Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is one of the most important laboratory tests for the evaluation of liver damage. Through a long-term clinical observation of patients with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, we found that most patients had abnormal GGT serum levels.

AIM

To investigate the combination of serum GGT and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in predicting the diagnosis of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis.

METHODS

In this retrospective cohort study, the clinical data of 829 patients with cholecystolithiasis admitted to the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College from August 2014 to August 2017 were collected. Among these patients, 151 patients had secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis and served as the observation group, and the remaining 678 cholecystolithiasis patients served as the control group. Serum liver function indexes were detected in both groups, and the receiver operating characteristic (commonly known as ROC) curves were constructed for markers showing statistical significances. The cutoff value, sensitivity, and specificity of each marker were calculated according to the ROC curves.

RESULTS

The overall incidence of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis was 18.2%. The results of liver function indexes including serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, direct bilirubin and total bilirubin levels showed no significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, the serum GGT and ALP levels were significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05). The ROC curve analysis showed that the area under the curve was 0.881 (95%CI: 0.830-0.932), 0.647 (95%CI: 0.583-0.711) and 0.923 (95%CI: 0.892-0.953) for GGT, ALP, and GGT + ALP, respectively. The corresponding cut-off values of GGT and ALP were 95.5 U/L and 151.5 U/L, sensitivity were 90.8% and 65.1%, and specificity were 83.6% and 59.8%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of GGT + ALP were 93.5% and 85.1%, respectively.

CONCLUSION

An abnormally elevated serum GGT level has an important value in the diagnosis of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis. The combination of serum GGT and ALP has better diagnostic performance. As a convenient, rapid and inexpensive test, it should be applied in secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis routine screening.

Keywords: Asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, Gamma-glutamyltransferase, Cholecystolithiasis, Alkaline phosphatase, Diagnosis, Screening

Core tip: Secondary choledocholithiasis is a common disease in hepatobiliary surgery, and most cases do not have symptoms. Failure of timely diagnosis of choledocholithiasis leads to an increased incidence of postoperative residual stones and related complications. In this study, a total of 829 cholelithiasis patients were included, and the results suggest that an abnormally elevated serum gamma-glutamyltransferase level has an important value in the diagnosis of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis. As a convenient, rapid and inexpensive test, serum gamma-glutamyltransferase levels should be tested in secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis routine screening.

INTRODUCTION

Cholelithiasis is a commonly seen disease in hepatobiliary surgery departments in China, especially cholecystolithiasis. With improvements in laparoscopic instruments and techniques over the past 30 years, laparoscopy has become the optimal choice of treatment for extrahepatic cholecystolithiasis[1,2]. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has almost completely replaced traditional open cholecystectomy as the best surgical treatment for gallstones. In cholecystolithiasis patients treated with surgery, the incidence of secondary choledocholithiasis is up to 10%-15%[3,4]. The surgical approaches used for cholecystolithiasis with secondary choledocholithiasis include laparotomy, laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). With the advent of minimally invasive surgery and accelerated rehabilitation surgery, minimally invasive surgery procedures such as endoscopic procedures have become the main methods for treating extrahepatic biliary calculi[5,6]. However, these two minimally invasive procedures have advantages and disadvantages, and neither are currently the gold standard.

Stones can cause obstruction in the common bile duct. The patient can have abdominal pain, fever, jaundice and other manifestations, and choledochal dilatation can be seen by abdominal B-ultrasound in symptomatic choledocholithiasis, which is easily diagnosed. In contrast, most cases of secondary choledocholithiasis do not have symptoms[7] and are often missed in diagnosis. On one hand, this may lead to the persistent presence of common bile duct stones and related complications. On the other hand, it may lead to an increased incidence of postoperative residual stones and related life-threatening complications, exacerbating the pain and economic burden for patients after LC. Therefore, an important issue has become how to easily and efficiently identify secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis in patients with common cholecystolithiasis. Gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is one of the most commonly requested laboratory tests and is a key test used for the laboratory evaluation of liver damage. Serum GGT is mainly derived from the liver and is produced by hepatocyte mitochondria, excreted by the biliary tract, and primarily distributed in the liver cytoplasm and intrahepatic bile duct epithelium[8]. Through a long-term clinical observation of patients with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, we found that most patients had abnormal serum GGT levels. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of patients with gallstone surgery in our hospital over the past three years and explored the diagnostic value of abnormal serum GGT levels for secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

General data

We collected the clinical data of 829 cases of surgically treated cholecystolithiasis in our hospital from August 2014 to August 2017. A retrospective cohort study was conducted in an observation group (patients with cholecystolithiasis complicated with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis) and a control group (patients with cholecystolithiasis alone). There were 151 patients aged 50.29 ± 10.07 years in the observation group, and 678 patients aged 48.57 ± 10.02 years in the control group. Both patient group were diagnosed with cholecystolithiasis by B-mode ultrasonography before operation, which was subsequently confirmed by surgery. Some patients in the observation group underwent preoperative magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) examination, which indicated choledocholithiasis, and all patients were diagnosed with choledocholithiasis during surgery. There were no significant differences in age, sex, comorbidity, choledochal diameter and number of stones between the two groups (P > 0.05), and the data were comparable (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline data of patients

| Characteristic | Observation group, n = 151 | Control group, n = 678 | χ 2 / t-value | P-value |

| Age, yr | 50.29 ± 10.07 | 48.57 ± 10.02 | 0.516 | 0.609 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 72 | 310 | 0.191 | 0.662 |

| Female | 79 | 368 | ||

| BMI | 20.76 ± 4.51 | 20.03 ± 4.27 | 1.701 | 0.248 |

| Complications | ||||

| Hypertensive disease | 20 | 68 | 1.346 | 0.246 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 | 119 | 0.739 | 0.390 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 16 | 60 | 0.452 | 0.501 |

BMI: Body mass index.

Criteria for case selection

Inclusion criteria: adult patients; clear diagnosis by surgery; no acute suppurative cholecystitis and cholangitis; and no manifestation of obstructive jaundice. Exclusion criteria: complicated with liver or biliary malignancies, acute or chronic hepatitis, primary choledocholithiasis or intrahepatic cholangiolithiasis; presence of Mirrizi syndrome; complicated with alcohol intoxication drug induced liver disease; and complicated with ischemic heart diseases.

Evaluation indexes

The following serum liver function indexes were detected in the two groups: aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, GGT, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin and direct bilirubin. The indexes with significant differences were further analyzed by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of each abnormal index in the diagnosis of secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis.

Statistical analysis

Data are described as the mean ± SD, and SPSS 22.0 was used for statistical analyses. To compare baseline data between the two groups, independent sample t-tests and χ2 tests were employed. Independent sample t-tests were used to compare serum liver function indicators between the two groups. The ROC curve was established to evaluate the diagnostic value of GGT and ALP; the cutoff value of the indicators was calculated using Youden index (specificity + sensitivity - 1). The comparison of the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was analyzed by Z-test. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Incidence of secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis

A total of 829 patients with cholecystolithiasis were included, 151 of them were complicated with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, and the overall incidence was 18.2%.

Liver function indexes

Serum GGT and ALP levels were significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences in serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, direct bilirubin and total bilirubin levels between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of serum liver function indexes

| Variable | Observation group, n = 151 | Control group, n = 678 | t-value | P-value |

| ALT, U/L | 35.04 ± 9.18 | 33.22 ± 9.71 | 0.354 | 0.803 |

| AST, U/L | 38.96 ± 10.65 | 36.52 ± 10.33 | 0.289 | 0.834 |

| TBIL, μmol/L | 11.58 ± 2.87 | 9.99 ± 1.93 | 0.417 | 0.682 |

| DBIL, μmol/L | 5.56 ± 0.77 | 4.95 ± 0.64 | 0.392 | 0.786 |

| GGT, U/L | 154.56 ± 39.53 | 35.98 ± 8.19 | 35.721 | 0.000 |

| ALP, U/L | 171.51 ± 41.74 | 139.49 ± 36.64 | 7.317 | 0.000 |

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; TBIL: Total bilirubin; DBIL: Direct bilirubin; GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

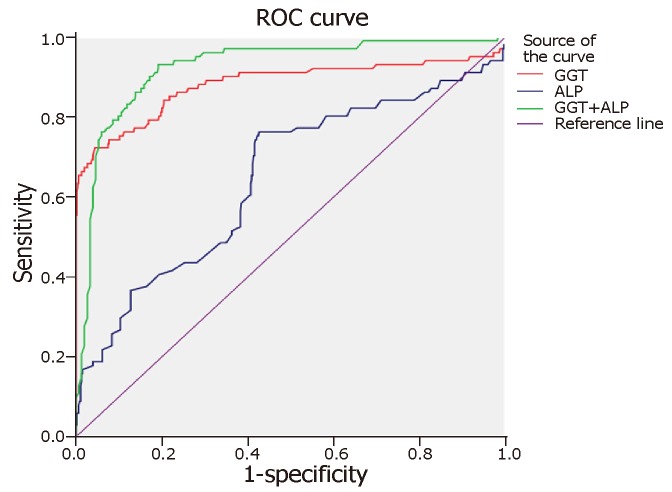

ROC curves

The AUCs were 0.881 (95%CI: 0.830-0.932), 0.647 (95%CI: 0.583-0.711) and 0.923 (95%CI: 0.892-0.953) for GGT, ALP, and GGT + ALP, respectively. The correspondent cut-off values of GGT and ALP were 95.5 U/L and 151.5 U/L, sensitivities were 90.8% and 65.1%, and specificities were 83.6% and 59.8%, respectively. The sensitivity and specificity of GGT + ALP were 93.5% and 85.1%, respectively (Table 3 and Figure 1).

Table 3.

Analysis of receiver operating characteristic curve

| Variable | Area | Std. Error | Asymptotic Sig | Asymptotic 95%CI | Cutoff value, U/L | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| GGT | 0.881 | 0.026 | 0 | 0.830-0.932 | 95.5 | 0.908 | 0.836 |

| ALP | 0.647 | 0.033 | 0 | 0.583-0.711 | 151.5 | 0.651 | 0.598 |

| GGT + ALP | 0.923 | 0.016 | 0 | 0.892-0.953 | - | 0.935 | 0.851 |

GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

Figure 1.

ROC curve of GGT and ALP. ROC: Receiver operating characteristic GGT: Gamma-glutamyltransferase; ALP: Alkaline phosphatase.

DISCUSSION

Cholelithiasis is a common and frequently occurring disease worldwide. In the United States, the incidence of cholelithiasis is as high as 15%–20%[9]. In China, the overall incidence of the disease is 10%, and the incidence is higher in the western region; however, recent studies have found that the incidence has been significantly increasing. According to the latest literature, cholelithiasis is occurring in younger patients year by year, with a significant increase in adolescents (< 20 years old), which may be related to obesity, lack of exercise, diabetes and early pregnancy[10]. Choledocholithiasis can be divided into primary and secondary disease. Most cases are secondary choledocholithiasis[11], in which small gallstones descend to the common bile duct through the cystic duct. If they cannot be extruded from the common bile duct into the duodenum, they form common bile duct stones, also known as choledocholithiasis. Since the stones are small and float in the common bile duct, most patients are asymptomatic for a period of time, which is called static or asymptomatic choledocholithiasis. Our results showed that the overall incidence of secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis was as high as 18.2%. Patients diagnosed and treated in our hospital mainly came from Southwest China, and the overall incidence of cholelithiasis in this area is high. In the process of autonomic stone drainage of choledocholithiasis, it is likely to cause serious complications such as stone incarceration, acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis and acute pancreatitis. On one hand, some cholecystolithiasis patients are unwilling to undergo early surgical treatment and opt for outpatient follow-up. If they are not screened for asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, stones may exist in the common bile duct for a long time without symptoms, which can lead to long-term chronic bile duct inflammation and even cholangiocarcinoma. On the other hand, if asymptomatic choledocholithiasis is not found before surgery in patients with gallstones, LC alone may result in complications such as jaundice, acute cholangitis and acute pancreatitis. Therefore, it is important to perform routine secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis screening on cholecystolithiasis patients to improve the vigilance of clinicians and to avoid these harmful complications.

The examination methods of choledocholithiasis include abdominal B-ultrasound, computed tomography (commonly known as CT), MRCP, ERCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)[12-14]. Abdominal B-ultrasound can accurately diagnose cholecystolithiasis and is the first choice for the examination of cholecystolithiasis. However, the location of the common bile duct is deep, and due to disturbance by abdominal wall fat and gastrointestinal gas, there is no expansion or no apparent expansion of the upper common bile duct, or there is stenosis and curvature of the common bile duct. Therefore, it is often difficult to detect common bile duct stones with external B-ultrasound, and its diagnostic accuracy for sediment-like stones is only 55%[15]. CT examination has a high diagnostic rate for high-density calculi with a large diameter, but the diagnostic accuracy for low-density or small stones is low[16]. MRCP is more sensitive for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones, but the feasibility in patients with pathological obesity or with foreign metal materials in the body (such as a cardiac pacemaker) is low. It is also expensive and increases the economic burden on patients and may lead to waste of medical resources, so it is not appropriate as a routine preoperative screening method. ERCP can identify the location and size of common bile duct stones, and thus is still the gold standard for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis[15]. However, this method is invasive, difficult to operate and causes many complications, so it cannot be used as an optimal routine screening method. EUS can avoid the interference of abdominal wall fat and gastrointestinal gas and obtain clear bile duct ultrasound imaging, making it a useful tool for diagnosing common bile duct stones[17]. However, EUS is not yet performed in most primary hospitals. The procedure also has difficulties during operation. For example, due to stenosis of the stomach outlet and duodenum, the endoscope cannot successfully reach the duodenal bulb, and patients experience a lot of pain, so EUS is not yet considered to be a better routine screening method. Therefore, it is of great clinical significance to find a small-trauma, convenient, fast, reliable and inexpensive examination method for asymptomatic choledocholithiasis screening. According to the literature, factors such as serum bilirubin, ALP and GGT have some predictive effects on the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis[18-20]. However, these studies were limited to symptomatic choledocholithiasis, and there have been few studies on secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis.

The results of the present study showed that serum GGT and ALP levels in patients in the observation group were significantly higher than in the control group. This indicates that changes in these two indicators are related to asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, and an abnormal increase of these indicators may be a risk factor for cholecystolithiasis with common bile duct stones. ROC curve analysis showed that the AUC, sensitivity and specificity of serum GGT were high. It also indicated that an abnormal increase in serum GGT plays an important role in predicting cholecystolithiasis combined with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, and it may be an effective serological index for routine screening. With the exception of obvious jaundice, a raised GGT level has been suggested to be the most sensitive and specific indicator of CBD stones[21]. There are two reasons for increased GGT. First, the presence of stones may cause local inflammatory damage to the bile duct epithelium, resulting in excessive GGT production. Therefore, even the latest literature suggests that serum GGT is also an inflammatory marker[21]. Second, the presence of stones has a mechanical stimulatory effect on the bile duct epithelium, inducing the epithelial layer to increase GGT synthesis, combined with poor bile excretion, eventually leading to an abnormal increase in serum GGT. Therefore, if the GGT exceeds the cut-off level in serum liver function in gallstone patients, we should be vigilant that the patient is most likely afflicted with secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, and MRCP or ERCP examination should be performed to confirm the diagnosis. This can avoid biliary tract inflammatory disease or tissue malignant transformation caused by the long-term presence of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis. A suitable surgical plan can also be developed to prevent intraoperative accidents, serious postoperative complications and other risks due to missed diagnosis. The AUC of serum ALP was 0.647 (< 0.7), and the corresponding sensitivity and specificity were low, suggesting that serum ALP levels may be affected by acute cholangitis in obstructive jaundice, but it is of little practical clinical value. The combination of serum GGT and ALP (AUC 0.923; sensitivity 93.5%; specificity 85.1%) had better diagnostic performance for secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis.

In summary, abnormally elevated serum GGT level may be a potentially useful marker for the early prediction of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis. Additionally, the combination of serum GGT and ALP had better diagnostic performance. When the serum GGT level reaches the cutoff value, physicians should be vigilant about the possibility of secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis, and timely and proper interventions should be performed to avoid aggravation of the disease. As a convenient, rapid and inexpensive test, it is worth applying this test in secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis routine screening.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Cholelithiasis is a commonly seen disease in hepatobiliary surgery departments in China. In cholecystolithiasis patients treated by surgery, the incidence of secondary choledocholithiasis is up to 10%-15%. However, most cases of secondary choledocholithiasis often have no symptoms and are missed in diagnosis.

Research motivation

It is of great clinical significance to explore the methods for the early diagnosis of asymptomatic secondary choledocholithiasis to develop rational surgical protocols, avoid postoperative residual stones and reduce related complications.

Research objectives

To investigate the diagnostic value of abnormal serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) levels in asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis.

Research methods

In this retrospective cohort study, the clinical data of 829 cholelithiasis patients were collected. Serum liver function indexes were detected in both groups, and the ROC curves were constructed for markers showing statistical significances.

Research results

The overall incidence of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis was 18.2%. The results of liver function indexes, including serum aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, direct bilirubin and total bilirubin levels showed no significant differences between the two groups. However, serum GGT and alkaline phosphatase levels were significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group.

Research conclusions

In the diagnosis of asymptomatic choledocholithiasis secondary to cholecystolithiasis, abnormally elevated serum GGT levels have important value; and the combination of serum GGT and alkaline phosphatase had better diagnostic performance.

Research perspectives

Physicians should be vigilant about the possibility of secondary asymptomatic choledocholithiasis when the serum GGT level reaches the cutoff value. Timely and proper interventions should be performed to avoid aggravation of the disease.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, No. ZSYYLL118.

Informed consent statement: All clinical data were collected with informed consent obtained from study participants.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare that they have no any conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 4, 2018

First decision: October 18, 2018

Article in press: December 21, 2018

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: El-Bendary M, Gencdal G S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Yong Mei, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Li Chen, Diagnostics Laboratory, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Peng-Fei Zeng, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Ci-Jun Peng, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Jun Wang, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Chao Du, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Kun Xiong, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Kai Leng, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Chun-Lin Feng, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

Ji-Hu Jia, Department of Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical University, Zunyi 563000, Guizhou Province, China.

References

- 1.Bourgouin S, Mancini J, Monchal T, Calvary R, Bordes J, Balandraud P. How to predict difficult laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Proposal for a simple preoperative scoring system. Am J Surg. 2016;212:873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng Y, Jiang ZS, Xu XP, Zhang Z, Xu TC, Zhou CJ, Qin JS, He GL, Gao Y, Pan MX. Laparoendoscopic single-site cholecystectomy vs three-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a large-scale retrospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4209–4213. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i26.4209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dasari BV, Tan CJ, Gurusamy KS, Martin DJ, Kirk G, McKie L, Diamond T, Taylor MA. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013:CD003327. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003327.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thapa PB, Maharjan DK, Suwal B, Byanjankar B, Singh DR. Serum gamma glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase in acute cholecystitis. J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2010;8:78–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwab B, Teitelbaum EN, Barsuk JH, Soper NJ, Hungness ES. Single-stage laparoscopic management of choledocholithiasis: An analysis after implementation of a mastery learning resident curriculum. Surgery. 2018;163:503–508. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Temimi MH, Kim EG, Chandrasekaran B, Franz V, Trujillo CN, Mousa A, Tessier DJ, Johna SD, Santos DA. Laparoscopic common bile duct exploration versus endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography for choledocholithiasis found at time of laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Analysis of a large integrated health care system database. Am J Surg. 2017;214:1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Noda Y, Goshima S, Kojima T, Kawaguchi S, Kawada H, Kawai N, Koyasu H, Matsuo M, Bae KT. Improved diagnosis of common bile duct stone with single-shot balanced turbo field-echo sequence in MRCP. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:1183–1188. doi: 10.1007/s00261-016-0990-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall P, Cash J. What is the real function of the liver 'function' tests? Ulster Med J. 2012;81:30–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaffer EA. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology of gallbladder stone disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:981–996. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chilimuri S, Gaduputi V, Tariq H, Nayudu S, Vakde T, Glandt M, Patel H. Symptomatic Gallstones in the Young: Changing Trends of the Gallstone Disease-Related Hospitalization in the State of New York: 1996 - 2010. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9:117–123. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2847w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yousefpour Azary S, Kalbasi H, Setayesh A, Mousavi M, Hashemi A, Khodadoostan M, Zali MR, Mohammad Alizadeh AH. Predictive value and main determinants of abnormal features of intraoperative cholangiography during cholecystectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2011;10:308–312. doi: 10.1016/s1499-3872(11)60051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CC. The efficacy of endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of common bile duct stones as compared to CT, MRCP, and ERCP. J Chin Med Assoc. 2012;75:301–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2012.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giljaca V, Gurusamy KS, Takwoingi Y, Higgie D, Poropat G, Štimac D, Davidson BR. Endoscopic ultrasound versus magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for common bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015:CD011549. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward WH, Fluke LM, Hoagland BD, Zarow GJ, Held JM, Ricca RL. The Role of Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography in the Diagnosis of Choledocholithiasis: Do Benefits Outweigh the Costs? Am Surg. 2015;81:720–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Canlas KR, Branch MS. Role of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6314–6320. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim CW, Chang JH, Lim YS, Kim TH, Lee IS, Han SW. Common bile duct stones on multidetector computed tomography: attenuation patterns and detectability. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1788–1796. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i11.1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aljebreen AM. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in common bile duct stones. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:11–16. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.30459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zare M, Kargar S, Akhondi M, Mirshamsi MH. Role of liver function enzymes in diagnosis of choledocholithiasis in biliary colic patients. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49:663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agahi A, McNair A. Choledocholithiasis presenting with very high transaminase level. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012007268. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cakar M, Balta S, Demirkol S, Altun B, Demirbas S. Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) should be evaluated together with other inflammatory markers in clinical practice. Angiology. 2013;64:401. doi: 10.1177/0003319712469876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jovanović P, Salkić NN, Zerem E, Ljuca F. Biochemical and ultrasound parameters may help predict the need for therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with a firm clinical and biochemical suspicion for choledocholithiasis. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22:e110–e114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]