Summary

Aims

To evaluate in a real‐world setting the effectiveness and tolerability of available GLP‐1 RA drugs in patients with type 2 diabetes after a prolonged follow‐up.

Materials and methods

Observational, retrospective, single‐centre study in patients starting GLP‐1 RA therapy. Change in HbA1c, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) and body mass index (BMI) along with gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events and withdrawal from GLP‐1 RA therapy were evaluated. Lack of efficacy of GLP‐1 RA therapy according to prespecified goals was also measured.

Results

A total of 735 patients were included, mean age 59.7 years, duration of diabetes 9.01 years, HbA1c 8.18% and BMI 38.56 kg/m2. Average follow‐up was 18.97 months (range 4.2‐39.09). All HbA1c (0.93%; P < 0.01), FPG (24 mg/dL; P < 0.01) and BMI (1.55 kg/m2; P < 0.05) were significantly reduced from baseline and maintained throughout follow‐up, regardless of prescribed GLP‐1 RA. GI adverse events were present in 13.81% of patients at first follow‐up visit, 37.07% of patients discontinued GLP‐1 RA treatment, and 38.63% did not meet efficacy goals.

Conclusions

In a real‐world setting, GLP‐1 RA therapy is largely prescribed in severely obese patients with a long‐standing and poorly controlled diabetes. All prescribed GLP‐1 RAs significantly decreased HbA1c, FPG and BMI. GI adverse events affected a low proportion of patients. Inversely, a high proportion of patients did not meet efficacy goals and/or discontinued GLP‐1 RA treatment. Baseline characteristics of patients and lack of adherence may represent important issues underlying differences in effectiveness in real‐world studies versus randomized trials.

Keywords: GLP‐1 receptor agonist, glycaemic control, observational study

1. INTRODUCTION

The glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist (GLP‐1 RA) pharmacological class is increasingly becoming a widely prescribed therapy in type 2 diabetes (T2D) based upon a robust hypoglycaemic effect mediated through stimulation of β‐cells aimed to enhance insulin secretion in a glucose‐dependent manner, while simultaneously suppressing the secretion of glucagon from α‐cells. Besides, GLP‐1 RAs are able to prolong gastric emptying and induce satiety with a potential to reduce body weight, a major factor contributing to insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia in T2DM.1, 2 Clinical trials have demonstrated that GLP‐1 RA therapy is able to reduce glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) by 1.0% from baseline values with a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia compared with sulfonylurea and insulin.3, 4 Furthermore, many of these agents induce significant weight loss.3, 4 Nevertheless, clinically meaningful differences have been described in head‐to‐head trials in regard of the magnitude of the effect on these outcomes associated to different drugs of the class, with a higher effect on weight and glucose reduction for liraglutide and weekly‐based therapies, that is exenatide LAR and dulaglutide, as compared with daily‐based ones, exenatide and lixisenatide.5, 6

In addition to improving hyperglycaemia, GLP‐1 RAs also counteract other diabetes‐associated conditions, including obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidaemia.7, 8 Furthermore, some GLP‐1 RAs have demonstrated certain anti‐atherosclerotic properties, as improvement of endothelial dysfunction and reduction of inflammatory markers and oxidative stress.9 Such a comprehensive pharmacological profile is probably underlying a growing evidence for a potential cardiovascular risk reduction of the class.10, 11, 12, 13 Indeed, a recent meta‐analysis by Bethel et al14 has shown a consistent effect of GLP‐1 RAs included in reducing CV risk, with no evidence for further safety concerns beyond GI tolerance.

Following the regulatory approval of different GLP‐1 RAs, providing real‐world evidence for the effectiveness and safety of the class under routine clinical practice conditions is an important step in confirming the clinical benefits/risks expected, based on the approved label. Most of the retrospective studies published so far in the real‐world (RW) setting have been designed with a limited follow‐up period of 6‐12 months. Even in this scenario, some authors have found a significantly poorer performance of GLP‐1 RAs in terms of efficacy outcomes, as compared to those on randomized control trials (RCTs).15, 16, 17 Lack of therapeutic adherence and different baseline patients’ demographics probably rely as important determinants of this gap between RCTs and RW studies.18, 19 Thus, concerns about effectiveness in real‐world do exist and more retrospective studies with appropriate long‐term follow‐up are needed to better characterize the clinical profile of this therapeutic class.

The aim of this long‐term observational, retrospective, single‐centre study was to evaluate in a real‐world setting the effectiveness, tolerability and therapeutic adherence of all available GLP‐1 RAs prescribed under routine clinical practice, and evaluate the baseline characteristics of T2DM patients acceding to this therapy since this drug class became available in Spain with the introduction of exenatide in 2009.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

Hospital records from all patients in which a GLP‐1 RA treatment was newly prescribed from January 2009 to December 2016 at our tertiary hospital (Son Espases University Hospital, Palma de Mallorca, Spain) were collected and retrospectively reviewed. Off‐label prescriptions for type 1 diabetic patients and nondiabetic obese patients were excluded from analysis. Given the reimbursement conditions implemented by Spanish Health authorities, all included patients were 18‐year‐old or older, had a diagnosis of T2DM on previous oral antidiabetic medications and had a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2. All study investigators were endocrinologists working for the Endocrinology Department at Son Espases University Hospital, representing the usual setting where GLP‐1 RA treatments are initiated in Spain. Given the observational retrospective nature of this study, individual consent was not required after ensuring for anonymization of data.

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Research Committee and the Institutional Ethical Review Board, and the study was conducted in compliance with the ethics guidelines for research in humans as recorded in the International Guidelines for Ethical Review of Epidemiological Studies and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964.

2.2. Outcomes and variables measured

Hospital records were used to retrospectively assess patients’ characteristics at baseline (visit in which a GLP‐1 RA was first prescribed), and then every 6 months intervals until 24 months of follow‐up. For those patients with available hospital records beyond 24 months, last hospital visit available was selected and included in the analysis.

Variables evaluated at baseline visit included patients’ demographics, duration of diabetes, background antidiabetic therapy, anthropometric measurements (height, weight and BMI) and laboratory variables (fasting plasma glucose and HbA1c), as well as type and dosage of GLP‐1 RA initially prescribed. Subsequent visits additionally included changes in HbA1c, FPG and BMI as efficacy variables, change of GLP‐1 RA type or dose (if applicable), self‐reported gastrointestinal adverse events (including nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhoea) and GLP‐1 RA therapy discontinuation, if applicable. Further evaluation of clinical effectiveness was performed based upon an arbitrary definition derived from NICE guidelines20: Therapy with GLP‐1 RA would be considered effective if a HbA1c reduction ≥0.5% and/or a weight reduction ≥3% was achieved after at least 6 months of follow‐up.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Categorical data are shown in percentages. All continuous variables were tested and proved to follow a normal distribution, being expressed as mean (± standard deviation). Two‐sided homo/heteroscedastic Student t tests were used for comparison of parametrically distributed baseline data. ANCOVA tests for repeated measures were performed to compare baseline data versus follow‐up data. A P < 0.05 value was assumed for statistical significance (Statplus statistical package 2016©, AnalystSoft, Walnut, CA).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 735 out of 844 patients with a GLP‐1 RA first prescription from 2009 to 2016 met criteria to undergo further analysis. Patients excluded from final analysis included those with off‐label prescriptions and patients without adequate hospital records, to ensure quality of data.

Global and index drug‐specific baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 1. Sex was equally distributed for both global and index drug‐specific groups. Patients starting on exenatide LAR once weekly (EXE OW) were significantly older as compared to those starting on liraglutide (LIRA) or dulaglutide (DULA); 60.08 ± 10.1 years old vs 57.9 ± 11.08 and 58.8 ± 10.9 years old, respectively (P < 0.05), but patients on DULA presented a longer T2DM duration as compared to LIRA and EXE OW; 11.3 ± 9.6 years vs 8.1 ± 6.6 and 9.2 ± 6.06 years, respectively (P < 0.05). No differences were found for HbA1c and FPG at baseline, but LIRA patients were significantly more obese (39.8 ± 6.9 kg/m2) than EXE OW (37.55 ± 5.9 kg/m2, P < 0.001) or DULA patients (37.38 ± 6.8 kg/m2, P < 0.05). Patients on DULA presented a significantly higher number of background antidiabetic medications (2.51 ± 1.00) as compared to LIRA and EXE OW patients (2.17 ± 0.97 and 2.13 ± 0.98, respectively; P < 0.05), mostly driven by a significantly higher proportion of patients on basal insulin (52.63% vs 32.75% and 36.42%; P < 0.01). 83.23% of patients on LIRA maintained a 1.2 mg/d dose by first follow‐up visit (16.77% on 1.8 mg/d) which gradually declined to 35.53% by last follow‐up visit (64.47% on 1.8 mg/d); on average, 59.46% remained on 1.2 mg/day. A very high proportion of patients starting lixisenatide (LIXI) were treated with insulin (94.06%), as this was the first GLP‐1 RA to receive approval from Spanish Health authorities for concomitant treatment with basal insulin. Globally, a very low number of patients were shifted to a different GLP‐1 RA during follow‐up (47, 6.39%) and most of these changes accounted for exenatide twice daily (EXE) transferred to LIRA (24, 22.2%). A subsequent analysis of this subgroup of patients showed no significant changes in HbA1c or weight reductions. No patients were initially or subsequently treated with albiglutide in this cohort.

Table 1.

All drugs and index‐drug[Link] specific baseline characteristics

| All drugs | EXE BID | LIX | LIRA | EXE OW | DULA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 735 | 108 (14.69) | 51 (6.93) | 328 (44.62) | 176 (23.94) | 72 (9.79) |

| Age (±SD) | 59.7 ± 10.5 | 61.08 ± 9.6 | 63.4 ± 8.4 | 57.9 ± 11.08 | 60.08 ± 10.1* | 58.8 ± 10.9 |

| Male sex (%) | 50 | 54 | 55 | 47 | 53 | 49 |

| DM duration (years ±SD) | 9.01 ± 7.4 | 8.4 ± 5.9 | 12.5 ± 7.1*** | 8.1 ± 6.6 | 9.2 ± 6.06 | 11.3 ± 9.6* |

| HbA1c (±SD) | 8.18 ± 1.5 | 7.87 ± 1.5 | 8.21 ± 1.1 | 8.22 ± 1.6 | 8.20 ± 1.3 | 8.38 ± 1.7 |

| FPG mg/dL (±SD) | 177 ± 59 | 168 ± 54 | 174 ± 48 | 177 ± 62 | 182 ± 59 | 178 ± 65 |

| BMI (±SD) | 38.56 ± 6.6 | 37.55 ± 6.2 | 37.10 ± 6.5 | 39.8 ± 6.9 | 37.55 ± 5.9*** | 37.38 ± 6.8* |

| GLP‐1 RA change (%) | 6.39 | 23.1 | 9.8 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 1.4 |

| Other ADM. N (±SD) | 2.18 ± 0.99 | 1.92 ± 1.05 | 2.64 ± 0.86*** | 2.17 ± 0.97 | 2.13 ± 0.98 | 2.51 ± 1.00* |

| Metformin (%) | 91.29 | 88.79 | 88.02 | 94.15 | 88.44 | 94.74 |

| SU (%) | 31.46 | 36.46 | 19.93 | 32.35 | 34.10 | 21.05 |

| DPP‐IV‐I (%) | 37.24 | 19.81 | 38.07 | 41.29 | 38.73 | 42.11 |

| Pioglitazone (%) | 1.69 | 3.78 | 1.96 | 1.55 | 1.16 | 1.75 |

| SGLT2‐I (%) | 3.79 | 0.93 | 2.02 | 10.84 | 5.78 | 10.53 |

| Basal insulin (%) | 39.04 | 28.01 | 94.06 | 32.75 | 36.42 | 52.63 |

| Bolus insulin (%) | 18.38 | 18.92 | 38.07 | 17.32 | 11.11 | 28.57 |

ADM, antidiabetic medications; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; DPP‐IV‐I, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitor; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SD, Standard deviation; SGLT2‐I, sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea.

Index‐drug: EXE BID: Exenatide twice daily; LIX: Lixisenatide; LIRA: Liraglutide; EXE OW: Exenatide once weekly; DULA: Dulaglutide.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001 for exenatide twice daily vs lixisenatide or exenatide once weekly and dulaglutide vs liraglutide. Two‐sided t test for parametric variables.

Table 2 shows bi‐yearly evolution of baseline characteristics and preferences for prescription. Overall, prescription of GLP‐1 RA in our diabetic population has increased constantly, with a clear preference for LIRA and weekly‐based drugs (EXE OW and DULA), as these drugs were becoming available, over EXE and LIXI. A change was seen in patients’ baseline profile in time, as those starting a GLP‐1 RA in 2015‐2016 presented a significantly higher duration of diabetes, higher HbA1c at baseline and higher number of background antidiabetic medications, mostly dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV (DPP‐IV) inhibitors, sodium‐glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT‐2) inhibitors and insulin, as compared to patients starting therapy early in 2009‐10.

Table 2.

Bi‐yearly evolution of baseline characteristics

| All drugs | 2009‐10 | 2011‐12 | 2013‐14 | 2015‐16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 735 | 66(8.98) | 175 (23.80) | 211 (28.70) | 283 (38.5) |

| Age (±SD) | 59.7 ± 10.5 | 60.9 ± 10.7 | 60.5 ± 10.5 | 59.1 ± 10.3 | 58.9 ± 10.8 |

| Male sex (%) | 50 | 50 | 51 | 46 | 52 |

| DM duration (years ±SD) | 9.01 ± 7.4 | 7.49 ± 5.2 | 8.91 ± 7.7 | 8.90 ± 7.0 | 9.51 ± 7.8* |

| HbA1c (±SD) | 8.18 ± 1.5 | 7.84 ± 1.5 | 8.22 ± 1.7 | 8.01 ± 1.4 | 8.36 ± 1.4* |

| FPG mg/dL (±SD) | 177 ± 59 | 175 ± 61 | 173 ± 60 | 174 ± 54 | 182 ± 62 |

| BMI (±SD) | 38.56 ± 6.6 | 37.72 ± 7.2 | 39.85 ± 6.9 | 38.99 ± 6.4 | 37.60 ± 6.3 |

| Other ADM. N (±SD) | 2.18 ± 0.99 | 1.89 ± 1.0 | 2.03 ± 0.95* | 2.21 ± 0.99* | 2.31 ± 0.99** |

| Metformin (%) | 91.29 | 89.23 | 94.12 | 90.69 | 90.48 |

| SU (%) | 31.46 | 44.62 | 35.88 | 32.84 | 24.54 |

| DPP‐IV‐I (%) | 37.24 | 21.88 | 29.17 | 43.63 | 41.03 |

| Pioglitazone (%) | 1.69 | 3.13 | 2.37 | 1.96 | 0.74 |

| SGLT2‐I (%) | 3.79 | 0.0 | 0.59 | 0.98 | 8.79 |

| Basal insulin (%) | 39.04 | 24.62 | 28.24 | 37.75 | 50.18 |

| Bolus insulin (%) | 18.38 | 13.85 | 17.58 | 18.32 | 20.07 |

| Index drug, n (%) | |||||

| Exenatide bid | 108 (14.69) | 64 (96.92) | 30 (17.14) | 11 (5.21) | 3 (1.06) |

| Lixisenatide | 51 (6.93) | 0 | 0 | 44 (20.85) | 7 (2.47) |

| Liraglutide | 328 (44.62) | 2 (3.08) | 145 (82.85) | 112 (53.08) | 69 (24.38) |

| Exenatide OW | 176 (23.94) | 0 | 0 | 44 (20.85) | 132 (46.64) |

| Dulaglutide | 72 (9.79) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 72 (25.44) |

ADM, antidiabetic medications; BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; DPP‐IV‐I, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitor; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; SD, Standard deviation; SGLT2‐I, sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01 vs 2009‐10. ANCOVA test for repeated measures.

3.2. Effectiveness and tolerability outcomes

Table 3 reflects evolution of main clinical efficacy outcomes, HbA1c, FPG and BMI in subsequent follow‐up visits, tolerability, measured by incidence (first follow‐up visit) and prevalence (further follow‐up) of GI side effects (nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or diarrhoea) and persistence on GLP‐1 RA treatment. Changes in background antidiabetic medication after introduction of GLP‐1 RA therapy are also described. For those patients with follow‐up longer than 24 months, last available hospital visit records were included for analysis, with an average follow‐up period of 39 months (±12.9, SD).

Table 3.

Evolution of (A) efficacy and tolerability outcomes and (B) background antidiabetic therapy after introduction of GLP‐1 RA

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | 39 months[Link] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 735 | 548 | 421 | 283 | 188 | 163 |

| HbA1c (%) (±SD) | 8.18 ± 1.53 | 7.24 ± 1.45*** | 7.29 ± 1.51*** | 7.15 ± 1.29*** | 7.23 ± 1.30*** | 7.25 ± 1.33*** |

| FPG (mg/dL) (±SD) | 177 ± 59 | 145 ± 51*** | 153 ± 53*** | 146 ± 47*** | 149 ± 43*** | 153 ± 52** |

| BMI (kg/m2) (±SD) | 38.56 ± 6.6 | 37.05 ± 6.1** | 37.21 ± 6.8** | 36.90 ± 6.0* | 36.88 ± 5.8* | 37.01 ± 6.1* |

| GI AE (%) | 13.81 | 5.57 | 2.65 | 2.45 | 2.10 | |

| Withdrawal (%) | 21.58 | 15.25 | 15.47 | 12.05 | 18.06 | |

| Lack of efficacy[Link] (%) | 18.31 | 19.22 | 18.01 | 12.93 | 18.57 | |

| Other ADM. n (±SD) | 2.18 ± 0.99 | 1.80 ± 0.78*** | 1.77 ± 0.80*** | 1.79 ± 0.81*** | 1.74 ± 0.78*** | 1.75 ± 0.80*** |

| Metformin (%) | 91.29 | 92.76 | 93.75 | 93.56 | 92.77 | 94.44 |

| SU (%) | 31.46 | 29.71 | 28.25 | 30.04 | 32.53 | 32.87 |

| DPP‐IV‐I (%) | 37.24 | 6.11 | 3.50 | 4.55 | 2.41 | 1.39 |

| Pioglitazone (%) | 1.69 | 0.96 | 1.26 | 1.9 | 1.81 | 3.47 |

| SGLT2‐I (%) | 3.79 | 6.11 | 5.76 | 6.82 | 6.63 | 11.11 |

| Basal insulin (%) | 39.04 | 36.12 | 34.84 | 34.09 | 30.12 | 29.17 |

| Bolus insulin (%) | 18.38 | 9.92 | 10.35 | 10.69 | 10.84 | 6.25 |

ADM, antidiabetic medications; BMI, body mass index; DPP‐IV‐I, dipeptidyl peptidase‐IV inhibitor; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; GI AE, gastrointestinal adverse events; HbA1c, Glycated haemoglobin; SD, standard deviation; SGLT2‐I, sodium‐glucose cotransporter‐2 inhibitor; SU, sulfonylurea.

Lack of efficacy defined as HbA1c reduction <0.5% and/or BMI reduction <3% after 6 months of follow‐up.

Last available hospital visit for patients with follow‐up visits beyond 24 months.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.001 vs baseline. ANCOVA test for repeated measures.

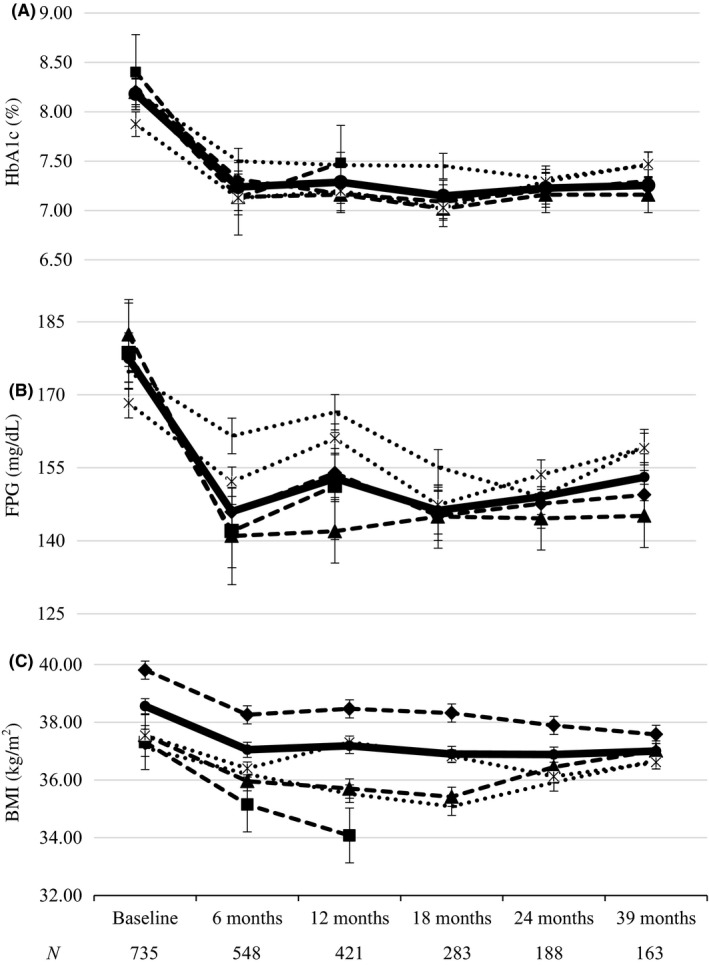

Overall, all GLP‐1 RA drugs significantly reduced baseline HbA1c with no significant differences among them (Figure 1A). Most of the HbA1c reduction was achieved by 6‐month visit and maintained throughout follow‐up, with a final HbA1c reduction of −0.93% vs baseline (8.18 ± 1.53 vs 7.25 ± 1.33; P < 0.001, ANCOVA test for repeated measures). FPG was significantly reduced from baseline by all GLP‐1 RAs but a trend towards a greater reduction for LIRA and weekly‐based EXE OW and DULA was seen, as compared to daily‐based EXE and LIXI (Figure 1B). All GLP‐1 RA induced a significant weight loss from baseline with a final difference of −1.55 kg/m2 (38.56 ± 6.6 vs 37.01 ± 6.1; P < 0.05, ANCOVA test for repeated measures), which represented a final weight loss of 4.74 kg (105.36 ± 20.11 vs 100.62 ± 18.59 kg), and a 4.49% reduction of initial body weight. As stated before, LIRA patients presented a significantly higher baseline BMI (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Evolution of A, HBA1C; B, FPG and C, BMI during follow‐up at 6‐month intervals. ( ) DULA; (

) DULA; ( ) EXE OW; (

) EXE OW; ( ) EXE BID; (

) EXE BID; ( ) LIXI; (

) LIXI; ( ) LIRA and (

) LIRA and ( ) GLOBAL. BMI, Body mass index; DULA, Dulaglutide; EXE BID, Exenatide twice daily; EXE OW, Exenatide once weekly; FPG, Fasting plasma glucose; HBA1C, Glycated haemoglobin; LIRA, Liraglutide; LIX, Lixisenatide. Bars represent Standard Deviation

) GLOBAL. BMI, Body mass index; DULA, Dulaglutide; EXE BID, Exenatide twice daily; EXE OW, Exenatide once weekly; FPG, Fasting plasma glucose; HBA1C, Glycated haemoglobin; LIRA, Liraglutide; LIX, Lixisenatide. Bars represent Standard Deviation

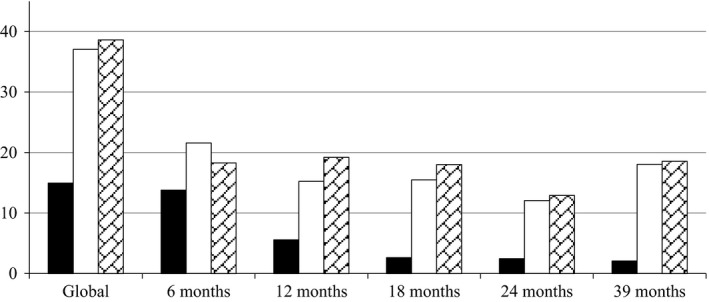

A low proportion of GLP‐1 RA treatments did not reach efficacy predefined as a reduction of HbA1c <0.5% or BMI <3% vs baseline, beyond 6 months of follow‐up. This proportion remained fairly constant (12.93%‐19.22%) among visits and resulted somewhat similar to the proportion of patients discontinuing GLP‐1 RA treatment (12.05%‐21.58%) at every follow‐up visit. Overall withdrawal rate was 37.07% (272 patients) and overall lack of efficacy was 38.64% (284 patients; Figure 2). Tolerance, measured by proportion of patients complaining from GI adverse events, showed a low initial incidence of 13.81% with a significant reduction on subsequent follow‐up visits. After the first year of follow‐up, only 5.57% of patients complained of GI adverse events, and this proportion was further reduced below 3% in subsequent follow‐up visits. Initial GI adverse events were reported by 25% of patients on EXE, 6% on LIXI, 10% on LIRA, 15% on EXE OW and 19% on DULA, respectively (Figure 2). Three cases of acute pancreatitis were retrospectively detected in this cohort of patients. One patient had a history of alcohol abuse and in two additional patients a diagnosis of gall bladder stone disease was performed after Hospital admission. In all cases, GLP‐1 RA therapy was stopped following patient discharge from Hospital. No cases of thyroid medullary carcinoma were detected during follow‐up. Furthermore, 12 patients with morbid obesity underwent bariatric surgery throughout follow‐up and GLP‐1 RA therapy was subsequently stopped in all of them.

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients: ■, with gastrointestinal adverse eventsa; □, withdrawn from GLP‐1 RA treatmentb and ( ), lacking efficacy for HBA1C or BMI reductionc. BMI, Body mass index; HbA1c, Glycated Haemoglobin. Solid Bar: Gastrointestinal adverse events; Empty Bar: Patients withdrawn from GLP‐1 RA therapy; Grid Bar: Lack of efficacy for HbA1c or BMI. aGastrointestinal adverse events included nausea, vomits, abdominal pain and/or diarrhoea. bGLP‐1 RA treatment withdrawn was based upon either patient's or physician's decision. cLack of efficacy for HbA1c or BMI reduction was defined by achievement of at least 0.5% of HbA1c and/or at least 3% BMI reduction versus baseline after at least 6 months of follow‐up

), lacking efficacy for HBA1C or BMI reductionc. BMI, Body mass index; HbA1c, Glycated Haemoglobin. Solid Bar: Gastrointestinal adverse events; Empty Bar: Patients withdrawn from GLP‐1 RA therapy; Grid Bar: Lack of efficacy for HbA1c or BMI. aGastrointestinal adverse events included nausea, vomits, abdominal pain and/or diarrhoea. bGLP‐1 RA treatment withdrawn was based upon either patient's or physician's decision. cLack of efficacy for HbA1c or BMI reduction was defined by achievement of at least 0.5% of HbA1c and/or at least 3% BMI reduction versus baseline after at least 6 months of follow‐up

Finally, Table 3 reflects changes in background therapy after introduction of GLP‐1 RA treatment. Early in follow‐up, a significant reduction in number of antidiabetic drugs was observed (2.18 ± 0.99 vs 1.80 ± 0.78 at 6 months; P < 0.001, ANCOVA test for repeated measures) and as expected, this reduction was mostly driven by a nearly total fall in use of DPP‐IV inhibitors. Conversely, a progressive increase in concomitant use with SGLT‐2 inhibitors was seen, while SU use remained fairly constant. Of note, in 25.28% of patients on basal insulin and in 66.0% on bolus insulin at baseline, insulin therapy was completely withdrawn in subsequent follow‐up visits.

4. DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study represents the longest observational retrospective analysis published to date, including all GLP‐1 RA drugs available in Spain. Globally, its results confirm the long‐term effectiveness and safety of treatment with this therapeutic class as per routine clinical practice in a tertiary hospital setting, despite a significantly different baseline profile of patients at baseline as compared to randomized clinical trials. Inversely, a low therapeutic adherence measured by persistence on treatment was documented, despite a low incidence of gastrointestinal adverse events.

4.1. Baseline characteristics of patients

In our cohort, patients starting on a GLP‐1 RA treatment were older, significantly more obese and their diabetes had a longer duration as compared to patients included in phase III RCTs from development programmes of liraglutide,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 exenatide LAR27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 and dulaglutide.33 Overall, patients included in these trials had an average age of 55.7 years (vs 59.7 years old in our cohort), a diabetes duration of 7.2 years (vs 9.01 years in our cohort) and a baseline BMI of 32.26 kg/m2 (vs 38.56 kg/m2 in our cohort). Interestingly, HbA1c at baseline in phase III RCTs was rather similar to that of our cohort (8.28% vs 8.18%, respectively).

As expected from a cohort followed at a tertiary centre, complexity of treatment was high, as confirmed by a long duration of diabetes and a high proportion of patients being already on basal insulin (39.04%) or on basal‐bolus regimes (18.38%). An even distribution of patients on sulfonylurea (31.46%) and DPP‐IV inhibitors (37.24%) completed the baseline profile of antidiabetic medications in this group. As patients were consecutively included in the study from 2009 to 2016, a specific evolution of baseline characteristics was found, with a trend towards a younger age and lower baseline BMI in later years. Conversely, we observed a longer duration of diabetes and a higher HbA1c, along with a higher proportion of patients with more background antidiabetic medications and a higher proportion of patients on insulin treatment. A possible explanation for this finding might be the increasing use of SGLT‐2 and DPP‐IV inhibitors, reflecting patients or physicians’ preference for noninjectable therapies. Moreover, as newer weekly‐based agents became available, a clear preference for them was observed, especially in the last two years of the observation period, where exenatide LAR and dulaglutide accounted for up to 72% of new prescriptions. Nevertheless, a low proportion of patients shifted to a different GLP‐1 RA agent from another, with the exception of 23% of patients on exenatide twice daily who migrated mostly to liraglutide.

Baseline characteristics of our cohort seem to be in line with other published real‐world observational studies. In Spain, Mezquita et al published in 2015 the eDiabetes Monitor Study,34 a nation‐wide multicentre observational study including 753 patients followed for one year after introduction of liraglutide. Baseline characteristics of patients included 55.6 years of age, 10.0 years of diabetes duration, baseline BMI of 38.6 kg/m2 and HbA1c of 8.4%. In this study, 27% of patients were on insulin treatment and 73.5% of patients maintained the 1.2 mg dose of liraglutide, as opposed to 59.46% in our study. Gorgojo et al have recently published the CIBELES study,35 a multicentre observational study including patients from four tertiary hospitals in Madrid, where 148 patients were retrospectively followed for one year after introduction of exenatide LAR. Again, patients at baseline were 58.0 years old and had a high BMI (38.4 kg/m2), but a lower HbA1c (7.7%) and shorter duration of diabetes (6.0 years). A possible explanation for these differences, despite a similar hospital setting, could be that patients on prior insulin therapy were specifically excluded in this study. Lapolla et al36 have recently published a long‐term multicentre retrospective study including 1723 patients from different diabetes centres throughout Italy, evaluating effectiveness and tolerability after introduction of liraglutide. Not surprisingly, average age at baseline was 58.9 years old, duration of diabetes was 9.6 years, and HbA1c was 8.3%. In this study, BMI at baseline was one of the lowest published so far in real‐world studies (35.6 kg/m2). A possible explanation for this lower baseline BMI could rely on a high proportion of patients on metformin monotherapy at baseline (46.6%) and a very low proportion of patients on concomitant treatment with insulin (5.8%), reflecting a lower complexity of diabetes in this cohort. At 12 months, 58.5% of patients were on 1.2 mg/d of liraglutide. Due to its late approval, very scarce data are available on RW studies with dulaglutide. Mody et al37 have published a retrospective analysis of patients included in the HealthCore Integrated Research Database intended to evaluate effectiveness and therapeutic adherence among patients initiating dulaglutide treatment. A total of 308 patients were included with a follow‐up of 6 months. Baseline age was 53 years old and HbA1c 8.49%. No data were provided for baseline BMI, weight loss or duration of diabetes.

Other RW studies worldwide have shown similar patients baseline characteristics pointing towards older age and significantly higher BMI as compared to those on clinical trials, yet with a similar HbA1c.38, 39, 40, 41 These differences, especially regarding BMI, might reflect an unrealistic approach of prescribing physicians based upon the anti‐obesity effect of the class. Indeed, in a meta‐analysis of GLP‐1 RA head‐to‐head trials performed by Trujillo et al6 a range of 1.3‐3.8 kg weight loss was observed for different GLP‐1 RAs, which does not seem to preclude a very optimistic impact on weight for patients with such high BMIs. Nevertheless, more data are needed regarding weight loss, as combination therapy with SGLT‐2 inhibitors and GLP‐1 RAs is becoming more prevalent in T2DM population and randomized trials are offering promising results.42, 43

4.2. Effectiveness and tolerability

Our data showed a significant reduction of baseline HbA1c, FPG and BMI for the GLP‐1 RA class, achieved early since the first follow‐up visit. No differences were seen for different drugs in terms of HbA1c reduction, although exenatide twice daily and lixisenatide showed a trend for a lower fasting plasma glucose reduction as compared to liraglutide and weekly‐based GLP‐1 RAs. This observation makes sense from a pharmacokinetic point of view, based upon their lower plasma half‐life as compared to other drugs of the class and is in line with observations derived from phase III trials.21, 28, 33 At final follow‐up visit, a sustained reduction of HbA1c of 0.93% was achieved, along with a reduction of FPG of 24 mg/dL, both in keeping with reductions observed in many other RW studies with different GLP‐1 RA molecules.34, 35, 36, 37 Nevertheless, when these results are compared to those of RCTs, differences are noticeable. Taken together, average reduction of baseline HbA1c from phase III trials with liraglutide (LEAD 1‐6 trials), exenatide LAR (DURATION 1‐6 trials) and dulaglutide (AWARD 1‐6 trials) was 1.33%. Carls et al16 have highlighted this difference pointing towards a lack of therapeutic adherence and differences in baseline characteristics of patients as the main drivers for the gap in efficacy outcomes between RW studies and RCTs. As noted before, our cohort included older patients with longer duration of diabetes, treated with larger numbers of antidiabetic medications (including a higher proportion of patients on insulin treatment) as compared to RCTs, despite a similar baseline HbA1c. On the other hand, in our study we found a constant withdrawal rate of around 15% of patients in every follow‐up visit, with a total discontinuation rate of 37.07%, which indeed is higher than drop‐out rate found in phase III trials mentioned before. As per the retrospective design of this study, no other treatment adherence measurements could be carried out.

All drugs significantly reduced BMI throughout follow‐up visits, but considering the important differences observed in baseline BMI of different GLP‐1 RAs, direct comparisons among agents in this setting would be undoubtedly biased. Interestingly, the higher BMI at baseline observed in our cohort deemed a greater weight loss (4.74 kg) as compared to RCTs. Average weight reduction in LEAD, DURATION and AWARD programmes was 2.4 kg. This observation is confirmed by other RW studies with weight reductions ranging from 3.4 to 4.5 kg.34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Thong and colleagues critically evaluated NICE recommendations on use of GLP‐1 RA therapy,44 concluding that few patients achieved proposed criterion of HbA1c reduction ≥1% as a requirement for continued GLP‐1ra treatment as this would unfairly favour patients with higher baseline HbA1c. They recommended that this should be replaced by a target HbA1c reduction that is indexed to an individual's baseline HbA1. Following these criteria, and based upon a general recommendation for antidiabetic therapy, we evaluated clinical effectiveness of GLP‐1 RA in our cohort with a modified definition, including a HbA1c reduction of ≥0.5%. Conversely, and based upon the same reasoning by Thong and colleagues, a BMI reduction of ≥3% was considered appropriate, for a cohort with a high baseline BMI. In this context, we found that 38.63% of patients did not reach efficacy goals for HbA1c or weight reduction, taken together.

Gastrointestinal adverse events were self‐reported by a low proportion of patients, 14.96%, most of them by the first follow‐up visit, which is in line with data from RCTs and other RW studies.6, 35, 36 Interestingly, proportion of patients who discontinued treatment coincided to a large extent with proportion of patients lacking efficacy as per our proposed definition. Globally, 37.07% of patients withdrew from GLP‐1 RA treatment. These observations raise the possibility that in this cohort, lack of efficacy rather than tolerance might be the main reason for discontinuation of therapy. It is our sense that unaccomplished great expectations on weight reduction for both, patients and physicians, might underlay this withdrawal rate.

Our study has several weaknesses. First, its single‐centre design might make it unsuitable for generalized conclusions, but as observed, main results are absolutely in line with other large multi‐centre RW studies. Second, all GLP‐1 RAs have been included in the analysis, when it is clear that routine clinical practice is putting aside short acting GLP‐1 RAs exenatide and lixisenatide. Nevertheless, efficacy outcomes have shown few differences among drugs, specially in HbA1c reduction. Finally, due to late approval of dulaglutide use in Spain, few patients with shorter follow‐up on this drug have been included in the analysis. Main strengths of our study include a high number of patients followed for a long period of time. A total of 163 patients were followed for an average of 39 months, representing to our knowledge the longest follow‐up period included in a RW study.

In conclusion, our long‐term observational study has shown that all GLP‐1 RAs effectively reduced HbA1c and weight, despite significant differences in baseline characteristics, in a large cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes with severe obesity. A high proportion of patients discontinued treatment despite a low proportion of GI side effects, probably based upon a perception of lack of effectiveness, although rejection of injectable therapy and cost may probably play an important role too. More RW studies are needed, specially aimed to disclose factors affecting lack of efficacy and treatment adherence. Physicians worldwide probably need to reconsider a high BMI rather than suboptimal HbA1c as a leading reason to introduce a GLP‐1 RA agent in the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

This study was supported by a grant from AstraZeneca (Grant ES‐2018‐1154). Authors do not declare any further conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed significantly to the protocol design, data collection, data analysis and critical review of the final manuscript. Dr Tofé led the protocol design, data collection, data analysis and writing and submission of the manuscript.

PRIOR PUBLICATION

No part of the submitted work has been published or is under consideration for publication elsewhere. Part of this research was accepted as poster presentations at the 2017 Spanish Diabetes Society Congress.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Research Committee and the Institutional Ethical Review Board, and the study was conducted in compliance with the ethics guidelines for research in humans as recorded in the International Guidelines for Ethical Review of Epidemiological Studies and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964. Given the observational retrospective nature of this study, individual consent was not required after ensuring for anonymization of data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from AstraZeneca. Marta Alegría and Antonio Adrián González from AstraZeneca critically reviewed the protocol. The authors wish to thank the Endocrinology and Nutrition Department and Son Espases University Hospital for support in the conduction of this study.

Tofé S, Argüelles I, Mena E, et al. Real‐world GLP‐1 RA therapy in type 2 diabetes: A long‐term effectiveness observational study. Endocrinol Diab Metab. 2019;2:e51 10.1002/edm2.51

DATA ACCESSIBILITY

Database has been backed‐up and securely stored for accessibility and review if applicable.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP‐1 and GIP. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2131‐2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nauck M. Incretin therapies: highlighting common features and differences in the modes of action of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitors. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(3):203‐216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Karagiannis T, Liakos A, Bekiari E, et al. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2015;17(11):1065‐1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aroda VR, Henry RR, Han J, et al. Efficacy of GLP‐1 receptor agonists and DPP‐4 inhibitors: meta‐analysis and systematic review. Clin Ther. 2012;34(6):1247‐1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xue X, Ren Z, Zhang A, Yang Q, Zhang W, Liu F. Efficacy and safety of once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists compared with exenatide and liraglutide in type 2 diabetes: a systemic review of randomised controlled trials. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70(8):649‐656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Trujillo JM, Nuffer W, Ellis SL. GLP‐1 receptor agonists: a review of head‐to‐head clinical studies. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2015;6(1):19‐28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vilsboll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK, Gluud LL. Effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:d7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu FP, Dong JJ, Yang Q, et al. Glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonist therapy is more efficacious than insulin glargine for poorly controlled type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Diabetes. 2015;7:322‐328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Drucker DJ. The cardiovascular biology of glucagon‐like peptide‐1. Cell Metab. 2016;24:15‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2247‐2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown‐Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311‐322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holman RR, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once‐weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(13):1228‐1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1834‐1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bethel MA, Patel RA, Merrill P, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta‐analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(2):105‐113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Buysman EK, Liu F, Hammer M, Langer J. Impact of medication adherence and persistence on clinical and economic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with liraglutide: a retrospective cohort study. Adv Ther. 2015;32(4):341‐355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carls GS, Tuttle E, Tan RD, et al. Understanding the gap between efficacy in randomized controlled trials and effectiveness in real‐world use of GLP‐1 RA and DPP‐4 therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(11):1469‐1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Edelman SV, Polonsky WH. Type 2 Diabetes in the real world: the elusive nature of glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(11):1425‐1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garcia‐Perez LE, Alvarez M, Dilla T, Gil‐Guillen V, Orozco‐Beltran D. Adherence to therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4:175‐219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kurlander JE, Kerr EA, Krein S, Heisler M, Piette JD. Cost‐related nonadherence to medications among patients with diabetes and chronic pain: factors beyond finances. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2143‐2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. NICE guideline [NG28] . Type 2 diabetes in adults: management. Published date: December 2015 Last updated: July 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28. Accessed June, 2018.

- 21. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G, et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week randomised, parallel‐group, multinational, open‐label trial (LEAD‐6). Lancet. 2009;374:39‐47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐3 Mono): a randomised, 52‐week, phase III, double‐blind, parallel‐treatment trial. Lancet. 2009;373:473‐481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once‐daily human GLP‐1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐1 SU). Diabet Med. 2009;26:268‐278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)‐2 study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:84‐90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russell‐Jones D, Vaag A, Schmitz O, et al. Liraglutide vs insulin glargine and placebo in combination with metformin and sulfonylurea therapy in type 2 diabetes mellitus (LEAD‐5 met+SU): a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2046‐2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zinman B, Gerich J, Buse JB, et al. Efficacy and safety of the human glucagon‐like peptide‐1 analog liraglutide in combination with metformin and thiazolidinedione in patients with type 2 diabetes (LEAD‐4 Met+TZD). Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1224‐1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Diamant M, GaalL V, Guerci B, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus insulin glargine for type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐ 3): 3‐year results of an open‐label randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(6):464‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Buse JB, Drucker DJ, Taylor KL, et al. DURATION‐1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(6):1255‐1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bergenstal RM, Wysham C, Macconell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus sitagliptin or pioglitazone as an adjunct to metformin for treatment of type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐2): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9739):431‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Russell‐Jones D, Cuddihy RM, Hanefeld M, et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once weekly versus metformin, pioglitazone, and sitagliptin used as monotherapy in drug‐naïve patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐4): a 26‐week double‐blind study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(2):252‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J, et al. DURATION‐5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1301‐1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐6): a randomised, open‐label study. Lancet. 2013;381(9861):117‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Umpierrez GE, Pantalone KM, Kwan AY, Zimmermann AG, Zhang N, Fernández Landó L. Relationship between weight change and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes receiving once‐weekly dulaglutide treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2016;18(6):615‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mezquita‐Raya P, Reyes‐Garcia R, Moreno‐Perez O, et al. Clinical effects of liraglutide in a real‐world setting in Spain: eDiabetes‐Monitor SEEN Diabetes Mellitus Working Group Study. Diabetes Ther. 2015;6(2):173‐185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gorgojo‐Martínez JJ, Gargallo‐Fernández MA, Brito‐Sanfiel M, Lisbona‐Catalan A. Real‐world clinical outcomes and predictors of glycaemic and weight response to exenatide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes: The CIBELES project. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72(3):e13055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lapolla A, Berra C, Boemi M, et al. Long‐term effectiveness of liraglutide for treatment of type 2 diabetes in a real‐life setting: A 24‐month, multicentre, non‐interventional, retrospective study. Adv Ther. 2018;35(2):243‐253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mody R, Grabner M, Yu M, et al. Real‐world effectiveness, adherence and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus initiating dulaglutide treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2018;34(6):995‐1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Evans M, McEwan P, O'Shea R, George L. A retrospective, case‐note survey of type 2 diabetes patients prescribed incretin‐based therapies in clinical practice. Diabetes Ther. 2013;4(1):27‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lee WC, Dekoven M, Bouchard J, Massoudi M, Langer J. Improved real‐world glycaemic outcomes with liraglutide versus other incretin‐based therapies in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16(9):819‐826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saunders WB, Nguyen H, Kalsekar I. Real‐world glycaemic outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating exenatide once weekly and liraglutide once daily: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2016;9:217‐223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Unni S, Wittbrodt E, Ma J, et al. Comparative effectiveness of once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists with regard to 6‐month glycaemic control and weight outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(2):468‐473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Frías JP, Guja C, Hardy E, et al. Exenatide once weekly plus dapagliflozin once daily versus exenatide or dapagliflozin alone in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin monotherapy (DURATION‐8): a 28 week, multicentre, double‐blind, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(12):1004‐1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ludvik B, Frías JP, Tinahones FJ, et al. Dulaglutide as add‐on therapy to SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with inadequately controlled type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐10): a 24‐week, randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(5):370‐381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thong KY, Gupta PS, Cull ML, et al. GLP‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes NICE guidelines versus clinical practice. Br J Diabetes Vasc Dis. 2014;14:52‐59. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Database has been backed‐up and securely stored for accessibility and review if applicable.