Summary

Tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells were found to frequently express the inhibitory receptor NKG2A, particularly in immune-reactive environments and after therapeutic cancer vaccination. High dimensional cluster analysis demonstrated that NKG2A marks a unique immune effector subset preferentially co-expressing the tissue-resident CD103 molecule, but not immune checkpoint inhibitors. To examine if NKG2A represented an adaptive resistance mechanism to cancer vaccination, we blocked the receptor with an antibody and knocked out its ligand Qa-1b, the conserved ortholog of HLA-E, in four mouse tumor models. The impact of therapeutic vaccines was greatly potentiated by disruption of the NKG2A/Qa-1b axis, even in a PD-1 refractory mouse model. NKG2A blockade therapy operated through CD8 T cells, but not NK cells. These findings indicate that NKG2A-blocking antibodies might improve clinical responses to therapeutic cancer vaccines.

Keywords: CD8 T cells, Natural Killer cells, cancer vaccines, HLA-E, Qa-1, NKG2A, mouse tumor models, immune checkpoints

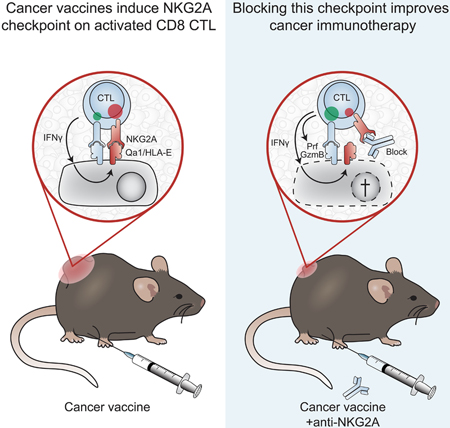

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Checkpoint blockade therapy has shown impressive results in metastasized malignant disease, including melanoma, lung, colon and bladder carcinoma (Topalian et al., 2015). This form of immunotherapy operates via relief of inhibiting signals through immune receptors CTLA-4 and PD-1 on immune cells, reinvigorating a tumor-rejection response (Tumeh et al., 2014, Gubin et al., 2014). Therapeutic cancer vaccines, however, have not yet made a major impact, but are starting to reach clinical practice now that the platforms are optimized and tumor-specific antigens are targeted. Currently, their clinical efficacy is limited to precancerous lesions and patients with minimal residual disease (van der Burg et al., 2016, Melief et al., 2015). Experiments in mouse tumor models demonstrated that cancer vaccines do lead to infiltration of antigen-specific immune cells, but that cancers escape due to a plethora of immune suppression mechanisms thereby curtailing full tumor- rejection (van der Burg et al., 2016, Klebanoff et al., 2011).

One of the emerging suppressive factors in human cancers is the molecule HLA-E, which is a non- classical MHC class I protein. HLA-E is ubiquitously expressed at low levels, but very high expression can be found on trophoblasts and ductal epithelial cells in immune-privileged tissues like placenta and testis, respectively. In cancers, HLA-E is frequently overexpressed compared to their non-transformed counterparts, including melanoma and carcinomas of lung, cervix, ovarium, vulva and head/neck (Talebian Yazdi et al., 2016, Gooden et al., 2011, van Esch et al., 2014, Seliger et al., 2016, Andersson et al., 2016, Silva et al., 2011). The physiological function of HLA-E is to present ‘self’ peptides derived from other HLA class I molecules (DeCloux et al., 1997, Kraft et al., 2000, O’Callaghan et al., 1998) and to limit autoimmune reactivity. Peptide/HLA-E complexes are recognized by the heterodimeric receptor NKG2A/CD94 that transduce inhibiting signals after engagement (Braud et al., 2003, Braud et al., 1998, Malmberg et al., 2002, Le Drean et al., 1998). This inhibiting immune receptor is expressed by cytotoxic lymphocytes, such as natural killer (NK) cells and CD8 T cells that are thereby equipped with the capacity to sense the level of ‘self’ MHC class I on target cells (Anfossi et al., 2006, Braud et al., 1998, Malmberg et al., 2002). Other CD94- comprising heterodimers, such as with NKG2C and NKG2E, can also bind to HLA-E complexes, but with much lower affinity (Snyder et al., 2008, Brooks et al., 1997, Kaiser et al., 2005).

We and others reported a negative correlation of HLA-E on the overall survival of cancer patients (Talebian Yazdi et al., 2016, Gooden et al., 2011, van Esch et al., 2014, Seliger et al., 2016, Andersson et al., 2016, Silva et al., 2011); in particular, the beneficial effect of high CD8 T cell counts within tumor was mitigated by high protein expression of HLA-E (Talebian Yazdi et al., 2016, Gooden et al., 2011). These findings suggested that NKG2A receptor expression on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes might hamper their function by interaction with HLA-E in the microenvironment. In our current study we demonstrate that NKG2A expression is promoted by an immune-reactive profile and that therapeutic cancer vaccines strongly induce this inhibitory receptor on CD8 T cells. Blockade of NKG2A, or genetic knockdown of the HLA-E ortholog Qa-1b in four different murine tumor models turned cancer vaccines into effective therapies.

Results

Expression of the inhibiting NKG2A receptor is associated with worse clinical outcome.

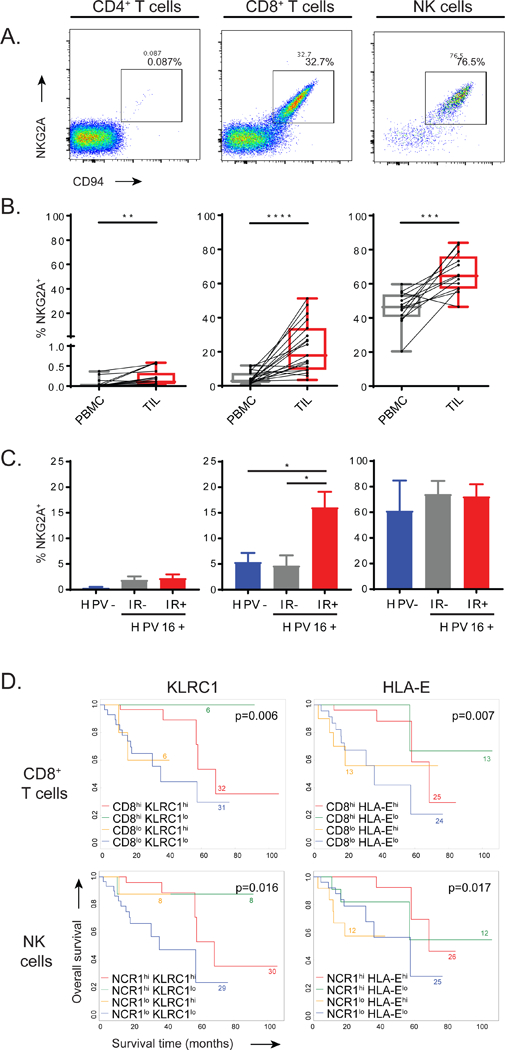

Expression of NKG2A and its co-receptor CD94 was investigated in patients affected by head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and tumor- infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) from carcinomas of different anatomical sites, including oral cavity, larynx and oropharynx were ex vivo analysed by flow cytometry. NKG2A/CD94 surface co-expression was observed on the majority of tumor-infiltrating natural killer (NK) cells and up to 50% of CD8 T cells, but was hardly found on CD4 T cells (Fig. 1A-B). In contrast, matched PBMC samples of these patients only showed expression on NK cells (Fig. 1B). Quantitative RNAseq analysis on sorted lymphocyte subsets confirmed this finding (Fig. S1A). So, NKG2A is generally expressed by a majority of NK cells, but is selectively expressed within the tumor environment by CD8 T cells.

Figure 1: Expression of the inhibiting NKG2A receptor is associated with worse clinical outcome.

(A) Flow cytometry plots displaying the expression of NKG2A and co-receptor CD94 on TIL. (B) Pairwise proportions of NKG2A+ cells in PBMCs and matched TIL in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) biopsies (n=19), paired Student’s t-test). (C) Frequencies of NKG2A+ cells in TIL subsets from HPV16 negative HNSCC (HPV-, n=5), HPV16-positive tumours without ex vivo immune reactivity (IR-, n=5) and HPV16-positive tumours displaying ex vivo immune reactivity to HPV16 (IR+, n=8). Means and SEM, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test (n=18). (D) KaplanMeier survival curves of HPV16+ HNSCC from the TCGA database (n=75). Interaction plots for transcript levels of the NKG2A-coding gene KLRC1 or HLA-E in either CD8 high and low subgroups or NCR1 (coding NKp46) high and low subgroups. Log-rank test. See also Figure S1.

To investigate if the expression of NKG2A on CD8 T cells was related to their activation status in HNSCC, we made use of the presence of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16), which is the causing agent of approximately half of the oropharyngeal subtype of HNSCC. T-cell immune reactivity against the HPV16 oncoproteins E6 and E7 (HPV-IR) was assessed in short-term expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (Welters et al., 2017). Interestingly, HPV-negative tumors and HPV16-positive tumors lacking T cell immune reactivity to HPV antigens (HPV-IR-) harboured much lower frequencies of NKG2A+ CD8 T cells than HPV-induced carcinomas that did harbour HPV16-directed T cell reactivity (HPV-IR+) (Fig. 1C). These data suggested that NKG2A expression on CD8 T cells is predominantly present in immune-reactive tumors. Frequencies of NKG2A+ NK cells were equal in these three groups, again demonstrating the constitutive nature of NKG2A expression in these innate immune cells and the induced nature on CD8 T cells. Of note, proportions of NKG2A+ CD8+ cells were not affected by the short-term expansion protocol, as similar frequencies were observed in paired samples that could also be tested directly ex vivo (Fig. S1B). These data suggested that activation of tumor-specific T cells in the local environment can induce expression of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A.

Functional consequences of NKG2A expression was then examined using quantitative RNAseq data of 75 HPV16+ HNSCC in the publicly available TCGA database (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2015). High transcript levels of the CD8 gene correlated with good prognosis (Fig. 1D). However, high co-expression of KLRC1, which encodes NKG2A, neutralized this clinical benefit, marking NKG2A as a negative prognostic factor in these tumors. Similar observations were made in the interaction analyses for CD8 and the non-classical HLA molecule HLA-E, which is the functional ligand of the NKG2A receptor (Fig. 1D). In addition, comparable survival benefit was found for those tumors with the combinations of the NK cell marker NCR1 and KLRC1 or HLA-E (Fig. 1D). Finally, HPV-negative HNSCC, which are generally less well infiltrated by T cells and which display a worse clinical outcome, did not show these immune gene correlations (Fig. S1C) (Ang et al., 2010, Welters et al., 2017). Together, these data suggested a potential negative role of the NKG2A/HLA-E axis via CD8 T cells and NK cells in HPV-induced head and neck cancer.

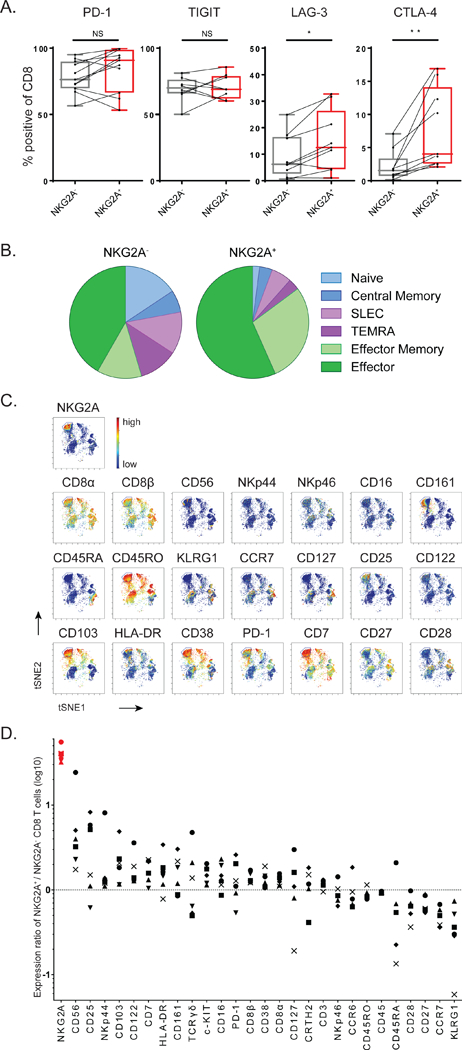

CD8 T cells that express NKG2A belong to CD103+ tissue-resident early effector cells

We then investigated the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating NKG2A+ CD8 T cell subset and compared this with their NKG2A-negative counterparts within the same HNSCC biopsies. Co-expression analyses with other immune checkpoints demonstrated a high frequency of PD-1 and TIGIT positive T cells irrespective of their NKG2A status (Fig. 2A). The LAG-3 and CTLA-4 receptors were expressed at lower frequencies by T cells and more frequent on NKG2A+ CD8 T cells (Fig. 2A). In another set of patients with oropharyngeal carcinoma subtype of HNSCC, the proportions of PD-1 and TIM3 expressing cells did neither show gross differences in distribution between NKG2A+ and NKG2A- T cell subsets (Fig. S1D). Thus, expression of NKG2A seemed to be independent of most other inhibitory checkpoint receptors.

Figure 2: CD8 T cells that express NKG2A belong to CD103+ early effector tissue-resident cells.

(A) Co-expression flow cytometry analysis of inhibitory receptors on CD8 TIL in HNSCC biopsies. Paired Student’s t-test. (B) T cell differentiation stage of NKG2A-positive CD8 TIL was determined by combined expression of these markers: naive (CCR7+ CD127-), central memory (CCR7+ CD127+), SLEC (‘short lived effector cells’: CCR7- CD45RO+ KLRG1+), TEMRA (‘CD45RA+ effectors’: CCR7’CD45RO’), effector memory (CCR7- CD45RO+ KLRG1- CD127+) and effector (CCR7- CD45RO+ KLRG1- CD127-). (C) Density viSNE plot from CyTOF data on pre-gated CD3+CD8+ TIL. (D) Ratios of marker expression (based on the Mean Signal Intensity) on NKG2A+ versus NKG2A- CD8 T cells in cervical carcinomas (n=6). Each symbol represents an individual tumor sample. See also Figures S1 and S2.

Examination of known T cell differentiation markers revealed that virtually all tumor-infiltrating NKG2A+ CD8 T cells expressed CD45RO, but not CCR7 nor KLRG1, indicative of early effector cells (Fig. 2B). Importantly, the pool of NKG2A- CD8 T cells in the same tumor samples contained many more cells belonging to a central memory phenotype as well as to end-stage KLRG1-positive effector phenotypes, like short-lived effector cells (SLEC) and terminally differentiated effector cells (TEMRA). These NKG2A- CD8 T cells indeed produced IFN-γ more frequent upon mitogen stimulation ex vivo, in line with their end-stage effector cell phenotype, whereas the NKG2A+ subset was more associated with the cytolytic proteins perforin and granzyme B (Fig. S1E).

Analysis of the surface adhesion molecule CD103, which is functionally associated with tissue- residency, showed that the vast majority of intratumoral NKG2A+ CD8 T cells was positive (Fig. S1F- G). To gain a detailed insight in the T cell and NK cell subsets associated with NKG2A expression, we embarked on a 36-parameter mass-cytometer (CyTOF) platform. Cluster analyses were first visualized with vi-SNE plots on pre-gated CD3+CD8+ cells. Strikingly, all NKG2A-expressing T cell subsets clustered closely together in all six carcinomas (Fig. 2C and S2A-E). NKG2A was apparently an important discriminating marker among the other 33 mainly lymphocyte-associated molecules. In contrast, NKG2A+ clusters of NK cells were more dispersed in these samples (Fig. S2F-L). The CyTOF analysis confirmed our flow cytometry findings on NKG2A+ T cells, in that this subset did not display an end-stage effector or central memory phenotype due to the selective absence of CCR7, CD127, KLRG1 and CD45RA (Fig. 2C-D). Lack of CD27 and CD28 co-stimulatory receptors further corroborated this notion (Fig. 2C-D). Furthermore, this subset preferentially expressed a number of receptors also found on tumor-infiltrating NK cells, as well as the IL-2 receptor chains CD25 and CD122 (Fig. 2D and S2F). Finally, strong preferential co-expression of CD103 in these six carcinomas suggested that NKG2A demarks an early effector tissue-resident CD8 T cell subset (Fig. 2C-D).

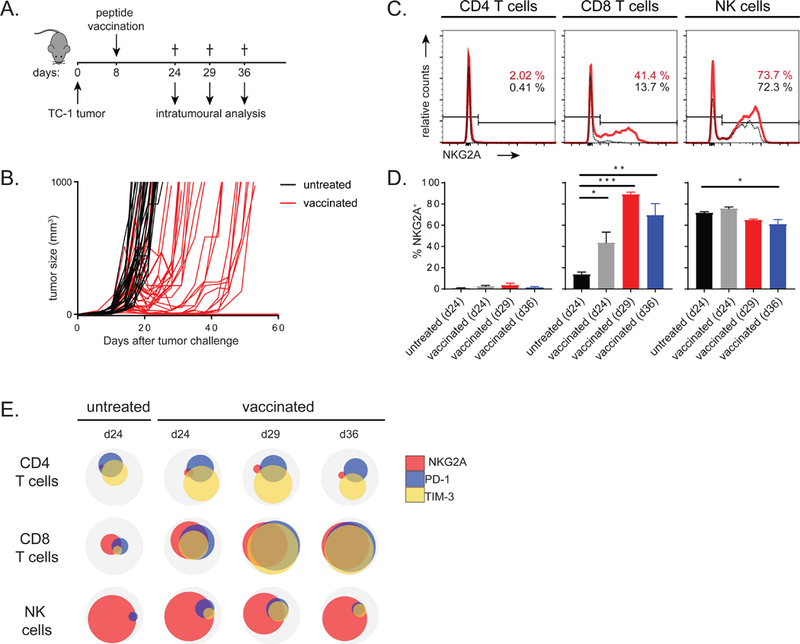

Therapeutic vaccination induces NKG2A on tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells

We aimed to determine the impact of NKG2A expressed by tumor-infiltrating immune cells on the function of these cells and, consequently, tumor outgrowth. We therefore exploited a mouse model for HPV16-induced carcinoma in which we previously developed an effective therapeutic vaccine based on synthetic long peptides (van der Sluis et al., 2015). Vaccination with a long peptide induces a strong anti-tumor CD8 T cell response leading to intratumoral T cell influx and immune-mediated regressions of the carcinomas (van der Sluis et al., 2015). After this temporal remission phase, most tumors rebound from day 20 onward and show progressive tumor outgrowth (Fig. 3A-B). Similar to what was seen in human HNSCC samples, NKG2A expression was observed on CD8 T cells and NK cells, but not on CD4 T cells (Fig. 3C). Importantly, the percentage of NKG2A+ CD8 T cells in the tumor was strikingly enhanced after vaccination-induced immune reactivity and increased over time to frequencies over 80% at the tumor relapse phase (Fig. 3D). Considering the fact that vaccination also resulted in extensively increased numbers of infiltrating CD8 T cells (Fig. S3A), these NKG2A-positive cells represented the dominant population of immune cells in these immune-activated lesions. In contrast, less than 5% of NKG2A-expressing CD8 T cells were detected in the spleen of vaccinated tumor-bearing mice (Fig. S3B), implying a strong selective localization of this receptor in tumors. These data mirrored those from our findings in human oropharyngeal carcinoma samples in that high frequencies of NKG2A-expressing CD8 T cells were predominantly found in tumors harbouring immune reactivity in their tumor microenvironment (Fig. 1C). Frequencies of NKG2A-positive NK cells were stable, like those in human cancer samples, irrespective of therapeutic vaccination (Fig. 3C-D). Importantly, NK cells were dispensable for vaccine-induced tumor regressions (Fig. S3C-D), whereas we previously demonstrated a crucial role for CD8 T cells in this mouse model (van der Sluis et al., 2015).

Figure 3: Therapeutic vaccination induces NKG2A on tumor-infiltrating CD8 T cells.

(A) Experimental layout of the vaccination protocol in the TC-1 model. (B) Tumor growth curves of untreated and vaccinated mice. Each line represents an individual mouse. (C) NKG2A expression on CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and NK cells of intratumoral lymphocytes in untreated (black lines) or vaccinated (red lines) at day 24. (D) Enumeration of means with SEM (n=3–5 per group) of NKG2A+ lymphocytes. One way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Venn diagrams of flow cytometry results showing co-expression on CD8 T cells in the tumor. Means of 3–5 mice per group are depicted from one of three experiments with similar results. See also Figure S3.

Since vaccine-induced tumor remissions are not durable in this model, we additionally investigated expression of the established inhibitory receptors PD-1 and TIM-3 at the tumor relapse phase with flow cytometry (Fig. S3E). Consistent with our findings in HNSCC patients, we did not find a correlation between NKG2A expression on CD8 T cells with other inhibitory receptors in untreated tumors (Fig. 3E). Vaccination promoted a high level of co-expression, especially at later time points (Fig. 3E). A stable receptor profile was again observed for NK cells and an increase in the TIM-3+ subset of CD4 T cells was found (Fig. 3E). Together, we concluded that expression of inhibitory receptors is highly dynamic on intratumoral CD8 T cells and associated with loss of tumor control.

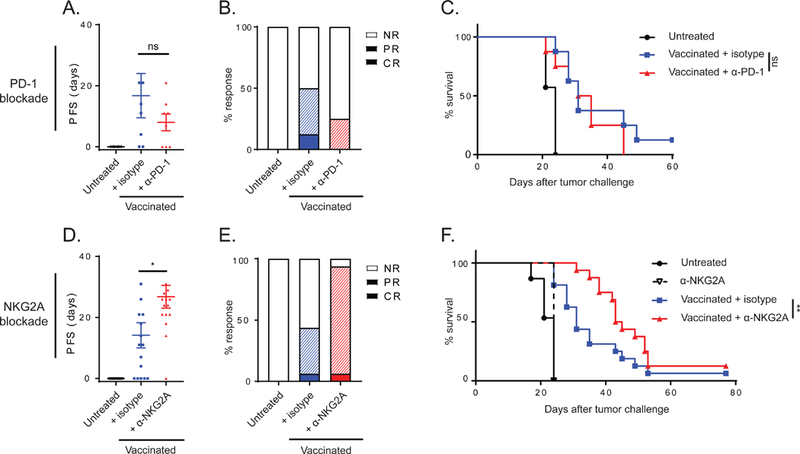

NKG2A blockade, but not PD-1 blockade, delays tumor relapse after peptide vaccination

The results on expression of inhibitory receptors on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes prompted us to provide PD-1 or NKG2A-blocking antibodies in the TC-1 mouse model from day 18 onwards, which marks the time of relapse. Unexpectedly, we did not observe any advantage of PD-1 blocking antibodies in combination with the vaccine, even though this receptor was detected on T cells in the tumors (Fig. 4A-C and S4A). In contrast, blockade of NKG2A profoundly improved the tumor response (Fig. 4D-F and S4B). The progression-free survival time doubled in mice that received the NKG2A blockade and, moreover, nearly all mice showed a complete or partial regression response according to RECIST criteria, resulting in a significant delayed tumor outgrowth (Fig. 4D-F). NKG2A blockade alone was not effective in this tumor model (Fig. 4F), suggesting a need for an inflammatory tumor environment such as mediated by peptide vaccination. We confirmed that the applied mouse version of the rat mAb anti-NKG2A, 20d5 (Vance et al., 1999) did actually mask the receptor on immune cells in the tumor without depleting cell subsets in vivo (Fig. S4C-D). NKG2A blockade seemed to enhance early immune cell influx in the tumor (Fig. S4E) and to increase the coexpression of CD94, PD-1 and TIM-3 on CD8 T cells in the tumor at the early relapse phase (Fig. S4F-G). This was not found for NK cells (Fig. S4F-G). These results indicated an empowering impact of NKG2A blockade during relapse on immune-mediated control of virus-induced tumors.

Figure 4: NKG2A blockade, but not PD-1 blockade, delays tumor relapse after peptide vaccination.

(A) Progression free survival (PFS) time of mice bearing TC-1 tumors treated with vaccination and PD-1 blocking antibody. Means and SEM during the relapse phase and (B) therapy response rates according to RECIST criteria are plotted (NR, no response; PR, partial response; CR, complete response). (C) Survival curves of this experiment (n=8 per group). (D) PFS time of mice bearing TC-1 tumors treated with vaccination and NKG2A blocking antibody. Means and SEM during the relapse phase, (E) therapy response rates and (F) survival curves (n=16 per group). One-way ANOVA test (A and D) and log-rank test (C and F) were used for statistical analyses. See also Figures S4 and S5.

To substantiate these results with non-viral tumors, we examined NKG2A blockade in the MC38 colon carcinoma model (Fig. S5). Therapeutic vaccination with point-mutated neoantigenic peptides and CpG as adjuvant resulted in detectable peptide-specific CD8 T cells in blood, but hardly prevented tumor outgrowth (Fig. S5A-C). In contrast to the TC-1 tumor model, frequencies of NKG2A+ CD8 T cells in the tumors were already high in untreated tumors and not further increased upon vaccination (Fig. S5D). Despite that all mice eventually succumbed due to progressive tumor outgrowth, survival time for NKG2A blockade combination therapy was significantly enhanced compared to vaccination alone (Fig. S5B-C). Together, these results suggested that NKG2A restrains efficacy of tumor control by CD8 T cells after vaccination.

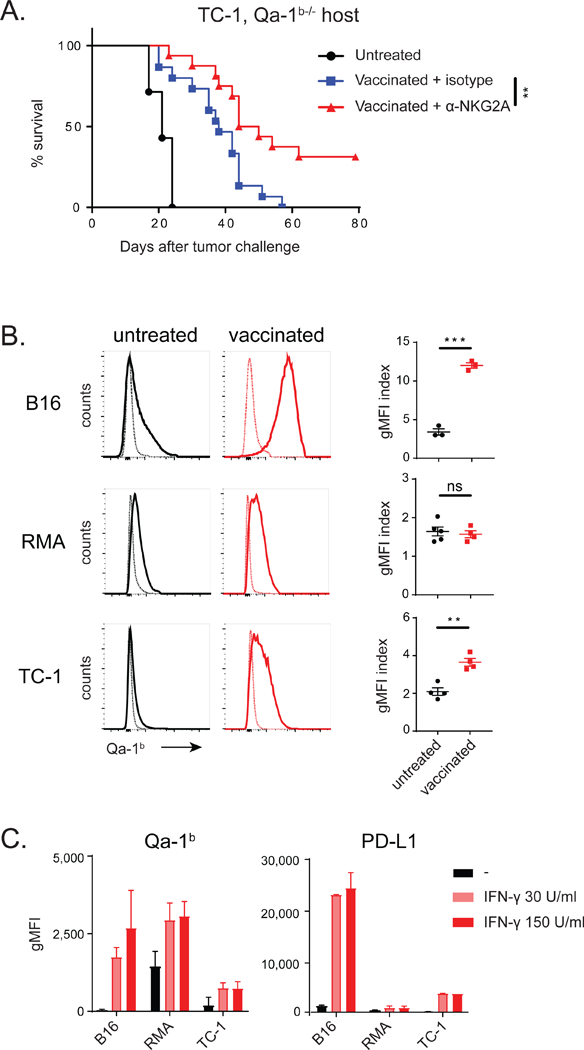

Inflammation induces Qa-1 expression on tumor cells

The heterodimer receptor NKG2A/CD94 selectively binds the non-classical MHC molecule Qa-1b, the mouse ortholog of HLA-E. Although Qa-1b is ubiquitously expressed in most body tissues, like conventional MHC class I, the protein cell surface display is rather low in most epithelial cell types. Protein expression is even hardly detectable on in vitro cultured tumor cell lines, whereas antigen- presenting cells, like dendritic cells and B-cells, express high levels (Doorduijn et al., 2018). We therefore examined if Qa-1b on host cells was a requisite for NKG2A blockade therapy and performed treatment experiments in Qa-1b-deficient mice bearing Qa-1b-positive TC-1 tumors (Fig. 5A and S6A). The beneficial effect of NKG2A blockade was still observed in Qa-1b-deficient mice, as part of the animals showed long-term survival and did not relapse. These data suggested that Qa-1b expression on stromal and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment was dispensable for NKG2A blockade therapy, but that Qa-1b on tumor cells was essential.

Figure 5: Inflammation induces Qa-1b expression on tumor cells.

(A) Vaccination with synthetic long peptide in Qa-1b-knockout mice bearing TC-1 tumors. Survival curves from two pooled independently performed experiments are shown and analysed by log-rank test (n=16 per group). (B) Qa-1b expression on B16, RMA and TC-1 tumor cells in vivo. Thin lines represent control staining of tumor cells. Index of geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) (Qa- 1b staining divided by control staining) and SEM, analysed with Student’s t-test. (C) Expression of Qa- 1b and PD-L1 on B16, RMA and TC-1 tumor cells in vitro after incubation with recombinant interferon-γ (IFNƔ). gMFI and SD of 2 pooled experiments. See also Figure S5 and S6.

Surface Qa-1b protein levels on in vitro cultured tumor cells is hardly detectable and we thus analysed its levels on TC-1 and MC38 tumor cells directly ex vivo. Whereas tumor cells from untreated mice displayed some Qa-1b, peptide vaccination increased these levels (Fig. 5B and S5E). Similar peptide vaccination protocols in two other mouse tumor models (B16 melanoma and RMA lymphoma) corroborated this result (Fig. 5B). Expression regulation of Qa-1b is poorly understood and we examined if supernatants of different cell types present in the tumor microenvironment, such as fibroblasts, macrophages and T cells, would induce Qa-1b expression in cultured B16 melanoma cells (Fig. S6B). Supernatant of activated T cells was very potent in Qa-1b upregulation (Fig. S6B-C) and, although multiple cytokines were present in this supernatant, blockade of the IFN-γ receptor on B16 cells completely abrogated Qa-1b induction (Fig. S6D). Indeed, recombinant IFN-γ was capable to induce expression of Qa-1b on the epithelial tumor lines B16 and TC-1, in a comparable way as it upregulated PD-L1 and the classical MHC class I molecule Db (Fig. 5C and S6E). RMA lymphoma cells displayed constitutive high levels, but these were also increased by IFN-γ. Interestingly, several other mouse epithelial tumor cell lines responded comparably to IFN-γ, except MC38, which did not respond to this cytokine in vitro, but still highly upregulated Qa-1b after transplantation in mice (Fig. S5E), suggesting that other environmental cues were involved.

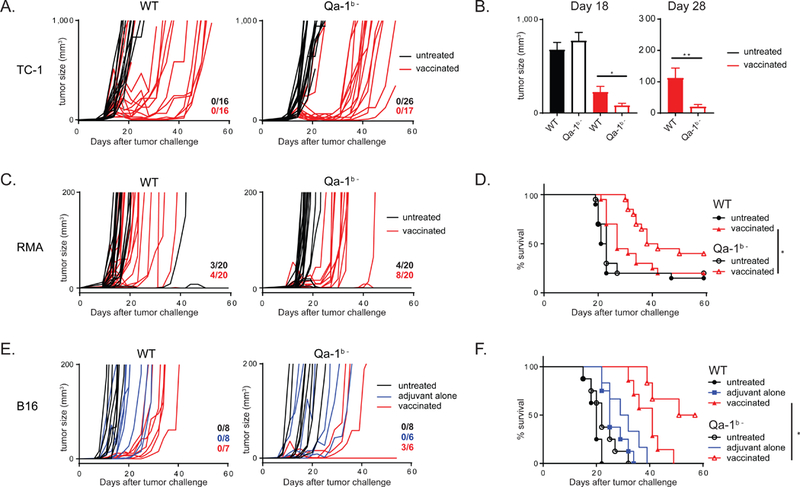

Genetic knockdown of Qa-1b in tumors enhances peptide vaccination therapy

Finally, we generated genetic knockdown cell lines for the gene encoding Qa-1b using CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing (Fig. S7A). In the TC-1 model, Qa-1b-deficient tumor cells were more sensitive for peptide vaccination-induced remission (Fig. 6A-B and S7B-D). Tumor regressions were deeper and were longer maintained, leading to longer progression-free survival and smaller tumors at later time points. Peptide vaccination in the RMA lymphoma model was also significantly better for Qa-1b- deficient cells compared to wild type tumor cells (Fig. 6C-D and S7E-F). Approximately half of the mice successfully eradicated their lesions and outgrowth in the other mice was clearly delayed.

Figure 6: Genetic knockdown of Qa-1b in tumors enhances peptide vaccination therapy.

(A) Outgrowth of wild type TC-1 tumors (WT) and Qa-1b-knockout TC-1 tumors (Qa-1b-). Each line represents an individual mouse. Numbers indicate fraction of tumor-free animals at day 60. (B) Mean and SEM of tumor sizes. Student’s t-test. (C) Outgrowth of wild type RMA tumors (WT) and Qa-1b-knockout RMA tumors (Qa-1b-). (D) Survival plots of these data from two pooled independently performed experiments with similar outcome, long-rank test. (E) Outgrowth of wild type B16 tumors (WT) and Qa-1b-knockout B16 tumors (Qa-1b-). (F) Survival plots of these data, logrank analysis. See also Figure S7.

Finally, deletion of Qa-1b in B16 melanoma model also rendered the tumor cells more vulnerable to vaccine-induced T cell responses (Fig. 6E-F and S7G-H). The vaccine-induced CD8 T cell responses were comparable in mice bearing wild type or Qa-1b-deficient tumors (Fig. S7C, F, H), indicating that the systemic anti-tumor immunity was the same, but that the immune cells exhibited stronger tumoricidal effects.

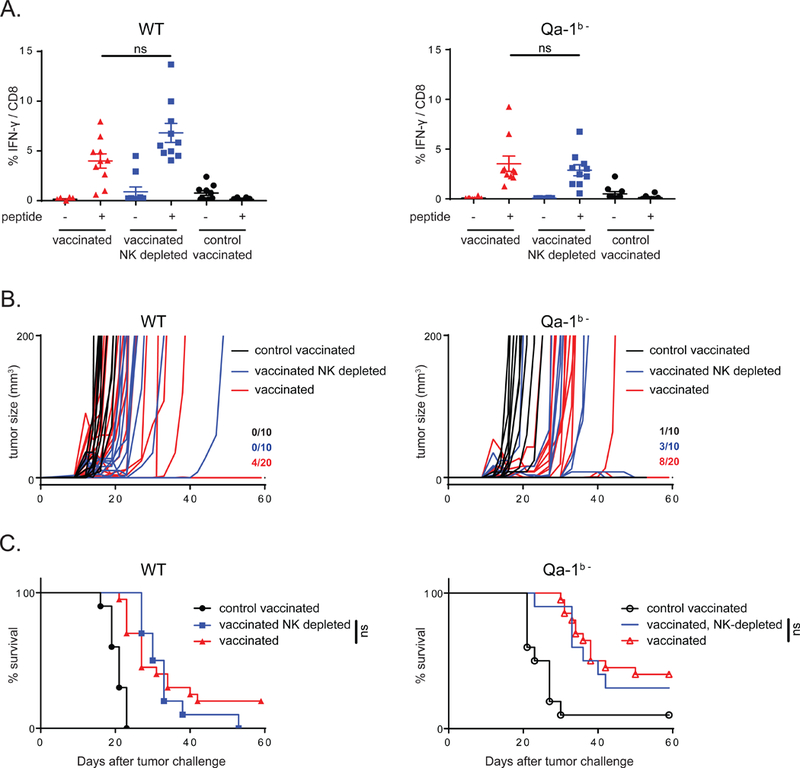

NK cells are dispensable for the enhanced peptide vaccination effect

We argue that the improved survival benefit in these mouse models was mainly T cell mediated, since CD8 T cells are essential for the therapeutic effect in these models (Ossendorp et al., 1998, van der Sluis et al., 2015, Ly et al., 2010, Ly et al., 2013) and cognate peptide antigens were required in the vaccines (Fig. 6E-F ‘adjuvant alone’ and Fig. 7A-C ‘control vaccinated’). Moreover, cancer vaccines strongly upregulated the expression of NKG2A on CD8 T cells, but not NK cells. Finally, depletion of NK cells did not abolish the beneficial effect on survival (Fig. 7B-C and S3C-D).

Figure 7: NK cells are dispensable for the enhanced peptide vaccination effect.

(A) Mice were inoculated with WT RMA tumors or Qa-1b- tumors and vaccinated with synthetic long peptides or control long peptide. Vaccine-induced CD8 T cell responses were measured in blood using intracellular cytokine staining. Student’s t-test for statistical analysis. (B) Tumor outgrowth plots depicting RMA tumor outgrowth in individual mice in three different treatment groups. Numbers indicate fraction of tumor-free animals at day 60. (C) Survival curves of these mice (n=10 to 20 mice per group). No statistical difference was observed using log-rank analysis when NK cells were depleted.

Taken together, these data imply an important restraining role of the NKG2A/Qa-1b axis for therapeutic cancer vaccines, mediated via an increased NKG2A expression on CD8 T cells in the tumor and induction of Qa-1b on tumor cells. Blockade of this axis can potently improve efficacy of therapeutic cancer vaccines.

Discussion

Our study revealed a negative feedback of cancer vaccines in the tumor microenvironment via induction of the inhibitory receptor NKG2A on CD8 T cells and the increased expression of its ligand on tumor cells. Interruption of NKG2A signalling by blocking antibodies or genetic deletion of the gene coding for its ligand Qa-1b, the mouse ortholog of HLA-E, strongly potentiated the efficacy of cancer vaccines in four mouse tumor models. The immune inhibitory NKG2A/HLA-E axis is likely to have a similar role in cancer patients as we found NKG2A to be expressed on a sizeable fraction of head and neck tumor-reactive CD8 T cells. Expression of the NKG2A by human tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes was previously described in untreated samples of other cancer types (Sheu et al., 2005, Gooden et al., 2011, van Esch et al., 2015). Importantly, we now show that the inhibiting NKG2A/HLA-E axis constitutes an adaptive resistance mechanism in response to (vaccine-induced) activated T-cell immunity in the microenvironment (Sharma et al., 2017). This counter response by tissues plausibly protects from overwhelming immune-mediated damage via cytolytic killer cells, including CD8 T cells and NK cells, and high local release of IFNγ (Zhou et al., 2007). Similar findings have been reported for the ligand of PD-1, which is also induced by interferons (Abiko et al., 2015).

Although the NKG2A/HLA-E axis was originally described to impact NK cell function, we argue that these innate lymphocytes only marginally contribute to our combination protocol of therapeutic vaccines and blockade of this receptor. First, depletion of NK cells did not affect the tumor control. Second, vaccination protocols with control antigens failed to induce tumor-specific CD8 T cells and tumor control, despite allowing NK cell activation via adjuvant. Third, our earlier work demonstrated that these cancer vaccines depended on CD8 T cells (van der Sluis et al., 2015, Ossendorp et al., 1998, Ly et al., 2010, Ly et al., 2013). Finally, this central role of NKG2A on CD8 T cells has been reported in mouse models of viral infections (Zhou et al., 2007, Rapaport et al., 2015, Ely et al., 2014, Moser et al., 2002). However, this does not exclude a contribution of NK cells to NKG2A blockade therapy in the context of checkpoint therapy, as others demonstrated in two lymphoma models that the responses were partly abolished when NK cells were depleted (André et al., 2018).

One important difference with the conventional PD-1 and CTLA-4 immune inhibitory checkpoints is the lineage-selective expression of NKG2A, which is predominantly present on cytolytic lymphocytes. In contrast to PD-1 and CTLA-4, NKG2A is virtually absent on CD4 T helper cells and the small subset that did stain in our set of human head and neck carcinomas might represent cytotoxic T helper cells, which represent a distinct subset with dedicated precursors (Patil et al., 2018). Display of NKG2A on NK cells was frequently found, especially in the tumor environment, and was hardly influenced by cancer vaccines or immune-reactive environments. In contrast, these conditions did lead to higher proportions of NKG2A+ CD8 T cells in the tumor, implying a dynamic regulation in these lymphocytes. The observation that high frequencies of NKG2A+ CD8 T cells were mainly found in cancer samples of patients and mice with active local immunity, suggests that NKG2A expression reflects recent activation, which is in line with literature showing that TCR triggering is required for the induction of NKG2A on CD8 T cells (Gunturi et al., 2005).

Our co-expression analyses of inhibitory receptors on CD8 T cells revealed that NKG2A display did not parallel that of PD-1, TIGIT, TIM-3 and LAG-3. The other inhibitory receptors were approximately evenly distributed among NKG2A-positive and -negative subsets. Interestingly, PD-1 blockade did not improve vaccination therapy in our TC1 model, whereas NKG2A blockade was successful (Fig. 4). These findings provide insight in the distinct cellular mechanisms underlying NKG2A versus PD-1 blockade therapy, as they might target different T cell subsets. Indeed, such differences in mode-of- action was described for the two FDA-approved antibodies to CTLA-4 and PD-1 (Wei et al., 2017). PD-1/PD-L1 blockade therapy is a first line treatment in an increasing number of cancer types and therefore combination with NKG2A mAb was tested in the PD-1/PD-L1-responsive MC38 mouse colon tumor model. Intriguingly, the addition of NKG2A mAb did not improve the therapeutic efficacy of PD-1 or PD-L1 mAbs, in contrast to addition to a synthetic peptide vaccine in this model (Fig. S5). The lack of therapeutic synergy between NKG2A and PD-1/PD-L1 in this colon model is not fully understood yet, but might be related to the fact that these inhibitory receptors are exhibited on an overlapping subset of intratumoral CD8 T cells and that NK cells are dispensable. Importantly, the combination of PD-L1 and NKG2A blockade was shown to be successful in two mouse lymphoma models (A20 and RMA.Rae1), which were controlled by CD8 T cells in conjunction with NK cells (André et al., 2018). The additional employment of anti-NKG2A-enabled NK cells might explain the strong efficacy of this NKG2A and PD-L1 checkpoint combination in these lymphoma models.

The NKG2A targetable T cell subset in cancers was positive for the tissue-resident marker CD103 and multiple NK-related receptors and markers of early effector cells (Fig. 2). NKG2A expression was found to be inducible in T cells by TCR triggering in combination with tissue-released cytokines like IL-15 and TGFP (Gunturi et al., 2005, Bertone et al., 1999, Sheu et al., 2005). Indeed, NKG2A expression was recently also reported on T cells from normal lung tissues, where they were poised for rapid responsiveness (Hombrink et al., 2016). In combination with the fact that CD103+ T cells have been associated with good clinical prognosis in multiple cancers (Webb et al., 2014b, Komdeur et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2016, Bosmuller et al., 2016, Webb et al., 2014a), these findings portrays the NKG2A-positive CD8 T cell subset as tissue-residing lymphocytes with immediate effector functions kept in check by their inhibiting receptors, such as NKG2A.

The humanized IgG4 antibody Monalizumab, specific for NKG2A, is currently under evaluation in several clinical trials in combination with other conventional cancer treatments. Recent clinical data suggest that NKG2A blockade might enhance the Cetuximab-induced responses in patients with head-and neck carcinomas (André et al., 2018) and we anticipate that it will also empower therapeutic cancer vaccines.

Online Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RECOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Thorbald van Hall (T.van_hall@lumc.nl).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

HNSCC patient cohort (TCGA)

Gene expression profiles (RNA-seq) and clinical data for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (n=419) from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) were downloaded via the GDC data portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). In this cohort, 75 HPV16 positive samples had been detected. Detail on data generation is available in the original study (Cancer Genome Atlas, 2015).

HNSCC patient cohort (Nashville)

Samples were obtained from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients undergoing surgery after signing informed consent. Collection and use of human tissues was approved by the medical ethical review board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center IRB #030062, NCT00898638.

OPSCC patient cohort (LUMC)

Patients with histological confirmed oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), which is a subset of HNSCC, were included after signing informed consent. The OPSCC patients were part of a larger observational study (P07–112) investigating the circulating and local immune response in patients with head and neck cancer (Heusinkveld et al., 2012) This study was approved by the local medical ethical committee of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) and in agreement with the Dutch law. The patients received the standard-of-care treatment which could consist of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, treatment with monoclonal antibody or combinations hereof.

CxCa patient cohort (LUMC)

Patients with histological confirmed cervical carcinoma (CxCa) were included after signing informed consent. The CxCa patients were enrolled in the CIRCLE study, which investigates cellular immunity against cervical lesions (de Vos van Steenwijk et al., 2010, Piersma et al., 2008). This was approved by the local medical ethical committee of the Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) and in agreement with the Dutch law. The patients received the standard-of-care treatment which could consist of surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, treatment with monoclonal antibody or combinations hereof.

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (L’Arbresle, France). Qa-1b−/− mice that harbour a targeted mutation of the H2-T23 gene (The Jackson Laboratory stock no. 007907), were kindly provided by Dr. M. Vocanson (Lyon, France) and bred in our own facility. T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice containing gp10025–33/H-2Db specific receptors (Overwijk et al., 2003) were a kind gift of Dr. N.P. Restifo (NIH, Bethesda, USA) and were bred to express the congenic marker CD45.1 (Ly5.1). All mice were housed in individually ventilated cages, maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions and used at 6–12 weeks of age. All mouse experiments were controlled by the animal welfare committee (IvD) of the Leiden University Medical Center and approved by the national central committee of animal experiments (CCD) under the permit number AVD116002015271, in accordance with the Dutch Act on Animal Experimentation and EU Directive 2010/63/EU.

Mouse tumor cell lines

The tumor cell line TC-1 expresses the HPV16-derived oncogenes E6 and E7 and activated Ras oncogene and were a gift from T.C. Wu (John Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA). The B16F10 melanoma cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC-CRL6475). The RMA cell line is a mutagenized derivative of the Rauscher MuLV-induced T-cell lymphoma RBL-5. The MC38 cell line is a chemically induced colon adenocarcinoma. All cells were derived from C57BL/6 mice and cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 8% FCS (GIBCO), glutamine and 2% penicillin/streptomycin (complete medium) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Cell lines were assured to be free of rodent viruses and Mycoplasma by regular PCR analysis. Authentication of the cell lines was done by antigen-specific T- cell recognition and cells of low passage number were used for all experiments.

METHOD DETAILS

Survival plots HNSCC patient cohort (TCGA)

The overall survival time was defined using the latest information. For survival analysis, the patients were dichotomized based on gene expression levels. The median cutpoints were determined to stratify patient into two groups (Hi and Lo). Kaplan Meier estimators of survival were used to visualize the survival curves. The log-rank test was used to compare overall survival between patients in different groups. P-values for the HiHi, HiLo, LoHi, and LoLo gene combination analysis were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. All analyses were performed using the statistical software environment R (package survival).

Flow cytometry HNSCC patient cohort (Nashville)

Fresh tumor samples were processed using miltenyi biotec human tumor dissociation kit and the Miltenyi GentleMACS Octo dissociator following manufacturer’s instructions. PBMC were collected from blood using Ficoll-Paque Plus, following manufacturer’s instruction. Single cell suspensions were stained and analysed by flow cytometry the same day the samples were collected using a BD FACSCelsta. The monoclonal antibodies used were against TIGIT (A15153G), CTLA-4 (BNI3), CCR7 (G043H7), CD127 (A019D5), CD45RO (UCHL1) and KLRG-1 (14C2A07). For ICS staining single cells suspensions were incubated with PMA/ionomycin (Cell stimulation cocktail, Invitrogen) and monensin (BioLegend) for 4 hours at 37°C Following activation, the cells were surface stained and then fixed for 15 minutes with IC fixation buffer (eBioscience). Following fix, cells were permeabilized with perm buffer (eBioscience) and intracellularly stained for IFN-γ (4S.B3), Perforin (B-D48) and Granzyme B (GB11).

Flow cytometry OPSCC patient cohort (LUMC)

Blood and tumor tissue samples were taken prior to treatment and handled as described previously (Welters et al., 2017). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were stored until use. HPV typing was performed on former fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor sections at the department of pathology at the LUMC. HPV-specific immune reactivity of TILs was determined in a 5-day proliferation assay (Welters et al., 2017): HPV type 16 negative HNSCC (HPV-, n=5), HPV16-positive tumors without ex vivo immune reactivity (IR-, n=5) and HPV16-positive tumors displaying ex vivo immune reactivity to HPV16 (IR+, n=8). The phenotype and composition of dispersed OPSCC and expanded TILs was analysed by flow cytometry. The monoclonal antibodies used were against CD3 (UCHT1), CD8 (SK1), CD56 (B159), CD4 (RPA-T4), CD94 (FAB1058F), TIM3 (F38–2E2), CD279/PD1 (EH12.2H7) and CD159a/NKG2A (Z199) from BD, R&D, BioLegend or Beckman-Coulter.

CyTOF analysis CxCa patient cohort (LUMC)

The phenotype of dispersed cervix carcinoma samples was analysed by high dimensional single cell time-of-flight mass cytometry (CyTOF) of 34 markers as described (Welters et al., 2017), with NKG2A-142Nd (Z199) replacing the CD34-142Nd antibody. Cluster analysis was performed independent from NKG2A expression and visualized in tSNE plots of pre-gated CD3+CD8 T cells. Expression ratios of different markers are based on the mean signal intensity (MSI) between compared populations.

In vivo experiments in mouse tumor models

For tumor inoculation, 100,000 TC-1, 100,000 B16F10, 1,000 RMA or 250,000 MC38 tumor cells were injected s.c. in the flank of mice in 200 μL PBS/0.1% BSA. Tumors were measured twice a week with a calliper. When a palpable tumor was present, mice were split into groups with similar tumor size and were treated with immunotherapy. Mice were sacrificed when tumors reached a volume of 1000 mm3

TC-1 tumors were treated with a peptide vaccine on day 8 after tumor inoculation with 150 μg of the HPV16 E743–77 peptide (GQAEPDRAHYNIVTFCCKCDSTLRLCVQSTHVDIR) emulsified at a 1:1 ratio with Incomplete Freunds Adjuvant (IFA; Difco) s.c. in the contralateral flank (van der Sluis et al., 2015). NKG2A-blocking antibody (M020D5) was produced by Innate Pharma (Marseille, France) and is an engineered variant of the rat lgG2a anti-mouse NKG2A/C/E (clone 20D5), comprising mouse Ig constant domains with mutations to inactivate Fc receptor and complement binding. Isotype control antibody contained the same modifications. The PD-1 blocking antibody was purchased from BioXCell (clone RMP1–14, InvivoPlus). Antibodies were applied at a dose of 200 μg i.p. or i.v. at days 18, 22, and 29. Vaccine-induced T cell responses were measured by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) and flow cytometry. Peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) samples were collected 6 days after vaccination and incubated overnight with the short HPV16 E749−57 peptide in the presence of 1 μg/ml GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences). Antibodies to CD8α (53–6.7) and IFN-γ (XMG1.2) from Biolegend were used for stainings. For NK cell depletion, mice were injected i.p. with 100 μg of the NK-cell depleting monoclonal antibody clone PK136 (BioXCell, InvivoPlus) on day 7 and then every 3–4 days. Therapy response rates according to RECIST criteria: NR: no response, PR: partial response, defined as a decrease in tumor size, at least 2 consecutive measurements and minimal 30% of lesion, CR: complete response, defined as a complete disappearance of a previous tumor. Progression free survival (PFS) defined as the duration of response from the day that tumor reaches maximum size until the day that tumor exceeds maximum size again.

MC38 tumors were treated with two vaccinations on days 6 and 13 with a mix of 3 peptides, based on the natural elongated sequences of previously published mutant neo-antigens optimized for solubility (Adpgk: PVHLELASMTNMELMSSIVHQ, Dpagtl: EAGQSLVISASIIVFNLLELEGDYR, Repsl: ELFRAAQLANDVVLQIMEL) (Yadav et al., 2014). Peptides, 50 μg each, were mixed with 20 μg CpG (ODN 1826, Invivogen) and injected s.c. in the tail-base region in 50 μl PBS. To analyse efficacy of vaccination, PBL samples were collected from tail veins at 6 days after the last vaccination. Percentages of vaccine-induced CD8 T cells was determined by peptide-MHC tetramers and flow cytometry. All peptides and tetramers were produced in our own facility. Blocking antibodies to NKG2A (M020D5) and PD-1 (RMP1–14) were provided i.p. or i.v. at a dose of 200 μg at days 9, 16, 23 and 30.

B16F10 tumors were treated with a combination of adoptive transfer of tumor-specific (pmel) TCR transgenic T cells and peptide vaccination, as described previously (Ly et al., 2010). Lymphocytes from spleen and lymph nodes of naïve CD45.1 -positive pmel mice were isolated and enriched for T lymphocytes by nylon wool. Enriched spleen cells (3 × 106 cells) were adoptively transferred by injection into the tail vein at day 4. Mice were immunized at day 5 and 12 by s.c. injection of 150 μg peptide comprising the human gp10020–39 sequence (AVGALKVPRNQDWLGVPRQL) in PBS. 60 mg of Aldara cream containing 5% imiquimod was simultaneously applied on skin at the shaved injection site. At days 12 and 13, 600,000 IU human recombinant IL-2 (Novartis) was supplied. Vaccine- induced pmel T cell responses were measured at day 18 by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) and flow cytometry. Peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL) samples were collected 6 days after vaccination and incubated overnight with the 9-mer gp10025–33 peptide EGSRNQDWL in the presence of 1 μg/ml GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences) using antibodies against CD8α (53–6.7), CD45.1 (A20) and IFN-γ (XMG1.2) from Biolegend and analysed by flow cytometry.

RMA tumors were treated with a single vaccination on day 7 with 20 nmol of the Murine Leukemia virus Env-encoded CD4 T cell epitope EPLTSLTPRCNTAWNRLKL and 50 nmol of the Gag-encoded CD8 T cell epitope CCLCLTVFL (Kleinovink et al., 2016) mixed with 20 μg CpG (ODN 1826, Invivogen), in 50 μL PBS s.c. in the tail-base region. Efficacy of vaccination was measured in PBL 7 days after vaccination by peptide-specific intracellular cytokine production after overnight incubation with the peptides in the presence of golgi-plug (BD Biosciences). Antibodies to CD4 (RM4–5), CD8α (53–6.7) and IFN-γ (XMG1.2) were used from Biolegend and analysed by flow cytometry. For NK cell depletion, mice were injected i.p. with 100 μg of the NK-cell depleting monoclonal antibody clone PK136 (BioXCell, InvivoPlus) on day 7 and then every 3–4 days.

Flow Cytometry on mouse tumor samples

For analysis of tumor-infiltrating populations, mice were sacrificed at indicated time points and tumors were harvested, disrupted in small pieces, and incubated with Liberase TL (Roche) in IMDM for 15 minutes at 37°C. Single-cell suspensions were prepa red by mincing the tumors through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). Cells were first incubated with live/dead fixable yellow dead cell stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific, L34959) in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature. Subsequently, cells were washed and resuspended in staining buffer (PBS + 0.5% BSA + 0.05% sodium azide) supplemented with 2.4G2 Fc block for 15 minutes on ice. Subsequently, cells were incubated with monoclonal antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. Antibodies used were against CD3 (145–2C11), NK1.1 (pk136), CD4 (RM4–5), TIM3 (RMT3–23), CD8α (53–6.7), CD45.2 (104), CD94 (18d3), NKG2A (16a11), PD-1 (RMP1–30) and LAG3 (eBioC9B7W) from BD, BioLegend or eBioscience. Staining of Qa-1b was performed in a 2 step procedure with biotin-labelled anti-Qa-1b (clone 6A8.6F10.1 A6) followed by streptavidin-APC. Samples were acquired on a BD Fortessa flow cytometer, and results were analyzed using the FlowJo software (TreeStar).

In vitro stimulation of tumor cells

Tumor cell lines were plated at day −1 in 24 wells plates at a cell density of 20.000/well in 2 ml of culture medium. At day 0, indicated concentration of recombinant IFN-γ (Biolegend) or cell culture supernatants were added to the cells. After 48 hours, cells were harvested and stained with monoclonal antibodies to Qa-1b (6A8.6F10.1 A6), Db (28–14-8) and PDL-1 (MIH5) for 30 minutes on ice in flow cytometry staining buffer. Fibroblast and tumor cell supernatants were generated by collecting conditioned medium from R1 cells and KPC tumor cells, respectively. Macrophage supernatants were generated from M-CSF mediated bone-marrow derived macrophages stimulated overnight with LPS. Splenocyte supernatant was generated by incubation with 5 μg/ml Concanavalin A (type IV, Sigma C 2010) and 5 ng/ml Phorbol myristate acetate (Sigma P 8139) and collecting supernatants during 3 subsequent days. CD3-negative and -positive cell fractions were generated with mouse CD3ɛ MicroBead kit (Milteny Biotec). Experiments with blocking antibodies were performed by pre-incubation for 1h with rat anti-mouse IFN-ƔR (CD119) (clone GR-20, BioXcell) or isotype control (clone 2A3, BioXCell) followed by incubation with 1.5% splenocyte supernatants for 24 hours.

Generation of Qa-1b knockout cells

Qa-1b-knockout tumor cell lines were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. sgRNA’s targeting the Qa-1b gene H-2T23 were designed using an online tool (http://crispr.mit.edu). The sgRNA sequence (5’-GGCTATGTCATTCGCGGTCC-3’) was cloned into a sgRNA expression vector (Addgene 41824) using Gibson In-fusion. Target cells were co-transfected with the sgRNA-Qa1b expression vector and a plasmid containing Cas9 WT (Addgene 41815) using lipofectamine 2000. Qa-1b knockout was confirmed by pre-incubating targeted cells for 48h with 30 IU/ml IFN-γ and analysing Qa-1b surface expression by flow cytometry. Qa-1b- cells were FACS sorted at least two times until a pure Qa-1b- cell line was established. FACS sorted Qa-1b+ cells from the same culture were used as control (WT).

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis

The non-parametric log-rank test (Mantel-Cox test) was used to compare the survival distribution of groups of patients or mice. Additional statistical methods are stated in the figure legends. In all cases a P-value of 0.05 and below was considered significant (*), P<0.01(**) and P<0.001 (***) as highly significant.

Supplementary Material

(A) Expression of KLRC1 (the gene coding for NKG2A) measured by RNAseq on sorted populations of lymphocytes from head and neck carcinoma patients. Expression values shown are transcripts per million cells (TPM). Student’s t-test for statistical analysis. (B) CD8 T cells from head and neck squamous cell carcinoma biopsies were analysed for expression of NKG2A and CD94 by flow cytometry before and after ex vivo expansion with cytokines. Paired Student’s t-test for statistical analysis. (C) Kaplan Meier survival plots of HPV16-negative HNSCC (n=419) from the publicly available TCGA database, grouped according to high and low gene expression CD8, KLRC1 (coding for NKG2A), HLA-E and NCR1 (coding for NKp46). Numbers of patients for each group and log-rank test P-values are given. (D) CD8 T cells from HNSCC biopsies were analysed for co-expression of NKG2A with PD-1 or TIM-3 by flow cytometry after ex vivo expansion with cytokines. (E) Co-expression of intracellular IFNγ, perforin and GranzymeB with NKG2A on CD8 T cells from HNSCC after 4h stimulation with PMA/Ionomycin directly ex vivo. (F) Representative flow cytometry plot and (G) Box-whisker plots of CD8 T cells from HNSCC samples for co-expression of NKG2A with CD103 after ex vivo expansion with cytokines. Student’s paired t-test was used for statistical analyses.

(A-E) Mass cytometry (CyTOF) measurements of CD8 T cell samples with 36 markers is plotted for 5 different patients (with their reference number in brackets). Cluster analyses was performed on CD3+CD8 T cells and visualized by viSNE pots. A manual box was drawn on the grouped NKG2A+ cluster to visualize these cells for expression of all other markers. Indicated parameter is highlighted. (F) Summary of CyTOF analysis for intratumoral NK cells, showing preferential display of markers by NKG2A+ NK cells versus NKG2A- NK cells. (G-L) Individual cluster analysis per patient from CyTOF measurements with 36 markers. Patient reference number is in brackets. Cluster analyses visualized by viSNE pots. Indicated parameter is highlighted. These biopsies were from HPV-positive cervical carcinoma patients.

(A-B) Mice bearing TC-1 tumors were left untreated (black) or treated with synthetic long peptide vaccine at day 8 (grey, red and blue). At indicated time points after tumor inoculation, tumors were removed, dispersed and analysed by flow cytometry. Means and SEM of absolute numbers of CD4 T cells, CD8 T cell or NK cells are depicted for 3–4 mice per group. One way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used for statistical analysis. (B) Frequencies of NKG2A positive lymphocytes in spleens at day 29 in tumor-bearing vaccinated mice. Proportions were calculated out of all NK, CD4 T and CD8 T cells, respectively. (C-D) Vaccination of TC-1 tumors does not require NK cells. Outgrowth of TC-1 tumors in time in the presence of PK136 antibodies that deplete NK cells and Kaplan Meier survival curves of these same mice. Log-rank analysis was used for survival curves. (E) Applied gating strategy for flow cytometry measurements to determine co-expression of inhibitory receptors NKG2A, PD-1 and TIM-3.

(A-B) TC-1 tumor outgrowth graphs for mice treated with synthetic long peptide vaccine in combination with PD-1 blocking antibodies (A) or NKG2A blocking antibodies (B). Mice were treated with antibodies from day 18 onwards. (C-D) In vivo saturation of blocking NKG2A antibodies was analysed by flow cytometry on lymphocytes from blood and tumor (TIL). (C) Representative plots on gated CD8 T cells and NK cells showing that the CD94 chain is still detectable by fluorescently labelled antibodies used in flow cytometry, while the NKG2A chain is masked by the in vivo applied blocking antibody, but not in mice receiving isotype control Ig. (D) Percentages of NKG2A-positive lymphocytes at different time points on CD8 T cells and NK cells in tumor samples at day 24 and 36 after tumor injection. Note that expression of NKG2A is not measured due to masking of the in vivo applied antibody. (E) Numbers of CD4 T cells, CD8 T cells and NK cells in TC-1 tumors after combination therapy analysed at indicated days. Means with SEM are shown of 3 mice per group. (F) Percentages of CD94, PD-1 and TIM-3 expressing tumor infiltrating CD8 T cells and NK cells in the different treatment groups. Means and SEM of 3–5 mice per group are depicted. (G) Venn diagrams of co-expression analyses of these inhibitory receptors on CD8 T cells and NK cells in the tumor at indicated time points.

Combination treatment of synthetic long peptide vaccination and NKG2A blocking antibodies in the MC38 colon carcinoma model. (A) CD8 T cell response to vaccination was measured via peptide/MHC tetramer staining in the blood at day 20 for the mutated neoantigens (peptides Adpgk and Reps1). Vaccine comprised long synthetic peptides and CpG adjuvant in PBS and was applied at day 6 and day 13. One way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. (B) Outgrowth of MC38 tumors and (C) survival curves of these mice are displayed. 12 mice per group from two independent experiments, analysed with log-rank test for statistical analysis. (D) Percentages of NKG2A+ and CD94+ cells of intratumoral CD8 T cells are shown in end stage tumors (n=3–4 mice/group). Note that NKG2A staining was low due to masking by blocking antibody injected during the experiment. One way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. (E) Ex vivo Qa-1 expression on MC38 tumor cells determined by flow cytometry. Index of geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) (Qa-1b staining divided by control staining) and SEM, analysed with Student’s t-test.

(A) Qa-1b knockout mice (H-2T23−/−) were injected with TC-1 tumor cells and treated with synthetic long peptide vaccine and blocking NKG2A antibodies. Untreated (black lines), vaccinated plus isotype control antibodies (blue lines) and vaccinated plus NKG2A blocking antibodies (red lines). Each line depicts tumor size over time in one mouse. Numbers refer to fraction of mice surviving at day 80. (B) Qa-1b expression on B16 cells incubated in vitro for 48 hours with different conditioned culture media from: control medium, fibroblasts, splenocytes (stimulated with PMA-ConA), LPS-stimulated M-CSF cultured bone-marrow macrophages or TGFβ-producing pancreatic tumor cells. Pooled data from two out of four independent experiments with similar outcome is shown. Geometric mean fluorescence intensity (gMFI) is shown. Student’s t-test for statistical analyses. (C) Qa-1b expression on B16 cells incubated in vitro with 25% supernatant from mitogen-stimulated CD3-negative and CD3-positive spleen subsets. (D) Qa-1b expression on B16 cells incubated with 1.5% activated CD3- positive spleen supernatant in the presence of blocking antibody to the IFNγ-receptor (IFNγR) or isotype control. Means and SD of 2 pooled experiments is shown. Two way ANOVA for statistical analyses. (E) Flow cytometry of Db expression on B16, RMA and TC-1 cells in vitro cultured for 48 hours with recombinant IFNγ.

Flow cytometry analysis of Qa-1b expression on tumor cell lines TC-1, RMA and B16 before (upper panel) and after (lower panel) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of the Qa-1b gene H-2T23, either untreated (black) or after stimulation with recombinant IFNγ (red). Dotted lines represent control staining. Cells were sorted by FACS at least twice after CRIPR/Cas9 treatment before used in experiments. (B) Schematic representation of the treatment protocol in the TC-1 tumor model. ICS means intracellular cytokine staining in blood samples to measure vaccine-induced T cell responses. (C) Vaccine-induced CD8 T cell responses are measured in blood. Frequencies of peptide-specific responses animals bearing wild type tumors (WT) and Qa-1b-knockout tumors (Qa-1b-) are plotted. Student’s t-test for statistical analysis. (D) Efficacy of vaccination therapy against wild type TC-1 (WT) and Qa-1b-knockout TC-1 (Qa-1b-) tumors. Therapy response rates according to RECIST criteria are shown: NR, no response; PR: partial response, CR: complete response. Mean progression free survival time (PFS) in days are depicted above the bars per group (n=16). Data are from two pooled experiments with similar outcome. (E-G) Treatment scheme, vaccine-induced CD8 T cell responses and therapy responses in the RMA lymphoma model. ICS in (F) was performed after brief in vitro stimulation with peptide. Numbers in (G) represent fraction of surviving mice at day 60. (H-J) Treatment scheme, vaccine-induced CD8 T cell responses and therapy responses in the B16 melanoma model. ACT means adoptive cell therapy of naïve TCR-transgenic CD8+ pmel T cells. Numbers in (J) indicate fraction of tumor-free animals at day 60.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| NKG2A – blocking antibody (20D5) | Innate Pharma | N/A |

| PD-1 – blocking antibody (clone RMP1–14, InvivoPlus) | BioXCell | BP0146; RRID: AB_10949053 |

| NK1.1 – depletion antibody (clone PK136, InvivoPlus) | BioXCell | BP0036; RRID: AB_1107737 |

| InVivoMAb anti-mouse IFNγR (CD119) (GR-20) | BioXcell | BE0029; RRID: AB_1107576 |

| Purified CD16/CD32 (2.4G2) | BD Pharmingen | Cat#: 553141; RRID: AB_394656 |

| NKG2A – PE (16a11) | eBioscience | Cat#: 12–5897–81; RRID: AB_466024 |

| CD94 – V450 (18d3) | eBioscience | Cat#: 48–0941–82; RRID: AB_11218905 |

| PD-1 – FITC (RMP1–30) | eBioscience | Cat#: 11–9981–82; RRID: AB_465467 |

| TIM-3 – APC (RMT3–23) | BioLegend | Cat#: 119706; RRID: AB_2561656 |

| Lag-3 – PE-Cy7 (eBioC9B7W) | eBioscience | Cat#: 16–2231–81; RRID: AB_494125 |

| CD45.1 – APC (A20) | BioLegend | Cat#: 110714; RRID: AB_313503 |

| CD45.2 – APC-Cy7 (104) | eBioscience | Cat#: 47–0454–82; RRID: AB_1272175 |

| CD3 – PE-CF594 (145–2C11) | BD Horizon | Cat#: 562286; RRID: AB 11153307 |

| CD4 – BV605 (RM4–5) | BioLegend | Cat#: 100547; RRID: AB_11125962 |

| CD8 – AF700 (53–6.7) | eBioscience | Cat#: 56–0081–82; RRID: AB_494005 |

| NK1.1 – BV650 (PK136) | BD Horizon | Cat#: 564143 |

| Qa-1 – biotin (6A8.6F10.1A6) | BD Pharmingen | Cat#: 559829; RRID: AB_397345 |

| Streptavidin – APC | eBioscience | Cat#: 17–4317–82 |

| Db – PE (28–14–8) | BioLegend | Cat#: 114507; RRID: AB_313588 |

| CD274 (PDL1) – BV421 (MIH5) | BD Horizon | Cat#: 564716 |

| IFN-γ – APC (XMG1.2) | BioLegend | Cat#: 505810; RRID: AB_315404 |

| CD8α – PE (53–6.7) | BioLegend | Cat#: 100708; RRID: AB_312747 |

| CD3 – V450 (UCHT1) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 560365; RRID: AB_1645570 |

| CD8 – APC-Cy7 (SK1) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 348813 |

| CD56 – AF700(B159) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 557919; RRID: AB_396940 |

| CD4 – PE-CF594 (RPA-T4) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 562281; RRID: AB_11154597 |

| CD94 – FITC (131412) | R&D Systems | Cat#: FAB1058F; RRID: AB_2133132 |

| TIM-3 – BV605 (F38–2E2) | BioLegend | Cat#: 345017; RRID: AB_2562194 |

| CD279 (PD-1) – PE-Cy7 (EH12.2H7) | BioLegend | Cat#: 329917; RRID: AB_2159325 |

| CD159a (NKG2A) – PE (Z199) | Beckman-Coulter | Cat#: IM3291U; RRID: AB_10643228 |

| CD103 – BV605 (Ber-ACT8) | BD Biosciences | Cat#: 350218 |

| CD45RO – BV786 (UCHL1) | BioLegend | Cat#: 304234; RRID: AB_2563819 |

| CCR7 – Pacific Blue (G043H7) | BioLegend | Cat#: 353210; RRID: AB_10918984 |

| CD127 – AF488(A019D5) | BioLegend | Cat#: 351314; RRID: AB_10898315 |

| KLRG-1 – PE/Dazzle594 (14C2A07) | BioLegend | Cat#: 368608; RRID: AB_2572135 |

| Perforin – PerCP/Cy5.5 (B-D48) | BioLegend | Cat#: 353314; RRID: AB_2571971 |

| Granzyme B – FITC (GB11) | BioLegend | Cat#: 515403; RRID: AB_2114575 |

| IFN-γ – PE/Dazzle594 (4S.B3) | BioLegend | Cat#: 502546; RRID: AB_2563627 |

| CTLA-4 – PerCP/Cy5.5 (BNI3) | BioLegend | Cat#: 369608; RRID: AB_2629674 |

| TIGIT – PE/Dazzle594 (A15153G) | BioLegend | Cat#: 372716; RRID: AB_2632931 |

| CD45 – 89Y (HI30) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3089003B |

| CCR6 – 141Pr (G034E3) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3141003A; RRID: AB_2687639 |

| NKG2A – 142Nd (Z199) | Beckman Coulter | Cat#: IM2750; RRID: AB_131495 |

| C-Kit – 143Nd (104D2) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3143001B; RRID: AB_2687630 |

| CD11b – 144Nd (ICRF44) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3144001B; RRID: AB_2714152 |

| CD4 – 145Nd (RPA-T4) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3145001B; RRID: AB_2661789 |

| CD8a – 146Nd (RPA-T8) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3146001B; RRID: AB_2687641 |

| Nkp44 – 147Sm (P44–8) | BioLegend | Cat#: 325102; RRID: AB_756094 |

| CD16 – 148Nd (3G8) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3148004B; RRID: AB_2661791 |

| CD25 – 149Sm (2A3) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3149010B |

| IgM – 150Nd* (MHM88) | BioLegend | Cat#: 314527 |

| CD123 – 151Eu (6H6) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3151001B; RRID: AB_2661794 |

| TCRγ/δ – 152Sm (11F2) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3152008B; RRID: AB_2687643 |

| CD7 – 153Eu (CD7–6B7) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3153014B |

| CD163 – 154Sm (GHI/61) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3154007B; RRID: AB_2661797 |

| CD103 – 155Gd* (Ber-ACT8) | BioLegend | Cat#: 350202 |

| CRTH2 – 156Gd* (BM16) | BioLegend | Cat#: 350102; RRID: AB_10639863 |

| CD122 – 158Gd* (TU27) | BioLegend | Cat#: 339015; RRID: AB_2563712 |

| CCR7 – 159Tb (G043H7) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3159003A; RRID: AB_2714155 |

| CD14 – 160Gd (M5E2) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3151009B |

| KLRG-1 – 161Dy* (REA261) | Miltenyi Biotech | N/A customized order |

| CD11c – 162Dy (Bu15) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3162005B; RRID: AB_2687635 |

| CD20 – 163Dy* (2H7) | BioLegend | Cat#: 302343; RRID: AB_2562816 |

| CD’S’ – 164Dy (HP-3G10) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3164009B; RRID: AB_2687651 |

| CD127 – 165Ho (A019D5) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3165008B |

| CD8b – 166Er* (SIDI8BEE) | eBioscience | Cat#: 14–5273–82 |

| CD27 – 167Er (O323) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3167002B |

| HLA-DR – 168Er* (L243) | BioLegend | Cat#: 307651; RRID: AB_2562826 |

| CD45RA – 169Tm (HI100) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3169008B |

| CD3 – 170Er (UCHT1) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3170001B; RRID: AB_2661807 |

| CD2B – 171Yb* (CD2B.2) | BioLegend | Cat#: 302937; RRID: AB_2563737 |

| CD3B – 172Yb (HIT2) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3172007B |

| CD45RO – 173Yb* (UCHL1) | BioLegend | Cat#: 304239; RRID: AB_2563752 |

| NKp46 – 174Yb* (9E2) | BioLegend | Cat#: 331902; RRID: AB_1027637 |

| PD-1 – 175Lu (EH 12.2H7) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3175008B; RRID: AB_2687629 |

| CD56 – 176Yb (NCAM16.2) | Fluidigm | Prod#: 3176008B; RRID: AB_2661813 |

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Biological Samples | ||

| Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) | Vanderbilt University Medical Center | IRB #030062, NCT00B9B63B |

| Oropharyngeal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OPSCC) | Leiden University Medical Center | (Heusinkveld et al., 2012) (P07–112) |

| Cervical Carcinoma (CxCa) | Leiden University Medical Center | CIRCLE study (de Vos van Steenwijk et al., 2010) |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| H-2Db HPV16 E749−57 peptide (RAHYNIVTF) tetramer – APC | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| H-2Db MC38 Adpgk peptide (ASMTNMELM) tetramer – APC | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| H-2Db MC38 Dpagtl peptide (SIIVFNLL) tetramer – APC | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| H-2Db MC38 Repsl peptide (AQLANDVVL) tetramer – APC | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| LIVE/DEAD™ Fixable Yellow Dead Cell Stain Kit | Invitrogen™ | L34959 |

| Liberase™ TL Research Grade | Roche | 05401020001 |

| Concanavalin A (Type IV) | Sigma | C2010 |

| Phorbol myristate acetate | Sigma | P9139 |

| Recombinant IFN-γ | BioLegend | 57530B |

| GolgiPlug Protein transport inhibitor | BD Biosciences | 555029 |

| Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection Reagent | Invitrogen | 1166B027 |

| Permeabilization Buffer 10X | eBioscience | Cat#: 00-B333–56 |

| IC Fixation Buffer | eBioscience | Cat#: 00-B222–49 |

| Monensin Solution (1,000X) | BioLegend | Cat#: 420701 |

| Cell Stimulation Cocktail (500X) | Invitrogen | Cat#: 00–4970–93 |

| HPV16 E743–77 peptide (GQAEPDRAHYNIVTFCCKCDSTLRLCVQSTHVDIR) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| short HPV16 E749–57 peptide (RAHYNIVTF) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| human gp10020–39 peptide (AVGALKVPRNQDWLGVPRQL) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| gp10025–33 peptide (EGSRNQDWL) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| MC38 peptide Adpgk (PVHLELASMTNMELMSSIVHQ) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| MC38 peptide Dpagt1 (EAGQSLVISASIIVFNLLELEGDYR) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| MC38 peptide Reps1 (ELFRAAQLANDVVLQIMEL) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| RMA Env-encoded CD4 T cell epitope (EPLTSLTPRCNTAWNRLKL) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| RMA Gag-encoded CD8 T cell epitope (CCLCLTVFL) | Peptide synthesis facility of department IHB, LUMC | |

| human recombinant IL-2 (Proleukin® 18 × 106 IE) | Novartis | RVG 13354 |

| Aldara™ 5% crème (Imiquimod) | MEDA Pharma B.V | Cat#: 620362216 |

| CpG (ODN 1826) | Invivogen | Cat#: tlrl-1826 |

| Incomplete Freunds Adjuvant (IFA; Difco) | BD | Cat#: 263910 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Tumor Dissociation Kit, human | Milteny Biotec | 130–095–929 |

| gentleMACS™ Octo Dissociator | Milteny Biotec | 130–095–937 |

| mouse CD3ɛ MicroBead kit | Milteny Biotec | 130–094–973 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Firehose, The Broad Institute | https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| TC-1 | Provided by Prof. T.C. Wu (John Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA) | RRID: CVCL_4699 |

| B16F10 | ATCC | CRL-6475; RRID: CVCL 0159 |

| RMA | Provided by Prof. K. Kärre (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden) | RRID: CVCL_J385 |

| MC38 | Provided by Prof. Marco Colonna (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, USA) | RRID: CVCL_B288 |

| R1 | Provided by Prof. Paola Ricciardi- Castagnoli | |

| KPC | Provided by Dr. Thorsten Hagemann, Queen Mary University of London | |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Qa-1b−/− (targeted mutation of the H2-T23 gene) | Jackson Laboratory; provided by Dr. M. Vocanson (Lyon, France) | Stock#: 007907; RRID: IMSR_JAX:007907 |

| Mouse: TCR transgenic mice gp10025–33/H-2Db bred to express congenic marker CD45.1 (Ly5.1) | Provided by Dr. N.P. Restifo (NIH, Bethesda, USA) | |

| Mouse: C57BL/6 | Charles River Laboratories France | |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| sgRNA sequence for Qa-1: 5’-GGCTATGTCATTCGCGGTCC-3’ | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| sgRNA expression vector | Addgene | 41824 |

| plasmid containing Cas9 WT | Addgene | 41815 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| R version 3.4.2 (package survival) | R Project | https://www.r-proiect.org; RRID:SCR_001905 |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Firehose, The Broad Institute | https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/ |

| GraphPad Prism v7 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism; RRID: SCR_002798 |

| FlowJo v10 | TreeStar | https://www.flowjo.com/solutions/flowjo; RRID: SCR_008520 |

| CRISPR gRNA Design | Zhang Lab, MIT | http://crispr.mit.edu |

| Cytobank | Cytobank | https://www.cytobank.org/; RRID:SCR_014043 |

| Other | ||

Custom metal conjugation

Highlights.

Checkpoint NKG2A is expressed on intratumoral CD103+ effector CD8 T cells

NKG2A is upregulated on CD8 T cells in tumors by cancer vaccines

IFN-γ induces the ligand Qa-1/HLA-E on tumor cells, mediating adaptive resistance

Blocking NKG2A turns cancer vaccines into effective therapies

Blocking the function of the NKG2A inhibitory receptor as well as its ligand promotes robust antiltumor immunity in a number of animal tumor models, including one refractory to PD-1 blockade.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Ferry Ossendorp for providing the optimized MC38 neoantigen peptides and the peptide synthesis facility of the department IHB, LUMC for peptides and MHC tetramers. Furthermore, Novartis is acknowledged for providing recombinant human IL-2 (Proleukin). This study was financially supported by grants of the Dutch Cancer Society (2014–7146 for NvM and 2014–6696 for SJAMS) and Innate Pharma.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Pascale André and Nicolai Wagtmann were employees and shareholders of Innate Pharma at the time of this study. Sjoerd H. van der Burg and Thorbald van Hall hold a patent on NKG2A and received a research grant from Innate Pharma.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- ABIKO K, MATSUMURA N, HAMANISHI J, HORIKAWA N, MURAKAMI R, YAMAGUCHI K, YOSHIOKA Y, BABA T, KONISHI I & MANDAI M 2015. IFN-gamma from lymphocytes induces PD-L1 expression and promotes progression of ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer, 112, 1501–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSSON E, POSCHKE I, VILLABONA L, CARLSON JW, LUNDQVIST A, KIESSLING R, SELIGER B & MASUCCI GV 2016. Non-classical HLA-class I expression in serous ovarian carcinoma: Correlation with the HLA-genotype, tumor infiltrating immune cells and prognosis. Oncoimmunology, 5, e1052213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDRÉ P, DENIS C, SOULAS C, BOURBON C, LOPEZ J, ARNOUX T, BLÉRY M, BONNAFOUS C, REMARK R, BRESO V, BONNET E, LALANNE A, LANTZ O, FAYETTE J, BOYER-CHAMARD A, ZERBIB R, DODION P, NARNI-MANCINELLI E, COHEN RB & VIVIER E 2018. Anti- NKG2A mAb is a checkpoint inhibitor that promotes anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. In submittion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANFOSSI N, ANDRE P, GUIA S, FALK CS, ROETYNCK S, STEWART CA, BRESO V, FRASSATI C, REVIRON D, MIDDLETON D, ROMAGNE F, UGOLINI S & VIVIER E 2006. Human NK cell education by inhibitory receptors for MHC class I. Immunity, 25, 331–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANG KK, HARRIS J, WHEELER R, WEBER R, ROSENTHAL DI, NGUYEN-TAN PF, WESTRA WH, CHUNG CH, JORDAN RC, LU C, KIM H, AXELROD R, SILVERMAN CC, REDMOND KP & GILLISON ML 2010. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med, 363, 24–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERTONE S, SCHIAVETTI F, BELLOMO R, VITALE C, PONTE M, MORETTA L & MINGARI MC 1999Transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of CD94/NKG2A inhibitory receptors in human T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol, 29, 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOSMULLER HC, WAGNER P, PEPER JK, SCHUSTER H, PHAM DL, GREIF K, BESCHORNER C, RAMMENSEE HG, STEVANOVIC S, FEND F & STAEBLER A 2016. Combined Immunoscore of CD103 and CD3 Identifies Long-Term Survivors in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer, 26, 671–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAUD VM, ALDEMIR H, BREART B & FERLIN WG 2003. Expression of CD94-NKG2A inhibitory receptor is restricted to a subset of CD8+ T cells. Trends in Immunology, 24, 162–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAUD VM, ALLAN DS, O’CALLAGHAN CA, SODERSTROM K, D’ANDREA A, OGG GS, LAZETIC S, YOUNG NT, BELL JI, PHILLIPS JH, LANIER LL & MCMICHAEL AJ 1998. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature, 391, 795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROOKS AG, POSCH PE, SCORZELLI CJ, BORREGO F & COLIGAN JE 1997. NKG2A complexed with CD94 defines a novel inhibitory natural killer cell receptor. J Exp Med, 185, 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANCER GENOME ATLAS N 2015. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature, 517, 576–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE VOS VAN STEENWIJK PJ, HEUSINKVELD M, RAMWADHDOEBE TH, LOWIK MJ, VAN DER HULST JM, GOEDEMANS R, PIERSMA SJ, KENTER GG & VAN DER BURG SH 2010An unexpectedly large polyclonal repertoire of HPV-specific T cells is poised for action in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Res, 70, 2707–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DECLOUX A, WOODS AS, COTTER RJ, SOLOSKI MJ & FORMAN J 1997. Dominance of a single peptide bound to the class I(B) molecule, Qa-1b. J Immunol, 158, 2183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOORDUIJN EM, SLUIJTER M, QUERIDO BJ, SEIDEL UJE, OLIVEIRA CC, VAN DER BURG SH & VAN HALL T 2018. T Cells Engaging the Conserved MHC Class Ib Molecule Qa-1(b) with TAP-Independent Peptides Are Semi-Invariant Lymphocytes. Front Immunol, 9, 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELY KH, MATSUOKA M, DEBERGE MP, RUBY JA, LIU J, SCHNEIDER MJ, WANG Y, HAHN YS & ENELOW RI 2014. Tissue-protective effects of NKG2A in immune-mediated clearance of virus infection. PLoS One, 9, e108385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOODEN M, LAMPEN M, JORDANOVA ES, LEFFERS N, TRIMBOS JB, VAN DER BURG SH, NIJMAN H & VAN HALL T 2011. HLA-E expression by gynecological cancers restrains tumor-infiltrating CD8(+) T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108, 10656–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUBIN MM, ZHANG X, SCHUSTER H, CARON E, WARD JP, NOGUCHI T, IVANOVA Y,HUNDAL J, ARTHUR CD, KREBBER WJ, MULDER GE, TOEBES M, VESELY MD, LAM SS, KORMAN AJ, ALLISON JP, FREEMAN GJ, SHARPE AH, PEARCE EL, SCHUMACHER TN, AEBERSOLD R, RAMMENSEE HG, MELIEF CJ, MARDIS ER, GILLANDERS WE, ARTYOMOV MN & SCHREIBER RD 2014. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature, 515, 577–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNTURI A, BERG RE, CROSSLEY E, MURRAY S & FORMAN J 2005. The role of TCR stimulation and TGF-beta in controlling the expression of CD94/NKG2A receptors on CD8 T cells. Eur J Immunol, 35, 766–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEUSINKVELD M, GOEDEMANS R, BRIET RJ, GELDERBLOM H, NORTIER JW, GORTER A,SMIT VT, LANGEVELD AP, JANSEN JC & VAN DER BURG SH 2012. Systemic and local human papillomavirus 16-specific T-cell immunity in patients with head and neck cancer. Int J Cancer, 131, E74–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOMBRINK P, HELBIG C, BACKER RA, PIET B, OJA AE, STARK R, BRASSER G, JONGEJAN A, JONKERS RE, NOTA B, BASAK O, CLEVERS HC, MOERLAND PD, AMSEN D & VAN LIER RA 2016. Programs for the persistence, vigilance and control of human CD8(+) lung- resident memory T cells. Nat Immunol, 17, 1467–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAISER BK, BARAHMAND-POUR F, PAULSENE W, MEDLEY S, GERAGHTY DE & STRONG RK 2005. Interactions between NKG2x Immunoreceptors and HLA-E Ligands Display Overlapping Affinities and Thermodynamics. The Journal of Immunology, 174, 2878–2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEBANOFF CA, ACQUAVELLA N, YU Z & RESTIFO NP 2011. Therapeutic cancer vaccines: are we there yet? Immunol Rev, 239, 27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINOVINK JW, VAN DRIEL PB, SNOEKS TJ, PROKOPI N, FRANSEN MF, CRUZ LJ, MEZZANOTTE L, CHAN A, LOWIK CW & OSSENDORP F 2016. Combination of Photodynamic Therapy and Specific Immunotherapy Efficiently Eradicates Established Tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 22, 1459–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOMDEUR FL, PRINS TM, VAN DE WALL S, PLAT A, WISMAN GBA, HOLLEMA H, DAEMEN T, CHURCH DN, DE BRUYN M & NIJMAN HW 2017. CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are tumor-reactive intraepithelial CD8+ T cells associated with prognostic benefit and therapy response in cervical cancer. Oncoimmunology, 6, e1338230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRAFT JR, VANCE RE, POHL J, MARTIN AM, RAULET DH & JENSEN PE 2000. Analysis of Qa-1bPeptide Binding Specificity and the Capacity of Cd94/Nkg2a to Discriminate between Qa-1-Peptide Complexes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 192, 613–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LE DREAN E, VELY F, OLCESE L, CAMBIAGGI A, GUIA S, KRYSTAL G, GERVOIS N, MORETTA A, JOTEREAU F & VIVIER E 1998. Inhibition of antigen-induced T cell response and antibody- induced NK cell cytotoxicity by NKG2A: association of NKG2A with SHP-1 and SHP-2 protein- tyrosine phosphatases. Eur J Immunol, 28, 264–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LY LV, SLUIJTER M, VAN DER BURG SH, JAGER MJ & VAN HALL T 2013. Effective cooperation of monoclonal antibody and peptide vaccine for the treatment of mouse melanoma. J Immunol, 190, 489–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]