Abstract

Background and study aims EUS-guided gastroenterostomy (GE) is a novel, minimally invasive endoscopic procedure for the treatment of gastric outlet obstruction (GOO). The direct-EUS-GE (D-GE) approach has recently gained traction. We aimed to report on a large cohort of patients who underwent DGE with focus on long-term outcomes.

Patients and methods This two-center, retrospective study involved consecutive patients who underwent D-GE between October 2014 and May 2018. The primary outcomes were technical and clinical success. Secondary outcomes were adverse events (AEs), rate of reintervention, procedure time, time to resume oral diet, and post-procedure length of stay (LOS).

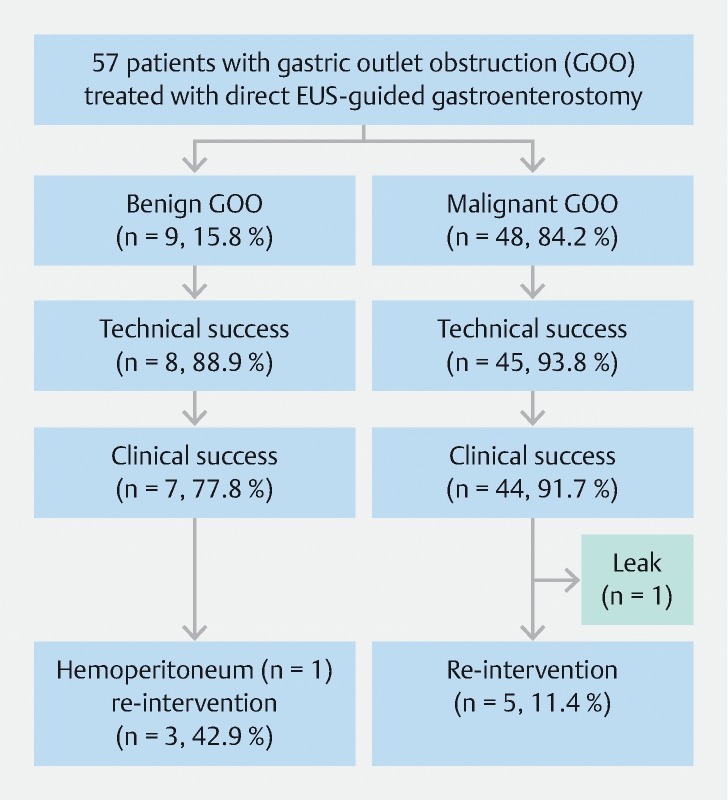

Results A total of 57 patients (50.9 % female; median age 65 years) underwent D-GE for GOO. The etiology was malignant in 84.2 % and benign in 15.8 %. Technical success and clinical success were achieved in 93 % and 89.5 % of patients, respectively, with a median follow-up of 196 days in malignant GOO and 319.5 days in benign GOO. There were 2 (3.5 %) AEs, one severe and one moderate. Median procedure time was 39 minutes (IQR, 26 – 51.5 minutes). Median time to resume oral diet after D-GE was 1 day (IQR 1 – 2 days). Median post D-GE LOS was 3 days (IQR 2 – 7 days). Rate of reintervention was 15.1 %.

Conclusions D-GE is safe and effective in management of both malignant and benign causes of GOO. Clinical success with D-GE is durable with a low rate of reintervention based on a long-term cohort.

Introduction

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) can result from benign and malignant causes and present with nausea, vomiting, early satiety and weight loss 1 . When endoscopic balloon dilation fails for benign GOO, the other treatment modalities are enteral stenting and surgical bypass 2 . Limited data are available to support regular use of fully-covered self-expandable metal stent (FCSEMS) in benign GOO and the devices carry high migration rates 3 4 5 . Surgery is invasive and associated with significant morbidity such as delayed gastric emptying, prolonged hospital stay and increased cost 6 7 .

Malignant GOO has been traditionally treated with duodenal uncovered/partially covered SEMS or surgical gastrojejunostomy. The latter provides excellent luminal patency but with the limitations mentioned above 8 . The major limitation of endoscopic luminal SEMS is limited patency due to tumor and/or soft tissue ingrowth/overgrowth 9 10 .

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy (EUS-GE) is a novel, minimally invasive endoscopic procedure that potentially offers long-lasting luminal patency without risk of tumor ingrowth/overgrowth, while avoiding surgical morbidity 9 10 11 12 . Several techniques have been used to perform EUS-GE but mainly include a balloon-assisted approach 10 12 13 and a direct puncture approach 11 14 , the latter being first described by our group. Direct EUS-GE (D-GE) has the advantage of being faster. The aims of this study were to report the largest clinical experience with D-GE in terms of technical and clinical success, adverse events (AEs) and rate of reintervention.

Patients and methods

This was a retrospective study of patients who underwent D-GE at two tertiary academic centers (Johns Hopkins Hospital, JHH; and Virginia Mason, VM) between October 2014 and May 2018, with follow-up until October 2018. Consecutive patients who underwent D-GE for malignant and benign GOO were included. Exclusion criteria were: 1) age under 18 years; 2) no post-procedural follow-up; and 3) history of a balloon-assisted approach for EUS-GE. A total of 11 patients have been reported in prior publications 9 11 15 . Data from electronic medical records were abstracted and included demographics, etiology of GOO, diet tolerance according to the GOO scoring system (score of 0 represents no oral intake, 1 represents liquid diet only, 2 represents soft solids, and a score of 3 represents low-residue or full diet) 16 , site of obstruction, prior endoscopic stenting or dilation, procedure time, type, size and number of stent(s) used, technical and clinical success, time to oral intake, post-procedure length of stay, need for reinterventions, and AEs. Severity of AEs was graded according to the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) lexicon 17 . The institutional review boards (IRB) at both centers approved this study and the retrospective review of this data. IRB approvals were the following: Johns Hopkins Hospital IRB00080255 with initial approval date November 3, 2015 and expiration date August 5, 2019; and Virginia Mason Medical Center IRB 16115 with initial approval date December 7, 2016 and expiration date December 7, 2020.

Study endpoints and definitions

Technical success was defined as adequate positioning and deployment of the stent as determined endoscopically and radiographically. Clinical success was defined as the ability to tolerate at least a full liquid diet during follow-up. Primary endpoints were the rate of technical and clinical success. In patients who achieved clinical success but later developed symptoms concerning for recurrent GOO, a repeat upper endoscopy was performed to evaluate stent patency. Secondary endpoints were rate and severity of AEs, rate of reintervention, procedure time, time to resume oral diet, and post-procedure length of stay (LOS).

Direct EUS-GE technique

We followed the technique of D-GE previously described by our group ( Video 1 ) 9 11 14 15 . After informed consent was obtained, including explaining the off-label use of a lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS), all patients received pre-procedure intravenous antibiotics (most commonly a quinolone or cefoxitin). EUS-GE was performed in an endoscopy unit or an operating room under general anesthesia, given risk of aspiration with GOO. Procedures were performed by two experienced pancreaticobiliary endoscopists with or without trainee involvement. An adult forward-viewing gastroscope (GIF-HQ190; Olympus America, Center Valley, Pennsylvania, United States) was advanced to the site of the obstruction ( Fig. 1 ), and, if feasible, traversing it to allow efficient infusion of approximately 500 mL of fluid (sterile water and methylene blue with or without contrast) to distend the downstream duodenum and jejunum ( Fig. 1 ). If the obstruction was not traversable, dyed saline was injected either through the working channel of the endoscope or through an ERCP stone retrieval balloon/7 French nasobiliary catheter that were advanced past the obstruction. Under fluoroscopic and EUS-guidance, an optimal area of a small bowel loop adjacent to the stomach was then identified with a therapeutic linear echoendoscope (GF-UCT180; Olympus America) ( Fig. 2 ). To ensure the visualized bowel via EUS was the small bowel and not the transverse colon, a “finder” needle, 19-gauge or 22-gauge, was used for initial puncture and methylene blue aspirated to confirm the target ( Video 1 ). Our practice is not to place a guidewire via the lumen of the finder needle to theoretically reduce risk of stent misdeployment as the guidewire is believed to push the jejunum away from the stomach. This was followed by direct advancement and deployment of a cautery-enhanced LAMS (Hot-AXIOS; Boston Scientific Corporation Inc, Natick, Massachusetts, United States) to create the gastroenterostomy ( Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 ).

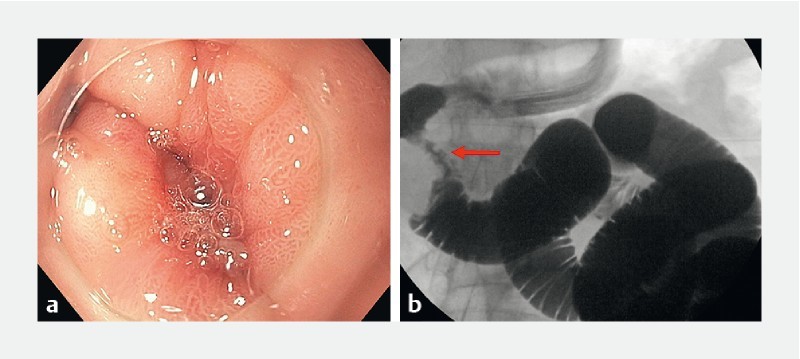

Fig. 1.

Site of duodenal obstruction (arrow) in a patient with pancreatic head ductal adenocarcinoma. Infusion of sterile water, methylene blue and contrast in order to distend the downstream duodenum and jejunum.

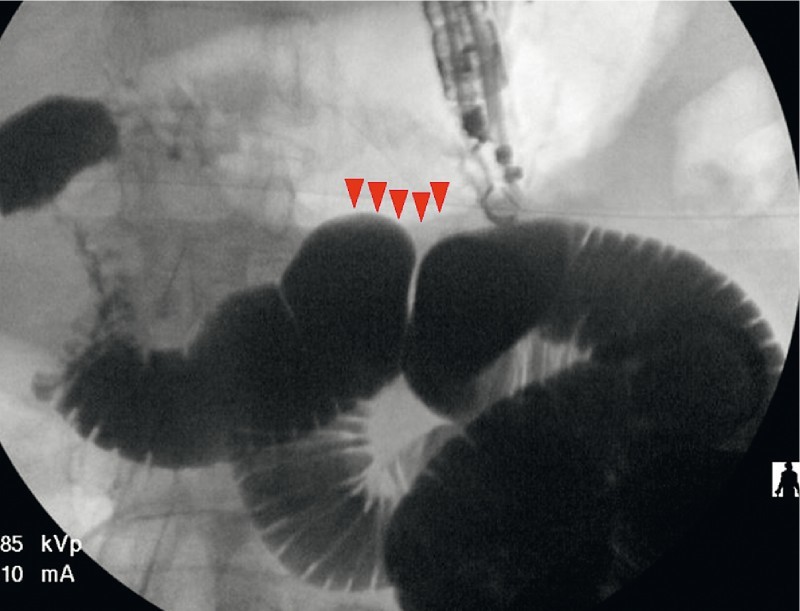

Fig. 2.

An optimal area (arrowheads) of a small bowel loop adjacent to the stomach was identified with a therapeutic linear echoendoscope aided by fluoroscopy.

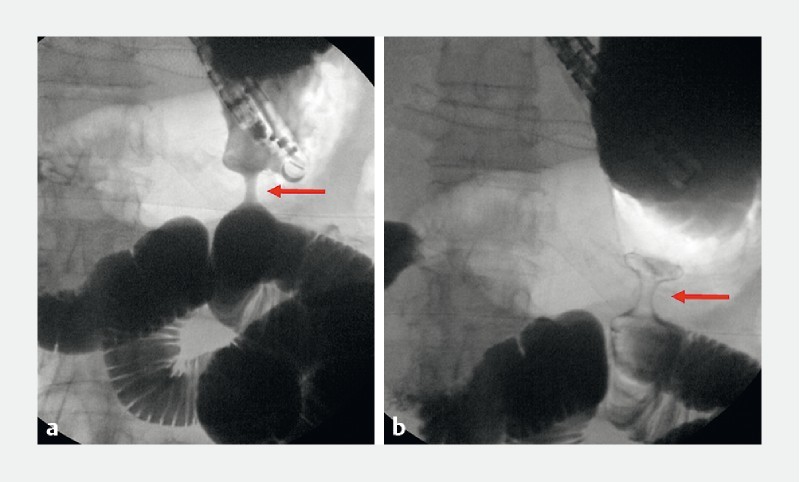

Fig. 3.

Fluoroscopic view of a deployed cautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent (arrows).

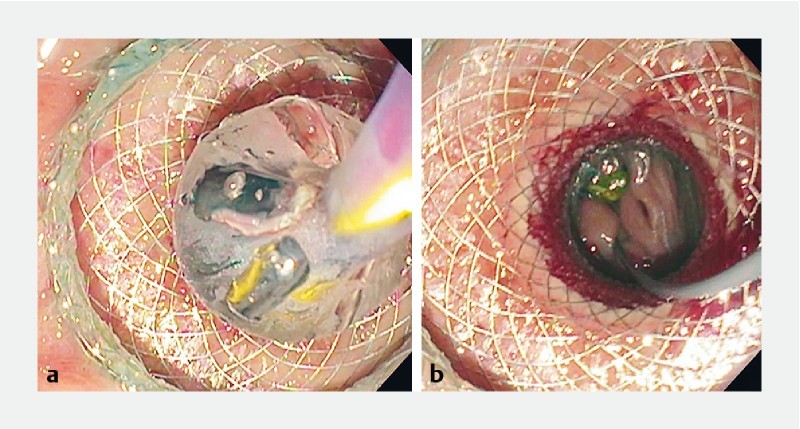

Fig. 4.

Endoscopic view of a deployed cautery-enhanced lumen-apposing metal stent and dilation of the stent lumen. The small bowel was visualized through the lumen of the stent.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation for data with normal distribution, or median and interquartile range for data with skewed distribution. Categorical variables were reported as proportions and 95 % confidence intervals (CI), with inferential analysis performed using chi-square testing.

Results

Characteristics of the study cohort

Sixty-seven patients underwent EUS-GE during the study period, of whom 10 were excluded because a balloon-assisted approach was used for EUS-GE. A total of 57 patients (50.9 % female, median age of 65 years) underwent D-GE during the study period.Forty-two cases (73.7 %) were performed at JHH, while the remaining 15 (26.3 %) were performed at VM. D-GE was performed in 48 patients (84.2 %) with malignant etiologies and 9 patients (15.8 %) with benign etiologies. Malignant etiologies included pancreatic cancer (n = 34, 59.6 %), metastatic cancer (n = 8, 14 %), duodenal/ampullary cancer (n = 4, 7 %), and cholangiocarcinoma (n = 2, 3.5 %). Benign etiologies included peptic stricture (n = 2, 3.5 %), surgical anastomotic stricture (n = 2, 3.5 %), superior mesenteric artery syndrome (n = 1, 1.7 %), small bowel Crohn’s disease (n = 1, 1.7 %), severe adhesion (n = 1, 1.7 %), severe intramural duodenal hematoma from acute pancreatitis (n = 1, 1.7 %), and caustic injury (n = 1, 1.7 %). The majority of patients presented with nausea and vomiting (n = 49, 86 %) with inability to tolerate an oral diet or tolerating only a clear liquid diet (n = 54, 94.7 %). Compared to patients with benign GOO, patients with malignant GOO had worse baseline GOO scores (29/48 patients (60.4 %) with complete intolerance to any oral diet versus 5/9 (55.6 %), P = .04, respectively). Sites of obstruction were prepylorus/pylorus (n = 5, 8.8 %), duodenal bulb (n = 10, 17.5 %), second portion of the duodenum (n = 22, 38.6 %), third portion of the duodenum (n = 13, 22.8 %), fourth portion of the duodenum (n = 3, 5.3 %), and jejunum (n = 4, 7 %).

Primary outcomes

Technical success was achieved in 53/57 patients (93 %) ( Table 1 and Fig. 5 ). There were four technical failures due to absence of a small bowel loop in close proximity to the stomach; one of those patients had pancreatic cancer and intervening colon without a safe window for EUS-GE and was treated with enteral stenting; a second patient only had an ileal loop adjacent to the stomach and EUS-GE was deemed unsuitable as it would cause diarrhea, and that patent was later treated with a venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; a third patient had a large mass and ascites from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma displacing small bowel, and was treated with a venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; a fourth patient had peptic stricture and D-GE failed due to altered small bowel anatomy and possible internal hernia. The stricture was then treated with balloon dilation.

Table 1. Clinical outcomes of direct EUS-guided gastroenterostomy.

| Outcomes | N (%) | Treatment failures and adverse events (n) |

| Technical success | 53/57 (93) | Dilation of peptic stricture (1) Venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (2) Enteral stent (1) |

| Clinical success | 51/57 (89.5) | Laparotomy for leakage at the LAMS site (1) Venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (1) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Moderate adverse event | 1/57 (1.7) | Hemoperitoneum with negative angiogram (1) |

| Severe adverse event | 1/57 (1.7) | Laparotomy for leakage at the LAMS site (1) |

| Recurrence requiring reintervention | 8/53 (15.1) | Venting percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (5) Food disimpaction from LAMS lumen (2) Total parenteral nutrition for downstream jejunal cancer (1) |

Fig. 5.

Flow chart of patients with gastric outlet obstruction who underwent direct EUS-guided gastroenterostomy.

The obstruction was traversable with an adult gastroscope in 16 patients (28.1 %). All patients received infusion of mixed contrast, saline and methylene blue distal to the obstruction site; however, there were two patients in whom the finder needle could not demonstrate return of dye. These two patients received D-GE based on endosonographic and fluoroscopic appearance to ensure the location of the proximal jejunum. A 15-mm by 10-mm cautery-enhanced LAMS was used in all cases.

Dilation of the LAMS lumen was performed in 40/53 (75.5 %) patients, with median dilation size of 15 mm (IQR 13.5 – 15 mm). Median procedure time was 39 minutes (IQR 26 – 51.5 minutes). There was no statistical difference in median procedure time between the two centers (JHH with median procedure time 37 minutes, IQR 22 – 55.5 minutes; VM with median procedure time 42 minutes, IQR 35 – 48 minutes, P = .13). Median post-procedural length of stay was 3 days (IQR 2 – 7 days).

Clinical success was achieved in 51 of 57 patients (89.5 %), including two patients that did not have return of dye via the finder needle but the optimal location of proximal jejunum could be identified based on endosonographic and fluoroscopic guidance, with median follow-up of 131 days (IQR 61 – 255 days). We were able to identify an optimal window for D-GE with resultant technical and clinical success in these four patients who had obstruction in the distal duodenum or proximal jejunum. Those with benign GOO had longer follow-up (median follow-up 319.5 days, IQR 168.8 – 598 days) compared to patients with malignant GOO (median follow-up 196 days, IQR 50.5 – 278.5 days, P = .003). Median time to resuming at least a full liquid diet was 1 day (IQR 1 – 2 days). Among those with clinical success, 24 patients (47.1 %) tolerated regular diet (GOO score of 3), 13 (25.5 %) tolerated low-residue diet (GOO score of 3), 11 (21.5 %) patients tolerated soft diet (GOO score of 2), and 3 (5.9 %) patients tolerated full liquid diet (GOO score of 1).

Adverse events

There were two AEs (3.5 %) ( Table 1 and Fig. 5 ). One patient with unresectable duodenal cancer developed leakage around an appropriately placed LAMS, manifested by abdominal pain and fever 6 hours post-procedure. In retrospect, stent deployment was challenging as there was intervening fat between the stomach and small bowel. That patient underwent surgical intervention and, therefore, this was rated as a severe AE. Operative findings showed the LAMS was still located in the stomach and the small bowel. However, the LAMS was under tension and had traversed the mesocolon, resulting in leakage. The patient recovered after 7 days in the hospital and is still alive a year later and undergoing palliative chemotherapy. In this cohort of D-GE, no patients had gastrocolonic fistula. The second patient developed hemoperitoneum without pneumoperitoneum, presumably from the EUS-GE site. She required an angiogram, therefore, this was rated as a moderate AE. The bleeding resolved spontaneously and no source was found on angiography. The patient had a 2-g hemoglobin drop without blood transfusion requirement. There were two misplaced stents with their proximal flange deployed in the peritoneum, which were both immediately retrieved endoscopically and the gastric defects closed with an over-the-scope clip. A new LAMS was then deployed successfully in both cases. These were not considered AEs based on the ASGE lexicon criteria.

Reintervention and long-term outcomes

Among 53 patients who achieved technically successful D-GE, only patients who had recurrence of worsening GOO symptoms received repeat upper endoscopy. Eighgt of 53 patients (15.1 %) required an unplanned reintervention, of whom two had stent occlusion and six had patent stents at repeat upper endoscopy ( Table 1 and Fig. 5 ). This suggested that the latter six patients had symptoms compatible with gastroparesis and were managed with prokinetic medications. Of these eight patients, three had benign GOO. They included five patients with inability to get adequate oral intake to maintain nutrition and intermittent nausea and/or vomiting. In these five patients, a widely patent LAMS was found at endoscopy and they were treated with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement for presumed delayed gastric emptying at a median of 82 days (IQR 20.5 – 252.5 days) from index D-GE. Two patients developed nausea and vomiting with the findings of stent occlusion from food at 23 and 118 days from index procedure. They were treated with food removal. One of these two patients developed recurrent obstruction, which was managed successfully by placing a coaxial esophageal FCSEMS through the LAMS. One patient with recurrent nausea and vomiting 19 days after index D-GE was found to have a progressive downstream stricture from jejunal adenocarcinoma. There was no further downstream site to perform another D-GE. This was managed with a low-residue diet until he succumbed to his disease. Among 44 patients with malignant GOO with clinical success after D-GE, 24 patients (54.5 %) died due to their primary cancer during a median follow-up time of 162.5 days (IQR 43 – 277 days). There were no deaths in patients with benign GOO.

Discussion

Since EUS-GE was reported in porcine models 18 19 , the technique has evolved rapidly mainly for patients with gastric outlet obstruction 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 . Our group published the first US clinical experience with EUS-GE, followed by comparative studies using the technique as an alternative to enteral stenting and surgical gastroenterostomy. EUS-GE resulted in comparable rates of clinical success (90 % in surgical GE vs 87 % in EUS-GE, P = .18) and AEs (16 % in surgical GE vs 25 % in EUS-GE, P = .3) 9 . Another smaller comparative study showed that rates of AE were higher in those who underwent laparoscopic GE (41 % vs 12 % in EUS-GE, P = .04) 10 . In addition, in patients with malignant GOO, EUS-GE had comparable effectiveness compared to enteral stenting, while being associated with less recurrence of symptoms and lower requirement for reintervention 15 . In terms of EUS-GE techniques, there are two main approaches, including balloon-assisted GE and D-GE. A recent comparative study showed that both techniques resulted in high and comparable technical and clinical success rates. Nonetheless, D-GE may be preferred due to shorter procedure times (mean 35.7 minutes versus 89.9 minutes, P < .001) 14 . Most centers continue to perform balloon-assisted GE due to the belief that an over-the-wire procedure ensures safety. We aimed to report solely on EUS-GE using the direct approach as this has been our preferred technique since we gained experience with the procedure.

In this study, we specifically evaluated outcomes with the D-GE technique in patients with benign and malignant GOO over a 4-year cohort from two large academic centers to evaluate the efficacy, safety and durability of this specific approach. We demonstrated excellent technical and clinical success rates at 93 % and 89.5 %, respectively. Median procedure time was short at 39 minutes and there was no significant heterogeneity between the two centers, indicating that the D-GE technique is perhaps generalizable among experts at high-volume centers. Given this is a long-term cohort, we were able to provide the longest follow-up compared to other EUS-GE studies, with median follow-up time of 254 days in benign GOO and 123.5 days in malignant GOO, the latter limited by the poor prognosis and nature of the disease. This provided the opportunity to evaluate the dynamics of the clinical course in patients who achieved clinical success and rate of reintervention after D-GE.

There have been concerns that inadvertent gastrocolostomy creation could be a rather common AE in D-GE 14 . This could be prevented using the “finder needle” technique with aspiration of blue-dyed saline confirming access to a jejunal loop. D-GE is an efficient technique because it eliminates the need for advancement of a balloon catheter into the small bowel for localization during EUS-GE (balloon-assisted technique). We believe this simplifies the procedure and shortens procedure time as advancement of a balloon-catheter across the site of obstruction can be complex and frequently requires placement of an overtube to avoid catheter looping in the stomach. An inadvertent gastrocolostomy did not occur in the current series. We have encountered a case of leakage around the LAMS where the stent traversed the mesocolonic fat and the stent was placed under tension. This could be a caution for endoscopists performing D-GE to ensure no significant fat exists between the intervening small bowel and stomach.

Compared to prior retrospective studies using EUS-GE in benign GOO 10 14 27 and malignant GOO 9 10 14 15 , we found a slightly higher rate of reintervention at 15.1 %. This is partly due to longer follow-up time as mentioned. The majority of patients (62.5 %) who required reinterventions had widely patent LAMS, suggesting other mechanisms of recurrent symptoms, such as delayed gastric emptying, rather than ongoing mechanical obstruction.

There are several limitations of this study, mainly due to its retrospective methodology. Clinical success was evaluated based on subjective reports by patients as recorded in electronic medical charts. The patients in this cohort came from two large academic medical centers, therefore, results may not be applicable to low-volume centers. The main strength of the study was its specific approach using D-GE technique rather than heterogeneity of EUS-GE techniques, with its longest follow-up cohort using the technique to date.

Conclusion

In conclusion, D-GE is safe and effective in management of both malignant and benign GOO. Clinical success is durable and the rate of reintervention is low based on a long-term cohort. D-GE simplifies the procedure and shortens procedure time. Despite these promising data on D-GE, randomized controlled trials are still required to develop algorithms and guidelines for treatment of malignant and benign GOO. These include a comparison between duodenal stenting and D-GE, as well as surgical GE and D-GE. We suggest that D-GE is a viable option that endoscopists should discuss with patients and in a multidisciplinary team at high-volume centers.

Competing interests Dr Irani is a consultant for Boston Scientific. Dr Kumbhari is a consultant for ReShape Life Sciences, Apollo Endosurgery, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific, and receives consulting fees from Pentax Medical and C2 Therapeutics. Dr Kalloo is a founding member and equity holder for Apollo Endosurgery. Dr Khashab is a consultant and on medical advisory board for Boston Scientific and Olympus America and a consultant for Medtronic.

These authors contributed equally.

References

- 1.Irani S, Kozarek R A. Techniques and principles of endoscopic treatment for benign gastrointestinal strictures. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2015;31:339–350. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee . Banerjee S, Cash B D, Dominitz J A et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:663–668. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dormann A J, Deppe H, Wigginghaus B. Self-expanding metallic stents for continuous dilatation of benign stenosis in gastrointestinal tract – first results of long-term follow-up in interim stent application in pyloric and colonic obstructions. Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:957–960. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi W J, Park J J, Park J et al. Effects of the temporary placement of a self-expandable metallic stent in benign pyloric stenosis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:417–422. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.4.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heo J, Jung M K. Safety and efficacy of a partially covered self-expandable metal stent in benign pyloric obstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16721–16725. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irani S, Kozarek R A.6th editionYamada’s textbook of Gastroenterology West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paimela H, Tuompo P K, Peräkyl T et al. Peptic ulcer surgery during the H2-receptor antagonist era: a population-based epidemiological study of ulcer surgery in Helsinki from 1972 to 1987. Br J Surg. 1991;78:28–31. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oh S Y, Edwards A, Mandelson M et al. Survival and clinical outcome after endoscopic duodenal stent placement for malignant gastric outlet obstruction: comparison of pancreatic cancer and nonpancreatic cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:460–468. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khashab M A, Bukhari M, Baron T H et al. International multicenter comparative trial of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy versus surgical gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Endosc Int Open. 2017;5:E275–E281. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-101695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perez-Miranda M, Tyberg A, Poletto D et al. EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy versus laparoscopic gastrojejunostomy: an international collaborative study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:896–899. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khashab M A, Kumbhari V, Grimm I S et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: the first U. S. clinical experience (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:932–938. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tyberg A, Perez-Miranda M, Sanchez-Ocaña R et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy with a lumen-apposing metal stent: a multicenter, international experience. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4:E276–E281. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-101789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Itoi T, Ishii K, Ikeuchi N et al. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided double-balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass (EPASS) for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Gut. 2016;65:193–195. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y I, Kunda R, Storm A C et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: a multicenter study comparing the direct and balloon-assisted techniques. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1215–1221. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Y I, Itoi T, Baron T H et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy is comparable to enteral stenting with fewer re-interventions in malignant gastric outlet obstructions. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2946–2952. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adler D G, Baron T H. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotton P B, Eisen G M, Aabakken L et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE workshop. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:446–454. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binmoeller K F, Shah J N. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastroenterostomy using novel tools designed for transluminal therapy: a porcine study. Endoscopy. 2012;44:499–503. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoi T, Itokawa F, Uraoka T et al. Novel EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy technique using a new double-balloon enteric tube and lumen-apposing metal stent (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khashab M A, Baron T H, Binmoeller K F et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy: a new promising technique in evolution. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1234–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoi T, Tsuchiya T, Tonozuka R et al. Novel EUS-guided double-balloon-occluded gastrojejunostomy bypass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83:461–462. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siddiqui U D, Levy M J. EUS-guided transluminal interventions. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1911–1924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ungureanu B S, Pătrașcu Ș, Drăgoescu A et al. Comparative study of NOTES versus endoscopic ultrasound gastrojejunostomy in pigs: a prospective study. Surg Innov. 2018;25:16–21. doi: 10.1177/1553350617748278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amin S, Sethi A. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gastrojejunostomy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2017;27:707–713. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Irani S, Baron T H, Itoi T et al. Endoscopic gastroenterostomy: techniques and review. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2017;33:320–329. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoi T, Baron T H, Khashab M A et al. Technical review of endoscopic ultrasonography-guided gastroenterostomy in 2017. Dig Endosc. 2017;29:495–502. doi: 10.1111/den.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y I, James T, Agarwal A et al. EUS-guided gastroenterostomy in management of benign gastric outlet obstruction. Endosc Int Open. 2018;6:E363–E368. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-123468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]