Clinical Context

A 12‐year‐old girl presented with a 2‐year history of rhythmic ear clicks. She was born 7 weeks premature with caesarean without fetal distress and had a normal psychomotor development. A strabismus was corrected by surgery.

The clicks started concurrently with an acute infectious sinusitis. These involuntary clicks were not bothersome and stopped during sleep. They were present every day with a fluctuating intensity. Free intervals shorter than 2 days may rarely occur. She had no particular tricks to control the clicks, and no provoking factors were identified. Examination revealed isolated continuous rhythmic bilateral and symmetrical brisk movements of the soft palate (see Video 1). Brain MRI was normal with no hypertrophy of the inferior olive. Because the movements of the soft palate seemed quite irregular, she was referred to our neurophysiology department to determine precisely the palatal tremor (PT) frequency and to perform frequency entrainment trials in order to examine the psychogenic hypothesis.

Video Recording

Surface electromyography performed over the digastric muscles displayed no abnormal activity. A standard video‐audio camera was used to record the open‐mouth uvula and soft‐palate movement. Duration of records was set at 30 seconds, repeated twice, with a pause between each sequence, drinking water if needed. During entrainment trials, the patient was asked to match her wrist movement with the target rate corresponding to a given metronome frequency. Tone frequencies were consecutively set at 1, 2, and 2.66 Hz. Frequency of the finger tapping was monitored by using the sound produced by a metallic ring attached to the middle finger at each beating on the table.

Method of Analysis

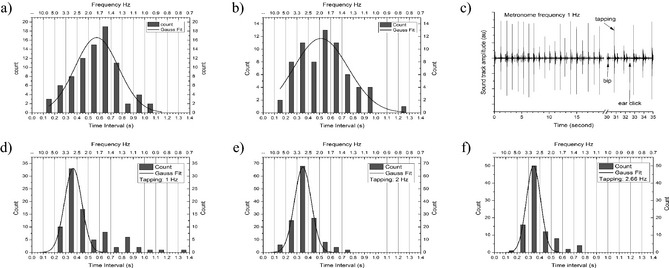

The video record shows a repetitive and rhythmic movement of the soft palate associated with the auditory click.1 Assessment of limb tremor frequency using a specific video analysis program has been previously reported.2 A more detailed analysis of the movement of the uvula was developed here using software devoted to the simultaneous study of the sound and the image. We selected “Adobe Soundbooth CS3” to observe a frame after frame record. It was then possible to record the time readable on the time track by selecting a reproducible position of the uvula, such as the upper one (see Video 1). One obtains a time interval table of the uvula up position. A frequency count was done selecting bin size (0.1 seconds) and number, taking into account the number of up uvula collected. Two binning's results, for each sequence, were added to analyze the time interval distribution using Gaussian fit, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Time interval counts and Gaussian fitting obtained (A) before and (B) after entrainment trial and (C) soundtrack showing metronome bip, hand tapping, and ear click. Entrainment trials performed at (D) 1, (E) 2, and (F) 2.66 Hz.

Audible ear clicking was recorded on the videotape (Fig. 1C). Because soundtrack analysis revealed fewer amounts of clicks than those observed on the video image record, they were not collected for analysis.

Results

Fitting curves are shown in Figure 1 and characteristic fitting values in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic time interval distribution fitting values

| Trial | Main Time Interval (s) | Time Interval SD (s) | Main Frequency (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before entrainment trial | 0.574 | 0.48 | 1.74 |

| Trial at 1 Hz | 0.366 | 0.15 | 2.73 |

| Trial at 2 Hz | 0.353 | 0.15 | 2.83 |

| Trial at 2.66 Hz | 0.345 | 0.13 | 2.90 |

| After entrainment trial | 0.514 | 0.57 | 1.95 |

Spontaneously, PT displayed a low main frequency below 2 Hz with a high dispersion of time intervals (standard deviation [SD]: 0.48–0.57 seconds). The patient performed effortlessly the rhythmic voluntary finger tapping at each frequency requested for entrainment trials. In the three consecutive competitive conditions (1, 2, and 2.66 Hz), PT main frequency shifted at approximately 2.8 Hz, with a significant reduction of the dispersion of time intervals (SD, 0.34–0.37), compared to the spontaneous condition.

Discussion

We propose a simple, noninvasive novel method based on video/audio recordings to analyze soft‐palate abnormal movements and study their changes in the frequency distribution under modifying tasks.

Psychogenic palatal tremor may be under‐recognized3 and can occur in children.4 The frequency entrainment sign is a core positive feature supporting the diagnosis of psychogenic tremor5 and was previously used in the setting of psychogenic PT.6 In some patients, this sign may be difficult to assess on clinical grounds only. Here, in this 12‐year‐old girl, the negative entrainment test strongly argues against a psychogenic PT. On contrary, during competitive rhythmic task, the PT displays a reproducible higher synchronization pattern approximately 3 Hz that seems independent on the frequency of the voluntary task. This may reflect the implication of a central generator activity, released from a voluntary control by distraction. This pure near‐3‐Hz frequency is in keeping with hypotheses about the central generator location in essential palatal tremor partly based on functional MRI studies7, 8 that may include the inferior olive through the dentato‐rubro‐olivary pathway or brainstem oscillatory nuclei.9, 10

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

A.P.L.: 1A, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B

H.E.: 2C, 3B

E.R.: 1A, 2C, 3B

M.V.: 2C, 3B

E.A.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2C, 3A, 3B

Disclosures

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no sources of funding and no conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for previous 12 months: E.R. is the recipient of a grant “poste d'accueil” AP‐HP/CNRS; received research support from INSERM (COSSEC), AP‐HP (DRC‐PHRC), Fondation pour la Recherche sur le Cerveau (FRC), the Dystonia Coalition (Pilot project), Ipsen, and Merz‐Pharma, Novartis, Teva, Lundbeck, and Orkyn; served on scientific advisory boards for Orkyn, Ipsen, and Merz‐pharma; received speech honorarium from Novartis, Teva, and Orkyn; and received travel funding from Teva, Novartis, the Dystonia Coalition, the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society, the World Federation of Neurology Association of Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, and the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. E.A. received research support from the Association des Personnes concernées par le Tremblement Essentiel (APTES).

Supporting information

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. Serial video sequences obtained before, during, and after entrainment are displayed in the order of the recording sessions and followed by video record numerical analysis procedure demonstration.

Relevant disclosures and conflicts of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Scozzafava J, Yager J. Essential palatal myoclonus. N Engl J Med 2010;362:e64 Available at: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMicm0806049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Uhrikovaa Z, Sprdlik O, et al. Validation of a new tool for automatic assessment of tremor frequency from video recordings. J Neurosci Methods 2011;198:110–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stamelou M, Saifee TA, Edwards MJ, Bhatia KP. Psychogenic palatal tremor may be underrecognized: reappraisal of a large series of cases. Mov Disord 2012;27(9):1164–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Margari F, GIanella G, Lecce PA, Fanizzi P, Toto M, Margari L. A childhood case of symptomatic essential and psychogenic palatal tremor. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2011;7:223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown P, Thompson P. Electrophysiological aids to the diagnosis of psychogenic jerks, spasms and tremor. Mov Disord 2001;16(4):595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Richardson SP, Mari Z, Matsuhashi M, Hallett M. Psychogenic palatal tremor. Mov Disord 2006;21(2):274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boecker H, Kleinschmidt A, Weindl A, Conrad B, Hänicke W, Frahm J . Dysfunctional activation of subcortical nuclei in palatal myoclonus detected by high‐resolution MRI. NMR Biomed 1994;7(7):327–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nitschke MF, Krüger G, Bruhn H, et al. Voluntary palatal tremor is associated with hyperactivation of the inferior olive: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Mov Disord 2001;16(6):1193–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deuschl G, Toro C, Valls‐Solé J, Zeffiro T, Zee DS, Hallett M. Symptomatic and essential palatal tremor. 1. Clinical, physiological and MRI analysis. Brain 1994;117(Pt 4):775–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zadikoff C, Lang AE, Klein C. The essentials of essential palatal tremor: a reappraisal of the nosology. Brain 2006;129:832–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A video accompanying this article is available in the supporting information here.

Video 1. Serial video sequences obtained before, during, and after entrainment are displayed in the order of the recording sessions and followed by video record numerical analysis procedure demonstration.