Abstract

BACKGROUND

Sarcopenia, i.e., muscle loss is now a well-recognized complication of cirrhosis and in cases of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease can contribute to accelerate liver fibrosis leading to cirrhosis. Hence, it is imperative to study interventions which targets to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

AIM

To examine the relationship between interventions such nutritional supplementation, exercise, combined life style intervention, testosterone replacement and trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to improve muscle mass in cirrhosis.

METHODS

We search PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane between June-August 2018, without a limiting period and the types of articles (RCTs, clinical trial, comparative study) in adult patients with sarcopenia and cirrhosis. The primary outcome of interest was improvement in muscle mass, strength and physical function interventions mentioned above. In the screening process, 154 full text articles were included in the review and 129 studies were excluded.

RESULTS

We identified 24 studies that met review inclusion criteria. The studies were diverse in terms of the design, setting, interventions, and outcome measurements. We performed only qualitative synthesis of evidence due to heterogeneity amongst studies. Risk of bias was medium in most of the included studies and low quality of evidence showed improvement in the muscle mass, strength and physical function following aerobic exercise. 60% of the included studies on the nutritional intervention, 100% of the studies on testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men and trans-jugular portosystemic shunt were proved to be effective in improving sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

CONCLUSION

Although the quality of evidence is low, the findings of our systematic review suggest improvement in the sarcopenia in cirrhosis with exercise, nutritional interventions, hormonal and TIPS interventions. High quality randomized controlled trials needed to further strengthen these findings.

Keywords: Sarcopenia, Cirrhosis, Treatment, Intervention, Nutrition, Therapy, Exercise, Testosterone, Trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

Core tip: Sarcopenia is now a well-recognized complication of cirrhosis and in cases of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease can contribute to accelerate liver fibrosis leading to cirrhosis. Hence, it is imperative to study interventions which targets to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis. Aim of this systematic review of the literature was to examine the relationship between interventions such nutritional supplementation, exercise, combined life style intervention, testosterone replacement and trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to improve muscle mass in cirrhosis. We suggest improvement in the sarcopenia in cirrhosis with exercise, nutritional interventions, hormonal and trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Sarcopenia, a term first coined by Irwin Rosenberg, drives its origin from the Greek phrase sarx meaning “flesh/muscle” and penia meaning “loss”[1]. Although a standard definition is lacking, sarcopenia is defined as the degenerative loss of skeletal muscle mass that is involuntary and age related[2]. Sarcopenia resulting from advance age is referred to as primary sarcopenia. This can begin as early as the 4th decade of life and progresses in a linear fashion resulting in up to 50% loss of skeletal muscle mass by the 8th decade of life. Sarcopenia caused by chronic conditions such as liver cirrhosis or malignancy is referred to as secondary sarcopenia[3]. Cirrhosis is a result of chronic liver injury cumulating in irreversible hepatocellular dysfunction, cell death, vascular remodeling and fibrosis. Although liver transplantation can cure this condition, it is not always a viable option for the majority of patients[4]. As such, efforts are focused on preventing and controlling complications of the disease. Sarcopenia in cirrhosis is a cause of increase morbidity and mortality with recent studies demonstrating sarcopenia as an independent predictor of poor survival in cirrhotic patients with or without hepatocellular cancer[5,6]. In the USA sarcopenia secondary to cirrhosis affects over 300000 people and is associated with increased cost of treatment, length of stay in hospital and, pre and post-transplant mortality[7-16].

The stigmata of cirrhosis is widely understood and includes hepatocellular carcinoma (3%-5%), ascites (5%-10%), variceal bleeding (10%-15%), and hepatic encephalopathy (62.4%)[5,6]. Sarcopenia, despite being a prevalent feature of the disease, is not as readily associated with cirrhosis. Malnutrition resulting in sarcopenia is one of the most frequent complications in patient with cirrhosis; adversely affecting other complications, survival, quality of life, and outcomes after liver transplantation[7-16]. Patients with cirrhosis develop protein energy malnutrition at a rate of 25.1%-65.6%[3,17-19]. The prevalence of sarcopenia also is noted to have a similar distribution (30%-70%). Patients with cirrhosis also have severe exercise intolerance which further contributes to malnutrition and ultimately sarcopenia. According to the findings of a recent systematic review, a mean peak VO2 of 17.4 mL/kg per min was reported in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. For comparison this is a value typically found in female aged 80–89 year having sedentary life style[20].

A vast disparity in prevalence of secondary sarcopenia from cirrhosis is seen due to a lack of a standard definition, varying patient baseline characteristics, and diversity in the cause and severity of liver disease among studies[21]. Currently due to lack of studies, the economic data on sarcopenia is poor[22]. The direct cost of sarcopenia in the USA was estimated to be $18.5 billion. The primary factors influencing this cost were hospitalization, nursing home admissions, and home healthcare expenditures. This value represents 1.5% of total healthcare expenditure in the USA[23]. The indirect costs of sarcopenia are not considered when calculating the $18.5 billion dollars and sarcopenia likely costs the USA far more. These costs include disability resulting from sarcopenia, increased risk of comorbidities, osteoporosis[24], obesity[25], and type II diabetes[26]. All in all, the true cost of sarcopenia is sure to be staggering. This systematic review will provide an in-depth review of current treatment modalities for combatting sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis.

Interventions such as exercise, improved nutrition, hormonal replacement in hypogonadal men and trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shuts (TIPS) have been evaluated in various randomized and non-randomized studies. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the studies that focuses on the intervention (such as exercise, nutrition or pharmacological) to improve sarcopenia in cirrhotic patients.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Protocol and registration

This systematic review was registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews platform (PROSPERO, registration number: CRD42018109320). This study followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses[27].

Eligibility

Studies that reported a relationship between interventions such as exercise, nutrition/diet, TIPS and testosterone and a measure of skeletal muscle mass and/or physical function in cirrhotic populations were deemed eligible. Studies were included in the systematic review when they met following inclusion criteria: (1) Randomized clinical trials (RCTs), quasi experimental, cohort and case control studies published in peer reviewed journal; (2) Focused on single or combined intervention such as exercise, nutrition/diet, TIPS or testosterone on adult cirrhotic patient ≥ 18 years; and (3) Outcome measure i.e., sarcopenia which was assessed by one or more physical function (anthropometry, Bioelectric impedance analysis, computed tomography (CT), ultrasound measurement of muscle thickness or assessment of physical function by using 6 mins walk test or peak VO2 measurement).

After preliminary review of title and abstract we excluded conference abstracts, case reports, series, editorials and articles that were not in English language. Studies evaluating the effect of these interventions on outcomes other than sarcopenia were also excluded.

Study search and selection

We search PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane between June-August 2018, without a limiting period and the types of articles (RCTs, clinical trial, comparative study). Following set of keywords were used for the search strategy: “Muscular Atrophy"[Mesh] OR "Sarcopenia"[Mesh] OR (“Atrophic muscular disorders” OR “Muscle atrophy” OR “Muscle degeneration” OR “Muscle fiber atrophy” OR “Muscle fiber degeneration” OR “Muscle wasting” OR “Muscular wasting” OR “Muscular atrophy” OR “Muscular atrophies” OR “Muscular degeneration” OR Myoatrophy OR Myatrophy OR Myophagism OR Myodegeneration OR Myophagism OR Sarcopenia) AND ("Liver Cirrhosis"[Mesh]) OR (Cirrhosis OR Cirrhoses OR “Liver fibrosis” OR “Liver fibroses”). Filters were used to limit the search to those in the English language. Eligible studies were selected after reading title and abstract. Full text of article was read when subject or outcomes of interest were not clear.

Data collection process and variables

Data was collected by two independent investigators for the following variables: author, type of the study, year of the study conducted, setting, characteristics of the study participants, sample size, study design, intervention, and changes in the muscle mass/ physical function following intervention. Third reviewer was involved to solve a disagreement in the findings of two reviewers and solved by discussion.

Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed by two independent reviewers using standard assessment tool recommended by Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) for non RCT studies including case control and pre-post intervention. The CRD tool has a set of ten criteria by which to evaluate risk of bias: study setting, design, population, exposure (exercise, nutrition, testosterone/TIPS), reliability of outcome measurements (sarcopenia) obtained, adjustment for confounders, blinding, losses to follow-up, information on non-participants and information on analyses. Studies with total score of -9 to -3 were classified as “high risk”. Studies with score of -2 to +3 were categorized as “medium risk”; or “low risk” of bias if the was +4 to +10[27].

For randomized controlled trial, the risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. The tool assessed studies based on randomized sequence generation, treatment allocation concealment, blinding, completeness of the outcome data, and selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias[28].

RESULTS

Search results

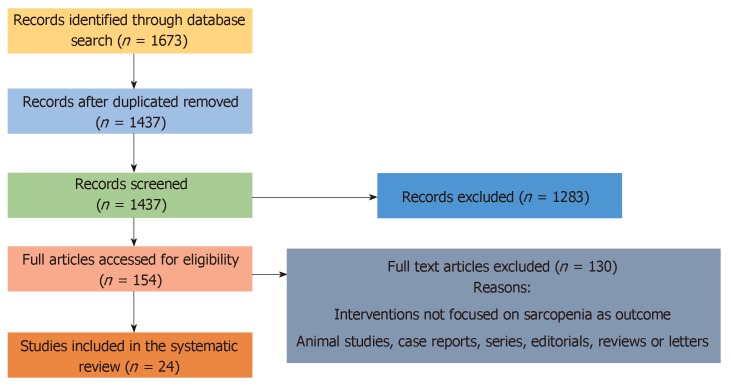

Preliminary search yielded 1673 articles. After removal of duplicate (n = 236 articles), 1437 titles and abstract were screened to determine their eligibility to be included in the systematic review. Following careful review of titles and abstract we excluded 1283 articles. Total of 154 articles were assessed fully by 2 reviewers out of which 130 abstracts were excluded as they were not meeting inclusion criteria. Finally, we found 24 full texts articles to be eligible and were included in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses diagram of interventions to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

Characteristics of the studies

Out of 24 studies included in the systematic review, 3 studies were case control[30,38,49], 8 studies were non RCT (pre-post intervention/ quasi experimental)[37,40,45-48,50,51] and 13 were randomized controlled trial[29,31-36,39,41-44,52]. All the studies were done in the hospital setting and the sample sizes ranged from 6 to 174 participants. In almost all studies, liver cirrhosis was diagnosed with documented histology, confirmed by laboratory data sonographic and endoscopic evidence of portal hypertension. 9 out of 24 studies had over 50 participants. Seven studies were done in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. In 17 studies Child-Turcotte-Pugh score ranged between 6-9. Most of the studies (n = 22) had participants whose mean age ranged between 40 and 60 years, with only two studies enrolled participants above 70 years. Male to female ratio was 1.5:1 and mean BMI of the study participants was 26. Study by Dupont et al[34] was done exclusively in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis without current evidence of alcoholic hepatitis and Nakaya et al[31] enrolled patient with cirrhosis secondary to chronic hepatitis C infection. Though most of the studies excluded patients with current symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy, ascites, variceal bleeding from esophageal varices, Maharshi et al[35] evaluated the effect of nutritional supplement in cirrhotic patient with minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

In most of the included studies sarcopenia was assessed using muscle mass, and muscle strength via skin fold thickness, hand grip muscle circumference, lean and fat muscle mass using anthropometric measurement and bioelectric impedance analysis. In four studies muscle and fat mass was measured using imaging (CT scan or ultrasound). Physical performance i.e., functional capacity used as a measure of sarcopenia is six studies.

Study findings

The synthesis of study findings is presented by intervention in the following order: nutritional intervention, exercise, combined exercise and nutrition, testosterone and TIPS (Tables 1-5)

Table 1.

Nutritional interventions to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis

| Ref. | Study participant’s characteristics | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Duration of intervention | Diagnosis of sarcopenia | Results |

| Marchesini et al[29], 2003 | mean age: 59 yr; males/females: 13/59; BMI: NA; CTP score: 9; setting: Europe | RCT | 174 | Intervention: Nutritional supplementation with BCCA (leucine, isoleucine and valine); Control: Lactalbumin or maltodextrins | 1 yr | Anthropometric and BIA | Significant increase in triceps skinfold thickness and MA fat area |

| Okumara et al[30], 2006 | Age: NA; Gender: NA; mean BMI: 21; CTP score: 6; setting: Japan | Case control | 47 | Regular diet and late evening snack (rice ball) | 1 wk | Anthropometric measurement i.e., AMA, AC and AMC | No significant differences in BMI, AC, AMC or AMA; improvement in RQ value in intervention group |

| Nakaya et al[31], 2007 | Age: 67; males/females: 20/18; mean BMI: 22.9; CTP score: 7; setting: Japan | RCT | 48 | LES with BCAA enriched mixture or ordinary food such as rice ball or bread | 3 mo | Anthropometric measurements such as MAC and triceps skin fold thickness | No significant improvement in the anthropometric parameter in either group |

| Les et al[32], 2011 | mean age: 64.1 ± 10.4; males/females: 88/28; mean BMI: NA; CTP score: 8; Setting: Barcelona | RCT | 116 | Intervention: Standard diet + 0.7 g of protein/kg + supplement of 30 g of BCAA; Control group: Standard diet + 0.7 g of protein/kg + maltodextrin | 56 wk | Anthropometric | Increased in MA circumference and hand grip in intervention group |

| Sorrentino et al[33], 2012 | mean age: 65; males/females: 81/39; mean BMI: NA; CTP score: 12; setting: Italy | RCT | 120 | Group A: parenteral nutritional support + balanced diet + LES; Group B: balanced diet + LES; Group C: low sodium or sodium free diet | 12 mo | Anthropometric measurements such as MAC and triceps skin fold thickness | No significant differences in the anthropometric measures in three groups. Significantly improved in the morbidity and mortality in group A and B |

| Dupont et al[34], 2012 | mean age: 54.6 ± 9.6; males/females: 65/43; mean BMI: 26; CTP score: 10; setting: France | RCT | 99 | Enteral nutrition vs a symptomatic support; i.e., 30–35 kcal/kg per day of a polymeric solution for a period of 3–4 wk, through a nasogastric feeding tube. for three oral nutritional supplements per day for 2 mo. | 3 mo | Anthropometric measurements such as MAC and triceps skin fold thickness | No change in arm muscle circumference |

| Maharshi et al[35], 2016 | mean age: 42; males/females: 5/25; mean BMI: NA; CTP score: 8; setting: India | RCT | 120 | Nutritional therapy (30-35 kcal/kg/d, 1.0-1.5 g vegetable protein/kg/d vs no nutritional therapy | 6 mo | Anthropometric measurements such as MAC and triceps skin fold thickness | Significant improvement in the MAC, hand grip and skeletal muscle mass |

| Ruiz-Margain et al[36], 2017 | mean age: 47.8-54.9; males/females: 13/59; mean BMI: 26; CTP score: 6; setting: Mexico | RCT | 72 | Intervention: BCAA + High protein and high fiber diet; Control: Only high protein and high fiber diet | 6 mo | Anthropometric measurement: triceps skin fold thickness and MAC | Increase in muscle and decrease in fat mass in intervention group |

| Kitajima et al[37], 2017 | mean age: 71.3 ± 7.9; males/females: 9/12; mean BMI: 23.9; CTP score: NA; setting: Japan | Longitudinal study; (pre-post intervention) | 21 | Diet supplemented with BCAA 3 x daily after meals | 48 wk | CT scan and BIA | ΔIMAC and ΔSAI significantly correlated with Δserum albumin level. BCAA supplementation prevented the progression of sarcopenia in cirrhosis |

| Ohara et al[38], 2018 | mean age: 67; males/females: 53/17; mean BMI: 24.6; CTP score: 7; setting: Japan | Matched case control; Cases: 35; Control: 35 | 70 | Cases: Received L carnitine; Control: no supplementation | 6 mo | CT images: Psoas muscle index | Significant suppression in the loss of skeletal muscle in intervention group |

MA: Mid arm fat area; BIA: Bio impedance analysis; AMA: Arm muscle area; AC: Mid upper arm circumference; AMC: Arm muscle circumference; RQ: Respiratory quotient; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 2.

Exercise interventions to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis

| Ref. | Study participants characteristics | Study design | Patients enrolled | Intervention | Duration of intervention | Diagnosis of sarcopenia | Results |

| Zenith et al[39], 2014 | mean age: 57 years; males/females: 15/4; mean BMI: 28; CTP score: 6; setting: Canada | RCT ; Intervention = 9; Control = 10 | 19 | Supervised exercise (cycle ergometer 3 d/wk). 5 min warm up on low level cycling, exercise initiated at 30 min per session and increased by 2.5 min per session until study completion | 8 wk | Quadriceps muscle thickness measured by ultrasound and thigh circumference | Peak VO2 thigh thickness and circumference increased at end of intervention |

| Debette-Gratien et al[40], 2015 | Mean Age: 51 ± 12; males/females: 6/3; mean BMI: NA; CTP score: 7; setting: France | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention) | 13 | Personalized Adapted Physical Activity | 12 wk | Functional capacity and muscle strength | Post intervention significant increase in the mean exercise VO2 peak and the mean quadriceps isometric strength |

| Roman et al[41], 2016 | mean age: 63; males/females: 17/6; mean BMI: 31; CTP score: 6; setting: Spain | RCT | 23 | Intervention: 1-h session 3 times/wk; Control: Sham intervention | 12 wk | Functional capacity by CPET, Anthropometry, DEXA and Timed up and GO study | Increase in total effort time, ventilatory anaerobic threshold time and upper thigh circumference. Decrease in MA and mid-thigh skin fold thickness. DEXA showed decrease in fat body mass and increase in lean body mass, lean appendicular mass and lean leg mass. No changes in the control group |

| Macias-Rodriguez et al[42], 2016 | mean age: 52; males/females: 19/6; mean BMI: 27.5; CTP score: 6; setting: Mexico | RCT | 25 | Intervention group: PEP (personalized exercise program) (cycloergometry/kinesiotherapy plus nutrition); control: only nutrition | 14 wk | BIA and CPET | Significant improvement in ventilatory efficiency (VE/VCO2) and phase angle |

| Kruger et al[43], 2018 | mean age: 53-56; males/females: 23/17; mean BMI: 29; CTP score: 6; setting: Canada | RCT | 40 | Home exercise training i.e., moderate to high intensity cycling exercise, 3 d/wk vs usual care | 8 wk | Measurement of peak VO2; Aerobic endurance using 6-min walk test; Ultrasound to measure thigh muscle circumference and mass | Significant increase in peak VO2, aerobic endurance, thigh circumference and insignificant improvement in thigh muscle thickness as measured by the average feather index |

CPET: Cardiopulmonary exercise testing; CSA: Cross sectional area; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 3.

Combined life style intervention (exercise and nutrition) to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis

| Ref. | Study participants characteristics | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Duration of intervention | Diagnosis of sarcopenia | Results |

| Roman et al[44], 2014 | mean age: 43-75; males/females: 12/5; mean BMI: 27; CTP score: 7; setting: Spain | RCT | 17 | Intervention: moderate exercise + oral leucine; Control: Placebo | 12 wk | Exercise capacity (6-min walk and 2-min step tests), anthropometric measurement | Significant increase in exercise capacity. Increase in lower thigh circumference. No changes in control group |

| Nishida et al[45], 2017 (medium risk) | mean age: 47.8-54.9; gender: 6 females; mean BMI: 24.3; CTP score: 6; setting: Japan | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention) | 6 | Homes based step exercise at AT (140 min/wk) and BCAA supplementation (12.45 g/d) | 12 mo | CT scan to assess fat deposition in liver and IMAC | Significantly increased AT; No changes in TBW, liver/spleen ratio or IMAC |

| Hiraoka et al[46], 2017 | median age (IQR): 66 (62-70); males/females: 13/20; child A/B: 30/3; median BMI (IQR): 23.2 (20.8-25.1); setting: Japan | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention) | 33 | BCAA supplementation as LES and additional 2000 steps/d prescribed | 6 mo | BIA Leg and Hand grip | Muscle volume, leg and handgrip strength increased after post intervention |

| Berzigotti et al[47], 2017 | mean age: 56 ± 8; gender: 31/29; mean BMI: 33; CTP score: < 8; setting: Spain | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention) | 60 included and 50 completed the study | LS interventions which include: Reduce calorie intake of 500-1000 kCal/d (protein intake 20%-25%, Carbs: 45%-50% and fat content < 35%); Supervised exercise-60 min session of moderate exercise. | 16 wk | BIA and anthropometric measurements | Decrease in TBW, fat mass; Unchanged lean mass |

AT: Anaerobic threshold; IMAC: Intramuscular adipose tissue content; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 4.

Trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis

| Ref. | Study participants characteristics | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Follow up, mean ± SD | Diagnosis of sarcopenia | Results |

| Plauth et al[48], 2004 | mean age: 60; gender: 13/8; mean BMI: 22.3; decompensated; setting: Germany | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention study) | 21 | TIPS | 12 mo | Anthropometry, BIA, REE by indirect calorimeter and TBP | Increased muscle mass; no change in REE and fat mass |

| Tsein et al[49], 2013 | mean age: 55.5; gender: 59/30; mean BMI: 29; CTP score: 9; setting: USA | Case control; Cases: 57; Controls: 32 | 57 | TIPS | 13.5 ± 11.9 mo | Unenhanced CT axial scan | Total psoas and paraspinal muscle area increased significantly after TIPS; post TIPS visceral fat volume decreased significantly |

| Montomoli et al[50], 2010 | mean age: 47.8-54.9; gender: 14/7; mean BMI: 26.2; MELD: 18; setting: Denmark | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention study) | 21 | TIPS | 52 wk | Anthropometry: body composition parameters such as dry lean mass and fat mass | Patient with normal weight has increased in dry lean mass. No changes in the fat mass |

TBP: Total body protein; REE: Resting energy expenditure; FFA: Free fatty acid; CT: Computed tomography; TIPS: Trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; BMI: Body mass index.

Table 5.

Testosterone to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis

| Ref. | Study participants characteristics | Study design | Sample size | Intervention | Intervention | Diagnosis of sarcopenia | Results |

| Yurci et al[51], 2011 | mean age: 52.17; mean BMI: 27.17; CTP score: 7; setting: Turkey | Quasi experimental (pre-post intervention study) | 16 | Testosterone gel 50 mg/d in hypo gonadal men | 6 mo | Anthropometric measurement: Muscle strength and skin fold thickness | Muscle strength increased significantly 3 mo post intervention |

| Sinclair et al[52], 2016 | mean Age: 55; male 100%; mean BMI: 28.8; CTP score: 9; setting: Australia | RCT | 101 | Intramuscular testosterone undecanoate in men with low testosterone | 12 mo | APLM by DEXA | APLM and TBM were significant higher in testosterone-treated subjects. No change in mortality |

APLM: Appendicular lean mass; BMI: Body mass index.

Nutritional interventions

Total of 10 studies published between 2000-2018 on nutritional intervention to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis were included. Seven out of ten studies were randomized controlled trials, 2 were case control and 1 was longitudinal (pre-post intervention study). Four of the studies were conducted in Japan, four from the Europe, one study was conducted in Mexico, and one was from India. Nutritional intervention duration ranged from 6 to 56 wk and the sample size ranged from 21 to 174 patients with cirrhosis. Nine studies were done in compensated cirrhosis and one involved decompensated cirrhotic patients. In seven of the included studies supplementation with branched chain amino acids (BCAA) was used as intervention with regular diet, or a high protein and high fiber diet or with late evening snack (LES). Study conducted by Yamanaka-Okumura et al[30] investigated the effect of LES with meals in patients with cirrhosis. Overall, nutritional interventions with BCAA were found to be effective in 60% of the studies. However, four studies showed no significant changes in the sarcopenia measured by anthropometric analysis following nutritional interventions.

Exercise interventions

Details of the studies focused on the exercise intervention are presented in Table 2. Out of five studies four were randomized control trials were conducted between 2014-2018. 2 studies were done in Canada, one in Mexico, and 2 in Europe. Duration of exercise intervention was lasted between 8 to 14 wk. Supervised physical exercise was used as intervention in four of the included studies. All studies showed significant improvement in muscle mass, physical function and muscle strength post exercise intervention.

Combined interventions

Four studies based on combined exercise and nutritional supplementation were included in the systematic review. Three studies used pre-post intervention (quasi experimental) study design to evaluate the effect of combined life style intervention such exercise and nutrition on sarcopenia (details are presented in Table 3). Two studies were done in Japan and two in Spain. Interventions ranged from 12 to 52 wk and includes BCAA supplementation either with home based or supervised exercise. All these studies reported significant improvement in muscle mass, muscle strength and physical function. However, Berzigotti et al[47] reported no significant changes in the lean muscle mass following 16 wk of life style intervention which include reduce calorie intake of 500-1000 Kcal/d along with 60 min session of moderate supervised exercise.

TIPS

Efficacy of TIPS in the treatment of sarcopenia was assessed in the four studies. All these studies were done in decompensated cirrhotic patients. Three studies were conducted in Europe while one was done in USA. Sample size in the studies ranged from 21-132 patients. Most of the studies utilized pre-post intervention study design and reported significant improvement in sarcopenia following TIPS. However, Plauth et al[48] reported no change in the resting energy expenditure and fat mass.

Testosterone

Two studies (one RCT and one non RCT pre-post intervention) on the effect of testosterone on sarcopenia in cirrhosis met eligibility criteria. These studies were done in Turkey and Australia. Study by Yurci et al[51], enrolled 16 males with compensated cirrhosis with mean BMI of 27. Study lasted for 6 mo and showed significant increase in muscle strength. Similar results were reported by a large randomized controlled trial in 2016 conducted by Sinclair et al[52].

Risk of bias

Detailed description of the risk of bias in randomized and non-randomized (pre-post intervention studies and case-control studies) is presented in Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6.

Summary of scoring results in terms of risk of bias (low, medium or high) of all studies included in the review

| Ref. |

Question and risk of bias |

||||||||||

| Study design | Study participants | Measurements of intervention | Measurements of outcomes | Confounding factors | Blinding | % follow-up | Info on non-participants | Analysis | Sample size | Overall quality rating: Risk of bias | |

| Debette-Gratien et al[40], 2015 | +1 | +1 | -1 | +1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | +1 | 0 | -1 | 0 = medium risk |

| Berzigotti et al[47], 2017 | +1 | +1 | +1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | -1 | 5 = low risk |

| Hiraoka et al[46], 2017 | +1 | 0 | +1 | +1 | -1 | 0 | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | 4 = low risk |

| Nishida et al[45], 2016 | +1 | -1 | -1 | +1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | +1 | 0 | -1 | -2 = medium risk |

| Montomoli et al[50], 2010 | +1 | -1 | 0 | +1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | +1 | 0 | -1 | -1 = medium risk |

| Ohara et al[38], 2018 | +1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | -1 | +1 | 0 | +1 = medium risk |

| Okumura et al[30], 2006 | -1 | -1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | +1 = medium risk |

| Plauth et al[48], 2004 | +1 | -1 | 0 | +1 | -1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | -1 | +1 = medium risk |

| Tsein et al[49], 2013 | +1 | 0 | -1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | -1 | +1 | -1 | -1 = medium risk |

| Yurci et al[51], 2011 | +1 | +1 | -1 | 0 | -1 | 0 | 0 | -1 | +1 | -1 | -1 = medium risk |

| Kitajima et al[37], 2017 | +1 | +1 | 0 | +1 | 0 | 0 | +1 | +1 | +1 | -1 | 5 = low risk |

Total score -9 to -3 = high risk of bias; -2 to +3 = medium risk of bias; +4 to +10 = low risk of bias.

Table 7.

Risk of bias in randomized controlled trials

| Ref. | Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Allocation concealment (Selection bias) | Blinding of participants and personnel’s (performance bias) | Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (Attrition bias) | Selective Reporting (Reporting bias) | Other bias |

| Marchesini et al[29], 2003 | + | - | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Nakaya et al[31], 2007 | + | - | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Les et al[32], 2011 | + | + | ? | ? | - | ? | ? |

| Sorrentino et al[33], 2012 | + | ? | - | - | - | - | ? |

| Dupont et al[34], 2012 | + | ? | - | - | ? | ? | ? |

| Maharshi et al[35], 2016 | + | + | - | - | + | ? | ? |

| Ruiz-Margain et al[36], 2017 | + | ? | - | - | ? | - | ? |

| Zenith et al[39], 2014 | + | + | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Roman et al[41], 2016 | + | + | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Kruger et al[43], 2018 | + | + | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Roman et al[44], 2014 | + | ? | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Macias-Rodriguez et al[42], 2016 | + | + | - | - | - | ? | ? |

| Sinclair et al[52], 2016 | + | + | ? | ? | - | ? | ? |

DISCUSSION

It has been established that sarcopenia has an independent association with adverse outcomes in patients with cirrhosis which includes increased morbidity, mortality and cost of recurrent hospitalization from its complications[53]. In this systematic review we assessed and qualitatively analyzed the evidence regarding relationship between interventions such as nutritional supplementation, exercise, combined life style, hormonal replacement with testosterone and trans-jugular portosystemic shunt to improve muscle mass, strength and physical function in patients with established cirrhosis. Few of the included studies also showed improved health related quality of life, decreased hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), improvement in hepatic encephalopathy and recurrent ascites following these interventions[32,33,47]. Several systematic reviews have been published which were aimed to establish the relationship between exercise and diet quality with sarcopenia in older adults[54,55]. However, this is the first attempt to systematically review the published literature on interventions to improve sarcopenia in cirrhotic patients.

There is strong body of evidence that BCAA (leucine, isoleucine and valine) supplementation improves protein synthesis, glucose and lipid metabolism, hepatocyte proliferation, decrease oxidative stress in the hepatocytes and ameliorate insulin resistance in patients with liver cirrhosis[56]. However, studies published by Yamanaka-Okumara et al[30] showed no significant changes in the muscle mass and strength following BCAA supplementation with LES, potentially due to shorter duration of the intervention (1 wk only). Similarly, Nakaya et al[31], Sorrentino et al[33] and Dupont et al[34], did not showed improvement in the anthropometric measurement following LES with BCAA supplementation possibly due to small sample size and shorter duration of intervention. Timing of BCAA administration, dose and whether BCAA was supplemented with nutritional education could be another possible explanation for these studies not showing significant improvement in muscle mass.

Existing data on the effects of exercise in cirrhosis is limited and controversial especially in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. It has been reported that acute exercise can induce oxidative stress and proinflammatory cytokines synthesis, which can lead to liver damage, portal hypertension and development of complications[57]. A case series of 8 patients with cirrhosis published in 1996 by García-Pagàn et al[58] reported significant worsening of HVPG following moderate exercise training which could lead to increased risk of variceal bleeding. In contrary, recent pre-post intervention study by Berzigotti et al[47] on combined life style intervention reported improvement in HVPG following 16 wk of life style intervention. However, these patients were on non-selective beta blockers for primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage. Evidence is lacking on the effect of anaerobic-high intensity interval exercise and resistance training in cirrhotic adults with sarcopenia. Most of the studies included in this review, focused on aerobic exercise intervention. A recently published abstract of randomized control trial by Aamann et al[59], not included in this review, evaluated the effect of resistance training with adequate protein intake showed significant increase in muscle mass, strength and quality of life scores. Similar to nutrition interventions, differences in the type of exercises, in the duration of the sessions, in the number of patients per session, supervised vs home based exercise found to effect outcomes in cirrhotic patients.

Based on this review, early supervised exercise intervention with BCAA supplementation can be considered for patients with cirrhosis and sarcopenia. While BCAA approximately costs $20-50 for 30 servings it is relatively cost effective given that 60% of the studies showed improvement of patient’s sarcopenia[60]. TIPS cannot be concluded regarding recommendations given that the studies had small numbers of patients and one of four studies did not show improvement. Testosterone while it showed improvement in the two studies used for secondary sarcopenia from cirrhosis should be used with caution given its known side effects of increased cancer risks especially in this population[30]. However, hypogonadism due to cirrhosis is well understood. Patients with low testosterone and increased sarcopenia may thus benefit from supplementation and careful clinical screening and monitoring for side effects of supplementation.

The 24 studies included in this review highlight several strengths and limitations. Strengths of these studies include that they were conducted in patients with both compensated (mainly exercise, nutritional supplementation and life style interventions) and decompensated cirrhosis (mainly TIPS). Additionally, these studies were conducted in many countries across the world capturing a diverse patient population and diverse causation for cirrhosis (chronic hepatitis C infection, alcoholic cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and primary biliary cirrhosis).

Limitations of these studies include that less than half had large patient populations with more than 50 patients. Moreover, almost half were non-randomized trials. Obviously, studies that are descriptive cannot determine a cause and effect relationship and studies that are retrospective and quasi-experimental allow for bias and confounders as mentioned above. Also, the included studies were diverse in terms of study designs, interventions, and duration of intervention, follow ups, characteristics of the patients enrolled, measurement of sarcopenia and the statistical methods to control confounding variables. These inconsistencies in the methodology of these studies contribute to the heterogeneity of the results. The level of evidence according to GRADE criteria is very low or low due to marked heterogeneity of these studies. Moreover, there is only one study that showed improved mortality or morbidity by intervention and some of the rest of included studies just proved improvement of sarcopenia. Therefore, the clinical significance of the improvement of sarcopenia in cirrhotic patients remains unknown.

Future studies should include prospective multi-treatment modality approach i.e., exercise plus BCAA supplementation with specific dosage requirements in a large patient population including both those with compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Another interesting study would be performing TIPS in patients as sarcopenia as an indication rather than bleeding from varices, refractory ascites or hydrothorax. This study would be significant because if it resulted in improvement of sarcopenia could be an early intervention for pre and post-transplant improvement of morbidity and mortality in these patients. Yet, increased likelihood of hepatic encephalopathy is always a concern in these individuals. Overall, these 24 studies highlight the need for improving patient’s secondary sarcopenia from cirrhosis to improve their outcomes and provide guidance for future possible studies.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Sarcopenia, i.e., muscle loss is now a well-recognized complication of cirrhosis; and in cases of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, it can contribute to accelerate liver fibrosis leading to cirrhosis.

Research motivation

It is imperative to study interventions which targets to improve sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

Research objectives

Aim of this systematic review of the literature was to examine the relationship between interventions and trans jugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) to improve muscle mass in cirrhosis.

Research methods

We search PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane between June-August 2018, without a limiting period and the types of articles in adult patients with sarcopenia and cirrhosis. The primary outcome of interest was improvement in muscle mass, strength and physical function interventions mentioned above.

Research results

Twenty four studies that met review inclusion criteria were identified. The studies were diverse in terms of the design, setting, interventions, and outcome measurements. Only qualitative synthesis of evidence due to heterogeneity amongst studies was performed. Risk of bias was medium in most of the included studies, and low quality of evidence showed improvement in the muscle mass, strength and physical function following aerobic exercise. There are 60% of the included studies on the nutritional intervention, 100% of the studies on testosterone replacement in hypogonadal men and trans-jugular portosystemic shunt were proved to be effective in improving sarcopenia in cirrhosis.

Research conclusions

Although the quality of evidence is low, the findings of this systematic review suggest improvement in the sarcopenia in cirrhosis with exercise, nutritional interventions, hormonal and TIPS interventions.

Research perspectives

High quality randomized controlled trials are needed to further strengthen these findings.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: No potential conflicts of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: October 18, 2018

First decision: November 29, 2018

Article in press: December 12, 2018

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Choi MR, Ramsay MA, Stavroulopoulos A, Nechifor G S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

Contributor Information

Maliha Naseer, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, East Carolina University, Greenville, NC 27834, United States.

Erica P Turse, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, St Joseph Hospital Medical Center/Creighton University, Phoenix, AZ 85013, United States.

Ali Syed, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Francis E Dailey, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Mallak Zatreh, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Veysel Tahan, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States. tahanv@health.missouri.edu.

References

- 1.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:337–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Metter EJ, Conwit R, Tobin J, Fozard JL. Age-associated loss of power and strength in the upper extremities in women and men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52:B267–B276. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.5.b267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lautz HU, Selberg O, Körber J, Bürger M, Müller MJ. Protein-calorie malnutrition in liver cirrhosis. Clin Investig. 1992;70:478–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00210228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montano-Loza AJ, Meza-Junco J, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Baracos VE, Bain VG, Sawyer MB. Muscle wasting is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:166–173, 173.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasarathy S. Consilience in sarcopenia of cirrhosis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2012;3:225–237. doi: 10.1007/s13539-012-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das A, Dhiman RK, Saraswat VA, Verma M, Naik SR. Prevalence and natural history of subclinical hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:531–535. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kalaitzakis E, Josefsson A, Castedal M, Henfridsson P, Bengtsson M, Andersson B, Björnsson E. Hepatic encephalopathy is related to anemia and fat-free mass depletion in liver transplant candidates with cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:577–584. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.777468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Periyalwar P, Dasarathy S. Malnutrition in cirrhosis: contribution and consequences of sarcopenia on metabolic and clinical responses. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16:95–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merli M, Riggio O, Dally L. Does malnutrition affect survival in cirrhosis? PINC (Policentrica Italiana Nutrizione Cirrosi) Hepatology. 1996;23:1041–1046. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaido T, Ogawa K, Fujimoto Y, Ogura Y, Hata K, Ito T, Tomiyama K, Yagi S, Mori A, Uemoto S. Impact of sarcopenia on survival in patients undergoing living donor liver transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1549–1556. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tandon P, Ney M, Irwin I, Ma MM, Gramlich L, Bain VG, Esfandiari N, Baracos V, Montano-Loza AJ, Myers RP. Severe muscle depletion in patients on the liver transplant wait list: its prevalence and independent prognostic value. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1209–1216. doi: 10.1002/lt.23495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsien C, Garber A, Narayanan A, Shah SN, Barnes D, Eghtesad B, Fung J, McCullough AJ, Dasarathy S. Post-liver transplantation sarcopenia in cirrhosis: a prospective evaluation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1250–1257. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamaguchi Y, Kaido T, Okumura S, Fujimoto Y, Ogawa K, Mori A, Hammad A, Tamai Y, Inagaki N, Uemoto S. Impact of quality as well as quantity of skeletal muscle on outcomes after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1413–1419. doi: 10.1002/lt.23970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoshida A, Ueda T, Tanaka Y, Imura S, Konishi F, Uchida M, Kita K, Nakamura T. [Peripheral blood involvement accompanied with hypercalcemia in the malignant lymphoma of iliac bone] Rinsho Ketsueki. 1991;32:404–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loguercio C, Sava E, Sicolo P, Castellano I, Narciso O. Nutritional status and survival of patients with liver cirrhosis: anthropometric evaluation. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 1996;42:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selberg O, Böttcher J, Tusch G, Pichlmayr R, Henkel E, Müller MJ. Identification of high- and low-risk patients before liver transplantation: a prospective cohort study of nutritional and metabolic parameters in 150 patients. Hepatology. 1997;25:652–657. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvares-da-Silva MR, Reverbel da Silveira T. Comparison between handgrip strength, subjective global assessment, and prognostic nutritional index in assessing malnutrition and predicting clinical outcome in cirrhotic outpatients. Nutrition. 2005;21:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guglielmi FW, Panella C, Buda A, Budillon G, Caregaro L, Clerici C, Conte D, Federico A, Gasbarrini G, Guglielmi A, Loguercio C, Losco A, Martines D, Mazzuoli S, Merli M, Mingrone G, Morelli A, Nardone G, Zoli G, Francavilla A. Nutritional state and energy balance in cirrhotic patients with or without hypermetabolism. Multicentre prospective study by the 'Nutritional Problems in Gastroenterology' Section of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peng S, Plank LD, McCall JL, Gillanders LK, McIlroy K, Gane EJ. Body composition, muscle function, and energy expenditure in patients with liver cirrhosis: a comprehensive study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1257–1266. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.5.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HY, Jang JW. Sarcopenia in the prognosis of cirrhosis: Going beyond the MELD score. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7637–7647. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i25.7637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meza-Junco J, Montano-Loza AJ, Baracos VE, Prado CM, Bain VG, Beaumont C, Esfandiari N, Lieffers JR, Sawyer MB. Sarcopenia as a prognostic index of nutritional status in concurrent cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:861–870. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318293a825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janssen I, Shepard DS, Katzmarzyk PT, Roubenoff R. The healthcare costs of sarcopenia in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:80–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gillette-Guyonnet S, Nourhashemi F, Lauque S, Grandjean H, Vellas B. Body composition and osteoporosis in elderly women. Gerontology. 2000;46:189–193. doi: 10.1159/000022158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgartner RN. Body composition in healthy aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;904:437–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castaneda C, Bermudez OI, Tucker KL. Protein nutritional status and function are associated with type 2 diabetes in Hispanic elders. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:89–95. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Viswanathan M, Berkman ND. Development of the RTI item bank on risk of bias and precision of observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012;65:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JPT, Sally G. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available from: http://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/

- 29.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Merli M, Amodio P, Panella C, Loguercio C, Rossi Fanelli F, Abbiati R Italian BCAA Study Group. Nutritional supplementation with branched-chain amino acids in advanced cirrhosis: a double-blind, randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1792–1801. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamanaka-Okumura H, Nakamura T, Takeuchi H, Miyake H, Katayama T, Arai H, Taketani Y, Fujii M, Shimada M, Takeda E. Effect of late evening snack with rice ball on energy metabolism in liver cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2006;60:1067–1072. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakaya Y, Okita K, Suzuki K, Moriwaki H, Kato A, Miwa Y, Shiraishi K, Okuda H, Onji M, Kanazawa H, Tsubouchi H, Kato S, Kaito M, Watanabe A, Habu D, Ito S, Ishikawa T, Kawamura N, Arakawa Y Hepatic Nutritional Therapy (HNT) Study Group. BCAA-enriched snack improves nutritional state of cirrhosis. Nutrition. 2007;23:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Les I, Doval E, García-Martínez R, Planas M, Cárdenas G, Gómez P, Flavià M, Jacas C, Mínguez B, Vergara M, Soriano G, Vila C, Esteban R, Córdoba J. Effects of branched-chain amino acids supplementation in patients with cirrhosis and a previous episode of hepatic encephalopathy: a randomized study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1081–1088. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorrentino P, Castaldo G, Tarantino L, Bracigliano A, Perrella A, Perrella O, Fiorentino F, Vecchione R, D' Angelo S. Preservation of nutritional-status in patients with refractory ascites due to hepatic cirrhosis who are undergoing repeated paracentesis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:813–822. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.07043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dupont B, Dao T, Joubert C, Dupont-Lucas C, Gloro R, Nguyen-Khac E, Beaujard E, Mathurin P, Vastel E, Musikas M, Ollivier I, Piquet MA. Randomised clinical trial: enteral nutrition does not improve the long-term outcome of alcoholic cirrhotic patients with jaundice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1166–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maharshi S, Sharma BC, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S, Sharma P. Efficacy of Nutritional Therapy for Patients With Cirrhosis and Minimal Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:454–460.e3; quiz e33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz-Margáin A, Macías-Rodríguez RU, Ríos-Torres SL, Román-Calleja BM, Méndez-Guerrero O, Rodríguez-Córdova P, Torre A. Effect of a high-protein, high-fiber diet plus supplementation with branched-chain amino acids on the nutritional status of patients with cirrhosis. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2018;83:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.rgmx.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitajima Y, Takahashi H, Akiyama T, Murayama K, Iwane S, Kuwashiro T, Tanaka K, Kawazoe S, Ono N, Eguchi T, Anzai K, Eguchi Y. Supplementation with branched-chain amino acids ameliorates hypoalbuminemia, prevents sarcopenia, and reduces fat accumulation in the skeletal muscles of patients with liver cirrhosis. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:427–437. doi: 10.1007/s00535-017-1370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohara M, Ogawa K, Suda G, Kimura M, Maehara O, Shimazaki T, Suzuki K, Nakamura A, Umemura M, Izumi T, Kawagishi N, Nakai M, Sho T, Natsuizaka M, Morikawa K, Ohnishi S, Sakamoto N. L-Carnitine Suppresses Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2:906–918. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zenith L, Meena N, Ramadi A, Yavari M, Harvey A, Carbonneau M, Ma M, Abraldes JG, Paterson I, Haykowsky MJ, Tandon P. Eight weeks of exercise training increases aerobic capacity and muscle mass and reduces fatigue in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1920–6.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Debette-Gratien M, Tabouret T, Antonini MT, Dalmay F, Carrier P, Legros R, Jacques J, Vincent F, Sautereau D, Samuel D, Loustaud-Ratti V. Personalized adapted physical activity before liver transplantation: acceptability and results. Transplantation. 2015;99:145–150. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Román E, García-Galcerán C, Torrades T, Herrera S, Marín A, Doñate M, Alvarado-Tapias E, Malouf J, Nácher L, Serra-Grima R, Guarner C, Cordoba J, Soriano G. Effects of an Exercise Programme on Functional Capacity, Body Composition and Risk of Falls in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151652. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macías-Rodríguez RU, Ilarraza-Lomelí H, Ruiz-Margáin A, Ponce-de-León-Rosales S, Vargas-Vorácková F, García-Flores O, Torre A, Duarte-Rojo A. Changes in Hepatic Venous Pressure Gradient Induced by Physical Exercise in Cirrhosis: Results of a Pilot Randomized Open Clinical Trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7:e180. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kruger C, McNeely ML, Bailey RJ, Yavari M, Abraldes JG, Carbonneau M, Newnham K, DenHeyer V, Ma M, Thompson R, Paterson I, Haykowsky MJ, Tandon P. Home Exercise Training Improves Exercise Capacity in Cirrhosis Patients: Role of Exercise Adherence. Sci Rep. 2018;8:99. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18320-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Román E, Torrades MT, Nadal MJ, Cárdenas G, Nieto JC, Vidal S, Bascuñana H, Juárez C, Guarner C, Córdoba J, Soriano G. Randomized pilot study: effects of an exercise programme and leucine supplementation in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:1966–1975. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishida Y, Ide Y, Okada M, Otsuka T, Eguchi Y, Ozaki I, Tanaka K, Mizuta T. Effects of home-based exercise and branched-chain amino acid supplementation on aerobic capacity and glycemic control in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatol Res. 2017;47:E193–E200. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Kiguchi D, Izumoto H, Ueki H, Kaneto M, Kitahata S, Aibiki T, Okudaira T, Tomida H, Miyamoto Y, Yamago H, Suga Y, Iwasaki R, Mori K, Miyata H, Tsubouchi E, Kishida M, Ninomiya T, Kohgami S, Hirooka M, Tokumoto Y, Abe M, Matsuura B, Hiasa Y. Efficacy of branched-chain amino acid supplementation and walking exercise for preventing sarcopenia in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1416–1423. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berzigotti A, Albillos A, Villanueva C, Genescá J, Ardevol A, Augustín S, Calleja JL, Bañares R, García-Pagán JC, Mesonero F, Bosch J Ciberehd SportDiet Collaborative Group. Effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention program on portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis and obesity: The SportDiet study. Hepatology. 2017;65:1293–1305. doi: 10.1002/hep.28992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Plauth M, Schütz T, Buckendahl DP, Kreymann G, Pirlich M, Grüngreiff S, Romaniuk P, Ertl S, Weiss ML, Lochs H. Weight gain after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is associated with improvement in body composition in malnourished patients with cirrhosis and hypermetabolism. J Hepatol. 2004;40:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsien C, Shah SN, McCullough AJ, Dasarathy S. Reversal of sarcopenia predicts survival after a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:85–93. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328359a759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Montomoli J, Holland-Fischer P, Bianchi G, Grønbaek H, Vilstrup H, Marchesini G, Zoli M. Body composition changes after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in patients with cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:348–353. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yurci A, Yucesoy M, Unluhizarci K, Torun E, Gursoy S, Baskol M, Guven K, Ozbakir O. Effects of testosterone gel treatment in hypogonadal men with liver cirrhosis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35:845–854. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sinclair M, Grossmann M, Hoermann R, Angus PW, Gow PJ. Testosterone therapy increases muscle mass in men with cirrhosis and low testosterone: A randomised controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2016;65:906–913. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kallwitz ER. Sarcopenia and liver transplant: The relevance of too little muscle mass. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10982–10993. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i39.10982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bloom I, Shand C, Cooper C, Robinson S, Baird J. Diet Quality and Sarcopenia in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2018;10:308. doi: 10.3390/nu10030308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Kiesswetter E, Drey M, Sieber CC. Nutrition, frailty, and sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2017;29:43–48. doi: 10.1007/s40520-016-0709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Toshikuni N, Arisawa T, Tsutsumi M. Nutrition and exercise in the management of liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7286–7297. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i23.7286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ney M, Haykowsky MJ, Vandermeer B, Shah A, Ow M, Tandon P. Systematic review: pre- and post-operative prognostic value of cardiopulmonary exercise testing in liver transplant candidates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:796–806. doi: 10.1111/apt.13771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.García-Pagàn JC, Santos C, Barberá JA, Luca A, Roca J, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Bosch J, Rodés J. Physical exercise increases portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1300–1306. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8898644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aamann L, Dam G, Borre M, Drljevic-Nielsen A, Overgaard K, Andersen H, Vilstrup H, Aagaard NK. Resistance training improves muscle size and muscle strength in liver cirrhosis - a randomized controlled trial. J Hepatology. 2018;68:S79. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishikawa H, Osaki Y. Liver Cirrhosis: Evaluation, Nutritional Status, and Prognosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:872152. doi: 10.1155/2015/872152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]