Abstract

Background

There are various reasons why weaning and extubation failure occur, but ineffective cough and secretion retention can play a significant role. Cough augmentation techniques, such as lung volume recruitment or manually‐ and mechanically‐assisted cough, are used to prevent and manage respiratory complications associated with chronic conditions, particularly neuromuscular disease, and may improve short‐ and long‐term outcomes for people with acute respiratory failure. However, the role of cough augmentation to facilitate extubation and prevent post‐extubation respiratory failure is unclear.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to determine extubation success using cough augmentation techniques compared to no cough augmentation for critically‐ill adults and children with acute respiratory failure admitted to a high‐intensity care setting capable of managing mechanically‐ventilated people (such as an intensive care unit, specialized weaning centre, respiratory intermediate care unit, or high‐dependency unit).

Secondary objectives were to determine the effect of cough augmentation techniques on reintubation, weaning success, mechanical ventilation and weaning duration, length of stay (high‐intensity care setting and hospital), pneumonia, tracheostomy placement and tracheostomy decannulation, and mortality (high‐intensity care setting, hospital, and after hospital discharge). We evaluated harms associated with use of cough augmentation techniques when applied via an artificial airway (or non‐invasive mask once extubated/decannulated), including haemodynamic compromise, arrhythmias, pneumothorax, haemoptysis, and mucus plugging requiring airway change and the type of person (such as those with neuromuscular disorders or weakness and spinal cord injury) for whom these techniques may be efficacious.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 4, 2016), MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to April 2016), Embase (OvidSP) (1980 to April 2016), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1982 to April 2016), and ISI Web of Science and Conference Proceedings. We searched the PROSPERO and Joanna Briggs Institute databases, websites of relevant professional societies, and conference abstracts from five professional society annual congresses (2011 to 2015). We did not impose language or other restrictions. We performed a citation search using PubMed and examined reference lists of relevant studies and reviews. We contacted corresponding authors for details of additional published or unpublished work. We searched for unpublished studies and ongoing trials on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch) (April 2016).

Selection criteria

We included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials that evaluated cough augmentation compared to a control group without this intervention. We included non‐randomized studies for assessment of harms. We included studies of adults and of children aged four weeks or older, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation in a high‐intensity care setting.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts identified by our search methods. Two review authors independently evaluated full‐text versions, independently extracted data and assessed risks of bias.

Main results

We screened 2686 citations and included two trials enrolling 95 participants and one cohort study enrolling 17 participants. We assessed one randomized controlled trial as being at unclear risk of bias, and the other at high risk of bias; we assessed the non‐randomized study as being at high risk of bias. We were unable to pool data due to the small number of studies meeting our inclusion criteria and therefore present narrative results rather than meta‐analyses. One trial of 75 participants reported that extubation success (defined as no need for reintubation within 48 hours) was higher in the mechanical insufflation‐exsufflation (MI‐E) group (82.9% versus 52.5%, P < 0.05) (risk ratio (RR) 1.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 2.20, very low‐quality evidence). No study reported weaning success or reintubation as distinct from extubation success. One trial reported a statistically significant reduction in mechanical ventilation duration favouring MI‐E (mean difference ‐6.1 days, 95% CI ‐8.4 to ‐3.8, very low‐quality evidence). One trial reported mortality, with no participant dying in either study group. Adverse events (reported by two trials) included one participant receiving the MI‐E protocol experiencing haemodynamic compromise. Nine (22.5%) of the control group compared to two (6%) MI‐E participants experienced secretion encumbrance with severe hypoxaemia requiring reintubation (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.10). In the lung volume recruitment trial, one participant experienced an elevated blood pressure for more than 30 minutes. No participant experienced new‐onset arrhythmias, heart rate increased by more than 25%, or a pneumothorax.

For outcomes assessed using GRADE, we based our downgrading decisions on unclear risk of bias, inability to assess consistency or publication bias, and uncertainty about the estimate of effect due to the limited number of studies contributing outcome data.

Authors' conclusions

The overall quality of evidence on the efficacy of cough augmentation techniques for critically‐ill people is very low. Cough augmentation techniques when used in mechanically‐ventilated critically‐ill people appear to result in few adverse events.

Plain language summary

Promoting cough in critically‐ill adults and children to enable removal of the breathing tube (extubation) and breathing without the machine (weaning)

Background and importance

Critically‐ill adults and children who need assistance from machines (ventilators) to help them breathe may have difficulty coughing and clearing secretions. This can reduce their chances of successful removal of the breathing tube (extubation) and being able to breathe without the machine. Their respiratory muscles may be weak; they may have neuromuscular disorders, spinal cord injury, or restrictive lung disease, or be experiencing delirium, cognitive impairment or additive effects of sedation. Techniques such as building up the volume of air in the lungs over a number of breaths (breathstacking), manually‐ and mechanically‐assisted cough with an insufflation‐exsufflation (MI‐E) device can be used to encourage people to cough. The potential for these techniques to help critically‐ill adults and children to come off and stay off the ventilator is unclear.

Review question

Do techniques that promote cough in mechanically‐ventilated, critically‐ill adults and children in a high‐intensity care setting improve rates of successful extubation and weaning?

Review purpose

To look at controlled studies of techniques to promote cough in critically‐ill adults and children, to see if these techniques are useful for helping them come off and stay off the ventilator, and to determine if there are any associated harms. The complications we looked for included decreased or increased blood pressure, irregular heart rhythm, leakage of air from the lungs to the chest cavity, coughing up blood, and mucus plugging requiring a new breathing tube.

Review findings

We found two randomized controlled trials (95 adult participants) and one non‐randomized controlled study (17 children aged at least four weeks) conducted in Portugal, Canada, and the United States. We rated the two randomized trials as being of unclear quality and the non‐randomized study as being low quality. The largest randomized trial (75 participants) found a 83% success rate for extubation with mechanically‐ and manually‐assisted cough used in combination, compared with 53% in the control group (extubation success over 1½ times more likely) (very low‐quality evidence). The time spent on a ventilator was six days less in people using mechanically‐ and manually‐assisted cough (very low‐quality evidence). No participants died in this trial.

Complications were reported by the two randomized trials. One person receiving mechanically‐assisted cough experienced a prolonged drop in blood pressure; another person receiving breathstacking and suctioning in addition to manually‐assisted cough experienced a prolonged rise in blood pressure. In one trial, following removal of the breathing tube, more people in the group not receiving mechanically‐assisted cough experienced secretion retention, a drop in oxygen levels, and needed the breathing tube to be reinserted (nine people compared with two, very low‐quality evidence).

The non‐randomized study reported that the breathing tube could be removed in all of the six children in the group receiving interventions to assist with coughing. In this non‐randomized study, death was only reported for children receiving a cough‐promoting technique. One child died, but this was not thought to be related to the cough technique. This study did not report adverse events associated with assisted coughing. No included study evaluated a single cough‐promoting technique in isolation. The two randomized trials combined manually‐assisted cough with either mechanical assistance (MI‐E) or breathstacking, and the non‐randomized study used all three methods.

Conclusions

Very low‐quality evidence from single trial findings suggests that cough‐promoting techniques might increase successful removal of the breathing tube and decrease the time spent on mechanical ventilation, while not causing harm. The limited participant numbers made it difficult to determine the likelihood of harms.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Summary of findings for the main comparison: cough augmentation techniques versus no cough augmentation technique.

| Cough augmentation techniques compared with no cough augmentation techniques for critically‐ill, mechanically‐ventilated adults and children | ||||||

|

Patient or population: critically‐ill mechanically‐ventilated adults and children requiring extubation from mechanical ventilation Settings: High acuity setting including ICUs, weaning centres, respiratory intermediate care units, and high‐dependency units in Europe and North America Intervention: Cough augmentation techniques including lung volume recruitment, manually‐assisted cough and mechanical insufflation‐exsufflation Comparison: No cough augmentation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| No cough augmentation | Cough augmentation | |||||

| Extubation successa | 87% | 83% | RR 1.58 (1.13 to 2.20) | 75 participants 1 trial | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Duration of mechanical ventilationb | 4 days | 11.7 days | Mean difference ‐6.1 days (‐8.4 to ‐3.8) | 75 participants 1 trial | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| ICU mortalitya | 28% | 0% | Not calculable, as no event rates in the 1 trial reporting data on this outcome | 75 participants 1 trial | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Adverse events 1. Hypotensionc 2. Hypertensiond 3. Secretion encumbrance resulting in severe hypoxaemia requiring reintubationc |

12% 6.5% 9% |

3% 10% 6% |

RR 3.4 (0.1 to 81.3) RR 3.0 (0.1 to 65.9) RR 0.25 (0.1 to 1.1) |

75 participants

1 trial 20 participants 1 trial 75 participants 1 trial |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio aAssumed risk is derived from a large international cohort study of mechanical ventilation and weaning by Esteban 2013 and refers to the rate of reintubation reported in this study. bAssumed risk is derived from a large international cohort study of mechanical ventilation and weaning by Esteban 2008. cAssumed risk is derived from adverse events (hypotension and hypoxaemia) reported in a systematic review of recruitment manoeuvres in people with acute lung injury (Fan 2008). dAssumed risk is derived from rates of hypertension noted during 6691 episodes of endotracheal suctioning (Evans 2014). | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1We based our downgrading decisions from high to very low on unclear risk of bias, inability to assess consistency or publication bias, and uncertainty about the estimate of effect due to the limited number of studies contributing outcome data.

2We based our downgrading decisions from high to very low on unclear risk of bias, inability to assess consistency or publication bias, imprecision due to wide confidence intervals, and uncertainty about the estimate of effect due to the limited number of studies contributing outcome data.

We have not included reintubation or weaning success in the 'Summary of findings' table as no studies reported these outcomes.

Background

Description of the condition

Critically‐ill people receiving mechanical ventilation, via endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, may experience impaired airway clearance during intubation and once extubated due to ineffective cough, respiratory muscle weakness, or paralysis associated with intensive care unit‐acquired weakness (ICUAW), neuromuscular disorders, spinal cord injury, and restrictive lung disease (Gonçalves 2012; Salam 2004; Smina 2003). ICUAW is a common complication of critical illness, affecting limb and respiratory muscles, and is associated with weaning failure (Hermans 2014). Critically‐ill people with pre‐existing neuromuscular disease have ineffective peak cough flows, resulting in an inability to cough (Bach 2010). Additional reasons for ineffective cough include the cumulative effects of sedation and lack of patient co‐operation or effort (Smina 2003) due to delirium or cognitive impairment, both of which are prevalent in the critically‐ill population (Ouimet 2007; Pandharipande 2013). Moreover, effective cough requires closure of the glottis, which is prevented during endotracheal intubation, or by glottic muscle weakness (Smina 2003). Ineffective cough leads to secretion pooling, atelectasis and respiratory tract infection, which may cause weaning failure and the need for reintubation (Gonçalves 2012; Salam 2004; Smina 2003). Suctioning of the trachea via the endotracheal tube, a standard airway intervention in the intensive care unit (ICU), may also impair mucociliary function, and is ineffective for clearing the peripheral airways (Nakagawa 2005), further contributing to secretion pooling.

Description of the intervention

Cough augmentation techniques comprise lung volume recruitment, (also termed airstacking or breathstacking), manually‐assisted cough, and mechanically‐assisted cough using a mechanical insufflation‐exsufflation (MI‐E) device. During lung volume recruitment, the person inhales a volume of gas via the ventilator, or self‐inflating resuscitation bag adapted with a one‐way valve to facilitate gas holding. The person retains the inhaled volume by closing the glottis, inhales another volume of gas and then again closes the glottis; this process is repeated until maximum insufflation capacity is reached (Toussaint 2009). Lung volume recruitment can be performed in isolation or in combination with manually‐assisted cough. Manually‐assisted cough consists of a cough timed with an abdominal thrust or lateral costal compression once maximal air‐stacking is achieved and timed to glottic opening (Bach 2012). MI‐E devices such as the CoughAssist™ (Philips Respironics Corp, Millersville, PA) or the NIPPY Clearway (B&D Electromedical, Stratford‐Upon‐Avon, Warwickshire) alternate the delivery of positive (inflation) and negative pressures (rapid deflation) delivered to the person via an oronasal interface, mouthpiece, or endotracheal or tracheostomy tube (Bach 2013). MI‐E comprises a pressure‐targeted lung insufflation followed by vacuum exsufflation, enabling lung emptying and increasing peak cough flow. Alternation of pressure may be manually or automatically cycled. Pressures of 40 mmHg (insufflation) to –40 mmHg (exsufflation) (54 cmH2O) are usually most effective and best tolerated by the person (Bach 2014). In non‐critically‐ill people, few complications associated with barotrauma have been reported, most likely due to use of pressures that are much lower than physiological cough pressures and the short duration of application (Gómez‐Merino 2002). Due to pressure drop‐off and reduced peak expiratory flows, when applying MI‐E via an endotracheal or tracheostomy tube, the cuff should remain inflated and pressures of 38 mmHg to 51 mmHg (50 cm H2O to 70 cm H2O) can be used, depending on the person's tolerance (Bach 2014; Guérin 2011).The duration of insufflation and exsufflation should enable maximum chest expansion and rapid lung emptying, with two to four seconds used for adults (Bach 2010) and shorter durations for children (Chen 2014). Treatments usually comprise three to five insufflation‐exsufflation cycles followed by a short period of rest to avoid hyperventilation (Bach 2012). Treatments can be repeated until no further secretions are expectorated. MI‐E can be performed in isolation or in combination with manually‐assisted cough.

How the intervention might work

The increased lung volumes generated via lung volume recruitment increase elastic recoil, thereby increasing peak cough flow and promoting sputum expectoration (Kang 2000). Manually‐assisted cough further enhances peak cough flow, particularly for people with weak expiratory muscles (Kirby 1966). MI‐E has been shown to produce a higher peak cough flow when compared with manual techniques (Bach 1993). Additionally, routine suctioning does not reach the left main‐stem bronchus approximately 90% of the time (Fishburn 1990), whereas MI‐E provides the same exsufflation flows in left and right airways, enabling more effective secretion clearance (Garstang 2000). Many primarily observational studies over the last two decades suggest that cough augmentation techniques are safe and efficacious in managing exacerbation of respiratory failure due to infection in people with neuromuscular disease or spinal cord injury in the community or a long‐term care setting (Bach 1993; Kang 2000; Kirby 1966).

Why it is important to do this review

There are various reasons why weaning and extubation failure occur, but ineffective cough and secretion retention can play a significant role (Perren 2013). Cough augmentation techniques have been used extensively to prevent and manage respiratory complications associated with chronic conditions, particularly neuromuscular disease, and may improve short‐ and long‐term outcomes for hospitalized people experiencing acute respiratory failure. At present, the role of cough augmentation is unclear for critically‐ill people with acute respiratory failure requiring intubation and for management of post‐extubation respiratory failure.

Serious physiological sequelae are associated with mechanical ventilation, necessitating efficient processes to safely prevent, reduce, and remove invasive ventilator support. Assessment of readiness for removal is generally undertaken using a spontaneous breathing trial. Approximately 30% of people will fail this spontaneous breathing trial and present a greater weaning challenge (Scheinhorn 2001), experience additional complications related to prolonged mechanical ventilation, and presenting a significant cost burden to the healthcare system (Carson 2006; Iregui 2002). These people commonly experience secretion accumulation due to ineffective cough and altered mucociliary clearance, contributing to weaning failure (Gonçalves 2012; Salam 2004; Smina 2003). For them, cough augmentation techniques may promote weaning success and prevent reintubation and tracheostomy (Bach 2004; Bach 2010; Chatwin 2003; Gonçalves 2012; Sancho 2003). Prevention of extubation failure is important, as it is associated with increased duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU and hospital length of stay, nosocomial pneumonia, and mortality (Gowardman 2006; Savi 2012).

Objectives

Our primary objective was to determine extubation success using cough augmentation techniques compared to no cough augmentation for critically‐ill adults and children with acute respiratory failure admitted to a high‐intensity care setting capable of caring for mechanically‐ventilated people (such as an intensive care unit, specialized weaning centre, respiratory intermediate care unit, or high‐dependency unit).

Secondary objectives were to determine the following:

1. The effect of cough augmentation techniques on reintubation; weaning success; mechanical ventilation and weaning duration; length of stay (high‐intensity care setting and hospital); pneumonia; tracheostomy placement and tracheostomy decannulation; and mortality (high‐intensity care setting, hospital, and after hospital discharge).

2. The harms associated with use of cough augmentation techniques when applied via an artificial airway (or non‐invasive mask once extubated/decannulated), including haemodynamic compromise, arrhythmias, pneumothorax, haemoptysis, and mucus plugging requiring change airway change.

3. The type of person (such as those with neuromuscular disorders or weakness and spinal cord injury) for whom these techniques may be efficacious.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials that evaluated cough augmentation techniques (lung volume recruitment, manually‐assisted cough and mechanical insufflation‐exsufflation (MI‐E)) compared to a control group without this intervention. We excluded randomized cross‐over studies* as this design does not allow determination of the efficacy of the intervention on clinical outcomes such as weaning success. We included non‐randomized studies with a non‐exposed control group* (non‐randomized controlled trials, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies and case‐control studies), to assess harms associated with cough augmentation techniques.

Types of participants

We included studies of adults and of children aged four weeks or more, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, and admitted to a high‐intensity care setting such as an ICU, specialized weaning centre, respiratory intermediate care unit or high‐dependency unit. We included all high‐intensity care setting patient populations, including those admitted for medical, surgical and trauma diagnoses.

We excluded studies of cough augmentation techniques administered in the home, community, or long‐term care settings.

Types of interventions

Cough augmentation techniques included in this systematic review comprised lung volume recruitment, also termed airstacking or breathstacking as described above, manually‐assisted cough, and mechanically‐assisted cough using a MI‐E device. Lung volume recruitment and MI‐E may be used in isolation or in combination with manually‐assisted cough. We included studies of cough augmentation techniques used before or after extubation.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcome was extubation success. Extubation success may be variably defined by study authors (Boles 2007); however, we defined it as no further requirement for invasive mechanical ventilation for a minimum of 24 hours. As non‐invasive ventilation may be used as a strategy to facilitate extubation (Bach 2010) in individuals with reduced ventilatory capacity, we did not consider its use within the 24 hours following extubation to constitute extubation failure.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

reintubation;

weaning success, defined as no further requirement for invasive or non‐invasive ventilation for a minimum of 24 hours;

duration of mechanical ventilation and weaning*;

rates of tracheostomy placement and tracheostomy decannulation*;

length of stay*;

mortality; and

harm.

Potential harms included haemodynamic compromise (as defined by study authors), arrhythmias, pneumothorax, haemoptysis, and mucus plugging requiring change of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube associated with cough augmentation techniques.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Two review authors (LR and DM) searched indexed literature from database inception to April 2016. Electronic databases searched included MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to April 2016), Embase (OvidSP) (1980 to April 2016), CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1982 to April 2016), and ISI Web of Science and Conference Proceedings. We searched the Cochrane Library (Issue 4, 2016) which includes the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA Database) and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED). Other systematic review databases that we searched included PROSPERO and the Joanna Briggs Institute. We refined the search strategies with the research team, and had them peer‐reviewed according to the PRESS guidelines (McGowan 2010) before formally executing them. We developed our search for MEDLINE and adapted the strategy to other databases. (See Appendix 1 for the search strategies). Where applicable, we removed animal‐only studies and opinion pieces (e.g. editorials, letters). We did not impose language or other restrictions. As we included non‐randomized studies, we did not apply a filter for randomized controlled trials.

Searching other resources

We searched websites of relevant professional societies and handsearched conference abstracts from annual congresses from the previous five years (2011 to 2015) of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, American and Canadian Thoracic Societies, European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, and International Symposium on Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. We selected this five‐year time frame as it enabled identification of studies that may not be published in full text. We performed a citation search using PubMed. We examined reference lists of relevant studies and reviews and contacted corresponding authors of included studies for details of additional published or unpublished work. We searched for unpublished studies and ongoing trials on the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (apps.who.int/trialsearch) (April 2016).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (LR and DM) independently screened titles and abstracts of electronic and manual search results against eligibility criteria (Appendix 2) (Stage 1). We retrieved and examined full‐text publications of all potentially relevant articles for eligibility (Stage 2). We resolved any disagreements though discussion, and sought an additional opinion from an independent arbiter (NA) to reach consensus. We used the Cochrane checklist for assessment of non‐randomized studies to categorize study design (Higgins 2011). We have noted the details and reasons for study exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (DL and LR) independently extracted data from selected studies on key components, including features of study characteristics, study design, participant characteristics, study outcomes, complications, and adverse events, using a modified version of the Cochrane Anaesthesia, Critical and Emergency (ACE) Care Group data extraction form (Appendix 3), iteratively refined based on piloting of the form. For non‐randomized studies where available we extracted data on confounding factors, methods used to control confounding, and multiple effects estimates. We referred to a third author (NA) as required to check extraction, confirm decisions and resolve disagreement.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

DL and LR independently critically appraised included papers for quality. We assessed study quality of randomized controlled trials using the domain‐based evaluation process recommended by Cochrane (Higgins 2011). These domains include:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding;

incomplete outcome data;

selective reporting; and

other bias.

For each domain, we assigned a judgement of the risk of bias as 'high risk of bias', ‘low risk of bias’, or ‘unclear risk of bias’ (Higgins 2011). We contacted the corresponding author of studies for clarification when insufficient detail was reported to assess the risk of bias. A priori, we anticipated that no eligible trials would be blinded to the use of cough augmentation techniques and that non‐blinding of personnel and participants would not necessarily be considered high risk of bias when considering objective outcomes. Once we achieved consensus on the quality assessment of the six domains for eligible studies, we assigned them to the following categories.

Low risk of bias: describes studies for which all domains are scored as ‘low risk of bias’

High risk of bias: one or more domains scored as 'high risk of bias'*

Unclear risk of bias: one or more domains scored as 'unclear' and no domains scored as 'high'*

(* See Differences between protocol and review)

For non‐randomized studies (as in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011)), we generated an a priori list of potential confounding factors, identified confounders considered and omitted, assessed balance between comparator groups, and identified how selection bias was managed. For quality assessment of non‐randomized studies we used the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) checklists (SIGN 2014) (Appendix 4) for cohort and case‐control studies, as recommended by the Quality Assessment Tools Project Report (Bai 2012). We constructed a ‘Risk of bias’ table in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2014) to present the results. We planned to use the assessment of risk of bias to perform sensitivity analyses based on methodological quality, but we identified too few studies.

Measures of treatment effect

We express findings for binary outcomes in terms of risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and continuous outcomes in terms of mean differences (MDs) and associated 95% CIs. For observational studies we planned to report unadjusted and adjusted effect sizes (odds ratios (ORs) for dichotomous outcomes and MDs (or regression coefficients) for continuous outcomes), but these data were unavailable.

Unit of analysis issues

We used individual study participants as the unit of analysis. We anticipated that all included trials would be of a parallel‐group design and therefore did not expect to make adjustments for clustering. If we identified multi‐arm studies, we planned to combine groups to create a single pair‐wise comparison, as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). If combining groups was not possible or feasible, we planned to select only one treatment and control group from each study.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted study authors to request additional information or missing data. We sent a maximum of three emails to corresponding authors. We had planned to exclude participants with missing data when calculating the risk ratio of a trial (complete‐case analysis) for dichotomous outcome data, but found too few studies to perform these analyses.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We found too few studies to evaluate clinical and methodological heterogeneity using forest plots of trial‐level effects, and the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011), or using qualitative assessment of clinical heterogeneity by examining potential sources, such as the type of cough augmentation strategy in each trial and the type of participants enrolled.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to construct a funnel plot of the treatment effect for the primary outcome against trial precision (standard error). However, we did not find enough studies to create a funnel plot or to formally test for asymmetry (Egger 1997; Peters 2006).

Data synthesis

We summarized search results in a PRISMA study flow diagram (Moher 2009). We summarized study characteristics using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations or medians and interquartile ranges for continuous variables, depending on data distribution. We planned separate analyses of randomized and observational studies, but we identified too few studies to perform meta‐analyses and therefore completed only a descriptive qualitative synthesis. If we find additional trials when we update the review, we will calculate pooled RRs with 95% CIs using a random‐effects model for binary outcomes, allowing for adjustments that incorporate variation both within and between studies (DeMets 1987). For continuous variables we will calculate a pooled difference of means with 95% CIs using a random‐effects model. We will consider a two‐sided P value < 0.05 to be significant. We planned to log‐transform continuous skewed data, but did not perform this analysis as only one study reported each of our continuous outcomes of interest.

For assessment of harms we planned to create a binary variable (harm present: yes/no) and to categorize studies accordingly. We planned to use the Peto odds ratio (Yusuf 1985) if harm outcomes were rare and treatment groups were well‐balanced, but identified too few studies to perform this analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not identify enough studies to perform subgroup analyses of adult versus paediatric populations, the cough augmentation technique used, study location (ICU versus specialized weaning or other acute‐care location), and study population (mixed; neuromuscular disease, weakness or spinal cord injury; and single‐lung ventilation).

Sensitivity analysis

We did not identify enough studies to conduct a sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome, excluding trials with a high risk of bias.

'Summary of findings' table and GRADE

We used the GRADE approach (Guyatt 2008) to assess the evidence quality associated with our specific outcomes (extubation success; reintubation; weaning success, duration of mechanical ventilation; mortality and harms (adverse events)) and constructed a 'Summary of findings' table using RevMan 2014. The GRADE approach appraises the quality of a body of evidence based on the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association reflects the item being assessed. The quality of a body of evidence takes into consideration within‐study risk of bias (methodological quality), the directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias.

Results

Description of studies

We identified two eligible randomized controlled trials (Crowe 2006; Gonçalves 2012), and one non‐randomized study (Niranjan 1998), with intervention arms that comprised MI‐E delivered in combination with manually‐assisted cough, or lung volume recruitment in combination with manually‐assisted cough. The control groups of included studies comprised usual care, including standard respiratory physiotherapy.

Results of the search

Our search of electronic sources described above identified 2686 citations: 2640 from electronic databases and 46 from trial registration and systematic review databases. Authors of studies included in the review or content experts provided no additional citations.

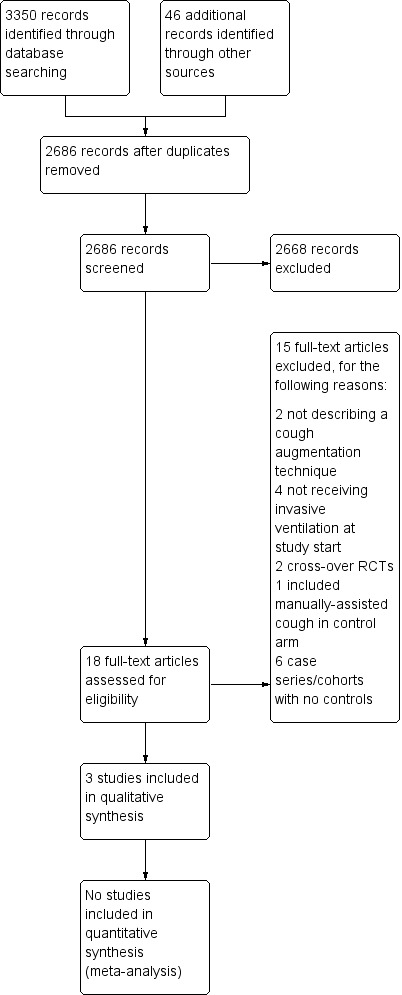

After checking the citation titles and abstracts retrieved from the electronic databases, we retrieved 18 articles to review in full text. We excluded 15 other studies as they did not meet our inclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included two randomized controlled trials and one cohort study, covering 112 participants in all (see Characteristics of included studies). Study sample sizes ranged from 17 to 75. Studies were conducted in Canada (Crowe 2006), Portugal (Gonçalves 2012), and the United States (Niranjan 1998).

Study participants

The two randomized controlled trials recruited mechanically‐ventilated adults experiencing acute respiratory failure of mixed aetiology admitted to an ICU (Gonçalves 2012; Crowe 2006). The cohort study recruited children with neuromuscular ventilatory failure admitted to a paediatric ICU, unable to sustain ventilator‐free breathing (Niranjan 1998).

Study interventions

We included one trial (Gonçalves 2012) of MI‐E combined with manually‐assisted cough begun before extubation and after successfully passing a spontaneous breathing trial. Eight cycles of MI‐E were administered using inspiratory and expiratory pressures of 40 cm H2O in each treatment. Participants received three daily treatments for the 48 hours after extubation. The second included trial (Crowe 2006) evaluated lung volume recruitment (breathstacking) using a resuscitation bag equipped with a one‐way valve to manually inflate to maximal insufflation capacity. Lung volume recruitment consisted of three stacked breaths to achieve 40 cm H2O by the third breath, followed by a 10‐second breath hold. At the end of the 10 seconds, the participant was disconnected from the lung volume recruitment bag and a manually‐assisted cough was performed. Each session comprised four cycles of three stacked breaths (12 stacked breaths in total), repeated twice daily until extubated, 72 hours after randomization, or six treatment sessions. The included cohort study (Niranjan 1998) used a protocol involving breathstacking to maximum inspiratory capacity whenever the participant's SaO2 dropped below 95%. Breathstacking was followed by either manually‐assisted cough or MI‐E using inspiratory and expiratory pressures of 35 to 45 cm H2O. This procedure was repeated until sputum was expectorated and the SaO2 returned to baseline.

Excluded studies

We excluded 15 studies (Avena 2008; Bach 1996; Bach 2010; Bach 2015; Beuret 2014; Chen 2014; Duff 2007; Jeong 2015; Ntoumenopulos 2014; Porto 2014; Torres‐Castro 2014; Toussaint 2003; Velasco Arnaiz 2011; Vianello 2005; Vianello 2011). (see Characteristics of excluded studies). Six were non‐randomized studies without a control group (Avena 2008; Bach 1996; Bach 2010; Bach 2015; Ntoumenopulos 2014; Velasco Arnaiz 2011). Four studies recruited participants who were not using invasive ventilatory support at study start or actively excluded ventilated people; cough augmentation techniques were used to improve lung function and to prevent intubation as opposed to facilitating weaning and preventing reintubation (Chen 2014; Jeong 2015; Torres‐Castro 2014; Vianello 2005). Two studies involved an intervention that did not comprise a cough augmentation technique (Beuret 2014; Duff 2007), two studies used a cross‐over randomized controlled design (Porto 2014; Toussaint 2003), and one study used manually‐assisted cough in the control arm (Vianello 2011).

Awaiting classification

There are no studies awaiting classification.

Ongoing studies

A search of the trial registration database found no ongoing studies that met our inclusion criteria.

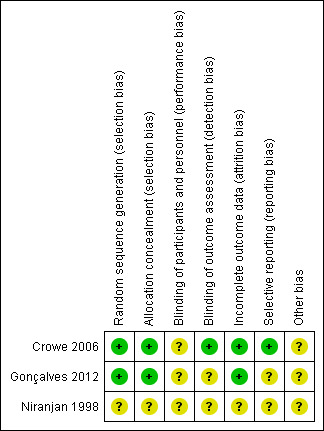

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risks of bias for the two included randomized controlled trials, using Cochrane's domain‐based 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2011), and the single cohort study using the appropriate SIGN checklist (SIGN 2014). We provide our judgement of classification of bias for the two randomized controlled trials in Characteristics of included studies section, with a summary presented in Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Both trials (Crowe 2006; Gonçalves 2012) used a computer‐generated table for random sequence generation. Both studies used adequate measures for allocation concealment.

Blinding

As anticipated, neither trial blinded study personnel or participants to the intervention. Lack of blinding may have influenced clinician decision‐making on if and when to reintubate a participant reporting extubation success and the need for reintubation (Gonçalves 2012), resulting in unclear performance bias. In Crowe 2006 the radiologist assessing the chest radiograph and applying the atelectasis score (primary outcome) was blinded to allocation. In Gonçalves 2012, we were unable to determine if assessors were blinded and we therefore rated risk of detection bias as unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

We did not detect evidence of attrition bias in the two randomized controlled trials.

Selective reporting

We identified a trial protocol registered by Gonçalves 2012, but this protocol was registered after study completion and we therefore rated the risk of reporting bias as unclear. We did not locate a trial registration by Crowe 2006, but the outcomes reported matched the primary and secondary objectives described, and we considered them appropriate for trials of this intervention

Other potential sources of bias

In Gonçalves 2012, two authors received funding from Philips Respironics Inc., who manufactured the MI‐E device used in the trial. We were unable to ascertain if this company had any role in providing funding or support for the trial and therefore assessed the risk of bias from other potential sources as unclear. Crowe 2006 was forced to stop early, reaching only half of the target sample size due to failure to recruit participants. We therefore rated the risk of bias from other potential sources as unclear

Risk of bias in the included non‐randomized study

Using the appropriate SIGN checklist (SIGN 2014), we assessed the single cohort study (Niranjan 1998) as follows:

Selection of participants

It was unclear if participants were taken from comparable populations or whether selection criteria were differentially applied.

Assessment

We found outcome definitions to be unclear. There was no evidence that outcome assessment was blinded to exposure, or recognition that knowledge of exposure status could have influenced outcome assessment. However, end points were mostly objective in nature and likely not susceptible to bias.

Confounding

We found no evidence that the main potential confounders were identified and taken into account in the design and analysis of the study. Overall we rated the risk of bias as high, with no clear evidence of an association between exposure and outcome.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See (Table 1)

Primary outcome: extubation success

Data on this outcome were available in one trial of 75 participants (Gonçalves 2012) and one non‐randomized study (Niranjan 1998) of 17 children. Gonçalves 2012 defined extubation success as no requirement for reintubation within 48 hours of extubation. Participants could receive non‐invasive ventilation during this 48‐hour period and still be classified as an extubation success. Niranjan 1998 defined extubation success as no requirement for reintubation before ICU discharge. Children were extubated to continuous non‐invasive intermittent positive pressure ventilation and use of non‐invasive ventilation did not preclude definition of extubation success. Gonçalves 2012 reported a statistically significant difference in extubation success rates favouring the MI‐E protocol (82.9% versus 52.5%, P < 0.05) (risk ratio (RR) 1.58, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 2.20, very low‐quality evidence) (Table 2). The non‐randomized study (Niranjan 1998) reported that all of the six intubated children meeting the inclusion criteria were successfully extubated. However, all children in the control group received a tracheostomy, as this was the standard care procedure at that time, making comparison problematic. For this reason, we retained only the trial of 75 participants (Gonçalves 2012) for rating the quality of evidence for this outcome. We downgraded the evidence rating from high quality to very low quality, due to unclear risk of bias, inability to assess consistency or publication bias, and uncertainty about the estimate of effect due to the limited number of studies contributing outcome data.

1. Table of secondary outcomes.

| Cough augmentation | No cough augmentation | |||||

| Study | N | mean (SD) | N | mean (SD) | mean difference | 95% CIs |

| Duration of mechanical ventilation (days) | ||||||

| Gonçalves 2012 | 35 | 11.7 (3.5) | 40 | 17.8 (6.4) | ‐6.1 | ‐8.4 to ‐3.8 |

| ICU length of stay (days)1 | ||||||

| Gonçalves 2012 | 35 | 16.9 (11.1) | 40 | 19.3 (8.1) | ‐2.4 | ‐6.9 to 2.01 |

| Niranjan 1998 | 10 | 47.6 (7.3) | 7 | 51.1 (7.8) | ‐3.5 | ‐10.8 to 3.8 |

1The ICU length of stay for cases reported in Niranjan 1998 includes the four cases that were not intubated at the start of the study.

Secondary outcomes

No study reported reintubation rates other than those used to define extubation success, or reported weaning success as an outcome distinct from extubation success. One study (Gonçalves 2012) reported the duration of mechanical ventilation with a statistically significant reduction favouring the MI‐E protocol (mean difference (MD) ‐6.1 days, 95% CI ‐8.4 to ‐3.8, very low‐quality of evidence). No study reported the duration of weaning. Two studies reported on ICU length of stay (Gonçalves 2012; Niranjan 1998). Gonçalves 2012 reported a statistically non‐significant mean difference in ICU length of stay (‐2.4 days, 95% CI ‐6.85 to 2.05, very low‐quality evidence). Niranjan 1998 reported a statistically non‐significant mean difference in ICU length of stay (‐3.5 days, 95% CI ‐10.84 to 3.84) (Table 2), but this analysis included four children in the intervention arm who received cough augmentation techniques to prevent intubation, as opposed to the six children that received cough augmentation techniques to prevent reintubation. Only one trial (Gonçalves 2012) reported on ICU mortality in the 48 hours following extubation, with no participant in either group dying within this time frame (very low‐quality evidence). Niranjan 1998 reported mortality in the follow‐up period after hospital discharge but only for those receiving the intervention, making comparison problematic. Of the six children that were ventilated at study entry, one died six months after ICU discharge (Table 2). We downgraded the evidence rating from high quality to very low quality for these secondary outcomes, for the same reasons as listed for the primary outcome. No studies reported on pneumonia, tracheostomy, or tracheostomy decannulation.

Adverse events

Two studies (Crowe 2006; Gonçalves 2012) reported on adverse events (Table 3). Crowe 2006 reported that one participant in the breathstacking protocol experienced an episode of coughing during suctioning, with the participant's blood pressure remaining elevated to a maximum of 190 mmHg for more than 30 minutes. No participant in either study group experienced new‐onset arrhythmias, more than a 25% increase in heart rate, or developed a pneumothorax. Gonçalves 2012 reported that one participant receiving the MI‐E protocol compared to no participants in the control group experienced haemodynamic compromise, defined as systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mmHg for more than 30 minutes. Nine (22.5%) of the control group compared to two (6%) participants receiving the MI‐E protocol experienced secretion encumbrance associated with severe hypoxaemia, warranting reintubation (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.10, very low‐quality evidence). Niranjan 1998 did not report adverse events associated with the study intervention.

2. Adverse effects.

| Cough augmentation | No cough augmentation | |||||

| Study | Events | Total | Events | Total | RR | 95% CIs |

| Haemodynamic compromise | ||||||

| Gonçalves 2012 | 1 | 35 | 0 | 40 | 3.4 | 0.1 to 81.3 |

| Crowe 2006 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 3.0 | 0.1 to 65.9 |

| Secretion encumbrance resulting in severe hypoxaemia requiring reintubation | ||||||

| Gonçalves 2012 | 2 | 35 | 9 | 40 | 0.25 | 0.1 to 1.1 |

Type of participants

Due to the small number of included studies with most outcomes of interest only reported in a single study, we are unable to determine the type of patients for whom these techniques are most likely to be efficacious.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Because we only found three small studies, including two randomized controlled trials, with reporting of most outcomes of interest in a single study, and very low quality of evidence, we have not found sufficient evidence to suggest that cough augmentation techniques influence extubation and weaning success or reduce the time spent on a ventilator. Adverse events associated with cough augmentation techniques and deaths were uncommon, but limited study and participant numbers make it difficult to determine the likelihood of harms associated with the treatment.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Both randomized controlled trials (Crowe 2006; Gonçalves 2012) included a heterogeneous population of adults, meaning the study findings may be applicable to the patient populations found in most mixed ICU environments. The non‐randomized study (Niranjan 1998) included children with known neuromuscular disease, and is of limited relevance because of the lack of reporting of some outcomes for the historical controls. The largest trial (Gonçalves 2012) excluded participants with neuromuscular disease, as these patients who are ventilator‐dependent are unable to produce effective cough flows without assistance. Two large case series that we excluded due to the absence of a control group report extubation success rates in 157 (Bach 2010) and 98 (Bach 2015) participants with neuromuscular disease or weakness and vital capacities less than 20% of normal. In these case series, cough augmentation techniques (lung volume recruitment, manually‐assisted cough, and MI‐E) were used before and after extubation to continuous non‐invasive ventilation using assist/volume control mode. Extubation success rates, defined as no requirement for reintubation during hospitalization, were 95% and 91% respectively. Therefore, although randomized controlled trials are lacking in the acutely‐ and critically‐ill neuromuscular patient population, some evidence suggests these techniques are efficacious.

We can draw no conclusions as to which cough augmentation technique may demonstrate benefit or result in harm, as no included study evaluated a single cough augmentation technique in isolation. The two randomized trials (Crowe 2006; Gonçalves 2012) both combined manually‐assisted cough with either MI‐E or lung volume recruitment, while the non‐randomized study used all three methods.Neither can we draw any conclusions on the most efficacious method of using the individual cough augmentation techniques. For example, both MI‐E and lung volume recruitment treatments can be administered at variable intervals throughout a 24‐hour period. These treatments can comprise a variable number of cycles, and MI‐E can be delivered at a range of pressures.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence for our outcomes of interest was very low, due to the methodological limitations of the included studies and lack of data, with only one trial contributing to our outcomes of interest. Evidence quality from the larger randomized controlled trial (Gonçalves 2012) was unclear, because of a lack of blinding of clinical staff due to the nature of the intervention and the potential for performance bias, particularly as reintubation was at the discretion of the attending physician who was not blinded to study allocation. There was also unclear risk for selective reporting due to publication of the trial registration after completion of participant enrolment, and an unclear relationship of the device manufacturer to the study. Due to early discontinuation of the smaller randomized controlled trial (Crowe 2006), we considered risk of other bias as unclear. The non‐randomized study (Niranjan 1998) had low strength of evidence, as we were unable to tell if participants in the intervention and non‐intervention groups were taken from the same population, and there was no evidence that the main potential confounders had been identified and accounted for. In all three studies, the nature of the intervention meant blinding of clinicians involved in the delivery of cough augmentation techniques was not feasible.

Potential biases in the review process

We believe the potential for bias in our review process is low. We adhered to the procedures outlined by Cochrane (Higgins 2011), as described in our review protocol (Rose 2015), including independent screening for trial inclusion, data extraction, and assessment of risk of bias by two review authors. We have made some small modifications to the review from the original protocol (See Differences between protocol and review), but we do not believe these modifications introduced bias into the review process. We made no assumptions about intensity of treatment that may influence findings, and made no decisions about analyses or investigation of heterogeneity after seeing the data. We believe we have identified all relevant studies through the use of a comprehensive search strategy, developed in consultation with a senior Information Specialist and peer‐reviewed according to the PRESS guidelines (McGowan 2010), in combination with a review of trial databases, conference abstracts, and reference lists of relevant literature, as well as contact with experts.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first published systematic review of studies comparing cough augmentation techniques with usual care without cough augmentation for extubation and weaning of critically‐ill people. A previous systematic review of MI‐E for people with neuromuscular disease and not experiencing critical illness reported no serious adverse events attributed to MI‐E in the five studies that met their inclusion criteria, but the authors noted that it was unclear if adverse events were systematically investigated (Morrow 2013).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We were unable to find enough evidence to determine the effects of cough augmentation techniques on extubation and weaning success, ventilation and weaning duration, rates of tracheostomy and tracheostomy decannulation, length of stay, and mortality for critically‐ill, mechanically‐ventilated people. Very low‐quality evidence suggests cough augmentation techniques might improve extubation success and decrease the duration of mechanical ventilation while not increasing harm.

Implications for research.

Due to the overall rating of very low‐quality evidence arising from the small number of trials with few participants and unclear risk of bias, further studies of cough augmentation techniques in the critically ill are warranted. Studies are required to determine which type of critically‐ill people may benefit or be at risk of harm from cough augmentation techniques. Adequately‐powered, multicentre randomized controlled trials are needed not only comparing cough augmentation techniques to weaning and extubation practices that do not include cough augmentation techniques, but also head‐to‐head comparisons of the techniques themselves, and the intensity of the intervention. Such trials should incorporate measurement of peak cough flow before and after delivery of the intervention. Studies are also needed to evaluate the most efficacious pressures to generate cough and facilitate secretion expectoration in the critically ill. Outcomes such as weaning, extubation success and mechanical ventilation duration are confounded by other unit practices such as the use of weaning protocols and other weaning tools, pain and sedation management, as well as the structure and organization of the ICU. Future trials should consider whether these co‐interventions should be protocolized within the trial design, or at least ensure that a detailed description of usual care is documented.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 January 2019 | Amended | Editorial team changed to Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 8, 2015 Review first published: Issue 1, 2017

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 February 2017 | Amended | Acknowledgement section corrected |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Rodrigo Cavallazzi (content editor), Cathal Walsh (statistical editor), Antonio M Esquinas, John R Bach, Yuka Ishikawa (peer reviewers), Janet Wale (consumer editor) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the systematic review.

We would also like to acknowledge our Information Specialist Becky Skidmore for her invaluable assistance generating our search strategies, as well as Rodrigo Cavallazzi (content editor), Harald Herkner (statistical editor), Thomas Bongers, Yuka Ishikawa, and John Bach (peer reviewers) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol (Rose 2015), for the systematic review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

Cough Augmentation

Ovid MEDLINE(R) In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE(R)

1 (cough* adj2 assist*).tw.

2 (CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine*).mp.

3 (cough* adj2 augment*).tw.

4 Cough/rh [Rehabilitation]

5 ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations").tw.

6 (insufflat* adj1 exsufflat*).tw.

7 "MI‐E".ti,ab.

8 (breathstack* or breath‐stack*).tw.

9 (airstack* or air‐stack*).tw.

10 (direct* adj2 cough*).tw.

11 ((glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) adj2 (breath* or respirat*)).tw.

12 (cough* adj2 flow* adj5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*)).tw.

13 (respiratory muscle* adj2 (aid* or support*)).tw.

14 (recruit* adj2 ("lung volume" or aveolar)).tw.

15 ((lung or alveolar) adj1 recruit* adj2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*)).kw,tw.

16 or/1‐15

17 exp Animals/ not (exp Animals/ and Humans/)

18 16 not 17

19 (comment or editorial or letter or interview or news).pt.

20 (letter not (letter and randomized controlled trial)).pt.

21 18 not (19 or 20)

Embase Classic+Embase

1 (cough* adj2 assist*).tw.

2 (CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine*).tw,dv.

3 (cough* adj2 augment*).tw.

4 exp coughing/rh [Rehabilitation]

5 ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations").tw.

6 (insufflat* adj1 exsufflat*).tw.

7 "MI‐E".ti,ab.

8 (breathstack* or breath‐stack*).tw.

9 (airstack* or air‐stack*).tw.

10 (direct* adj2 cough*).tw.

11 ((glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) adj2 (breath* or respirat*)).tw.

12 (cough* adj2 flow* adj5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*)).tw.

13 (respiratory muscle* adj2 (aid* or support*)).tw.

14 lung volume recruitment/

15 lung volume recruitment maneuver/

16 (recruit* adj2 ("lung volume" or aveolar)).tw.

17 or/11‐16

18 ((lung or alveolar) adj1 recruit* adj2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*)).kw,tw.

19. or/1‐19

20 exp animal experimentation/ or exp models animal/ or exp animal experiment/ or nonhuman/ or exp vertebrate/

21 exp humans/ or exp human experimentation/ or exp human experiment/

22 20 not 21

23 19 not 22

24 letter.pt.

25 randomized controlled trial/

26 24 not (24 and 25)

26 editorial.pt.

27. 23 not (25 or 26)

CINAHL

1. TI cough* N2 assist* OR AB cough* N2 assist*

2. TI ( CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine* ) OR AB ( CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine* )

3. TI cough* N2 augment* OR AB cough* N2 augment*

4. (MH "Cough/RH")

5. TI ( ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations" ) OR AB ( ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations" )

6. TI insufflat* N1 exsufflat* OR AB insufflat* N1 exsufflat*

7. TI "MI‐E" OR AB "MI‐E"

8. TI ( breathstack* or breath‐stack* ) OR AB ( breathstack* or breath‐stack* )

9. TI ( airstack* or air‐stack* ) OR AB ( airstack* or air‐stack* )

10. TI direct* N2 cough* OR AB direct* N2 cough*

11. TI ( (glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) N2 (breath* or respirat*) ) OR AB ( (glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) N2 (breath* or respirat*) )

12. TI ( cough* N2 flow* N5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*) ) OR AB ( cough* N2 flow* N5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*) )

13. TI ( respiratory muscle* N2 (aid* or support*) ) OR AB ( respiratory muscle* N2 (aid* or support*) )

14. TI ( recruit* N2 ("lung volume" or alveolar) ) OR AB ( recruit* N2 ("lung volume" or alveolar) )

15. TI ( (lung or alveolar) N1 recruit* N2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*) ) OR AB ( (lung or alveolar) N1 recruit* N2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*) )

16. S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15

17. PT comment or editorial or letter or news

18. S16 NOT S17 (Expanders)

19. S16 NOT S17 (Limiters)

Web of Science

1. TS=(cough* NEAR/2 assist*)

2. TS=(CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine*)

3. TS=(cough* NEAR/2 augment*)

4. TS=("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations")

5. TS=(insufflat* NEAR/1 exsufflat*)

6. TS="MI‐E"

7. TS=(breathstack* or breath‐stack*)

8. TS=(airstack* or air‐stack*)

9. TS=(direct* NEAR/2 cough*)

10. TS=((glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) NEAR/2 (breath* or respirat*))

11. TS=(cough* NEAR/2 flow* NEAR/5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*))

12. TS=(("respiratory muscle" or "respiratory muscles") NEAR/2 (aid* or support*))

13. TS=(recruit* NEAR/2 ("lung volume" or alveolar))

14. TS=((lung or alveolar) near/1 recruit* near/2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*))

15. #14 OR #13 OR #12 OR #11 OR #10 OR #9 OR #8 OR #7 OR #6 OR #5 OR #4 OR #3 OR #2 OR #1

CENTRAL, DARE, HTA Database, NHS EED

1. (cough* near/2 assist*):ti,ab,kw

2. CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator or Cof‐flator* or (cough next machine*)

3. (cough* near/2 augment*):ti,ab,kw

4. [mh Cough/rh]

5. ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations"):ti,ab,kw

6. (insufflat* near/1 exsufflat*):ti,ab,kw

7. "MI‐E":ti,ab,kw

8. (breathstack* or (breath next stack*)):ti,ab,kw

9. (airstack* or (air next stack*)):ti,ab,kw

10. (direct* near/2 cough*):ti,ab,kw

11. ((glossopharyngeal or "glosso‐pharyngeal") near/2 (breath* or respirat*)):ti,ab,kw

12. (cough* near/2 flow* near/5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*)):ti,ab,kw

13. ((respiratory next muscle*) near/2 (aid* or support*)):ti,ab,kw

14. (recruit* near/2 ("lung volume" or alveolar)):ti,ab,kw

15. ((lung or alveolar) near/1 recruit* near/2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*)):ti,ab,kw

16. {or #1‐#15}

PROSPERO

1. "in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations"‐ all fields

2. CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine*, cough* AND augment*, insufflat*, exsufflat*, inexsufflat* or in‐exsufflat*, MI‐E, breathstack*, breath‐stack*, airstack*, air‐stack*, direct* AND cough*, (glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) AND (breath* or respiratory), respiratory muscle, respiratory muscles; lung volume, lung recruitment, alveolar AND recruit*, lung AND recruit* ‐ all fields

3. cough* ‐ all fields

The Joanna Briggs Institute EBP Database

1 (cough* adj2 assist*).tx.

2 (CoughAssist* or Pegaso* or Cofflator* or Cof‐flator* or cough machine*).af.

3 (cough* adj2 augment*).tx.

4 ("in‐exsufflator" or "in‐exsufflators" or "in‐exsufflation" or "in‐exsufflations").tx.

5 (insufflat* adj1 exsufflat*).tx.

6 "MI‐E".tx.

7 (breathstack* or breath‐stack*).tx.

8 (airstack* or air‐stack*).tx.

9 (direct* adj2 cough*).tx.

10 ((glossopharyngeal or glosso‐pharyngeal) adj2 (breath* or respirat*)).tx.

11 (cough* adj2 flow* adj5 (improv* or increas* or enhanc* or expan* or exten*)).tx.

12 (respiratory muscle* adj2 (aid* or support*)).tx.

13 (recruit* adj2 ("lung volume" or alveolar)).tx.

14 ((lung or alveolar) adj1 recruit* adj2 (manoeuv* or maneuv*)).tx.

15 or/1‐14

Appendix 2. Screening tool

| Study Endnote ID: | 1st Author, year: | |||||

| Level of Review | Title and Abstract | Full‐text | ||||

| Elements | Inclusion | Exclusion | ||||

| Study design | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) Quasi‐RCT/controlled clinical trial Observational design with comparison/control Uncertain – obtain full‐text |

Case series Case reports |

||||

| Population | Adult or child over the age of 4 weeks Invasive mechanical ventilation Admitted to a high intensity care setting such as an ICU, specialized weaning centre, or high dependency unit Uncertain – obtain full‐text |

Home, community, and long‐term care settings | ||||

| Intervention | LVR alone LVR with MAC MAC alone MI‐E alone MI‐E with MAC Uncertain – obtain full‐text |

|||||

| Comparison/controls | No cough augmentation Uncertain – obtain full‐text |

|||||

| Outcome(s) | Weaning success Reintubation Duration of mechanical ventilation and weaning; ICU and hospital length of stay New tracheostomy insertion Decannulation Harms associated with cough augmentation |

|||||

| Decision | Reason for Exclusion | |||||

| INCLUDE EXCLUDE UNSURE – further discussion needed |

Design Comparison/Controls Population Outcome(s) Intervention |

|||||

| Comments | ||||||

| Decision based on: | Abstract only | Abstract and full‐text | ||||

Appendix 3. Data extraction tool

|

Data Abstraction Form Please record any missing information as unclear or not described, to make it clear that the information was not found in the study report(s), not that you forgot to extract it | |||||

| Reviewer Initials | Review Date | ||||

| Primary author | Year | ||||

| Confirm study eligibility | Yes | No | If No, list reason for exclusion on screening tool | ||

| Study Design | Simple RCT | Quasi‐RCT | Non‐randomized controlled trial | ||

| Randomized cross‐over study | Prospective cohort study | Retrospective cohort study | |||

| Case‐control study | Other design (please describe) | ||||

| Unit of allocation | Individual | Cluster | |||

| Setting | Participating site country(ies): | ||||

| Single | Multi‐site | Academic hospital | |||

| Non‐teaching hospital | Not reported | ||||

| Mixed ICU | MICU | SICU | |||

| Other | |||||

| Participant inclusion criteria (please list): | |||||

| Exclusion criteria (please list): | |||||

| Population description (from which study participants are drawn): | |||||

| General Notes: | |||||

| PARTICIPANTS | |||||

| INTERVENTION | CONTROL | ||||

| Total N randomized | Total N randomized | ||||

| Total N of population at start of study for non‐randomized | Total N of population at start of study for non‐randomized | ||||

| Withdrawals | Withdrawals | ||||

| Exclusions | Exclusions | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | Age, mean (SD) | ||||

| Male n (%) | Male n (%) | ||||

| Reasons for ICU admission or mechanical ventilation (list all) | Reasons for ICU admission or mechanical ventilation (list all) | ||||

| Severity of illness measure used | Severity of illness measure used | ||||

| Severity of illness score mean (SD) | Severity of illness score mean (SD) | ||||

| Subgroups measured | Subgroups measured | ||||

| INTERVENTION | |||||

| Describe cough augmentation intervention (please describe verbatim including method and settings used, frequency and timing, who delivered the intervention) | |||||

| Describe additional ventilation and weaning methods as well as description of other standard medical therapy and relevant co‐interventions outlined in the paper (verbatim) | |||||

| CONTROL | |||||

| Describe ventilation and weaning methods used for control group as well as description of other standard medical therapy and relevant co‐interventions outlined in the paper (verbatim) | |||||

| OUTCOMES | |||||

| PLEASE RECORD UNIT of MEASUREMENT for ALL OUTCOMES (days/hours) | |||||

| INTERVENTION (n = ) | CONTROL (n = ) | ||||

| Weaning Success (verbatim description of how defined) | |||||

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | ||||

| Reintubation (verbatim description of how defined) | |||||

| n/N (%) | n/N (%) | ||||

| Duration of weaning (describe how defined i.e. when weaning starts and stops) | |||||

| n/N (%) weaned mean (SD) median (IQR) |

n/N (%) weaned mean (SD) median (IQR) |

||||

| Duration of ventilation (describe how defined i.e. when ventilation starts and stops) | |||||

| n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

||||

| ICU length of stay | |||||

| n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

||||

| Hospital length of stay | |||||

| n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

n/N (%) mean (SD) median (IQR) |

||||

| Mortality n/N (%) ICU 28/30 day 60 day 90 day Hospital |

Mortality n/N (%) ICU 28/30 day 60 day 90 day Hospital |

||||

| New tracheostomy, n/N (%) | New tracheostomy, n/N (%) | ||||

| Decannulation, n/N (%) | Decannulation, n/N (%) | ||||

| Haemodynamic compromise, n/N (%) | Haemodynamic compromise, n/N (%) | ||||

| Arrhythmias, n/N (%) | Arrhythmias, n/N (%) | ||||

| Pneumothorax, n/N (%) | Pneumothorax, n/N (%) | ||||

| Haemoptysis, n/N (%) | Haemoptysis, n/N (%) | ||||

| Mucous plugging, n/N (%) | Mucous plugging, n/N (%) | ||||

| CONCLUSIONS | |||||

| Key Conclusions made by authors | |||||

| PERSONAL COMMUNICATION | |||||

| List any personal communication with authors & corresponding dates | |||||

| RISK OF BIAS ASSESSMENT FOR RCTS and Quasi‐RCTS | |||||

| Domain | Description (verbatim) | Judgement | |||

| Sequence generation Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Allocation concealment Was allocation adequately concealed? |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Blinding (participants/personnel) Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Blinding (outcome assessment) Was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study? |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Incomplete outcome data Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? State whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers in each intervention group (compared with total randomized participants), reasons |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Selective outcome reporting Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting? |

Low High Unclear |

||||

| Other sources of bias Role of , possible conflicts of interest for study authors |

Low High Unclear |

||||

Appendix 4. 'Risk of bias' Assessment: Non‐Randomized Studies

| SIGN: Checklist: Cohort studies | |||||||

| Section 1: INTERNAL VALIDITY | |||||||

| In a well conducted cohort study: | Does this study do it? | ||||||

| 1.1 | The study addresses an appropriate and clearly focused question1 | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| SELECTION OF STUDIES | |||||||

| 1.2 | The two groups being studied are selected from source populations that are comparable in all respects other than the factor under investigation2 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| 1.3 | The study indicates how many of the people asked to take part did so, in each of the groups being studied3 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| 1.4 | The likelihood that some eligible subjects might have the outcome at the time of enrolment is assessed and taken into account in the analysis4 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| 1.5 | What percentage of individuals or clusters recruited into each arm of the study dropped out before the study was completed5 | ||||||

| 1.6 | Comparison is made between full participants and those lost to follow‐up, by exposure status6 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| ASSESSMENT | |||||||

| 1.7 | The outcomes are clearly defined7 | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| 1.8 | The assessment of outcome is made blind to exposure status. If the study is retrospective this may not be applicable8 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| 1.9 | Where blinding was not possible, there is some recognition that knowledge of exposure status could have influenced the assessment of outcome9 | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| 1.10 | The method of assessment of exposure is reliable10 | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| 1.11 | Evidence from other sources is used to demonstrate that the method of outcome assessment is valid and reliable11 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| 1.12 | Exposure level or prognostic factor is assessed more than once12 | Yes No Unclear Does not apply |

|||||

| CONFOUNDING | |||||||

| 1.13 | The main potential confounders are identified and taken into account in the design and analysis13 | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| STATISTICAL ANALYSIS | |||||||

| 1.14 | Have confidence intervals been provided?14 | Yes | No | ||||

| Section 2: OVERALL ASSESSMENT OF THE STUDY | |||||||

| 2.1 | How well did the study minimize the risk of bias or confounding?15 | High quality (++) Acceptable (+) Unacceptable – reject 0 |

|||||

| 2.2 | Taking into account clinical considerations, your evaluation of the methodology used, and the statistical power of the study, do you think there is clear evidence of an association between exposure and outcome? | Yes No Unclear |

|||||

| 2.3 | Are the results of this study directly applicable to the patient group targeted in this guideline? | Yes | No | ||||

| 2.4 | Notes. Summarize the authors’ conclusions. Add any comments on your own assessment of the study, and the extent to which it answers your question and mention any areas of uncertainty raised above | ||||||

1 Unless a clear and well defined question is specified in the report of the review, it will be difficult to assess how well it has met its objectives or how relevant it is to the question you are trying to answer on the basis of the conclusions.

2 This relates to selection bias.* It is important that the two groups selected for comparison are as similar as possible in all characteristics except for their exposure status, or the presence of specific prognostic factors or prognostic markers relevant to the study in question.

3 This relates to selection bias.* The participation rate is defined as the number of study participants divided by the number of eligible subjects, and should be calculated separately for each branch of the study. A large difference in participation rate between the two arms of the study indicates that a significant degree of selection bias* may be present, and the study results should be treated with considerable caution.

4 If some of the eligible subjects, particularly those in the unexposed group, already have the outcome at the start of the trial the final result will be subject to performance bias.* A well conducted study will attempt to estimate the likelihood of this occurring, and take it into account in the analysis through the use of sensitivity studies or other methods.

5 This question relates to the risk of attrition bias.*The number of patients that drop out of a study should give concern if the number is very high. Conventionally, a 20% dropout rate is regarded as acceptable, but in observational studies conducted over a lengthy period of time a higher dropout rate is to be expected. A decision on whether to downgrade or reject a study because of a high dropout rate is a matter of judgement based on the reasons why people dropped out, and whether dropout rates were comparable in the exposed and unexposed groups. Reporting of efforts to follow up participants that dropped out may be regarded as an indicator of a well conducted study.

6 For valid study results, it is essential that the study participants are truly representative of the source population. It is always possible that participants who dropped out of the study will differ in some significant way from those who remained part of the study throughout. A well conducted study will attempt to identify any such differences between full and partial participants in both the exposed and unexposed groups. This relates to the risk of attrition bias.* Any unexplained differences should lead to the study results being treated with caution.