ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to understand the central meaning of the experience of providing CenteringPregnancy for perinatal educators who were facilitators for the group sessions. Four perinatal educators participated in one-on-one interviews and/or a validation focus group. Six themes emerged: (a) “stepping back and taking on a different role,” (b) “supporting transformation,” (c) “getting to knowing,” (d) “working together to bridge the gap,” (e) “creating the environment,” and (f) “fostering community.” These themes contributed to the core phenomenon of being “invested in success.” Through bridging gaps and inconsistencies in information received from educators and physicians, this model of CenteringPregnancy provides an opportunity for women to act on relevant information more fully than more traditional didactic approaches to perinatal education.

Keywords: perinatal educators, pregnancy, prenatal care, perinatal education

INTRODUCTION

Almost all pregnant women in Canada receive prenatal care from either a physician or a midwife; however, only approximately one-third attend perinatal education classes (hereafter, referred to as perinatal classes; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009). In perinatal classes, an instructor (i.e., educator) provides prespecified educational content to a group of pregnant women and their partners or support people. Although these classes vary in content and format across Canada, they tend to focus primarily on childbirth although some programs include information on infant care and the early postpartum period (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009; Walker & Worrell, 2008). In Calgary (population 1 million), where this study was conducted, perinatal classes provided through the provincial health service typically have a maximum of 12 pregnant women in attendance (as well as their partners or support people) and provide about 12–20 hours of instruction. Women generally pay a fee to attend these perinatal classes and subsidies are available. Some private organizations provide perinatal classes on a fee-for-service basis.

For more information on CenteringPregnancy, see https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/what-we-do/centering-pregnancy.

The benefits of perinatal classes have been difficult to determine because of the limitations of research to date and inconsistencies in outcome indicators (Gagnon & Sandall, 2007). Large randomized controlled trials are rare and difficult to implement given the popularity of perinatal classes in some countries, a lack of women’s willingness to be randomized, and difficulties with ensuring compliance to a randomization (Gagnon & Sandall, 2007). Among observational studies, some have found associations between attendance at prenatal classes and increased knowledge (Carter, Gelmon, Wells, & Toepell, 1989; Corwin, 1999; Svensson, Barclay, & Cooke, 2009; Washington, Stafford, Stomsvik, & Giannini, 1983; Westney, Cole, & Munford, 1988). A few studies have also shown some positive associations between prenatal classes and parental attachment or interaction (Carter-Jessop, 1981; Diemer, 1997; Doherty, Erickson, & LaRossa, 2006; Parr, 1998; Pfannenstiel & Honig, 1991). In addition, there is relatively strong evidence from systematic reviews (Dyson, McCormick, & Renfrew, 2005; Guise et al., 2003) and a few individual comparative studies, including randomized controlled trials, of improvements in breastfeeding initiation, duration, or satisfaction (Duffy, Percival, & Kershaw, 1997; Forster, McLachlan, & Lumley, 2006; Kistin, Benton, Rao, & Sullivan, 1990; Léger-Leblanc & Rioux, 2008; Roig et al., 2010; Wiles, 1984; Wolfberg et al., 2004). However, it is difficult to determine whether such associations are because of the impact of the prenatal classes or because of differences between those who attend prenatal classes and those who do not. Women who attend classes are more likely to be first-time mothers (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009), be of White ethnicity (Lu et al., 2003), have some postsecondary education (Lu et al., 2003), be married (Lu et al., 2003), and not be living in a low-income household (Lu et al., 2003; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2009).

The benefits of perinatal classes have been difficult to determine because of the limitations of research to date and inconsistencies in outcome indicators.

Departing from standard prenatal care and education practices, group prenatal care is a model of care that provides medical care and perinatal education simultaneously in a group setting. CenteringPregnancy is a specific form of group prenatal care where 8–12 pregnant women, who are at a similar gestational age, meet as a group for ten 2-hour sessions starting early in the second trimester (Rising, Kennedy, & Klima, 2004). In CenteringPregnancy, women have a brief individual physical assessment with their provider in the group space but also participate in their own care through activities such as measuring and recording their blood pressure and weight (Rising et al., 2004). Each session includes a group discussion that focuses on a general pregnancy, childbirth, or parenting topic, with providers facilitating discussion and supporting the group to identify content specific to their needs (Rising et al., 2004). Key components of the program include the opportunity for women to interact with each other during these sessions and to build social support and empowerment (Rising et al., 2004).

CenteringPregnancy is a specific form of group prenatal care where 8–12 pregnant women, who are at a similar gestational age, meet as a group for ten 2-hour sessions starting early in the second trimester.

CenteringPregnancy originated in the United States and is gaining momentum there and elsewhere (Massey, Rising, & Ickovics, 2006). Research evidence from two randomized controlled trials suggest that women who participate in CenteringPregnancy have better outcomes compared to women who receive individual prenatal care (Ickovics et al., 2007; Kennedy et al., 2011). These studies have found that women in CenteringPregnancy are more likely to have an adequate number of prenatal visits, have more knowledge about pregnancy and infant care, rate their satisfaction with care more highly, have decreased rates of preterm birth, and are better prepared for birth (Ickovics et al., 2007; Kennedy et al., 2011). Through qualitative research studies, women have indicated that CenteringPregnancy provides them with more than they realize they need (McNeil et al., 2012). They gain information, feel supported, connect with other women and their providers, feel normal and identify with other women, find care is efficient, and take ownership of care (Kennedy et al., 2009; McNeil et al., 2012; Novick et al., 2011; Teate, Leap, Rising, & Homer, 2011).

Although CenteringPregnancy was originally provided by midwives, various professionals, including nurses, physicians, social workers, and perinatal educators, have been trained to cofacilitate sessions (Rising et al., 2004). The involvement of perinatal educators is not surprising given the similarities between the CenteringPregnancy and perinatal classes. Both have similar goals in promoting health and empowerment of pregnant women and use group processes while covering some of the same content (Walker & Worrell, 2008). However, there are some notable differences between CenteringPregnancy and perinatal classes (Walker & Worrell, 2008). First, CenteringPregnancy incorporates prenatal clinical visits with perinatal education, whereas women attending perinatal classes must attend their prenatal clinical visits at a separate location and time (Walker & Worrell, 2008). Second, although CenteringPregnancy sessions start early in the second trimester, most perinatal classes begin in the third trimester of pregnancy (Walker & Worrell, 2008). Third, discussions in CenteringPregnancy are led by the women in the group, whereas discussions in perinatal classes are often led by the instructor or educator (Walker & Worrell, 2008). Although such comparisons have been made between the design of CenteringPregnancy and perinatal classes (Walker & Worrell, 2008), no previous studies have examined the experience of perinatal educators involved in CenteringPregnancy. The objective of this study was to understand the central meaning or core experience of perinatal educators in providing CenteringPregnancy in partnership with physicians from a community-based, low-risk maternity clinic.

METHODS

Study Design

This study used qualitative phenomenology and Heidegger’s approach to inquiry to understand the experience of CenteringPregnancy for perinatal educators (Heidegger, 1962). Previously, we reported on the experience of physicians (McNeil et al., 2013) and women (McNeil et al., 2012) participating in CenteringPregnancy. The study was based on the premise that the language of a group with a common experience (in this case, educators involved in providing CenteringPregnancy) could be used to identify the shared common meanings of the experience (Heidegger, 1962).

Model of Care

This CenteringPregnancy program was conducted in a group practice of family physicians who provide maternity care to women with low-risk pregnancies in Calgary, Canada. Perinatal educators cofacilitated each group session with a family physician. The educators and physicians attended 2 days of Level I training in the CenteringPregnancy model through the Centering Healthcare Institute, and one physician also attended Level II training (Centering Healthcare Institute, 2009). At the time of the study, site approval for the CenteringPregnancy program had not yet been obtained.

Recruitment, Sample, and Data Collection

At the time of the initial interviews, three educators were facilitators in providing CenteringPregnancy and were invited to participate in one-on-one interviews about their experience with CenteringPregnancy. Between October 2009 and January 2010, one of two interviewers (DAM or MV, neither members of the health-care team) met with each study participant (perinatal educator) at a convenient location. One interview was 30 minutes and the other two were 50 minutes in duration and the interviews were audio recorded. Table 1 outlines the interview guide used. Interviews were later transcribed verbatim without names, and participants were referred to by a study identification number for analysis. The study was approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, and all participants provided written informed consent.

TABLE 1. Interview Guide.

| Central Interview Question |

| What was it like for you to provide this type of care? |

| Additional Questions |

| What was the best thing about providing group prenatal care? |

| What was the worst thing about it? |

| What about this experience went as expected? |

| What about this experience did not go as expected? |

| Probes |

| Can you tell me more about what that was like for you or meant to you? |

Data Analysis

Before beginning data analysis, each investigator described his or her personal experience with prenatal care in prose and considered how the experience might influence the analysis to address reflexivity (Malterud, 2001). To begin data analysis, each investigator read the transcripts several times, which facilitated dependability (Malterud, 2001). Investigators noted statements that had meaning regarding the CenteringPregnancy experience, assembled these statements into “meaning units” or themes, and compiled a description. Together, the investigative team discussed possible meanings and divergent perspectives and, through regular meetings, reached consensus on meaning themes and developed a description of the “essence” or core of the experience. Throughout the analysis phase, the team revisited the transcripts and related meaning statements to ensure dependability (Malterud, 2001).

A confirmation focus group was held approximately 15 months after the interviews to ensure confirmability (Malterud, 2001). At the time of the validation focus group, five educators were involved in providing CenteringPregnancy and were invited to participate in the focus group. The confirmation focus group ran for approximately 80 minutes and was audio recorded, during which time one of the investigators shared preliminary findings with the participants and further elucidation on the proposed findings. The session was also transcribed and analyzed.

RESULTS

The sample consisted of two educators who participated in both a one-on-one interview and the validation session, one educator who only participated in a one-on-one interview and one educator who only participated in the validation session. Therefore, four of five educators who participated in the program as facilitators participated in the research (three in one-on-one interviews and three in the focus group session). All participants were female and were experienced perinatal educators.

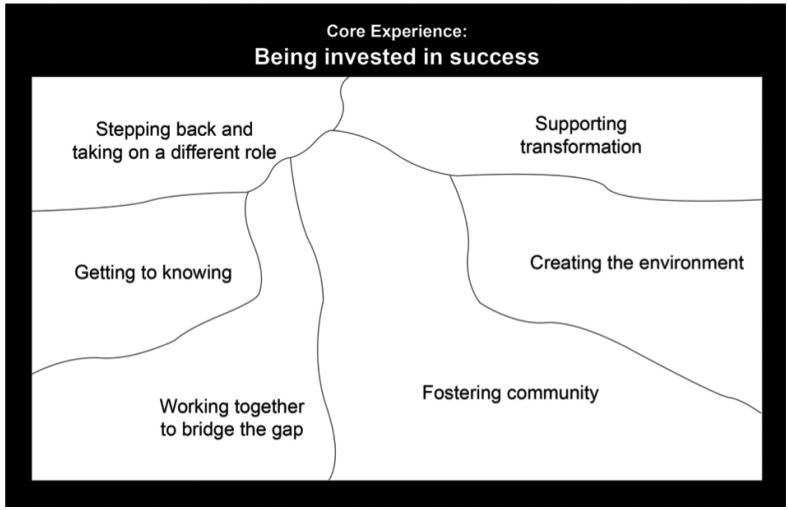

During analysis, five themes emerged which described the meaning of the experience for the educators providing CenteringPregnancy and contributed to the development of the core experience. The validation session not only confirmed the five themes but also identified an additional theme of “creating the environment” (Figure 1). Through the validation session, the core experience was revised from “being part of the whole package” to “being invested in success.” The final themes and core experience are presented in the following sections using exemplars from the participants.

Figure 1. Themes and core experience of perinatal educators participating in CenteringPregnancy.

Theme: Stepping Back and Taking on a Different Role

The facilitative role that educators took on in group prenatal care differed from their typical, didactic teaching role. In group prenatal care, the educators “kind of step[ped] back a little bit . . . in my role of providing information” (Educator 3). The educators

[let] [women] lead and [let] them give the answers . . . allow[ing] them to understand that they have knowledge and they have skills and they can do this on their own and . . . they can come to the so-called experts for things they don’t know but they can actually figure things out themselves. (Educator 2)

This different role was not without its challenges.

It was hard at first because . . . that lack of control makes you feel like, I don’t know if they’re getting the right amount of information and then I started to realize . . . who am I to decide what kind of information they really need? (Educator 3)

The educator’s role was also demanding because they made moment-by-moment decisions about how much to step in or step back. “I still struggle a little bit with knowing when to be quiet and let them talk and when to provide information that I think is very important for them to know” (Educator 3).

In drawing on women’s knowledge, the educators found that it “kind of took the pressure off of me to some extent” (Educator 3). They were no longer solely responsible for guiding the group and providing all the information but rather entrusted women to share in determining the direction of the group, share their knowledge, and take responsibility for their own health and learning. “If I just keep on stressing the importance of them asking for what they need, they’ll ask the questions that they need to ask and they’ll get the information they need” (Educator 3). However, this required more flexibility from the educators than in their typical role, so they couldn’t “have everything perfectly laid out” (Educator 3) and entirely planned ahead.

Theme: Supporting Transformation

In their role, educators supported women’s transformations. Educators “can just see [the women] sort of growing as individuals . . . they’re actually . . . trusting themselves a little bit more” (Educator 3). They “[saw] a lot of [women] change . . . get more confident and be willing to speak up in the group, and give their opinions” (Educator 2) and realize, “Oh you know, I guess I know more than I thought I did” (Educator 3). The educators

want[ed] [women] to be able to go, “Well, I can make this decision. I don’t have to really phone anybody, but if I don’t really know, I know where to find some information, but make my own decision with it.” (Educator 2)

Educators saw these changes occur “as the time unfold[ed]” (Educator 3) in the group. For instance, one educator recalled how she

[saw] transformations that are absolutely amazing. A young girl . . . by the end of the tenth session, it’s like she grew up . . . 5 years . . . with the support of the group . . . the older . . . mothers were coaching that young mom and she was feeling more and more respect from the group. . . . And for that kid to be listened to by the older ones was also of value.” (Educator 1)

Theme: Getting to Knowing

The educators got to know the physicians as people, so

there was more than just respect for the professional. It was the women behind. . . . And . . . when you know somebody and you can discover things . . . that you have in common, and you can chat . . . it creates a very different atmosphere. (Educator 1)

In working with the physicians and getting to know them, the educators recognized that they both “ha[d] the same goal, the same interest” (Educator 1)—that of caring for women—and “develop[ed] a rapport . . . with the doctor” (Educator 3). The educators also “[had] my experience or my expertise validated by another health-care professional” (Educator 3). Educators

like[d] the team concept [of] . . . working with the physician . . . ‘cause . . . they’re learning what we know . . . I’m learning what they know and . . . that’s been good for, in my opinion, for everybody on the team . . . because you can see . . . where they’re coming from as well. (Educator 2)

Working together and learning from each other facilitated a greater understanding and appreciation of the other’s perspective and expertise.

The educators also “learned a lot about what women already know and how much wisdom is already kind of there and really it’s just a matter of helping them to realize” (Educator 3). With each specific group, the educators had a better sense of the specific pieces of information the group knew and did not know while learning what women felt was important to know. The educators also learned about themselves, “That I could be that flexible and that it could still work” (Educator 3).

Theme: Working Together to Bridge the Gap

More collaboration happened because the physician and educator “both ha[d] their strengths” (Educator 2) and were working together as a team to deliver care to women in the group.

When I do the [regular perinatal] classes, I find that sometimes I’m getting, “Well, my doctor said this. Well, you’re saying [that].” And [in group prenatal care] . . . we can be . . . very sure that . . . the information that’s been provided is consistent . . . because . . . we’re both there to provide the information. So if there is any sort of questions then . . . we can discuss it in that setting. (Educator 3)

Working together with the physicians in this way was “a really nice way of bridging the gap between health-care providers and it provides that continuity of care that I think women really need more than any other time in their lives, when they’re pregnant” (Educator 3).

The educators also “work[ed] with women and sort of [drew] knowledge out of them” (Educator 3). They involved women in the care process and entrusted them to ask for the information they need. The process of group prenatal care “sen[t] the message loud and clear [to women] . . . you’re really responsible for your own health care” (Educator 3). Educators saw this as “tak[ing] a little bit of the pressure off the health-care system. . . . People can make the decisions for themselves about what works” (Educator 3).

Theme: Creating the Environment

Educators noted that “there’s things that need to be in place so that . . .” (Educator 2) “it seems natural” (Educator 3) and the session ran smoothly. This involved practical things such as quality of the space, availability of supplies and teaching resources, and knowing which physician would be cofacilitating. It also involved setting up materials and equipment in a consistent place so that women could “get their name tags, pee on their stick, [and] do their blood pressure” (Educator 2). “[Everything has] to be in the right place at the right time. So everybody . . . can do their thing” (Educator 2). Educators saw themselves as helping to “create a consistent place for safety . . . for [the women] . . . they know what to expect . . . and then they’re comfortable enough to open up” (Educator 3). “It’s creating the environment” (Educator 3) “so that we can foster community” (Educator 2) and “do our jobs, the way we feel comfortable doing our jobs” (Educator 3). Although educators acknowledged that they couldn’t completely create the environment, they “know how important [the environment] is for the success and the flow of the whole experience for everybody. . . . And the comfort for everyone” (Educator 3).

Theme: Fostering Community

The educators fostered a sense of community among the group by helping to provide an atmosphere that supported the development of community. By ensuring women’s opinions were respected and with “the humor, the use of first name, the sitting in a circle, and the food in the middle . . . it creates a safe atmosphere, nonjudgmental, relaxed, it’s a visit . . . with a consistent group” (Educator 1). This atmosphere laid the foundation for more meaningful conversation because “you cannot have a very good conversation going in a group if you don’t make the people comfortable first . . . then we got into topics” (Educator 1). Also, “being comfortable in the learning environment, [the women] truly asked the questions that they wanted to” (Educator 1). The educators also found sensitive topics easier to address because “when you create a relationship with a group, some topics are easier to be discussed” (Educator 1). In the later sessions, the educators saw that women were “really starting to come out of their shell and . . . say, ‘Okay it is a safe place for me say that I don’t agree with what she’s having to say over there’” (Educator 2).

Furthermore, in stepping back from a typical teaching role, the educators fostered a stronger sense of community among the women as they interacted more in the group context.

It makes a big difference for a woman to hear information coming from another woman who’s going through the same experience, rather than me who is the so-called expert . . . there’s a bit of a barrier there . . . even if I’ve had kids, even if I’m very personable. (Educator 3)

As women interacted and got to know each other, stronger connections developed between some of them, some of which endured past the end of the sessions.

I think that naturally happens in a group setting where . . . two women that are sitting next to each other, or . . . see similarities in each other, they might chat a little bit more. . . . And then they just kind of keep in contact with one another. (Educator 3)

This provided the educators with a sense that women had support.

I always like it when there’s been a connection made in the group. . . . If you can see that a couple of them . . . they’re phoning each other or making that connection that you know that they’ll be able to support themselves . . . emotionally and in their new jobs. (Educator 2)

It was satisfying for the educators to see this community being created “because I know how important it is for women that are going through this in their lives to have somebody that they can talk to about it” (Educator 2).

The Core of the Experience: Invested in Success

Through CenteringPregnancy, educators were invested in the success of the program in terms of its impact on women. Educators were “trying to be part of something new and innovative for our area . . . that would possibly benefit the women that we deal with” (Educator 2). They were “invested in the success of the program” (Educator 3), “[saw] that there’s so much potential for this [program]” (Educator 4), and “want[ed] to have the best program on earth” (Educator 2). As educators supported transformations in women, created a consistent and comfortable environment, fostered community among the women, and worked to bridge typical gaps in the health-care system, they were investing in the success of the program and the success of each woman. In this experience, educators also found themselves stepping back and taking on a different role and getting to know the physicians and the women. However, the core theme based on individual interviews and validated in the focus group was that

everything that we do . . . is to make it a potential for a successful environment for these mothers and for their relationship with their physician. And whatever I have to do, preparation I have to do to get to that point . . . I want to give them something that they can feel successful in being a part of this. (Educator 4)

The educators wanted to make available “a foundation for [women] to . . . have a successful, hopefully for them, birth experience, a successful parenting experience” (Educator 3). Although the educators recognized they were not in complete control of the success of the program or the success that a particular woman might experience, they felt responsible to make the program as successful as possible.

DISCUSSION

The key finding of this research is that educators who provided CenteringPregnancy were “invested in success.” Their investment lead them to work hard to keep the program going and they provided what others have said is important for sustaining this model of care, a strong advocate within the program (Novick et al., 2015). The educators’ investment in sustaining the model is similar to that identified by midwives as they moved through the stages of change in implementing CenteringPregnancy (Baldwin & Phillips, 2011). Although the core experience does not directly speak to differences in the experiences of providing CenteringPregnancy versus typical perinatal classes, some of the themes offer insight into differences. Educators found their role to be more facilitative in CenteringPregnancy. Compared to their experience of typical perinatal classes, educators provided women more opportunity to share their knowledge and provided more space for women to express their needs in CenteringPregnancy. The relationship between educators and women was less of a didactic teacher–learner relationship, as in typical perinatal classes, and more of a partnership. In CenteringPregnancy, educators and women worked together to help them recognize the knowledge they already had, find ways to address their needs, and take responsibility for their own health.

The key finding of this research is that educators who provided CenteringPregnancy were “invested in success.”

Educators also developed a different relationship with physicians. In typical prenatal care and perinatal classes, the educator and physician work independently, and the educators noticed that women sometimes reported receiving alternate and/or conflicting information from physicians and educators in these situations. In CenteringPregnancy, information could be discussed and clarified to ensure that it was understood. Furthermore, the educators worked as part of a team with physicians, felt respected, and knew that they had a shared goal of caring for women. By operating as a team, the educators, physicians, and women learned from each other and could discuss “conflicting” information in the group, which often led to clarification that the information was actually complementary. The relationship that educators developed with the physicians bridged a gap that the educators ordinarily felt when providing typical perinatal classes.

Given the common goals of CenteringPregnancy and perinatal education (Walker & Worrell, 2008), perinatal educators may similarly be invested in the success of women through providing CenteringPregnancy or providing typical perinatal classes. Rather, any differences in experience may be more apparent in how the educators go about investing in the success of women through CenteringPregnancy compared to typical perinatal classes. In particular, the educators provided statements that compared their experience of CenteringPregnancy with their experience of typical perinatal classes when describing “stepping back and taking on a different role,” “getting to know” the physician and women, and “working together to bridge the gap.”

There is alignment between the experiences of the educators, and our previous exploration of physicians’ (McNeil et al., 2013), and the women’s (McNeil et al., 2012) experiences of participating in CenteringPregnancy. The educators were invested in the women’s success as mothers and wanted to foster a community that provided support to women, and this coincides with women’s perspective of feeling supported in the program (McNeil et al., 2012). As educators worked with the physicians and women to bridge the gap that exists in typical service delivery models, they saw that women received more consistent information as well as information that addressed their questions and needs. This aligns well with the women’s perspective because women reported learning meaningful information in CenteringPregnancy (McNeil et al., 2012). Also, as educators stepped back and took on a different, more facilitative role and supported transformation among the women, this enabled women to actively participate and take ownership of their care (McNeil et al., 2012). Of note, although educators described stepping back and sharing ownership of care with the women, the physicians saw themselves as sharing ownership of care with both the women and educators (McNeil et al., 2013). It may be that equilibrium was reached where women, the physicians, and the educators each took a level of ownership of care that felt appropriate for them.

As educators worked with the physicians and women to bridge the gap that exists in typical service delivery models, they saw that women received more consistent information as well as information that addressed their questions and needs.

Of importance, the educators saw creating the environment as a key element in their experience, which supported the overall program. By creating a comfortable and consistent environment, educators thought this improved the chances that community would develop and that women could connect with each other. Women could also more readily take ownership of their care and perform their self-care activities, such as taking their own blood pressure because the educators set up the environment to facilitate this (i.e., consistent placement of materials so that women knew what to expect). In ensuring things were set up to run smoothly and efficiently, the educators may have partly contributed to the opportunity for women to get more in one place at one time (McNeil et al., 2012) and physicians having a sense of more time (McNeil et al., 2013). Educators recognized that creating an environment that worked for everyone—women, physicians, and educators—was vital to the success of the program. By investing in the success of the program, educators contributed to the experience of women who got more than they realized they needed (McNeil et al., 2012) and contributed to the experience of physicians in providing richer care (McNeil et al., 2013).

Despite the rich descriptions of the experience that were generated through this research, there is a possibility that if there were more educators participating in the program, the investigators may not have reached data saturation and the findings may have been extended beyond the current findings. Although the confirmation session occurred approximately 1 year following the original interviews, the study participants were all still facilitating CenteringPregnancy sessions, and thus, the findings still resonated with their experiences. Despite the earlier limitations, this is the first study, to our knowledge, examining the experience of childbirth educators with CenteringPregnancy. It addresses what one proponent has recommended, that of using a collaborative approach with childbirth educators to address childbirth education needs and prenatal care (Walker & Worrell, 2008).

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

Perinatal educators and physicians are influential sources of information for women regarding preparation for labor and birth (Simpson, Newman, & Chirino, 2010). Thus, bringing educators and physicians together through CenteringPregnancy could bridge current gaps and inconsistencies in information received from educators and physicians who work independently. Inconsistency from different sources and a lack of understanding can be barriers to acting on information (Coleman et al., 2009; Gross & Bee, 2004). In providing opportunities for educators, physicians, and women to work together to clarify complementary information and to communicate consistent messages, CenteringPregnancy empowers women to better understand and to act on relevant information that will promote their health and the health of their infants.

Furthermore, in stepping back and facilitating women’s active participation, educators in CenteringPregnancy take part in creating a learning environment that focuses on the needs of the women in the group. This is a component of perinatal education that is important to both parents-to-be and professionals (Dumas, 2002), because when the needs of women are met, they are more likely to act on information to improve their well-being (Tough et al., 2004). CenteringPregnancy allows educators to participate in a model of perinatal education that better aligns with the concepts of adult learning and meets the preferences of women more fully than traditional didactic approaches to perinatal education (Nolan, 2009). Women have specified that they prefer to interact by asking questions, participate in discussions which will allow them to better retain information by discussing it in light of their own circumstances, be in an environment where they can learn from other women, and make friends (Nolan, 2009). These elements, which meet the emotional health needs of women, are an inherent part of the program design of CenteringPregnancy and contribute to the ability of women to make positive change (Tough et al., 2004). However, such elements could also be integrated into typical perinatal education to more closely align with women’s preferences, and educators who provide CenteringPregnancy could be instrumental in restructuring current perinatal education programs. Furthermore, CenteringPregnancy programs benefit from having perinatal education professionals as cofacilitators because of their expertise and strong investment in the success of women and the program.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge the following:

-

•

Alberta Health Services (specifically former Calgary Health Region, Three Cheers for the Early Years) and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (as part of the Preterm Birth and Healthy Outcomes Team [PreHOT] Interdisciplinary Team Grant) for providing funding for this study

-

•

Alberta Innovates Health Solutions for providing salary support for Suzanne C. Tough

-

•

The Maternity Care Clinic, Alberta Health Services (Perinatal Education), and members of the program committee for partnering in the development and implementation of the CenteringPregnancy program

-

•

The physicians and perinatal educators who implemented and provided the CenteringPregnancy program

-

•

Members of the research committee for informing the development and implementation of the study

-

•

Sharon Schindler Rising and the Centering Healthcare Institute for their support in the development of a Calgary model for CenteringPregnancy and all members of the PreHOT, particularly Kathy Hegadoren, for their support, assistance, and enthusiasm for this.

Biographies

MONICA VEKVED was a project coordinator of Research and Innovation at Alberta Health Services and with the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Calgary. Monica’s research work is focused on healthy pregnancies and types of prenatal care.

DEBORAH A. McNEIL is scientific director maternal newborn child and youth and population public and indigenous health strategic clinical networks at Alberta Health Services and is an adjunct associate professor in the Faculty of Nursing and Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary. Her research program includes work on childhood obesity prevention, preterm infant feeding, parent infant interaction, and prenatal care.

SIOBHAN M. DOLAN is an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Women’s Health at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and an attending physician in the Division of Reproductive Genetics at Montefiore Medical Center, the University Hospital for Einstein, in New York City. She serves as a medical advisor to March of Dimes and is also on the faculty of the Human Genetics Program at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York.

JODI E. SIEVER is a senior analyst in biostatistics now with the Faculty of Medicine University of British Colombia. She held a similar position with Research and Innovation at Alberta Health Services at the time of the study.

SARAH HORN is currently working for the Aspen View School Division and was a research associate at the University of Calgary at the time of the study.

SUZANNE C. TOUGH is professor paediatrics, Cumming School of Medicine University of Calgary, scientific advisor for PolicyWise/SAGE and principal investigator for the All Our Families Research Team (formerly All Our Babies). She conducts research on healthy pregnancies, preterm birth, child development, and prenatal care as the leader of the Preterm Birth and Healthy Outcomes Team and the All Our Babies study.

REFERENCES

- Baldwin K., & Phillips G. (2011). Voices along the journey: Midwives’ perceptions of implementing the CenteringPregnancy model of prenatal care. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 20(4), 210–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter A. O., Gelmon S. B., Wells G. A., & Toepell A. P. (1989). The effectiveness of a prenatal education programme for the prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis. Epidemiology and Infection, 103, 539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter-Jessop L. (1981). Promoting maternal attachment through prenatal intervention. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 6, 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centering Healthcare Institute. (2009). What we do. Retrieved from https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/what-we-do/centering-pregnancy

- Coleman B. L., Gutmanis I., Larsen L. L., Leffley A. C., McKillop J. M., & Rietdyk A. E. (2009). Introduction of solid foods: Do mothers follow recommendations? Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 70, 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin A. (1999). Integrating preparation for parenting into childbirth education: Part II-A study. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 8(1), 22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diemer G. A. (1997). Expectant fathers: Influence of perinatal education on stress, coping, and spousal relations. Research in Nursing & Health, 20, 281–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty W. J., Erickson M. F., & LaRossa R. (2006). An intervention to increased father involvement and skills with infants during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy E. P., Percival P., & Kershaw E. (1997). Positive effects of an antenatal group teaching session on postnatal nipple pain, nipple trauma and breast feeding rates. Midwifery, 13, 189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas L. (2002). Focus groups to reveal parents’ needs for prenatal education. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 11, 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson L., McCormick F. M., & Renfrew M. J. (2005). Interventions for promoting the initiation of breastfeeding. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (2), . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster D. A., McLachlan H. L., & Lumley J. (2006). Factors associated with breastfeeding at six months postpartum in a group of Australian women. International Breastfeeding Journal, 1, 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon A. J., & Sandall J. (2007). Individual or group antenatal education for childbirth or parenthood, or both. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (3), 10.1002/14651858.CD002869.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross H., & Bee P. E. (2004). Perceptions of effective advice in pregnancy—the case of activity. Clinical Effectiveness in Nursing, 8, 161–169. [Google Scholar]

- Guise J. M., Palda V., Westhoff C., Chan B. K. S., Helfand M., & Lieu T. A. (2003). The effectiveness of primary care-based interventions to promote breastfeeding: Systematic evidence review and meta-analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Annals of Family Medicine, 1, 70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger M. (1962). Being and time. London, United Kingdom: SCM Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics J. R., Kershaw T. S., Westdahl C., Magriples U., Massey Z., Reynolds H., & Rising S. S. (2007). Group prenatal care and perinatal outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110, 330–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H. P., Farrell T., Paden R., Hill S., Jolivet R. R., Cooper B. A., & Rising S. S. (2011). A randomized clinical trial of group prenatal care in two military settings. Military Medicine, 176, 1169–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy H. P., Farrell T., Paden R., Hill S., Jolivet R. R., Willetts J., Rising S. S. (2009). “I wasn’t alone”—a study of group prenatal care in the military. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54, 176–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kistin N., Benton D., Rao S., & Sullivan M. (1990). Breast-feeding rates among Black urban low-income women: Effect of prenatal education. Pediatrics, 86, 741–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Léger-Leblanc G., & Rioux F. M. (2008). Effect of a prenatal nutritional intervention program on initiation and duration of breastfeeding. Canadian Journal of Dietetic Practice and Research, 69, 101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu M. C., Prentice J., Yu S. M., Inkelas M., Lange L. O., & Halfon N. (2003). Childbirth education classes: Sociodemographic disparities in attendance and the association of attendance with breastfeeding initiation. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 7, 87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K. (2001). Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet, 358, 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey Z., Rising S. S., & Ickovics J. (2006). CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care: Promoting relationship-centered care. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 35, 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil D. A., Vekved M., Dolan S. M., Siever J., Horn S., & Tough S. C. (2012). Getting more than they realized they needed: A qualitative study of women’s experience of group prenatal care. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 12, 17 10.1186/1471-2393-12-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil D. A., Vekved M., Dolan S. M., Siever J., Horn S., & Tough S. C. (2013). A qualitative study of the experience of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care for physicians. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, (13 Suppl. 1), S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M. L. (2009). Information giving and education in pregnancy: A review of qualitative studies. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 18, 21–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G., Sadler L. S., Kennedy H. P., Cohen S. S., Groce N. E., & Knafl K. A. (2011). Women’s experience of group prenatal care. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 97–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick G., Womack J. A., Lewis J., Stasko E. C., Rising S. S., Sadler L. S., . . . Ickovics J. R. (2015). Perceptions of barriers and facilitators during implementation of a complex model of group prenatal care in six urban sites. Research in Nursing & Health, 38, 462–474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parr M. (1998). A new approach to parent education. British Journal of Midwifery, 6, 160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Pfannenstiel A. E., & Honig A. S. (1991). Prenatal intervention and support for low-income fathers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 12, 103–115. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2009). What mothers say: The Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Rising S. S., Kennedy H. P., & Klima C. S. (2004). Redesigning prenatal care through CenteringPregnancy. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 49, 398–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig A. O., Martínez M. R., García J. C., Hoyos S. P., Navidad G. L., Alvarez J. C., . . . De León González R. G. (2010). Factors associated to breastfeeding cessation before 6 months. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 18, 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson K. R., Newman G., & Chirino O. R. (2010). Patients’ perspectives on the role of prepared childbirth education in decision making regarding elective labor induction. The Journal of Perinatal Education, 19, 21–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Barclay L., & Cooke M. (2009). Randomised-controlled trial of two antenatal education programmes. Midwifery, 25, 114–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teate A., Leap N., Rising S. S., & Homer C. S. E. (2011). Women’s experience of group antenatal care in Australia—the CenteringPregnancy pilot study. Midwifery, 27, 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tough S. C., Newburn-Cook C. V., Faber A. J., White D. E., Fraser-Lee N. J., & Frick C. (2004). The relationship between self-reported emotional health, demographics, and perceived satisfaction with prenatal care. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance Incorporating Leadership in Health Services, 17(1), 26–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D. S., & Worrell R. (2008). Promoting healthy pregnancies through perinatal groups: A comparison of CenteringPregnancy® group prenatal care and childbirth education classes. Journal of Perinatal Education, 17, 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington W. N., Stafford V. M., Stomsvik J., & Giannini C. (1983). Prenatal education for the Spanish speaking: An evaluation. Patient Education and Counseling, 5, 30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westney O. E., Cole O. J., & Munford T. L. (1988). The effects of prenatal education intervention on unwed prospective adolescent fathers. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 9, 214–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiles L. S. (1984). The effect of prenatal breastfeeding education on breastfeeding success and maternal perception of the infant. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 13, 253–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfberg A. J., Michels K. B., Shields W., O’Campo P., Bronner Y. L., & Bienstock J. (2004). Dads as breastfeeding advocates: Results from a randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 191, 708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]