Abstract

Background

Mastectomy rates among women with early breast cancer in Asia have traditionally been high. This study assessed trends in the surgical management of young women with early‐stage breast cancer in Asian settings. Survival in women treated with breast‐conserving surgery (BCS; lumpectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy) and those undergoing mastectomy was compared.

Methods

Young women (aged less than 50 years) newly diagnosed with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer in four hospitals in Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong in 1990–2012 were included. Overall survival (OS) was compared for patients treated by BCS and those who had a mastectomy. Propensity score analysis was used to account for differences in demographic, tumour and treatment characteristics between the groups.

Results

Some 63·5 per cent of 3536 women underwent mastectomy. Over a 15‐year period, only a modest increase in rates of BCS was observed. Although BCS was significantly associated with favourable prognostic features, OS was not significantly different for BCS and mastectomy; the 5‐year OS rate was 94·9 (95 per cent c.i. 93·5 to 96·3) and 92·9 (91·7 to 94·1) per cent respectively. Inferences remained unchanged following propensity score analysis (hazard ratio for BCS versus mastectomy: 0·81, 95 per cent c.i. 0·64 to 1·03).

Conclusion

The prevalence of young women with breast cancer treated by mastectomy remains high in Asian countries. Patients treated with BCS appear to survive as well as those undergoing mastectomy.

Introduction

Although young women with breast cancer have conventionally been more likely to undergo breast‐conserving surgery (BCS; lumpectomy with adjuvant radiotherapy), concerns regarding recurrence and reduced survival may influence patients to opt for mastectomy1 2. A number of studies investigating trends in surgical management of breast cancer in the USA and Europe have highlighted that younger patients are increasingly being treated by mastectomy3 4.

Compared with Europe and the USA3 4, rates of BCS have traditionally been very low in Asian settings. The high use of mastectomy in Asia has been highlighted in a number of studies1 5, 6, 7. A Malaysian study1 showed that approximately one in two patients with stage I breast cancer opted for mastectomy. Similarly, a small‐scale study in Singapore7 revealed that about 75 per cent of women with breast cancer aged under 40 years underwent mastectomy.

Although previous clinical trials8 9 have reported equivalent survival outcomes between patients receiving BCS and those having a mastectomy, they largely included older women. Observational studies investigating the impact of type of surgery on survival of young women with breast cancer have yielded conflicting results. A meta‐analysis10 published in 2015 did not find a significant difference in risk of mortality between young women (aged less than 40 years) undergoing BCS and those having a mastectomy. A prospective cohort study11 of young women in Denmark with T1–2 N0 M0 breast cancer pointed to an increased risk of breast cancer‐specific and all‐cause mortality associated with BCS.

This study aimed to determine trends in surgical management among young women with early‐stage breast cancer in an Asian setting, and to compare survival in women treated with BCS and those undergoing mastectomy.

Methods

Data obtained from the hospital‐based cancer registries of four tertiary referral centres in Asia (University Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), Malaysia; National University and Tan Tock Seng Hospitals, Singapore; Queen Mary and Tung Wah Hospital, Hong Kong)12, 13, 14 were reviewed. Ethical approval was obtained from the National Healthcare Group review board, the Sing Health Centralized Institutional Review Board, and the respective institutional review boards of UMMC and the University of Hong Kong, and Hong Kong West Cluster, Hospital Authority, Hong Kong. Informed consent for this study was not obtained from the participants as data were collected and treated anonymously.

The study included women aged below 50 years, who were newly diagnosed with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer between 1990 and 2011. Women who had undergone lumpectomy without adjuvant radiotherapy were excluded. Patients with bilateral breast cancer or those who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy were also excluded.

Surgical management

BCS was defined as a wide local excision aiming to achieve 10‐mm macroscopically clear margins around the tumour, followed by whole breast radiotherapy. More extensive procedures were categorized as mastectomies, of which modified radical mastectomy was used most commonly.

In all centres, surgical management included at least a level II axillary dissection, or sentinel node biopsy with or without systemic adjuvant treatment as indicated by the respective national guidelines. Women undergoing mastectomy who had positive surgical margins were treated with adjuvant radiotherapy.

Study variables

Demographic variables included age at diagnosis, self‐reported ethnicity (Chinese, Malay, Indian) and country (Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore). Data on tumour characteristics included size, number of positive axillary lymph nodes, grade based on the Bloom–Scarff–Richardson classification (low, moderate, high), oestrogen receptor status (positive, negative), progesterone receptor status (positive, negative), human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) 2 status (overexpressed, not expressed, equivocal) and lymphovascular invasion (LVI; present, absent). Data on receipt of adjuvant therapy included chemotherapy and hormone therapy administration.

Follow‐up and outcome assessment

The main outcome in this study was all‐cause mortality, verified using the respective national mortality registries in Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong. As data on disease recurrence were incomplete, this outcome was not included. Duration of follow‐up was calculated from the date of breast cancer diagnosis to the date of death, or censored at the end of follow‐up.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were described using proportions and compared with the χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as median values and compared with the Mann–Whitney U test. Time trends for type of surgery were analysed in overall patients, followed by age at diagnosis (less than 40 years, 40–49 years) and country. Overall survival (OS) was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analyses.

Propensity scoring was used to balance demographic, tumour and treatment characteristics, between mastectomy and BCS groups. The propensity score for BCS was defined as the predicted probability for a patient to undergo BCS given her demographic, tumour and adjuvant treatment characteristics15. As the probability of receiving BCS in clinical practice depends on surgeon and patient decisions, variables that were most likely to influence this decision and associated with OS were considered, including age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis, ethnicity, country, tumour size, hormonal receptor status, HER2 status, tumour grade, LVI and subsequent adjuvant treatment plan (chemotherapy, hormone therapy). These variables were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model as predictors with BCS as the outcome. From this model, the expected probability of undergoing BCS for each patient given her clinical variables (propensity score) was determined.

Cox regression analysis was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) for mortality in patients receiving BCS versus mastectomy. The model was subsequently stratified by propensity score in 20 quantiles to ensure that, within each stratum, comparisons of mortality were made between women with a similar expected probability of undergoing BCS and (mostly) similar distributions of confounders. The resulting HR was therefore an adjusted estimate of the effect of BCS on all‐cause mortality following breast cancer, compared with mastectomy.

Cox regression analyses stratified by age at diagnosis (less than 40 years, 40–49 years) and country (Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong) were also performed. Subgroup analyses within patients with node‐negative disease (T1–2 N0 M0 tumours)11 and triple‐negative breast cancers (TNBC) were also undertaken16.

Sensitivity analyses were performed in which patients undergoing postmastectomy radiotherapy were excluded. Additionally, the Cox regression models were adjusted for propensity score as a continuous variable instead of being stratified.

The multiple imputation method was used to account for missing values (ranging between 5 and 30 per cent). All the previously mentioned demographic, tumour and treatment variables were included in the imputation model, and ten imputation sets were created17.

Two‐tailed P values of less than 0·050, and 95 per cent confidence interval for HRs that did not include 1, were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS® statistics software version 21 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

This cohort study included 3536 women aged 20–49 years, representing 44·4 per cent of the 7967 patients with stage I or II breast cancer managed in the study centres between 1992 and 2011. Overall, 2245 women (63·5 per cent) had undergone mastectomy, and 1291 (36·5 per cent) had BCS. The median age at diagnosis was 44 years (Table 1). The majority of patients were Chinese, followed by Malays, Indians and other ethnic groups. The median tumour size at presentation was 2·0 cm.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological characteristics and treatment pattern of young Asian women with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer by type of surgery

| Type of surgery | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 3536) | Mastectomy (n = 2245) | BCS (n = 1291) | P § | Adjusted odds ratio†, # | |

| Country | < 0·001 | ||||

| Malaysia | 1278 (36·1) | 792 (35·3) | 486 (37·6) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Singapore | 1035 (29·3) | 605 (26·9) | 430 (33·3) | 1·26 (1·04, 1·52) | |

| Hong Kong | 1223 (34·6) | 848 (37·8) | 375 (29·0) | 0·62 (0·50, 0·76) | |

| Age (years)* | 44 (39,47) | 44 (40,47) | 43 (39,46) | < 0·001¶ | 0·96 (0·95, 0·98) |

| Calendar year of diagnosis | – | – | – | 1·02 (1·01, 1·04) | |

| Ethnicity | < 0·001 | ||||

| Chinese | 2479 (70·1) | 1578 (70·3) | 901 (69·8) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Malay | 381 (10·8) | 199 (8·9) | 182 (14·1) | 1·87 (1·47, 2·39) | |

| Indian | 168 (4·8) | 111 (4·9) | 57 (4·4) | 1·01 (0·71, 1·45) | |

| Other/unknown | 508 (14·4) | 357 (15·9) | 151 (11·7) | 0·89 (0·70, 1·12) | |

| Tumour size (cm)* (n = 3184) | 2·0 (1·4,3·0) | 2·3 (1·5,3·5) | 1·8 (1·2,2·4) | < 0·001¶ | 0·64 (0·60, 0·69) |

| Tumour grade | 0·010 | ||||

| Well differentiated | 504 (16·7) | 281 (15·0) | 223 (19·4) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 1359 (45·1) | 859 (46·0) | 500 (43·6) | 0·90 (0·71, 1·13) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 1152 (38·2) | 728 (39·0) | 424 (37·0) | 1·12 (0·87, 1·45) | |

| Unknown | 521 | 377 | 144 | ||

| Axillary node status | < 0·001 | ||||

| Not involved | 2499 (72·4) | 1518 (69·5) | 981 (77·5) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Involved | 952 (27·6) | 667 (30·5) | 285 (22·5) | 0·85 (0·71, 1·03) | |

| Unknown | 85 | 60 | 25 | ||

| ER status | < 0·001 | ||||

| Negative | 1121 (34·6) | 743 (36·7) | 378 (31·0) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Positive | 2123 (65·4) | 1280 (63·3) | 843 (69·0) | 1·31 (1·00, 1·71) | |

| Unknown | 292 | 222 | 70 | ||

| PR status | 0·040 | ||||

| Negative | 1161 (38·0) | 753 (39·4) | 408 (35·6) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Positive | 1896 (62·0) | 1159 (60·6) | 737 (64·4) | 0·90 (0·70, 1·16) | |

| Unknown | 479 | 333 | 146 | ||

| HER2 status | < 0·001 | ||||

| Negative | 1884 (75·7) | 1131 (73·1) | 753 (80·1) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Positive | 604 (24·3) | 417 (26·9) | 187 (19·9) | 0·69 (0·56, 0·86) | |

| Unknown | 1048 | 697 | 351 | ||

| LVI | < 0·001 | ||||

| No | 1710 (60·8) | 1037 (57·3) | 673 (67·1) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1104 (39·2) | 774 (42·7) | 330 (32·9) | 0·66 (0·55, 0·80) | |

| Unknown | 722 | 434 | 288 | ||

| Chemotherapy | < 0·001 | ||||

| No | 1153 (33·4) | 657 (30·3) | 496 (38·7) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 2299 (66·6) | 1514 (69·7) | 785 (61·3) | 0·91 (0·76, 1·10) | |

| Unknown | 84 | 74 | 10 | ||

| Hormonal therapy‡ | 0·450 | ||||

| No | 235 (11·4) | 146 (11·9) | 89 (10·8) | 1·00 (reference) | |

| Yes | 1823 (88·6) | 1086 (88·1) | 737 (89·2) | 0·91 (0·72, 1·15) | |

| Unknown | 65 | 48 | 17 | ||

Values in parentheses are percentages unless indicated otherwise;

values are median (i.q.r.);

values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Included only patients with oestrogen receptor (ER)‐positive tumours. BCS, breast‐conserving surgery; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; PR, progesterone receptor; LVI, lymphovascular invasion.

χ2 test, except

Mann–Whitney U test.

Derived using multivariable logistic regression analysis with BCS as outcome; all listed characteristics in the table were entered into the model; missing data were treated with multiple imputation.

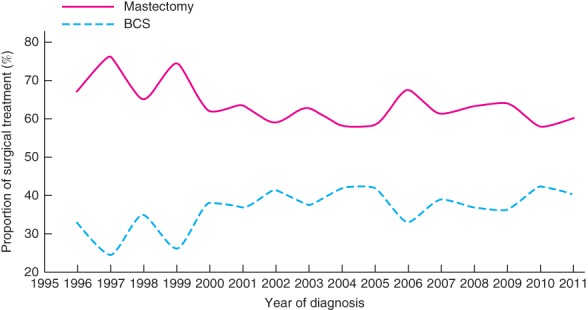

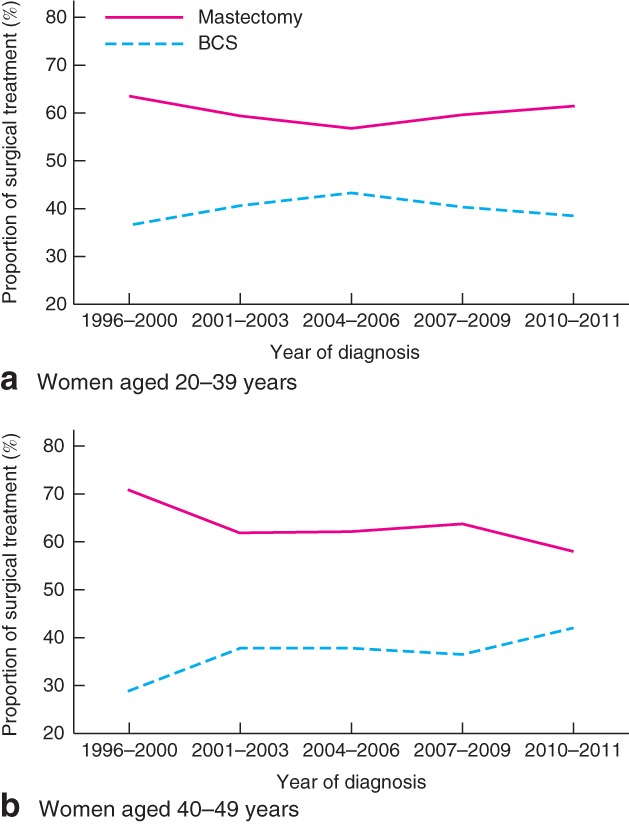

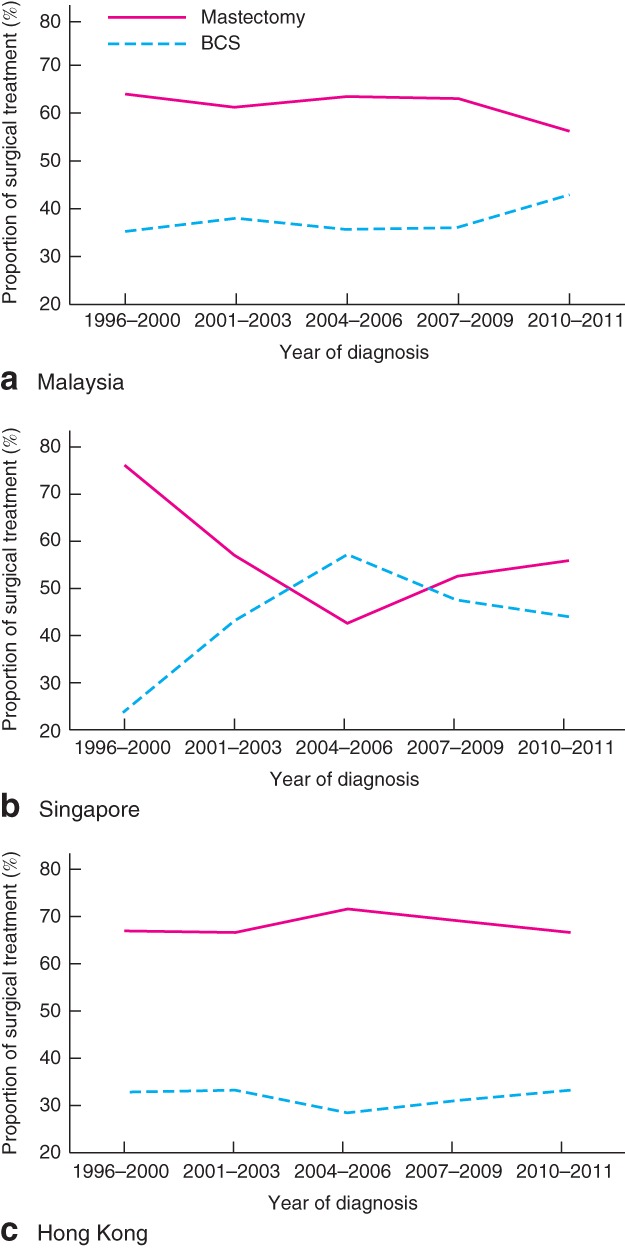

The proportion of patients who underwent BCS increased slightly, from 33·0 per cent in 1996 to 40·1 per cent in 2011 (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, the overall mastectomy rate (63·5 per cent) remained higher compared with BCS (36·5 per cent). Surgical trends in very young women with breast cancer (20–39 years old) remained unchanged between 1996 and 2011, whereas a moderate increase in BCS rates was observed from 1996 to 2011 in women aged 40–49 years (Fig. 2). Throughout the study interval, a slight increase in BCS was observed in Malaysia (Fig. 3 a). Although the overall rates of BCS appeared to have increased by 20·4 per cent in Singapore, a reversal in surgical trends was observed after the mid‐2000s, when mastectomy rates began to increase (Fig. 3 b). No change in the rate of BCS was observed throughout the study period in Hong Kong (Fig. 3 c).

Figure 1.

Trends in the surgical management of young women with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer in Asian settings, 1996–2011. BCS, breast‐conserving surgery

Figure 2.

Trends in surgical management of young women with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer in Asian settings by age at diagnosis: a 20–39 years; b 40–49 years. BCS, breast‐conserving surgery

Figure 3.

Trends in surgical management of young women with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer in Asian settings by country: a Malaysia; b Singapore; c Hong Kong. BCS, breast‐conserving surgery

Malay patients were more likely to receive BCS compared with Chinese (odds ratio 1·87, 95 per cent c.i. 1·47 to 2·39) and Indian women (Table 1). Compared with mastectomy, BCS was significantly associated with favourable prognostic features, including smaller tumours, absence of lymph node involvement, low‐grade tumours, hormonal receptor positivity and absence of LVI. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, younger age at diagnosis, country, Malay ethnicity and smaller tumour size were independently associated with BCS. Overexpression of HER2 and presence of LVI were inversely associated with BCS (Table 1).

The multivariable logistic regression model constructed to estimate the propensity score was able to predict BCS correctly in approximately 85 per cent of the patients. The distribution of type of surgery across the 20 quantiles of propensity score is shown in Table S1 (supporting information).

Survival

A total of 393 deaths were observed in the 3536 women over a median follow‐up of 7·13 years. There was no difference in OS between patients who had BCS and those undergoing mastectomy. The 5‐year OS rate was 94·9 (95 per cent c.i. 93·5 to 96·3) per cent in women receiving BCS, and 92·9 (91·7 to 94·1) per cent among those having a mastectomy (Table 2). The corresponding 10‐year OS rate was 87·0 (84·5 to 89·6) and 84·8 (84·6 to 85·0) per cent respectively (data not shown). Mastectomy was not associated with a lower risk of mortality compared with BCS in the unadjusted Cox regression analyses. Inferences remained unchanged following stratification by propensity score in 20 quantiles: adjusted HR 0·81 (0·64 to 1·03) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between type of surgery and overall survival of young Asian women with stage I or II (T1–2 N0–1 M0) breast cancer

| No. of women | 5‐year OS (%) | Crude HR | Adjusted HR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall cohort | 3536 | |||

| Mastectomy | 2245 | 92·9 (91·7, 94·1) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 1291 | 94·9 (93·5, 96·3) | 0·80(0·64, 1·02) | 0·81 (0·64, 1·03)* |

| Subgroups | ||||

| Age at diagnosis 20–39 years | 911 | |||

| Mastectomy | 556 | 90·0 (87·3, 92·7) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 355 | 91·4 (87·9, 94·9) | 0·80 (0·55, 1·17) | 0·80 (0·52, 1·21)* |

| Age at diagnosis 40–49 years | 2625 | |||

| Mastectomy | 1689 | 93·8 (92·4, 95·2) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 936 | 96·2 (94·8, 97·6) | 0·79 (0·60, 1·03) | 0·82 (0·61, 1·10)* |

| Malaysia | 1278 | |||

| Mastectomy | 792 | 86·8 (84·1, 89·5) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 486 | 90·7 (87·4, 94·0) | 0·88 (0·66, 1·17) | 0·97 (0·69, 1·36)* |

| Singapore | 1035 | |||

| Mastectomy | 605 | 93·1 (90·9, 95·3) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 430 | 95·0 (92·8‐97·2) | 0·71(0·48, 1·07) | 0·78 (0·50, 1·20)* |

| Hong Kong | 1223 | |||

| Mastectomy | 848 | 98·0 (97·0, 99·0) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 375 | 99·6 (98·8, 100) | 0·47 (0·25, 0·89) | 0·47 (0·23, 0·95)* |

| T1–2 N0 M0 tumours | 2499 | |||

| Mastectomy | 1518 | 94·5 (93·1, 95·9) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 981 | 95·6 (94·0, 97·2) | 0·90 (0·67, 1·21) | 0·90 (0·67, 1·22)* |

| Triple‐negative breast cancer | 402 | |||

| Mastectomy | 232 | 85·3 (80·0, 90·6) | 1·00 (reference) | 1·00 (reference) |

| BCS | 170 | 94·0 (90·1, 97·9) | 0·61 (0·30, 1·24) | 0·55 (0·27, 1·13)† |

Values in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals. OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio; BCS, breast‐conserving surgery. Cox regression analysis stratified by propensity score

20 quantiles and

deciles (estimated using country, age at diagnosis (continuous), year of diagnosis (continuous), ethnicity, tumour size (continuous), tumour grade, number of positive lymph node, oestrogen receptor status, progesterone receptor status, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status, lymphovascular invasion, chemotherapy status, hormonal therapy status).

Subgroup analysis by age at diagnosis in patients with T1–2 N0 M0 tumours also revealed that type of surgery was not significantly associated with survival outcomes in young women with breast cancer (Table 2). Nonetheless, BCS was associated with a survival gain compared with mastectomy in women from Hong Kong (adjusted HR 0·47, 95 per cent c.i. 0·23 to 0·95), but not among patients from Malaysia or Singapore. BCS also appeared to be associated with a survival advantage in young women with TNBC, although not significantly so (adjusted HR 0·55, 0·27 to 1·13) (Table 2).

Results remained largely unchanged following sensitivity analysis that excluded 833 women who received postmastectomy radiotherapy, except in country‐specific analysis where it was noted that BCS was associated with a lower risk of mortality compared with mastectomy (adjusted HR 0·42, 95 per cent c.i. 0·19 to 0·93) in Singapore. Analysis where the propensity score was adjusted as a co‐variable in the Cox regression model did not change the study inferences.

Discussion

Although the present study documented a modest increase in the rates of BCS among young Asian women with early breast cancer, marked regional variation was observed. The highest rate of BCS was observed in Singapore, and the lowest rate in Hong Kong. Although Singapore adopted the recommendation of the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference in 1990, as evidenced by a 20·4 per cent increase in BCS between 1996 and 2011, in Hong Kong only one in every three women with early‐stage breast cancer received BCS and, more strikingly, the low use of BCS remained unchanged throughout the study period. This may reflect cultural attitudes, as removal of the entire breast may be perceived as reducing the risk of leaving residual lesions and completely getting rid of breast cancer among the Chinese patients18 19. The relatively small breast size of Chinese women might also make BCS a less suitable option20. It should, however, be noted that a previous study in Hong Kong21 showed that BCS was associated with better body image scores and psychosocial outcomes compared with mastectomy.

Financial and logistical barriers may also influence surgical decision‐making, as patients undergoing BCS may have to commute to hospital more often to complete adjuvant radiotherapy, incurring additional expenses and time. This may be problematic for Asian women from low socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as those living in rural areas or unable to take time off from work22 23. As Malaysia, Singapore and Hong Kong offer universal health coverage, where adjuvant radiotherapy is provided as part of routine care in early‐stage breast cancer, lack of access to radiotherapy should have had little impact in the present study.

The present finding, that there is no difference in OS following mastectomy or BCS in young women with early‐stage breast cancer in Asian settings, is consistent with a meta‐analysis10 that included 22 598 women aged 40 years or less from five population‐based studies and two clinical trials comparing BCS with mastectomy (pooled HR 0·90, 95 per cent c.i. 0·81 to 1·00). Subgroup analyses among women with T1–2 N0 M0 tumours in the present study, however, failed to demonstrate any survival differences between patients undergoing BCS and those having a mastectomy, unlike a previous Danish study11. The higher risk of recurrence and mortality associated with BCS compared with mastectomy alone in the Danish study may be explained by the fact that it included patients treated more than two decades previously (between 1989 and 1998).

From the patient's perspective, BCS may be associated with substantial advantages compared with mastectomy, as it helps to maintain or restore quality of life, preserves self‐image, and positively impacts on sexuality24. Although mastectomy plus reconstruction in appropriate candidates may also be helpful in preserving quality of life and maintaining marital and social relationships25, a recent study26 has shown that mastectomy followed by reconstruction is associated with an almost twofold increased risk of complications including infection, seroma, breast pain and fat necrosis, along with higher costs, compared with BCS in women with early breast cancer.

This study suffers from several limitations, particularly the lack of data on local recurrence. The follow‐up interval was relatively short compared with the 20‐year follow‐up in the Danish cohort study11. Even though the present study was not population‐based, its multi‐institutional nature and inclusion of women with various ethnicities may be considered representative of the Asian experience. Given the observational nature of the study, propensity score analysis was used to control for non‐random treatment assignment of patients by balancing the inherent differences in prognostic features between the two surgical groups. Although the propensity score method was able to account for the measured confounders, residual confounding from unmeasured factors, including socioeconomic status, may still pose a threat to the validity of the present findings. It is also acknowledged that in the lower and upper quantiles of the propensity scores, the numbers of women having BCS or mastectomy were unbalanced. Sensitivity analysis adjusting for propensity score as a co‐variable, however, did not change the main inferences.

Supporting information

Table S1 Distribution of type of surgery by 20 quantiles of propensity score

Acknowledgements

S.S. was supported financially by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia (High Impact Research Grant: UM.C/HIR/MOHE/06).

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Bhoo‐Pathy N, Subramaniam S, Taib NA, Hartman M, Alias Z, Tan GH et al Spectrum of very early breast cancer in a setting without organised screening. Br J Cancer 2014; 110: 2187–2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Recio‐Saucedo A, Gerty S, Foster C, Eccles D, Cutress RI. Information requirements of young women with breast cancer treated with mastectomy or breast conserving surgery: a systematic review. Breast 2016; 25: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kummerow KL, Du L, Penson DF, Shyr Y, Hooks MA. Nationwide trends in mastectomy for early‐stage breast cancer. JAMA Surg 2015; 150: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia‐Etienne CA, Tomatis M, Heil J, Friedrichs K, Kreienberg R, Denk A et al; eusomaDB Working Group . Mastectomy trends for early‐stage breast cancer: a report from the EUSOMA multi‐institutional European database. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 1947–1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang B, Song Q, Zhang B, Tang Z, Xie X, Yang H et al A 10‐year (1999 ∼ 2008) retrospective multi‐center study of breast cancer surgical management in various geographic areas of China. Breast 2013; 22: 676–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deo SS, Mohanti BK, Shukla NK, Chawla S, Raina V, Julka PK et al Attitudes and treatment outcome of breast conservation therapy for stage I & II breast cancer using peroperative iridium‐192 implant boost to the tumour bed. Australas Radiol 2001; 45: 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Teo SY, Chuwa E, Latha S, Lew YL, Tan YY. Young breast cancer in a specialised breast unit in Singapore: clinical, radiological and pathological factors. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2014; 43: 79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Van Dongen JA, Bartelink H, Fentiman IS, Lerut T, Mignolet F, Olthuis G et al Randomized clinical trial to assess the value of breast‐conserving therapy in stage I and II breast cancer, EORTC 10801 trial. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 1992; 11: 15–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A et al Twenty‐year follow‐up of a randomized study comparing breast‐conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1227–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vila J, Gandini S, Gentilini O. Overall survival according to type of surgery in young (≤ 40 years) early breast cancer patients: a systematic meta‐analysis comparing breast‐conserving surgery versus mastectomy. Breast 2015; 24: 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laurberg T, Lyngholm CD, Christiansen P, Alsner J, Overgaard J. Long‐term age‐dependent failure pattern after breast‐conserving therapy or mastectomy among Danish lymph‐node‐negative breast cancer patients. Radiother Oncol 2016; 120: 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lim SE, Back M, Quek E, Iau P, Putti T, Wong JE. Clinical observations from a breast cancer registry in Asian women. World J Surg 2007; 31: 1387–1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pathy NB, Yip CH, Taib NA, Hartman M, Saxena N, Iau P et al; Singapore–Malaysia Breast Cancer Working Group . Breast cancer in a multi‐ethnic Asian setting: results from the Singapore–Malaysia hospital‐based breast cancer registry. Breast 2011; 20(Suppl 2): S75–S80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kwong A, Mang OW, Wong CH, Chau WW, Law SC; Hong Kong Breast Cancer Research Group . Breast cancer in Hong Kong, Southern China: the first population‐based analysis of epidemiological characteristics, stage‐specific, cancer‐specific, and disease‐free survival in breast cancer patients: 1997–2001. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 3072–3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. D'Agostino RB Jr. Propensity score methods for bias reduction in the comparison of a treatment to a non‐randomized control group. Stat Med 1998; 17: 2265–2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. O'Rorke MA, Murray LJ, Brand JS, Bhoo‐Pathy N. The value of adjuvant radiotherapy on survival and recurrence in triple‐negative breast cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 5507 patients. Cancer Treat Rev 2016; 47: 12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sterne JA, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG et al Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ 2009; 338: b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wong ST, Chen W, Bottorff JL, Hislop TG. Treatment decision making among Chinese women with DCIS. J Psychosoc Oncol 2008; 26: 53–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee MM. Breast cancer in Asian women. West J Med 2002; 176: 91–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yau TK, Soong IS, Sze H, Choi CW, Yeung MW, Ng WT et al Trends and patterns of breast conservation treatment in Hong Kong: 1994–2007. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009; 74: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fung KW, Lau Y, Fielding R, Or A, Yip AW. The impact of mastectomy, breast‐conserving treatment and immediate breast reconstruction on the quality of life of Chinese women. ANZ J Surg 2001; 71: 202–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang BL, Sivasubramaniam PG, Zhang Q, Wang J, Zhang B, Gao JD et al Trends in radical surgical treatment methods for breast malignancies in China: a multicenter 10‐year retrospective study. Oncologist 2015; 20: 1036–1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Leong BD, Chuah JA, Kumar VM, Rohamini S, Siti ZS, Yip CH. Trends of breast cancer treatment in Sabah, Malaysia: a problem with lack of awareness. Singapore Med J 2009; 50: 772–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lazovich D, Solomon CC, Thomas DB, Moe RE, White E. Breast conservation therapy in the United States following the 1990 National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference on the treatment of patients with early stage invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 1999; 86: 628–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dauplat J, Kwiatkowski F, Rouanet P, Delay E, Clough K, Verhaeghe JL et al; STIC‐RMI Working Group . Quality of life after mastectomy with or without immediate breast reconstruction. Br J Surg 2017; 104: 1197–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith BD, Jiang J, Shih YC, Giordano SH, Huo J, Jagsi R et al Cost and complications of local therapies for early‐stage breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016; 109 : pii: djw178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Distribution of type of surgery by 20 quantiles of propensity score