones (90).

It is generally assumed that intra-graft Tregs participating in allograft tolerance maintenance are recipient lymphocytes activated in draining lymphoid organs. However,the fact that many organs and tissues contain resident Tregs implies that certain allografts also contain Tregs at the time of transplantation. It is now clear that resident tissue specific Tregs, including tTregs and pTregs, such as visceral adipose tissue Tregs (VAT Tregs), skeletal muscle Tregs and colonic Tregs play a distinct role in controlling inflammatory cells locally in various organs (98). While these Tregs often display a distinct TCR repertoire, they function indistinguishably from typical lymphoid organ-derived Tregs in basic in vitro suppression assays (99). Such resident Treg populations are also found in other organs such as pancreas, and liver where they exhibit distinct phenotypic and functional characteristics. This raises the possibility that donor-derived Tregs and presumably other types of regulatory leukocytes present in allotransplants could influence the rejection process.

The concept that Tregs are necessary for maintenance of tolerance to self-antigens is based to a large extent upon a classical study by Sakaguchi’s laboratory using an anti- CD25 monoclonal antibody (100). In this study, it was observed that whole T cells depleted of CD25high T cells induced systemic autoimmune pathology upon adoptive transfer into very young nude mice while whole T cells did not. Indeed, adding back CD25high T cells to pathogenic T cells prior to their inoculation thwarted this effect (100). However, it is important to note that nude mice are “autoimmune prone”. Indeed, infusion of T cells into leukopenic animals is associated with systemic autoimmunity caused by homeostatic polyclonal expansion of pro-inflammatory T cells displaying an activated/memory effector phenotype (92, 93). Also, anti-CD25 Ab-depletion seemed to abolish self-tolerance in very young (< 3 weeks) mice but not in adults (100). This is a relevant issue since there is now plenty of evidence showing that ablation of Tregs in adult mice has no or little effect upon autoimmunity. Actually, there is growing evidence suggesting that tTregs are essential in self-tolerance primarily during early periods of life but not in adults (101). Finally, to our knowledge, anti-CD25 mAb depletion of Tregs triggering systemic autoimmunity in normal adult mice has not been documented.

In addition to the current Treg depletion procedures in mice whose limitations were described above, the role of Tregs in maintaining allograft tolerance is supported by observations showing that tolerance of alloantigens is transferrable from tolerant to naïve mice via adoptive transfer of Tregs. However, it is noteworthy that the vast majority of these experiments were done in Rag KO mice reconstituted with a mixture of T effector cells and Tregs. Therefore, while there is no doubt that Tregs play an important role in controlling harmful inflammatory immune responses in tissues, whether or not continuously activated Tregs are necessary and sufficient for the maintenance of tolerance to self-antigens and allografts remains to be proven. At first glance, the concept that self-tolerance is maintained through continuous suppression of potentially harmful autoreactive T cells in tissues is somewhat counterintuitive. In fact, maintaining our pro-inflammatory type 1 T cells (Th1/CT1) in a state of continuous suppression might be too detrimental to our ability to fight infections and cancer. It is more plausible that maintenance of self-tolerance relies on simple principles that in the absence of inflammation and associated danger signals, autoreactive T cells do not infiltrate tissues or that dominant self-peptides associated with autoimmune disorders are presented only by resting APCs in the absence of proper of costimulation signals and at levels insufficient to reach the threshold necessary to activate undeleted, low-affinity, self- reactive T cells. Therefore, Tregs are more likely to become activated and suppress locally activated autoreactive T cells in a given tissue only with inflammation. Unfortunately, current in vivo Treg depletion methods using anti-CD25 mAb injections or Foxp3DTR mice are not suitable to answer this question. Novel strategies, such as conditional expression models, will be required to elucidate the role of Tregs in sustaining tolerance to self- and alloantigens in vivo.

Induced tolerance of alloantigens

Tolerance of kidney allografts via short-term immunosuppression in swine

In miniature swine, short term treatment with high dose cyclosporine A (CyA) achieved indefinite survival of MHC class I disparate renal allografts (102). Acceptance of renal allografts was not a passive phenomenon in that these recipients subsequently accepted a second kidney or a heart allograft (with no cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV)) from an MHC-matched donor although only when it was placed within 3 months after removal of the first transplant (103–105). In contrast, isolated heart transplants performed under identical conditions were regularly rejected and developed CAV (106). In this model, the contributions of factors within the graft and in the peripheral blood were assessed for their relative roles in the maintenance of tolerance. In one set of experiments, recipients of renal allografts were treated with donor-specific transfusion (DST) followed by leukapheresis in order to remove peripheral leukocytes, including putative regulatory T cells (107–109). Next, control recipients were followed clinically and 10 animals received a second, donor-MHC-matched kidney. None of the control animals showed evidence of rejection, while 8 of 10 re-transplanted animals developed either rejection crises or full rejection of the second transplant (107–109). In vitro assays confirmed that the removed leukocytes were suppressive and that CD4+ Foxp3+ Treg reconstitution in blood and kidney grafts correlated with return to normal renal function in animals experiencing transient rejection crises (107–109). In all animals, whether treated with CyA or not, lymphoid infiltrates were present in renal allografts by day 8 post-transplantation. IL-2 injection of recipients during acquisition of tolerance (day 8–10) was shown to induce IL-2R expression on graft infiltrating cells and cause rejection, suggesting that the infiltrates present before IL-2 administration were capable of causing rejection once T cell help was provided (103). In contrast, treatment with IL-2 did not abrogate long-term tolerance (103). Thus, limitation of T cell help at the time of first exposure to Ag in this model appears to be required to prevent rejection during the development of active tolerance. In contrast, once established, maintenance of tolerance did not necessitate continuous limitation of T cell help, suggesting that maintenance was mediated by the loss, inactivation, or suppression of the cells capable of causing rejection. Next, the influence of an indirect alloresponse to donor MHC class I peptides in the establishment and maintenance of tolerance was investigated (110). Induction of an inflammatory indirect alloresponse via immunization of recipients with donor MHC class I peptides prevented tolerance induction but it did not abrogate an already established tolerance (110). Interestingly, in contrast to their naïve counterparts, tolerant swine failed to mount allospecific DTH and T cell proliferative responses upon a donor MHC peptide immunization (110). This suggested that CD4+ T cells recognizing alloantigens indirectly had been tolerized in these animals. Altogether, these data indicated that components of accepted kidney grafts as well as peripheral regulatory components both contribute to the tolerogenic environment required for maintenance of allograft tolerance.

The aforementioned studies in kidney transplantation show that immune privilege and donor-specific transplant tolerance can occur naturally (mice) or be acquired through immune intervention (111). The mechanisms by which kidney allografts were accepted and conferred tolerance of a non-immune privileged organ (heart) are still unclear. In the kidney only model, thymectomy upon a tolerant recipient abolished induction but not maintenance of tolerance (112, 113). This suggested that the kidney mediated its initial tolerogenic effects through a mechanism involving alloantigen presentation in the recipient thymus. However, one should keep in mind that disruption of thymic functions either by thymectomy or irradiation results in autoimmunity (114, 115). Thymectomy causes lymphopenia due to impaired thymic output of new T cells and compromises thymic Treg cell development. Both a lymphopenic environment and a Treg cell deficiency are known to elicit autoimmune disorders in T cell deficient mice infused with naive T cells (92, 93, 100). Consequently, conclusions made from experiments involving a recipient thymectomy can be misleading.

Donor hematopoietic chimerism in laboratory rodents

Seminal studies by R. Owen and P. Medawar have demonstrated that donor hematopoietic chimerism achieved naturally in fetuses or experimentally in neonates is associated with durable and robust tolerance of alloantigens (116, 117). Subsequently, this phenomenon was reproduced in adults via lymphoid irradiation and reconstitution with allogeneic hematopoietic cells (116, 118, 119). Later, studies from Sachs and Sykes’ laboratories showed that induction of mixed chimerism, in which both donor and host stem cells contribute to hematopoiesis, reliably achieves tolerance of allogeneic organ and skin allografts in laboratory mice (120–122). In rodents, induction of allograft tolerance was associated with initial unresponsiveness of alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, presumably via anergy (123–125). On the other hand, maintenance of tolerance in mixed chimeric mice was reported to rely primarily on elimination of donor-reactive T cells (125). Indeed, rejection was elicited upon infusion of chimeric mice with recipient type lymphocytes from a naïve mouse (125). In addition, Khan et al. showed that maintenance of tolerance was dependent upon the continuous presence of donor antigens in the recipient’s thymus but not in the peripheral immune system, arguing against anergy or suppression as mechanisms of tolerance (126). However, it is important to keep in mind that T cell clonal elimination in mixed chimeric mice was evaluated with T cells from TCR transgenic mice and T cells directed against super- antigens, which recognize their antigen determinants with very high affinity. At the same time, it is now clear that negative selection eliminates only a limited number of autoreactive cells in normal mice with polyclonal T cells. Indeed, studies by van Meerwijk et al. showed that, in bone marrow chimeras, only one-half to two-third of the thymocytes able to undergo positive selection die before full maturation due to negative selection (10). This has been recently confirmed by a report from Bendelac’s laboratory showing that only half of developing autoreactive T cells undergoes clonal elimination during thymic selection (9). At first glance, one should assume that the same rules apply to the central deletion of alloreactive T cells following mixed hematopoietic induction. However, it is known that alloreactive T cells recognize allogeneic MHC proteins (through the direct pathway) with particularly high affinity based upon the high determinant density and multiple binary complex concepts (127, 128). Based on this, it is conceivable that thymic elimination of alloreactive T cells in mixed chimeras may be more complete than that of self-reactive T cells in normal mice. However, it is unlikely to pertain to T cells recognizing allogeneic MHC indirectly, i.e. in the form of peptides presented by self-MHC, for which antigen recognition follows traditional rules (129, 130). Thus, it is possible that peripheral deletion of indirect alloreactive T cells resulting from T cell exhaustion or anergy may represent an essential element of tolerance via stable mixed chimerism in mice. Indeed, different studies from M. Sykes’s laboratory involving thymectomy, anti-donor antibody injections and recipient lymphocyte infusions (RLI) showed that sustained high levels of donor hematopoietic chimerism ensured life-long central and peripheral deletion of donor reactive T cells, apparently obviating the need for peripheral alloantigen and regulatory mechanisms in the maintenance of tolerance (125). However, in situations where high levels of donor chimerism could not be established or sustained, control of alloimmune responsiveness might be achieved through distinct mechanisms, including regulatory T cells. One relevant study on this topic is from Joffre et al. who used Tregs to promote mixed chimerism (131). When the Tregs were specific for a fully MHC-mismatched donor, acute but not chronic donor skin graft rejection was prevented, presumably due to failure to tolerize T cells recognizing alloantigens in an indirect fashion (131). Alternatively, Tregs generated against a haploidentical donor suppressed both direct and indirect alloresponses and prevented both types of rejection (131). Likewise, a recent study by Mahr et al. reported that, in the absence of irradiation and leukocyte depletion, mixed chimerism was inducible via infusion of Tregs at the time of bone marrow transplantation (132). In this setting, permanent but low levels of donor chimerism were achieved (2–4%) and tolerance was maintained through peripheral mechanisms involving Tregs, regulatory NK cells and the delivery of co-inhibitory signals to pro-inflammatory T cells (132). Altogether, this suggests that the relative contribution of central deletion and peripheral suppression of alloreactive T cells in tolerant mixed chimeric mice might vary depending upon several factors, including the conditioning of recipients and the nature, level and duration of hematopoietic chimerism. It also supports the view that certain types of alloimmunity are suppressed through clonal deletion of corresponding T cells while others are controlled by peripheral mechanisms. This hypothesis is substantiated by a number of studies. First, original studies from Ildstad and Sachs showed the onset of chronic rejection of skin allografts in some mice despite persistent mixed chimerism where the donor differs from the recipient by multiple minor antigens (133). Another study by Russell et al. showed that cardiac allografts placed in mixed chimeric mice, which had accepted skin allografts, underwent chronic rejection, characterized by cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) (134). In chimeric recipients treated with anti-CD4/8 mAbs the prevalence of CAV was greatly reduced, while anti-NK1.1 mAb alone had no effect on incidence of CAV (135). Finally, Shinoda et al. recently showed that in tolerant mice with stable hematopoietic macrochimerism, depletion of Tregs (using FoxP3DTR mice) did not cause loss of chimerism, suggesting that T cell tolerance of allogeneic MHC antigens was maintained through deletional mechanisms (136). However, in these mice, Treg depletion led to rejection of skin and heart allografts which had been accepted for more than 50 days (136). This indicated that Tregs might be involved in maintenance of tolerance of some allo-peptides or skin graft specific antigens presented indirectly. Collectively, these studies support the view that, in contrast to T cells recognizing donor MHC directly, T cells recognizing allo-peptides in an indirect fashion and T cells specific for graft tissue specific antigens are not deleted in mixed chimeric mice. These undeleted T cells are likely to remain silent under normal conditions but become activated in an inflammatory environment and cause chronic allograft rejection.

Donor hematopoietic chimerism in non-human primates

In non-human primates, mixed chimerism procedures resembling those developed in mice achieved only low level transient donor hematopoietic chimerism (1–2 months), likely due to the presence of pre-existing alloreactive memory T cells (137–139). Nevertheless, donor bone marrow transplantation along with non-myeloablative conditioning and short-term ATG, anti-CD40L mAbs and CyA treatments achieved survival of kidney allografts for years in over 60% of recipients (139{Kawai, 1995 #2851). In this setting, long-term allograft survival was achieved primarily in recipients displaying low frequencies of donor reactive memory T cells pre-transplantation (137–139). These animals were tolerant in that they showed prolonged skin allografts from the same but not a third party donor (139, 140). In addition, T cells isolated from these monkeys failed to proliferate and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines following direct stimulation with donor APCs in vitro (MLR). However, anti-donor alloresponse was fully restored upon addition of exogenous IL-2 cytokine to the MLR cultures, which demonstrates that some proinflammatory donor-specific T cells persist, presumably in an anergic state in tolerant monkeys (141). The fact that tolerance was maintained for years after chimerism had been lost suggested that, unlike mice, it relied primarily on peripheral regulatory mechanisms rather than thymic deletion. Supporting this view, a study by Hotta et al. showed that kidney allograft survival and a lack of inflammatory alloimmunity was associated with the presence of CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells proliferating only when co-cultured with donor-derived APCs (142). In the same study, some evidence was provided indicating that these cells were pTregs converted from conventional allospecific T cells (142).

A sizable proportion of the monkeys that had accepted renal transplants for more than 2 years ultimately produced donor specific antibodies (DSA) and rejected their allograft in a chronic fashion (143–145). Chronic allograft rejection and loss of B cell tolerance was associated with the development of an indirect alloresponse by T cells (145). Therefore, as suggested by rodent studies, it is plausible that the mechanisms underlying tolerance maintenance of T cells recognizing allogeneic MHC molecules directly or indirectly are different. It is also possible that indirect alloresponses observed during loss of tolerance in monkeys were specific for minor histocompatibility antigens or tissue-specific antigens instead of donor MHC peptides.

Long-term survival of kidney allografts in monkeys displaying transient mixed hematopoietic chimerism apparently relied on peripheral regulation rather than deletion of allospecific proinflammatory T cells. This implied that, in this non-human primate model, upsetting the balance between inflammatory and regulatory alloimmunity could abolish tolerance and trigger the rejection of previously accepted renal allografts. This is supported by a study examining the effect of IL-2 injections in monkeys treated with a mixed chimerism protocol and which had accepted a kidney allograft for periods of 1–10 years after withdrawal of immunosuppression (141). IL-2 injections resulted in immediate rejection of renal transplants and were associated with an expansion and reactivation of alloreactive pro-inflammatory CD8+ effector memory T cells in the host’s lymphoid organs and in the graft (141). Indeed, abrogation of tolerance was prevented by anti-CD8 antibody treatment (141). Interestingly, this phenomenon was reversible in that cessation of IL-2 administration aborted the rejection process and restored normal kidney graft function (141). Therefore, while allosensitization can cause rejection in tolerant recipients, tolerance may be restored once inflammation subsides, suggesting that its maintenance involves anamnestic regulatory mechanisms.

Finally, it is noteworthy that in patients treated at MGH with similar mixed chimerism protocols, observations were consistent with a role for a suppressive tolerance mechanism at 6 months to 1 year while at later time points post-transplantation (≥ 18 months) no evidence for a regulatory mechanism was found. Alternatively, in four patients (3 of whom became tolerant) Sykes et al were able to identify and track donor reactive T-cells (through high throughput sequencing of the TCR β chain CDR3 region) prior to transplant and post-transplantation (146). They found post-transplant reductions in donor-reactive T cells clones after transplantation in the three tolerant patients (146). This reduction of donor reactive T cells was not observed in the patient who experienced rejection, or in two patients on maintenance immunosuppression (146).

Donor leukocyte administration along with antibody treatments targeting T cells or molecules mediating T cell activation

Administration of allogeneic leukocytes along with short-term recipient T cell depletion or inhibition can achieve long-term survival of certain organ allografts in mice (6, 68, 147–153). This involves an active tolerogenic process given that recipients accept a second allograft from the same but not another donor. Unlike hematopoietic chimerism, transplant tolerance in this setting is thought to rely on peripheral T cell suppression rather than central clonal deletion (6, 154). A large variety of cells and molecules from both innate and adaptive immune systems have been documented for their role in peripheral suppression of alloreactive inflammatory responses involved in transplant rejection. These include different populations of T and B lymphocytes with regulatory activity such as CD4+ T cells (155–158), CD8+ T cells (159–162), CD4–CD8– T cells (163), natural killer T cells (NKT cells) (164, 165) and γδ T cells (166) as well as regulatory B cells (167–169). It is possible that different cells and mechanisms participate in acquisition versus maintenance of tolerance. This is supported by studies showing that manipulations, which prevented tolerance induction, failed to abrogate tolerance once it had been established. For instance, Jiang et al. showed that pre- transplant depletion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells (with anti-CD25 mAbs) prevented tolerance of cardiac allografts achieved through costimulation blockade in mice (170). However, Treg depletion performed 30 days post-transplantation did not affect tolerance (171). Also, infections of mice pre-transplantation often prevented tolerance induction via DST and costimulation blockade by causing the differentiation/expansion of donor- reactive memory T cells (via heterologous immunity) (172–176). However, viral infections, including infections of graft tissue itself, did not break tolerance (176). Likewise, S. aureus infections and TLR agonists given during the maintenance phase of tolerance did not trigger allograft rejection (171). Collectively, these studies showed that infections are detrimental to induction but not maintenance of allograft tolerance. However, this is not a general principle since microbial infections have often been shown to precede loss of graft tolerance (172, 177, 178). Studies from A. Chong and M- L Alegre’s laboratories showed that cardiac allograft tolerance achieved via DST and anti-CD40L mAb treatment was abrogated following infection with listeria monocytogenes (LM) bacteria (179). Apparently, while alloreactive T cells mediated rejection, no cross-reactivity between alloantigens and bacterial antigens was detected. On the other hand, breakdown of tolerance was dependent upon IL-6 cytokine and cell signaling via type I interferon receptors. Actually, IL-6 and IFNβ administration abrogated tolerance in the absence of LM infection (179). This suggests that systemic inflammation could upset the balance between regulatory and inflammatory immunity thus abrogating transplant tolerance. Surprisingly, in mice for which tolerance had been broken, a second allogeneic heart placed after the bacteria had been cleared (14 days) became spontaneously accepted instead of undergoing accelerated rejection (180). This implied that upon subsidence of inflammation, self-tolerance had been reinstated. Another study by Schietinger et al. showed that while tolerant T cells proliferated and became functional under lymphopenic conditions, tolerance was reimposed upon lymphorepletion even in the absence of tolerogen (181). Remarkably, genetic analyses revealed that tolerant T cells displayed a tolerance specific gene profile temporarily overridden under lymphopenic conditions but inevitably reimposed, which suggests epigenetic regulation (181). It is plausible there are similar principles involved in maintenance and restoration of allograft tolerance.

The aforementioned studies suggest that activation of cells of the innate immune system can cause loss of allograft tolerance. However, as mentioned earlier regarding fetal maternal tolerance, certain innate cells exert regulatory functions required for tolerance maintenance in transplantation. For instance, tolerance of allografts in recipients treated with anti-CD28 mAbs or DST was abolished by NK cell depletion (182, 183). The tolerogenic properties of some activated NK cells did not seem to rely on their ability to sense the absence of self-MHC class I molecules on allogeneic cells (182, 183). On the other hand, perforin expression by NK cells was apparently required, which implies that NK cell tolerogenicity is associated with their cytotoxic functions (183–185). In another study by X. Li’s group, NK cells were found to maintain transplant tolerance by killing donor APCs (186). These studies suggest that NK cells, like DCs and T cells, have dual roles in transplantation, either promoting tolerance or rejection, depending on the organ/tissue transplanted and the inflammatory milieu surrounding the allograft at the time of transplantation (187–190).

Along with the above studies, a recent report by M. Miller et al. al showed that robustness of tolerance to cardiac allografts in mice treated with DST and anti-CD40L Abs requires combined sustained low frequencies of alloreactive T cells, PD-L1 signals and the presence of CD25+ Tregs (191). Therefore, maintenance of a stable state of robust tolerance induced experimentally relies on synergy between different cells and molecules of both the adaptive and innate immune systems cooperating via various mechanisms.

Concluding remarks

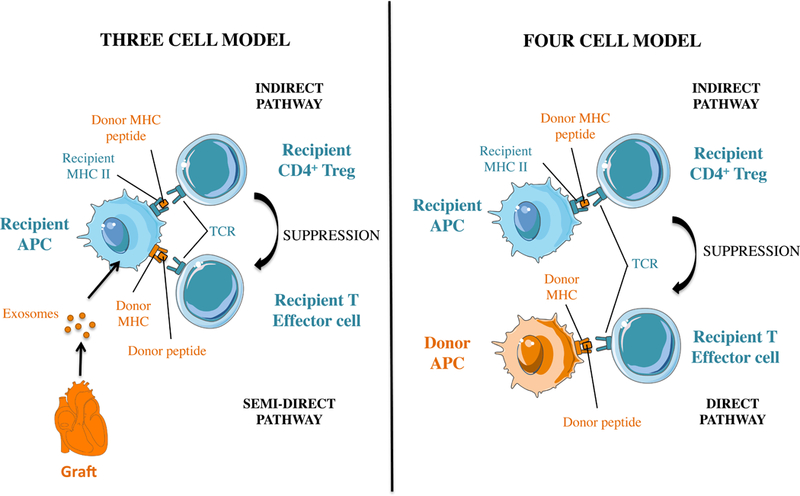

Currently, hematopoietic chimerism in which the host and donor immune systems coexist represents the most efficient mechanism to ensure robust tolerance to alloantigens. This is achieved regularly and naturally during pregnancy. Likewise, spontaneous tolerance of certain allografts associated with immune privilege relies on the relationships between graft leukocytes and the host immune system. In all cases, tolerance of allogeneic organs is maintained by a series of cells and molecules of both innate and adaptive immune systems, which act locally in the graft and systemically in the host’s primary and secondary lymphoid tissues. Similar forms of tolerance can be achieved experimentally in laboratory rodents via administration of donor cells (hematopoietic stem cells or donor specific transfusion (DST)) in combination with short- term depletion or inhibition of recipient’s peripheral lymphocytes. In mice, stable mixed hematopoietic chimerism achieved via bone marrow transplantation achieves a robust form of tolerance, relying in part on deletion of host anti-donor T cells. However, the presence of pre-existing donor-reactive memory in humans represents a major hurdle to successful translation of this strategy in clinical transplantation. In the case of DST + antibody treatments, tolerance appears to be maintained through local and presumably systemic suppression of alloreactive T cells. In both situations, it is clear that once donor passenger leukocytes have been eliminated, a major challenge will be to maintain tolerance of T cells recognizing donor antigens in an indirect fashion. This could involve Treg activation by recipient APCs, which become cross-dressed with donor MHC acquired from the continuous release of nanovesicles (exosomes) by the allograft (Figure 1). Studies from our and other laboratories are underway to evaluate the role of this newly identified phenomenon in the maintenance of allograft tolerance.

Figure 1. MHC cross-dressing can promote CD4+ Treg-mediated suppression of alloreactive T effector cells.

Panel A and B depicts two models describing how CD4+ Treg cells can suppress T effector cells after placement of an MHC-mismatched allograft. Panel A shows a classical 4 cell cluster whereby CD4+ Tregs and effector T cells recognize donor MHC indirectly (donor MHC peptide) and directly (intact donor MHC), respectively on distinct APCs. Panel B shows how donor MHC class II cross-dressing can promote Treg-mediated suppression of T effector cells by having self-MHC class II + donor peptide (indirect presentation) and donor MHC (direct presentation) presented on the same recipient antigen presenting cell (three cell cluster).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. David Sachs, Megan Sykes, William Burlingham, Christian LeGuern and Angus Thomson for thoughtful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH to Gilles Benichou, NIH R21AI100278 and NIH R01DK115618 and to Joren C. Madsen, NIH PO1HL018646, PO1AI123086 and UO1AI131470.

Abbreviations

- APC

antigen-presenting cell

- BALT

bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue

- CAV

cardiac allograft vasculopathy

- CNS1

conserved noncoding sequence 1

- CyA

cyclosporine A

- DIC

decidual immune cell

- DSC

decidual stromal cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- DST

donor-specific transfusion

- EVT

extravillous trophoblast

- HEV

high endothelial venule

- LC

Langerhans cell

- NIMA

noninherited maternal antigen

- pNK

peripheral maternal NK cell

- pTreg

peripheral regulatory T cell

- Treg

regulatory T cell

- Ts

T suppressor cell

- TLO

tertiary lymphoid organ

- tTreg

thymic regulatory T cell

- VAT Treg

visceral adipose tissue regulatory T cell

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

References

- 1.Barker CF, Billingham RE. The lymphatic status of hamster cheek pouch tissue in relation to its properties as a graft and as a graft site. J Exp Med 1971;133(3):620–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streilein JW. Immunologic privilege of the eye. Springer Semin Immunopathol 1999;21(2):95–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson E A historical perspective on immunological privilege. Immunological reviews 2006;213:12–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cobbold SP, Adams E, Graca L, Daley S, Yates S, Paterson A et al. Immune privilege induced by regulatory T cells in transplantation tolerance. Immunol Rev 2006;213:239–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Niederkorn JY. Immune privilege and immune regulation in the eye. Adv Immunol 1990;48:191–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood KJ. Peripheral tolerance to alloantigen in the adult. Autoimmunity 1993;15 Suppl:14–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashton-Rickardt PG, Bandeira A, Delaney JR, Van Kaer L, Pircher HP, Zinkernagel RM et al. Evidence for a differential avidity model of T cell selection in the thymus [see comments]. Cell 1994;76(4):651–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton-Rickardt PG, Van Kaer L, Schumacher TN, Ploegh HL, Tonegawa S. Peptide contributes to the specificity of positive selection of CD8+ T cells in the thymus. Cell 1993;73(5):1041–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald BD, Bunker JJ, Erickson SA, Oh-Hora M, Bendelac A. Crossreactive alphabeta T Cell Receptors Are the Predominant Targets of Thymocyte Negative Selection. Immunity 2015;43(5):859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Meerwijk JP, Marguerat S, Lees RK, Germain RN, Fowlkes BJ, MacDonald HR. Quantitative impact of thymic clonal deletion on the T cell repertoire. J Exp Med 1997;185(3):377–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sercarz EE, Lehmann PV, Ametani A, Benichou G, Miller A, Moudgil K. Dominance and crypticity of T cell antigenic determinants. Annu Rev Immunol 1993;11:729–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medawar PB. Some immunological and endocrinological problems raised by the evolution of viviparity in vertebrates. Symp Soc Exp Biol 1953;7:320–327. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trowsdale J, Betz AG. Mother’s little helpers: mechanisms of maternal- fetal tolerance. Nature immunology 2006;7(3):241–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rood JJ, Claas F. Both self and non-inherited maternal HLA antigens influence the immune response. Immunology today 2000;21(6):269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claas FH, Gijbels Y, van der Velden-de Munck J, van Rood JJ. Induction of B cell unresponsiveness to noninherited maternal HLA antigens during fetal life. Science 1988;241(4874):1815–1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson E, Chandler P, Pole D. A model of T-cell unresponsiveness using the male-specific antigen, H-Y. Cellular immunology 1981;62(2):251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith RN, Powell AE. The adoptive transfer of pregnancy-induced unresponsiveness to male skin grafts with thymus-dependent cells. J Exp Med 1977;146(3):899–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaouat G, Voisin GA, Escalier D, Robert P. Facilitation reaction (enhancing antibodies and suppressor cells) and rejection reaction (sensitized cells) from the mother to the paternal antigens of the conceptus. Clinical and experimental immunology 1979;35(1):13–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen T, Darrasse-Jeze G, Bergot AS, Courau T, Churlaud G, Valdivia K et al. Self-specific memory regulatory T cells protect embryos at implantation in mice. J Immunol 2013;191(5):2273–2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Darrasse-Jeze G, Klatzmann D, Charlotte F, Salomon BL, Cohen JL. CD4+CD25+ regulatory/suppressor T cells prevent allogeneic fetus rejection in mice. Immunology letters 2006;102(1):106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samstein RM, Josefowicz SZ, Arvey A, Treuting PM, Rudensky AY. Extrathymic generation of regulatory T cells in placental mammals mitigates maternal-fetal conflict. Cell 2012;150(1):29–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira LM, Meissner TB, Tilburgs T, Strominger JL. HLA-G: At the Interface of Maternal-Fetal Tolerance. Trends in immunology 2017;38(4):272–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vince GS, Starkey PM, Jackson MC, Sargent IL, Redman CW. Flow cytometric characterisation of cell populations in human pregnancy decidua and isolation of decidual macrophages. Journal of immunological methods 1990;132(2):181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu YY, Wang SC, Li DJ, Du MR. Co-Signaling Molecules in Maternal- Fetal Immunity. Trends in molecular medicine 2017;23(1):46–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rajagopalan S, Long EO. A human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-G-specific receptor expressed on all natural killer cells. J Exp Med 1999;189(7):1093–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rouas-Freiss N, Marchal RE, Kirszenbaum M, Dausset J, Carosella ED. The alpha1 domain of HLA-G1 and HLA-G2 inhibits cytotoxicity induced by natural killer cells: is HLA-G the public ligand for natural killer cell inhibitory receptors? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94(10):5249–5254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.HoWangYin KY, Caumartin J, Favier B, Daouya M, Yaghi L, Carosella ED et al. Proper regrafting of Ig-like transcript 2 after trogocytosis allows a functional cell-cell transfer of sensitivity. J Immunol 2011;186(4):2210–2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aucher A, Magdeleine E, Joly E, Hudrisier D. Capture of plasma membrane fragments from target cells by trogocytosis requires signaling in T cells but not in B cells. Blood 2008;111(12):5621–5628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joly E, Hudrisier D. What is trogocytosis and what is its purpose? Nature immunology 2003;4(9):815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caumartin J, Favier B, Daouya M, Guillard C, Moreau P, Carosella ED et al. Trogocytosis-based generation of suppressive NK cells. The EMBO journal 2007;26(5):1423–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilburgs T, Evans JH, Crespo AC, Strominger JL. The HLA-G cycle provides for both NK tolerance and immunity at the maternal-fetal interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(43):13312–13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeMaoult J, Caumartin J, Daouya M, Favier B, Le Rond S, Gonzalez A et al. Immune regulation by pretenders: cell-to-cell transfers of HLA-G make effector T cells act as regulatory cells. Blood 2007;109(5):2040–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown R, Kabani K, Favaloro J, Yang S, Ho PJ, Gibson J et al. CD86+ or HLA-G+ can be transferred via trogocytosis from myeloma cells to T cells and are associated with poor prognosis. Blood 2012;120(10):2055–2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brugiere O, Thabut G, Krawice-Radanne I, Rizzo R, Dauriat G, Danel C et al. Role of HLA-G as a predictive marker of low risk of chronic rejection in lung transplant recipients: a clinical prospective study. Am J Transplant 2015;15(2):461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lo YM, Lo ES, Watson N, Noakes L, Sargent IL, Thilaganathan B et al. Two-way cell traffic between mother and fetus: biologic and clinical implications. Blood 1996;88(11):4390–4395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernochet C, Caucheteux SM, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C. Bi-directional cell trafficking between mother and fetus in mouse placenta. Placenta 2007;28(7):639–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akiyama Y, Caucheteux S, Iwamoto Y, Roughan J, Kanellopoulos-Langevin C, Benichou G. Transplantation tolerance to non-inherited maternal antigens (NIMA) in a MHC class I transgenic mouse model. Human immunology 2003;64(10 Suppl):S129. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andrassy J, Kusaka S, Jankowska-Gan E, Torrealba JR, Haynes LD, Marthaler BR et al. Tolerance to noninherited maternal MHC antigens in mice. J Immunol 2003;171(10):5554–5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molitor ML, Burlingham WJ. Immunobiology of exposure to non-inherited maternal antigens. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library 2007;12:3302–3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burlingham WJ, Grailer AP, Heisey DM, Claas FH, Norman D, Mohanakumar T et al. The effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal HLA antigens on the survival of renal transplants from sibling donors. The New England journal of medicine 1998;339(23):1657–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dutta P, Burlingham WJ. Tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens in mice and humans. Current opinion in organ transplantation 2009;14(4):439–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dutta P, Molitor-Dart M, Bobadilla JL, Roenneburg DA, Yan Z, Torrealba JR et al. Microchimerism is strongly correlated with tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens in mice. Blood 2009;114(17):3578–3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bracamonte-Baran W, Florentin J, Zhou Y, Jankowska-Gan E, Haynes WJ, Zhong W et al. Modification of host dendritic cells by microchimerism-derived extracellular vesicles generates split tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017;114(5):1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burlingham WJ, Benichou G. Bidirectional alloreactivity: A proposed microchimerism-based solution to the NIMA paradox. Chimerism 2012;3(2):29–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonoda Y, Streilein JW. Orthotopic corneal transplantation in mice evidence that the immunogenetic rules of rejection do not apply. Transplantation 1992;54(4):694–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sonoda Y, Streilein JW. Impaired cell-mediated immunity in mice bearing healthy orthotopic corneal allografts. J Immunol 1993;150(5):1727–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boisgerault F, Liu Y, Anosova N, Dana R, Benichou G. Differential roles of direct and indirect allorecognition pathways in the rejection of skin and corneal transplants. Transplantation 2009;87(1):16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boisgerault F, Liu Y, Anosova N, Ehrlich E, Dana MR, Benichou G. Role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in allorecognition: lessons from corneal transplantation. Journal of Immunology 2001;167(4):1891–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sano Y, Ksander BR, Streilein JW. Minor H, rather than MHC, alloantigens offer the greater barrier to successful orthotopic corneal transplantation in mice. Transpl Immunol 1996;4(1):53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamada J, Streilein JW. Fate of orthotopic corneal allografts in C57BL/6 mice. Transpl Immunol 1998;6(3):161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Streilein JW. Regulation of ocular immune responses. Eye 1997;11(Pt 2):171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ksander BR, Sano Y, Streilein JW. Role of donor-specific cytotoxic T cells in rejection of corneal allografts in normal and high-risk eyes. Transpl Immunol 1996;4(1):49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Streilein JW, Toews GB, Bergstresser PR. Corneal allografts fail to express Ia antigens. Nature 1979;282(5736):326–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tahvildari M, Amouzegar A, Foulsham W, Dana R. Therapeutic approaches for induction of tolerance and immune quiescence in corneal allotransplantation. Cell Mol Life Sci 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hamrah P, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Dana MR. The corneal stroma is endowed with a significant number of resident dendritic cells. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2003;44(2):581–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Hamrah P, Zhang Q, Taylor AW, Dana MR. Draining lymph nodes of corneal transplant hosts exhibit evidence for donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II-positive dendritic cells derived from MHC class II- negative grafts. J Exp Med 2002;195(2):259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakamura T, Ishikawa F, Sonoda KH, Hisatomi T, Qiao H, Yamada J et al. Characterization and distribution of bone marrow-derived cells in mouse cornea. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2005;46(2):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huq S, Liu Y, Benichou G, Dana MR. Relevance of the direct pathway of sensitization in corneal transplantation is dictated by the graft bed microenvironment. J Immunol 2004;173(7):4464–4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hegde S, Niederkorn JY. The role of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in corneal allograft rejection. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2000;41(11):3341–3347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Niederkorn JY. The immune privilege of corneal grafts. Journal of leukocyte biology 2003;74(2):167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Qian S, Demetris AJ, Murase N, Rao AS, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Murine liver allograft transplantation: tolerance and donor cell chimerism. Hepatology 1994;19(4):916–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sumpter TL, Abe M, Tokita D, Thomson AW. Dendritic cells, the liver, and transplantation. Hepatology 2007;46(6):2021–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.You Q, Cheng L, Kedl RM, Ju C. Mechanism of T cell tolerance induction by murine hepatic Kupffer cells. Hepatology 2008;48(3):978–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ono Y, Perez-Gutierrez A, Nakao T, Dai H, Camirand G, Yoshida O et al. Graft-infiltrating PD-L1(hi) cross-dressed dendritic cells regulate antidonor T cell responses in mouse liver transplant tolerance. Hepatology 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schurich A, Berg M, Stabenow D, Bottcher J, Kern M, Schild HJ et al. Dynamic regulation of CD8 T cell tolerance induction by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells. J Immunol 2010;184(8):4107–4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sumpter TL, Dangi A, Matta BM, Huang C, Stolz DB, Vodovotz Y et al. Hepatic stellate cells undermine the allostimulatory function of liver myeloid dendritic cells via STAT3-dependent induction of IDO. J Immunol 2012;189(8):3848–3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burghardt S, Erhardt A, Claass B, Huber S, Adler G, Jacobs T et al. Hepatocytes contribute to immune regulation in the liver by activation of the Notch signaling pathway in T cells. J Immunol 2013;191(11):5574–5582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ezzelarab M, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and their role in transplantation. Seminars in immunology 2011;23(4):252–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.De Creus A, Abe M, Lau AH, Hackstein H, Raimondi G, Thomson AW. Low TLR4 expression by liver dendritic cells correlates with reduced capacity to activate allogeneic T cells in response to endotoxin. J Immunol 2005;174(4):2037–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xia S, Guo Z, Xu X, Yi H, Wang Q, Cao X. Hepatic microenvironment programs hematopoietic progenitor differentiation into regulatory dendritic cells, maintaining liver tolerance. Blood 2008;112(8):3175–3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matta BM, Raimondi G, Rosborough BR, Sumpter TL, Thomson AW. IL-27 production and STAT3-dependent upregulation of B7-H1 mediate immune regulatory functions of liver plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol 2012;188(11):5227–5237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crispe IN, Giannandrea M, Klein I, John B, Sampson B, Wuensch S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of liver tolerance. Immunological reviews 2006;213:101–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiao J, Sastre D, Fiel MI, Lee UE, Ghiassi-Nejad Z, Ginhoux F et al. Dendritic cell regulation of carbon tetrachloride-induced murine liver fibrosis regression. Hepatology 2012;55(1):244–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henning JR, Graffeo CS, Rehman A, Fallon NC, Zambirinis CP, Ochi A et al. Dendritic cells limit fibroinflammatory injury in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 2013;58(2):589–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bamboat ZM, Ocuin LM, Balachandran VP, Obaid H, Plitas G, DeMatteo RP. Conventional DCs reduce liver ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice via IL-10 secretion. J Clin Invest 2010;120(2):559–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yoshida O, Kimura S, Jackson EK, Robson SC, Geller DA, Murase N et al. CD39 expression by hepatic myeloid dendritic cells attenuates inflammation in liver transplant ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology 2013;58(6):2163– 2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokota S, Yoshida O, Ono Y, Geller DA, Thomson AW. Liver transplantation in the mouse: Insights into liver immunobiology, tissue injury, and allograft tolerance. Liver transplantation : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society 2016;22(4):536–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bamboat ZM, Stableford JA, Plitas G, Burt BM, Nguyen HM, Welles AP et al. Human liver dendritic cells promote T cell hyporesponsiveness. J Immunol 2009;182(4):1901–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tokita D, Shishida M, Ohdan H, Onoe T, Hara H, Tanaka Y et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells that endocytose allogeneic cells suppress T cells with indirect allospecificity. J Immunol 2006;177(6):3615–3624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sumpter TL, Packiam V, Turnquist HR, Castellaneta A, Yoshida O, Thomson AW. DAP12 promotes IRAK-M expression and IL-10 production by liver myeloid dendritic cells and restrains their T cell allostimulatory ability. J Immunol 2011;186(4):1970–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yoshida O, Kimura S, Dou L, Matta BM, Yokota S, Ross MA et al. DAP12 deficiency in liver allografts results in enhanced donor DC migration, augmented effector T cell responses and abrogation of transplant tolerance. Am J Transplant 2014;14(8):1791–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li W, Kuhr CS, Zheng XX, Carper K, Thomson AW, Reyes JD et al. New insights into mechanisms of spontaneous liver transplant tolerance: the role of Foxp3-expressing CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Am J Transplant 2008;8(8):1639–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Thomson AW, Knolle PA. Antigen-presenting cell function in the tolerogenic liver environment. Nature reviews Immunology 2010;10(11):753–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Thai NL, Li Y, Fu F, Qian S, Demetris AJ, Duquesnoy RJ et al. Interleukin- 2 and interleukin-12 mediate distinct effector mechanisms of liver allograft rejection. Liver transplantation and surgery : official publication of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the International Liver Transplantation Society 1997;3(2):118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qian S, Lu L, Fu F, Li Y, Li W, Starzl TE et al. Apoptosis within spontaneously accepted mouse liver allografts: evidence for deletion of cytotoxic T cells and implications for tolerance induction. J Immunol 1997;158(10):4654– 4661. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu L, Rudert WA, Qian S, McCaslin D, Fu F, Rao AS et al. Growth of donor-derived dendritic cells from the bone marrow of murine liver allograft recipients in response to granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med 1995;182(2):379–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thomson AW, Lu L, Wan Y, Qian S, Larsen CP, Starzl TE. Identification of donor-derived dendritic cell progenitors in bone marrow of spontaneously tolerant liver allograft recipients. Transplantation 1995;60(12):1555–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dutkowski P, Linecker M, DeOliveira ML, Mullhaupt B, Clavien PA. Challenges to liver transplantation and strategies to improve outcomes. Gastroenterology 2015;148(2):307–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Russell PS, Chase CM, Colvin RB, Plate JM. Kidney transplants in mice. An analysis of the immune status of mice bearing long-term, H-2 incompatible transplants. J Exp Med 1978;147(5):1449–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Miyajima M, Chase CM, Alessandrini A, Farkash EA, Della Pelle P, Benichou G et al. Early acceptance of renal allografts in mice is dependent on foxp3(+) cells. The American journal of pathology 2011;178(4):1635–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moltedo B, Hemmers S, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell ablation causes acute T cell lymphopenia. PloS one 2014;9(1):e86762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gleeson PA, Toh BH, van Driel IR. Organ-specific autoimmunity induced by lymphopenia. Immunological reviews 1996;149:97–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Singh NJ, Schwartz RH. The lymphopenic mouse in immunology: from patron to pariah. Immunity 2006;25(6):851–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Graca L, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Identification of regulatory T cells in tolerated allografts. J Exp Med 2002;195(12):1641–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li W, Bribriesco AC, Nava RG, Brescia AA, Ibricevic A, Spahn JH et al. Lung transplant acceptance is facilitated by early events in the graft and is associated with lymphoid neogenesis. Mucosal immunology 2012;5(5):544–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baddoura FK, Nasr IW, Wrobel B, Li Q, Ruddle NH, Lakkis FG. Lymphoid neogenesis in murine cardiac allografts undergoing chronic rejection. Am J Transplant 2005;5(3):510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ruddle NH. High Endothelial Venules and Lymphatic Vessels in Tertiary Lymphoid Organs: Characteristics, Functions, and Regulation. Frontiers in immunology 2016;7:491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Panduro M, Benoist C, Mathis D. Tissue Tregs. Annu Rev Immunol 2016;34:609–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Feuerer M, Herrero L, Cipolletta D, Naaz A, Wong J, Nayer A et al. Lean, but not obese, fat is enriched for a unique population of regulatory T cells that affect metabolic parameters. Nature medicine 2009;15(8):930–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self- tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol 1995;155(3):1151–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yang S, Fujikado N, Kolodin D, Benoist C, Mathis D. Immune tolerance. Regulatory T cells generated early in life play a distinct role in maintaining self- tolerance. Science 2015;348(6234):589–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rosengard BR, Ojikutu CA, Guzzetta PC, Smith CV, Sundt TM 3rd, Nakajima K et al. Induction of specific tolerance to class I-disparate renal allografts in miniature swine with cyclosporine. Transplantation 1992;54(3):490– 497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gianello PR, Blancho G, Fishbein JF, Lorf T, Nickeleit V, Vitiello D et al. Mechanism of cyclosporin-induced tolerance to primarily vascularized allografts in miniature swine. Effect of administration of exogenous IL-2. Journal of immunology 1994;153(10):4788–4797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Madsen JC, Yamada K, Allan JS, Choo JK, Erhorn AE, Pins MR et al. Transplantation tolerance prevents cardiac allograft vasculopathy in major histocompatibility complex class I-disparate miniature swine. Transplantation 1998;65(3):304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Okumi M, Fishbein JM, Griesemer AD, Gianello PR, Hirakata A, Nobori S et al. Role of persistence of antigen and indirect recognition in the maintenance of tolerance to renal allografts. Transplantation 2008;85(2):270–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Madsen JC, Sachs DH, Fallon JT, Weissman NJ. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy in partially inbred miniature swine. I. Time course, pathology, and dependence on immune mechanisms. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery 1996;111(6):1230–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Scalea JR, Okumi M, Villani V, Shimizu A, Nishimura H, Gillon BC et al. Abrogation of renal allograft tolerance in MGH miniature swine: the role of intra- graft and peripheral factors in long-term tolerance. Am J Transplant 2014;14(9):2001–2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Okumi M, Scalea JR, Gillon BC, Tasaki M, Villani V, Cormack T et al. The induction of tolerance of renal allografts by adoptive transfer in miniature swine. Am J Transplant 2013;13(5):1193–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Villani V, Yamada K, Scalea JR, Gillon BC, Arn JS, Sekijima M et al. Adoptive Transfer of Renal Allograft Tolerance in a Large Animal Model. Am J Transplant 2016;16(1):317–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Weiss MJ, Guenther DA, Mezrich JD, Sahara H, Ng CY, Meltzer AJ et al. The indirect alloresponse impairs the induction but not maintenance of tolerance to MHC class I-disparate allografts. Am J Transplant 2009;9(1):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mezrich JD, Benjamin LC, Sachs JA, Houser SL, Vagefi PA, Sachs DH et al. Role of the thymus and kidney graft in the maintenance of tolerance to heart grafts in miniature swine. Transplantation 2005;79(12):1663–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]