Abstract

DNA methylation (DNAm) is a term used to describe the heritable covalent addition of a methyl group to cytosines at CpG dinucleotides in mammals. While methods for examining DNAm status at specific loci have existed for several years, recent technological advances have begun to enable the examination of DNAm across the genome. In this unit, we describe comprehensive high-throughput arrays for relative methylation (CHARM), a highly sensitive and specific approach to measure DNA methylation across the genome. This method makes no assumptions about where functionally important DNAm occurs, i.e., CpG island or promoter regions, and includes lower-CpG-density regions of the genome. In addition, it uses a novel genome-weighted smoothing algorithm to correct for CpG density and fragment biases present in methyl-enrichment or methyl-depletion DNA-fractionation methods. It can be applied to studying epigenomic changes in DNAm for normal and diseased samples.

Keywords: DNA methylation, CHARM, epigenome, methylome

INTRODUCTION

DNA methylation (DNAm) is the mechanistically best-understood epigenetic mark. Epigenetic inheritance is non-sequence-based mitotic or meiotic retention of nuclear information. Since DNA methyltransferase I (DNMT1) recognizes hemimethylated CpG sites, mCpG is epigenetic information. Non-CpG methylation also occurs in higher eukaryotes, but at least at present, it is not epigenetic information per se since there is no mechanism for its stable propagation and it would appear to occur de novo at each cell division.

A great deal is known about the establishment and maintenance of DNAm, as well as the role it plays in regulating gene expression, maintaining genome stability, development, and imprinting. Examination of DNAm at the single-gene level has shown that altered methylation is perhaps the most common molecular abnormality in cancer (Feinberg and Tycko, 2004), and also appears to play an important role in many genetic disorders, including Rett Syndrome (Amir et al., 1999) and perhaps neuropsychiatric disease (Mill et al., 2008).

While a great deal is known about normal DNAm at specific loci across the genome and its alteration in disease at the single-gene level, as described briefly above, relatively little is known from an epigenomic perspective, i.e., DNAm signatures and/or alterations in disease across the human genome. Application of emergent technologies for studying DNAm across the genome has enabled us to begin to understand DNAm in normal differentiation and in disease (Feinberg, 2009). One such assay that was recently developed for epigenomic analysis of DNAm is comprehensive high-throughput arrays for relative methylation (CHARM; Irizarry et al., 2008). Although most microarray-based and targeted bisulfite sequencing strategies have focused on CpG-island and promoter regions of the genome, assumed to be functionally important, CHARM includes many CpG-sparse genomic regions.

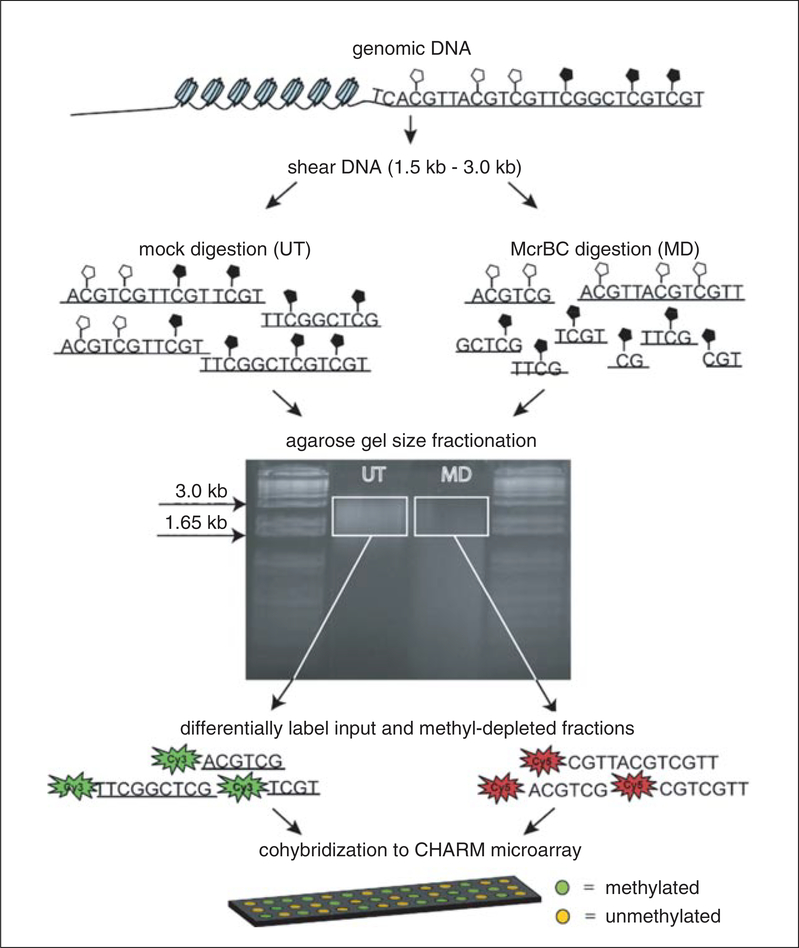

In this unit, we provide a detailed protocol for examination of DNAm across the epigenome using CHARM array hybridization and analysis (Basic Protocol). Please note that CHARM can be used on virtually any platform that fractionates methylated and unmethylated DNA, or either methylated or unmethylated DNA fractionated from total DNA (Fig. 20.1.1). However, we include here the specific methods that we prefer for fractionation of genomic DNA by random shearing (Support Protocol 1) and methylation- dependent McrBC digestion (Support Protocol 2), as well as methods for whole-genome amplification (Support Protocol 3), and quantitative PCR analysis to determine McrBC specificity and unmethylated DNA enrichment (Support Protocol 4).

Figure 20.1.1.

Overview of McrBC-based fractionation (Lippman et al., 2005; Ordway et al., 2006) coupled with CHARM analysis (Irizarry et al., 2008). Genomic DNA is sheared to 1.5 to 3.0 kb and divided into two equal parts. The first is digested with McrBC, a methyl-cytosine insensitive enzyme that recognizes PumC(N40–3000)mCPu, and the second is untreated. Both fractions are then resolved side by side on a 1% agarose gel, and fragments between 1.65 kb and 3.0 kb are excised and purified. Next, the untreated fraction, representing total input DNA, is labeled with cyanine-3 (Cy3) and the McrBC-treated fraction, representing unmethylated DNA, is labeled with cyanine-5 (Cy5) followed by cohybridization to a CHARM microarray. Sequences that are methylated will be present in the input fraction (Cy3) and depleted in the methyl-depleted fraction (Cy5). For each probe on the array, a log ratio of the Cy3 to Cy5 intensity is calculated and represents the methylation level (M-value) at each locus, with larger M-values representing more methylation and smaller M-values representing less methylation.

BASIC PROTOCOL

CHARM ARRAY HYBRIDIZATION AND ANALYSIS

In this protocol, we will describe how to label fractionated DNA and hybridize labeled DNA to a custom-designed CHARM microarray. In addition, we describe charm, an R package, for basic analysis of CHARM arrays including array normalization and identification of differentially methylated regions. Analysis is carried out using R and Bioconductor software packages (Gentleman et al., 2004).

Sample labeling and hybridization

A minimum of 3.5 μg of DNA is required for cyanine dye labeling. The fractionated DNA used in these labeling reactions should be prepared as described in Support Protocols 1 to 3, and should have also passed quality control as described in Support Protocol 4 using real-time PCR analysis. The labeling and hybridization steps used for CHARM were originally provided by NimbleGen for methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP). Here, we follow the protocol described in the NimbleGen Arrays User’s Guide for DNA methylation analysis (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/lit/methylation-userguide-v6p0.pdf) provided by Roche NimbleGen, with slight modifications that reflect differences between inputs for CHARM and MeDIP. For CHARM, we label the untreated DNA fraction with cyanine-3 and methyl-depleted fraction with cyanine-5, followed by cohybridization to a CHARM array (Roche NimbleGen HD2 platform), as shown in Figure 20.1.1.

Analyzing CHARM DNA methylation data

Raw data obtained from the CHARM microarrays (.xys files) can most easily be analyzed using the R/Bioconductor software environment (Gentleman et al., 2004), as normalization functions and a custom array annotation package have been made available.

There are three main components of CHARM array analysis. The first part of the analysis involves normalization. The basic measure of methylation is the log-ratio of intensities in the untreated and methyl-depleted channels. Normalization serves the dual purposes of setting the zero-methylation signal level within each array and removing the nonlinear dependence of the log-ratio (M) on the average signal intensity in the two channels (A). Loess normalization is widely used in two-color expression arrays to correct this M-A bias under the assumption that most genes are not differentially expressed (M=0) (Yang et al., 2002). However, this assumption is not appropriate when examining DNA methylation data, since many sites may be methylated and represented by positive M-values. A modified strategy involves fitting a loess regression through a subset of control probes known to represent unmethylated regions, and then applying this correction curve to all the probes on the array (Irizarry et al., 2008). The control probes are selected from CpG-free regions of the genome that are guaranteed to remain uncut by McrBC.

Following normalization, a moving window smoother is applied. The smoothed M-value at a given location is obtained by taking a weighted mean of probes within a prespecified distance of the location (Irizarry et al., 2008). A typical window size is 10 to 20 probes. This procedure significantly reduces the impact of probe-effect biases and noise on methylation estimates at the single-CpG level.

Lastly, regions with differential methylation between phenotypes are identified. For each probe, the average M-value is computed for each phenotype. Differential methylation is quantified for each pairwise tissue comparison by the difference of averaged M values (DM). Replicates are used to estimate probe-specific standard deviation (S.D.), which provide standard errors (S.E.M.) for DM. Z scores (DM/S.E.M.) are calculated, and statistically significant values (typically p < 0.001 or p < 0.005) are grouped into candidate DMR regions. A useful metric for ranking regions is the area defined as the length by average DM. In experiments with at least six biological replicates per experimental group, it is possible to calculate a statistical significance in terms of the false discovery rate (FDR) associated with each DMR. Permutation p values are generated using a null distribution of DMR areas generated by repeatedly assigning permuted group labels to samples and rerunning the DMR identification procedure. Permutation p values are then converted into q values (corresponding to FDRs) using the Bayesian procedure of Storey (2003).

Materials

NimbleGen Array User’s Guide downloaded from the Roche NimbleGen Web site (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/lit/methylation_userguide_v6p0.pdf)

NimbleScan Software User’s Guide downloaded from the Roche NimbleGen Web site (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/lit/NimbleScan_v2p5_UsersGuide.pdf)

Bioconductor software (http://www.bioconductor.org), with the packages: oligo (http://bioconductor.org/packages/bioc/html/oligo.html) qvalue (http://bioconductor.org/packages/bioc/html/qvalue.html)

CHARM microarray annotation package: pd.feinberg.hg18.me.hx1 (http://rafalab.jhsph.edu/software.html)

NimbleScan feature extraction software (Roche NimbleGen)

3.5 μg untreated DNA sample (obtained using Support Protocols 1, 2, and 3), analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR to evaluate the specificity of McrBC in the digestion reaction (Support Protocol 4)

3.5 μg methyl-depleted DNA sample (obtained using Support Protocols 1, 2, and 3), analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR to evaluate the specificity of McrBC in the digestion reaction (Support Protocol 4)

CHARM HD2 microarrays and supplies for HD2 array hybridization and processing (NimbleGen): see the NimbleGen Array User’s Guide at the URL above

R Software (http://www.r-project.org)

-

1.Download the NimbleGen Arrays User’s Guide for DNA methylation analysis (http://www.nimblegen.com/products/lit/methylation–userguide–v6p0.pdf) from the Roche NimbleGen Web site. This guide describes in detail all steps required for labeling, hybridizing, and scanning HD2 arrays. Follow the User’s Guide beginning at Chapter 1, page 3 (Components Supplied) up to Chapter 5, page 41, with the following exceptions:

- The twelve sample tracking controls (STCs), described on pages 7 and 19 to 20 are not required for the CHARM assay.

- The experimental (IP) sample described throughout the NimbleGen Array User’s guide should be substituted with the methyl-depleted (MD) fraction for each sample. The control (input) sample described throughout the NimbleGen Array User’s Guide should be replaced by the untreated (UT) fraction for each sample.

- The nonspecific binding (NSB) sample described in Chapter 3, page 13, of the array User’s Guide is not required for the CHARM assay.

- Throughout the user’s guide, be sure to follow all detailed guidelines and recipes specified for the 2.1 M Arrays.

- After completing all steps of the NimbleGen Arrays User’s Guide, pages 3 to 41, a .tif image is obtained for each array. These .tif images are used in the subsequent step by the NimbleGen software to generate X, Y and Signal reports (.xys files).

-

2.Download the NimbleScan Software User’s Guide (http://www.nimblegen.com/productsAit/NimbleScan–v2p5–UsersGuide.pdf) from the Roche NimbleGen Web site. Follow the detailed instructions for generating X, Y and Signal reports (.xys files) in Chapter 5 (Producing Reports), pages 58 to 63.

- The X, Y and Signal reports provide the coordinates of each feature and its intensity on each CHARM array. Pages 110 and 111 of the NimbleScan Software User’s Guide provide a description and example of X, Y and Signal reports.

- The results of this procedure are .xys data files generated for each CHARM HD2 array, including both Cy3 and Cy5 intensities, using the NimbleScan feature extraction software (Roche NimbleGen).

Analyze raw data (.xys files) obtained from the CHARM HD2 arrays

Also see http://www.biostat.jhsph.edu/~maryee/charm for additional software details and support.

-

3.Download and install R (http://cran.r-project.org) and Bioconductor (http://bioconductor.org).

- Detailed installation instructions are available at the download Web sites.

-

4.Start R and install the charm and pd.feinberg.hg18.me.hx1 packages by typing the following at the R prompt:

> source(“http://www.bioconductor.org/biocLite.R“) > repos <- c(“http://R-Forge.R-project.org“, biocinstallRepos()) > pkgs <- c(“charm”, “pd.feinberg.hg18.me.hx1”) > install.packages(pkgs=pkgs, repos=repos)

- Lines beginning with > indicate commands to be entered at the R prompt. Help for all commands used in steps 4 to 9 can be accessed within R using the ? command. For example type ?qcReport at the R command prompt to obtain information about the qcReport command.

-

5.

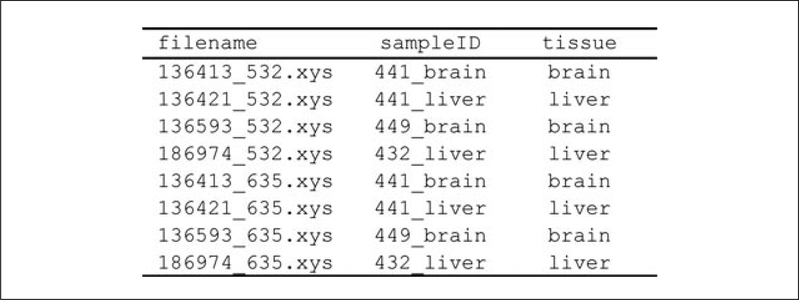

Prepare a tab-delimited sample description file (example shown in Fig. 20.1.2). This can be created in Microsoft Excel and saved using the Save As > Tab Delimited Text option. The sample description file should have one line per channel, i.e., two lines per sample corresponding to the Cyanine-3 (532.xys) and Cyanine-5 (63 5.xys) channel data files. Three columns are required: the .xys file name (denoted by filename in Fig. 20.1.2), asample identifier (denoted by sampleID in Fig. 20.1.2), and a group label (denoted by tissue in Fig. 20.1.2). The names of the columns are arbitrary.

-

6.Read the tab-delimited sample description file created in step 5 (denoted here as sample–description–file.txt) into R by typing the following at the R prompt:

> pd <- read.delim(“sample_description_file.txt”)

-

7.Read raw .xys file data into R by typing the following at the R prompt:

> rawData <- readCharm(files=pd$filename, sampleKey=pd)

-

8.Generate a hybridization quality report to identify outlier arrays with poor signal quality or spatial artifacts by typing the following at the R prompt:

> qual <- qcReport(rawData, file=“qcReport.pdf”)

- The report is saved in PDF format.

-

9.Normalize the data and find differentially methylated regions (DMRs) by typing the following at the R prompt:

> grp <- pData(rawData)$tissue > p <- methp(rawData) > dmr <- dmrFinder(rawData, p=p, groups=grp, compare=c(“brain”, “liver”)) > dmr <- dmrFdr(dmr) > head(dmr$tabs[[“brain-liver”]])

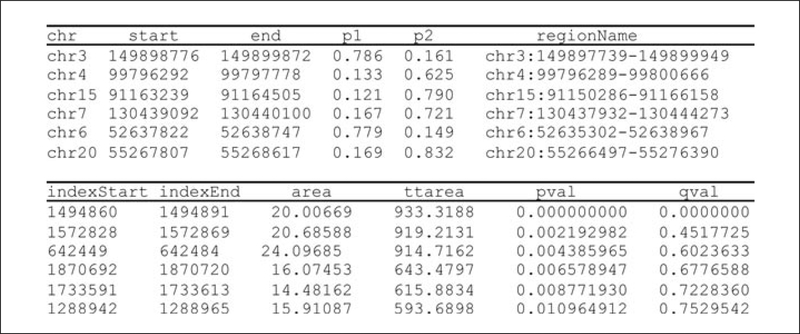

- An example of the output (a table listing DMRs) generated using the commands used above is shown in Figure 20.1.3.

- The dmr object produced by the above commands contains a table of candidate DMRs (example shown in Figure 20.1.3). Each DMR is identified by chromosome and start and end positions (columns 1 to 3). The columns p1 and p2 contain the average percentage methylation in group 1 and group 2 respectively. The last column (qval) indicates the false discovery rate q-value of the DMR. Note that the q-value is not a reliable indicator of statistical significance when there are less than approximately 5 biological replicates in either group.

- See Anticipated Results for interpretation of this information.

Figure 20.1.2.

Tab-delimited sample description file (example).

Figure 20.1.3.

Table listing DMRs (example of output generated using commands in step 9).

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 1

FRACTIONATION OF GENOMIC DNA BY RANDOM SHEARING

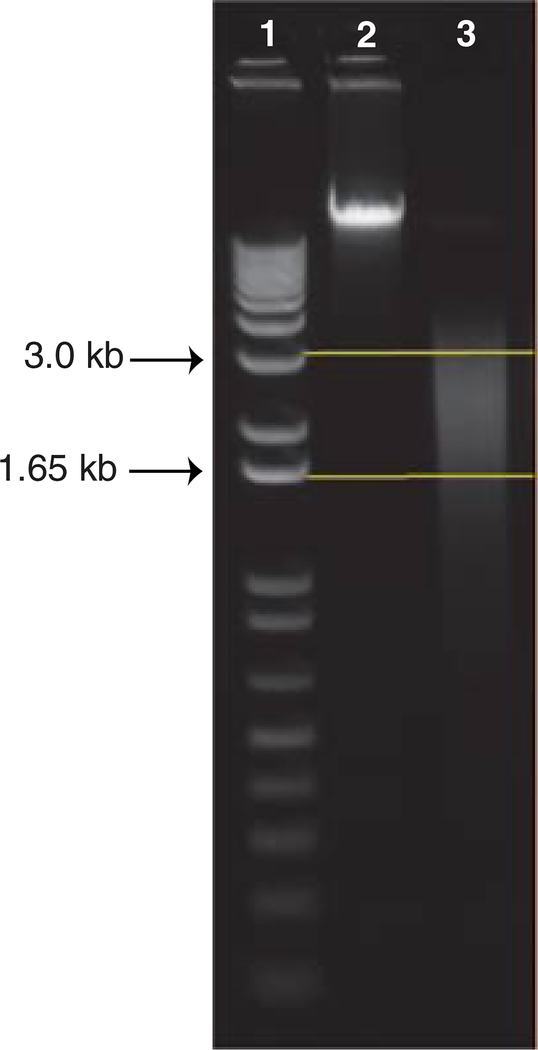

In this protocol, we describe how to randomly shear 5 μg of high-quality and high-molecular-weight genomic DNA (gDNA) from 1.5 kb to 3.0 kb using a HydroShear device (DigiLab, http://www.digilabglobal.com/). The HydroShear uses hydrodynamic forces to randomly shear gDNA to a specified size range. More specifically, the device contracts and causes the gDNA solution to pass through a 0.05-mm diameter orifice in a ruby, located within the shearing assembly. In turn, the flow rate of the solution accelerates forcing the gDNA to stretch and break (Oefner et al., 1996; Thorstenson et al., 1998). Following shearing, the DNA is equally split into two aliquots and is ready for methylation-dependent fractionation. Figure 20.1.4 provides an example of the expected distribution of DNA sizes after shearing has been performed.

Figure 20.1.4.

The expected size distribution, from 1.5 kb to 3.0 kb, of genomic DNA after shearing with a HydroShear device. We ran 500 ng of DNA on a 1% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer for 60 min at 110 volts. Lane 1 contains a 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder with the upper and lower arrows denoting 3.0 kb and 1.65 kb, respectively. Lane 2 contains unsheared, high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA as a reference. Lane 3 contains genomic DNA that was sheared using a standard shearing assembly on a HydroShear device. The two straight horizontal lines denote the expected size distribution of DNA.

Materials

5 μg of high-quality, high-molecular-weight, genomic DNA in 1 × TE buffer (APPENDIX 3B)

1 × TE buffer, pH 7.4 (Quality Biological), filtered prior to use to avoid clogging of the shearing assembly

0.2 M hydrochloric acid (wash solution I), filtered prior to use to avoid clogging of the shearing assembly

0.2 M sodium hydroxide (wash solution II), filtered prior to use to avoid clogging of the shearing assembly

50-ml conical tubes (BD Falcon)

HydroShear device, equipped with a standard shearing assembly and syringe (DigiLab; http://www.digilabglobal.com/)

Allow genomic DNA to equilibrate at room temperature for 30 min and mix well by vortexing prior to shearing.

- Prepare DNA for shearing by aliquotting the following into a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube:

- 5 μg of genomic DNA

- 1 × TE buffer to 100 μl.

- Place an ~20-ml aliquot of wash solution I (0.2 M HCl), wash solution II (0.2 M NaOH), and 1 × TE buffer from the filtered stock into a new 50-ml conical tube.

- These 50-ml-tube aliquots are used to wash the HydroShear device by placing the input tubing on the HydroShear device into the 50-ml tube containing the appropriate solution.

Start the HydroShear software.

- Set the shearing parameters as follows:

- Volume = 100 μl

- Number of cycles = 20

- Speed code = 8.

- Each new standard shearing assembly can generate slightly different fragment sizes. While a speed code of 8 usually results in a DNA size distribution from 1.5 kb to 3.0 kb, we have observed that a range of speed codes, from 7 to 9, produce this distribution, depending on the specific shearing assembly used. Thus, each new standard shearing assembly should be tested with high-quality gDNA to determine the speed-code setting for that particular shearing assembly. This is further discussed below in Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting.

- Select edit wash scheme and set the parameters to:

- Wash solution I (0.2 M HCl), Cycles = 3

- Wash solution II (0.2 M NaOH), Cycles = 3

- Wash solution III (1 × TE buffer), Cycles = 4.

- Check that the machine parameters, provided below, are appropriate for the particular HydroShear model you are using.

- Manual HydroShear Model

- Syringe volume = 500

- Void volume = 15

- Retraction speed = 20

- Auto valve = off

- Automated HydroShear Plus Model

- Syringe volume = 500

- Void volume = 10

- Retraction speed = 30

- Auto valve = on.

- Although these machine parameters result in complete shearing of genomic DNA using the HydroShear devices in our lab, they may not be optimal for every HydroShear device, as each device is custom built upon order. Thus, if any unsheared genomic DNA is present in your sample after using the machine settings provided above, the machine parameters for your particular HydroShear device will need to be optimized to obtain genomic DNA that is completely sheared.

- Begin the shearing process by selecting START under the operation controls tab and follow the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Always perform a wash protocol prior to loading your sample.

- For the manual HydroShear model, after loading your DNA sample, you will be instructed to turn the lever to the output position. Instead, in order to avoid bubbles, you should turn the lever until it is half-way between the input and output (parallel to the syringe) and click “okay.” As the solution rises to the top, the bubble will also rise. Once the bubble rises, quickly move the lever to the output position. Then, continue as instructed until the end of the shearing program.

- Collect the sheared genomic DNA into a new 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube (the recovered volume is typically about 90 μl).

- Repeat step 8 for each sample.

- After the last sample is sheared, be sure to run the wash protocol.

For each sheared sample, bring the total volume back up to 100 μ1 using 1 × TE.

- Split the sheared DNA into two 50-μl aliquots, one labeled MD and the other labeled UT.

- Sheared DNA can be stored at −20° C prior to performing methyl-dependent fractionation.

- MD stands for methyl-depleted; this aliquot, containing 2.5 𝜇g of sheared gDNA, will be treated with McrBC in Support Protocol 2 and will ultimately represent unmethylated CpG sites in the genome. UT stands for untreated; this aliquot will not be treated with McrBC—it represents the input fraction.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 2

METHYL-DEPENDENT FRACTIONATION OF GENOMIC DNA USING McrBC

McrBC is a restriction enzyme that is particularly useful for DNAm analysis because its recognition site, (A/G)mC(N40-3000)(A/G) mC, with an optimal separation of 55–103 base pairs, represents nearly half of all possible 5-methylcytosine nucleotides present in the human genome (Sutherland et al., 1992). The utilization of McrBC for methyl-dependent DNA fractionation was originally described for examination of DNAm in the plant genome (Lippman et al., 2005).

In this protocol, we describe enrichment for unmethylated DNA using McrBC, as recently adapted for the human genome (Ordway et al., 2006,2007). One of the two 50-μl aliquots (the microcentrifuge tube labeled MD from Support Protocol 1, above) will be treated with McrBC, which results in methylated cytosines being cut into smaller fragments. The second 50-μl aliquot (the microcentrifuge tube labeled UT from Support Protocol 1, above) will be mock-digested with 50% glycerol. Hence, it is not digested and represents the total genomic DNA input. Following digestion, both the treated and untreated portions for each sample are fractionated on a high-molecular-weight 1% agarose gel. DNA ranging in size from 1.65 kb to 3.0 kb is extracted from the agarose gel and represents unmethylated and total genomic DNA for methyl-depleted (MD) and untreated (UT) portions, respectively.

Materials

Two 50-μl aliquots of sheared genomic DNA: one labeled UT and the other labeled MD, (Support Protocol 1)

10× NEBuffer2 (NEB2; New England Biolabs)

100 μg/m1 (100×) bovine serum albumin (100 × BSA)

100 mM (100×) guanosine triphosphate (GTP; store in single-use aliquots at —80°C)

10 U/μL McrBC (New England Biolabs): test each new lot on a standard gDNA sample, using the digestion reaction and conditions provided below, to ensure complete digestion prior to use on any experimental samples

50% (w/v) glycerol

50 mg/ml proteinase K

SeaPlaque GTG Agarose (low melting point)

1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE) buffer (see APPENDIX 2D for 50×)

10 mg/ml ethidium bromide stock (APPENDIX 2D)

1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (Invitrogen)

PhiDye (see recipe)

- Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit including:

- Isopropanol

- Buffer QG

- Buffer PE

- Buffer EB

50° and 65°C water bath

500-ml Erlenmeyer flask

Microwave oven

Clean 12-in. × 14-in. gel box with casting tray (USA Scientific)

Clean 8-well, 1.5-mm wide-tooth combs for the 12-in.× 14-in. gel box (USA Scientific)

Kimwipes

Heat-protective glove (“Hotglove”)

Gel imager (e.g., AlphaImager HP; Alpha Innotech, http://www.alphainnotech.com)

Razor blades

Additional reagents and equipment for ethanol precipitation of DNA (APPENDIX 3C; use ammonium acetate as the monovalent cation) and agarose gel electrophoresis (see Ordway et al., 2006, and UNIT 2.7 in this manual)

Set up digestion reactions

-

1.For each 50-μl aliquot of sheared gDNA labeled MD, set up an McrBC digestion reaction in a total volume of 300 μl, with final concentrations as shown below (Ordway et al., 2006):

- 50 pl of sheared gDNA (a total of 2.5 μg from the MD aliquot obtained in Support Protocol 1)

- 1 × NEB2

- 0. 1 mg/ml BSA

- 2 mM GTP

- 100 U McrBC

- Milli-Q water to bring reaction to a total volume of 300 μl.

- Discard any unused portion of 100× GTP to avoid freeze-thawing.

-

2.For each 50-μl aliquot of sheared gDNA labeled UT (see Support Protocol 1), set up a mock digestion reaction in a total volume of 300 μl, with final concentrations as shown below (Ordway et al., 2006):

- 50 μl of sheared gDNA (a total of 2.5 μg from the UT aliquot obtained in Support Protocol 1)

- 1× NEB2

- 0.1 mg/ml BSA

- 2mM GTP

- Add a volume of 50% glycerol that is equivalent to 100 U of McrBC Milli-Q water to bring reaction to a total volume of 300 μl.

- Discard any unused portion of 100× GTP to avoid freeze-thawing.

-

3.

Incubate both the McrBC and mock-digestion reactions at 37°C overnight.

Clean up digestion reactions (Ordway et al., 2006)

-

4.

For each 300-μ1 digestion, add 2.5 μl of 50 mg/ml proteinase K.

-

5.

Place all samples at 50°C for 1 hr to inactivate McrBC.

-

6.

Perform standard ethanol precipitation as described in APPENDIX 3C, Basic Protocol, using ammonium acetate.

-

7.Allow the DNA pellet to air dry for about 15 min, then resuspend in 25 μl of Milli-Q water.

- At this point, DNA can be stored at −20° C.

Size fractionate DNA using agarose gel electrophoresis (Ordway et al., 2006)

-

8.Prepare a 1% high-molecular-weight agarose gel solution by adding 1 g of low-melting-point SeaPlaque GTG agarose to 100 ml of filtered 1× TAE buffer in a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask.

- Each 100-ml agarose gel is sufficient to run eight total digestion reactions (four UT and four MD reactions), representing four samples.

-

9.Place a small Kimwipe in the top of the Erlenmeyer flask and microwave on high for 1 min intervals until the agarose has completely melted and gone into solution.

- Keep a close eye on the solution. if it begins to boil over, stop immediately and stir by swirling the flask using a heat-protective glove. The solution will be clear when the agarose has completely melted.

-

10.Once the agarose gel is no longer steaming, add 40 μg of ethidium bromide (i.e., 4 μ1 of 10 mg/ml ethidium bromide stock) and pour into a clean casting tray containing two 1.5 mm wide-tooth combs.

- CAUTION: Ethidium bromide is carcinogenic! Wear gloves at all times and properly dispose of waste. Also see APPENDIX 2A.

-

11.

For each sample, resolve the MD and UT fractions in adjacent wells by loading 25 μ1 of DNA plus 15 μ1 of PhiDye into each well. In the wells adjacent to each sample, load 1 μg of 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder in 15 μ1 PhiDye (Fig. 20.1.5).

-

12.

Run for 3 to 3.5 hr at a 30 V (constant) in 1× TAE (see Ordway et al., 2007, and UNIT 2.7 in this manual). Proceed immediately to gel extraction and purification of DNA.

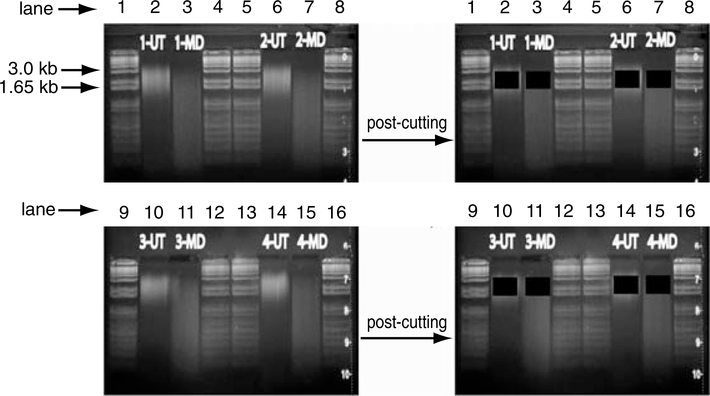

Figure 20.1.5.

Genomic DNA is size fractionated using a high-molecular-weight agarose gel. Mock (UT) and McrBC (MD) digestions were run side by side for 3.5 hr at 30 V. Lanes 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, and 16 contain a 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder. Lanes 2 and 3 contain sheared gDNA from sample 1 that was mock digested (UT) and McrBC-treated (MD), respectively. Lanes 6 and 7 contain sheared gDNA from sample 2 that was mock digested (UT) and McrBC-treated (MD), respectively. Lanes 10 and 11 contain sheared gDNA from sample 3 that was mock digested (UT) and McrBC-treated (MD), respectively. Lanes 14 and 15 contain sheared gDNA from sample 4 that was mock digested (UT) and McrBC-treated (MD), respectively. Images on the left represent the agarose gel prior to extracting DNA and the images on the right show the agarose gel image after extracting DNA ranging in size from 1.65 to 3.0 kb. Well 1, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 2, Sample 1-UT; Well 3, Sample 1-MD; Well 4, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 5, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 6, Sample 2-UT; Well 7, Sample 2-MD; Well 8, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 9, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 10, Sample 3-UT; Well 11, Sample 3-MD; Well 12, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 13, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg); Well 14, Sample 4-UT; Well 15, Sample 4-MD; Well 16, 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder (1 μg).

Extract DNA from gel and purify (Ordway et al., 2006)

-

13.

Take and save an image of the agarose gel using a gel imager set to long-wave UV.

-

14.For each sample, excise gel fragments that range in size from 1.65 kb to 3.0 kb using a clean razor blade and the 1 Kb Plus DNA Ladder as a guide.

- It is imperative that both the UT and MD fractions be cut horizontally at the exact same location; therefore, use a blade that spans across both wells. Using one blade, both wells can be cut at precisely the same location in a single movement. Both pre- and post-gel-cutting images are shown in Figure 20.1.5 as a reference.

-

15.

Transfer each rectangular gel slice to a 2.0-ml microcentrifuge tube.

-

16.Using a clean blade, repeat steps 14 and 15 for each sample.

- At this point, gel slices can be stored at −20° C overnight.

-

17.Purify DNA from the gel using the Qiagen Gel Extraction Kit according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

- Elute in 30 μl of elution buffer. Purified DNA can be stored at −20° C.

- Since methylated DNA fragments were eliminated from the MD portion after agarose gel fractionation, a substantially lower yield is expected for the MD fraction as compared to the UT fraction.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 3

WHOLE-GENOME AMPLIFICATION

Since the minimum amount of DNA required for cyanine dye labeling and hybridization to a CHARM microarray is 3.5 μg, much more than the amount recovered from gel fractionation and extraction, whole-genome amplification is performed to obtain the required amount for labeling. Here we describe how to perform whole-genome amplification (WGA) using DNA that was extracted and purified from the agarose gel in Support Protocol 2.

Materials

30 ng of excised, purified DNA from step 17 of Support Protocol 2 for both MD and UT fractions

- GenomePlex Complete Whole Genome Amplification (WGA2) kit (Sigma) including:

- 10× fragmentation buffer

- 1× library preparation buffer

- Library stabilization solution

- Library preparation enzyme

- 10× amplification master mix

- WGA DNA polymerase

- Nuclease-free water

- QiaQuick PCR Purification Kit including:

- Buffer PB

- Buffer PE

- Buffer EB

Additional reagents and equipment for spectrophotometrically quantitating DNA (APPENDIX 3D)

Carry out whole-genome amplification of fractionated, gel-purified DNA

-

1.Perform whole-genome amplification using the GenomePlex Complete Whole Genome Amplification (WGA2) Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Start with 30 ng of DNA purified in Support Protocol 2, step 17, for both the MD and UT fractions.

- Amplified DNA can be stored at −20° C or immediately cleaned up using the QiaQuick purification kit.

Purify whole-genome amplified material

-

2.

Purify amplified DNA using the QiaQuick PCR purification kit and protocol according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

-

3.Quantitate the amplified DNA using a conventional spectrophotometer or Nanodrop instrument as described in APPENDIX 3D.

- For each MD and UT fraction, a total of 3.5 𝜇g per is required for cyanine dye labeling. At this point, DNA can be stored at –20° C.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 4

DETERMINING McrBC SPECIFICITY AND UNMETHYLATED DNA ENRICHMENT

After fractionation, extraction, and amplification of samples, it is important to run quantitative real-time PCR to evaluate the specificity of McrBC in the digestion reaction. In this protocol, we describe how to perform quantitative real-time PCR using control regions representing methylated and unmethylated regions of the genome to determine enrichment for unmethylated cytosines and nonspecific (STAR) McrBC activity, respectively. We choose to use these controls because they have been evaluated in previous studies of DNA methylation in human tissues (Ordway et al., 2007). Specifically, GAPDH primers represent 14 CpG sites, located within a CpG island associated with the GAPDH promoter region, which are unmethylated in most differentiated somatic tissues; using these primers evaluates STAR activity. In contrast, examination of 6 CpG sites, located about 300 bp from a CpG island and within the promoter region of the HIST1H2BA gene, enables assessment of the depletion of methylated sequences, as this locus is densely methylated in all tissues except the testes (Choi and Chae, 1991).

Relative differences between the untreated (UT) and methyl-depleted (MD) fractions are calculated by computing the delta CT as described in Livak and Schmittgen (2001). For each sample, we expect the difference in CT values for GAPDH between the untreated (UT) and methyl-depleted (MD) fractions (UT) to be very small (<1.0). However, for the HIST1H2BA locus, we expect the difference in CT values between the untreated and methyl-depleted fractions to be large (at least a delta CT > 2.0). An example of quantitative real-time PCR analysis is provided at the end of this protocol.

NOTE: If you expect global hypomethylation in any of your experimental samples, you would expect marginal or no differences in CT values for HIST1H2BA, depending on the extent of hypomethylation.

NOTE: Although we use Fast SYBR Green master mix, you can substitute with a master mix and cycling conditions appropriate for the quantitative real-time PCR machine you are using.

Materials

For each sample, 60 ng of untreated DNA (UT fraction) obtained after whole-genome amplification (Support Protocol 3), at a concentration of 5 ng/μl

For each sample, 60 ng of McrBC-treated DNA (MD fraction) obtained after whole-genome amplification (Support Protocol 3), at a concentration of 5 ng/μl

Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems)

- Quantitative real-time PCR primers for the human genome (Ordway et al., 2007):

- GAPDH forward primer: TCTTGAGGCCTGAGCTACGTG

- GAPDH reverse primer: CCCGTCCTTGACTCCCTAGTGT

- GAPDH target sequence (5’ to 3’): CCTGCTGCCCACAGTCCAGTCCTGGG-AACCAGCACCGATCACCTCCCATCGGGCCAATCTCAGTCCCTT-CCCCCCTACGTCGGGGCCCACACGCTCGGTGCGTGCCCAGTTGAA-CCAGGCGGCTGCGGAAAAAAAAAAGCGGGGAGAAAGTAGGG-CCCGGCTACTAGCGGTTTTACGGGCG

- HIST1H2BA forward primer: AGTGCTGTGTAACCCTGGAAAA

- HIST1H2BA reverse primer: ACTCTCCTTACGGGTCCTCTTG

- HIST1H2BA target sequence: AGTGCTGTGTAACCCTGGAAAAGAACCGT-GTAACGCTGCAGAAGTGTGTGGTAGCTATGCCGGAGGTGTCAT-CTAAAGGTGCTACCATTTCCAAGAAGGGCTTTAAGAAAGCTGTCG-TTAAGACCCAGAAAAAGGAAGGCAAAAAGCGCAAGAGGACCCGT-AAGGAGAGT

Milli-Q water

384- or 96-well optical plates

Optical plate seals

ABI 7900 HT real-time PCR machine

Set up quantitative real-time PCR assays

-

1.For each sample, prepare, in triplicate, the reaction provided below, on ice, in an individual well of an optical plate (25 μl/well total volume).

- 2.0 μl 5 ng/μl DNA

- 12.5 μl Fast SYBR Green Master Mix

- 1.25 μl 6.0 μM forward primer

- 1.25 μl 6.0 μM reverse primer

- 8.0 μl water.

-

2.

Seal plate with optical film.

-

3.Set up the run on the real-time machine using the following thermal cycling program for Fast SYBR Green Master Mix:

1 cycle: 20 sec 95°C (initial denaturation) 40 cycles: 1 sec 95°C (denaturation) 20 sec 60°C (annealing).

Analyze data from quantitative real-time PCR assays

Also see UNIT 11.10 for additional detail on real-time PCR calculations.

-

4.Analyze and export threshold cycle values (CT) from the real-time PCR machine.

- This must be performed on the real-time PCR instrument.

-

5.Calculate the mean CT value across triplicates for both GAPDH and HIST1H2BA assays.

- Steps 5 to 7 can easily be performed using Microsoft Excel.

-

6.

For both GAPDH and HIST1H2BA, compute the difference between methyl-depleted and untreated fractions (CT methyl-depleted - CT untreated) and record this as the delta CT (ΔCT).

-

7.Decide if the sample passes quality control.

- For each sample, if the ΔCT valuefor GAPDH is ≤2.0andthe ΔCT valuefor HIST1H2BA is ≥2.0, the sample passes quality control. Otherwise, if either GAPDH or HIST1H2BA do not meet these criteria, the sample fails quality control.

- An example ofquality-control analysis is shown in Table 20.1.1.

Table 20.1.1.

Example of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Results for GAPDH and HIST1H2BA Assays in Four Tissue Samples

| GAPDHa |

HIST1H2BAb |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Untreated Ctc | Methyl-depleted Ctd | ΔCte | Resultf | Untreated Ctc | Methyl-depleted Ctd | ΔCte | Resultf |

| Liver | 22.76 | 23.13 | 0.37 | Pass | 25.68 | 29.88 | 4.20 | Pass |

| Spleen | 23.12 | 22.89 | 0.23 | Pass | 24.43 | 25.46 | 1.03 | Fail |

| Brain | 22.56 | 21.76 | 0.8 | Pass | 24.11 | 29.65 | 5.54 | Pass |

| Heart | 23.24 | 28.11 | 4.87 | Fail | 23.98 | 29.34 | 5.36 | Pass |

GAPDH, unmethylated CpG control for McrBC specificity.

HIST1H2BA, methylation control for evaluation of methyl depletion.

For each sample, mean triplicate threshold cycle reported by quantitative real-time machine for the untreated (UT) fraction.

For each sample, mean triplicate threshold cycle reported by quantitative real-time machine for the McrBC-treated (MD) fraction.

Difference in threshold cycle between untreated and methyl-depleted fractions. ΔCT = CT methyl-depleted – CT untreated.

Quality assessment. Pass denotes proceed with cyanine-dye labeling. Fail denotes do not proceed with cyanine-dye labeling.

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS

Use deionized, distilled water in all recipes and protocol steps. For common stock solutions, see APPENDIX 2D; for suppliers, see SUPPLIERS APPENDIX.

PhiDye

Prepare in deionized, distilled H2O:

0.2 g/ml Ficoll 400

1% (w/v) sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; fresh in crystalline/powder form)

0.1 M disodium EDTA

A few mg (per 50 ml) Orange G (e.g., Sigma; just to color to your preferred level of darkness).

Store in aliquots up to 6 months at – 20°C

COMMENTARY

Background information

Recent technological advances have enabled us to begin to move from examination of DNAm at the single-gene level to studying methylation across the genome (Callinan and Feinberg, 2006). Although microarray and sequencing technologies provide a mechanism for the examination of thousands or even millions of CpG sites across the genome, many of these methods are limited by throughput, cost, sensitivity, and specificity. For example, the cost of sequencing is hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single sample; thus it is cost-prohibitive for studies that involve examination of more than a few samples.

Most microarray-based approaches focus only on CpG-island and promoter regions because of assumptions that functionally important changes in DNAm occur in promoter and CpG-island regions. However Comprehensive High-Throughput Arrays for Relative Methylation (CHARM), recently developed and described in this unit, offers a high-throughput approach to measure DNAm across the genome (Irizarry et al., 2008) in a sensitive, specific, and cost-effective manner. While at the present time CHARM offers a practical, cost-effective approach to measure DNAm in a large number of samples, the cost of sequencing is rapidly decreasing; thus, it is likely to become cost-effective on large numbers of samples over the next decade.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

Genomic DNA isolation and random shearing of gDna

In our lab, we use the MasterPure genomic DNA purification kit (EpiCentre Technologies) to isolate genomic DNA; however, in principle, any method (see APPENDIX 3B) that provides high-quality and high-molecular-weight gDNA can be used for McrBC-based fractionation as described in this unit. Currently, there are several methods available for shearing of genomic DNA, including point-sink hydrodynamic flow-based shearing (Oefner et al., 1996; Thorstenson et al., 1998), represented by the HydroShear device, which we describe in detail in this unit; nebulization; and sonication. There are three critical parameters to consider when choosing a shearing method: (1) the shearing method needs to completely shear all genomic DNA, with no high-molecular-weight gDNA remaining; (2) shearing must be completely random, with no sequence-specific shearing biases; and (3) the shearing method should result in a tight distribution of gDNA ranging in size from 1.5 kb to 3.0 kb. Although we use the HydroShear device for CHARM analysis because it meets all of these critical parameters, other shearing methods, such as sonication using a Covaris E-series device (http://www.covarisinc.com/) offer the potential for an automated, higher-throughput solution to gDNA shearing. While, in principle, alternative devices may be suitable for CHARM analysis, it is important to note that they have not been rigorously tested and may result in incomplete shearing of gDNA, sequence-specific shearing biases, or improper size distributions. Thus, until a more rigorous comparison of alternative shearing methods is performed, we suggest using the HydroShear device.

Fractionation and amplification of McrBC and mock-digested DNA

In this unit, we describe enrichment for unmethylated DNA using an McrBC-based fractionation method. A critical component of this enrichment method is the precise extraction of DNA across the untreated (UT) and methyl- depleted (MD) portions of each sample during molecular-weight fractionation on a 1% agarose gel. It is imperative that extraction of DNA from the UT and MD fractions, for each sample, occur at the exact same size distribution. This is easily achieved by obtaining a razor blade or coverslip that spans both UT and MD lanes and using one swift movement to cut both lanes at the same time.

The labeling procedure for NimbleGen HD2 CHARM arrays requires a minimum starting amount of fractionated DNA equal to 3.5 μg. Since obtaining this amount of DNA after fractionation would require randomly shearing hundreds of micrograms of gDNA for each sample—an unrealistic starting amount for most biological samples—we utilize whole-genome amplification (WGA) after fractionation to obtain the required 3.5 μg of DNA. Thus, WGA enables examination of samples with as little as a few micrograms of gDNA. The GenomePlex WGA method has been used for a variety of applications (Barker et al., 2004; Gribble et al., 2004; Buffart et al., 2009), and genotyping studies have reported high concordance (>99.8%) between genotyping calls from unamplified and whole-genome-amplified genomic DNA (Barker et al., 2004). Thus, DNA amplified using WGA is suitable for genomic studies, minimizes nonspecific amplification artifacts, and is highly representative of genomic DNA. To obtain an unbiased, linear amplification, it is important to use between 10 ng and 100 ng of DNA; therefore, in Basic Protocol we use 30 ng of extracted DNA in the whole-genome amplification procedure for both UT and MD fractions.

CHARM analysis

In a recent comparison study, we identified biases with respect to CpG density and fragment size for several common methods used to examine DNAm across the genome, including methylated DNA immunoprecipitation (MeDIP), HpaII tiny-fragment enrichment by ligation-mediated PCR (HELP), and McrBC (Irizarry et al., 2008). However, we were able to largely overcome these biases by coupling McrBC fractionation to a novel analytical approach, which we term CHARM (Irizarry et al., 2008). CHARM uses a customized NimbleGen HD2 tiling array that is not limited to CpG-island and promoter regions, enabling application of a novel normalization and smoothing algorithm. In situations with at least six biological replicates per experimental group, it is possible to rank candidate DMRs by statistical significance in terms of false discovery rates (FDR) as described in Irizarry et al. (2009). Using an FDR equal to 5%, we have never observed contradictory results with bisulfite pyrosequencing, an independent, highly quantitative method to measure DNAm at single nucleotide resolution. Thus, an FDR of 5% provides a meaningful threshold for significance in a larger set of samples.

Anticipated Results

After performing methyl-dependent DNA fractionation followed by CHARM array hybridization and analysis, regions with differential methylation between two types of samples, e.g., differences in methylation between cancer and normal samples, are expected to be identified. For experiments that contain more than six samples per phenotype, a false discovery rate (FDR) can be calculated to determine the significance of the differentially methylated regions (DMRs). While it is important to validate microarray findings using a highly quantitative independent method, in previous experiments, every DMR assayed using quantitative bisulfite pyrosequencing was confirmed to be differentially methylated when we used an FDR equal to 5% (Irizarry et al., 2009). Since an FDR does not provide a reliable measure of significance in small sample sets, it is important to note that comparisons with fewer than six samples per phenotype need to undergo substantial downstream validation using a highly quantitative, single-nucleotide-resolution method, such as bisulfite pyrosequencing.

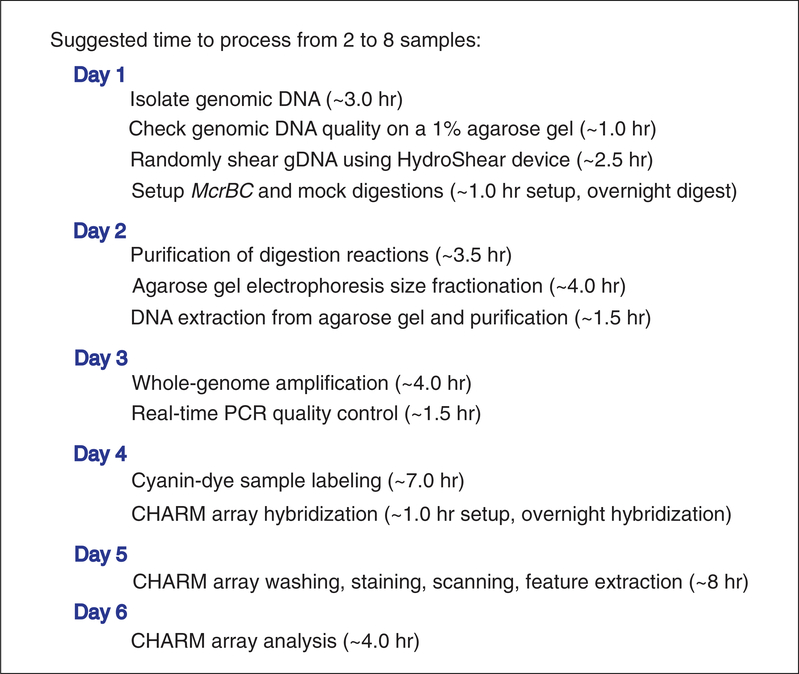

Time Considerations

The amount of time required to process large batches of samples (greater than 12) can vary widely depending on availability of equipment. Therefore, in this section, we will describe the time it takes to process a single gDNA sample, from shearing through CHARM analysis, current throughput limitations, and how to overcome bottlenecks in throughput. As shown in Figure 20.1.6, it takes about 6 days to complete fractionation, CHARM labeling and array hybridization, and CHARM analysis, as described in this unit.

Figure 20.1.6.

Suggested timeline for CHARM analysis of DNA methylation.

The first limitation in sample throughput is random shearing of genomic DNA using a HydroShear apparatus, with the manual HydroShear device taking about 20 min per sample to shear. However, utilization of the newer automated HydroShear device and running multiple devices in parallel enables increased throughput with minimal user intervention. Thus, use of multiple automated HydroShear devices can substantially decrease the time it takes to process a large number of samples in Basic Protocol.

Since each agarose gel electrophoresis apparatus is capable of fractionating four samples at a time, simply purchasing additional multiple gel boxes enables additional samples to be processed in the same amount of time (~4.5 hr).

Lastly, CHARM array hybridization, washing, and scanning throughput is dependent on the number of hybridization stations and scanners available. Again, simply increasing the number of stations and scanners can substantially increase the sample throughput.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIH Grant P50HG003233 (A.P.F.).

Literature Cited

- Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, and Zoghbi HY 1999. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet 23:185–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DL, Hansen MS, Faruqi AF, Giannola D, Irsula OR, Lasken RS, Latterich M, Makarov V, Oliphant A, Pinter JH, Shen R, Sleptsova I, Ziehler W, and Lai E 2004. Two methods of whole-genome amplification enable accurate genotyping across a 2320-SNP linkage panel. Genome Res. 14:901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffart TE, van Grieken NC, Tijssen M, Coffa J, Ylstra B, Grabsch HI, van de Velde CJ, Carvalho B, and Meijer GA 2009. High resolution analysis of DNA copy-number aberrations of chromosomes 8, 13, and 20 in gastric cancers. Virchows Arch. 455:213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callinan PA and Feinberg AP 2006. The emerging science of epigenomics. Hum. Mol. Genet 15:R95–R101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YC and Chae CB 1991. DNA hypomethylation and germ cell-specific expression of testis-specific H2B histone gene. J. Biol. Chem 266:20504–20511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP 2009. Genome-scale approaches to the epigenetics of common human disease. Virchows Arch. 456:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg AP and Tycko B 2004. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4:143153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, Ellis B, Gautier L, Ge Y, Gentry J, Hornik K, Hothorn T, Huber W, Iacus S, Irizarry R, Leisch F, Li C, Maechler M, Rossini AJ, Sawitzki G, Smith C, Smyth G, Tierney L, Yang JY, and Zhang J 2004. Bioconductor: Open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 5:R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble S, Ng BL, Prigmore E, Burford DC, and Carter NP 2004. Chromosome paints from single copies of chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 12:143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Carvalho B, Wu H, Brandenburg SA, Jeddeloh JA, Wen B, and Feinberg AP 2008. Comprehensive high-throughput arrays for relative methylation (CHARM). Genome Res. 18:780–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irizarry RA, Ladd-Acosta C, Wen B, Wu Z, Montano C, Onyango P, Cui H, Gabo K, Rongione M, Webster M, Ji H, Potash JB, Sabunciyan S, and Feinberg AP 2009. The human colon cancer methylome shows similar hypo- and hypermethylation at conserved tissue- specific CpG island shores. Nat. Genet 41:178186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippman Z, Gendrel AV, Colot V, and Martienssen R 2005. Profiling DNA methylation patterns using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25:402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, Jia P, Assadzadeh A, Flanagan J, Schumacher A, Wang SC, and Petronis A 2008. Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet 82:696–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oefner PJ., Hunicke-Smith SP, Chiang L, Dietrich F, Mulligan J, and Davis RW 1996. Efficient random subcloning of DNA sheared in a recirculating point-sink flow system. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:3879–3886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway JM, Bedell JA, Citek RW, Nunberg A, Garrido A, Kendall R, Stevens JR, Cao D, Doerge RW, Korshunova Y, Holemon H, McPherson JD, Lakey N, Leon J, Martienssen RA, and Jeddeloh JA 2006. Comprehensive DNA methylation profiling in a human cancer genome identifies novel epigenetic targets. Carcinogenesis 27:2409–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway JM, Budiman MA, Korshunova Y, Maloney RK, Bedell JA, Citek RW, Bacher B, Peterson S, Rohlfing T, Hall J, Brown R, Lakey N, Doerge RW, Martienssen RA, Leon J, McPherson JD, and Jeddeloh JA 2007. Identification of novel high-frequency DNA methylation changes in breast cancer. PLoS One 2:e1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD 2003. The positive false discovery rate: A Bayesian interpretation and the q-value. Ann. Stat 31:2013–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland E, Coe L, and Raleigh EA 1992. McrBC: A multisubunit GTP-dependent restriction endonuclease. J. Mol. Biol 225:327–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorstenson YR, Hunicke-Smith SP, Oefner PJ., and Davis RW 1998. An automated hydrodynamic process for controlled, unbiased DNA shearing. Genome Res. 8:848–855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YH, Dudoit S, Luu P, Lin DM, Peng V, Ngai J, and Speed TP 2002. Normalization for cDNA microarray data: A robust composite method addressing single and multiple slide systematic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]