Abstract

Background

During intensive care unit (ICU) admission, patients experience extreme physical and psychological stressors, including the abnormal ICU environment. These experiences impact on a patient’s recovery from critical illness and may result in both physical and psychological disorders. One strategy that has been developed and implemented by clinical staff to treat the psychological distress prevalent in ICU survivors is the use of patient diaries. These provide a background to the cause of the patient’s ICU admission and an ongoing narrative outlining day‐to‐day activities.

Objectives

To assess the effect of a diary versus no diary on patients, and their caregivers or families, during the patient's recovery from admission to an ICU.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2014, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to January 2014), EBSCOhost CINAHL (1982 to January 2014), Ovid EMBASE (1980 to January 2014), PsycINFO (1950 to January 2014), Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) database (1971 to January 2014); Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science and Social Science and Humanities (1990 to January 2014); seven clinical trial registries and reference lists of identified trials. We applied no language restriction.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or clinical controlled trials (CCTs) that evaluated the effectiveness of patient diaries, when compared to no ICU diary, for patients or family members to promote recovery after admission to ICU. Outcome measures for describing recovery from ICU included the risk of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression and post‐traumatic stress symptomatology, health‐related quality of life and costs.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological approaches as expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. Two review authors independently reviewed titles for inclusion, extracted data and undertook risk of bias according to prespecified criteria.

Main results

We identified three eligible studies; two describing ICU patients (N = 358), and one describing relatives of ICU patients (N = 30). The study involving relatives of ICU patients was a substudy of family members from one of the ICU patient studies. There was a mixed risk of bias within the included studies. Blinding of participants to allocation was not possible and blinding of the outcome assessment was not adequately achieved or reported. Overall the quality of the evidence was low to very low. The patient diary intervention was not identical between studies. However, each provided a prospectively prepared, day‐to‐day description of the participants' ICU admission.

No study adequately reported on risk of PTSD as described using a clinical interview, family or caregiver anxiety or depression, health‐related quality of life or costs. Within a single study there was no clear evidence of a difference in risk for developing anxiety (risk ratio (RR) 0.29, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.07 to 1.19) or depression (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.19) in participants who received ICU diaries, in comparison to those that did not receive a patient diary. However, the results were imprecise and consistent with benefit in either group, or no difference. Within a single study there was no evidence of difference in median post‐traumatic stress symptomatology scores (diaries 24, SD 11.6; no diary 24, SD 11.6) and delusional ICU memory recall (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.28) between the patients recovering from ICU admission who received patient diaries, and those who did not. One study reported reduced post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU who received patient diaries (median 19; range 14 to 28), in comparison to no diary (median 28; range 14 to 38).

Authors' conclusions

Currently there is minimal evidence from RCTs of the benefits or harms of patient diaries for patients and their caregivers or family members. A small study has described their potential to reduce post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in family members. However, there is currently inadequate evidence to support their effectiveness in improving psychological recovery after critical illness for patients and their family members.

Plain language summary

Diaries for recovery from critical illness

Review question

We reviewed the evidence about the effect of diaries, in comparison to no diary, on recovery in people recuperating from critical illness, and their caregivers and families.

Background

People who have been critically ill experience significant physical and psychological problems during recovery. Diaries outlining a person's intensive care unit (ICU) experience have been suggested as something that may be effective in helping survivors and their family members recover psychological function.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to January 2014. We identified three eligible studies; two describing 358 ICU patients, and one describing 30 relatives of ICU patients. These were included in the review. The study involving relatives of ICU patients was a substudy of family members from one of the ICU patient studies. All people included in the studies were adults based in Europe and the UK, with a mixed severity of critical illness requiring admission to an ICU.

Key results

We found no studies that had reported the risk of post‐traumatic stress disorder in patients recovering from admission to ICU using a structured clinical interview.

The other primary outcome measures of anxiety and depression were described in one study of 36 patients. In this study no clear evidence of a difference was seen in anxiety and depression when patient diaries were used for people recovering from ICU admission, in comparison to no diaries. Post‐traumatic stress symptoms in family members and caregivers were reduced in another study of 30 people when patient diaries were used, in comparison to no diaries.

Current research has not adequately assessed the safety and effectiveness of patient diaries. Adverse events associated with the use of diaries have not been reported. It has not been established whether patient diaries are an effective practice or whether they may cause harm.

Quality of the evidence The overall quality of the evidence to support the use of diaries to promote recovery for patients and caregivers or families recuperating from critical illness is low or very low. This is because of the small amount of research and the methodological quality of studies. There is no evidence to support their use and it has not been established whether they cause benefit or harm.

Background

Description of the condition

Critical illness requiring admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) continues to increase in frequency around the world. As advances in health care are realized, more patients are surviving their stay in ICU but the implication of this is that there is an increase in the number of patients experiencing challenges during the recovery phase. During their ICU admission, patients experience extreme physical and psychological stressors including critical illness, delirium, fear, lack of privacy, noise, pain, sedation administration, sleep deprivation, and the abnormal ICU environment (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012; Kiekkas 2010; Meriläginen 2010). These experiences impact on a patient’s recovery from critical illness, which can be a complex and protracted process (Adamson 2004). Within this recovery period, patients may experience both physical (e.g. neuropathy, reduced mobility, and breathlessness) and psychological disorders (e.g. depression and post‐traumatic stress) (Cuthbertson 2007).

Psychological disorders, as well as anxiety and depression symptomatology, are commonly reported in patients and their caregivers after ICU admission. However, not every patient in ICU will develop psychological symptoms or a disorder; many individuals will be resistant or resilient to the effects of the ICU. Many who show distress will return quickly to normal function and some with a psychological disorder will follow a recovery trajectory (Layne 2007). Cross‐sectional and cohort studies have reported anxiety and depression conditions in patients recovering from ICU admission at a higher rate than the general population, at between 24% and 45% at six weeks (Myhren 2009), three months (Sukantarat 2007) and one year (Rattray 2005) after ICU admission. Anxiety and depression conditions often co‐exist with post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Samuelson 2007). PTSD is a serious disorder that follows the experience of a traumatic event and causes significant impairment in daily life (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The experience of the stressor generates feelings of intense fear, horror, helplessness, threat to life and physical integrity for the individual or someone to whom they have close affectional ties (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

In addition to anxiety, depression and PTSD, ICU survivors have often reported the absence of factual memory and the occurrence of delusional memories, including hallucinations or nightmares, throughout their recovery period (Myhren 2009). ICU‐related delusional memories are estimated to be present in around 30% to 70% of patients (Jones 2001; Ringdal 2009; Samuelson 2007), are often persecutory in nature, and tend to be recalled with high vividness and in substantial detail (Kiekkas 2010). The direct cause of these delusional memories is unknown but is thought to be related to a combination of medication (including adrenaline, corticosteroids, opiates and sedative drugs such as propofol and benzodiazepine), sleep deprivation, and critical illness (Jones 2001). The literature surrounding the relationship between recall of absent, traumatic or delusional memories and psychological disorders is mixed, with different authors finding positive (Jones 2001; Rattray 2010; Samuelson 2007; Schelling 2003) and negative associations (Granja 2008; Myhren 2009). The association between delusional memories and the psychological distress of ICU survivors has been mainly attributed to the strong vividness with long duration and high emotional content of these memories when compared with memories of real events (Ringdal 2009).

Research is now focusing on improving the long‐term holistic health outcomes of ICU survivors. Psychological distress, including anxiety, depression and PTSD symptomatology, compromises the recovery of ICU survivors and has been increasingly identified as a serious problem. The challenge lies with clinicians and researchers to develop strategies to effectively manage and treat this psychological distress alongside and following life‐saving physical treatment to maximize a patient's recovery.

Description of the intervention

One strategy that has been developed and implemented by clinical staff to treat the psychological distress prevalent in ICU survivors is patient diaries. Patient diaries provide a record of events which occur throughout a patient’s admission to the ICU. Following a timeline design, they provide a background to the cause of the patient’s ICU admission and an ongoing narrative outlining day‐to‐day activities. Diversity of practice exists throughout ICUs in implementing patient diaries, including variation in structural, content and process elements.

Emerging in Scandinavia in the 1970s to 1980s (Egerod 2011a), multiple authors have outlined the introduction and evaluation of patient diaries both within their local ICUs and internationally. Patient diaries are generally written prospectively and addressed personally to the individual patient. ICU staff provide an overall structure for the diary, with a cover and sometimes a preprinted introduction and glossary of terms and equipment (Akerman 2010; Egerod 2007; Egerod 2011b). Diaries are generally structured with a summary outlining the reason and event of admission to ICU, daily entries, and a final note on discharge or transfer from the ICU (Egerod 2007).

Primary authorship is predominantly the responsibility of the bedside ICU nurse. Some ICUs encourage the participation of the patient’s family, reporting the diaries as a potential focus for family empowerment and family‐centred care (Hale 2010; Roulin 2007). Current practice surrounding the provision of patient diaries to the patients is variable. ICUs differ between putting the diaries on the end of the bed when transferring a patient out of ICU to delivering a coordinated system of follow‐up and support for the patients and their families (Akerman 2010; Egerod 2007; Roulin 2007).

How the intervention might work

Personal diaries are used by individuals to reflect on significant aspects of their lives and serve as a vehicle for construction, reconstruction and narration of stories (Egerod 2009). Patient diaries differ from personal diaries in that they are not first‐person accounts. Nurses, hospital staff, family or friends vicariously write for the patient while the patient is unable to write due to altered state of consciousness, weakness or physical impairment (Egerod 2009).

Patients’ perceptions of intensive care are variable, often with very little or indeed nothing at all being remembered (Rattray 2010). For many patients their memories are unpleasant, fragmentary or frightening in nature (Rattray 2010). The aim of patient diaries is to provide ICU survivors with an accurate and informative collection of events, improving the memory recall of factual information. Delusional memories have been associated with anxiety, depression, post‐traumatic stress symptomatology (Jones 2001; Rattray 2005) and poor health‐related quality of life (Granja 2008). The aim of a diary is to provide a coherent narrative of the illness period, clarifying gaps in memory and diminishing the impact or dominance of imagined occurrences and hallucinations (Egerod 2011a). It has also been suggested that diaries can be used by relatives to encourage the healing process, after their own vicarious traumatic experience or as a basis for discussion about the patient’s illness experience (Egerod 2011a).

In comparison to this therapeutic view on patient diaries, there is, however, considerable concern regarding the method of providing this information and their use to reflect and reconstruct memories, thereby acting as a debriefing tool. Debriefing is a psychological treatment intended to reduce the psychological morbidity that arises after exposure to trauma (Rose 2002). It involves promoting some form of emotional process, catharsis or ventilation by encouraging recollection, ventilation or reworking of the traumatic event (Rose 2002). Since the 1990s debriefing has come under intense scrutiny, and a Cochrane review in 2002 (Rose 2002) found no evidence that single session individual psychological debriefing interventions prevented the onset of PTSD or reduced psychological distress. In addition to the lack of evidence, the majority of criticism was levelled at the timing of the debriefing, suggesting that during the immediate period after stress there is a substantial risk of causing retraumatization and inhibiting the individuals’ ability to normally process the traumatic event (Bledsoe 2002). Providing sensitive and private information without a supportive process could potentially cause significant psychological harm, negatively impacting a patient’s recovery.

The provision of psychological support to improve recovery after critical illness requires a complex intervention. As described by the Medical Research Council (Craig 2007), complex interventions comprise of a number of separate elements which seem to be essential to the proper functioning of the intervention, although the 'active ingredient' can be difficult to specify. Separating the content in patient diaries from the method of providing them (e.g. the clinicians skill, conversation, return to ICU) and other active elements of psychological support is difficult.

Why it is important to do this review

Annual estimates suggest that more than 20 million patients require treatment in ICUs worldwide in order to manage critical illnesses, injuries or exacerbations of chronic conditions (Adhikari 2011). The combined after‐effects of critical illness and the ICU experience have been linked to short and long‐term psychological compromise, which can significantly impair psychological and physical patient recovery (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012; Kiekkas 2010). This results in a significant emotional, physical and financial burden to patients, families and society. Clinicians have developed and used patient diaries as a tool to treat psychological distress. However, it has not been established whether this is an effective practice or whether it may have an adverse psychological impact due to individual patient factors, author emphasis, or the method of feedback support or lack thereof.

Objectives

To assess the effect of a diary versus no diary on patients, and their caregivers or families, during the patient's recovery from admission to an ICU.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) that evaluated the effectiveness of patient diaries for their impact on recovery after admission to ICU. CCTs refer to quasi‐randomized studies where, although the trial involves testing an intervention and control, concurrent enrolment and follow‐up of intervention and control‐treated groups, the method of allocation is not considered strictly random (see Box 6.3a, Lefebvre 2011). We included studies irrespective of publication status, year of publication or language. We excluded non‐randomized studies such as cohort studies because of the increased potential for bias. We also excluded cross‐over trials as this methodology is not suitable for evaluating an intervention that must be given at a specific time point.

Types of participants

We included all patients who were admitted to an ICU and their family members or caregivers. We included patients irrespective of age, country and critical illness severity.

Types of interventions

The primary intervention under investigation was patient diaries provided by ICU staff. We included any RCT or CCT in which the presence or absence of patient diaries was the only difference between treatment groups. For the purpose of this review, patient diaries were defined as a prospectively written collection of events which occurred during the ICU stay, authored by staff or relatives, or both (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012; Nydahl 2010).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Risk of PTSD in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a structured clinical interview (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

Risk of anxiety in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983).

Risk of depression in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity such as the HADS (Zigmond 1983).

Secondary outcomes

Risk of memory recall of ICU in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Risk of anxiety in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Risk of depression in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Carer or family member satisfaction, as described by the study investigator.

Health‐related quality of life in patients recovering from admission to ICU, as assessed using a tool with established reliability and validity.

Costs, as described by the study investigator; including implementation and healthcare utilization costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL2014, Issue 1, see Appendix 1 for detailed search strategy);

Ovid MEDLINE (1950 to January 2014, see Appendix 2);

Ovid EMBASE (1980 to January 2014, see Appendix 3);

PsycINFO (1950 to January 2014, see Appendix 4);

Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) database (1971 to January 2014);

EBSCOhost CINAHL (1982 to January 2014, see Appendix 5); and

Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index ‐ Science and Social Science and Humanities (1990 to January 2014, see Appendix 6).

There were no restrictions on the basis of date, language or publication status. We also searched the following clinical trial registers:

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Register (www.anzctr.org.au);

Clinical Trials.gov (www.clinicaltrial.gov);

Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com/mrct);

Hong Kong Clinical Trial Register (www.hkclinicaltrials.com);

Clinical Trials Registry ‐ India (www.ctri.in);

UK Clinical Trials Gateway (www.controlled‐trials.com/ukctr/); and

World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Trials Registry Portal (www.who.int/trialsearch).

Searching other resources

We handsearched bibliographies of all retrieved and relevant publications identified by these strategies for further studies. We contacted experts in the field to ask for information relevant to this review.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We combined the results of the searches and excluded duplicate records. Two review authors (AU and LA) independently assessed titles and abstracts of retrieved studies for relevance. After initial assessment we retrieved full versions of all potentially eligible studies. The same two review authors then independently checked the full papers for eligibility. We resolved discrepancies between review authors through mutual discussion and, where required, consulted a third independent review author (RB).

Data extraction and management

We extracted the details from eligible studies and summarized them using a data extraction sheet (see Appendix 7). The data extraction sheet was developed in conjunction with the Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group (CARG). Two review authors (AU and LA) extracted data independently and then cross‐checked for accuracy and agreement. Where necessary,we resolved any discrepancies though discussion and arbitration with a third review author (RB). We included studies that had been published in duplicate once only. When data were missing from the papers, we contacted study authors to retrieve the missing information.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (AU and LA) independently assessed each eligible study for quality and bias using the 'Risk of bias' assessment tool described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion and when we could not reach a consensus a third author (RB) arbitrated. The bias tool addresses six specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation and concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other issues which may potentially bias the study (Higgins 2011). We reported the 'Risk of bias' table for each eligible study and outcome using the categories of low, high or unclear risk of bias.

We intended to conduct sensitivity analyses to determine whether excluding studies at high risk of bias would affect the results of the meta‐analysis. However, due to the small number of studies, we have not performed a meta‐analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

We generated measures of treatment effect for each of the reported categorical dichotomous outcomes, providing risk ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A meta‐analysis was not conducted due to the small number of studies eligible for inclusion in the review.

Unit of analysis issues

There were no unit of analysis issues as the patient and caregivers were the unit of analysis for all included studies.

Dealing with missing data

Authors of included studies were emailed to ask for further information and clarification of key aspects of their study methods. All contact authors responded (Jones 2010; Jones 2012; Knowles 2009), with one author group able to provide all information required (Jones 2010).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to consider clinical, methodological and statistical heterogeneity. Due to the small number of included studies, we have not undertaken a meta‐analysis, so assessment of statistical heterogeneity has not been performed. Clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the included studies are discussed within the conclusions section of this review.

Assessment of reporting biases

We intended to use a funnel plot to identify small‐study effects (Egger 1997). Any asymmetry of the funnel plot may indicate possible publication bias. We also intended to explore other reasons for asymmetry, such as selection bias, methodological quality, heterogeneity, artefact or chance, as described in Section 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). However, due to the small number of studies, we were unable to carry out these assessments.

Data synthesis

We have conducted a structured narrative summary of the studies reviewed and calculated RR and 95% CI from the single studies. However, due to the small number of included studies, we have not undertaken any further meta‐analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We have not undertaken any subgroup analysis for this review.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to exclude trials at high risk of bias, such as quasi‐randomized trials and compare random‐effects model and fixed‐effect model estimates of each outcome variable. However, due to the small number of studies included in this review, a sensitivity analysis has not been completed.

Summary of findings

Due to the small number of included studies, a summary of findings table was not completed. We did assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with the outcomes in our review using the principles of the GRADE system (Guyatt 2008). The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence considers within study risk of bias (methodologic quality), the directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The results of the search and selection of studies are summarized in the PRISMA study flow diagram Figure 1 (Liberati 2009). The search of electronic bibliographic databases identified 1485 records, of which 46 were duplicate records. Searches of clinical trial registries did not identify additional studies, but the handsearching of bibliographies identified one study for potential inclusion. Of the 1439 titles screened, 1427 were excluded. Twelve full text articles were screened for potential inclusion, of which nine were excluded, with the reasons for exclusion described in Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Three studies were eligible to be included in the review. The three eligible studies are described in Characteristics of included studies.

Jones and colleagues undertook a RCT involving patients and family members, and reported their results in two separate publications (Jones 2010; Jones 2012).

Population and setting

Two studies focused on patients recovering from ICU admission (Jones 2010; Knowles 2009), and one focused on family members (Jones 2012).

ICU patients

The Jones 2010 study was conducted in six European countries (Sweden, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Portugal, United Kingdom) with two ICU sites per country. Participants (N = 322) were admitted to ICU for at least 72 hours and ventilated for at least 24 hours.

Knowles 2009 studied 36 adult participants recovering from admission to a single British ICU. Participants were admitted to ICU for at least 48 hours and were not necessarily ventilated. Both studies excluded participants who had pre‐existing psychotic illnesses. Knowles 2009 also excluded patients who had a diagnosis of dementia or an organic memory problem. Jones 2010 excluded patients who were too confused to give informed consent.

Family members of ICU patients

From the original study by Jones 2010, a substudy of family members was undertaken and reported in Jones 2012. They studied 30 family members of the previous study participants from ICUs in the United Kingdom and Sweden. No specific exclusion criteria were reported.

Interventions and comparisons

All studies (Jones 2010;Jones 2012; Knowles 2009) compared the use of patient diaries to no diaries, with participants randomly assigned to one or the other.

Patient diary structure and content

All studies described the patient diary as being a daily record of the patient's ICU stay and the study protocol dictated a standardization of the patient diary content via the use of either a template (Jones 2010; Jones 2012) or topic headings (e.g. patient's appearance and condition, events on the ward) (Knowles 2009). Jones 2010 and Jones 2012 included photographs of the participant during their ICU in the patient diary; Knowles 2009 did not.

Patient diary authorship

Diaries were authored by a multidisciplinary group of ICU staff with (Jones 2010; Jones 2012) or without (Knowles 2009) family member involvement.

Delivery of the patient diary

In the Knowles 2009 study, the diary was handed over by a specifically trained ICU nurse consultant, who read it with the patient and answered any questions arising in a verbal feedback session. In the Jones 2010 and Jones 2012 studies the diary was introduced, either face‐to‐face or over the phone, by a research nurse or a medical doctor who ensured that the participants understood its contents.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

PTSD using clinical interview in ICU patients

No study reported the risk of PTSD assessed using a structured clinical interview, as defined by American Psychiatric Association 2013.

Anxiety and depression in ICU patients

Knowles 2009 reported the risk of anxiety and depression in patients recovering from admission to ICU using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983).

Secondary outcomes

Memory recall in ICU patients

Jones 2010 reported delusional ICU memory recall using ICU Memory Test (ICU‐MT) (Jones 2000).

Post‐traumatic symptomatology

Jones 2010 reported post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in patients and family members (Jones 2012) using the Post‐Traumatic Stress Syndrome Screening Tool 14 (PTSS‐14) (Twigg 2008)

Anxiety, depression, satisfaction in family members or caregivers

No study reported the effectiveness of patient diaries on anxiety, depression or satisfaction in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU.

Health‐related quality of life for ICU patients

No study reported the effectiveness of patient diaries on the health‐related quality of life for patients recovering from ICU admission.

Costs

No study reported cost of the patient diary.

Excluded studies

We excluded nine studies at the full text review stage because they did not use an RCT or CCT design. These included observational studies (Backman 2001; Bagger 2006; Hale 2010; Hayes 2008; MacDonald 2011; Robson 2008), a prospective cohort study with retrospective reference group (Backman 2010), time‐series design (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012) and a commentary paper (AACN 2012).

Risk of bias in included studies

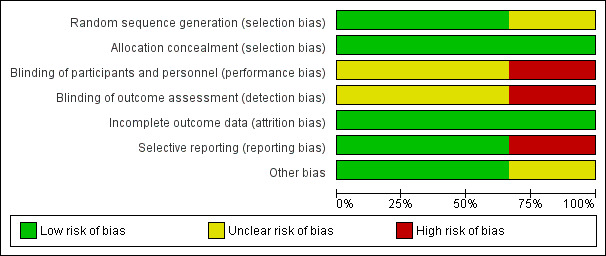

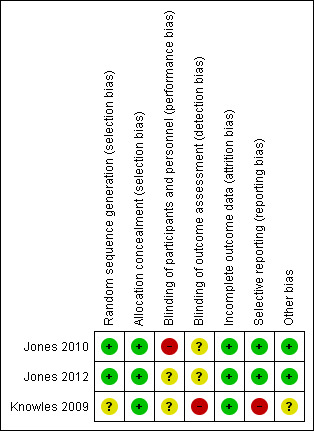

Details of the risk of bias assessment for the eligible studies are given in Characteristics of included studies and in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Jones 2010 and, by extension, Jones 2012 reported a detailed computerized block randomization process and effective measures for allocation concealment. Knowles 2009 reported unclear information regarding their sequence generation and allocation concealment within their publication. However, when privately emailed, they reported the use of adequate allocation concealment involving opaque sealed envelopes.

Blinding

Due to the unblinded nature of the intervention, performance bias was inevitable, but it was possible for some outcomes to be assessed without knowledge of the participants' allocation. Knowles 2009 reported that the principal investigator who undertook the outcome assessment was not blinded, introducing the possibility of bias. The outcomes from Jones 2010 and Jones 2012 included in the review were by self‐report tools and, due to the nature of the intervention, the participants were aware of their study group. It was not clear whether the researchers collating the questionnaire results were blinded to study group.

Incomplete outcome data

All studies reported minimal losses after randomization, demonstrating minimal attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Jones 2010 and Jones 2012 registered the clinical trial, Knowles 2009 did not register their trial and stated they did not report all outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no other potential sources of bias in Jones 2010 and Jones 2012. In Knowles 2009, there were significant differences between control and experimental groups including ICU length of stay and severity of critical illness, both of which are associated with increased risk of PTSD.

Effects of interventions

Due to the small number of studies eligible for inclusion in our review and the diverse outcomes reported, we were not able to undertake a meta‐analysis. A table summarizing the outcomes from the single studies has been provided in Table 1.

1. Diaries for the recovery from critical illness: summary of results from single studies.

| Outcomes | Study | Incidence | Number of participants | Quality of the evidence: GRADE |

|

Risk of anxiety in patients recovering from admission to ICU Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983) Follow‐up: 3 weeks from initial assessment |

Knowles 2009 |

Patient diary: 2 of 18 participants (11.1%) had the likely presence of clinically significant anxiety. No patient diary: 7 of 18 participants (38.9%) had the likely presence of clinically significant anxiety. |

36 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Risk of depression in patients recovering from admission to ICU Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond 1983) Follow‐up: 3 weeks from initial assessment |

Knowles 2009 |

Patient diary: 3 of 18 participants (16.7%) had the likely presence of clinically significant depression. No patient diary: 8 of 18 participants (44.4%) had the likely presence of clinically significant depression. |

36 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low 1,2 |

|

Risk of memory recall of ICU in patients recovering from admission to ICU Intensive Care Unit Memory Tool (Jones 2000) Follow‐up: 3 months from ICU admission |

Jones 2010 |

Patient diary: 85 of 162 participants (55%) had recall of delusional ICU memories. No patient diary: 81 of 160 participants (52%) had recall of delusional ICU memories. |

322 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2 |

|

Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in patients recovering from admission to ICU Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder‐Related Symptoms Screening Tool 14 (Twigg 2008) Follow‐up: 3 months from ICU admission |

Jones 2010 |

Patient diary: The median post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in the patient diary group was 24 (SD 11.6)3 No patient diary: The median post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in the no patient diary group was 24 (SD 11.6) 3 |

322 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2 |

|

Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder‐Related Symptoms Screening Tool 14 (Twigg 2008) Follow‐up: 3 months from ICU admission |

Jones 2012 |

Patient diary: The median post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in the patient diary group was 19 (range 14 to 28) 3 No patient diary: The median post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in the no diary group was 28 (range 14 to 38) 3 |

30 | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low 2 |

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||

| CI: Confidence interval | ||||

1 Results are from a single study at risk of bias regarding blinding of outcome assessment and participants. 2 Results are from a single study with few patients and few events and thus have wide confidence intervals around the estimate of the effect. 3 Confidence intervals not provided.

Primary outcomes

1. Risk of PTSD in patients recovering from admission to ICU

No study reported the risk of PTSD assessed using a structured clinical interview, as defined by American Psychiatric Association 2013.

2. Risk of anxiety in patients recovering from admission to ICU

Knowles 2009 reported no significant difference in risk of scoring 8 or more on the anxiety subscale of HADS for the diary group (diary group, 11%, N = 2/18, versus no diary, 39%, N = 7/18; RR 0.29, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.19).

3. Risk of depression in patients recovering from admission to ICU

Knowles 2009 reported no significant difference in risk of scoring 8 or more on the depression subscale of HADS in the diary group (diary group, 17%, N = 3/18, versus no diary group, 44%, N = 8/18; RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.19).

Secondary outcomes

1. Risk of ICU memory recall in patients recovering from admission to ICU

Jones 2010 reported no significant difference between groups in delusional memories with the ICU memory tool (diary group, 55%, N = 85/162, versus no diary group, 52%, N = 81/160; RR 1.04 95% CI 0.84 to 1.28).

2. Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in patients recovering from admission to ICU

Jones 2010 reported no difference in median scores of participants who received patient diaries (24; SD 11.6), in comparison to no diary (24; SD 11.6) using the Post‐Traumatic Stress Syndrome 14 (PTSS‐14) (Twigg 2008).

3. Post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in family members or care givers of patients recovering from admission to ICU

Jones 2012 reported that at three months after admission to ICU, there was a statistically significant (P = 0.03) reduction in median scores of participants who received patient diaries (19; range 14 to 28), in comparison to no diary (28; range 14 to 38) using the PTSS‐14 (Twigg 2008).

No studies reported anxiety or depression in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU, caregiver or family member satisfaction, health‐related quality of life in patients recovering from admission to ICU or costs of the diary intervention.

Discussion

Summary of main results

No studies reported our first primary outcome measure describing the risk of PTSD in patients recovering from admission to ICU using a structured clinical interview. We applied this definition a priori as it is supported by the American Psychiatric Association 2013 as the gold standard for the diagnosis of PTSD. Jones 2010, when attempting to reduce the risk of detection bias in the diagnosis of PTSD, trained the interviewers in the administration, but not the meaning or scoring, of the items in the instrument. The use of an uninformed clinician makes the interview no longer diagnostic, and limits its reliability as an assessment tool. Therefore, we did not include these results in the Cochrane Review. There is currently no general agreement on which outcomes should be measured in trials focusing on psychological recovery after critical illness. Such agreement would be beneficial to aid consistency across relevant trials (Blackwood 2014).

A single study (Knowles 2009) reported the potential effectiveness of patient diaries to reduce the risk of anxiety and depression in comparison to no patient diary. However, these results were not statistically significant and the study was methodologically limited due to poor sample size. Knowles 2009 reported the cut‐off score of "clinically significant anxiety and depression" of eight. While "caseness" of anxiety and depression is best described by a score range of 11 or higher (Snaith 2003; Zigmond 1983), the score of eight or greater is "just suggestive of the presence of the respective state".

There was no evidence of an effect on post‐traumatic stress symptomatology between patients who did or did not receive patient diaries three months after ICU admission, although there was a significant decrease in post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in the intervention arm for family members. The reliability of these results is limited as the chosen instrument for measuring post‐traumatic symptomatology used in these studies (PTSS‐14) has not been adequately validated in the revised form after four new items were added to the original PTSS‐10. While the PTSS‐14 has been correlated with a better measure in a small study (N = 44), it was designed as an early screening tool that incomprehensively lists post‐traumatic stress symptoms, but does not link the symptoms to a trauma or event (Twigg 2008).

There is evidence to suggest that patients' psychological health after the ICU continues to be problematic beyond three months, suggesting that the follow‐up timeline in each of these included studies was insufficient (Aitken 2014; Davydow 2009; Jackson 2007). For the study undertaken by Knowles 2009, the reduction of anxiety and depression was measured only three weeks after receiving the patient diary intervention. Further studies are needed to assess the long‐term impact of patient diaries on depression, anxiety and post‐traumatic stress.

The recall of delusional memories was comparable between study groups. Researchers (Egerod 2011a) have previously discussed the role of the patient diary in the provision of a coherent narrative of the illness period, diminishing the impact or dominance of imagined occurrences and hallucination.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The studies included in this systematic review addressed some important outcomes related to the effectiveness of patient diaries to support recovery from critical illness. However, other outcomes including risk of PTSD in patients recovering from admission to ICU, anxiety or depression in caregivers or family members of patients recovering from admission to ICU, caregiver or family member satisfaction, health‐related quality of life in patients recovering from admission to ICU or costs of daily implementation were not reported. The single study outlining the risk of anxiety and depression for patients recovering from admission to ICU had only 36 participants. More research is needed to inform these outcomes. In addition, all studies included in this review were undertaken in adult ICUs within Europe and the UK. Generalizability of the results is limited to these populations and geographical areas.

None of the included studies adequately described the multi‐dimensionality of the patient diary intervention, in terms of its characteristics as a complex intervention. The manner and time in which the patient diary was provided, the skills and qualification of the clinician providing the patient diary and the co‐interventions that these entail have not been adequately explored. These elements may have an important contribution to the effectiveness of a patient diary to improve, or worsen, patient and family member recovery.

The studies included within this review were carried out in European countries including Sweden, Italy, Denmark, Norway, Portugal and the United Kingdom. This is in accordance with the majority of reported patient diary usage which has been within Europe, particularly Scandinavia (Akerman 2010; Egerod 2011a; Egerod 2011b; Gjengedal 2010) and the United Kingdom (Combe 2005; Hale 2010).

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence contained in the review has been assessed using the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008). While publication bias, indirectness and inconsistency were not established, the methodologic quality and precision of the effect estimates was low to very low. This has meant that the overall confidence with the quality of evidence contained in the review is low.

Potential biases in the review process

Clearly described procedures were followed to prevent potential bias in the review process. A careful literature search was conducted and the methods used are transparent and reproducible. None of the review authors has reported any conflict of interest.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Observational (Backman 2001; Bagger 2006; Hale 2010; Hayes 2008; MacDonald 2011; Robson 2008), prospective cohort with a retrospective reference group (Backman 2010), time‐series (Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012) and qualitative (Bergbom 1999; Combe 2005; Egerod 2010; Engstrom 2009; Storli 2009) studies have reported the success and importance of patient diaries in the clinical setting. Our review has demonstrated the paucity of randomized controlled trials evaluating patient diaries.

There has not been a systematic review previously conducted on patient diaries for recovery from critical illness.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Currently minimal evidence from RCTs is available to evaluate the effectiveness of patient diaries to promote recovery from critical illness for patients and caregivers or family members. Studies limited by small sample sizes have examined the potential of diaries to reduce post‐traumatic stress symptomatology in family members. However, there is currently inadequate evidence to support their effectiveness in improving psychological recovery after critical illness for patients and their family members. Fundamental concerns regarding the safety and effectiveness, specifically the method in which patient diaries are provided, needs to be considered. It has not been established whether patient diaries are an effective practice or whether it may have an adverse psychological impact.

Implications for research.

Further research needs to be undertaken to ascertain the effect of patient diaries for patients and caregivers or family members recovering from ICU. Use of patient diaries for patients recovering from ICU admission is becoming more common, but it is not clear whether it is a safe and effective practice, therefore, further research is required.

When designing future research into the effectiveness of patient diaries, researchers should also carefully consider the complexity of the patient diary as an intervention, and consider the active components that may impact the diaries effectiveness. The entire intervention surrounding the development and provision of patient diaries, including content, process, timeline and personnel involved, needs to be adequately described within the research to enable future replication and generalizability. Multi‐dimensional aspects of psychological recovery including anxiety, depression and symptoms of PTSD should be assessed for at least six and preferably twelve months after discharge from ICU (Rattray 2010). Researchers should continue to plan their protocols to minimize risk of bias and should report clearly in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines (Schulz 2010). Researchers should also carefully consider their choice of outcome measures, to ensure the validity of their research.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2019 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

Acknowledgements

We thank Jane Cracknell (Managing Editor, Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group) and Karen Hovhannisyan (Trials Search Co‐ordinator, Cochrane Anaesthesia Review Group) for their assistance in the preparation of the protocol and review.

We would like to thank Bronagh Blackwood (content editor), Nathan Pace (statistical editor), Christina Jones, Megan Prictor, Louise Rose (peer reviewers), and Robert Wylie (consumer referee) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NH&MRC) has provided funding for this review from its Centre of Research Excellence scheme, which funds one or more of the authors.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor: [Patients] explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor: [Caregivers] explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor: [Narration] explode all trees #4 (#1 or #2) and #3 #5 ((patient* or caregiver*) and (diaries or diary or (narrat* and (coherent or outlining)))) #6 #4 or #5 #7 MeSH descriptor: [Intensive Care Units] explode all trees #8 MeSH descriptor: [Critical Care] explode all trees #9 MeSH descriptor: [Critical Illness] explode all trees #10 ((critical* near ill*) or ((intensive care unit* or ICU) and (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*))) #11 #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 #12 #6 and #11

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (OvidSP) search strategy

1. ((patient* or caregiver*) adj5 (diaries or diary or (narrat* adj3 (coherent or outlining)))).af. or ((exp Patients/ or exp Caregivers/) and exp Narration/) 2. ((critical* adj3 ill*) or ((intensive care unit* or ICU) adj5 (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*))).af. or exp Intensive Care Units/ or exp Critical Care/ or exp Critical Illness/ 3. 1 and 2

Appendix 3. EMBASE (Ovid SP) search strategy

1 ((patient* or caregiver*) adj3 (diaries or diary or (narrat* adj3 (coherent or outlining)))).mp. or ((exp patient/ or exp caregiver/) and exp verbal communication/) 2 ((critical* adj3 ill*) or ((intensive care unit* or ICU) adj3 (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*))).mp. or exp intensive care unit/ or exp intensive care/ or exp critical illness/ 3 1 and 2

Appendix 4. PsycINFO (Ovid SP) search strategy

1 ((patient* or caregiver*) adj3 (diaries or diary or (narrat* and (coherent or outlining)))).af. or ((exp Patients/ or exp Caregivers/) and (exp Narratives/ or exp Journal Writing/)) 2 ((critical* and ill*) or ((intensive care unit* or ICU) and (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*))).af. or exp Intensive Care/ 3 1 and 2

Appendix 5. CINAHL (EBSCOhost) search strategy

S1 ((patient* or caregiver*) and (diaries or diary or (narrat* and (coherent or outlining)))) OR ((MM "Narratives") AND ((MH "Patients+") OR (MM "Caregivers"))) S2 (MH "Intensive Care Units+") OR (MH "Critical Care+") OR (MM "Critical Illness") OR ((critical* and ill*) or ((intensive care unit* or ICU) and (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*))) S3 S1 and S2

Appendix 6. ISI Web of Science search strategy

#1 TS=((patient* or caregiver*) SAME (diaries or diary or (narrat* AND (coherent or outlining)))) #2 TS=(critical* SAME ill*) or TS=((intensive care unit* or ICU) SAME (recover* or delusional memor* or psychological distress or anxiety or depression or PTSD or bedside nurs* or family or caregiver* or recuperate*)) #3 #1 and #2

Appendix 7. Data extraction form

CARG

Data collection form

Intervention review – RCTs only

| Review title or ID |

| Study ID(surname of first author and year first full report of study was published e.g. Smith 2001) |

| Report IDs of other reports of this study(e.g. duplicate publications, follow‐up studies) |

|

Notes: |

1. General Information

| Date form completed(dd/mm/yyyy) | |

| Name/ID of person extracting data | |

|

Report title (title of paper/ abstract/ report that data are extracted from) |

|

|

Report ID (ID for this paper/ abstract/ report) |

|

| Reference details | |

| Report author contact details | |

|

Publication type (e.g. full report, abstract, letter) |

|

|

Study funding sources (including role of funders) |

|

|

Possible conflicts of interest (for study authors) |

|

| Notes: | |

2. Study Eligibility

| Study Characteristics |

Eligibility criteria |

Yes | No | Unclear |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|

| Type of study | Randomized Controlled Trial | |||||

| Controlled Clinical Trial (quasi‐randomized trial) |

||||||

|

Participants |

Patient’s or family members/carers recovering from admission to an ICU | |||||

| Types of intervention | Prospective patient diaries |

|||||

| Types of outcome measures |

|

|||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

|

||||||

| INCLUDE | EXCLUDE | |||||

|

Reason for exclusion |

||||||

| Notes: | ||||||

DO NOT PROCEED IF STUDY EXCLUDED FROM REVIEW

3. Population and setting

|

Description Include comparative information for each group (i.e. intervention and controls) if available |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

||

|

Population description (from which study participants are drawn) |

|||

|

Setting (including location and social context) |

|||

| Inclusion criteria | |||

| Exclusion criteria | |||

| Method/s of recruitment of participants | |||

|

Informed consent obtained |

Yes No Unclear |

||

| Notes: | |||

4. Methods

|

Descriptions as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

||

| Aim of study | |||

| Design(e.g. parallel, cross‐over, cluster) | |||

|

Unit of allocation (by individuals, cluster/groups or body parts) |

|||

| Start date | |

||

| End date | |

||

| Total study duration | |||

| Ethical approval needed/obtained for study | Yes No Unclear |

||

| Notes: | |||

5. Risk of bias assessment

See Chapter 8 of The Cochrane Handbook

| Domain |

Risk of bias |

Support for judgement |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear | |||

|

Random sequence generation (selection bias) |

|||||

|

Allocation concealment (selection bias) |

|||||

|

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) |

Outcome group: All/ |

||||

| (if required) |

Outcome group: |

||||

|

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) |

Outcome group: All/ |

||||

| (if required) |

Outcome group: |

||||

|

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) |

|||||

|

Selective outcome reporting? (reporting bias) |

|||||

| Other bias | |||||

| Notes: | |||||

6. Participants

Provide overall data and, if available, comparative data for each intervention or comparison group.

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|

|

Total no. randomized (or total pop. at start of study for NRCTs) |

||

| Baseline imbalances | ||

|

Withdrawals and exclusions (if not provided below by outcome) |

||

| Age | ||

| Sex | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Severity of illness | ||

| Co‐morbidities | ||

| Other treatment received(additional to study intervention) | ||

| Other relevant sociodemographics | ||

| Subgroups measured | ||

| Subgroups reported | ||

| Notes: | ||

7. Intervention groups

Copy and paste table for each intervention and comparison group

Intervention Group

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|

| Group name | ||

| No. randomized to group | ||

| General content of diary | ||

| Author/s of diary | ||

| Inclusion of photographs | ||

| Method of providing the diary to the patient/family (including staff present, co‐interventions at that time) | ||

| Timing of providing the diary to the patient/family | ||

| Other co‐interventions (including follow‐up) | ||

| Economic variables | ||

| Resource requirements to replicate intervention | ||

| Notes: | ||

Comparison Group

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|

| Group name | ||

| No. randomized to group | ||

| Description of standard ICU care received (e.g. follow‐up) | ||

| Co‐interventions | ||

| Economic variables | ||

| Resource requirements to replicate intervention | ||

| Notes: | ||

8. Outcomes

Copy and paste table for each outcome.

Outcome 1

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

||

| Outcome name | |||

| Time points measured | |||

| Time points reported | |||

| Outcome definition(with diagnostic criteria if relevant) | |||

| Person measuring/reporting | |||

|

Unit of measurement (if relevant) |

|||

| Scales: upper and lower limits(indicate whether high or low score is good) | |||

| Is outcome/tool validated? | Yes No Unclear |

||

| Imputation of missing data (e.g. assumptions made for ITT analysis) | |||

|

Assumed risk estimate (e.g. baseline or population risk noted in Background) |

|||

| Power | |||

| Notes: | |||

9. Results

Copy and paste the appropriate table for each outcome, including additional tables for each time point and subgroup as required.

Dichotomous outcome 1

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|||||

| Comparison | ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Subgroup | ||||||

| Timepoint (specify whether from start or end of intervention) | ||||||

| Results | Intervention | Comparison | ||||

| No. events | No. participants | No. events | No. participants | |||

| No. missing participants and reasons | ||||||

| No. participants moved from other group and reasons | ||||||

| Any other results reported | ||||||

|

Unit of analysis(by individuals, cluster/groups or body parts) |

||||||

| Statistical methods used and appropriateness of these methods(e.g. adjustment for correlation) | ||||||

| Reanalysis required?(specify) | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| Reanalysis possible? | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| Reanalysed results | ||||||

| Notes: | ||||||

Continuous outcome

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|||||||||

| Comparison | ||||||||||

| Outcome | ||||||||||

| Subgroup | ||||||||||

| Timepoint (specify whether from start or end of intervention) | ||||||||||

| Post‐intervention or change from baseline? | ||||||||||

| Results | Intervention | Comparison | ||||||||

| Mean | SD (or other variance) | No. participants | Mean | SD (or other variance) | No. participants | |||||

| No. missing participants and reasons | ||||||||||

| No. participants moved from other group and reasons | ||||||||||

| Any other results reported | ||||||||||

|

Unit of analysis (individuals, cluster/ groups or body parts) |

||||||||||

| Statistical methods used and appropriateness of these methods(e.g. adjustment for correlation) | ||||||||||

| Reanalysis required?(specify) | Yes No Unclear |

|||||||||

| Reanalysis possible? | Yes No Unclear |

|||||||||

| Reanalysed results | ||||||||||

| Notes: | ||||||||||

Other outcome

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|||||

| Comparison | ||||||

| Outcome | ||||||

| Subgroup | ||||||

| Timepoint (specify whether from start or end of intervention) | ||||||

| Results | Intervention result | SD (or other variance) | Control result | SD (or other variance) | ||

| Overall results | SE (or other variance) | |||||

| No. participants | Intervention | Control | ||||

| No. missing participants and reasons | ||||||

| No. participants moved from other group and reasons | ||||||

| Any other results reported | ||||||

| Unit of analysis(by individuals, cluster/groups or body parts) | ||||||

| Statistical methods used and appropriateness of these methods | ||||||

| Reanalysis required?(specify) | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| Reanalysis possible? | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| Reanalysed results | ||||||

| Notes: | ||||||

10. Applicability

| Have important populations been excluded from the study?(consider disadvantaged populations, and possible differences in the intervention effect) | Yes No Unclear |

|

| Is the intervention likely to be aimed at disadvantaged groups?(e.g. lower socioeconomic groups) | Yes No Unclear |

|

|

Does the study directly address the review question? (any issues of partial or indirect applicability) |

Yes No Unclear |

|

| Notes: | ||

11. Other information

|

Description as stated in report/paper |

Location in text (pg & ¶/fig/table) |

|

| Key conclusions of study authors | ||

| References to other relevant studies | ||

| Correspondence required for further study information(from whom, what and when) | ||

| Notes: | ||

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Jones 2010.

| Methods | Pragmatic, randomized controlled trial in six European countries, with two ICUs per country. | |

| Participants | 352 adult ICU patients randomized, 322 completed study. Inclusion criteria: Admitted to ICU for > 72 hours; ventilated for > 24 hours. Exclusion criteria: Too confused to give informed consent; pre‐existing psychotic illness (e.g. schizophrenia); diagnosed PTSD. |

|

| Interventions | ICU diary: a daily record of the patient's ICU stay, written in everyday language and accompanied by photographs. Authored by multidisciplinary healthcare staff and family. Diaries standardized via the provision of guidelines to each centre. The diary was introduced to the patient by a research nurse or doctor who ensured that they understood its contents but did not give any advice on what to do with it. This was done either face‐to‐face or over the phone. Controls: Received standard care at each setting. At several of the study sites, this involved giving patients verbal information about their illness prior to discharge from hospital. All control participants received the ICU diary after the final outcome assessment. |

|

| Outcomes | Patient ICU memory recall: assessed using ICUMT at randomization (1‐month post ICU discharge) and 3‐month follow‐up. Patient post‐traumatic stress symptomatology: assessed using post‐traumatic stress‐14 at randomization and 3‐month follow‐up. Patient PTSD: assessed using post‐traumatic diagnostic scale with a blinded clinician within a 'diagnostic' interview at the 3‐month follow‐up. Not included within this systematic review. |

|

| Notes | ICU: Intensive care unit | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Randomised in blocks of six through computerised random number generation" (p. 4) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Assigned to treatment or control at one‐month using closed, non‐transparent envelope technique" (p. 4) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "Impractical to guarantee blinding of allocation of the diary as patients would volunteer their use" (p. 3). |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "In order to reduce bias and ensure blinding of the diagnosis of post traumatic stress disorder at the three‐month follow‐up, the researchers were only trained to interview and administer the post‐traumatic diagnostic scale but were not made aware of the scoring calculation or in what way each question contributed to the score and final diagnosis" (p. 3). For the outcomes included within this review, assessment was made via questionnaire by the participants, who were not blinded to the intervention. It is not known whether the researchers summarising these questionnaire results were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Less than 10% attrition. Well described reasons for participant withdrawal from the study. (p. 4) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Research protocol well described, clinical trial registered. All outcomes reported. (p. 1, 3, 5) |

| Other bias | Low risk | Nil |

Jones 2012.

| Methods | Pragmatic, randomized controlled trial in two European ICUs. | |

| Participants | 36 family members of adult ICU patients randomized; 30 completed the study. Inclusion criteria: Family members of those recruited to Jones 2010. That is, patients who were admitted to ICU for > 72 hours; ventilated for > 24 hours. Exclusion criteria: Too confused to give informed consent; pre‐existing psychotic illness (e.g. schizophrenia); diagnosed post‐traumatic stress disorder. |

|

| Interventions | ICU diary: a daily record of the family members' experiences of patients' ICU stay, written in everyday language and accompanied by photographs. Authored by multidisciplinary healthcare staff and family. Diaries standardized via the provision of guidelines to each centre. The diary was introduced to the family member by a research nurse or doctor who ensured that they understood its contents but did not give any advice on what to do with it. This was done either face‐to‐face or over the phone. Controls: Received standard care at each setting. At several of the study sites, this involved giving family members verbal information. All control participants received the ICU diary after the final outcome assessment. |

|

| Outcomes | Family member post‐traumatic stress symptomatology: assessed using post‐traumatic stress‐14 at randomization and 3‐month follow‐up. | |

| Notes | ICU: Intensive care unit | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Just before randomization to the study group" (p. 174): Random sequence generation as reported by Jones 2010: Quote: "Randomised in blocks of six through computerised random number generation" (p. 4) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment as reported by Jones 2010: Quote: "Assigned to treatment or control at one‐month using closed, non‐transparent envelope technique" (p. 4) |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Not able to blind participants and personnel to their allocation, as reported by Jones 2010. |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Assessment was made via questionnaire by the participants, who were not blinded to the intervention. It is not known whether the researchers summarising these questionnaire results were blinded. |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Less than 10% attrition. Well described reasons for participant withdrawal from the study. (p. 174) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Research protocol well described, clinical trial registered. All outcomes reported. (p. 173, 4, 5) |

| Other bias | Low risk | Nil |

Knowles 2009.

| Methods | Pragmatic, randomized controlled trial in a single British ICU. | |

| Participants | 36 adult ICU patients. Inclusion criteria: Admitted to ICU for > 48 hours. Exclusion criteria: Age < 18 years or > 85 years; admitted following a deliberate suicide attempt; currently experiencing clinically significant psychological symptomatology which predated their admission to ICU; history of dementia or other organic memory problems. |

|

| Interventions | ICU diary: a daily record of the patient's ICU stay, authored by multidisciplinary healthcare staff. Diaries standardized under the headings: patient's appearance and condition, events on the ward, details of any treatment or procedures administered in lay language and the names of any visitors. The diary was handed over by the ICU nurse consultant who read it with the patient and answered questions in a verbal feedback session. Controls: Received standard care. All control participants received the ICU diary after the final outcome assessment. |

|

| Outcomes | Anxiety: assessed using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; at initial assessment (1‐month post ICU discharge) and 3 weeks later. Depression: assessed using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; at initial assessment (1‐month post ICU discharge) and 3 weeks later. |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Randomly allocated" (p. 185) |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Quote: "Presealed envelopes" (p.185) Private correspondence with authors: "Opaque envelopes were used". |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: "ICU staff were blind to the patients' group membership, but the participants themselves... were not". (p. 185) |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "The principal investigator (who conducted the psychological assessment) was not (blinded)". (p. 185) |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Flow diagram regarding recruitment and attrition provided. No loss to follow‐up. (p. 186) |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | No protocol or clinical trial registry. Not all outcomes reported. Quote: "findings from the other assessment tools will be presented in a separate paper" (p. 186). No subsequent publication located. |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | Significant differences between control and experimental groups including ICU length of stay, APACHE II (p. 186‐187) which are associated with increased risk of PTSD. |

Abbreviations:

APACHE II = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ICU = intensive care unit; ICUMT = intensive care unit memory tool; P = page; PTSD = post‐traumatic stress disorder.

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| AACN 2012 | Commentary paper on Jones 2012 |

| Backman 2001 | Observational study |

| Backman 2010 | Prospective cohort study with retrospective reference group |

| Bagger 2006 | Observational study |

| Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012 | Time‐series design |

| Hale 2010 | Observational study |

| Hayes 2008 | Observational study |

| MacDonald 2011 | Observational study |

| Robson 2008 | Observational study |

Differences between protocol and review

Due to the small number of studies contained within the review, we were unable to undertake the meta‐analyses or provide a summary of findings table planned in the protocol (Ullman 2013).

Contributions of authors

Amanda J Ullman (AU), Leanne M Aitken (LA), Janice Rattray (JR), Justin Kenardy (JK) Robyne Le Brocque (RLB), Stephen MacGillivray (SM), Alastair M Hull (AH)

Conceiving the review: all authors

Co‐ordinating the review: AU

Undertaking manual searches: AU

Screening search results: AU and LA

Organizing retrieval of papers: AU

Screening retrieved papers against inclusion criteria: AU and LA

Appraising quality of papers: AU, LA and RLB

Abstracting data from papers: AU, LA and RLB

Writing to authors of papers for additional information: AU

Providing additional data about papers: AU

Obtaining and screening data on unpublished studies: AU and LA

Data management for the review: AU

Entering data into Review Manager (RevMan 5.2): AU

RevMan statistical data: AU and SM

Other statistical analysis not using RevMan: AU

Interpretation of data: all authors

Statistical inferences: SM

Writing the review: all authors

Securing funding for the review: N/A

Performing previous work that was the foundation of the present study: all authors

Guarantor for the review (one author): AU

Person responsible for reading and checking review before submission: AU

Sources of support

Internal sources

NH&MRC Centre of Research Excellence in Nursing Interventions, Griffith University, Australia.

Centre of Health Practice Innovation, Griffith University, Australia.

Princess Alexandra Hospital, Woolloongabba, Australia.

School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Dundee, UK.

Department of Psychiatry, NHS Tayside, Perth, UK.

School of Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia.

Centre of National Research on Disability and Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Queensland, Australia.

Social Dimensions of Health Institute, University of Dundee, UK.

External sources

No sources of support supplied

Declarations of interest

Amanda J Ullman: none known

Leanne M Aitken: none known

Janice Rattray: none known

Justin Kenardy: none known

Robyne Le Brocque: none known

Stephen MacGillivray: none known

Alastair M Hull: none known

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Jones 2010 {published and unpublished data}

- Jones C, Backman C, Capuzzo M, Egerod I, Flaatten H, Granja C, et al and the RACHEL group. Intensive care diaries reduce new onset post traumatic stress disorder following critical illness: a randomised, controlled trial. Critical Care 2010;14(5):R168. [PUBMED: 20843344] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jones 2012 {published and unpublished data}

- Jones C, Backman C, Griffiths RD. Intensive care diaries and relatives' symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after critical illness: a pilot study. American Journal of Critical Care 2012;21(3):172‐6. [PUBMED: 22549573] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Knowles 2009 {published and unpublished data}

- Knowles R, Tarrier N. Evaluation of the effect of prospective patient diaries on emotional well‐being in intensive care unit survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Critical Care Medicine 2009;37(1):184‐91. [PUBMED: 19050634] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

AACN 2012 {published data only}

- Unknown. ICU diaries may reduce PTSD effect for families, patients. AACN Bold Voices 2012;4(10):15. [ISSN: 1948‐7088] [Google Scholar]

Backman 2001 {published data only}

- Backman C, Walther S. Use of a personal diary written on the ICU during critical illness. Intensive Care Medicine 2001;27(2):426‐9. [PUBMED: 11396288] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Backman 2010 {published data only}

- Backman C, Orwelius L, Sjoberg F, Fredrikson M, Walther S. Long‐term effect of the ICU‐diary concept on quality of life after critical illness. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2010;54(6):736‐43. [PUBMED: 20236095] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bagger 2006 {published data only}

- Bagger C. Diary for critically ill patients. Svgelplejersken 2006;25‐26:62‐5. [ISSN: 0106‐8350] [Google Scholar]

Garrouste‐Orgeas 2012 {published data only}

- Garrouste‐Orgeas M, Coquet I, Périer A, Timsit JF, Pochard F, Lancrin F, et al. Impact of an intensive care unit diary on psychological distress in patients and relatives. Critical Care Medicine 2012;40(7):2033‐40. [PUBMED: 22584757] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hale 2010 {published data only}

- Hale M, Parfitt L, Rich T. How diaries can improve the experience of intensive care patients. Nursing Management ‐ UK 2010;17(8):14‐8. [PUBMED: 21229866] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hayes 2008 {published data only}