Analysis of plant natural product arabinosyltransferases identifies determinants of sugar donor specificity and suggests convergent evolution in monocots and eudicots.

Abstract

Glycosylation of small molecules is critical for numerous biological processes in plants, including hormone homeostasis, neutralization of xenobiotics, and synthesis and storage of specialized metabolites. Glycosylation of plant natural products is usually performed by uridine diphosphate-dependent glycosyltransferases (UGTs). Triterpene glycosides (saponins) are a large family of plant natural products that determine important agronomic traits such as disease resistance and flavor and have numerous pharmaceutical applications. Most characterized plant natural product UGTs are glucosyltransferases, and little is known about enzymes that add other sugars. Here we report the discovery and characterization of AsAAT1 (UGT99D1), which is required for biosynthesis of the antifungal saponin avenacin A-1 in oat (Avena strigosa). This enzyme adds l-Ara to the triterpene scaffold at the C-3 position, a modification critical for disease resistance. The only previously reported plant natural product arabinosyltransferase is a flavonoid arabinosyltransferase from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). We show that AsAAT1 has high specificity for UDP-β-l-arabinopyranose, identify two amino acids required for sugar donor specificity, and through targeted mutagenesis convert AsAAT1 into a glucosyltransferase. We further identify a second arabinosyltransferase potentially implicated in the biosynthesis of saponins that determine bitterness in soybean (Glycine max). Our investigations suggest independent evolution of UDP-Ara sugar donor specificity in arabinosyltransferases in monocots and eudicots.

INTRODUCTION

Plants produce a huge array of natural products, many of which are glycosylated (Vetter, 2000; Vincken et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2013). Glycosylation can play a major role in the structural diversification of secondary metabolites. For example, over 300 glycosides have been reported for the simple flavonol quercetin alone (Reuben et al., 2006). Glycosylation modifies the reactivity and solubility of the corresponding aglycones, so influences cellular localization and bioactivity (Augustin et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2013).

Plant natural products are decorated with a variety of different types of individual sugars and oligosaccharide chains. Studies involving various glycoconjugates of the same scaffold suggest that the identity of the sugar unit can have a major influence on bioactivity. For example, tests of six different monoglycosides of the sesquiterpene α-bisabolol against various cancerous cell lines for cytotoxicity revealed considerable variation in activity, with α-bisabolol rhamnoside being the most active (Piochon et al., 2009). Similarly, Bernard et al. (1997) showed that quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-[1,6]-β-d-galactopyranoside was five times less effective in stimulating topoisomerase IV-dependent DNA cleavage than quercetin 3-O-α-l-rhamnopyranosyl-[1,6]-β-d-glucopyranoside, the two flavones differing only in the nature of the sugar unit attached to the C-3 position.

Glycosylation of plant natural products is usually performed by uridine diphosphate-dependent glycosyltransferases (UGTs) belonging to the carbohydrate-active enzyme (CAZY) glycosyltransferase1 (GT1) family (Vogt and Jones, 2000; Bowles et al., 2006). These enzymes transfer sugars from uridine diphosphate-activated sugar moieties to small hydrophobic acceptor molecules. Over the last 15 years, considerable effort has been invested in the functional characterization of multiple UGTs from a variety of plant species. UGTs generally show high specificity for their sugar donors and recognize a single uridine diphosphate (UDP)-activated sugar as their substrate (Kubo et al., 2004; Bowles et al., 2006; Osmani et al., 2008; Noguchi et al., 2009). Plant UGTs recognize their sugar donors via a motif localized on the C-terminal part of the enzyme. This Plant Secondary Product Glycosyltransferase (PSPG) motif is highly conserved throughout UGT families (Hughes and Hughes, 1994; Mackenzie et al., 1997; ). Most characterized plant UGTs use UDP-α-d-glucose (UDP-Glc) as their sugar donor, although several UGTs that use alternative sugars have also been reported (Bowles et al., 2006; Osmani et al., 2009).

Triterpene glycosides (also known as saponins) are one of the largest and most structurally diverse groups of plant natural products. These compounds are synthesized from the isoprenoid precursor 2,3-oxidosqualene and share a common biogenic origin with sterols. They protect plants against pests and pathogens and can determine other agronomically important traits such as flavor. They also have a wide range of potential medicinal and industrial applications (Augustin et al., 2011; Sawai and Saito, 2011). Saponins commonly have a sugar chain attached at the C-3 position that may consist of up to five sugar molecules, and sometimes additional sugar chains located elsewhere on the molecule. These sugars are varied and diverse, including d-Glc, d-Gal, l-Ara, d-glucuronic acid, d-Xyl, l-Rha, d-Fuc, and d-apiose. Glycosylation is critical for many of the bioactive properties of these compounds (Osbourn, 1996; Francis et al., 2002).

Despite the importance of glycosylation for biological activity, characterization of triterpenoid UGTs has so far been limited. Of the 19 triterpenoid UGTs reported so far, 15 are d-glucosyltransferases. A further three hexose transferases have also been identified, transferring d-glucuronic acid, d-Gal, and l-Rha, respectively, and only one pentose (d-Xyl) transferase (Supplemental Table 1). The discovery of enzymes that are able to add other diverse sugars and investigation of the features that determine preference for different sugar donors will enable a wider array of triterpenoid glycoforms to be engineered. These advances, along with improved understanding of the significance of sugar chain composition for bioactivity, will open up new opportunities to fully exploit glycodiversification for agronomic, medicinal, and industrial biotechnology applications.

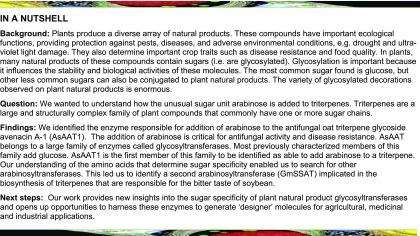

Previously we performed a forward screen for sodium azide-generated mutants of diploid oat (Avena strigosa) that are unable to synthesize triterpene glycosides known as avenacins (Figure 1A) (Papadopoulou et al., 1999). Avenacins are antimicrobial compounds that are produced in oat roots and that provide protection against soil-borne fungal pathogens, including the causal agent of Take-All disease of cereals, Gaeumannomyces graminis var tritici (Papadopoulou et al., 1999), a disease responsible for major yield losses in all wheat-growing areas of the world. The major avenacin found in oat roots is avenacin A-1. Previously we have characterized five of the genes in the avenacin pathway, which form part of a biosynthetic gene cluster (Haralampidis et al., 2001; Geisler et al., 2013; Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013). These include genes encoding enzymes for the biosynthesis and oxidation of the triterpene scaffold β-amyrin (AsbAS1/Sad1 and AsCYP51H10/Sad2, respectively; Haralampidis et al., 2001; Geisler et al., 2013), and for synthesis and addition of the UV-fluorescent N-methyl anthranilate acyl group at the C-21 position (AsMT1/Sad9, AsUGT74H5/Sad10, and AsSCPL1/Sad7; Figure 1C; Mugford et al., 2009; Owatworakit et al., 2013). Avenacin A-1 has a branched sugar chain at the C-3 position. This sugar chain is essential for antimicrobial activity, rendering the molecule amphipathic and so enabling it to disrupt fungal membranes (Osbourn et al., 1995; Armah et al., 1999). The first sugar in the sugar chain is l-Ara, which is linked to two d-Glc molecules via 1-2 and 1-4 linkages. The enzymes required for avenacin glycosylation have not yet been characterized. No triterpene arabinosyltransferase has as yet been identified, and the only plant natural product arabinosyltransferase known is a flavonoid arabinosyltransferase (UGT78D3) from Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Triterpene Glycoside Structures and Avenacin Biosynthesis.

(A) Avenacins: antifungal defense compounds from oat.

(B) Soyasaponin Ab, a triterpene glycoside associated with bitterness and anti-feedant activity in soybean.

(C) Current understanding of the avenacin biosynthetic pathway. The major avenacin, A-1, is synthesized from the linear isoprenoid precursor 2,3-oxidosqualene. 2,3-Oxidosqualene is cyclized by the triterpene synthase AsbAS1 (SAD1) to the pentacyclic triterpene scaffold β-amyrin (Haralampidis et al., 2001). β-Amyrin is then oxidized to EpHβA by the cytochrome P450 enzyme AsCYP51H10 (SAD2; Geisler et al., 2013). Subsequent, as-yet uncharacterized modifications involve a series of further oxygenations and addition of a branched trisaccharide moiety at the C-3 position, initiated by introduction of an l-Ara. Acylation at the C-21 position is performed by the AsSCPL1 (SAD7). The acyl donor used by AsSCPL1 is N-methyl anthranilate glucoside, which is generated by the methyl transferase AsMT1 and the glucosyl transferase AsUGT74H5 (SAD10; Mugford et al., 2009, 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013).

Here we report the discovery of AsAAT1 (UGT99D1), the enzyme that catalyzes the addition of the first sugar in the avenacin oligosaccharide chain. AsAAT1 is the first triterpene arabinosyltransferase to be characterized, and only the second reported plant GT1 arabinosyltransferase. We demonstrate that AsAAT1 shows high specificity for UDP-β-l-arabinopyranose (UDP-Ara) as its sugar donor and identify two amino acid residues mutually required for sugar donor specificity. We subsequently use this knowledge to identify a second triterpenoid arabinosyltransferase (GmSSAT1) implicated in the synthesis of triterpene glycosides that determine bitterness and anti-feedant activity in soybean (Glycine max). Although the oat AsAAT1, soybean GmSSAT1, and AtUGT78D3 enzymes are phylogenetically distinct, they all harbor the same signature His residue critical for arabinosylation activity, suggesting independent evolution of sugar donor specificity in plant natural product arabinosyltransferases in monocots and eudicots.

RESULTS

Identification of Candidate UGTs Expressed in Oat Root Tips

Avenacin A-1 is synthesized in the epidermal cells of oat root tips (Haralampidis et al., 2001; Mugford et al., 2009). To identify candidate UGTs implicated in avenacin biosynthesis, we mined an oat root tip transcriptome database that we generated previously (Kemen et al., 2014) using BLAST analysis (tBLASTn). The mRNA used to generate this transcriptome resource was extracted from the terminal 0.5 cm of the root tips of young oat seedlings, that is, from avenacin-producing tissues. Representative sequences for each of the 21 subfamilies of plant UGTs present in Arabidopsis were used as query sequences (Supplemental Table 2). The resulting hits were then assessed manually using alignment tools to eliminate redundant sequences. A total of ∼100 unique UGT-like sequences were identified, 36 of which were predicted to correspond to entire coding sequences (Supplemental Table 3).

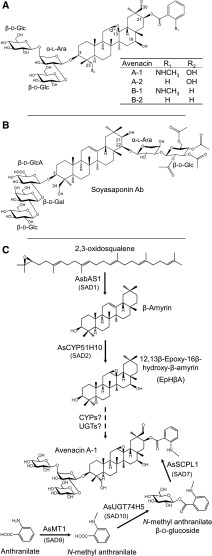

Phylogenetic analysis of the full-length UGT coding sequences was then performed (Figure 2A). Four sequences corresponding to the highly conserved sterol glycosyltransferase (UGT80) and monogalactosyldiacylglycerol synthase (UGT81) groups (Supplemental Table 3; Grille et al., 2010; Caputi et al., 2012) were omitted to avoid skewing the phylogeny reconstruction. The predicted amino acid sequences of the oat UGTs were aligned with those of characterized UGTs from other plants, including those previously reported to glycosylate triterpenoids (Supplemental Table 4 and Supplemental Data Set 1). The tree approximately recapitulated the monophyletic groups A-O previously defined by Li et al. (2001), but inclusion of the oat UGTs broadened the architecture to reveal oat-specific subfamilies. The oat UGTs (shown in red) were distributed across the phylogeny but were particularly well represented in groups D, E, and L. Of these, we have previously characterized three group L oat UGTs (AsUGT74H5/SAD10, AsUGT74H6, and AsUGT74H7) and shown that AsUGT74H5/SAD10 and AsUGT74H6 are required for the generation of the acyl Glc donors (N-methyl anthranilate β-d-Glc and benzoic acid β-d-Glc, respectively) used by the Ser carboxypeptidase-like acyltransferase AsSCPL1/SAD7 for biosynthesis of avenacins (Mugford et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013).

Figure 2.

Mining for Candidate Avenacin Glycosyltransferase Genes

(A) Phylogenetic tree of UGTs expressed in A. strigosa root tips (red;listed in Supplemental Table 3). Characterized triterpenoid glycosyltransferases from other plant species (blue) and other biochemically characterized plant UGTs (black) are also included (listed in Supplemental Table 4). The UGT groups are as defined by Ross, et al. (2001). Some of the most common groups of enzyme activities are indicated. The tree was constructed using the Neighbor Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates (% support for branch points shown). The scale bar indicates 0.1 substitutions per site at the amino acid level. The alignment file is available as Supplemental Data Set 1.

(B) Expression profiles of selected oat UGT genes (RT-PCR). Tissues were collected from 3-d-old A. strigosa seedlings. The characterized avenacin biosynthetic gene AsUGT74H5 (Sad10) and the GAPDH housekeeping gene are included as controls.

In parallel with our transcriptome-mining approach, we also performed proteomic analysis of the tips and elongation zones of oat roots (Supplemental Figure 1). The previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic enzyme AsUGT74H5 (SAD10; Owatworakit et al., 2013) showed higher accumulation in the root tips relative to the elongation zone. Of the 26 other UGT proteins detected in oat roots, three also accumulated at higher levels in the root tips compared with the elongation zone (AsUGT93B16, AsUGT99D1, and AsUGT706F7).

Eleven of the 19 triterpene UGTs that have previously been characterized from various plant species belong to UGT group D (Supplemental Table 1; Achnine et al., 2005; Meesapyodsuk et al., 2007; Naoumkina et al., 2010; Shibuya et al., 2010; Augustin et al., 2012; Sayama et al., 2012; Dai et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2015; Wei et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2016). We prioritized the six oat GTs from group D for gene expression analysis, along with the phylogenetically related enzyme AsUGT705A4, as well as AsUGT93B16 (group O) and AsUGT706F7 (group E), selected based on proteomic analysis. Six of these nine candidate genes had similar expression patterns to the characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes (AsUGT74H5/Sad10 is included as an example; Figure 2B). All nine candidate UGTs were taken forward for functional analysis (Table 1).

Table 1. Candidate Avenacin Glycosyltransferase Genes.

| A. strigosa UGT Genes | Group | Gene Expression Profilesa | Protein Level Ratio (RT/EZ)b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT | EZ | WR | L | |||

| AsUGT98B4 | D | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | ND in EZ |

| AsUGT701A5 | D | +++ | + | ++ | − | ND |

| AsUGT99C4 | D | ++ | − | + | − | ND in EZ |

| AsUGT99D1 | D | +++ | − | ++ | − | 2.30 |

| AsUGT99B9 | D | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | 0.78 |

| AsUGT99A6 | D | ++ | − | ++ | − | ND in RT |

| AsUGT705A4 | — | +++ | − | ++ | − | 0.77 |

| AsUGT706F7 | E | +++ | + | ++ | + | 1.34 |

| AsUGT93B16 | O | +++ | + | +++ | +++ | 1.70 |

| AsUGT74H5 | L | +++ | − | ++ | − | 5.56 |

RT, root tip; EZ, elongation zone; WR, whole root; L, leaves; ND, not detected. “—” indicates an absence of amplification; “+,” “++,” and “+++” indicate the relative intensity of the amplified fragment on the gel based on the housekeeping gene GAPDH.

Gene expression profiles were obtained by RT-PCR (Figure 2B).

Based on proteomic analysis (Supplemental Figure 1) and displayed as a ratio of protein detected between RT and EZ.

Heterologous Expression and In Vitro Activities of Candidate UGTs

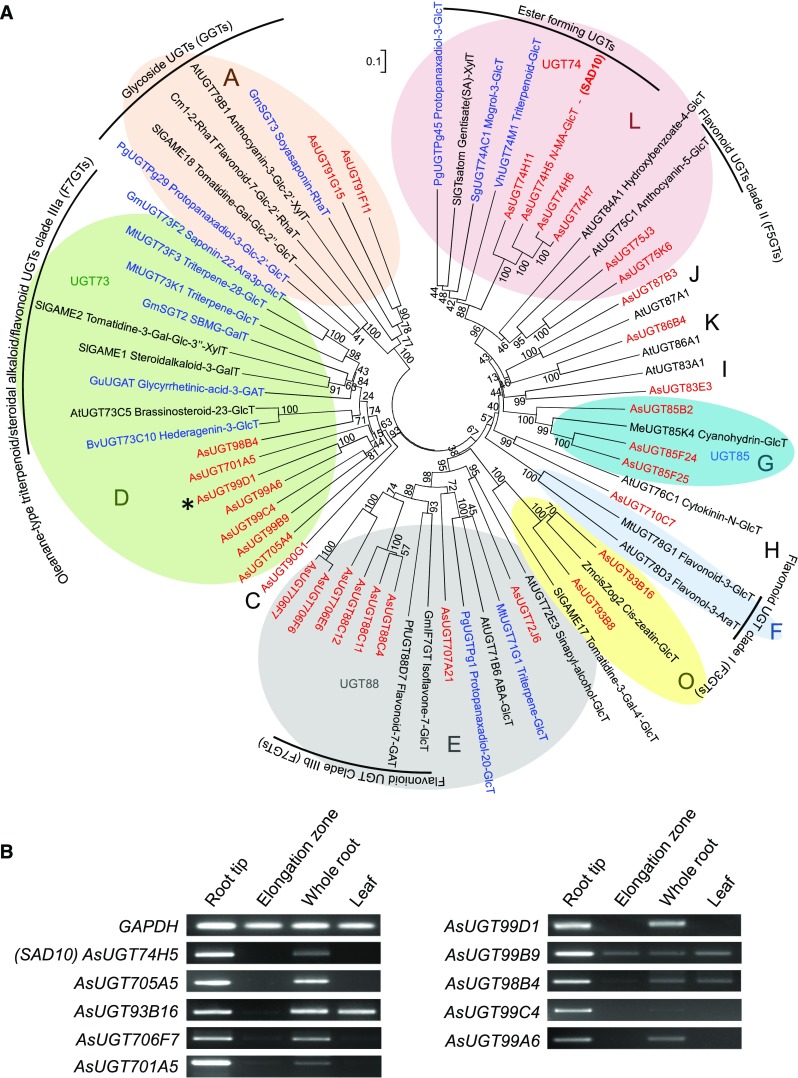

The coding sequences for the nine candidate genes were amplified from oat root tip cDNA (cDNA) and cloned into the expression vector pH9GW via the Gateway system (Hartley et al., 2000). The first sugar in the avenacin oligosaccharide chain is L-Ara (Figure 1). To investigate whether any of the candidate enzymes showed a preference for UDP-Ara as a sugar donor, the UGTs were expressed as recombinant N-terminal 9xhistidine-tagged proteins in Escherichia coli. Following lysis, protein preparations enriched for the recombinant enzymes were prepared using Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC; Supplemental Figure 2A). The resulting preparations were incubated with each of three different sugar donors (UDP-Glc, UDP-α-d-Gal [UDP-Gal], or UDP-Ara) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol (TCP). TCP was chosen as a universal acceptor in these assays because previous studies have shown that many UGTs are able to glycosylate TCP as well as their natural acceptor (Messner et al., 2003). The previously characterized Arabidopsis flavonoid arabinosyltransferase UGT78D3 (Yonekura-Sakakibara et al., 2008) and oat N-methyl anthranilate glucosyltransferase AsUGT74H5 (SAD10; Owatworakit et al., 2013) were included as controls. These two enzymes produced TCP arabinoside and TCP glucoside, respectively, as expected (Figure 3A). Of the nine candidate UGTs, only AsUGT99D1 showed a preference for UDP-Ara. This enzyme did not give any detectable product when UDP-Gal or UDP-Glc were supplied as potential sugar donors. The other UGTs showed a preference for UDP-Glc and so are likely to be glucosyltransferases (with the exception of AsUGT705A4, for which no activity was observed; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Biochemical Characterization of Candidate Oat UGTs

(A) Evaluation of sugar donor specificity of recombinant oat UGTs using the universal acceptor TCP. Relative activities with different sugar nucleotide donors are shown. Conversion of TCP to TCP glycoside was monitored by spectrophotometry at 405 nm. The previously characterized oat N-methyl anthranilate glucosyltransferase AsUGT74H5 (SAD10) and Arabidopsis flavonoid arabinosyltransferase UGT78D3 were included as controls. Values are means of three biological replicates; error bars represent sds.

(B) LC-MS profiles for avenacin A-1 (left), deglycosylated avenacin A-1 (middle), and the product generated by incubation of deglycosylated avenacin A-1 with AsUGT99D1 (right) (detection by fluorescence; excitation and emission wavelengths 353 nm and 441 nm, respectively). The hydrolyzed avenacin product is shown with an intact 12,13-epoxide (*), but this epoxide may have rearranged to a ketone under the acidic hydrolysis conditions resulting in deglycosylated 12-oxo-avenacin A-1, as observed in Geisler et al. (2013).

Incubation of the AsUGT99D1 enzyme preparation with the avenacin pathway intermediate 12,13β-epoxy-16β-hydroxy-β-amyrin (EpHβA) led to a new product when UDP-Ara was supplied as the sugar donor (Supplemental Figure 2B). Products were not detected with β-amyrin, suggesting that oxygenation of this scaffold is needed for AsUGT99D1 to act. When UDP-Glc was supplied as a potential sugar donor only a very small amount of conversion of EpHβA was observed, whereas no product was detected with UDP-Gal (Supplemental Figure 2B).

To further investigate the function of AsUGT99D1, we performed acid hydrolysis of purified avenacin A-1 to remove the C-3 trisaccharide. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis confirmed that the blue fluorescent hydrolysis product generated had a mass corresponding to deglycosylated avenacin (m/z [M+H]+ 638.1), with complete consumption of avenacin A-1 (m/z [M+H]+ 1094.1; Figure 3B, left and middle). After incubation of this hydrolysis product with recombinant AsUGT99D1 and UDP-Ara, a new fluorescent product was detected that had a mass consistent with addition of a pentose (m/z [M+H]+ 770.1; Figure 3B, right). These results suggest that AsUGT99D1 is able to initiate assembly of the sugar chain of avenacin A-1 by addition of l-Ara.

Transient Expression of AsUGT99D1 in Nicotiana benthamiana

Previously we have shown that Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of triterpene synthase and cytochrome P450 biosynthetic genes in N. benthamiana leaves enables rapid production of milligram to gram-scale amounts of simple and oxygenated triterpenes (Geisler et al., 2013; Mugford et al., 2013; Reed et al., 2017). We therefore used this expression system to carry out functional analysis of the candidate avenacin arabinosyltransferase enzyme AsUGT99D1 in planta. The AsUGT99D1 coding sequence was introduced into a Gateway-compatible pEAQ-Dest1 vector for coexpression with earlier enzymes in the avenacin pathway.

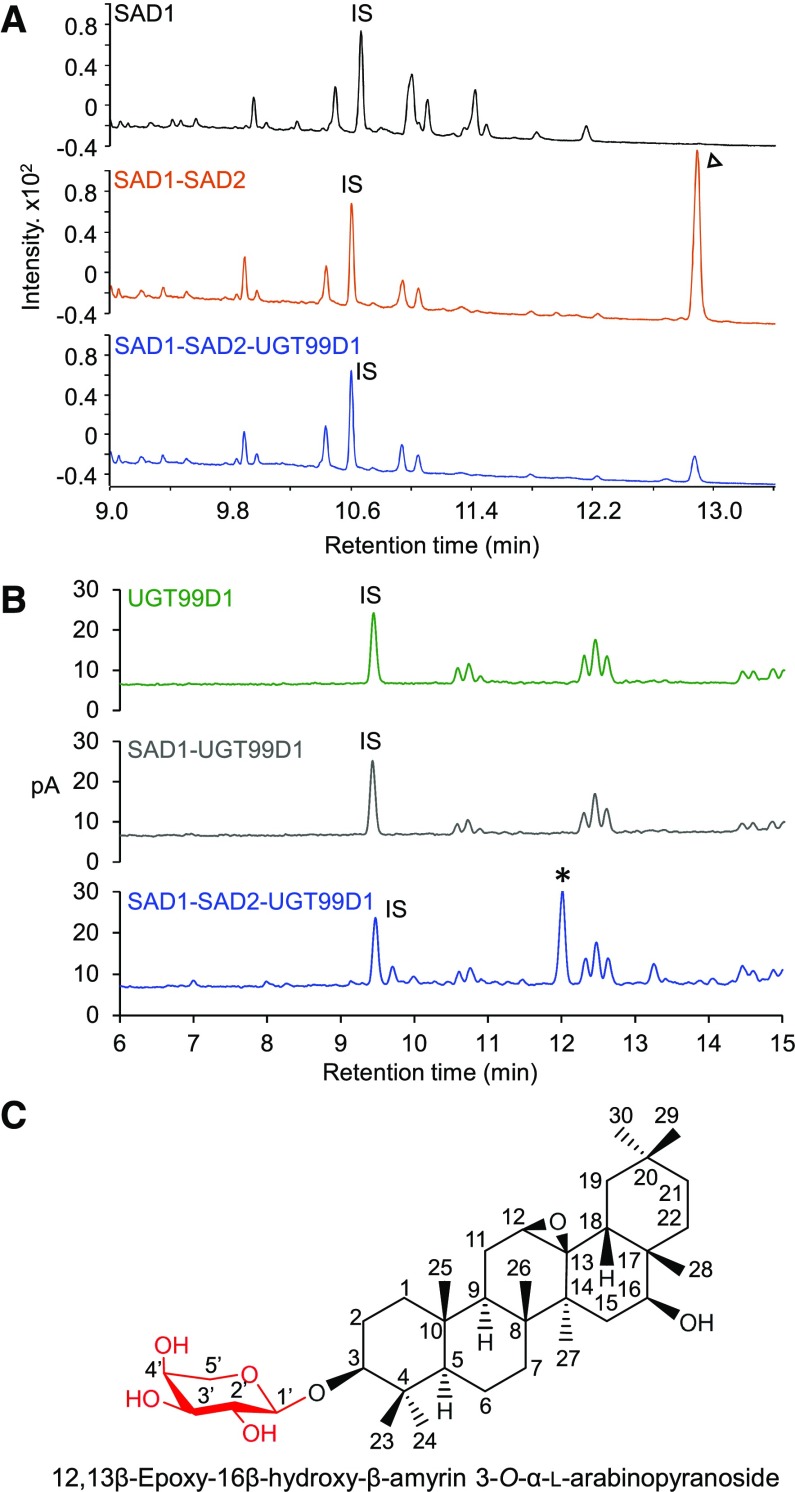

In accordance with previous work, coexpression of the first and second steps in the avenacin pathway (AsbAS1/SAD1 and AsCYP51H10/SAD2, respectively; hereafter referred to as “SAD1” and “SAD2”) yielded accumulation of the early avenacin pathway intermediate EpHβA, which was readily detectable by GC-MS (Figure 4A). By contrast, when SAD1 and SAD2 were coexpressed with AsUGT99D1, the levels of EpHβA were markedly reduced (Figure 4A) and a new, more polar product was detected by HPLC coupled to charged aerosol detector (CAD; Figure 4B). This new product was not present in extracts from leaves that had been infiltrated with the SAD1 and AsUGT99D1 expression constructs in the absence of SAD2 (Figure 4B). Furthermore, it had the same retention time (tR 12.0 min) as the product generated in vitro following incubation of EpHβA together with recombinant AsUGT99D1 (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Transient Expression of AsAAT1 in N. benthamiana

(A) GC-MS analysis of extracts from agro-infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves. Comparison of the metabolite profiles of leaves expressing SAD1 and SAD2 (red) or SAD1, SAD2, and UGT99D1 (blue). EpHβA, identified previously as the coexpression product of SAD1 and SAD2, is indicated by an arrowhead (Geisler et al., 2013). The upper chromatogram consists of a control from leaves expressing GFP only (black).

(B) HPLC with CAD chromatograms of extracts from N. benthamiana leaves expressing UGT99D1 alone (green), SAD1 and UGT99D1 (gray), and SAD1, SAD2, and UGT99D1 together (blue). The new compound that accumulated in the latter (tR 12.0 min) is indicated by an asterisk. This compound was not detected when UGT99D1 was expressed on its own or with SAD1. The IS was digitoxin (1 mg/g of dry weight).

(C) Structure of the UGT99D1 product (see Supplemental Figure 4 for NMR assignment).

To identify the product generated by coexpression of SAD1, SAD2, and AsUGT99D1 in N. benthamiana, we scaled up our transient expression experiments. Vacuum infiltration of 44 N. benthamiana plants was performed, and the freeze-dried leaf material extracted by pressurized solvent extraction. The triterpenoid product was purified using flash chromatography in normal and reverse phase mode. A total of 5.45 mg of product was obtained and estimated to be 94.5% pure using a CAD detector (corresponding to a yield of 0.79 mg/g dry weight) (Supplemental Figure 3). The structure of this product was analyzed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and the 1H and 13C NMR spectra fully assigned using a combination of COSY, DEPT-edited HSQC, and HMBC experiments (Supplemental Figure 4). The data are consistent with the structure being 16β-hydroxy-β-amyrin 3-O-α-l-arabinoside (Figure 4C). Importantly, an HMBC correlation was observed between the C-1′ hydrogen of the sugar moiety and the C-3 methine type carbon of the triterpene scaffold, confirming the site of glycosylation (Figure 4C, Supplemental Figure 4). Collectively, our data suggest that AsUGT99D1 is the missing avenacin arabinosyltransferase (hereafter named “AsAAT1”).

AsAAT1 Mutants of Oat Are Compromised in Avenacin Biosynthesis and Have Enhanced Susceptibility to Take-All Disease

Our collection of avenacin-deficient mutants of A. strigosa consists of ∼100 mutants, approximately half of which have been assigned to characterized loci (Papadopoulou et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2004, 2006; Mylona et al., 2008; Mugford et al., 2009, 2013; Qin et al., 2010; Geisler et al., 2013; Owatworakit et al., 2013). We sequenced the AsAAT1 gene in 47 uncharacterized avenacin-deficient mutants and identified a single line (#807) with a mutation in the AsAAT1 coding sequence. This mutation is predicted to give rise to a premature stop codon (Supplemental Figure 5A). Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis revealed that the levels of avenacin A-1 were substantially reduced in root extracts of this mutant (Supplemental Figure 5B). Subsequent analysis of seedlings of 139 F2 progeny derived from a cross between the wild-type A. strigosa parent and the mutant #807 line confirmed that the reduced avenacin phenotype cosegregated with the single nucleotide polymorphism in the AsAAT1 gene, and that the avenacin-deficient phenotype of mutant #807 is likely to be due to a recessive mutant allele of AsAAT1 (Supplemental Figure 5C; Table 2).

Table 2. Segregation Ratios for the F2 Progeny from Crosses Between #807 Mutant and A. Strigosa Wild Type.

| Chemotypesa | χ2 Wild Type: Mutant (3:1) | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Mutant | |

| 104 | 35 | 0.961 (P > 0.05) |

Chemotype analysis was performed by TLC-UV (Supplemental Figure 5C).

The previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic genes are physically clustered in the A. strigosa genome (Mugford et al., 2013). An accession of another avenacin-producing diploid oat species, Avena atlantica (IBERS Cc7277), has been the target of whole genome shotgun sequencing, with subsequent mapping of assembled contigs by survey resequencing of recombinant inbred progeny derived from a cross between this accession and A. strigosa accession Cc7651 (IBERS). A single ortholog of AsAAT1 contained on a contig of 14,086 bp was identified in the A. atlantica assembly (Supplemental Data Set 2). This contig is closely linked to the Sad2 locus, while the other eight UGT genes selected earlier are not (Supplemental Table 5). This suggests that AsAAT1 is likely to be part of the extended avenacin cluster. Future work will shed light on the full extent of the avenacin biosynthetic gene cluster and on the degree of conservation across different oat species.

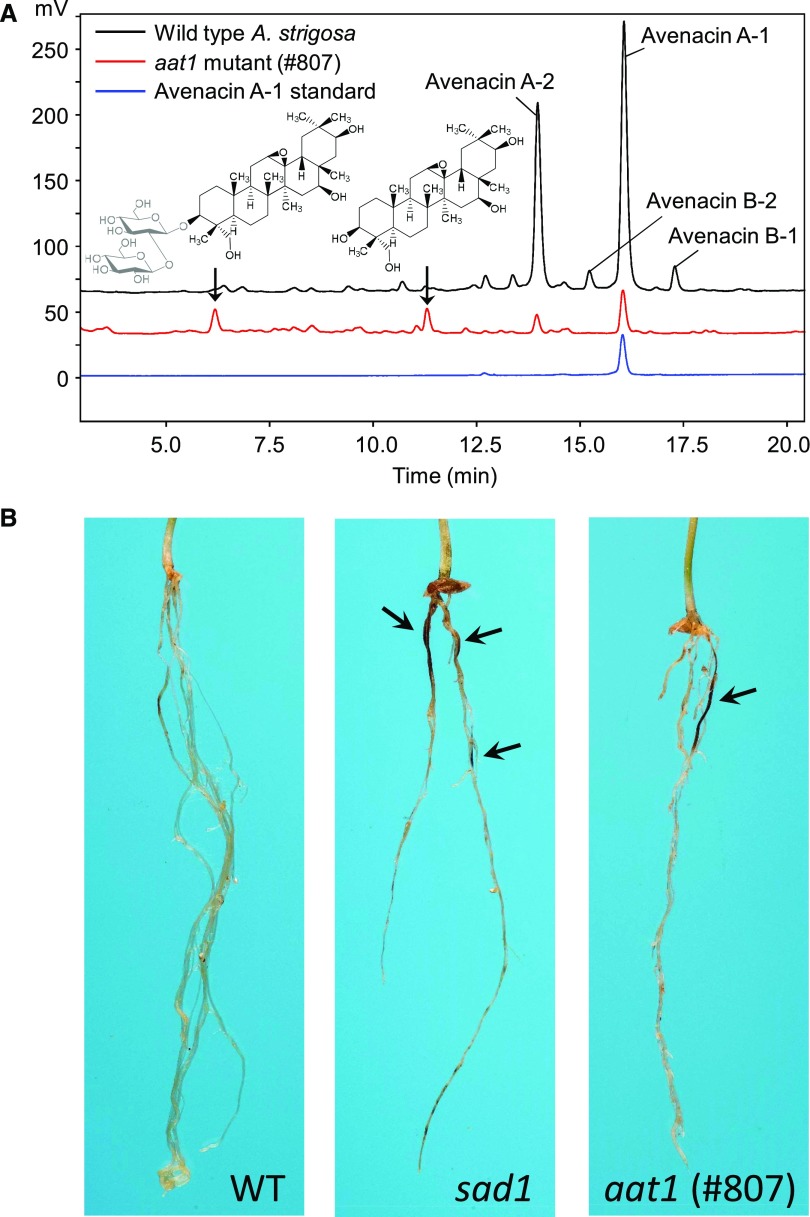

Avenacins A-1, B-1, A-2, and B-2 (Figure 1A) were readily detectable by HPLC analysis in extracts of wild-type oat roots (Figure 5A). By contrast, the levels of all four were markedly reduced in the aat1 mutant line #807, and two new smaller peaks of more polar compounds were observed (Figure 5A). Formate and chloride adducts (m/z 524.8 and 535.0, respectively; Supplemental Figure 5D, left) of the most apolar of these (tR 11.4 min) correspond to a compound with a molecular mass of 490 D. The apparent mass and polarity of this compound, as well as its lack of UV fluorescence, implies that aat1 accumulates the avenacin aglycone lacking the acyl group and the C-30 aldehyde. The other new peak (tR 6.3 min) has a molecular mass that corresponds to the first product plus two hexoses (814.5 D; Supplemental Figure 5D, right). A minor peak corresponding to the monoglucoside could also be detected at 7.7 min (652.4 D; Supplemental Figure 5D, center). These more polar products may be a result of further modification of the avenacin intermediate by non-specific glycosyltransferases in the absence of the functional AsAAT1 arabinosyltransferase. Low levels of avenacins were still detected, suggesting that other background enzymes may also be able to partially substitute for AsAAT1 in aat1 mutant lines.

Figure 5.

Biochemical Analysis of aat1 Mutant and Susceptibility to Take-All Disease.

(A) HPLC-CAD analysis of methanolic root extracts from seedlings of the A. strigosa wild-type accession and avenacin-deficient mutant line #807 (aat1). New metabolites detected in the mutant are arrowed and inferred structures are shown based on the corresponding ion chromatograms (Supplemental Figure 5D).

(B) aat1 (#807) has enhanced disease susceptibility. Images of representative seedlings of wild-type A. strigosa, the sad1 mutant #610 (Haralampidis et al., 2001), and the aat1 mutant (this study) are shown. Seedlings were inoculated with the take-all fungus (G. graminis var tritici). The dark lesions on the roots are symptoms of infection and are indicated by arrows.

F2 lines homozygous for the aat1 mutation did not have any obvious root phenotype other than reduced fluorescence, indicating that mutation of AsAAT1 is unlikely to affect root growth and development (Supplemental Figure 5C). Because glycosylation is known to be critical for the antifungal activity of avenacins, we investigated the effects of mutation at AsAAT1 on disease resistance. Disease tests revealed that the aat1 mutant had enhanced susceptibility to Take-All disease, consistent with a role for AsAAT1 in disease resistance (Figure 5B; Supplemental Figure 5E).

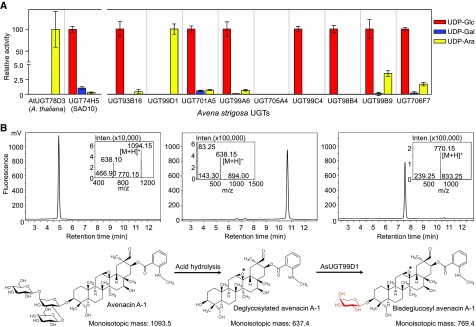

Prediction and Validation of a Soybean Arabinosyltransferase Based on Specific Features of AsAAT1

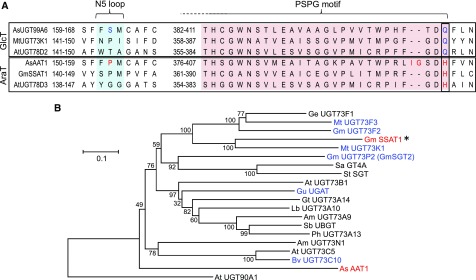

The most closely related UGT to AsAAT1 in oat is AsUGT99A6 (Figure 2A), which is a glucosyltransferase, based on our TCP assays (Figure 3A). In Arabidopsis the closest relative of AtUGT78D3 (AtUGT78D2) is also a glucosyltransferase (Tohge et al., 2005). Oat AsAAT1 and Arabidopsis AtUGT78D3 both have a His (H) residue at the C-terminal end of the PSPG motif, while their glucosyltransferase counterparts have Gln (Q) in this position (Figure 6A). This Gln residue has been shown to be involved in sugar donor selectivity and is highly conserved in many plant UGTs (Kubo et al., 2004; Gachon et al., 2005; Caputi et al., 2008). Replacement of the His residue in AtUGT78D3 with Gln has previously been shown to result in gain of ability to recognize UDP-Xyl and UDP-Glc and loss of ability to recognize UDP-Ara (Han et al., 2014). We therefore reasoned that the presence of a His residue in this position may be indicative of arabinosyltransferase activity.

Figure 6.

An Arabinosyltransferase from Soybean.

(A) Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the oat, soybean, and Arabidopsis arabinosyltransferases with the closest characterized glucosyltransferases in the region of the PSPG motif and the N5 loop. The His residue that is conserved in the arabinosyltransferases is shown in red. P154 and the two additional amino acids IG of AsAAT1 are also highlighted.

(B) Phylogenetic analysis of glycosyltransferases from group D belonging to the UGT73 family. GmSSAT1 and AsAAT1 are indicated in red, and other characterized triterpenoid glycosyltransferases in blue (see Supplemental Table 4 for further details). The tree was constructed using the Neighbor Joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates (percentage support shown at branch points), and rooted with UGT90A1, an Arabidopsis UGT from group C. The scale bar indicates 0.1 substitutions per site at the amino acid level. The alignment file is available as Supplemental Data Set 3.

Soybean produces triterpene glycosides known as soyasaponins. Group A soyasaponins have a branched sugar chain attached at the C-22 position initiated by an L-Ara residue (Figure 1B). The enzyme responsible for the addition of this L-Ara is not known. We mined the soybean genome (Grant et al., 2010) for candidate arabinosyltransferase genes by searching with a modified PSPG consensus motif containing a His residue at the critical position using tBLASTn. Six sequences were identified (Supplemental Table 6). Two of these belong to group D (Figure 6B). One of these—GmUGT73P2 (GmSGT2)—has previously been characterized as a soyasapogenol B 3-O-glucuronide galactosyltransferase (Shibuya et al., 2010). The other shares ∼53% amino acid sequence identity with the Medicago truncatula soyasaponin glucosyltransferase UGT73K1 (Supplemental Table 6; Achnine et al., 2005).

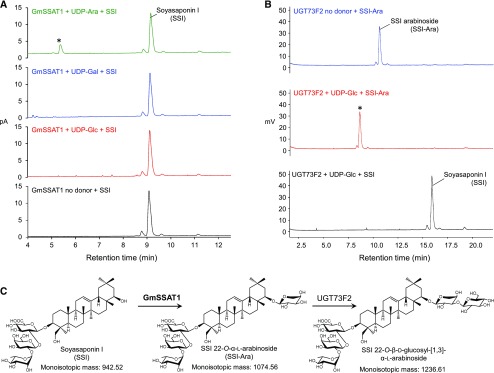

The coding sequence of this latter gene was synthesized commercially and cloned into the pH9-GW vector for expression in E. coli. Soluble recombinant N-term-9xHis-tagged enzyme was produced and enriched using Ni-NTA resin. The recombinant enzyme was incubated with soyasaponin I as an acceptor, together with each of three potential sugar donors, UDP-Glc, UDP-Gal, and UDP-Ara, and reaction products were analyzed by LC-CAD/MS. Only one major product was detected by CAD in the presence of UDP-Ara. This product was absent when UDP-Gal or UDP-Glc were supplied as sugar donors (Figure 7A). The mass of the new product (m/z 1073.5 by HR-MS) is consistent with arabinosylation (132.1 D) of soyasaponin I (941.2 D; Supplemental Figure 6A). We therefore named this enzyme “G. max SoyaSaponin ArabinosylTransferase1” (GmSSAT1).

Figure 7.

Biochemical Characterization of GmSSAT1.

(A) HPLC-CAD chromatogram of in vitro assays performed with recombinant GmSSAT1 and different UDP-sugars. GmSSAT1 was incubated for 40 min at 25°C with 100 μM SSI and 300 μM UDP-sugars. A major product is detected only in the presence of UDP-Ara (*) (see Supplemental Figure 7A for MS analysis).

(B) HPLC-CAD analysis of reactions in which the previously characterized soyasaponin glucosyltransferase UGT73F2 (Sayama et al., 2012) was assayed for activity toward the GmSSAT1 product. Recombinant UGT73F2 was incubated overnight with 400 μM UDP-Glc and ∼100 μM of the GmSSAT1 product SSI-Ara. SSI-Ara (tR: 10.6 min) was completely converted to a new product with a tR of 8.6 min (*). MS analysis of this product is shown in Supplemental Figure 7B. No product was detected in the absence of UDP-Glc or if the acceptor was replaced by SSI. C, Schematic showing successive glycosylation of soyasaponin I by GmSSAT1 and UGT73F2.

A UGT (GmUGT73F2) that extends the sugar chain at the C-22 position of soyasaponin by adding d-Glc to the l-Ara group has previously been discovered (Sayama et al., 2012). When recombinant GmUGT73F2 was incubated with UDP-Glc and the product of GmSSAT1, a new product was detected with a molecular mass corresponding to the glucoside of the former product (Figure 7B, Supplemental Figure 6B). GmUGT73F2 was inactive when incubated with UDP-Glc and soyasaponin I. Together, those results suggest that GmSSAT1 and GmUGT73F2 act consecutively in the initiation and extension of the sugar chain at the C-22 carbon position of group A soyasaponins (Figure 7C). GmSSAT1 is coexpressed with GmUGT73F2, most notably in the pods and pod shells where soyasaponins accumulate, suggesting a role for GmSSAT1 in the biosynthesis of these bitter compounds (Supplemental Figure 6C).

Site-Directed Mutagenesis of AsAAT1

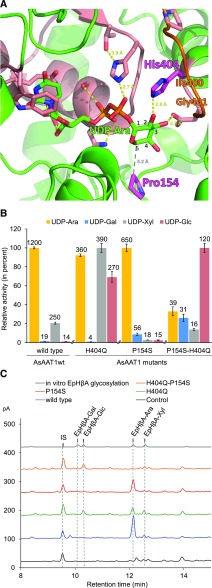

In addition to the His residue at the C-terminal end of the PSPG motif, a single amino acid difference was also observed between AsAAT1 (Pro) and AsUGT99A6 (Ser) in the middle of the N terminus loop positioned between the fifth β-strand and the fifth α-helix—the N5 loop, as defined by Osmani et al. (2009) (Figure 6A). The N5 loop has been shown to be involved in sugar specificity of the triterpene glucosyltransferase MtUGT71G1 from M. truncatula, soyasaponin glucosyltransferase GmUGT73F2 (mentioned earlier), and a flavonoid glucuronosyltransferase from Perilla frutescens (UGT88D7; Kubo et al., 2004; He et al., 2006; Noguchi et al., 2009). To further investigate the basis of AsAAT1 sugar donor preference, a homology model was generated using the online software I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015) and MODELER (Sali and Blundell, 1993) was used to refine the N-terminal loop of AsAAT1 PSPG motif. Docking of UDP-Ara into the sugar donor binding site of AsAAT1 was consistent with the arabinoside moiety of UDP-Ara having a hydrogen bond to His404 (bond length 2.8 Å) and a hydrophobic interaction with Pro154 (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

Determinants of Sugar Donor Sugar Specificity of AsAAT1.

(A) Model of AsAAT1 with bound UDP-Ara (carbons of the Ara numbered). The protein is represented in green ribbons with the PSPG motif in salmon, including the side chains of highly conserved residues. The His404 and Pro154 residues are shown in magenta. Potential hydrogen bonds are shown with yellow dots, and the distance between P154 and C-5 of UDP-Ara with gray dots. The homology model was generated using I-TASSER software (Yang et al., 2015), based on the crystal structure of M. truncatula UGT71G1 complexed with UDP-Glc (PDB: 2ACW). The loop shown in orange was reconstructed using MODELER (Sali and Blundell, 1993). UDP-Ara was inserted into the active site and the complex was relaxed by energy minimization using GROMACS.

(B) Comparison of the glycosylation activity of the AsAAT1 wild-type and mutant enzymes when supplied with each of the four sugar donors (UDP-Ara, UDP-Gal, UDP-Xyl, or UDP-Glc). Initial velocities were measured using 30 µM deglycosylated avenacin A-1 as acceptor and 5 µM UDP-sugar donor using five time points. The heights of the bars are drawn relative to the highest activity observed for each recombinant enzyme (mean ± sd, n = 3). Activities reported above each bar are in nM.min−1.

(C) HPLC-CAD analysis of extracts from N. benthamiana leaves expressing SAD1 and SAD2 together with GFP (black), wild-type AsAAT1 enzyme (blue), AsAAT1-H404Q (green), AsAAT1-P154S (red), and AsAAT1-H404Q-P154S (orange). The top trace (in gray) shows the products of in vitro reaction of EpHβA with the four sugar donors (reactions performed separately and then pooled) for reference. LC-MS analysis was used to confirm the identities of the new products (Supplemental Figure 8C). The IS is digitoxin (1 mg/g dry weight).

We performed site-directed mutagenesis of AsAAT1 to convert His404 and Pro154 to the corresponding residues found in the glucosyltransferase AsUGT99A6 (Gln and Ser, respectively). Purified N-terminal 9×His-tagged recombinant wild-type AsAAT1, the mutant forms H404Q and P154S, and the double mutant H404Q-P154S were assayed for their ability to glycosylate the avenacin aglycone (Supplemental Figure 7A). The AsAAT1-H404Q mutant had reduced arabinosyltransferase activity compared with the wild-type enzyme, and increased xylosyl- and glucosyltransferase activities; that is, showed greater promiscuity for different sugar donors (Figure 8B). When Pro154 was mutated to Ser, arabinosylation was still the predominant activity, but galactosyl transferase activity increased (Figure 8B). UDP-Gal was therefore a better donor for the P154S mutant variant than UDP-Xyl or UDP-Glc. The double mutant AsAAT1-H404Q-P154S preferred UDP-Glc over the three other sugar donors (Figure 8B); glucosyltransferase activity was ∼10-fold higher than that of wild-type AsAAT1, while arabinosyltransferase activity decreased markedly (∼30 fold).

The effects of the H404Q, P154S, and H404Q-P154S mutations on AsAAT1 sugar specificity were also examined in N. benthamiana by expressing wild-type AsAAT1 or the mutant variants with SAD1 and SAD2 and analyzing leaf extracts by HPLC-CAD (Figure 8C). These analyses were supported by LC-MS analysis of leaf extracts and in vitro reactions in which the wild-type and mutant AsAAT1 enzymes were incubated with different sugar nucleotide donors (Supplemental Figure 7C). HPLC-CAD analysis of extracts from leaves expressing wild-type AsAAT1 revealed the accumulation of EpHβA-Ara, as expected (Figure 8C). By contrast, the H404Q-P154S double mutant yielded EpHβA-Glc, confirming conversion of AsAAT1 to a glucosyltransferase (Figure 8C); no other EpHβA glycosides could be detected (Supplemental Figure 7C). Expression of the H404Q mutant yielded EpHβA-Ara, EpHβA-Glc, and traces of EpHβA-Xyl (Figure 8C; Supplemental Figure 7C), while P154S produced primarily EpHβA-Ara with traces of EpHβA-Gal and EpHβA-Glc (Figure 8C; Supplemental Figure 7C).

DISCUSSION

AsAAT1 Is Part of the Avenacin Pathway

Glycosylation has profound effects on the biological activities of natural products. UGTs belonging to the CAZY GT1 family are critical for small molecule glycosylation in plants. The trisaccharide moiety attached to the avenacin scaffold is essential for antifungal activity and hence disease resistance. Here we mine an oat root transcriptome database for candidate UGTs implicated in avenacin biosynthesis and report the discovery and characterization of the GT family 1 triterpenoid arabinosyltransferase AsAAT1. This enzyme initiates the addition of the avenacin oligosaccharide chain through addition of l-arabinopyranose at the C-3 position of the triterpene scaffold. Glycosylation of the avenacin scaffold is critical for antifungal activity (Mylona et al., 2008). Consistent with this, aat1 mutants of A. strigosa have enhanced susceptibility to G. graminis var tritici, the causal agent of the Take-All disease. Biochemical analysis suggests that the avenacin pathway intermediate that accumulates in the roots of aat1 mutants is deglycosyl-, desacyl-avenacin minus the C-30 aldehyde. This intermediate seems to be subject to further modification in the mutant background, including two successive glycosylation events. The apparent lack of the C-30 aldehyde in the intermediate coupled with in vitro assays with early intermediates of the pathway suggest that AsAAT1 requires β-amyrin oxidation and that arabinosylation is a prerequisite for C-30 oxidation. This places AsAAT1 somewhere between SAD2 and a hypothetical arabinoside glucosyltransferase or C-30 oxidase (Figure 1C). Most likely, arabinosylation catalyzed by AsAAT1 occurs in the cytosol after oxidation of the oleanane scaffold. C-30 oxidation and addition of the two d-Glc molecules to the C-3 l-Ara are then necessary before acylation in the vacuole byAsSCPL/SAD7 (Mugford et al., 2009).

Avenacins are still detectable in root extracts of the aat1 mutant albeit at considerably reduced levels, suggesting that another oat enzyme may be partially redundant with AsAAT1. Functional redundancy coupled with non-specific glucosylation of the aat1 intermediate (Figure 5A) may alleviate accumulation of toxic intermediates, preventing the severe root development phenotypes seen in other avenacin mutants affected in glucosylation (Mylona et al., 2008).

GmSSAT1, an Arabinosyltransferase Implicated in the Biosynthesis of Soyasaponins That Determine Bitterness in Soybean

In vitro assays performed with recombinant soybean UGTs suggest that GmSSAT1 and UGT73F2 are likely to act consecutively in initiation and extension of the sugar chain at the C-22 carbon position of group A saponins from soybean (Ab, Ac, Ad, Af, and Ah; Figure 7C). Both genes are coexpressed in soybean pods (Supplemental Figure 6C). The predicted natural acceptor of GmSSAT1 (non-acetylated non-arabinosylated soyasaponin A0-αg) is not commercially available, and the full function of this enzyme in soyasaponin biosynthesis remains to be elucidated. However, GmSSAT1 represents a potential target for plant breeding in endeavors to generate non-bitter soybean varieties. The arabinosyltransferase involved in soyasaponin biosynthesis adds the first sugar of the C-22 sugar chain present in group A saponins. The acetylated sugars attached via L-Ara at this position are thought to be responsible for the bitterness and astringent aftertaste of soybean (Sayama et al., 2012).

New Insights into Determinants of Sugar Donor Selectivity

The only other GT1 family arabinosyltransferase to have been characterized from plants before our work is the flavonoid arabinosyltransferase UGT78D3 from Arabidopsis. AsAAT1, GmSSAT1, and UGT78D3 all have a conserved His residue at the end of the PSPG signature motif, whereas their most closely related glycosyltransferase counterparts do not (Figure 6A). It is interesting to note that AsAAT1 and GmSSAT1 belong to different clades of group D (Figure 6B), while Arabidopsis UGT78D3 is in group F (Figure 2A), suggesting independent evolution of sugar donor specificity in GT1 arabinosyltransferases in monocots and eudicots. Through comparative analysis, protein modeling, and mutagenesis we have shown that this His residue (H404) is critical for sugar donor specificity in AsAAT1, and that mutation of H404 and P154 is sufficient to convert AsAAT1 from an arabinosyltransferase to a glucosyltransferase.

Molecular modeling suggests that P154 is in close proximity with the CH2 of the C-5 position of UDP-Ara (5.2 Å distance, Figure 8A). A potential steric constraint/hydrophobic interaction provided by the Pro may thus favor accommodation of pentoses while preventing accommodation of hexoses. Replacement of P154 by Ser could allow formation of a hydrogen bond with the C-6 hydroxyl group of hexoses, consistent with predictions from the crystal structure of the rice (Oryza sativa) UGT Os79, where a Ser in the equivalent position forms a H-bond with C-6 of Glc (Wetterhorn et al., 2016). Direct interaction of H404 with the C-4 hydroxy group of L-Ara is not suggested by the 3D model (Figure 8A). Nevertheless, the modified activity of the H404Q mutant is consistent with previous reports on plant glycosyltransferases (Kubo et al., 2004; Han et al., 2014) and suggests that H404 may modify the orientation of the hemiacetal ring, so indirectly impacting on selectivity for C-4 stereochemistry (see Supplemental Figure 7B for sugar stereochemistry).

AsAAT1 is also unusual in having a two-amino acid insertion (I400 and G401) toward the C-terminal part of the PSPG motif (Figure 6A). To our knowledge, this is a unique feature of AsAAT1. All plant UGTs characterized to date have a PSPG motif 44 amino acids long (see Supplemental Data Set 1 for large-scale alignment). However, we were unable to detect activity following either deletion of these two amino acids or replacement with the PSPG motif of AsUGT99A6. The 3D model of AsAAT1 suggests that those two residues may shape the region of the sugar donor binding pocket (Figure 8A). Those two residues could therefore also be involved in determining the sugar specificity of AsAAT1. The conformation of the loop from W396 to S402 was refined in MODELER (Sali and Blundell, 1993) to accommodate the presence of these two additional amino acids, and the six best-scoring conformations subjected to energy minimization to optimize the AsAAT1 model.

The gain of knowledge in molecular mechanisms underlying sugar specificity in UGTs provided by this work along with previous work on other GT1 enzymes opens up opportunities to identify candidate glycosyltransferases with particular sugar donor preferences based on sequence information, as we have demonstrated here through identification of the new arabinosyltransferase GmSSAT1. Similar approaches may prove useful to identify the swathe of as-yet uncharacterized enzymes involved in the assembly of complex sugar chains of saponins and other glycosides.

Harnessing Sugar Specificity Is Crucial for Glycodiversification

Glycosylation has profound effects on the biological activities, physical properties, and compartmentalization of natural products. The discovery of family 1 GTs that add different types of sugars to plant natural products will be key for understanding and harnessing natural product glycosylation. Here we report two arabinosyltransferases from the GT1 family: AsAAT1, a C-3 triterpenoid arabinosyltransferase from oat; and GmSSAT1, a C-22 triterpenoid arabinosyltransferase from soybean. Key residues for sugar donor specificity were identified via site-directed mutagenesis, allowing complete conversion of AsAAT1 from arabinosyltransferase to glucosyltransferase activity. This increased knowledge of the structural bases underlying sugar donor preference in family 1 GT enzymes can now be exploited to create new biocatalysts and enable unprecedented glycodiversification of natural products.

Of note, unlike yeast, the N. benthamiana transient expression platform is able to furnish an endogenous supply of UDP-Ara as well as UDP-Gal or UDP-Xyl, and so offers considerable potential as a system for glycodiversification of plant metabolites and small pharmaceuticals. Transient plant expression is demonstrably scalable and is currently used for production of pharmaceutical proteins by various companies (Sack et al., 2015). We have already used N. benthamiana transient expression to rapidly generate gram-scale quantities of triterpenoids in our lab (Reed et al., 2017). Given the potential for commercial scale-up, this platform has the potential to be a disruptive technology for metabolic engineering of triterpenes and potentially also other high-value chemicals.

METHODS

Plant Material

The wild-type Avena strigosa accession S75 and avenacin-deficient mutants were grown as described in Papadopoulou et al. (1999). Briefly, seeds of A. strigosa were surface-sterilized with 5% sodium hypochlorite and then germinated at 22°C, in 16 h of light on damp filter paper after synchronization at 4°C for 24 h in the dark. Nicotiana benthamiana plants were grown in green-houses maintained at 23°C to 25°C with 16 h of supplementary light per day, as described in Sainsbury et al. (2012).

RNA and cDNA Preparation

The cDNA used for amplification and subsequent cloning of the selected oat UGT genes and for gene expression analysis was generated from 3-d-old A. strigosa seedlings tissues. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen). First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed from 1 μg of DNase-treated RNA using SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen).

Phylogenetic Analysis

Representative amino acid sequences of characterized family 1 plant UGTs were collected from the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZy) database (http://www.cazy.org/). These sequences were augmented with sequences of characterized plant triterpenoid/steroidal UGTs. All sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 4. Deduced amino acid sequences derived from the predicted full-length A. strigosa UGT coding sequences (Supplemental Table 3) were incorporated into the phylogenetic reconstruction. Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/; Supplemental Data Set 1). The unrooted phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 5 (http://www.megasoftware.net/) by the neighbor-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Phylogenetic reconstruction of group D UGTs in Figure 5A was performed using the same method.

Proteomic Analysis

The tips and elongation zones of 5-d-old A. strigosa seedlings were harvested and ∼30 mg of material was ground in liquid N using a prechilled mortar and pestle. Protein extraction was performed following previously published methods (Owatworakit et al., 2013) and concentrations determined using the Bradford method (Bradford, 1976) with BSA (Sigma-Aldrich) as a standard. Samples (8 μg) were denatured at 95°C for 15 min in the presence of Nupage reducing agent (Invitrogen) and separated using a precast polyacrylamide gel (Nupage 4% to 12% Bis-TRIS; Invitrogen) in MOPS buffer (Invitrogen).

To increase the relative abundance of UGT proteins and simplify the sample mixture we performed on-gel size-fractionation of proteins, we took advantage of the conserved length of UGTs (AsUGTs molecular masses 48 kD to 55 kD). Proteins with molecular masses of 45 kD to 57 kD were excised from the SDS-PAGE gel with sterile razor blades. Gel slices were treated with DTT and iodoacetamide, and digested with trypsin according to standard procedures.

Peptides were extracted from the gels and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on an Orbitrap-Fusion mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano System using an Acclaim PepMap C18 column (2 µm, 75 µm × 500 mm; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Aliquots of the tryptic digests were loaded and trapped using a precolumn, which was then switched in-line to the analytical column for separation. Peptides were eluted with a gradient of 5% to 40% acetonitrile in water/0.1% formic acid at a rate of 0.5% min−1. The column was connected to a 10 µm SilicaTip nanospray emitter (New Objective) for infusion into the mass spectrometer. Data-dependent analysis was performed using parallel top speed HCD/CID fragmentation method with the following parameters: 3 s cycle time, positive ion mode, orbitrap MS resolution = 60 k, mass range (quadrupole) = 350 m/z to 1550 m/z, MS2 isolation window 1.6 D, charge states 2 to 5, threshold 3e4, AGC target 1e4, maximum injection time 150 ms, dynamic exclusion two counts within 10 s and 40 s exclusion, exclusion mass window ±7 ppm. MS scans were saved in profile mode while MS2 scans were saved in centroid mode.

Raw files from the orbitrap were processed with MaxQuant (version 1.5.5.1; http://maxquant.org; Tyanova et al., 2016). The searches were performed using the Andromeda search engine in MaxQuant on a custom database containing the Avena sequences available from the UniProt database augmented with the full complement of ∼100 unique UGT-like sequences identified from our oat root tip transcriptome database (Kemen et al., 2014) together with the MaxQuant contaminants database using trypsin/P with two missed cleavages, carbamidomethylation (C) as fixed and oxidation (M), acetylation (protein N terminus), and deamidation (N,Q) as variable modifications. Mass tolerances were 4.5 ppm for precursor ions and 0.5 D for fragment ions. Three biological replicates for each of the samples from root tips and the elongation zone were analyzed quantitatively in MaxQuant using the LFQ option.

Gene Expression Analysis

Expression of UGT genes was analyzed by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR). cDNA was generated from mRNA of 3-d-old seedlings for the whole root, root tip (terminal 0.2 cm of the root), root elongation zone (from 0.2 cm to the first root hair), and young leaves. Transcript levels of the housekeeping gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used to normalize the cDNA libraries over the four tissues. The previously characterized avenacin biosynthetic gene AsUGT74H5 (Sad10; Owatworakit et al., 2013) was included as a control. Gene-specific primers used for PCR amplification are listed in Supplemental Table 7.

Cloning of the AsUGT Coding Sequences

Gateway technology (Invitrogen) was used to make UGT expression constructs. The coding sequences (CDSs) including stop codons of A. strigosa UGTs were amplified by PCR with a two-step method from root tip cDNA. The first step consisted of specific amplification of full-length coding sequences with gene-specific primers harboring partial AttB adapters at their 5′ ends (see Supplemental Table 7 for primer sequences). The second step involved attachment of full AttB sites at each extremity of the CDS. Amplified fragments were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). Purified CDSs were then transferred into the pDONR207 vector using BP clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sequence-verified coding sequences were then transferred by the LR clonase II reaction into pH9GW (Invitrogen), a Gateway-compatible variant of pET-28 encoding nine N-terminal histidines (O’Maille et al., 2008).

Expression of Recombinant UGTs in Escherichia coli

The E. coli Rosetta 2 strain DE3 (Novagen) was transformed with the expression vectors following the manufacturer’s instructions. Selected transformants were cultured in liquid Lysogeny Broth media under kanamycin/chloramphenicol (100 μg/mL and 35 μg/mL, respectively) selection overnight at 37°C. Precultures were diluted 100-fold into fresh medium to initiate the cultures for induction. Production of recombinant enzymes was induced at 16°C overnight with 0.1 mM of IPTG after 30 min of acclimation, and bacterial cells harvested by centrifugation at 4000g for 10 min. Pellets were lysed enzymatically by resuspension and incubation at room temperature for 30 min in lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazol, 5% glycerol, 1% Tween 20 [Sigma-Aldrich], 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, EDTA free protease inhibitor [Roche], 1 mg/mL lysozyme [Lysozyme human, Sigma-Aldrich]). DNase treatment was performed at room temperature for 15 min using DNase I from bovine pancreas (Sigma-Aldrich). Sonication of the lysate was performed on ice (3 × 10 s, amplitude 16; Soniprep 150 Plus; MSE). Soluble fractions were then harvested by centrifugation (21,000g, 4°C, 20 min) and filtered through 0.22 μm filters (Millipore).

For preliminary assays of the oat UGT candidates, the soluble protein fraction was enriched for His-tagged recombinant enzymes using nickel-charged resin (Ni-NTA agarose resin; Qiagen). Ni-NTA resin (300 mL) preequilibrated with buffer A (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5, 20 mM imidazol, 5% glycerol) was incubated 30 min at 4°C with the protein extract. The resin was washed three times with 500 μL buffer A and eluted with 300 μL buffer B (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.8, 500 mM Imidazol, 5% glycerol). Protein concentrations were estimated from Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE gels relative to a BSA standard. Quantification of recombinant proteins was performed by densitometric analysis using the software ImageJ. Alternatively, for enzymatic assays performed with deglycosylated avenacin A-1 (Figure 8B), recombinant UGTs were purified by IMAC with an ÄKTA purifier apparatus (GE Healthcare) using a nickel-loaded HiTRAP IMAC FF 1 mL column (GE Healthcare) with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The column was preequilibrated with buffer A before loading with protein extract. Unbound proteins were eluted with buffer A (0 min to 16 min), and a linear gradient of 0% to 60% buffer B was then applied to the system over 30 min. Fractions containing recombinant enzyme (monitored by UV absorbance at 280 nm) were pooled and concentrated using a 10-kD centrifugal filter (Amicon, Ultra-4; Sigma-Aldrich). Protein purity was estimated by electrophoresis and protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford method with a BSA standard curve (Bradford, 1976). Samples were aliquoted and flash-frozen in liquid N before storage at −80°C.

Trichlorophenol Glycosylation Assays

Reactions were performed in a total volume of 75 μL, composed of 100 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7, 100 μM TCP, and 200 μM uridine diphospho sugars (UDP-α-D-Glc, UDP-α-D-Gal, or UDP-β-L-arabinopyranose; see Supplemental Table 8 for suppliers). Reactions were initiated by addition of 1 μg of enriched recombinant enzyme to prewarmed reaction mixes and incubated overnight at 28°C before stopping with 3.5 μL trichloroacetic acid (TCA; 6.1 N). Proteins were precipitated by centrifugation at 21,000g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were stored at −20°C before analysis by HPLC-UV (see “Method A—HPLC-UV Analysis of TCP Glycosylation Assays”).

Glycosylation Assays Using Different Triterpenoid Acceptors

Reactions (50 μL) comprised 100 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5, 200 μM of triterpenoid (see Supplemental Table 8 for suppliers), and 500 μM uridine diphospho sugars (UDP-α-D-Glc [UDP-Glc], UDP-Gal, or UDP-β-L-arabinopyranose [UDP-Ara]; see Supplemental Table 8 for suppliers). Reactions were initiated by addition of 1 μg of enriched recombinant enzyme to the prewarmed reaction mix and incubated overnight at 25°C with shaking at 300 rpm. Reactions were stopped by partitioning twice the sample in 100 μL ethyl acetate. The organic phase was dried under N2 flux and resuspended in 20 μL methanol before analysis.

TLC plates were spotted with 10 μL of methanolic sample and prerun three times in 100% methanol 0.5 cm above the loading line, before elution with dichloromethane/methanol/H2O (80:19:1; v:v:v). They were then sprayed with methanol:sulfuric acid (9:1) and heated to 130°C for 2 min to 3 min until coloration appeared. Photographs were taken under UV illumination at 365 nm. The organic phase was dried under N2 flux and resuspended in 20 μL methanol for analysis.

Hydrolysis and Partial Reglycosylation of Avenacin A-1

Purified avenacin A-1 (Supplemental Table 7) was hydrolyzed in 1 M HCl for 15 min at 99°C with shaking at 1400 rpm. The preparation was then cooled on ice and buffered with 1:1 (v/v) unequilibrated TRIS 1 M. The hydrolyzed sample was extracted twice by ethyl acetate, and the combined organic extracts were dried under N2 flux and resuspended in DMSO. The resulting hydrolyzed avenacin A-1 (approximately 100 μM in 50 μL reaction volume) was incubated with 500 μM UDP-Ara and 2 μg purified recombinant AsUGT99D1 in 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5 with 0.5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin. After 30 min incubation at 25°C, the reaction was stopped by addition of 2 μL TCA 6.1 N. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 21,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was diluted with methanol (50% final volume) before analysis by LC-MS with fluorescence detection (see “Method B—Analysis of Avenacin A-1 Reglycosylation Assay Using LCMS-Fluorescence”).

Transient Expression in Nicotiana benthamiana

UGT CDSs were cloned into pEAQ-HT-DEST1 (Sainsbury et al., 2009) via an LR clonase II reaction following the manufacturer’s instruction (Invitrogen). Strain culture and agroinfiltrations were performed following previously published methods (Reed et al., 2017). Briefly, expression constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. Coexpression of combinations of genes was achieved by mixing equal volumes of A. tumefaciens strains harboring different expression constructs (previously diluted down to 0.8 OD600nm). An A. tumefaciens strain containing a GFP expression construct was used as a control and also coinfiltrated in mixtures as a “blank” as appropriate to ensure comparable bacterial densities between infiltrations.

Metabolite Extraction of N. benthamiana Leaves

Leaves were harvested 6 d after agro-infiltration and freeze-dried. Freeze-dried leaf material (20 mg) was ground twice at 20 c.s−1 for 30 s (TissueLyser; Qiagen). Extractions were performed in 1 mL 80% methanol with 20 μg of digitoxin (internal standard, IS; Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min at 90°C, with shaking at 1400 rpm (Thermomixer Comfort; Eppendorf). Samples were centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 min and 0.8 mL of the supernatant partitioned twice with 0.3 mL of hexane. The aqueous phase was dried in vacuo (EZ-2 Series Evaporator; Genevac). Dried material was resuspended in 0.5 mL distilled water and partitioned twice with 0.5 mL of ethyl acetate. The organic phase was dried in vacuo and resuspended in 150 μL of methanol followed by filtration (0.2 μm, Spin-X; Costar). Filtered samples were transferred to glass vials and 50 μL of water added. Samples were analyzed by HPLC-CAD (see “Method C—HPLC-CAD Analysis of N. benthamiana Methanolic Extracts”).

Purification and Structure Determination of EpHβA-Ara

Agro-infiltration of N. benthamiana leaves for coexpression of SAD1, SAD2 and UGT99D1 was performed by vacuum infiltration of 44 N. benthamiana plants following published methods (Reed et al., 2017). The plants were harvested 6 d later and the leaves lyophilized. Dried leaf material was ground to a powder using a mortar and pestle and processed by pressurized extraction as described in Reed et al. (2017). The extraction method consisted of an initial hexane cycle (5 min pressure holding at 130 bars followed by 3 min discharge, extraction cells being heated at 90°C) to remove chlorophylls and apolar pigments. The following five cycles were performed using ethyl acetate and were used for further purification.

The crude extract was dried by rotary evaporation before resuspension in 80% aqueous methanol. The methanolic extract was then partitioned three times in n-hexane (1:1) until most of the remaining chlorophyll had been removed. The resulting methanolic sample was dried by rotary evaporation together with diatomaceous earth to allow dry-loading of the flash chromatography column (Celite 545 AW; Sigma-Aldrich).

Purification was performed using an Isolera One (Biotage) automatic flash purification system. The crude solid was subjected to normal phase flash chromatography (column SNAP KP/Sil 30 g; Biotage). The mobile phase was dichloromethane as solvent A and methanol as solvent B. After an initial isocratic phase with 4% B (5 column volumes [CV]), a gradient was set from 4% to 25% B over 40 CV. The fractions containing the EpHβA-Ara were identified by TLC, pooled and then dried down by rotary evaporation together with diatomaceous earth. The resulting solid was subjected to reverse phase flash chromatography (SNAP C18 column 12 g; Biotage). The mobile phase was water as solvent A and methanol as solvent B. After an initial isocratic phase with 70% B (3 CV), a gradient was set from 70% to 90% B over 20 CV. The fractions containing EpHβA-Ara were identified by TLC and pooled before rotary evaporation down to 10 mL. A precipitate was observed in the resulting aqueous sample at 4°C. EpHβA-Ara was pelleted by centrifugation at 4000g for 15 min.

NMR spectra were recorded in Fourier transform mode at a nominal frequency of 400 MHz for 1H NMR, and 100 MHz for 13C NMR, using deuterated methanol. Chemical shifts were recorded in ppm and referenced to an internal TMS standard. Multiplicities (described as s, singlet; d, doublet; and dd, coupling constants) are reported in Hertz as observed and not corrected for second-order effects. Where signals overlap, 1H δ is reported as the center of the respective HSQC cross peak (Supplemental Figure 4).

Characterization of the aat1 (#807) Mutant

The AsAAT1 gene was sequenced in 47 uncharacterized sodium azide-generated avenacin-deficient mutants (Papadopoulou et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2006). Genomic DNA was extracted by the Genotyping Scientific Service of the John Innes Centre using an in-house extraction method. PCR amplification of AsAAT1 full-length CDSs (see Supplemental Table 8 for primer sequences) was sequenced (Eurofins), and sequences searched for single nucleotide polymorphisms using CLCbio software (Qiagen).

For analysis of segregating progeny, root tips were harvested from 3-d-old seedlings of F2 progeny from a cross between the avenacin-deficient mutant #807 and the A. strigosa S75 wild type (Papadopoulou et al., 1999), incubated in methanol at 50°C for 15 min with shaking at 1400 rpm, and then put on ice. The methanolic extract was transferred to a new tube, dried under N2 flux, and resuspended in 50 uL of methanol. Aliquots (5 uL) of each sample were loaded onto TLC plates. Chromatography was performed using dichloromethane:methanol:H2O (80:19:1; v:v:v) and the TLCs examined under UV illumination (365 nm). In parallel, genomic DNA was extracted by the Genotyping Scientific Service from the leaves of the same seedlings 10 d after germination. Seedlings were grown on distilled water agar after root tip harvesting as described in Papadopoulou et al. (1999). A 533-bp region spanning the region of the single nucleotide mutation detected in the AsAAT1 gene of mutant #807 (753G→A) was amplified by PCR for each seedling and sequenced (see Supplemental Table 7 for primers).

Metabolite Analysis of Oat Root Extracts

Root tips (5 mg) were harvested from 3-day-old seedlings of wild-type A. strigosa and the avenacin-deficient A. strigosa mutant #807. Root material was ground using a homogenizer (2010 Geno/Grinder; SPEX SamplePrep) and extracted with methanol following the method described for analysis of triterpenoid glycosides in N. benthamiana leaf extracts, detailed above. Filtered methanolic samples were diluted threefold in 50% methanol and analyzed by LC-MS-CAD-fluorescence (see “Method D—Metabolites Analysis of Oat Root Tips Using LCMS-CAD-Fluorescence”).

Pathogenicity Tests

Pathogenicity tests to assess root infection with the fungal pathogen Gaeumannomyces graminis var tritici isolate T5 were performed as described in Papadopoulou et al. (1999). Seedlings were scored for lesions on the roots following 3 weeks incubation using a 7-point scale.

Linkage Analysis

Avena atlantica accession Cc7277 (IBERS collection, Aberystwyth University) was sequenced by Illumina technology to ∼38-fold coverage with a number of paired end and mate pair libraries. Assembled contigs were then mapped by survey sequencing of recombinant inbred lines from a cross between Cc7277 and A. strigosa accession Cc7651 (IBERS). Annotations of contigs linked to the previously identified avenacin biosynthetic genes were used to identify potential UGT candidate genes.

Enzyme Assays with Recombinant GmSSAT1

Recombinant GmSSAT1 and UGT73F2

The coding sequences of the soybean candidate UGT GmSSAT1 and the characterized G. max UGT73F2, which glucosylates the nonacetylated saponin A0-ag (Sayama et al., 2012) were synthesized commercially (IDT). These sequences were flanked with AttB adapters, allowing subsequent transfer into pH9GW using Gateway technology as described earlier. Recombinant GmSSAT1 was expressed in E. coli Rosetta 2 strain DE3 (Novagen) and purified as described in the main text.

Enzyme assays were performed in 100 μL reaction volumes consisting of 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 7.5, 100 μM of soyasaponin I, and 300 μM uridine diphospho sugars (UDP-α-D-Glc, UDP-α-d-Gal, or UDP-β-l-arabinopyranose; see Supplemental Table 8). Reactions were initiated by addition of 1 μg of enriched recombinant enzyme preparation into the prewarmed samples and incubated at 25°C. After 40 min, 80 min, and 200 min, 30 μL of reaction mixture was stopped by addition of methanol (50% final concentration). Assays for glucosylation of the GmSSAT1 product by recombinant UGT73F2 were conducted similarly, after semipreparative purification of soyasaponin I arabinoside (see below). Samples were analyzed by HPLC-MS-CAD using “Method D—Metabolites Analysis of Oat Root Tips Using LCMS-CAD-Fluorescence” with modified gradients: 25% to 46% [B] over 9.5 min (for GmSSAT1 assays) and 20% to 46% [B] over 19.5 min (for UGT73F2 assays). Reactions products were also analyzed by HR-MS (see “Method E—HR-MS Analysis of In Vitro Reaction with Recombinant Soybean Enzymes”).

Purification of Soyasaponin I Arabinoside:

Semipreparative HPLC purification of soyasaponin I arabinoside (SSI-Ara) was performed with an UltiMate 3000 HPLC system (Dionex) combined with a Corona Veo RS CAD using a Kinetex column 2.6 μm XB-C18 100 Å, 50 × 2.1 mm (Phenomenex). GmSSAT1 was incubated with 60 nmoles of soyasaponin I in the presence of excess UDP-Ara until completion. The reaction products were fractionated using a linear gradient (25% to 46% of acetonitrile:water). Fractions containing SSI-Ara were dried and purity assessed by CAD-HPLC (see “Method D—Metabolites Analysis of Oat Root Tips Using LCMS-CAD-Fluorescence”). The purity was comparable to that of commercial soyasaponin I (Chengdu Biopurify Phytochemicals; purity > 98%).

Structural Modeling of AsAAT1

A homology model was generated with I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015) using the crystal structure of Medicago truncatula UGT71G1 complexed with UDP-Glc as a template (PDB: 2ACW; Shao et al., 2005). This homology model contained a strained loop comprising residues Trp396 to Ser402 due to a two-residue insertion relative to the template. To identify the most likely conformation for this loop, 20 loop models were generated using the MODELER (Sali and Blundell, 1993) plugin to Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). The six loop conformations with the best scores in terms of zDOPE, estimated root mean squared deviation, and estimated overlap were used to generate models for the structure of the complex with UDP-Ara, based on the conformation of UDP-Glc found in PDB: 2ACW (Shao et al., 2005). The resulting draft-docked complexes were relaxed using the molecular dynamics program GROMACS (Van Der Spoel et al., 2005) and the force field 53a6 (Oostenbrink et al., 2004). The models were solvated in a cubic periodic box of SPC 3-site water molecules and subjected to 104 steps of energy minimization. The necessary parameters for UDP-Ara were based on those available for uridine, ATP, and Glc in the 53a6 force field. Following this step, the optimal model was selected for analysis based on having the best QMEAN score (Benkert et al., 2008) and no Ramachandran or rotamer outliers in the remodeled loop according to the structure validation service, MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010).

Purification of Hydrolyzed Avenacin A-1

Hydrolysis of purified avenacin A-1 (483 μg; Supplementa Table 8) was scaled up using the method described previously (i.e., partial re-glycosylation of avenacin A-1). The entire sample was directly subjected to reverse phase flash chromatography (SNAP C18 column 12 g, Biotage). Elution was performed with a linear gradient from 65% to 72% methanol:water over 55 CV. Elution of hydrolyzed avenacin A-1 was monitored by absorbance at 365 nm. Fluorescent fractions were collected, dried via rotary evaporation, and subjected to normal phase flash chromatography (column SNAP KP/Sil 30 g; Biotage). The mobile phase was dichloromethane as solvent A and methanol as solvent B. After an initial isocratic phase with 5% B (5 CV), a gradient was set from 5% to 11% B over 40 CV. Fluorescent fractions were pooled and dried. No impurities were detected by HPLC-CAD-fluorescence analysis. Absolute quantification was performed by HPLC-fluorescence using an avenacin A-1 standard. A total of 208 μg of hydrolyzed product was recovered and dissolved in DMSO as a 5 mM stock solution for use in enzyme assays.

Mutagenesis of AsAAT1

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed by PCR amplification using the expression vector pH9GW-AsAAT1 as the template and the mutated complementary sequences as primers (Supplemental Table 7). Mutagenized genes were cloned into the entry vector pDONR207, transferred back into the pH9GW expression vector, and transformed into E. coli BL21 Rosetta. Recombinant enzymes were purified via IMAC using an KTA purifier apparatus and quantified with the Bradford method as described above.

In Vitro Analysis of the AsAAT1 Wild-Type Enzyme and Mutant Variants

Wild-type and mutagenized AsAAT1 enzymes were expressed and purified as described above (Supplemental Figure 7A). Optimal catalytic conditions for AsAAT1 were observed at pH 6.5. Reactions were performed in 55 μL volumes at 25°C and sampled under steady-state conditions by transferring 10 μL reaction mix into 55 μL ice cold 10% TCA to stop the reaction. Sugar donor mix (10 μL) containing 5 μM UDP-Ara, UDP-Glc, UDP-Xyl, or UDP-Gal was added to prewarmed enzyme. The latter was composed of 30 μM deglycosylated avenacin A-1 dissolved in 0.5 mM methyl-β-cyclodextrin (substrate inhibition was observed with acceptor concentrations of ≥30 μM). Reactions were performed in 50 mM TRIS-HCl pH 6.5 with 0.3 μg of recombinant enzyme. Precipitated protein was removed by centrifugation at 21,000g for 10 min at 4°C and supernatants stored at −20°C before analysis by HPLC-fluorescence (see “Method F—HPLC-Fluorescence Analysis of Enzymatic Assay with Deglycosylated Avenacin A-1 as Substrate”).

Triterpenoids Chromatographic Analysis

All analytical LC methods were designed with a flow rate of 0.3 mL.min−1 and a Kinetex column 2.6 μm XB-C18 100 Å, 50 × 2.1 mm (Phenomenex). Solvent A: (H2O + 0.1% formic acid) Solvent B: (acetonitrile [CH3CN] + 0.1% FA).

Method A—HPLC-UV Analysis of TCP Glycosylation Assays

Instrument: Dionex UltiMate 3000. Injection volume: 15 µL. Gradient: 20% [B] from 0 to 1.5 min, 20% to 50% [B] from 1.5 min to 16 min, 50% to 95% [B] from 16 min to 16.5 min, 95% [B] from 16.5 min to 18.5 min, 95% to 20% [B] from 18.5 min to 20 min. Detection: UV 205 nm.

Method B—Analysis of Avenacin A-1 Reglycosylation Assay Using LCMS-Fluorescence

Instrument: Prominence HPLC system, RF-20Axs fluorescence detector, single quadrupole mass spectrometer LCMS-2020 (Shimadzu). Injection volume: 5 µL. Gradient: 35% [B] from 0 min to 2 min, 35% to 50% [B] from 2 min to 12 min, 50% to 95% [B] from 12 min to 12.5 min, 95% [B] from 12.5 min to 14 min, 95% to 35% [B] from 14 min to 14.1 min, 35% [B] from 14.1 min to 15 min. Detection: fluorescence (Excitation 353 nm/Emission 441 nm), MS (dual ESI/APCI ionization, DL temperature 250°C, nebulizing gas flow 15 L.min−1, heat block temperature 400°C, spray voltage Positive 4.5 kV, Negative −3.5 kV).

Method C—HPLC-CAD Analysis of N. benthamiana Methanolic Extracts

Instrument: UltiMate 3000 HPLC system, Corona Veo RS CAD (Dionex). Injection volume: 15 µL. Gradient: 25% [B] from 0 min to 1.5 min, 25% to 58% [B] from 1.5 min to 16 min, 58% to 95% [B] from 16 min to 16.5 min, 95% [B] from 16.5 min to 18.5 min, 95% to 25% [B] from 18.5 min to 19 min, 35% [B] from 19 min to 20 min. Detection: charged aerosol (data collection rate 10 Hz, filter constant 3.6 s, evaporator temperature 35°C, ion trap voltage 20.5 V).

Method D—Metabolites Analysis of Oat Root Tips Using LCMS-CAD-Fluorescence

Instrument: Prominence HPLC system, RF-20Axs fluorescence detector (Shimadzu), single quadrupole mass spectrometer LCMS-2020 (Shimadzu), Corona Veo RS CAD (Dionex). Injection volume: 10 µL. Gradient: 20% [B] from 0 min to 3 min, 20% to 60% [B] from 3 min to 28 min, 60% to 95% [B] from 28 min to 30 min, 95% [B] from 30 min to 33 min, 95% to 20% [B] from 33 min to 34 min, 20% [B] from 34 min to 35 min. Detection: fluorescence and charged aerosol (settings identical to previous methods).

Method E—HR-MS Analysis of In Vitro Reaction with Recombinant Soybean Enzymes

Instrument: Prominence HPLC system, IT-TOF mass spectrometer (Shimadzu). Injection volume: 5 µL. Gradient: 20% [B] from 0 min to 2 min, 20% to 46% [B] from 2 min to 16.5 min, 46% to 95% [B] from 16.5 min to 17 min, 95% [B] from 17 min to 18.5 min, 95% to 20% [B] from 18.5 min to 19 min, 20% [B] from 19 min to 20 min. Detection: Negative ESI ionization (capillary temperature 250°C, nebulizing gas 1.5 L.min−1, heat block temperature 300°C, spray voltage −3.5 kV. Energy/collision gas MS2 50%, MS3 75%).

Method F—HPLC-Fluorescence Analysis of Enzymatic Assay with Deglycosylated Avenacin A-1 as Substrate

Instrument: Prominence HPLC system, RF-20Axs fluorescence detector (Shimadzu). Injection volume: 7 µL. Gradient: 40% [B] from 0 min to 2 min, 40% to 50% [B] from 2 min to 6 min, 50% to 95% [B] from 6.5 min to 7 min, 95% [B] from 7 min to 7.5 min, 95% to 20% [B] from 7.5 min to 8 min, 20% [B] from 8 min to 9 min. Detection: fluorescence (Excitation 353 nm/Emission 441 nm).

Gas Chromatography

Sample preparation and GC-MS analysis was performed as described in Reed et al. (2017). Briefly, approximately 5 mg of dried agro-infiltrated leaf material was saponified in alkaline conditions. Hexane partitioning was used to remove saponified pigments. The unsaponifiable aqueous fraction was derivatized with 1-(trimethylsilyl)imidazole (Sigma-Aldrich) and analyzed by GC-MS. Coprostan-3-ol (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as an IS (final concentration of 10 μg/mL).

Accession Numbers