To the Editor:

Anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress are prevalent among ICU survivors, can persist long-term, and are associated with low quality of life (1). Risk factors include frightening and delusional memories of ICU stay, especially for long-term post-traumatic stress (2, 3). Frightening memories could relate to ICU stress; for example, from pain, anxiety, and dreams. Delusional memories may originate from hallucinations and periods of delirium. These may all be influenced by sedation, analgesia, and delirium management (4). Few studies have described the nature and prevalence of frightening and traumatic memories early after ICU discharge. This transition of care is known to be stressful to both patients and family members, and is the time during which patients are starting to adjust to critical illness sequelae. Screening and intervention for psychological morbidity at this time might reduce long-term problems, especially if the patients at highest risk could be identified.

In a preplanned substudy within a published cluster, randomized quality-improvement trial of sedation interventions in eight Scottish ICUs (the DESIST [Development and Evaluation of Strategies to Improve Sedation Practice in Intensive Care] trial [5, 6]), we administered two validated questionnaires to ICU survivors during their recovery on general wards early after ICU discharge. These were the Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R), which measures traumatic symptomatology (7), and the Intensive Care Experience Questionnaire (ICE-Q) (8). The ICE-Q includes 31 items measuring patients’ perceptions of their intensive care experience, grouped into four domains, including a frightening experiences subscore (FESS; comprising six questions) (8). The FESS demonstrates a Cronbach α > 0.7 in previous studies, indicating validity, and previous studies have also found that ICE-Q scores could predict subsequent psychological morbidity (8–10).

Participants in the DESIST trial required mechanical ventilation with anticipated duration >48 hours. When possible, surviving participants were approached after ICU discharge to complete the questionnaires and asked to anchor their responses to ICU memories. All patients provided written consent, and the study was approved by the Scottish A Research Ethics Committee. These data were exploratory secondary outcomes and were not reported in the main trial, but some results have been previously reported in the form of an abstract (11). We report here a cohort analysis of all survivors who completed questionnaires.

We aimed to describe the frequency and nature of frightening and traumatic memories early after ICU discharge, while patients were still in hospital. For the ICE-Q questionnaire, we reported responses to each of the six questions comprising the FESS subscore, the total FESS subscore, and the proportion of patients with a FESS >18 (a cutoff representing an average score >3 [neutral response] across contributing questions). For the IES-R, we reported responses to all 22 questions, the IES-R total score, and the proportion of patients with a score >35 (indicating significant traumatic symptomatology [7]).

We also used responses to a separate ICE-Q question (“I have no memory of intensive care”; five potential responses ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree) to explore relationships between patients’ overall memory of ICU and the FESS subscore and IES-R score.

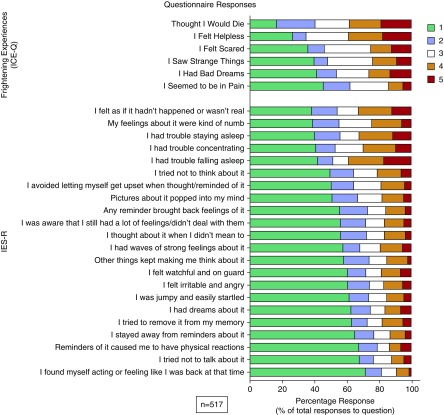

There were 1,291 ICU survivors in the trial. The ICE-Q and IES-R were completed by 517 survivors (40%). Survivors who completed questionnaires had longer post-ICU hospital stays and included lower proportions of general medical and higher proportions of general surgical patients than those who did not complete questionnaires (Table 1). There was also some imbalance in admission source. The median number of days to questionnaire completion was 7 days (interquartile range, 4–14 d) after ICU discharge. Responses to the individual questions are shown in Figure 1. The median sum score for the ICE-Q FESS was 15 (interquartile range, 11–21), and for IES-R, it was 19 (interquartile range, 7–36). There were 34.4% (95% confidence interval, 30.3%–38.5%) of the patients with a FESS score >18, and 25.1% (95% confidence interval, 21.4%–28.8%) with an IES-R score >35. Patient responses to the two questionnaires correlated strongly, indicating that patients who had more frightening memories also reported greater trauma symptomatology (Spearman rho coefficient, 0.62; P < 0.001). Post-ICU memories were diverse: among the ICE-Q responses, fear, helplessness, and anticipating death were frequent. Among the IES-R responses, memories of numbness, unreality, and sleep disturbance were most common.

Table 1.

Demographic Data of Participants Who Completed or Did Not Complete the Questionnaire Follow-up

| Characteristic | ICE-Q and IES-R Completed | ICE-Q and IES-R Not Completed | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valid (missing) | 517 (0) | 772 (2) | |

| Age, yr, median (IQR) | 60.0 (48.5–69.0) | 61.0 (47.0–71.0) | 0.46 |

| Male, n (%) | 305 (59.0) | 463 (59.9) | 0.77 |

| APACHE II score | |||

| Valid (missing) | 491 (26) | 750 (24) | |

| Mean (SD) | 20.58 (6.93) | 21.16 (7.49) | 0.17 |

| Length of ICU stay, d, median (IQR) | 6.74 (3.66–12.67) | 6.76 (3.70–11.86) | 0.43 |

| Duration of ventilation, d, median (IQR) | 3.44 (1.70–8.40) | 4.0 (1.86–8.08) | 0.25 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | |||

| Valid (missing) | 516 (1) | 771 (3) | |

| Median (IQR) | 27.0 (15.0–48.75) | 19.0 (10.0–34.0) | <0.001 |

| Case mix: proportion medical, n (%) | 274 (52.9) | 482 (62.4) | <0.001 |

| Medical specialty, n (%) | |||

| General medicine | 147 (28.9) | 299 (38.7) | |

| Cardiology | 33 (6.4) | 44 (5.7) | |

| Gastrointestinal | 29 (5.6) | 32 (4.1) | |

| Respiratory | 26 (5.0) | 35 (4.5) | |

| Ear/nose/throat | 11 (2.1) | 13 (1.7) | |

| Neurology | 5 (1.0) | 18 (2.3) | |

| Renal | 6 (1.2) | 13 (1.7) | |

| Other | 17 (3.3) | 28 (3.6) | |

| Surgical specialty, n (%) | |||

| General surgery | 156 (30.2) | 188 (24.3) | |

| Vascular | 24 (4.6) | 43 (5.6) | |

| Transplant | 30 (5.8) | 12 (1.6) | |

| Orthopedics | 19 (3.7) | 27 (3.5) | |

| Cardiac | 5 (1.0) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Neurosurgery | 0 (0) | 4 (0.5) | |

| Other | 9 (1.7) | 11 (1.4) | |

| Source of admission, n (%) | 0.02 | ||

| Operating room | 171 (33.0) | 198 (25.6) | |

| Emergency department | 119 (23.0) | 241 (31.2) | |

| High dependency unit | 101 (19.5) | 129 (16.7) | |

| Other ward in hospital | 69 (13.3) | 100 (12.9) | |

| Other hospital | 23 (4.4) | 41 (5.3) | |

| Other ICU | 16 (3.1) | 18 (2.3) | |

| Other immediate care area | 12 (2.3) | 18 (2.3) | |

| Other | 6 (1.2) | 17 (2.2) |

Definition of abbreviations: APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICE-Q = Intensive Care Experience Questionnaire; IES-R = Impact of Events Scale-Revised; IQR = interquartile range.

P value denotes comparison using Mann-Whitney U test for age, and duration variables; independent sample t test for APACHE II; chi (2) for sex and case mix (medical or surgical). Unless stated, the variable contains no missing values.

Figure 1.

Individual responses to the questions that comprise the frightening experiences subscore of the Intensive Care Experience Questionnaire (ICE-Q) and Impact of Event Scale Revised (IES-R) responses. Scores represent: ICE-Q: 1, never/strongly disagree; 2, rarely/disagree; 3, sometimes/neither; 4, frequently/agree; 5, all the time. IES-R: 1, not at all; 2, a little bit; 3, moderately; 4, quite a bit; 5, extremely.

In relation to patients’ overall memory of ICU, we found those with less overall memory had fewer frightening memories (correlation with FESS scores: rho, −0.18; P < 0.001) and traumatic memories (correlation with IES-R scores, rho, −0.13; P = 0.004), although both associations were very weak.

To our knowledge, this is the largest reported study of frightening and traumatic memories in the early post-ICU discharge period. Our data suggest these memories occur in 25%–35% of patients. Although our cohort was large, and from a general ICU population, both inclusion and response bias could have influenced these estimates. Patients who required no or only brief mechanical ventilation were excluded from the DESIST trial, and data were available for only 40% of participants. Missed responses were mainly a result of limited trial resource; we found many patients were already discharged from hospital when ward-based follow-up occurred and later contact was not feasible. Missing cases were more likely to have general medical diagnoses, had shorter hospital stays, and were more often admitted directly from the emergency department. These and other unmeasured confounders could have biased the prevalence estimates. However, our data are consistent with smaller studies describing delusional memories early after ICU discharge, and previous studies using the ICE-Q (3, 8–10). Although delusion-like memories are known predictors of long-term psychological morbidity (2), controversy exists regarding whether factual memories, even if frightening, are protective (3, 12). Our data illustrate the diversity, complexity, and personalized nature of early post-ICU memories.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate prevalent early traumatic and frightening memories that might contribute to long-term psychological morbidity after ICU. This supports a hypothesis that systematic screening at this time may be useful as part of a strategy for personalized targeted care and interventions to reduce later psychological morbidity.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The DESIST trial was supported by grants from the Chief Scientists Office, Scotland, and GE Healthcare (unrestricted funding). S.T. was supported by a John Snow Anesthesia Intercalated bursary award for B.Med.Sci. students (Royal College of Anaesthetists/British Journal of Anesthesia). C.J.W. was supported in this work by NHS Lothian via the Edinburgh Clinical Trials Unit.

Author Contributions: K.K., C.J.W., and T.S.W. conceived the DESIST study, secured funding, and managed the research; all authors conceived the current substudy, contributed to analysis, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version; and all authors are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the work.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0699LE on October 12, 2018

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: on behalf of the DESIST (Development and Evaluation of Strategies to Improve Sedation Practice in Intensive Care) Investigators

References

- 1.Ringdal M, Plos K, Lundberg D, Johansson L, Bergbom I. Outcome after injury: memories, health-related quality of life, anxiety, and symptoms of depression after intensive care. J Trauma. 2009;66:1226–1233. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318181b8e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, Schneck KW, Bienvenu OJ, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1121–1129. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiekkas P, Theodorakopoulou G, Spyratos F, Baltopoulos GI. Psychological distress and delusional memories after critical care: a literature review. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57:288–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aitken LM, Castillo MI, Ullman A, Engström Å, Cunningham K, Rattray J. What is the relationship between elements of ICU treatment and memories after discharge in adult ICU survivors? Aust Crit Care. 2016;29:5–14, quiz 15. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh TS, Kydonaki K, Antonelli J, Stephen J, Lee RJ, Everingham K, et al. Development and Evaluation of Strategies to Improve Sedation Practice in Intensive Care (DESIST) study investigators. Staff education, regular sedation and analgesia quality feedback, and a sedation monitoring technology for improving sedation and analgesia quality for critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:807–817. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh TS, Kydonaki K, Antonelli J, Stephen J, Lee RJ, Everingham K, et al. Development and Evaluation of Strategies to Improve Sedation practice in in Tensive care Study Investigators. Rationale, design and methodology of a trial evaluating three strategies designed to improve sedation quality in intensive care units (DESIST study) BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010148. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bienvenu OJ, Williams JB, Yang A, Hopkins RO, Needham DM. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of acute lung injury: evaluating the Impact of Event Scale-Revised. Chest. 2013;144:24–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rattray J, Johnston M, Wildsmith JAW. The intensive care experience: development of the ICE questionnaire. J Adv Nurs. 2004;47:64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alasad JA, Abu Tabar N, Ahmad MM. Patients’ experience of being in intensive care units. J Crit Care. 2015;30:859.e7–859.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rattray J, Crocker C, Jones M, Connaghan J. Patients’ perceptions of and emotional outcome after intensive care: results from a multicentre study. Nurs Crit Care. 2010;15:86–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Train S, Rattray J, Antonelli J, Stephen J, Weir C, Walsh TS. A retrospective cohort study investigating prevalence and nature of frightening memories in adult ICU survivors and their association with ICU exposures [abstract] J Intensive Care Soc. 2018;19:EP161. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Skirrow PM. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:573–580. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.