Editor’s Note

The study of subjective experience represents a significant challenge to cognitive scientists, but one that is beginning to be increasingly addressed. Subjectivity renders experience less amenable to traditional objective scientific measurements than other subject matter. Our authors believe that when seeking to understand the mind, subjectivity must ultimately be investigated and understood.

Ancient Greek philosophers were fond of the aphorism, “know thyself,” inscribed above the entrance of one of the Temples of Apollo at Delphi. One expression of this tradition, variably attributed to Socrates and Plato, is that “the unexamined life is not worth living.” Another, attributed to Aristotle, is “to know thyself is the beginning of wisdom.” And, according to Socrates, the path to such self-knowledge is through inner reflection, or what we now call introspection.

Thousands of years later, professions arose to help people know themselves better. Sigmund Freud, for example, introduced his method of psychoanalysis in the early 20th Century as a means of helping people cope with hysteria and other neuroses by bringing unconscious conflicts into conscious awareness, allowing troubling memories that had been repressed to be worked through.1 Although he was neither a psychiatrist nor a psychologist, Freud’s ideas greatly influenced the way people with mental health problems were treated for decades. His emphasis on making the unconscious conscious was retained by some who followed,2,3 while others emphasized the conscious self in the here and now.4 Regardless, subjective experience played a key role in treatment.

It is ironic that this emphasis on subjective experience in psychological treatment gained traction and flourished at roughly the same time that behaviorists were exorcising subjective experiences from mainstream psychological research.5 Conversely, just as the influence of behaviorism was receding in the 1960s, treatment approaches that de-emphasized subjective experience came into existence.

For example, based on the conditioning methods developed by the behaviorists, so-called behavior therapy emerged in the late 1950s.6,7 The assumption underlying this approach was that subjective experience is only a crude reflection of adjustment problems, which are better addressed by changing the way people behave when interacting with their environment. With adequate behavioral change, in this view, subjective state problems will simply dissipate. Later, cognitive change was added, giving rise to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).8 While CBT largely replaced the pure behavioral approach, it did not traditionally emphasize subjective experience9, though this is changing.10,11

The Impact of Pharmaceuticals

The medical or pharmaceutical approach, which preceded behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapies, treated mental health problems as medical problems.12 The patient’s subjective experience was recorded at intake, and used as the starting point, but the “disease” was then treated by medications that attempted to address the root cause by correcting chemical or circuit imbalances in the brain. The search for new drugs generally involved testing animals in challenging situations,13–15 on the assumption that medications that make animals less behaviorally timid, for example, should make people less fearful or anxious. Thus, as with the behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches, the underlying belief was that subjective experiences will be automatically corrected once something else—here, the chemical or circuit imbalance—is addressed.

Few would claim that these efforts have solved the problem of treating mental health maladies. Under the best of conditions, behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, and pharmaceutical treatments currently available for anxiety and mood disorders are more effective than placebo, but not by nearly as much as is needed.16–21 In this regard, the effort to discover new medications is informative.

Early findings suggested that benzodiazepines can sometimes help with anxiety, and medications that alter monoamines could help with depression and anxiety. This stimulated a massive research effort to find improved treatments. However, decades later, the conclusion is that few new classes of medications have demonstrated clinical efficacy.15,22–25 Concluding that the probability of future success is low, pharmaceutical companies have begun to reduce support for research on new medications to treat anxiety and depression.25

Noting a crisis in the advancement of treatment options, the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) re-evaluated the approach to treatment, proposing that diagnostic categories (anxiety, depression, schizophrenia) be replaced with empirically-based, neurally-inspired dimensions (threat processing, avoidance, memory, cognitive control, subjective experience) that cut across diagnoses.26 But the value of this controversial move remains unclear, and under new leadership, NIMH is taking a wait-and-see approach to this change.27

Considering Different Therapies

Behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, and pharmaceutical approaches have all traditionally assumed that successful treatment must go beyond, or beneath, subjective experience—that the way to improve mental health is to change problematic behavior or the information-processing functions and/or brain physiology underlying it. Reflecting this view, insurance companies today are more likely to refer to “behavioral health” than “mental health.” But perhaps this assumption, which equates the behavioral with the mental, needs to be reconsidered.

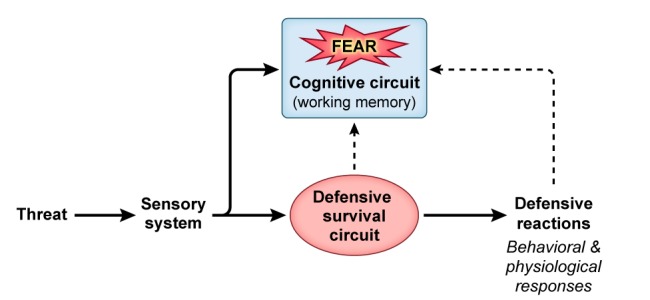

We have proposed that a key problem in the treatment of adjustment issues related to fear and anxiety is the scientific conception that underlies our understanding of these feelings.11,28,29 Since Charles Darwin, human emotions have been viewed as “states of mind” inherited from animal ancestors.30 As evidence, Darwin used similarities between the behaviors of animals and humans in situations in which humans typically report feeling fear or other emotions. Following Darwin’s lead, neuroscience researchers have assumed that studies of animal behavior can reveal the circuits of human emotions.31–33 For example, a common view today is that fear is a product of an ancient innate brain circuit shared amongst mammals.34–38 Typically, the amygdala is said to be the core of this “fear circuit.” When a threat activates the amygdala, a fear state occurs, characterized by certain behavioral and physiological responses. Therefore, treatments that change this circuit should reduce the behavioral and physiological responses, as well as the fear or anxiety.38,39

Suppose that the assumption that conscious feelings and behavioral and physiological responses elicited by threats are entwined in subcortical circuits such as the amygdala is incorrect. That this might be the case is indicated by several observations.11,29,40 First, behavioral and physiological indicators do not always correlate well with subjective experiences of fear or anxiety, as they should if they are all products of the same circuit. Moreover, existing treatments do not equally affect objective responses and subjective experiences of fear or anxiety. Additionally, damage to the amygdala, the centerpiece of the so-called fear circuit, does not necessarily eliminate the ability to feel fearful or anxious. Also, it is possible, using subliminal stimulation, to activate the amygdala and elicit physiological responses to threats, without the person knowing a threat is present and without reporting that he or she feels fearful.

For these reasons, the idea that the subjective experience of fear is a hard-wired state inherited from animals is not universally accepted by psychologists41–45 or neuroscientists.28,46,47 How, then, might fear come about if not via an ancient subcortical circuit? It seems worth considering the possibility that it arises the same way as other kinds of conscious experiences.40

Consciousness Enters the Equation

Little was known about consciousness when brain-centered studies of fear and anxiety began several decades ago, in part because subjective experience was viewed as a quasi-scientific notion unworthy of serious research. But this is no longer the case. Despite its dubious reputation in corners of the field that have a lingering connection to behaviorism, research on consciousness is thriving in both psychology and neuroscience.48–61

The current wave of research on consciousness began in the 1960s and 70s with results from studies of neurological patients, including people with split-brains (a procedure to alleviate epileptic seizures),62,63 amnesia,64–66 and blindsight (a condition in which the sufferer responds to visual stimuli without consciously perceiving them).67,68 Research on each of these groups showed powerful and compelling dissociations between information processing that controls behaviors non-consciously, and the processing that underlies conscious experience.

A major theme in the research on the topic of consciousness today is the identification of neural circuits that make possible the inner awareness of mental states.52–54,69–75 This effort is premised on the assumption that conscious states result from the elaboration of nonconscious information processing. In this research, conscious experience is most commonly studied through self-report. While self-report, like subjective experience itself, has a reputation of being soft and un-scientific, we believe this view is misinformed. It can be an invaluable research tool,76,77 at its best when used to assess immediate experience, and less useful as time goes by (memory can change, and even be reconsolidated at retrieval). Self-report is also poor as a means for uncovering why someone did something, as motivations often affect behavior non-consciously. Various methods have arisen to improve on subjective reporting.78–81 But overall, self-report measures hold up well, and are the foundation of modern studies of conscious experience.82

Such research has been especially successful in using functional brain imaging to identify circuits that transform non-conscious information, as represented by sensory processing circuits, into conscious experiences.52–54,69–75 This work has shown that when people are consciously aware of a visual stimulus, the visual cortex is activated but so too are areas of the prefrontal and parietal cortex that have been implicated in working memory. From this work has arisen the basic idea that the brain has a variety of specialized processing modules that operate non-consciously, and that consciousness occurs when information they provide is captured by attention and brought into neural circuits that support higher-cortical functions.

While most of the work on consciousness has focused on perception, it has been proposed that emotional feelings work the same way.40 The key idea here is that both emotional and non-emotional states of consciousness depend on the same basic fronto-parietal cognitive circuit, but in emotional experiences, the circuitry processes additional kinds of input.

If this view is correct, it would go a long way towards explaining why treatments based on findings from animal behavior are not more effective in helping people feel better. In targeting subcortical behavioral control circuits, such treatments inadequately change subjective experience. Subjective experience, in other words, is not just another symptom that will also go away when you change the circuit that controls behavior. The subjective experience circuit itself has to be changed.

Some suggest that this view dismisses the contribution of animal research.38,39 This, however, is a mischaracterization. We have noted in our publications that changing behavioral or physiological symptoms on the basis of treatments developed through animal research is extremely useful.11,28,29 Animal research is especially helpful for understanding and treating symptoms arising from circuits that are conserved between humans and animals that control behavioral and physiological responses, (for example, subcortical circuits involving the amygdala). It is less helpful in understanding functions of circuits conserved to a lesser degree (i.e., fronto-parietal circuits), since such circuits have unique cellular features in humans83–86 and support cognitive capacities that differ dramatically between humans and other animals.87–94

Some of the limitations of existing behavioral, cognitive, and pharmaceutical treatments may be due to a misunderstanding what the treatments are actually doing. If we are right, truly successful mental health treatment might require us to view that affliction arises from a federation of systems that generate different symptoms and require different approaches. Thus, treating a behavioral control circuit alone will not necessarily ameliorate pathological feelings of fear or dread; but it might well tone down the intensity of such states. Similarly, treating subjective experience alone may not be sufficient. Although the involved systems have fundamentally different functions, they are highly interactive, and each must be addressed.

We and others propose that subjective experience is a cognitively constructed event.11,28, 29, 40, 43–47, 100 The construction process draws upon one’s cultural milieu, social situation, and memories of and concepts about danger, all in the context of the physiological state of the brain and body. If so, then changing the hard-wired circuit will only be partially helpful. The subjective state itself also has to be a focus of treatment.

Our emphasis on subjective experience, some recent commentators have said, threatens to send psychiatry back to a dark time when subjective states were its focus.38,39 But this critique overlooks the fact that subjective experience, as noted above, is no longer viewed as taboo, qausi-scientific topic. Research on consciousness is in fact thriving in psychology and brain science. The critique also overlooks the success of mindfulness-based approaches, which emphasize subjective experience and awareness, in the treatment of mental health problems.10,95–99

The science of subjective experience has come a long way in recent years. While it is still about turning the mind in on itself, a rigorous body of scientific research on consciousness is emerging. Applied to clinical problems, modern understanding of consciousness could pave the way for more precise and valid assessments of human emotions and provide clinicians with new and improved strategies for treating emotional suffering.

Footnotes

Joseph LeDoux, Ph.D., is the Henry and Lucy Moses Professor of Science at NYU in the Center for Neural Science, and he directs the Emotional Brain Institute of NYU and the Nathan Kline Institute. He also a Professor of Psychiatry and Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical School. His work is focused on the brain mechanisms of memory and emotion and he is the author of The Emotional Brain, Synaptic Self, and Anxious. LeDoux is an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He has received the William James Award from the Association for Psychological Science, the Karl Spencer Lashley Award from the American Philosophical Society, the Fyssen International Prize in Cognitive Science, Jean Louis Signoret Prize of the IPSEN Foundation, the Santiago Grisolia Prize, the American Psychological Association Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and the American Psychological Association Donald O. Hebb Award. His book Anxious received the 2016 William James Book Award from the American Psychological Association. He is also the lead singer and songwriter in the rock band, The Amygdaloids and performs with Colin Dempsey as the acoustic duo So We Are.

Richard Brown, Ph.D., is a professor in the philosophy program and an adjunct professor in the psychology program at LaGuardia Community College. He is also a member of the NYU Project on Space, Time, and Consciousness, which is sponsored by the NYU Global Institute for Advanced Studies. He earned his Ph.D. in philosophy with a concentration in cognitive science from the CUNY Graduate Center in 2008. His work is focused on the philosophy of mind, consciousness studies, and the foundations of cognitive science.

Daniel S. Pine, M.D. is Chief, Section on Development and Affective Neuroscience in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Intramural Research Program. After graduating from medical school at the University of Chicago, Pine spent 10 years in training and research on child psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. Since medical school, he has been engaged continuously in research focusing on the epidemiology, biology, and treatment of pediatric mental illnesses. His areas of expertise include biological and pharmacological aspects of mood, anxiety, and behavioral disorders in children, as well as classification of psychopathology across the lifespan. Pine has served as the chair of the psychopharmacologic drug advisory committee for the Food and Drug Administration and chair of the Child and Adolescent Diagnosis Group for the DSM-5 Task Force. He has received the Joel Elkes Award from the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, the Blanche Ittelson Award from the American Psychiatric Association, and the Ruane Prize from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation.

Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D., is director of the Psychotherapy and Emotion Research Laboratory at Boston University. His research focuses on the mechanism of treatment change, translating discoveries from neuroscience into clinical applications, emotions, and cultural expressions of psychopathology. He is former president of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies, and the International Association for Cognitive Psychotherapy. He is also editor-in-chief of Cognitive Therapy and Research and is associate editor of the Clinical Psychological Science. His scientific work has been supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and various private foundations. He has published more than 300 scientific papers and 15 books. He also works as a psychotherapist using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

References

- 1.Freud S. Introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. H. Heller; 1917. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sullivan HS. The Interpersonal Theory of Psychiatry: A systemic presentation of the later thinking of one of the great leaders in modern psychiatry. W. W. Norton & Company; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Horney K. Neurosis and Human Growth: The struggle toward self-realization. W. W. Norton & Company; 1950. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rogers CR. Client-Centered Therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Constable & Robinson; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson JB. Behaviorism. WW Norton; 1925. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bandura A. Principles of behavior modification. Holt; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolpe J. Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. (Stanford University Press; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck AT. Cognitive Therapy: Nature and Relation to Behavior Therapy. Behavior Therapy. 1970;1:184–200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hofmann SG, Asmundson GJ, Beck AT. The science of cognitive therapy. Behav Ther. 2013;44:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hofmann SG, Gomez AF. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Anxiety and Depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40:739–749. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeDoux JE, Hofmann SG. The subjective experience of emotion: A fearful view. Curr Opin Behav Sci. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. Wolters Kluwer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray JA. The Neuropsychology of Anxiety. (Oxford University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belzung C, Lemoine M. Criteria of validity for animal models of psychiatric disorders: focus on anxiety disorders and depression. Biology of mood & anxiety disorders. 2011;1:9. doi: 10.1186/2045-5380-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griebel G, Holmes A. 50 years of hurdles and hope in anxiolytic drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2013;12:667–687. doi: 10.1038/nrd4075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barth J, et al. Comparative efficacy of seven psychotherapeutic interventions for patients with depression: a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001454. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bech P. Is the antidepressive effect of second-generation antidepressants a myth? Psychol Med. 2010;40:181–186. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beck AT. The current state of cognitive therapy: a 40-year retrospective. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:953–959. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandelow B, et al. Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:183–192. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M, Huibers MJ. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:245–258. doi: 10.1002/wps.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Korte KJ, Smits JA. Is it Beneficial to Add Pharmacotherapy to Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy when Treating Anxiety Disorders? A Meta-Analytic Review. Int J Cogn Ther. 2009;2:160–175. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.2.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hyman SE. Psychiatric drug development: diagnosing a crisis. Cerebrum. 2013;2013;5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hyman SE. Revolution stalled. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003142. 155cm111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature neuroscience. 2010;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller G. Is pharma running out of brainy ideas? Science. 2010;329:502–504. doi: 10.1126/science.329.5991.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Insel T, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon J.The Future of RDoC, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/about/director/messages/2017/the-future-of-rdoc.shtml/index.shtml, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 28.LeDoux JE. Anxious: Using the brain to understand and treat fear and anxiety. Viking; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 29.LeDoux JE, Pine DS. Using Neuroscience to Help Understand Fear and Anxiety: A Two-System Framework. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:1083–1093. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16030353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darwin C. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. Fontana Press: 1872. [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacLean PD. Some psychiatric implications of physiological studies on frontotemporal portion of limbic system (visceral brain) Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1952;4:407–418. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(52)90073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacLean PD. In: The Neurosciences: Second Study Program. Schmitt FO, editor. Rockefeller University Press; 1970. pp. 336–349. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience. Oxford U Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Panksepp J, Biven L. The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary origins of human emotions. W W Norton & Co; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Panksepp J, Sacks DS, Crepau LJ, Abbot BB. In: Fear, Avoidance, and Phobias. Denny MR, editor. Earlbaum; 1991. pp. 7–59. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson DJ, Adolphs RA. Framework for Studying Emotions across Species. Cell. 2014;157:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adolphs R. The biology of fear. Curr Biol. 2013;23:R79–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fanselow MS, Pennington ZT. A return to the psychiatric dark ages with a two-system framework for fear. Behav Res Ther. 2017;100:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fanselow MS, Pennington ZT. The Danger of LeDoux and Pine’s Two-System Framework for Fear. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:1120–1121. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17070818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.LeDoux JE, Brown R. A higher-order theory of emotional consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:E2016–E2025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619316114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortony A, Clore GL. Emotions, moods, and conscious awareness. Cognition and Emotion. 1989;3:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortony A, Turner TJ. What’s basic about basic emotions? Psychological Review. 1990;97:315–331. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barrett LF. How emotions are made. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett LF, et al. Of Mice and Men: Natural Kinds of Emotions in the Mammalian Brain? A Response to Panksepp and Izard. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2007;2:297–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00046.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrett LF, Russell JA. Guilford Press; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 46.LeDoux J. Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron. 2012;73:653–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeDoux JE. Coming to terms with fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:2871–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400335111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Block N, et al. Consciousness science: real progress and lingering misconceptions. Trends Cogn Sci. 2014;18:556–557. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gazzaniga MS. The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the mystery of how the brain makes the mind. (Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baars BJ, Franklin S. An architectural model of conscious and unconscious brain functions: Global Workspace Theory and IDA. Neural networks. 2007;20:955–961. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dehaene S. Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering how the brain codes our thoughts. (Penguin Books; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dehaene S, Changeux JP. Experimental and theoretical approaches to conscious processing. Neuron. 2011;70:200–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lau H, Rosenthal D. Empirical support for higher-order theories of conscious awareness. Trends Cogn Sci. 2011;15:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frith C, Perry R, Lumer E. The neural correlates of conscious experience: an experimental framework. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 1999;3:105–114. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(99)01281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gray JA. Consciousness: creeping up on the hard problem. (Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jack AI, Shallice T. Introspective physicalism as an approach to the science of consciousness. Cognition. 2001;79:161–196. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Overgaard M. On the theoretical and methodological foundations for a science of consciousness. Bulletin fra Forum For Antropologisk Psykologi. 2003;13:6–31. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Breitmeyer BG, Ogmen H. Visual Masking: Time Slices Through Conscious and Unconscious Vision. (Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rees G, Frith C. In: The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Velmans M, Schneider S, editors. Blackwell; 2007. pp. 551–566. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schacter DL. In: Varieties of memory and consciousness: Essays in honour of Endel Tulving. Roediger HL III, Craik FIM, editors. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1989. pp. 355–389. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lewis M. The rise of consciousness and the development of emotional life. (The Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gazzaniga MS. The Bisected Brain. (Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gazzaniga MS, LeDoux JE. The Integrated Mind. (Plenum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Milner B. The memory defect in bilateral hippocampal lesions. Psychiatr Res Rep Am Psychiatr Assoc. 1959;11:43–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Corkin S. Acquisition of motor skill after bilateral medial temporal lobe excision. Neuropsychologia. 1968;6:255–265. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Squire LR. Mechanisms of memory. Science. 1986;232:1612–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.3086978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weiskrantz L, Warrington EK, Sanders MD, Marshall J. Visual capacity in the hemianopic field following a restricted occipital ablation. Brain. 1974;97:709–728. doi: 10.1093/brain/97.1.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weiskrantz L. Blindsight: A case study and implications. (Clarendon Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jacob J, Jacobs C, Silvanto J. Attention, working memory, and phenomenal experience of WM content: memory levels determined by different types of top-down modulation. Front Psychol. 2015;6:1603. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lau HC, Passingham RE. Relative blindsight in normal observers and the neural correlate of visual consciousness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;10(3):18763–18768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607716103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gaillard R, et al. Converging intracranial markers of conscious access. PLoS biology. 2009;7:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehaene S, Changeux JP, Naccache L, Sackur J, Sergent C. Conscious, preconscious, and subliminal processing: a testable taxonomy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dehaene S, Lau H, Kouider S. What is consciousness, and could machines have it? Science. 2017;358:486–492. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Odegaard B, Knight RT, Lau H. Should a Few Null Findings Falsify Prefrontal Theories of Conscious Perception? J Neurosci. 2017;37:9593–9602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3217-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Damasio A. Self Comes to Mind: Constructing the conscious brain. New York: Pantheon Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ericcson KA, Simon H. Protocol analysis: Verbal reports as data. (MIT Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilson TD. The Proper Protocol: Validity and Completeness of Verbal Reports. Psychological Science. 1994;5:249–252. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maniscalco B, Lau H. The signal processing architecture underlying subjective reports of sensory awareness. Neurosci Conscious. 20162016 doi: 10.1093/nc/niw002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Overgaard M, Sandberg K. In: The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition. Fleming SM, Frith CD, editors. Springer-Verlag; Berlin Heidelberg: 2014. pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Seth AK, Dienes Z, Cleeremans A, Overgaard M, Pessoa L. Measuring consciousness: relating behavioural and neurophysiological approaches. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:314–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Persaud N, McLeod P, Cowey A. Post-decision wagering objectively measures awareness. Nature neuroscience. 2007;10:257–261. doi: 10.1038/nn1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seth AK. Post-decision wagering measures metacognitive content, not sensory consciousness. Consciousness and cognition. 2008;17:981–983. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Preuss TM. The human brain: rewired and running hot. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1225(Suppl 1):E182–191. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rilling JK, Glasser MF, Jbabdi S, Andersson J, Preuss TM. Continuity, divergence, and the evolution of brain language pathways. Front Evol Neurosci. 2011;3:11. doi: 10.3389/fnevo.2011.00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Semendeferi K, et al. Spatial organization of neurons in the frontal pole sets humans apart from great apes. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1485–1497. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Teffer K, Semendeferi K. Human prefrontal cortex: evolution, development, and pathology. Prog Brain Res. 2012;195:191–218. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tulving E. In: The Missing Link in Cognition. Terrace HS, Metcalfe J, editors. Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 4–56. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Corballis MC. Language Evolution: A Changing Perspective. Trends Cogn Sci. 2017;21:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tomasello M, Rakoczy H. What Makes Human Cognition Unique? From Individual to Shared to Collective Intentionality. Mind & Language. 2003;18:121–147. doi: 10.1111/1468-0017.00217. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.MacLean EL. Unraveling the evolution of uniquely human cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:6348–6354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521270113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Heyes C. Animal mindreading: what’s the problem? Psychon Bull Rev. 2015;22:313–327. doi: 10.3758/s13423-014-0704-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shettleworth SJ. Clever animals and killjoy explanations in comparative psychology. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:477–481. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Suddendorf T, Corballis MC. The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behav Brain Sci. 2007;30:299–313. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X07001975. discussion 313-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Terrace H, Metcalfe J. The missing link in cognition: Origins of self-reflective consciousness. (Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Khoury B, et al. Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33:763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical psychology review. 2015;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. (Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Creswell JD. Mindfulness Interventions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017;68:491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.LeDoux JE. The Emotional Brain. (Simon and Schuster; 1996. [Google Scholar]