Abstract

Prior studies have demonstrated that combined treatment of testosterone with a progestin induces a more rapid and greater suppression of spermatogenesis than testosterone treatment alone. We hypothesized that the suppressive effects of the combination of testosterone undecanoate (TU) injections plus oral levonorgestrel (LNG) on spermatogenesis may be mediated through a greater perturbation of testicular gene expression than TU alone. To test this hypothesis, we performed open testicular biopsy on 12 different adult healthy subjects: 1) four healthy men as controls; 2) four men 2 wk after TU treatment; and 3) four men 2 wk after TU + LNG administration. RNA isolated from biopsies was used for DNA microarray using the Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 oligonucleotide microarrays. Gene expression with ≥2-fold changes (P < 0.05) compared with control was analyzed using the National Institutes of Health Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery 2008 resource. The TU treatment altered the gene expression in 109 transcripts, whereas TU + LNG altered the gene expression in 207 transcripts compared with control. Both TU and TU + LNG administration suppressed gene expression of insulin-like 3; cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A1 in Leydig cells; and inhibin alpha in Sertoli cells; they increased proapoptotic transcripts BCL2-like 14, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3; and they decreased X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein. In comparison with TU treatment alone, TU + LNG treatment upregulated insulin-like 6 and relaxin 1, and downregulated RNA-binding protein transcripts. We conclude that TU + LNG administration induces more changes in testicular gene expression than TU alone. This exploratory study provided a novel and valuable database to study the mechanisms of action of hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis in men and identified testicular-specific molecules that may serve as potential targets for male contraceptive development.

Keywords: male contraception, progesterone, spermatogenesis, testicular gene expression, testis, testosterone

Introduction

Hormonal male contraception is achieved through the suppression of both luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and a decrease in intratesticular testosterone which, in turn, leads to the reliable and reversible suppression of spermatogenesis to azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia. Clinical studies have evaluated the contraceptive efficacy of spermatogenic suppression with combined administration of an androgen and a progestin at doses that maintain physiological serum testosterone levels [1]. The combination of a progestin and testosterone promotes more rapid and greater spermatogenic suppression than that of testosterone alone. The enhanced efficacy of the combined regimen allows a lower dose of testosterone to be used, thus reducing potential androgen-related side effects [2, 3]. Although progestins are generally thought to enhance the efficacy of androgens in the suppression of gonadotropin secretion, other mechanisms of the action of the combined hormonal treatment regimen on testes are possible.

In prior studies in rats, monkeys and humans, we have demonstrated that exogenous testosterone administration leads to accelerated germ cell apoptosis; we believe this proapoptotic effect is one of the principal mechanisms in testosterone-induced suppression of spermatogenesis [4–6]. In a prior manuscript, we showed that the addition of levonorgestrel (LNG) to a physiological dose of testosterone undecanoate (TU) treatment to men increased germ cell apoptosis more than TU treatment alone and resulted in a more rapid and greater suppression of spermatogenesis [4]. Other studies have provided additional evidence that treatment with combined testosterone and progestin also suppresses spermatogenesis by decreasing type B spermatogonia and impairing spermiation, leading to spermatozoa retention in rodents, monkey, and men [7, 8]. Although in our prior report [4] we did not find a significant change in germ cell apoptosis 2 wk after either TU or TU + LNG treatment in human testes, a recent study by other investigators reported increased spermatogonia apoptosis 2 wk after gonadotropin suppression induced by testosterone enanthate (TE) or TE combined with depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injections [9]. Two weeks of gonadotropin suppression also cause measurable changes to spermatogonial numbers in monkeys and men [7, 10]. To further understand the molecular mechanisms of the apparently greater effects of LNG on suppression of spermatogenesis induced by testosterone in the testis and to identify potential molecular targets for future male contraceptive development, we performed gene microarray analyses on testicular samples obtained from healthy male volunteers and men treated for 2 wk with either TU injections alone or TU plus LNG (TU + LNG). Biopsies obtained 2 wk after putative contraceptive administrations were selected for array analysis because our prior studies indicated no or minimal loss of germ cells at this time.

Materials and Methods

Subjects and Study Design

This testicular gene expression study was a subproject of a previously reported clinical trial to study changes in semen parameters, testicular morphology, and germ cell apoptosis in healthy male volunteers after TU or TU + LNG treatment [4]. In brief, in the main study healthy volunteer men (age range, 35–48 yr; mean ± SEM, 40.5 ± 4.2 yr) with proven fertility were recruited by the Jiangsu Family Planning Research Institute (Nanjing, China). All subjects had a normal physical examination, semen analysis, normal baseline hematology, blood biochemistry, urinalysis, and fasting lipid profile before entering the study [4]. They were randomized to different treatment groups (n = 18 per group), including the TU group (1000-mg intramuscular injection of TU followed by 500 mg TU intramuscularly every 6 wk for 18 wk) and TU + LNG group (TU treatment together with LNG [250 μg] orally daily for 18 wk). The subjects then were observed for another 12 wk until the return of sperm concentration to within the reference intervals of adult men. Twelve subjects were recruited to participate in the testicular biopsy substudy; refusal to participate in the testicular biopsy study did not exclude them from the main study [4]. We obtained testicular biopsies from four men in each group: 1) before treatment serving as control, 2) 2 wk after TU treatment; and 3) 2 wk after TU + LNG administration. None of the participants had more than one testicular biopsy. The ethics committees at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Jiangsu Family Planning Research Institute, and the Institutional Review Board of the Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute approved our study protocols. All subjects signed written informed consent.

Testicular Biopsy Procedure and Tissue Preparation

Each subject received one open testicular biopsy. Open unilateral testicular biopsy was performed under local anesthesia by experienced surgeons at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, China. Each biopsy was divided into three portions. One portion was fixed in Bouin solution for morphological analysis and immunohistochemistry [4], another was frozen in liquid nitrogen for protein analysis [11], and the third was stored in RNAlater (Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) for gene expression studies (see below). None of the subjects had adverse effects from the testicular biopsies except temporary mild testicular pain that required no treatment. Proteins isolated from testicular biopsies were subjected to two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time-of-flight mass spectrometry to assess the protein changes; these data have been published elsewhere [11].

DNA Microarray

RNA extraction and DNA microarray were performed at the UCLA DNA Microarray Core. In brief, total RNA was isolated from human testicular biopsies and purified by RNeasy Mini Kit spin columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Total RNA purified from each sample was used to synthesize biotinylated cRNA for the Affymetrix GeneChip Array (Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 oligonucleotide microarray). Briefly, 5 μg total RNA was used to start cDNA synthesis using polydT-24 primer containing a T7 RNA promoter. Synthesis of biotin-labeled cRNA was performed using an Affymetrix RNA transcription labeling kit. The labeled cRNA was purified with RNeasy Mini kit spin columns (Qiagen). The cRNA then was hybridized for 16 h with the Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 array, which interrogates 38 500 well-characterized human genes (Affymetrix GeneChip Technology, Santa Clara, CA). After hybridization, the chips were washed and stained with R-phycoerythrin-streptavidin, and the signal was amplified with antistreptavidin and scanned with a GeneChip Scanner 3000 (Affymetix). The intensity of each feature of the array was captured with an Affymetrix GeneChip Operating System, according to standard Affymetrix procedures. The mRNA abundance was determined based on the average of the differences between perfect match and intentional mismatch intensities for each probe set using Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 (MAS 5.0 Affymetrix) algorithm. Data that met the MicroArray Quality Control threshold at the UCLA DNA Microarray Core were used for data analysis. One control sample did not pass the quality control threshold and was excluded from data analysis.

Microarray Data Analysis

The GeneChip Operating System-generated cel files of three controls, four TU-treated individuals, and four TU + LNG-treated individuals were analyzed using GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies). Probe-level summarization was performed using the GeneSpring built-in GCRMA algorithm.

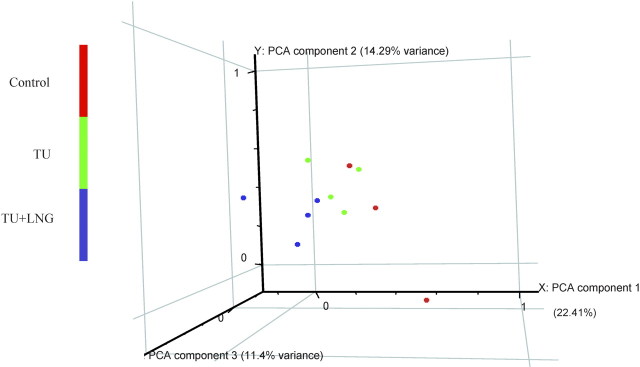

The data set was normalized with GeneSpring default/recommended normalization methods, including data transformation set measurements less than 0.01 to 0.01; per chip normalized to 50th percentile; and per gene normalized to median. Principal component analysis was used to visualize global gene expression distribution of each sample. Principal component analysis is a vector space transformation method used to reduce multidimensional data sets to lower dimensions for visualization and analysis. As shown in Figure 1, the three principal components accounted for 22.41%, 14.29%, and 11.4% of total variance, respectively. Although gene expression variability inevitably existed in the different subjects being studied, our principal component analysis showed that TU- and TU + LNG-treated samples were clustered together and were distinguishably different from the control samples, indicating that the effects due to the treatments (TU or TU + LNG) were significantly larger than the intragroup biological variation. To identify the differentially expressed genes regulated by either TU or TU + LNG treatment, the probe sets with raw intensities less than 50 in all 11 GeneChips were first filtered out, then one-way ANOVA was conducted on the remaining probe sets to detect the probe sets that were statistically significant (P < 0.05) among groups [12]. Differentially expressed probe sets (transcripts) were defined as those probe sets that showed at least 2-fold change in either direction with a statistically significant difference (t-test, P < 0.05) compared with the control group. To further investigate the difference in gene expression between TU alone and TU + LNG treatment, we conducted a Student t-test to determine the statistical difference between 109 transcripts induced by TU alone and 207 transcripts induced by TU + LNG.

Fig. 1.

Global gene expression distribution of each testicular RNA sample by principal component analysis (PCA), a vector space transformation method used to reduce multidimensional data sets to lower dimensions for visualization and analysis. The three principal components accounted for x-axis, 22.41%; y-axis, 14.29%; and z-axis, 11.4% of total variance, respectively. Principal component analysis showed that TU- and TU + LNG-treated samples were clustered distinguishably different from the control samples.

Gene Functional Annotation and Clustering Analysis

To identify biologically relevant groups of genes affected by the treatment of TU or TU + LNG, we performed gene functional annotation and cluster analysis using a program of the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) Bioinformatics Resources 2008 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. The DAVID 2008 Functional Annotation and Clustering provided statistical methods for discovering enriched biological themes and exploration of the functional processes enriched in a single gene list (e.g., the differentially expressed genes in TU alone or the differentially expressed genes in TU+LNG). The analysis does not directly compare groups per se. Hierarchical clustering analyses using GeneSpring Software grouped a similar pattern of differentially expressed transcripts in each group and allowed us to visualize the gene changes based on their expression pattern across different treatment conditions.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Bouin-fixed, paraffin-embedded testicular sections were deparaffinized, hydrated by successive series of ethanol, and rinsed in distilled water. Sections were incubated in 2% H2O2 to quench endogenous peroxidases. Sections were blocked with 5% normal horse serum for 20 min to suppress nonspecific binding of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and were subsequently incubated with a monoclonal insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP3) antibody (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at room temperature for 1 h. The negative controls were processed in an identical manner, except the primary antibody was substituted with an anti-trpE mouse monoclonal antibody. Immunoreactivity was detected using biotinylated anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody followed by avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex visualized with diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride per the manufacturer's instructions (mouse UniTectTM ABC Kit; Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA). Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin and viewed with the Zeiss Axioskop 40 microscope [13].

Results

Quantitative Changes in Gene Expression

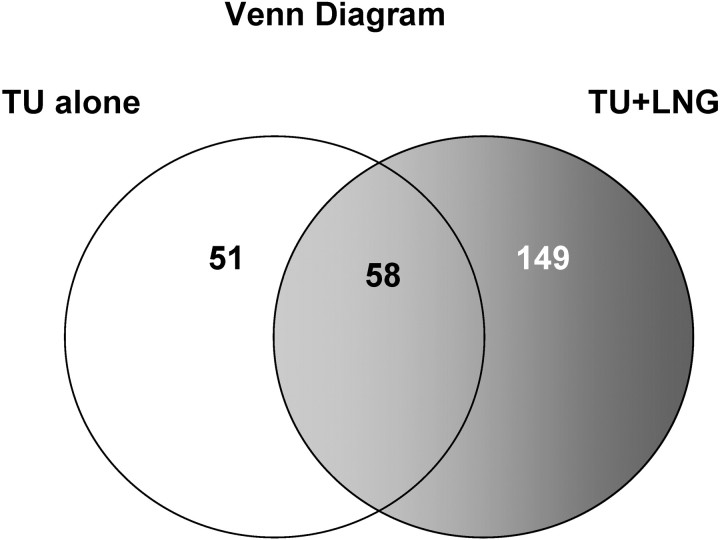

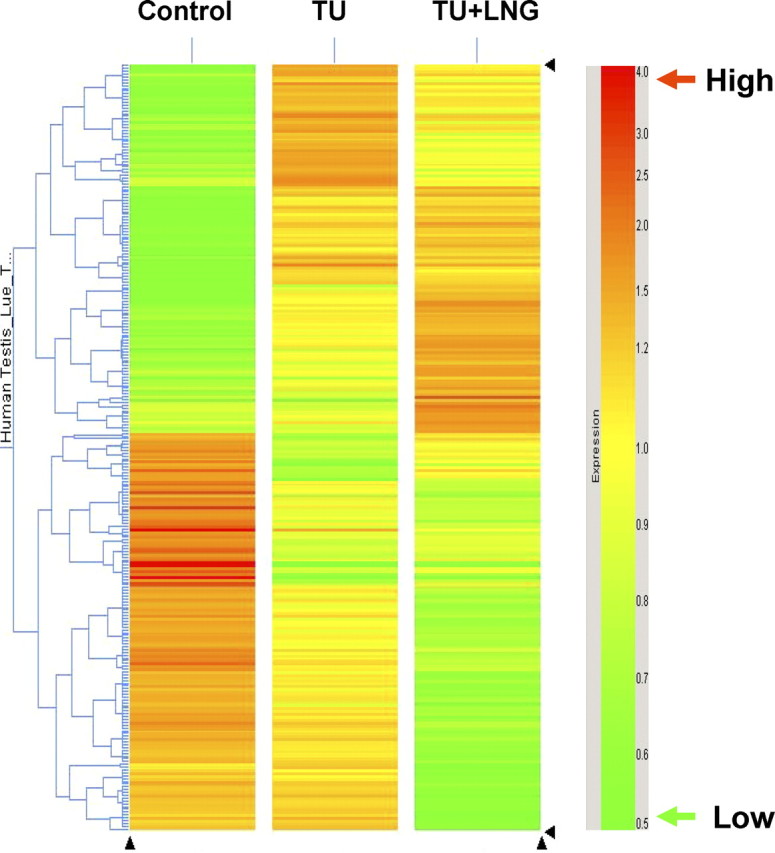

Administration of TU alone or TU + LNG suppressed gonadotropin secretion as previously reported [4]. The present study showed that after 2 wk of treatment, before any apparent loss of germ cells had occurred, TU + LNG treatment resulted in greater alteration of testicular gene expression than TU treatment alone (Figs. 2 and 3). Compared with controls, the statistically significant differentially expressed (P < 0.05) genes with ≥2-fold changes in TU alone and TU + LNG treatment groups are shown in Figure 2 and provided in Supplemental Data (available at www.biolreprod.org). The TU treatment alone induced a total of 109 genes with significant changes (≥2 fold; P < 0.05), in which 70 genes were upregulated and 39 genes were downregulated. In contrast, TU + LNG treatment induced significant changes (≥2 fold; P < 0.05) in 207 genes, including 92 upregulated and 115 downregulated genes. As shown in the Venn diagram (Fig. 3), when compared with the control group, TU treatment significantly altered the expression of 51 genes, whereas TU + LNG treatment significantly changed 149 genes. There were 58 genes showing the same changes caused by TU and TU + LNG treatments. We then directly compared the 109 transcripts induced by TU alone with the 207 transcripts induced by TU + LNG, and we found 63 transcripts in the TU + LNG group that were significantly (P < 0.05) altered that showed no change with TU alone. On the other hand, TU treatment resulted in eight transcripts with significant (P < 0.05) changes that were not observed in the TU + LNG treatment group (Supplemental Data).

Fig. 2.

Hierarchical clustering analysis showing the statistically significant (P < 0.05) transcripts with equal or more than 2-fold changes in gene expression in control and 2 wk after TU alone or TU + LNG treatment. Red color represents a high number of transcript expression. Green color represents a low number of transcript expression. Note the apparently greater alteration of testicular gene expression in TU + LNG than in TU treatment alone compared with controls.

Fig. 3.

Venn diagram shows that TU treatment alone caused 51 gene changes that were different from 149 gene changes in TU+LNG treatment; whereas, there were 58 common gene changes shared by both TU and/or TU+LNG treatment. When compared with control, TU+LNG treatment caused more changes of testicular gene expression than TU alone.

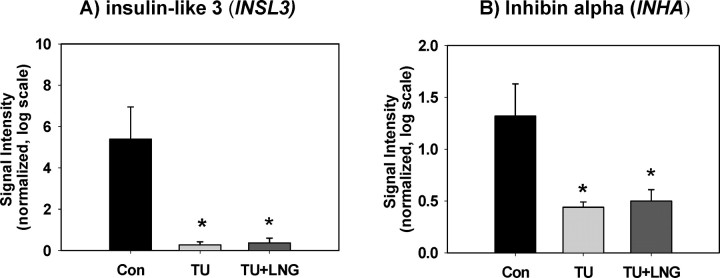

As expected, the expressions of a Leydig cell-specific gene, insulin-like 3 (INSL3), and a Sertoli cell-specific gene, inhibin alpha (INHA), were suppressed by both TU and TU + LNG treatments, respectively (Fig. 4). Both TU and TU + LNG treatments induced significant suppression of CYP17A1 gene expression compared with control in human testes.

Fig. 4.

The expressions of Leydig cell-specific gene INSL3 (A) and Sertoli cell-specific gene INHA (B) were suppressed by both TU and TU + LNG treatment. Asterisks indicate significant difference (P < 0.05) from control (Con). Error bars indicate standard errors of normalized signal intensity.

Effects of TU Treatment on Testicular Gene Expression

Functional annotated groups of genes that displayed significant transcriptional changes (P < 0.05) induced by TU alone are shown in Table 1. The major biologic processes affected by TU treatment were receptor binding, signal transduction, cytokine activity, growth factor activity, and apoptosis. Apoptotic signaling pathway genes were activated 2 wk after starting hormonal treatment. For example, TU treatment induced a 2.06-fold increase in IGFBP3 and a 2.02-fold increase in BCL2-like 14 (BCL2L14). Conversely, TU treatment alone resulted in a 2.11-fold decrease in X-liked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) and suppressed intratesticular growth factor gene expression. Growth differentiation factor 10 (GDF10) and nephroblastoma overexpressed gene (NOV) were decreased in 2.18-fold and 2.94-fold, respectively. The TU treatment also decreased cell cycle regulation gene CHK2 checkpoint homology (CHEK2) and transcription factor Dp-2 (TFDP2) expression by 2.72-fold and 2.82-fold, respectively.

Table 1.

Functional annotation of genes 2 wk after TU treatment.

| Term | Gene count | Involved genes/ total genes (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracelluar region | 14 | 14.1 | 0.002 |

| Cytokine activity | 6 | 6.1 | 0.005 |

| Receptor binding | 10 | 10.1 | 0.007 |

| Growth factor activity | 5 | 5.1 | 0.009 |

| Extracelluar space | 8 | 8.1 | 0.009 |

| Disufide bond | 16 | 16.2 | 0.015 |

| Growth factor | 4 | 4.0 | 0.018 |

| Signal | 20 | 20.2 | 0.018 |

| Signal peptide | 17 | 17.2 | 0.034 |

| Reproductive process | 5 | 5.1 | 0.04 |

| Cytokine | 4 | 4.0 | 0.04 |

| Development process | 21 | 21.2 | 0.046 |

| G-protein-coupled receptor binding | 3 | 3.0 | 0.047 |

| Hormone | 3 | 3.0 | 0.048 |

| Apoptosis | 8 | 8.1 | 0.05 |

Effects of TU treatment on testicular gene expression can be further shown in Figure 2: a group of genes at the top of the panel showing TU alone was significantly increased compared with control and moderately upregulated compared with TU + LNG treatment. For example, TU treatment alone significantly upregulated the gene expression of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 (CCL18), thrombopoietin (THPO), small heat shock protein B9 (HSPB9), and ribonuclease H1 (RNASEH1), which were not changed by TU + LNG treatment. Whether this implies different mechanisms of action of TU and LNG on some genes, differences in the levels of the hormones in the subjects, or differential sensitivity of the subjects in the two groups is not clear.

Effects of TU + LNG Treatment on Testicular Gene Expression

Functional annotated groups of genes that displayed significant transcriptional changes (P < 0.05) induced by TU + LNG treatment are shown in Table 2. Addition of LNG to TU treatment not only resulted in 63 expressed genes that were significantly different from TU treatment alone, but also affected the biologic processes of alternative splicing, RNA binding, GTPase binding, cell junction, and immune response (Table 2). In addition to the pathways activated by TU treatment alone, TU+LNG had a greater impact on insulin/IGF/relaxin signaling, posttranscriptional regulation, and apoptosis (Table 3). The TU + LNG treatment suppressed INSL3 gene expression and increased insulin-like 6 (INSL6) and relaxin 1 (RLN1) expression. Interestingly, TU + LNG treatment induced a significant (P < 0.05) suppression of a major proportion of the transcripts encoding RNA-binding proteins compared with TU treatment alone. Treatment with TU + LNG increased apoptosis-related molecules ring finger protein 216 (RNF216), and it decreased apoptosis inhibitor 5 (API5), death-associated protein 3 (DAP3), pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 (PLAGL1), and reticulon 4 (RTN4). In addition, PathwayArchitect analysis (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with genes differentially expressed in the TU + LNG treatment group suggested a possible functional linkage among IGFBP3, CHK2 checkpoint homolog (CHEK2), and cell division cycle 25C (CDC25C), which might be involved in the suppression of spermatogenesis in men (Table 3).

Table 2.

Functional annotation of genes 2 wk after TU+LNG treatment.

| Term | Gene count | Involved genes/ total genes (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular region | 22 | 10.6 | 0.002 |

| Insulin/IGF/relaxin | 3 | 1.4 | 0.005 |

| Immunoglobulin | 7 | 3.4 | 0.014 |

| Alternative splicing | 65 | 31.4 | 0.019 |

| Disulfide bond | 26 | 12.6 | 0.022 |

| Immunoglobulin-like | 10 | 4.8 | 0.022 |

| Reproduction | 11 | 5.3 | 0.026 |

| Signal peptide | 29 | 14.0 | 0.034 |

| Pleckstrin-like | 7 | 3.4 | 0.04 |

| GTPase binding | 4 | 1.9 | 0.04 |

| Hormone | 4 | 1.9 | 0.042 |

| Extracellular space | 10 | 4.8 | 0.045 |

| Intercellular junction | 5 | 2.4 | 0.046 |

| RNA binding | 6 | 2.9 | 0.047 |

| Nucleotide binding | 6 | 2.9 | 0.049 |

| Apoptosis | 13 | 6.3 | 0.05 |

Table 3.

Comparison of fold changes in selected testicular gene expression between TU and TU+LNG treatments.

| GenBank accession no. | Description | Gene symbol | TU vs. control fold change | TU+LNG vs. control fold change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Testicular cell specific markersa | ||||

| NM_000102 | Cytochrome P450, family 17, subfamily A, polypeptide 1 | CYP17A1 | −34.19 | −50.63 |

| AI991694 | Insulin-like 3 (Leydig cell) | INSL3 | −19.27 | −14.38 |

| M13981 | Inhibin, alpha | INHA | −2.97 | −2.63 |

| Insulin/IGF/relaxina | ||||

| NM_016421 | Insulin-like 6 | INSL6 | 1.57 | 2.10 |

| BC005956 | Relaxin 1 | RLN1 | 1.36 | 2.02 |

| Growth factor | ||||

| NM_000614 | Ciliary neurotrophic factor | CNTF | 2.54 | 1.26c |

| NM_004962 | Growth differentiation factor 10 | GDF10 | −2.18 | −2.08 |

| NM_002514 | Nephroblastoma overexpressed gene | NOV | −2.94 | −2.85 |

| AF523265 | Fibroblast growth factor 7 (keratinocyte growth factor) | FGF7(KGF) | −1.75 | −2.23 |

| Apoptosisa | ||||

| AW135003 | Apoptosis inhibitor 5 | API5 | −1.60 | −2.08 |

| BI826539 | Ring finger protein 216 | RNF216 | 3.94 | 2.62 |

| M31159 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 | IGFBP3 | 2.06 | 2.70 |

| AI335191 | Death associated protein 3 | DAP3 | −1.74 | −2.40 |

| AI554912 | BCL2-like 14 (apoptosis facilitator) | BCL2L14 | 2.02 | 2.38 |

| NM_006718 | Dleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 | PLAGL1 | −1.30 | −2.18c |

| BE380045 | X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis | XIAP | −2.11 | −1.56 |

| AW963634 | Reticulon 4 | RTN4 | −2.02 | −1.66 |

| Regulation of cell cycleb | ||||

| BC004207 | CHK2 checkpoint homolog (S. pombe) | CHEK2 | −2.72 | −2.60 |

| U20498 | Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D (p19, inhibits CDK4) | CDKN2D | 1.38 | 2.05c |

| AF277724 | Cell division cycle 25C | CDC25C | 1.16 | 2.01c |

| NM_006718 | Pleiomorphic adenoma gene-like 1 | PLAGL1 | −1.30 | −2.18c |

| AI049624 | Transcription factor Dp-2 (E2F dimerization partner 2) | TFDP2 | −2.82 | −1.85 |

| BG198711 | Protein kinase c, alpha | PRKCA | 2.83 | 1.96 |

| RNA bindinga | ||||

| AA865357 | Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein d | HNRNPD | −1.58 | −2.22c |

| AA831170 | Transformer-2 alpha | TRA2A | −1.36 | −2.11c |

| BE046511 | Formin binding protein 1 | FNBP1 | −1.81 | −2.20 |

| AL832250 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein polypeptide N | SNRPN | −1.75 | −2.11 |

| AA648521 | Splicing factor, arginine/serine-rich 15 | SFRS15 | −1.47 | −2.56c |

| AI697540 | Muscleblind-like (Drosophila) | MBNL1 | −1.12 | −2.26c |

| BC030757 | Polypyrimidine tract binding protein 2 | PTBP2 | −1.39 | −2.44c |

| AA279654 | Zinc finger protein 638 | ZNF638 | −1.52 | −2.24 |

| BC012090 | Heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A3 | HNRNPA3 | −2.14 | −1.38 |

| Cell junction and cytoskeleton organizationa | ||||

| AA913146 | Plakophilin 4 | PKP4 | −1.20 | −2.11c |

| AW151704 | Par-6 partitioning defective 6 homolog beta (C. elegans) | PARD6B | −1.13 | −2.02c |

| NM_001942 | Desmoglein 1 | DSG1 | 2.43 | 2.58 |

| NM_006035 | CDC42 binding protein kinase beta (DMPK-like) | CDC42BPB | −1.49 | −2.02 |

| NM_030772 | Gap junction protein, alpha 10, 59 kDa | GJA10 | 1.46 | 2.41 |

| AI027678 | Metastasis suppressor 1 | MTSS1 | 1.17 | 2.12c |

| AA971514 | Spectrin, beta, non-erythrocytic 1 | SPTBN1 | −1.43 | −2.06c |

| BF215673 | Kelch-like 4 (Drosophila) | KLHL4 | −3.22 | −2.86 |

| AA481044 | Formin-like 3 | FMNL3 | −1.93 | −2.04 |

| AA758906 | Katanin p60 subunit a-like 1 | KATNAL1 | 2.06 | 1.14 |

| BF215673 | Kelch-like 4 (Drosophila) | KLHL4 | −3.22 | −2.86 |

| NM_001069 | Tubulin, beta 2a | TUBB2A | 2.03 | 1.62 |

| Immune responsea | ||||

| NM_006332 | Interferon, gamma-inducible protein 30 | IFI30 | 2.18 | 1.49 |

| AB000221 | Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 18 | CCL18 | 2.79 | 1.98c |

| NM_005849 | Immunoglobulin superfamily, member 6 | IGSF6 | 2.03 | 1.33 |

| AI004137 | Inter-alpha (globulin) inhibitor H4 | ITIH4 | 2.76 | 1.79 |

| AF010316 | Prostaglandin E synthase | PTGES | −2.41 | −2.28 |

| NM_001565 | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | CXCL10 | 2.71 | 2.26 |

| D90427 | Alpha-2-glycoprotein 1, zinc | AZGP1 | −2.44 | −2.22 |

| U19556 | Serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade b (ovalbumin), member 3 | SERPINB3 | 1.86 | 2.15 |

| AV711904 | Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor-subfamily b | LILRB1 | 2.66 | 2.11 |

| L25259 | CD86 antigen (CD28 antigen ligand 2, B7–2 antigen) | CD86 | 4.27 | 3.26 |

| M17565 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II, DQ beta 1 | HLA-DQB1 | 1.35 | 2.19 |

Functional annotation classifications are significantly enriched (P < 0.05) using PathwayArchitect analysis (a) or NIH DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (b).

Gene with significant difference (P < 0.05) between TU and TU+LNG treatment.

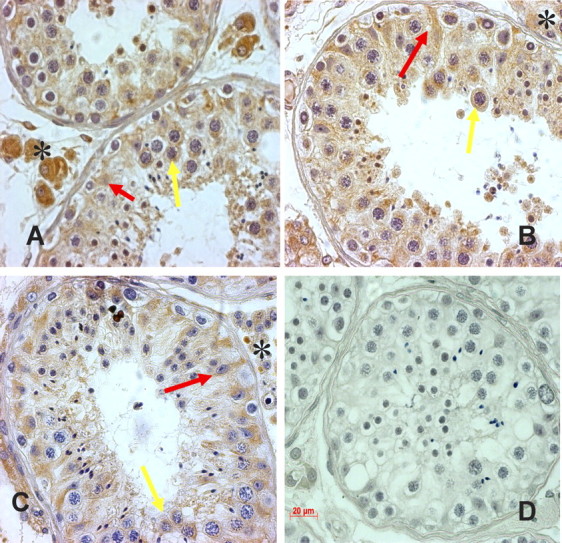

Immunolocalization of IGFBP3 in Human Testes

To further validate the correlation of transcript changes to their corresponding protein expression in human testes, we selected IGFBP3 as an example molecule to examine its localization by immunohistochemistry. We found that IGFBP3 was expressed and localized abundantly in Leydig cells and moderately in Sertoli cells and spermatocytes and round spermatids. After TU or TU + LNG treatment, there was apparently increased expression of IGFBP3 in Sertoli cells compared with controls (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Representative light micrographs showing immunostaining of IGFBP3 on testicular sections from control (A), 2 wk after TU alone (B), TU + LNG treatment (C), and negative control (D). IGFBP3 was localized abundantly in Leydig cells (asterisks), moderately in Sertoli cells (red arrows), and spermatocytes and round spermatids (yellow arrows). After TU or TU + LNG treatment, IGFBP3 expression appeared to be increased in Sertoli cells. Original magnification ×250; bar = 20 μm.

Discussion

Using RNA isolated from human testicular open biopsies, we were able to detect the effects of TU and TU + LNG on 38 500 gene expressions simultaneously in the testis. In fact, gene expression data generated from testicular biopsy represents a snapshot of gene transcription profile in a given time. We did not measure gonadotropin levels 2 wk after TU and TU + LNG treatment, but at 3 wk both LH and FSH were suppressed in both groups of men [4]. A recent microarray-based study on RNA from human testicular needle biopsies following 4 wk of gonadotropin suppression induced by gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist plus testosterone showed a small subset of gene changes involved in steroidogenesis, early meiosis, and Sertoli-germ cell junctions [14]. In the present study, we demonstrated that compared with control, TU + LNG induced more changes in gene expression (207 genes) than TU treatment (109 genes) at 2 wk. Comparing the gene expression between TU + LNG treatment and TU alone, we found 63 transcripts in the TU + LNG group were significantly (P < 0.05) altered that showed no change with TU treatment alone. In contrast, TU treatment only resulted in eight transcripts with significant (P < 0.05) changes that were not observed with TU + LNG treatment. This was probably due to earlier, consistent, and enhanced suppression of gonadotropin with combined TU + LNG treatment compared with TU alone [4, 15], although the possibility of direct action of the progestin on the testis cannot be excluded [16].

Our data showed the gene expressions of INSL3, a Leydig cell functional marker, and INHA, a Sertoli cell functional marker, were markedly suppressed after 2 wk of treatment with TU or TU + LNG. Insulin-like 3, also known as Leydig insulin-like protein or relaxinlike factor, is expressed in Leydig cells in testes and is responsible for the descent of the testis to the scrotum [17]. INSL3 deficiency in mice causes bilateral cryptorchidism [18, 19]. The TU + LNG-treated men who escape the complete spermatogenic suppression have higher serum INSL3 levels [20]. Thus, a decrease in INL3 gene expression provides further support that Leydig call function is suppressed by exogenous testosterone and progestin administration. Inhibin is a gonadal glycoprotein hormone secreted by the Sertoli cells that regulates FSH secretion, and it also functions in vivo as a tumor suppressor in the mouse gonads [21]. Decreased INHA expression after testicular hormonal deprivation suggests Sertoli cell function is suppressed by exogenous hormone treatment. Suppression of Leydig and Sertoli cell functional markers due to inhibition of gonadotropin secretion after exogenous TU and TU + LNG treatment is anticipated and substantiates the validity of our gene microarray data.

We demonstrated that both TU and TU + LNG treatment suppressed the gene expression of CYP17A1 encoding 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (a rate-limiting steroidogenic enzyme for testosterone production in Leydig cells). In addition to its well-known function in the androgen biosynthesis in Leydig cells, a recent study reported that 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase encoded by CYP17A1 is present in germ cells and essential for sperm function. Haploinsufficiency of CYP17 is a cause of male infertility in mice [22, 23]. Thus, TU + LNG-induced rapid suppression of spermatogenesis may be due to a marked suppression of CYP17A1 in Leydig cells induced by a greater suppression of gonadotropin. However, a direct action of LNG on germ cell development may be another possible explanation.

We have demonstrated previously that one of the major mechanisms of suppression of spermatogenesis caused by deprivation of hormones in the testis is due to increased germ cell apoptosis [4–6, 24]. Our gene microarray experiment confirmed that both TU and TU + LNG treatment activated the apoptotic signaling pathway in the testis. We found, for example, that both TU and TU + LNG treatment increased proapoptotic BCL2-like 14 expression and decreased antiapoptotic X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) [25]. BCL2-like 14 (BCL2L14) is a novel proapoptotic member of the BCL2 family. BCL2L14 encodes two proteins through alternative mRNA splicing, BCL2L14L (long) and BCL2L14s (short). BCL2L14L mRNA is expressed widely in adult human tissues, whereas BCL2L14s mRNA is found only in testis and is more potent in inducing apoptosis than BCL2L14L [26]. XIAP inhibits apoptosis by inhibiting caspases [27].

We also demonstrated that both TU and TU + LNG treatments increased the expression of IGFBP3. IGFBP3, the major circulating carrier protein for IGF1, is active in the cellular environment as a potent antiproliferative agent. The increased IGFBP3 gene expression after TU or TU + LNG treatment suggests that this protein may participate in the suppression of spermatogenesis by binding to IGF1 and IGF2 to reduce the bioavailability of these two paracrine growth factors for both spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis [28–31]. IGFBP3 causes cell cycle blockage and induces apoptosis [32, 33]. IGFBP3 has been reported to be localized in rat Leydig cells and porcine Sertoli cells [34, 35]. We showed by immunohistochemistry that IGFBP3 was expressed and localized in Leydig cells, Sertoli cells, spermatocytes, and round spermatids in human testes. Thus, IGFBP3 may have an action in male germ cells that are independent of sequestration of IGFs and may induce apoptosis directly similar to its proapoptotic actions in the prostate and other tissues [36, 37].

Functional clustering analysis showed that TU + LNG treatment activated insulin/IGF/relaxin signaling pathway in human testes. The TU + LNG treatment induced increases in expression of RLN1 and INSL6. Relaxin protein shares structure similarity with insulin and IGFs. The major physiologic function of relaxin is its actions on collagen remodeling. Mice with relaxin overexpression are fertile [38]. Relaxin knockout male mice show delayed tissue maturation and growth in the testes, epididymides, and prostate associated with increased collagen deposition [39]. INSL6, a member of the insulin gene family, is expressed in human testes, and its transcripts are localized in spermatocytes and round spermatids [40]. INSL6 is a secreted protein localized to the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi in transfected cells [41]. However, the physiologic role of relaxin and insulin-like 6 in testes remains to be determined.

RNA-binding proteins play pivotal roles in the regulation of spermatogenesis. In comparison with TU treatment alone, addition of LNG to TU significantly suppressed a major portion of transcripts encoding RNA-binding proteins. Interestingly, a group of downregulated transcripts (HNRNPA3, HNRNPD, SNRPN, TRA2A, and SFRS15) encode RNA-binding proteins that act on pre-mRNA processing. We have demonstrated that spermatocytes and round spermatids are cells most susceptible to apoptosis in response to both testicular hormonal deprivation and elevated testicular temperature [42]. A growing body of literature demonstrated that disruption of RNA-binding proteins that are involved RNA processing, transport, and metabolism in testes resulted in infertility that mainly affects meiotic and postmeiotic germ cell development [43–45]. Thus, our data generated from human testis samples provided evidence showing that the rapid suppression of spermatogenesis induced by TU + LNG treatment may be the consequence of suppression of RNA-binding protein expression decreasing the gene posttranscription machinery in human testes.

Spermatogenesis includes precisely regulated mitosis and meiosis. Cell cycle regulation is another critical process affected by both TU and TU + LNG treatments. We found the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2D (CDKN2D), also known as p19INK4d, was increased. The protein encoded by CDKN2D is a member of the INK4 family of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors that can block cell cycle G1 progression. CDKN2D is mainly localized in spermatocytes, with some expression in the spermatids of human testes [46]. Evidence from CDKN2D-deficient mice indicates CDKN2D is involved in the transition from mitotic to meiotic division in germ cells [47, 48]. Increased expression of CDKN2D at 2 wk after treatment suggests that TU + LNG treatment suppresses B spermatogonia entering into meiosis in human testes. In addition, TU + LNG treatment altered CHK2 checkpoint homolog (CHEK2) and cell division cycle 25C (CDC25C) gene expression. CHK2 encodes checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2), which can be rapidly activated in response to replication blocks and DNA damage. The activated CHK2 inhibits CDC25C phosphatase to prevent cell entry into the cell cycle [49]. CHK2 is localized abundantly in adult spermatogonia and weakly in some spermatocytes of human testes [50]. Phosphatase CDC25C is localized to the nucleus of late spermatocytes and round spermatids of rodent testes [51, 52]. The downregulation of CHEK2 and upregulation of CDC25C indicate that TU + LNG treatment may weaken the cell cycle checkpoint and allow accumulation of DNA damage to trigger apoptosis.

Both TU and TU + LNG treatment induced alteration of gene expression related to cell junctional molecules and immune response in testes. Androgen may regulate the permeability of the blood-testis barrier. Sertoli cell-specific ablation of androgen receptor results in increased permeability of the blood-testis barrier to biotin in mice [53]. Our gene microarray data showed that both TU and TU + LNG treatment increased expression of desmoglein 1 (DSG1), one of the molecules forming desmosome, and gap junction protein alpha 10 (GJA10). The TU + LNG treatment decreased the expression of plakophilin 4 (PKP4) and par-6 partitioning-defective 6-homolog beta (PARD6B), which may be involved in regulating junctional plaque organization and formation of epithelial tight junctions. In addition, clinical studies have shown a positive correlation between progesterone concentration and increased inflammatory cytokines in healthy men [54]. Both TU and TU + LNG treatment upregulated transcripts encoding proteins related to antigen presentation, which include interferon gamma-inducible protein 30 (IFI30), Cd86 antigen (CD86), leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor subfamily B (LILRB1), major histocompatibility complex class II (HLA-DQB1), chemokine ligand 18 (CCL18), and chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10). CXCL10, also known as interferon-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10), is a potent chemokine expressed predominantly by macrophages and Leydig cells in the testis [55, 56]. Overexpression of CXCL10 by transfection in mouse Leydig MA-10 cells inhibits STAR D1 expression, decreases progesterone synthesis, and inhibits cell proliferation [57]. Thus, we speculate that the hormonal deprivation in human testes may result in a weakened blood-testis barrier and cause germ cell-specific antigen release from the luminal compartment of the seminiferous tubule into interstitial space to trigger the autoimmune response in the testis. In turn, immune response cytokines generated from macrophages and Leydig cells may diffuse into the seminiferous tubules to trigger germ cell apoptosis.

Taken together, we demonstrated that testosterone plus LNG induced suppression of spermatogenesis, which is most likely mediated through transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. Administration of TU or TU + LNG not only suppresses gonadotropin levels but also inhibits the bioavailability of growth factors and RNA-binding proteins. The demonstration of significant upregulation of proapoptotic and downregulation of antiapoptotic transcripts further supports our belief that apoptosis is one of the major mechanisms resulting in suppression of spermatogenesis induced by intratesticular hormonal deprivation. We demonstrated for the first time that the rapid suppression of spermatogenesis by adding LNG to TU was due to activation of insulin/IGF/relaxin-related pathways and suppression of the availability of a major portion of RNA-binding proteins in human testes. We propose that increased IGFBP3 in the testes may play an important role in suppression of spermatogenesis by sequestering IGF's bioavailability and inducing germ cell apoptosis, leading to azoospermia and severe oligozoospermia. Importantly, our study has provided a novel and valuable database for the study of hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis in men and the discovery of testicular-specific molecules that may serve as potential targets for male contraceptive development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Zugen Zhen at the UCLA DNA Microarray Core for performing the microarray experiments.

References

- 1. Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Male hormonal contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004; 190:S60–S68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bebb RA, Anawalt BD, Christensen RB, Paulsen CA, Bremner WJ, Matsumoto AM. Combined administration of levonorgestrel and testosterone induces more rapid and effective suppression of spermatogenesis than testosterone alone: a promising male contraceptive approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996; 81:757–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang C, Wang XH, Nelson AL, Lee KK, Cui YG, Tong JS, Berman N, Lumbreras L, Leung A, Hull L, Desai S, Swerdloff RS. Levonorgestrel implants enhanced the suppression of spermatogenesis by testosterone implants: comparison between Chinese and non-Chinese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:460–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang C, Cui YG, Wang XH, Jia Y, Sinha Hikim AP, Lue YH, Tong JS, Qian LX, Sha JH, Zhou ZM, Hull L, Leung A et al. Transient testicular hyperthermia enhanced spermatogenesis suppression by testosterone in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92:3202–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lue YH, Sinha Hikim AP, Wang C, Im M, Leung A, Swerdloff RS. Testicular heat exposure enhances the suppression of spermatogenesis by testosterone in rats: the “two-hit” approach to male contraceptive development. Endocrinology 2000; 141:1414–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lue YH, Wang C, Liu YX, Hikim AP, Zhang XS, Ng CM, Hu ZY, Li YC, Leung A, Swerdloff RS. Transient testicular warming enhances the suppressive effect of testosterone on spermatogenesis in adult cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Donnell L, Narula A, Balourdos G, Gu YQ, Wreford NG, Robertson DM, Bremner WJ, McLachlan RI. Impairment of spermatogonial development and spermiation after testosterone-induced gonadotropin suppression in adult monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86:1814–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McLachlan RI, O'Donnell L, Meachem SJ, Stanton PG, de Kretser DM, Pratis K, Robertson DM. Identification of specific sites of hormonal regulation in spermatogenesis in rats, monkeys, and man. Recent Prog Horm Res 2002; 57:149–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ruwanpura SM, McLachlan RI, Matthiession KL, Meachem SJ. Gonadotrophins regulate germ cell survival, not proliferation, in normal adult men. Hum Reprod 2008; 23:403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McLachlan RI, O'Donnell L, Stanton PG, Balourdos G, Frydenberg M, de Kretser DM, Robertson DM. Effects of testosterone plus medroxyprogesterone acetate on semen quality, reproductive hormones, and germ cell populations in normal young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:546–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cui Y, Zhu H, Zhu Y, Guo X, Huo R, Wang X, Tong J, Qian L, Zhou Z, Jia Y, Lue YH, Hikim AS et al. Proteomic analysis of testis biopsies in men treated with injectable testosterone undecanoate alone or in combination with oral levonorgestrel as potential male contraceptives. J Proteome Res 2008; 7:3984–3993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guo L, Lobenhofer EK, Wang C, Shippy R, Harris SC, Zhang L, Mei N, Chen T, Herman D, Goodsaid FM, Hurban P, Phillips KL et al. Rat toxicogenomic study reveals analytical consistency across microarray platforms. Nat Biotechnol 2006; 24:1162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lue YH, Sinha Hikim AP, Wang C, Leung A, Swerdloff RS. Functional role of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the induction of male germ cell apoptosis, regulation of sperm number, and determination of testes size: evidence from null mice. Endocrinology 2003; 144:3092–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bayne RA, Forster T, Burgess ST, Craigon M, Walton MJ, Baird DT, Ghazal P, Anderson RA. Molecular profiling of the human testis reveals stringent pathway-specific regulation of RNA expression following gonadotropin suppression and progestogen treatment. J Androl 2007; 29:389–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McLachlan RI, Robertson DM, Pruysers E, Ugoni A, Matsumoto AM, Anawalt BD, Bremner WJ, Meriggiola C. Relationship between serum gonadotropins and spermatogenic suppression in men undergoing steroidal contraceptive treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89:142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walton MJ, Bayne RAL, Wallace I, Baird DT, Anderson RA. Direct effect of progesterone on gene expression in the testis during gonadotropin withdrawal and early suppression of spermatogenesis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91:2526–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Burkhardt E, Adham IM, Brosig B, Gastmann A, Mattei MG, Engel W. 1994 Structural organization of the porcine and human genes coding for a Leydig cell-specific insulin-like peptide (LEY I-L) and chromosomal localization of the human gene (INSL3). Genomics 1994; 20:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zimmermann S, Steding G, Emmen JMA, Brinkmann AO, Nayernia K, Hiostein AF, Engel W, Adham IM. Targeted disruption of the Insl3 gene causes bilateral cryptorchidism. Mol Endocrinol 1999; 13:681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tomboc M, Lee PA, Mitwally MF, Schneck FX, Bellinger M, Witchel SF. Insulin-like 3/Relaxin-like factor gene mutations are associated with cryptorchidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85:4013–4018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Amory JK, Page ST, Anawalt BD, Coviello AD, Matsumoto AM, Bremner WJ. Elevated end-of-treatment serum INSL3 is associated with failure to completely suppress spermatogenesis in men receiving male hormonal contraception. J Androl 2007; 28:548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matzuk MM, Finegold MJ, Su JG, Hsueh AJ, Bradley A. Alpha-inhibin is a tumour-suppressor gene with gonadal specificity in mice. Nature 1992; 360:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y, Yao ZX, Bendavid C, Borgmeyer C, Han Z, Cavalli LR, Chan WY, Folmer J, Zirkin BR, Haddad BR, Gallicano I, Rapadopoulos V. Happloinsufficiency of cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17) causes infertility in male mice. Mol Endocrinology 2005; 19:2380–2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Y, Dettin LE, Folmer J, Zirkin BR, Papadopoulos V. Abnormal morphology of spermatozoa in cytochrome P450 17α-hydoxylase/17, 20-lyase (CYP17) deficient mice. J Androl 2007; 28:453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sinha Hikim AP, Rajavashisth TB, Sinha Hikim I, Lue YH, Bonavera JJ, Leung A, Wang C, Swerdloff RS. Significance of apoptosis in the temporal and stage-specific loss of germ cells in the adult rat after gonadotropin deprivation. Biol Reprod 1997; 57:1193–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duckett CS, Nava VE, Gedrich RW, Clem RJ, Van Dongen JL, Gilfillan MC, Shiels H, Hardwick JM, Thompson CB. A conserved family of cellular genes related to the baculovirus IAP gene and encoding apoptosis inhibitors. EMBO J 1996; 15:2685–2694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guo B, Godzik A, Reed JC. Bcl-G, a novel pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl-2 family. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:2780–2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Deveraux QL, Takahashi R, Salvesen GS, Reed JC. X-linked IAP is a direct inhibitor of cell-death protease. Nature 1997; 388:300–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soder O, Bang P, Wahab A, Parvinen M. Insulin-like growth factors selectively stimulate spermatogonial, but not meiotic, deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis during rat spermatogenesis. Endocrinology 1992; 131:2344–2350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhou J, Bondy C. Anatomy of the insulin-like growth factor system in the human testis. Fertil Steril 1993; 60:897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang G, Hardy MP. Development of Leydig cells in the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) knockout mouse: effects of IGF-1 replacement and gonadotropic stimulation. Biol Reprod 2004; 70:632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Colon E, Zaman F, Axelson M, Larsson O, Carlsson-skwirut C, Svechnikov KV, Soder O. Insulin-like growth factor-1 is an important antiapoptotic factor for rat Leydig cells during postnatal development. Endocrinology 2007; 148:128–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baxter BC. Signalling pathways involved in antiproliferative effects of IGFBP-3: a review. Mol Pathol 2001; 54:145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cohen P. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3: insulin-like growth factor independence comes of age. Endocrinology 2006; 147:2109–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang D, Nagpal ML, Shimasaki S, Ling N, Lin T. Interleukin-1 induces insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 gene expression and protein production by Leydig cells. Endocrinology 1995; 136:4049–4055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Besset V, Le Magueresse-Battistoni B, Collette J, Benahmed M. Tumor necrosis factor alpha stimulates insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 expression in cultured porcine Sertoli cells. Endocrinology 1996; 137:296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Butt AJ, Firth SM, King MA, Baxter RC. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 modulates expression of Bax and Bcl-2 and potentiates p53-independent radiation-induced apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:39174–39181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee K, Ma L, Yan X, Liu B, Zhang X, Cohen P. Rapid apoptosis induction by IGFBP-3 involves an insulin-like growth factor-independent nucleomitochondrial translocation of RXRa/Nur77. J Biol Chem 2005; 280:16942–16948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feng S, Bogatcheva NV, Kamat AA, Truong A, Agoulnit AI. Endocrine effects of relaxin overexpression in mice. Endocrinology 2006; 147:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, Du XJ, Summers RJ, Amento EP, Walker LL, McBurnie M, Zhao L, Tregear GW. The relaxin gene-knock mouse: a model of progressive fibrosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2005; 1041:173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lok S, Johnston DS, Conklin D, Lofton-Day CE, Adams RL, Jelmberg AC, Whitmore TE, Schrader S, Griswold MD, Jaspers SR. Identification of INSL6, a new member of the insulin family that is expressed in the testis of the human and rat. Biol Reprod 2000; 62:1593–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lu C, Walker WH, Sun J, Weisz OA, Gibbs RB, Witchel SF, Sperling MA, Menon RK. Insulin-like peptide 6: characterization of secretory status and posttranslational modifications. Endocrinology 2006; 147:5611–5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lue YH, Sinha Hikim AP, Swerdloff RS, Im P, Khay ST, Bui T, Leung A, Wang C. Single exposure to heat induces stage-specific germ cell apoptosis in rats: role of intratesticular testosterone on stage specificity. Endocrinology 1999; 40:1709–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tanaka SS, Toyooka Y, Akasu R, Katoh-Fukui Y, Nakahara Y, Suzuki R, Yokoyama M, Noce T. The mouse homolog of Drosophila vasa is required for the development of male germ cells. Genes Dev 2000; 14:841–853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Schrans-Stassen BH, Saunders PT, Cooke HJ, de Rooij DG. Nature of the spermatogenic arrest in Dazl-/- mice. Biol Reprod 2001; 65:771–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsai-Morris CH, Sheng Y, Lee E, Lei KJ, Dufau ML. Gonadotropin-regulated testicular RNA helicase (GRTH/Ddx25) is essential for spermatid development and completion of spermatogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101:6373–6378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bartkova J, Thulberg M, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebek NE, Bartek J. Lack of p19INK4d in human testicular germ cell tumors contrasts with high expression during normal spermatogenesis. Oncogene 2000; 19:4146–4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zindy F, van Deursen J, Grosveld G, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. INK4d-deficent mice are fertile despite testicular atrophy. Mol Cell Biol 2000; 20:372–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zindy F, den Besten W, Chen B, Rehg JE, Latres E, Barbacid M, Pollard JW, Sherr CJ, Cohen PE, Roussel M. Control of spermatogenesis in mice by the cyclin D-dependent kinase inhibitors p18INK4d and p19INK4d. Mol Cell Biol 2001; 21:3244–3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Matsuoka S, Huang M, Elledge S. J. Linkage of ATM to cell cycle regulation by Chk2 protein kinase. Science 1998; 282:1893–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bartkova J, Falck J, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebek NE, Lukas J, Bartek J. Chk2 tumor suppressor protein in human spermatogenesis and testicular germ-cell tumour. Oncogene 2001; 20:5897–5902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wolgemuth DJ, Wu S. The distinct and developmentally regulated patterns of expression of members of the mouse cdc25 gene family suggest differential functions during gametogenesis. Dev Biol 1995; 170:195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mizoguchi S, Kim KH. Expression of cdc25 phosphatases in the germ cells of the rat testis. Bio Reprod 1997; 56:1474–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meng J, Holdcraft RW, Shima JE, Griswold MD, Braun RE. Androgen regulates the permeability of the blood-testis barrier. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 96:319–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Zitzmann M, Erren M, Kamischke A, Simoni M, Nieschlag E. Endogenous progesterone and the exogenous progestin norethisterone enanthate are associated with a proinflammatory profile in health men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 90:6603–6608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hu J, You S, Li W, Wang D, Nagpal ML, Mi Y, Liang P, Lin T. Expression and regulation of interferon-r-inducible protein 10 gene in rat Leydig cells. Endocrinology 1998; 139:3637–3645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Goffic RL, Mouchel T, Aubry F, Patard J, Ruffault A, Jegou B, Samson M. Production of the chemokines monocyte chemotactic protein-1, regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted protein, growth-related oncogene, and interferon-r-inducible protein-10 is induced by the sendai virus in human and rat testicular cells. Endocrinology 2002; 143:1434–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nagpal ML, Chen Y, Lin T. Effects of overexpression of CXC10 (cytokine-responsive gene-2) on MA-10 mouse Leydig tumor cell steroidogenesis and proliferation. J Endocrinol 2004; 183:585–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.