Abstract

Background

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) experience sleep deprivation caused by environmental disruption, such as high noise levels and 24‐hour lighting, as well as increased patient care activities and invasive monitoring as part of their care. Sleep deprivation affects physical and psychological health, and patients perceive the quality of their sleep to be poor whilst in the ICU. Artificial lighting during night‐time hours in the ICU may contribute to reduced production of melatonin in critically ill patients. Melatonin is known to have a direct effect on the circadian rhythm, and it appears to reset a natural rhythm, thus promoting sleep.

Objectives

To assess whether the quantity and quality of sleep may be improved by administration of melatonin to adults in the intensive care unit. To assess whether melatonin given for sleep promotion improves both physical and psychological patient outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 8), MEDLINE (1946 to September 2017), Embase (1974 to September 2017), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1937 to September 2017), and PsycINFO (1806 to September 2017). We searched clinical trials registers for ongoing studies, and conducted backward and forward citation searching of relevant articles.

Selection criteria

We included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials with adult participants (over the age of 16) admitted to the ICU with any diagnoses given melatonin versus a comparator to promote overnight sleep. We included participants who were mechanically ventilated and those who were not mechanically ventilated. We planned to include studies that compared the use of melatonin, given at an appropriate clinical dose with the intention of promoting night‐time sleep, against no agent; or against another agent administered specifically to promote sleep.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for inclusion, extracted data, assessed risk of bias, and synthesized findings. We assessed the quality of evidence with GRADE.

Main results

We included four studies with 151 randomized participants. Two studies included participants who were mechanically ventilated, one study included a mix of ventilated and non‐ventilated participants and in one study participants were being weaned from mechanical ventilation. Three studies reported admission diagnoses, which varied: these included sepsis, pneumonia and cardiac or cardiorespiratory arrest. All studies compared melatonin against no agent; three were placebo‐controlled trials; and one compared melatonin with usual care. All studies administered melatonin in the evening.

All studies reported adequate methods for randomization and placebo‐controlled trials were blinded at the participant and personnel level. We noted high risk of attrition bias in one study and were unclear about potential bias introduced in two studies with differences between participants at baseline.

It was not appropriate to combine data owing to differences in measurement tools, or methods used to report data.

The effects of melatonin on subjectively rated quantity and quality of sleep are uncertain (very low certainty evidence). Three studies (139 participants) reported quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or family members or by personnel assessments. Study authors in one study reported no difference in sleep efficiency index scores between groups for participant assessment (using Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire) and nurse assessment. Two studies reported no difference in duration of sleep observed by nurses.

The effects of melatonin on objectively measured quantity and quality of sleep are uncertain (very low certainty evidence). Two studies (37 participants) reported quantity and quality of sleep as measured by polysomnography (PSG), actigraphy, bispectral index (BIS) or electroencephalogram (EEG). Study authors in one study reported no difference in sleep efficiency index scores between groups using BIS and actigraphy. These authors also reported longer sleep in participants given melatonin which was not statistically significant, and improved sleep (described as "better sleep") in participants given melatonin from analysis of area under the curve (AUC) of BIS data. One study used PSG but authors were unable to report data because of a large loss of participant data.

One study (82 participants) reported no evidence of a difference in anxiety scores (very low certainty evidence). Two studies (94 participants) reported data for mortality: one study reported that overall one‐third of participants died; and one study reported no evidence of difference between groups in hospital mortality (very low certainty). One study (82 participants) reported no evidence of a difference in length of ICU stay (very low certainty evidence). Effects of melatonin on adverse events were reported in two studies (107 participants), and are uncertain (very low certainty evidence): one study reported headache in one participant given melatonin, and one study reported excessive sleepiness in one participant given melatonin and two events in the control group (skin reaction in one participant, and excessive sleepiness in another participant).

The certainty of the evidence for each outcome was limited by sparse data with few participants. We noted study limitations in some studies due to high attrition and differences between groups in baseline data; and doses of melatonin varied between studies. Methods used to measure data were not consistent for outcomes, and use of some measurement tools may not be effective for use on the ICU patient. All studies included participants in the ICU but we noted differences in ICU protocols, and one included study used a non‐standard sedation protocol with participants which introduced indirectness to the evidence.

Authors' conclusions

We found insufficient evidence to determine whether administration of melatonin would improve the quality and quantity of sleep in ICU patients. We identified sparse data, and noted differences in study methodology, in ICU sedation protocols, and in methods used to measure and report sleep. We identified five ongoing studies from database and clinical trial register searches. Inclusion of data from these studies in future review updates would provide more certainty for the review outcomes.

Plain language summary

Melatonin to improve sleep in the intensive care unit

Background

Patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) experience poor sleep. This may be caused by constant high noise levels and 24‐hour lighting in the ICU, as well as increased and intrusive patient care activities (such as measuring blood pressure, pulse, and temperature; taking blood samples; administering medications, etc.). Lack of sleep affects a person's physical and mental health. It is accepted that sleep is an essential requirement for good health. Sleep has a restorative function, and for the critically ill is thought to improve healing and survival. Patients perceive the quality of their sleep to be poor while they are in the ICU. Melatonin is a hormone produced in the body to regulate a daily cycle of sleep and wakefulness. Artificial light during night‐time hours in the ICU may affect the body's natural production of melatonin, and this may affect the sleep cycle in critically ill patients.

Review question

To assess whether melatonin improves the quantity and quality of sleep for adults in the ICU and improves physical and psychological health.

Study characteristics

The evidence is current to September 2017. We included four studies with 151 participants in the review. All participants were critically ill and were in the ICU. All studies compared melatonin with no agent (an inactive substance called a placebo), or with usual care.

Key results

We did not combine data from the four included studies. Three studies used nurses and participants to assess sleep and reported no difference in quality and quantity of sleep. Two studies used equipment to measure quality and quantity of sleep, and one of these studies reported no difference in sleep efficiency (how well the person sleeps during night‐time hours) according to melatonin use and, according to some analysis, evidence of "better sleep" for those given melatonin. One study reported problems with equipment which led to a loss of data. One study reported no difference in anxiety, and there was no difference in mortality, or length of stay in the ICU. We noted few potential side effects of melatonin (headache in one participant, and excessive sleepiness in another participant).

Quality of the evidence

We noted differences between groups in doses of melatonin and two studies reported differences between groups in participant characteristics which could have affected the results. One study had a large loss of data and another study did not use standard anaesthetic drugs to sedate patients. Few studies used appropriate equipment to measure quantity of sleep. We found few studies with few participants that assessed our review outcomes. We judged all evidence to be very low quality, and we could not be certain whether melatonin given to adults in the ICU improves quantity and quality of sleep. We found five ongoing studies in database and clinical trial register searches. Inclusion of these studies in future review updates would provide more certainty for the review outcomes.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Melatonin compared with no agent for the promotion of sleep in adult patients in the ICU | ||||

|

Patient or population: adult patients in the ICU Settings: ICUs, in Australia, Italy, UK, and US Intervention: melatonin Comparison: no agent | ||||

| Outcomes | Impacts | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

|

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or of family members or by personnel assessments Data collected at end of follow‐up |

In 1 study, participants completed the RCSQ and study authors reported no difference in SEI scores between groups. This was consistent with nurse assessment for which study authors also reported no difference in SEI scores between groups 2 studies reported no difference in duration of sleep observed by nurses |

139 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowa | We did not conduct meta‐analysis because studies used different methods to report data |

|

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured by PSG, actigraphy, BIS, or EEG Data collected at end of follow‐up |

In 1 study, investigators used BIS and actigraphy to record sleep. Study authors reported no difference in SEI scores with both tools. Study authors also reported longer sleep in participants given melatonin which was not statistically significantly different, and also reported evidence of improved sleep in participants given melatonin from analysis of AUC using BIS data 1 study used PSG, with a large loss of participant data at follow‐up, which prevented analysis of sleep data |

37 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowb | We did not conduct meta‐analysis because studies differed in types of measurement tools |

|

Anxiety or depression, or both Data collected at end of follow‐up |

1 study (using VNR ≥ 3) reported no evidence of a difference in anxiety scores between groups | 82 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowc | We identified only one study and could not conduct meta‐analysis |

|

Mortality Study authors did not report final timepoint for data collection. |

1 study reported one‐third of participants had died; number of deaths per group was not reported 1 study reported no evidence of a difference between groups in hospital mortality |

94 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd | We did not conduct meta‐analysis because studies different in methods of reporting data |

| Length of stay in the ICU | One study reported no evidence of a difference in length of ICU stay between groups | 82 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowe | We identified only 1 study and could not conduct meta‐analysis |

|

Adverse events (such as nausea, dizziness and headache) Data collected at end of follow‐up |

1 study reported headache in one participant who was given melatonin 1 study reported a cutaneous rash in one participant in the control group, and 2 participants (1 participant in both groups) with excessive sleepiness |

107 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowf | We could not conduct meta‐analysis because studies different in reported types of adverse events |

|

Acronyms and abbreviations AUC: area under the curve; BIS: bispectral index; EEG: electroencephalogram; ICU: intensive care unit; PSG: polysomnography; RCSQ: Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire; SEI: sleep efficiency index; VNR: verbal numeric range | ||||

| GRADE Working Group Grades of Evidence High quality: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: we are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||

aWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; there were few studies with few participants, and outcome measures included both personnel and participant reports. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; we noted differences in baseline characteristics in two studies which may have influenced results. We downgraded by 1 level for inconsistency; we noted differences in doses of melatonin given in each study. We downgraded by 1 level for indirectness; we could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in one study were generalizable to most ICUs

bWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; there were few studies very few participants, and outcome measures used different assessment tools which may not effectively measure sleep in the ICU patient. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; we noted differences in baselines characteristics in one study which may have influenced results. We downgraded 1 level for inconsistency; we noted differences in doses of melatonin given in each study. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; we noted high risk of performance bias and high attrition which prevented adequate outcome reporting

cWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; data was from one study with few participants, and we could not be certain whether this outcome was measured with an appropriate tool for patients in the ICU. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; pre‐treatment use of opiates differed between study groups. We downgraded by 1 level for indirectness; we could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in 1 study were generalizable to most ICUs

dWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; there were few studies with few participants. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; we noted a high risk of performance bias and attrition bias in one study and we noted differences between groups in pre‐treatment use of opiates. We downgraded 1 level for inconsistency; doses of melatonin varied between studies. We downgraded by 1 level for indirectness; we could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in 1 study were generalizable to most ICUs

eWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; data was from one study. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; pre‐treatment use of opiates differed between study groups. We downgraded by 1 level for indirectness; we could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in 1 study were generalizable to most ICUs

fWe downgraded by 2 levels for imprecision; there were few studies with few participants. We downgraded by 1 level for study limitations; we noted differences in baseline characteristics in two studies which may have influenced results. We downgraded by 1 level for indirectness; we could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in 1 study were generalizable to most ICUs

Background

This is one of two reviews performed to examine the use of pharmacological agents to promote sleep in the intensive care unit with similar text linked across the reviews (Lewis 2016a).

Description of the condition

It is accepted that sleep is an essential requirement for good health. Sleep has a restorative function, and for the critically ill is thought to improve healing and survival (Tembo 2009).

Sleep naturally follows a circadian rhythm of approximately 24 hours, in a diurnal pattern of once a day. Each period of sleep consists of phases lasting 90 minutes, with typical sleep ‘architecture’ involving a period of rapid eye movement (REM) and non‐rapid eye movement (NREM). The NREM stage is subdivided into three phases, now labelled as N1, N2, and N3 (also described as 'slow wave patterns'). The REM stage accounts for 15% to 20% of sleep time, and N2 of NREM for approximately 50% (Matthews 2011; Schupp 2003; Silber 2007).

It is likely that patients in hospital will be subject to sleep disturbances; this is particularly likely for those in the intensive care unit (ICU). These patients are critically ill with diagnoses such as respiratory insufficiency or failure, need for postoperative management, ischaemic heart disorder, sepsis, and heart failure (Society of Critical Care Medicine). Patients may require specialist support after elective surgery, or may be emergency admissions following medical events or trauma (e.g. with multiple injuries after a road traffic accident) (Intensive Care Foundation).

In the ICU, the ratio of staff to patients is higher than in general wards and the environment typically includes 24‐hour lighting, a constant level of noise, and more frequent patient care activities (measuring blood pressure, pulse, and temperature; taking blood samples; administering medications, etc.) than in general wards. Many patients are mechanically ventilated (up to 40%; Esteban 2000); and are subject to invasive procedures such as tracheal intubation and use of nasogastric tubes (Esteban 2000). In addition, patients in the ICU have critical conditions that involve pain, anxiety, and stress (Kamdar 2012a).

Patients are often prescribed drugs that further contribute to sleep loss. For example, drugs such as benzodiazepines are given for essential sedation (particularly to mechanically ventilated patients) to relieve discomfort and stress. These agents alter sleep architecture so that N2 of NREM is longer than normal, prolonging sleep. However, they also reduce essential REM and N3 phases of sleep (Bourne 2004). Similarly, opioids for analgesia are commonly used in the ICU, and studies report that these agents, even when given in low doses and to healthy volunteers, reduce the amount of deep sleep by up to 50% (Dimsdale 2007; Grounds 2014).

Patients perceive that the quality of their sleep in the ICU is disrupted by frequent awakenings and increased daytime sleep (Freedman 1999). This perception is supported by trials that assessed sleep by using objective measures. Polysomnography readings, which use a variety of channels to measure electrical activity of the heart, as well as muscle tension, airflow and eye movement, can be used to assess sleep. Patients in the ICU have been shown to have alterations to their circadian rhythm, with up to 50% of sleep occurring during the day, and with sleep arousals occurring as often as 39 times per hour in mechanically ventilated patients (Parthasarathy 2004). Changes to sleep ‘architecture’ are significant, with reductions in both REM and N3 sleep (Cooper 2000; Drouot 2008).

Empirical evidence on immediate and long‐term physical consequences of sleep deprivation for patients in the ICU is limited, but data suggest that sleep loss in healthy participants can result in physical alterations to the immune system, as well as changes in metabolism, nitrogen balance, and ventilatory and cardiovascular systems (Kamdar 2012a; Matthews 2011; Pisani 2015; Weinhouse 2006). For example, after loss of only one night's sleep, biomarkers are released that are present in patients with coronary artery disease (Sauvet 2010), although no longitudinal studies have demonstrated that sleep disturbance in the ICU results in increased cardiovascular mortality (Kamdar 2012a). Psychological consequences of sleep loss in healthy participants include depression, anxiety, and stress (Kamdar 2012a); and these symptoms, along with symptoms such as post‐traumatic stress disorder, may be experienced for several months after ICU discharge by survivors of critical illness (Eddleston 2000; Figueroa‐Ramos 2009; Kamdar 2012a; Matthews 2011). However, the association between these long‐term symptoms and sleep disruption during the ICU stay is not known (Kamdar 2012a).

Description of the intervention

Non‐pharmacological interventions, such as noise and light reduction strategies (e.g. earplugs, eyemasks; Richardson 2007), have been studied specifically in the ICU, and some have been shown to improve the quality of sleep. A Cochrane Review has explored the effectiveness of these various strategies (Hu 2015).

This review aims to look at administration of melatonin to adults in the ICU to promote sleep. This molecule is naturally synthesized in the pineal gland during night‐time darkness. It is not stored but is immediately released into the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid. Melatonin can be given in tablet, capsule, or liquid form, for immediate or prolonged release. It has few side effects (including headache, dizziness, and nausea); a systematic review found no significant differences in the number of side effects reported when melatonin was used for primary sleep disorders (Buscemi 2005).

How the intervention might work

Artificial lighting during night‐time hours in the ICU may contribute to reduced production of melatonin in critically ill patients. Melatonin is known to have a direct effect on the circadian rhythm and, although it is not a hypnotic agent, it appears to reset a natural rhythm, thus promoting sleep (Reiter 2003). Cochrane Reviews have demonstrated increased length of sleep with melatonin after disruption from shift work (Liira 2014), reduction in preoperative anxiety (Hansen 2015), and reduction in, or prevention of, jet lag (Herxheimer 2002). It is possible that administration of melatonin orally or intravenously to patients in the ICU setting may entrain a circadian rhythm.

Why it is important to do this review

The James Lind Alliance, a priority‐setting organization that works with patients, carers, and clinicians to establish research priorities for health care, recently published its top 10 priorities for research in the intensive care setting (www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/top‐tens/intensive‐care‐top‐10). Among these are research topics relevant to enhancing patient comfort in the ICU (including minimizing pain, discomfort, agitation, and anxiety), preventing physical consequences of critical illness, and providing psychological support for patients.

Although sleep disruption may affect many hospital patients, those in the ICU are particularly vulnerable to disturbances that may subsequently lead to physical and psychological consequences, such as those identified above. No Cochrane Reviews have assessed whether pharmacological agents provide benefit in promoting patient sleep in the ICU, and whether effectively promoting sleep will improve patient outcomes and provide immediate and long‐term clinical benefits. This review will address James Lind Alliance priority targets by assessing the effectiveness of melatonin for sleep promotion in the ICU setting.

Objectives

To assess whether the quantity and quality of sleep may be improved by administration of melatonin to adults in the intensive care unit. To assess whether melatonin given for sleep promotion improves both physical and psychological patient outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized controlled trials (for example, studies in which participants were assigned by alternation, date of birth, or medical record number).

Types of participants

We included adult participants over 16 years of age who were admitted to any ICU as emergency, medical, or postoperative elective surgical patients. We did not limit types of participants by severity of the condition. We included participants who were mechanically ventilated and those who were not mechanically ventilated.

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared the use of melatonin given at an appropriate clinical dose with the intention of promoting night‐time sleep, against:

no agent; or

another agent, administered specifically to promote sleep.

Types of outcome measures

We were interested in quantity and quality of sleep. The experience of sleep may not always be representative of objectively measured sleep, and given that patients perceive that they have disrupted sleep while in the ICU (Freedman 1999), we included this outcome, regardless of whether validated scales had been used for measurement. An added issue for this outcome is that critically ill patients may have limited or no ability to communicate. Therefore, we were equally interested in the perceptions of carers and family members who may have an impression of sleep from the bedside, and in subjective measures used by personnel to assess sleep. We included assessments of sleep that have been performed at the end of follow‐up, as defined by study authors, for example in the morning or during the daytime that followed administration of the intervention. We included assessments that were completed with the use of scales, whether validated or not, and modified for each user, such as the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (Richards 2000), or through compilation of sleep diaries, such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Diary (Monk 1994).

Study authors may use scales to determine levels of participant consciousness and we aimed to report study authors' interpretations of these scales. For example, participants may be sedated at level 3 on the Ramsay Sedation Scale (“Patient responds to commands only”) and may be in a sleep‐like state at level 4 or 5 on this scale (“Patient exhibits brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus” or “Patient exhibits a sluggish response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus”) (Ramsay Sedation Scale).

We reported the quantity and quality of sleep as measured by objective equipment. In particular, polysomnography (PSG) is considered the most accurate and objective tool that can be used to measure sleep and to identify sleep disorders (Beecroft 2008). PSG measurements can be analysed to detect sleep onset, sleep efficiency, and length of sleep stages, as well as irregularities, such as apnoea and interrupted sleep. We also accepted measurements obtained when other tools had been used to record sleep activity (Beecroft 2008; Benini 2005; Elliott 2013): ‘actigraphy’ is a wristband‐style tool that measures gross motor activity and is analysed to score total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and awakenings; bispectral index (BIS) is typically used to calculate depth of anaesthesia through interpretation of an electroencephalogram (EEG) reading; and measures of EEG alone can be used to interpret electrical brain activity as sleep time. We acknowledge that collection and interpretation of data using objective tools may be problematic in people who are critically ill because manual methods have poor inter‐rater reliability (Ambrogio 2008); people who are critically ill may have various forms of encephalopathy (septic, toxic, or metabolic) or may be treated with intravenous sedatives and these factors may make interpretation of EEG readings more problematic. We used interpretations of these measurements as reported by each study author to define the quantity and quality of sleep.

Our aim was to establish not only whether melatonin improves sleep but whether improvement in sleep leads to better patient outcomes. This was reflected in our secondary outcome measure, which considered potential physical and psychological consequences of sleep loss, although we acknowledge that it may not be possible to ascertain whether a reduction in such events is directly attributable to improved sleep. We assessed physical consequences of sleep loss by collecting data from studies that reported the number of participants who had had an adverse event during follow‐up time, as defined by study authors. We assessed psychological consequences of sleep loss by collecting data from studies that reported the number of participants who had been given a diagnosis of anxiety or depression, or both, by using validated assessment tools during the follow‐up period, as defined by study authors.

Primary outcomes

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or family members or by personnel assessments.

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured by PSG, actigraphy, BIS, or EEG.

Secondary outcomes

Anxiety or depression, or both, as measured with the use of validated tools, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983).

Mortality at 30 days.

Length of stay in the ICU.

Adverse events (such as nausea, headache, or dizziness).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified RCTs through literature searching with systematic and sensitive search strategies as outlined in Chapter 6.4 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We applied no restrictions to language or publication status. We searched the following databases for relevant trials.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2017, Issue 8) in the Cochrane Library (searched 26 September 2017)

MEDLINE (Ovid SP, 1946 to 26 September 2017)

Embase (Ovid SP, 1974 to 26 September 2017)

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCO, 1937 to 2 October 2017)

PsycINFO (EBSCO, 1887 to 2 October 2017)

We developed a subject‐specific search strategy in MEDLINE and used that as the basis for the search strategies in the other listed databases. The search strategy was developed in consultation with the Information Specialist. Search strategies can be found in Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4, and Appendix 5.

We scanned the following trial registries for ongoing and unpublished trials (10 July 2017).

The World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHOICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/AdvSearch.aspx)

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) (www.isrctn.com/)

ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Searching other resources

We carried out citation searching of identified included studies in Web of Science (apps.webofknowledge.com), and Google Scholar (scholar.google.co.uk), on 13 July 2017 and conducted a search of grey literature through ‘Opengrey’ (www.opengrey.eu), on 13 July 2017. We carried out backward citation searching of key reviews identified from the searches. We contacted study authors of included trials.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (Sharon Lewis (SL) and Oliver Schofield‐Robinson (OSR)) independently carried out all data collection and analysis before comparing results and reaching consensus. A third review author (Phil Alderson (PA)) was available to resolve conflicts when necessary.

Selection of studies

We used reference management software to collate search results and to remove duplicates (Endnote).

We used Covidence software to screen results of the search from titles and abstracts, and identified potentially relevant studies by using this information alone (Covidence). We sourced the full texts of all potentially relevant studies, and considered whether they met the inclusion criteria (see Criteria for considering studies for this review). We included abstracts at this stage. However, we planned to include abstracts in the review only if they provided sufficient information, and relevant results that included denominator figures for each intervention or comparison group.

We recorded the number of papers retrieved at each stage, and reported this information using a PRISMA flow chart (Liberati 2009). We reported brief details of closely related papers excluded from the review.

Data extraction and management

We used Covidence software to extract the following data from individual studies.

Methods ‒ type of study design; setting; dates of study; and funding sources.

Participants ‒ number of participants randomized to each group; baseline characteristics (to include Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores; mechanical ventilation status and mode of ventilation; length of time in ICU before study commencement; and concomitant medications).

Interventions ‒ details of intervention and comparison agents (to include dose and timing).

Outcomes ‒ review outcomes as measured and reported by study authors (to include types of assessment tools; methods of data synthesis; units of measure; and length of follow‐up).

Outcome data ‒ results of outcome measures.

We considered the applicability of information from individual studies and the generalizability of data to our intended study population (i.e. the potential for indirectness in our review).

If we identified associated publications from the same study, we created a composite dataset from all eligible publications.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed study quality, study limitations, and extent of potential bias by using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011). We considered the following domains.

Random sequence generation (selection bias).

Allocation concealment (selection bias).

Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias).

Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias).

Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias).

Selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Other sources of bias ‒ use of concomitant drugs.

Blinding to intervention and control agents may be feasible if agents are prepared in coded containers, for example, by an independent pharmacist; lack of blinding of personnel may introduce risk of bias. Successful blinding of participants to group allocation would be possible and would reduce performance and detection blinding. It is also feasible that outcome assessors could be blinded to group allocation to reduce bias. As participants were critically ill, we anticipated that rates of mortality and withdrawal of consent might be higher in the studies included in this review. Therefore, we paid particular attention to reasons given for losses, whether losses were related to the intervention or to chance alone, and whether losses were comparable between groups. If participants received concomitant medication (e.g. morphine), we considered whether that medication could affect sleep and whether the concomitant medication was comparable between study groups. We planned to address other potential biases in the included studies on an individual basis.

For each domain, two review authors (SL and OSR) used one of three measures — low risk of bias, high risk of bias, or unclear risk of bias — to independently judge whether study authors made sufficient attempts to reduce bias. We recorded this information in the 'Risk of bias' tables and presented a summary 'Risk of bias' figure.

Measures of treatment effect

We planned to report physical consequences of sleep deprivation and mortality as dichotomous data (number of participant events per group). We planned to report psychological consequences of sleep deprivation as dichotomous or continuous data (e.g. number of participant events per group, mean scores per group on a scale measuring anxiety). We anticipated that measures of participant‐reported outcomes might differ for each study, depending on the scales used, as might objective measures of quantity and quality of sleep.

Unit of analysis issues

If multi‐arm studies compared more than one relevant intervention versus a control (e.g. no agent), we planned to include both intervention groups but planned to split the data for the comparison or control group (using a ‘halving’ method), as recommended by Higgins 2011.

Dealing with missing data

During the data extraction stage, we attempted to contact study authors to obtain missing data. We used available case data if necessary, rather than imputed values.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed whether our results showed evidence of inconsistency by considering heterogeneity. We anticipated likely heterogeneity between studies and assessed clinical and methodological heterogeneity by comparing similarities between participants, interventions, and outcomes in our included studies using information collected during the data extraction phase. We planned to complete meta‐analyses only for studies that were clinically and methodologically similar.

We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity by calculating Chi² (with an associated P value) or the I² statistic (with an associated percentage). We planned to use the following cut‐offs as a guide to interpretation of I² values: 0 to 40% is not considered important, 30% to 60% suggests moderate heterogeneity, 50% to 90% suggests substantial heterogeneity, and 75% to 100% shows considerable heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

As well as looking at statistical results, we planned to consider point estimates and overlap of confidence intervals (CIs). If CIs overlap, then results are more consistent. However, combined studies may show a large consistent effect with significant heterogeneity. Therefore, we planned to interpret heterogeneity with caution (Guyatt 2011b).

Assessment of reporting biases

We attempted to source published protocols for each of our included studies by using clinical trial registers. We planned to compare published protocols with published study results to assess the risk of selective reporting bias.

If we identified sufficient studies (i.e. more than 10 studies) (Higgins 2011), we planned to generate a funnel plot to assess risk of publication bias in the review; an asymmetrical funnel plot may indicate publication of only positive results (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We planned to complete meta‐analyses of outcomes if comparable effect measures were available from more than one study, and only when measures of clinical and statistical heterogeneity indicate that pooling of results was appropriate. We planned to use the statistical calculator in Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014).

We anticipated that our primary objective of subjective sleep measures would collect data from different sources (participants, carers, and personnel). As some evidence suggests that nurses' assessments of sleep may differ from that of patients' (Kamdar 2012b), we did not combine participant‐, family‐, and personnel‐reported assessments of sleep quality, but reported these separately. In addition, subjective sleep assessment tools may not be comparable between studies. If sleep assessment tools included categories of sleep assessment, such as no sleep, minimal sleep, moderate sleep, and majority sleep, we planned to split the data into dichotomous results by comparing the number of people reporting moderate and majority sleep versus the number reporting minimal and no sleep. We planned to combine data across assessment tools if data could be split into equivalent categories; as this was not feasible, we present a descriptive summary of the results of each study.

Similarly, we anticipated that our primary outcome of objective sleep assessment may use different tools that may not be comparable. Because results were not reported with the same tools and with the same measurements, such as mean score for BIS or mean length of each sleep stage for PSG, we present a descriptive summary of the results of each study.

For dichotomous outcomes, we planned to calculate the odds ratio by using summary data presented for each trial. We planned to use the Mantel‐Haenszel effects model, unless events are extremely rare (one per 1000), in which case we planned to use Peto (Higgins 2011). For continuous outcomes, for example PSG readings, we planned to use mean differences. We planned to use a random‐effects statistical model, which allows for the assumption that included studies may estimate different, but related, intervention effects.

We planned to conduct separate analyses for each comparison type (i.e. melatonin vs no agent; melatonin vs a different dose of the same agent; and melatonin vs a different agent).

We planned to calculate CIs at 95% and use a P value of 0.05 or below to judge whether a result was statistically significant.

We planned to consider whether results of analyses were imprecise by assessing the CI around an effect measure; a wide CI would suggest a higher level of imprecision in results. Inclusion of a small number of studies may also reduce precision (Guyatt 2011a).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to assess possible reasons for heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses. We planned to consider the severity of the condition of participants in each study — participants with a more severe condition may already be subject to increased sleep disruption. Similarly, we planned to consider whether participants have a different outcome according to mechanical ventilation status during the study period. We planned also to consider the age of participants — older people (aged > 65 years) have an altered sleep pattern, which includes increased difficulty falling asleep with more awakenings and shorter total sleep time (Ancoli‐Israel 2009), and therefore data on sleep outcomes may be different for members of this patient group than for younger patients.

In summary, subgroups included:

severity of the health condition based on APACHE II scores (or comparable severity measures): APACHE II scores less than 25; 25 to 35; greater than 35;

mechanically ventilated participants versus those not mechanically ventilated;

participants 65 years of age or older versus participants younger than 65 years; and

participants in a surgical ICU versus those in a medical ICU.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to explore potential effects of decisions made as part of the review process as follows.

We planned to exclude all studies that we judged to be at high or unclear risk of selection bias.

We planned to conduct meta‐analyses by using the alternate meta‐analytical effects (fixed‐effect or random‐effects) model.

We planned to compare effect estimates from the above results versus effect estimates from the main analyses. We planned to report differences that alter interpretation of effects.

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses on all outcomes.

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE

The GRADE approach incorporates assessment of indirectness, study limitations, inconsistency, publication bias, and imprecision. We used assessments made during our analysis to inform the GRADE process (see Data extraction and management, Assessment of risk of bias in included studies, Assessment of heterogeneity, Assessment of reporting biases, and Data synthesis, respectively). This approach provides an overall measure of how confident we can be that our estimate of effect is correct (Guyatt 2008).

We used the principles of the GRADE system to provide an overall assessment of evidence related to each of the following outcomes.

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or of family members or by personnel assessments.

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured by PSG, actigraphy, BIS, or EEG.

Anxiety or depression, or both.

Mortality.

Length of stay in the ICU.

Adverse events (such as nausea, dizziness, and headache).

One review author (SL) used GRADEpro software to create a 'Summary of findings' table for each comparison (GRADEpro GDT); and consensus was reached through discussion with a second author (MWP).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

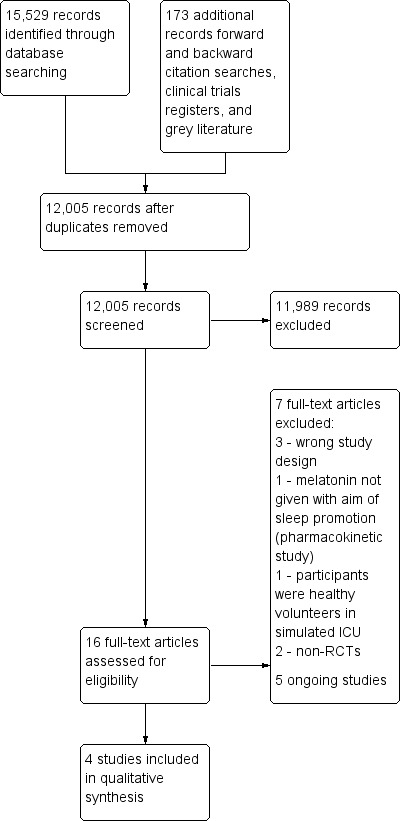

We screened 12,005 titles and abstracts from database searches, results from clinical trial register searches, grey literature searches, and forward and backward citation searches. We carried out full‐text review of 16 articles. We excluded seven studies, and reported details of four of these excluded studies. We identified four eligible studies, and five ongoing studies. See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram

Included studies

We included four parallel design randomized controlled studies with 151 participants (Bourne 2008; Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015). Two studies were described as pilot studies (Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006). See Characteristics of included studies.

Study population and setting

The four included studies enrolled adult participants admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

Two studies included participants that were mechanically ventilated (Bourne 2008; Mistraletti 2015), one study included both participants that were mechanically ventilated and those not mechanically ventilated (Foreman 2015), and one study included participants who were being weaned from mechanical ventilation. Three studies used the APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II) scoring system to classify the severity of participant illness: Bourne 2008 reported a mean (standard deviation (SD)) score in the intervention group of 17.3 (± 3.8) and in the control group of 16.8 (± 3.4); Foreman 2015 reported a mean (SD) score in the intervention group of 13 (± 7) and in the control group of 10 (± 6); and Ibrahim 2006 reported a mean (95% CI) score in the intervention group of 19 (15 to 23) and in the control group of 18 (14 to 23). One study used SAPS II (Simplified Acute Physiology Score II) scoring system to classify severity of participant illness (Mistraletti 2015), and reported a mean (SD) score in the intervention group of 45.7 (± 18.2) and in the control group of 44.1 (± 15.3).

Participant admission diagnoses included severe sepsis, postoperative respiratory failure, or pneumonia (Bourne 2008); acute brain injury, cardiac arrest, or sepsis (Foreman 2015); pneumonia, pancreatic diseases, gastrointestinal diseases, cardiorespiratory arrest, or acute myocardial infarction (Mistraletti 2015). One study did not report admission diagnosis (Ibrahim 2006).

We noted length of time in ICU prior to start of trial, where reported. Bourne 2008 reported median (interquartile range (IQR)) number of days in the intervention group of 16.5 days (11.0 to 19.0) and in the control group 16.5 days (13.0 to 20.5). Ibrahim 2006 reported mean (95% CI) sedation time before start of intervention as 33 hours (17 to 49) in the intervention group and 38 hours (17 to 59) in the control group. Participants in Mistraletti 2015, were randomized on day 3. Study authors in Foreman 2015 did not report this information.

We noted that one study used a ICU sedation protocol that was not standard (Mistraletti 2015).

Interventions and comparators

All studies reported administration of melatonin in the evening to promote sleep. Doses administered were: 10 mg melatonin by enteral feeding at 9 p.m. for four consecutive nights (Bourne 2008); 3 mg melatonin by mouth or by enteral feeding at 8 p.m. for three nights up to a maximum of seven nights (Foreman 2015); 3 mg melatonin by enteral feeding through nasogastric tube at 10 p.m. for a minimum of two days or until ICU discharge (Ibrahim 2006); and 3 mg by enteral feeding at 8 p.m. and 3 mg at midnight daily until ICU discharge (Mistraletti 2015).

Three studies compared melatonin against a placebo (Bourne 2008; Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015). One study compared melatonin against usual care.

Sources of funding

One study reported no external funding (Mistraletti 2015), one study reported university and small grants funding (Bourne 2008), and two studies did not report funding sources (Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006).

Excluded studies

We excluded seven studies from assessment of the full‐texts. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Bellapart 2016 is an RCT comparing use of melatonin in critically ill patients; this pharmacokinetics study did not administer melatonin with the specific aim of promoting sleep. Huang 2015, is an RCT comparing melatonin with ear plugs and eye masks, and with a placebo; this study recruited healthy volunteers to sleep in simulated ICU environment. Two studies were non‐randomized trials; one study was a pharmacokinetics study of melatonin use (Mistraletti 2010), and one study included a control group that were not in the ICU (Shilo 2000). Three reports were incorrect study designs for our purposes: two were commentaries and one was a literature review (Elliott 2014; Morandi 2015; Owens 2016).

Awaiting classification

We identified no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

We identified five ongoing studies from clinical trial registers and database searches. Four studies compare evening administration of melatonin with a placebo (ACTRN12610000008022; Huang 2014; Martinez 2017; NCT02615340), and one study compares melatonin with lorazepam (IRCT2015082523760N1). See Characteristics of ongoing studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

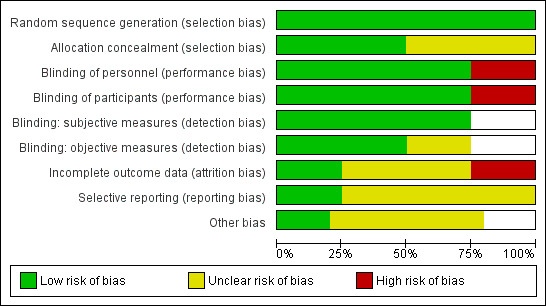

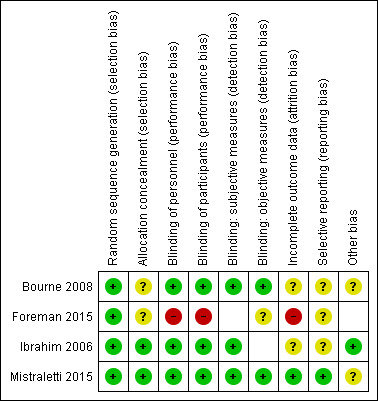

See Figure 2 and Figure 3, and Characteristics of included studies.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study. Blank spaces in figure indicate that outcomes were not reported by study authors, and therefore risk of bias was not completed for these domains.

Allocation

All studies were described as randomized, and provided sufficient details on the method of randomization (Bourne 2008; Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015); we judged these to have low risk of bias.

Two studies provided sufficient details about methods used to conceal allocation from personnel (Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015); we judged these studies to have a low risk of bias. Two studies provided no details (Bourne 2008; Foreman 2015).

Blinding

Three studies used a placebo formula in the control group (Bourne 2008; Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015). Bourne 2008 and Ibrahim 2006 reported that personnel and participants were blind to the intervention group and Mistraletti 2015 reported that personnel were blind to the intervention group; we judged these studies to be at low risk of performance bias. It was not feasible to blind personnel or participants in Foreman 2015, which compared melatonin use to usual care, and we judged this study to be at high risk of performance bias.

Three studies reported outcomes that were subjective, and assessed by personnel or participants (Bourne 2008; Ibrahim 2006; Mistraletti 2015). All studies reported blinding for outcome assessment and we judged these to have low risk of detection bias for these outcomes.

Three studies reported outcomes that were objective (Bourne 2008; Foreman 2015; Mistraletti 2015). Two studies reported blinding of personnel and we judged these to have low risk of detection bias (Bourne 2008; Mistraletti 2015). We were unable to judge risk of detection bias for objective outcomes in one study because of lack of reported information (Foreman 2015).

Incomplete outcome data

We judged one study to have low risk of attrition bias, because losses were few and were clearly reported (Mistraletti 2015). There was a large number of losses in Foreman 2015 and we judged this to have a high risk of attrition bias. We judged two studies to have unclear risk of bias because losses were unclearly reported (Bourne 2008; Ibrahim 2006).

Selective reporting

One study had prospective clinical trials registration and we judged this to have low risk of selective reporting bias (Mistraletti 2015). One study had retrospective registration with a clinical trials register, and it was not feasible to judge risk of selective reporting bias using trial registration documents (Bourne 2008); we noted an unclear risk for selective reporting bias. We were unable to source clinical trials registration documents for two studies (Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006), and it was not feasible to judge risk of bias; we noted an unclear risk of selective reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

Baseline characteristics appeared comparable and we noted no other sources of bias in one study (Ibrahim 2006). Study authors noted some differences in use of opiates between groups in one study (Mistraletti 2010); another study reported differences in some baseline characteristics (age and delirium) and we noted potential differences in ad hoc use of non‐pharmacological methods of sleep promotion (Bourne 2008); and one study was small and not clearly reported (Foreman 2015). We were unable to assess whether these studies had other sources of potential bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparison 1: melatonin versus no agent

Primary outcomes

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or family members or by personnel assessments

Three studies (139 participants) reported quantity and quality of sleep through participant and personnel assessments. Study authors reported this outcome using different assessments which were not comparable, and we could not combine data in meta‐analysis. See Table 2 for data reported by individual studies.

1. Single study outcome data: melatonin vs no agent.

| Outcome: quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants or family members or by personnel assessments | |||||

| Study | Measurement (tool) |

Data* Intervention |

Data* Control |

Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value* |

| Bourne 2008 | SEI, patient assessment (RCSQ) | mean (95% CI): 0.41 (0.24 to 0.59); n: 12 | mean (95% CI): 0.50 (0.43 to 0.58); n: 12 | −0.09 (−0.28 to 0.09) | 0.32 |

| Bourne 2008 | SEI, nurse assessment (observations) | mean (95% CI): 0.45 (0.26 to 0.64); n: 12 | mean (95% CI): 0.51 (0.35 to 0.68); n: 12 | −0.06 (CI −0.29 to 0.17) | 0.58 |

| Ibrahim 2006 | Duration of sleep, nurse assessment (observations) | median (range): 240 minutes (75 to 331.3); n: 14 | median (range): 243.4 minutes (0 to 344.1); n: 18 | not reported | 0.98 |

| Mistraletti 2015 | Duration of sleep, nurse assessment (observations) | 9 p.m. to midnight, mean (SD): 1.5 (± 1.6) hours; n: 41 midnight to 7 a.m., mean (SD): 4.5 (± 1.9) hours; n: 41 |

9 p.m. to midnight, mean (SD): 1.4 (± 1.3) hours; n: 41 midnight to 7 a.m., mean (SD): 4.3 (± 1.8) hours; n: 41 |

not reported | 0.92 0.83 |

| Outcome: quantity and quality of sleep as measured by PSG, actigraphy, BIS, or EEG | |||||

| Study | Measurement (tool) |

Data* Intervention |

Data* Control |

Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value* |

| Bourne 2008 | SEI (BIS) | Mean (95% CI): 0.39 (0.27 to 0.51); n: 12 | Mean (95% CI): 0.26 (0.17 to 0.36); n: 12 | 0.12 (CI −0.02 to 0.27) | 0.09 |

| Bourne 2008 | SEI (actigraphy) | Mean (95% CI): 0.73 (0.53 to 0.93); n: 12 | Mean (95% CI): 0.75 (0.67 to 0.83); n: 12 | −0.02 (CI −0.24 to 0.20) | 0.84 |

| Bourne 2008 | Quantity of nocturnal sleep (BIS) | Mean: 3.5 hours; n: 12 | Mean: 2.5 hours; n: 12 | Not reported | ‐ |

| Outcome: anxiety or depression, or both | |||||

| Study | Measurement (tool) |

Data* Intervention |

Data* Control |

Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value* |

| Mistraletti 2015 | Anxiety (using VNR) | Participants with score ≥ 3: 12; n: 41 | Participants with score ≥ 3: 14; n: 41 | Not reported | 0.10 |

| Outcome: mortality at 30 days | |||||

| Study | Measurement |

Data* Intervention |

Data* Control |

Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value* |

| Mistraletti 2015 | Mortality in hospital | 14; n: 41 | 15; n: 41 | Not reported | 0.82 |

| Outcome: length of stay in the ICU | |||||

| Study | Measurement |

Data* Intervention |

Data* Control |

Mean difference (95% CI)* | P value* |

| Mistraletti 2015 | ´Number of days | Median (IQR): 14 (8 to 20); n: 41 | median (IQR): 12 (9 to 29); n: 41 | Not reported | 0.75 |

* as reported by study authors

BIS: bispectral index CI: confidence interval EEG: electroencephalogram IQR: interquartile range n: number of randomized participants PSG: polysomnography RCSQ: Richards‐CampbellSleep Questionnaire SD: standard deviation SEI: sleep efficiency index TST: total sleep time VNR: verbal numeric range

Bourne 2008 reported a sleep efficiency index (SEI), which was defined as the ratio of a participant's total sleep time over the time available for night‐time sleep (9 hours, from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m.). Participants used the Richards‐Campbell Sleep Questionnaire (RCSQ) to report amount of sleep (Richards 2000), and study authors reported no difference in SEI using the RCSQ between groups according to participant sleep assessment (mean difference (MD) −0.09, 95% CI −0.28 to 0.09; P = 0.32; as reported by study authors). Similarly, study authors reported no difference in SEI between groups assessed with observation from nurses (MD −0.06, 95% CI −0.29 to 0.17; P = 0.58; as reported by study authors). We have reported mean SEI scores for each group as reported by study authors in Table 2.

Ibrahim 2006 reported duration of nocturnal sleep assessed with observation from nurses. Study authors reported similar median observed minutes of sleep between groups (P = 0.98).

Mistraletti 2015 reported duration of sleep observed during nursing shifts (from 9 p.m. to midnight, and midnight to 7 a.m.) with no difference between groups at each time point (P = 0.92, and P = 0.83, respectively).

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified few studies with few participants. We noted differences in the dose of melatonin between studies (one study gave a dose a 10 mg, one study gave a dose of 3 mg, and one study gave two separate doses of 3 mg), and study authors in two studies noted differences in baseline characteristics between groups (Bourne 2008; Mistraletti 2015). Reports were by participants and by nurse assessment, which may not be comparable. One study used an ICU sedation protocol which was not comparable to the other studies, or standard in ICU management, and may influence generalizability of this study data (Mistraletti 2015). See Table 1.

Quantity and quality of sleep as measured by PSG, actigraphy, BIS, or EEG

Two studies (37 participants) reported quantity and quality of sleep using objective tools. Assessments were not comparable and we could not combine data in meta‐analysis.

Bourne 2008 used bispectral index (BIS) and actigraphy, and reported no difference in SEI between groups (MD 0.12, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.27; P = 0.09; and MD −0.02, 95% CI −0.24 to 0.20; P = 0.84, as reported by study authors, respectively). We have reported mean SEI scores for each group as reported by study authors in Table 2.

Bourne and colleagues also reported quantity of nocturnal sleep collected with BIS: study authors noted that nocturnal sleep was one hour longer in the melatonin group and that this difference was not statistically significant (see Table 2). Study authors also reported area under the curve (AUC) for BIS, with a 7% decrease for those participants who had melatonin; study authors reported that a decrease in AUC represented "better sleep" (MD −54.23, 95% CI −104.47 to −3.98; P = 0.04).

Foreman 2015 (12 participants) collected data for total sleep time using polysomnography (PSG). Study authors reported a large loss of participant data, reporting only one participant in each group with scorable data for days one and three. Study authors do not report sleep data by group.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified few studies with few participants. We noted differences in dose of melatonin (one study gave a dose a 10 mg, and one study gave a dose of 3 mg), and study authors in one study noted differences in baseline characteristics between groups. We noted a high risk of performance bias and high attrition in one study, which prevented adequate reporting. We also noted that BIS may not be an appropriate measurement tool for sleep in the ICU, and data from BIS may be less reliable. See Table 1.

Secondary outcomes

Anxiety or depression, or both, as measured with the use of validated tools, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983)

One study reported anxiety as measured on a verbal numeric range (VNR) (Mistraletti 2015; 82 participants). Study authors reported number of participants who had anxiety (VNR ≥ 3). We noted no difference between groups in the number of participants who scored ≥ 3 on the VNR for anxiety (P = 0.10). See Table 2.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified only one study with few participants, and study authors noted differences between groups in pre‐treatment with opiates. We were not certain whether use of VNR was reliable or comparable to HADS as a tool to measure anxiety. We could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in Mistraletti 2015 were generalizable to most ICUs. See Table 1.

Mortality at 30 days

Two studies (94 participants) reported mortality (Foreman 2015; Mistraletti 2015).

Foreman 2015 reported that one‐third of participants died. We could not include this data in analysis because data were not reported by group. Study authors did not report end time point for mortality data collection and we could not be certain that it was within 30 days.

Mistraletti 2015 reported mortality in ICU, and mortality in hospital. We have reported data for mortality in hospital, although we could not be certain that it was within 30 days; study authors reported no difference between groups (P = 0.82). See Table 2.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified few studies with few participants, and we noted a high risk of performance bias and attrition in one study and differences between study groups in pre‐treatment use of opiates in another study. We could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in Mistraletti 2015 were generalizable to most ICUs. See Table 1.

Length of stay in the ICU

One study reported length of ICU stay (Mistraletti 2015; 82 randomized participants), and noted no difference between groups (P = 0.75). See Table 2.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified only one study with few participants, and study authors noted differences between groups in pre‐treatment use of opiates. We could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in Mistraletti 2015 were generalizable to most ICUs. See Table 1.

Adverse events (such as nausea, headache, or dizziness)

Two studies (107 participants) reported adverse events (Bourne 2008; Mistraletti 2015).

Bourne 2008 reported that one participant in the melatonin group had a headache which was treated effectively with acetaminophen; and Mistraletti 2015 reported that one participant in the placebo group had a cutaneous rash, and two participants (one participant in each group) had excessive sleepiness, and treatment was discontinued for these participants.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence to very low quality. We identified few studies with few participants. We noted differences in the dose of melatonin between studies and study authors noted differences between groups in baseline characteristics which could influence results. We could not be certain that ICU sedation protocols in Mistraletti 2015 were generalizable to most ICUs. See Table 1.

Subgroup analysis

We did not have sufficient studies to combine data in meta‐analysis and we did not perform subgroup analysis. We described studies according to subgroups below.

1. Severity of the health condition based on APACHE II scores (or comparable severity measures): APACHE II scores less than 25; 25 to 35; greater than 35.

Three studies reported APACHE II scores, and all mean scores were less than 25 (Bourne 2008; Foreman 2015; Ibrahim 2006). One study reported SAPS II, with a mean score (SD) of 45.7 (± 18.2) in the melatonin group and mean (SD) score of 44.1 (± 15.3) in the control (Mistraletti 2015).

2. Mechanically ventilated participants versus those not mechanically ventilated

Two studies included participants that were mechanically ventilated (Bourne 2008; Mistraletti 2015): one study included both participants that were mechanically ventilated and not mechanically ventilated (Foreman 2015); and one study included participants who were weaning from mechanical ventilation.

3. Participants 65 years of age or older versus participants younger than 65 years

No studies reported inclusion of participants who were 65 years of age or older.

4. Participants in a surgical ICU versus those in a medical ICU

One study setting was described as a neurosurgical ICU (Foreman 2015); and one study setting was described as a surgical and medical ICU (Mistraletti 2015).

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform sensitivity analysis because we did not combine data in meta‐analysis.

Comparison 2: melatonin versus another agent administered specifically to promote sleep

No studies compared melatonin with another agent.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We identified four randomized controlled trials with 151 participants. All studies compared melatonin to no agent; three studies used a placebo control; and one study compared melatonin with usual care.

Three studies assessed quantity and quality of sleep as measured through reports of participants, family members, or personnel assessments. Of these, one study reported measurements in terms of sleep efficiency index (SEI) and reported no difference between groups in SEI scores for participant assessment and for nurse assessment. Two studies reported no difference in observed sleep by nurse assessment.

Two studies assessed quantity and quality of sleep as measured by polysomnography (PSG), actigraphy, bispectral index (BIS), or electroencephalogram (EEG). Of these, one study used actigraphy and BIS and reported no difference between groups in SEI scores. This study also reported longer sleep in participants given melatonin, which was not statistically significant; and evidence of improved sleep in participants given melatonin through analysis of area under the curve of BIS data.

One study reported no difference between groups in anxiety, one study reported mortality with no difference between groups, and one study reported no difference between groups in length of ICU stay. Two studies reported data for adverse events: one study reported a headache in one participant given melatonin; and one study reported two participants with excessive sleepiness (one participant from each group) and one participant in the placebo group with a cutaneous rash.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Included studies recruited critically ill participants in the intensive care unit and administered melatonin at night‐time with the intention of promoting sleep. Baseline data suggested that participants were similar in terms of illness severity measured with APACHE II or SAPS II. However, differences in detail in study reports prevented some appropriate comparisons between study participants; for example, we were unable to report primary diagnoses, mechanical ventilation status, and length of stay in the ICU prior to start of trial, for all study participants. Whilst all patients in the ICU may be subject to sleep disturbance, other factors (such as being mechanically ventilated) may exacerbate sleep disturbance and may influence the effect of melatonin.

We noted a difference in one study, in which the ICU used a sedation protocol that differed from standard ICU sedation management. Also, we noted differences in study designs with administered dose of melatonin varying between studies from 3 mg to 10 mg. Potential differences in study populations and heterogeneity in study design compromise the generalizability and applicability of these results to the general ICU population.

Quality of the evidence

All studies reported adequate methods of randomization, and three placebo‐controlled trials had blinded participants and personnel, and had low risks of performance and detection bias. One study had compared melatonin with usual care and we judged this study to have a high risk of performance and detection bias; we also noted high attrition in this study.

We included few studies with few participants in this review. We believe that sparse data reduced precision in the effect for each of our outcomes. Differences in dose of melatonin between studies introduced inconsistency at the study design level, and difference in sedation protocols in one study introduced indirectness to the outcome data. We could not be certain whether some differences between groups at baseline level in two studies had affected results. We identified insufficient studies to allow for subgroup analysis and were unable to explore whether differences in study populations could affect response to melatonin. Similarly, because of insufficient studies, we were unable to assess the risk of publication bias in this review through generation and interpretation of a funnel plot.

We identified only two studies that used objective measurement tools to measure sleep. One of these studies used PSG, which is designed specifically to measure sleep; however, this small study reported technical difficulties and a subsequent large loss of participant data. Another study used BIS monitoring, which is typically used to measure depth of anaesthesia; it is unclear whether this is an appropriate measurement tool for sleep in the ICU.

We used the GRADE approach to downgrade the evidence for each outcome to very low quality.

Potential biases in the review process

We conducted this review using Cochrane methodology, using two authors to select studies, extract data and assess risk of bias according to our published protocol (Lewis 2016b). We conducted a thorough search that included clinical trial registers, forward and backward citation tracking, and grey literature. Also, we contacted study authors to request additional study information or information regarding potential unpublished trials.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A review that looked at the effect of melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists on sleep and delirium in the ICU concluded that the role of pharmacological agents to promote sleep for prevention of delirium remained uncertain (Mo 2016); review authors suggest that additional clinical trials are necessary. Cochrane Reviews that have looked at melatonin in other settings have reported increased length of sleep with melatonin after disruption from shift work (Liira 2014), reduction in preoperative anxiety (Hansen 2015), and reduction in, or prevention of, jet lag (Herxheimer 2002). However, these participant groups are not comparable to critically ill patients in the ICU.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found insufficient evidence to determine whether administration of melatonin would improve the quality and quantity of sleep in adult ICU patients. We also found insufficient evidence to determine whether administration of melatonin would lead to a reduction in mortality or length of stay in the ICU, or improve anxiety. Data for adverse events was limited to reports of a headache in one participant given melatonin, excessive sleepiness in two participants (one in each study group), and a cutaneous rash in one participant given a placebo agent. We identified four studies with few participants. We noted differences in study designs, and differences between intensive care unit sedation management. We did not pool data and we used the GRADE approach to downgrade the certainty of our evidence to very low.

Implications for research.

We identified five ongoing studies during database and clinical trial register searches, with a combined target recruitment of 1217 adult ICU patients. Continued research in this field demonstrates interest in establishing the effects of melatonin in this patient population. We anticipate that inclusion of data from these studies in future review updates would provide more certainty for the review outcomes.

Currently, PSG is the most appropriate objective measurement of sleep, and using this equipment would ensure consistent sleep measurement across future studies. However even PSG, which relies on measures such as EEG, may not provide reliable measurements in people who are critically ill. It is likely that studies may also include objective measures with other tools such as BIS or actigraphy; and, again, these measurement tools may not be reliable in this population group. We propose that future studies include assessment of sleep by participants when possible, as measurement of sleep quality and quantity can be subjective. We propose that outcome data are collected with objective and subjective measurements to demonstrate consistency and reliability of results. We propose that future studies are placebo‐controlled trials, which provide less risk of performance and detection bias, particularly because subjective assessment of sleep may be affected by knowledge of taking a sleep‐promoting agent.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2019 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 11, 2016 Review first published: Issue 5, 2018

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 October 2018 | Amended | Acknowledgement section amended to include Co‐ordinating Editor |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following for help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review: Nicola Petrucci (Content Editor); Marialena Trivella (Statistical Editor); Harald Herkner (Co‐ordinating Editor); Brian Gehlbach, Russel J Roberts, Gerald Weinhouse, Andrew MacDuff (Peer Reviewers); and Edward Grandi (Consumer Referee).

We would like to thank the following for help and editorial advice provided during preparation of the protocol: Nicola Petrucci (Content Editor); Asieh Golozar (Statistical Editor); and Gerald Weinhouse and Brian Gehlbach (Peer Reviewers) (Lewis 2016b).

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Care] explode all trees |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Illness] explode all trees |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Intensive Care Units] explode all trees |

| #4 | MeSH descriptor: [Respiration, Artificial] explode all trees |

| #5 | ((intensive or critical) near/3 (care or unit*)) or (critical* near/3 ill*) |

| #6 | (mechanical* near/3 ventilat*) or (artificial* near/3 respiration*) |

| #7 | #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 |

| #8 | melatonin or sleep* |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Melatonin] explode all trees |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Sleep] explode all trees |

| #11 | #8 or #9 or #10 |

| #12 | #7 and #11 |

| #13 | #12 in Trials |

Appendix 2. MEDLINE Ovid search strategy

| 1 | Critical Illness/ or Critical Care/ or exp Intensive Care Units/ or (ICU or ((intensive or critical) adj3 (care or unit*)) or (critical* adj3 ill*)).mp. or Respiration, Artificial/ or (mechanical* adj3 ventilat*).mp. or (artificial* adj3 respiration*).mp. |

| 2 | exp "Hypnotics and Sedatives"/ or Melatonin/ or sleep/ or (sleep* or hypnotic* or sedat* or melatonin).mp. |

| 3 | ((randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial).pt. or randomi*.ab. or placebo.ab. or clinical trials as topic.sh. or randomly.ab. or trial.ti.) not (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. |

| 4 | 1 and 2 and 3 |

Appendix 3. Embase Ovid search strategy

| 1 | critical illness/ or exp intensive care unit/ or exp intensive care/ or (ICU or ((intensive or critical) adj3 (care or unit*)) or (critical* adj3 ill*)).mp. or artificial ventilation/ or (mechanical* adj3 ventil*).mp. or (artificial* adj3 respiration*).mp. |

| 2 | hypnotic sedative agent/ or melatonin/ or sleep/ or (sleep* or hypnot* or sedat* or melatonin).mp. |

| 3 | ((crossover procedure or double blind procedure or single blind procedure).sh. or (crossover* or cross over*).ti,ab. or placebo*.ti,ab,sh. or (doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab. or (controlled adj3 (study or design or trial)).ti,ab. or allocat*.ti,ab. or trial*.ti,ab. or randomized controlled trial.sh. or random*.ti,ab.) not ((exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.)) |

| 4 | 1 and 2 and 3 |

Appendix 4. CINAHL EBSCO search strategy

| S1 | (MM "Critical Illness") |

| S2 | (MM "Critically Ill Patients") |

| S3 | (MH "Critical Care+") |

| S4 | (MH "Intensive Care Units+") |

| S5 | (intensive or critical) N3 (care or unit*) OR critical* N3 ill* |

| S6 | (MH "Respiration, Artificial+") |

| S7 | mechanical* N3 ventilat* OR artificial* N3 respiration* |

| S8 | (S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7) |

| S9 | (MH "Hypnotics and Sedatives+") |

| S10 | (MM "Melatonin") |

| S11 | (MH "Sleep+") |

| S12 | sleep* OR hynotic* OR sedat* OR melatonin* |

| S13 | (S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12) |

| S14 | TX allocat* random* |

| S15 | (MH "Quantitative Studies") |

| S16 | (MH "Placebos") |

| S17 | TX placebo* |

| S18 | TX random* allocat* |

| S19 | (MH "Random Assignment") |

| S20 | TX randomi* control* trial* |