Abstract

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is an overwhelming systemic inflammatory process associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Pharmacotherapies that moderate inflammation in ARDS are lacking. Several trials have evaluated the effects of pharmaconutrients, given as part of a feeding formula or as a nutritional supplement, on clinical outcomes in critical illness and ARDS.

Objectives

To systematically review and critically appraise available evidence on the effects of immunonutrition compared to standard non‐immunonutrition formula feeding on mechanically ventilated adults (aged 18 years or older) with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Search methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, conference proceedings, and trial registries for appropriate studies up to 25 April 2018. We checked the references from published studies and reviews on this topic for potentially eligible studies.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized controlled trials comparing immunonutrition versus a control or placebo nutritional formula in adults (aged 18 years or older) with ARDS, as defined by the Berlin definition of ARDS or, for older studies, by the American‐European Consensus Criteria for both ARDS and acute lung injury.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of studies and extracted data from the included trials. We sought additional information from study authors. We performed statistical analysis according to Cochrane methodological standards. Our primary outcome was all‐cause mortality. Secondary outcomes included intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, ventilator days, indices of oxygenation, cardiac adverse events, gastrointestinal adverse events, and total number of adverse events. We used GRADE to assess the quality of evidence for each outcome.

Main results

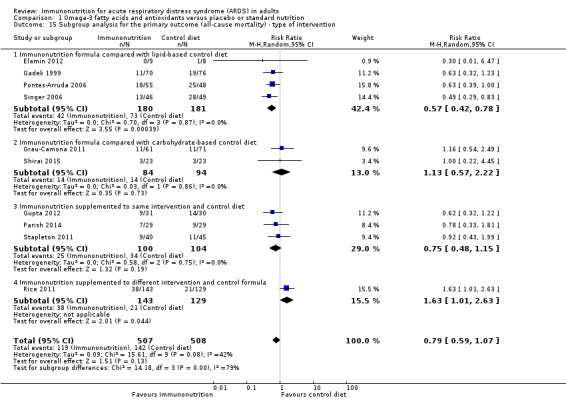

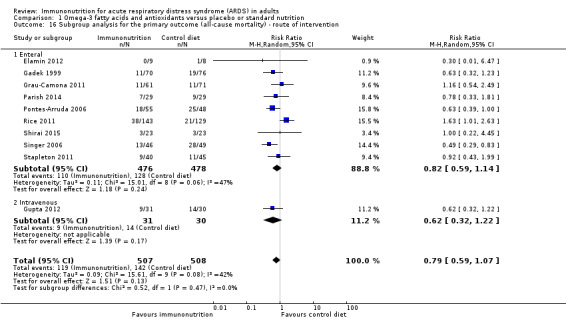

We identified 10 randomized controlled trials with 1015 participants. All studies compared an enteral formula or additional supplemental omega‐3 fatty acids (i.e. eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)), gamma‐linolenic acid (GLA), and antioxidants. We assessed some of the included studies as having high risk of bias due to methodological shortcomings. Studies were heterogenous in nature and varied in several ways, including type and duration of interventions given, calorific targets, and reported outcomes. All studies reported mortality. For the primary outcome, study authors reported no differences in all‐cause mortality (longest period reported) with the use of an immunonutrition enteral formula or additional supplements of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants (risk ratio (RR) 0.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 1.07; participants = 1015; studies = 10; low‐quality evidence).

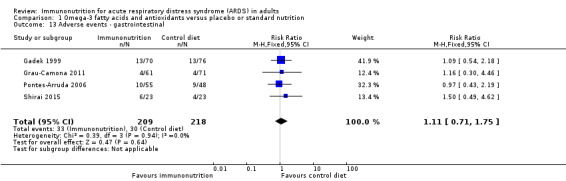

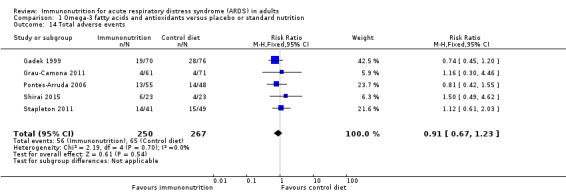

For secondary outcomes, we are uncertain whether immunonutrition with omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants reduces ICU length of stay (mean difference (MD) ‐3.09 days. 95% CI ‐5.19 to ‐0.99; participants = 639; studies = 8; very low‐quality evidence) and ventilator days (MD ‐2.24 days, 95% CI ‐3.77 to ‐0.71; participants = 581; studies = 7; very low‐quality evidence). We are also uncertain whether omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants improve oxygenation, defined as ratio of partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO₂) to fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO₂), at day 4 (MD 39 mmHg, 95% CI 10.75 to 67.02; participants = 676; studies = 8), or whether they increase adverse events such as cardiac events (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.09 to 8.46; participants = 339; studies = 3; very low‐quality evidence), gastrointestinal events (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.75; participants = 427; studies = 4; very low‐quality evidence), or total adverse events (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.23; participants = 517; studies = 5; very low‐quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

This meta‐analysis of 10 studies of varying quality examined effects of omega‐3 fatty acids and/or antioxidants in adults with ARDS. This intervention may produce little or no difference in all‐cause mortality between groups. We are uncertain whether immunonutrition with omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants improves the duration of ventilator days and ICU length of stay or oxygenation at day 4 due to the very low quality of evidence. Adverse events associated with immunonutrition are also uncertain, as confidence intervals include the potential for increased cardiac, gastrointestinal, and total adverse events.

Plain language summary

Immunonutrition for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in adults

Background

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is a life‐threatening condition wherein the lungs are inflamed (irritated) and damaged. In this state, the lungs cannot deliver into the blood enough oxygen for the body’s vital organs. It is usually seen in patients who are already seriously ill. Currently, no specific effective therapeutic options are available for this condition. Alternatively, change in dietary intake has been deployed. Modification of the nutrition given to adults with ARDS, to include components of food that have an anti‐inflammatory effect, could reduce lung inflammation and improve outcomes in adults with this condition. Omega‐3 fatty acids (known as DHA and EPA) are found in fish oils and can have an anti‐inflammatory effect. Reviewers examined reported outcomes and effects of changes in nutrition among studies involving adults with ARDS.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current up to April 2018. We included in this review 10 studies with 1015 adult participants. These studies were conducted in intensive care units and compared standard nutrition (the usual nutrition given to patients with ARDS) versus nutrition supplemented with omega‐3 fatty acids or placebo (a substance with no active effect), and compared either with or without antioxidants. Antioxidants are molecules that can inhibit or slow down oxidation ‐ a reaction that can cause inflammation and damage cells.

Key results

It is unclear whether use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants as part of nutritional intake in patients with ARDS improves long‐term survival. It is uncertain whether omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants reduce length of ICU stay and the number of days spent on a ventilator, or if they improve oxygenation. It is also unclear if this type of nutrition causes increased harm.

Quality of evidence

Findings of this review are limited by lack of standardization among the included studies in terms of methods, types of nutritional supplements given, and reporting of outcome measures. We rated the quality of evidence as low to very low.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants compared with placebo or standard nutrition for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

| Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants compared with placebo or standard nutrition for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) | |||||

|

Patient or population: adults (aged 18 years or older), mechanically ventilated participants with ARDS as defined by the Berlin definition of ARDS or, for older studies, the American‐European Consensus Criteria for both ARDS and acute lung injury Settings: intensive care units in USA, Brazil, India, Iran, Israel, Japan, and Spain Intervention: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants Comparison: placebo or standard nutrition | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | |

| Risk with placebo or standard nutrition | Risk with omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants | ||||

| All‐cause mortality (longest period reported) |

280 per 1000 | 221 per 1000 (165 to 299) | RR 0.79 (0.59 to 1.07) |

1015 (10 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa,b |

| ICU LOS (days) |

Mean 18.09 days | MD 3.09 days lower (5.19 lower to 0.99 lower) |

‐ | 639 (8 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| Ventilator days (days) |

Mean 12.95 days | MD 2.24 days lower (3.77 days lower to 0.71 days lower) |

‐ | 581 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| Indices of oxygenation (measured as PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 4) |

Mean 180.10 mmHg | MD 39 mmHg higher (10.75 mmHg higher to 67.02 mmHg higher) |

‐ | 659 (7 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| Cardiac adverse events (study author reported anytime during study period) |

40 per 1000 | 35 per 1000 (4 to 342) | RR 0.87 (0.09 to 8.46) |

339 (3 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| Gastrointestinal adverse events (study author reported anytime during study period) |

138 per 1000 | 153 per 1000 (98 to 241) | RR 1.11 (0.71 to 1.75) |

427 (4 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| Total number of adverse events (study author reported anytime during study period) |

243 per 1000 | 222 per 1000 (163 to 299) |

RR 0.91 (0.67 to 1.23) |

517 (5 RCTs) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa,b,c |

| The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; CI: confidence interval; FiO₂: fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; LOS: length of stay; MD: mean difference; PaO₂: partial pressure of arterial oxygen; RCT: randomized controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

aRisk of bias downgraded (‐1) due to selection, performance, and attrition bias in the included studies.

bInconsistency downgraded (‐1) due to both clinical and methodological inconsistency in the included studies.

cIndirectness downgraded (‐1) due to indirect intervention and comparator in the included studies. In some included studies, control participants' nutritional formula may have increased the risk of harm.

Background

Description of the condition

Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is characterized by severe hypoxic respiratory failure with significant global inflammatory processes and multi‐organ dysfunction. In the lung, diffuse epithelial and endothelial injury leads to increased alveolar capillary permeability and florid pulmonary oedema. Clinically, patients present with acute severe hypoxaemia and poor lung compliance, often necessitating invasive mechanical ventilation (Dushianthan 2011). The reported incidence of ARDS varies between countries and ranges from 16 to 78 per 100,000 population (Walkey 2012). Several predisposing conditions and risk factors contribute to the development of ARDS. Shock, sepsis, pneumonia, aspiration, and pancreatitis are the clinical conditions commonly associated with increased likelihood of developing ARDS (Gajic 2011). Hospital mortality associated with ARDS varies between 27% and 45%, depending on the severity of the disease (Ranieri 2012). Survivors of ARDS have significant long‐term physical, cognitive, and psychological sequelae (Herridge 2011; Wang 2014).

Since the first description of ARDS in 1967 (Ashbaugh 1967), diagnostic definitions have evolved. The American‐European Consensus Criteria, published in 1994, provide the most frequently utilized definition among published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of patients with ARDS (Bernard 1994). According to these criteria, ARDS is recognized by bilateral pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph, with a ratio of partial pressure of oxygen (PaO₂)‐to‐fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO₂) of less than 200 mmHg, in the absence of raised left atrial hypertension. If less hypoxia is evident, defined as a PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio less than 300 mmHg, the syndrome is termed 'acute lung injury' (Bernard 1994). However, due to several limitations of this definition, new criteria proposed by an expert consensus panel in 2012 constitute the 'Berlin definition' of ARDS (Ranieri 2012). This definition eliminated the existing term 'acute lung injury' and identified patients as having ARDS when they fulfilled all of the following criteria.

Onset within seven days of a known clinical insult.

Bilateral opacities on chest imaging.

PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio less than 300 mmHg.

Hypoxaemia not fully explained by cardiac failure or fluid overload.

ARDS has been further subcategorized into mild (PaO₂/FiO₂ 201 to 300 mmHg), moderate (PaO₂/FiO₂ 100 to 200 mmHg), and severe (PaO₂/FiO₂ < 100 mmHg), according to the severity of hypoxaemia (Ranieri 2012).

At present, no effective pharmacotherapies are known to moderate the disease process of ARDS. Evidence suggests survival benefit from 'protective' lung ventilation strategies designed to minimize further lung injury during mechanical ventilation.

Description of the intervention

'Immunonutrition' refers to modulation of the immune system provided by specific interventions that modify dietary nutrients (Calder 2003). It has long been recognized that supplementary immunonutrients may alter the course of critical illness following sepsis, trauma, or surgery (Beale 1999). Several specialized enteral and parenteral formulas with immunonutrients are currently available on the market. These primarily consist of a combination of antioxidant vitamins (vitamin C, vitamin E, beta‐carotene), trace elements (selenium, zinc), essential amino acids (glutamine, arginine) or essential fatty acids, such as omega‐3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid), and gamma‐linolenic acid (GLA) (Mizock 2010).

How the intervention might work

Acute respiratory distress syndrome is characterized by overt recruitment of neutrophils, significant release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and activation of pro‐coagulant cascades and prostaglandin pathways with increased oxidative stress, causing damage to both lipids and proteins (Matthay 2011). In patients with ARDS, significant imbalance in the antioxidant system with a relative increase in oxidative stress leads to increased alveolar injury (Lang 2002; Metnitz 1999; Schmidt 2004). Among critically ill patients in general, supplementation of antioxidants is associated with a favourable outcome (Heyland 2005). Macronutrients such as glutamine and arginine also have immunomodulatory properties and have been used in several clinical trials of critically ill and surgical patients (Andrews 2011; Heyland 2001; Heyland 2013; Novak 2002). Glutamine improves gut barrier function and can be an energy source for lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages (Newsholme 1985; Soares 2014), whereas arginine deficiency, which is commonly encountered following critical illness, may impair T‐cell function (Popovic 2007). Omega‐3 fatty acids are essential lipids, enriched in fish oil and consisting of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), alpha‐linolenic acid (ALA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Therapeutic supplementation of these nutrients, which have immunomodulatory properties, has been shown to moderate the inflammatory response through suppression of pro‐inflammatory eicosanoid biosynthesis (Calder 2007), attenuation of pulmonary neutrophil accumulation (Mancuso 1997a), reduction in lung permeability (Mancuso 1997b), and attenuation of cardiopulmonary dysfunction in animal models of lung injury (Murray 1995). Furthermore, in endotoxaemic rat models, EPA has been shown to reduce pulmonary oedema (Sane 2000).

Why it is important to do this review

Various types of immunonutrition have the potential to influence clinical outcomes in critically ill patients (Mizock 2010). Several RCTs have investigated enteral supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants, which, when combined in a meta‐analysis, showed a significant reduction in mortality with improvement in oxygenation for patients with acute lung injury (ALI) and ARDS (Pontes‐Arruda 2008). However, recent studies have presented conflicting results, suggesting lack of benefit and possibly even harm caused by this intervention (Rice 2011; Stapleton 2011). Among critically ill patients, enteral supplementation of glutamine conferred no clinical benefit (van Zanten 2015), and a large RCT showed a trend towards increased mortality associated with glutamine therapy (Heyland 2013). This lack of demonstrable clinical benefit in recent studies conflicts with the established literature and may be due to heterogeneity of diseases within the population of critical care patients, or variations in the type, route, and dose of immunonutrients administered. Uncertainty arising from these conflicting results remains. This review aims to provide a comprehensive evaluation of the effects of immunonutrients for patients with ARDS.

Objectives

To systematically review and critically appraise available evidence on the effects of immunonutrition compared to standard non‐immunonutrition formula feeding on mechanically ventilated adults (aged 18 years or older) with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials (qRCTs), with or without blinding. We did not apply language restrictions. We excluded non‐randomized controlled trials and observational studies due to increased risk of bias.

Types of participants

We included all studies involving mechanically ventilated adult participants (aged 18 years or older) with ARDS as defined by the Berlin definition of ARDS (Ranieri 2012), or, for older studies, as defined by American‐European Consensus Criteria for both ARDS and ALI (Bernard 1994). We restricted this review to trials conducted in critically ill adults, as pathophysiology and management strategies differ in paediatric and neonatal populations compared with adults.

Types of interventions

Eligible trials included intervention groups consisting of participants given enteral or parenteral immunonutrients, additionally supplemented with or as part of a nutritional formula. In comparison, control groups comprised participants who received placebo or standard nutrition with a non‐immunonutrient formula feed. The immunonutrients could be amino acids (glutamine, arginine), antioxidants, or essential fatty acids, such as omega‐3 fatty acids supplemented for any duration and at any dose.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality (longest period reported)

Secondary outcomes

28‐day mortality

Intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay (LOS) and ICU‐free days at day 28 (days)

Ventilator days and ventilator‐free days at day 28 (days)

Hospital LOS (days)

Indices of oxygenation (measured as PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio (mmHg) at days 4 and 7)

Other organ failure (measured as change in organ failure scores: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score, Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score (MODS); number of patients with new organ failure developed during the study period)

Nosocomial infection (additional infection developed during hospital stay and reported anytime during the study period)

Adverse events (author‐defined cardiac events, gastrointestinal events, and total adverse events reported anytime during the study period)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified RCTs through literature searching with systematic and sensitive search strategies, as outlined in Chapter 6.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We did not apply restrictions to language or publication status. We searched the following databases for relevant trials.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2018, Issue 4, April) in the Cochrane Library.

MEDLINE (OVID SP; 1966 to April week 3 2018).

Embase (OVID SP; 1988 to April week 3 2018).

We developed a subject‐specific search strategy for MEDLINE and used that as the basis for the search strategies used in other databases listed. When appropriate, we expanded the search strategy with search terms for identifying RCTs. All search strategies can be found in Appendix 1,Appendix 2,Appendix 3, and Appendix 4.

We scanned the following trial registries for ongoing and unpublished trials (April 2018).

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Resgistry Platform (WHO ICTRP).

ClinicalTrials.gov.

Searching other resources

We scanned the reference lists and citations of included trials and any relevant systematic reviews identified for further references to additional trials. We manually searched for relevant citations from published studies, previous systematic reviews, and conference proceedings from major intensive care and nutrition societies (i.e. Intensive Care Society, UK; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine; Society of Critical Care Medicine; American Thoracic Society; Canadian Critical Care Society; American Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; European Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition).

When necessary, we contacted trial authors to request additional information.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AD and RC) independently screened appropriate studies for study characteristics and outcomes. We resolved disagreements by further discussion and with involvement of a third review author (MG).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AD and RC/VL) independently performed data extraction using a data extraction form that was piloted before it was applied in this study (Appendix 5). We recorded study characteristics including patient population (ARDS), intervention details (type, dose, duration), study methods (blinding, allocation, etc.), and outcome measures of interest. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by consultation with the third member of the review author team (MG).

If observations were not reported as means and standard deviations (SDs), we contacted trial authors for additional information. In the absence of any further information, we used the statistical equation from Hozo 2005 to convert the median (range/interquartile range (IQR)) to the mean (SD). We estimated the SD as IQR/1.35, standard error of the mean (SEM) × √(n), 95% confidence interval (CI)/1.96. We estimated standard deviations from P values according to information provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AD and RC/VL) assessed the risk of bias of included studies according to criteria presented in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved disagreements by discussion or by consultation with the third review author (MG). We assigned the included studies to low risk of bias (when all domains were satisfied), high risk of bias (if one or more domains were inadequate), or unclear risk of bias, according to the criteria provided in the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool. We used the following six domains to assess risk of bias in the included studies.

Selection bias (random sequence generation and allocation concealment).

Performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel).

Detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment).

Attrition bias (incomplete outcome data).

Reporting bias (selective reporting).

Any other potential biases that might be present.

Measures of treatment effect

We based the outcome analysis on intention‐to‐treat (ITT). We calculated weighted treatment effects using Review Manager 5.3 (Review Manager 2014). We expressed dichotomous outcomes, such as mortality, as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and continuous variables as mean differences (MDs) with standard deviations (SDs).

Unit of analysis issues

To prevent unit of analysis issues, when combining groups for continuous outcomes, we used the formula suggested by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Dealing with missing data

When we encountered missing data, we contacted the authors of included studies to request further information. In the absence of an appropriate response, we analysed the data using the best available information. We performed ITT analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed the clinical heterogeneity of studies in relation to study population, interventions, and outcome measures. We also assessed inconsistencies and variability in outcomes among studies using the I² statistic. Variation greater than 40% among outcomes may not be explained by sampling variation. We assumed substantial statistical heterogeneity when the I² statistic exceeded 40% (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We included 10 studies; therefore, we used graphical evidence of reporting biases via contour‐enhanced funnel plots with a subsequent Harbord or Egger's test (Egger 1997; Harbord 2006).

Data synthesis

We pooled data according to the type of immunomodulatory agent. Most studies used a combination of omega‐3 fatty acid, GLA, and antioxidant solutions; therefore, we pooled the results of these studies. We conducted statistical data analysis using Review Manager 5.3 (Review Manager 2014), in accordance with recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We based our analysis on the ITT principle and utilized fixed‐effect and random‐effects models, depending on statistical heterogeneity. We used a fixed‐effect model unless we noted significant statistical heterogeneity, defined by an I² value > 40%.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analyses for the primary outcome according to the following.

Type of intervention.

Route of intervention (parenteral/enteral).

Mode of intervention (continuous/bolus).

Intervention duration (days).

Sensitivity analysis

We performed sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome while excluding studies with high risk of bias. Continuous data for the secondary outcomes were skewed. We conducted sensitivity analysis for these secondary outcomes by log transformation. Given that we obtained no raw log‐transformed data from study authors, we transformed the mean and the standard deviation in accordance with recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Analyses for two of the secondary outcomes ‐ ICU‐free days and ventilator‐free days at day 28 ‐ were sensitive to statistical methods; we also performed sensitivity analyses for these outcomes using both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models (Table 2).

1. Sensitivity analysis for the outcomes ICU‐free days and ventilator‐free days at day 28 according to statistical methods.

| Outcome | Statistical analysis | MD (95% CI), P value |

| ICU‐free days at day 28 | Mean difference (IV, random‐effects, 95% CI) | 3.44 (‐1.17 to 8.06), P = 0.14 |

| ICU‐free days at day 28 | Mean difference (IV, fixed‐effect, 95% CI) | 1.95 (0.42 to 3.48), P = 0.01 |

| Ventilator‐free days at day 28 | Mean difference (IV, random‐effects, 95% CI) | 2.15 (‐0.91 to 5.22), P = 0.17 |

| Ventilator‐free days at day 28 | Mean difference (IV, fixed‐effect, 95% CI) | 1.00 (0.06 to 1.94), P = 0.04 |

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE

We used the principles of the GRADE system to assess the quality of the body of evidence associated with specific outcomes (Guyatt 2008): all‐cause mortality, ICU length of stay, ventilator days, PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 4, and adverse events. We constructed a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADE software (GRADEpro GDT). Through the GRADE approach, we appraised the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. Assessment of the quality of a body of evidence considers within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity of data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

See characteristics of Included studies.

Results of the search

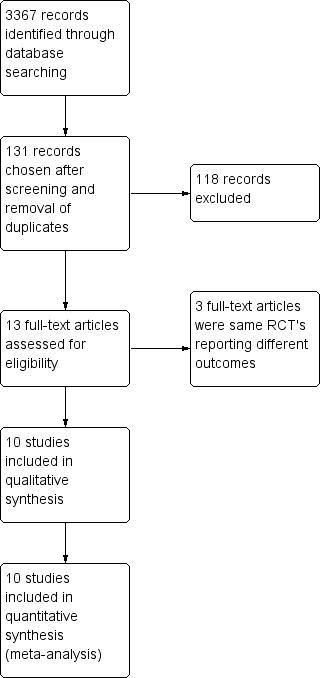

The combined search yielded 3367 studies for possible inclusion. We chose 131 abstracts for further evaluation after screening and removal of duplicates. We retrieved a total of 13 publications reporting 10 RCTs (Figure 1). We included the publication that reported the main clinical outcomes, and we omitted duplicate reports.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Characteristics of patient population

Nine of the 10 included studies used the American‐European Consensus Criteria (AECC) for identification of ARDS or ALI (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). The remaining study enrolled ventilated patients with septic shock and did not explicitly define this population as ARDS/ALI or not (Grau‐Camona 2011). However, baseline characteristics suggest that the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio was < 300 mmHg for all participants, and of those, 71% had ARDS at the time of recruitment. It is possible that not all of these participants may have satisfied ARDS/ALI criteria. For included studies, the mean PaO₂/FiO₂ was 157 mmHg for intervention groups and 167 mmHg for control groups, suggesting moderate severity according to the current Berlin definition of ARDS (Ranieri 2012). Three studies were conducted specifically in participants with sepsis‐induced ARDS (Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015).

Characteristics of intervention provided

We did not identify any other intervention apart from omega‐3 fatty acids (EPA and DHA) and GLA with or without antioxidant‐based enteral formula or supplementation. Several clinical trials investigated the use of glutamine supplementation for critical illness, but none specifically focused on ARDS (van Zanten 2015).

Among the 10 included studies, six studies used a similar enteral preparation (Oxepa; Abbott Nutrition/Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH, USA) continuously supplemented with EPA, DHA, GLA, and antioxidants (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006). Four of these six studies used an isocaloric high‐fat formulation (Pulmocare; Abborr Nutrition/Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, OH, USA) for control groups (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006). The remaining two studies used a carbohydrate‐based control formulation (Ensure Plus or Ensure Liquid; Abbott Laboratories, East Windsor, NJ, USA) (Grau‐Camona 2011; Shirai 2015).

Three studies used additional enteral supplementation of fish oil (Stapleton 2011), omega‐3 gels (Parish 2014), or intravenous formulation with 10% fish oil (Gupta 2012), and control groups received the same enteral feeding formulation as intervention groups. One study gave boluses of a high‐fat formulation enriched in EPA, DHA, GLA, and antioxidants and compared this with isocaloric‐isovolaemic carbohydrate‐rich control nutrition (Rice 2011).

Five studies defined a target enteral nutrition delivery rate of 50% to 75% of basal/resting energy expenditure (BEE/REE) for the first 24 hours with variable increments to achieve 70% to 100% of BEE/REE (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006). The duration of intervention was 7 or fewer days (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999), 14 days (Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011), 21 days (Rice 2011), or 28 days (Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006).

Outcome measures reported

All 10 included studies reported mortality. One study reported this for the duration of the study period (Gadek 1999), six studies at 28 days (Elamin 2012; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006), and one study at hospital discharge or at day 60 (Rice 2011). One study reported in‐hospital mortality and mortality at 60 days (Stapleton 2011), and another at only 60 days (Shirai 2015).

Eight studies reported ICU LOS (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011), and five reported ICU‐free days at day 28 (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Three studies reported hospital LOS (Gadek 1999; Gupta 2012; Stapleton 2011).

Seven studies reported ventilator days (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011), and six reported this outcome as ventilator‐free days at day 28 (Gadek 1999; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011).

All included studies reported changes in oxygenation index (PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio) for various time points (baseline, day 1, day 2, day 3, day 4, day 5, day 7, day 8, day 14, and day 21). Six studies reported day 4 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratios (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Gupta 2012; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011), and seven studies reported day 7 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratios (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015). We used these time points for the meta‐analysis.

Researchers reported new organ failure in several different ways: change in or worst MODS (Elamin 2012; Stapleton 2011), change in SOFA score (Grau‐Camona 2011), number of participants with new organ failure (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006), and organ failure‐free days (Rice 2011).

Three studies reported nosocomial infection (Grau‐Camona 2011; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015).

Six studies reported adverse events (Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Two studies reported system‐based adverse events with total numbers of events (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006). One study reported individual and total numbers of adverse events (Stapleton 2011).

Excluded studies

We excluded no randomized controlled studies.

Awaiting classification

No studies are currently awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We identified no ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

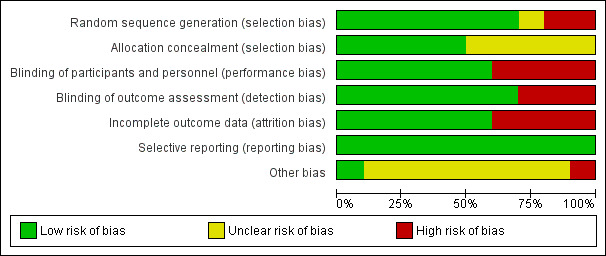

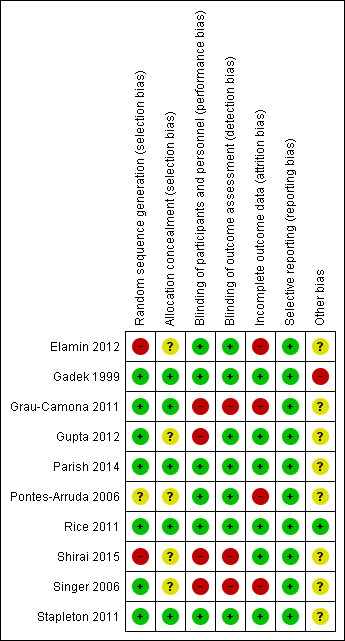

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

All included studies reported randomization. EIght studies reported the method of random sequence generation used (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Rice 2011; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). One study described alternating allocation (Elamin 2012), and two other studies did not describe the method of randomization used (Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015). We categorized these studies as having high risk of selection bias. Five studies did not specifically report on allocation concealment, and we categorized these as having unclear risk of bias (Elamin 2012; Gupta 2012; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006).

Blinding

Six studies were double‐blinded (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Stapleton 2011). One study was not blinded (Singer 2006). Three other studies reported single or investigator blinding (Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Shirai 2015). We assigned these studies as having high risk of performance or detection bias (Gupta 2012; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006).

Incomplete outcome data

We detected attrition bias in five studies that excluded participants from their ITT analysis for various reasons, including diarrhoea, steroid use, withdrawal of care, or treating physician preference, and as a consequence of protocol violations (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006).

Selective reporting

We judged that all 10 included studies had low risk of reporting bias, and they reported all prespecified outcomes.

Other potential sources of bias

Authors of four studies reported that they were industry supported (Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006). We rated these studies as having unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison. Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition

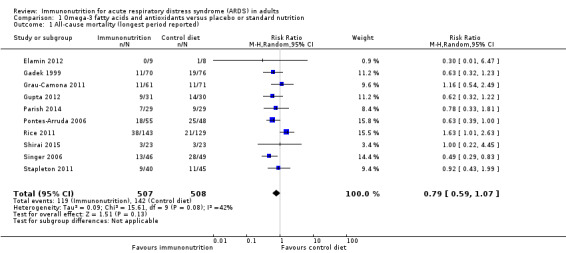

Primary outcome: all‐cause mortality (longest period reported)

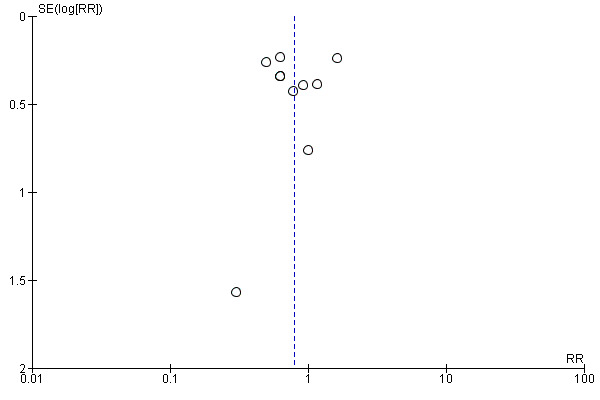

All studies reported mortality. The range of reported mortality varied between studies: six studies reported this outcome at day 28 (Elamin 2012; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006), three studies at day 60 (Parish 2014; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015), and one for the study duration. We included all 10 studies with 1015 participants in this analysis (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). No evidence showed the use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants for reducing mortality at the longest period reported (risk ratio (RR) 0.79, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.59 to 1.07; I² = 42%; participants = 1015; Analysis 1.1). The pooled control group mortality rate was 28%, and the pooled intervention group mortality rate was 23.5% for the longest period reported. Overall mortality varied between studies and ranged from 6% to 43%. A funnel plot of the primary outcome prepared to test the effect of publication bias showed no evidence of data asymmetry (Egger's regression test, with P = 0.81) (Figure 4). We downgraded the quality of evidence by two levels due to inconsistency from clinical and methodological heterogeneity and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality (longest period reported).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, outcome: 1.1 All‐cause mortality (longest period reported).

Secondary outcomes

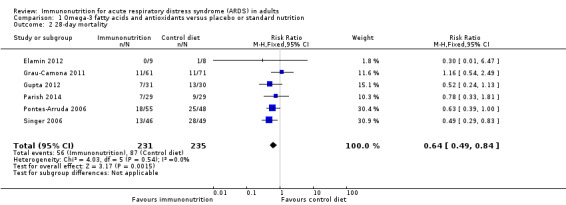

Mortality at 28 days

Six studies with 466 participants reported 28‐day mortality (Elamin 2012; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006). We noted uncertain evidence for use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants in terms of mortality at 28 days (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.84; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.2). This analysis was limited by the small number of participants, which accounted for less than 50% of the total participants included. We downgraded the quality of evidence by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for both intervention and comparator.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 2 28‐day mortality.

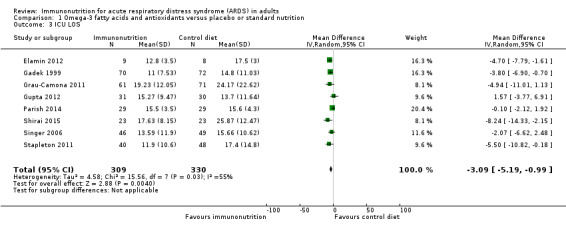

Intensive care unit length of stay (ICU LOS) and ICU‐free days at day 28

Eight studies with 639 participants reported ICU LOS (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). Two studies reported this outcome as mean ± standard error (Gadek 1999; Shirai 2015). Two studies published separate data for participants who survived and those who did not survive (Gupta 2012; Singer 2006). We combined these groups according to recommendations provided in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We obtained further information from the authors of three studies (Elamin 2012; Grau‐Camona 2011; Stapleton 2011). We found uncertain evidence suggesting that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may reduce ICU LOS (mean difference (MD) ‐3.09 days, 95% CI ‐5.19 to ‐0.99; I² = 55%; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 3 ICU LOS.

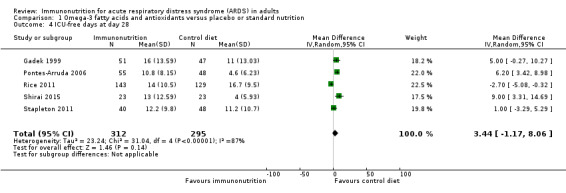

Five studies with 607 participants reported ICU‐free days at day 28 (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). For two studies, we estimated the standard deviation from the P value or the IQR (Gadek 1999; Shirai 2015), respectively, as we were not able to obtain further information from study authors. We found uncertain evidence that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may increase ICU‐free days at day 28 (MD 3.44, 95% CI ‐1.17 to 8.06; I² = 87%; Analysis 1.4). We performed random‐effects model analysis due to significant statistical heterogeneity, with I² = 87%.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 4 ICU‐free days at day 28.

We downgraded the quality of evidence for both of these outcomes by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

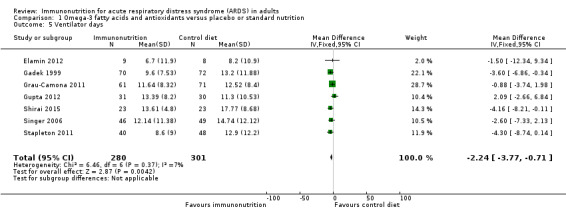

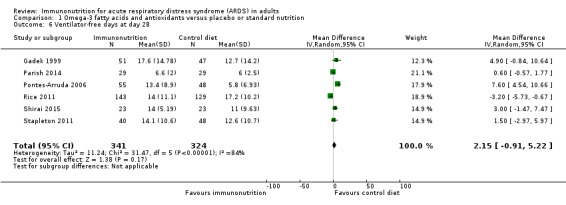

Ventilator days and ventilator‐free days at day 28

Seven studies with 581 participants reported duration of mechanical ventilation (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may reduce the duration of mechanical ventilation (MD ‐2.24, 95% CI ‐3.77 to ‐0.71; I² = 7%; Analysis 1.5). Six studies with 665 participants reported the duration of mechanical ventilation as ventilation‐free days at day 28 (Gadek 1999; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may increase ventilation‐free days (MD 2.15, 95% CI ‐0.91 to 5.22; I² = 84%; Analysis 1.6). We performed random‐effects model analysis due to significant statistical heterogeneity, with I² = 84%.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 5 Ventilator days.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 6 Ventilator‐free days at day 28.

We downgraded the quality of evidence for both of these outcomes by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

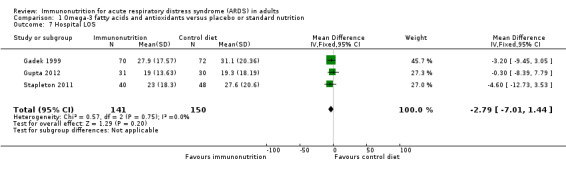

Hospital length of stay (days)

Three studies with 291 participants reported hospital length of stay (Gadek 1999; Gupta 2012; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may reduce the duration of hospital LOS (MD ‐2.79, 95% CI ‐7.01 to 1.44; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.7). We downgraded the quality of evidence by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 7 Hospital LOS.

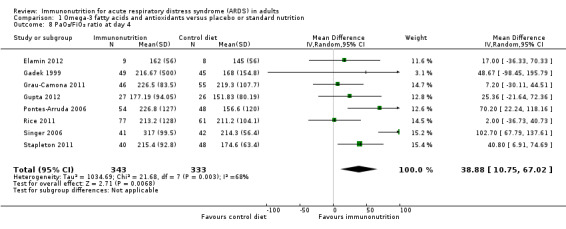

Indices of oxygenation (measured as PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio (mmHg) at day 4 and day 7)

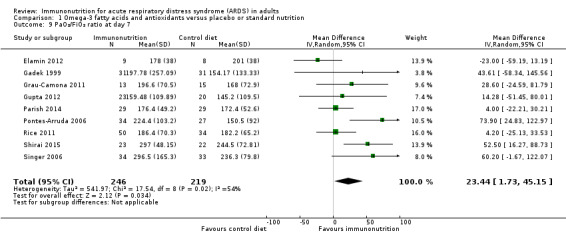

Researchers commonly reported oxygenation as the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio (mmHg). Nine studies reported this outcome at day 4 (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). Two of these studies presented their PaO₂/FiO₂ data in pictorial format (Rice 2011; Shirai 2015). We were able to obtain additional information from one study (Rice 2011). We estimated the SD from P values for two studies (Elamin 2012; Pontes‐Arruda 2006). However, we were not able to include one study due to lack of further information (Shirai 2015). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may improve oxygenation defined as the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 4 (eight studies with 676 participants) (MD 39 mmHg, 95% Cl 11 to 67 mmHg; I² = 68%; Analysis 1.8). Nine studies with 465 participants reported the PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 7 (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may improve oxygenation defined as PaO₂/FiO₂ ratios at day 7 (MD 23 mmHg, 95% Cl 2 to 45 mmHg; I² = 54%; Analysis 1.9). We downgraded the quality of evidence for both of these outcomes by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 8 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 4.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 9 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 7.

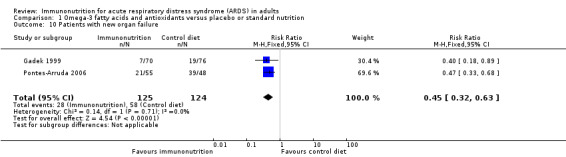

Other organ failure (measured as change in organ failure scores: SOFA score, MODS, and number of participants with new organ failure)

Seven studies reported new organ failure in several different ways (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Only two studies (249 participants) reported the number of participants with new organ failure (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006), and we pooled results of these studies. Use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants for prevention of new organ failure is uncertain (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.63; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.10). We downgraded the quality of evidence by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator. We were not able to pool other studies due to variation in reporting this outcome as MODS (Elamin 2012), worse MODS (Stapleton 2011), SOFA score (Grau‐Camona 2011), organ failure‐free days (Rice 2011), and changes in SOFA scoring (Shirai 2015).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 10 Patients with new organ failure.

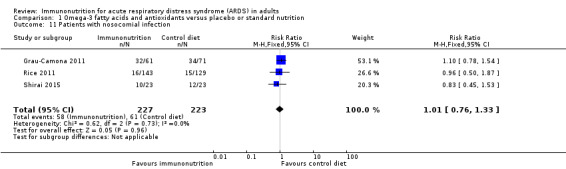

Nosocomial infection (additional infection developed during hospital stay)

Three studies with 450 participants reported the number of participants with new nosocomial infection (Grau‐Camona 2011; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015). Uncertain evidence suggests that omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may reduce new nosocomial infection between groups (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.33; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.11). We downgraded the quality of evidence by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 11 Patients with nosocomial infection.

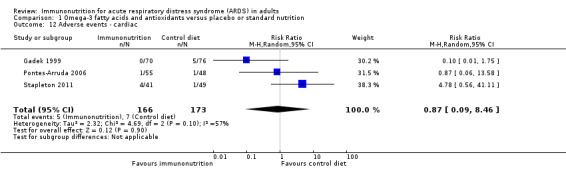

Adverse events (cardiac events, gastrointestinal events, and total adverse events)

Six studies reported adverse events (Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Two studies reported these as system based (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006), and Stapleton 2011 reported all adverse events. Three studies with 339 participants reported cardiac adverse events (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may increase cardiac events (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.09 to 8.46; I² = 57%; Analysis 1.12). Five studies reported gastrointestinal adverse events (Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015). One study reported these as a percentage of ventilated days, and we did not include this value in the meta‐analysis (Rice 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may increase gastrointestinal events (four studies with 427 participants) (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.75; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.13). Five studies with 517 participants reported total numbers of adverse events (Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015; Stapleton 2011). Uncertain evidence suggests that use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants may increase total numbers of adverse events between groups (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.67 to 1.23; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.14). We downgraded the quality of evidence for all these outcomes by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 12 Adverse events ‐ cardiac.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 13 Adverse events ‐ gastrointestinal.

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 14 Total adverse events.

Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome: all‐cause mortality (longest period reported)

Type of intervention

The type of intervention varied between studies, as explained previously in the Description of studies section. For the primary outcome, we performed a subgroup analysis for types of intervention given. Four studies with 361 participants added an enteral formula enriched in EPA, GLA, DHA, and antioxidants to a lipid‐rich omega‐6 fatty acid‐based control diet (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006). We are uncertain of any mortality benefit when investigators compared an omega‐3 fatty acid and/or antioxidant group versus a lipid‐rich control group (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.78; I² = 0%; Analysis 1.15), or versus a carbohydrate‐rich control group (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.57 to 2.22; I² = 0%; participants = 178; studies = 2; Analysis 1.15) (Grau‐Camona 2011; Shirai 2015), or versus additional supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids (RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.15; I² = 0%; participants = 204; studies = 3; Analysis 1.15) (Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Stapleton 2011).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 15 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ type of intervention.

Route of administration (parenteral/enteral) of intervention

Only one study gave intravenous omega‐3 fatty acid supplementation (Gupta 2012). All remaining studies gave enteral supplementation. We are uncertain of any mortality benefit derived by route of administration of the intervention (nine studies with 954 participants) (RR 0.82, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.14; I² = 47%; Analysis 1.16) (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Parish 2014; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Rice 2011; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 16 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ route of intervention.

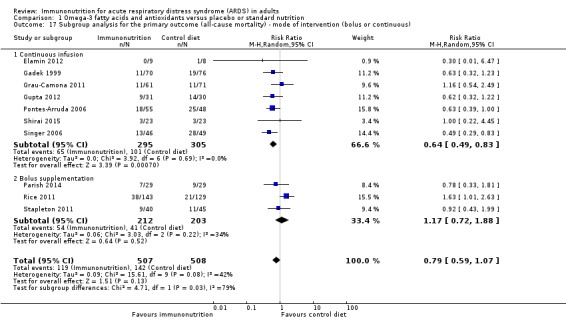

Mode (continuous/bolus) of intervention

Six studies gave continuous enteral nutrition (Elamin 2012; Gadek 1999; Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006), and one study used intravenous infusion (Gupta 2012). The remaining three studies used bolus supplementation (Parish 2014; Rice 2011; Stapleton 2011). We are uncertain of any mortality benefit derived by continuous infusion, received enterally or parenterally (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.83; I² = 0%; participants = 600; studies = 7; Analysis 1.17). We are uncertain of any mortality benefit derived by bolus supplementation (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.88; I² = 34%; participants = 415; studies = 3; Analysis 1.17).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 17 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ mode of intervention (bolus or continuous).

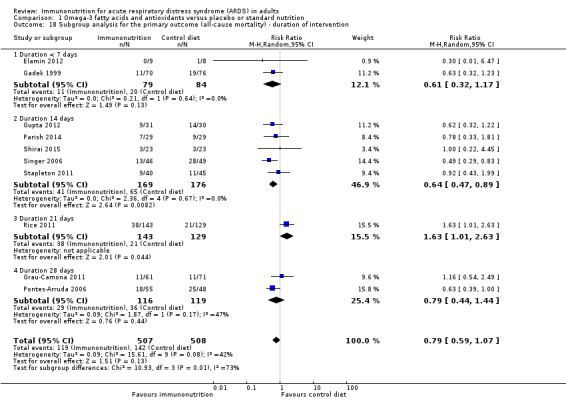

Duration of intervention

Duration of intervention varied among studies. One study reported the intervention period as 4 or fewer days (Gadek 1999). Others reported 7 days (Elamin 2012), 14 days (Gupta 2012; Parish 2014; Shirai 2015; Singer 2006; Stapleton 2011), 21 days (Rice 2011), and 28 days (Grau‐Camona 2011; Pontes‐Arruda 2006). We are uncertain of any mortality benefit associated with duration of intervention for fewer than 7 days (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.17; I² = 0%; participants = 163; studies = 2; Analysis 1.18), for 14 days (RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.89; I² = 0%; participants = 345; studies = 5; Analysis 1.18), or for 28 days (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.44; I² = 44%; participants = 235; studies = 2; Analysis 1.18).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 18 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ duration of intervention.

We downgraded the quality of evidence for all subgroup analyses by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

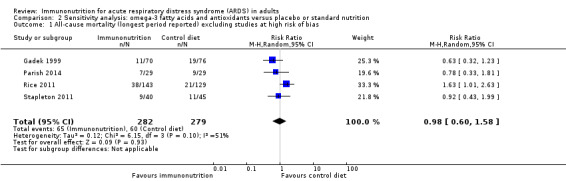

Sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome excluding studies with high risk of bias

We conducted sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome while excluding studies with high risk of bias. We included four studies in the analysis (Gadek 1999; Parish 2014; Rice 2011; Stapleton 2011). We found no evidence for the use of omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants in reducing mortality at the longest period reported (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.58; I² = 51%; participants = 561; Analysis 2.1). We graded quality of evidence as low and downgraded the evidence by two levels due to inconsistency from clinical and methodological heterogeneity and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 1 All‐cause mortality (longest period reported) excluding studies at high risk of bias.

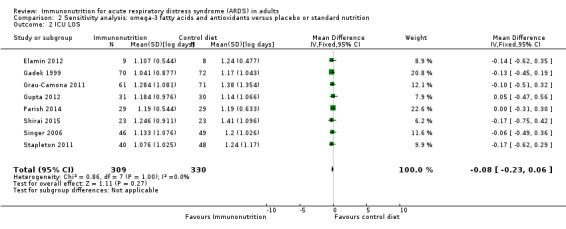

Sensitivity analysis for secondary outcomes with log‐transformed data

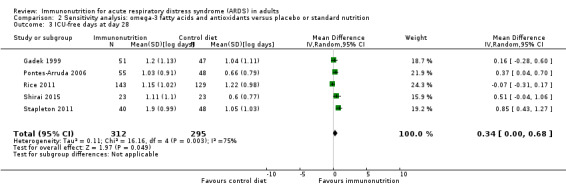

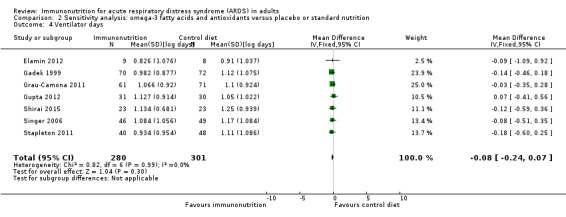

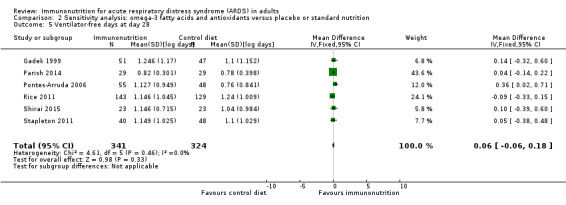

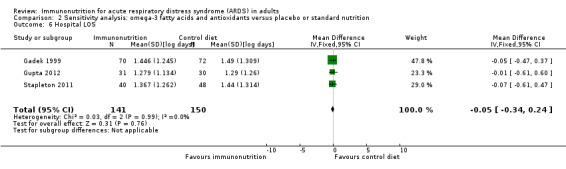

Most data for continuous secondary outcomes such as ICU LOS (Analysis 1.3), ICU‐free days at day 28 (Analysis 1.4), ventilator days (Analysis 1.5), ventilator‐free days at day 28 (Analysis 1.6), and hospital LOS (Analysis 1.7) were skewed. Therefore, we performed sensitivity analysis for these outcomes from log‐transformed data. We are uncertain whether this intervention confers any beneficial effect on ICU length of stay (mean log days ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.06; participants = 639; studies = 8; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.2), ICU‐free days at day 28 (mean log days 0.34, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.68; participants = 607; studies = 5; I² = 75%; Analysis 2.3), ventilator days (mean log days ‐0.08, 95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.07; participants = 581; studies = 7; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.4), ventilator‐free days at day 28 (mean log days 0.06, 95% CI ‐0.06 to 0.18; participants = 665; studies = 6; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.5), or hospital LOS (mean log days ‐0.05, 95% CI ‐0.34 to 0.24; participants = 291; studies = 3; I² = 0%; Analysis 2.6). We downgraded the quality of evidence for all these outcomes by three levels due to increased risk of bias, inconsistency due to clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and indirectness for intervention and comparator.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 2 ICU LOS.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 3 ICU‐free days at day 28.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 4 Ventilator days.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 5 Ventilator‐free days at day 28.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition, Outcome 6 Hospital LOS.

Sensitivity analysis for secondary outcomes of ICU‐free days and ventilator‐free days at day 28 according to statistical method

We performed sensitivity analysis using both fixed‐effect and random‐effects models for secondary outcomes of ICU‐free days and ventilator‐free days at day 28. Results were sensitive to the type of analytical method used (random‐effects or fixed‐effect model) (Table 2).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating effects of omega‐3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)), gamma‐linolenic acid (GLA), and antioxidants, supplemented or given as part of an enteral nutrition formula, for the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) population. We identified no clinical trials with any other specific immunonutrition intervention for this patient population. We found no evidence that this type of nutrition improves the primary outcome of all‐cause mortality at the longest period reported. Included studies showed clinical heterogeneity with respect to type, mode, and duration of intervention provided and type of enteral nutrition formulation received by the control group. We have performed subgroup analysis according to differing interventions in the control group. Although we noted a statistical reduction in mortality when omega‐3 fatty acids and/or antioxidants were compared with a lipid‐rich enteral formula, we are uncertain due to very low‐quality evidence whether this intervention improves mortality in the ARDS population. We also found uncertain evidence regarding reductions in duration of mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit (ICU) length of stay, improvement in oxygenation, and increased adverse events with this intervention.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We performed appropriate and thorough searches of electronic databases to identify suitable studies. We applied no restrictions. We obtained additional study details from study authors when possible. Our meta‐analysis incorporated 10 clinical trials of 1015 participants investigating immune‐modifying nutrition in patients with ARDS. All studies used omega‐3 fatty acid‐based nutritional formula with or without antioxidants for the intervention. However, this approach was subject to significant clinical and statistical heterogeneity. Overall, pooled data did not support giving omega‐3 fatty acids in combination with GLA and antioxidants to improve mortality in ARDS. Although results from some subgroup analyses indicate that the mortality risk ratio (RR) was reduced when the intervention was given as a continuous enteral infusion against a lipid‐rich control formulation, the quality of evidence is very low. Also, the isocaloric high‐fat formula used in the control group diet was enriched in omega‐6 fatty acids with high content of linolenic acid and may have been harmful: in other words, the beneficial effect reported by those studies may have been due to potentially harmful effects of the lipid‐rich diet given to the control group.

Given that mechanical ventilator days and length of ICU stay (ICU LOS) may be influenced by the death rate, critical care clinical trials more recently have widely reported ventilator and ICU‐free days as better outcome measures. In general, ventilator‐free days and ICU‐free days at day 28 are used as a surrogate for overall ICU outcomes combining mortality with duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay, respectively. Study results show a difference in the pooled statistical analysis between outcomes of ICU LOS and ICU‐free days at day 28. This was also true for ventilator days and ventilator‐free days at day 28. Reporting of either numbers of days or numbers of free days (ventilation or ICU) can be subject to bias. For this reason, we meta‐analysed both ways of reporting all available data from published trials (ventilator days/ventilator‐free days at day 28 and ICU LOS)/ICU‐free days at day 28). Alternatively, this disagreement between our secondary composite outcomes (ICU LOS/ ventilator days and ICU‐free days/ventilator‐free days at day 28) and individual endpoints could be due to inclusion and exclusion of different studies from outcome analyses, based on available outcome measures or due to lack of standardized reporting. Nevertheless, due to low‐quality evidence, we are uncertain whether use of an omega‐3‐based immune‐modulating diet in ARDS improves ventilator days or ICU length of stay.

Quality of the evidence

Some studies did not provide adequate descriptive evidence for methods of randomization and allocation concealment. One study was unblinded, and two studies did not adequately clarify blinding of outcome assessment. Significant dropouts from several studies occurred for a variety of reasons, including protocol violations and intolerance of the intervention or trial. We graded these studies as having high risk of bias. Most studies reported anticipated outcomes and all reported mortality, although they were not adequately powered to detect differences between groups. We graded the quality of evidence for the primary outcome as low and for all secondary outcomes as very low because, despite the possibility of increased risk of bias, the primary outcome analysis included more than 1000 patients with more than 250 events and was not influenced by inclusion of studies with high risk of bias, as evidenced by the sensitivity analysis omitting these studies. Analyses of continuous outcome data for most secondary outcomes yielded skewed results. We were not able to obtain the raw transformed data from study authors; therefore, we performed sensitivity analysis using logarithmic transformations for these secondary outcomes. We encountered substantial statistical heterogeneity for several secondary outcomes. Significant clinical and statistical heterogeneity led to a priori defined subgroup analyses of the primary outcomes, according to the type of intervention provided. Several included studies showed indirectness, whereby the comparator was given nutrition with highly enriched omega‐6 fatty acids, which may have increased risk of harm. One study reported significant differences in the amount of protein given per day to control (20 g) and intervention groups (4 g). Overall, we rated the quality of evidence as low to very low because of increased risk of bias, skewed data, inconsistency, and indirectness. Further research on this topic is essential both to address the overall objective of this review and to focus on specific questions. Future RCTs should consider standardized reporting of ICU outcomes to facilitate the combination and comparison of data between studies.

Potential biases in the review process

To our knowledge, we have identified and included all published studies on this topic. Lack of standardization in reporting outcomes resulted in some studies reporting duration of ICU stay as ICU LOS and others as ICU‐free days at day 28. We encountered similar issues when dealing with duration of mechanical ventilation. This resulted in pooling of these studies separately, which was not planned when the protocol was drafted. Lack of standardized statistical data from the included studies led to assumptions of normal distribution and calculations of standard deviation from standard error, interquartile ratio (IQR), and P value, which may have introduced additional bias.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Pontes‐Arruda 2008 conducted the first meta‐analysis on this topic. These review authors included three earlier studies and reported a survival advantage, improvement in oxygenation (days 4 and 7), and other clinical variables such as ICU‐ free days and ventilator‐free days at day 28 with immune‐enhancing diets (Gadek 1999; Pontes‐Arruda 2006; Singer 2006). Another meta‐analysis that focused on mortality and oxygenation yielded the same conclusions (Dee 2011). Results from a subsequent meta‐analysis of seven studies contradicted these previous positive findings and revealed that enteral supplementation of omega‐3 fatty acids, GLA, and antioxidants provides no benefit in reducing clinical outcomes such as 28‐day mortality, ventilator‐free days, and ICU‐free days (Zhu 2014). However, these results show improvement in oxygenation at days 4 and 7 with immune‐modulating diets. A more recent meta‐analysis led to similar conclusions (Li 2015). In this review, authors also subanalysed studies with high overall mortality and demonstrated a positive outcome with the intervention for patient groups with higher mortality, inferring potential benefit for those with severe ARDS (Li 2015).

Our meta‐analysis was consistent with the conclusions of recently published reviews in finding no mortality benefit derived from immunomodulatory diets based on inclusion of omega‐3 fatty acids, GLA, and antioxidants. We noted no improvement in ventilator‐free days and ICU‐free days at day 28, and this was sensitive to analytical methods. These findings were also consistent with those revealed by a previous meta‐analysis (Zhu 2014). Our findings are also consistent with guidelines of the Society of Critcal Care Medicine and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition for provision of nutritional support for adult critically ill patients, which do not recommend use of omega‐3 fatty acids in the ARDS population (McClave 2016).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This meta‐analysis evaluated 10 heterogenous studies of varying quality and analysed effects of omega‐3 fatty acids and/or antioxidants in critically ill adults with ARDS. We were not able to find clinical trials of any other immunonutrition intervention provided to this patient group. Despite inclusion of all studies in our meta‐analysis, we were not able to pool all studies for every anticipated clinical outcome due to lack of standardized outcome reporting. This may have introduced bias into our analysis. Our results suggest that no mortality benefit is derived from the use of omega‐3 fatty acids and/or antioxidants in ARDS. Uncertain evidence suggests reductions in duration of mechanical ventilation and ICU length of stay, along with improved oxygenation. The quality of evidence was very low due to several factors, including poor quality small trials with high risk of bias, clinical and methodological heterogeneity, and issues due to imprecision and inconsistency between trials, with additional indirectness due to an imbalance in nutrition provided to the comparator groups.

Implications for research.

Research shows no mortality benefit associated with use of immunonutrition in ARDS populations. Current data do not justify a large randomized controlled trial on this topic but would support targeted proof‐of‐concept studies in particular groups of patients to refine the intervention. Consistent reporting of outcome measures by researchers will be important to allow combinations of results in subsequent meta‐analyses. Mortality is unlikely to be the best outcome measure for such studies. Cost‐effectiveness data are notably absent from current studies and should be collected in the future. The most promising areas for future evaluation include continuous supplementation with a balanced formula for both control and intervention groups with additional supplementation for the intervention group.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Karen Hovhannisyan for help to design the searches, and Jane Cracknell, Managing Editor of the Cochrane Anaesthesia Critical and Emergency Care Group, for her assistance.

We would like to thank Bronagh Blackwood (Content Editor), Nathan Pace (Statistical Editor), Davoud Vahabzadeh and Thomas Bongers (Peer Reviewers), Patricia Tong (Consumer Referee), and Harald Herkner (Co‐ordinating Editor) for help and editorial advice provided during preparation of this systematic review.

We also would like to thank Rodrigo Cavallazzi (Content Editor), Jing Xie (Statistical Editor), and Todd Rice and Davoud Vahabzadeh (Peer Reviewers) for help and editorial advice provided during preparation of the protocol for this systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Free‐text terms

1. ARDS

2. Acute respiratory distress syndrome

3. Acute lung injury

4. ALI

5. Essential fatty acids

6. Diet

7. Nutrition

8. Immunonutrition

9. Micronutrient

10. Macronutrient

11. Glutamine

12. Arginine

13. Leucine

14. Antioxidants

15. Vitamin C

16. Vitamin E

17. Fish oil

18. Omega‐3 fatty acid

19. n‐3 fatty acid

20. Eicosapentaenoic acid

21. Docosahexaenoic acid

22. Gamma‐linolenic acid

23. Clinical trials

24. Controlled clinical trials

25. Randomized controlled trials

Appendix 2. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 Acute respiratory distress syndrome

#2 Acute lung injury

#3 #1 OR #2

#4 Diet

#5 Nutrition

#6 Immunonutrition

#7 Macronutrient

#8 Micronutrient

#9 Amino acids

#10 Glutamine

#11 Arginine

#12 Leucine

#13 Vitamin

#14 Carotenoids

#15 Ascorbic acid

#16 Selenium

#17 Zinc

#18 Antioxidants

#19 Omega‐3 fatty acids

#20 n‐3 fatty acids

#21 Eicosapentaenoic acid

#22 Docosahexaenoic acid

#23 #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22

#24 #3 and #23

Appendix 3. OVID MEDLINE search strategy

1. exp Acute Lung Injury/ or exp Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult/ or (ALI or ARDS).ti,ab. or (acute adj4 (lung injur* or distress syndrome)).mp. or ((severe or hypoxic) adj4 (respiratory and failure)).mp. 2.(Enteral Nutrition/ and Immune System/) or ((dietary or nutrient*) adj3 (modulation or immune system)).mp. or dietary nutrient*.ti,ab. or immunonutrition.af. or Antioxidants/ or Vitamin E/ or Carotenoids/ or Ascorbic Acid/ or Selenium/ or Zinc/ or exp Amino Acids, Essential/ or Glutamine/ or Arginine/ or exp Fatty Acids, Essential/ or Fatty Acids, Omega‐3/ or (anti?oxidant* or vitamin* or beta?caroten* or glutamine or arginine or omega?3 or selenium or zinc).ti,ab. 3. 1 and 2 4. ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 5. 3 and 4

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

1. exp Acute Lung Injury/ or exp Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Adult/ or (ALI or ARDS).ti,ab. or (acute adj4 (lung injur* or distress syndrome)).mp. or ((severe or hypoxic) adj4 (respiratory and failure)).mp. 2.(Enteral Nutrition/ and Immune System/) or ((dietary or nutrient*) adj3 (modulation or immune system)).mp. or dietary nutrient*.ti,ab. or immunonutrition.af. or Antioxidants/ or Vitamin E/ or Carotenoids/ or Ascorbic Acid/ or Selenium/ or Zinc/ or exp Amino Acids, Essential/ or Glutamine/ or Arginine/ or exp Fatty Acids, Essential/ or Fatty Acids, Omega‐3/ or (anti?oxidant* or vitamin* or beta?caroten* or glutamine or arginine or omega?3 or selenium or zinc).ti,ab. 3. 1 and 2 4. ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomized.ab. or placebo.ab. or drug therapy.fs. or randomly.ab. or trial.ab. or groups.ab.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. 5. 3 and 4

Appendix 5. Data extraction form

| 1. General study information | |

| Study title | [Title] |

| Study ID | |

| Study reference | |

| Publication type | |

| Study sites | |

| Population studied | |

| ARDS definition | |

| Timing of recruitment to onset | |

| No. of patients screened/randomized/ITT in control | |

| No. of patients screened/randomized/ITT in intervention | |

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Intervention type | |

| Intervention delivery method | |

| Intervention dose and duration | |

| Overall follow‐up period | |

| Significant dropouts |

| 2. 'Risk of bias' assessment ‐ domains | Risk | Supporting statement |

| Random sequence generation | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Allocation concealment | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Blinding of participants and personnel | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Incomplete outcome data | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Selective outcome reporting | Low/Unclear/High | |

| Other bias | Low/Unclear/High |

| 3. Outcomes reported | ||

| Outcome (type) | ||

| Definition of outcome | ||

| Dichotomous/continuous outcome | ||

| Unit of measurement | ||

| Time points measured/reported | ||

| Results | Intervention group | Control group |

| Dropouts | ||

| ITT | ||

| Statistical analysis | ||

| Unit of analysis | ||

| Any other notes | ||

| 4. Additional key notes |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause mortality (longest period reported) | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.59, 1.07] |

| 2 28‐day mortality | 6 | 466 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.49, 0.84] |

| 3 ICU LOS | 8 | 639 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐3.09 [‐5.19, ‐0.99] |

| 4 ICU‐free days at day 28 | 5 | 607 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 3.44 [‐1.17, 8.06] |

| 5 Ventilator days | 7 | 581 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.24 [‐3.77, ‐0.71] |

| 6 Ventilator‐free days at day 28 | 6 | 665 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 2.15 [‐0.91, 5.22] |

| 7 Hospital LOS | 3 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐2.79 [‐7.01, 1.44] |

| 8 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 4 | 8 | 676 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 38.88 [10.75, 67.02] |

| 9 PaO₂/FiO₂ ratio at day 7 | 9 | 465 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 23.44 [1.73, 45.15] |

| 10 Patients with new organ failure | 2 | 249 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.32, 0.63] |

| 11 Patients with nosocomial infection | 3 | 450 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.76, 1.33] |

| 12 Adverse events ‐ cardiac | 3 | 339 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.09, 8.46] |

| 13 Adverse events ‐ gastrointestinal | 4 | 427 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.71, 1.75] |

| 14 Total adverse events | 5 | 517 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.67, 1.23] |

| 15 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ type of intervention | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.59, 1.07] |

| 15.1 Immunonutrition formula compared with lipid‐based control diet | 4 | 361 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.57 [0.42, 0.78] |

| 15.2 Immunonutrition formula compared with carbohydrate‐based control diet | 2 | 178 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.57, 2.22] |

| 15.3 Immunonutrition supplemented to same intervention and control diet | 3 | 204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.48, 1.15] |

| 15.4 Immunonutrition supplemented to different intervention and control formula | 1 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.01, 2.63] |

| 16 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ route of intervention | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.59, 1.07] |

| 16.1 Enteral | 9 | 954 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.59, 1.14] |

| 16.2 Intravenous | 1 | 61 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.32, 1.22] |

| 17 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ mode of intervention (bolus or continuous) | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.59, 1.07] |

| 17.1 Continuous infusion | 7 | 600 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.49, 0.83] |

| 17.2 Bolus supplementation | 3 | 415 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.72, 1.88] |

| 18 Subgroup analysis for the primary outcome (all‐cause mortality) ‐ duration of intervention | 10 | 1015 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.59, 1.07] |

| 18.1 Duration < 7 days | 2 | 163 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.32, 1.17] |

| 18.2 Duration 14 days | 5 | 345 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.47, 0.89] |

| 18.3 Duration 21 days | 1 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.63 [1.01, 2.63] |

| 18.4 Duration 28 days | 2 | 235 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.44, 1.44] |

Comparison 2. Sensitivity analysis: omega‐3 fatty acids and antioxidants versus placebo or standard nutrition.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 All‐cause mortality (longest period reported) excluding studies at high risk of bias | 4 | 561 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.60, 1.58] |

| 2 ICU LOS | 8 | 639 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.23, 0.06] |

| 3 ICU‐free days at day 28 | 5 | 607 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.00, 0.68] |

| 4 Ventilator days | 7 | 581 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.24, 0.07] |

| 5 Ventilator‐free days at day 28 | 6 | 665 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.06, 0.18] |

| 6 Hospital LOS | 3 | 291 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.05 [‐0.34, 0.24] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Elamin 2012.

| Methods |

Design: prospective, randomized, controlled, double‐blinded Country: USA Setting: mixed surgical and medical intensive care unit Multi‐centre: yes Date of study: not stated |

|

| Participants |

Inclusion criteria: age 18 to 80 years, patients with ARDS defined by AECC criteria Control group (N) = 8 Intervention group (N) = 9 Age (mean, SD): Control group: 55.2 ± 16.5 Intervention group: 50 ± 22.2 Exclusion criteria:

|