Abstract

“Vulnerability” is a key concept for research ethics and public health ethics. This term can be discussed from either a conceptual or a practical perspective. I previously proposed the metaphor of layers to understand how this concept functions from the conceptual perspective in human research. In this paper I will clarify how my analysis includes other definitions of vulnerability. Then, I will take the practical‐ethical perspective, rejecting the usefulness of taxonomies to analyze vulnerabilities. My proposal specifies two steps and provides a procedural guide to help rank layers. I introduce the notion of cascade vulnerability and outline the dispositional nature of layers of vulnerability to underscore the importance of identifying their stimulus condition. In addition, I identify three kinds of obligations and some strategies to implement them.

This strategy outlines the normative force of harmful layers of vulnerability. It offers concrete guidance. It contributes substantial content to the practical sphere but it does not simplify or idealize research subjects, research context or public health challenges.

Keywords: cascade vulnerability, layers of vulnerability, public health ethics, research ethics, research ethics committees, vulnerability

1. INTRODUCTION

The concepts of “vulnerability” and “vulnerable groups” have been widely used in research ethics theory and in public health ethics. Traditionally, the term describes certain kinds of populations deemed worthy of protection.

In 2004 Carole Levine, Ruth Faden, Christine Grady, Dale Hammerschmidt, Lisa Eckenwiler and Jeremy Sugarman criticized this concept. These authors published an article that had a strong impact on bioethics scholars.2 They criticized the excessively broad use of the concept of vulnerability that rendered it too nebulous to be meaningful. They also signalled the concept's stereotyping effect. In that regard, these authors were correct when they pointed out some of these problems. However, their position was overstated.3

In a previous article I distinguished between two spheres of discussion.4 Both spheres are normative as we are dealing with a normative concept. The first one can be conceived of as a conceptual‐ethical sphere. It analyzes the conceptual and normative problems of the concept of vulnerability itself. The second encompasses a practical‐ethical sphere, dealing with the need to protect particular individuals and maintaining the relevance and usefulness of the concept of vulnerability in the evaluation of protocols. I will use the terms “conceptual sphere” and “practical sphere” to shorten the terminology.5 The criticisms of Levine et al. that I hold valid are those that target the conceptual sphere of analysis (i.e., a vacuous use, a stereotyping effect, etc.) but I believe the concept is still very relevant from a practical sphere and these authors have not fully addressed this second sphere. “Vulnerability” has an important normative role and a practical and political force. These challenges can be captured in two fundamental questions, that is:

How should vulnerability be understood? (conceptual question)

How should it be accurately used? (practical question)

Even if these are two different spheres of discussion, they are closely related. Thus, if we cannot offer a fitting answer to the conceptual sphere, we will not be able to defend its practical relevance. That is, if this concept is vacuous and stereotypes populations, it cannot be applied successfully. These serious conceptual problems should be solved in order to restore its utility and normative force. At the same time, the two spheres of discussion present different problems. While the conceptual sphere focuses on the correct analysis and understanding of the concept of vulnerability, the second sphere poses how the concept of vulnerability can be applied to the ethical evaluation of research ethics and public policy design.

In “Elucidating the concept of vulnerability. Layers not Labels”6 I proposed an answer to the first question through the metaphor of layers. This proposal has been accepted and even adopted as a valid strategy (Rogers, Mackenzie and Dodds7 ; Meek Lange, Rogers and Dodds8 ; Macklin9 ; Den Hollander et al.10 ).11 Yet, in my earlier work I did not tackle the second question. Some of the bioethicists that endorsed my previous proposal challenged this lack of analysis and introduced a taxonomy as a way forward.

In this paper, I will first sketch my understanding of vulnerability and ways to deal with some conceptual sphere challenges. I will show that my proposal does not contradict other definitions or accounts of vulnerability. Rather, it includes them. Then, I will introduce a strategy addressing the second challenge that the practical sphere presents. I will identify some key relevant features of the concept of vulnerability (its dispositional character and structure and the possibility of a cascade effect). Finally, I will defend an analysis that implies a two‐step process: an identification step and an evaluation step that includes a ranking process using the previously identified features.

2. THE CONCEPTUAL SPHERE

2.1. The traditional analysis

Since the Belmont Report was published there has been a tendency to label a particular subpopulation vulnerable. I called this approach “the metaphor of labels”.12 Affixing the label “vulnerability” to a particular subpopulation suggests a simplistic answer to a complicated problem. Research situations are often highly complex and influenced by the context and this approach overlooks this fact. Furthermore, a person or a group of persons may experience different kinds of vulnerabilities, and this complexity is ignored if we simply refer to a group of persons as vulnerable.

In “The Limitations of ‘Vulnerability’ as a Protection for Human Research Participants”, Carole Levine et al. present several criticisms of the concept of vulnerability. I will focus on only some of the most relevant ones.13 Carole Levine et al. say that “[…] the concept of vulnerability stereotypes whole categories of individuals, without distinguishing between individuals in the group who indeed might have special characteristics that need to be taken into account and those who do not”.14 These bioethicists are right when they point out this problem. We should first consider that stereotyping implies pinning a label and a content that cannot be easily removed on individuals or groups. And second, stereotyping or labeling persons can harm or wrong them. In addition, this strategy prevents us from identifying levels of vulnerability. The concept is presented in a dichotomous way: you are in or you are out. But among the vulnerable people some might be worse off than others.15 Thus, the lack of flexibility of this conception of vulnerability should be underscored. It leads to a rigid view of the situation and implies conceptual and normative problems.16

Another strong criticism that these bioethicists indicate says that so many categories of people are now considered vulnerable that virtually all potential human subjects are included.17 They quote regulations, the CIOMS 2002 version among other documents, and then explain: “Under one or another of these rubrics, nearly everyone is vulnerable, especially since the benefits of research can never be guaranteed in advance […]. If everyone is vulnerable, then the concept becomes too nebulous to be meaningful”.18 And if this is the case, the concept is not relevant. We could argue that this criticism is too strong as we can deduce general moral obligations for all, even if we cannot deduce special moral obligations for special situations. This is right and it justifies the need for the general protection of human beings in research. However, when we use the notion of vulnerability in research, we try to provide special or specific protections or safeguards for some persons in particular and this cannot be achieved from this ontological perspective. Moreover, this view eventually “naturalizes” vulnerability: if we are all vulnerable and vulnerability is a “natural fact” that we all share, we need not avoid it or protect some persons from it.19 The “labeling” metaphor, as well as the meaningless argument, shows deep problems at the conceptual‐ethical level of analysis with important consequences at a practical level.20 These criticisms need, first, an answer from the heart of the conceptual sphere.

2.2. The structure and functioning of vulnerability: the layer metaphor

In “Elucidating the concept of vulnerability. Layers not Labels”21 I proposed that the concept of vulnerability be conceived via the notion of layers. The metaphor of layers refers to the functioning of the concept. It suggests that there may be multiple and different strata and that they may be acquired, as well as removed, one by one. We do not face “a solid and unique vulnerability” that exhausts the category. There might be different vulnerabilities, different layers operating. These layers may overlap: some of them may be related to problems with informed consent, others to violations of human rights, to social circumstances, or to the characteristics of the person involved.

For example, we could say that the fact of being a woman does not in itself imply that one is vulnerable. A woman living in a country that does not recognize or is intolerant of reproductive rights acquires a layer of vulnerability (that a woman living in other countries that respect such rights does not necessarily have). In turn, an educated and resourceful woman in that same country can overcome some of the consequences of the intolerance of reproductive rights. Yet, a poor woman living in a country that is intolerant of reproductive rights acquires another layer of vulnerability. (She may not have access, for example, to emergency contraceptives and hence will be more susceptible to unwanted pregnancies.) Moreover, an illiterate poor woman in a country that is intolerant of reproductive rights acquires still another layer. And if she is a migrant and does not have her documents in order or if she belongs to the indigenous people, she will acquire increasingly more layers of vulnerabilities. She will suffer under these overlapping layers.22

This concept of vulnerability is a contextual one. I understand it in the sense that the person may no longer be considered vulnerable if the situation changes. For example, a French working woman of reproductive age with middle‐to‐low income may not be vulnerable in a research protocol if she unwillingly gets pregnant (because in her country she has access to emergency contraception or an abortion at the public hospital if she wants). Whereas, if she is in El Salvador (where legal abortion is not allowed for any reason), that same French woman in that same protocol may acquire a layer of vulnerability. She does not become vulnerable, simpliciter.

In addition to the problems mentioned, the label metaphor makes two assumptions. First, it assumes a baseline standard for a default paradigmatic research subject (a mature, moderately well‐educated, clear thinking, literate, self‐supporting person) and second, it makes it possible to identify vulnerabilities in subpopulations in opposition to the paradigm or as defaults of the paradigm. This model is based on an idealization and simplification of research subjects. The problem lies in the nonexistence of these ideal subjects. Moreover, the existence of diverse research subjects within groups challenges the idea of homogeneous groups that share the category of vulnerability. The subpopulation approach assumes that there are necessary and sufficient conditions that populations must fulfil to be considered vulnerable. Instead, the layered way of viewing vulnerability allows it to target differences or variations within the group and to consider different kinds of safeguards or empowerment tools targeting these different features.23

Thus, as there are no longer any labels or rigid categories, there are no fixed subpopulations – people that traditionally could be classified as vulnerable may not be so in a particular situation and vice versa. Interestingly, this conceptual analysis enables us to move away from “usual” or “typical” stereotypes.24

In my proposal, 1) no single standard or ideal exists and there are multiple factors or sources of vulnerability; 2) they are deeply related to the context; and 3) vulnerability is not an essential property of the research subjects or groups per se. In sum, the subpopulation approach and the label metaphor are inadequate because they are tantamount to using the vulnerability concept as a mere slogan, categorizing and stereotyping persons.

2.3. The meaning of vulnerability: definitions and content

In order to apply this concept properly we have to clarify other conceptual issues. “Vulnerability” is an elusive and slippery concept. We must distinguish between the structure and functioning of the concept from its “content” or characterization. We have just explained the structure of the concept. Its functioning is a relational and dynamic one, closely related to the situation under analysis. It is not a category or a label we can simply apply. The layered approach “unpacks” the concept of vulnerability and shows how the concept functions.

Instead, the characterization or content of this concept can be related to several definitions. My proposal of layers does not contradict main accounts or definitions of the concept of vulnerability. To the contrary, it can include them and complement them.25 For example, this is the case of definitions of vulnerability such as the lack of power and the possibility of exploitation26 , the incapability of research subjects to protect their interests27 , or of proposals based on risks, wrongs and harms28 . These different ways of defining vulnerability can be expressed by various coexisting layers. We do not need to choose only one of these definitions. For example, the incapability of research subjects to protect their interests pointed out by the 2002 CIOMS‐WHO definition29 may be translated into layers related with informed consent or into layers related with inadequate guardians to protect participants. Moreover, the 2016 CIOMS version maintains its 2002 definition but it also includes my proposal of layers (although it does not use the word “layer”).30 Yet, there may also be layers having to do with socio‐economic conditions that could put these persons at greater risk or subject them to exploitation (and here we are following Zion's or even Hurst's definitions).31 In addition, note that Hurst explains that “vulnerability as a claim to special protection should be understood as an identifiably increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater wrong”.32 Hurst shows how the concept relates to other concepts such as harms, wrongs, and normative claims. And again, the likelihood of harms and wrongs can be translated into different layers. These different definitions points to different layers, they show different factors that express vulnerability. Thus the structure of the metaphor of layers easily includes different definitions and we are not obliged to select only one of them. This complementary approach of my account has already been suggested by Macklin through a different angle.33 Macklin criticized Hurst's proposal for its narrowness. She claimed that Hurst′s proposal only applies to research and clinical care. Public health cannot be easily included. Macklin argues that Hurst's notion of “a claim to special protection” is too narrow. It cannot account for circumstances in which culture, custom, tradition, and laws make women unable to protect themselves.34 Hurst's analysis has been, thus, “re‐interpreted” by Ruth Macklin, who considers that my approach can complement Hurst's by contributing a contextual and relational aspect to this definition.

Another compatible approach is Kipnis's identification of some “characteristics that are criteria for vulnerability”.35 He endorses a taxonomy with six circumstances: cognitive, juridical, deferential, medical, allocational and infrastructural. For example, the cognitive circumstance asks if the potential participant has the capacity to deliberate on and decide whether or not to participate in the study; the juridical questions whether the potential participant is liable to the authority of others who may have an independent interest in that participation.36 But in another article about vulnerabilities in pediatric research subjects, this author exemplifies seven characteristics. He adds social circumstances.37 This addition jeopardizes the idea of a clear and successful taxonomy. In addition to the reasons I present in the next section, the annexation and identification of an extra category provides yet another justification to avoid taxonomies.38 In Luna 2009 a39 I underscore that Kipnis's analysis goes in the same direction as mine. We both sought an analytical approach instead of working from a subpopulation focus. The main difference between our accounts is that Kipnis proposes a taxonomy (and in the next section I explain that taxonomies are not a good strategy). However, I think that we can follow Kipnis's analytical approach without committing ourselves to taxonomies. These characteristics may serve as a guide. As an open list they may help to identify layers, but they might prove too narrow and rigid if we are to be bound only by them as laid out in a taxonomy.

Thus, my proposal accepts all these different definitions and accounts as they show the manifold angles of this layered approach to vulnerability.

3. THE PRACTICAL SPHERE

The analysis based on layers was well received. In “Vulnerability in Research Ethics: A Way Forward” Meek, Rogers and Dodds say: “What is needed is an approach that, first of all captures Luna's insight that vulnerable research participants inhabit a context generated by the coming together of layers of vulnerability. The approach should make progress towards naming and classifying the layers while remaining sensitive to their possible interactions. Last, such account should identify vulnerability‐related duties”.40 If we return to the two‐sphere distinction I presented in the introduction, it would appear that the conceptual sphere is successful. However, there is still work to be done regarding the second sphere.

In “Why bioethics needs a concept of vulnerability?” Rogers, Mackenzie and Dodds41 say: “We also outline a taxonomy of different kinds of sources of vulnerability which we think is helpful in further specifying the layered approach to vulnerability advocated by Luna “.42 And Meek et al. contend in reference to my proposal: “Unlike Luna's, our approach gives concrete, general guidance to researchers and research ethics committees […]”.43 Thus, while these authors view my approach positively at the conceptual level, they want to move forward and propose an “upgrade” in the practical sphere.

They suggest going beyond by introducing a taxonomy. I do not agree with that proposal: we do not need to name or classify layers and do not need a taxonomy. I think that brings us back to a rigid model.

Taxonomies44 are introduced in order to understand or explain different phenomena. They have their origin in the biological sciences and have been used successfully in other sciences and contexts. Taxonomies may look interesting to research ethics committees (RECs) as they help provide a guide or checklist when analyzing layers of vulnerabilities. However, they can also be misleading. The problem lies in the difficulty of achieving clarity and an orderly classification. Let me illustrate this with an analogy. Reality, I believe, tends to resemble a woman painted by Rubens, a Baroque figure that is proud of the majesty of her voluptuous body. Yet, no corset – despite its strings and fabric – will ever be able to “contain” her abundant flesh!45 And this is the case when we try to classify layers of vulnerabilities. Taxonomies, like corsets, are not enough to categorize reality! The real world is too complex, layers of vulnerability overlap and the context interacts with them. Taxonomies may function better in simpler systems, such as in some biological species ordering, but not so well in open and complex systems like human behavior. Moreover, taxonomies can introduce the illusion of a clear set of categories and suggest a false feeling of order.

In “Rubens, corsets and taxonomies: a response to Meek Lange, Rogers and Dodds” I argued that a) we do not need a taxonomy to classify vulnerabilities, b) Meek et al. do not provide an adequate or successful taxonomy,46 and c) they are unable to link their taxonomy to specific obligations.47 In this paper I will not go into the details of Meek et al.'s analysis or into my criticisms of them.

On reconsidering Meek et al.'s criticisms, I think a practical account identifying layers and duties can be made in a simpler and more useful way. A middle‐ground path that does not include taxonomies may be more helpful for researchers, RECs and policy makers. Instead I will introduce a two‐step process. The first step should identify different layers of vulnerability related with physical problems, consent, dependency, exploitation, socioeconomic situations. I will also underscore some relevant features of layers of vulnerability. The second step will evaluate how we can rank these different layers. The previous identification of layers and their features will help in our evaluation.

3.1. First step: Identification of layers

3.1.1. Relevant features to consider: content and stimulus conditions of layers

During the first step researchers, RECs and policy makers should identify the content of layers of vulnerability that a situation, research or a protocol presents. The different definitions that Zion et al., Hurst or CIOMS48 give may help in this analysis. A proposal like the one that Kipnis offers can also be endorsed if it is taken as a set of open characteristics that can contribute to our analysis and serve to identify layers. However, it should accept additional characteristics if needed. For example, in this first step we should analyze how consent is given, whether social or economic situations are being exploited and generating other layers, whether there are gender issues that may reveal other layers, and so on.

In addition, there are two useful features that may help not just to specify but to prioritize layers of vulnerabilities – as we will see below. The first relevant feature I want to underscore is that layers of vulnerability are dispositions and that the structure and relevant features of dispositions should be taken in consideration in an ethical analysis.

Being vulnerable or suffering a layer of vulnerability reveals that a person might be mistreated/abused/exploited under certain circumstances. Yet, a person need not be mistreated/abused/exploited to be viewed as having a layer of vulnerability or being considered vulnerable.49 Moreover, if she is abused, mistreated or exploited, she is no longer vulnerable because she has already been harmed, abused, and so on.50 It is the possibility of being harmed, mistreated or exploited that is relevant. Hurst's analysis, for example, also assumes this dispositional character when she speaks of an “increased likelihood of incurring additional or greater wrong”.51 Hurst′s proposal fits very well to the dispositional analysis of vulnerability that I am suggesting. This aspect of the concept of vulnerability which is highly relevant; has not been sufficiently analyzed and given the importance it should have (granting some exceptions such as Hurst proposal).

The notion and analysis of dispositions are not new. Yet I want to underscore that we need a careful consideration of the dispositional structure of layers of vulnerability because such analysis can help achieve a thorough ethical evaluation. A classic example of a disposition is the property of being soluble. A sugar lump has the disposition to solubility. That is, it is soluble if placed in water or a liquid. So, the disposition is latent until a specific stimulus condition triggers it. This structure of dispositions dependent on a stimulus condition is quite relevant. In the case of sugar, the stimulus condition will be the event of introducing the solid lump of sugar into any liquid. In the case of layers of vulnerability, there can be many different situations that can trigger a layer of vulnerability. If that stimulus condition does not occur, that layer of vulnerability will never be actualized. I believe this idea of identifying a stimulus condition is crucial to the analysis and evaluation of layers of vulnerability. It is central if we want to correctly protect research subjects and persons. Similarly, just as we have identified the stimulus condition to make the lump of sugar soluble, we should identify the stimulus conditions that trigger a particular layer of vulnerability. If we could do so (and we can eradicate, avoid or minimize said disposition), we will probably be able to avoid the harmful consequences of layers of vulnerability. Yet, if a stimulus condition does not occur or is not probable, the person should still be considered to have a layer of vulnerability. But – as we will see below – when the REC or the policy designer evaluates this situation, that layer will not be a first priority. Rather, it will be other layers that can be triggered more easily. Thus, researchers, RECs, and policy makers should identify the stimulus conditions that can trigger the actualization of a layer of vulnerability in order to design suitable protection mechanisms.

3.1.2. Relevant features to consider: Cascade layers

The second crucial feature is the cascading effect some layers may have. Even if I have argued against some points Meek et al. and Rogers et al. make, I nonetheless consider that they have provided very valuable work. An important contribution by Rogers et al. has to do with the concept of a pathogenic source of vulnerability.52 When they present their taxonomy they say “[…] some responses (to vulnerability) may exacerbate existing vulnerabilities or generate new vulnerabilities. We refer to these as pathogenic vulnerabilities. There are a variety of sources of pathogenic vulnerability. Pathogenic vulnerability may be generated by morally dysfunctional interpersonal and social relationships characterized by disrespect, prejudice or abuse or by socio‐political situations characterized by oppression, domination, repression, injustice, persecution or political violence. For example, people with cognitive disabilities, who are occurrently vulnerable due to their care needs, are susceptible to pathogenic forms of vulnerability, such as sexual abuse by their carers”.53

Along the same line, Durocher et al. refer to Rogers et al.'s proposal: “In contrast, pathogenic vulnerability is a state of being at risk of having situational or inherent vulnerabilities 54 increased or created as a result of ongoing relationships or socio‐political situations that have negative or harmful effects”.55 And they refer to the same passage I quoted. They had previously cited Powers and Faden stating that vulnerabilities may be “cascading and interactive”56 and Fineman explaining that vulnerability in one realm can engender vulnerability in another.57

Thus I will distinguish two ways of characterizing this kind of layer of vulnerability:

Its origin: its generation by morally dysfunctional interpersonal and social relationships (the stance stressed by Rogers et al.);

Its effects: the consequences this kind of layer entails (a chained series of events that lead to harmful consequences).

My proposal underscores the second feature, regardless of its origin. The origin may not necessarily always have a “pathogenic” nature as Roger et al. propose. Yet, the relevance of this distinction lies in the normative force involved in its harmful effects: a potential to “exacerbate existing vulnerabilities or generate new vulnerabilities”. Thus, I hold that what Rogers et al.'s pathogenic source shows is a replication or consecutive deployment of harmful effects: a cascade effect. There might be occasions when its generation by morally dysfunctional relationships might be present. I am not ruling out that possibility. What I want to underscore is the normative force of its effects as the most relevant feature to consider. In addition, I think the term “pathogenic” is misleading because the denomination assimilates this kind of vulnerability to disease and pathology. Rogers et al.'s notion of a pathogenic source is very useful, though it should be formulated in a broader and more neutral sense. I propose we name these layers of vulnerability – following the second feature identified – as a cascade layer of vulnerability and that we seriously consider the devastating power these layers have.

For example, in public health ethics, the lack of an early diagnosis of a rare disease can be considered a cascade‐vulnerability.58 The lack of diagnosis implies lack of knowledge. The situation of uncertainty about these kinds of diseases may last for years with the accompanying anguish this implies for the patient, the family and the mistreatment of the patient (generating other layers of vulnerability). In addition, without a proper diagnosis the illness may evolve, making it impossible for the patient to access proper treatment when eventually diagnosed. Parents may make reproductive decisions, unaware of the high possibility that they might give birth to a child with the same problem, etc… Note that this layer of vulnerability can arise because the person faces a rare disease, and the lack of a proper diagnosis is one of the basic challenges to this kind of illness. Hence, neither abusive relations nor oppressive socio‐political situations are the only situation to trigger this cascading feature.

Cascade layers can frequently be identified in the field of public health, given that they are associated with pre‐existing conditions, context conditions (lack of access to health services, lack of protective laboral laws, etc), thus policies in the realm of public health can eradicate or minimize their effects. But in some cases, this cascading feature may prove very difficult to eradicate even with public laws or strategies. In the case of policy design and the elderly, we can see potentially different layers of vulnerability (economic, communicational, emotional, cognitive, and physical)59 and some of them may be considered cascade‐vulnerabilities. For example, consider this possible layer. Several marriages take place in today's families and new partners may not have an established relationship with the parents‐in‐law or elderly members of the family. In some cases, these new partners may not be very receptive to accommodating and accompanying older family members and this can give rise to a layer of vulnerability for some older people. If this happens, we can call this a relational layer: older people feel alone, isolated, and a burden on their families. If this relational layer occurs, it can also be considered a cascade layer as it can generate psychological harm, such as depression, which at the same time can lead to a loss of appetite or mobility, which, in turn, will probably engender fragility and physical illnesses, other morbidities, and the like.

As we will see in the next section, cascade vulnerabilities have a fundamental role in the process of evaluating the strength or damaging effect of layers. That is why I believe this distinction is key.

In sum, in this first step we should identify the:

Content of layers, that is, different existing layers of vulnerability (we can use different definitions of vulnerability (Zion et al., CIOMS, Hurst), as well as the characteristics that Kipnis proposes);

Stimulus conditions, that is, determining the triggers of layers and the likelihood that they become manifest;

Cascade vulnerabilities, that is, layers that have a “cascade effect”.

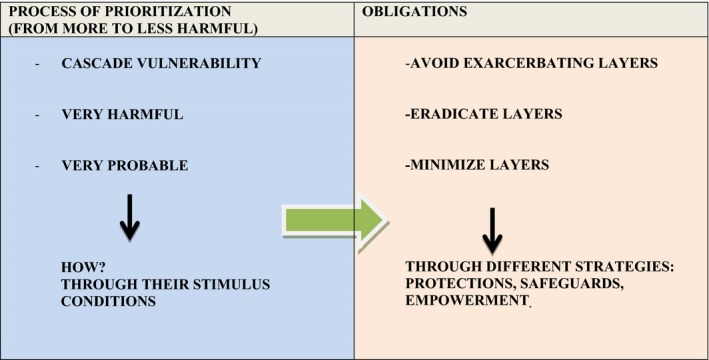

3.2. The second step: evaluation and obligations

During the second step we should evaluate how to rank and prioritize these different layers. We should build on the first step. Based on the previous analysis, I propose a process to rank layers where the most harmful ones take priority. We should assess harms, wrongs and risks involved in the different layers (from physical to psychosocial, including the possibility of exploitation, dependency, abusive patterns, etc.). We should begin with the most harmful layers and move down to the less damaging ones. As we may have several other layers, we should begin by evaluating whether cascade layers exist. Cascade layers are frequently the most harmful. They have a “domino” effect and can trigger several layers. We should give preference to layers with a cascade feature because they exhibit a differential strength and damaging power. As what we will try to do after is to avoid its harmful effects. However, we should weigh several factors: not only the damaging effect but the probability that it will happen. We should balance the possibility of their occurrence and judge how harmful these layers are, as well as the situation under analysis and the threats involved.60 This process can be understood from a coherentist model. There is no lexicographic order.

How should we do this? We should consider the dispositional structure of layers of vulnerability and assess what stimulus conditions can trigger them (their presence and probability of developing). Stimulus conditions relate layers with the context, with the actual situation and possibility of occurrence. If the stimulus conditions are highly probable, they should take priority. These conditions are the ones that actualize the layers of vulnerability and will provoke actual harm. This is why they are the target. We should try to follow the established ranking. Nevertheless, sometimes this will not be feasible as reality can influence just how possible it is to follow strictly the preferred ranking. This ranking of layers should be taken as a procedural and preliminary guide in order to select from where to begin designing adequate safeguards.

Three kinds of obligations61 can be applied to the previous ranking of layers and to the identification of stimulus conditions. Our first obligation is not to worsen the person's or group's situation of vulnerability (be this with a protocol intervention or with a public policy). Thus, we should avoid exacerbating layers of vulnerability. A second obligation consists of the eradication of layers of vulnerability. We should try to eliminate all layers. However, we can only demand this to a reasonable and possible extent. Thus, the third kind of obligation minimizes layers of vulnerability. If –when following the previous obligation‐ we could not eliminate or eradicate these layers, we should consider another alternative; we should find different strategies to minimize layers. We should use the previous ranking of layers as a guide. Finally, these obligations can be expressed through different strategies such as protections, safeguards, as well as empowerment and the generation of autonomy.

Table 1.

Evaluation Step

I believe this process can guide the deliberative thinking and evaluation of researchers, RECs, and public health policies. There is no fixed priority, but a guide that should help assess what our obligations are and from where to begin to tackle them.

3.3. Putting concepts at work: a case

An example that shows how these concepts work is the following: a drug research project conducted with poor women in countries where abortion is illegal. In this case, the possibility of pregnancy functions as a cascade‐vulnerability. As argued in Luna 2009 a62 in the same situation, a woman of a high socioeconomic position will also acquire a layer of vulnerability. There is moral harm when she has to undergo an illegal abortion (even if it is a safe process and she can afford it). In such case this layer will not have the cascade effect, while it will have it in the case of women with scarce resources. In the situation of these poor women, we can easily imagine the anguish of an undesired pregnancy conceived in the middle of a biomedical research project testing new drugs and the fear that the tested drug may have a teratogenic effect on the fetus's development (moreover if this happens early in pregnancy – teratogenic effects frequently occur in the first trimester). If the woman continues the pregnancy because she has no other option, the baby may be born with neurological or other defects that create multiple problems. If she opts for an illegal and unsafe abortion, other harmful consequences might arise: future sterility, morbidity and even mortality. Thus, we should identify whether there are stimulus conditions that may actualize this cascade vulnerability and assess how probable they are. If stimulus conditions are highly probable, this layer should be prioritized (not only is it very harmful with a cascade feature, but it is also quite probable). This is the case, for example, when these women are poor and lack socioeconomic resources, a formal education and, in particular, a sexual education without access to contraception.

If the REC considers the research highly relevant for these women and their community and it meets other ethical conditions,63 but its members are worried about this cascade layer of vulnerability and its stimulus conditions, they should consider how not to trigger this cascade layer. They should assess whether they can eradicate or eliminate such dispositional layer. If they cannot, they should examine ways or strategies to minimize its occurrence. Regarding the possibility of eradication, we should acknowledge that without safe policies to end pregnancies, the possibility of having an unwanted pregnancy will always exist despite special steps to avoid it. We should also understand that researchers or RECs cannot themselves change or issue a suitable law or policy. (Yet, if this were the challenge for a public health agency, officers could take measures to eradicate it). So, inadequate sexual education, the lack of contraception and the lack of emergency contraception are some of the stimulus conditions that can give rise to this cascade layer of vulnerability. As was suggested, it may be quite difficult for RECs’ members to eradicate this layer; yet, they should be able to minimize it. They should consider different strategies: effective protective measures or safeguards, as well as empowerment for these women. For example, a first set of necessary actions to achieve minimization are: explaining and educating about methods to avoid unwanted pregnancies, providing education on the use of contraception and access to it (explaining that it is better to use a double method and offer two birth control methods, as well as the possibility of emergency contraception). They can also propose other complementary actions: speaking with the relevant health officials, writing articles, giving interviews to the press to generate awareness of this restrictive and harmful reproductive health policy. I do not think these last suggestions should be obligatory for researchers or even for RECs; they function as supererogatory actions to be carried out to raise awareness of the problems involved. The RECs cannot eradicate that layer of vulnerability but by requiring researchers to implement at least the first set of protections mentioned, they can minimize it. However, if a REC thinks these strategies do not suffice (because these women will not be able to adhere to and use birth control owing to their partners’ refusal or because it may lead to intra‐family violence, etc.), the REC may 1) reject the protocol or 2) choose not to recruit these kinds of women into the study and set clear conditions for the participation of other women.64 RECs should carefully examine how they evaluate layers, what kinds of provisions and safeguards should be in place for each layer.

4. FINAL THOUGHTS

Let us revisit some previous criticisms. Meek et al. pointed out that my approach: “[…] should make some progress towards naming and classifying the layers while remaining sensitive to their possible interactions. Last such an account should identify vulnerability related duties”.65 As I said earlier, I do not believe that classifying or naming layers is the relevant task. The identification of taxonomies or of types of vulnerabilities is not pertinent. The normative force of harmful layers and avoiding the damage that may ensue is what matters. I propose two steps: an identification step and an evaluation step. I highlight two relevant features of layers (their dispositional character and the possibility of having a cascade effect). These features are used in the evaluation process and I recognize three kinds of obligations. My proposal relies on the power and probability of layers of harms, risks or threats to individuals or groups (this is why cascade vulnerability is so relevant – it involves the generation of new layers and risks). Researchers, RECs and policy makers in the case of public health ethics should be concerned about the eradication and minimization layers, rather than about identifying connections with taxonomies (especially when such typology does not lead to a direct assessment of duties).66

Even though I am offering a procedural guide, it is still essential that we make an exhaustive examination. My proposal forces us to make a moral deliberation and to avoid an easy and automatic analysis using checklists. But it provides valuable guidance on how and what to prioritize and try to tackle first. I believe that RECs, as well as policy makers in the case of public health, should make a thorough ethical analysis. They cannot rely on a list of “supposedly” vulnerable populations because – as was shown – this attitude risks stigmatizing these groups.

This proposal provides a feasible and useful answer to the practical sphere. It suggests a middle‐ground solution between a rigid taxonomy and just layers. It integrates standard definitions and accounts of vulnerability (Zion et al., Hurst, CIOMS, Kipnis). It underscores relevant features of layers and offers a process for ranking and evaluating with explicit obligations to guide researchers, RECs and policy makers. This analysis generates obligations but it is clearer and simpler than the taxonomy‐based proposal. It offers concrete guidance. It contributes substantial content to the practical sphere but it does not simplify or idealize research subjects, research context or public health challenges.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author does not have conflict of interest.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This work was supported by CONICET (Argentina) and by the Fogarty International Center and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R25 TW001605. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I want to thank Ignacio Mastroleo, Ruth Macklin, Joe Millum, Eduardo Rivera López, Carla Saenz for their helpful comments on previous versions of the paper.

Biography

florencia luna, MA, PhD, Principal Researcher at CONICET (National Scientific and Technological Research Council), Argentina. Director of the Program of Bioethics at FLACSO, Argentina. President of the International Association of Bioethics (IAB) (2003‐2005). Member of the Steering Committee of the Global Forum on Bioethics in Research (2005 ‐ 2009) and (2013‐2017). She is Expert for the World Health Organization (WHO) and member of the Scientific and Advisory Committee (STAC) of the Department of Tropical Diseases Research (TDR) from WHO (2011‐2016). She won the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship (2006).

Luna F. Identifying and evaluating layers of vulnerability – a way forward. Developing World Bioeth. 2019; 19: 86–95. 10.1111/dewb.12206

This paper is based on previous articles: Luna F. (2009 a) “Elucidating the Concept of Vulnerability. Layers not Labels” International Journal of Feminist Approaches of Bioethics, vol 2, N 1; Luna F. (2009 b) “La declaración de la UNESCO y la vulnerabilidad, la importancia de la metáfora de las capas” Sobre la Dignidad y los Principios. In: Casado M, editor. Análisis de la Declaración Universal de Bioética y Derechos Humanos de la UNESCO. p. 255‐266, Ed. Civitas, Navarra; Luna F, Vanderpoel S. 2013 “Not the usual suspects: addressing layers of vulnerability” Bioethics, vol 27, Issue 6, p. 325‐332; Luna F. 2014 “Vulnerability”, an interesting concept for public health: the case of older persons”, Public Health Ethics, Volume 7, Issue 2, p. 180‐194. Luna F. (2015) “Rubens, corsets and taxonomies: a response to Meek Lange, Rogers and Dodds” Bioethics, vol 26, number 6, p. 448‐450.

Notes

Levine C, Faden R, Grady C, Hammerschmidt D, Eckenwiler L, Sugarman J; Consortium to Examine Clinical Research Ethics. (2004). The Limitations of “Vulnerability” as a Protection for Human Research Participants, American Journal of Bioethics 4 (3): 44‐49.

Although they do not explicitly say so, they reject this concept. They only accept regulations for research with children (Ibid., p. 44 and 47), and special protections for people with permanent cognitive impairments (Ibid: 48.). They propose “special scrutiny” as an alternative way to provide targeted protection to participants (Ibid: 48). See also Luna (2009 a) op.cit. note 1 p. 128.

Luna (2009 b), op.cit. note 1 p. 258‐9.

In the original article written in Spanish I called them “theoretical ‐ethical” and “political‐ethical” but I was referring to the same distinction. I think this new terminology is clearer. See Ibid: p. 258‐9.

Luna (2009 a), op. cit. note 1, p. 128‐132.

Rogers W, Mackenzie C, Dodds S. (2012). Why bioethics needs a concept of vulnerability? Int J Fem Approaches Bioethics; 5(2): 11‐38.

Meek Lange M, Rogers W, Dodds S. (2013) “Vulnerability in Research Ethics: A Way Forward”, Bioethics: 27:(6): 333‐340.

Macklin R. (2012). A Global Ethics Approach to Vulnerability. International Journal of Feminist Approaches of Bioethics, 5 (2): 64‐81.

Den Hollander G, Browne J, Arhinful D, Van der Graaf R, Klipstein‐Grobusch K. (2016). Power Difference and Risk Perception: Mapping Vulnerability within the Decision Process of Pregnant Women Towards Clinical Trial Participation in an Urban Middle‐Income Setting. Developing World Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12132.

Even the last version of the International Ethical Guidelines for Health Related Research Involving Humans by CIOMS‐WHO (2016) has adopted this strategy. See Van Delden J. and Van der Graaf R. 2016. Revised CIOMS International Ethical Guidelines for Health Related Research Involving Humans, JAMA (6 December)

Luna (2009 a) op.cit. note 1, p. 122‐3.

For a thorough analysis, see Levine, op. cit. note 2, p. 47.

Levine, op. cit. note 2, p. 47.

I thank Carla Saenz for this comment.

Luna. (2009 a) op.cit. note 1, pp. 127‐8.

Levine, op. cit. note 2, p. 46 (my emphasis).

Levine, op. cit. note 2, p. 46 (my emphasis).

Luna, (2009 a) op.cit. note 1, p. 128.

Ibid, pp. 127‐8.

Ibid, p. 121‐139.

Ibid, p. 127‐128.

The layered position can work with individuals but also with subgroups within a population. The relevant point is to consider the different layers that are at play and not just take one characteristic to represent the group as a whole, be it for an individual or a subgroup.

For example, we generally consider poor, pregnant women vulnerable. However, in certain situations this might not be true. The Argentine law allows poor, pregnant women to collect cord blood through the public bank without charging a fee if they need it for another child. Also, they can donate to the public bank and the public system will cover the entire process (even if they need a cord blood transplant for a sibling). So, in this case poor pregnant women are adequately treated and covered. Yet, the pressure that commercial cord blood banks place on middle‐class pregnant women is so strong (through aggressive marketing in gynecologists’ private offices, misleading information, manipulating guilt feelings on the part of the woman for not being a “good mother”, and so on) that it is the middle‐class pregnant woman that may become vulnerable (Luna, 2013 p. 325‐332).

I thank Ignacio Mastroleo for the suggestion to make this point more explicit.

Zion D, Gillam L, Loff B. (2000). The Declaration of Helsinki, CIOMS and the ethics of research on vulnerable populations. Nature Medicine 6: 613–17. p. 615.

Council for International Organizations for Medical Sciences (CIOMS) and World Health Organization (WHO). (2002) (2nd ed.) International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva: CIOMS.

Hurst S. (2008). Vulnerability in Research and Health Care; Describing the elephant in the room? Bioethics, Vol 22: 4.

CIOMS‐WHO op.cit. note 27

The new version does follow my ideas and moves away from the traditional sub‐population approach. In the presentation of the 2016 CIOMS version, the President and Scientific Secretary do acknowledge this and quote one of my articles. Van Delden J. and Van der Graaf R. op. cit. note 11.

Zion, op.cit. note 26.

Hurst, op.cit note 28. p.195.

Macklin R, op.cit note 9, pp 69‐70.

Ibid. pp. 69‐72.

Kipnis K. (2001). Vulnerability in Research Subjects: A Bioethical Taxonomy. In Ethical and Policy Issues in Research Involving Human Research Participants. Bethesda. National Bioethics Advisory Commission. G1‐G12 (p. G4).

The others are: Deferential: Is the candidate‐subject given to patterns of deferential behaviour that may mask an underlying unwillingness to participate? Medical: Has the candidate‐subject been selected, in part, because he or she has a serious health‐related condition for which there are no satisfactory remedies? Allocational: Is the candidate‐subject seriously lacking in important social goods that will be provided as a consequence of his or her participation in research? Infrastructural: Does the political, organizational, economic, and social context of the research setting possess the integrity and resources needed to manage the study? Ibid, (p. G4).

Kipnis K. (2003). Seven Vulnerabilities in the Pediatric Research Subject. Theor Med Bioeth 2003;24: 107‐120.

For further criticism of taxonomies, see Luna 2015 op.cit note 1.

Luna, (2009 a) op cit. note 1 p. 126 and p.134.

Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8 p. 336.

This team of bioethicists wrote several articles in the same vein: I will focus on these two articles: Rogers, op.cit. note 7; and Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8.

Rogers, op.cit. note 7, p. 19.

Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8, p. 337.

The authors sometimes use the term “typology” but they interchange both terms.

See the complete analysis and analogy in Luna 2015, op,cit, note 1.

Rogers and Meek Lange et al.'s proposal speak of three “overlapping categories”: “Inherent sources of vulnerability include our corporeality, our neediness, our dependence on others and our affective and social natures. […] risk of harm or wrongs depends on age, health, gender and disability as well as the person's capacities for resilience, coping and the social supports she may have. Situational sources of vulnerability are context specific and include the personal, social, political, economic or environmental situation of a person or social group. […] Pathogenic sources of vulnerability are a subtype of situational sources that arise from dysfunctional social or personal relationships.” Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8 p. 336. There is a definitional overlap between inherent vulnerability and the situational source of vulnerability. In addition, the third type of source is a subtype of the previous. These, among other reasons, make it quite difficult, if not meaningless, to use the proposed taxonomy. For a deeper analysis, see Luna 2015 , op.cit. note 1.

Luna 2015, op.cit. note 1.

See Section I. 2.b “The meaning of vulnerability: definitions and content”.

I thank Eduardo Rivera López for this comment.

In Spanish we have two different words for this difference: “vulnerable” has the same meaning in Spanish as in English and has this dispositional character; “vulnerado” means that the person has already been harmed. It is no longer a disposition but a fact that the person has already been harmed.

Hurst, op.cit. note 28 p.195 (my emphasis).

See note 46 for the characterization of the authors of different sources of vulnerabilities.

Rogers, op.cit. note 7 p. 25 (my emphasis).

Note that Durocher et al. are not clear about the state or relation among vulnerabilities in their typology. Meek Lange et al. previously said it was a subset of the situational layer of vulnerability. See note 43. See Durocher E, Chung R, Rochon C, Hunt M. (2016). Understanding and Addressing Vulnerability Following the 2010 Haiti Earthquake: Applying a Feminist lens to Examine Perspectives of Haitian and Expatriate Heath Care Providers and Decision‐Makers. Journal of Human Rights Practice 1(20), p.4 (my emphasis) and Luna (2015), op.cit. note 1.

Durocher, ibid. p.4 (my emphasis))

Powers M, Faden R. (2006) Social Justice: The Moral Foundations of Public Health and Health Policy New York: Oxford University Press, p. 69.

Fineman M.(2008). The Vulnerable Subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 20 (1) : 1‐23.

Luna, op.cit. note 24 p. 450.

Luna (2014) op.cit. note 1 p. 184‐186.

For example, if we have to evaluate the risks that some specific protocol imposes on the research subject, we should consider whether the intended protocol presents minimum risk (e.g., taking blood pressure using routine methods). In such case, the many layers may not be so important to remove when compared to a research protocol involving a liver biopsy or other kind of risks to participants. Thus the context or the situation will also be relevant for our evaluation.

I consider some of the obligations Meek Lange et al. proposed (Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8 p. 336‐337).

Luna (2009 a), op.cit. note 1 p. 128.

See CIOMS 2016 regarding pregnant women and research (Gdl 19). Council for International Organizations for Medical Sciences (CIOMS) in collaboration with World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). International Ethical Guidelines for Health‐ Related Research involving Humans. (3rd ed.) Geneva: CIOMS.

Obviously, this last step should be carefully evaluated as it can lead – in some cases – to overprotection (we have seen this reaction profusely in the case of research with pregnant women).

Meek Lange, op.cit. note 8 p. 336.

See my criticism of this in Luna, op.cit. note 24, p. 450.