Abstract

Background

Domestic violence (DV) is a global public problem that touches all levels of society and socio-economic status. Identifying women's attitudes towards domestic violence is an important first step in the prevention and control of its consequence. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed: (i) to synthesize women's reasons for justifying domestic violence and (ii) to determine the pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence in Ethiopia.

Methods

Pub-Med and google scholar data bases searched for quantitative cross-sectional studies. The study quality was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment tool. Heterogeneity test and evidence of publication bias were assessed. Pooled prevalence of women's attitude was calculated with 95%CI using random effects model.

Results

A total of 15 articles were included in the study. The pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards justifying domestic violence was found to be 57% (95% CI; 47.0%-67.2%). Reasons for justifying were: burning food, argues with husband, goes out without telling, neglects children, refuses sex, unfaithful, disobeys and suspects infidelity.

Conclusion

More than half of women accept domestic violence. Authors' suggest strengthening of women's awareness toward norms that justify wife beating.

Keywords: Attitude, domestic violence, Ethiopia

Background

Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG) is one of the most common public problem affecting the individual, family, and community regardless of their age, race, nationality, and socio-economic status1,2. Apart from the violations of human rights, domestic violence (DV) damages the physical, psychological, sexual, reproductive health and social well-being of the community as a whole1–3. According to World Health Organization (WHO) survey, at least one in three women had experienced either physical or sexual violence by intimate partners4. Of this, 37% was reported from Africa5,6. In Ethiopia, it reached up to 76.5% for lifetime and 72.5% for the past 12 months7–11. Ethiopian women are most likely justify DV for men to use against women1,2,10. Despite this high burden of the problem, beliefs toward the acceptance of violence are common and wide12,13. Studies revealed that women's attitude towards and the cultural grants of men's authority to control female behavior are the strongest predictor of domestic violence13.

Cultural and social norms that encourage violence are rules or expectations of behavior within society to maintain individuals' preference to follow if they violate it14–17. Despite the governmental efforts toward the prevention and control of domestic violence, still globally 2 to 91%2,7,18–22 of women and girls had a positive attitude towards domestic violence and in Ethiopia, this figure ranged from 5 to 91%1,3,10,22–35. Poverty, rural residence, gender inequality in schooling and decision making, ethnicity, religion, and exposure to the media were associated with women's attitudes toward domestic violence1,7–14. Pre-occupation with the psychology of violence and the focus on cultural orientations obscure the more salient features of social life that promote violence1,12,13. Women's attitude towards domestic violence has negative consequences on their life such as re-victimization, help seeking behavior, and on the effectiveness of Governmental and non-governmental efforts to control domestic violence1,12–16. In Ethiopia, there is a belief that women are docile, submissive, patient, and tolerant of monotonous work and violence, for which culture is used as a justification1,3,18,19. In other words, there is bias in gender roles that can be seen during child rearing as boys are expected to learn and become responsible in different activities, while girls are expected to be well-trained and specialize in indoor activities like cooking food, fetching water and caring for children and aged families2,7,18,19 as a consequence, these led women to justify men to use violence against them, and they are least likely to think that women have the right to say no to any violence activities. Studying the epidemiological evidence of women's attitude toward domestic violence and reasons for justification, gives vital information for policy makers' to designing effective programs and address the issu1. Acceptance of women's attitude toward domestic violence is an indicator of the status of women in a specific social and cultural setting, this provide insights into the countries' stage of social, cultural and behavioral transformation in the evolution towards gender democratic society1,3,23–25.

The results of previous studies revealed different proportion of women's attitude towards domestic violence1,3,10,22–35. This variation of individual studies showed the need of more conclusive evidence such as systematic review and meta-analysis to take corrective action and to the best of authors' knowledge, there is no systematic review and meta-analysis that summarizes the current evidence of women's attitude towards domestic violence in Ethiopia. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed: (i) to synthesize reason for justifying domestic violence and (ii) to determine the pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence among women in Ethiopia.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA)36. The PRISMA Check list was attached as supporting file 1.

Data sources and search strategies

The search and document retrieval strategy was intended to capture a range of published and unpublished literature. Pub-Med electronic databases were mainly searched until November, 7, 2017 using the search term: ((gender based violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (gender based violence) OR (domestic violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (domestic violence) OR (intimate partner violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (intimate partner violence) OR (spouses violence[ MeSH Terms]) OR (spouses violence) OR (physical abuse[MeSH Terms]) OR (physical abuse) OR (physical violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (physical violence) OR (emotions violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (emotions violence) OR (emotions abuse[MeSH Terms]) OR (emotions abuse) OR (psychological violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (psychological violence) OR (psychological abuse[MeSH Terms]) OR (psychological abuse) OR (sex violence[MeSH Terms]) OR (sex violence) OR (sex abuse[MeSH Terms]) OR (sex abuse) OR (harassment[MeSH Terms]) OR (harassment) OR (intimidation[MeSH Terms]) OR (intimidation) OR (sexual assault[MeSH Terms]) OR (sexual assault) OR (sexual coercion[MeSH Terms]) OR (sexual coercion) OR (rape[MeSH Terms]) OR rape)) AND ((women's attitude [MeSH Terms]) OR (women's attitude) OR (women's perception [MeSH Terms]) OR (women's belief [MeSH Term]) OR (women's belief) OR (women's ideology [MESH Term]) OR (women's ideology) OR (coping mechanism[MeSH Terms]) OR (coping mechanism) OR (defense mechanism[MeSH Terms]) OR (defense mechanism) OR (woman's response[MeSH Terms]) OR (woman's response) AND ((Barriers[MeSH Terms]) OR (Barriers) OR (reasons[MeSH Terms]) OR (reasons) OR (associated factors[MeSH Terms]) OR (associated factors) OR (determinants factors[MeSH Terms]) OR (determinants factors)) AND Ethiopia. There was no restriction of language and publication year. The reference lists of included studies were also manually searched. In addition databases such as Google and Google Scholar, were searched for gray literature and published in an unindexed journals publishing papers relevant to this review. Following these strategies, we imported all the records into EndNote X7 reference management software and used automated “Find Duplicates” function to exclude any duplicates.

Measurement tool and definition of the variables

In this systematic review and meta-analysis domestic violence was defined as any violence whether physical, psychological and sexual or any combination of the three, regardless of the legal status of the relationship. Physical violence was defined as one or more intentional acts of physical aggression such as pushing, slapping, throwing, hair pulling, punching, hitting, kicking or burning, perpetrated with the potential to cause harm, injury or death. Psychological/emotional violence was defined as one or more acts, or threats of acts, such as shouting, controlling, intimidating, humiliating and threatening the victim. Sexual violence is defined as the use of force, coercion or psychological intimidation to force the woman to engage in a sex act against her will, whether or not it is completed1. For the purposes of this systematic review and meta-analysis, the dependent variable, women's attitude towards wife beating, was measured by using either the WHO multi country assessment tool with six items such as: in your opinion, does a man have enough reason to mistreat or beat his wife if: (1) she does not complete her household work to his satisfaction?, (2) she disobeys him?, (3) she refuses to have sexual relations with him?, (4) she asks him whether he has other girlfriends?, (5) he suspects that she is unfaithful? and (6) he finds out that she has been unfaithful? (1). Or by the contextualized EDHS with five items such as: Women were asked whether a husband is justified in beating his wife in various circumstances: if (1) the wife burns the food, (2) argues with him, (3) goes out without telling him, (4) neglects the children and (5) refuses sexual intercourse with him23–25. There are also studies assessed by single item. The responses for all the items were categorized as “Yes/No” or agreed/disagreed. “Yes” and “Agreed” were coded as “1” and “No” and “Disagreed” were coded as “0”. Favorable attitude or women's acceptance of domestic violence or woman justifies wife beating was defined if the participant's response include at least one of the “Yes” or “Agreed” response for one or more of the items.

Study selection and eligibility criteria

For the current review, we identified articles pertaining to women's attitude towards domestic violence. Articles were included if (i) carried out in Ethiopia (ii) all form of violence having the results of women's attitude towards domestic violence, (iii) quantitative design and (iv) for study used both sex, sample for which results of women were presented separately. Articles that do not meet the eligibility criteria were excluded.

Data extraction

A standardized, pre-piloted form was used to extract the required information. Each of the included studies were coded using the pre-piloted form. The extracted data included details of author's name, year of publication, sample size, setting (community or institution based) and reported prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence. The eligibility of included studies were assessed and extracted independently by two investigators (YDG and BBB). Disagreements were solved by discussion.

Quality assessment

Two review authors independently assessed the quality of included studies using Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment tool adapted for cross-sectional studies37. The Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment tool adapted for cross-sectional studies in three sections (selection of participants, comparability and assessment of outcome). The quality of each paper was assessed with items including: sample size was representative, sample size was justifiable, the response rate is satisfactory, the measurement tool was valid, groups are comparable, the outcome assessed independently and blindly and the appropriateness of the statistical test. The results of each individual paper was grade with score ranged between 0 (minimum) and 9 (maximum) score. Then the overall quality of each paper was determined using the sum of the overall scores of assigned stars. In our study, we assigned one star for each of the following part of the selection criteria such as: representativeness (random sampling), sample size was calculated, reported response rate and ascertainment of the exposure with validated tool. For the comparability criteria, we assigned stars according to the depth of articles with statistical adjustment for the independent variables and assigned one star for age, sex, and race only and two stars for additional factors like reasons and for the outcome criteria, we assigned one star for self-reported outcomes and two stars for those studies that assessed the outcome and reasons with clearly descriptive statistics. The quality of the studies was defined as follows: good for ≥ 5, satisfactory for 3–4 and unsatisfactory for <3. This quality appraisal score was assessed by two investigators (YDG and BBB) and disagreements were solved by discussion.

Data synthesis

The Pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence was calculated with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using random-effects38. Test for Heterogeneity between the studies was performed with Cochran's Q statistic and the I2 statistics. I2 value greater than 50% was considered as indicative of substantial heterogeneity, 39. Sensitivity analysis was also performed. For analysis, primarily the coded studies were entered into a Microsoft Excel Database and then imported into Stata14 with packages of Meta-analysis for statistical analyses. For the summarizations of reasons we utilized tables.

Results

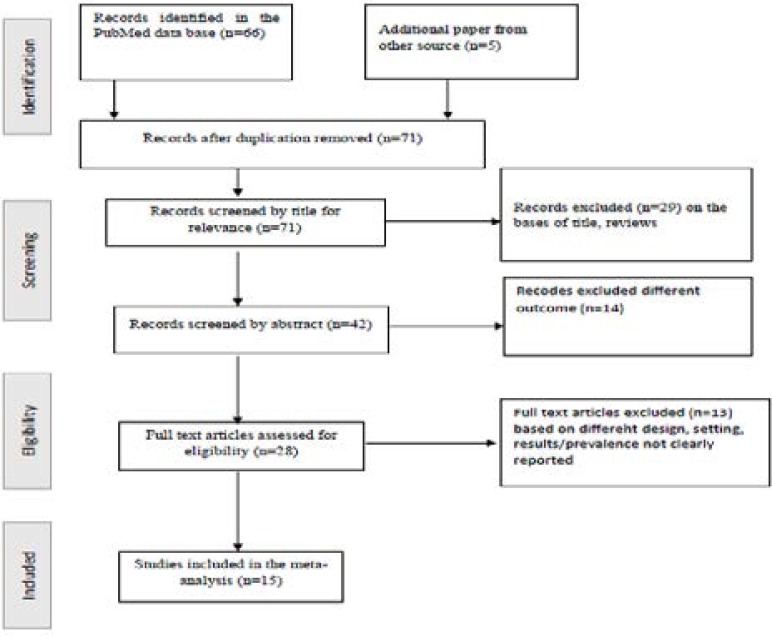

The literature search resulted in 71 recorded papers. Of these record, 56 were excluded and the remaining 15 studies included in the present systematic review and meta-analysis (Figure: 1).

Figure: 1.

Flow diagram of studies included in meta-analysis

Study characteristics

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, all of the included studies utilized cross-sectional study design with sample size ranging from 221 to 16515. Of the 15 included studies, majority (n=13) were community based studies. WHO multi-country and EDHS assessment tool were utilized for the assessments of majority of the outcome variables (Table: 1).

Table: 1.

Characteristics of the studies and prevalence of non-disclosure (n=15)

| Author Year |

Setting | Measurements | Number of participants |

Number of participants accept DV |

Prevalence of Accept DV (%) |

| EDHS,2011 | Community | Five items EDHS | 16515 | 11296 | 68 |

| EDHS,2005 | Community | Five items EDHS | 14070 | 11397 | 81 |

| EDHS,2000 | Community | Five items EDHS | 15367 | 12985 | 84.5 |

| Agumasie,2013 | Community | Five items EDHS | 682 | 36 | 5 |

| Berhane, 2017 | Institution | WHO-6-Items | 422 | 102 | 24 |

| Negussie, 2010 | Community | WHO-6-Items | 1994 | 1694 | 85 |

| Assefa, 2008 | Community | One-item | 440 | 111 | 25 |

| Ellsberg, 2005 | Community | WHO-6-Items | 3016 | 2748 | 91 |

| Ruman, 2013 | Community | 5-Item from EDHS & WHO |

360 | 200 | 56 |

| Bedilu, 2016 | Community | One-item | 282 | 32 | 11 |

| Mulunesh , 2015 | Community | Not clear | 365 | 257 | 70 |

| Tsegahun,2008 | Community | WHO-6-Items | 713 | 471 | 66 |

| Haji, 2004 | Community | WHO-6-Items | 396 | 260 | 66 |

| Yegomawork, 2004 |

Community | WHO-6-Items | 2261 | 1651 | 73 |

| Bereket, 2016 | Institution | Not clear | 221 | 108 | 48 |

Quality of the study

The overall quality score of included studies ranged from 3 to 7. Of these, majority 11(73%) had good quality and the remaining four studies had fair quality (Supporting file 2).

Supporting file 2.

Quality assessment score of the studies included in the analysis (n=15)

| Author, year |

Quality domain | Total | ||||||

| Selection (Max score=5) |

Comparability (Max=2) |

Outcome (Max=3) |

||||||

| 1) Representative ness of the sample: a) Truly representative of the average in the target population* (all subjects or random sampling) b) Somewhat representative of the average in the target population* (non-random sampling) c) Selected group of users. d) No description of the sampling strategy. |

2) Sample size: a) Justified and satisfactory* b) Not justified. |

3) Non-respondents: a) Comparability between respondents and non-respondents characteristics is established, and the response rate is satisfactory* b) The response rate is unsatisfactory, or the comparability between respondents and non-respondents is unsatisfactory. c) No description of the response rate or the characteristics of the responders and the nonresponders. |

4) Ascertainment of the exposure (risk factor): a) Validated tool. ** b) Non-validated measurement tool, but the tool is available or described.* c) No description of measurement tool. |

1) The subjects in different outcome groups are comparable, based on the study design or analysis. Confounding factors are controlled. a) The study controls for the most important factor (select one)* b) The study control for any additional factor* c) no control |

1) Assessment of outcome a) Independent blind assessment ** b) Record linkage** c) Self report * d) No description. |

2) Statistical test: a) is clearly described, appropriate, and measurement of association is presented, including confidence intervals & probability level (p value)* b) is not appropriate |

||

| EDHS, 2011 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | b (+1) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 7 |

| EDHS, 2005 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | b (+1) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 7 |

| EDHS, 2000 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | b (+1) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 7 |

| Agumasie, 20 13 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Berhane, 2017 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Negussie, 2010 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 7 |

| Assefa, 2008 | b (+1) | b(+1) | c(+0) | c(+0) | c(+0) | c (+1) | b(+0) | 3 |

| Ellsberg, 2005 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Ruman, 2013 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Bedilu, 2016 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | c(+0) | c (+1) | b(+0) | 4 |

| Mulunesh , 2015 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | c(+0) | c (+1) | b(+0) | 4 |

| Tsegahun, 20 08 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Haji, 2004 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 6 |

| Yegomawor k, 2004 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c (+1) | a(+1) | 7 |

| Bereket, 2016 | b (+1) | b(+1) | a (+1) | c(+0) | c(+0) | c (+1) | b(+0) | 4 |

The results of each individual paper score ranged from 4 to 8. Of the included 15 articles, six of them scored 8, five of them scored 7 and the remaining four of the articles scored 4 (Table: 2). All studies were good in quality

Table: 2.

Women's reasons for justifying domestic violence

| Author, year | Percentage of women who agree that a man has good reason to beat his wife if: | ||||||||||

| Burn food |

Argues with husband |

Goes without telling |

Neglect children |

Refuse sex |

Wife is unfaithful |

Wife does not complete housework |

Wife disobeys her husband |

Husband suspects infidelity |

Wife asks about other women |

dominance | |

| EDHS, 2011 | 47.3% | 45.4% | 43.2% | 57.8% | 38.6% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EDHS, 2005 | 61% | 58.7% | 64.2% | 64.6% | 44.3% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| EDHS, 2000 | 64.5% | 61.3% | 56.2% | 64.5% | 50.9% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Agumasie, 201 3 | 38% | 49.4% | 67.3% | 50.3% | 38.9% | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Berhane, 2017 | - | - | - | - | 80.4% | 72.6% | 89.2% | 93.1% | - | 70% | - |

| Negussie, 2010 | - | - | - | - | 60% | - | - | - | - | - | 97.4% |

| Ellsberg, 2005 | - | - | - | - | 45.6% | 79.5% | 65.8% | 77.7% | 43.8% | 32.2 | - |

| Ruman, 2013 | - | 11.2% | 11.8% | - | 9.2% | 52% | 17.1% | - | - | - | - |

| Tsegahun, 2008 | - | - | - | - | 19.8% | 49.6% | 22.7% | 40.1% | 21.9% | 20.2% | - |

| Haji, 2004 | - | - | - | - | 66.9% | 64.4% | 66.9% | 71.7% | 64.4% | 60.1% | - |

| Yegomawork, 2004 | - | - | - | - | 50% | - | 69% | 80% | 82% | 45% | - |

Reasons for justifying domestic violence

Several reasons were identified for women's and girls' acceptance of domestic violence. The most common reasons identified from the included studies were: burning food1,23–26, argues with husband1,23–26,29, goes without telling their husband1,23–26,29, neglect children1,23–26, refuse sex1,23–26,29,31,33,34, unfaithful1,29,31–33, wife does not complete housework1,29,31,33,34, wife disobeys her husband1,31,33,34, husband suspects infidelity1,32–34 and if wife asks her husband about other women33,34. Moreover, there was a study that revealed the presence of women who considered beating as a normal and sign of love27 and those women who recognize beating to be a symbol of love would even try to trigger it (Table: 3).

Prevalence of women's attitude towards justifying domestic violence

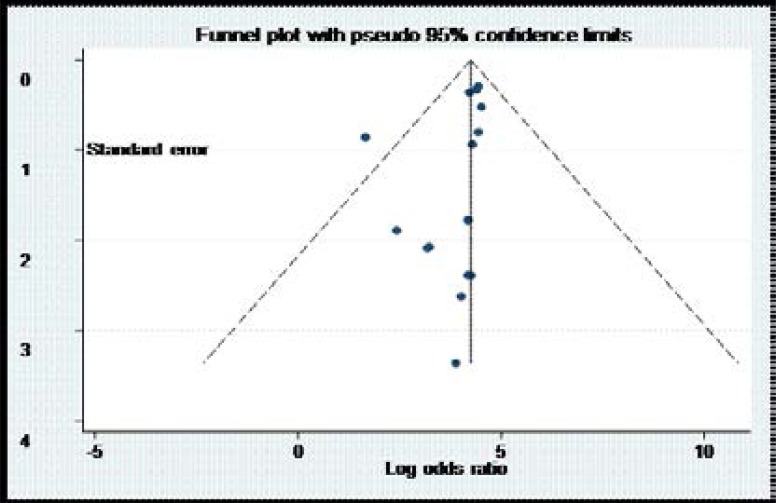

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence was found to be 57% (95% CI; 47.0%-67.2%) (Figure 2). We found significant heterogeneity (Q=11899.0, p ≤ 0.001 and I2=99.9%), but no evidence of publication bias (Egger's test, p=0.132) and funnel plots (Figure: 3). Sensitivity analysis produced a pooled estimates ranging from 54.6% (95%CI 43.8–65.5%) to 61.0 (95% 54.1–67.8%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of studies assessing the prevalence of women's attitude toward domestic violence in Ethiopia using random effect models (Pooled prevalence, with 95% CI)

Figure: 3.

Funnel plot of studies assessing the prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence in Ethiopia using random effect models (Pooled prevalence, with 95% CI)

Discussion

Although there are studies on women's attitude and reasons towards domestic violence in Ethiopia, to the authors' knowledge there is no systematic review and meta-analysis carried out in Ethiopia to help the decision makers by providing concrete evidence for the prevention and control of violence. Thus, the purpose of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to synthesis women's reasons for accepting domestic violence and determine the pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence in Ethiopia.

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of women's attitude towards domestic violence was found to be 57% (95% CI; 47.0%–67.2%). Even though, there are no similar studies, this finding is consistent with systematic review and meta-analysis carried out among 25 sub-Saharan African Countries40 and among 39 low and middle income countries16. From this systematic review and meta-analysis, it is observed that despite the evidence of a cultural shift in orientations towards violence, the problem of violence against women persists across a range of different societies as the pooled prevalence revealed more than half of women accept the belief that wife beating is justified. This implies (i) though the government works on women and girls empowerment, the result of this study revealed the need to work more on women's attitude towards domestic violence (ii) the influence of cultural beliefs associated with accepting wife beating such as women’ belief in men's dominance that favored acceptance of violence. There may be different reasons for these: first, the culture/norms of the community still influence women's and girls' attitude as indicated in this systematic review and meta-analysis, the considerations of violence as a normal and sign of love27. Evidence revealed that cultural and social norms encourage violence because they are rules or expectations of behavior within society to maintain individuals' preference to follow if they violate it1,13–17. The socialization process, which determines gender roles, is partly responsible for the subjugation of women in Ethiopia1,3,18,19. In countries like Ethiopia, where there is bias in gender roles, women are least likely to think as having the right to say no to any violent activities.

Regarding women's reasons for the acceptance of wife beating, the results of reported studies identified different reasons with different proportion1,23–27,29,31–34. The most common reasons in this systematic review were: burn food1,23–26, argues with husband1,23–26,29, goes without telling their husband1,23–26,29, neglect children1,23–26, refuse sex1,23–26,29,31,33,34, unfaithful1,29,31–33, wife does not complete housework1,29,31,33,34, wife disobeys her husband1,31,33,34, husband suspects infidelity1,32–34, if wife asks her husband about other women33,34 and considered beating as a normal and sign of love27. This is similar with the findings of systematic reviews carried out in Africa13,41,42. Different systematic reviews from Africa have been reported different reason with different percentage for women who justified wife-beating in at least one of the circumstances13,22,41,42. These may be due to the deep rooted, shared cultural belief on gender role. Cultural and social norms are highly influential in shaping individual behavior, including the use of violence1,13,22. For instance, evidence from a systematic review of African DHS data revealed compared to those participants who agreed with at least one of the six justifications item toward wife beating were 14.6% more likely abused than those participants who disagreed with wife beating41. This pre-occupation with such cultural orientations make incomprehensible the more salient features of social life that promote violence1,13,22–25,40.

The strengths of this systematic review and meta-analysis were: we attempted to include studies carried out at different settings (school, college/university and community), the first systematic review and meta-analysis of women and girls attitude towards domestic violence and the enrolment of all studies without the limitations of study time and language restriction. However, this systematic review and meta-analysis had some important limitations. First, although the focus of this review was on the attitude and reasons towards domestic violence, the exclusion of qualitative studies may not represent the true attitudes. Second, use of different measurement tools to assess attitude may affect getting the different diminutions of attitude. Third, although we used reference lists and Google Scholar to include all the available studies, there may be the possibility of having some overlooked papers. Fourth, even though contextual understanding of the country is recommended for intervention and Ethiopia is a multicultural society, the limitations of the scope in Ethiopia may not be generalizable for other countries. Despite these limitations, this systematic review and meta-analysis is the first attempt to summarize the women's and girls' attitudes towards domestic violence and revealed the existing evidence. Thus, this finding is pivotal in informing the stakeholder for the development of strategies in the prevention and control of the problems.

Conclusion

More than half of women and girls accept domestic violence. The most common identified reasons for the acceptance of domestic violence were: burning food, argues with husband, goes without telling, neglects children, refuses sex, unfaithful, does not complete housework, disobeys husband, suspects infidelity, if wife asks her husband about other women and considering of wife beating as sign of love. Thus, authors' suggest the need for (i) interventions to modify cultural and social norms that supportive the persistence of DV struggles for their right need improvement, (ii) the strengthening of women's awareness particularly on addressing norms that justify wife beating and male control of women's behavior (iii) government is also suggested to strengthen women and girls empowerment (iv) future research, authors suggest the need of systematic review and meta-analysis with different study designs to provide comprehensive evidence.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material included in this systematic review and meta-analysis was the PRISM CHECK LIST utilized for the systematic review and meta-analysis (supporting file 1) and the quality of included studies (supporting file 2).

Authors Contributions

YDG participated in the conception of manuscript, search, analysis and interpretation of data. BBB participated in search, reviewing, data analysis, commented and drafted the manuscript. Thus, both authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agreed to be accountable for their individual contributions.

Competing interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Ellsberg M, Garcia-Moreno C, Heise L, Jansen H, Watts C. WHO Multi-country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence against Women. 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO, author. Understanding and addressing violence against women intimate partner violence. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Central Statistical Agency & ICF International, author. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, MD, USA: Central Statistical Agency & ICF International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nations. U, author. Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women combined sixth and seventh periodic reports of States parties Ethiopia. 2010. pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization, author. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Central Statistical Agency and Rockville M, USA. CSA and ICF, author. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey: Key Indicators Report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ethiopia. UW, author. Shelters for women and girls who are survivors of violence in Ethiopia National Assessment on the Availability, Accessibility, Quality and Demand for Rehabilitative and Reintegration Services. Addis Ababa: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gossaye Y DN, Berhane Y, Ellsberg M, Emmelin M, Ashenafi M, Alem A NA, et al. Butajira rural health program: womens' life events study in rural Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2003;17(2) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tenaw Yimer TG, Gudina Egata, Mellie H. Magnitude of Domestic Violence and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women in Hulet Ejju Enessie District, North-West Ethiopia. Advances in Public Health. 2014:8. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedilu Abebe Abate, Wossen BA, Degfie TT. Determinants of intimate partner violence during pregnancy among married women in Abay Chomen district, Western Ethiopia: a community based cross sectional study. BMC Women's Health. 2016;16(16) doi: 10.1186/s12905-016-0294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mesfin Araya. Gender based violence and its consequences in Ethiopia: a Systematic Review. Ethiop Med J. 2017;55(3):501–508. 1–8 (7) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yount Kathryn M, Halim Nafisa, Hynes Michelle, Hillman Emily R. Response effects to attitudinal questions about domestic violence against women: A comparative perspective. Social Science Research. 2011;40:873–884. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heise LL. Determinants of partner violence in low and middle-income countries : Exploring variation in individual and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai AC, Kakuhikire B, Perkins JM, Vořechovska D, McDonough AQ, Ogburn EL, et al. Measuring personal beliefs and perceived norms about intimate partner violence: Population-based survey experiment in rural Uganda. PLoS Med. 2017;14(5):e1002303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tillman Shaquita, Bryant-Davis Thema, Smith Kimberly, Marks Alison. Shattering Silence: Exploring Barriers to Disclosure for African American Sexual Assault Survivors. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2010;11(59) doi: 10.1177/1524838010363717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran TD, Nguyen H, Fisher J. Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence against Women among Women and Men in 39 Low- and Middle-IncomeCountries. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):1–14. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167438. PubMed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards KM. Intimate parnter violence and the rural-urbansuburban divide myth or reality? A critical review of the literature. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2014;16(3) doi: 10.1177/1524838014557289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurmu Eshetu, Endale Senait. Wife beating refusal among women of reproductive age in urban and rural Ethiopia. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2017;17(6) doi: 10.1186/s12914-017-0115-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yigzaw Tegbar, Berhane Yemane, Deyessa Nigussie, Kaba Mirgissa. Perceptions and attitude towards violence against women by their spouses: A qualitative study in Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010:1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vyas S, Mbwambo J. Physical partner violence, women's economic status and help-seeking behaviour in Dar es Salaam and Mbeya, Tanzania, Global Health Action. Global Health Action. 2017;10(1) doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1290426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hindin MJ. Understanding women's attitudes towards wife beating in Zimbabwe. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81(7):501–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uthman Olalekan A, Lawoko Stephen, Moradi Tahereh. Sex disparities in attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women in sub-Saharan Africa: a socio-ecological analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(223):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro, author. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2000. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro, author. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Central Statistical Agency & ICF International, author. Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, MD, USA: Central Statistical Agency & ICF International; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Semahegn Agumasie, Belachew Tefera, Abdulahi Misra. Domestic violence and its predictors among married women in reproductive age in Fagitalekoma Woreda, Awi zone, Amhara regional state, North Western Ethiopia. Reproductive Health. 2013;10(63):1–9V. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-63. 2013 10(63) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hailemariam A, Tizita Tilahun. Correlates of Domestic Violence against women in Bahr Dar, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deyessa Negussie, Berhane Yemane, Ellsberg Mary, Emmelin Maria, Kullgren Gunnar, Högberg Ulf. Violence against women in relation to literacy and area of residence in Ethiopia. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdurashid Ruman. The Prevalence of Domestic Violence in Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care at the Selected Health Facilities in Addis Ababa. Addis Ababa University School of Social Work Addis Ababa University; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abebe Mulunesh, Asres Kerebih. Intimate Partner Violence against Women: Practice and Attitude in South Wollo and East Gojjam Zones of Amhara National Regional State. The Ethiopian Journal of Social Sciences. 2015;1(1):15–39. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gebrezgi Berhane Hailu, Badi Marta Berta, Cherkose Endashaw Admassu, Weldehaweria Negassie Berhe. Factors associated with intimate partner physical violence among women attending antenatal care in Shire Endaselassie town, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional Study. Reproductive Health. 2017;14(76):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12978-017-0337-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tessema Tsegahun. The Status of Gender Based Violence and Related Services in Four Woredas (Woredas surrounding Bahir Dar town, Burayu woreda, Bako woreda and Gulele Sub-city of Addis Ababa) Ethiopia: CARE; 2008. Feb, pp. 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kedir Haji. Magnitude and immidiate outcome of physical partner violence against women in Kolfe District Zone, Oromia Region. 2004. pp. 1–88. PubMed Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gossaye Yegomawork, Deyessa Negussie, Berhane Yemane, Ellsberg Mary, Emmeli3 Maria, Ashenafi Meaza, Alem Atalay, Negash Alemayehu, Kebede Derege, Kullgren Gunnar, Hogberg Ulf. Butajira Rural Health Program: Women's Health and Life Events Study in Rural Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2004;17(5):1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zewude Bereket Tessema, Ashine Kidus Meskele. Student Attitude towards on Sexual Harassment: The Case of Wolaita Sodo University, Ethiopia. Journal of Education and Practice. 2016;7(34):76–80. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols. 2015;4(1) doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale adapted for cross-sectional studies. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berkey CS, Hoaglin DC, Mosteller F, Colditz GA. A random-effects regression model for meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine. 1995;14(4):395–411. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine Statistics in medicine. 2002;21(11) doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hindin Michelle j. Adolescent Childbearing and Women's Attitudes towards Wife Beating in 25 Sub Saharan African Countries. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:1488–1495. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Heise Lori L, Kotsadam Andreas. Cross-national and multilevel correlates of partner violence: an analysis of data from population-based surveys. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e332–e340. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rani Manju, Bonu Sekhar, Diop-Sidibé Nafissatou. An Empirical Investigation of Attitudes towards Wife-Beating among Men and Women in Seven Sub-Saharan African Countries. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2004 Dec;8(3):116–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]