Abstract

Introduction

Growing recognition of the deleterious effects of racism on health has led to calls for increased education on racism for health care professionals. As part of a larger curriculum on health equity and social justice, we developed a new educational session on racism for first-year medical students consisting of a lecture followed by a case-based small-group discussion.

Methods

Over the academic years of 2016–2017, 2017–2018, and 2018–2019, a total of 536 first-year medical students participated in this mandatory session. The course materials were developed as a collaboration between faculty and students. The lecture was delivered in a large-group format; the small-group case-based discussion consisted of 10–12 students with one upper-level student facilitator.

Results

The majority of respondents for the course evaluation felt that the course had met its stated objectives, and many commented that they had an increased awareness of the role of racism in shaping health. Students felt that the small-group activity was especially powerful for learning about racism.

Discussion

Active student involvement in curriculum development and small-group facilitation was critical for successful buy-in from students. Additional content on bias, stereotyping, and health care disparities will be the focus of faculty development programs and will also be integrated into the clerkships to build on these important topics as students are immersed in clinical care.

Keywords: Social Determinants of Health, Racism, Bias, African American, Health Care Disparities, American Indian/Alaska Native

Educational Objectives

By the end of this activity, learners will be able to:

-

1.

Define race and racism.

-

2.

Describe historical examples of institutional racism in science and medicine.

-

3.

Differentiate the levels of racism and how they can affect health.

-

4.

Utilize tools to address and cope with racial bias in the health care setting.

Introduction

Recent events in the United States have brought to light the continued struggles the nation faces with respect to racial bias and racism. It is increasingly clear that experienced racism has a profoundly deleterious effect on the health of minority populations—at both individual and institutional levels. Minority populations are exposed to greater amounts of stress and adverse social determinants that can lead to higher risk for poor mental and physical health.1–8 In the US health system, minority patients are less likely to receive high-quality health care services across multiple clinical settings,9 driven in large part by implicit bias on the part of physicians.10,11 Throughout medical training, students and trainees are exposed to multiple methods of instruction that enhance bias and misconceptions about race, genetics, culture, and disparities.12–16 In this context, teaching medical professionals about structural racism and how to recognize and address bias in clinical encounters has become increasingly imperative.11,17–20

Physicians, public health advocates, and medical educators have long recognized the impact that bias has on the well-being and care of patients. In acknowledging this, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education's Accreditation Standard 7.6: Cultural Competence and Health Care Disparities requires that “the faculty of a medical school ensure that the medical curriculum provides opportunities for medical students to learn to recognize and appropriately address gender and cultural biases in themselves, in others, and in the health care delivery process.”21

Likewise, medical students are increasingly requesting a focus on health equity and racism in medical education,22 including at our institution. In 2014–2015, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (NJMS) students, in response to multiple killings of unarmed black men by the police, staged a die-in as part of the White Coats 4 Black Lives movement and advocated for increased teaching on issues of racism and its effect on health in the traditional NJMS curriculum.

In response, as a part of major curriculum revision, in academic year 2016–2017 (AY17), we created a new required course, Health Equity and Social Justice (HESJ), designed to be longitudinal over the preclerkship years, with the goal of making health equity content in the curriculum more accessible and explicit. The course included sessions on power and privilege in the physician-patient relationship, the role of unconscious bias in health care, trauma-informed care, spirituality, the social determinants of health, working with underserved populations, and exploring the patient's perspective, among others.

We offered the 3-hour, mandatory HESJ session on racism and health to all first-year medical students within the first month of the curriculum over AY17, 2017–2018 (AY18), and 2018–2019 (AY19). The session consisted of a didactic lecture and a small-group case-based discussion. Prior to the session, all students had attended an interactive lecture on unconscious bias, completed an Implicit Association Test (IAT),23 and submitted a personal reflection essay on the results of the IAT as part of HESJ.

Prior work with educational modules on racism for medical students,24,25 psychiatry residents,26 third-year clerkship students,27 and physicians28,29 has shown an increase in awareness of the importance of racism and bias, as well as an enhancement of a commitment to health equity. These interventions used one of multiple different modalities, including didactic lectures, small-group case-based discussions, online tutorials, and IATs. We found four such publications in MedEdPORTAL,25–27,29 one of which was designed for preclinical medical students25 but none of which included both didactic lecture and small-group case-based discussions.

Unlike other MedEdPORTAL publications, we incorporated both large-group didactic and case-based small-group activities to increase awareness of how racial historical insults shape society and consciousness, as well as to guide students in absorbing and processing the new information through debate and reflection. We engaged students in the curriculum design, a technique that has been successful in other efforts addressing cultural competency training.30 In addition, because we based the cases on student experiences, the discussions provided students opportunities to brainstorm about skills that they could use to navigate bias when they experience or witness it in the clinical setting.

We chose to expose students to these topics very early in their clinical training (the first month of the first year) to set the stage for subsequent clinical experiences and for future health equity curricular elements. The topics included the power and privilege dynamic in the clinical encounter, cultural humility, social determinants of health, working with underserved populations, and adverse childhood experiences/trauma-informed care—all areas where race and racism play important roles influencing health and access to high-quality health care.

Methods

Recommended Background Resources

To prepare for the session, we recommended that students read one article and view one video. Katherine Brooks’ perspective piece “A Silent Curriculum”31 reflects on her medical school experience and provides first-year students with an introduction to the role bias plays in health care disparities. Dorothy Roberts, in her TEDMED talk “The Problem With Race-Based Medicine,”13 explores the history of race-based medicine, its continued influence on physicians’ decisions and health disparities, and the importance of recognizing race as a social concept.

Didactic Lecture

The lecture, detailed in the lecture slides (Appendix A), required the use of a large lecture hall with a computer and projector with PowerPoint. We allotted 50 minutes for the lecture and provided a detailed materials checklist and time line (Appendix B). We chose to include a didactic component to introduce students to concepts and historical perspectives, including the history of the establishment of our institution and its impact on race relations in Newark, NJ,32,33 that have shaped the face of modern racial bias. We referred to the revised Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training20 in the early planning stages of creating learning objectives.

The lecture explored the changing definitions of race over time, differentiated the levels of racism, provided examples of how health can be affected by each level, and explored ways to address racial bias in health care. We used Camara P. Jones’ work on race and the levels of racism34,35 as a key resource for development of the lecture materials. We drew from prior work in MedEdPORTAL to describe the historical context influencing racial/ethnic health care disparities.29 We provided more in-depth examples of the interaction between historical and present-day racism and health for American Indian/Alaska Native36,37 and African American/black populations.7,32,38,39 The addition of a 2018 study discussing the spillover effects of police killings on black Americans was included in AY19.7

We also incorporated into the lecture approaches to addressing bias in clinical encounters. We had found in the first 2 years that frameworks and suggestions were needed to enhance the discussion and to give students practical and portable tools that could help them address bias and microaggressions when encountered in clinical work. In AY19, we incorporated two portable mnemonic frameworks to address both personal unconscious bias and external microaggressions.

We developed the CHARGE2 framework, which described efforts health care workers could make to mitigate the effects of their own unconscious bias. The framework is as follows:

-

•

C—Change your context: Is there another perspective that is possible?

-

•

H—Be Honest: With yourself, acknowledge and be aware.

-

•

A—Avoid blaming yourself: Know that you can do something about it.

-

•

R—Realize when you need to slow down.

-

•

G—Get to know people you perceive as different from you.

-

•

E—Engage: Remember why you are doing this.

-

•

E—Empower patients and peers.

The framework summarized key points from a previous HESJ lecture on unconscious bias by author James Hill, a trained clinical neuropsychologist and the associate dean of student affairs at our institution. The framework drew on several resources in developing steps to mitigate implicit bias.11,40,41 CHARGE2 was first piloted in this session in AY19 and was not modified over time.

We adapted the INTERRUPT framework with permission to provide students with a tool kit of responses with specific language to address bias and microaggressions. We hypothesized that this framework would be especially useful for students who might find it difficult to speak up due to power dynamics within teams in academic medicine. It was first piloted in this form in the AY19 session. However, we had piloted excerpts from the Interrupting Microaggressions42 framework during an orientation for clerkship students 3 months earlier. Preliminary feedback from the orientation session showed that the students appreciated having tangible tools for addressing bias on their clinical rotations.43

The INTERRUPT framework is as follows:

-

•

I—Inquire: Leverage curiosity. “I'm curious, what makes you think/say that?”

-

•

N—Nonthreatening: Convey the message with respect. Separate the person from the action or behavior. “Some may consider that statement to be offensive.” Communicate preferences rather than demands. “It would be helpful to me if….”

-

•

T—Take responsibility: If you need to reconsider a statement/action, acknowledge and apologize. Address microaggressions, and revisit them if they were initially unaddressed.

-

•

E—Empower: Ask questions that will make a difference. “What could you/we do differently?”

-

•

R—Reframe: “Have you ever thought about it like this?”

-

•

R—Redirect: helpful when individuals are put on the spot to speak for their identity group. “Let's shift the conversation….”

-

•

U—Use impact questions: “What would happen if you considered the impact on … ?”

-

•

P—Paraphrase: making what is invisible (unconscious bias) visible. “It sounds like you think….”

-

•

T—Teach by using “I” phrases: Speak from your own experience. “I felt x when y happened, and it impacted me because….”

Small-Group Case Discussions

A group of upper-level students collected the case studies for the small-group session. The students who contributed cases were recruited by a senior student (author Megana Dwarakanath) who had expressed interest in health equity topics to the course director and collated the cases for the course director to review. The cases were based on clinical experiences that led a student to struggle with concepts of race or racism. Because the case studies were gleaned from actual student experiences, they were designed to challenge students to look more closely at their own assumptions about the proximity of race and racism impacting their training and patient care. We also hoped that speaking openly about examples of racism would empower students to share their own experiences of noting racial bias in patient-physician encounters.

We created a working group of four students and the course director to develop prompting questions and learning points for each case. We recommend using the case development worksheet (Appendix C) as a guideline to effectively develop cases. We developed this worksheet based on our own experience in collecting cases, analyzing themes, and deciding on relevant learning points. Five cases with different themes were ultimately chosen. The facilitator guide and the worksheet were the result of brainstorming sessions and discussions among the students based on their experiences and insights, rather than being based on a literature review. The lecture notes detailed in the facilitator guide (Appendix D) were added in AY19 and were largely based on student peer facilitator feedback from the prior 2 years. The course director further refined the prompting questions and facilitator notes informed by narrative medicine and perspectives from the medical literature.14,44–51

We chose to have student peers, rather than faculty, facilitate the discussion to create a safe space for students to debate openly without fear of being assessed and without worry of trying to come to a consensus that would be acceptable to an authority figure. We also felt that student facilitators could more proximally give advice to students about how to navigate the medical hierarchy. These ideas emerged as a result of reflection and feedback from the student volunteers who assisted with curricular development for the HESJ course and the session on racism in particular.

The student peer facilitators were recruited through personal invitation from the core student working group as well as through class-wide emails requesting volunteers. The facilitators were second-, third-, and fourth-year students. Prior to the session, the peers attended a 60-minute evening training where the course director reviewed the facilitator guide and discussed the cases and prompting questions with the group. This training was attended by approximately 50% of the peer facilitators each of the 3 years. We did not collect data on the demographics of the peer facilitators.

Each small group consisted of 10–12 students paired with one peer facilitator; the small groups met after the lecture, with a 10-minute break between the lecture and the small groups. The materials needed for the small-group discussion included rooms with a table and chairs, one printout of the facilitator guide, and printouts of the student pages (Appendix E), one for each student (10–12 per group). The facilitators handed out student pages at the beginning of the session. First, the groups reviewed the ground rules; then, they discussed each of the cases using the prompting questions. We allotted 120 minutes for discussion of the cases and prompting questions; most groups finished the discussion of all five cases within 90–100 minutes. We indicated no prespecified break; however, students were allowed to leave the room for short breaks as needed.

The facilitator guide also included notes for each case detailing specific concepts and language that could be used to address biases and microaggressions, as well as a description of practical tools and takeaway messages that could assist students in navigating difficult scenarios they might encounter. Highlighted skills included reflection using the CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT frameworks, as well as advice on where to seek support and guidance. Appendix B provides a materials checklist and time line for the small groups.

Assessment

Assessment of the session initially consisted of multiple-choice questions testing content from the lecture incorporated into unit exams in the systems-based curriculum in AY17. However, students in both the course evaluation and focus groups felt that this approach was stress provoking and took away from broader, deeper themes that could not be assessed with multiple-choice questions. Based on student feedback, starting in AY18, we administered the questions instead as an online, open-content quiz (Appendix F) testing content of the lecture and the small group. The course director developed the quiz questions—four multiple-choice questions based on the lecture content and one short-answer question based on the small-group content (“What top two messages did you take from the case discussions during the small-group session on racial bias medicine and why?”). Over time, we further developed the multiple-choice questions to more closely match the course objectives.

The course director graded the quizzes and incorporated the score into the overall grade for the HESJ course. The short-answer responses were graded based on demonstrating the following: (1) understanding of the content, (2) thoughtfulness and self-reflection in the responses, and (3) evidence of having engaged with the topics of discussion and resources. Students were provided with these criteria in advance in the course syllabus and during the course introduction.

Evaluation

We provided an HESJ course online anonymous evaluation form to all students at the end of the first 2 academic years through an internal educational management system. Students were asked to reflect back on all of the sessions in the course and report on how well each session met its learning objectives. They were also asked to provide any comments about how the sessions and overall course could be improved. In those first 2 years, the evaluations were submitted approximately 9–10 months after the session and also asked students to reflect on multiple other educational sessions in the HESJ course, limiting the number of questions that could be asked about each individual educational component. We found that response rates were low (less than 50%).

In AY19, we expanded the evaluation to include more detailed questions as well as free-text responses about strengths and improvements. The students submitted the evaluations online using Qualtrics as a survey platform. We asked the students to submit responses within 1 week after the session. The AY19 evaluation form is included in Appendix G.

Annual end-of-course focus groups were conducted for AY17 and AY18 to ensure ongoing student involvement in any course improvements and changes. We recruited eight first-year participants in AY17 and seven in AY18 via a class-wide email invitation and then by interested students who recruited additional participants. These self-selected students demonstrated an interest in health equity topics and provided predominantly positive feedback about the session. They reported that the presence of peer facilitators enhanced their comfort level during the discussion. In AY17, they also suggested a change to the online open-content quiz format and overwhelmingly supported incorporating questions into the unit examinations, particularly since they speculated that a short-answer component could stimulate self-reflection and a deeper understanding of the content.

Data Analysis

We were granted institutional review board approval for the analysis of evaluation and quiz data. We extracted the anonymous evaluation data for each year from the online surveys. For the strengths and improvements session on the AY19 evaluation, we categorized, coded, and quantified the themes. For the short-answer quiz question from AY18 and AY19, we downloaded the responses from our online educational platform, permanently removed student identifiers (names), and then categorized, coded, and quantified the themes expressed for each response. On average, each individual student response contained 2.9 and 3.1 themes in AY18 and AY19, respectively. Two of the authors (Michelle DallaPiazza and Mercedes Padilla-Register) independently analyzed the text evaluation and quiz comments and responses and then highlighted and discussed any differences to come to a consensus. Disagreement in the coding of the responses occurred less than 5% of the time.

Results

Student Demographics

In the 3 years that we offered this mandatory session on racism and health, a total of 536 students participated. The demographics of each class by gender, race, and ethnicity are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Percentage of Student Participants Who Self-Identified by Demographic Factors Based on Gender and Race/Ethnicity by Academic Year.

| Demographic | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (n = 178) | 2018 (n = 179) | 2019 (n = 179) | |

| Woman | 49 | 51 | 50 |

| Man | 51 | 49 | 50 |

| Asian | 42 | 36 | 39 |

| Black or African American | 14 | 11 | 7 |

| White | 38 | 39 | 44 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 9 | 13 | 15 |

| No race/ethnicity reported | 6 | 14 | 10 |

Analysis of Student Evaluations

At the end of HESJ AY17 and AY18, 55 (30%) and 76 (41%) students, respectively, completed the course evaluation form. Overall, for AY17 and AY18 combined, 95 (72%) felt that the learning objectives for the session had been met to a considerable or a very high degree. Thirty-two (25%) felt that the learning objectives had been met to a small or moderate degree, and four (3%) felt that the learning objectives had hardly been met at all.

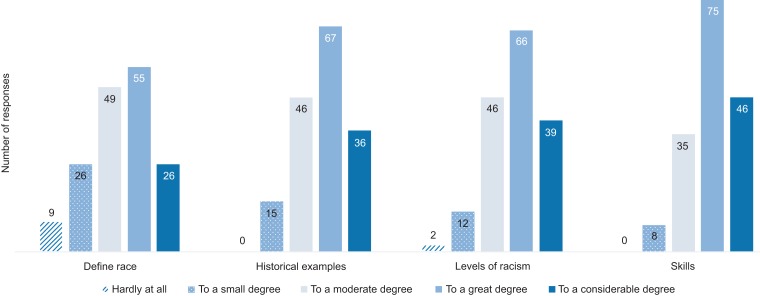

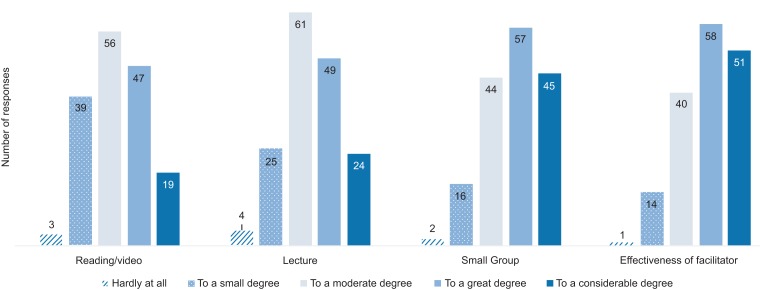

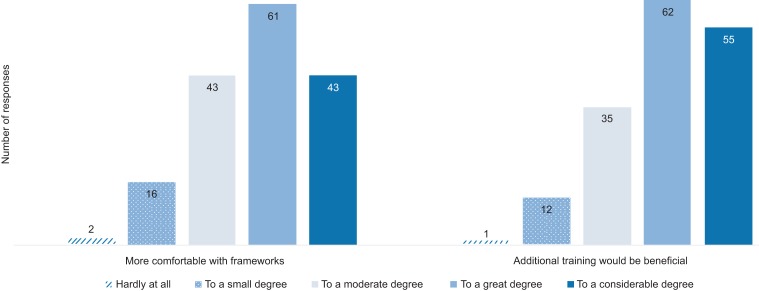

In AY19, 165 (92%) students completed a more detailed session-specific evaluation form. The responses focusing on the learning objectives are summarized in Figure 1. The students largely felt that their knowledge and skills improved with respect to the learning objectives; however, the learning objective that needed additional exploration compared to the others was defining race and racism. The students reported that each of the components of the activity also contributed to their learning to high degrees (Figure 2), with the group discussion and small-group facilitator effectiveness rated most favorably. Lastly, 63% agreed to a great or considerable degree and 26% to a moderate degree that they felt more comfortable using CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT, and 71% agreed to a great or considerable degree and 21% to a moderate degree that additional training on this topic would be beneficial to their learning to become doctors (Figure 3).

Figure 1. For the academic year 2018–2019 student evaluation, the number of responses indicating the degree to which students’ knowledge and/or skills improved with respect to the defined learning objectives (n = 165). Responses left blank are not included in the total numbers.

Figure 2. For the academic year 2018–2019 student evaluation, the number of responses indicating the degree to which the individual components of the activity contributed to a change in attitudes or perspectives related to racism and its role in medicine (n = 165). Responses left blank are not included in the total numbers.

Figure 3. For the academic year 2018–2019 student evaluation, the number of responses to the items “After this activity, I feel more comfortable addressing instances of bias in clinical care through the CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT frameworks” and “Additional training on this topic will be beneficial for my learning to become a doctor” (n = 165).

Regarding the strengths and improvements section of the AY19 evaluation (summarized in Table 2), positive comments about the session focused on several themes, mainly on increased awareness and an appreciation for interactive and collaborative learning in the small-group discussion session. In the first 2 years, critical feedback mainly centered on the fact that HESJ sessions in general distracted the students from other obligations and pressures. With the more detailed AY19 evaluation, however, we obtained richer feedback. These comments dealt mostly with making the lecture more high yield and interactive and with spending more time exploring the medical hierarchy, with actionable points on how to address bias from the perspective of a medical student with seemingly little power in the team dynamic.

Table 2. Strengths and Suggested Improvements Themes With 10 or More Mentions on the Academic Year 2018–2019 Student Evaluation (n = 165).

| Theme | Na | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | ||

| Recommended prereading/video and lecture | ||

| Concrete and historical examples in lecture helpful/interactive lecture | 25 | “[The lecture] gave concrete, historical examples, especially relevant to US history/our culture here, and today.” |

| Small group | ||

| Discussion interactive/connecting with and learning from classmates/hearing multiple viewpoints | 63 | “The small-group discussion was the highlight. It allowed us to share our different perspectives and achieve a level of understanding on how to approach an unjust situation due to bias or race.” |

| Real-life/stimulating scenarios that challenged assumptions and comfort levels | 31 | “Using real life scenarios to gauge our understanding of the topic and discussing them in an open forum.” |

| Provided safe space/helpful having guidance of upperclassman as facilitator | 23 | “The [student] facilitator that led my small group was incredibly active in stirring up conversation, and made many clinical correlations to his own experiences. His leadership helped [us] speak up more, and made me feel safe.” |

| Overall | ||

| Increased awareness of topics/encouraged self-reflection/important topic | 43 | “The concept … addresses a very crucial issue in healthcare. All physicians will encounter situations in which bias and racism will potentially affect judgment and emotions.” |

| CHARGE2 and/or INTERRUPT frameworks helpful | 25 | “The small-group discussion … allowed us to feel empowered to try to make as many changes as we can with CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT while we are students.” |

| Strengthened lessons on unconscious bias/Implicit Association Test/made difficult concepts more concrete | 11 | “This activity put into words and pictures what I could previously only vaguely sense myself. I am so appreciative of the lessons taught through this module.” |

| Improvements | ||

| Lecture | ||

| More time in small groups/less in lecture | 18 | “The lecture was long and cut into the time meant for small-group discussion, which I found to be the most valuable part.” |

| More time in lecture to explore concepts in depth/make lecture more interactive | 15 | “I think that Tuskegee trial should be talked about in much more depth … especially as students may wish to pursue clinical research.” |

| Small group | ||

| More cases/more diverse or realistic cases/less obvious “right” answer | 15 | “The small-group cases could have been a little more provocative—I felt like some of them were too blatantly wrong … and it would be better for students to be exposed to the less obvious instances.” |

| More actionable points/more on navigating medical hierarchy | 13 | “Without good examples of how these problems are being addressed and how the attitudes are changing in healthcare, it will feel like a hopeless task.” |

N indicates the number of responses fitting a theme.

Analysis of Quiz Responses

For AY18 and AY19, all students (n = 358) completed the quiz. The average grade for the quiz was 95% in both years. We summarize the results of the analysis of the short-answer question in Table 3. For both years, the frequencies of themes were similar. The most frequent learning topics focused on increased awareness about internal bias, the importance of addressing bias, and the impact that bias has on patient care and health systems. In addition, students noted that the culture of medicine and the medical hierarchy in medicine can create challenges to addressing bias in ways they had not previously considered.

Table 3. Themes Represented in Student Responses to the Short-Answer Question “What Top Two Messages Did You Take From the Case Discussions During the Small-Group Session on Racial Bias Medicine and Why?” for Academic Years 2017–2018 (n = 179) and 2018–2019 (n = 179).

| Theme | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | |

| Racism/bias | ||

| Everyone has bias/important to recognize own biases and slow down thinking. | 76 (42) | 64 (35) |

| Important to challenge assumptions/biases in others in a professional manner. | 85 (47) | 42 (23) |

| Unconscious bias has a significant impact on patients/can affect many levels of health care. | 46 (26) | 40 (22) |

| Conversations uncomfortable but essential/helpful to discuss scenarios prior to immersion in clinical care/important to be prepared for microaggressions. | 38 (21) | 33 (18) |

| Racism is common/more pervasive than I realized in medicine. | 25 (14) | 33 (18) |

| Bias can also emerge in other contexts (gender, socioeconomic), not just race/ethnicity. | 12 (7) | 14 (8) |

| Case-specific | ||

| The hierarchy of medicine can make it difficult to act or change culture. | 41 (23) | 43 (24) |

| High-pressure situations/culture of medicine/institutional factors can lead to unconscious bias influencing treatment decisions. | 39 (22) | 34 (19) |

| Patient bias against providers can affect the quality of care/challenging to address without alienating patient. | 29 (16) | 39 (22) |

| Racism can cause power shifts within teams of health care workers. | 13 (7) | 6 (3) |

| Powerful that scenarios were based on real experiences of students. | 9 (5) | 9 (5) |

| “Othering” and “us vs. them” attitudes can be detrimental to patient care. | 9 (5) | 4 (2) |

| Patient-related | ||

| Important to engage with patients to understand their experience with discrimination in health care/enhance trust/empower patients. | 31 (17) | 18 (10) |

| Health care is a right, not a privilege/race is a social construction that unfairly disadvantages patients. | 10 (6) | 5 (3) |

| Student-related | ||

| Many helpful resources for students (Student Affairs, clerkship director). | 22 (12) | 17 (9) |

| Students have power to effect change. | 12 (7) | 21 (12) |

| Many different approaches based on diversity of experiences/learn from each other. | 17 (9) | 18 (10) |

| Frameworks/tools | ||

| INTERRUPT/elements of tool helpful for tactfully addressing bias. | N/A | 69 (38) |

| CHARGE2/elements of framework helpful for addressing our own biases. | N/A | 38 (21) |

The CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT frameworks were explicitly highlighted in the lecture and small groups in AY19 only; the quiz responses for AY19 frequently emphasized the usefulness of the frameworks for addressing both internal and external bias (21% and 38% of responses, respectively). Overall, in addition to highlighting key learning points, the responses often demonstrated the students’ capacity for introspection and empathy for patients and peers.

Discussion

Racism, because of its impact on health and health care, should be explored by all medical students as part of their educational journey to become a physician. Our effort, detailed here, was successful at meeting its goals of exploring the levels of racism, reviewing the implications of historical racism, facilitating reflection and dialogue, and introducing skills that can be developed to work against bias.

Unlike other approaches, we chose to include a didactic lecture prior to engaging in a small-group discussion in order to demonstrate that the legacy of racism influences the unconscious bias in everyone. The knowledge that racial bias affects many aspects of health and permeates the physician-patient relationship proved to be eye-opening for many students and was important for framing the small-group discussions that followed. In future years, based on student feedback, we will add more emphasis on defining key terms, such as race and racism, and on exploring the team dynamics of the medical hierarchy in more depth.

The lecture, while important, is one reason why we dedicated 3 hours to this learning session. Since the group discussion provided the most robust learning experience, for others hoping to implement a similar session in less time, we recommend either assigning the lecture slides in advance or selecting key slides to reduce the lecture time to 15–20 minutes. As an example, the lecture focuses in depth on historical instances and on describing and providing evidence for institutional racism; these concepts could be significantly abbreviated to concentrate more on differentiating the levels of racism and on the tools that can be used to combat racism in clinical practice. The case discussions could also be abbreviated by limiting them to two or three high-yield cases based on institutional needs.

In the small groups, the first-year students highlighted the opportunity to engage in a discussion incorporating multiple perspectives and viewpoints of their peers as a major strength of our approach. They were also able to identify several barriers and strategies to overcoming these barriers through use of the CHARGE2 and INTERRUPT frameworks. The incorporation of these elements in the most recent iteration of the session (AY19) helped the students to apply concrete steps for self-reflection and action to address bias. In both the evaluation and, especially, the quiz responses, these frameworks emerged as important tools that helped to frame the discussion and generate actionable points.

Upper-level students proved to be an invaluable resource in the development and implementation of the curriculum and, in particular, in the inclusion of potentially highly charged topics such as racism and bias in medicine. By leveraging the expertise of student advocates to design small-group case-based discussions based on real experiences, we aimed to create a safe learning environment that provided a basis for personal growth through reflection. In addition, because the upper-level students’ experiences were more proximal and relatable, students valued their reflections and sharing of lessons learned. Student participants, the student peers who led the conversations, and the focus groups of first-year students affirmed that the facilitators were successful at engaging students and, because faculty were not present, created a safe space for students to share a broad range of opinions and reflections.

An important limitation to this approach is that we excluded from the case discussions a significant contribution to the learning environment—faculty. Faculty need to be part of the dialogue around racism and bias in medicine18; they are the mentors and role models from whom students learn clinical behaviors. Faculty require training and exposure to comfortably and meaningfully engage students on these topics. To address this need, we have met with each faculty course director in the preclerkship curriculum to discuss strategies to avoid inclusion of potentially biased information in educational content and to enrich activities with health equity topics. We have also developed a core group of faculty facilitators from multiple specialties in a learning community (LC) for the preclerkship curriculum. We train LC facilitators in delivering the HESJ small-group content and encourage them to attend the lectures even if they are not involved in facilitation of the corresponding small group. We are also currently implementing faculty enrichment programs on unconscious bias and racism beyond the LC.

An additional limitation to our approach is that both the lecture and the small-group discussion focused mainly on American Indian/Alaska Native and African American/black health disparities, while only touching briefly on Asian American or Latino(a) American experiences with racism and discrimination. Especially in light of the overall demographics of our student body, this limitation may be significant, since we miss out on an opportunity to glean insight from a wider section of the class. Future work could include more information on the effect of experienced racial and ethnic discrimination on health for other minority groups. A recent meta-analysis showed that while racism was associated with poorer health for all groups, the association between racism and negative mental and physical health was significantly stronger for Asian American (for mental health only) and Latino(a) American (for both) when compared to African American/black participants.2

We felt it was important to incorporate assessment into the HESJ course at large, so we included quiz questions in the course design. When converting to an online, open-content format, we found that the grade averages were very high—95%. However, we were able to glean important information about learning topics from the small-group sessions and introduce another layer of content review to cement learning of the concepts. Future work could focus on assigning HESJ content more value in the overall medical education curriculum,18,19,52 which could be facilitated by advocacy to include social medicine topics in the USMLE examinations.

As highlighted by student feedback, it is critical to ensure that we revisit HESJ content later in training, particularly at the time when students are immersed in clinical care and exposed to the reality of health disparities. Because the data we present here are based on student perceptions, we cannot be sure how this training will later translate into behaviors or how durable the knowledge and skills will be. We will aim future work at developing longitudinal HESJ content spread throughout the clerkship year. In AY18, we piloted interactive sessions at the beginning, middle, and end of the clerkship year on bias and stereotyping in clinical care and evidence-based approaches to address health care disparities.43 New objectives and questions focused on bias have been added to each clerkship evaluation, and currently underway is curriculum development driven by the clerkship directors in each specialty that touches on at least one HESJ topic, such as social determinants of health, health care disparities, and trauma-informed care.

We specifically designed the materials in this session for first-year medical students. However, because of the generalizability of the content, the session can be adapted to other groups and settings, including other health professional students, residents, and faculty, as an introduction to racism and health. We anticipate that the skills concerning personal reflection and nonthreatening approaches to addressing bias will prove useful in the clinical care of patients and in supporting colleagues. As health care shifts to place greater emphasis on population health and community engagement, curricula such as this, which stimulate greater awareness and advocacy among future physicians, are a critical first step in promoting health and wellness for all communities, including those most vulnerable to bias and discrimination.

Appendices

A. Lecture Slides.pptx

B. Materials Checklist and Time Line.docx

C. Case Development Worksheet.docx

D. Facilitator Guide.docx

E. Student Pages.docx

F. Quiz.docx

G. Evaluation Form.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the student champions who inspired this work.

Disclosures

None to report.

Funding/Support

Dr. Soto-Greene reports grants from the Health Resources Services Administration-Hispanic Center of Excellence awarded to Rutgers New Jersey Medical School during the conduct of the study.

Informed Consent

All identifiable persons in this resource have granted their permission.

Ethical Approval

The Newark Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved this study.

References

- Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35(4):407–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolezsar CM, McGrath JJ, Herzig AJM, Miller SB. Perceived discrimination and hypertension: a comprehensive systematic review. Health Psychol. 2014;33(1):20–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siordia C, Covington-Ward YD. Association between perceived ethnic discrimination and health: evidence from the National Latino & Asian American Study (NLAAS). J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(2):111–117. https://doi.org/10.14283/jfa.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter-Acey JC, Sealy-Jefferson S, Helmkamp L, et al. Racism in the form of micro aggressions and the risk of preterm birth among black women. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(1):7–13.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales KL, Lambert WE, Fu R, Jacob M, Harding AK. Perceived racial discrimination in health care, completion of standard diabetes services, and diabetes control among a sample of American Indian women. Diabetes Educ. 2014;40(6):747–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714551422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bor J, Venkataramani AS, Williams DR, Tsai AC. Police killings and their spillover effects on the mental health of black Americans: a population-based, quasi-experimental study. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):302–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31130-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C-S, Ayala G, Paul JP, Boylan R, Gregorich SE, Choi K-H. Stress and coping with racism and their role in sexual risk for HIV among African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Latino men who have sex with men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(2):411–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0331-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green AR, Carney DR, Pallin DJ, et al. Implicit bias among physicians and its prediction of thrombolysis decisions for black and white patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1231–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staats C, Dandar V, St.Cloud T, Wright RA. Proceedings of the Diversity and Inclusion Innovation Forum: Unconscious Bias in Academic Medicine—How the Prejudices We Don't Know We Have Affect Medical Education, Medical Careers, and Patient Health. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yudell M, Roberts D, DeSalle R, Tishkoff S. Taking race out of human genetics. Science. 2016;351(6273):564–565. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D. The problem with race-based medicine [video]. TED website. https://www.ted.com/talks/dorothy_roberts_the_problem_with_race_based_medicine Published November 2015. Accessed March 23, 2018.

- Tsai J, Ucik L, Baldwin N, Hasslinger C, George P. Race matters? Examining and rethinking race portrayal in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):916–920. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun L. Theorizing race and racism: preliminary reflections on the medical curriculum. Am J Law Med. 2017;43(2-3):239–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098858817723662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun L, Saunders B. Avoiding racial essentialism in medical science curricula. AMA J Ethics. 2017;19(6):518–527. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.6.peer1-1706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karani R, Varpio L, May W, et al. Racism and bias in health professions education: how educators, faculty developers, and researchers can make a difference. Acad Med. 2017;92(11S):S1–S6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285–288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhaus M, Finnegan A, Haidar M, Kleinman A, Mukherjee J, Farmer P. The necessity of social medicine in medical education. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):565–568. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie DA, Boker J, Crandall S, et al. Revising the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training (TACCT) for curriculum evaluation: findings derived from seven US schools and expert consensus. Med Educ Online. 2008;13(1):4480 https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v13i.4480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaison Committee on Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School: Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Washington, DC: Liaison Committee on Medical Education; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Charles D, Himmelstein K, Keenan W, Barcelo N. White Coats for Black Lives: medical students responding to racism and police brutality. J Urban Health. 2015;92(6):1007–1010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-015-9993-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Implicit Association Test. Project Implicit website. https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/

- van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: a Medical Student CHANGES study report. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1748–1756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGannes C, Woodson Coke K, Bender Henderson T, Sanders-Phillips K. A small-group reflection exercise for increasing the awareness of cultural stereotypes: a facilitator's guide. MedEdPORTAL. 2009;5:668 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.668 [Google Scholar]

- Medlock M, Weissman A, Wong SS, et al. Racism as a unique social determinant of mental health: development of a didactic curriculum for psychiatry residents. MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10618 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks KC, Rougas S, George P. When race matters on the wards: talking about racial health disparities and racism in the clinical setting. MedEdPORTAL. 2016;12:10523 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SC, Prasad S, Hackman HW. Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(5):915–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Schaik E, Howson A, Sabin J. Healthcare disparities. MedEdPORTAL. 2014;10:9675 https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.9675 [Google Scholar]

- Shields HM, Nambudiri VE, Leffler DA, et al. Using medical students to enhance curricular integration of cross-cultural content. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25(9):493–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70556-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks KC. A silent curriculum. JAMA. 2015;313(19):1909–1910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.1676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibaldo-Bongiorno M, Bongiorno J. Revolution ’67 [DVD]. Newark, NJ: Bongiorno Productions; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- From rebellion to empowerment: the 50th anniversary of the Newark medical school fight. Newark Public Library website. https://npl.org/from-rebellion-to-empowerment-the-50th-anniversary-of-the-newark-medical-school-fight/ Published 2018.

- Jones CP. Systems of power, axes of inequity: parallels, intersections, braiding the strands. Med Care. 2014;52(10)(suppl 3):S71–S75. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener's tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–1215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Cullen T, Bernard K, Shaykevich S, Orav EJ, Ayanian JZ. Trends in quality of care and barriers to improvement in the Indian Health Service. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(5):480–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1594-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sequist TD, Cullen T, Acton KJ. Indian Health Service innovations have helped reduce health disparities affecting American Indian and Alaska Native people. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(10):1965–1973. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, St George DMM. Distrust, race, and research. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(21):2458–2463. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.162.21.2458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WhiteCoats4BlackLives website. http://www.whitecoats4blacklives.org/

- Banaji MR, Greenwald AG. Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People. New York, NY: Delacorte Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kahneman D. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar Straus & Giroux; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kenney G. Interrupting microaggressions. College of the Holy Cross website. https://www.holycross.edu/sites/default/files/files/centerforteaching/interrupting_microaggressions_january2014.pdf Published 2014. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- Ayyala M, DallaPiazza M, Soto-Greene M. A novel longitudinal curriculum exploring stereotype and bias in the third year clerkships. Poster presented at: Academic Internal Medicine Week; March 18–21, 2018; San Antonio, TX.

- Ansell DA, McDonald EK. Bias, black lives, and academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1087–1089. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett MT. #BlackLivesMatter—a challenge to the medical and public health communities. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12)1085–1087. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1500529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calman NS. Out of the shadow. Health Aff (Millwood). 2000;19(1):170–174. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.19.1.170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria S, Johnson EN, Hayashi JL, Christmas C. Graduate medical education in the Freddie Gray era. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):1998–2000. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1509216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano MJ. White privilege in a white coat: how racism shaped my medical education. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):261–263. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensah MO. Making all lives matter in medicine from the inside out. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1413–1414. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucey CR, Navarro R, King TE., Jr Lessons from an educational never event. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1415–1416. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrus KD. Medical education and the minority tax. JAMA. 2017;317(18):1833–1834. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.0196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper J, Greene JA, Farmer PE, Jones DS. All health is global health, all medicine is social medicine: integrating the social sciences into the preclinical curriculum. Acad Med. 2016;91(5):628–632. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

A. Lecture Slides.pptx

B. Materials Checklist and Time Line.docx

C. Case Development Worksheet.docx

D. Facilitator Guide.docx

E. Student Pages.docx

F. Quiz.docx

G. Evaluation Form.docx

All appendices are peer reviewed as integral parts of the Original Publication.