Abstract

Glyphosate is a widely used herbicide that inhibits the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS)-encoding aroA gene in the shikimate pathway. The discovery and cloning of the aroA gene with high resistance is central to breeding a transgenic glyphosate-resistant plant. A novel aroAPantoea gene from Pantoea G-1 was previously isolated and cloned. The aroA Pantoea enzyme was defined as a new class I EPSPS with glyphosate resistance. The aroA Pantoea gene was introduced into tobacco through Agrobacteriummediated transformation. The transgenic tobacco plants were confirmed by PCR, RT-PCR, and Southern blot. The analysis of glyphosate resistance also showed that the transgenic tobacco plants could survive at 15 mM glyphosate; the glyphosate resistance level of the transgenic plants is higher than the agricultural application level recommended by most manufacturers. Overall, this study shows that aroAPantoea can be used as a candidate gene for the development of genetically modified crops.

Keywords: aroA, glyphosate, Pantoea, tobacco, transformation

1. Introduction

As a broad-spectrum herbicide, glyphosate is used to kill most kinds of weeds (Steinrücken and Amrhein, 1980) . Glyphosate blocks plant growth by inhibiting 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS; EC 2.5.1.19), which is a critical enzyme in the shikimate pathway (Schönbrunn et al., 2001) that is important for the synthesis of aromatic amino acids and a number of secondary metabolites in plants and microorganisms (Amrhein et al., 1980) . EPSPS catalyzes shikimate-3-phosphate (S3P) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) into 5-enolpyruvylshikimate3-phosphate (EPSP) and inorganic phosphate (Baerson et al., 2002) , respectively. Glyphosate and PEP are analogous; therefore, glyphosate inhibits EPSPS synthesis and causes plant death (Duke and Powles, 2008). Because of this nonselective property, glyphosate also kills food crops. Today, much attention is paid to finding glyphosate-tolerant genes for genetically modified crops.

Since the transgenic tobacco overexpressing mutant aroA gene was first reported (Stalker et al., 1985), many aroA genes have been identified and cloned over the past three decades (Rogers et al., 1983; Sost and Amrhein, 1990; Zhou et al., 1995). EPSPS proteins have been divided into two major types: class I and class II (He et al., 2001). Class I EPSPS is found in all plants and microorganisms, including Convolvulus arvensis, Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Rogers et al., 1983; Sost et al., 1990; Wang et al., 2003; Funke et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2014) and is sensitive to glyphosate. Class II enzymes are found in Pseudomonas stutzeri A1501, Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain CP4, Halothermothrix orenii H168, and Bacillus cereus (Li et al., 2009; Tian et al., 2012, 2013). Class II aroA genes have been used to enhance glyphosate tolerance in transgenic plants (Cao et al., 2012; Yi et al., 2016) . A novel aroA gene cloned from Pseudomonas putida 4G-1 has also been defined as neither class I nor class II (Sun et al., 2005). Until now, only the aroA gene from Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain CP4 has been commercialized successfully (Zhou et al., 1995).

In our previous study, an aroA gene from a glyphosatetolerant strain, Pantoea G-1 (designated as aroAPantoea), was isolated from heavily contaminated soil and functionally characterized (Liu and Cao, 2015). Its glyphosate resistance level has not been systematically studied in transgenic plants. In the current study, we transplant the aroAPantoea gene into tobacco and assess the glyphosate tolerance of transgenic tobacco plants in order to demonstrate that the glyphosate resistance of transgenic tobacco can reach up to 15 mM glyphosate (1.23 kg a.e. ha–1), the glyphosate resistance level of the transgenic plants being higher than the agricultural application level recommended by most manufacturers (Guo et al., 2015). Furthermore, transgenic tobacco plants were used to evaluate the potential of aroA Pantoea in developing glyphosate-resistant crops.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Construction of the plant expression vector

The construction of the plant expression vector was performed according to a previous report (Xu et al., 2010) . To ensure that the aroA gene would be localized to the plant chloroplast, the DNA fragment that encoded the chloroplast transit peptide of Arabidopsis (TSP) was inserted into the front of the aroA gene (Della-Cioppa et al., 1986). The final construction, D35S:TSP:aroA:Nos, was introduced into A. tumefaciens GV3101 through electroporation. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into the tobacco plants using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation.

2.2. Tobacco transformation

Construction of the PHB vector was used for the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv. Xanthi) transformation according to a previous report (Yan et al., 2011) . To begin, 50 mg L–1 hygromycin was used as the selected marker. The transgenic tobacco plants were confirmed through PCR amplification of the aroA gene. The PCR fragments were amplified using specific primers (5-ATGCAGGACTCCCTGACTTTACAG3 ; 5 - TC AG G C G C TC TG G C TG AT T T T TG C C A- 3 ) , resulting in 1287 bp of amplified PCR product (aroA Pantoea sp.). The PCR products were analyzed using 1% agarose gels and electrophoresis.

2.3. RT-PCR and qRT-PCR

To analyze tissue-specificity expression of the aroA Pantoea, transgenic tobacco leaves, stems and roots of 30-dayold seedlings were used respectively in the greenhouse. The total RNA extraction from the tobacco tissues was conducted using an RNA prep pure kit for plants (Tiangen Biotech). The first-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Takara). For RT-PCR, 2 µL of cDNA was used as a template for 30 amplification cycles using PCR. The fragment products were analyzed using 1% agarose gels and electrophoresis.

qRT-PCR analysis was used to observe the aroAPantoea gene expression according to a previous report (Liu et al., 2015; Yıldırım, 2017 ). Specific primers (5-CGGCAATGACAATCGCTACC-3 and 5-AAAATCGTGCCCCTCTTCCA-3) were used to amplify the aroAPantoea gene. A ubiquitin gene (accession number: U66264.1) was used as the housekeeping gene. The transgenic tobacco plants were sprayed with 15 mM glyphosate at the six-leaf stage and the leaves were harvested at 12, 24, 36, and 48 h after glyphosate treatment and used for gene expression analysis. The expression level of the aroAPantoea gene was calculated using the 2–ΔΔt method. Each sample was biologically repeated three times.

2.4. Determining the level of chlorophyll content

The chlorophyll content was tested according to a previous report (Guo et al., 2015; Sucu et al., 2017). Forty-day-old plants of wild-type tobacco and transgenic tobacco were sprayed with 15 mM glyphosate. The SPAD values of the leaves from the different tobacco plants were calculated using a SPAD-502 Plus chlorophyll measuring instrument at different times (0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h) after glyphosate treatments. This meter measures absorption at 650 and 940 nm wavelengths in order to determine the chlorophyll levels (Gao et al., 2014; Yıldırım and Uylas, 2016) . At least six replications were confirmed for each treatment.

2.5. Determining the level of shikimic acid

The level of shikimic acid was calculated according to a previous report (Gao et al., 2014). First, 40-day-old plants were sprayed with 15 mM glyphosate, and approximately 0.2 g of young tobacco leaves was taken at different times (0, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h) and put into an ice-bath mortar for continuous grinding. Then 1.0 mL of HCl was added and the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min (4 °C). Next, 2 mL of 0.1% periodic acid was added to 200 µL of supernatant for 3 h. Then 2 mL of NaOH (0.1 mol/L) and 1.5 mL of glycine (0.1 mol/L) were added to the mixture. Finally, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 380 nm using a spectrophotometer. The shikimate content was measured using a shikimate standard curve.

2.6. Southern blot analysis

Selected PCR-positive T0 transgenic tobacco plants were further analyzed by Southern hybridization for the integration of the aroAPantoea. Tobacco genomic DNA was extracted from the leaves of the putative transgenic plants and wild-type plants using the CTAB method. Genomic DNA (100 µg) was entirely digested overnight at 37 °C using EcoR I. The digestion products were separated on 1.0% agarose gel through electrophoresis and transferred to a Hybond N+ nylon membrane. The PCR fragment of the aroA gene was amplified using primers (5-AGCGTTTCCAGCCAGTTC-3, 5-CTCCCATCTTCTCCAGCAC-3) and was labeled using a DIG High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II (Roche). The hybridization and detection steps were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.7. Analysis of glyphosate resistance in transgenic tobacco

To detect the glyphosate tolerance of T0 plants, the tobacco transformants were grown in MS culture medium for 3 weeks with 16 h of light and 8 h of dark. Seedlings were transferred to soil and grown in the greenhouse for 1 month. Five- to-six-leaf-stage transgenic and wild-type tobacco plants were sprayed with 15 mM glyphosate and the results were observed after 2 weeks.

2.8. Seed germination assays

The tobacco seeds (transgenic and wild-type) were disinfected with 15% NaClO for 15 min and then rinsed at least three times with sterile water. The T 1 sterilized transgenic line NT-1 was grown on MS medium containing glyphosate (0, 300, 500, and 1000 µM) in petri dishes in a controlled environment chamber at 25 °C with a 16/8-h day/night cycle. A photograph was taken after 2 weeks of growth and the root length was measured.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was used for analysis of significant differences with SAS 9.2 at a level of P < 0.01. All of the figures were created using Origin 8.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of plant expression vector

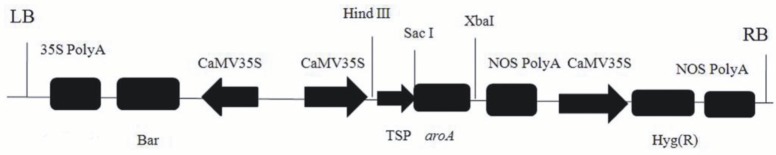

A plant expression vector containing the aroA gene was constructed in order to test the glyphosate resistance of the aroAPantoea gene (GenBank: ARH59536.1) in the transgenic T0 plants. In the vector, the signal peptide sequence of Arabidopsis and the aroA coding sequence were cloned into the T-DNA box of the PHB vector (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The aroA expression vector for tobacco transformation.

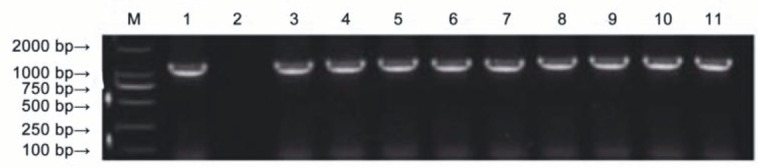

3.2. Obtaining transgenic tobacco with an aroAPantoea gene

The plant expression vector, PHB-TSP-aroA Pantoea, was transferred into tobacco leaf disks via an Agrobacteriummediated transformation. The tobacco callus medium was first screened for a 50-mg L –1 hygromycin selection, which is a marker of the PHB vector. Twenty hygromycinresistant plants were regenerated during this genetic transformation process. A molecular analysis was executed with PCR in order to determine the integration of the aroAPantoea gene into the T0 generation. Only nine hygromycin-resistant plants showed amplification of the expected 1287-bp fragment of aroAPantoea, while no amplification was observed in the nontransgenic plants (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The glyphosate-tolerant transgenic plants were confirmed by PCR analysis. M: 2000-bp DNA marker; 1: PHB-TSP-aroAPantoea plasmid as the positive control; 2: nontransgenic tobacco as the negative control; 3–11: transgenic plants.

3.3. Expression analysis of the gene by RT-PCR and qRTPCR

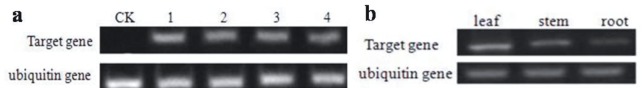

The leaves of four transgenic tobacco lines showed transcription levels of the aroAPantoea gene using RT-PCR. Transgenic lines were expressed at the transcriptional level while the wild-type did not have any specific bands (Figure 3a). The transcription expression level in different tissues (leaf, stem, and root) was also tested. The highest expression level of the aroAPantoea gene was detected in the leaves, while a relatively low transcription expression level was found in the stem and roots (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Expression analysis of aroA by semiquantitative RT-PCR. a) Expression analysis of four transgenic lines. CK: Nontransgenic plant; 1–4: four putative transgenic lines. b) mRNA level of the aroA in different tissues of transgenic lines.

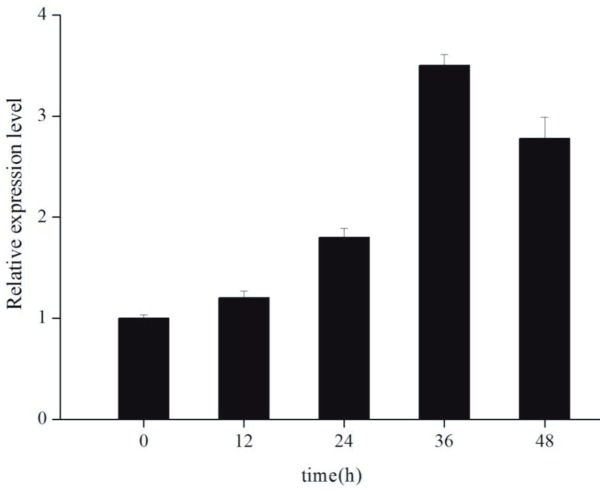

qRT-PCR was used to analyze the target gene expression in the leaves of wild-type and transgenic tobacco plants at various times after glyphosate application. The transcription expression level of the aroA Pantoea gene increased threefold after 36 h (Figure 4). Consequently, the expression of the aroAPantoea gene increased at the transcription level after glyphosate application.

Figure 4.

mRNA level of the aroA after glyphosate treatment. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was used for detecting expression level. Error bars are SE (n = 3).

3.4. Chlorophyll content and shikimic acid assay

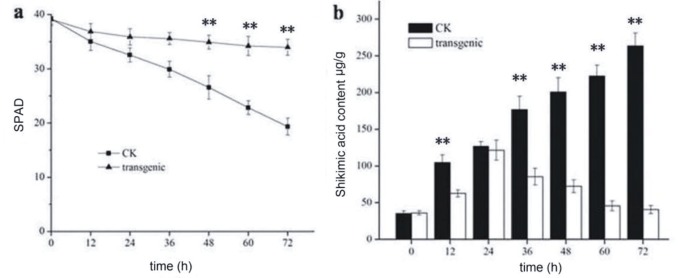

There were no significant differences in chlorophyll content between the leaves of the wild-type and transgenic plants before glyphosate treatment. The chlorophyll content decreased significantly 72 h after glyphosate treatment in the wild plants. However, the transgenic tobacco showed no significant alteration in chlorophyll content at any time (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Physiological content in in transgenic and nontransgenic plants. a) Chlorophyll contents. b) Contents of the shikimic acid. CK: Nontransgenic plant. Data represent means ± SE from three replicates. Statistical significance was determined by Student’s t-test (**, P < 0.01). Asterisks indicate the difference between CK and transgenic plants of aroAPantoea.

The accumulation of shikimic acid is often used as a biomarker for glyphosate eefcts. The results demonstrated that the amount of shikimic acid in the wild tobacco significantly increased after glyphosate treatment. The content of shikimic acid in the transgenic tobacco was much lower than that of the wild plants (Figure 5b). This showed that the growth and plant development of the transgenic tobacco that overexpresses aroAPantoea was normal after glyphosate treatment.

3.5. Glyphosate tolerance in transgenic tobacco plants and Southern blot analysis

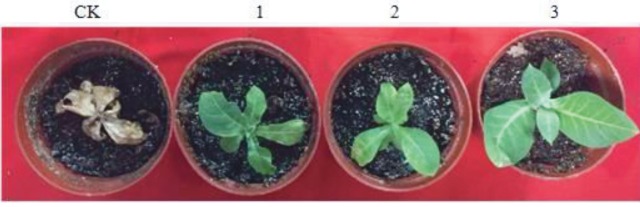

In our study, 2 weeks after spraying 15 mM glyphosate, the leaves of the wild-type tobacco turned yellow, leading to death, whereas the transgenic tobacco continued to grow well after treatment (Figure 6). The results also showed that the transgenic tobacco overexpressing aroAPantoea had more glyphosate resistance than the wild-type.

Figure 6.

The transgenic plants (T0) were sprayed with glyphosate at 15 mM after 2 weeks. CK: Nontransgenic plant; 1–3: transgenic plants.

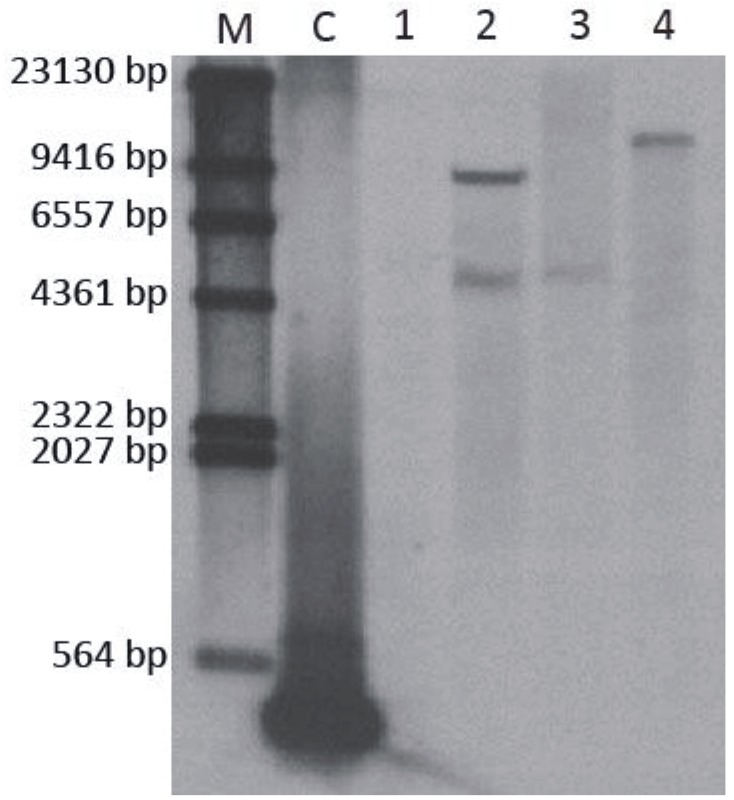

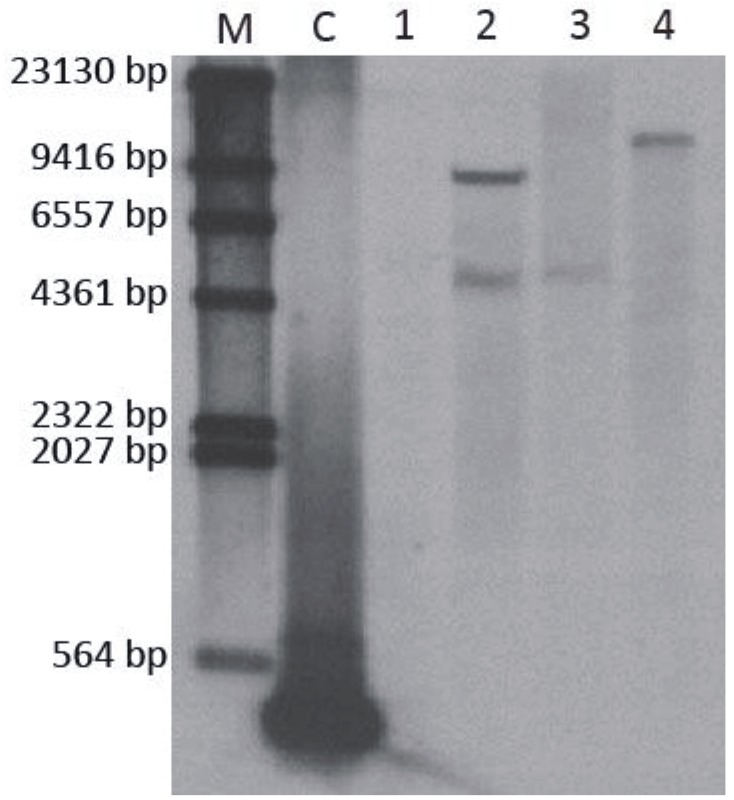

First, the transgenic tobacco plants were confirmed by PCR and RT-PCR. Second, we identified three transgenic tobacco plants through Southern blot hybridization in these transgenic lines. As shown in Figure 7, the results confirmed that the aroA Pantoea gene was stably integrated into the tobacco genome. The copy number of the aroA Pantoea gene in the transgenic NT-1 line was a single copy. The T1 progeny from the NT-1 line showed a 3:1 segregation ratio for resistance to glyphosate (data not shown), which suggests one expressed copy of aroAPantoea.

Figure 7.

Southern blot analysis of T0 transgenic tobacco. M: DNA marker; C: probe as the positive control; 1: nontransgenic plant as the negative control; 2–4, transgenic NT-3, NT-2, and NT-1, respectively.

3.6. Glyphosate tolerance in T1 seedlings

To investigate the genetic stability of T1 transgenic plants, we observed the glyphosate tolerance of transgenic tobacco in solid MS medium with different concentrations of glyphosate. The results also showed that the transgenic NT-1 line grew well in 1000 µM glyphosate, whereas the wild-type did not germinate at 300 µM (Figure 8a). The root length was measured, and the results showed that the NT-1 line that overexpressed aroAPantoea had a significantly

Figure 8.

Comparative germination of transgenic seeds on MS medium containing various glyphosate concentrations (0, 300, 500, 1000 μM) in petri dishes. b) The comparative image of root length between NT-1 and CK on MS medium containing various glyphosate concentrations (0, 300, 500, and 1000 μM) in petri dishes. c) The root length of the tobacco plants. Asterisk means significant difference at P < 0.01, bar = 0.5 cm.

0) were sprayed with glyphosate at 15 mM after 2 weeks. CK: Nontransgenic plant; 1–3: transgenic longer root length than the wild-type. It is apparent that the NT-1 line had stronger glyphosate tolerance than the wild-type (Figures 8b and 8c), and that the aroAPantoea gene could be a stable inheritance for glyphosate resistance.

4. Discussion

In our previous study, a new aroA gene that belongs to the class I EPSPS with high glyphosate tolerance (Liu and Cao, 2015) was obtained from Pantoea G-1 in glyphosate-polluted soil. A class I aroA gene can be naturally glyphosate-resistant, and some aroA genes have been assessed in Proteus mirabilis and Janibacter sp. (Tian et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2016) . Although Pantoea sp. widely exists in soil, there were no previous reports on glyphosate resistance.

Two pathways for the improvement of glyphosate tolerance have been recently identified. One involves the mutation of amino acids in active aroA sites, which has been studied by many scholars (Sost et al., 1990; He et al., 2001; Liang et al., 2008). The second pathway is using the aroA in class II EPSPS to indirectly induce glyphosate tolerance (Fitzgibbon and Braymer, 1990; Tian et al., 2010; Cao et al., 2012) . Since the 1980s, only the CP4-EPSPS gene has been commercially used for many years (Guo et al., 2015).

Glyphosate eefctively inhibits aroA by blocking the synthesis of aromatic amino acids, thus causing plant death. The transcription level of the aroA gene in different plant tissues is different. The transcription level showed that the aroA gene is expressed extensively in roots, stems, and leaves, being most highly expressed in the leaf. This expression model is consistent with the aroA expression observed in Convolvulus arvensis L. and Camptotheca acuminate (Gong et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2014). Glyphosate treatment could induce a significant increase of aroA gene expression level. The expression of the aroA gene could be induced by spraying glyphosate at a significantly upregulated level. In this experiment, the peak induction was 36 h after spraying glyphosate, which was 3-fold higher than the control group’s expression level. In field bindweed, the expression level of EPSPS was also responsive to glyphosate (Huang et al., 2014). These results show that the aroA gene plays an important role in the response to glyphosate.

Treating plants with glyphosate aefcted EPSPS activity by reducing chlorophyll content and causing the accumulation of shikimic acid (Powell et al., 1992; Guo et al., 2015). Spraying glyphosate can cause the accumulation of shikimic acid content in glyphosate-sensitive plants, but tolerant plants lack shikimic acid accumulation (Gao et al., 2014). Shikimic acid content can be used as a marker of glyphosate resistance (Binarová et al., 1994). Low shikimate accumulation in transgenic plants revealed higher glyphosate tolerance compared to the wild-type plants. When spraying with 15 mM glyphosate, the transgenic tobacco plants with the new aroA gene were morphologically normal. In addition, the glyphosate resistance level of the transgenic tobacco is higher than the agricultural application level recommended by most manufacturers. We also compared our results with previous studies, which showed that the glyphosate tolerance level of transgenic A. thaliana tobacco is 10 mM and 5 mM (Peng et al., 2012; Han et al., 2014), respectively. The 15 mM glyphosate tolerance of transgenic tobacco is obviously higher.

In summary, we assessed the glyphosate resistance of the aroAPantoea gene in transgenic tobacco plants and confirmed that aroA Pantoea shows high tolerance to glyphosate, indicating that the novel aroA gene would likely enhance glyphosate tolerance in engineered crops.

Acknowledgment

This research was financially supported by the National Transgenic Major Program (2016ZX08004001-04).

References

- Amrhein N , Deus B , Gehrke P , Steinrücken HC ( 1980. ). The site of the inhibition of the shikimate pathway by glyphosate II. Interference of glyphosate with chorismate formation in vivo and in vitro . Plant Physiol 66 : 830 - 834 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baerson SR , Rodriguez DJ , Tran M , Feng Y , Biest NA , Dill GM ( 2002. ). Glyphosate-resistant goosegrass. Identification of a mutation in the target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3- phosphate synthase . Plant Physiol 129 : 1265 - 1275 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binarová P Cvikrová M Havlický T Eder J Plevková J Changes of shikimate pathway in glyphosate tolerant alfalfa cell lines with reduced embryogenic ability. Biol Plant. 1994;36:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cao G Liu Y Zhang S Yang X Chen R Zhang Y Lu W Wang J Lin M Wang G A novel 5-enolpyruvylshikimate3-phosphate synthase shows high glyphosate tolerance in Escherichia coli and tobacco plants. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke SO Powles SB Glyphosate: a once-in-a-century herbicide. Pest Manage Sci. 2008;64:319–325. doi: 10.1002/ps.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon JE Braymer HD Cloning of a gene from Pseudomonas sp. strain PG2982 conferring increased glyphosate resistance. Appl Environ. Microbiol. 1990;56:3382–3388. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.11.3382-3388.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke T Yang Y Han H Healy-Fried M Olesen S Becker A Schonbrunn E Structural basis of glyphosate resistance resulting from the double mutation Thr97 -> Ile and Pro101 -> Ser in 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:9854–9860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M809771200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y Tao B Qiu L Jin L Wu J Role of physiological mechanisms and EPSPS gene expression in glyphosate resistance in wild soybeans (Glycine soja). Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2014;109:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B Guo Y Hong H Jin L Zhang L Chang RZ Lu W Lin M Qiu LJ Co-expression of G2-EPSPS and glyphosate acetyltransferase GAT genes conferring high tolerance to glyphosate in soybean. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:847. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J Tian YS Xu J Wang LJ Wang B Peng RH Yao QH Functional characterization of aroA from Rhizobium leguminosarum with significant glyphosate tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;24:1162–1169. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1312.12076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M Yang ZY Nie YF Wang J Xu P A new type of class I bacterial 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase mutants with enhanced tolerance to glyphosate. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2001;1568:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZF Zhang CX Huang HJ Wei SH Liu Y Cui HL Chen JC Yang L Chen JY Molecular cloning and characterization of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase gene from Convolvulus arvensis L. Mol Biol Rep. 2014;41:2077–2084. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L Lu W Han Y Ping S Zhang W Chen M Zhao Z Yan Y Jiang Y Lin M A novel RPMXR motif among class II 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3- phosphate synthases is required for enzymatic activity and glyphosate resistance. J Biotechnol. 2009;144:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang A Sha J Lu W Chen M Li L Jin D Yan Y Wang J Ping S Zhang W et al. 2008. A single residue mutation of 5-enoylpyruvylshikimate-3- phosphate synthase in Pseudomonas stutzeri enhances resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. Biotechnol Lett 30 1397 1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F Cao YP Cloning and characterization of 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3- phosphate synthase from Pantoea sp. Genet Mol Res. 2015;14:19233–19241. doi: 10.4238/2015.December.29.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y Cao G Chen R Zhang S Ren Y Lu W Wang J Wang G Transgenic tobacco simultaneously overexpressing glyphosate N-acetyltransferase and 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase are more resistant to glyphosate than those containing one gene. Transgenic Res. 2015;24:753–763. doi: 10.1007/s11248-015-9874-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng RH Tian YS Xiong AS Zhao W Fu XY Han HJ Chen C Jin XF Yao QH A novel 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3phosphate synthase from Rahnella aquatilis with significantly reduced glyphosate sensitivity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell HA Kerby NW Rowell P Mousdale DM Coggins JR Purification and properties of a glyphosate-tolerant 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase from the cyanobacterium Anabaena variabilis. Planta. 1992;188:484–490. doi: 10.1007/BF00197039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers S Brand L Holder S Sharps E Brackin M Amplification of the aroA gene from Escherichia coli results in tolerance to the herbicide glyphosate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;46:37–43. doi: 10.1128/aem.46.1.37-43.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönbrunn E Eschenburg S Shuttleworth WA Schloss JV Amrhein N Evans JN Kabsch W Interaction of the herbicide glyphosate with its target enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase in atomic detail. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:1376–1380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.4.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sost D Amrhein N Substitution of Gly-96 to Ala in the 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase of Klebsiella pneumoniae results in a greatly reduced afinity for the herbicide glyphosate. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1990;282:433–436. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90140-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalker DM Hiatt WR Comai L A single amino acid substitution in the enzyme 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3phosphate synthase confers resistance to the herbicide glyphosate. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:4724–4728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinrücken H Amrhein N The herbicide glyphosate is a potent inhibitor of 5-enolpyruvylshikimicacid-3-phosphate synthase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;94:1207–1212. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)90547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucu S Yağcı A Yıldırım K Changes in morphological, physiological traits and enzyme activity of graeftd and ungraeftd grapevine rootstocks under drought stress. ErwerbsObstbau. 2018;(in press) [Google Scholar]

- Sun YC Chen YC Tian ZX Li FM Wang XY Zhang J Xiao ZL Lin M Gilmartin N Dowling DN et al 2005. Novel AroA with high tolerance to glyphosate, encoded by a gene of Pseudomonas putida 4G-1 isolated from an extremely polluted environment in China. Appl Environ Microbiol 71 4771 4776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian YS Jin XF Xu J Han J Zhao W Fu XY Peng RH Wang RT Yao QH Isolation from Proteus mirabilis of a novel class I 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase with glyphosate tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Physiol Plant. 2014;36:549–554. [Google Scholar]

- Tian YS Xiong AS Xu J Zhao W Gao F Fu XY Xu H Zheng JL Peng RH Yao QH Isolation from Ochrobactrum anthropi of a novel class II 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase with high tolerance to glyphosate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6001–6005. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00770-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian YS Xu J Han J Zhao W Fu XY Peng RH Yao QH Complementary screening, identification and application of a novel class II 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Bacillus cereus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29:549–557. doi: 10.1007/s11274-012-1209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian YS Xu J Xiong AS Zhao W Gao F Fu XY Peng RH Yao QH Functional characterization of class II 5-enopyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Halothermothrix orenii H168 in Escherichia coli and transgenic Arabidopsis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:241–250. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3443-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HY Li YF Xie LX Xu P Expression of a bacterial aroA mutant, aroA-M1, encoding 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3phosphate synthase for the production of glyphosate-resistant tobacco plants. J Plant Res. 2003;116:455–460. doi: 10.1007/s10265-003-0120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J , Zuo K , Lu W , Zhu Y , Ye C , Lin M , Tang K ( 2014. ). Overexpression of the Gr5aroA gene from glyphosate-contaminated soil confers high tolerance to glyphosate in tobacco . Mol Breed 33 : 197 - 208 . [Google Scholar]

- Xu J , Tian YS , Peng RH , Xiong AS , Zhu B , Jin XF , Gao F , Fu XY , Hou XL , Yao QH ( 2010. ). AtCPK6, a functionally redundant and positive regulator involved in salt/drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis . Planta 231 : 1251 - 1260 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan HQ , Chang SH , Tian ZX , Zhang L , Sun YC , Li Y , Wang J , Wang YP ( 2011. ). Novel AroA from pseudomonas putida confers tobacco plant with high tolerance to glyphosate . PLoS One 6 : e19732 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi SY , Cui Y , Zhao Y , Liu ZD , Lin YJ , Zhou F ( 2016. ). A novel naturally occurring class I 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase from Janibacter sp. confers high glyphosate tolerance to rice . Sci Rep 6 : 19104 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım K ( 2017. ). Transcriptomic and hormonal control of boron uptake, accumulation and toxicity tolerance in poplar . Environ Exp Bot 141 : 60 - 73 . [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım K , Uylas S ( 2016. ). Genome wide transcriptome profiling of black poplar (Populus nigra L.) under boron toxicity revealed candidate genes responsible in boron uptake transport and detoxification . Plant Physiol Biochem 109 : 146 - 155 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]