Abstract

Technologies have emerged that aim to help older persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRDs) remain at home while also supporting their caregiving family members. However, the usefulness of these innovations, particularly in home-based care contexts, remains underexplored. The current study evaluated the acceptability and utility of an in-home remote activity monitoring (RAM) system for 30 family caregivers of persons with ADRD via quantitative survey data collected over a 6-month period and qualitative survey and interview data collected for up to 18 months. A parallel convergent mixed methods design was employed. The integrated qualitative and quantitative data suggested that RAM technology offered ongoing monitoring and provided caregivers with a sense of security. Considerable customization was needed so that RAM was most appropriate for persons with ADRD. The findings have important clinical implications when considering how RAM can supplement, or potentially substitute for, ADRD family care.

Keywords: Remote activity monitoring, Technology, Smart home, Alzheimer’s disease, Caregiving, Dementia

Alzheimer’s-related dementia is the sixth leading cause of death and one of the most costly diseases in the United States (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Hurd, Martorell, Delavande, Mullen, & Langa, 2013; Kelley, McGarry, Gorges, & Skinner, 2015). An estimated 5.5 million Americans are living with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia (ADRD) in 2017 (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). Most ADRD care (78%) is provided by family caregivers (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016; Friedman, Shih, Langa, & Hurd, 2015; National Academies of Sciences and Engineering, 2016; Stone, 2015). In 2017, 18.1 billion hours of unpaid care was provided by over 15 million caregivers (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). However, the availability of caregivers is expected to decline over the next 25 years (Gaugler & Kane, 2015; Redfoot, Feinberg, & Houser, 2013). An aging population, rising healthcare costs, and an expected increase in ADRD prevalence will exacerbate carerelated pressures on fewer available family caregivers (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Schulz & Martire, 2004). In light of these trends, technologies that could supplement family caregiving have received increased attention in the scientific literature (Demiris, 2015; Gaugler & Kane, 2015). The objective of the current study was to examine whether one of these technological approaches, remote activity monitoring (RAM), is perceived as acceptable and useful for family caregivers of persons with ADRD living at home.

Background

Although family caregiving offers important societal benefits and arguably prevents the use of more costly formal long-term care services (i.e., institutionalization), most family assistance is provided for personal reasons – to keep the person with ADRD at home, to maintain close proximity, or to fulfill a sense of obligation (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017). However, caregiving can become burdensome, cause depression, worsen immune system functioning, and increase mortality in caregivers (Alzheimer’s Association, 2017; Kiecolt-Glaser, Glaser, Gravenstein, Malarkey, & Sheridan, 1996; Liu & Gallagher-Thompson, 2009; Schulz & Beach, 1999; Vitaliano, Zhang, & Scanlan, 2003). These factors may, in turn, diminish the quality of care and increase the likelihood of institutionalization for the person with ADRD (Gaugler, Yu, Krichbaum, & Wyman, 2009).

Given limited human and financial resources, RAM systems have been proposed as a novel approach to improve person-centered outcomes for ADRD and, secondarily, to support caregivers of persons with dementia. The design, development, and theoretical benefits of various RAM systems have been described previously (Block et al., 2016; Bossen, Kim, Williams, Steinhoff, & Strieker, 2015; Preusse, Mitzner, Fausset, & Rogers, 2017; Stucki et al., 2014; Torkamani et al., 2014; Williams, Arthur, Niedens, Moushey, & Hutfles, 2013). In general, RAM systems consist of a network of discrete sensors (e.g., infrared motion sensors, body-worn sensors, or video) that monitor a person with ADRD in their homes and close surrounding areas (i.e., front door, porch). Sensor data is analyzed in real-time to alert caregivers to abnormal activity (e.g., wandering, behavioral disturbances, falls). In this way, RAM may supplement or reduce the need for in-person care, by providing information on daily activity and potentially preventing crises (Matthews et al., 2015; Wild, Mattek, Austin, & Kaye, 2016).

Despite promising pilot data and anecdotal evidence, few high-quality, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have examined RAM use over prolonged time periods. A 2008 Cochrane review did not find empirical evidence related to the use of RAM or any other smart home technologies among persons with ADRD (Martin, Kelly, Kernohan, McCreight, & Nugent, 2008). Since 2008, two RCTs have shown benefits for caregivers assigned to RAM: A 6-month RCT of RAM (n = 60 persons with ADRD and caregivers, or dyads) found significantly improved caregiver quality of life along with reductions in burden and distress in the experimental group. Another RCT comparing a RAM system designed to prevent nighttime ADRD injury and wandering (n = 26 dyads) to a control group (n = 27 dyads) found that RAM users were 85% less likely to suffer harmful nighttime events than controls during a 12-month period (Rowe et al., 2009). A third, non-experimental study found that RAM users experienced less frequent use of hospital, emergency, and custodial care services, and had lower emergency healthcare costs than non-users, though the sample sizes were too small to demonstrate significant differences (Finch, Griffin, & Pacala, 2017).

Still, limited evidence supports RAM’s efficacy as a home-based technology for persons with ADRD. Furthermore, there is a lack of information on family caregivers’ longer-term perceptions of the acceptability, usefulness, and feasibility of RAM (Bossen et al., 2015; Chaudhuri et al., 2015; Wild, Boise, Lundell, & Foucek, 2008; Williams et al., 2013). In an effort to expand understanding of how well such systems work in the day-to-day lives of families living with ADRD, the current study aimed to determine whether family caregivers of persons with dementia perceived RAM as acceptable and useful for up to 1.5 years and to identify characteristics of family caregivers and persons with ADRD that are associated with acceptance of RAM.

Methods

Design

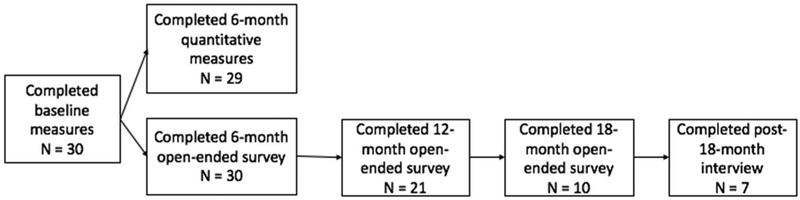

The current study is part of a 5-year, mixed methods, randomized controlled evaluation of a RAM system for persons with ADRD and their family caregivers at home (R18 HS022836; IRB #1401S47514). For the current study, we used a parallel convergent mixed methods design employing both qualitative and quantitative methods (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2010; Figure 1) on a subsample of ADRD caregivers that we had enrolled and followed up to 12/31/16 in the parent evaluation. Only participants in the intervention condition were included in the present acceptability and utility study; a report of the RCT results will be made upon completion of the parent study.

Figure 1.

Mixed methods design.

Remote Activity Monitoring System

The RAM system examined in this study includes six unobtrusive motion sensors (door sensors, motion sensors, a toilet flush sensor, and a bed mattress sensor) placed in the home to detect daily activity, as well as an emergency call pendant. The sensors operate jointly, exchange information on movement or function (e.g., getting in and out of bed; opening residence doors; using toilet), and can detect unusual activity patterns. The data collected by the sensors are analyzed using algorithms developed by the RAM provider, so that once a baseline activity pattern is established, any significant deviations from that pattern are communicated to caregivers. Thus, caregivers are alerted to abnormal activity patterns that may indicate a possible health condition (e.g., if sleep patterns change or the bathroom is used more frequently than usual).

Additionally, users can configure alerts based on unexpected or potentially dangerous activity. For example, sensors can identify if persons with ADRD leave their home at unexpected times, or stay in the bathroom too long. Alerts can be received by phone or email, and users can create a list of family, friends, and service providers to call if the primary caregiver cannot be reached.

An online portal that displays data collected via RAM is available to caregivers and can be shared with health service providers. By logging in, users can view charts that visually summarize the care recipient’s activity. Users can view the last 60 days of data, as well as 24-hour snapshots of any one day’s activity.

Following completion of a baseline survey and random assignment to receive RAM for an 18-month period for free, dyads received a home visit from the Director of Nursing and Technology Services (DNT); a licensed vendor of the RAM technology. The DNT installed the RAM system and provided caregivers with RAM instructions, maintenance, and support as needed.

Participants

Participants were recruited for the parent study via the University of Minnesota Caregiver Registry, advertisements, and community outreach. Inclusion criteria for persons with ADRD were: 1) English speaking; 2) physician diagnosis of ADRD; 3) not currently receiving RAM or similar care/case management services; and 4) ≥ 55 years of age. Caregivers of persons with ADRD had to: 1) speak English; 2) be ≥ 21 years of age; 3) self-identify as someone who provides help to the person with ADRD because of their cognitive impairments; 4) self-identify as the person most responsible for providing hands-on care to the person with ADRD; and 5) plan to remain in the area for at least 18 months. Informed consent was obtained from the caregiver (or legally authorized representative if needed), and the person with ADRD provided assent to participate.

A total of 30 caregivers and their care recipients (see Tables 1 and 2) randomized to the intervention condition (i.e., who received the RAM system) completed the baseline, 6-month surveys, and 6-month RAM system review checklist. Additional open-ended question response data from 56 RAM system review checklists at 6-, 12-, and 18-months as well as post-18 month semi-structured interviews (n = 7) were also included (see Figure 3).

Table 1.

Baseline Caregiver Descriptive Context of Care Characteristics (N = 30)

| Caregiver Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 25 (83.3%) |

| Age, M (SD) | 60.79 (11.97) |

| Caucasian | 29 (96.7%) |

| Married | 24 (80.0%) |

| Number of living children, M (SD) | 1.86 (1.27) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 20 (66.7%) |

| Annual income of $80,000 or more | 10 (33.3%) |

| Employed | 12 (40.0%) |

| Spouse of care recipient | 15 (50.0%)* |

| Adult child of care recipient | 13 (43%)* |

| Months providing help to the care recipient, M (SD) | 42.70 (25.21) |

|

| |

| Primary Objective Stressors | M (SD) |

|

| |

| Activities of daily living dependencies | 2.57 (2.97) |

| Instrumental activities of daily living dependencies | 11.23 (4.06) |

| St. Louis University Mental Status score | 11.23 (7.80) |

| Cognitive impairment | 2.54 (0.72) |

| Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist - Frequency | 1.53 (0.57) |

| | |

|

Resources | |

| Caregiver self-efficacy | 28.37 (6.36) |

| Caregiver Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire | 23.93 (5.60) |

| | |

|

Caregiver Distress | |

| Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist - Reaction | 1.05 (0.60) |

| Zarit Burden Inventory | 37.70 (13.34) |

| Role captivity | 9.23 (2.78) |

| Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression | 30.43 (9.07) |

Note: M (SD) = Mean (Standard deviation)

The remaining caregivers were the daughter- or son-in-law of the care recipient, n=1 (3%), or indicated “other”, n = 1 (3%).

Table 2.

Baseline Care Recipient Descriptive Characteristics (N = 30)

| Care Recipient Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female | 17 (56.7%) |

| Age, M (SD) | 77.47 (9.09) |

| Caucasian | 28 (93.3%) |

| Married | 16 (53.3%) |

| Number of living children, M (SD) | 3.27 (2.54) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 15 (50.0%) |

| Annual income of $30,000 or more | 18 (60.0%) |

| Lives with caregiver | 19 (63.3%)* |

| On Medicaid | 6 (20.0%) |

The remaining care recipients lived at home alone, n = 4 (14%), with other relatives, n = 2 (7%), in standard assisted living, n = 1 (3%), in a family care home, n = 1 (3%), or indicated they lived in an “other” living situation, n = 3 (10%).

Figure 3.

Number of participants who have completed each stage of data collection included in the present study.

Data Collection Procedures

At baseline and 6 months, an online or mailed survey was administered to caregivers. Context of care variables included gender, age, race, marital status, number of living children, education, annual income, relationship to the care recipient, duration of care, living arrangement, and Medicaid status. Dementia severity variables included the person with ADRD’s dependence on assistance with 6 activity of daily living (ADL) tasks (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffe, 1963) and 6 instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) tasks (Lawton & Brody, 1969). Additionally, an 8-item memory impairment scale assessed intensity of memory loss, communication deficits, and recognition impairments at each time point (Pearlin, Mullan, Semple, & Skaff, 1990). The St. Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS) Exam was administered to persons with ADRD to assess orientation, memory, and executive function (Tariq, Tumosa, Chibnall, Perry, & Morley, 2006). Frequency of memory and behavioral expressions was measured with the Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC; Teri et al., 1992).

Caregiver distress was ascertained with the 22-item Zarit Burden Interview, a widely-used measure of caregiver subjective stress (Zarit, Todd, & Zarit, 1986). Two additional indices were used: a 4-item scale assessing the involuntary aspects of the caregiving role (role captivity) and the reaction subscale of the R-MBPC (Pearlin et al., 1990). Caregiver depressive symptoms were measured with the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale (Radloff, 1977). Caregiver resources included self-efficacy, which was assessed with an 8-item measure (Fortinsky, 2001; Fortinsky, Kercher, & Burant, 2002) and sense of competence, which was measured with the 7-item Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (Vernooij-Dassen et al., 1999).

The RAM system review checklist is a 21-item, close-ended checklist. The senior author adapted checklists administered in prior research to assess perceptions of acceptability and utility of the RAM system for persons with ADRD (Gaugler, Reese, & Tanler, 2016; Hamel, Sims, Klassen, Havey, & Gaugler, 2016). Example items include: “After using RAM, I thought that the person with memory loss was more engaged and alert.” Item responses ranged from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree” and were averaged to create an overall 6-month score (see Table 3; α = .97).

Table 3.

Six-Month Remote Activity Monitoring Review Checklist Scores (N = 30)

|

Likert Scale: 1 = Strongly disagree; 3= Neutral; 5 = Strongly

agree |

Mean (SD) |

Percent Agree & Strongly Agree |

| RAM was easy to use | 3.79 (1.32) | 62.0% |

| The information provided on how to use RAM was clear to me | 4.10 (0.90) | 72.4% |

| The needs assessment session provided by the Director of Nursing Technology was helpful | 4.41 (0.80) | 88.9% |

| The sensors of the RAM system work well in the person with memory loss’ home | 3.89 (1.13) | 64.3% |

| The Director of Nursing Technology has been helpful to me in using RAM | 4.08 (1.16) | 73.1% |

| The technology related to RAM works well | 4.00 (1.18) | 66.7% |

| After using RAM, I feel like I now have access to a service that looks as though it will meet my needs | 3.71 (1.25) | 64.2% |

| After using RAM, I feel like I was able to find a service that looks as though it will meet the person with memory loss’ needs | 3.67 (1.21) | 59.2% |

| There are financial constraints to me being able to use RAM | 2.66 (1.38) | 30.7% |

| There are time constraints to me being able to use RAM | 2.62 (1.13) | 23.0% |

| The RAM portal is simple and helpful | 3.54 (0.93) | 41.6% |

| The Director of Nursing and Technology was helpful to me in coming with a care plan | 3.96 (1.00) | 66.7% |

| The alerts provided by RAM have been helpful | 3.67 (1.27) | 54.2% |

| I felt lost using RAM | 2.44 (1.23) | 28.0% |

| I wish I would have known about RAM sooner | 2.92 (1.09) | 23.0% |

| The alerts generated by the RAM have helped prevent crises for the person with memory loss | 3.13 (1.33) | 34.7% |

| The RAM service provided me with a sufficient number of options to support me | 3.71 (1.18) | 57.1% |

| The RAM service provided me with a sufficient number of options to support the person with memory loss | 3.63 (1.18) | 59.2% |

| I am satisfied with the RAM | 3.79 (1.13) | 57.1% |

| I would recommend RAM to others in a similar situation as the person with memory loss is | 4.00 (1.11) | 66.7% |

| I would recommend RAM to others in a similar situation as I am | 3.93 (1.24) | 66.7% |

Note: M = mean; SD = standard deviation; RAM = Remote activity monitoring

At the conclusion of the checklist, caregivers were asked 8 open-ended questions (see Table 4). Example items include: “How was RAM easy [difficult] to use?” and “Do you feel the alerts generated by RAM worked well? Why or why not?” Semi-structured interviews included the same 8 open-ended questions, and prompts for clarification and expansion. Semi-structured interviews took place following completion of 18-month surveys, lasted 30–45 minutes, and were digitally recorded and transcribed.

Table 4.

Interview & Survey Questions of Caregiver Perceptions of RAM Acceptability and Utility

|

Benefits & Ease of Use |

| 1. How was RAM easy to use? |

| 2. How was RAM difficult to use? |

| 3. Why do you think RAM was easy or difficult to use? |

| |

|

Functionality |

| 4. Do you feel the alerts generated by RAM worked well? Why or why not? |

| 5. How did the RAM portal help you in monitoring the person with memory loss? Why or why not? |

| |

|

Caregiving Impact |

| 6. How did your interactions with the Director of Nursing and Technology help or hinder your use of RAM? |

| 7. Do you think RAM has any effect on how you care for the person with memory loss? |

| |

|

Other |

| 8. Please add any other ways that the RAM has been helpful to you, or how you feel the RAM could be improved: |

Note: RAM = remote activity monitoring

Data Analysis

The 1st and 2nd authors open-coded all available qualitative data, including open-ended responses from the RAM review checklist collected at 6, 12, and 18 months, as well as interview transcripts collected at 18 months. Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to inductively code themes. Both coders read all transcripts and generated a set of preliminary coding categories. These preliminary categories formed the initial coding scheme, which was refined through an iterative process of coding a random subset of the data independently, then discussing and adjusting the coding system as needed. The seventh and senior authors reviewed the initial codes and thematic framework. All semi-structured interviews and open-ended surveys were then double-coded using NVivo and compared at regular intervals to review discrepancies and maintain reliability. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Inter-rater reliability was evaluated via NVivo with an average kappa = 0.88 and percent agreement 97.8%. The search for interpretation and alternative understandings led to saturation, whereby the themes were well-described by and fitting with the qualitative data (Dey, 1999; Saunders et al., 2017). Regular debriefing among researchers and audit trails (clear pathways detailing how the data were collected and managed) enhanced transparency and credibility (Marshall and Rossman, 2016).

The senior author then completed all quantitative descriptive analyses, and conducted Kendall’s Tau-B and Spearman bivariate correlations. These processes compared the 6-month RAM review checklist scores, baseline context of care and dementia severity variables (i.e., scores for assistance with ADLs and IADLs; memory impairment; SLUMS and R-MPBC scores), and 6-month change scores of caregiver distress and resource indicators. All quantitative analyses included only data collected at baseline and 6 months, and excluded data collected at 12 and 18 months.

Integration of the qualitative and quantitative strands was achieved after all qualitative coding and quantitative analyses were completed, by comparing 6-month descriptive empirical results of the RAM review checklist to the qualitative themes to determine whether, and why, the RAM system was perceived as useful and acceptable (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2011; Tashakkori & Teddlie, 2010). In addition, (given the available sample size of participants who completed the full 18 months of data collection), a case-oriented merged analysis was used to identify three case examples signifying trends in acceptability and utility over the 18-month study period (Creswell & Plano-Clark, 2011; see Table 5). The senior author examined participants’ trajectories of RAM review checklist ratings, and selected one case representing consistently high scores, consistently low scores, and scores that increased over time. Subsequently, these participants’ open-ended responses and interviews were examined for quotes illustrating the nature of their experiences and the reasons why these participants rated RAM highly or poorly. The case-oriented merged analysis was intended to provide a detailed, rich illustration of three trajectories of adjustment, rather than to summarize the experiences of the entire cohort.

Table 5.

Case-Oriented Merged Analysis: RAM Technology Acceptability and Utility Scores over an 18-Month Period

| Dimension Case |

6-Month RAM Review Score | 12-Month RAM Review Score | 18-Month RAM Review Score | Exemplar Quote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.62 | 4.67 | 5.00 | |||

| High Enthusiasm | ID 24 (58 year-old woman caring for an 85 year-old mother-in-law) | “In general, I feel better about the coverage we are providing to our loved one. I feel we are doing a better job of monitoring her situation without being too intrusive.” | “I log on several times a day, mostly in the evening and at night, to check on my love one when she is alone in her home and should be in bed. It is easy to see where she is located in her home and watch when she is having a restless night to make sure she does not wander.” | “It has also built our confidence to leave our loved one in her home and living independently longer than we might have had we not had the system in place so that we know she is safe.” | “It’s just been very, very helpful. And, it’s made us confident in that we can set alarms so we get called at night in specific situations. So again, we feel like we’re being proactive. We’re aware. We’re going to be notified.” |

| 2.86 | 3.00 | 2.86 | |||

| Low-to-Moderate Enthusiasm | ID 38 (81 year-old woman caring for her 82 year-old husband) | “I set off the alarms myself forgetting they were there and became very frustrated.” | “I probably did not need the monitoring, since wandering did not become an issue so far.” | “Did not use [the alerts] much. Do not think I could answer this.” | “Did not think the person with memory loss needed much monitoring, since I am in house. Not like if person living alone.” |

| 3.24 | 4.48 | 4.29 | |||

| Adaptation/Acclimation | ID 11 (54 year-old man caring for his 90 year-old mother) | “I lost lots of sleep when the phone calls early in the morning, after that I just could not get going in the morning.” | “I didn’t like the phone calls so late at nite-early morning but it also told me something was going on, an early detection of an infection, so then I will get a urine sample to get tested and every one was right on...” | “98% of the alarms told me when my mother was having UTIs and I would work that into getting her to a urologist, just to prove she was having an infection, that was because she was not in bed but wandering around the house...” | “It always confirmed my thoughts on when the UTI was coming. Cause that way I could always go by that. And then I can always say, well, she’s getting a UTI, you know. And pretty much all the time I was right.” |

Note: 1 = Strongly disagree; 3 = Neutral; 5 = Strongly agree; Higher scores indicate higher enthusiasm and utility for RAM

Results

Participants

Caregivers were primarily Caucasian (96.7%), married (80.0%), women (83.3%), with a mean age of 60.79 years (SD = 11.97; Table 1). Care recipients were primarily Caucasian (53.3%), married (56.7%), female (93.3%), with an average age of 77.47 years (SD = 9.09; Table 2). Based on the descriptive data in Table 1 and 2, persons with ADRD were, on average, moderately cognitively impaired (e.g., SLUMS score, memory impairment). Similarly, persons with ADRD experienced moderate functional impairment and behavioral problems (e.g., ADL and IADLs; R-MPBC). Caregivers also indicated moderate levels of distress (based on their CES-D, ZBI, role captivity, role overload, and R-MBPC reaction scores) and resources (selfefficacy, sense of competence).

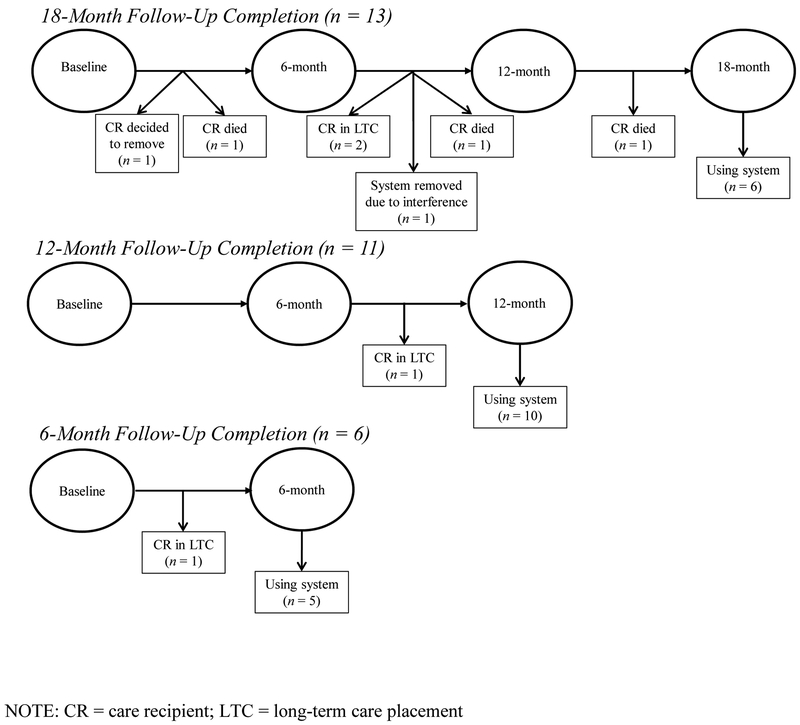

Due to caregivers’ varying duration of participation in the ongoing parent study, the sample included three cohorts: the 6-month cohort (i.e., those caregivers whose most recent data collection interval was 6-months; n = 6), the 12-month cohort (n = 11), and the 18-month cohort (n = 13; see Figure 2). Participants who elected to stop using RAM, or who no longer needed RAM because of the relocation or death of a care recipient, were still included in the study and continued to participate in data collection.

Figure 2.

Dispositional status of remote activity monitoring (RAM) system use, 18-month, 12- month, and 6-month study cohorts (N = 30).

Empirical associations between 6-month acceptability/utility and other domains.

Correlations were conducted between average RAM System Review Checklist scores and context of care/background variables (see Tables 1 and 2). No correlation achieved statistical significance (p < .05). In addition, correlations between the RAM System Review Checklist Score and baseline dementia severity variables (i.e., SLUMS, memory impairment, ADLs and IADLs) were conducted. Again no correlation achieved statistical significance. A final set of correlations between RAM System Review Checklist scores and baseline and 6-month change in caregiver distress (ZBI, role overload, R-MBPC) and caregiver resources (self-efficacy, sense of competence) were conducted. Although some associations demonstrated noteworthy trends (e.g. role overload baseline to 6-month change: r = −0.19), none achieved statistical significance.

Acceptability of RAM.

Qualitative analysis identified 4 main themes regarding acceptability of the RAM system. Below, we describe each theme and link them to relevant quantitative responses from the 6-month RAM review checklist (see Table 3).

Fitting RAM to Participants ‘ Needs: Context Matters

Two-thirds of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they would recommend RAM to other caregivers or care recipients in a similar situation, suggesting that RAM was viewed as useful by many participants. However, the qualitative data suggested that the appeal of the RAM system depended critically on the fit between users’ needs and the services offered. Fourteen participants suggested that RAM did not fit their caregiving situation. Reasons for a mismatch were: 1) the stage of the care recipient’s disease progression; or: 2) if the caregiver lived with the care recipient. Several caregivers indicated that the care recipient’s dementia had progressed to a stage that necessitated 24-hour in-home supervision, and that the monitoring was less useful to them:

I can see in my head which situations it could be really beneficial. And not in-home one-on-one 24/7 supervision.. .during the day, he’s not left alone. The amount of time he’s left alone is, if I’m, you know, in the bathroom, which is just for a few minutes...So there’s no need for any type of monitoring of patterns.. .(Semi-structured interview; daughter, age 51)

Others suggested the opposite problem – that the care recipient was still in the early stages of their disease progression and did not yet require close monitoring, as described by one participant: “He probably isn’t bad enough to make good use of it yet.” (Open-ended survey response; wife, age 79)

On the other hand, fourteen caregivers who did not find RAM useful themselves suggested that RAM would likely be helpful for caregivers who did not live with the care recipient or who needed to be away for several hours during the day. For instance, one caregiver reported:

I think that it could have helped a lot more had I not been living with my mom. I think that it’s more suited to people who aren’t living together. (semi-structured interview; daughter, age 55)

In some cases where the care recipient was still in the early stages of ADRD, caregivers could see the system as becoming more useful to them over time. One shared, “We are not at a stage yet where we need the phone call alerts, but it’s nice to know that is available in the future (open-ended survey response; daughter, age 61)

RAM Adjustment: It Takes Time and Help

Participants’ responses indicated a period of adjustment to the system that was often difficult and aggravating. False alarms were a frequently reported problem, which required time and assistance to adjust. For many, it seemed that the RAM system was overly cautious in alerting caregivers initially, as one expressed, “Being woke up [between] 4:30–6:30am to be told my mom had been in the bed too long, disrupted badly needed sleep for me.” (open-ended survey response; daughter, age 55) Perhaps reflecting concerns about false alarms, only 54.2% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the alerts provided by RAM were helpful, and ten participants mentioned false alarms specifically in their qualitative responses.

Participants subsequently engaged in a process of “working out the kinks” of the system; ten participants discussed this process in their open-ended responses. Adapting the RAM system often involved a trial-and-error process of identifying the underlying problem and making changes accordingly:

We were getting a lot of false alarms related to ‘not returning from the bathroom.’ After moving some sensors, I think we finally figured out that we expected her to stay in bed longer and if she got up earlier, it was waiting for her to return to bed and set off an alarm. (open-ended survey response; daughter, age 53)

In the majority of cases, the process of adjustment was facilitated by staff support. Having a competent, proactive human being to talk to and troubleshoot was crucial for adjusting the system to fit users’ needs. One participant’s responses emphasize the importance of attentive, reliable, and knowledgeable staff in addressing problems:

I have learned how to use the RAM more effectively throughout the past six months with excellent training (emails, phone calls, webinars) from [DNT]. It’s easy to use (if you have some familiarity with technology) but it would have been too much to learn at our initial meeting with [her], so adding additional aspects of monitoring in the RAM system spread out throughout the months has worked best for me. (open-ended survey response; daughter, age 61)

Supporting these testimonies, 73.1% of caregivers reported that the DNT was helpful in using RAM, and 66.7% found the DNT helpful in coming up with a care plan (i.e., a detailed plan for customizing the system to specific users). In open-ended responses, 24 participants praised the staff support. However, some participants did not feel motivated to rely on staff, often with worse outcomes, as one shared, “Ifelt like I should have been able to figure it out and when I couldn’t, I stopped asking for help” (open-ended survey response; daughter, age 51)

The results of the case-oriented merged analysis (see Table 5) further reinforced the overarching theme of RAM Adjustment. Three specific cases were identified that represented the complex adaptation process to the RAM system over an 18-month period: high enthusiasm, where the caregiver indicated high utility at each measurement interval; low-to-moderate enthusiasm, which reflected persistent challenges or lack of use of the RAM system; and improved over time, where early problems were resolved or adapted to, and the system became more useful over time.

Benefits of RAM to Caregivers and Care Recipients

Caregivers who responded positively to RAM noted that the system provided useful information, promoted peace of mind, was easy to use, prevented health crises for the person with ADRD, and promoted the person with ADRD’s independent living. RAM was perceived, overall, as moderately useful by caregivers based on the summary/average score on the RAM review checklist (M = 3.73, SD = .89, range = 1 to 5). Two-thirds of participants (66.7%) felt the technology worked well, and 64.2% felt that RAM met their needs.

Sixteen participants noted that information provided by RAM allowed them to better plan their caregiving on a day-to-day basis:

We can tell if she has slept well. If not, we can give the caregiver going in to take care of her a heads up that it has been a difficult night and she will probably very irritable and need naps. (open-ended survey response; daughter-in-law, age 58)

In addition to sending real-time alerts and notifications, RAM tracked patterns of behavior over time. Some participants found that having a record of the care recipient’s activity aided in discussing care with doctors and other professionals. For example, one participant found RAM provided helpful evidence in an investigation, as described in this interview dialogue:

[A]t the time, she accused her caregivers were [inaudible] her, so they reported it to the county...And so the county had to investigate. So we went through that. And one of the things she showed them was how we’re monitoring her and trying to make sure she’s in her home and staying there and why [we] feel that she is safe and that she is ok in her home...They were very impressed. (semi-structured interview; daughter-in-law, age 58)

Participants frequently mentioned that RAM promoted peace of mind or feelings of comfort and confidence, with sixteen participants endorsing this category. For instance, a caregiver shared,

So, biggest benefit was peace of mind. And knowledge. So I at all time that I was away from the house and even when I was in the house, I had knowledge of where was Mom, ...So that was tremendous peace of mind. (Semi-structured interview; daughter, age 54)

Furthermore, 24 participants noted that RAM was easy to use, especially those who were already comfortable with technology. Although ease of use is not a direct benefit of the system, many participants spontaneously mentioned ease of use as a positive aspect of the system that affected their experience with RAM:

It’s easy to use, it’s easy to pull it up and see history. It’s easy to pull up and [say], you know, show me all the alarms for the last two days or see—so it’s easy. Very easy. It’s not that difficult. (Semi-structured interview; daughter-in-law, age 58)

In particular, participants seemed to appreciate that the initial setup was facilitated by the DNT and required little effort on the caregiver’s part; one shared, “It was easy because the technician came out and set it all up (Open-ended survey response; wife, age 75) Consistent with these results, the RAM review checklist responses indicated that 62.0% found RAM easy to use and 72.4% felt that the information provided on how to use RAM was clear.

Four participants reported that RAM prevented health crises for care recipients. For example, one caregiver discussed an instance when her mother fell and was able to get help quickly because she was being monitored:

She fell a couple of times and she pushed the button and so yeah. I was able to hear either from downstairs or—I actually heard her fall, but there was one time that I didn’t hear her fall. And she had fallen. So I was alerted immediately. So that could have been bad... (Semi-structured interview; daughter, age 55)

On the RAM review checklist, only 34.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the alerts generated by RAM helped prevent crises for the care recipient. Instead, several participants felt that RAM was useful for being notified after an emergency, but was not able to prevent such crises.

Seven participants indicated that RAM promoted independent living for care recipients. Persons with ADRD were able to live in their homes longer than they would have been able to otherwise. As one participant said, “We have avoided the nursing home for more than a year now by having the door alerts and the other alerts should she be out of bed or stuck in the bathroom. Very helpful.’ (Open-ended survey response; daughter, age 65)

Some who had a positive experience with RAM mentioned a desire to keep the system after the conclusion of the study. Some even felt anxiety over the idea of giving up the system because it had become an integral part of their caregiving routine. For instance, one participant shared:

We are concerned about what will happen when the study is over. I don’t think we are going to want to give the system up. We have already started discussing it amongst ourselves as to whether or not we can/should afford to keep the system or try to find some other system. (Semi-structured interview; daughter-in-law, age 58)

Despite some participants perceiving RAM benefits, others were lukewarm or negative in their response to RAM. Only a little over half (57.1%) of participants reported that they were satisfied with RAM, and only 59.2% felt it met their care recipient’s needs, emphasizing that some users do not find RAM satisfactory.

Drawbacks and Recommendations for Improvements

Participants identified several areas of concern and gave corresponding suggestions for improvement. Six caregivers complained that the system was too disruptive and intrusive. In some cases, the caregiver was the one experiencing the most disruption, as in the case of the false alarms reported above. In one instance, a care recipient himself felt that the system intruded too much upon his privacy. As his caregiver reported,

And after a while [the care recipient] just saw it as an intrusion, you know, that they were watching him constantly and why do they have to know how many times I go to the bathroom? And why do they have to know when I open the refrigerator door? (Semi-structured interview; wife, age 67)

In addition, nine participants felt the system provided an overwhelming amount of information: “ That’s where I think that it had more than we needed. We didn’t need to see how many times she got into the refrigerator, or how many times she got into the snack cupboard, or stuff like that...” (Semi-structured interview; daughter, age 55)

Several participants (28.0%) felt that parts of the RAM system were confusing and unclear. Comments from interviews and open-ended survey questions supported this result and tended to revolve around the online portal, with eleven participants reporting confusion in their open-ended data. One expressed, “It assumes a high degree of ease of use with technology and it isn’t at all intuitive” (Open-ended survey response; daughter, age 51) Only 41.6% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the online portal for monitoring activity was simple and helpful, and only 23.0% wished they had found out about RAM technology sooner.

Six participants reported a desire for more help with the system, and several recommended that staff reach out proactively to offer help. For instance, one caregiver suggested, “If possible, it might have helped in my situation if there was a follow-up call a few weeks into the start to make sure I didn’t have any questions or problems. That follow-up might have given me the motivation to start using the service “ (Open-ended survey response; son, age 55) In addition to regular check-ins, participants recommended additional training on the system; one shared, “I don’t feel there was enough training done with the system. Using it wasn’t very straightforward and I didn’t make enough time on my own to learn to use the system” (Open-ended survey response; daughter, age 35)

Discussion

We evaluated the acceptability and utility of a RAM system for community-dwelling persons with ADRD and their caregivers over 18-months. Given the long duration of ADRD and the important role of family caregiving in this disease context, evaluating RAM over an extended time frame is critical (Kasper, Freedman, Spillman, & Wolff, 2015). Understanding how technologies are received over time by family caregivers is necessary to better inform the potential efficacy of such systems as well as recommendations for implementation.

Our findings indicate that RAM may supplement family care by assisting independent living and reducing caregiver stress (Williams et al., 2013). The qualitative data show that RAM technology offered several benefits to caregivers (reinforced, in some cases, by the quantitative results) including provision of useful activity information, promotion of peace of mind, and supporting independent living for persons with ADRD. However, successful adoption of RAM was highly dependent on the alignment between caregivers’ needs and the capabilities of the system. For example, disease severity and living arrangement of the primary caregiver had important implications for the perceived utility of RAM. If the person with ADRD required 24-hour in-home supervision, or was still in early stages of ADRD and did not require much supervision, caregivers indicated that RAM was less useful. Still, RAM appears to benefit persons with ADRD in the late-early to moderate stages of the disease. These admittedly preliminary findings necessitate a better understanding of the benefits and cost of the system and its implementation potential. For example, caregivers provided perspectives about what disease stage and living situation is most appropriate for RAM in the qualitative data, but the quantitative analyses did not reveal statistically significant associations between either of these variables and general ratings of utility after 6-months of use. As a larger sample and longer follow-up become available from the parent study (the recruitment goal is 200 dyads), it is hoped that subsequent mixed method analyses will clarify the divergence between the qualitative and quantitative data apparent in this study.

A challenge of RAM for many caregivers was the acclimation period required to customize the system. The qualitative data clearly suggested that RAM is not a “plug and play” technology. Multiple adjustments were needed to calibrate the system, particularly for the diverse living environments and disease contexts facing at-home caregivers. Such customization is likely not achievable via an algorithm or a one-time assessment, but through ongoing interactions with the caregiver, care recipient, and support staff.

Several recommendations emerged to ease the adoption of RAM. First, small, personalized adjustments to RAM can ensure it fits the needs of the users, and a 1–2 month customization period is to be expected. Providers or vendors of RAM technology should offer continued assistance throughout the life cycle of the product, ideally via proactive consults with caregivers. In the current study, the DNT provided extensive information during initial home assessments, but in many instances caregivers (likely due to their competing life responsibilities) did not reach out to staff until problems emerged with the RAM system. Relatedly, family caregivers sometimes felt overwhelmed with the amount of information reported in the online portal, which limited the overall utility of RAM. As optimal chronic disease management programs emphasize, the information provided to family caregivers of persons with ADRD must be succinct and of immediate relevance (Kane, Priester, & Totten, 2005). We would argue that this is a limitation not only of the online portal tested in the current RAM system, but with other technology interventions for older persons in general (Schulz et al., 2014). We advise that caregivers’ and care recipients’ perspectives be included in the development of supportive technologies. It is unclear whether the technology tested in this study underwent a robust, ongoing stakeholder feedback process in its development stages, which occurred well before this evaluation.

In response to these challenges, we modified the research approach of the parent study to include monthly check-in calls with all RAM users, to better prevent frustrations or challenges on the part of ADRD caregivers. This active human engagement can build rapport and encourage continued use of the system by lowering levels of frustration during the period of adjusting and learning to use the system.

Our study has several limitations. First, participants may have hesitated to criticize RAM when speaking directly with the researchers in interviews. However, we believe social desirability bias was curbed by building rapport with interviewees, and by explicitly asking for both positive and negative feedback. Second, participants may not be representative of general population users and thus future experiences may be different from those described here. For example, several participants indicated they felt confident using technology. Studies such as this one may attract “early adopters,” who may be relatively tech-savvy. Similarly, the study participants were homogeneous in terms of caregiver race, gender, and household income, and thus findings may not generalize to more diverse, less affluent populations. The small sample may have hindered the detection of statistically significant effects, and prevented us from empirically testing some research questions that are important to the implementation of RAM. For example, the qualitative results suggest that RAM may be most appropriate for caregiver-care recipient dyads who do not live together; future research should test this proposal quantitatively.

Can innovative, home-based technologies substitute for the provision of either formal or family ADRD care? This is a critical policy and practice question. Shortages in the geriatric workforce are well-documented, from geriatricians to direct care workers (Stone, 2015), and an impending family care gap will threaten developed countries’ reliance on kin as primary caregivers (Gaugler & Kane, 2015; Redfoot et al., 2013). If technologies such as RAM could actually substitute for certain types of human dementia care, a much-needed solution for these potentially disastrous care shortages could emerge. Rigorous, randomized controlled evaluations that examine the effects of such technologies are required to answer such questions. However, this acceptability and utility analysis suggests that RAM does not substitute for the extensive dementia care family members provide.

However, it appears that, at least in some instances, RAM can supplement family caregiving by alleviating some of the challenges of care provision. RAM is likely just one tool in a repertoire of long-term services and supports required to help persons with ADRD remain at home longer and reduce caregivers’ distress. Given the well-documented empirical associations of caregiver distress with negative health and service use outcomes, this is a laudable objective (Gaugler & Kane, 2015; National Academies of Sciences and Engineering, 2016). More work is needed, however, to determine how home-based technologies such as RAM are effectively integrated into care plans (Noel, Kaluzynski, & Templeton, 2017). The findings emphasize the need for ongoing, human consultation to ensure such technologies can operate successfully.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R18 HS022836 from the Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality and K02 AG029480 to Dr. Gaugler. The authors would like to thank the families who contributed their valuable time to this study. The authors also acknowledge Sharon Blume of The Lutheran Home Association and A.R. Weiler of Healthsense, Incorporated for their ongoing assistance. The authors are appreciative of the coordination and data management expertise of Ann Emery, Amanda Weinstein, Aneri Shah, Manisha Shah, and Emily Westphal.

Contributor Information

Lauren L. Mitchell, Department of Psychology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Colleen M. Peterson, Division of Epidemiology, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Shaina Rud, The Alzheimer’s Association, Minnesota-North Dakota Chapter.

Eric Jutkowitz, Department of Health Services, Policy & Practice, Brown University School of Public Health.

Andrielle Sarkinen, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

Sierra Trost, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities.

Carolyn M. Porta, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Jessica M. Finlay, Department of Geography, Environment, and Society, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

Joseph E. Gaugler, Center on Aging, School of Nursing, University of Minnesota-Twin Cities

References

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2017). 2017 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Retrieved from Chicago, IL: http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/2017-facts-and-figures.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Block VA, Pitsch E, Tahir P, Cree BA, Allen DD, & Gelfand JM (2016). Remote physical activity monitoring in neurological disease: A systematic review. PloS One, 11(4), e0154335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossen AL, Kim H, Williams KN, Steinhoff AE, & Strieker M (2015). Emerging roles for telemedicine and smart technologies in dementia care. Smart Homecare Technology and Telehealth, 3, 49–57. doi: 10.2147/shtt.s59500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri S, Kneale L, Le T, Phelan E, Rosenberg D, Thompson H, & Demiris G (2015). Older adults’ perceptions of fall detection devices. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi: 10.1177/0733464815591211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G (2015). Information technology to support aging: Implications for caregiving In Gaugler JE & Kane RL (Eds.), Family caregiving in the new normal. (pp. 211–223). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finch M, Griffin K, & Pacala JT (2017). Reduced healthcare use and apparent savings with passive home monitoring technology: A pilot study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(6), 1301–1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH (2001). Health care triads and dementia care: Integrative framework and future directions. Aging & Mental Health, 5 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), S35–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH, Kercher K, & Burant CJ (2002). Measurement and correlates of family caregiver self-efficacy for managing dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 6(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1080/13607860220126763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman EM, Shih RA, Langa KM, & Hurd MD (2015). U.S. prevalence and predictors of informal caregiving for dementia. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1637–1641. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0510 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, & Kane RL (2015). Family caregiving in the new normal. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Reese M, & Tanler R (2016). Care to Plan: An online tool that offers tailored support to dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist, 56(6), 1161–1174. doi:gnv150 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Yu F, Krichbaum K, & Wyman JF (2009). Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical Care, 47(2), 191–198. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31818457ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel AV, Sims TL, Klassen D, Havey T, & Gaugler JE (2016). Memory Matters: A mixed-methods feasibility study of a mobile aid to stimulate reminiscence in individuals with memory loss. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(7), 15–24. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20160201-04 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd MD, Martorell P, Delavande A, Mullen KJ, & Langa KM (2013). Monetary costs of dementia in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 365(14), 1326–1334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Priester R, & Totten A (2005). Meeting the challenge of chronic illness. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasper JD, Freedman VA, Spillman BC, & Wolff JL (2015). The disproportionate impact of dementia on family and unpaid caregiving to older adults. Health Affairs, 34(10), 1642–1649. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0536 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, & Jaffe MW (1963). Studies of illness in the aged. The Index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. Journal of the American Medical Association, 185, 914–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley AS, McGarry K, Gorges R, & Skinner JS (2015). The burden of health care costs for patients with dementia in the last 5 years of life. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163, 729–736. doi: 10.7326/M15-0381 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R, Gravenstein S, Malarkey WB, & Sheridan J (1996). Chronic stress alters the immune response to influenza virus vaccine in older adults. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(7), 3043–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, & Brody EM (1969). Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. The Gerontologist, 9(3), 179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, & Gallagher-Thompson D (2009). Impact of dementia caregiving: Risks, strains, and growth In Qualls SH & Zarit SH (Eds.), Aging families and caregiving (pp. 85–112). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Martin S, Kelly G, Kernohan WG, McCreight B, & Nugent C (2008). Smart home technologies for health and social care support. Cochrane Database Syst Rev(4), Cd006412. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006412.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JT, Lingler JH, Campbell GB, Hunsaker AE, Hu L, Pires BR, . . .Schulz R (2015). Usability of a wearable camera system for dementia family caregivers. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 6(2), 213–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences and Engineering. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noel MA, Kaluzynski TS, & Templeton VH (2017). Quality dementia care. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(2), 195–212. doi: 10.1177/0733464815589986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, & Skaff MM (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30, 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preusse KC, Mitzner TL, Fausset CB, & Rogers WA (2017). Older adults’ acceptance of activity trackers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 36(2), 127–155. doi: 10.1177/0733464815624151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L (1977). The Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements, 3, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Redfoot D, Feinberg L, & Houser A (2013). The aging of the baby boom and the growing care gap: A look at future declines in the availability offamily caregivers. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2013/baby-boom-and-the-growing-care-gap-insight-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf.

- Rowe MA, Kelly A, Horne C, Lane S, Campbell J, Lehman B, . . . Benito AP (2009). Reducing dangerous nighttime events in persons with dementia by using a nighttime monitoring system. Alzheimers & Dementia, 5(5), 419–426. doi: 10.1016/jjalz.2008.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, & Beach SR (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The Caregiver Health Effects Study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 2215–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Wahl HW, Matthews JT, De Vito Dabbs A, Beach SR, & Czaja SJ (2014). Advancing the aging and technology agenda in gerontology. The Gerontologist, 55(5), 724–734. doi:gnu071 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI (2015). Factors affecting the future of family caregiving in the United States In Gaugler JE & Kane RL (Eds.), Family caregiving in the new normal. (pp. 57–77). San Diego, CA: Elsevier, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Stucki RA, Urwyler P, Rampa L, Muri R, Mosimann UP, & Nef T (2014). A web-based non-intrusive ambient system to measure and classify activities of daily living. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(7), e175. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, Perry MH 3rd, & Morley JE (2006). Comparison of the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder--A pilot study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(11), 900–910. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221510.33817.86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, Uomoto J, Zarit S, & Vitaliano PP (1992). Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist. Psychology and Aging, 7(4), 622–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torkamani M, McDonald L, Saez Aguayo I, Kanios C, Katsanou MN, Madeley L, . . . Jahanshahi M (2014). A randomized controlled pilot study to evaluate a technology platform for the assisted living of people with dementia and their carers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 41(2), 515–523. doi: 10.3233/jad-132156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Felling AJ, Brummelkamp E, Dauzenberg MG, van den Bos GA, & Grol R (1999). Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: a Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(2), 256–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaliano PP, Zhang J, & Scanlan JM (2003). Is caregiving hazardous to one’s physical health? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 946–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild KV, Boise L, Lundell J, & Foucek A (2008). Unobtrusive in-home monitoring of cognitive and physical health: Reactions and perceptions of older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27(2), 181–200. doi: 10.n77/0733464807311435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild KV, Mattek N, Austin D, & Kaye JA (2016). “Are You Sure?”: Lapses in self-reported activities among healthy older adults reporting online. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(6), 627–641. doi: 10.1177/0733464815570667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams K, Arthur A, Niedens M, Moushey L, & Hutfles L (2013). In-home monitoring support for dementia caregivers: A feasibility study. Clinical Nursing Research, 22(2), 139–150. doi: 10.1177/1054773812460545 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Todd PA, & Zarit JM (1986). Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: a longitudinal study. The Gerontologist, 26(3), 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]