Abstract

Osteomas of the middle ear are rare benign tumors. Their consequences and symptoms are due to their specific location, such as the promontory or the epitympanum and their contact with the facial nerve, the semicircular canal, the ossicles, and the oval or round windows.

We report a very unusual case of middle ear osteoma (MEO) in a 23-year-old male patient causing a right mixed hearing loss by contacting and overwhelming the incus and stapes. The lesion was also closely attached to the tympanic portion of the fallopian canal. Since the stapes was not clearly visible behind the lesion, careful observation was preferred to surgery owing to the high risk of inner ear damage and facial palsy with removal of the lesion.

Middle ear osteomas are rarely situated at this critical site. Regular clinical and computerized tomography monitoring is warranted to check their growth. This case also supports the etiological theory of chronic middle ear inflammation causing osteomas.

Keywords: Middle ear osteoma, middle ear lesion, mixed hearing loss, stapes tumor, middle ear osteoma etiology

INTRODUCTION

Osteomas are the most common tumors of the temporal bone[1]. They mostly occur in the external auditory canal, although rare cases have been observed in the middle ear space [1, 2]. Middle ear osteomas (MEOs) are benign lesions arising from the bony structures of the middle ear and epitympanum [3]. They are often clinically silent and only discovered at otoscopy. If not, presenting symptoms depend on their specific location, such as the promontory and the epitympanum or their contact with critical structures, such asthe facial nerve, the semicircular canal, the ossicles, and the oval or round windows [4]. The most commonly reported symptom is unilateral progressive conductive hearing loss induced by ossicular chain compromise [5]. This case report describes a case of an MEO causing mixed hearing loss by being in contact with the incus, stapes, and oval window.

CASE PRESENTATION

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and for any accompanying images from his audiogram or computerized tomography (CT).

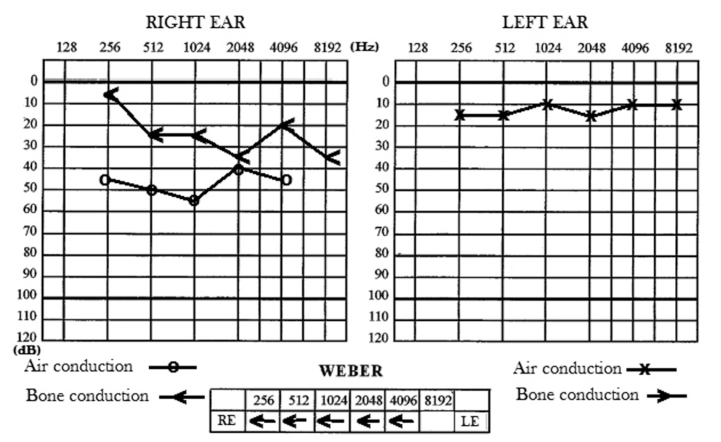

A 23-year-old male patient was referred for right-sided mixed hearing loss. The deafness had appeared progressively over a few years and had worsened over the last year. On otoscopy, the tympanic membrane was normal, and no tumor was visible at its contact or behind. There was no otorrhea, pain, tinnitus, facial nerve weakness, or vestibular symptoms nor history of ear infection or prior surgery. Vestibular and head and neck examination were normal. The fistula test was negative. The patient had no other disease of any kind. There was no history of noise exposure, head trauma, or familial hearing loss. At audiometry, the air conduction pure-tone average (PTA) and bone conduction PTA of the right ear were 50 and 30 dB hearing level (HL), respectively. The mean air–bone gap was 25 dB HL. A Carhart notch was observed at 2000 Hz. The speech reception threshold was 45dB. Left hearing was subnormal (PTA=12 dB HL) (Figure 1). An on-off effect at right acoustic reflex testing was observed at tympanometry. This was highly suggestive of a right-sided otosclerosis.

Figure 1.

Hearing test (audiogram) showing right mixed hearing loss with air-bone gap.

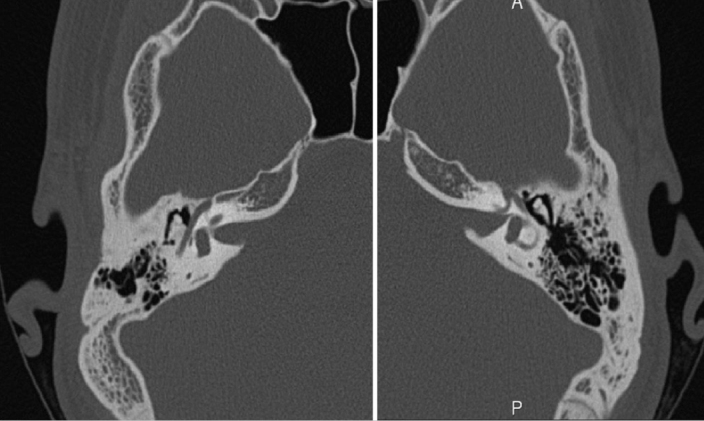

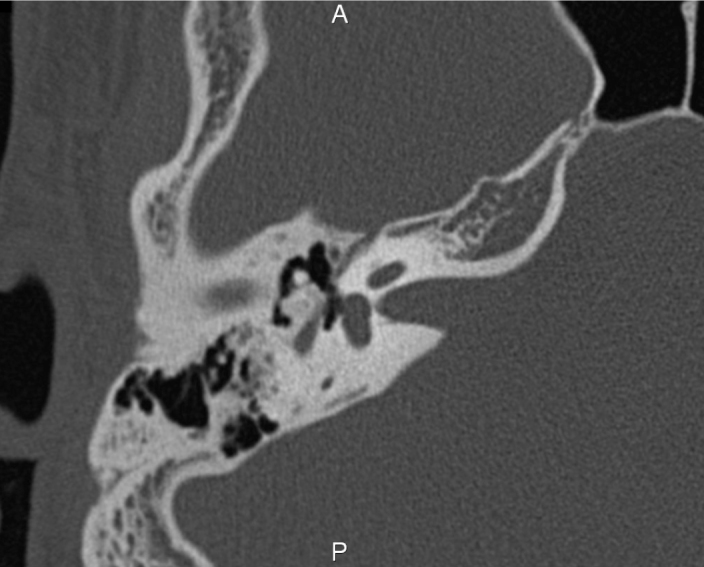

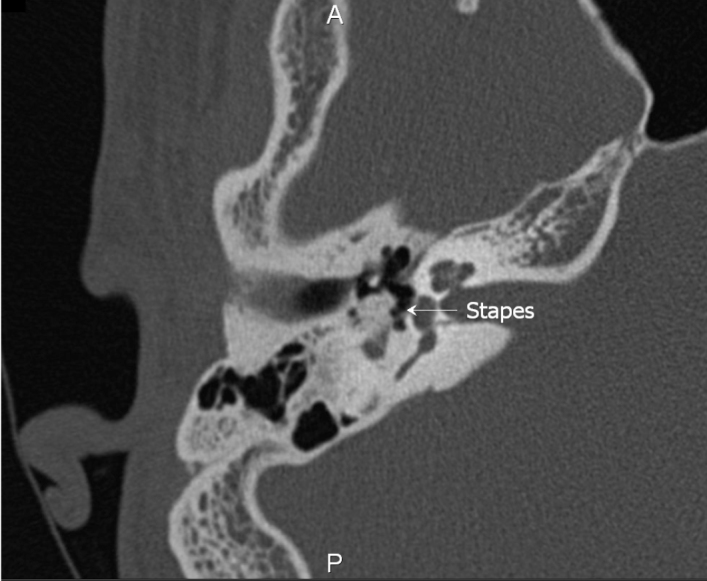

A middle ear high-resolution computerized tomography (HRCT) scan that was requested for confirmation revealed a hyperdense homogeneic mass of calcic tonality and bone density (1265 Hounsfield units) in the right middle ear at the level of the upper mesotympanum (Figures 2–5). Measuring 5.9×4.6×2.7 mm, it appeared irregularly shaped (Figure 4) and involved the promontory, the three ossicles (Figures 3–4), and the fallopian canal bone (Figure 5) at the level of its tympanic portion. There was a bony continuity between the latter and the lesion. There was no evidence of bony erosion or associated soft tissue mass that would have suggested the differential diagnosis of ossifying hemangioma [6]. The CT characteristics of this mass and its connection with the facial nerve and the stapes led to the definite diagnosis of MEO. Surgical removal was denied to the very high risk of facial nerve and inner ear lesion. We advocated clinical monitoring and imaging to evaluate the progression of the disease. The patient has declined a regular hearing aid because of the importance of water sports hobby in his personal life and minor hearing discomfort. A BONEBRIDGE™ implant (MED-EL, Innsbruck, Austria) was proposed in the event of major discomfort in order to close the air–bone gap and improve bone conduction.

Figure 2.

Axial CT images using bone algorithm demonstrating the difference in petrous bone pneumatization.

Figure 3.

Axial CT image of the right temporal bone showing incus and malleus involvement with the osteoma.

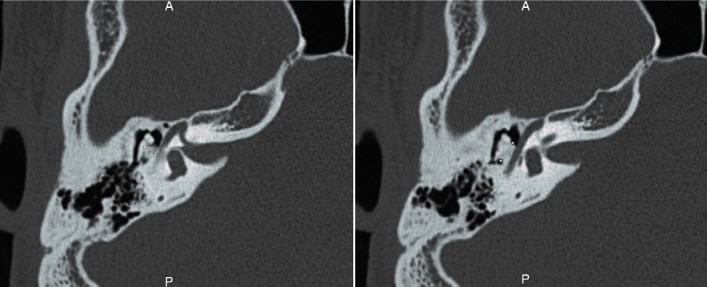

Figure 4.

Axial CT image of the right temporal bone showing intimate contact of the osteoma with the stapes (white arrow).

Figure 5.

Axial CT image showing the osteoma contacting the fallopian canal and its dimensions.

The 1 and 2-year CT monitoring had shown a stabilized size. Symptoms were also stable.

DISCUSSION

Osteomas of the temporal bone are rare tumors that are mostly observed in the external auditory canal, arising from the tympanic bone. They are of unknown origin. Thomas suggested a genetic etiology in two cases occurring in siblings [7]. Chronic inflammation due to chronic otitis has also been proposed by Yoon et al. [5]. In our case, the right temporal bone appeared less pneumatized and denser than the left one, an aspect in favor of this hypothesis.

Occasionally, osteomas can also be observed in the middle ear space [1]. In 2014, Yoon et al. [5] conducted a literature review and found 35 cases to which they added two more to observe. They reported a male predominance (2:1 sex ratio). As in our case, the lesions are predominated in young subjects (median age 28.5 years, 38.9% (14) <20 years). Three (10.8%) patients in their review had a mixed form, and 25 (67.6%) had a conductive hearing loss. The most common site of MEO is the promontory (33.3%), followed by the incus (13.9%). In our case, the lesion was contacting both sites.

In most cases, the diagnosis is made by HRCT. If required, confirmation may be obtained histopathologically during explorative surgery [5]. The main differential diagnosis is exostosis. However, exostoses, which occur only in the external auditory canal, are non-tumoral multiple, bilateral, broad-based elevations of the tympanic bone in response to repeated exposure to cold water, whereas osteomas [8] are solitary, unilateral, pedunculated tumors of unknown origin that may invade the middle ear.

Only three other cases of MEOs in contact with the stapes have been reported to date [4, 8, 9]. The one reported by Curtis et al. illustrates the difficulties of treating such cases [4]. The patient was suffering from a mild conductive low-frequency hearing loss and facial nerve weakness. Surgical removal resulted in partial recovery of facial function (House-Brackmann grade IV to II), but the stapes was removed along with the osteoma, and postoperative hearing status was not reported. The case reported by Vérillaud et al. [9] was very similar to ours. The MEO was contiguous to the tympanic segment of the facial nerve and induced conductive hearing loss due to the involvement of the incus and stapes. A middle ear exploration by a transcanal approach confirmed the diagnosis, and the tumor was partially removed using a curette. As suggested by preoperative CT scan, the facial nerve was dehiscent but not overhanging. The stapes was released and separated from the incus. A silicone sheet was interposed between it and the remaining part of the mass, and a stapes to tympanic membrane ossiculoplasty was performed using a double cartilage sheet. The postoperative course was uneventful with no facial weakness or vertigo. Hearing returned to normal with complete closure of the air–bone gap.

One may wonder why the tumor induced a mixed hearing loss in our patient, instead of a pure conductive one. By compressing the stapes, the MEO may have induced stiffening of the stapedial-vestibular joint, as is observed in otosclerosis. The on-off effect observed on the tympanogram may have been due to an incomplete blockage of the stapes footplate, as in otosclerosis.

Of the 38 cases of MEOs reported in the literature, only one patient did not undergo surgical resection [10]. This is probably due to the fact that the incidence of such lesions is underestimated in the literature so the percentage of those operated on is likely overestimated. Indeed, only growing lesions necessitating surgical removal have been reported to date. Many of these lesions only invade the promontory and are monitored only otoscopically. By focusing on those MEOs contacting the stapes and facial nerve, we underline the fact that their surgical treatment is highly challenging. The surgeon must be aware that potential tumor growth threatens mid-term facial nerve and hearing function in these young subjects. Fortunately, their growth is slow, and significant clinical issues are rare. If the tumor is pedunculated and small, it seems better to remove it. If it is contiguous to the tympanic segment of the facial nerve with no preoperative facial weakness, it may be partially removed to prevent any definitive postoperative facial nerve injury [9].

According to Thomas [7], long-term monitoring of MEOs is a viable solution, especially when they are asymptomatic. A periodic evaluation rather than surgical exploration is probably preferable [11]. Anyway, close clinical monitoring is needed throughout the patient’s life since MEOs are known to penetrate the inner ear or injure the facial nerve and cause facial palsy, vertigo, or sensorineural hearing loss, as in the case reported by Hornigold [3].

Even if Wegner et al.[12] think that preoperative CT has little to add in confirming otosclerosis, and that it may not be necessary to confirm the diagnosis before surgery in case of eloquent history, stapedius reflex testing, and pure-tone audiometry. We would recommend as the official recommendations of the French ENTSociety (SFORL) a systematic preoperative CT, not only to diagnose otosclerosis but also to eliminate alternative diagnoses thatare not rare. Indeed, CT demonstrates a high rate of this alternative diagnoses in suspected otosclerosis, one-third according to Dudau et al. [13]. We think as well as Parra et al. [14] that preoperative imaging analysis of the oval window width and the facial promontory angle can predict operative difficulty in otosclerosis surgery. Every patient in our service with otosclerosis suspicion has a preoperative CT, and not only for those with suspected additional abnormalities, specific preoperative planning, or out of legal necessity as Wegner et al. [12].

CONCLUSION

It is rare for MEOs to be located like this one. Early recognition and regular clinical and CT monitoring are imperative since surgical removal seems too risky to be attempted. This case also supports the etiological theory of osteomas caused by chronic middle ear inflammation despite no previous subjective or objective otitic history, as in this patient.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor V. Darrouzet for his supervision and R. Gallard for his help.

Footnotes

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patient who participated in this study.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author contributions: Concept – J.M., E.M.P.; Design – J.M., A.S.Z.; Supervision – V.D., D.B.; Resource - J.M., A.S.Z.; Materials - J.M.; Data Collection and/or Processing - J.M.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - J.M., V.D.; Literature Search - J.M., A.S.Z.; Writing - J.M.; Critical Reviews - V.D., D.B., E.M.P.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kline OR, Pearce RC., Jr Osteoma of the external auditory canal. JAMA Arch Otolaryngol. 1954;59:588–93. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1954.00710050600011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham MD. Osteomas and exostoses of the external auditory canal. A clinical, histopathologic and scanning electron microscopic study. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88:566–72. doi: 10.1177/000348947908800422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hornigold R, Pearch JB, Gleeson JM. An osteoma of the middle ear presenting with the Tullio phenomenon. Skull Base. 2003;13:113–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yuan W, Chen L, Jiang X, Zhang X. Osteoma of stapes in the middle ear: a case report. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34:e119–20. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31829793b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yoon YS, Yoon YJ, Lee EJ. Incidentally detected middle ear osteoma: two case reports and literature review. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:524–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gavilán J, Nistal M, Gavilán C, Calvo M. Ossifying hemangioma of the temporal bone. Arch Otolaryngol Hand Neck Surg. 1990;116:965–7. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870080087022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas R. Familial osteoma of the middle ear. J Laryngol Otol. 1964;78:805–7. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100062794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis K, Bance M, Carter M, Hong P. Middle ear osteoma causing progressive facial nerve weakness: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:310. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vèrillaud B, Guillerè L, Williams MT, El Bakkouri W, Ayache D. Middle ear osteoma: A rare cause of conductive hearing loss with normal tympanic membrane. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2011;132:159–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milroy CM, Phelps PD, Michaels L, Grant H. Osteoma of the incus. J Otoryngol. 1989;18:226–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver FM, Orobello PW, Jr, Mangal A, Pensak ML. Asymptomatic osteomas of the middle ear. Am J Otol. 1993;14:189–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wegner I, van Waes AM, Bittermann AJ, Buitinck SH, Dekker CF, Kurk SA. A systematic review of the diagnostic value of CT imaging in diagnosing otosclerosis. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:9–15. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dudau C, Salim F, Jiang D, Connor SE. Diagnostic efficacy and therapeutic impact of computed tomography in the evaluation of clinically suspected otosclerosis. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:1195–201. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4446-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parra C, Trunet S, Granger B, Nguyen Y, Lamas G, Bernardeschi D. Imaging criteria to predict surgical difficulties during stapes surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38:815–21. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]