Abstract

Especially in tropical and developing countries, the clinically relevant protozoa Trypanosoma cruzi (Chagas disease), Trypanosoma brucei (sleeping sickness) and Leishmania species (leishmaniasis) stand out and infect millions of people worldwide leading to critical social-economic implications. Low-income populations are mainly affected by these three illnesses that are neglected by the pharmaceutical industry. Current anti-trypanosomatid drugs present variable efficacy with remarkable side effects that almost lead to treatment discontinuation, justifying a continuous search for alternative compounds that interfere with essential and specific parasite pathways. In this scenario, the triggering of trypanosomatid cell death machinery emerges as a promising approach, although the exact mechanisms involved in unicellular eukaryotes are still unclear as well as the controversial biological importance of programmed cell death (PCD). In this review, the mechanisms of autophagy, apoptosis-like cell death and necrosis found in pathogenic trypanosomatids are discussed, as well as their roles in successful infection. Based on the published genomic and proteomic maps, the panel of trypanosomatid cell death molecules was constructed under different experimental conditions. The lack of PCD molecular regulators and executioners in these parasites up to now has led to cell death being classified as an unregulated process or incidental necrosis, despite all morphological evidence published. In this context, the participation of metacaspases in PCD was also not described, and these proteases play a crucial role in proliferation and differentiation processes. On the other hand, autophagic phenotype has been described in trypanosomatids under a great variety of stress conditions (drugs, starvation, among others) suggesting that this process is involved in the turnover of damaged structures in the protozoa and is not a cell death pathway. Death mechanisms of pathogenic trypanosomatids may be involved in pathogenesis, and the identification of parasite-specific regulators could represent a rational and attractive alternative target for drug development for these neglected diseases.

Facts

The apoptotic phenotype occurs in trypanosomatids, but the precise molecular machinery involved and biological relevance must be further investigated.

Autophagy was described in trypanosomatids, including Atg participation.

Autophagy represents a parasite strategy for survival in stress situations, leading to cell death in extreme conditions.

Open questions

What is the real biological relevance of programmed cell death in protozoa?

Which molecules participate in apoptotic-like activation/regulation in trypanosomatids?

What are the molecular mechanisms involved in protozoan autophagy?

Which molecules trigger/suppress autophagy in these protozoa?

Are apoptotic-like and autophagic pathways good drug targets in trypanosomatids?

Introduction

Neglected tropical diseases describe infective illnesses of poor populations, often in low-income countries, that affect one billion people worldwide1. Among these diseases, trypanosomatids-caused diseases are responsible for high annual mortality in tropical countries. These illnesses also show therapeutic complications, reinforcing the urgency of alternative medicines2–4. In the increased resistance scenario, improved comprehension of exclusive molecular mechanisms or biochemical pathways in these pathogens is an interesting strategy for future drug design. Here, different death processes of the pathogenic trypanosomatids were reviewed.

T. cruzi and Chagas disease

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, and its transmission depends on contamination through triatominae vector faeces, blood transfusions, or even oral and congenital routes5,6. This disease affects eight million Latin America individuals;7 however, due to the immigration of infected people, together with contaminated food ingestion, Chagas disease has emerged in non-endemic countries8,9. This illness presents two clinical phases, including the acute phase characterized by high parasitaemia and a chronic phase that can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Symptomatic chronic phase occurs in approximately 30% of infected people after extensive latency periods. The most remarkable clinical manifestations are observed in chronic patients, including dilated cardiomyopathy and/or digestive alterations10. Chemotherapy is based on two nitrocompounds that are very efficient in acute infections but show limited effectiveness in chronic phase, culminating in severe collateral effects. Chronic patients lose work productivity, representing an annual global economic burden11. The development of alternative drugs is mandatory and includes different classes of compounds and therapeutic strategies12–15.

T. cruzi presents a complex life cycle, including two hosts and different stages of evolution16. In triatomine midgut, epimastigote proliferates and adheres to the epithelium. After epimastigotes´ migration to the insect rectum, a differentiation is triggered by acid and low nutritional environmental conditions, and metacyclic trypomastigote (infective stage) is generated. After triatomine feeding, faeces containing metacyclics reach the mammalian bloodstream through wound openings or mucosa. Once in the vertebrate host, metacyclics can invade all nucleated cells, initiating a differentiation to amastigotes in the intracellular environment. Amastigotes replicate several times before differentiating into bloodstream trypomastigotes. This last stage ruptures the host cell, spreading the infection. The cycle closes when a non-infected triatomine bites an infected mammal16.

T. brucei and sleeping sickness

Sleeping sickness is caused by Trypanosoma brucei, which has two clinically relevant subspecies: T. b. rhodesiense, which is related to acute zoonosis that occasionally infects man; and T. b. gambiense, which is responsible for chronic disease and 98% of all cases. Recently, the WHO estimated that 70 million people are at risk of infection and 30,000 new cases are emerging, despite initiatives to control this disease17,18. Sleeping sickness presents in two distinct phases. During the first phase, T. brucei is concentrated in the bloodstream and lymphatic system, and during the second stage, the protozoa cross the blood-brain barrier and reach the central nervous system, causing progressive neurological damage19. In the absence of adequate treatment, disease usually leads to death following clinical development in six months in the case of rhodesiense disease. Gambiense sleeping sickness, however, generally presents a chronic course up to three years in duration20. Early infections with T. b. rhodesiense and T. b. gambiense are usually treated with suramin and pentamidine, respectively21, while late infections depends on eflornithine or melarsoprol, drugs that have important limitations. Eflornithine is expensive and difficult to administer, whereas melarsoprol is extremely toxic and has demonstrated limited efficacy for T. b. rhodesiense infection17. In the last twenty years, efforts were made to develop a first-line treatment using a combination of melarsoprol and nifurtimox but the resistance especially to melarsoprol was a restriction22.

Non-replicative metacyclic forms initiate the life cycle when the tsetse fly Glossina spp bites the vertebrate, and T. brucei reaches the bloodstream. Differentiation occurs, and rapidly dividing slender forms are generated. Such forms evade the host immune system and avoid antibody binding through antigenic variation23. The cycle arrest induces slender forms to differentiate into short, stumpy parasites. During a tsetse blood meal, stumpy forms reach the fly’s midgut where the parasite differentiates to a proliferative procyclic form, that migrates to the insect salivary gland, resulting in new differentiation now to metacyclic form (infective stage), which closes the cycle24.

Leishmania sp. and leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a sand fly-borne disease caused by Leishmania sp, which infects 12 million people worldwide25. The clinical manifestations of leishmaniasis vary according to the individual host immune response and the infective parasite species26. Three clinical manifestations can be clearly observed: cutaneous (CL), muco-cutaneous (MCL) or visceral (VL, kala azar)27. In CL, an open, self-healing lesion occurs in the location of the sand fly bite. The most serious CL manifestation is the diffuse form where lepromatous lesions are disseminated throughout the skin and are difficult to heal. In MCL, mucosal membranes are affected, leading to facial disfiguration are also present in many cases. VL is the most dangerous clinical manifestation and is fatal if not treated. In this disease form, a strong inflammatory response occurs in the organs, especially the spleen and liver28. The compounds available for the clinical treatment are considered highly toxic, and increased drug resistance also represents a serious problem. For both CL and VL, the first choice drugs are the pentavalent antimonials, but due to the limited efficacy and severe side effects, resistance risk is increased considerably29. The second choice for VL is amphotericin B, which is also toxic and requires intravenous administration30. Today, miltefosine oral administration is restricted to VL treatment in India31, and the high cost, teratogenicity and side effects make this compound far from ideal32. Pentamine has been used in antimony-resistant VL cases as a second-line alternative, but its toxicity usually result in treatment abandonment33.

The life cycle of Leishmania involves two parasite forms and two hosts. In sand fly gut, non-infective procyclic and infective metacyclic promastigotes coexist34. After the insect blood meal, the metacyclic forms infect macrophages, differentiating into amastigotes responsible for parasite proliferation in the vertebrate35. Amastigotes are essentially intracellular and have adapted to survive in an acidic parasitophorous vacuole, whereas metacyclic promastigotes are resistant to the mammalian complement, which is a crucial characteristic to their survival during the initial infection.

Cell death: an overview

Cell death is defined as the collapse of all metabolic processes triggered by chemical, physical or even natural stimuli and can lead to disease depending on the extent of damage36,37. In metazoans, cell death is an essential step for a great variety of physiological events, such as embryogenesis and tissue remodelling38. Almost a half-century ago, a non-accidental aspect of cell death was postulated, related to a sequence of orchestrated events without inflammation known as programmed cell death (PCD)38. More recently, different phenotypes associated with distinct PCD pathways have been proposed, including apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis, which is the most studied.

Apoptosis

The term apoptosis (from the Greek “falling off”) was created in the early 1970s to classify a crucial PCD process that occurs during metazoan embryo growth39. Actually, this pathway is essential for many biological processes, including the removal of non-functional or damaged cells in all tissues40. This early and efficient removal prevents the inflammatory response41. In a pathological scenario, apoptosis plays a fundamental role in cellular defence, composing a mechanism to control pathogen dissemination and cancer development42–45.

In metazoans, the apoptotic machinery is triggered by intrinsic or extrinsic factors36, resulting in activation of cysteine-dependent aspartate-directed proteases known as caspases that lead to the apoptotic phenotype46. The extrinsic pathway starts with the binding of death ligands (FasL, TNF-α, among others), which are soluble and/or present on the effector cells surface, to their respective receptors located in target cells, which triggers the caspase 8 activation and subsequent procaspase 3 cleavage. Following the cascade process, caspase 3 activates endonuclease G, leading to an internucleosomal DNA fragmentation, which is one of the most important hallmarks of apoptosis47,48. Two different mechanisms are related to the intrinsic pathway and involve participation of mitochondria or even the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Activation of mitochondrial pathway derives from the formation of a pore in the outer membrane of this organelle that allows cytochrome c release, as well as the release of other mitochondrial molecules such as endonuclease G, apoptosis induction factor and Bcl2 proteins to the cytoplasm. The interaction among cytochrome c, procaspase 9 and apoptotic protease activating factor 1 forms the apoptosome in the cytoplasm, which promotes the procaspase 9 cleavage, and caspase 9 activates caspase 349,50. The ER pathway depends on caspase 12, but controversial data about the functional role of this pathway in humans up to now make the biological importance of this pathway debatable51,52.

Apoptotic regulation is very complex and includes many anti- and pro-apoptotic molecules that negatively or positively control the pathway. Many of these regulators are members of the Bcl-2 family, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL anti-apoptotic proteins. Other crucial molecular checkpoints are also present in mammalian cells53. Proteins such as the endogenous inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) and the inhibitor of IAP known as smac/DIABLO can change cell fate after triggering cell death signalling54,55. As an example of other apoptotic inhibitors, the overexpression of prohibitin, a protein ubiquitously expressed in mitochondria, partially blocks the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway56, and the inhibition of inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (purine metabolism enzyme) also induces apoptosis57. The precise balance of anti- and pro-apoptotic molecules and activation is crucial for apoptotic success58.

Among the apoptotic phenotypes, caspase activation, typical internucleosomal DNA fragmentation, blebs in the plasma membrane (apoptotic bodies), cell shrinkage, mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) loss and phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure are the most relevant59. Due to the pivotal role of caspases, the gold-standard method is analysis of the specific cleavage of these protease substrates. The evaluation of caspase activity by immunoassays (ELISA, flow cytometry, western blotting) or even the use of the inhibitors and/or specific labelled substrates are also good alternatives. DNA fragmentation can be investigated using terminal dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) technique or electrophoresis (laddering profile in gel). PS externalization (annexin V/ propidium iodide assay) and ΔΨm loss (rhodamine 123, tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester, tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester or derivatives labelling) are also well-employed60,61.

Autophagy

More than fifty years ago, Dr De Duve’s group suggested the presence of a physiological process for self-digestion of non-functional organelles and/or macromolecules named autophagy (from Greek: auto—self and phagein—to eat)62. Autophagy represents a pathway involved in turnover and recycling by removal of damaged cellular components, regulating homeostasis during crucial processes such as cell growth and differentiation63. Autophagy is usually exacerbated under pathological conditions and/or pathogenic infections64,65. On the other hand, continuous autophagic induction can lead to a breakdown of the cellular balance, inducing autophagic cell death66.

The first autophagy-related genes (ATGs) were described in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nearly thirty proteins were identified, and their participation in different points of the pathway was proposed67. Today, the autophagic molecular machinery has been demonstrated to be highly conserved and Atg orthologues are distributed among all eukaryotes, and Atg8 (LC3 in mammals) detection is considered the gold-standard method for monitoring autophagic flux68. Macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) are the three types of autophagy currently described. In macroautophagy (also called autophagy), the intracellular material that will be degraded is surrounded by a double membrane structure known as the phagophore, which forms the autophagosome that directs the cargo for lysosomal degradation69,70. The autophagic initiation is dependent on the serine/threonine protein kinase TOR (target of rapamycin) that functions as a nutrient sensor and on a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI-3K) known as Atg6 (beclin 1 in mammals)62. In microautophagy, the cargo is engulfed by an invagination of the lysosomal membrane, which forms small single-membrane vesicles inside lysosomes, demonstrating an ultrastructural aspect of multivesicular bodies. The absence of specific markers for microautophagy makes this autophagic type poorly described. In CMA, target proteins bind to cytoplasmic chaperones by pentapeptide motifs (KFERQ, VDKFQ or QREFK), making this autophagic type the most selective. The binding of chaperone-substrate to the lysosomal receptor LAMP-2A leads to the receptor dimerization and subsequent channel formation. By this channel, the target molecule enters into the organelle to be degraded62,71.

Since 1964 when the term autophagy was coined, up to now, ultrastructural analysis remains an important tool for the characterization of autophagic phenotypes. As mentioned above, the detection of Atg8/LC3 in microscopy approach (LC3 puncta) and/or by western blotting (LC3-I and LC3-II detection) is the most widespread method to confirm autophagic activity. In parallel, the use of pharmacological inductors or inhibitors (PI-3K inhibitors and/or rapamycin) as well as Atg or related protein knock down or knock out models are also extensively employed68.

Necrosis

Indeed, cells can also die accidentally as in the case of extensive injury due to external stresses such as mechanical disturbance, drugs or infection, and other factors. These stimuli induce random cellular degradation, culminating in the rupture of the plasma membrane, which leads to an intense inflammatory response. Necrosis (in Greek, “dying stage”) is defined as accidental cell death72. The necrotic phenotype involves plasma membrane and calcium homeostasis disruption, as well as lysosomal hydrolase-dependent degradation and cytoplasmic vacuolization. The loss of cellular integrity promotes the release of damaged organelles and/or intracellular molecules and induces inflammation, which is one of the most remarkable differences between necrosis and apoptosis73.

Death processes in trypanosomatids

The role of PCD in multicellular organisms has been extensively described in the last fifty years and is associated with homeostasis regulation. However, despite higher and lower eukaryotes sharing related biochemical mechanisms and molecular events, remarkable differences are clearly observed and should be carefully evaluated74,75. Actually, the biological relevance of PCD for protozoa has not yet been demonstrated. In the following sections, death events in these parasites associated with apoptosis-like cell death, autophagy and/or necrosis as well as their induction by extrinsic or intrinsic factors will be reviewed with a focus on the importance of PCD for the biology of pathogenic trypanosomatids.

Apoptosis-like cell death in trypanosomatids

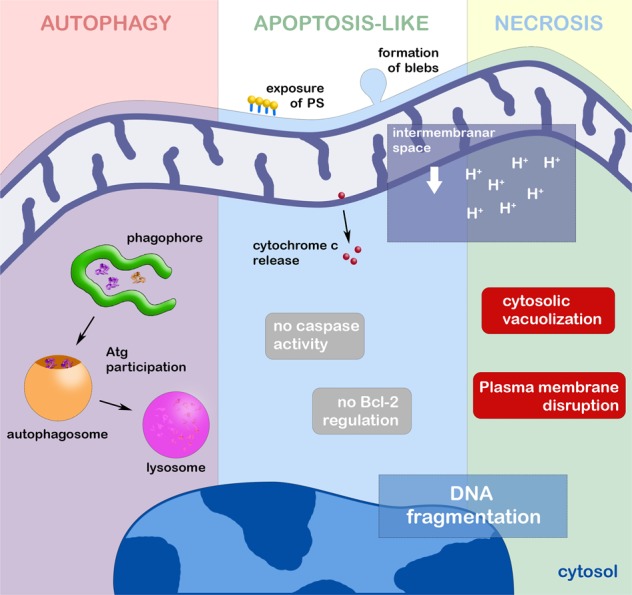

Only three decades after it was first described, PCD was suggested in trypanosomatids. Based on the mammalian apoptotic phenotype, alterations in nuclear morphology and DNA fragmentation were observed during T. cruzi differentiation76. After this first description, many authors have reported apoptotic features induced by stress conditions such as drug treatment, heat shock, and others76–82. Moreover, in pathogenic trypanosomatids, the identification of an apoptosis-like phenotype is restricted to DNA fragmentation, PS externalization, ΔΨm loss and cytochrome c release, which are typical markers of apoptosis in higher eukaryotes (Fig. 1)76,78,83,84. However, pivotal molecules involved in PCD regulation have not yet been described85. These gene sequences could differ from the classical mammalian genes, and the inability to find homologues could represent a problem for the molecular proposal in trypanosomatids.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of three most important cell death processes occurring in pathogenic trypanosomatids.

After the autophagic induction, phagophore elongates from endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi profiles, engulfing non-functional organelles and molecules. After the elongation step, autophagosome is formed, taking the cargo to be degraded in lysosome. All steps are regulated by Atg proteins. Autophagic cell death occurs when the homeostatic balance is broken by the continuous autophagic induction. In trypanosomatids, apoptosis-like cell death is characterized especially by the effect on the mitochondrion, with loss of its membrane potential, and release of cytochrome c to the cytosol. Among other classical apoptotic phenotypes, DNA fragmentation (derived from EndoG activity) and PS exposure were also described in these protozoa. The participation of metacaspases is still debatable as well as the presence of apoptotic Bcl-2 family regulators. Necrotic pathway is evidenced by the intense cytosolic vacuolization, strong effect on the mitochondrion, randomic DNA fragmentation and plasma membrane disruption

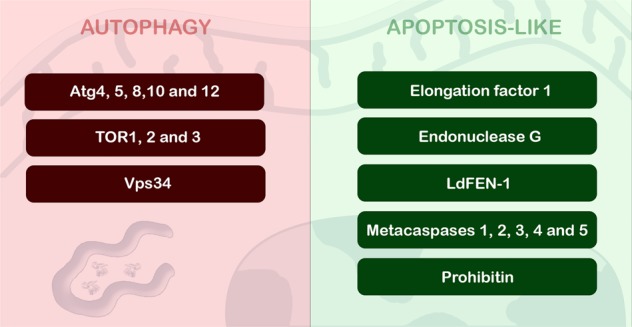

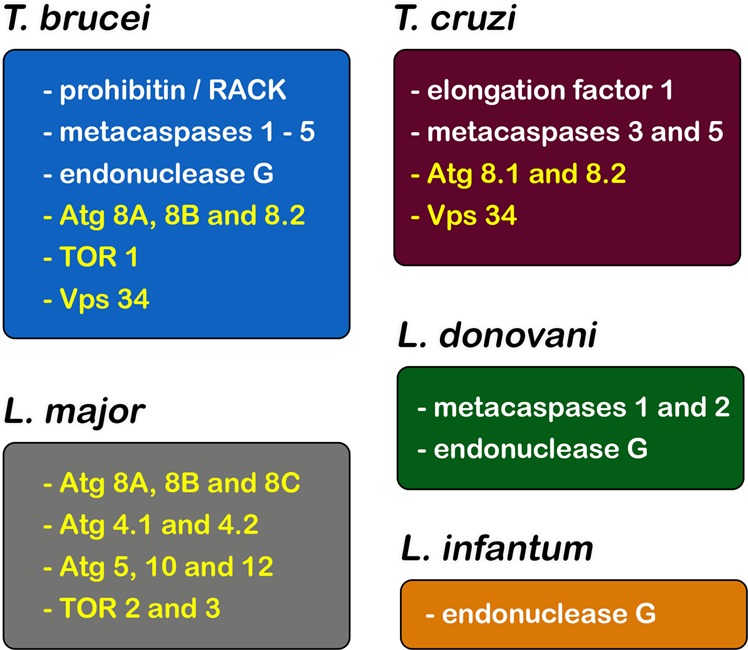

In T. brucei, an apoptotic phenotype was described in parasites incubated with cytokines, drugs and even ROS86–88. The correlation between activated protein kinase C receptor, prohibitin and apoptosis-like cell death was proposed, indicative of convergence between the mammalian and parasite pathways (Figs 2 and 3)86. Despite metacaspases and mammalian caspases sharing similar folding patterns, the presence of evidence regarding caspase-like activity on their respective substrates has not been detected in pathogenic trypanosomatids83,89,90. In this context, the detection of the self-proteolytic activity of L. major metacaspase was demonstrated in vitro (Figs 2 and 3)91. Cleavage of crucial substrates by metacaspases and its involvement in PCD has not been reported thus far92,93. Furthermore, the participation of metacaspases has been associated with parasite proliferation and differentiation93–95.

Fig. 2. Autophagic and apoptotic molecules detected in pathogenic trypanosomatids.

Five Atg proteins, Vps34 and also three TOR were described and associated with autophagic process in these parasites. In relation to apoptosis-like, endonuclease G, prohibitin, elongation factor 1 and LdFEN-1 have been associated to this death machinery. The importance of metacaspases for apoptosis-like of trypanosomatids is too controversial, and their molecular function is still under investigation

Fig. 3. Distribution of cell death molecules in different species of pathogenic trypanosomatids.

Proteins associated with apoptosis-like (white) and autophagy (yellow). Apoptosis-related molecules such as endonuclease G and metacaspases were mainly studied in T. brucei and T. cruzi, followed by L. donovani and L. infantum. On the other hand, autophagic molecules were extensively assessed in L. major, and also in T. brucei and T. cruzi

The classical apoptotic features described above could be detected in Leishmania sp. under non-physiological conditions such as drug treatment, nutritional deprivation or oxidative stress74,83,88,90,96,97. DNA fragmentation was detected in L. major, L. mexicana and L. donovani promastigotes and axenic amastigotes in total DNA electrophoresis, but the ladder pattern suggestive of internucleosomal cleavage was unclear. The presence of Mg2+- and Ca2+-independent endonucleases also helps to support the hypothesis of a classical DNA fragmentation pattern78,89,98. Furthermore, a metacaspase-independent death pathway has been described and involves endonuclease G-like and mitochondria (Figs 2 and 3)96,98,99. The involvement of inosine 5′ monophosphate dehydrogenase in an apoptosis-like cell death phenotype was also suggested in L. amazonensis after heat shock based on PS exposure and mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 1), but further analysis regarding the molecular mechanism must be performed before any conclusions are made100.

ROS generation and mitochondria also play an essential role in the PCD phenotype in unicellular eukaryotes101. Hydrogen peroxide leads to ΔΨm loss and DNA fragmentation in L. donovani. Partial reversion of the phenotype by classical caspase inhibitors and the detection of caspase-like activity also reinforced these findings83,96, but careful analysis of the proteolytic activity of metacaspases must be conducted to confirm their role in the cell death pathway. The imbalance of Ca2+ influx in the mitochondrion triggers oxidative stress in trypanosomatids102, and prostaglandin D2 induces ROS production in T. brucei, which leads to an apoptotic-like cell death phenotype that is partially reverted by antioxidants84,103. In the following sections, oxidative involvement in autophagy and necrosis will also be debated75,104. On the other hand, transfection with the mammalian Bcl-XL gene partially reverted apoptosis-like cell death in L. infantum after heat shock despite a lack of detection of caspase-like activity105. Up to now, Bcl-2 family members have not been identified in pathogenic trypanosomatids (Fig. 1)86. Further investigation regarding apoptosis-like cell death regulatory steps must be performed. Comparisons between mammalian and protozoan death phenotypes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison between death phenotypes in metazoans and trypanosomatids

| Phenotypes | Metazoans | Trypanosomatids |

|---|---|---|

| Apoptosis | ||

| no inflammatory response | + | naa |

| proteolytic activity of caspases | + | ndb |

| Δψm dissipation | + | + |

| cytochrome c release | + | + |

| Bcl-2 proteins regulation | + | nd |

| blebs formation in plasma membrane | + | + |

| internucleosomal DNA fragmentation | + | na |

| PS exposure | + | + |

| cell shrinkage | + | + |

| Autophagy | ||

| autophagosomes formation | + | + |

| Atgs regulation | + | + |

| TOR and PI-3K participation | + | + |

| degradation in lysosomes | + | + |

| presence of KFERQ, QREFK or VDKFQ motifs in the target protein (only in CMA) | + | nd |

| Necrosis | ||

| inflammatory response | + | na |

| plasma membrane rupture | + | + |

| cytosolic vacuolization | + | + |

| calcium misbalance | + | + |

| lysosomal enzymes release | + | + |

ana: not applicable

bnd: not determined

Autophagy in trypanosomatids

In trypanosomatids, the first ultrastructural description of an autophagic process occurred more than four decades ago in T. brucei106. Stress conditions, especially drug treatment, frequently induced an autophagic phenotype such as myelin-like structures, multivesicular bodies and an increase in autophagosome number82,107–111. The most recurrent autophagic evidence found in stressed parasites was myelin-like structures and concentric membrane structures morphologically similar to phagophores, the isolated membrane that originates autophagosomes (Fig. 1). ER profiles are usually reported as the main membrane resource for phagophores, including in trypanosomatids. In T. cruzi epimastigotes, the participation of reservosomes (lysosome-related organelles) in autophagy has been proposed, and close contact between these organelles and ER profiles was also observed in the autophagic phenotype84,110.

The autophagic molecular machinery, including ATG homologues, is partially present in trypanosomatids, but many components of the yeast pathway are lacking in protozoa. Bioinformatic analysis showed genes that participate in phagophore expansion to degrade the autophagosome content, including the complete Atg8 conjugation system (Atg3, Atg4, Atg7 and Atg8)112. In 2008, Alvarez and co-workers demonstrated for the first time the biological role of Atg8 in T. cruzi, and autophagy was associated with a crucial step in parasite differentiation, which was essential for the success of this protozoa life cycle. This study pointed to the presence of two Atg8 (TcAtg8.1 and TcAtg8.2) and two Atg4 (Atg4.1 and Atg4.2) homologues. Interestingly, both Atg4 homologues, but only Atg8.1, recovered autophagy in knockout yeast strains. When the parasite was submitted to starvation, Atg8.1 was located in autophagosomes, validating this protein as an autophagosomal marker, as had already been done in mammals and yeast70. Four isoforms of Atg8 have been described in other pathogenic trypanosomatids (Atg8, Atg8A, Atg8B and Atg8C), and the dynamics of these molecules are also controlled by the same two Atg4 isoforms113–115. Moreover, the Atg12 conjugation system is defective in these parasites, and different genes are absent, such as ATG5, ATG10 and ATG12 (Figs 2 and 3)112,116. TOR kinases (TOR1 and TOR2) and their respective complexes (TORC1 and TORC2) were present in the genomes of pathogenic trypanosomatids, but their biological functions are still unclear due to the differences in molecular behaviour, subcellular localization and susceptibility to rapamycin117. Rapamycin induced the formation of a huge number of autophagosomes by TORC2 inhibition in T. brucei, thereby impairing parasite proliferation, but did not inhibit TORC1117,118. Additionally, in starved T. cruzi, TcVps15 overexpression increased the number of autophagosomes, suggesting a regulatory role for this enzyme in the control of TcVps34 enzymatic activity (Figs 2 and 3)119. Curiously, a great number of large-scale proteomic studies in trypanosomatids did not find evidence of autophagic proteins under nutritional stress (during metacyclogenesis, for example), strongly suggesting the inability to find homologues of Atgs in these parasites120.

The fundamental role of autophagy in the differentiation processes of trypanosomatids has been proposed, as well as in phospholipid homeostasis and mitochondrial functionality70,121–123. In 2012, Williams and colleagues produced L. major promastigotes lacking Atg5, and such mutants did not form autophagosomes but were still viable. Curiously, a strong reduction in virulence of these parasites was observed in vitro and in vivo, together with peculiar morphological changes, especially in flagellar length. In these mutants, a remarkable increase in phosphatidylethanolamine levels was detected as well as mitochondrial swelling with a decrease in this organelle membrane potential and high ROS content, suggestive of mitochondrial dysfunction derived from conjugation of mitochondrial PE to ATG8 for autophagosome biogenesis122. During metacyclogenesis, parasites are submitted to nutritional stress, a classical model of autophagic induction. The participation of this pathway in the control of virulence and infectivity to the mammalian host was demonstrated121. Especially in the triatominae rectum, nutritional deprivation represents a fundamental step for T. cruzi differentiation and has been previously shown to reduce Atg8.1 levels during metacyclogenesis70,84. However, further elucidation of the molecular machinery involved must be performed.

Selective autophagy was also reported in pathogenic trypanosomatids. T. brucei bloodstream forms differentiate into procyclic forms, and the selective degradation of glycosomes was postulated to occur during this process. Due to the biological importance of this peroxisome-like organelle for the glycolytic pathway, its degradation directly affects parasite bioenergetics, reinforcing the relevance of pexophagy in these protozoa124,125. It is well-known that environmental conditions (temperature, pH, among others) as well as nutritional availability (sources of energetic substrates) are different in distinct hosts, leading to changes in the parasite metabolic pathways, including ATP production116. Some of these metabolic adaptations could be regulated by autophagy. For example, the acidification of acidocalcisomes (organelles involved in polyphosphate metabolism) was directly related to autophagic regulation. In T. brucei, autophagy was blocked by the impairment of acidocalcisome biogenesis, suggesting that this organelle participates in this pathway126,127.

As described for trypanosomes, metacyclogenesis of Leishmania sp. is also dependent on the presence of autophagosomes128,129. The impairment of autophagic flux by Atg4.2 deletion and subsequent lipidated Atg8 accumulation has been associated with the reduction of promastigotes during differentiation119. Likewise, the involvement of autophagy was also reported during L. mexicana differentiation of metacyclic promastigotes into amastigotes128. The participation of lysosome-like organelles known as megasomes in the differentiation of this parasite has been described, as well as the proteolytic activity of two megasomal cysteine peptidases (CPA and CPB) related to the autophagic process. Deletion of these proteases deeply compromises the differentiation to amastigotes, leading to a notable increase in autophagosome number116,128. Table 1 also describes autophagic phenotypes observed in mammals and pathogenic trypanosomatids.

The term “autophagic cell death” is usually employed for situations where homeostatic control is lost and autophagy is exacerbated to degrade damaged structures, macromolecules or organelles37. One of the most usual experimental protocols to analyse autophagic cell death is preincubation with PI-3K inhibitors (wortmannin and 3-methyladenine), which are used to block the initial steps of this pathway, before the autophagic stimulus is initiated. Using this experimental design, our group showed that T. cruzi autophagy is part of the mechanism of action of naphthoimidazoles and involves the Atg8 conjugation system. However, the molecular mechanisms of death deserve more investigation62,110.

Necrosis in trypanosomatids

Similar to the process that occurs in mammalian cells, necrotic cell death is poorly investigated in trypanosomatids. The main reason is the uncontrolled and accidental profile of this process, as it is always the endpoint of all death processes (PCD or not). It is well-established that plasma membrane disruption is the most characteristic necrotic event (Fig. 1) and is triggered by chemical and/or physical stress73. In vitro, in the absence of host phagocytosis, the parasites will rupture necessarily, no matter what stimulus or death process is induced. Preclinical tests have shown parasite lysis as the endpoint in the mode of action of a great variety of anti-trypanosomatid drugs28,85,130–133.

Activation of the complement cascade usually induces necrosis in trypanosomatids. It was previously reported that the binding of lectins to surface molecules of the parasite, such as glycosylated proteins or lipophosphoglycans, in the case of T. cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes and Leishmania sp. promastigotes, respectively, triggered necrosis134,135. Furthermore, different evasion mechanisms are present in trypanosomatids to avoid the complement system. For example, the huge repertoire of variant surface glycoproteins provides a coat for T. brucei, allowing it to evade host immune defences136.

Another relevant issue concerning necrosis in these protozoa is related to oxidative stress. One of the regulators of ROS-dependent cell death is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. In T. cruzi, the participation of mitochondrial cyclophilin as a component of this permeability pore was previously demonstrated. Incubation with hydrogen peroxide led to a loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and probably subsequent extensive lipid peroxidation in the parasite137. Depending on the ROS levels produced, protozoa lysis and consequent necrosis will occur.

Conclusions

Even though PCD has been the subject of a great number of studies in trypanosomatids, the precise biochemical and molecular processes involved as well as the regulatory steps required are still unknown. The lack of key molecules in these parasites points to the existence of PCD as controversial and makes the term “apoptosis-like” more opportune84,138. Up to now, no evidence showing proteolytic activity of metacaspases in PCD events has been presented. Actually, all deep studies about orthologues of these proteases in trypanosomatids presented no correlation with death mechanisms, and their activity has been associated with proliferation and differentiation85,94,139. Indeed, remarkable differences between higher eukaryotes and trypanosomatids were detected, including a lack of key genes that encode molecular executioners and/or regulators in these protozoa85. Another crucial point was the inability to find homologues of cell death genes probably due to the low sequence similarities to metazoans. Previous data showed a conserved aspect of PCD, indicating its pivotal role in these species’ survival during evolution. Notwithstanding, in lower eukaryotes such as trypanosomatids, the identified death molecular mechanisms have been related to a divergent evolutionary event based on a huge phylogenetic analysis of death molecules140. Comparing protozoa and metazoans, important differences (including the absence of PCD molecules) were found in these parasites141. Despite all morphological evidence, up to the convincing identification of the executioners, Proto and co-workers (2013) classify this protozoan cell death as an unregulated process or incidental necrosis85.

Furthermore, the physiological relevance of this cell death type for pathogenic trypanosomatids is still an unanswered question. Altruism has been proposed as a hypothesis to explain PCD in unicellular eukaryotes84. Crucial events such as clonal selection, population density control or even evasion of host immune defences were associated with PCD, directly supporting the parasite life cycle62,78,89,142. It was suggested that trypanosomatid colonization is regulated by nutritional availability and protozoa cell death in the insect gut, controlling the parasite super-population and invertebrate host death74,84. Invertebrate forms of L. amazonensis or T. cruzi could suffer PCD to facilitate the infection by avoiding parasitic necrosis and immune response exacerbation76,78. As the altruistic hypothesis is difficult to prove, the uncontrolled status of cell death should be considered as the only possibility.

A critical autophagic role in cell death has also been proposed, but the regulatory steps involved are unknown107,110,143. In unicellular eukaryotes, few studies about autophagy-related events have been performed, and the molecular pathways are still unclear. Indeed, the autophagic process contributes to the maintenance of trypanosomatid homeostasis, despite the description of its participation in dying parasites. The imbalance in autophagic turnover of essential cellular factors could trigger death signalling; however, activation of this machinery could result from general and unspecific damage143,144. The recycling of non-functional and/or injured cellular components represents a central step in the direction of trypanosomatid survival, explaining the appearance of autophagic phenotypes induced by distinct drugs, as a parasite attempts to survive in stress conditions by degrading damaged structures109,143,145,146. On the other hand, the existence of a novel and alternative PCD pathway as well as cross-talk between more than one cell death process cannot be discarded in these protozoa, but it must be proved molecularly58,66,75,109,110.

Unfortunately, no biochemical or molecular tools for protozoa PCD characterization are commercially available. The absence of specific antibodies or enzymatic kits for the identification of apoptotic-like or autophagic events delays the development of more studies in this area. Furthermore, the death mechanisms of pathogenic trypanosomatids may have implications in their pathogenesis and deserve more investigation in the near future.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo a Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Papes/Fundação Oswaldo Cruz (Fiocruz) and Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for financial support. I am especially grateful to Dra. Solange L. De Castro for her critical reading.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by G.M. Fimia

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Neglected tropical diseases [Internet]. 2018 [cited July 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/diseases/en/.

- 2.Salomão K, Menna-Barreto RF, de Castro SL. Stairway to heaven or hell? perspectives and limitations of chagas disease chemotherapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016;16:2266–2289. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160413125049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen DR, Mocerino M. A Brief review of drug discovery research for human african trypanosomiasis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017;24:701–717. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170120160034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alcântara LM, Ferreira TCS, Gadelha FR, Miguel DC. Challenges in drug discovery targeting TriTryp diseases with an emphasis on leishmaniasis. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2018;8:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steindel M, et al. Characterization of Trypanosoma cruzi isolated from humans, vectors, and animal reservoirs following an outbreak of acute human Chagas disease in Santa Catarina State, Brazil. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;60:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dias JC, Amato Neto V, Luna EJ. Alternative transmission mechanisms of Trypanosoma cruzi in Brazil and proposals for their prevention. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2011;44:375–379. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822011005000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.First WHO report on neglected tropical diseases. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases. [Internet]. 2010 [cited July 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/2010report/en/.

- 8.Coura JR, Dias JC. Epidemiology, control and surveillance of Chagas disease: 100 years after its discovery. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:31–40. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmunis GA, Yadon ZE. Chagas disease: a Latin American health problem becoming a world health problem. Acta Trop. 2010;115:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rassi A, Marcondes de Rezende J. American trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease) Infect. Dis. Clin. North Am. 2012;26:275–291. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee BY, Bacon KM, Bottazzi ME, Hotez PJ. Global economic burden of Chagas disease: a computational simulation model. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013;13:342–348. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70002-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKerrow JH, et al. Two approaches to discovering and developing new drugs for Chagas disease. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:263–269. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000900034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moraes CB, et al. Nitroheterocyclic compounds are more efficacious than CYP51 inhibitors against Trypanosoma cruzi: implications for Chagas disease drug discovery and development. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4703. doi: 10.1038/srep04703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molina I, et al. Randomized trial of posaconazole and benznidazole for chronic Chagas’ disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:1899–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbina JA. Recent clinical trials for the etiological treatment of chronic chagas disease: advances, challenges and perspectives. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2014;62:149–156. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Souza W. From the cell biology to the development of new chemotherapeutic approaches against trypanosomatids: dreams and reality. Kinetoplastid Biol. Dis. 2002;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simarro PP, Diarra A, Ruiz Postigo JA, Franco JR, Jannin JG. The human African trypanosomiasis control and surveillance programme of the World Health Organization 2000-2009: the way forward. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2011;5:e1007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Human African trypanosomiasis [Internet]. 2018 [cited July 2018]. Available from: http://www.who.int/trypanosomiasis_african/en/.

- 19.Kennedy PG. Clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:186–194. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70296-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Franco JR, Simarro PP, Diarra A, Jannin JG. Epidemiology of human African trypanosomiasis. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014;6:257–275. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S39728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steverding D. The development of drugs for treatment of sleeping sickness: a historical review. Parasit. Vectors. 2010;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barrett MP, Vincent IM, Burchmore RJ, Kazibwe AJ, Matovu E. Drug resistance in human African trypanosomiasis. Future Microbiol. 2011;6:1037–1047. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horn D. Antigenic variation in African trypanosomes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2014;195:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matthews KR. The developmental cell biology of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118:283–290. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Organization WH. Research priorities for the environment, agriculture and infectious diseases of poverty. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2013;976:1–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet. 2005;366:1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desjeux P. Leishmaniasis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:692. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barrett MP, Croft SL. Management of trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Br. Med. Bull. 2012;104:175–196. doi: 10.1093/bmb/lds031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundar S, Chakravarty J. Leishmaniasis: an update of current pharmacotherapy. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2012;14:53–63. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.755515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yardley V, Croft SL. Activity of liposomal amphotericin B against experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1997;41:752–756. doi: 10.1128/AAC.41.4.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sundar S, et al. Efficacy of miltefosine in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis in India after a decade of use. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:543–550. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundar S, Chakravarty J. Investigational drugs for visceral leishmaniasis. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2014;24:43–59. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.954035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olliaro PL. Drug combinations for visceral leishmaniasis. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2010;23:595–602. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833fca9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bates PA, Rogers ME. New insights into the developmental biology and transmission mechanisms of Leishmania. Curr. Mol. Med. 2004;4:601–609. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang KP, Dwyer DM. Multiplication of a human parasite (Leishmania donovani) in phagolysosomes of hamster macrophages in vitro. Science. 1976;193:678–680. doi: 10.1126/science.948742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crile G, Dolley DH. On the effect of complete anemia of the central nervous system in dogs resuscitated after relative death. J. Exp. Med. 1908;10:782–810. doi: 10.1084/jem.10.6.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smirlis D, et al. Targeting essential pathways in trypanosomatids gives insights into protozoan mechanisms of cell death. Parasit. Vectors. 2010;3:107. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-3-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lockshin RA, Williams CM. Programmed cell death. Cytology of degeneration in the intersegmental muscles of the pernyi silkmoth. J. Insect Physiol. 1965;11:123–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(65)90099-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerr JF. History of the events leading to the formulation of the apoptosis concept. Toxicology. 2002;181-182:471–474. doi: 10.1016/S0300-483X(02)00457-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116:205–219. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Voll RE, et al. Immunosuppressive effects of apoptotic cells. Nature. 1997;390:350–351. doi: 10.1038/37022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams GT. Programmed cell death: apoptosis and oncogenesis. Cell. 1991;65:1097–1098. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90002-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams GT. Programmed cell death: a fundamental protective response to pathogens. Trends Microbiol. 1994;2:463–464. doi: 10.1016/0966-842X(94)90648-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rich T, Allen RL, Wyllie AH. Defying death after DNA damage. Nature. 2000;407:777–783. doi: 10.1038/35037717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DosReis GA, Barcinski MA. Apoptosis and parasitism: from the parasite to the host immune response. Adv. Parasitol. 2001;49:133–161. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(01)49039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steller H. Mechanisms and genes of cellular suicide. Science. 1995;267:1445–1449. doi: 10.1126/science.7878463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muzio M, et al. FLICE, a novel FADD-homologous ICE/CED-3-like protease, is recruited to the CD95 (Fas/APO-1) death-inducing signaling complex. Cell. 1996;85:817–827. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81266-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jänicke RU, Sprengart ML, Wati MR, Porter AG. Caspase-3 is required for DNA fragmentation and morphological changes associated with apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:9357–9360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.16.9357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, Newmeyer DD. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kroemer G, Reed JC. Mitochondrial control of cell death. Nat. Med. 2000;6:513–519. doi: 10.1038/74994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nakagawa T, et al. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-β. Nature. 2000;403:98. doi: 10.1038/47513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fischer H, Koenig U, Eckhart L, Tschachler E. Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;293:722–726. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chao DT, Korsmeyer SJ. BCL-2 family: regulators of cell death. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:395–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chai J, et al. Structural and biochemical basis of apoptotic activation by Smac/DIABLO. Nature. 2000;406:855–862. doi: 10.1038/35022514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Adrain C, Creagh EM, Martin SJ. Apoptosis-associated release of Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria requires active caspases and is blocked by Bcl-2. EMBO J. 2001;20:6627–6636. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.23.6627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peng YT, Chen P, Ouyang RY, Song L. Multifaceted role of prohibitin in cell survival and apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2015;20:1135–1149. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1143-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jayaram HN, Cooney DA, Grusch M, Krupitza G. Consequences of IMP dehydrogenase inhibition, and its relationship to cancer and apoptosis. Curr. Med. Chem. 1999;6:561–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Assunção Guimarães C, Linden R. Programmed cell deaths. Apoptosis and alternative deathstyles. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:1638–1650. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sgonc R, Wick G. Methods for the detection of apoptosis. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1994;105:327–332. doi: 10.1159/000236777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Menna-Barreto, R. F. S. & DeCastro, S. L. Cell Death: Autophagy, Apoptosis and necrosis Ch. 11 (IntechOpen, Rijeka 2015).

- 62.Duszenko M, et al. Autophagy in protists. Autophagy. 2011;7:127–158. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.2.13310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. Autophagosomes: biogenesis from scratch? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:415–422. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kirkegaard K, Taylor MP, Jackson WT. Cellular autophagy: surrender, avoidance and subversion by microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;2:301–314. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Swanson MS. Autophagy: eating for good health. J. Immunol. 2006;177:4945–4951. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.4945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:2679–2688. doi: 10.1172/JCI26390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klionsky DJ, et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00296-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Klionsky DJ, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition. Autophagy. 2016;12:1–222. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alvarez VE, et al. Blocking autophagy to prevent parasite differentiation: a possible new strategy for fighting parasitic infections? Autophagy. 2008;4:361–363. doi: 10.4161/auto.5592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bejarano E, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010;7:29–39. doi: 10.1513/pats.200909-102JS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Proskuryakov SY, Konoplyannikov AG, Gabai VL. Necrosis: a specific form of programmed cell death? Exp. Cell Res. 2003;283:1–16. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(02)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zong WX, Thompson CB. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1–15. doi: 10.1101/gad.1376506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nguewa PA, Fuertes MA, Valladares B, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids: a way to maximize their biological fitness? Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:375–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bruchhaus I, Roeder T, Rennenberg A, Heussler VT. Protozoan parasites: programmed cell death as a mechanism of parasitism. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:376–383. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ameisen JC, et al. Apoptosis in a unicellular eukaryote (Trypanosoma cruzi): implications for the evolutionary origin and role of programmed cell death in the control of cell proliferation, differentiation and survival. Cell Death Differ. 1995;2:285–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Piacenza L, Peluffo G, Radi R. L-arginine-dependent suppression of apoptosis in Trypanosoma cruzi: contribution of the nitric oxide and polyamine pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:7301–7306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121520398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Debrabant A, Lee N, Bertholet S, Duncan R, Nakhasi HL. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids and other unicellular organisms. Int. J. Parasitol. 2003;33:257–267. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(03)00008-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ouaissi A. Apoptosis-like death in trypanosomatids: search for putative pathways and genes involved. Kinetoplastid Biol. Dis. 2003;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jimenez V, Paredes R, Sosa MA, Galanti N. Natural programmed cell death in T. cruzi epimastigotes maintained in axenic cultures. J. Cell Biochem. 2008;105:688–698. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Benitez D, et al. Study of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote cell death by NMR-visible mobile lipid analysis. Parasitology. 2012;139:506–515. doi: 10.1017/S0031182011002150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dos Anjos DO, et al. Effects of a novel β-lapachone derivative on Trypanosoma cruzi: Parasite death involving apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2016;6:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Das M, Mukherjee SB, Shaha C. Hydrogen peroxide induces apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:2461–2469. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.13.2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Duszenko M, Figarella K, Macleod ET, Welburn SC. Death of a trypanosome: a selfish altruism. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:536–542. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Proto WR, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. Cell death in parasitic protozoa: regulated or incidental? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;11:58–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Welburn SC, Murphy NB. Prohibitin and RACK homologues are up-regulated in trypanosomes induced to undergo apoptosis and in naturally occurring terminally differentiated forms. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:615–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosenkranz V, Wink M. Alkaloids induce programmed cell death in bloodstream forms of trypanosomes (Trypanosoma b. brucei) Molecules. 2008;13:2462–2473. doi: 10.3390/molecules13102462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gannavaram S, Vedvyas C, Debrabant A. Conservation of the pro-apoptotic nuclease activity of endonuclease G in unicellular trypanosomatid parasites. J. Cell Sci. 2007;121:99–109. doi: 10.1242/jcs.014050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee N, et al. Programmed cell death in the unicellular protozoan parasite Leishmania. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:53–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sen N, et al. Camptothecin induced mitochondrial dysfunction leading to programmed cell death in unicellular hemoflagellate Leishmania donovani. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:924–936. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.González IJ, Desponds C, Schaff C, Mottram JC, Fasel N. Leishmania major metacaspase can replace yeast metacaspase in programmed cell death and has arginine-specific cysteine peptidase activity. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006;37:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meslin B, Zalila H, Fasel N, Picot S, Bienvenu AL. Are protozoan metacaspases potential parasite killers? Parasit. Vectors. 2011;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kosec G, et al. Metacaspases of Trypanosoma cruzi: possible candidates for programmed cell death mediators. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2005;145:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Helms MJ, et al. Bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei depend upon multiple metacaspases associated with RAB11-positive endosomes. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:1105–1117. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.González IJ. Metacaspases and their role in the life cycle of human protozoan parasites. Biomedica. 2009;29:485–493. doi: 10.7705/biomedica.v29i3.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mukherjee SB, Das M, Sudhandiran G, Shaha C. Increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels through the activation of non-selective cation channels induced by oxidative stress causes mitochondrial depolarization leading to apoptosis-like death in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:24717–24727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201961200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zangger H, Mottram JC, Fasel N. Cell death in Leishmania induced by stress and differentiation: programmed cell death or necrosis? Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:1126–1139. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.BoseDasgupta S, et al. The caspase-independent algorithm of programmed cell death in Leishmania induced by baicalein: the role of LdEndoG, LdFEN-1 and LdTatD as a DNA ‘degradesome’. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1629–1640. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alvarez VE, Niemirowicz GT, Cazzulo JJ. The peptidases of Trypanosoma cruzi: digestive enzymes, virulence factors, and mediators of autophagy and programmed cell death. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1824:195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Pitaluga AN, Moreira ME, Traub-Csekö YM. A putative role for inosine 5’ monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) Leishmania Amazon. Program. Cell death. Exp. Parasitol. 2014;149:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Piacenza L, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide radicals mediate programmed cell death in Trypanosoma cruzi: cytoprotective action of mitochondrial iron superoxide dismutase overexpression. Biochem. J. 2007;403:323–334. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ridgley EL, Xiong ZH, Ruben L. Reactive oxygen species activate a Ca2+-dependent cell death pathway in the unicellular organism Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Biochem. J. 1999;340:33–40. doi: 10.1042/bj3400033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Figarella K, et al. Prostaglandin-induced programmed cell death in Trypanosoma brucei involves oxidative stress. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1802–1814. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Le Bras M, Clément MV, Pervaiz S, Brenner C. Reactive oxygen species and the mitochondrial signaling pathway of cell death. Histol. Histopathol. 2005;20:205–219. doi: 10.14670/HH-20.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alzate JF, Arias AA, Moreno-Mateos D, Alvarez-Barrientos A, Jiménez-Ruiz A. Mitochondrial superoxide mediates heat-induced apoptotic-like death in Leishmania infantum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;152:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Vickerman K, Tetley L. Recent ultrastructural studies on trypanosomes. Ann. Soc. Belg. Med. Trop. 1977;57:441–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bera A, Singh S, Nagaraj R, Vaidya T. Induction of autophagic cell death in Leishmania donovani by antimicrobial peptides. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2003;127:23–35. doi: 10.1016/S0166-6851(02)00300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Delgado M, Anderson P, Garcia-Salcedo JA, Caro M, Gonzalez-Rey E. Neuropeptides kill African trypanosomes by targeting intracellular compartments and inducing autophagic-like cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2008;16:406–416. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Menna-Barreto RF, et al. Different cell death pathways induced by drugs in Trypanosoma cruzi: an ultrastructural study. Micron. 2008;40:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.micron.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Menna-Barreto RF, et al. Naphthoimidazoles promote different death phenotypes in Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasitology. 2009;136:499–510. doi: 10.1017/S0031182009005745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Koh HX, Aye HM, Tan KS, He CY. The lysosomotropic drug LeuLeu-OMe induces lysosome disruption and autophagy-independent cell death. Microb. Cell. 2015;2:288–298. doi: 10.15698/mic2015.08.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Herman M, Gillies S, Michels PA, Rigden DJ. Autophagy and related processes in trypanosomatids: insights from genomic and bioinformatic analyses. Autophagy. 2006;2:107–118. doi: 10.4161/auto.2.2.2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Rigden DJ, Herman M, Gillies S, Michels PA. Implications of a genomic search for autophagy-related genes in trypanosomatids. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005;33:972–974. doi: 10.1042/BST0330972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Koopmann R, Muhammad K, Perbandt M, Betzel C, Duszenko M. Trypanosoma brucei ATG8: structural insights into autophagic-like mechanisms in protozoa. Autophagy. 2009;5:1085–1091. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.8.9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Williams RA, Woods KL, Juliano L, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. Characterization of unusual families of ATG8-like proteins and ATG12 in the protozoan parasite Leishmania major. Autophagy. 2009;5:159–172. doi: 10.4161/auto.5.2.7328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kiel JA. Autophagy in unicellular eukaryotes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2010;365:819–830. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barquilla A, Crespo JL, Navarro M. Rapamycin inhibits trypanosome cell growth by preventing TOR complex 2 formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:14579–14584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802668105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Denninger V, et al. Kinetoplastida: model organisms for simple autophagic pathways? Methods Enzymol. 2008;451:373–408. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schoijet AC, Sternlieb T, Alonso GD. The Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase Class III Complex Containing TcVps15 and TcVps34 Participates in Autophagy in Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2016;64:308–321. doi: 10.1111/jeu.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Brunoro GVF, Caminha MA, Menna-Barreto RFS. Protozoan Parasitism: From Omics to Prevention and Control Ch. 1. Poole: Caister Academic Press; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Besteiro S, Williams RA, Morrison LS, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. Endosome sorting and autophagy are essential for differentiation and virulence of Leishmania major. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11384–11396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Williams RA, Smith TK, Cull B, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. ATG5 is essential for ATG8-dependent autophagy and mitochondrial homeostasis in Leishmania major. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002695. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Vanrell MC, et al. The regulation of autophagy differentially affects Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclogenesis. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017;11:e0006049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Herman M, Pérez-Morga D, Schtickzelle N, Michels PA. Turnover of glycosomes during life-cycle differentiation of Trypanosoma brucei. Autophagy. 2008;4:294–308. doi: 10.4161/auto.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Brennand A, et al. ATG24 Represses Autophagy and Differentiation and Is Essential for Homeostasy of the Flagellar Pocket in Trypanosoma brucei. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0130365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Li FJ, He CY. Acidocalcisome is required for autophagy in Trypanosoma brucei. Autophagy. 2014;10:1978–1988. doi: 10.4161/auto.36183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Li FJ, He CY. Autophagy in protozoan parasites: Trypanosoma brucei as a model. Future Microbiol. 2017;12:1337–1340. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2017-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Williams RA, Tetley L, Mottram JC, Coombs GH. Cysteine peptidases CPA and CPB are vital for autophagy and differentiation in Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:655–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Besteiro S, Coombs GH, Mottram JC. The SNARE protein family of Leishmania major. BMC Genom. 2006;7:250. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Mäser P, et al. Antiparasitic agents: new drugs on the horizon. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012;12:562–566. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Patterson S, Wyllie S. Nitro drugs for the treatment of trypanosomatid diseases: past, present, and future prospects. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.de Carvalho LP, de Melo EJT. Life and death of Trypanosoma cruzi in presence of metals. Biometals. 2017;30:955–974. doi: 10.1007/s10534-017-0064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Sousa PL, et al. Betulinic acid induces cell death by necrosis. Trypanos. cruzi. Acta Trop. 2017;174:72–75. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:132–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Evans-Osses I, de Messias-Reason I, Ramirez MI. The emerging role of complement lectin pathway in trypanosomatids: molecular bases in activation, genetic deficiencies, susceptibility to infection, and complement system-based therapeutics. Sci. Wrld. J. 2013;2013:675898. doi: 10.1155/2013/675898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Rudenko G. African trypanosomes: the genome and adaptations for immune evasion. Essays Biochem. 2011;51:47–62. doi: 10.1042/bse0510047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Bustos PL, Volta BJ, Perrone AE, Milduberger N, Bua J. A homolog of cyclophilin D is expressed. Cell Death Discov. 2017;3:16092. doi: 10.1038/cddiscovery.2016.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Ameisen JC. The origin of programmed cell death. Science. 1996;272:1278–1279. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Laverrière M, Cazzulo JJ, Alvarez VE. Antagonic activities of Trypanosoma cruzi metacaspases affect the balance between cell proliferation, death and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1358–1369. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Vaux DL, Haecker G, Strasser A. An evolutionary perspective on apoptosis. Cell. 1994;76:777–779. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kaczanowski S, Sajid M, Reece SE. Evolution of apoptosis-like programmed cell death in unicellular protozoan parasites. Parasit. Vectors. 2011;4:44. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-4-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Welburn SC, Barcinski MA, Williams GT. Programmed cell death in trypanosomatids. Parasitol. Today. 1997;13:22–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-4758(96)10076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:505–510. doi: 10.1038/nrm1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Jesenberger V, Jentsch S. Deadly encounter: ubiquitin meets apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002;3:112–121. doi: 10.1038/nrm731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Desoti VC, et al. Trypanocidal action of (-)-elatol involves an oxidative stress triggered by mitochondria dysfunction. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:1631–1646. doi: 10.3390/md10081631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Scariot DB, et al. Induction of Early autophagic process on Leishmania amazonensis by synergistic effect of miltefosine and innovative semi-synthetic thiosemicarbazone. Front. Microbiol. 2017;8:255. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]