Abstract

Objective

Central nervous system (CNS) features in children with permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM) due to KCNJ11 mutations have a major impact on affected families. Sulfonylurea therapy achieves outstanding metabolic control, but only partial improvement in CNS features. The effects of KCNJ11 mutations on the adult brain and their functional impact are not well described. We aimed to characterise the CNS features in adults with KCNJ11 PNDM, compared to adults with INS PNDM.

Research Design and Methods

Adults with PNDM due to KCNJ11 mutations (n=8) or INS mutations (n=4) underwent a neurological examination, and completed standardised neuropsychological tests/questionnaires about development/behavior. Four individuals in each group underwent a brain MRI scan. Test scores were converted to Z-scores using normative data, and outcomes compared between groups.

Results

In individuals with KCNJ11 mutations, neurological examination was abnormal in 7/8; predominant features were subtle deficits in coordination/motor sequencing. All had delayed developmental milestones and/or required learning support/special schooling. Half had features and/or a clinical diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. KCNJ11 mutations were also associated with impaired attention, working memory and perceptual reasoning, and reduced IQ (median IQ KCNJ11 vs INS mutations 76 vs 111, p=0.02). However, no structural brain abnormalities were noted on MRI. The severity of these features was related to the specific mutation and they were absent in individuals with INS mutations.

Conclusions

KCNJ11 PNDM is associated with specific CNS features which are not due to long-standing diabetes, persist into adulthood despite sulfonylurea therapy, and represent the major burden from KCNJ11 mutations.

Introduction

KCNJ11 gene mutations are the commonest cause of permanent neonatal diabetes (PNDM), which presents in the first 6 months of life and affects 1 in 100,000 live births (1). KCNJ11 is expressed in the pancreas and brain as well as other tissues, and encodes the Kir6.2 subunit of the ATP-dependent potassium (KATP) channel. In the pancreas, the KATP channel links increasing blood glucose to insulin secretion, but activating KCNJ11 mutations prevent channel closure in response to metabolically generated ATP and result in diabetes (2). Clinically, patients present in an insulin-deficient state and prior to discovery of disease-causing variants in the KCNJ11 gene they required insulin therapy. It was later shown that KCNJ11 PNDM could be treated with sulfonylurea tablets, which bind and close the channel allowing insulin secretion, excellent metabolic control and reduced glycaemic variability (3). For many patients and their families transferring from insulin to oral sulfonylureas vastly improved quality of life in relation to their diabetes (4).

Central nervous system (CNS) features occur in children with KCNJ11 PNDM in addition to diabetes. These are thought to result from expression of aberrant KATP channels in the brain. The precise role(s) of KATP channels in the human CNS has not been fully elucidated, but rodent studies suggest that they play a role in glucose sensing and homeostasis as well as seizure propagation (5; 6). KCNJ11 is expressed in many brain areas but there are particularly high levels of expression in the cerebellum (7; 8). The cerebellum is well known for its role in motor learning and coordination (9), but it also has functions relating to language, executive function and to mood; furthermore, cerebellar abnormalities have been linked with autism (10; 11). Documented CNS features in children with KCNJ11 mutations range from subtle neuropsychological impairments that specifically affect attention, praxis and executive function to the severe and overt DEND/intermediate DEND syndrome (developmental delay, epilepsy and neonatal diabetes) (12–15). Other associated features may include psychiatric morbidity, specifically neurodevelopmental disorders and anxiety disorders, visuomotor impairments, and sleep disturbance (16–18). The severity of the CNS phenotype is related to the genotype. For example, the V59M mutation is frequently associated with iDEND syndrome and neurodevelopmental features whereas the R201H mutation, previously associated with diabetes alone, has been more recently linked with subtle neuropsychological features (12). Historically, the severity of CNS features was thought to be related to the functional severity of the specific mutation in vitro, although functional interpretation also has to take into account the impact of the mutation on the open probability of the KATP channel which will depend on whether it affects channel gating or ATP binding (19–22).

Sulfonylurea treatment results in partial improvement in the CNS features (23–26), and resolution of functional cerebellar and temporal lobe abnormalities on single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scanning (24; 27). The improvement in CNS features may be limited as a result of poor penetration of the sulfonylurea across the blood brain barrier or active transport back out of the brain, leading to sub-therapeutic concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (28). This, and anecdotal clinical experience of greater CNS response with higher doses of sulfonylurea, has prompted clinical recommendations of glyburide doses of ~1mg/kg/day in people with severe neurological features secondary to KCNJ11 mutations (29). However, the neurobehavioral features continue to have a huge impact on families despite sulfonylurea treatment (16). This contrasts markedly with the outstanding metabolic response that changed lives by alleviating the anxiety associated with poor metabolic control (4). A key question is whether the CNS features continue to represent the major burden from KCNJ11 mutations in adult life. To date all studies characterising CNS features in KCNJ11 PNDM have been conducted in predominantly paediatric cohorts (12–14; 16; 23). However, brain development continues beyond childhood and adolescence (30; 31). No study has comprehensively assessed the CNS outcomes in adults with KCNJ11 mutations.

Mutations in the INS gene are a less common cause of neonatal diabetes, accounting for around 10% of cases (1). Heterozygous dominant negative INS mutations often affect protein synthesis resulting in production of structurally abnormal preproinsulin and proinsulin within the beta cell, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and cell death. Individuals with these mutations also typically present with insulin deficiency, but unlike KCNJ11 PNDM, require lifelong treatment with replacement doses of insulin (32). The INS gene is not expressed in any significant levels in the brain, therefore it is very unlikely that individuals with INS mutations would display a characteristic CNS phenotype as a direct result of their mutations (33). In fact, there have not been any reports of any such neurological issues, in contrast to those with KCNJ11 PNDM.

Individuals with PNDM may have long-term CNS sequelae secondary to diabetic ketoacidosis at diagnosis, as seen in Type 1 diabetes (34; 35). However, cerebral oedema in KCNJ11 PNDM gives rise to a pattern of neurological impairment distinct from that seen as a direct result of brain KATP channel dysfunction (36). More subtle neurocognitive problems also occur in the presence of diabetes per se, particularly if metabolic control is poor and diabetes is diagnosed before age 7 (37). Further, individuals with Type 2 diabetes are at increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease in later life, and this may be in part due to chronic metabolic disturbance and changes in insulin signalling (38). Indeed, there is evidence from both animal and human studies that insulin plays a key role in central processes including memory and learning (38). The non-specific diabetes-related cognitive features could confound assessment of CNS phenotype in people with KCNJ11 mutations, however people with INS mutations are well placed to control for them. There has been no previous detailed comparison of the CNS phenotype in people with INS and KCNJ11 mutations.

Aims

The aims of the study were to characterise the neurological and neuropsychological features in adults with KCNJ11 PNDM, and to compare these with adults with INS PNDM.

Methods

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Committee South West-Exeter.

Sample size and patient recruitment

We identified 34 patients >16 years old with KCNJ11 mutations and 9 patients >16 years old with INS mutations who had received a molecular genetic diagnosis in Exeter and who had been diagnosed with permanent neonatal diabetes under 6 months of age. We approached potential participants either directly at a neonatal diabetes family event in Exeter or via the Consultants in charge of their clinical care. We invited 17 individuals with KCNJ11 mutations to join the study; of these, 10 agreed to participate. However, 2 individuals were excluded from the analysis due to possible confounding factors: one individual (mutation L164P) was excluded because he was taking antipsychotic medication to treat a psychotic illness at the time of the study and had had a particularly severe initial presentation with diabetic ketoacidosis and 3 days in a coma, and a second individual (mutation V59M) was excluded due to severe neurological impairment following initial presentation with diabetic ketoacidosis (further clinical characteristics of excluded participants are available in online supplemental Table S1). We approached 9 individuals with INS mutations and 4 agreed to take part. All participants were from the UK apart from one who was from Canada.

Tests

All participants were visited at home or assessed in the Exeter Clinical Research Facility by the same Consultant neurologist and Consultant clinical neuropsychologist who carried out the history taking using a standard proforma, neurological examination, neuropsychological assessments, mood questionnaire and neurodevelopmental screen. If possible an informant or carer was also present to facilitate information gathering. The severity of intellectual impairment and behavioral disturbance in one individual (KCNJ11-8 [V59M]) meant that it was not possible for him to attempt any of the cognitive tests. Another individual (KCNJ11-6 [V252G]) did not wish to attempt the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) and was unable to understand instructions for the Colour Trails Test (CTT). In 8 participants (4 with KCNJ11 mutations and 4 with INS mutations), T2-weighted brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were performed using a 1.5T MRI scanner. The scans were reviewed and interpreted by a radiologist and a neurologist who were blinded to the mutation status of the individuals concerned.

Medical / developmental history, educational and professional attainment

Participants and informants were asked for a standard medical history, the ages at which major milestones were attained, whether learning support was required and level of education / employment.

Neurological Examination

A full neurological examination was performed. This included assessment of cranial nerves, limb tone, power, reflexes, coordination, sensation, and simple tests of motor sequencing and praxis, comprising 2 tests of bimanual coordination, one unilateral motor sequencing task (the Luria three hand position test), copying unfamiliar hand positions and manual miming, both tested in each hand.

Psychiatric and neurodevelopmental screen

Current psychological distress was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire. The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) was administered to screen for autistic traits.

Cognitive function

A battery of neuropsychological tests were administered to assess a variety of cognitive domains. The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) was used as a brief measure of current IQ. The Verbal Paired Associates and Visual Reproduction subtests of the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-IV) were used to give a verbal and non-verbal (visual) measure of memory. Subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, 4th edition (WAIS-IV) were administered: cancellation to assess processing speed and digit span (forwards and backwards) to assess working memory. Subtests of the Visual Object and Space Perception battery (VOSP) assessed visuospatial function; incomplete letters and object decision to test object perception, and dot counting and cube analysis to test spatial perception. The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) was used to assess aspects of executive function including verbal fluency, self-monitoring and ability to assimilate and adhere to stipulated rules. The Colour Trails Test (CTT) 1 and 2 were used as measures of sustained and divided attention, hand eye motor coordination and speed. Finally, the Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) was used as a broad screening measure of cognition, providing an assessment of the following cognitive domains; attention/orientation, memory, fluency, language, and visuospatial function.

Functional assessment

The Cambridge Behavioral Inventory Revised (CBI-R) questionnaire was used to complement the information obtained from the history taking. This measure seeks the opinion of the informant e.g. carer or family member on the frequency of a range of behaviors in the domains of memory and orientation, everyday skills, self-care, abnormal behavior (e.g. tactlessness, impulsiveness), mood, unusual beliefs, altered eating habits, disturbed sleep, stereotypic and motor behaviors, and altered motivation. For each behavior the informant assigned a score of 0-4 based on the frequency: scores of 3 (occurring daily) or 4 (occurring constantly) denote a significant behavioral deficit.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed using Excel 2010 and Stata 14. Qualitative data were presented descriptively. Where population normative data were available, neuropsychological test scores were converted to Z-scores. For VOSP subtests, a pass was a score ≥5th population percentile. To compare characteristics and outcomes between the KCNJ11 and INS groups, data were analysed using non-parametric methods (Mann-Whitney test for numerical variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables). Data are presented as median (range) unless otherwise stated.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics of the participants are outlined in Table 1; these were similar between individuals with KCNJ11 mutations and individuals with INS mutations.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics in individual participants KCNJ11 cases and INS controls and group characteristics summary.

| Case | Mutation | Inheritance | Sex | Age | Age at diabetes diagnosis (weeks) | Age at genetic diagnosis (years) | Age at transfer to SU (years) | Treatment (total daily dose) | HbA1c DCCT (%) | HbA1c IFCC (mmol/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KCNJ11 1 | G53S | Autosomal dominant | M | 32 | 2 | 23 | 23 | Glyburide 30mg, metformin 1g | 9.3 | 78 |

| KCNJ11 2 | R201H | Presumed de novo | F | 22 | 4 | 15 | 15 (attempted) | Insulin (restarted after trial of glyburide) | 8.1 | 65 |

| KCNJ11 3 | R201H | De novo | M | 36 | 10 | 29 | 29 | Gliclazide (120mg) | 8.1 | 65 |

| KCNJ11 4 | R201C | Presumed de novo | F | 36 | 5 | 27 | 34 | Glyburide (40mg) | 7.0 | 53 |

| KCNJ11 5 | R201C | De novo | M | 19 | 6 | 13 | 13 | Glyburide 27.5mg | 5.4 | 36 |

| KCNJ11 6 | V252G | De novo | M | 28 | 8 | 21 | 21 | Glyburide (85mg) | 10.8 | 95 |

| KCNJ11 7 | V59M | De novo | F | 25 | 15 | 17 | 17 | Glyburide (7.5mg) | 8.1 | 65 |

| KCNJ11 8 | V59M | De novo | M | 17 | 5 | 10 | 11 | Glyburide (55mg) | 5.9 | 41 |

| INS 1 | C43F | Autosomal dominant | F | 35 | 78 | 31 | N/A | Insulin | NK | NK |

| INS 2 | F48C | Presumed de novo | F | 50 | 5 | 42 | N/A | Insulin | NK | NK |

| INS 3 | G75C | De novo | M | 28 | 8 | 26 | N/A | Insulin | 7.9 | 63 |

| INS 4 | H29D | De novo | F | 20 | 26 | 12 | N/A | Insulin (pump) | 8.2 | 66 |

| KCNJ11 group | N/A | De novo = 7 (87.5%) Autosomal dominant = 1 (12.5%) | M = 5 (63%) F = 3 (37%) | 26.5 (17-36) | 5.5 (2-15) | 19 (10-29) | 21 (11-34) | Insulin treated = 1/8 | 8.1 (5.4-10.8) | 65 (36-95) |

| INS group | N/A | De novo = 3 (75%) Autosomal dominant = 1 (25%) | M = 1 (25%) F = 3 (75%) | 31.5 (20-50) | 17 (5-78) | 28.5 (12-42) | N/A | Insulin treated = 4/4 | 8.1 (7.9-8.2) | 65 (63-66) |

| P value | N/A | 1.0 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.15 | 0.23 | N/A | 0.01 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

Summary numerical data are presented as median (range) and categorical variables are presented as n (%). Mutations were presumed to have arisen de novo if there was no parental history of diabetes but the mutation status of the parents had not been confirmed with a genetic test. HbA1c values are the results available closest to the time of the neurobehavioral assessment. N/A = not applicable, NK = not known.

Neurological Features

Abnormalities on neurological examination were identified in 7/8 KCNJ11 participants and only one INS participant (Table 2).

Table 2. History and examination findings for individual KCNJ11 cases and INS controls.

| Case (mutation) | HISTORY | EXAMINATION / INVESTIGATIONS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developmental milestones / interventions | Seizures (cause, if known) | Educational attainment | Learning difficulties / support | Employment status (job) | Employment status (job) of parents / siblings | Psychiatric history | Neurological examination | Brain MRI | |

| KCNJ11 1 (G53S) | D (speech and motor) | No | MS then SS (age 11) | LS (repeated year 2) | E (supermarket) | F – E (council), S – E (chemicals factory) | Repetitive hand washing and rigid routines. | Impaired motor sequencing, fine finger movements, praxis. Subtle nystagmus, dysdiadokokinesis. | ND |

| KCNJ11 2 (R201H) | D (speech) | No | MS then U (nursing and childcare) | LS (English until age 15, Maths for 1 year) | US | F – E (accountant) M – E (nurse) | Nil | Intermittent mild head titubation. Brisk reflexes, questionable increase in tone in left arm. | N |

| KCNJ11 3 (R201H) | N | Yes – hypoglycaemia on insulin | MS then C (18 months, NVQs levels 1 &2) | LS (English and Maths). | E (baker) | NK | Nil | Normal | Bilateral high T1 signal in pons – artefact |

| KCNJ11 4 (R201C) | N | Yes | MS then C (computing module) | LS (throughout school) | E (pubs, shops, hotel) | B – E (operations manager), S – E (sports complex manager) | Depression – Sertraline 50mg. Occasional auditory hallucinations. | Nystagmus (2-3 beats on horizontal gaze), subtle intention tremor. | N |

| KCNJ11 5 (R201C) | D (gross motor, speech).Speech therapy. | Yes – hypoglycaemia on insulin | MS then C (for people with ID) | LS (from age 10). | CS (college for people with ID). | F – E (company manager), M - UE (housewife), B – E (aviation engineer), B – US (political science) | Anxiety (social skills training by psychologist) | Impaired motor sequencing. | ND |

| KCNJ11 6 (V252G) | D (speech, fine motor). Speech therapy. | No | SS then school for autistic children | Unable to read/write. Supported accommodation. | UE | B – E (carpenter) | Autism | Impaired motor sequencing, praxis, heel-toe walking. Hand-flapping. | ND |

| KCNJ11 7 (V59M) | Speech therapy. | Yes – hypoglycaemia on insulin | MS then C (1st year - childcare) | LS (throughout school) | E (SS teaching assistant) | M – E (SS teaching assistant), F – E (lecturer), B – E (trainee lawyer) | Anxiety | Impaired motor sequencing, dysdiadokokinesis, choreiform movements. | N (movement artefact) |

| KCNJ11 8 (V59M) | D (global). | Yes – hypoglycaemia on insulin | SS | Unable to read/write. | UE | S – E (museum curator) | Autism | Ritualistic, clumsy, echolalia. Generally uncooperative with examination. | ND |

| INS 1 (C43F) | N | Yes | U (pharmacy degree) | No | E (hospital pharmacist) | NK | Nil | Normal | ND |

| INS 2 (F48C) | N | Yes – hypoglycaemia | U (law degree) | No support. | UE (ill health). Clerical / carer jobs in past | F – E (taxi business manager, security guard) | Depression (medication and CBT in the past), OCD | Depressed leg reflexes (in-keeping with known diabetic neuropathy). | Left temporal lobe abnormality – CSF space or artefact |

| INS 3 (G75C) | N | No | MS | No support. | E (dept. of work and pensions) | F – E (carpenter, transport manager), B – E (marketing agency) | Nil | N | N |

| INS 4 (H29D) | N | Yes – DKA | MS | LS (Maths & English 4 years). | E (bank call centre) | F – E (carpenter) | Anxiety, panic attacks (Escitalopram in the past) | N | Prominent left cerebellar sulcus, periventricular white matter lesions |

NK = not known, ND = not done, D=delayed, N=normal, MS = Mainstream school, SS = Special school, U = University, C = College, LS = learning support, E = employed, UE = unemployed, ID = intellectual disability, US = university student, CS = college student, OCD = obsessive compulsive disorder, DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis, F = father, M = mother, B = brother, S = sister

Developmental History, Educational and Professional Attainment

Developmental histories, level of educational support and employment history reported for each participant are described in Table 2. Developmental delay and / or learning difficulties were present in all KCNJ11 participants and they continued to require high levels of support as adults. In contrast, the INS group did not report major learning difficulties in keeping with their subsequent employment history and independence in adulthood.

Neurodevelopmental and Psychiatric Features

4/8 with KCNJ11 mutations, but none of the participants with INS mutations, had features of autistic spectrum disorder, either via a clinical diagnosis of autism or an AQ score at or above the threshold suggestive of clinically significant autistic traits (Table 2 and S3). Two individuals in the KCNJ11 group and one in the INS group required treatment either at the time of the study or in the past for depression or anxiety. HADS scores for anxiety and depression were similar in KCNJ11 vs INS participants (Table S3). One individual in the KCNJ11 group and 2 individuals in the INS group scored above the HADS clinical threshold (11) for anxiety (Table 2, Table S3).

Cognitive Function

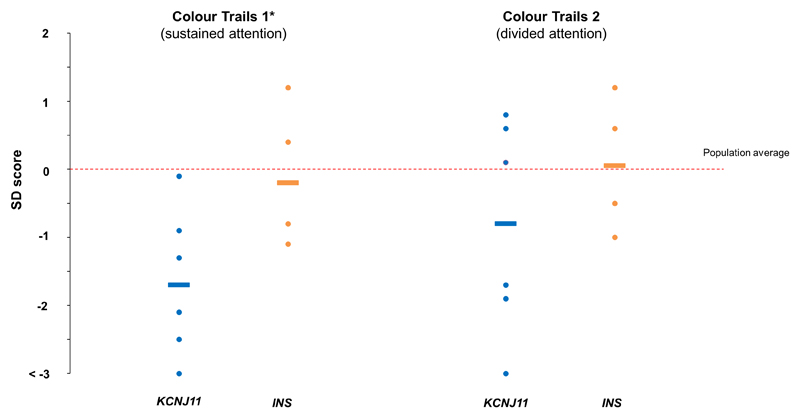

IQ was lower in the KCNJ11 group vs the INS group (IQ 76(55-101), n=7 and 111(90-124), n=4, p=0.02). Three individuals in the KCNJ11 group had IQs <70 (Table S2) and impairments in adaptive behaviors in-keeping with a clinical diagnosis of intellectual disability (39). 5/7 individuals in the KCNJ11 group scored below the clinical cut-point for cognitive impairment on the ACE-R (Figure S1). CTT1 scores suggested reduced attention (CTT1 Z-score -1.7(-3.0- -0.1), n=6 vs 0.4(-1.1-1.2), n=4, p=0.03, CTT2 Z-score -0.8(-3.0-0.8), n=6 vs. 0.7(-1.0-1.2), n=4, p=0.13 (Figure 2, Table S2)).

Figure 2.

Colour Trails Test 1&2 scores represented as Z-scores in the KCNJ11 group (blue, n=6) and INS group (orange, n=4). Lines show group medians for each subtest; dots represent individuals. *denotes p<0.05 for difference between KCNJ11 and INS groups.

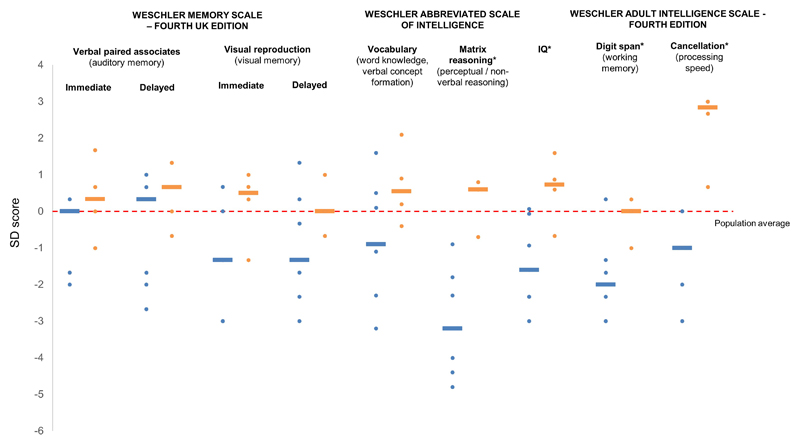

In the KCNJ11 group but not the INS group median scores in the WASI, WAIS and WMS were below population average in all subtests apart from the verbal paired associates subtest of the WMS (Figure 1). Scores were particularly low (≤2SD below population average) in the matrix reasoning component of the WASI (Z-score -3.2(-4.8- -0.9) vs. 0.6(-0.7-0.8), p=0.008) and the digit span component of the WAIS-IV (Z-score -2.0(-3.0-0.3) vs 0(-1.0-0.3), p=0.046). Cancellation scores, although not as markedly reduced compared to population norms, were significantly lower in the KCNJ11 group (Z-score -1(-3-0) vs 2.8(0.7-3.0), p=0.007). COWAT and VOSP scores showed a trend towards reduced executive function and visuospatial function respectively in the KCNJ11 group (Table S3), although these did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Neuropsychological testing in KCNJ11 patients (blue, n=7) and INS patients (orange, n=4). WMS: Verbal paired associates I/II (immediate/delayed) – auditory memory, Visual reproduction I/II (immediate/delayed) – visual memory (both components of working memory) WASI: Vocabulary - word knowledge and verbal concept formation, matrix reasoning – non-verbal/perceptual reasoning. Digit span – working memory, cancellation – processing speed. *denotes p<0.05 for difference between KCNJ11 and INS groups.

Behavioral / functional impact

In the KCNJ11 group, 6 individuals had severe behavioral features which clustered in the domains of everyday skills (5/6), stereotypic behavior (5/6), memory and orientation (4/6), abnormal behavior (3/6), mood (3/6), and motivation (3/6). Specific everyday skills highlighted included writing (3/5) and dealing with money/bills (2/5). The most frequent stereotypic behaviors were being rigid / fixed (3/5) and having fixed routines (4/5). Poor concentration was highlighted as a specific feature in all 4 individuals who had memory and orientation problems. Two individuals had significant difficulties with self-care and 2 reported disturbed sleep.

Neuroimaging

Structural brain MRI was normal in participants with KCNJ11 mutations. In INS controls, 2 were normal, and 2 had minor abnormalities which were not clinically significant (Table 2).

Severity of impairments associated with the specific mutation

Performance in the cognitive tests was better in the 2 individuals with the R201H mutation. These individuals consistently had scores equal to or greater than the KCNJ11 group medians (Figures 1 and 2, Table S2), and no significant behavioral features were reported.

Discussion

We have characterised for the first time the profile of neurological, neuropsychological and behavioral features present in adults with PNDM due to KCNJ11 mutations. The key features were learning difficulties, features of ASD, subtle motor deficits affecting coordination and motor sequencing, and reduced IQ. Specific cognitive domains most affected were perceptual/non-verbal reasoning, working memory, and attention, with a trend towards executive dysfunction and impaired visuospatial abilities. Verbal paired associate memory was relatively preserved. The impact on everyday functioning was significant; 2 participants were severely impaired, requiring support with activities of daily living. A comparison group of patients with neonatal diabetes of similar duration due to INS mutations did not show any of these specific features indicating that they are unlikely to be a non-specific effect of metabolic disturbance from birth. Furthermore, as both groups were insulin treated from diagnosis as infants, the differences observed are unlikely to have been influenced by variation in the timing or duration of action of insulin on insulin and IGF receptors in the brain.

Our findings are consistent with studies in paediatric cohorts with KCNJ11 neonatal diabetes. Specifically, the motor features noted on neurological examination, together with impairments of attention, working memory, visuospatial ability and executive function are consistent with the previously reported high prevalence of developmental coordination disorder, inattention, executive dysfunction and poor visuomotor performance in children with KCNJ11 mutations (12–14; 17; 18; 23; 40). ASD features in 4 individuals with KCNJ11 mutations is consistent with previous research reporting high rates of neurodevelopmental disorders in affected children (16; 18; 41). Dyspraxia, visuomotor impairment, autism and impaired executive function may be related to the high levels of expression of dysfunctional KATP channels in the cerebellum in KCNJ11 PNDM (7; 10).

Importantly, the abnormal findings we report in the KCNJ11 group were mutation-specific; the 2 individuals with the R201H mutation had no overt features and only some subtle abnormalities on neuropsychological testing (Table S2). As a result, both were able to live independently and support themselves financially. Those with more severe features required high levels of support from family members and professionals in healthcare, education and social care. This is consistent with previous studies showing the severity of the CNS phenotype is related to the specific mutation; for example, the V59M mutation results in more severe features, greater impairment in daily living skills (13) and greater impact on families (16). Interestingly, however, there was a relatively good level of social integration from all patients with KCNJ11 mutations even when the neurobehavioral features were severe.

Some of our findings contrast with previous research. To our knowledge choreiform movements have not been previously associated with KCNJ11 PNDM but were observed in one individual with the V59M mutation in our study. We did not identify abnormal tone in our cohort, which contrasts with the hypotonia previously reported, particularly in the context of DEND/iDEND syndrome (42). This may be explained by 7/8 individuals in our study being sulfonylurea-treated; improvement in tone to near-normal following transfer from insulin to sulfonylureas has been observed in a recent study of children with KCNJ11 PNDM (23). Similarly, improvement of visuospatial abilities and attention following transfer to sulfonylureas was noted in the paediatric study (23), which could account for the attention deficits and visuospatial impairment being less marked in our cohort of sulfonylurea-treated adults than might have been expected given previous descriptions (17; 23). Our neuroimaging findings contrast with this paediatric study in which there were non-specific findings in 12/17 who underwent brain MRI, largely comprising white matter abnormalities (23). However, these scans were performed at baseline prior to transfer to sulfonylureas (23). It is not known whether the abnormalities would have improved after a period of sulfonylurea treatment, as has been shown in SPECT studies (24; 27).

Sulfonylurea treatment may influence the CNS phenotype in KCNJ11 PNDM. Two studies have suggested that an earlier age of initiation of sulfonylureas can lead to better CNS outcomes (17; 23). We were unable to assess this in our study because median age at transfer to sulfonylureas was 18 years (range 11-34). However, the persistence of CNS features in some patients even after early initiation of treatment (16; 23) suggests other factors are involved. Specifically, active transport of glyburide out of the brain across the blood-brain barrier, as has been demonstrated in a rodent model (28), may result in suboptimal concentrations in the CSF, thereby limiting therapeutic efficacy in the human CNS. Anecdotal clinical experience suggests that this can be partially addressed by increasing the dose of glyburide to ~1mg/kg/day; however there have been no cases of complete resolution of CNS features in a patient with iDEND. Another possible reason for the partial response is that pathways that can fully restore KATP channel function in other tissues are not available in the CNS to interact with brain KATP channels. For example, restoration of pancreatic KATP channel function resulting in excellent glycaemic control with sulfonylurea treatment is dependent on the activity of incretin hormones (3). Furthermore, there is a theoretical impact of insulin deficiency in utero and / or C-peptide deficiency prior to sulfonylurea transfer on the brain as an indirect consequence of KCNJ11 mutations, but more studies are needed to explore this in humans. Indeed, given the complexities of human neurodevelopmental processes, it is likely that several factors contribute in some way to the response of CNS features to sulfonylureas in KCNJ11 PNDM.

Strengths, Limitations and future work

This study has important strengths. It is the first to assess in detail the CNS manifestations of KCNJ11 mutations in adults and to control for the non-specific effects of PNDM by comparing the features in individuals with INS mutations. Limitations of the study, which relate to the rarity of the disease, are the small number of individuals in each group, the broad range of mutations studied, and the variable timing of initiation and duration of treatment with sulfonylureas in the KCNJ11 group. Studies in larger cohorts with single specific mutations would be valuable. Furthermore, exploration of the impact of treatment-specific factors, such as age of initiation, dose and CNS handling of sulfonylureas in humans, on CNS features in KCNJ11 PNDM is warranted.

Conclusion

The CNS phenotype in adults with KCNJ11 mutations comprises learning difficulty, autistic features, subtle motor dysfunction, moderately reduced IQ, and impaired attention, perceptual reasoning and working memory. The severity of these features varies with the causative mutation. They persist despite long term sulfonylurea therapy, at least when this is started after the first decade of life, and represent the major burden from KCNJ11 mutations once glycemia is well controlled on sulfonylureas. These CNS features are not present in individuals with INS mutations, which indicates that they do not occur as a result of the lifelong metabolic disturbance imposed by PNDM, but as a consequence of impaired KATP channel function in the brain. Clinicians in adult and paediatric medicine should be aware of the potential impact of CNS features in patients with KCNJ11 mutations and should consider multidisciplinary management to ensure appropriate support is provided.

Supplementary Material

ACE-R in KCNJ11 individuals (blue), n=7 and INS individuals (orange), n=4. Scores are presented as percentages of maximum possible score for each subsection. A total score of ≤82 is suggests clinically relevant cognitive impairment.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the individuals with neonatal diabetes and their families who participated in the study, staff in the Exeter Clinical Research Facility who supported the study, Dr James Taylor, Consultant radiologist, who interpreted the MRI scans, and Dr Jon Fulford who provided technical support with MRI scanning. Dr Pamela Bowman is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding

ATH is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator award (Grant number 098395/Z/12/Z). PB has a Sir George Alberti Clinical Research Training Fellowship funded by Diabetes UK (Grant Number 16/0005407). SEF has a Sir Henry Dale Fellowship jointly funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Royal Society (Grant Number 105636/Z/14/Z). MHS and BAK are supported by the NIHR Exeter Clinical Research Facility.

Footnotes

Author contributions: AZ, LT, AC, ATH, and BAK contributed to conception and design of the study. AZ, LT, JD, PB, ATH, MHS and SEF contributed to data acquisition. PB, JD, AZ, LT, TJF, ATH, SEF, and MHS contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. PB drafted the article and all other authors critically revised it. All authors approved the final version prior to submission.

Conflicts of interest disclosures

None to declare.

References

- 1.De Franco E, Flanagan SE, Houghton JA, Lango Allen H, Mackay DJ, Temple IK, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. The effect of early, comprehensive genomic testing on clinical care in neonatal diabetes: an international cohort study. Lancet. 2015;386:957–963. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60098-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gloyn AL, Pearson ER, Antcliff JF, Proks P, Bruining GJ, Slingerland AS, Howard N, Srinivasan S, Silva JM, Molnes J, Edghill EL, et al. Activating mutations in the gene encoding the ATP-sensitive potassium-channel subunit Kir6.2 and permanent neonatal diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1838–1849. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pearson ER, Flechtner I, Njolstad PR, Malecki MT, Flanagan SE, Larkin B, Ashcroft FM, Klimes I, Codner E, Iotova V, Slingerland AS, et al. Switching from insulin to oral sulfonylureas in patients with diabetes due to Kir6.2 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:467–477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shepherd M. Transforming lives: transferring people with neonatal diabetes from insulin to sulphonyureas. EDN Winter. 2006;3:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liss B, Roeper J. Molecular physiology of neuronal K-ATP channels (review) Mol Membr Biol. 2001;18:117–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liss B, Roeper J. A role for neuronal K(ATP) channels in metabolic control of the seizure gate. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2001;22:599–601. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01861-7. discussion 601–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark RH, McTaggart JS, Webster R, Mannikko R, Iberl M, Sim XL, Rorsman P, Glitsch M, Beeson D, Ashcroft FM. Muscle dysfunction caused by a KATP channel mutation in neonatal diabetes is neuronal in origin. Science. 2010;329:458–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1186146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karschin C, Ecke C, Ashcroft FM, Karschin A. Overlapping distribution of K(ATP) channel-forming Kir6.2 subunit and the sulfonylurea receptor SUR1 in rodent brain. FEBS Lett. 1997;401:59–64. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01438-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fine EJ, Ionita CC, Lohr L. The history of the development of the cerebellar examination. Semin Neurol. 2002;22:375–384. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-36759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker EB, Stoodley CJ. Autism spectrum disorder and the cerebellum. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2013;113:1–34. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-418700-9.00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 4):561–579. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Busiah K, Drunat S, Vaivre-Douret L, Bonnefond A, Simon A, Flechtner I, Gerard B, Pouvreau N, Elie C, Nimri R, De Vries L, et al. Neuropsychological dysfunction and developmental defects associated with genetic changes in infants with neonatal diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study [corrected] The Lancet Diabetes & endocrinology. 2013;1:199–207. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmody D, Pastore AN, Landmeier KA, Letourneau LR, Martin R, Hwang JL, Naylor RN, Hunter SJ, Msall ME, Philipson LH, Scott MN, et al. Patients with KCNJ11-related diabetes frequently have neuropsychological impairments compared with sibling controls. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1380–1386. doi: 10.1111/dme.13159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bowman P, Hattersley AT, Knight BA, Broadbridge E, Pettit L, Reville M, Flanagan SE, Shepherd MH, Ford TJ, Tonks J. Neuropsychological impairments in children with KCNJ11 neonatal diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34:1171–1173. doi: 10.1111/dme.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flanagan SE, Edghill EL, Gloyn AL, Ellard S, Hattersley AT. Mutations in KCNJ11, which encodes Kir6.2, are a common cause of diabetes diagnosed in the first 6 months of life, with the phenotype determined by genotype. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1190–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowman P, Broadbridge E, Knight BA, Pettit L, Flanagan SE, Reville M, Tonks J, Shepherd MH, Ford TJ, Hattersley AT. Psychiatric morbidity in children with KCNJ11 neonatal diabetes. Diabet Med. 2016;33:1387–1391. doi: 10.1111/dme.13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah RP, Spruyt K, Kragie BC, Greeley SA, Msall ME. Visuomotor performance in KCNJ11-related neonatal diabetes is impaired in children with DEND-associated mutations and may be improved by early treatment with sulfonylureas. Diabetes care. 2012;35:2086–2088. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landmeier KA, Lanning M, Carmody D, Greeley SAW, Msall ME. ADHD, learning difficulties and sleep disturbances associated with KCNJ11-related neonatal diabetes. Pediatric diabetes. 2017;18:518–523. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girard CA, Shimomura K, Proks P, Absalom N, Castano L, Perez de Nanclares G, Ashcroft FM. Functional analysis of six Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) mutations causing neonatal diabetes. Pflugers Arch. 2006;453:323–332. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Proks P, Girard C, Ashcroft FM. Functional effects of KCNJ11 mutations causing neonatal diabetes: enhanced activation by MgATP. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:2717–2726. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Proks P, Antcliff JF, Lippiat J, Gloyn AL, Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Molecular basis of Kir6.2 mutations associated with neonatal diabetes or neonatal diabetes plus neurological features. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:17539–17544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404756101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koster JC, Remedi MS, Dao C, Nichols CG. ATP and sulfonylurea sensitivity of mutant ATP-sensitive K+ channels in neonatal diabetes: implications for pharmacogenomic therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2645–2654. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beltrand J, Elie C, Busiah K, Fournier E, Boddaert N, Bahi-Buisson N, Vera M, Bui-Quoc E, Ingster-Moati I, Berdugo M, Simon A, et al. Sulfonylurea Therapy Benefits Neurological and Psychomotor Functions in Patients With Neonatal Diabetes Owing to Potassium Channel Mutations. Diabetes care. 2015;38:2033–2041. doi: 10.2337/dc15-0837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mlynarski W, Tarasov AI, Gach A, Girard CA, Pietrzak I, Zubcevic L, Kusmierek J, Klupa T, Malecki MT, Ashcroft FM. Sulfonylurea improves CNS function in a case of intermediate DEND syndrome caused by a mutation in KCNJ11. Nature clinical practice Neurology. 2007;3:640–645. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slingerland AS, Nuboer R, Hadders-Algra M, Hattersley AT, Bruining GJ. Improved motor development and good long-term glycaemic control with sulfonylurea treatment in a patient with the syndrome of intermediate developmental delay, early-onset generalised epilepsy and neonatal diabetes associated with the V59M mutation in the KCNJ11 gene. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2559–2563. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slingerland AS, Hurkx W, Noordam K, Flanagan SE, Jukema JW, Meiners LC, Bruining GJ, Hattersley AT, Hadders-Algra M. Sulphonylurea therapy improves cognition in a patient with the V59M KCNJ11 mutation. Diabet Med. 2008;25:277–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fendler W, Pietrzak I, Brereton MF, Lahmann C, Gadzicki M, Bienkiewicz M, Drozdz I, Borowiec M, Malecki MT, Ashcroft FM, Mlynarski WM. Switching to sulphonylureas in children with iDEND syndrome caused by KCNJ11 mutations results in improved cerebellar perfusion. Diabetes care. 2013;36:2311–2316. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lahmann C, Kramer HB, Ashcroft FM. Systemic Administration of Glibenclamide Fails to Achieve Therapeutic Levels in the Brain and Cerebrospinal Fluid of Rodents. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.http://www.diabetesgenes.org/content/kcnj11-and-abcc8-neonatal-diabetes-effects-brain

- 30.Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Holmes CJ, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. In vivo evidence for post-adolescent brain maturation in frontal and striatal regions. Nature neuroscience. 1999;2:859–861. doi: 10.1038/13154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson SB, Blum RW, Giedd JN. Adolescent maturity and the brain: the promise and pitfalls of neuroscience research in adolescent health policy. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Patch AM, Boustred C, Parrish A, Shields B, Shepherd MH, Hussain K, Kapoor RR, Malecki M, MacDonald MJ, et al. Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2008;57:1034–1042. doi: 10.2337/db07-1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoy J, Steiner DF, Park SY, Ye H, Philipson LH, Bell GI. Clinical and molecular genetics of neonatal diabetes due to mutations in the insulin gene. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9151-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edge JA, Hawkins MM, Winter DL, Dunger DB. The risk and outcome of cerebral oedema developing during diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85:16–22. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosenbloom AL. Intracerebral crises during treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis. Diabetes care. 1990;13:22–33. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Day JO, Flanagan SE, Shepherd MH, Patrick AW, Abid N, Torrens L, Zeman AJ, Patel KA, Hattersley AT. Hyperglycaemia-related complications at the time of diagnosis can cause permanent neurological disability in children with neonatal diabetes. Diabet Med. 2017;34:1000–1004. doi: 10.1111/dme.13328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan CM, van Duinkerken E, Rosano C. Neurocognitive consequences of diabetes. Am Psychol. 2016;71:563–576. doi: 10.1037/a0040455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blazquez E, Velazquez E, Hurtado-Carneiro V, Ruiz-Albusac JM. Insulin in the brain: its pathophysiological implications for States related with central insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2014;5:161. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McTaggart JS, Jenkinson N, Brittain JS, Greeley SA, Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Gain-of-function mutations in the K(ATP) channel (KCNJ11) impair coordinated hand-eye tracking. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62646. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tonini G, Bizzarri C, Bonfanti R, Vanelli M, Cerutti F, Faleschini E, Meschi F, Prisco F, Ciacco E, Cappa M, Torelli C, et al. Sulfonylurea treatment outweighs insulin therapy in short-term metabolic control of patients with permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus due to activating mutations of the KCNJ11 (KIR6.2) gene. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2210–2213. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0329-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hattersley AT, Ashcroft FM. Activating mutations in Kir6.2 and neonatal diabetes: new clinical syndromes, new scientific insights, and new therapy. Diabetes. 2005;54:2503–2513. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ACE-R in KCNJ11 individuals (blue), n=7 and INS individuals (orange), n=4. Scores are presented as percentages of maximum possible score for each subsection. A total score of ≤82 is suggests clinically relevant cognitive impairment.