Abstract

AIM

To assess the effect of early vs late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on mortality and readmissions in acute cholangitis, using a nationally representative sample.

METHODS

We used the 2014 National Readmissions Database to identify adult patients hospitalized with acute cholangitis who underwent therapeutic ERCP within one week of admission. Early ERCP was defined as ERCP performed on the same day of admission or the next day (days 0 or 1, < 48 h), and late ERCP was performed on days 2 to 7 of admission. Patients with severe cholangitis had any of the following additional diagnoses: Severe sepsis, septic shock, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure, or thrombocytopenia. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate the adjusted odds of association of ERCP timing with in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmissions, controlling for age, sex, severe disease and comorbidities.

RESULTS

Four thousand five hundred and seventy patients satisfied the inclusion criteria; with a mean age of 64.1 years. Of these, 66.6% had early ERCP, while 33.4% had late ERCP. Early ERCP was associated with lower in-hospital mortality [1.2% vs 2.4%, adjusted odds ratio (aOR) = 0.50, 95%CI: 0.76-0.83, P = 0.001] and lower 30-d mortality (1.5% vs 3.3%, aOR = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.33-0.69, P < 0.0001) compared to the late ERCP group. Similarly, early ERCP was associated with lower 30-d readmissions (9.7% vs 15.1%, aOR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.49-0.7, P < 0.0001). When stratified by severity of cholangitis, there was a similar benefit of early ERCP on all outcomes in those with and without severe cholangitis. The mean length of stay was higher in the late ERCP group compared to the early ERCP group (6.9 d vs 4.5 d, P < 0.0001). The mean hospitalization cost was higher in the late ERCP group ($21459 vs $16939, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION

Early ERCP is associated with lower in-hospital and 30-d mortality in those with or without severe cholangitis. Regardless of severity, we suggest performing early ERCP.

Keywords: Cholangitis, Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Mortality, Readmissions, Severity cholangitis, Length of stay, Nationwide analysis

Core tip: The impact of the timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) on outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis is unclear. Aim of this study is to assess the effect of early vs late ERCP on mortality and readmissions in acute cholangitis, using a nationally representative sample. Early ERCP was associated with a statistically significant lower in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmission rate; adjusted odds ratio 0.5, 0.48, 0.58 respectively, compared to late ERCP. When stratified by severity, a similar benefit was observed. Early ERCP may improve outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis regardless of severity.

INTRODUCTION

Acute cholangitis is an infection of the biliary tract commonly caused by partial or complete obstruction of the bile ducts. The diagnosis of acute cholangitis is based on the presence of clinical and laboratory findings of systemic inflammation and cholestasis, combined with imaging findings of obstruction[1]. The 2018 Tokyo guidelines (TG18) recommend stratifying patients into three grades of severity[1]: Grade I (mild), grade II (moderate), and grade III (severe) based on the presence of specific severity criteria. Patients with organ dysfunction (septic shock, altered mentation, respiratory insufficiency, renal, hepatic, or hematologic dysfunction) are classified as severe cholangitis, or grade “III”. Patients older than 75 years and those with leukocytosis, high fever, hyperbilirubinemia (≥ 5 mg/dL), and hypoalbuminemia are classified as moderate cholangitis, or grade “II”. Patients with mild cholangitis, or grade “I” do not have any severity criteria. Once the diagnosis of acute cholangitis is strongly suspected or confirmed, supportive care with intravenous fluids, antibiotics, and biliary drainage is indicated. The gold standard for biliary drainage is therapeutic endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). However, the optimal timing of ERCP in acute cholangitis has not been well established, and it could be dependent on the severity of cholangitis.

Studies that addressed the effect of ERCP timing on outcomes of acute cholangitis have provided mixed results. Several small, single center retrospective studies found that early ERCP (within 24 to 72 h of admission) is associated with lower in hospital and 30-d mortality, compared to late ERCP[2-5]. Other studies did not show a difference in mortality between early and late ERCP[6-9]. The association of early ERCP with outcomes could vary in patients depending on their disease severity. It is intuitive that patients with severe sepsis and septic shock require early ERCP for source control. The Tokyo 2018 guidelines recommend ERCP as soon as possible in severe cholangitis after the patient has been stabilized[10]. However, it is unclear if early ERCP is needed in mild or moderate cases. Given the conflicting results of prior studies, and the lack of stratification of patients by severity, it is unclear if early ERCP actually affects mortality in all patients with cholangitis.

In this study, we provide further clarification on the effect of ERCP timing on important short-term outcomes. Our primary aim is to compare outcomes between early and late biliary drainage by ERCP in patients admitted with acute cholangitis in a nationally representative sample. The primary outcomes of interest are in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmissions. We further examine the effect of ERCP timing on these outcomes by stratifying patients into severe and mild-moderate cholangitis. Lastly, we examine differences in length of stay and hospital costs between the two groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

We used data from the 2014 National readmission database (NRD). This large, all-payer database is developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The NRD is drawn from a sample of 22 state inpatient databases and represents 49.3% of all hospitalization in the United States[11]. Each observation in the database represents data abstracted from a hospital discharge record, and includes several demographic, clinical, and hospital related variables. Clinical variables include diagnosis and procedure variables encoded using the International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Each record could contain up to 30 diagnosis codes (dx1 to dx30) and 20 procedure codes (pr1 to pr15). The NRD also contains special linkage numbers associated with each discharge record that can be used to track patients’ admissions to any hospital statewide, but not across state lines. The Emory University institutional review board determined that the study was exempt from review because the data is de-identified and cannot be tracked to any particular subject.

Study population

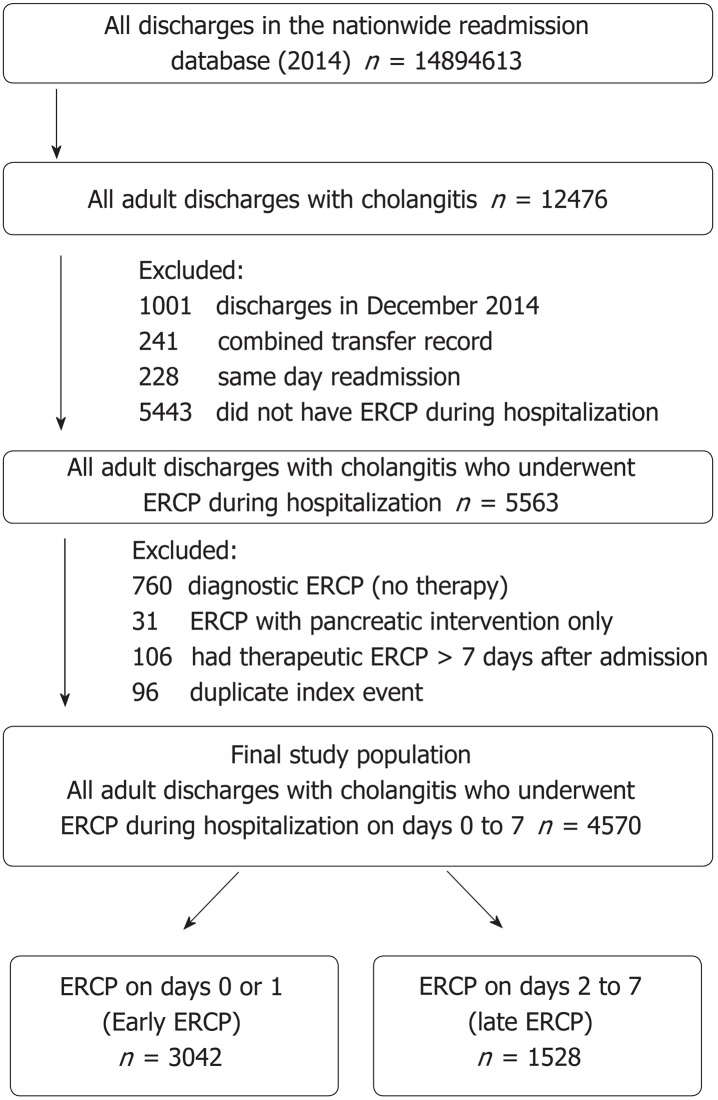

We identified all adult hospitalizations (age ≥ 18 years) with a discharge diagnosis of cholangitis (ICD 9 CM-code 576.2) in any of the first five diagnosis fields (dx1-dx5). In order to have a full 30-d post discharge period to capture readmissions, we excluded patients who were discharged in December. We also excluded records that represent same-day stay pairs of records (patient discharged and readmitted the same day), and combined transfer records (patient transferred to another hospital). These records are more complicated than regular hospitalizations and are coded differently[11]. We included records with an ICD-9-CM procedure code for therapeutic biliary ERCP performed on the day of admission (day 0) and up to 7 d after admission (day 7). “Early” ERCP was defined as therapeutic ERCP performed on the same day of admission or the following day (day 0 or 1, < 48 h after admission), and “late” ERCP was performed on days 2 to 7 post hospitalizations (days 2-7, > 48 h after admission). We excluded ERCPs performed after 7 d of admission to avoid including patients who may not have had cholangitis on admission. Therapeutic ERCP procedures included any of the following: sphincterotomy, papillotomy, dilation of ampulla or biliary duct, insertion of stent, removal of stone. Since our main objective was to look at timing of successful biliary drainage via ERCP, we excluded ERCPs that did not have accompanying therapeutic codes to avoid including patients who underwent unsuccessful procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Data selection process for acute cholangitis. Duplicate index events were identified as index admissions and readmissions within 30 d of another index admission. These were not analyzed as a separate index admission but were included in the readmission analysis. Day 0 is the day of admission. ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Study variables

We used patient’s age, sex, and several clinical diagnoses related to cholangitis to characterize the study population. Records with “severe” cholangitis were identified by any of the following conditions in the first five diagnosis fields (dx1-dx5): Severe sepsis, septic shock, systemic inflammatory response syndrome with acute organ dysfunction, acute renal failure, acute respiratory failure, thrombocytopenia, altered mental status, and abnormal coagulation. Records without these diagnoses were considered “mild to moderate” cholangitis. All ICD-9 codes that were used in the analysis are listed in Table 1. For comorbidity assessment, we used the Elixhauser comorbidity and readmission indices. These validated measures of comorbidity are developed by the AHRQ using HCUP state inpatient sample data. They are derived from 29 predefined HCUP comorbidity variables and are used to adjust for comorbidities in hospital administrative databases[12]. Other admission variables included primary payer information, weekend vs weekday admissions, length of stay, discharge disposition, and total cost for the hospitalization. For cost estimations, we converted hospital charges to cost estimates using the cost-to-charge ratios provided by the HCUP, and then inflated these costs to 2017 dollars using the consumer price index for inpatient hospital services of the US Bureau of Labor Statistics[13]. We used the special tracking variables “NRD_visitlink” and “NRD_DaysToEvent” to identify all unplanned readmissions within a 30-d period post discharge from index hospitalization.

Table 1.

International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition, clinical modification codes used in defining study variables

| Diagnosis/procedure | ICD-9 |

| Diagnosis | |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 577.1 |

| Acute Pancreatitis | 577 |

| Cholangitis | 576.1 |

| Abdominal pain | 789.x |

| Jaundice | 782.4 |

| Cholelithiasis | 574.0, 574.1, 574.2, 574.6, 574.7, 574.8, 574.9 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 574.3, 574.4, 574.5, 574.6, 574.7, 574.8, 574.9 |

| Biliary obstruction | 5762 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma of bile duct or intrahepatic duct | 1551, 1561 |

| Malignant neoplasm of pancreas | 157.x |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 1400-1729, 1740-1759, 179-1958, 20900-20924, 20925-2093, 20931-20936, 25801-25803 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1960-1991, 20970-20975, 20979, 78951 |

| Septic shock | 785.52 |

| Severe Sepsis | 995.92 |

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome with acute organ dysfunction | 995.94 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 518.81 |

| Acute kidney failure | 584.9 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2875 |

| Altered mental status | 780.97 |

| Abnormal coagulation | 790.92 |

| Procedure | |

| ERCP | |

| ERCP general code | 51.1 |

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy and papillotomy | 51.85 |

| Biliary ERCP | |

| Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiography | 51.11 |

| Endoscopic dilation of ampulla and biliary duct | 51.84 |

| Endoscopic insertion of stent (tube) into bile duct | 51.87 |

| Endoscopic removal of stone (s) from biliary tract | 51.88 |

| Pancreatic ERCP | |

| Endoscopic Retrograde Pancreatography | 52.92 |

| Endoscopic insertion of stent (tube) into pancreatic duct | 52.93 |

| Endoscopic removal of stone (s) from pancreatic duct | 52.94 |

| Endoscopic dilation of pancreatic duct | 52.98 |

ICD-9: International Classification of Diseases, ninth edition; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Outcomes

The main outcomes of interest were: (1) mortality during the index admission (in-hospital mortality); (2) total mortality during index admission or during any readmission within 30-d (30-d mortality); and (3) thirty-day hospital readmission. We performed an additional analysis to examine the effect of ERCP timing on these outcomes stratified by cholangitis severity. Secondary outcomes of interest included length of stays and hospitalization costs.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described as number (percentage); while continuous variables were reported as mean [standard deviation (SD)]. Baseline characteristics of the early and late ERCP groups were compared using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the student t test for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to compare the odds of the three outcomes (in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmissions) between the two groups. Covariates that were considered for inclusion into the model were age, sex, mortality index, and presence of severe cholangitis. The readmission index was used for 30-d readmission outcome. Covariates with P < 0.2 in univariate analysis were introduced into the model and retained if the P value was < 0.05. To assess the effect of severe cholangitis on the association of ERCP timing and outcomes, we performed an additional analysis in which we added an interaction term (timing*severity) to stratify this association based on cholangitis severity. Results of logistic regression were expressed using adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). We used a multivariable generalized linear regression model to compare the length of stay and total hospitalization costs between patients in the early and late ERCP groups. A 2-tailed P of 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance.

Sensitivity analysis

To further clarify the optimal timing of ERCP in acute cholangitis, we performed an additional analysis in which we treated the time to ERCP as a categorical variable with eight levels (days 0 to day 7), instead of a binary categorical variable. We compared the odds of outcomes between ERCP days 1 to 7, with ERCP performed on the same day of admission as a reference.

RESULTS

During the study period, there were 12,476 adult discharges with acute cholangitis, of which 4570 met the inclusion criteria and had ERCP during the admission (Figure 1). The mean age was 64.1 years (SD = 18.2), and 51.8% were females (Table 2). Of those, 1528 (33.4%) had late ERCP and 3042 (66.6%) had early ERCP. Patients who underwent early ERCP were slightly younger, had less comorbid conditions, and were less likely to be admitted during the weekend. There were no differences in the proportion of patients with severe cholangitis among the early and late ERCP group (7.7% vs 7.1%, respectively; P = 0.473).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of adult discharges with cholangitis who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography during their hospital stay (n = 4570), stratified by timing to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Nationwide Readmission Database January–November, 2014 n (%)

|

ERCP timing |

P Value | ||

| Late ERCP, 1528 (33.4) | Early ERCP, 3042 (66.6) | ||

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 65.1 (18.3) | 63.6 (18.1) | 0.0089 |

| Age category | 0.0560 | ||

| Young adults (18-39 yr) | 179 (11.7) | 378 (12.4) | |

| Middle age (40-64 yr) | 472 (30.9) | 1031 (33.9) | |

| Older adults (> 65 yr) | 877 (57.4) | 1633 (53.7) | |

| Male sex | 717 (46.9) | 1485 (48.8) | 0.2271 |

| Abdominal pain | 87 (5.7) | 115 (3.8) | 0.0030 |

| Jaundice | 115 (7.5) | 178 (5.9) | 0.0292 |

| Cholelithiasis | 430 (28.1) | 918 (30.2) | 0.5810 |

| Choledocholithiasis | 968 (63.4) | 2093 (68.8) | 0.0088 |

| Biliary obstruction | 291 (19.0) | 436 (14.3) | < 0.0001 |

| Acute pancreatitis | 238 (15.6) | 428 (14.1) | 0.1734 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 41 (2.7) | 57 (1.9) | 0.0747 |

| Malignant pancreatic neoplasm | 92 (6.0) | 117 (3.8) | 0.0009 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma of bile duct | 46 (3.0) | 69 (2.3) | 0.1300 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 95 (6.2) | 156 (5.1) | 0.1274 |

| Metastatic cancer | 78 (5.1) | 117 (3.8) | 0.0470 |

| Severe Cholangitis | 108 (7.1) | 233 (7.7) | 0.4729 |

| ≥ 4 Elixhauser comorbidities | 365 (23.9) | 549 (18.0) | < 0.0001 |

| Elixhauser mortality index mean (SD) | 6.9 (5.4) | 4.5 (3.9) | < 0.0001 |

| Elixhauser readmission index mean (SD) | 14.0 (14.3) | 11.4 (12.9) | < 0.0001 |

| ERCP techniques | |||

| Endoscopic sphincterotomy | 1057 (69.2) | 2,118 (69.6) | 0.7554 |

| Biliary/ampullary balloon dilation | 232 (15.2) | 394 (13.0) | 0.0385 |

| Biliary stent | 737 (48.2) | 1424 (46.8) | 0.3638 |

| Biliary stone extraction | 827 (54.1) | 1862 (61.2) | < 0.0001 |

| ERCP-pancreatic with intervention | 56 (3.7) | 108 (3.6) | 0.8442 |

| Admission characteristics | |||

| Weekend admission | 475 (31.1) | 615 (20.2) | < 0.0001 |

| Primary payer | 0.0002 | ||

| Medicare | 835 (54.7) | 1576 (51.8) | |

| Medicaid | 223 (14.6) | 379 (12.5) | |

| Private | 353 (23.1) | 882 (29.0) | |

| Self-pay/uninsured | 115 (7.5) | 203 (6.7) | |

| Discharge disposition | < 0.0001 | ||

| Discharged to home or self-care | 1086 (71.1) | 2441 (80.2) | |

| Transfer: Short-term hospital | 11 (0.7) | 29 (1.0) | |

| Transfer: Other type of facility | 171 (11.2) | 220 (7.2) | |

| Home health care | 217 (14.2) | 302 (9.9) | |

| Against medical advice | 6 (0.4) | 13 (0.4) | |

| Died in the hospital | 37 (2.4) | 36 (1.2) | |

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

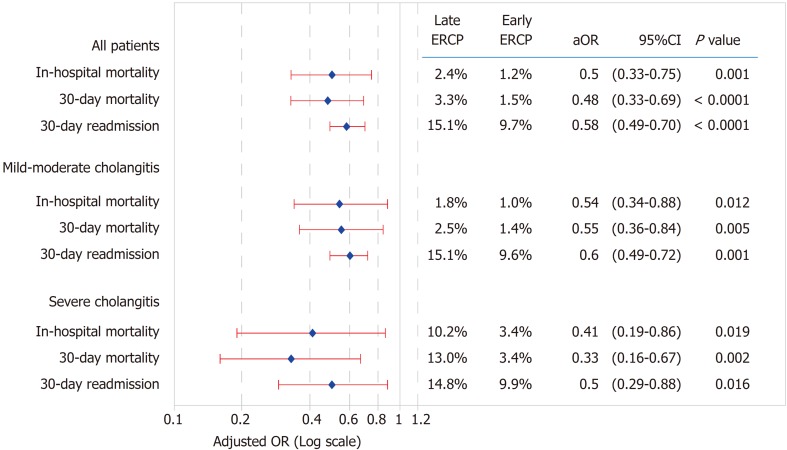

In hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmission

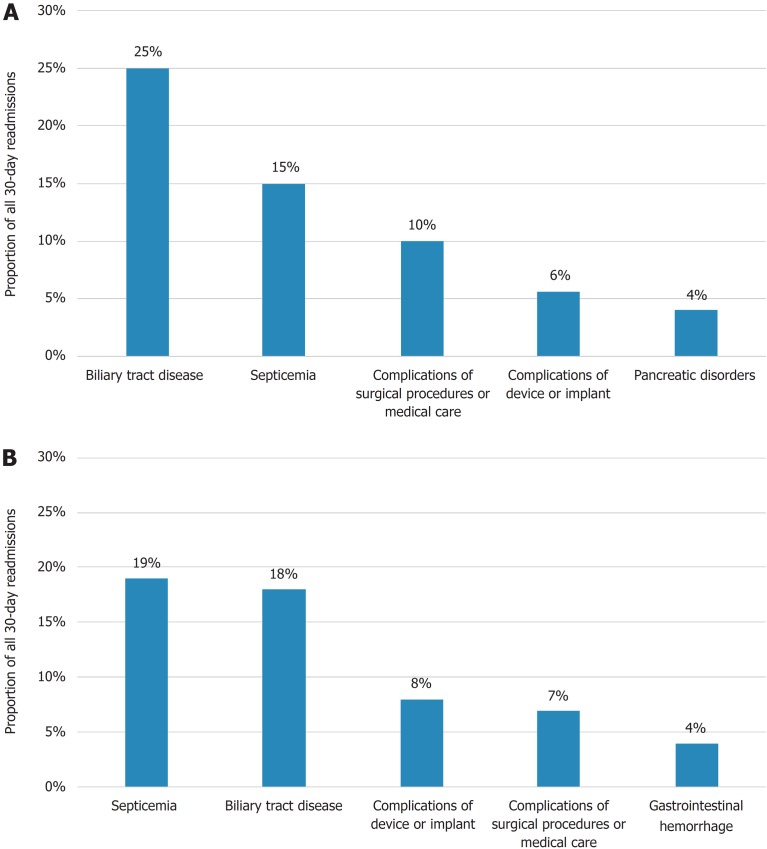

Figure 2 shows the in-hospital and 30-d outcomes among the two study groups. Patients who had early ERCP had lower in-hospital mortality (1.2% vs 2.4%, aOR 0.50, 95%CI: 0.76-0.83, P = 0.001) and lower 30-d mortality (1.5% vs 3.3%, aOR 0.48, 95%CI: 0.33-0.69, P < 0.0001) compared to the late ERCP group. Similarly, ERCP was associated with lower 30-d readmissions (9.7% vs 15.1%, aOR 0.58, 95%CI: 0.49-0.7, P < 0.0001) compared to late ERCP. As expected, mortality and readmissions rates were higher in those with severe compared to mild-moderate cholangitis. However, cholangitis severity did not affect the association between early ERCP and improved outcomes. Improved outcomes with early ERCP were present in both mild-moderate and severe cholangitis groups. The most common causes of readmissions in the early and late ERCP groups are listed in Figure 3 Septicemia and biliary disorders (cholangitis, choledocholithiasis) were the most common causes of readmission.

Figure 2.

Comparison of outcomes in patients hospitalized with cholangitis in early vs late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography stratified by cholangitis severity. Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): Performed on the same day of admission or next day (days 0 or 1, < 48 h); Late ERCP: Performed on days 2 to 7 of admission (days 2-7, > 48 h after admission). Odds ratio for mortality outcomes was obtained from multivariable logistic regression controlling for age, sex, severe disease, and mortality score. Mortality score was replaced with readmission score for readmission outcomes. OR: Odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

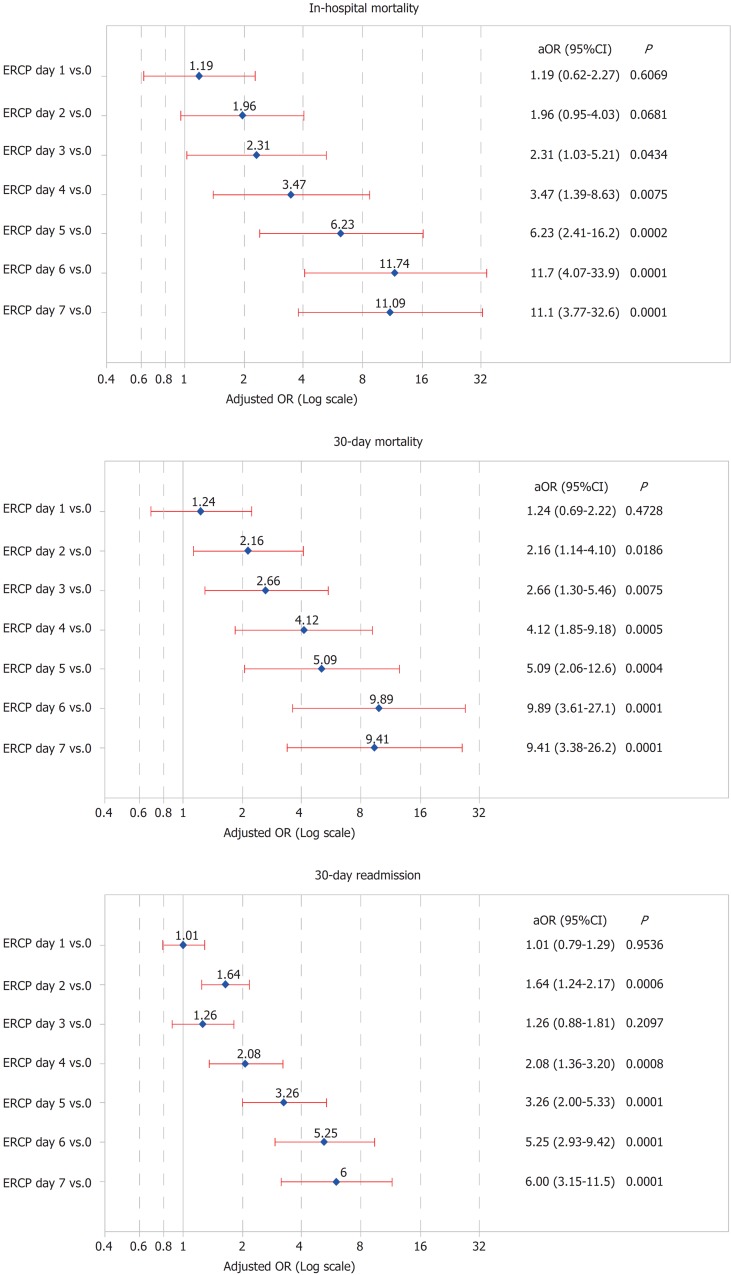

Figure 3.

Comparison of outcomes in patients hospitalized with cholangitis based on timing of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography on the day of admission (< 24 h) as the reference. Odds ratio for mortality outcomes was obtained from multivariable logistic regression controlling for age, severe disease, and mortality score. Mortality score was replaced with readmission score for readmission outcomes. aOR: Adjusted odds ratio; CI: Confidence interval; ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

Length of stay and costs of hospitalization

The mean length of stay was higher in the late ERCP group compared to the early group (6.9 d vs 4.5 d, P < 0.0001) (Table 3). The mean hospitalization cost was higher in the late ERCP group ($21459 vs $16939, P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Length of stay, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to discharge time, and hospitalization costs in patients with early and late endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

| Outcome | Late ERCP | Early ERCP | Adjusted mean difference of early vs late ERCP (95%CI) | P Value |

| Length of stay in days, mean (SD) | 6.9 (5.4) | 4.5 (3.9) | -2.1 d (1.9-2.4) | < 0.0001 |

| Hospitalization costs (mean) | $21459 | $16939 | -$3760 ($2803-$4718) | < 0.0001 |

ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

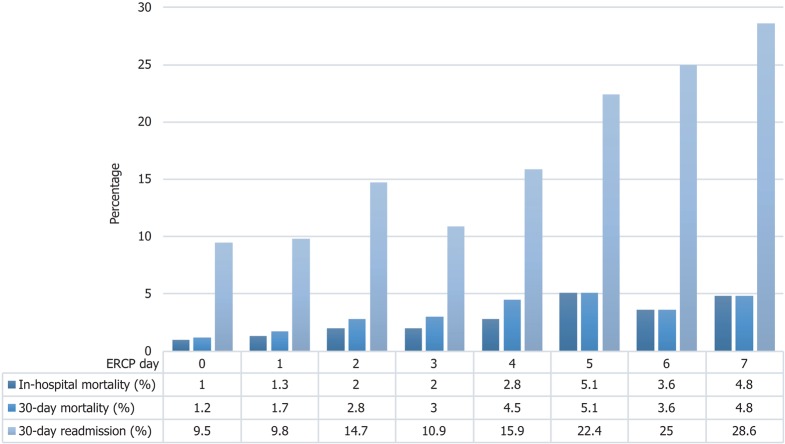

Sensitivity analysis

The results of sensitivity analysis are shown in Figures 3 and 4. The percentage of patient who experienced in hospital mortality, 30-d mortality and 30-d readmission increased with increasing days to ERCP (Figure 4). There was no difference in outcomes when ERCP was performed on the day of admission or the following day (day 0 vs 1, P value > 0.05 for all outcomes) (Figure 3). Compared to the day of admission, performing the ERCP on day 2 or later was associated with statistically significant increase in risk of 30-d mortality (starting on day 2) and in-hospital mortality (starting on day 3).

Figure 4.

Outcomes in patients hospitalized with cholangitis based on timing to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography based on endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography day. Day 0 is the day of admission. ERCP: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

DISCUSSION

Acute cholangitis is considered a medical emergency, for which antibiotics and biliary drainage with ERCP are indicated. Although antibiotics can treat the infection and stabilize the patient, early biliary drainage via ERCP could improve clinical outcomes. Using a large nationally representative database, we found an association between early ERCP (< 48 h) and improved in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and readmissions. Controlling for comorbidities, ERCP within 48 h was associated with 50% lower mortality rate and up to 66% lower 30-d readmission rate. This beneficial effect is likely due early source control of the underlying infection. These findings are in line with results of previous smaller studies. A retrospective study of 203 patients undergoing ERCP for cholangitis found that ERCP after 48 h of diagnosis was associated with increased rates of persistent organ failure (aOR 3.1, 95%CI: 1.4-7.0)[2]. A retrospective study of 172 patients with acute cholangitis found that ERCP within 72 h is associated with increased risk of persistent organ failure and/or 30-d mortality (OR 3.36, 95%CI 1.12-10.20)[5]. A separate analysis of the same group of patients showed that ERCP>72 h after admission was associated with increased rate of 30-d readmission[14]. Another single-center study of 90 patients showed that delayed (> 72 h) or failed ERCP is associated with increased incidence of composite outcome of mortality, persistent organ failure, and admission to the intensive care unit (OR 7.8, P = 0.04)[3]. A recent single center study from Denmark found that ERCP within 24 h was associated with lower 30-d mortality (OR 0.23, 95%CI: 0.05-0.95)[4]. Several similar retrospective studies did not find a difference in mortality between early and late ERCP[6-9]. This could be related to the low statistical power of some of these studies, and the low incidence of mortality in some cohorts. The results of our large-database analysis reaffirm the association of early ERCP with improved outcomes in patients admitted with acute cholangitis. In the literature, there is no clear definition of “Early” ERCP, which has been defined anywhere between 24 to 72 h from admission. We found that ERCP on the day following the day of admission was not associated with worse outcomes compared to ERCP on the day of admission (< 24 h). However, ERCP beyond 48 h was significantly associated with increased 30-d mortality (Figure 5B). Overall, there was stepwise increase in all primary outcomes with each one-day delay in ERCP (Figures 3 and 4). While the decision on timing of ERCP has to be individualized for every patient, we suggest that biliary drainage via ERCP should not be delayed beyond 48 h of admission admitted with acute cholangitis. This also is a clinically practical time to allow supportive care and possibly transfer to facilities with ERCP capabilities.

Figure 5.

Top reasons for 30-d readmission after a hospitalization with acute cholangitis, stratified by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography timing. A: Early endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) group (days 0 or 1, < 48 h); B: Late ERCP group (days 2-7, > 48 h after admission). Biliary tract disease included cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, and cholecystitis.

The clinical outcomes of patients admitted with cholangitis vary considerably depending on the severity of cholangitis. In a retrospective study of 6063 patients with acute cholangitis, 30-d mortality was 1.2% in mild cholangitis, 2.6% in moderate cholangitis, and 5.1% in severe disease[15]. The same study found that urgent (< 24 h) or early (< 48 h) ERCP was associated with improved mortality, but only in patients with moderate cholangitis. The timing of ERCP did not influence 30-d mortality in the mild or severe disease groups. However, this study also included patients who did not undergo ERCP in the “late” ERCP group. We found that the association of early ERCP within 48 h was present in both severe and mild-moderate cholangitis (Figure 2). This has important clinical implications. Biliary drainage in mild or moderate cholangitis is widely considered less urgent than in patients with severe disease. The Tokyo 2018 guidelines recommend antibiotics for patients with mild cholangitis, and ERCP only if the patients do not respond to antibiotics[10]. In practice, these patients often receive antibiotics, followed by ERCP on an elective basis. In patients with moderate cholangitis, the same guidelines recommend “early” ERCP. While we could not differentiate between mild and moderate cases, our results suggest that in patients without severe disease, ERCP should be performed within 48 h of diagnosis. It might not be appropriate to rely on antibiotics alone and delay ERCP in patients with mild cholangitis until they progress to moderate or severe disease. Early (< 48 h) definitive management is appropriate to treat the underlying obstruction and infection regardless of how stable the patient appears initially[16]. Further studies that utilize a large number of patients with confirmed mild cholangitis could shed more light on the optimal timing of ERCP in this subgroup of patients.

We observed that early ERCP is also associated with lower 30-d readmission. Thirty-day readmission was 15.1% in the late ERCP group compared to 9.7% in the early group (adjusted OR 0.58, 95%CI: 0.49-0.7, P < 0.0001). Only one previous small study (n = 168) showed a similar association between delayed ERCP > 48 h and higher 30-d readmissions (OR 2.47; 95%CI: 1.01-6.07)[14]. In our analysis, we found that the most common reasons for readmissions were similar in the early and late ERCP groups, with septicemia and recurrent biliary disease (cholangitis, choledocholithiasis) being the most common (Figure 5). Although the exact mechanism how early ERCP decreases readmissions is not entirely clear, we hypothesize that early ERCP might reduce risk of bacteremia and end organ damage which reduces morbidity and future readmissions.

Our results show an association between early ERCP and reduced length of hospital stay (mean difference of 2.1 d), and lower hospitalization costs (mean difference of $3760). This is similar to previous studies that addressed this topic[4,8,17]. This highlights the importance of definitive therapy not only to improve outcomes but also to reduce costs associated with cholangitis hospitalizations.

Strengths of our study include the large sample size that allowed for multivariable analysis and stratification per disease severity groups. The large sample size and longitudinal nature of the database allowed us to examine important in-hospital and 30-d mortality outcomes, rather than surrogate outcomes such as persistent organ failure, ICU admissions, and clinical improvement[2,3,7]. The database contains records that are representative of the general US population, with a mixture of choledocholithiasis and malignant obstruction. It also captures statewide readmissions, which overcomes the limitation of single center studies that capture center-specific readmissions and outcomes.

There are several limitations to our analysis. Similar to most administrative databases, the NRD does not contain important clinical information such as laboratory values, medications, and results of imaging studies. We relied on ICD-9 codes for data collection, which could be incomplete or inaccurate in documenting diagnosis and procedures. When considering ERCP timing and outcomes, there is a risk of selection bias, where healthier patients undergo early ERCP, while sicker once undergo later ERCP. However, we conducted a multivariable analysis controlling for several confounders including mortality and readmission scores, and the presence of severe disease. We also stratified the results into severe and mild-moderate disease, and this showed a similar association of early ERCP with improved outcomes. Using the NRD, we can only evaluate for the present of the diagnosis on admission, but cannot identify the exact time of diagnosis or the onset of symptoms.

In conclusion, in this large nationally representative sample of patients with acute cholangitis, early ERCP within 48 h of admission was associated with significant decrease in in-hospital and 30-d mortality, and readmissions. ERCP within 48 h was also associated with decreased hospital length of stay and costs. We recommend performing ERCP within 48 h in patients presenting with acute cholangitis regardless of disease severity.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Acute cholangitis is associated with a high mortality when the diagnosis and treatment is delayed. After the diagnosis is made, the most common method for source control is endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The exact timing of ERCP and its outcomes remains unclear.

Research motivation

The recent 2018 Tokyo guidelines suggest “early” ERCP for mild cholangitis, and “urgent” ERCP for severe cholangitis with no clear defining parameters.

Research objectives

The objectives of this study was to determine the effect of early ERCP vs late ERCP on mortality and readmissions in a large nationally representative sample with acute cholangitis. This could help determine the optimal timing for ERCP as a guide to practicing clinicians.

Research methods

We used the 2014 National Readmissions Database to identify patients hospitalized with acute cholangitis. Early ERCP was defined as ERCP performed < 48 h from admission, and late ERCP was defined as ERCP performed > 48 h. Multivariate logistic regression was used to calculate the adjusted odds of association of ERCP timing with in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, and 30-d readmissions, controlling for age, sex, severe disease and comorbidities.

Research results

Four thousand five hundred and ninety-two patients satisfied the inclusion criteria; 65.9% had early ERCP, while 34.1% had late ERCP. Early ERCP was associated with lower in-hospital mortality (1.2% vs 2.4%) adjusted odds ratio (aOR), lower 30-d mortality (1.5% vs 3.3%), and a lower 30-d readmission rate (9.7% vs 15.1%). When stratified by severity of cholangitis, there was a similar benefit.

Research conclusion

There is a clear benefit from performing an early ERCP, specifically < 48 h from admission, for biliary drainage in patients with acute cholangitis regardless of severity. The benefits include, lower in-hospital mortality, 30-d mortality, 30-d readmission and reduced hospitalization costs.

Research prospective

Early ERCP seems to offer a mortality benefit compared to later ERCP. This data adds to the body of evidence from other studies about the benefit of early ERCP. Therefore hospitals should have the resources to perform ERCP early in patients with cholangitis, regardless of severity.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and deemed exempt from review by the Emory University Institutional Review Board because the database is publicly available and does not contain any identifiable information that can be linked to any specific subject.

Informed consent statement: Informed consent was not required as this research involves an administrative database and does not contain any identifiable information that can be linked to any specific subject.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors report no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: July 30, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Article in press: December 13, 2018

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: de Moura DTH, Dhaliwal HS, Lei J, Shi H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

Contributor Information

Ramzi Mulki, Department of Medicine, Division of Digestive Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30303, United States.

Rushikesh Shah, Department of Medicine, Division of Digestive Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30303, United States.

Emad Qayed, Department of Medicine, Division of Digestive Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA 30303, United States; Grady Memorial Hospital, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30303, United States. eqayed@emory.edu.

References

- 1.Miura F, Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Asbun HJ, Pitt HA, Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, Han HS, Kim MH, Hwang TL, Chen MF, Huang WS, Kiriyama S, Itoi T, Garden OJ, Liau KH, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Gouma DJ, Belli G, Dervenis C, Jagannath P, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Suzuki K, Yoon YS, de Santibañes E, Giménez ME, Jonas E, Singh H, Honda G, Asai K, Mori Y, Wada K, Higuchi R, Watanabe M, Rikiyama T, Sata N, Kano N, Umezawa A, Mukai S, Tokumura H, Hata J, Kozaka K, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, Yokoe M, Kimura T, Kitano S, Inomata M, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: initial management of acute biliary infection and flowchart for acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:31–40. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee F, Ohanian E, Rheem J, Laine L, Che K, Kim JJ. Delayed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is associated with persistent organ failure in hospitalised patients with acute cholangitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:212–220. doi: 10.1111/apt.13253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khashab MA, Tariq A, Tariq U, Kim K, Ponor L, Lennon AM, Canto MI, Gurakar A, Yu Q, Dunbar K, Hutfless S, Kalloo AN, Singh VK. Delayed and unsuccessful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography are associated with worse outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1157–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan M, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, Laursen SB. Association between early ERCP and mortality in patients with acute cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navaneethan U, Gutierrez NG, Jegadeesan R, Venkatesh PG, Sanaka MR, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Factors predicting adverse short-term outcomes in patients with acute cholangitis undergoing ERCP: A single center experience. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;6:74–81. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v6.i3.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwed AC, Boggs MM, Pham XD, Watanabe DM, Bermudez MC, Kaji AH, Kim DY, Plurad DS, Saltzman DJ, de Virgilio C. Association of Admission Laboratory Values and the Timing of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography With Clinical Outcomes in Acute Cholangitis. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1039–1045. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang SE, Park SW, Lee BS, Shin CM, Lee SH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, Park JK, Hwang JH. Management for CBD stone-related mild to moderate acute cholangitis: urgent versus elective ERCP. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2082–2087. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2595-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hou LA, Laine L, Motamedi N, Sahakian A, Lane C, Buxbaum J. Optimal Timing of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in Acute Cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:534–538. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aboelsoud M, Siddique O, Morales A, Seol Y, Al-Qadi M. Early biliary drainage is associated with favourable outcomes in critically-ill patients with acute cholangitis. Prz Gastroenterol. 2018;13:16–21. doi: 10.5114/pg.2018.74557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiriyama S, Kozaka K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Gabata T, Hata J, Liau KH, Miura F, Horiguchi A, Liu KH, Su CH, Wada K, Jagannath P, Itoi T, Gouma DJ, Mori Y, Mukai S, Giménez ME, Huang WS, Kim MH, Okamoto K, Belli G, Dervenis C, Chan ACW, Lau WY, Endo I, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Baron TH, de Santibañes E, Teoh AYB, Hwang TL, Ker CG, Chen MF, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi IS, Yoon DS, Higuchi R, Kitano S, Inomata M, Deziel DJ, Jonas E, Hirata K, Sumiyama Y, Inui K, Yamamoto M. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute cholangitis (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:17–30. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.NRD Database Documentation. 2017. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available from: URL: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/nrddbdocumentation.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying Increased Risk of Readmission and In-hospital Mortality Using Hospital Administrative Data: The AHRQ Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Med Care. 2017;55:698–705. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lian M, Li B, Xiao X, Yang Y, Jiang P, Yan L, Sun C, Zhang J, Wei Y, Li Y, Chen W, Jiang X, Miao Q, Chen X, Qiu D, Sheng L, Hua J, Tang R, Wang Q, Eric Gershwin M, Ma X. Comparative clinical characteristics and natural history of three variants of sclerosing cholangitis: IgG4-related SC, PSC/AIH and PSC alone. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Navaneethan U, Gutierrez NG, Jegadeesan R, Venkatesh PG, Butt M, Sanaka MR, Vargo JJ, Parsi MA. Delay in performing ERCP and adverse events increase the 30-day readmission risk in patients with acute cholangitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kiriyama S, Takada T, Hwang TL, Akazawa K, Miura F, Gomi H, Mori R, Endo I, Itoi T, Yokoe M, Chen MF, Jan YY, Ker CG, Wang HP, Wada K, Yamaue H, Miyazaki M, Yamamoto M. Clinical application and verification of the TG13 diagnostic and severity grading criteria for acute cholangitis: an international multicenter observational study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2017;24:329–337. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu MM, Carr-Locke DL. Early ERCP for severe cholangitis? Of course! Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:193–195. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parikh MP, Wadhwa V, Thota PN, Lopez R, Sanaka MR. Outcomes Associated With Timing of ERCP in Acute Cholangitis Secondary to Choledocholithiasis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52:e97–e102. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]